Abstract

Surveys of underserved patient populations are needed to guide quality improvement efforts but are challenging to implement. The goal of this study was to describe recruitment and response to a national survey of Veterans with homeless experience (VHE).

We randomly selected 14,340 potential participants from 26 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities. A survey contract organization verified/updated addresses from VA administrative data with a commercial address database, then attempted to recruit VHE through 4 mailings, telephone follow-up, and a $10 incentive. We used mixed-effects logistic regressions to test for differences in survey response by patient characteristics.

The response rate was 40.2% (n=5,766). Addresses from VA data elicited a higher response rate than addresses from commercial sources (46.9% vs 31.2%, p<.001). Residential addresses elicited a higher response rate than business addresses (43.8% vs 26.2%, p<.001). Compared to non-respondents, respondents were older, less likely to have mental health, drug, or alcohol conditions, and had fewer VA housing and emergency service visits. Collectively, our results indicated a national mailed survey approach is feasible and successful for reaching VA patients who have recently experienced homelessness. These findings offer insight into how health systems can obtain perspectives of socially disadvantaged groups.

Keywords: Homeless Persons, Survey Research Design and Methods, Veterans, Administrative Data Uses, Primary Care, Patient Assessment and Satisfaction

Nearly 580,000 persons were homeless on a single night in the United States including over 37,000 Veterans.1 Persons who experience homelessness often have high medical, mental health, and social service needs and face challenges in accessing care in traditional outpatient settings.2–6 When persons who have experienced homelessness seek health care, they often report stigma, feeling unwelcome, and difficult encounters with providers and staff.7, 8 Designing health care services to better meet this population’s needs is challenging, in part, by limited integration of patients’ views into research on how health services are designed and delivered, with the exception of qualitative work.3, 9, 10

Health systems face barriers in engaging and recruiting participants for research studies from socially disadvantaged groups, including persons who have experienced homelessness. In a systematic review of research involving hard-to-reach populations, the most common data collection barrier was difficulty maintaining participant contact due to frequent changes in telephone numbers and addresses.11 Patient satisfaction surveys carried out at the site of care risk bias in a positive direction, since satisfied patients tend to return.12 Persons experiencing homelessness present additional challenges due to the episodic nature of homelessness itself.13 Methodologies for reaching a homeless-experienced population can be resource intensive (e.g., requiring flexibility on locations/times of in-person data collection, tracking protocols, staff training, coordination with community agencies).11 This encourages geographically confined studies14,15 often with smaller convenience samples. Indeed, the last national population-based survey of health among people experiencing homelessness took place in 1996.16–19

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is uniquely situated to test strategies to reach homeless-experienced populations. It is the largest provider of health services for homeless-experienced individuals in the U.S.,20 and an early adopter of electronic health records that facilitate health services research.21 In addition, the VA nationally implemented a policy to confirm or update contact information at VA appointments,22 and is committed to enhancing Veterans’ experiences with care.23–25 For instance, the VA uses a mailed Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP), based on the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, to track facility performance on patient experience.26 The SHEP methodology involves one pre-notification, one survey packet, and one reminder, with no incentives or telephone follow-up. The SHEP response rate among Veterans with homeless experience (22%) falls well below that of Veterans without a history of homelessness (38%).27 The magnitude of improvement achievable with more intensive recruitment approaches, including tracking and updating contact information, offering incentives, and conducting telephone-based follow-up (>90% of individuals experiencing homelessness report having mobile phones28, 29), has not been assessed with a homeless-experienced population.

Improving methodologies to reach residentially unstable patients is crucial to improving the responsiveness of health systems to the values, preferences, and experiences of vulnerable populations. In this study, we sought to recruit a national sample of Veterans with homeless experience (VHE) to participate in a survey regarding their primary care experience. The goal of this study is to describe: 1) recruitment methods; 2) availability and types of address information from VA administrative records and commercial software; 3) survey response rates achieved in relation to different address characteristics; and 4) patient characteristics associated with survey response. We then discuss strategies that could increase representation of hard-to-reach populations in future health systems research. Results on primary care experiences have been published elsewhere.30–32

METHODS

The Primary Care Quality and Homeless Service Tailoring (PCQ-HOST) study was designed to examine aspects of primary care service aimed at optimizing care experiences for VHE. In 2012, some VA facilities began to offer tailored primary care for VHE,33 called Homeless-Patient Aligned Care Teams (H-PACTS). The H-PACTS offer smaller panels, street and shelter outreach, dedicated staff, tangible need support, and greater linkages to social services compared to regular VA primary care teams (here, “Mainstream”) which also serve VHE.34 An opportunity to compare patient experiences between H-PACT and Mainstream care arose because many VHE utilize Mainstream care even when an H-PACT has been established in the same VA facility. We invited VHE from H-PACTs and Mainstream care to complete a validated 33-item primary care experience instrument.35 The survey also assessed predisposing, enabling/impeding, and need factors outlined in the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations.36 In total, the 11-page survey had 81 items and took an estimated 25–30 minutes to complete on paper.37

We contracted a professional survey organization to survey VHE. Additional information on the contracting process and contracted activities are available in the Digital Supplement. The VA Central Institutional Review Board and VA Research and Development committees at the investigators’ four institutions approved the protocol. See the Digital Supplement for more details on Institutional Review Board and Information Security considerations for VA contracting.

Survey sampling.

Study sites.

We used VA administrative records to identify facilities with the largest H-PACTs in 2017. Of the 28 facilities identified, 26 had H-PACTs open during study recruitment (March 1, 2018 through October 1, 2018) and respondents were randomly selected from these facilities.

Sampling frame.

