Abstract

With the aim of developing more stable Gd(III)–porphyrin complexes, two types of ligands 1 and 2 with carboxylic acid anchors were synthesized. Due to the N-substituted pyridyl cation attached to the porphyrin core, these porphyrin ligands were highly water-soluble and formed the corresponding Gd(III) chelates, Gd-1 and Gd-2. Gd-1 was sufficiently stable in neutral buffer, presumably due to the preferred conformation of the carboxylate-terminated anchors connected to nitrogen in the meta position of the pyridyl group helping to stabilize Gd(III) complexation by the porphyrin center. 1H NMRD (nuclear magnetic relaxation dispersion) measurements on Gd-1 revealed high longitudinal water proton relaxivity (r1 = 21.2 mM–1 s–1 at 60 MHz and 25 °C), which originates from slow rotational motion resulting from aggregation in aqueous solution. Under visible light irradiation, Gd-1 showed extensive photoinduced DNA cleavage in line with efficient photoinduced singlet oxygen generation. Cell-based assays revealed no significant dark cytotoxicity of Gd-1, while it showed sufficient photocytotoxicity on cancer cell lines under visible light irradiation. These results indicate the potential of this Gd(III)–porphyrin complex (Gd-1) as a core for the development of bifunctional systems acting as an efficient photodynamic therapy photosensitizer (PDT-PS) with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) detection capabilities.

Keywords: Singlet oxygen generation, relaxivity, Gd(III) chelate, water-soluble porphyrin, photocytotoxicity

Introduction

Porphyrins are one of the most common core molecules as photosensitizers (PSs), both in biology (e.g., photosynthesis) and in material sciences (e.g., photovoltaic systems). Since these polyaromatic molecules are often hydrophobic, especially as synthetic derivatives, much effort has been made to develop water-soluble porphyrin materials by adding suitable water-soluble moieties. This is particularly important for biological applications such as photodynamic therapies (PDTs). Indeed, most of the FDA-approved PDT-PS molecules are porphyrin-based compounds, including Photofrin, Foscan, Laserphyrin, and Motezafin lutetium,1 and can be excited by irradiation with visible light to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), as active species to treat the diseased tissues. Key considerations in the development of such PDT-PSs include (1) they can be excited by a long wavelength of light that is less toxic and can penetrate more deeply into the tissue, (2) they can generate ROS in high quantum yield, and (3) they are nontoxic in the absence of light.2−4 Furthermore, researchers have developed efficient PDT-PSs by (a) preparing polymeric PS molecules for passive targeting based on the enhanced permeation retention (EPR) effect by the macromolecules often found in inflammatory diseases5−8 or by (b) adding disease-targeting moieties to the PS cores to enhance the efficiency of PDT-PSs in an active manner via the selective delivery of the PS molecules to the specific tissues that need to be treated.9−12

One of the current challenges in PDT research is to add imaging properties to the PSs to achieve image-guided PDT. By observing the in vivo biodistribution of the PS molecules in real time, it becomes possible to find the optimal timing for light irradiation for the most efficient treatment. For this purpose, bifunctional molecules with both photosensitizing and imaging properties have been reported. The majority of such molecules were made by connecting two types of functional moieties (PS cores and imaging probes) through the conjugation of these two parts.13−24 As an alternative approach, it is desirable to develop bifunctional molecules that can perform as both an imaging probe and a PDT-PS. In this study, we have chosen magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as an imaging modality and porphyrin as a PS core to design and synthesize water-soluble porphyrins with coordinated Gd(III) ion as bifunctional molecules for PDT-PSs and MRI-contrast agents (MRI-CAs). Only few studies on such bifunctional molecules have been reported.25

MRI is highly relevant as a noninvasive in vivo imaging modality, since it provides in-depth high-resolution anatomical information on living bodies including small animals and humans without ionizing radiation. In the presence of MRI-CAs, enhanced image contrast can be obtained.26 FDA-approved MRI-CAs are all paramagnetic Gd(III) chelates that induce significant T1 contrast enhancement and provide great benefits for 3D tomography visualization of tissues with high resolution (ca. 1 mm). Typical clinically used MRI-CAs consist of acyclic or cyclic poly(amino carboxylate) ligands, which strongly coordinate to the Gd(III) with 8-donor atoms (O or N) via Coulombic and dipole-cation interactions. For instance, the acyclic diethylenetriaminepentaacetate (DTPA) coordinates to Gd(III) through its three tertiary amines and five carboxylates and the macrocyclic tetraamine-cyclododecane tetraacetate (DOTA) complexes Gd(III) through four tertiary amines and four carboxylates (Figure 1c). In terms of dissociation kinetics, macrocyclic chelates generally form more inert complexes with Gd(III) due to the higher preorganization of the ligand, which is appreciated as safer MRI-CAs by preventing the leakage of free toxic Gd3+ ions.27 In these Gd(III) complexes, one coordination site of the metal is available for an inner sphere water molecule, which is essential in providing a good relaxation effect. The exchange of this coordinated water molecule with bulk water largely contributes to the relaxation enhancement observable in the MR images. The modulation of this coordinated water can be used to develop switchable contrast agents for the detection of specific biomarkers in the body.28,29

Figure 1.

(a, b) Structures of pyridinyl porphyrin derivatives 1 (a) and 2 (b) and their Gd(III) complexes Gd-1 (a) and Gd-2 (b). (c) Structures of DOTA and GdDOTA.

We have chosen the porphyrin skeleton as a core for the ligand structures because it provides two functions: photosensitivity and Gd(III) complexation. Previously reported examples of MRI-CAs with porphyrin structures, such as the conjugates of porphyrin and Gd(III)-DOTA chelates, provided excellent relaxation enhancement and photoinduced ROS generation.13,23 On the other hand, molecules with a porphyrin as a ligand for Gd(III) complexation have been reported, but without assessment of their stability.30,31

In the present study, two types of water-soluble pyridyl porphyrin derivatives 1 and 2 were designed as ligands for Gd(III), with substitution at the meta or para positions of the pyridyl group with carboxylate-terminated anchors (Figure 1a,b). We expected that these ligands would form Gd(III) complexes (Gd-1 and Gd-2) through 8-coordination sites: four central nitrogen atoms of the porphyrin core and four oxygens of carboxylic acids in the termini of the anchors. Distinct from the stable metal complexation of porphyrins with smaller metal ions such as Fe(III) and Mg(II), which form a flat coordination environment in the porphyrin center, it is known that Gd(III), which has a relatively large ionic radius, only adopts a pyramidalized coordination mode in the porphyrin center with a sitting-atop form, often resulting in low complexation stability.32 To strengthen the Gd(III) coordination at the porphyrin center, anchor groups with a terminal carboxylic acid were added to the porphyrin core. Two porphyrins with 3-pyridyl substituent (compound 1) and 4-pyridyl substituent (compound 2) were designed as ligands for Gd(III) complexation (Figure 1). In addition to the terminal carboxylates, which were expected to stabilize the Gd(III) complexation of porphyrin ligands, it was expected that four cationic N-substituted pyridyl groups will provide water-solubility to the molecules. In the presence of an appropriate length of the alkyl chain (C5 for 1 and C7 for 2) in the carboxylate anchors, relatively stable complexes Gd-1 and Gd-2 were obtained. Based on the stability test of these complexes, Gd-1 showed sufficient stability in aqueous phase at neutral pH, while possessing significant r1 relaxivity and photosensitivity, suggesting that this molecule may be a core of the MRI-PDT-theranostic drugs.

