Abstract

Erinacines derived from Hericium erinaceus have been shown to possess various health benefits including neuroprotective effect against neurodegenerative diseases, yet the underlying mechanism remains unknown. Here we found that erinacine S enhances neurite outgrowth in a cell autonomous fashion. It promotes post-injury axon regeneration of PNS neurons and enhances regeneration on inhibitory substrates of CNS neurons. Using RNA-seq and bioinformatic analyses, erinacine S was found to cause the accumulation of neurosteroids in neurons. ELISA and neurosteroidogenesis inhibitor assays were performed to validate this effect. This research uncovers a previously unknown effect of erinacine S on raising the level of neurosteroids.

Keywords: Axotomy, Bioactive, Erinacines, Neurodegenerative disease, Neurotrophic factor

1. Introduction

Hericium erinaceus, also known as lion's mane mushroom, is a well recognized culinary and medicinal mushroom. This mushroom has been reported to exhibit beneficial effects on cancer, diabetes, depression, and neurodegenerative diseases [1,2]. The neuroprotective effect of H. erinaceus can be attributed to a variety of unique chemicals, one group of them being erinacines (cyathin diterpenoids) that are rich in the mycelia of H. erinaceus [3]. For example, the encapsulated methanolic extract of H. erinaceus mycelium rich in erinacine A has been found to significantly slow down the cognitive decline in human subjects [4]. So far a variety of erinacines (A-K, P–S) have been isolated from mycelia and characterized [2]. It should be noted that erinacine A-I have been found to enhance the biosynthesis of the nerve growth factor (NGF) in cultured astrocytes, which may be an important contributing factor to their neuroprotective effects [5–8]. In addition, it has been found that force feeding neonatal rats with erinacine A leads to the increase of NGF in both locus coeruleus and hippocampus of the brain [9]. Orally ingested H. erinaceus mycelium ethanol extracts rich in erinacine A, C and S has been shown to enhance the production of NGF and reduce the number and size of Aβ plaques in a mouse model (APP/PS1) of Alzheimer's disease [10]. In another study, APP/PS1 mice fed with purified erinacine A or S also exhibited reduced number and size of Aβ plaques in the cerebral cortex. Surprisingly, the authors did not detect an increase of NGF level in the cerebral cortex of erinacine A or S ingested mice [3]. This suggests that the production of NGF may not be the downstream mechanism for the neuroprotective effect of erinacine A or S. Further study shows that erinacine A and S have different effects on Alzheimer's disease causing Aβ peptide. While both erinacine A and S promotes the degradation of Aβ plaques, only erinacine A prevent the accumulation of insoluble Aβ in APP/PS1 mice [11]. This observation suggests that erinacine A and S may elicit different molecular/cellular mechanisms in protecting against Alzheimer's disease.

While erinacine S has been shown to possess the neuroprotective effect in the neurodegenerative disease animals, all observations are based on animal studies [3,11]. Whether erinacine S affects neurons or non-neuronal cells, and the precise molecular mechanism of this erinacine remains elusive. To understand whether erinacine S acts directly upon neurons, we examine the effect of this erinacine on dissociated primary neurons from mice and rats. Surprisingly, the neurite outgrowth of primary neurons from both CNS and PNS are significantly enhanced after incubating with erinacine S. Because neurite outgrowth is the fundamental event that leads to nerve regeneration, we examined and confirmed that erinacine S indeed promotes axon regeneration in physically severed PNS neurons and neurite regeneration of CNS neurons cultured in a regeneration inhibiting environment. To understand the molecular mechanism of erinacine S on promoting neuronal regeneration, RNA-seq technology was utilized to examine the transcriptomic changes of CNS neurons after 16 and 48 h of incubation with erinacine S. Interestingly, instead of NGF biosynthesis, we discovered that erinacine S promotes the accumulation of neurosteroids. The effect of erinacine S on neurosteroids was confirmed using ELISA quantification and neurosteroidogenesis inhibitor assays. Neurosteroids have been shown to promote neurite outgrowth, induce neurogenesis, and prevent neuronal apoptosis [12]; all of which explains the neuroprotective effect of erinacine S on Alzheimer's disease and neuronal regeneration.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Antibodies and reagents

Mouse anti-β–III–tubulin antibody TUJ1 (801202) was purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Chicken extracellular chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs, CC117) was from Merck Millipore (Burlington, MA). Mouse nerve growth factor (NGF, N-100) was from Alomone (Jerusalem, Israel).

2.2. H. erinaceus cultures

H. erinaceus (BCRC 35669) was purchased from the Bioresources Collection and Research Center of the Food Industry Research and Development Institute (Hsinchu, Taiwan). H. erinaceus mycelium was obtained by liquid state fermentation. H. erinaceus was transferred from an agar slant onto a potato dextrose agar plate, and incubated at 26 °C for 15 days. After the incubation, a mycelial seed was transferred to a 2 L Erlenmeyer flask and incubated at 120 rpm/min at 25 °C for 5 days. The 2 L flask was scaled up to a 500 L fermenter and then to a 20 tons fermenter for 5 and 12 days, respectively. At the end of the fermentation process, the mycelia were harvested, lyophilized, grounded into powder, and stored in a desiccator at room temperature.

2.3. Erinacine S extraction and purification

95% ethanol was first added to the H. erinaceus mycelium powder and the preparation was ultrasonicated for 2 h. The reflux solution was filtered and concentrated under a vacuum to obtain crude extract. The water/ethyl acetate solution (1:1) was then used to differentiate the water layer and the ethyl acetate layer from the crude extract. Silica gel column chromatography (70–230 mesh; 70 × 10 cm) was used to analyze the ethyl acetate layer, and n-hexane/ethyl acetate solution (3:2) was used to perform gradient separation. Erinacine S was obtained using Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography and a subsequent silica column chromatography. Using HPLC, the purity of erinacine S was determined to be 99.1%. The chemical structure of erinacine S is shown in supplementary material (Fig. S1).