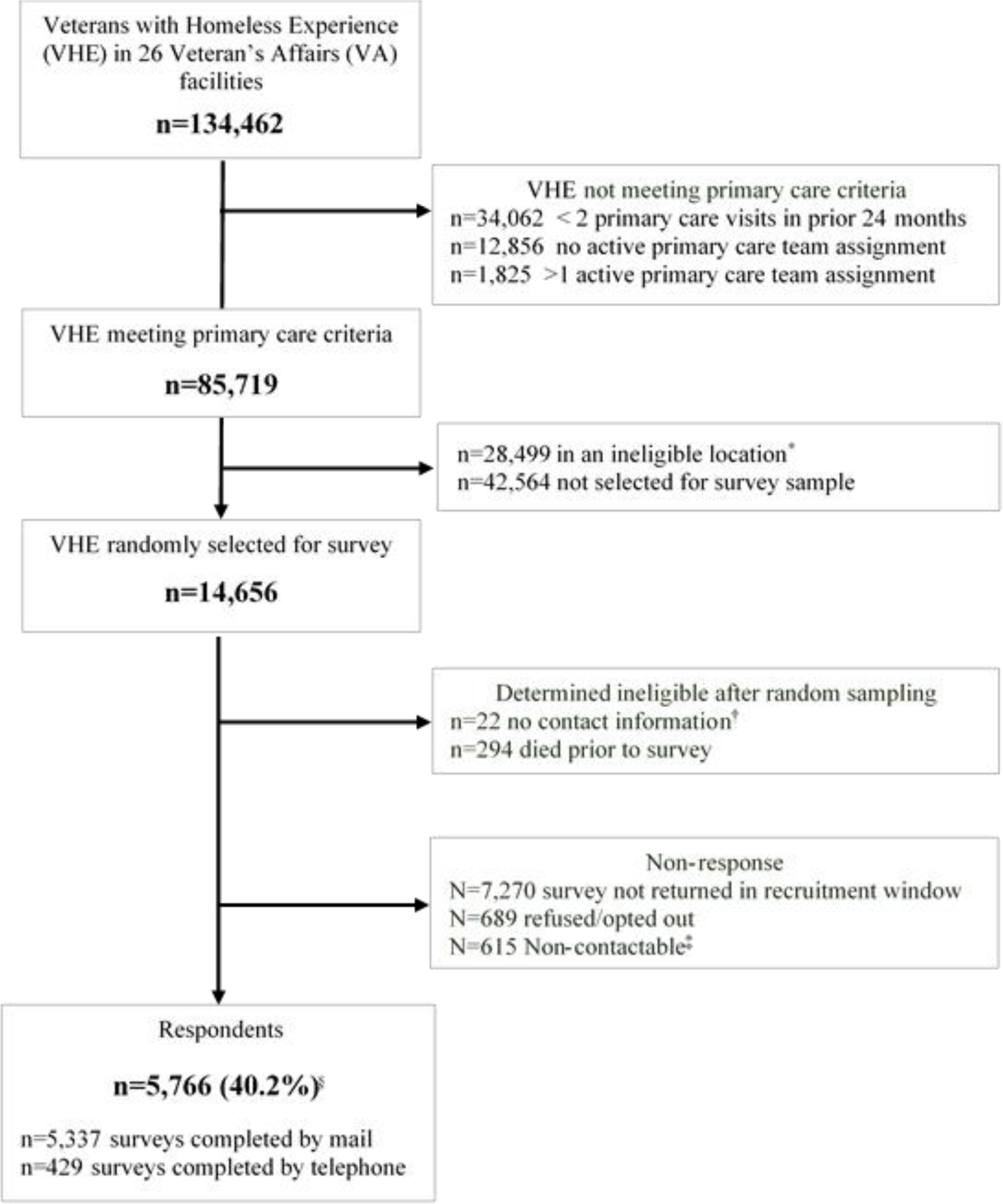

Figure 1 depicts inclusion and exclusion criteria for the sampling frame. We used VA electronic records to identify a sample of Veterans with evidence of homelessness and primary care use from an H-PACT or Mainstream primary care team at a study site. Veterans qualified as having had homeless experience if, in the 30 months preceding November 15, 2017, they had at least one International Classification of Disease (ICD) diagnostic code for housing instability or homelessness, or one use of a VA Homeless Program service (Appendix A). This definition aligns with prior research identifying homelessness in VA records.38, 39 We defined VHE as being engaged in primary care if they had ≥2 primary care visits at the same VA facility in the 24 months preceding November 15, 2017. Next, we queried a VA primary care assignment database to determine if VHE received their primary care in an H-PACT or Mainstream primary care team.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of inclusion/exclusion criteria and survey respondents in the Primary Care Quality and Homeless Service Tailoring (PCQ-HOST) study. Exclusion criteria were applied sequentially

* Ineligible primary care locations are clinics in locations without any Homeless-Patient Aligned Care Teams

† No address or telephone contact information in either VA administrative records or in commercially-available address verification software. No attempt was made to reach these VHE.

‡ VHE who could not be reached by either mail (address missing/non-deliverable) or phone (incorrect number/disconnected)

§ Percentage is calculated based on a denominator (n=14,340) which excludes the 316 VHE that were determined ineligible after random sampling

Sample selection.

Because some VA facilities implemented multiple H-PACTs, the final sample consisted of 29 H-PACTs at 26 VA facilities. One of the 29 H-PACTs was much larger than the others. To avoid overrepresentation of this larger H-PACT, we selected all eligible patients from the 28 smaller H-PACTs and then selected a random subsample of 1,000 patients from the larger H-PACT.

Mainstream patients at each facility were generally sampled in a 1:2 ratio with H-PACT patients at the same facility. This ratio was chosen to offer adequate power for two distinct goals (a) comparing H-PACT to Mainstream (Aim 1 of the proposed study), and (b) analyzing variations among 29 H-PACTs that differed in multiple aspects of service design (Aim 2). In facilities with the smallest H-PACTs (<150 VHE per site), the sampling ratio of Mainstream: H-PACT patients was increased to ensure adequate recruitment of Mainstream patients (n ≥ 60) at that facility. If the H-PACT was located in a community-based outpatient clinic, only Mainstream patients at the same community-based location were randomly sampled. Similarly, if the H-PACT was in a major VA medical facility, only Mainstream patients at that facility were randomly sampled. In total, 14,656 VHE were selected for recruitment.