Experimental Section

Synthesis of 1

To a solution of N,N,N,N-tetra(5-ethoxy-5-oxopentyl)-5,10,15,20-tetra(3-pyridyl)-21H,23H-porphine tetrabromide (S2) (180 mg, 0.124 mmol) in water (4 mL), a solution of LiOH monohydrate (156 mg, 3.72 mmol) in water (2 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h until hydrolysis was completed as monitored by silica gel TLC (saturated KNO3–H2O–MeCN (1:1.5:8)). After the solvent was evaporated, crude mixture was dissolved in MeOH–MeCN (1:1), filtered, concentrated in vacuo, and purified by reversed phase flash chromatography (C18 column with a gradient mixture of MeCN (0.1% TFA)–H2O (0.1% TFA) (5:95 to 95:5) as an eluent). Product was triturated in 5 mL of Et2O to provide a hygroscopic purple powder 1 (151 mg, 0.113 mmol, y = 91%); IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 3320 (N–H), 3048 (C–H), 2933 (C–H), 1661 (C=O), 1503, 1405, 1169, 1110, 977, 912, 827, 797, 719, 692, 680; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δH 10.08 (4H, br s, o-py), 9.59 (4H, d, J = 6.2 Hz, p-py), 9.47 (4H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, o-py), 9.17 (8H, br s, β-pyrrole), 8.65 (4H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, m-py), 5.02–5.08 (8H, m, NCH2CH2CH2CH2), 2.49–2.59 (8H, m, NCH2CH2CH2CH2), 2.32–2.46 (8H, m, NCH2CH2CH2CH2), 1.85–1.96 (8H, m, NCH2CH2CH2CH2); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δC 175.26, 148.58, 147.08, 144.63, 141.75, 138.46, 128.13, 126.80, 113.06, 61.91, 48.23, 32.48, 30.60, 21.12; HRMS (MALDI/ESI+) m/z calcd for [C60H63N8O8]+: 1023.4763, found: 1023.4755 ([M + H]+); UV–vis: λmax [nm] (ε [M–1cm–1]): 419 (236 000), 516 (13 000), 553 (2400), 584 (4700), 647 (628).

Synthesis of Gd-1

To a solution of compound 1 (15 mg, 0.011 mmol) in water (4 mL, adjusted to pH 6.3), Gd2O3 (425 mg, 1.17 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 68 h at pH 6.3. The reaction process was monitored by UV–vis spectroscopy. After completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and filtered through a syringe filter (0.45 μm) to remove excess Gd2O3. Subsequently, the pH was adjusted to 9.0 to precipitate Gd(OH)3, which was filtered off (0.45 μm syringe filter). The pH of the solution was adjusted to 7.0 and filtered and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The obtained crude mixture was purified by SEC (Sepharose CL-4B) with an eluent of Milli-Q water to remove a trace amount of starting material and then Milli-Q water containing 0.1% Et3N to elute the product. Product was triturated with Et2O to provide a hygroscopic bright red powder Gd-1 (13.1 mg, 0.0105 mmol, y = 93%); IR (ATR) νmax [cm–1]: 3094 (C–H), 2959 (C–H), 1677 (C=O), 1565, 1422, 1353, 1193, 1177, 1125, 1104, 960, 836, 798, 720, 680, 519; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for [C60H57Gd1N8O8]2+: 587.6765, found: 587.6778 ([M + H]2+); UV–vis: λmax [nm] (ε [M–1cm–1]): 429 (184 000), 517 (3700), 556 (11 300), 588 (2700).

Synthesis of 2

To a solution of S4 (33 mg, 0.021 mmol) in water (2 mL), a solution of LiOH monohydrate (26.5 mg, 0.63 mmol) in water (1 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature, and the reaction was monitored by a silica gel TLC (saturated KNO3–H2O–MeCN (1:1.5:8)) to observe the completion of hydrolysis after 4 h. After the solvent was evaporated, the crude mixture was dissolved in a mixture of MeOH and MeCN (1:1) and filtered, and solvents were concentrated in vacuo. The crude mixture was purified by reverse phase chromatography in the same manner as for 1 above. The product was triturated in 5 mL of Et2O to provide a hygroscopic purple powder 2 (26.5 mg, 0.018 mmol, y = 86%); IR (ATR) νmax [cm–1]: 3317 (N–H), 3052 (C–H), 2936 (C–H), 2864, 1672 (C=O), 1636 (C=O), 1562 (C–N), 1511, 1458, 1404, 1198, 1174, 1128, 970, 799, 719; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δH 9.50 (8H, dd, J = 6.5 and 3.7 Hz, o-py), 9.16 (8H, brs, β-pyrrole), 9.02 (8H, d, J = 6.5 Hz, m-py), 5.04 (8H, t, J = 7.7 Hz, NCH2), 2.36–2.51 (16H, m, NCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH2), 1.61–1.86 (24H, m, NCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH2); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δC 176.11, 158.38, 158.13, 143.26, 143.20, 143.17, 132.98, 129.85, 129.73, 115.67, 115.23, 61.81, 33.29, 31.10, 28.25, 25.73, 24.35; HRMS (MALDI/ESI+) m/z calcd for [C68H79N8O8]+: 1135.6015, found: 1135.6013 ([M + H])+; UV–vis: λmax [nm] (ε [M–1cm–1]): 425 (131 000), 520 (11 000), 558 (5300), 586 (5300), 641 (2086).

Synthesis of Gd-2

To a solution of compound 2 (14 mg, 0.0097 mmol) in water (7 mL, adjusted to pH 6.3), Gd2O3 (280 mg, 0.77 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was refluxed for 96 h at pH 6.3. The reaction process was monitored by UV–vis spectroscopy. After completion of the reaction, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and filtered through a syringe filter (0.45 μm) to remove excess Gd2O3. A further purification process was performed in the same manner as Gd-1 above to provide a hygroscopic brown powder Gd-2 (2.8 mg, 0.0021 mmol, y = 21%); IR (ATR) νmax [cm–1]: 3119, 3052 (C–H), 2938 (C–H), 2863, 1675 (C=O), 1634 (C=O), 1558 (C–N), 1409, 1201, 1173, 1123, 999, 836, 799, 720; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for [C68H74Gd1N8O8]3+: 429.4957, found: 429.4957 ([M + 2H]3+); UV–vis: λmax [nm] (ε [M–1cm–1]): 436 (162 000), 525 (3500), 561 (13 500).