2.4. Erinacine S solution preparation

Erinacine S was dissolved with DMSO into the 10 mg/mL concentrated stock solutions. The 10 mg/mL stock solution was further diluted with cortical neuron maintenance medium or DRG maintenance medium into indicated concentrations. These diluted solutions were equilibrated in a 37 °C CO2 incubator before adding into multiwell plates.

2.5. Poly-l-lysine- or CSPGs coating

100 μg/mL poly-l-lysine (PLL) solution was added to each well of a 6-, 24- or 96-well plate and incubated overnight at room temperature. 20 μL of the 2.5 μg/mL CSPGs solution (CC117, Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA) was dropped onto the center of each PLL-coated well of a 24-well plate then stored in a 4 °C refrigerator overnight. A 1:1000 dilution of goat anti-mouse-IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568 was mixed in with the CSPGs solution to label the CSPGs-coated area. The wells were washed with ddH2O twice before neurons were seeded into these CSPGs-coated wells.

2.6. Primary neuron cultures and analyses

All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University.

Mouse cortical neuron cultures were prepared as described with slight modifications [13]. Briefly, embryos from timed pregnant C57BL/6J adult mice (E17.5) were used. Mouse brains were collected from the embryos, the meninges were carefully removed, and the cortexes were isolated under the dissecting microscope. Cortexes were incubated with 5 mL of digestion medium (0.25% trypsin–EDTA, 10 mM HEPES) at 37 °C for 30 min and dissociated mechanically via trituration. Dissociated cortical neurons were filtered by cell strainer before centrifuged at 80 g for 10 min at room temperature. The cell pellet was resuspended in the cortical neuron plating medium (Minimum Essential Medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 0.6% d-glucose, and 2 mM l-glutamine). 1 × 104 or 8 × 104 neurons were plated into each well of a 96-well or 24-well plate in the cortical neuron plating medium. After 3 h of incubation, the cortical neuron plating medium was replaced with 100 μL or 250 μL of the cortical neuron maintenance medium (neurobasal medium supplemented with 1 × B27 and 0.5 mM l-glutamine). After incubating for 1 additional hour, 100 μL or 250 μL of erinacine S solution (final concentration 1 μg/mL) was added into each well. Dissociated cortical neurons were maintained in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for 2 days. For RNA-seq assays, 6.5 × 106 neurons were plated into the 15-cm culture dishes. After 3 h of incubation, the cortical neuron plating medium was replaced with 20 mL of the cortical neuron maintenance medium. After incubating for 1 additional hour, 20 mL of erinacine S solution (final concentration 1 μg/mL) was added into each culture dish. Dissociated cortical neurons were maintained in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for 16 or 48 h. For the neurosteroidogenesis inhibitor assay, 0.5 μM of ketoconazole (Sigma–Aldrich, K1003) and 25 μM of genistein (Sigma–Aldrich, G6649) were added to each well of a 96-well plate at the same time as erinacine S. Dissociated mouse cortical neurons were maintained in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for an additional 2 days before fixed for immunofluorescence staining. For ELISA quantification of pregnenolone, cell lysates were prepared from dissociated mouse cortical neuron treated with the aforementioned compounds for 2 days. Diethyl ether was used for extracting pregnenolone from cortical neuron lysates before ELISA quantification. Briefly, 1 mL of diethyl ether was mixed with 500 μL of cortical neuron lysates and the top diethyl ether layer was collected. This extraction step was repeated three times before extracted lysates were dried under nitrogen and dissolved in 100 μL of pregnenolone sample dilution buffer from the Pregnenolone ELISA kit (EU0380, FineTest). Pregnenolone ELISA kit was performed according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Rat dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neuron cultures were prepared as described with slight modifications [14]. Briefly, embryos from time pregnant Sprague–Dawley rats (E15.5) were used. Rat spinal cords were collected from the embryos, the meninges were carefully removed, and the DRGs were dissected under the dissecting microscope. DRGs were incubated with 5 mL of digestion medium at 37 °C for 30 min and dissociated mechanically via trituration. Dissociated DRG neurons were centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min at room temperature and the cell pellet was resuspended in the DRG maintenance medium (neurobasal medium supplemented with 1 × B27, 25 ng/mL NGF, and 1 mM l-glutamine). 3 × 103 or 4 × 104 DRG neurons were plated into each well of a 96-well or 24-well plate in 100 μL or 250 μL of the DRG maintenance medium. After 4 h of incubation, 100 μL or 250 μL of erinacine S solution was added into each well. Dissociated DRG neurons were maintained in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for 2 days.

2.7. DRG neuron drop culture and axotomy

Rat DRG neurons were obtained as mentioned above. The drop culture was established by dropping 2 μL of the concentrated DRG neuron mixture (1.5 × 104 neurons per μL) at the center of each grooved ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) coverslip attached to the bottom of a 6-well plate. The grooved EVA coverslips were manufactured using the protocol we established previously [15]. After neuron plating, 6-well plates were first placed into a 37 °C CO2 incubator for 10 min 2 mL of the DRG maintenance medium were then added into each well and incubated for 4 h 1 μM floxuridine and 1 μM uridine were added to each well to curb the growth of mitotic cells. Half of the medium was replaced with the fresh DRG maintenance medium without floxuridine and uridine on day 5. On day 7, the axotomy procedure was performed with a plastic cell scraper. This is immediately followed by replacing half of the medium with the fresh DRG maintenance medium containing 0.2% DMSO (final concentration 0.1%) or 2 μg/mL erinacine S (final concentration 1 μg/mL). Neurons were then cultured in the 37 °C CO2 incubator for an additional 2 days.

2.8. Immunofluorescence staining

For neuron cytotoxicity, neurite outgrowth, neurosteroidogenesis inhibitor assays, neurons were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in 1 × PBS at 37 °C for 15 min. For axotomy analysis, neurons were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in 1 × PBS at 37 °C for 30 min. Fixed neurons were permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 5 min and blocked with 10% BSA in 1 × PBS at 37 °C for 30 min. Neurons were then incubated with the primary antibody diluted in 2% BSA in 1 × PBS and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. This is followed by 1 h of incubation at 37 °C with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody diluted in 2% BSA in 1 × PBS along with 10 μg/mL DAPI.