Exclusion criteria.

Similar to SHEPs methodology 27, we excluded VHE who died before surveys were mailed (n=294, 2%) as well as those with no address or telephone information (n=22, <.02%). Thus, 14,340 VHE were considered eligible for potential participation and served as the denominator for computing response rates.

Recruitment.

Address Verification, Updating, and Origin Classification.

By policy, VA health staff update contact information at each VA appointment.22 For this study, a contracted professional survey organization, Strategic Research Group (SRG), submitted names, addresses and telephone numbers from VA records to a commercial address verification service, MelissaData, prior to each survey mailing. MelissaData (a) helped to standardize VA-provided addresses for United States Postal Service (USPS) formatting, (b) coded addresses as residential, business, or unknown, and (c) identified addresses that were different from the VA-provided address. SRG also utilized other sources to update addresses including informants and, rarely, online searches. As described below, the study process allowed for multiple sequential and iterative address updates based on new information (see Digital Supplement for even greater detail). We used the address associated with the final recruitment contact attempt (e.g, Final Address) for comparing response rates of six types of address origins: 1) VA Address, 2) MelissaData Address, 3) MelissaData Address Changed Back to VA address, 4) Online Search Address, 5) Informant Address, 6) No Valid Address.

Due to the VA policy of updating contact information at each appointment,22 the VA-identified address (VA Address) was presumed to be the most recent and best address unless one of the following specific situations occurred. When there was a difference between the VA address and the address identified by MelissaData, SRG conducted a professional assessment to determine the likely validity of the MelissaData-provided address (MelissaData Address) relative to the VA address. For example, if the MelissaData-provided address was in the same state as the patient’s VA facility for care, while the VA-provided address was not, then the MelissaData-provided address was utilized on the first attempt.

Anytime a mailing yielded returned mail (i.e. “Return to Sender”, “Addressee not at address”), SRG attempted to identify an additional address for subsequent mailings. For instance, if a VA Address resulted in returned mail, then the MelissaData Address was utilized next. Alternatively, if the MelissaData Addresses resulted in returned mail, then a VA address was attempted (MelissaData Address Changed Back to VA address). If the address(es) available from both VA and MelissaData resulted in returned mail, then SRG conducted an online search of White Pages Premium, and rarely, Google (Online Search Address). If the potential participant did not respond to any mailing, then SRG attempted to contact the VHE by telephone.

Aside from returned mail, the other impetus for an address to be updated was if an informant provided an alternate address (Informant Address). Usually, the informant was the Veteran who, reached by telephone, provided a more accurate or convenient address. Other informant updates were rare but included: (1) Veteran called SRG after receiving the initial notice to request that survey materials be mailed to a more convenient address (n=21); (2) unidentified informant called to provide a different mailing address (n=3); (3) USPS designated a forwarding address when mail was returned (n=4). If SRG could not identify another address after a returned mailing, they advanced to telephone follow-up. If the Veteran could not be reached by address or phone (no mailing address and disconnected phone / call attempts exhausted), then SRG ceased recruitment (No Valid Address).

Mail and telephone contact.

Recruitment occurred in four waves, approximately every 5–6 weeks between March and August of 2018. Recruitment closed on October 1, 2018. Recruitment in waves permitted termination of recruitment once the target number of respondents was achieved, without committing to costs for surveys exceeding the number required. Each wave included: a prenotification letter (and contact information to opt out of further recruitment); a survey packet with a $1 pre-incentive sent 10 days later; a reminder post-card one week later; and a second full survey packet one week after the reminder (where necessary). After two more weeks, SRG telephoned non-respondents with the option to complete the survey by phone or to have a ‘replacement’ survey packet mailed, including to a different address. See Digital Supplement for examples of all mailed survey-related materials. SRG telephoned VHE up to five times and left up to two voicemails over a four-week window. We chose to include telephone follow-up for VHE because prior reports found that 90% of VHE own a telephone and are accessible for health-related communications29 and 98% of our sample had a telephone number available in VA administrative records.

In waves 3 and 4, the second survey packet was mailed two weeks after the post-card reminder instead of one to allow more time for non-deliverable mail returns, address look-up, and telephone contact. In all waves, the letter, survey packet, and postcard reminder mailings included contact information for SRG, the IRB, and the principal investigator. Veterans who completed the survey were mailed a thank-you letter with a $10 prepaid VISA card.

Study variables.

Survey response.

We calculated survey response as the percentage of potentially eligible Veterans in the sampling frame who completed the survey.40 Veterans with address or telephone information at time of recruitment were considered potentially eligible, even if that contact information was later determined to be invalid (e.g., non-deliverable mail, disconnected telephone number).

Residential/Business Classification.

MelissaData classified addresses as residential, business, or unknown address types. To determine if business addresses were likely to be residences where VHEs could receive mail (e.g., shelter, hotel, etc), SRG conducted a manual review of 100 randomly selected addresses.

Veteran characteristics.

We extracted sociodemographic characteristics of survey respondents and non-respondents from VA administrative records based on a 24-month lookback from November 15, 2017. We chose predisposing, enabling/impeding, and need factors that could be encompassed by the Andersen-Gelberg Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations,36 and other characteristics associated with survey response rates in other studies.41–43 Predisposing characteristics included age, gender, race, and marital status. Enabling/impeding characteristics included low income. We configured this as a 3-level variable based on <50% of the federal poverty standard for an individual in 2015 (<$5,885), between 50% and 100% of the federal poverty standard ($5,885-$11,770) and above that standard.44 Need characteristics included the medical and mental conditions counted by Elixhauser, using both ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM systems.45 To that we added diagnostic codes for traumatic brain injury, injury from extreme hot or cold, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Because Veterans who are highly engaged with VA health services might be more willing than those with lower engagement to participate in an assessment of VA services, we quantified VA service use in the 24 months prior to recruitment. Specifically, the number of health care visits (primary care and emergency department; inpatient hospitalizations) were grouped into high and low categories after assessing the distribution: persons in the top third of primary care use (>5 visits in 24 months); persons in the top 10% of emergency department use (>8 visits in 24 months); and persons with more than one hospitalization. We also created indicators for use of VA social service programs which are specifically for Veterans who are homeless or unstably housed (appendix A).

