Abstract

ICP8 is the major single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) binding protein of the herpes simplex virus type 1 and is required for the onset and maintenance of viral genomic replication. To identify regions responsible for the cooperative binding to ssDNA, several mutants of ICP8 have been characterized. Total reflection X-ray fluorescence experiments on the constructs confirmed the presence of one zinc atom per molecule. Comparative analysis of the mutants by electrophoretic mobility shift assays was done with oligonucleotides for which the number of bases is approximately that occluded by one protein molecule. The analysis indicated that neither removal of the 60-amino-acid C-terminal region nor Cys254Ser and Cys455Ser mutations qualitatively affect the intrinsic DNA binding ability of ICP8. The C-terminal deletion mutants, however, exhibit a total loss of cooperativity on longer ssDNA stretches. This behavior is only slightly modulated by the two-cysteine substitution. Circular dichroism experiments suggest a role for this C-terminal tail in protein stabilization as well as in intermolecular interactions. The results show that the cooperative nature of the ssDNA binding of ICP8 is localized in the 60-residue C-terminal region. Since the anchoring of a C- or N-terminal arm of one protein onto the adjacent one on the DNA strand has been reported for other ssDNA binding proteins, this appears to be the general structural mechanism responsible for the cooperative ssDNA binding by this class of protein.

Single-stranded (ssDNA) DNA binding proteins (SSBs) bind preferentially ssDNA in stoichiometric quantities with respect to their substrate, displaying little sequence preference and no associated ATPase activity (11). The binding is typically cooperative, though the level of cooperativity varies widely. Much effort has been spent on elucidation of the structural mechanism accounting for the cooperativity and its functional implications in the case of the filamentous phage GVP (6, 68), the phage T4 gp32 (10, 33), the adenovirus DNA binding protein (DBP) (34), the Escherichia coli SSB (19, 42), and the eukaryotic replication protein A (30, 31), while little is known about the SSBs of the Herpesviridae.

The herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) SSB, infected cell polypeptide 8 (ICP8), is a 128-kDa nuclear zinc metalloprotein encoded by the UL29 gene (22). By virtue of its ability to bind oligonucleotide as well as to mediate specific protein-protein interactions, it was shown to have essential functions in DNA metabolism during the viral lytic cycle. ICP8 is one of the seven β, or delayed-early, genes required for viral genome replication, which proceeds via a rolling circle mechanism (63, 65). Replication occurs in globular nuclear domains termed replication compartments (55) whose location is defined by the preexisting host cell nuclear architecture, most probably at the periphery of the nuclear matrix-associated ND10 domains, where the viral transactivator ICP0 and the viral input genome migrate in the early stages of infection (43, 47). Evidence has been provided that the seven essential proteins, the origin binding protein (OBP), the polymerase with its processivity factor (UL30 and UL42), the trimeric primase-helicase complex (UL52, UL5, and UL8), and ICP8, accumulate in punctuate prereplicative sites for the assembly of the multiprotein complex, or primosome, which promotes efficient genomic replication (40, 71, 76). During initiation, ICP8 associates with the carboxy-terminal domain of the OBP at the origin of replication to assist the ATP-dependent bidirectional origin unwinding (3, 36, 37, 45). It enhances the polymerase processivity (29, 50, 61) and stimulates the helicase-primase activity via interaction with the UL8 subunit (4, 17, 21). In accord with its ability to destabilize DNA helices (5) and promote Mg-dependent complementary-strand renaturation (16), ICP8 can catalyze homologous pairing and strand transfer (7), and hence it participates in the frequent DNA recombination events. Genetic evidence implies a role for ICP8 in the regulation of viral gene expression (12, 26), in agreement with the reported ICP8 affinity for polyriboadenylate (61).

The DNA binding properties of ICP8 have been extensively investigated. ICP8 binds ssDNA rapidly and cooperatively, with a modest preference for the HSV genomic GC-rich sequences, holding the nucleotide filaments in an extended conformation (35, 58). Optimal binding occurs at neutral pH and 150 mM salt concentration (61). Based on filter binding assays (58), nuclease protection (28), renaturation (16) or strand displacement (5) experiments, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) (15), polymerase (29) or OBP (3) stimulation, and electron microscopy (45), several different binding site sizes have been reported, ranging from 12 to 40 nucleotides per monomer. The lack of consensus may result from differences in experimental techniques, although we cannot rule out the possibility of different binding modes as exhibited by several other SSBs (1, 2, 9, 32). The affinity for short oligonucleotides was estimated by dialysis (59) and EMSA to be in the order of 105 to 106 M−1, and only recently a cooperativity parameter of 40 was calculated for the binding of ICP8 to (dT)50 (15). Binding to double-stranded DNA has also been detected, albeit with much lower affinity, but the biological significance of this is unclear (35).

To better understand the various functions of ICP8, a number of studies designed to identify the region involved in protein-nucleotide and the several intermolecular interactions described above have been performed. Genetic analysis led to the positioning of the nuclear localization signal (NLS) at the carboxy terminus (23). The 28-amino-acid C-terminal fragment is necessary to direct the protein into the nucleus, though other regions on the amino-terminal half of the molecule can serve as minor signals. Replacement of these 28 residues by the simian virus 40 T-antigen NLS restores the ICP8 nuclear localization but results in a mutant virus defective in viral replication and late gene expression, suggesting an involvement of this C-terminal tail in some intermolecular contacts responsible for the correct primosome assembly or functioning (25). Absence of 36 C-terminal residues leaves ssDNA binding intact, but further truncation to residue 1029 significantly reduces the nucleotide binding affinity (24).

Limited proteolytic analysis (72) coupled with the characterization of temperature-sensitive (22) and deletion (24, 38, 39) mutants suggests putative boundaries of the minimal binding domain between residues 300 and 849, while more recent evidence, based on ICP8 photoaffinity labeling with oligonucleotides, indicated a slightly different region, namely, between residues 386 and 902 (73). Both stretches encompass a zinc finger motif predicted between amino acids 499 and 512, where the single ICP8 zinc atom is most likely bound. The zinc confers structural integrity to the protein without being directly involved in contacts with nucleotides (27). Despite the lack of sequence similarity among SSBs, alignments based on known phage, viral, prokaryotic, and eukaryotic β-strand structures (53, 54, 57, 67) highlight the presence of well-conserved aromatic and basic residues able to mediate protein-nucleic acid contacts via stacking and electrostatic interactions. In the case of ICP8, it was shown that lysines accessible to chemical modification are involved in DNA binding and that the fluorescence of tryptophans undergoes quenching upon nucleotide interaction (60). In addition, iodination of tyrosines appears to decrease the cooperativity of DNA binding (60). Biochemical evidence from N-ethylmaleimide-modified ICP8 suggested a very specific role for free sulfhydryls in the cooperative nature of the binding (59). Initially sequence analysis pointed to a C-terminal cysteine cluster as responsible for the intermolecular interactions occurring between adjacent molecules covering the same strand. More recently, fluorescein-5-maleimide modification of the protein allowed the identification of two cysteines mapped at positions 254 and 455 as major effectors of cooperative binding (15).

To define the molecular basis of the interaction between ICP8 and ssDNA and to gain further insight into the details governing the typical cooperative nature of the binding, more biochemical information is required. In this report we present EMSA characterization of the oligonucleotide binding affinity of a double-point mutant in which cysteines 254 and 455 were replaced by serine (ICP8cc), a deletion mutant missing 60 residues at the C terminus (ICP8ΔC), and a construct carrying the combined mutations (ICP8ΔCcc). We demonstrate that they all show comparable affinities for synthetic (dT)14 oligonucleotides containing a single binding site, while the two C-terminal deletion mutants display a remarkable decrease in the affinity for longer (dT)35 lattices, where cooperative interactions between two adjacent molecules are expected to influence binding. Under the experimental conditions used, the cysteines 254 and 455 can induce only a minor effect on this altered behavior. The results imply that the C-terminal 60-amino-acid domain of ICP8 is required for cooperativity and permit the delineation of the roles played by certain regions and residues of ICP8 in binding affinity and cooperativity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Plasmid pE29, containing the UL29 gene, was a generous gift from N. Stow (MRC Institute of Virology, Glasgow, Scotland). Restriction enzymes and φX174 ssDNA were purchased from New England Biolabs and used without further purification. Trypsin was purchased from Sigma. Recombinant baculovirus was prepared using the BAC-TO-BAC system (Gibco/BRL). Tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease was expressed and purified in-house (G. Stier and H. van der Zandt, unpublished results). Poly(dT) oligonucleotides were synthesized by the DNA Synthesis Service at EMBL Heidelberg and purified as described below. Sep-Pack cartridges were purchased from Waters Corporation. Acrylamide-bisacrylamide (19:1) was bought from Peqlab Biotechnologie GmbH.

Cloning strategies.