ICP-OES Measurement

ICP-OES measurements were performed to quantify the Gd content and to gain information concerning the stoichiometry of the complex. An aqueous solution of Gd-1 was diluted and digested in 2% HNO3 solution prior to the ICP-OES analysis. As standard, a 1000 ppm solution of Gd(III) in 2% HNO3 was diluted to 50–2000 ppb and used for the calibration. Measurements were performed on an Ultima Expert ICP-OES (Horiba Ltd., Kyoto, Japan).

Relaxometric Measurements

1H NMRD (nuclear magnetic relaxation dispersion) profiles of aqueous 1.97 mM Gd-1 solution (pH = 7.0) were measured at 25 and 37 °C on a Stelar SMARtracer Fast Field Cycling NMR relaxometer (0.00024–0.24 T, 0.01–10 MHz 1H Larmor frequency) (Sterlar s.r.l, Mede, Italy) and a Bruker WP80 NMR electromagnet adapted to variable-field measurements (0.47–1.88 T, 20–80 MHz) and controlled by the SMARtracer PC-NMR console. The temperature was controlled by a VTC91 temperature control unit and maintained by a gas flow. The temperature was determined according to previous calibration with a Pt resistance temperature probe. The Gd3+ concentration of the sample was verified by ICP-OES measurement. The relaxivity at 400 MHz was determined on a Bruker Advanced NMR spectrometer.

17O NMR Studies

Variable-temperature 17O NMR measurements of an aqueous solution of Gd-1 were performed on a Bruker Advanced 400 MHz spectrometer using a 10 mm BBFO probe (9.4 T, 54.2 MHz) in the temperature range of 5–75 °C. The temperature was calculated according to published calibration routines with ethylene glycol and MeOH. Acidified water (HClO4, pH 3.3) was used as a diamagnetic reference. Transverse 17O relaxation times were obtained by the Carl-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill spin–echo technique, and longitudinal relaxation rates were measured by an inversion recovery method. To eliminate susceptibility corrections to the chemical shifts, the sample was placed in a glass sphere fixed in a 10 mm NMR tube. To improve sensitivity, H217O (10% H217O, CortecNet) was added to achieve ∼1% 17O content in the sample. The pH of the sample was 7.0, and the Gd-1 complex concentration was 6.75 mmol·kg–1.

DNA Cleavage Assay

The supercoiled pBR322 DNA (New England Biolabs) was used as a substrate. A mixture of pBR322 DNA (12.5 μg·mL–1) and Gd-1 (0.1 mM) in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) was placed in the 96-well micro plate and irradiated with a green LED light (dominate wavelength: 527 nm, 25 mW per well) using a Lumidox Gen II Apparatus (Analytical Sales & Services, Inc., Franders, NJ, USA). Each sample was mixed with Gel Loading Dye Purple (New England Biolabs, Inc.) and subjected to the agarose gel electrophoresis. Subsequently, the gel was stained with GelRed Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Biotium, Inc., Fremont, California, USA) and visualized and photographed using a ChemiDoc MP transilluminator (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, California, USA). The photographed images were analyzed using ImageJ33 to quantify the relative amount of intact DNA (Form I) and nicked circular DNA (Form II).

ESR Spin-Trapping Method for the Detection of 1O2

The generation of 1O2 was detected by an ESR method using 4-oxo-TEMP as a spin-trapping reagent. Rose Bengal was used as a standard 1O2 generator. To a 20 μL solution of each porphyrin (0.5 mM in D2O), 4 μL of 4-oxoTEMP (0.5 M in D2O), 10 μL of phosphate buffer (pH 7, 0.3 M in D2O), and D2O (16 μL) were added and mixed well under an aerobic condition. Each mixture was irradiated by green LED light at a distance of 3 cm for 0, 1, 2, 5, and 10 min and immediately subjected to ESR measurement. The generation of 1O2 was detected by an ESR signal of 4-oxo-TEMPO, formed by the reaction of 1O2 and 4-oxo-TEMP.

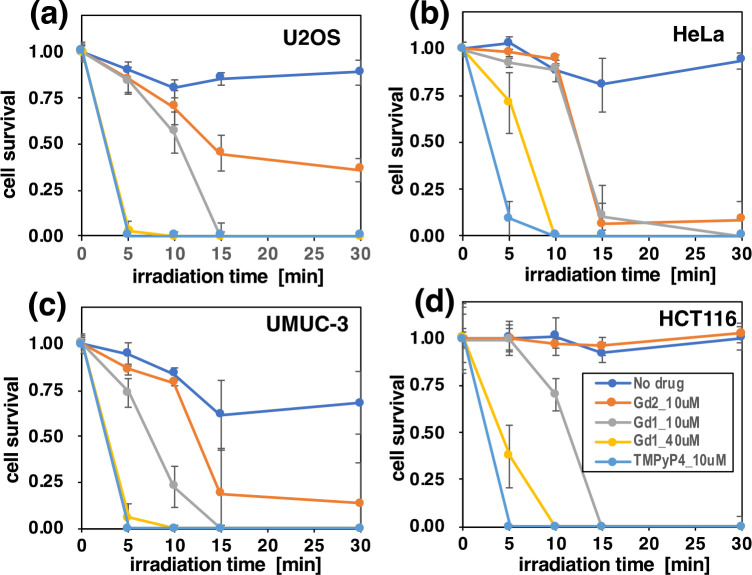

Photocytotoxicity Assay

After preincubation for 24 h, cells (U2OS, HeLa, UMUC-3, and HCT116) were exposed to the chemicals (Gd-1: 10 or 40 μM, Gd-2: 10 μM, or TMPyP4:10 μM) solubilized in culture medium (100 μL) for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were washed twice with PBS(−) and were exposed to green LED using Lumidox II illuminator (527 nm, 95 mW per well, Analytical Sales and Services, Inc.) for 0 to 30 min. Cells were incubated in fresh medium for an additional 24 h, and cell viability was tested by the MTS assay (CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega).