Analysis.

We conducted two primary analyses. In the first analysis, we calculated response rates in relation to the address origin and residential/business classification. In the second, we characterized response rates in relation to Veteran characteristics determined from VA administrative health records. We used mixed effects logistic regression models to test for bivariate associations of address origin, residential or business classification, and Veteran characteristics with survey response. To account for the stratified random sampling design, the models included a random effect for site (n=26) and a fixed effect for clinic type (H-PACT vs Mainstream). For characteristics with multiple categories (e.g., race/ethnicity), we report the p-value from a Wald joint test of significance. Variables that were statistically associated with survey response at p<0.01 in the bivariate analyses were included in a multivariable model to describe those characteristics independently associated with survey response, with similar adjustments for study design.

RESULTS

Survey Response.

Of the 14,340 VHE chosen for potential participation, 5,766 (40.2%) completed the survey. The four sequential waves of recruitment yielded response rates of 42.6%, 39.1%, 39.7%, and 39.4%, respectively. There were 689 VHE (4.8%) who refused or opted out (Figure 1). A small percentage of VHE (4.3%, n=615) had non-viable contact information (e.g., non-deliverable mail coupled with disconnected telephone number), while 7,270 (49.6%) had contact information but did not respond to contact attempts before the end of recruitment (Figure 1). Among respondents, 5,337 (92.6%) completed the survey by mail and 429 (7.4%) by telephone. Based on direct contract cost, each completed survey cost $92 including labor, materials, printing, mailing, and incentives (See Digital Supplement for additional commentary on contracting cost and justification).

Completeness of VA Address Records.

For the initial recruitment mailing, 12,635 (88.1%) surveys were sent to an address obtained from VA administrative records. However, 8,577 (67.8%) of these addresses needed to be cleaned, formatted or appended to meet the USPS standards. Another 1,557 (10.9%) surveys were sent to an address obtained from MelissaData because professional review suggested the alternate address was more likely to be valid than the VA-provided address. Finally, 148 (1.0%) VHE had initial recruitment attempted by phone only, due to lack of viable address information in either VA administrative records or MelissaData search results.

Final Mailing Attempts.

The study process allowed for multiple sequential and iterative address updates based on returned mail or informant updates throughout recruitment. Of the final mailing attempts, 10,651 (74.3%) were VA Addresses, 953 (6.7%) were MelissaData addresses, and 229 (1.6%) were MelissaData Addresses Changed Back to VA addresses. Another 746 (5.2%) final mailing attempts were to addresses obtained from Online Searches and 820 (5.7%) were obtained from Informants. There were 941 (6.6%) VHE with No Valid Address where all mailings resulted in returned mail and the Veteran was never reached by phone (phone disconnected or all call attempts exhausted).

Response Rate by Final Mailing Address.

Response rates differed according to the final mailing address (p <.001; Table 1) with the highest response rate obtained for VA addresses. The response rate for Veterans in this group was 46.9%. Similarly, a response rate of 44.8% was obtained for Veterans with an Informant Address. The response rate was somewhat lower for Veterans with MelissaData addresses (31.4%) and MelissaData Addresses Changed Back to VA addresses (21%). Veterans with an Online Search addresses had a lower response rate (7.6%). Veterans with No Valid Address had a response rate of 0%.

Table 1.

Survey response for the origin of address associated with the last recruitment contact attempt

| Address Origin* | Total N (col %) |

Completed Surveys N |

Response Rate %** |

|---|---|---|---|

| VA Address | 10651 (74.2) | 4995 | 46.9 |

| MelissaData Address | 953 (6.6) | 299 | 31.4 |

| MelissaData Address Changed Back to VA address | 229 (1.6) | 48 | 21.0 |

| Online Search Address | 746 (5.2) | 57 | 7.6 |

| Informant Address | 820 (5.7) | 367 | 44.8 |

| No Valid Address | 941 (6.6) | 0 | 0.0 |

|

| |||

| Overall | 14340 | 5766 | 40.2 |

Mailings started with addresses obtained from VA records (when available), and utilized alternative addresses as needed. The various changes are presented sequentially (down column). Here, we present response rate for the last recruitment contact attempt. MelissaData refers to a commercial address software. Informant addresses involves new contact information provided by mail recipient. The address used on final attempt reflected, variously, professional assessment of the most credible address, failure of a previously attempted address type, and/or request from the respondent.

Response rate calculated as number of completed surveys divided by total sent.

Response Rate by Residential/Business Address Type.

Of the final mailing addresses, 10,553 (73.6%) were classified as residential, 1,686 (11.7%) as business, and 2,101 (14.7%) as unknown. Of 100 business addresses randomly selected for manual review, 83% were potential residences or service providers for populations experiencing homelessness (e.g., shelters, assisted living facilities, VA residential program, hotels). Survey response rate varied based on address type: 43.8%, 26.2%, and 33.4% for residential, business, and unknown addresses, respectively (p <.001; Table 2).

Table 2.

Survey response for the residential/business classification of addresses associated with the last recruitment contact attempt

| Residential/Business Classification* | Total N (col %) |

Completed Surveys N |

Response Rate %** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residential | 10553 (73.6) | 4622 | 43.8 |

| Business | 1686 (11.8) | 442 | 26.2 |

| Unknown | 2101 (14.7) | 702 | 33.4 |

|

| |||

| Overall | 14340 | 5766 | 40.2 |

MelissaData, a commercial address software, provided an indicator of residential or business for each address that was used for the last recruitment contact.