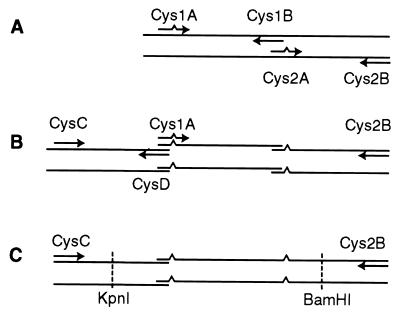

The UL29 gene from HSV-1 strain 17 (0.315 to 0.422 map coordinates) coding for ICP8 was obtained from plasmid pE29 (66) and cloned into the pFastBacHTa (Gibco BRL) baculovirus vector in two steps. The restriction fragment containing the 1.9-kbp carboxy terminus of the UL29 gene was excised directly from pE29 with KpnI and HindIII. The first 236 bp of the UL29 gene were generated by PCR amplification from the pE29 template using the primers 5′CATGCCATGGAGACAAAGCCCAAGACGGCA3′ and 3′CCCGAGCCCCCATGGCGC5′ to introduce an NcoI site at the N terminus. The full UL29 gene was then reconstituted by a three-fragment ligation into the multiple cloning site of the bacterial donor plasmid pFastBacHTa, previously linearized with NcoI and HindIII, downstream from the baculovirus-specific promoter for expression in insect cells. The resulting vector, Bac29, codes for the wild-type ICP8 with a hexahistidine tag linked to the N terminus via a TEV protease cleavage site. Removal of the tag leaves the two additional residues Gly-Ala upstream from the initial methionine of the polypeptide chain. The C-terminal deletion mutant was derived from Bac29 by substitution of the SalI-HindIII fragment with a PCR product containing a deletion of nucleotides 3409 to 3591 and generated using the primers 5′CGGCAACGGCGAGTGGTCGAC3′ and 3′GATCAGTCGGTTGACCCGTAATTCGAAGGG5′ on the Bac29 DNA template. The resulting vector, Bac29ΔC, encodes a protein 60 amino acids shorter than the wild type, termed ICP8ΔC, and thus lacking the NLS. Two site-directed mutations Cys254Ser and Cys455Ser were introduced into the UL29 gene by single-nucleotide alteration from guanine to cytosine at positions 761 and 1364, respectively. Three rounds of PCR were performed to generate the DNA fragment containing the two desired mutations as represented in Fig. 1. In the first instance, two separate fragments carrying a single mutation each were produced from the Bac29 template using the primers Cys1A (5′CCGCCGCCGTGGCACTGCGATCCCGAAACGTGGACGCCGT3′) and Cys1B (3′CGCTCGTGGACCGGTACGAC5′) or Cys2A (5′GCGAGCACCTGGCCATGCTGTCTGGGTTTTCCCCGGCGCT3′) and Cys2B (3′CGCAGTACCGGCTTGAGCTCTGG5′). The direct primers Cys1A and Cys2A are about 40 nucleotides long and contain a mismatch in the center accounting for the base substitution (underlined in the sequences above). The reverse primer Cys1B was designed to anneal 1 base downstream from the guanine 1364, complementary to Cys2A, while Cys2B annealed 80 nucleotides downstream from the BamHI restriction site. Due to the overlapping ends, it was possible to join the PCR products obtained from this first step with a second PCR round employing the external primers Cys1A and Cys2B, to generate a double-mutation fragment. In parallel, the 810-bp N-terminal frame encompassing the KpnI site was amplified from Bac29 with the primers CysC (5′CACGATTACGATATCCCAACGACCG3′) and CysD (3′GGCGGCGGCACCGTGACGCT5′), the latter of which anneals 1 base upstream from guanine 761. Again, the overlapping products were annealed by a final PCR cycle with primers CysC and Cys2B, followed by digestion with KpnI and BamHI. The recombinant plasmids Bac29cc and Bac29ΔCcc were constructed by transferring the mutagenized DNA into Bac29 or Bac29ΔC, opened with the appropriate enzymes.

FIG. 1.

Scheme of the cloning strategy used to prepare the mutagenized plasmids Bac29cc and Bac29ΔCcc. (A) First PCR amplification to introduce single-nucleotide mutations in the Cys254 and Cys455 codons. Two overlapping point-mutated fragments are generated with either primers Cys1A and Cys1B or primers Cys2A and Cys2B. (B) Second PCR round to produce a DNA duplex containing both mutations (primers Cys1A and Cys2B used). An adjacent strand containing the KpnI restriction site was also generated (primers CysC and CysD used). (C) Final PCR step with primers CysC and Cys2B to link the mutagenized fragment into a duplex containing the extreme ends the recognition sites for KpnI and BamHI. This fragment was inserted into the vectors Bac29 and Bac29ΔC (see text) to reconstitute the full gene coding for ICP8cc and ICP8ΔCcc, respectively.

The coding sequence of the N-terminal deletion mutant was inserted in pFastBacHTc, which differs from pFastBacHTa by a shift in the reading frame. The fragment between nucleotides 921 and 1687 of the UL29 gene was amplified from Bac29 by PCR with the primers N1 (5′AGGTCATGAGTGGCGGGTTCGAAC3′) and N2 (5′GGTCTCGAGTTCGGCCATGACGC3′). N1 anneals at position 921 and contains the recognition site of the BspHI restriction enzyme and an initiation codon. N2 anneals downstream the BamHI site. After partial digestion with BamHI and BspHI, the UL29 fragment from nucleotides 921 to 1687 was ligated into the polylinker of pFastBacHTc previously linearized with NcoI (isoschizomer of BspHI) and BamHI. The resulting plasmid, Bac29N, was used to derive Bac29ΔN by insertion of the UL29 fragment BamHI-HindIII excised from Bac29. Bac29ΔN codes for the last 888 residues of ICP8 as well as additional amino acids Met and Ser encoded by the primer N1 sequence.

All plasmids were verified for correct insertion or mutation by multiple cleavage with restriction endonucleases as well as by primer walking sequencing (Seqlab, Göttingen, Germany).

Preparation of recombinant baculoviruses and transfection procedures.

Recombinant baculoviruses for the four ICP8 constructs were generated according to the guidelines of the BAC-TO-BAC baculovirus expression system (Gibco/BRL), based on site-specific transposition of the whole expression cassette containing the heterologous gene from the donor pFastBac plasmids into a baculovirus shuttle vector (bacmid) propagated in Escherichia coli DH10Bac cells. Insertion of the cassette in the bacmid disrupts expression of the lacZα peptide, allowing rapid and efficient selection of the recombinant white colonies among the background blue ones. After isolation, recombinant bacmids were used to transfect Spodoptera frugiperda 9 cells to produce viral stock for the overexpression of the desired protein. Monolayer cultures of High 5 insect cells were grown to approximately 90% confluence at 28°C and infected with recombinant baculoviruses at a multiplicity of infection varying from 1 to 5. Cells were harvested 48 h postinfection by centrifugation at 123 × g for 10 min, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and frozen at −80°C.

Purification of constructs.

Pelleted High 5 cells were thawed and resuspended in a buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 100 mM NaBr, 20% glycerol, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and protease inhibitors (1 μM pepstatin A, 1 mM Pefabloc, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μM E64, 10 μM leupeptin, and 10 μM 3,4-dichlorisocoumarin). Cells were disrupted using an Ultraturrax Dounce homogenizer, and extracts were clarified by centrifugation at 150,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. To stabilize the protein, all buffers were flushed with nitrogen and supplemented with reducing agent and pepstatin A prior to use. Since no temperature dependence was observed during the purification procedure, all chromatographic steps were performed at 20°C.

The supernatant was loaded on a Q-Poros fast-flow ion-exchange column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8)–100 mM NaBr–20% glycerol–2 mM β-mercaptoethanol–1 μM pepstatin A. The column was washed with the same buffer and developed with a linear gradient of 100 to 400 mM NaBr in 4 column volumes. ICP8 constructs eluted typically at about 220 mM NaBr. Protein in gradient fractions was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm. The peak fractions were pooled and applied to a 5-ml High Trap metal chelating column (Pharmacia) loaded with NiCl2 and equilibrated with 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8)–300 mM NaBr–20% glycerol–2 mM β-mercaptoethanol–1 μM pepstatin A. After a column wash, the bound protein was eluted with an imidazole step gradient; ICP8 elutes at 100 mM imidazole. Purity of ICP8 fractions was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and the concentration was determined by 280-nm absorption readings on a UVICON 922 spectrophotometer using an extinction coefficient of 84,230 M−1 cm−1 (calculated according to Pace et al. [52]). Pure protein was collected and desalted on a Sephadex G-25 column (Pharmacia) to remove imidazole and adjust the β-mercaptoethanol concentration to 10 mM. Cleavage of the histidine tag by TEV protease was carried out at a substrate-to-protease ratio of 6:1 (wt/wt) overnight on ice and at a protein concentration of less than 1 mg/ml to prevent aggregation. To isolate the cleaved material, the digestion mixture was loaded on the High Trap chelating column a second time, and the flowthrough was retained. The protein preparation was concentrated in a stirred ultrafiltration cell (Amicon) prior to application to the last size exclusion chromatographic step. A Superdex 200 column was equilibrated with storage buffer, consisting of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 300 mM NaBr, 20% glycerol, 10 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 μM pepstatin A. The peak fraction was once again concentrated in a Centricon to approximately 5 to 10 mg/ml and stored in aliquots at −80°C. According to SDS-PAGE and Bradford colorimetric assays calibrated on ICP8 (8), the purification yielded approximately 30 mg of 95% pure protein from 20 g of pelleted cells. Prior to ssDNA binding assays, the proteins were dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–150 mM KCl–1 mM EDTA–6% Ficoll–10 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Preparation of DNA substrates for binding assays.