Results and Discussion

Design and Synthesis of Ligands 1 and 2 and Their Gd(III) Complexes (Gd-1 and Gd-2)

The lengths of alkyl anchors with carboxylate termini in the porphyrin-based ligands 1 and 2 were selected with the aid of molecular modeling to afford the highest complexation stability in the corresponding Gd(III) chelates Gd-1 and Gd-2 (Table S1, Section 1 in the SI).34,35 Compounds 1 and 2 were synthesized from tetrapyridylporphyrins (S1 and S3) as starting materials. The N atoms of S1 or S3 at meta or para position were alkylated by the corresponding bromide with terminal ethyl ester to provide S2 or S4 (Schemes S1 and S2, Section 2 in the SI). After subsequent deprotection of the terminal carboxylates by LiOH, ligands 1 and 2 were obtained and purified by reversed phase HPLC. The final Gd(III)-chelation step was performed by refluxing the ligand 1 or 2 in the presence of an excess amount of Gd2O3 in aqueous solution (pH 6.3) for 3 or 5 days. After the reaction completed, the remaining free Gd3+ was removed as precipitates of Gd(OH)3 at pH 9 together with excess Gd2O3 precipitates. The resulting Gd(III) complexes Gd-1 and Gd-2 were further purified by Sepharose CL-4B size exclusion chromatography (SEC) using water (in the presence of 0.1% Et3N) as an eluent. The obtained fractions corresponding to complexes Gd-1 and Gd-2 were collected and analyzed by HR-ESI-MS (Figure S11 and S24 in the SI), which provided molecular ion peaks, respectively, at [M + H]2+ for Gd-1 and [M+2H]3+ for Gd-2, indicating that both complexes contained 1 atom of Gd3+ per porphyrin ligand molecule (1 or 2). It was also confirmed that there was no peak corresponding to free porphyrin ligand (1 or 2) nor to other complexes with multiple numbers of Gd3+ atoms per ligand observed in the ESI-MS spectra. The results indicated that the fraction obtained by SEC purification was sufficiently pure without containing any free ligand or different mode of Gd(III) complexes (e.g., 1 to 2 complexation of Gd3+ and porphyrin ligands). The one-to-one complexation mode of Gd-1 was also confirmed by ICP-OES for the quantification of Gd amount to further indicate that the purity of the complex was >99% (for details, see Section 3 in the SI).

Figure 2 shows normalized UV–vis absorption spectra of free ligands (1 and 2) and their complexes (Gd-1 and Gd-2). Upon Gd(III) complexation, clear changes in Q-bands were observed in both Gd-1 and Gd-2. Changes in the four Q-bands of 1 (516, 553, 584, and 647 nm) and 2 (520, 558, 586, and 641 nm) to the ones for Gd(III) chelates (Gd-1: 517, 556, and 588 nm; Gd-2: 525 and 561 nm) indicated that the metal complexation with ligands 1 and 2 involved coordination via the pyrrolic nitrogen atoms at the porphyrin center. In addition, the observed red shift of the Soret bands (from 419 to 429 nm and from 425 to 436 nm, respectively, for Gd-1 and Gd-2) suggested that the metalation proceeded with a sitting atop (SAT) structure.36,37 The complexation was also investigated by FT-IR-ATR measurements in the solid state (Figure S25). The bands corresponding to the N–H stretches, observed in free ligands 1 and 2 at 3320 and 978 or at 3317 and 980 cm–1, respectively (Figure S25a,c), were not observed in complexes Gd-1 and Gd-2 (Figure S25b,d). This further indicates that the metal was coordinated to the porphyrin core through the central N atoms. Simultaneously, two additional peaks were observed upon complexation at ca. 1560–1565 and 1410–1420 cm–1, presumably related to Gd(III) complexation by the terminal carboxylic acid groups of the anchors connected to the pyridyl nitrogen atoms. In comparison to 1 and Gd-1, the spectra of 2 and Gd-2 were much broader, presumably related to the increased aggregation of 2 and Gd-2. This may be due to the geometrically favorable cation−π interaction of the para position that is observed for other water-soluble porphyrins with cations at the para position.

Figure 2.

UV–vis spectra of porphyrin ligands 1 and 2 and their corresponding Gd(III) complexes Gd-1 and Gd-2 in HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) at 12.5 μM.

Stability of Gd-1 and Gd-2

During the purification step of each complex by SEC, Gd-2 was obtained in rather low yield (21%), presumably due to partial decomplexation during chromatography. In contrast, Gd-1 was obtained with an excellent yield (93%), probably due to its higher stability in comparison to Gd-2. There was a clear difference in the stability of Gd-1 and Gd-2 in pH 5.5 phosphate buffer; while complex Gd-2 was immediately decomplexed (data not shown), complex Gd-1 was stable in the same buffer for at least 1 h as observed by UV–vis spectra.

The stability of complex Gd-1 in aqueous solution was assessed in more detail by UV vis measurements (Figures S26–S35). While Gd-1 was stable in pH 5.5 phosphate buffer for a short interval (1 h), decomplexation of Gd-1 was prevalent after 24 h (Figure S26a). The further stability tests of Gd-1 at higher pH showed, however, that this complex was stable at pH 6.8, 7.4, and 9.4 (in HEPES buffer) at least for 168 h (Figure S26b–d). In the experiments in phosphate buffer at pH 6.0, 6.4, 6.6, and 6.8 and in citrate buffer at pH 6.5 and 6.8, the spectral changes corresponding to the partial decomplexation were observed below pH 6.5, indicating that the complex Gd-1 was sufficiently stable at pH 6.8 or higher (Figures S27–28). The repeated thermal hysteresis (repeated cycles of 50 and 4 °C for 30 min each) did not cause any decomplexation of Gd-1 (Figure S29). We found that decomplexation of Gd-1 took place at pH 7.0 in the presence of one equivalent of Zn(II) or complexing agent EDTA, which were observed as a drop of relaxivity at 60 MHz (Figure S37). The addition of a large excess of sodium citrate tribasic and other competing metal ions such as Ca(II) and Mg(II) did not affect the stability of Gd-1 (Figures S30–S33). Storing at higher concentration (45 mM) at 4 °C in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) did not cause any significant decomplexation or increased aggregation of Gd-1 at least for 72 h (Figure S34). Further, we have confirmed that Gd-1 was stable at pH 7.0 under visible light irradiation conditions (528 nm) in the presence of oxygen (Figure S35).

Relaxivity Measurements of Gd-1

Based on the sufficient stability shown above, the paramagnetic relaxation enhancement properties of Gd-1 were evaluated by relaxivity measurements at variable magnetic fields (0.01–400 MHz) and at two temperatures (25 and 37 °C, Figure 3). Proton relaxivity is defined as the paramagnetic enhancement of the water proton relaxation rate referred to 1 mM Gd(III) concentration, and it directly translates to MRI efficiency. Relaxivity is dependent on a large number of parameters, the most important being the number of water molecules directly coordinated to the metal ion (hydration number, q), the exchange rate of this water with the bulk (kex), and the rotational correlation time of the complex (τR). The relaxivity values are remarkably high for Gd-1; at 20 MHz and 37 °C, r1 is about four times higher than that of typical small molecular weight complexes such as the clinical agent GdDOTA (Table 1). The shape of the NMRD profiles, with a bump centered at ∼60 MHz, qualitatively indicates that rotation is slower than expected for a small molecular weight complex. This is likely a consequence of an aggregation phenomenon in the solution, which is commonly observed even for water-soluble porphyrins. Indeed, the same observation was previously reported for porphyrins decorated with Gd(III) complexes.13,22−24

Figure 3.

(a) Transverse (red ◆) and longitudinal (blue ▲) 17O reduced relaxation rates and (b) reduced 17O chemical shifts measured in a Gd-1 solution at 6.75 mM, pH 7. (c) 1H NMRD profiles of the Gd-1 complex (1.97 mM in 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.3)) recorded at 37 °C (green ●) and at 25 °C (black ●). The lines correspond to the fit as explained in the text.