Response rate calculated as number of completed surveys divided by total sent.

Veteran Characteristics Associated with Survey Response.

Similar to the general population of individuals who have experienced homelessness, the overall sample of VEH was predominantly male (91.8%), over age 50 (69.4%), unmarried (84.6%), and had low income (64.4% living below the Federal Poverty Line) (Table 3). Over 80% of VHE had at least one diagnosed mental health or substance use related disorder with an average of 10.9 primary care visits (SD 9.7), 3.1 emergency department visits (SD 5.4), and 0.96 hospitalizations (SD 2.2), all in the prior 24 months; the majority of VHE (86.7%) had received at least one VA social service for homeless Veterans in the prior 30 months.

Table 3.

Veteran Characteristics and Survey Response

| Overall | Completed surveys | Response rate* | p-value ** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (col %) | N | % | ||

| Primary Care Team | ||||

| H-PACT | 9095 (63.4) | 3394 | 37.3 | <.001 |

| Mainstream | 5245 (36.6) | 2372 | 45.2 | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–49 | 3852 (27.6) | 1074 | 27.2 | <.001 |

| 50–65 | 7746 (54.0) | 3472 | 44.8 | |

| 66+ | 2642 (18.4) | 1220 | 46.2 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 13167 (91.8) | 5260 | 40.0 | .47 |

| Female | 1173 (8.2) | 506 | 43.0 | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 5922 (41.3) | 2422 | 40.7 | |

| Black | 6,106 (42.6) | 2486 | 40.7 | .008 |

| Latino | 1,104 (7.7) | 413 | 37.4 | |

| Other | 345 (2.4) | 133 | 38.9 | |

| Missing | 863 (6.0) | 312 | 36.2 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 2097 (14.6) | 890 | 42.4 | <.001 |

| Divorced/separated | 6936 (48.4) | 2886 | 41.6 | |

| Never married/other | 5307 (37.0) | 1990 | 37.5 | |

| Annual Income | ||||

| Less than $5,885 | 6365 (44.4) | 2503 | 39.3 | |

| $5,885-$11,770 | 2725 (19.0) | 1157 | 42.5 | .009 |

| More than $11,770 | 5250 (36.6) | 2106 | 40.0 | |

| Elixhauser Condition Count (tertiles) | ||||

| 0–2 Score | 4877 (34.01) | 1763 | 36.2 | |

| 3–4 Score | 4974 (33.4) | 1977 | 41.2 | <.001 |

| 5+ Score | 4669 (32.6) | 2026 | 434 | |

| Traumatic brain injury | 501 (3.5) | 178 | 35.5 | .07 |

| Environmental hazards | 49 (0.3) | 22 | 44.9 | .40 |

| Mental health/substance use | ||||

| PTSD | 4167 (29.1) | 1506 | 36.1 | <.001 |

| Depression | 8126 (56.7) | 3236 | 39.8 | .21 |

| Anxiety disorder | 4028 (28.1) | 1609 | 39.9 | .12 |

| Psychotic disorder | 1951 (13.6) | 625 | 32.0 | <.001 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 5848 (40.8) | 2258 | 38.6 | .049 |

| Drug use disorder | 5496 (38.3) | 1999 | 36.4 | <.001 |

| Any of above | 11481 (80.1) | 4503 | 38.2 | <.001 |

| Primary care visits (tertiles) | ||||

| 2–5 | 4477 (31.2) | 1497 | 33.4 | <.001 |

| 6–11 | 5152 (35.9) | 2085 | 40.5 | |

| 12+ | 4711 (32.9) | 2184 | 46.4 | |

| Emergency department visits | ||||

| <8 / Bottom 90% | 12836 (89.5) | 5284 | 41.2 | <.001 |

| >=8 / Top 10% | 1504 (10.5) | 482 | 32.1 | |

| Any Hospitalization | 5035 (35.1) | 1967 | 39.1 | .007 |

| Receipt of VA social services | ||||

| Health care for homeless Veterans | 9920 (69.2) | 3747 (37.8) | 37.8 | <.001 |

| Grant and per-diem voucher | 3865 (27.0) | 1324 (34.3) | 34.3 | <.001 |

| HUD-VASH | 8276 (57.7) | 3258 (39.4) | 39.4 | <.001 |

| Justice outreach | 1381 (9.6) | 471 (34.1) | 34.1 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; H-PACT = Homeless Patient Aligned Care Team; HUD-VASH = U.S. Housing and Urban Development – Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing

Response rate calculated as number of completed surveys divided by total sent.

Mixed effect logistic regressions, run separately for each patient characteristic listed in the table, tested for bivariate associations of patient characteristics with survey response. To account for the sampling design, the models included a random effect for study site and fixed effect for clinic type (H-PACT vs mainstream). For patient characteristics with multiple categories (e.g., race/ethnicity), we report the p-value from a Wald joint test of significance.

Several patient characteristics were associated with survey response (Table 3). For instance, we found relatively higher response rates for VHE receiving Mainstream primary care (versus the tailored H-PACT), those ages 66 or older, and females. Survey response rates were somewhat lower for VHE with documented diagnoses of post-traumatic stress disorder, psychotic disorders, and drug or alcohol use disorders. Survey response rates were higher among VHE with greater numbers of primary care visits, and lower among VHE with greater use of VA social services and emergency department visits. All of these comparisons were statistically significant at p<.01.

Most associations between patient characteristics and survey response remained statistically significant when tested simultaneously in a multivariable model (Table 4). For example, the odds of survey response were greater for VHEs receiving Mainstream primary care (versus the tailored H-PACT), those age 66 and older, and female VHE. In addition, the odds of survey response were higher for VHEs receiving more primary care visits, and lower for VHEs using VA social services, those with frequent ED visits, and those with diagnoses of psychotic disorders or drug use disorder.

Table 4.

