Abstract

Background and Objectives:

The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program provides vaccines for children who may not otherwise be vaccinated because of financial barriers. Pediatrician participation is crucial to VFC’s ongoing success. Our objectives were to assess among a national sample of pediatricians: 1) VFC program participation; 2) perceived burden versus benefit of participation; 3) knowledge and perception of a time-limited increased payment for VFC vaccine administration under the Affordable Care Act.

Methods:

An electronic and mail survey conducted June to September 2017.

Results:

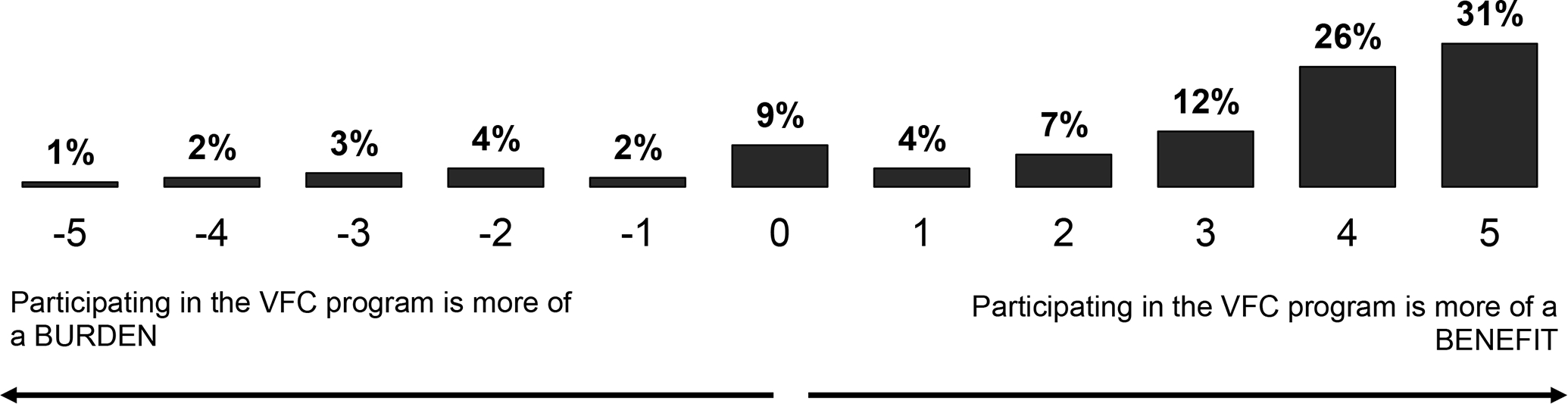

Response rate was 79% (372/471); 86% of pediatricians reported currently participating in the VFC program; among those, 85% reported never having considered stopping, 10% considered it, but not seriously, and 5% seriously considered it. Among those who had considered no longer participating (n=47), the most commonly reported reasons included difficulty meeting VFC record-keeping requirements (74%), concern about action by the VFC program for non-compliance (61%), and unpredictable VFC vaccine supplies (59%). Participating pediatricians rated on a scale from −5 (high burden) to +5 (high benefit) their overall perception of the VFC program; 63% reported +4 or +5, 23% +1 to +3, 5% 0, and 9% −1 to −5. 39% of pediatricians reported awareness of temporary increased payment for VFC vaccine administration. Among those, 10% reported their practice increased the proportion of Medicaid and/or VFC-eligible patients served based on this change.

Conclusions:

For most pediatricians, perceived benefits of VFC program participation far outweigh perceived burdens. To ensure the program’s ongoing success, it will be important to monitor factors influencing provider participation.

Table of Contents Summary:

This manuscript describes pediatricians’ experiences with and attitudes about the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, including perceived benefits and burdens.