Table 1. Experimental Relaxivities, r1, and Calculated Parameters Characterizing the Water Exchange and the Rotational Dynamics of Gd-1 in an Aggregated State and the Small Molecular Weight Reference Compound GdDOTA.

| Gd-1a | GdDOTAb | |

|---|---|---|

| r1 (20 MHz, 37 °C) [mM–1 s–1] | 15.46 | 3.83 |

| kex298 [s–1] | (8.1 ± 0.5) × 106 | 4.1 × 106 |

| ΔH‡ [kJ/mol] | 27.5 ± 0.5 | 49.8 |

| τR [ps] | 850 ± 35 (from NMRD) | 77 |

| 930 ± 28 (from 17O NMR) | ||

| ER/kJ/mol | 28.1 ± 0.5 | 16.1 |

This work.

Ref (38).

For a better analysis of the relaxivities, the NMRD (Nuclear Magnetic Relaxation Dispersion) data have been complemented by a variable temperature 17O NMR study that allowed the direct assessment of the water exchange and the rotational dynamics of Gd-1, two features directly interfering in the relaxation efficiency of paramagnetic metal chelates. Indeed, the transverse 17O relaxation rates contain information on the water exchange process, while longitudinal 17O relaxation is related to the rotational dynamics of the complex. The reduced transverse (1/T2r) and longitudinal (1/T1r) 17O relaxation rates have been determined for an aqueous solution of Gd-1 (6.75 mM, pH 7). The temperature dependency of 1/T2r indicates that above ∼298 K the system is in the fast exchange regime, while at lower temperatures, it is in the slow exchange regime. The 17O NMR and the NMRD data have been analyzed together by using the Solomon-Bloembergen-Morgan theory of paramagnetic nuclear relaxation24 to obtain the characteristic parameters for the description of the water exchange process (kex298 and the activation enthalpy ΔH‡) and the rotational dynamics (τR298 and the activation energy ER), which are listed in Table 1, together with the corresponding values for GdDOTA. Only the high field relaxivities (>4 MHz) have been included in the analysis. It is common to fit only the high field part of the NMRD profile, as at low magnetic fields, the SBM theory fails in describing electronic parameters and rotational dynamics of slowly rotating objects. In the fit, we assumed one inner sphere water molecule, in accordance with the expected coordination of four porphyrin nitrogens and four carboxylates to the metal ion. The value of the scalar coupling constant calculated is A/ℏ = −3.4 MHz, which is in the usual range for Gd(III) chelates, suggesting that the assumption of one inner sphere water is correct. A complete description of the analysis, including the equations used for the fitting of the experimental 17O and NMRD data as well as the full set of the fitted parameters, can be found in the SI.

The water exchange rate, kex298, is double of that for GdDOTA, but this difference will not affect the relaxivity since it is still limited by rotation. The most important information on this analysis concerns the slow rotational dynamics, confirmed by the value of the rotational correlation time, τR298 = 850 ps. Slow rotation is also indicated by the longitudinal 17O relaxation rates. These were acquired at a higher concentration (6.75 mM) than the NMRD data (1.97 mM), and they indeed provide a slightly longer rotational correlation time, τR298 = 930 ps. We also recorded the relaxivity of Gd-1 at variable concentrations between 0.1 and 6.4 mM and found an important concentration dependency, consistent with aggregation (Figure 4), which was observed also by DLS measurement (Figure S36). Even in the most diluted samples (down to 0.02 mM concentration), the relaxivity continues to decrease with decreasing concentration, suggesting that aggregation is still present. The measurement of relaxivities at lower concentration becomes technically problematic; therefore, we cannot characterize the monomer state. In any case, the slower rotation is responsible for the high relaxivity of the complex. Further, the transverse relaxivity, r2, was measured at two Gd-1 concentrations, at 60 MHz and 25 °C. The values are the following: r2 = 27.0 mM–1 s–1 and r1 = 21.4 mM–1 s–1 at 4.8 mM and r2 = 23.9 mM–1 s–1 and r1 = 19.4 mM–1 s–1 at 2.4 mM concentration.

Figure 4.

Concentration-dependent relaxivity change of Gd-1 (60 MHz, 298 K).

Photo DNA Cleavage by Gd-1

For the preliminary evaluation of complex Gd-1 as a PS, photoinduced DNA-cleaving tests were performed under visible light irradiation. A standard assay method using pBR322 supercoiled plasmid DNA was used to evaluate the oxidative damage of DNA by photoexcited Gd-1. A green LED (dominate wavelength: 527 nm, 25 W per well) was used as a light source, where Gd-1 has an absorption intensity. As a result, significant DNA cleavage by Gd-1 was observed in an irradiation-time-dependent manner (lanes 3 and 4, Figure 5). No significant DNA cleavage was observed in the absence of light (lane 2) or Gd-1 (lanes 5 and 6) clearly indicating that photoexicitation of Gd-1 was necessary to cleave DNA.

Figure 5.

Photoinduced DNA cleavage by Gd-1. DNA used in the assay: pBR322 supercoiled DNA (0.125 μg; 6.25 μg·mL–1); Gd-1: 0.1 mM in 15 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0); light irradiation: green-LED (527 nm, 25 W per well) for 5 min (+) or 10 min (++). Form I: intact DNA. Form II: nicked DNA.

ROS Generation by Gd-1 under Photoirradiation

From the DNA cleavage test above, it was expected that reactive oxygen species (ROS), especially singlet oxygen (1O2) generated by type II energy transfer reaction, may act as a key active species to cause the DNA cleavage by the photosensitizers.1,39−41 To confirm this mechanism in the photoinduced DNA cleavage by Gd-1, the ESR spin-trapping methods were employed to detect the ROS generation under irradiation of green LED lights (dominate wavelength: 528 nm; luminous flux: 9 lm).

The generation of 1O2 was evaluated by ESR using 4-oxo-TEMP as a spin-trapping reagent (Figure 6e).42 The complex Gd-2 and free ligands 1 and 2 were also tested for 1O2 generation. Upon green light irradiation, the specific ESR signals corresponding to 4-oxo-TEMPO, the 1O2 adduct of 4-oxo-TEMP, were observed in aqueous solutions of Gd-1 (Figure 6a). The amount of 1O2 generation in Gd-1 was higher than in Gd-2 (Figure 6c) and greater than a positive control Rose Bengal, a well-known 1O2 generator (Figure S38). Interestingly both free ligands 1 and 2 showed higher generation of 1O2 than their corresponding complexes (Figures 6, S38, and S39) presumably due to higher absorption intensity at 527 nm (Figure 2).

Figure 6.