Purification of oligonucleotides by denaturing gel electrophoresis was performed to ensure uniformity in size and removal of nucleotide contaminants resulting from the synthesis procedure. Poly(dT) oligonucleotides 14, 20, 28 and 35 bases long were 5′ labeled with a fluorescein molecule via a phosphoramidite spacer. The oligonucleotides were dissolved in 0.9 ml of double-distilled H2O, heated at 42°C in a water bath for 20 min, and sonicated for 5 min. Loading buffer (90% formamide, 10% 10× Tris-borate-EDTA [TBE] buffer, 0.025% bromophenol blue, 0.025% xylene cyanol, 20% glycerol) was added at 1:10; then the samples were heated for 5 min at 95°C, chilled for 5 min on ice, and spun in an Eppendorf table centrifuge prior to application to a TBE denaturing gel supplemented with 8 M urea. The acrylamide-bisacrylamide (19:1) concentration was adjusted to 12% for (dT)28 and (dT)35 or to 15% for the shorter (dT)14 and (dT)20. The gel was run at 40 V/cm. The band of interest was excised and shaken overnight at 37°C in 0.5 M ammonium acetate (pH 8)–1 mM EDTA to allow diffusion of the oligonucleotide from the gel. The solution was filtered and applied to a Sep-Pack cartridge equilibrated with 0.5 M ammonium acetate (pH 8)–1 mM EDTA–2% methanol. Pure desalted oligonucleotides were eluted by gravity flow in 2 ml of 80% methanol, dried by evaporation, and stored at −20°C. Prior to use, the pellets were redissolved in binding buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 6% Ficoll), and the concentration was determined spectrophotometrically using a molar extinction coefficient of 73,000 M−1 cm−1 for the fluorescein fluorophore.

EMSA.

Binding reactions were assembled in a final volume of 40 μl and contained 0.5 to 2 μM DNA substrate in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 6% Ficoll, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and the desired concentration of ICP8 mutant. The mixtures were incubated for 30 min on ice, and complexes were resolved on 5% (30:1 acrylamide-bisacrylamide) native gels using TBE buffer (pH 8). The gels were prerun for 1 h at 2 V/cm and run at 5 V/cm at 4°C. Specimens were visualized and quantified by densitometric analysis using a phosphorimager to record the emission signal of the excited fluorescein labels.

Trypsin digestion.

About 48 μg of wild-type ICP8 was digested with 0.7 μg of trypsin in 90 μl of a binding buffer consisting of 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM MgCl2. Stock solutions of (dT)20 oligonucleotides were dissolved in the same binding buffer. To detect any DNA protection from proteolytic cleavage, the same amount of protein was incubated with a 15-fold molar excess of (dT)20 for 30 min on ice prior to digestion with trypsin. At the times indicated, 2 μg of protein was removed from the mixture, and proteolysis was terminated by boiling the sample for 5 min in loading buffer. The proteolysis observed at notional zero time reflects the finite time lag required for inactivation of the reaction. The proteolyzed products were separated on an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel and analyzed by zinc-imidazole staining (18). Variations in the rate of digestion were observed between individual experiments; however the protection pattern was consistent throughout the analysis.

Electron microscopy.

Samples of ICP8, ICP8cc, ICP8ΔC, and ICP8ΔCcc were examined for their cooperative binding to long ssDNA filaments by negative staining. Proteins were diluted with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–150 mM KCl–1 mM EDTA–20% glycerol to which φX174 ssDNA (1 mg/ml) was added and then incubated for 30 min on ice. Approximately 2 μl of the binding mixture was applied on a 400-mesh Formvar-coated and discharged-activated grid, and the excess liquid was removed. The preparation was stained with 1% uranyl acetate solution and set to dry. The grids were examined in a Philips CM20 electron microscope equipped with a charge-coupled device camera.

CD.

Circular dichroism (CD) measurements were performed in 0.1-cm thermostated quartz cuvettes in a Jasco 700 spectrometer, using 0.3 ml of each sample. Proteins were analyzed in 60 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5)–20% glycerol to provide the ionic strength required for protein stability and minimize buffer absorbance at the shorter wavelengths. CD spectra were acquired at 20 and 4°C between 250 and 205 nm (0.1-nm steps, 50-nm/min scan speed, and 1-s time constant). Forty spectra were averaged for each sample, and the spectrum of the buffer alone was subtracted. The raw ellipticity data (millidegrees) were converted to mean molar ellipticity per residue (Θres, deg · cm2 · dmol−1) and plotted using Kaleidagraph (Albeck Software). Thermal denaturation experiments were performed on the same samples from which the spectra had just been acquired. The temperature of the cell holder was increased from 4 to 80°C at 50°C/h to monitor the variation of the ellipticity at 222 nm. Data were plotted as Θres222 (deg · cm2 · dmol−1) versus temperature (degrees Celsius).

TRXF.

Total reflection X-ray fluorescence analysis (TRXF) was used to determine the presence and molar concentration of zinc in the ICP8 mutants, using as an internal reference element the sulfur of cysteines and methionines (74). Samples analyzed consisted of 20 to 30 μM ICP8 solutions dissolved in 0.2 M sodium acetate (pH 7.5) with 20% glycerol. After addition of an internal standard, 4 μl of sample solution were pipetted onto a quartz glass carrier and dried to a thin film. Measurements were performed on an EXTRA IIA TRXF spectrometer (Atomic Instruments) equipped with a Si(Li) solid state detector at the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry, University of Frankfurt.

RESULTS

Cloning the ICP8 mutants.

The goal of this study was to determine the region of ICP8 responsible for the cooperativity exhibited by the molecule in ssDNA binding. ICP8 has a marked tendency to aggregate upon oxidation of its 22 cysteines. Mapping Cys254 and Cys455 as being directly involved in contacting the nucleic acids made them good candidates for replacement by serine. Inspection of a multiple sequence alignment of ICP8 with other Herpesviridae SSBs (ClustalX [69]) showed that Cys455 is well conserved whereas Cys254 can be replaced by hydrophobic or aromatic residues. Secondary structure prediction (PredictProtein [56]) suggests that the two cysteines reside in helical regions, but they are not expected to be fully exposed and accessible to the substrate. The double-point mutant ICP8cc was cloned as described in Materials and Methods, and the mutations were verified by sequencing of the PCR fragment KpnI-BamHI, coding for the two replaced residues. Analysis of ICP8 primary structure also revealed that the C-terminal portion of the molecule contains glycine- and proline-rich motifs as well as several polar residues. It is very likely solvent accessible and unstructured in solution. The 36 carboxy residues were shown to be dispensable for binding, and it was not clear how and to what extent further deletion could affect the nucleotide affinity (24). Therefore, we decided to truncate the carboxy tail at the end of the last predicted α helix, corresponding to Gly1136, to create deletion mutant ICP8ΔC. Insertion of the double-cysteine-mutagenized KpnI-BamHI fragment into baculovirus vector Bac29ΔC coding for ICP8ΔC resulted in the third construct, ICP8ΔCcc.

A control sequencing of the wild-type UL29 gene used revealed the existence of three additional alterations in the amino acid sequence compared with the reported HSV-1 strain 17 primary structure (48), namely, K224N, A306P, and A475G. Despite the fact that some these substitutions are not conservative, all three of them occur naturally and simultaneously in HSV-1 strain KOS (22) and HSV-2 strain HG52. Since the corresponding polypeptides, in particular the HSV-1 strain KOS, are known to interact in the same way with the nucleic acids as the HSV-1 strain 17 ICP8, it is safe to conclude that they do not significantly affect the behavior of the mutants analyzed in this study.