INTRODUCTION

The Vaccines For Children (VFC) program was created in 1993 to ensure that children would not suffer from vaccine-preventable diseases due to inability to pay for vaccines.1,2 The VFC program supplies >50% of vaccines for children in the US.3 Since its implementation in 1994, the VFC program has been credited with increasing rates of vaccine uptake among US children, decreasing vaccine-preventable disease incidence, and reducing racial and socioeconomic disparities in vaccine uptake.4,5 Children through age 18 years are eligible for the program if they are eligible for Medicaid, uninsured or with insurance that does not cover vaccination, or American Indian or Alaska Native.5 Each state or local immunization program purchases VFC vaccines with federal funds; vaccines are delivered to and administered by local VFC-enrolled providers. While some VFC vaccines are administered in public health departments or similar venues, the majority are administered by primary care pediatricians.6 Participation by pediatricians is therefore critical to the success of the VFC program.

While the vaccines provided by the VFC program are made available at no cost to providers, providers must meet VFC program participation requirements related to ensuring proper storage and handling, administration, and documentation of vaccines. In some cases, financial and administrative requirements of VFC program participation may affect providers’ willingness to participate in the program. For example, VFC program providers may need to purchase and maintain storage equipment that conforms to VFC program requirements, complete annual training, and participate in site visits conducted by the local public health staff every 24 months. Although providers can charge an administration fee to their state’s Medicaid program for each VFC vaccine administered to a Medicaid-enrolled patient, reimbursement is often inadequate to cover costs.7 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) included a provision to temporarily increase Medicaid vaccine administration fees to Medicare levels in 2013 and 20148 that was expected to address this issue.9 The impact of that provision is unknown.

Shortages of routine childhood vaccines and delays in delivery of the influenza vaccine to providers have led to missed opportunities for vaccination and frustration for providers in the past.10–15 Some reports suggest the timing of VFC influenza vaccine distribution lags behind distribution of private stock influenza vaccines.16,17

The aforementioned issues related to program requirements, payment, and delivery delays have the potential to impact pediatricians’ participation in the VFC program. Because pediatrician participation is crucial to the program’s success, we sought to explore pediatricians’ current attitudes and experiences with the program and how these attitudes and experiences are affecting participation. Our specific objectives were to assess the following among a nationally representative sample of pediatricians: 1) Participation in the VFC program; 2) Perceived burden versus benefit of VFC program participation; 3) Experiences and practices related to vaccine stocking challenges; and 4) Knowledge and perception of the effect of a time-limited increased reimbursement for VFC vaccine administration for Medicaid patients under the ACA.

METHODS

We conducted a survey from June through September of 2017 among pediatricians who were part of a sentinel network. The human subjects review board at the University of Colorado Denver approved this study as exempt research not requiring written informed consent.

Study Population

We developed a national network of pediatricians by recruiting from a random sample of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) membership roster. From this sample, based upon information available in the AAP membership roster with regard to region (Northeast, South, Midwest, or West), practice location (urban inner-city, suburban, or rural), and practice setting (private, managed care, or hospital/university/community health center), we conducted quota sampling18 to ensure network pediatricians were similar to the overall AAP membership. To do this, we determined proportions of US pediatricians falling into each cell of a 3-dimensional matrix that crossed region, practice location, and practice setting. We then applied proportions for each cell in the 36-cell matrix to a sample size of 400 to create cell-sampling quotas. A sample size of 400 was chosen for a maximum estimated confidence interval of ±5% on point estimates. After the random sample was selected, physicians were contacted by mail with an explanation of the study and a request to participate, and were asked if they preferred to participate by mail or email. Pediatricians were excluded from participation if they practiced <50% of the time in primary care, practiced outside of the United States, or were in training. During the screening process, we also ask pediatricians if their practice site makes independent decisions about purchasing and handling of vaccines or if these decisions are made as part of a larger system, although responses to this question do not impact selection into the network. We previously demonstrated that survey responses from sentinel network pediatricians compared to those of pediatricians randomly sampled from American Medical Association databases had similar demographic characteristics, practice attributes, and attitudes about a range of vaccination issues.18

Survey Design

We developed the survey in collaboration with CDC, and with input from AAP. A national advisory panel of pediatricians (n=7) pre-tested the survey, with modifications made based on their feedback. We then piloted the survey instrument among 41 pediatricians nationally with further modifications based on their feedback and survey responses. Questions regarding program participation and current practice were assessed with categorical response options. Attitudinal questions were assessed using 4-point Likert scales from strongly agree to strongly disagree. We assessed perceived burden versus benefit of VFC program participation on an 11-point scale (−5 [high burden] to +5 [high benefit]). Questions regarding vaccine delays were assessed using a 4-point Likert scale (not a problem to major problem).