(a–d) X-band ESR spectra for 1O2 adduct of 4-oxo-TEMP (4-oxo-TEMPO) generated from Gd-1 (a), 1 (b), Gd-2 (c), and 2 (d) under photoirradiation. Reaction conditions: Gd-1, 1, Gd-2, or 2: 0.2 mM; 4-oxo-TEMP: 40 mM; in 60 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7, in D2O); light irradiation: green-LED (dominate wavelength: 528 nm; luminous flux: 9 lm) for 10 min. Measurement conditions: temperature 296 K, microwave frequency 9.375 GHz, microwave power 1 mW, modulation amplitude 4.00 G, modulation frequency 100 kHz, scan time 20.5 s. (e) General scheme for the photoinduced DNA cleavage by a photosensitizer (S).

Cytotoxicity

As a preliminary test on the biocompatibility of Gd-1, a cytotoxicity assay was performed. The effects of these complexes on cell growth and cell cycle progression were examined on three types of cancer cell lines: HCT116 (colorectal carcinoma), U2OS (osteosarcoma), and UMUC-3 (bladder carcinoma) by monitoring the increase of the cell numbers (Figure S40). As reference compounds, Gd-2 and tetra N-methyl pyridyl porphyrin (TMPyP4) were used. As results, Gd-1 did not show any effect on cell growth of any tested cell line at the concentration of 1 μM (Figure S40). No effect was observed in UMUC-3 at the concentration of 10 μM, while Gd-1 slightly retarded the cell growth in HCT116 and U2OS. The growth inhibitory effect was smaller than the control experiment with TMPyP4 in UMUC-3 but was bigger than the control TMPyP4 in HCT116 and U2OS. It was technically difficult to estimate the effect of Gd-1 on the cell growth above 10 μM due to its high fluorescent intensity. Interestingly, the Gd-2 complex with lower stability did not show any significant effect on cell growth at the concentrations up to 50 μM in all the cell lines. The effect of TMPyP4 may be related to its function to intercalate into guanine quadruplexes (G4) that may inhibit ongoing DNA replication or could alter the expression of oncogenes known to be regulated by G4 in cancer cells. Similarly, the effect of Gd-1 may also be related to its G4 binding.43 Moreover, taken together with the fact that Gd-1 generated 1O2 much more efficiently than Gd-2 under visible light irradiation (Figure 5), the cell growth inhibition by Gd-1 may be also related to the effect of light, as cells were exposed to traces of light, which could not be avoided during the experimental procedure.

Effect to Cell Cycle Progression

To obtain further insight into the effect of Gd-1 on the cells, the impact on the cell cycle progression was examined by analyzing the DNA contents in U2OS and HeLa (human cervical adenocarcinoma) cells, both of which are commonly used for detection of changes in cell cycle progression (Figure S41).44,45 Cell cycle distributions did not significantly change in the presence of both Gd-1 (10 μM) and Gd-2 (5 μM) in either cell line, indicating that there were little inhibitory effects on DNA replication and on mitotic events by these Gd(III) complexes.

Photocytotoxicity

Finally, photocytotoxicity of Gd-1 was investigated using green LED light on four types of cancer cell lines (U2OS, HeLa, UMU-3, and HCT116). As references, TMPyP4 and Gd-2 were tested. As shown in Figure 7, in all cell lines, both Gd-1 and Gd-2 exhibited significant photocytotoxicity dependent on the time of light irradiation. Among them, Gd-1 showed stronger photocytotoxicity than Gd-2, in line with the results that Gd-1 has a higher ability of 1O2 generation as shown in Figure 5. Gd-1 exhibited photocytotoxicity almost identical with that shown by the control compound TMPyP4, most notably on U2OS, UMU-3, and HCT116. Taking into account that Gd-1 showed low cytotoxicity in the absence of light, it was suggested that Gd-1 can be a good candidate as a core for the PDT-PS molecule.

Figure 7.

Effects of light irradiation on the growth of four types of cancer cells treated with Gd-1, Gd-2, and TMPyP4. Cells (U2OS (a), HeLa (b), UMUC-3 (c), and HCT116 (d)), preincubated with Gd-1 (10 or 40 μM) or Gd-2 (10 μM), were exposed to the green LED light (528 nm, 95 mW per well) for 0, 5, 10, 15, and 30 min and subjected to the MTS assay for measuring the viability. As controls, cells were treated in the absence of drug (no drug) or in the presence of TMPyP4 (10 μM). Values are means ± SD (n = 4). Gray, Gd-1 (10 μM); yellow, Gd-1 (40 μM); orange, Gd-2 (10 μM); light blue, TMPyP4 (10 μM); blue, no drug (negative control).

Conclusions

Two water-soluble porphyrin-based Gd(III) chelates, Gd-1 and Gd-2, were synthesized. The introduction of carboxylate anchors increased the stability of Gd(III)–porphyrins complexes, especially in the case of Gd-1. The 1H NMRD study of Gd-1 showed high r1 relaxivities indicating that Gd-1 has good relaxation efficacy, which is related to the aggregation of the compound in aqueous solution. The complex Gd-1 revealed extensive photoinduced DNA cleavage and 1O2 generation, suggesting that it can be a potential candidate as a PDT-PS drug. Significant cytotoxicity was not observed with Gd-1 in the dark, while clear photocytotoxicity was shown under visible light irradiation. Overall, the Gd-1 complex combines good r1 relaxivity and efficient ROS generation with corresponding photocytotoxicity, important for theranostic drugs for MR image-guided PDT.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Rubi of the MoBiAS in the Department of Chemistry and Applied Biosciences at the ETH Zürich for his support in HR-MALDI-TOF measurements. The authors thank Dr. Liosi and Dr. Fracassi from the ETH Zürich for their help in ESR measurements and relaxivity evaluation. The authors thank Ms. Naoko Kakusho from Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Sciences for conducting FACS cell cycle analyses of cancer cells. The authors thank Prof. Helm in EPFL for his educational discussion. This research was supported in part by the SNF, Strategic Japanese-Swiss Science and Technology Program (IZLJZ2_183660, Y.Y.), JSPS under the Joint Research Program implemented in association with SNF (20191508, H.M. and N.Y.-S.), the SNF Project Funding (205321_173018, Y.Y.), the ETH Research Grant (ETH-21_15-2; ETH-36_20-2, Y.Y.), and JSPS KAKENHI (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research [A], 6251004, H.M.; Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas, 21H00264, 22H04707, H.M.; Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research [C], 15K07164, N.Y.-S.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- LED

light emitting diode

- NADH

nicotine amide adenine dinucleotide

- PDT

photodynamic therapy

- PS

photosensitizer

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- CA

contrast agent

- DTPA

2,2′,2″,2‴-{[(carboxymethyl)azanediyl]bis(ethane-2,1-diylnitrilo)} tetraacetic acid

- DOTA

2,2′,2″,2‴-(1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetrayl)tetraacetic acid

- HR-MALDI-MS

high resolution-matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry

- ICP-OES

inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry

- SAT

sitting atop

- UV–vis

ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- ESR

electron spin resonance spectroscopy

- 4-oxo-TEMP

2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidone

- 4-oxo-TEMPO

4-oxo-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy

- DMPO

5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide

- DETAPAC

diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid

- SEC

size exclusion chromatography

- NMRD

nuclear magnetic relaxation dispersion

- HEPES

diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid

- TMPyP4

meso-5,10,15,20-tetrakis(N-methyl-4-pyridyl) porphyrin

- G4

guanine quadruplex

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cbmi.3c00007.