2.9. Images acquisition and analysis

Fluorescence images were acquired on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a 10x (0.45 N.A) Plan Apo objective lens, an Intensilight epi-fluorescence light source, a Photometrics CoolSNAP HQ2 camera, and Nikon NIS-Elements software.

The ImageJ (v1.43) plugin NeurphologyJ [16] was used for quantifying the total soma number and total neurite length in dissociated cortical and DRG neurons. Total neurite length per neuron was obtained via dividing total neurite length by total soma number.

For quantifying the neuronal regeneration on CSPGs-coated surface, a circular region of interest (ROI) 4810 μm in diameter was selected inside the CSPGs-coated region. Only neurons inside this ROI were quantified by NeurphologyJ.

Fiji (v1.51) was used to quantify DRG axon regeneration after axotomy. Firstly, a rectangular ROI 3000-pixel × 500-pixel was created 200-pixel proximal to the axotomy site to serve as the uninjured axon area. Secondly, a series of rectangular ROIs 3000-pixel × 500-pixel were created from the distal edge of the axotomy site to neuron tips to serve as the regenerated axon areas. The regeneration ratio of each point was calculated by dividing the regenerated axon area by the uninjured axon area.

2.10. RNA extraction, RT-PCR, and RNA-seq

Four groups of total RNA samples (a total of 12) from primary mouse cortical neurons were prepared; each group contains 3 independent repeats. The four groups are: 1) DMSO solvent control treatment for 16 h, 2) 1 μg/mL erinacine S treatment for 16 h, 3) DMSO solvent control treatment for 48 h, and 4) 1 μg/mL erinacine S treatment for 48 h. Total RNAs were extracted from cortical neurons using Blood/Cell total RNA mini kit (RB050, Geneaid, Taiwan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (K1621, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RT-PCR was conducted to ensure the addition of erinacine S does not significantly alter the quantity/level of the overall transcriptome. We selected RNA transcripts of two house-keeping gene, one present in the neurite (beta-actin) and one present in the soma (GAPDH) for the RT-PCR analysis. The primer sequences in this study are as follow: 5′-CCCCTGAACCCTAAGGCCA-3' (beta-actin forward); 5′-CGGACTCATCGTACTCCTGC-3' (beta-actin reverse); 5′-TGTGAACGGATTTGGCCGTATTGG-3' (GAPDH forward); 5′-TGGAAGAGTGGGAGTTGCTGTTGA-3' (GAPDH reverse). It was found that the addition of erinacine S does not alter the expression of these two house-keeping genes (Fig. S2), indicating that the quantity/level of the overall transcriptome is unaltered. For RNA-seq analyses, a detailed procedure is provided (Fig. S3). RNA sample preparations were performed according to the official Illumina protocol. The SureSelect Strand-Specific RNA Library Preparation Kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) was used for library construction followed by AMPure XP Beads size selection. The sequence was directly determined using Illumina's sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) technology. Sequencing data (FASTQ reads) were generated based on Illumina's basecalling program bcl2fastq (v2.20), which was used to convert BCL files from all Illumina sequencing platforms into FASTQ reads. Both adaptor clipping and sequence quality trimming were performed using Trimmomatic (v0.36) with a sliding window approach. For quality control checks on raw sequence data of each sample, the FastQC (v0.11.7) was utilized to assess the per base sequence quality and per sequence quality scores (Fig. S4). Among sequence data for 150 bp paired-end (a total of 24), no sequences were flagged as poor quality. Next, Hisat2 (v2.1.0) [17] was used for mapping sequencing reads to the mouse reference genome (GRCm38) and generating SAM files. We further performed Samtools (v1.10) to convert the SAM file to BAM format [18]. Finally, TPM values were calculated from filtered mapped reads using Stringtie (v2.1.3) with the default setting [19]. The processed RNA-seq data comprise three comparison groups, including 1) 16 h erinacine S versus 16 h DMSO control treatment, 2) 48 h erinacine S versus 48 h DMSO control treatment, and 3) 48 h versus 16 h erinacine S treatment. For each comparison group, the log2 (fold change) was evaluated using DEseq2 (v1.28.1) [20]. Based on the TPM values of 22,025 protein-coding genes, we defined that genes with log2 (fold change) ≥ 1 and ≤ −1 were considered highly up-regulated and down-regulated for each comparison group, respectively.

2.11. Gene set enrichment analysis

To examine and understand the mechanisms of erinacine S on neuronal regeneration, we used the approach of gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) [21] to reveal which pathways were significantly associated (FDR q-value ≤ 0.25 as suggested by GSEA) with the genes up-regulated in the dissociated cortical neurons treated with erinacine S for 16 or 48 h compared to the control. Given a collection of 328 pathways derived from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database [22] and the ranked list of gene expression changes resulting from the treatment of erinacine S for 16 (or 48) hours, GSEA tests whether the members of each pathway are randomly distributed along the list or clustered near the extremes, with the latter indicating that the pathway is regulated by the treatment. For the implementation of GSEA, we used the gene set as the permutation type, the Signal2Noise as the metric for ranking genes, 500 (or 15) as the max (or min) size of excluding larger (or smaller) sets, and the default setting of the other parameters.

2.12. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 with the indicated statistical methods.