Survey Administration

We surveyed physicians by Internet (Verint, Melville, New York, www.verint.com) or by mail based on previously-reported physician preference. The Internet group was sent an initial e-mail with up to 8 reminders, and the mail group was sent an initial mailing and up to 2 reminders. We sent Internet survey non-respondents a mail survey in case of problems with e-mail correspondence. We patterned the email and mail protocol on Dillman’s tailored design method.19

Statistical Analysis

We pooled Internet and mail surveys for analyses because studies have shown that physician attitudes are similar when obtained by either method.20 We compared respondents with non-respondents using t-tests, Wilcoxon tests and chi-square analyses and compared sub-categories of respondents using chi-square. In a sensitivity analysis, we compared responses from pediatricians in practices where vaccine decisions were made independently versus at a larger system level. Analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Response Rates and Study Sample

The response rate was 79% (372/471). Respondents were similar to non-respondents with respect to age, gender, region, location (urban, suburban, rural), setting (private, hospital- or community health center-based, health maintenance organization), and decision-making (independent versus larger system level) (Table 1). Three respondents (1%) reported not administering vaccines in their practice and were excluded from further analysis.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Respondents and Non-Respondents to a National Survey Among Pediatricians Regarding the Vaccines for Children Program.

| Characteristic | Respondents % (n) (n=372) | Non-Respondents % (n) (n=99) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, % | 37 (136) | 33 (33) | 0.55 |

| Private Practice | 80 (297) | 77 (76) | 0.71 |

| Hospital or clinic | 17 (62) | 18 (18) | |

| HMO | 4 (13) | 5 (5) | |

| Urban | 55 (203) | 51 (50) | 0.79* |

| Suburban | 44 (165) | 49 (48) | |

| Rural | 1 (4) | 5 (5) | |

| Midwest | 23 (84) | 18 (18) | 0.06** |

| Northeast | 22 (82) | 14 (14) | |

| South | 37 (136) | 38 (38) | |

| West | 19 (70) | 29 (29) | |

| Independent | 70 (255) | 68 (65) | 0.63 |

| Larger system level | 30 (108) | 32 (31) | |

| Mean (sd) / Median age in years | 51 (10) / 51 | 51 (12) / 50 | 0.85 |

| Mean (sd) / Median number of providers in practice | 11 (26) / 6 | 15 (51) / 5 | 0.83* |

All p-values from chi-square tests except where noted

Fisher’s Exact test

Wilcoxon test

Abbreviations: HMO, health maintenance organization; sd, standard deviation.

Participation in the VFC Program

Eighty-six percent of pediatricians reported that they currently participate in the VFC program, 9% that they did not and never had, and 5% that they did not but had previously. Among those reporting they did not currently participate (n=51), the most commonly cited reasons included non-participation in the Medicaid program (65%), not having enough low income patients (56%), the burden of keeping separate stocks of VFC and private vaccines (44%), the difficulty of VFC record-keeping requirements (39%), and the administrative burden of VFC participation (37%). Among those not currently participating, only 14% reported that they would consider participation in the future.

Respondents currently participating in the VFC program were asked to report to what extent their practices had considered stopping participation in the past year. Eighty-five percent reported that they had never considered or discussed this, 10% that they had considered or discussed it, but not seriously, and 5% that they had seriously considered or discussed it. Among those who had considered or seriously considered no longer participating (n=47), the most commonly reported reasons included the difficulty of VFC record-keeping requirements (74%), concern about action by the VFC program for non-compliance (61%), unpredictable VFC vaccine supplies (59%), inadequate payment for vaccine administration fees (57%), and the burden of keeping separate stocks of VFC and private stock vaccines (46%).