Adjusted odds of response according to Veteran characteristics

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Intervals | p-values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Care Team | |||

| Mainstream | REF | - | - |

| H-PACT | 0.82 | 0.76–0.89 | <.001 |

| Age | |||

| 18–49 | REF | - | - |

| 50–65 | 1.95 | 1.78–2.14 | <.001 |

| 66+ | 1.86 | 1.65–2.09 | <.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | REF | - | - |

| Female | 1.18 | 1.03–1.34 | .015 |

| Race | |||

| White | REF | - | - |

| Black | 0.98 | 0.91–1.07 | 0.68 |

| Latino | 1.01 | 0.88–1.16 | 0.90 |

| Other | 1.01 | 0.80–1.28 | 0.91 |

| Missing | 0.85 | 0.73–0.99 | 0.04 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | REF | - | - |

| Divorced/separated | 0.96 | 0.87–1.07 | 0.47 |

| Never married/other | 0.91 | 0.81–1.02 | 0.09 |

| Annual Income | |||

| Less than $5,885 | REF | - | - |

| $5,885-$11,770 | 1.05 | 0.95–1.15 | 0.34 |

| More than $11,770 | 0.96 | 0.88–1.04 | 0.27 |

| Elixhauser Condition Count (tertiles) | |||

| 0–2 Score | REF | - | - |

| 3–4 Score | 1.21 | 1.11–1.33 | <.001 |

| 5+ Score | 1.36 | 1.21–1.52 | <.001 |

| Mental health/substance use | |||

| PTSD | 0.92 | 0.85–1.00 | 0.06 |

| Psychotic disorder | 0.71 | 0.64–0.80 | <.001 |

| Drug use disorder | 0.84 | 0.78–0.92 | <.001 |

| Primary care visits (tertiles) | |||

| 2–5 | REF | - | - |

| 6–11 | 1.25 | 1.15–1.37 | <.001 |

| 12+ | 1.67 | 1.51–1.84 | <.001 |

| Emergency department visits | |||

| <8 / Bottom 90% | REF | - | - |

| >=8 / Top 10% | 0.65 | 0.57–0.74 | <.001 |

| Any Hospitalization | 0.87 | 0.79-.94 | .001 |

| Receipt of VA social services | |||

| Health care for homeless Veterans | 0.86 | 0.79–0.94 | <.001 |

| Grant and per-diem voucher | 0.86 | 0.79–0.94 | 0.001 |

| Justice outreach | 0.97 | 0.86–1.11 | 0.71 |

Estimates obtained from multivariable mixed effect logistic regression model of survey response. Predictors included Veteran characteristics associated with survey response at p<0.01 in bivariate analyses (Table 3).

Abbreviations: PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; H-PACT = Homeless Patient Aligned Care Team; HUD-VASH = U.S. Housing and Urban Development – Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing

DISCUSSION

Successful efforts to solicit the views of residentially unstable patients could help to improve the responsiveness of health systems to their values, preferences, and experiences. This study shows how large-scale efforts to include homeless-experienced patients in health services research can succeed. The findings challenge conventional wisdom that recruiting homeless-experienced patients by mail or telephone is impossible due to frequently changing contact information. Our efforts to survey a homeless-experienced patient population achieved a 40.2% response rate, roughly double the rate typically achieved in this population with the VA’s standard patient experience methodology (e.g., SHEP survey)27 and on par or better than response rates reported among general outpatients in VA and non-VA settings.46 Thus, health care systems that wish to include perspectives of their patients who may be homeless-experienced, unstably housed, or otherwise have high residential mobility (lower-income, renters, younger families47) could, if they wish, take additional steps to use data they currently have in their information systems to reach these patients for health services research.

Data that are regularly collected in VA Health Operations do represent an asset to this survey and may not be equivalently available in other health systems. For instance, VA staff confirm/update contact information at each appointment,22 which resulted in an address database with high agreement (88.2%) when compared to commercial address verification. However, this administratively-collected address database does not automatically assure high response rates, as is evident in the 23% response rate to VA’s standard SHEP survey of a similar homeless patient population.27 Our study’s 40.2% response rate may in part reflect the additional address confirmation steps we used when compared to SHEP’s methodology. Specifically, we iteratively updated contact information by: using a commercial address database; tracking returned mail; and integrating informant-provided information. Other methodological decisions that likely contributed to the survey response include our use of participant incentives and telephone follow-up, two techniques common to smaller research studies but not to larger-scale consumer feedback methods such as the SHEP.27

Our recruitment methodologies incurred additional monetary burdens with each completed survey costing $92 based on direct contractual cost. Our contracting costs included not just materials, postage and handling costs, and incentives costs, but also salary costs for staffing effort for address updating and verification, staffing effort for robust telephone follow-up, and staffing effort for senior researchers and project management. Prior research on survey costs typically do not include staff salary as part of costs per completed survey which makes cost comparisons difficult. However, one Australian study,48 did included some staff salary as part of cost estimates. That study reported $26 in 2018 US dollars ($22.93 2011-Australian dollars) per completed survey for a mailed survey with no follow-up attempt (response rate of 7.5%) and $62 in 2018- US dollars ($53.84 2011- Australian dollars) per completed survey for a personalized telephone survey (response rate of 30.2%). The response rates achieved would be unacceptably low for health services research.49 Whether healthcare systems are willing to spend additional costs on recruitment strategies to reach patients with changing contact information is unknown. However, we suggest such additional efforts are necessary to reach vulnerable populations with frequently changing contact information and other social determinants of poor health. The rationale for including patients from historically marginalized groups is that their insights will help health systems promote and improve health equity. An important avenue for future research is to estimate costs associated with specific recruitment processes to optimize the value of patient experience surveys in relation to survey response.