3. Results

3.1. Erinacine S promotes neurite outgrowth

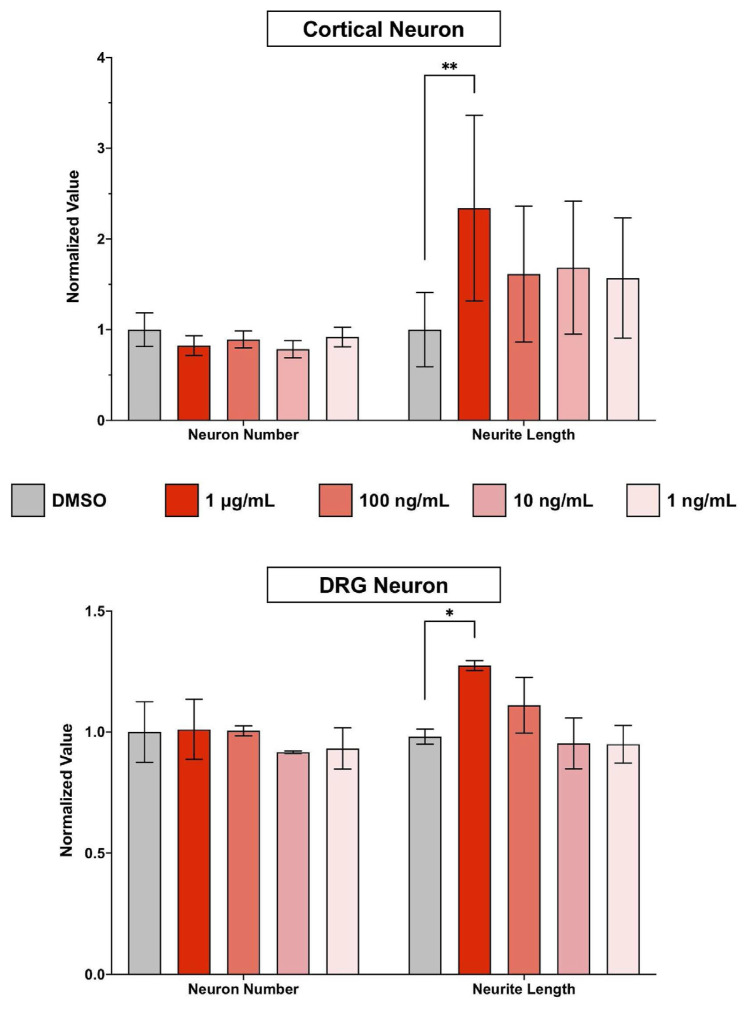

To assess the cellular effect of erinacine S on neurons, we first examined the cytotoxicity of erinacine S on dissociated neurons from the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Primary cortical neurons from mice and primary dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons from rats were used to represent CNS and PNS neurons, respectively. Erinacine S was applied to dissociated cultures of cortical or DRG neurons 4 h after plating the neurons and for a duration of 2 days. To eliminate the possibility of erinacine S-mediated pigment formation or toxicity caused by MTT assay itself [23], we utilized a microscopy-based cell viability assay [24]. After neurons were fixed and immunofluorescence stained with the antibody against neuron-specific β–III–tubulin, images of neurons were acquired using a fluorescence microscope and analyzed using a ImageJ-based software called NeurphologyJ [16]. NeurphologyJ has been shown to accurately and reliably quantify total neuron number and total neurite length in fluorescence images. The term neurite (instead of axon or dendrite) is used because axon or dendrite formation has not been completed in neurons cultured in vitro for 2 days [25]. Erinacine S exhibits low cytotoxicity in both CNS and PNS neurons across the concentration range from 1 ng/mL to 1 μg/mL (Fig. 1). In addition to the low cytotoxicity, a statistically significant effect on neurite outgrowth was observed in both CNS and PNS neurons (Fig. 1). This neurite outgrowth promoting effect of erinacine S can only be detected at the concentration of 1 μg/mL, and neurons from the CNS exhibit a more pronounced effect than those from the PNS.

Fig. 1.

The cytotoxic and neurite outgrowth effect of erinacine S on primary CNS and PNS neurons. 2DIV (2 days in vitro) primary cortical neurons (top) and primary DRG neurons (bottom) were treated with indicated concentrations of erinacine S for 48 h. Quantification of neuron number (left) and total neurite length per neuron (right) from 3 independent experiments. The bar graphs are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post-hoc analysis against the DMSO solvent control group.