Additional experimental details on synthesis of Gd-1 and Gd-2 with spectroscopic data including their intermediates; stability test, ICP-OEC analysis, and relaxivity measurements with corresponding equations for Gd-1; photoinduced DNA cleavage test and ROS generation, detailed cell assay tests, and photocytotoxicity for Gd-1 and Gd-2 (PDF)

Author Contributions

N.Y.-S., H.M., and Y.Y. initiated and designed the overall project. T.N. designed the detailed structure of the molecules and carried out the synthesis and characterization of the molecules (1H and 13C NMR, IR, UV, TOF-MS, ICP-OES, stability test, and ROS generation), and Y.M. performed the characterization of Gd-1 (HR-ESI-MS, DLS, photostability, and photo DNA cleavage) in collaboration with E.T., H.M., and Y.Y. E.T. and A.P. carried out the detailed characterization on the relaxivity of the Gd(III) complexes. Y.T. and N.Y.-S. performed the cell assays for the biocompatibility and photocytotoxicity of the Gd(III) complexes in collaboration with H.M.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Baskaran R.; Lee J.; Yang S. G. Clinical Development of Photodynamic Agents and Therapeutic Applications. Biomater. Res. 2018, 22, 25. 10.1186/s40824-018-0140-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowski J. M.; Arnaut L. G. Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) of Cancer: From Local to Systemic Treatment. Photochm. Photobiol. Sci. 2015, 14 (10), 1765–1780. 10.1039/c5pp00132c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolze F.; Jenni S.; Sour A.; Heitz V. Molecular Photosensitisers for Two-Photon Photodynamic Therapy. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53 (96), 12857–12877. 10.1039/C7CC06133A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakoshi Y.Potential of Fullerenes for Photodynamic Therapy Application. In Handbook of Fullerene Science and Technology; Lu X., Akasaka T., Slanina Z., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; 10.1007/978-981-13-3242-5_39-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura Y.; Maeda H. A New Concept for Macromolecular Therapeutics in Cancer-Chemotherapy - Mechanism of Tumoritropic Accumulation of Proteins and the Antitumor Agent Smancs. Cancer Res. 1986, 46 (12), 6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox M. E.; Szoka F. C.; Frechet J. M. J. Soluble Polymer Carriers for the Treatment of Cancer: The Importance of Molecular Architecture. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42 (8), 1141–1151. 10.1021/ar900035f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag R.; Kratz F. Polymer Therapeutics: Concepts and Applications. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2006, 45 (8), 1198–1215. 10.1002/anie.200502113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H. Macromolecular therapeutics in cancer treatment: The EPR Effect and Beyond. J. Controlled Release 2012, 164 (2), 138–144. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chari R. V. J.; Miller M. L.; Widdison W. C. Antibody- Drug Conjugates: An Emerging Concept in Cancer Therapy. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2014, 53 (15), 3796–3827. 10.1002/anie.201307628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casi G.; Neri D. Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Basic Concepts, Examples and Future Perspectives. J. Controlled Release 2012, 161 (2), 422–428. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farokhzad O. C.; Langer R. Impact of Nanotechnology on Drug Delivery. ACS Nano 2009, 3 (1), 16–20. 10.1021/nn900002m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwitniewski M.; Juzeniene A.; Glosnicka R.; Moan J. Immunotherapy: A Way to Improve the Therapeutic Outcome of Photodynamic Therapy?. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2008, 7 (9), 1011–1017. 10.1039/b806710d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sour A.; Jenni S.; Orti-Suarez A.; Schmitt J.; Heitz V.; Bolze F.; de Sousa P. L.; Po C.; Bonnet C. S.; Pallier A.; Toth E.; Ventura B. Four Gadolinium(III) Complexes Appended to a Porphyrin: A Water-Soluble Molecular Theranostic Agent with Remarkable Relaxivity Suited for MRI Tracking of the Photosensitizer. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55 (9), 4545–4554. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami L. N.; White W. H.; Spernyak J. A.; Ethirajan M.; Chen Y. H.; Missert J. R.; Morgan J.; Mazurchuk R.; Pandey R. K. Synthesis of Tumor-Avid Photosensitizer-Gd(III)DTPA Conjugates: Impact of the Number of Gadolinium Units in T-1/T-2 Relaxivity, Intracellular localization, and Photosensitizing Efficacy. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010, 21 (5), 816–827. 10.1021/bc9005305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spernyak J. A.; White W. H.; Ethirajan M.; Patel N. J.; Goswami L.; Chen Y. H.; Turowski S.; Missert J. R.; Batt C.; Mazurchuk R.; Pandey R. K. Hexylether Derivative of Pyropheophorbide-a (HPPH) on Conjugating with 3Gadolinium(III) Aminobenzyldiethylenetriaminepentaacetic Acid Shows Potential for in Vivo Tumor Imaging (MR, Fluorescence) and Photodynamic Therapy. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010, 21 (5), 828–835. 10.1021/bc9005317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y.; Zong H.; Trivedi E. R.; Vesper B. J.; Waters E. A.; Barrett A. G. M.; Radosevich J. A.; Hoffman B. M.; Meade T. J. Synthesis and Characterization of New Porphyrazine-Gd(III) Conjugates as Multimodal MR Contrast Agents. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010, 21 (12), 2267–2275. 10.1021/bc1002828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J.; Chen L. F.; Hu P.; Chen Z. N. Tetranuclear Gadolinium(III) Porphyrin Complex as a Theranostic Agent for Multimodal Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53 (8), 4184–4191. 10.1021/ic500238s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydın Tekdas D.; Garifullin R.; Senturk B.; Zorlu Y.; Gundogdu U.; Atalar E.; Tekinay A. B.; Chernonosov A. A.; Yerli Y.; Dumoulin F.; Guler M. O.; Ahsen V.; Gurek A. G. Design of a Gd-DOTA-Phthalocyanine Conjugate Combining MRI Contrast Imaging and Photosensitization Properties as a Potential Molecular Theranostic. Photochem. Photobiol. 2014, 90 (6), 1376–1386. 10.1111/php.12332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon-Ur-Rashid; Umar M. N.; Khan K.; Anjum M. N.; Yaseen M. Synthesis and relaxivity measurement of porphyrin-based Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) contrast agents. J. Struct. Chem. 2014, 55 (5), 910–915. 10.1134/S0022476614050163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ke X. S.; Tang J.; Yang Z. S.; Zhang J. L. Beta-Conjugation of Gadolinium(III) DOTA Complexes to Zinc(II) Porpholactol as Potential Multimodal Imaging Contrast Agents. J. Porphyrin Phthalocyanin 2014, 18 (10–11), 950–959. 10.1142/S1088424614500758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuzhakova D. V.; Lermontova S. A.; Grigoryev I. S.; Muravieva M. S.; Gavrina A. I.; Shirmanova M. V.; Balalaeva I. V.; Klapshina L. G.; Zagaynova E. V. In Vivo Multimodal Tumor Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy with Novel Theranostic Agents Based on the Porphyrazine Framework-Chelated Gadolinium (III) Cation. BBA-Gen. Subjects 2017, 1861 (12), 3120–3130. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenni S.; Bolze F.; Bonnet C. S.; Pallier A.; Sour A.; Toth E.; Ventura B.; Heitz V. Synthesis and In Vitro Studies of a Gd(DOTA)-Porphyrin Conjugate for Combined MRI and Photodynamic Treatment. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59 (19), 14389–14398. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c02189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt J.; Jenni S.; Sour A.; Heitz V.; Bolze F.; Pallier A.; Bonnet C. S.; Toth E.; Ventura B. A Porphyrin Dimer-GdDOTA Conjugate as a Theranostic Agent for One- and Two-Photon Photodynamic Therapy and MRI. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018, 29 (11), 3726–3738. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt J.; Heitz V.; Sour A.; Bolze F.; Kessler P.; Flamigni L.; Ventura B.; Bonnet C. S.; Toth E. A Theranostic Agent Combining a Two-Photon-Absorbing Photosensitizer for Photodynamic Therapy and a Gadolinium(III) Complex for MRI Detection. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22 (8), 2775–2786. 10.1002/chem.201503433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashino T.; Nakatsuji H.; Fukuda R.; Okamoto H.; Imai H.; Matsuda T.; Tochio H.; Shirakawa M.; Tkachenko N. V.; Hashida M.; Murakami T.; Imahori H. Hexaphyrin as a Potential Theranostic Dye for Photothermal Therapy and F-19 Magnetic Resonance Imaging. ChemBioChem. 2017, 18 (10), 951–959. 10.1002/cbic.201700071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm L.; Merbach A. E.; Tóth E. v.. The chemistry of contrast agents in medical magnetic resonance imaging, Second ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, 2013; p xvi, 496 pages. [Google Scholar]