Pediatrician Perceptions of the VFC program

In general, pediatricians who administered vaccines in their practice reported very favorable attitudes towards the VFC program (Table 2; includes all respondents, n=369). Almost all pediatricians strongly agreed that participation in the VFC program is valuable because it allows practices to administer vaccines to children regardless of ability to pay (93%), that the VFC program improves access to childhood vaccines (90%), and that the VFC program is valuable because it allows children to be vaccinated in the medical home (88%). Just over half of pediatricians (54%) also agreed (strongly or somewhat) that payment for VFC vaccine administration was less than payment for vaccine administration from private plans; 42% reported not knowing. Substantial proportions of pediatricians also endorsed statements about whether specific aspects of VFC program participation were burdensome or challenging, such as requirements regarding monitoring, tracking, and recording of VFC storage temperatures (23% strongly agree, 45% somewhat agree), requirements to replace lost doses of VFC vaccine (20% strongly, 28% somewhat), and keeping separate stocks of VFC and private vaccines (16% strongly, 36% somewhat). Results were similar when limited to providers currently participating in the VFC program.

Table 2:

Pediatricians’ Attitudes Regarding the Vaccines for Children (VFC) Program (n=369).

| Strongly agree % (n) | Somewhat agree % (n) | Somewhat disagree % (n) | Strongly disagree % (n) | Don’t know % (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participating in the VFC program is valuable because it allows practices to administer vaccines to children regardless of ability to pay | 93 (338) | 4 (15) | 1 (3) | 0 (1) | 2 (7) |

| The VFC program improves access to childhood vaccines | 90 (328) | 7 (24) | 0 | 1 (3) | 2 (8) |

| The VFC program is valuable because it allows children to be vaccinated in the medical home | 88 (320) | 7 (25) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 4 (13) |

| On average, the payment for VFC vaccine administration is less than the payment from private health plans | 34 (123) | 20 (74) | 3 (12) | 1 (2) | 42 (151) |

| The requirements regarding monitoring, tracking, and recording of VFC storage temperatures are a burden on practices | 23 (82) | 45 (163) | 10 (35) | 13 (46) | 10 (38) |

| The requirements to replace lost doses of VFC vaccine is a major burden on practices | 20 (73) | 28 (101) | 17 (61) | 11 (39) | 25 (89) |

| Keeping VFC stock separate from private vaccine stock is a major burden on practices | 16 (57) | 36 (130) | 18 (66) | 22 (80) | 8 (30) |

| Billing for vaccine administration fees for Medicaid patients is challenging with the VFC program | 9 (34) | 18 (64) | 28 (102) | 20 (72) | 25 (89) |

Of VFC participants, most pediatricians felt the benefits of participating in the VFC program outweighed the burdens (Figure 1). Using the −5 to +5 scale regarding the degree to which participating in the VFC program represented a burden or a benefit, among VFC-program participants (n=309), 63% reported a score of +4 or +5, 23% reported +1 to +3, 5% 0 (the middle of the scale), and 9% a negative response (−1 to −5).

Figure 1:

Pediatricians’ Perceived Benefit versus Burden in Participation in the Vaccines for Children (VFC) Program. (n=309)

Experiences and Practices Related Vaccine Stocking Challenges

Eight percent of participating VFC providers reported being in states where all vaccines, both private and VFC, come as one supply from the state, so that there is no distinction between VFC and private stock vaccines, and were not asked questions about delays. Among the remaining respondents (n=288), in the event of a non-influenza vaccine being out of stock 39% reported that they did not borrow between VFC and private stock vaccine because they were not allowed to do so, 14% reported that they didn’t do this because they generally didn’t need to, 32% reported they borrowed between stocks less than once a month, 10% less than once a week but more than once a month, and 5% more than once a week.

For influenza vaccine, providers were asked to report how much of a problem they had with delays in receipt of private stock and VFC vaccines in the prior three seasons. For private stock vaccine, 3% reported delays as a major problem, 18% as a moderate problem, 32% as a minor problem, and 48% as not a problem. In contrast, for VFC influenza vaccine, 15% reported delays as a major problem, 32% as a moderate problem, 33% as a minor problem, and 20% as not a problem. To handle influenza vaccine delays, 56% of pediatricians reported postponing influenza vaccination for patients whose vaccine is not in stock, 19% reported referring these patients elsewhere to be vaccinated, 18% reported borrowing between stocks in this setting, and 7% reported postponing vaccination for all patients.