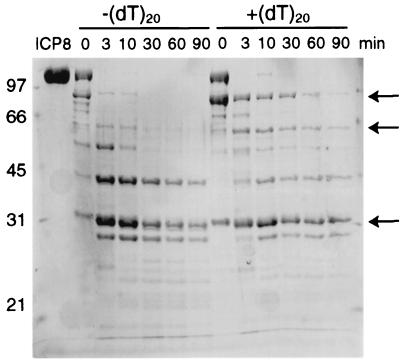

Limited proteolysis in the presence or absence of ssDNA substrate was used as a tool to map structural domains of ICP8 and to investigate the conformational changes that the protein may possibly undergo upon DNA binding. At the same time, we wished to identify possible deletions that would reduce the tendency of the protein to aggregate. The sensitivity to trypsin cleavage of the full-length ICP8 alone or in complex with (dT)20 was analyzed in time course experiments. As shown in Fig. 2, some differences in the rate of proteolysis of the free and bound protein were evident. Both in the presence and in the absence of ssDNA, ICP8 was digested in less than 3 min into two fragments of approximately 95 and 33 kDa. However, in the presence of (dT)20, the 95-kDa polypeptide was more resistant to further cleavage than the unligated species. The cleavage pattern is in agreement with previous trypsin digestion studies (72, 73) implicating the 56-kDa fragment as the smallest product containing the ssDNA binding domain. Initially we attempted to separate ICP8 tryptic digestion mixture by gel permeation chromatography on a Superdex 200 column. Under nondenaturing conditions, all of the fragments eluted together with the same profile as intact ICP8, suggesting the existence of intramolecular interactions holding together different portions of the molecule. An analogous experiment performed on an ssDNA-cellulose column (72) led to the same conclusion. The band corresponding to the smallest (33-kDa) fragment was excised from the gel and analyzed by mass spectrometry (matrix-associated laser desorption ionization peptide mass mapping, EMBL Heidelberg), which assigned it to the N-terminal domain of ICP8, between residues 1 and 253. This proved that the 95-kDa C-terminal part of ICP8 contains the ssDNA binding domain, in agreement with previous evidence (40). To further characterize the binding properties of the C-terminal fragment, the ICP8ΔN deletion mutant was designed. Trypsin specifically cleaves the peptide bond after lysine and arginine amino acids, providing only a rough estimate of the domain boundaries. The part of ICP8 sequence containing Arg253 is predicted to be α helical and is predicted to be followed by a loop region. Therefore, we decided to place the N terminus of ICP8ΔN at Gly308, where a series of α-β-structure elements is predicted to begin. Due to lack of information provided by the tryptic digestion on the C terminus of the ∼95-kDa fragment, the UL29 gene was not truncated at that end.

FIG. 2.

Digestion of full-length ICP8 in the absence [−(dT)20] and presence [+(dT)20] of ssDNA. Samples were assembled as described in Materials and Methods. Where indicated, (dT)20 was incubated with the protein prior to addition of trypsin. Each lane is labeled with the digestion time. Products were resolved by SDS-PAGE on a 10% gel and stained with zinc-imidazole. Lane ICP8 contains full-length ICP8. Positions of molecular mass markers are shown on the left in kilodaltons. The arrows indicate the position of the 95-, 56-, and 33-kDa fragments. The 95- and 56-kDa fragments are more resistant to proteolytic cleavage after incubation with the ssDNA.

ICP8cc, ICP8ΔC, and ICP8ΔCcc were expressed in baculovirus with a similar yield as the wild-type protein and purified to homogeneity with the same protocol. A twofold increase in protein solubility was observed for the two C-terminal deletion constructs. The oligomeric state of the polypeptides was assessed by size exclusion chromatography and ultracentrifugation, which demonstrated that they are monomeric in solution up to concentrations of 5 to 10 mg ml−1, in good agreement with previous sedimentation analyses (50). Dynamic light scattering experiments also confirmed that the preparations were monodisperse (data not shown). ICP8ΔN was also expressed in baculovirus with good yield but was completely insoluble under several lysis conditions, including high or extremely low ionic strength, presence of detergents or zinc salts, and increasing amounts of glycerol (data not shown). This evidence confirms the hypothesis that strong, most likely hydrophobic, interactions exist between the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of ICP8 (24), but also prevented any further investigations with the ICP8ΔN construct.

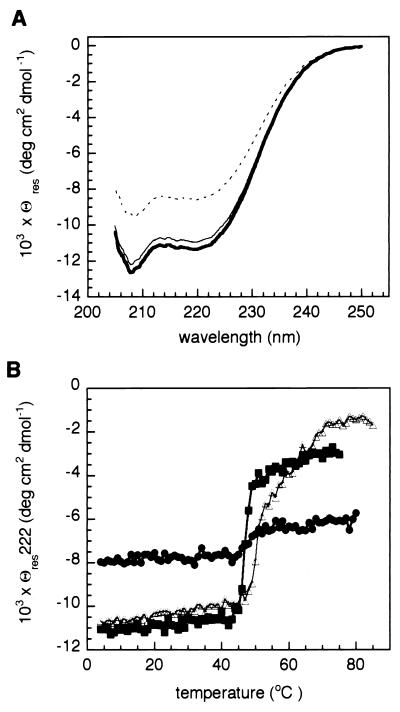

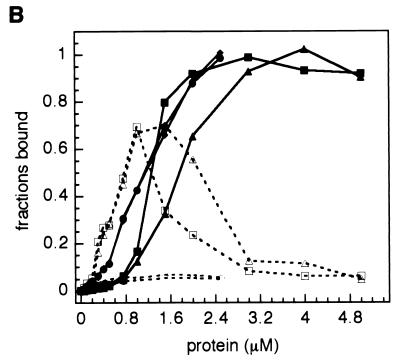

To evaluate at which level the introduced mutations affect the properties of ICP8, the structural integrity of the proteins was investigated in two ways. TRXF spectroscopy was used to assess the presence of zinc in the constructs, using the protein sulfur content as an internal reference. The molar ratios between the zinc and the molecule were determined to be 1.24 (±0.10) for ICP8, 1.19 (±0.09) for ICP8ΔC, and 0.95 (±0.12) for ICP8ΔCcc. We conclude that all the constructs contain zinc in a stoichiometry of 1:1, meaning that neither Cys254, Cys455, nor the 60-amino-acid C-terminal region belongs to the metal binding site. This does not contradict a suggestion (27) placing the metal binding site at positions 499 to 512. Far-UV CD spectroscopy provided information about the overall secondary structure of the purified proteins. Samples were dialyzed against phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) suitable for CD measurements, and preliminary dynamic light scattering measurements indicated that the protein was also monodisperse under these conditions. Nonetheless, reliable spectra could be recorded only up to 205 nm due to strong buffer absorption. The spectra acquired for ICP8, ICP8ΔC, and ICP8ΔCcc are displayed in Fig. 3A. As recently reported by Spatz et al. (64), the profiles are dominated by the α-helical component with the typical double minima in ellipticity at 208 and 222 nm. Spectra corresponding to the deletion mutants and the wild-type ICP8 share the same features, and only a slight increase in the Θres for the mutants, possibly related to a more compact fold, is detectable. The variation of Θres with temperature is related to the thermodynamic parameters describing the stability of the proteins and their domains (51); therefore, the change in ellipticity at 222 nm was analyzed as a function of increasing temperature (Fig. 3B). For ICP8ΔC and ICP8ΔCcc, a sharp transition is observed between the native and the denatured state at temperatures of 45 and 50°C, respectively, and it is indicative of a rapid and cooperative unfolding process. In contrast, the conformational change of the wild-type protein was barely detectable at this wavelength, and only when the same measurements were performed monitoring the ellipticity at 208 nm (data not shown) was it possible to follow the slower denaturation beginning at about 45°C. The irreversibility of the transition does not allow a precise quantification of the associated thermodynamic parameters. Interpretation of the difference in CD spectra in terms of the retention or disappearance of a particular kind of secondary structure element is not easy from inspection of the denaturation curves, especially for such a large molecule. Both α and β structures contribute to the ellipticity at 222 nm, while at 208 nm the spectra are dominated by the α-helical component. For full-length ICP8, the evidence for a faster decrease in ellipticity at 208 nm than at 222 nm could be interpreted as the existence of a β-sheet core that is more stable to thermal denaturation. What is clear is that removal of the 60-amino-acid C-terminal region affects the pathway between a folded and a fully denatured state. These data imply that the C terminus of ICP8 plays a role in protein stability. This is only mildly modulated by the two-cysteine substitution, which shifts the transition temperature toward lower values.

FIG. 3.

CD spectroscopy on ICP8 and its mutants. (A) CD spectra between 250 and 205 nm were acquired at 4°C from stock of each ICP8 mutant. After dialysis in 60 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), concentrations of the various samples were determined by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm and using an extinction coefficient of 84,230 M−1 cm−1. Concentrations were adjusted by dilution to 2 μM. Spectra are plotted in mean Θres units. Symbols: ----, wild-type ICP8; ———, ICP8ΔC; ■■■, ICP8ΔCcc. No marked difference in the shape of the curves is evident. (B) Thermal denaturation profiles. The samples used for panel A were heated from 4 to 80°C, monitoring the variation of ellipticity at 222 nm. Symbols: ●, wild-type ICP8; ▵, ICP8ΔC; ■, ICP8ΔCcc.

Single-stranded binding ability of ICP8 mutants.