These findings have implications for future studies aimed at including vulnerable populations with unstable housing. First, we retained business addresses in the initial sampling frame. Our analysis of business addresses and observation of relatively poor response rate for this group may signal a transient subpopulation residing in motels, shelters, etc. More expeditious recruitment methods may be necessary to contact these individuals who are in highly transient situations, such as shelters or motels. When a business address is discovered, it may be helpful to accelerate follow-up efforts, or to immediately switch from mailed recruitment to phone-based recruitment. Second, our finding of lower survey response among Veterans empaneled in VA’s H-PACT or recently using VA homeless services likely does reflect the enduring challenge of recruiting patients with the greatest social vulnerability and greater housing instability. Researchers wishing to include VHE in health systems research may need to oversample those with traditionally lower response rate - those who are younger, have a medical history indicating substance use disorder and serious mental illness, and those with frequent use of social services and lower engagement in primary care. Applying these sampling modifications as well as above-mentioned modifications to traditional survey methodology could improve representation of hard-to-reach groups.

Traditional survey methodology has evolved in recent years towards greater inclusion of internet-based approaches for recruitment and survey completion. Our study did not test that approach. However, we recently documented lower uptake of VA’s internet-based health messaging system by members of this particular survey sample who were older, African-American and had addiction problems.50 For this reason we caution that internet-based survey methods could decrease the representation of populations like VHEs. Further research is needed to assess the impact and feasibility of e-mail and web-based methodologies for homeless experienced and other vulnerable populations.

This study has limitations and strengths. Because we did not randomize Veterans to different methodologies for updating or not updating VA addresses, our conclusions about the relative benefits of strategies to verify and update addresses reflect inferences from observation. Second, we retained detailed information on final address records with less historical information on each contact attempts per VHE. This limited our ability to estimate cumulative response rate by total number and combinations of contact attempts with precision. Third, this study was entirely conducted within the Veterans Health Administration. Its generalizability to other health care settings is speculative. Most notably, the VA has a robust electronic medical record system with integrated contact information, social and housing program records, and medical and mental health service records, which are all available to researchers. And yet, our study highlights strategies that could be employed in other healthcare settings (e.g., address verification, repeat mailings, telephone follow-up, paid incentives) to include vulnerable patients in health systems research. Finally, as a strength, we sought survey responses from a database of all patients, rather than just those approachable in the waiting room.

Despite limitations, this is a first study to report on a national mail and telephone survey effort to engage patients with homeless experiences in population-based health systems research. Improving strategies to reach residentially unstable patients is crucial to improving the responsiveness of health systems to the values, preferences, and experiences of vulnerable populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development Branch (IIR 15-095). Dr. Jones acknowledges support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002538 and KL2TR002539, and an HSR&D Career Development Award (CDA 19-233, Award No IK2HX003090-01A2).

Abbreviations:

- VA

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

- SHEP

Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients

- VHE

Veterans with homeless experience

- H-PACTS

Homeless-Patient Aligned Care Teams

- SRG

Strategic Research Group

- USPS

United States Postal Service

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer

Publisher's Disclaimer: Views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not represent positions or views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health, or US government.

References

- 1.PART 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness. The 2019 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress (2019).

- 2.Gelberg L, Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P. Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. American Journal of Public Health 1997;87(2):217–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruenewald DA, Doan D, Poppe A, Jones J, Hutt E. “Meet Me Where I Am”: Removing Barriers to End-of-Life Care for Homeless Veterans and Veterans Without Stable Housing. Am J Hosp Palliat Care Dec 2018;35(12):1483–1489. doi: 10.1177/1049909118784008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kertesz SG, Hwang SW, Irwin J, Ritchey FJ, Lagory ME. Rising Inability to Obtain Needed Health Care Among Homeless Persons in Birmingham, Alabama (1995–2005). J Gen Intern Med 2009;24(7):841–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0990-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kertesz SG, McNeil W, Cash JJ, et al. Unmet need for medical care and safety net accessibility among Birmingham’s homeless. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine Feb 2014;91(1):33–45. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9801-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGuire J, Gelberg L, Blue-Howells J, Rosenheck RA. Access to primary care for homeless veterans with serious mental illness or substance abuse: a follow-up evaluation of co-located primary care and homeless social services. Adm Policy Ment Health Jul 2009;36(4):255–64. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0210-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baggett TP, O’Connell JJ, Singer DE, Rigotti NA. The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: a national study. Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. American Journal of Public Health Jul 2010;100(7):1326–33. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kushel MB, Vittingoff E, Haas JS. Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA. 2001;285(2):200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varley AL, Montgomery AE, Steward J, et al. Exploring Quality of Primary Care for Patients Who Experience Homelessness and the Clinicians Who Serve Them: What Are Their Aspirations? Qual Health Res May 2020;30(6):865–879. doi: 10.1177/1049732319895252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCabe S, Macnee CL, Anderson MK. Homeless patients’ experience of satisfaction with care. Archives of psychiatric nursing Apr 2001;15(2):78–85. doi: 10.1053/apnu.2001.22407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, et al. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC medical research methodology 2014;14(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burroughs TE, Waterman BM, Gilin D, Adams D, McCollegan J, Cira J. Do On-Site Patient Satisfaction Surveys Bias Results? The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 2005/03/01/ 2005;31(3):158–166. doi: 10.1016/S1553-7250(05)31021-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cowan CD, Breakey WR, Fischer PJ. The methodology of counting the homeless 1986:170–175.

- 14.Gelberg L, Robertson MJ, Arangua L, et al. Prevalence, distribution, and correlates of hepatitis C virus infection among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Public health reports (Washington, DC : 1974) Jul-Aug 2012;127(4):407–421. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Susser E, Conover S, Struening EL. Problems of epidemiologic method in assessing the type and extent of mental illness among homeless adults. Hosp Community Psychiatry Mar 1989;40(3):261–5. doi: 10.1176/ps.40.3.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burt MR, Aron LY, Lee E, Valente J. Helping America’s Homeless: Emergency shelter or affordable housing? The Urban Institute Press; 2001:366. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E, Haas JS. Factors Associated With the Health Care Utilization of Homeless Persons. JAMA 2001;285(2):200–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.2.200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burt MR, Aron LY. Helping America’s homeless: Emergency shelter or affordable housing? 2001.