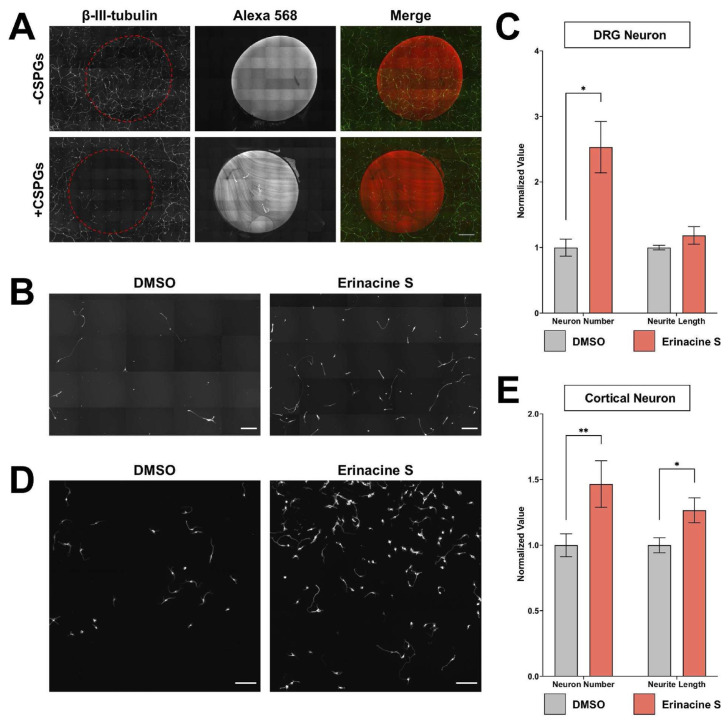

3.2. Erinacine S promotes regeneration in neurons on inhibitory substrate

Since neurite outgrowth is highly correlated with neuronal regeneration and many regeneration promoting genes have been identified through neurite outgrowth screens [26,27], the effect of erinacine S on neuronal regeneration was examined. We first set up an assay to examine CNS regeneration in the inhibitory environment. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) were utilized to generate this inhibitory environment by coating them onto the culturing surface. This is because CSPGs are known to inhibit axon regeneration in CNS injuries [28]. Since the dissociation process to obtain primary neurons causes the severing of neurites from neurons, combining this with CSPGs coating creates an environment mimicking spinal cord injuries. Although DRG neurons are considered PNS neurons, their axons bifurcate into two branches, one extends towards the peripheral tissue and the other extends into the spinal cord [29]. Regeneration is very limited when the central branch of the axon sustains an injury due to the inhibitory environment inside the spinal cord [30]. Dissociated DRG neurons were seeded on a CSPGs-coated surface and incubated for 2 days. A fluorescent dye-conjugated antibody was also included in CSPGs coating to help identify the inhibitory region (Fig. 2A). Consistent with the inhibitory effect of CSPGs, we observed a drastic reduction of DRG neuron number and axon length inside the coated area (Fig. 2A). This indicates CSPGs coating interferes with the attachment of neurons and impairs the extension of axons. Interestingly, the addition of 1 μg/mL erinacine S leads to a significant increase of DRG neuron number inside CSPGs-coated area (Fig. 2B and C). In addition to DRG neurons, we also examined the regenerative effect of erinacine S on cortical neurons cultured on CSPGs-coated surfaces. Consistent with the observation on DRG neurons, 1 μg/mL erinacine S significantly increases cortical neuron attachment on CSPGs. Furthermore, erinacine S significantly enhances the length of neurites (Fig. 2D and E). These results demonstrate that erinacine S can promote neuronal regeneration on inhibitory substrates mimicking the spinal cord injury.

Fig. 2.

Erinacine S promotes cortical neuron regeneration on inhibitory substrates. (A) Dissociated rat DRG neurons cultured on surface with or without CSPGs. Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated antibody was mixed with ddH2O (top) or CSPGs (bottom) to label the coated region. Neurons were immunofluorescence stained with the antibody against the neuron-specific β-III tubulin (green). The red dotted area indicates ddH2O or CSPGs-coated region. All images have the same scale and the scale bar represents 1 mm. (B) Representative images of dissociated rat DRG neurons cultured in the CSPGs-coated area and treated with 1 μg/mL erinacine S or DMSO solvent control. Neurons were immunofluorescence stained with the antibody against neuron-specific β-III tubulin. Both scale bars represent 300 μm. (C) Quantification of DRG neuron number (left) and total neurite length per neuron (right) from 4 independent experiments in CSPGs-coated regions. *p < 0.05, two-tailed Student's t-test. (D) Representative images of dissociated mouse cortical neurons cultured in the CSPGs-coated area and treated with 1 μg/mL erinacine S or DMSO solvent control. Neurons were immunofluorescence stained with the antibody against neuron-specific β-III tubulin. Both scale bars represent 100 μm. (E) Quantification of cortical neuron number (left) and total neurite length per neuron (right) from 4 independent experiments in CSPGs-coated regions. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, two-tailed Student's t-test.

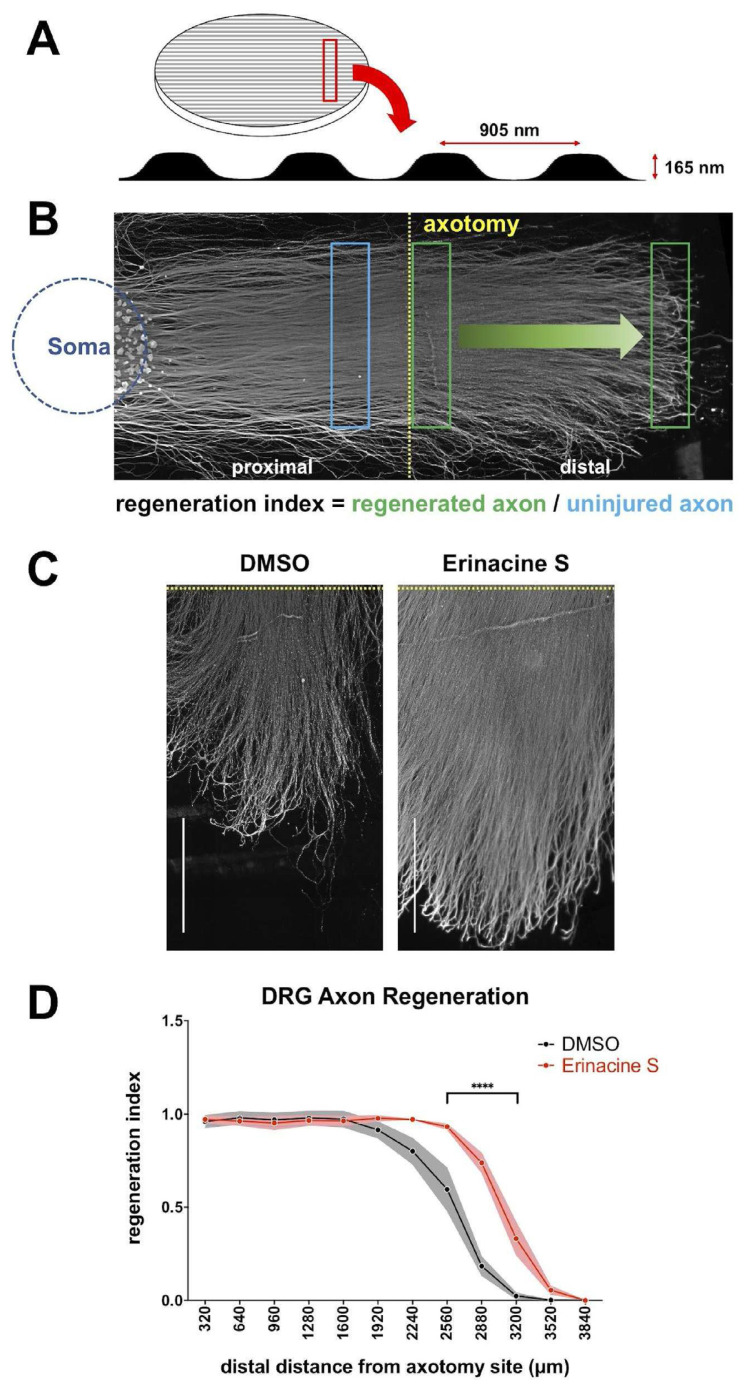

3.3. Erinacine S promotes axon regeneration in injured neurons

While the previous experiments demonstrate that erinacine S promotes regeneration after CNS injuries, whether erinacine S can enhance regeneration after PNS injuries is unknown. To answer this question, we utilized an axon regeneration assay using DRG neurons and a micropatterned surface. The biocompatible polymer ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) was used to generate an anisotropic surface resembling a linear grooved micropattern (Fig. 3A). This surface micropattern has previously been shown to guide DRG neuron axon outgrowth [15]. Instead of using CSPGs to mimic the spinal cord injury environment, DRG neurons were cultured in the absence of inhibitory substrates. After 7 days of culture, the physical severing of axons (axotomy) was conducted to create the injury condition. Injured DRG neurons were allowed to regenerate for 2 additional days before being fixed for analysis. Consistent with the previous observation [15], robust regeneration can be detected from the proximal stump (i.e. the axon region proximal to the soma from the axotomy site) while the distal stump degenerates (Fig. 3B). Similar to the outcome observed in CSPGs-coated environment, 1 μg/mL erinacine S significantly enhances the regeneration of DRG axons (Fig. 3C and D). This result shows that erinacine S can enhance neuronal regeneration in a setting mimicking the PNS injury.