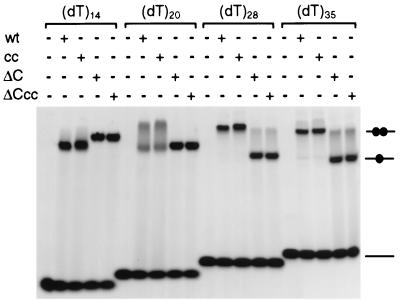

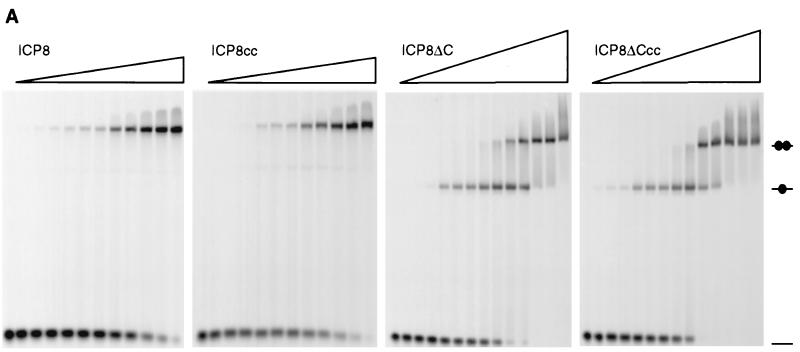

The topology of SSBs binding to the nucleic acids can be described by two parameters: the occluded binding site and the interaction site (14). The former is the length of DNA stretch covered by the bound protein, and the latter is the average number of nucleotides in direct contact with the protein. It is conceivable, and well documented in the case of other SSBs, that analysis of the protein-DNA interaction with different techniques or under different conditions may provide information about either one or the other of the two parameters. Nuclease protection experiments and electron microscopy studies with long ssDNA filaments allow evaluation of the occluded site, while dialysis, EMSA, or fluorescence quenching can be used to define the interaction site. In the present work, EMSAs were carried out with poly(dT)s of increasing length in order to characterize the specific affinity of the single molecule to the DNA as well as the effects of cooperative interactions. The oligonucleotides were 5′ labeled with a fluorescein molecule, and complex formation was visualized by monitoring the fluorescence signal at 520 nm. In preliminary experiments it became clear that it was possible to achieve binding of ICP8 to oligonucleotides as short as a dodecamer but only with low reproducibility, in agreement with other work (59). To first delineate the general binding capabilities of ICP8, ICP8cc, ICP8ΔC, and ICP8ΔCcc, we compared the (dT)14, (dT)20, (dT)28, and (dT)35 (Fig. 4). Under the conditions used, the four proteins bind tightly irrespective of length with a pattern defined by the presence or absence of the C-terminal region. The full-length constructs ICP8 and ICP8cc form two singly and doubly ligated complexes when incubated with (dT)20, and their binding stoichiometry becomes 2:1 with (dT)28. The smearing observed in the shifts in the ICP8-(dT)20 lanes are indicative of the cooperative character of the protein-nucleic acid interaction which results in nonrandom distributions of the molecules on the substrate, as first pointed out by Lohman et al. (42). In contrast, the C-terminal deletion mutants ICP8ΔC and ICP8ΔCcc migrate as a single band in the presence of (dT)20, and only a faint band for doubly ligated species appears in the presence of (dT)28 and (dT)35. No significant difference can be detected in the behavior of the double-cysteine mutants compared with their unaltered counterparts. The clear conclusion is that removal of the C-terminal region does not affect the intrinsic ssDNA binding ability of ICP8 to oligonucleotides but that it does strongly reduce the propensity to promote the intermolecular interactions leading to cooperative binding of the wild-type protein on lattices consisting of two or more binding sites. Furthermore, inspection of the stoichiometries of binding of the full-length ICP8 suggests that the minimal interaction site is 10 nucleotides, since two molecules can be loaded on (dT)20, while the occluded site is 13 to 14 nucleotides, explaining why no 1:3 complex can be resolved in presence of (dT)35.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of the binding of ICP8 constructs on deoxythymidine oligonucleotides of increasing lengths. Reaction mixtures contained 30 pmol of purified protein ICP8, ICP8cc, ICP8ΔC, or ICP8ΔCcc and 40 pmol of a terminally fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotide 14, 20, 28, or 35 nucleotides long in 20-μl volume. After 30 min of incubation on ice, each sample was fractionated on a nondenaturing acrylamide-bisacrylamide 5% gel according to the loading pattern indicated at the top. Abbreviations: wt, wild-type ICP8; cc, ICP8cc; ΔC, ICP8ΔC; ΔCcc, ICP8ΔCcc. Complexes representing the singly and doubly ligated species are shown schematically on the right.

Titration with (dT)14.

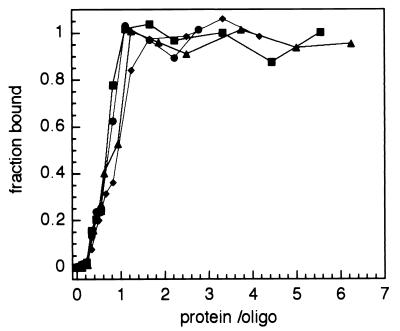

To gain further insight into the different mutant phenotypes, we carried out a series of titrations in which the shortest oligonucleotide, (dT)14, was incubated with increasing concentrations of pure protein and the resulting complexes were analyzed on agarose gels. Due to the poor solubility of the full-length constructs, titrations with ICP8 and ICP8cc spanned only about half of the concentration range of the C-terminal deletion mutants. The binding increases rapidly over the experimental concentration range, and full occupancy is achieved for ICP8, ICP8cc, ICP8ΔC, and ICP8ΔCcc at similar protein-to-oligonucleotide ratios. Quantitative data were obtained by densitometric analysis of the fluorescence signal of the fluorescein over the entire range of the transition. Representative curves from those data are plotted as a function of the total protein concentration in Fig. 5.

FIG. 5.

EMSA titration of the fluorescein-labeled (dT)14 with different ICP8 constructs. Reaction mixtures containing a fixed amount of oligonucleotide (dT)14 (∼1 μM) and either ICP8, ICP8cc, ICP8ΔC, or ICP8ΔCcc are as described in Materials and Methods. For ICP8 and ICP8cc, 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.75, 0.1, 1.5, 2, and 2.5 μM protein were used. For the truncated constructs ICP8ΔC and ICP8ΔCcc, 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, and 5.0 μM protein were used. Complexes were resolved on a native acrylamide-bisacrylamide gel, and densitometric quantification of the bands was done by analysis of the fluorescence signal of the fluorescein moiety attached to the oligonucleotides. The fraction of the bound DNA was calculated at each protein concentration by subtraction of the background and normalization to the fluorescence signal at saturation. Fractions are plotted versus the molar ratio of protein to oligonucleotide. Symbols: ●, wild-type ICP8; ⧫, ICP8cc; ▴, ICP8ΔC; ■, ICP8ΔCcc. Under the conditions used, all mutants bind stoichiometrically to the ssDNA and saturation is reached at a molar ratio of ∼1:1.

The fluorescence increases almost linearly with the protein concentration until a plateau of full occupancy is reached, indicative of a stoichiometric binding regimen (i.e., virtually all protein added is bound). This is not surprising since the binding mixtures contained 150 mM KCl and 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), close to the reported optimal binding conditions (61). Normally experiments performed in such conditions but on longer lattices are useful for establishing the occlusion site size, which corresponds to the molar ratio of nucleotide-to-protein at saturation. In this case, the oligonucleotide allows only singly ligated complexes, and therefore the occurrence of the infection point of the titration at a 1:1 protein-to-(dT)14 ratio means that all of the protein is active. Additional direct evidence was used to determine the activity of the preparations. The low sensitivity of the fluorescence method compared to the radioactive 32P labeling commonly used in gel retardation assays requires loading of micrograms of protein per slot. Therefore, a direct Coomassie blue staining of the gel after fluorescence scanning can be performed with standard protocols. On the other hand, the stability of the fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotide is not subject to decay and permits the rather precise calibration of the oligonucleotide concentration by a separate titration subsequently used as an external standard for all experiments. Coomassie blue staining revealed the presence of protein migrating slower than the complex in the lanes where the amount protein exceeds the oligonucleotide and that protein traces are left in the slots only at the highest concentrations used (data not shown).

Only a lower limit for the binding constant can be deduced from the component concentrations because binding under these stoichiometric conditions is very tight (31). The reaction mixtures contained about 1 μM polynucleotide; thus, the experiments establish that the affinity of ICP8 for (dT)14 is higher than 106 M−1. Any variations in Ka above this threshold cannot be detected in these experiments. The affinity as intended in this context is the macroscopic or apparent binding constant. The free energy of nonspecific binding of a protein to an oligonucleotide has two contributions, an intrinsic binding free energy due to the interaction and an entropic contribution arising from the possible arrangements of the protein on the oligomeric lattice (14). These considerations predict a linear dependence of the observed binding constant on the oligomer length. For the experiments reported here, assuming an interaction site for ICP8 of 12 to 13 nucleotides and that binding to the lattice is polar, the detected affinity should be larger than the intrinsic binding constant by a factor of 2 to 3. Such a small difference would not be detectable for the reason specified above.