- 19.United States Census Bureau. National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients (NSHAPC) Accessed April 15, 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/nshapc.html

- 20.US Department of Veterans Affairs. STATEMENT OF PETER H. DOUGHERTY, DIRECTOR, HOMELESS VETERANS PROGRAMS, DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS US Department of Veterans Affairs, editor. Washington DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans DC, Nichol WP, Perlin JB. Effect of the implementation of an enterprise-wide Electronic Health Record on productivity in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Econ Policy Law Apr 2006;1(Pt 2):163–9. doi: 10.1017/s1744133105001210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA DIRECTIVE 1230, OUTPATIENT SCHEDULING PROCESSES AND PROCEDURES, APPENDIX C Veterans Health Administration; July 15, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson KM, Helfrich C, Sun H, et al. Implementation of the patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration: associations with patient satisfaction, quality of care, staff burnout, and hospital and emergency department use. JAMA internal medicine 2014;174(8):1350–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosland A-M, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. The American journal of managed care 2013;19(7):e263–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Toole TP, Johnson EE, Borgia ML, Rose J. Tailoring outreach efforts to increase primary care use among homeless veterans: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of general internal medicine 2015;30(7):886–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.VHA Office of Analytics and Business Intelligence. The SHEP Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) Survey Technical Specifications 2018. http://vaww.car.rtp.med.va.gov/programs/shep/shep.aspx

- 27.Jones AL, Hausmann LR, Kertesz S, et al. Differences in Experiences With Care Between Homeless and Nonhomeless Patients in Veterans Affairs Facilities With Tailored and Nontailored Primary Care Teams. Medical care 2018;56(7):610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhoades H, Wenzel SL, Rice E, Winetrobe H, Henwood B. No digital divide? Technology use among homeless adults. Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness 2017/01/02 2017;26(1):73–77. doi: 10.1080/10530789.2017.1305140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McInnes DK, Fix GM, Solomon JL, Petrakis BA, Sawh L, Smelson DA. Preliminary needs assessment of mobile technology use for healthcare among homeless veterans. PeerJ 2015;3:e1096–e1096. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riggs KR, Hoge AE, DeRussy AJ, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with nonfatal overdose among veterans who have experienced homelessness. JAMA Netw Open Mar 2 2020;3(3):e201190. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kertesz SG, deRussy AJ, Kim Y-i, et al. Comparison of Patient Experience Between Primary Care Settings Tailored for Homeless Clientele and Mainstream Care Settings. Medical Care 2021;Publish Ahead of Printdoi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000001548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabrielian S, Jones AL, Hoge AE, et al. Enhancing Primary Care Experiences for Homeless Patients with Serious Mental Illness: Results from a National Survey. J Prim Care Community Health Jan-Dec 2021;12:2150132721993654. doi: 10.1177/2150132721993654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gabrielian S, Gordon AJ, Gelberg L, et al. Primary Care Medical Services for Homeless Veterans. Federal Practitioner October, 2014. 2014;(October):10–11, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Toole TP, Johnson EE, Aiello R, Kane V, Pape L. Tailoring Care to Vulnerable Populations by Incorporating Social Determinants of Health: the Veterans Health Administration’s “Homeless Patient Aligned Care Team” Program. Preventing chronic disease 2016;13:E44–E44. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.150567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kertesz SG, Pollio DE, Jones RN, et al. Development of the Primary Care Quality-Homeless (PCQ-H) instrument: a practical survey of homeless patients’ experiences in primary care. Med Care Aug 2014;52(8):734–42. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Research 2000;34(6):1273–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berry SH. How To Estimate Questionnaire Administration Time Before Pretesting: An Interactive Spreadsheet Approach. Survey Practice 2009;2(3) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peterson R, Gundlapalli AV, Metraux S, et al. Identifying Homelessness among Veterans Using VA Administrative Data: Opportunities to Expand Detection Criteria. PLoS One 2015;10(7):e0132664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kertesz SG, Holt CL, Steward JL, et al. Comparing homeless persons’ care experiences in tailored versus nontailored primary care programs. American journal of public health Dec 2013;103 Suppl 2:S331–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips AW, Friedman BT, Durning SJ. How to Calculate a Survey Response Rate: Best Practices. Acad Med Feb 2017;92(2):269. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zaslavsky AM, Zaborski LB, Cleary PD. Factors affecting response rates to the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study survey. Med Care Jun 2002;40(6):485–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones AL, Mor MK, Haas GL, et al. The Role of Primary Care Experiences in Obtaining Treatment for Depression. J Gen Intern Med Aug 2018;33(8):1366–1373. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4522-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res Feb 2000;34(6):1273–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Department of Health and Human Services. Annual Update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines. Federal Register 2015;80(80 FR 3236):3236–3237. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying Increased Risk of Readmission and In-hospital Mortality Using Hospital Administrative Data: The AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care Jul 2017;55(7):698–705. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scholle SH, Vuong O, Ding L, et al. Development of and field-test results for the CAHPS PCMH survey. Medical care 2012;50(Suppl):S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coulton C, Theodos B, Turner MA. Residential mobility and neighborhood change: Real neighborhoods under the microscope. Cityscape 2012:55–89.

- 48.Sinclair M, O’Toole J, Malawaraarachchi M, Leder K. Comparison of response rates and cost-effectiveness for a community-based survey: postal, internet and telephone modes with generic or personalised recruitment approaches. BMC medical research methodology Aug 31 2012;12:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.JAMA. Instructions for Authors Accessed November 4, 2021. American Medical Association [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones AL, Gelberg L, deRussy AJ, et al. Low Uptake of Secure Messaging Among Veterans With Experiences of Homelessness and Substance Use Disorders. Journal of Addiction Medicine 2020;Publish Ahead of Printdoi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.