Pediatricians who reported not borrowing between non-influenza vaccine stocks (n=151) were asked how they handled a situation in which one or more VFC vaccines are out of stock. The most commonly reported practices in this situation were asking patients to return for vaccination at a later time (78%) and keeping a list of patients who need the vaccine(s) and calling them back when it is available (71%). Other practices pediatricians reported using included asking patients to call back to find out when vaccine was available (48%), and sending these patients to a public health department (35%). Nine percent reported this situation had never happened in their practice, 5% reported sending these patients to a pharmacy, and 3% to another provider.

Knowledge and Perceptions Regarding Increased Payment for VFC Vaccine Administration

All pediatricians who reported accepting Medicaid in the last 10 years (n=335) were asked to read a descriptive statement regarding increased payment for VFC administration fees authorized by the ACA for the years 2013 and 2014. Forty percent of pediatricians reported prior awareness of this increased payment. Among those (n=132), 10% reported that their practice increased the proportion of Medicaid and/or VFC-eligible patients based on this specific change and 90% that they did not.

Independent versus System-level Decisions

In general, responses were similar from pediatricians in both practices that made independent vaccine decisions versus decisions made as part of a larger system, although there tended to be more “don’t know” responses from physicians where vaccine decisions were made as part of a larger system. Questions with notable differences included “requirements regarding monitoring, tracking, and recording of VFC vaccine storage temperatures are a burden on practices” (strongly agree: 25% independent, 11% system, p=0.04), “Billing for vaccine administration fees for Medicaid patients is challenging with the VFC program” (strongly agree: 11% independent, 2% system; don’t know: 16% independent, 27% system, p=0.02), and “the payment for VFC vaccine administration is less than the payment from private health plans” (strongly agree: 40% independent, 29% system; don’t know: 29% independent, 57% system, p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

In this national survey of pediatricians, we found that the almost all pediatricians participate in the VFC program and believe that the benefits of participation substantially outweigh the burdens. However, large percentages of providers identify several factors as burdensome for their practices, such as requirements for monitoring tracking and recording of VFC storage temperatures, VFC vaccine administration payments that may not cover costs to vaccinate, and the need to keep VFC vaccine stocks separate from private vaccine stock. We also found that in the past year, fifteen percent of current participants have discussed no longer participating in the VFC program, primarily because of record keeping requirements, compliance concerns, perceived unpredictable supplies, perceived inadequate payments, and the need to maintain separate VFC and private vaccine stocks. Finally, less than half of respondents were aware of the temporarily increased payments for VFC vaccine administration, and only 10% of those who were aware increased the proportion of Medicaid patients in their practice as a result.

The benefits of the VFC program to children have been well documented;4,5,21,22 however, to our knowledge, this is the first study to document program benefits from the perspective of pediatricians. This perspective is important to follow because a high level of participation among pediatricians is crucial to the ongoing success of the program. While a small percentage do not participate, and a similar percentage have considered no longer participating, enthusiasm for the program generally remains strong. However, in this study, we also document many concerns pediatricians have with the program. Action at the state and federal levels to monitor these concerns and ameliorate them when feasible will be important to the ongoing success of the VFC program.

The burden most frequently endorsed was related to VFC program requirements regarding monitoring, tracking, and recording of VFC vaccine storage temperatures. Much of this dissatisfaction is likely in response to tighter requirements imposed by the VFC program in recent years. In 2012, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) released a report of an audit that was performed in 45 VFC providers from the 5 states/cities with the highest volume of vaccines ordered: California, Florida, Georgia, New York City, and Texas.23 The OIG reported that “VFC vaccines stored by 76% of the providers were exposed to inappropriate temperatures for at least 5 cumulative hours,” and that “providers generally did not meet vaccine management requirements or maintain required documentation.” In response to the OIG’s report, VFC program administrators issued interim guidance recommending increased frequency and documentation of vaccine storage temperatures for VFC program participants.24 While these “guidelines” were not immediately mandatory and were phased-in over years, many immunization programs began enforcing these requirements more quickly. While it is likely that much of the burden reported by pediatricians related to the VFC program is in response to these tightened requirements, it is reassuring that providers seem to have remained with the program.