- Clough T. J.; Jiang L. J.; Wong K. L.; Long N. J. Ligand Design Strategies to Increase Stability of Gadolinium-Based Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agents. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1420. 10.1038/s41467-019-09342-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelovski G. What We Can Really Do with Bioresponsive MRI Contrast Agents. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2016, 55 (25), 7038–7046. 10.1002/anie.201510956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Meade T. J. Molecular Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Gd(III)-Based Contrast Agents: Challenges and Key Advances. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (43), 17025–17041. 10.1021/jacs.9b09149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang L. X.; Zhao H. M.; Hua J. Y.; Qin F.; Zheng Y. D.; Zhang Z. G.; Cao W. W. Water-Soluble Gadolinium Porphyrin as a Multifunctional Theranostic Agent: Phosphorescence-Based Oxygen Sensing and Photosensitivity. Dyes Pigments 2017, 142, 465–471. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2017.03.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B.; Li X. Q.; Huang T.; Lu S. T.; Wan B.; Liao R. F.; Li Y. S.; Baidya A.; Long Q. Y.; Xu H. B. MRI-Guided Tumor Chemo-Photodynamic Therapy with Gd/Pt Bifunctionalized Porphyrin. Biomater. Sci. 2017, 5 (9), 1746–1750. 10.1039/C7BM00431A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y. Metalloporphyrins and Functional Analogues as MRI Contrast Agents. Curr. Med. Imaging 2008, 4 (2), 96–112. 10.2174/157340508784356789. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. A.; Rasband W. S.; Eliceiri K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9 (7), 671–5. 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger Release 2019-3: MacroModel; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, 2019.

- Harder E.; Damm W.; Maple J.; Wu C.; Reboul M.; Xiang J. Y.; Wang L.; Lupyan D.; Dahlgren M. K.; Knight J. L.; Kaus J. W.; Cerutti D. S.; Krilov G.; Jorgensen W. L.; Abel R.; Friesner R. A. OPLS3: A Force Field Providing Broad Coverage of Drug-like Small Molecules and Proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12 (1), 281–96. 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath O.; Huszank R.; Valicsek Z.; Lendvay G. Photophysics and Photochemistry of Kinetically Labile, Water-Soluble Porphyrin Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250 (13–14), 1792–1803. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca G.; Romeo A.; Scolaro L. M.; Ricciardi G.; Rosa A. Sitting-Atop Metallo-Porphyrin Complexes: Experimental and Theoretical Investigations on Such Elusive Species. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48 (17), 8493–8507. 10.1021/ic9012153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell D. H.; Dhubhghaill O. M. N.; Pubanz D.; Helm L.; Lebedev Y. S.; Schlaepfer W.; Merbach A. E. Structural and Dynamic Parameters Obtained from 17O NMR, EPR, and NMRD Studies of Monomeric and Dimeric Gd3+ Complexes of Interest in Magnetic Resonance Imaging: An Integrated and Theoretically Self Consistent Approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118 (39), 9333–9346. 10.1021/ja961743g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista M. S.; Cadet J.; Di Mascio P.; Ghogare A. A.; Greer A.; Hamblin M. R.; Lorente C.; Nunez S. C.; Ribeiro M. S.; Thomas A. H.; Vignoni M.; Yoshimura T. M. Type I and Type II Photosensitized Oxidation Reactions: Guidelines and Mechanistic Pathways. Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93 (4), 912–919. 10.1111/php.12716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakoshi Y.; Umezawa N.; Ryu A.; Arakane K.; Miyata N.; Goda Y.; Masumizu T.; Nagano T. Active Oxygen Species Generated from Photoexcited Fullerene (C60) as potential medicines: O2–-• versus 1O2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125 (42), 12803–12809. 10.1021/ja0355574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liosi K.; Stasyuk A. J.; Masero F.; Voityuk A. A.; Nauser T.; Mougel V.; Sola M.; Yamakoshi Y. Unexpected Disparity in Photoinduced Reactions of C60 and C70 in Water with the Generation of O2–-• or 1O2. JACS Au 2021, 1 (10), 1601–1611. 10.1021/jacsau.1c00239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lion Y.; Delmelle M.; Vandevorst A. New Method of Detecting Singlet Oxygen Production. Nature 1976, 263 (5576), 442–443. 10.1038/263442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In our preliminary results, it was shown that Gd-1 reveals stabilization of some of the G4 motifs such as a c-MYC-derived G4 sequence (data is not shown).

- Yoshizawa-Sugata N.; Masai H. Human Tim/Timeless-Interacting Protein, Tipin, is Required for Efficient Progression of S Phase and DNA Replication Checkpoint. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282 (4), 2729–40. 10.1074/jbc.M605596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa-Sugata N.; Masai H. Roles of Human AND-1 in Chromosome Transactions in S Phase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284 (31), 20718–20728. 10.1074/jbc.M806711200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.