Fig. 3.

Erinacine S promotes DRG axon regeneration after axotomy. (A) The schematic diagram of the micropatterned coverslip (left) and the surface profile of the micropattern (bottom). The pitch and depth of the surface micropattern are indicated. (B) The representative image of a 9DIV rat DRG drop culture on the micropatterned coverslip that has undergone axotomy. The blue circle indicates where DRG neuronal cell bodies are located and the yellow dotted line demarcates the axotomy site. The blue rectangle indicates the region from which signal of uninjured axons was obtained, and the green rectangles indicate the regions from which the signal of regenerated axons was obtained. (C) Representative images of regenerated DRG axons in the presence of 1 μg/mL erinacine S or DMSO solvent control. DRG axons were immunofluorescence stained with the antibody against neuron-specific β–III–tubulin. Dotted yellow lines demarcate the axotomy sites. Both scale bars represent 1 mm. (D) Quantification of the post-axotomy DRG axon regeneration in the presence of 1 μg/mL erinacine S or DMSO solvent control. The Y–axis represents the regeneration index and the X-axis represents the distance along the regenerating axons from the axotomy site. Dots and shaded areas represent mean ± s.e.m. from 3 independent experiments. ****p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak post-hoc analysis against the DMSO control group.

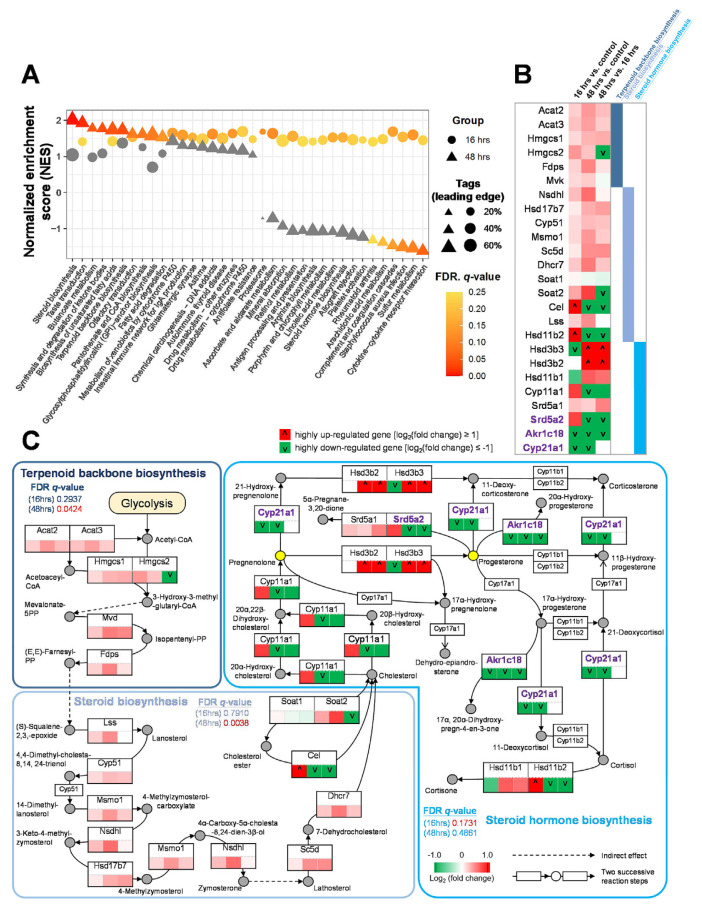

3.4. Erinacine S causes the accumulation of neurosteroids

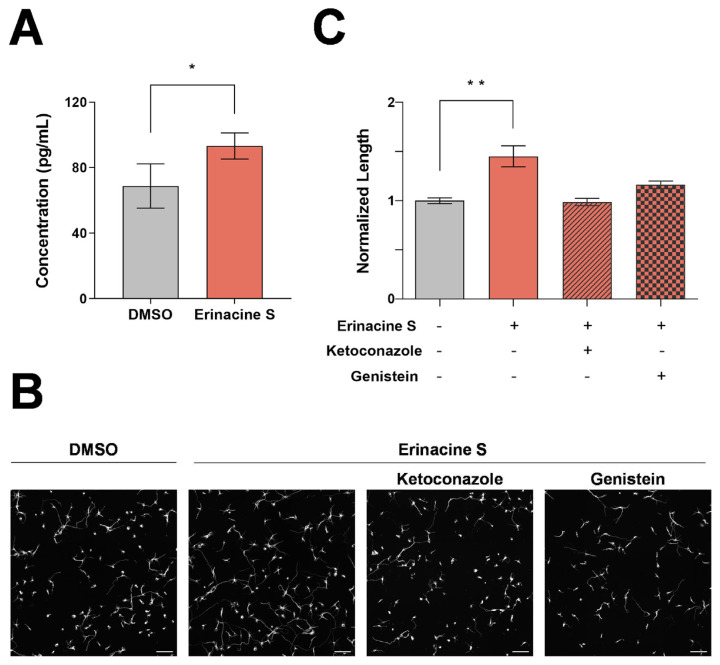

To understand the underlying mechanisms of erinacine S on neuronal regeneration, we utilized the next-generation sequencing technology (RNA-seq) to examine the transcriptomic changes in neurons treated with erinacine S. Primary cortical neurons were selected for this analysis because they showed a significant increase of neurite length when cultured on CSPGs and exposed to erinacine S (Fig. 2E). Using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) [21], we found that 36 enriched pathways displayed statistically significant enrichment (NES ≥0 and FDR q-value ≤ 0.25) on RNA-seq data of treatments for 16 (circle) or 48 (triangle) hours compared to corresponding DMSO control. Interestingly, pathways involved in the synthesis of neurosteroids (e.g. terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, steroid biosynthesis, and steroid hormone biosynthesis) were detected (Fig. 4A). To provide a concise representation of the proposed model for the accumulation of neurosteroids, we selected 25 representative genes that satisfy two criteria (Fig. 4B and Table S1): (1) choosing the genes located in the shortest path between the pathways of terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, steroid biosynthesis, and steroid hormone biosynthesis and (2) removing the genes with zero expression values of all samples in at least two comparison groups. On the one hand, genes associated with upstream pathways for the synthesis of neurosteroids were up-regulated in neurons treated with erinacine S compared with the control neurons (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, genes associated with the conversion of neurosteroids into other steroids [aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C18 (Akr1c18), steroid 21-monooxygenase (Cyp21a1), steroid 5 alpha-reductase 2 (Srd5a2); shown in purple] were down-regulated (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that erinacine S treatment induces the accumulation of neurosteroids, in particular pregnenolone and progesterone (Fig. 4C). To validate the this, two different approaches were utilized. In the first approach, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was employed to directly quantify the level of pregnenolone in primary cortical neurons. Using a competitive ELISA targeting pregnenolone, we detected a statistically significant increase of pregnenolone from the lysate of dissociated cortical neurons treated with erinacine S for 48 h (Fig. 5A). In the second approach, specific inhibitors for neurosteroidogenesis (i.e., small molecules that inhibit enzymes responsible for the biosynthesis of neurosteroids) were used. The rationale is that if the accumulation of pregnenolone and progesterone is responsible for the increase of neurite outgrowth seen in erinacine S-treated neurons (Fig. 1), blocking the