This study provides new information regarding how pediatricians handle shortages of VFC vaccine, and updates information we reported previously regarding delays in VFC influenza vaccine,15 showing that when experiencing a delay in influenza vaccine shipments, most pediatricians delay vaccination for eligible patients, causing missed opportunities for influenza vaccination. Regarding non-influenza vaccines, practices vary, with some pediatricians reporting borrowing private stock vaccine fairly frequently and many not at all, thus leading to missed opportunities. At least to some pediatricians, this appears to be a problem: among those who had considered no longer participating in the VFC program, more than half stated that one of the reasons was the unpredictability of the VFC vaccine supply. The ability to borrow private stock vaccine in the event of a delay or shortage of VFC vaccine is a possible solution to this problem, yet for both influenza and non-influenza vaccines, many report not borrowing, most often because they report that they are not allowed to. Although there is no federal prohibition on borrowing private stock vaccine to administer to VFC-eligible children and replacing it with VFC vaccine once available, each state immunization program has the authority to impose additional requirements as needed to best steward its VFC vaccine supply. Certainly, elimination of delays would be the best solution, but reasons behind any delays are likely multifactorial and not easily solved. Additional work is needed to better understand systematic issues that may be causing delays in VFC vaccine distribution.

Provider participation in the VFC program could be expected to be sensitive to policy changes, such as the time-limited increased payment for vaccine administration to Medicaid-enrolled children authorized by the ACA, which was expected to incentivize primary care providers to accept more VFC-eligible children. Payment for vaccine administration is an important source of revenue for pediatric practices.7,25,26 While most pediatricians in this study were not aware of the increased payment, among those that were, 10% reported that they increased the proportion of Medicaid and/or VFC-eligible children they accepted in their practices. It is unclear from our data why this number was not higher than it was. We suspect that it is because such business decisions are multifactorial, and that VFC administration fee payment is only one consideration. That said, while 10% is a relatively small proportion, even small gains matter when considering that such gains might mean that more impoverished children find access to a medical home. To date no cost-effectiveness analysis of this policy change has been performed. However, given that $1 spent on vaccination results in $10 saved in societal costs,27 this change may have been cost-effective even with only a small proportion of pediatricians increasing their acceptance of VFC-eligible patients.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample for this study was designed to represent general pediatricians practicing primary care in the US – we did not specifically seek out those pediatricians who managed VFC programs in their practices, for example. Thus, it is likely that if we had surveyed only pediatricians in leadership or vaccine management roles, our findings regarding certain knowledge questions would have differed from those we present here. While this is an important limitation of this study, the primary objective of our study was to assess the benefits and burdens of the VFC program on practicing pediatricians in general. We attempted to account for this limitation with our sensitivity analysis, showing that those in larger systems were more likely to report “don’t know” to several questions. Also, while our response rate was high, as with any survey, non-respondents may have had different attitudes and experiences than respondents. Finally, results are based on reported practice; actual practice was not observed.

Conclusions

The VFC program relies on pediatricians for vaccine delivery. Pediatricians perceive that the benefits of VFC program participation strongly outweigh the burdens. Pediatricians’ perception of the benefit versus burden of VFC program participation should continue to be monitored, and perceived burdens should be addressed when feasible. Solutions to these burdens are not necessarily straightforward, but could include increased payment for vaccine administration, uniform rules allowing borrowing between VFC vaccine and private stock, and incentivizing the purchase of proper storage and monitoring equipment.

What’s Known on this Subject:

The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program provides vaccines for US children who may not otherwise be vaccinated. Participation in the VFC program by pediatricians is crucial to its ongoing success.

What This Study Adds:

The majority of pediatricians participate in the VFC program, although numerous perceived burdens exist. Overall, pediatricians perceive that the benefits of VFC program participation far outweigh the burdens.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Lynn Olson, PhD, and Karen O’Connor from the Department of Research, AAP, Arlene Weissman, PhD, and the leaders of the AAP for collaborating in the establishment of the sentinel network in pediatrics. We would also like to thank all pediatricians in the network for participating and responding to this survey.