Although variations in Ka between mutants of a few orders of magnitude are possible (because above ∼106 M−1 they would not be detectable), these assays show that none of the mutations drastically decrease the intrinsic affinity of ICP8 for short poly(dT)s and thus neither cysteines 254 and 455 nor the C-terminal 60 residues are involved in contacting the DNA in the 1:1 complex.

Cooperative binding to (dT)35.

Cooperativity analysis was accomplished by (dT)35 titration over the same concentration range used for (dT)14. We observed two bands with altered mobility corresponding to binding of one (1:1) or two (2:1) proteins (Fig. 6A). The difference in affinity among the proteins is immediately evident. Full-length ICP8 and ICP8cc are readily capable of forming saturated doubly occupied complexes at relatively low protein concentrations, while the truncated forms ICP8ΔC and ICP8ΔCcc do not form the doubly ligated species except at the highest concentrations used. Once again, the double-cysteine mutants and their unmodified cognates display similar behavior. A graph of the fraction of the molecular species present in the native gel as a function of increasing total protein concentration is shown in Fig. 6B. As suggested by visual inspection of the scanned gels, the profiles representing the 2:1 species in the case of ICP8 and ICP8cc rise to saturation with the same steep gradient, and the 1:1 complex is barely detectable. Also, densitometric analysis and Coomassie blue staining of the gels could not discriminate between the double-point mutant and the wild-type protein. In contrast, comparing ICP8ΔC and ICP8ΔCcc, we see that first one molecule is loaded onto the DNA lattice, and the second binds when the protein is much in excess over the substrate. Surprisingly, the saturation is delayed for ICP8ΔC relative to ICP8ΔCcc, indicating a possible modulation exerted by the two cysteines on the intermolecular interaction stabilizing the two contiguous proteins in the 2:1 complexes. The smearing of the rightmost lanes reflects the tendency to form multimers during electrophoresis, and it is responsible for the dip in bound protein observed at the highest protein concentrations.

FIG. 6.

EMSA titration of fluorescein-labeled (dT)35 with ICP8 mutants. (A) Reaction mixtures containing a fixed amount of oligonucleotide (dT)35 (∼0.75 μM) and either ICP8, ICP8cc, ICP8ΔC, or ICP8ΔCcc were assembled as described in the text. Protein concentration ranges are the same as those used in the (dT)14 titrations (Fig. 5). Complexes were resolved on a native acrylamide-bisacrylamide gel. Positions of the free probe and the 1:1 and 2:1 complexes (from bottom to top) are indicated at the right. Significant differences in cooperativity of the binding of the full-length ICP8 and ICP8cc and truncated ICP8ΔC and ICP8ΔCcc are visible. (B) Quantification of the bands was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 5. Fractions are plotted as a function of total protein concentration. Full symbols, 2:1 complexes; open symbols, 1:1 complexes; ●, wild-type ICP8; ⧫, ICP8cc; ▴, ICP8ΔC; ■, ICP8ΔCcc. In the case of ICP8ΔC and ICP8ΔCcc, the smearing of the external bands correlate with the decrease of signal at the points of the profiles corresponding to the highest protein concentrations.

The parameter describing the cooperativity, ω, is defined as the unitless equilibrium constant for the process of transferring two isolated DNA-bound molecules to make them contiguous. The finite length of the lattices considered in these experiments intrinsically lowers the apparent ω because the second binding reaction can take place only when the first molecule is bound at a limited number of positions, namely, at the ends. Therefore for entropic reasons, the binding of the second molecule is anticooperative. Thus, two opposing trends will contribute to the final binding of adjacent sites with these shortish substrates, and the value of the cooperativity parameter would be estimated more straightforwardly from binding to longer lattices where the end effects become negligible. Despite the inability to reliably estimate ω, analysis of the binding affinity for (dT)35 provides compelling evidence that removal of the C-terminal portion of the protein disrupts the cooperative nature of the interactions between ICP8 and the nucleic acids. More intriguing is the role played by Cys254 and Cys455 in the cooperativity. The two cysteines do not affect the binding of the full-length constructs but enhance the affinity for ssDNA of the C-terminal deletion mutants.

Binding mixtures containing an equimolar ratio of one of the full-length proteins (ICP8 or ICP8cc) and one of the truncated proteins (ICP8ΔC or ICP8ΔCcc) were subjected to electrophoresis to test the feasibility of rescuing the binding deficiency of the C-terminal deletion mutants. None of the mixtures could bind to (dT)35 as efficiently as the full-length ICP8 (data not shown). This could imply that reciprocal interactions take place between the two molecules sitting on the same strand.

Electron microscopy of ICP8 and ICP8cc.

Having established that Cys254 and Cys455 are not effectors of the cooperativity exhibited by ICP8 and ICP8cc on oligonucleotides, it was important to rule out the possibility that they could affect the covering of long single-stranded filaments. ICP8 and its double-point mutant were incubated in the usual binding buffer with φX174 ssDNA and examined by electron microscopy after negative staining. In agreement with earlier studies, wild-type ICP8 fully coats the DNA strand in regular condensed coils to full saturation. The same is observed for ICP8cc, suggesting that on long lattices the cooperative behavior of ICP8 is not influenced by the double-cysteine mutations. Identical experiments incubating the DNA with either of the C-terminal deletion mutants did not show any such structures; since we would not expect to observe naked ssDNA, the implication is that these mutants do not cover ssDNA in the same regular fashion.

DISCUSSION

The 95-kDa C-terminal fragment of ICP8 becomes more resistant to tryptic digestion after binding to (dT)20. This can be caused by the bound ssDNA sterically blocking the access of the protease or by a DNA-induced conformational change in ICP8. Since we have shown that incubation of ICP8 with a 20-nucleotide-long oligonucleotide results in a mixed population of singly and doubly ligated complexes, it could also be that steric hindrance at the interface between two molecules attached to the DNA strand influences the sensitivity to trypsin. The ICP8ΔN mutant was totally insoluble, suggesting that the C-terminal and N-terminal regions of ICP8 have a structurally well-defined interface, in agreement with previous evidence (24, 39, 72).

The double-cysteine mutant, in which Cys254 and Cys455, originally suggested as effectors of cooperative binding (15), are replaced by serines, still contains zinc, showing that the zinc binding site does not involve these cysteines. The C-terminal deletion mutants also contain zinc, in agreement with the hypothesis that C-terminal cysteine cluster is also not involved.

Far-UV CD profiles show no change in the ICP8 primary structure, in agreement with the predicted location of the cysteines in a region devoid of α or β secondary structure as well as with the anticipated lack of secondary structure for the last 60 residues. We believe therefore that the overall fold is the same and that the slight difference in the CD curves between the C-terminal deletion mutants and the full-length protein can be explained as an increased compactness resulting from the C-terminal tail truncation. It might be that the most important determinant of the crystallizability of ICP8ΔC relative to ICP8 (46) is due to this compactness rather than the presence of less oligomeric protein. The observed difference in thermal stability between the full-length protein and ΔC mutants could be due to flexibility of the constitutive subunits of the full-length protein that facilitate intra- or intermolecular interactions which prevent fast cooperative unfolding.

Comparison of the affinities for several poly(dT) oligonucleotides of different lengths suggest the interaction site to be 10 nucleotides and the occluded site to be 13 or 14 nucleotides. This explains the existence of a doubly ligated moiety upon ICP8 incubation with (dT)20, where the molecules can arrange at the extreme ends of the lattice, possibly protruding out of the strand to minimize steric hindrance, as well as for the absence of a triply ligated species on (dT)28 and (dT)35. A third band with stoichiometry of 3:1 is not observed and is most unlikely to comigrate with the 2:1 complex. Moreover, given the high cooperativity exhibited by the full-length ICP8, it would also be extremely improbable that a 3:1 complex with (dT)28 or (dT)35 would form only at protein-to-DNA ratios higher than the ones we could achieve. An alternative explanation could be that for higher stoichiometries, there is a conformational change, but this would imply a looser, rather than a more compact, binding, which seems unlikely.

Our results are consistent with previous work in which ICP8 has been shown to bind to d(pCpT)5 (59), although with a lower affinity than determined from our titration with (dT)14 and where estimates of the occluded site by nuclease protection suggested a size of 14 nucleotides (28). In EMSAs the migration of the complexes is defined by their mass, charge, and shape. Inspection of the deleted C-terminal portion indicates that the net charge of this stretch of 60 residues is −6, which might account for the higher mobility of the ICP8-(dT)14 complexes relative to the C-terminal deletion complexes. The current lack of structural information, however, does not allow us to exclude the possibility that the full-length proteins can assembly on the DNA in a more compact way.