biosynthesis of these neurosteroids will abolish the enhancement of neurite outgrowth produced by erinacine S. Ketoconazole (an inhibitor for cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme P450scc, encoded by Cyp11a1 gene) and genistein (an inhibitor for 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, encoded by Hsd3b2 and Hsd3b3 genes) were used to block the biosynthesis of pregnenolone and progesterone, respectively. Consistent with our prediction, blocking the biosynthesis of pregnenolone or progesterone eliminates erinacine S-mediated neurite outgrowth enhancement (Fig. 5B and C). Taken together, these results indicate that erinacine S causes the accumulation of neurosteroids in neurons and this accumulation is responsible for promoting the neurite outgrowth.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of the mechanisms of erinacine S causing the accumulation of neurosteroids in cortical neurons. (A) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of RNA-seq data of dissociated cortical neurons treated with erinacine S for 16 or 48 h using 328 KEGG mouse pathways. Among these pathways, 36 were identified as enriched (NES ≥0 and FDR q-value ≤ 0.25) based on RNA-seq data of treatments for 16 (circle) or 48 h (triangle) versus corresponding DMSO controls. The sizes of circles and triangles are proportional to the tags of leading edges, which are the percentages of gene hits before (for positive enrichment score) or after (for negative enrichment score) the peak in the running enrichment score. The pathways in gray were considered to have no significant changes (FDR q-values higher than 0.25 as suggested by GSEA). (B) Differential expression profiles of 25 representative genes in several neurosteroids-related pathways, including the terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, steroid biosynthesis, and steroid hormone biosynthesis. Among these pathways, 25 genes exhibit up- (red) or down-regulation (green) in cortical neurons upon the treatment of erinacine S. Cells in the first, second, and third column indicate the gene expression change comparing 16 h erinacine S and 16 h DMSO treatments, gene expression change comparing 48 h erinacine S and 48 h DMSO treatments, and gene expression change comparing 48 and 16 h erinacine S treatments, respectively. The genes with log2 (fold change) ≥ 1 and ≤ −1 were considered highly up-regulated and down-regulated ones, respectively. (C) Proposed model for the accumulation of neurosteroids through the pathways of terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, steroid biosynthesis, and steroid hormone biosynthesis in cortical neurons. For each gene, the expression change is indicated by the color scheme (red: up-regulated; green: down-regulated; white: no change). The row of 3 cells below each gene denotes: (left) 16 h erinacine S versus 16 h DMSO control treatment, (middle) 48 h erinacine S versus 48 h DMSO control treatment, and (right) 48 h versus 16 h erinacine S treatment. Many upstream genes responsible for the biosynthesis of neurosteroids are up-regulated, while several genes of enzymes (labeled in purple) involved in the conversion of neurosteroids are down-regulated upon the treatments of erinacine S. This synergistic effect leads to the accumulation of specific neurosteroids such as pregnenolone and progesterone (yellow circles).

Fig. 5.

Functional validation of erinacine S causing the accumulation of neurosteroids in cortical neurons. (A) Quantification of the pregnenolone concentration in lysates of 2DIV dissociated mouse cortical neurons from 3 independent experiments. The bar graph is expressed as mean ± s.e.m. *p < 0.05, one-tailed paired Student's t-test. (B) Representative images of 2DIV dissociated mouse cortical neurons treated with DMSO (left most), 1 μg/mL erinacine S (middle left), 1 μg/mL erinacine S and 0.5 μM ketoconazole (middle right), 1 μg/mL erinacine S and 25 μM genistein (right most). Neurons were immunofluorescence stained with the antibody against neuron-specific β-III tubulin. All scale bars represent 100 μm. (C) Quantification of total neurite length per neuron in 2DIV cortical neurons treated with the indicated compounds from 2 independent experiments. The bar graph is expressed as mean ± s.e.m. **p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post-hoc analysis against the DMSO solvent control group (gray bar).