Funding Resource:

All phases of this study were supported by Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Abbreviations:

- VFC

Vaccines for Children

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial disclosures.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have indicated they have no potencial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Santoli JM, Rodewald LE, Maes EF, Battaglia MP, Coronado VG. Vaccines for Children program, United States, 1997. Pediatrics. 1999;104(2):e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler CM, et al. Sustained efficacy up to 4.5 years of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine against human papillomavirus types 16 and 18: follow-up from a randomised control trial. Lancet (London, England). 2006;367(9518):1247–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindley MC, Shen AK, Orenstein WA, Rodewald LE, Birkhead GS. Financing the delivery of vaccines to children and adolescents: challenges to the current system. Pediatrics. 2009;124 Suppl 5:S548–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitney CG, Zhou F, Singleton J, Schuchat A. Benefits from immunization during the vaccines for children program era - United States, 1994–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(16):352–355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker AT, Smith PJ, Kolasa M, Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Reduction of racial/ethnic disparities in vaccination coverage, 1995–2011. MMWR Suppl. 2014;63(1):7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.In: Financing Vaccines in the 21st Century: Assuring Access and Availability. Washington (DC)2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Leary ST, Allison MA, Lindley MC, et al. Vaccine financing from the perspective of primary care physicians. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):367–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.GPO AUSGI. Health Care and Education Reconciliation. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-111publ152/pdf/PLAW-111publ152.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed.

- 9.Tan L Impact of the Affordable Care Act on Immunization. American Medical Association. https://www.izsummitpartners.org/content/uploads/2012/NAIS/NAIS-1_tan_impact.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kempe A, Daley MF, Stokley S, et al. Impact of a severe influenza vaccine shortage on primary care practice. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(6):486–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McQuillan L, Daley MF, Stokley S, et al. Impact of the 2004–2005 influenza vaccine shortage on pediatric practice: a national survey. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):e186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stokley S, Santoli JM, Willis B, Kelley V, Vargas-Rosales A, Rodewald LE. Impact of vaccine shortages on immunization programs and providers. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santibanez TA, Santoli JM, Barker LE. Differential effects of the DTaP and MMR vaccine shortages on timeliness of childhood vaccination coverage. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):691–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ridley DB, Bei X, Liebman EB. No Shot: US Vaccine Prices And Shortages. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(2):235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Leary ST, Barrow JC, McQuillan L, et al. Influenza vaccine delivery delays from the perspective of primary care physicians. American journal of preventive medicine. 2011;40(6):620–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambrose CS, Toback SL. Improved timing of availability and administration of influenza vaccine through the US Vaccines for Children Program from 2007 to 2011. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2013;52(3):224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatt P, Block SL, Toback SL, Ambrose CS. Timing of the availability and administration of influenza vaccine through the vaccines for children program. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(2):100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crane LA, Daley MF, Barrow J, et al. Sentinel physician networks as a technique for rapid immunization policy surveys. EvalHealth Prof. 2008;31(1):43–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dillman DA, Smyth J, Christian LM. Internet, Mail and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Desgin Method, 3rd Edition. Vol 3rd. New York, NY: John Wiley Co.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMahon SR, Iwamoto M, Massoudi MS, et al. Comparison of e-mail, fax, and postal surveys of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 Pt 1):e299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh B, Doherty E, O’Neill C. Since The Start Of The Vaccines For Children Program, Uptake Has Increased, And Most Disparities Have Decreased. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(2):356–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith PJ, Jain N, Stevenson J, Mannikko N, Molinari NA. Progress in timely vaccination coverage among children living in low-income households. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(5):462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levinson DR. Vaccines for Children Program: Vulnerabilities in Vaccine Management. Department of Health and Human Services https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-04-10-00430.pdf. Published June 2012. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- 24.CDC updates guidance on storing vaccines. American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP News Web site. http://www.aappublications.org/content/early/2012/10/05/aapnews.20121005-1. Published October 5, 2012. Accessed September 7, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allison MA, O’Leary ST, Lindley MC, et al. Financing of Vaccine Delivery in Primary Care Practices. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(7):770–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freed GL, Cowan AE, Clark SJ. Primary care physician perspectives on reimbursement for childhood immunizations. Pediatrics. 2009;124 Suppl 5:S466–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou F, Shefer A, Wenger J, et al. Economic evaluation of the routine childhood immunization program in the United States, 2009. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):577–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]