Analysis of ICP8 binding properties by titration with (dT)14 revealed that the mutants bind with equal strength, indicating that the mutated elements are not important in the simple bimolecular reaction forming a 1:1 complex. EMSAs using fluorescein-modified oligonucleotides offer the advantage of substrate stability but have the intrinsic drawbacks of possible specific interactions between the protein and the label as well as, more seriously, a lower sensitivity. For the latter reason, the experimental conditions are in the stoichiometric binding regimen, and consequently only a rough quantification of the binding parameters can be given. Therefore we can only put a lower limit of 106 M−1 on Ka. This result is in disagreement with the weaker affinity for a 10-mer mentioned above, suggesting that secondary interactions may strengthen the binding of (dT)14 to the protein in the isolated binding mode. The value agrees with the association constant calculated for binding to (dT)25 of about 106 M−1 (15). Under the equilibrium binding conditions reported by Dudas and Ruyechan (15), it seems that the stoichiometry of binding is different from that reported here, since only a singly ligated species was detected on a 25-nucleotide-long oligonucleotide. It is possible that the binding regimen influences the affinity, but more detailed investigations are required to clarify this issue. The evidence that neither the C-terminal region, Cys254, nor Cys455 is involved in contacting the DNA is consistent with previous work.

We show that the C-terminal portion of ICP8 is essential for the cooperative binding to (dT)35. Both ICP8ΔC and ICP8ΔCcc display a binding pattern characteristic of multiple independent sites, in striking contrast with the highly cooperative behavior of the full-length ICP8 and ICP8cc. Cys254 and Cys455 finely tune the binding of the C-terminally truncated proteins in an anticooperative way. It could well be that an equivalent (minor) effect for the wild-type protein is obscured by the strong cooperativity. Two truncated forms of ICP8 were subjects of early studies (24, 61). A 36-amino-acid C-terminal deletion and a 167-amino-acid C-terminal deletion (with PALD added) showed 98 and 46% binding ability on an ssDNA column (24). If the effect of the additional four residues can be ignored, the observed difference can be explained by assuming that the effectors of cooperativity lie between residues 1029 and 1160. We have reduced the region to between residues 1136 and 1160. This contains four phenylalanines, two of which belong to a well-conserved F(N/D)F motif, as well as a cluster of five negatively charged aspartic and glutamic acid residues. The presence of such an high number of negatively charged residues in the composition of this stretch of amino acids seems to exclude the possibility of a direct interaction between these amino acids and the ssDNA. Different molecular mechanisms can account for the cooperativity of SSB proteins. In some cases, intermolecular interactions between nearest neighbors are involved, as in the case of T4 gene 32 protein or the adenovirus DBP (10, 70), and this introduces a polarity to the protein chain. In some others, the interactions forming the protein chain are of two types, as is the case for the filamentous phage gene V protein, in which dimers contact two separate DNA strands and where polarity is therefore unimportant. A third model can be conceived in which the bound molecule imposes a specific conformation on the DNA strand that facilitates the binding of the next molecule. The arrangement of the ICP8 molecules in the necklace-beaded morphology revealed by electron micrographs, shown here or in previous studies (44), would favor a polar nearest-neighbor interaction model.

Interestingly the construct of ICP8 which lacks residues 1083 to 1166, and therefore contains the NLS, possesses a dominant mutant phenotype interfering with viral DNA replication and inhibiting late gene expression of wild-type virus (62). This indicates that the C-terminal portion of the protein is important for more than one function, although it is not clear whether inhibition of late gene expression would require cooperative oligonucleotide binding.

Comparison with the other SSBs might be helpful in gaining further insight into the structural implications of the role that we assign to the C-terminal region of ICP8. Despite the difference in structural organization of the protein-DNA assembly, probably reflecting the different roles that SSBs play in the DNA metabolism of the specific host systems, a common ssDNA binding fold, called the oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide binding fold (49, 67), is found in all (except the adenovirus DBP) structurally characterized members of this family.

An overview of the molecular events resulting in cooperativity is instructive. Anchoring of the N-terminal portion of one molecule to the adjacent one on the DNA strand was reported for the T4 gene 32 protein (10). Hooking of the 17-residue C-terminal part of the adenovirus DBP to the nearest neighbor on the protein chain, around which the ssDNA is presumably wrapped, has been shown by crystallography (70). Although cooperativity for the E. coli SSB in the diverse modes of binding (41) is complex, the homologous human mitochondrial SSB, lacking a 60-residue C-terminal portion, binds ssDNA with much reduced cooperativity (13). Again the implication is that the C terminus is involved in the molecular mechanism of cooperativity. For the eukaryotic heterotrimeric replication protein A, the cooperativity, although low relative to those of the previously mentioned SSBs, is thought to reside in the C-terminal part of the 70-kDa subunit (reviewed in reference 75). The gene V protein from several filamentous phages (M13, fd, and f1) differs from these other SSBs in that it is not involved in replication but rather blocks replication and aids packaging of the ssDNA. It is known to bind as a dimer to two ssDNA filaments of opposite direction, and the high cooperativity derives both from specific hydrophobic interactions at the dimer interface (20) and from a flexible C-terminal domain (6). In this scenario, it is attractive to speculate that the use of a flexible arm to contact an adjacent molecule on the same strand, by charge or shape complementarity, is the prevailing structural mechanism accounting for the cooperativity. From a topological point of view, this seems to be more convenient for the formation of a linear array of protein molecules coating the ssDNA filament than an extensive intermolecular interface, which would not allow sufficient conformational flexibility in covering the DNA.

We have shown that for ICP8 the C-terminal tail is also the main effector of cooperativity, although it is still difficult to envisage the geometry of the interaction. The absence of quantitative data makes it inappropriate to discuss the detailed role of Cys254 and Cys455, although our results could support the hypothesis of a synergistic effect between the C-terminal arm and the two residues. In general, studies to unravel the topological aspects of the cooperativity have been hampered by the inherent and necessary propensity of SSBs to aggregate, and further evidence is needed to support the proposed mechanism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grant 50WB98370 from the Deutsches Zentrum für Luft und Raumfahrt (DLR).

We thank Eleni Mumtsidu and Andrea Urbani for help and suggestions, Martina Mertens for the TRXF measurements, and Marek Cyrklaff for help with electron microscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blackwell L J, Borowiec J A. Human replication protein A binds single-stranded DNA in two distinct complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3993–4001. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackwell L J, Borowiec J A, Mastrangelo I A. Single-stranded-DNA binding alters human replication protein A structure and facilitates interaction with DNA-dependent protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4798–4807. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boehmer P E. The herpes simplex virus type-1 single-stranded DNA-binding protein, ICP8, increases the processivity of the UL9 protein DNA helicase. J Biol Chem. 1889;273:2676–2683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boehmer P E, Lehman I R. Herpes simplex virus DNA replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:347–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boehmer P E, Lehman I R. Herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP8: helix-destabilizing properties. J Virol. 1993;67:711–715. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.711-715.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogdarina I, Fox D G, Kneale G G. Equilibrium and kinetic binding analysis of the N-terminal domain of the Pf1 gene 5 protein and its interaction with single-stranded DNA. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:443–452. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bortner C, Hernandez T R, Lehman I R, Griffith J. Herpes simplex virus 1 single-strand DNA-binding protein (ICP8) will promote homologous pairing and strand transfer. J Mol Biol. 1993;231:241–250. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bujalowski W, Lohman T M. Limited co-operativity in protein-nucleic acid interactions. A thermodynamic model for the interactions of Escherichia coli single strand binding protein with single-stranded nucleic acids in the “beaded”, (SSB)65 mode. J Mol Biol. 1987;195:897–907. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90493-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casas-Finet J R, Karpel R L. Bacteriophage T4 gene 32 protein: modulation of protein-nucleic acid and protein-protein association by structural domains. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9735–9744. doi: 10.1021/bi00088a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chase J W, Williams K R. Single-stranded DNA binding proteins required for DNA replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:103–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.000535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y M, Knipe D M. A dominant mutant form of the herpes simplex virus ICP8 protein decreases viral late gene transcription. Virology. 1996;221:281–290. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curth U, Urbanke C, Greipel J, Gerberding H, Tiranti V, Zeviani M. Single-stranded-DNA-binding proteins from human mitochondria and Escherichia coli have analogous physicochemical properties. Eur J Biochem. 1994;221:435–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Draper D E, von Hippel P H. Nucleic acid binding properties of Escherichia coli ribosomal protein S1. J Mol Biol. 1978;122:339–359. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudas K C, Ruyechan W T. Identification of the region of the herpes simplex virus single-stranded DNA-binding protein involved in cooperative binding. J Virol. 1998;72:257–265. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.257-265.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dutch R E, Lehman I R. Renaturation of complementary DNA strands by herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP8. J Virol. 1993;67:6945–6949. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.6945-6949.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falkenberg M, Elias P, Lehman I R. The herpes simplex virus type 1 helicase-primase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32154–32157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandez-Patron C, Castellanos-Serra L, Rodriguez P. Reverse staining of sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels by imidazole-zinc salts: sensitive detection of unmodified proteins. BioTechniques. 1992;12:564–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrari M E, Fang J, Lohman T M. A mutation in E. coli SSB protein (W54S) alters intra-tetramer negative cooperativity and intertetramer positive cooperativity for single-stranded DNA binding. Biophys Chem. 1997;64:235–251. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(96)02223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folmer R H A, Nilges M, Papavoine C H M, Harmsen B J M, Konings R N H, Hilbers C W. Refined structure, DNA binding studies, and dynamics of the bacteriophage Pf3 encoded single-stranded DNA binding protein. Biochemistry. 1997;36:9120–9135. doi: 10.1021/bi970251t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gac N T L, Villani G, Hoffmann J S, Boehmer P E. The UL8 subunit of the herpes simplex virus type-1 DNA helicase-primase optimizes utilization of DNA templates covered by the homologous single-strand DNA-binding protein ICP8. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21645–21651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao M, Bouchey J, Curtin K, Knipe D M. Genetic identification of a portion of the herpes simplex virus ICP8 protein required for DNA-binding. Virology. 1988;163:319–329. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao M, Knipe D M. Distal protein sequences can affect the function of a nuclear localization signal. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1330–1339. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao M, Knipe D M. Genetic evidence for multiple nuclear functions of the herpes simplex virus ICP8 DNA-binding protein. J Virol. 1989;63:5258–5267. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.5258-5267.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao M, Knipe D M. Intragenic complementation of herpes simplex virus ICP8 DNA-binding protein mutants. J Virol. 1993;67:876–885. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.876-885.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao M, Knipe D M. Potential role for herpes simplex virus ICP8 DNA replication protein in stimulation of late gene expression. J Virol. 1991;65:2666–2675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2666-2675.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupte S S, Olson J W, Ruyechan W T. The major herpes simplex virus type-1 DNA-binding protein is a zinc metalloprotein. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11413–11416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gustafsson C M, Falkenberg M, Simonsson S, Valadi H, Elias P. The DNA ligands influence the interactions between the herpes simplex virus 1 origin binding protein and the single strand DNA-binding protein, ICP-8. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19028–19034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.19028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernandez T R, Lehman I R. Functional interaction between the herpes simplex-1 DNA polymerase and UL42 protein. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11227–11232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim C, Paulus B F, Wold M S. Interactions of human replication protein A with oligonucleotides. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14197–14206. doi: 10.1021/bi00251a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim C, Snyder R O, Wold M S. Binding properties of replication protein A from human and yeast cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3050–3059. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.7.3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinebuchi T, Shindo H, Nagai H, Shimamoto N, Shimizu M. Functional domains of Escherichia coli single-stranded DNA binding protein as assessed by analyses of the deletion mutants. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6732–6738. doi: 10.1021/bi961647s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kowalczykowski S C, Lonberg N, Newport J W, von Hippel P. Interactions of bacteriophage T4-coded gene 32 protein with nucleic acids. J Mol Biol. 1981;145:75–104. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuil M E. Complex formation between adenovirus DNA-binding protein and single-stranded poly(rA). Cooperativity and salt dependence. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9795–9800. doi: 10.1021/bi00451a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee C K, Knipe D M. An immunoassay for the study of DNA-binding activities of herpes simplex virus protein ICP8. J Virol. 1985;54:731–738. doi: 10.1128/jvi.54.3.731-738.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S S, Lehman I R. Unwinding of the box I element of a herpes simplex virus type 1 origin by a complex of the viral origin binding protein, single-strand DNA binding protein, and single-stranded DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2838–2842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee S S K, Lehman I R. The interaction of herpes simplex type 1 virus origin-binding protein (UL9 protein) with box I, the high affinity element of the viral origin of DNA replication. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18613–18617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leinbach S S, Heath L S. A carboxyl-terminal peptide of the DNA-binding protein ICP8 of herpes simplex virus contains a single-stranded DNA-binding site. Virology. 1988;166:10–16. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leinbach S S, Heath L S. Characterization of the single-stranded DNA-binding domain of the herpes simplex virus protein ICP8. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1008:281–286. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(89)90017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liptak L M, Uprichard S L, Knipe D M. Functional order of assembly of herpes simplex virus DNA replication proteins into prereplicative site structures. J Virol. 1996;70:1759–1767. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1759-1767.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lohman T M, Ferrari M E. Escherichia coli single-stranded DNA-binding protein: multiple DNA-binding modes and cooperativities. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:527–570. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lohman T M, Overman L B, Datta S. Salt-dependent changes in the DNA binding co-operativity of Escherichia coli single strand binding protein. J Mol Biol. 1986;187:603–615. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lukonis C J, Weller S K. Formation of herpes simplex virus type 1 replication compartments by transfection: requirements and localization to nuclear domain 10. J Virol. 1997;71:2390–2399. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2390-2399.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Makhov A M, Boehmer P E, Lehman I R, Griffith J D. The herpes simplex virus type 1 origin-binding protein carries out origin specific DNA unwinding and forms stem-loop structures. EMBO J. 1996;15:1742–1750. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Makhov A M, Boehmer P E, Lehman I R, Griffith J D. Visualization of the unwinding of long DNA chains by the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL9 protein and ICP8. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:789–799. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mapelli M, Tucker P A. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic studies on the herpes simplex virus 1 single-stranded DNA binding protein. J Struct Biol. 1999;128:219–222. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maul G G, Ishov A M, Everett R D. Nuclear domain 10 as preexisting potential replication start sites of herpes simplex virus type-1. Virology. 1996;217:67–75. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGeoch D J, Dalrymple M A, Davison A J, Dolan A, Frame M C, McNab D, Perry L J, Scott J E, Taylor P. The complete DNA sequence of the long unique region in the genome of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:1531–1574. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-7-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murzin A G. OB (oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide binding)-fold: common structural and functional solution for non-homologous sequences. EMBO J. 1993;12:861–867. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O'Donnell M E, Elias P, Funnell B E, Lehman I R. Interaction between the DNA polymerase and single-stranded DNA-binding protein (infected cell protein 8) of herpes simplex virus 1. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4260–4266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pace C N, Scholtz M. Measuring the conformational stability of proteins. In: Creighton T E, editor. Protein structure. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1997. pp. 299–321. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pace C N, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Philipova D, Mullen J R, Maniar H S, Lu J, Gu C, Brill S J. A hierarchy of SSB protomers in replication protein A. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2222–2233. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.17.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prasad B V, Chiu W. Sequence comparison of single-stranded DNA binding proteins and its structural implications. J Mol Biol. 1987;193:579–584. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quinlan M P, Chen L B, Knipe D M. The intranuclear location of a herpes simplex virus DNA-binding protein is determined by the status of viral DNA replication. Cell. 1984;36:857–868. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rost B. PHD: predicting one-dimensional protein structure by profile based neural networks. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:525–539. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rochester S C, Traktman P. Characterization of the single-stranded DNA binding protein encoded by the vaccinia virus I3 gene. J Virol. 1998;72:2917–2926. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2917-2926.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruyechan W. The major herpes simplex virus DNA-binding protein holds single-stranded DNA in an extended configuration. J Virol. 1983;46:661–666. doi: 10.1128/jvi.46.2.661-666.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ruyechan W T. N-Ethylmaleimide inhibition of the DNA-binding activity of the herpes simplex virus type 1 major DNA-binding protein. J Virol. 1988;62:810–817. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.3.810-817.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruyechan W T, Olson J W. Surface lysine and tyrosine residues are required for interaction of the major herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA-binding protein with single-stranded DNA. J Virol. 1992;66:6273–6279. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6273-6279.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruyechan W T, Weir A C. Interaction with nucleic acids and stimulation of the viral DNA polymerase by the herpes simplex virus type 1 major DNA-binding protein. J Virol. 1984;52:727–733. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.3.727-733.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shelton L S, Albright A G, Ruyechan W T, Jenkins F J. Retention of the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) UL37 protein on single-stranded DNA columns requires the HSV-1 ICP8 protein. J Virol. 1994;68:521–525. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.521-525.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Skaliter R, Lehman I R. Rolling circle DNA replication in vitro by a complex of herpes simplex virus type 1-encoded enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10665–10669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spatz M, Ali S A, Auer M, Graf C, Eibl M M, Steinkasserer A. Circular dichroism analysis of insect cell expressed herpes simplex virus type 1 single-stranded DNA-binding protein ICP8. Protein Expr Purif. 1999;16:60–66. doi: 10.1006/prep.1999.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stow N D. Herpes simplex virus type 1 origin-dependent DNA replication in insect cells using recombinant baculoviruses. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:313–321. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-2-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stow N D, Hammarsten O, Arbuckle M I, Elias P. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA replication by mutant forms of the origin binding protein. Virology. 1993;196:413–418. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Suck D. Common fold, common function, common origin? Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:161–165. doi: 10.1038/nsb0397-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]