4. Discussion

While it has been shown that H. erinaceus mycelium-derived erinacines possess various health benefits including neuroprotective effects against neurodegenerative diseases, yet the underlying cellular/molecular mechanisms remain elusive. In this study, we demonstrate that erinacine S promotes neurite outgrowth of primary cortical neurons and DRG neurons. In addition, erinacine S promotes the regeneration of neurites when cortical neurons were cultured on the inhibitory substrate CSPGs which builds up during CNS injuries. Furthermore, physically severed axons of DRG neurons exhibits enhanced regeneration when exposed to erinacine S. Using RNA-seq and bioinformatic analyses, erinacine S exposure leads to the accumulation of neurosteroids in cortical neurons. Taken together, these results indicate that the neuroprotective effects of erinacine S come from its ability to promotes neuronal regeneration in a cell autonomous fashion.

It has been shown that neurosteroids promote neurite outgrowth, protect neurons against apoptosis, and induce neurogenesis; and it has even been suggested that the decline of neurosteroids is correlated with the occurrence of neurodegenerative diseases [12]. Progesterone and its immediate precursor pregnenolone significantly enhance neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells [31] and SH-SY5Y cells [32]. Given that neurite outgrowth is the fundamental process that drives the extension of axons or dendrites toward their targets, our results and these observations suggest that neurosteroids may be the key molecules induced by erinacine S to promote neuronal regeneration.

In addition to their effect on neurite growth, neurosteroids also promote neuronal survival and myelination. Progesterone reduces apoptotic responses and promotes long-term recovery in rats suffering from traumatic brain injuries [33]. In addition to acting on neurons, progesterone also promotes myelin formation and repairment [34]. Furthermore, a significant reduction of the sulfate derivatives of pregnenolone has been observed in specific brain regions of Alzheimer's disease patients [35]. Taken together, these observations suggest that erinacine S plays a neuroprotective role in neurodegenerative diseases by the accumulation of neurosteroids besides enhancing the expression of neurotrophic factors.

Data availability

The accession number for RNA-seq data reported in this paper is GEO: GSE208121.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 110-2628-B-A49-001 and MOST 111-2636-B-A49-010) and “Center for Intelligent Drug Systems and Smart Bio-devices (IDS2B)” and “Smart Platform of Dynamic Systems Biology for Therapeutic Development ” from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education

Appendix

The chemical structure of erinacine S.

The expression level of two house-keeping genes is not altered when erinacine S was applied to the neuronal culture. The primers used to amplify beta-actin produce a PCR product 772 bp in length while those used to amplify GAPDH produce a PCR product 860 bp in length. The analysis on 2 independent experiments is shown.

The procedure for RNA-seq analysis used in this study.

Quality assessment of raw data for 150 bp paired-end (R1 and R2) RNA-seq. (A) Per base sequence quality. There are four groups of samples (a total of 12) from primary mouse cortical neurons used for RNA-seq analyses; each group contains 3 independent repeats (rep1-rep3), including 1) DMSO solvent control treatment for 16 h, 2) 1 μg/mL erinacine S treatment for 16 h, 3) DMSO solvent control treatment for 48 h, and 4) 1 μg/mL erinacine S treatment for 48 h. The red lines indicate the median value, and the blue lines represent the mean quality. The Y-axis represents the quality scores with calls of good quality fall in the green area, calls of reasonable quality in orange, and calls of poor quality in red. (B) Per sequence quality scores. The most frequently observed mean quality for all of our RNA-seq data is 36, indicating a universally good quality.

Table S1.

The expression profiles of 25 representative genes in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, steroid biosynthesis, and steroid hormone biosynthesis pathways.

| Gene name | Mean of erinacine S (16 h) | Mean of DMSO (16 h) | Mean of erinacine S (48 h) | Mean of DMSO (48 h) | log2FoldChange (erinacine 16 h/DMSO16 h) | log2FoldChange (erinacine 48 h/DMSO 48 h) | log2FoldChange (erinacine 48 h/erinacine 16 h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acat2 | 361.6090 | 316.2732 | 432.7321 | 327.7989 | 0.1933 | 0.4007 | 0.2590 |

| Acat3 | 60.5840 | 51.1709 | 69.7669 | 53.6660 | 0.2436 | 0.3785 | 0.2036 |

| Hmgcs1 | 1143.5020 | 1028.2884 | 1434.2570 | 1169.0247 | 0.1532 | 0.2950 | 0.3268 |

| Hmgcs2 | 0.0649 | 0.0488 | 0.0160 | 0.0136 | 0.4110 | 0.2355 | −2.0149 |

| Fdps | 778.6338 | 688.5077 | 846.9608 | 607.8225 | 0.1775 | 0.4786 | 0.1214 |

| Mvk | 132.1852 | 119.0552 | 127.3504 | 110.7471 | 0.1509 | 0.2015 | −0.0538 |

| Nsdhl | 144.2580 | 120.0450 | 149.0973 | 100.0962 | 0.2651 | 0.5749 | 0.0476 |

| Hsd17b7 | 28.6533 | 27.0347 | 37.3982 | 29.8658 | 0.0839 | 0.3245 | 0.3843 |

| Cyp51 | 282.8622 | 255.7440 | 334.1518 | 277.3857 | 0.1454 | 0.2686 | 0.2404 |

| Msmo1 | 208.4856 | 186.7944 | 240.3518 | 181.1271 | 0.1585 | 0.4081 | 0.2052 |

| Sc5d | 88.6097 | 83.0326 | 120.8936 | 88.8171 | 0.0938 | 0.4448 | 0.4482 |

| Dhcr7 | 160.8497 | 137.9424 | 188.6604 | 131.6858 | 0.2216 | 0.5187 | 0.2301 |

| Soat1 | 4.8730 | 4.7322 | 4.5008 | 4.7582 | 0.0423 | −0.0802 | −0.1146 |

| Soat2 | 0.6062 | 0.4746 | 0.2589 | 0.1537 | 0.3531 | 0.7528 | −1.2272 |

| Cel | 0.0664 | 0.0106 | 0.0001 | 0.0078 | 2.6502 | −6.2816 | −9.3744 |

| Lss | 131.1258 | 114.7167 | 130.7294 | 95.8294 | 0.1929 | 0.4480 | −0.0044 |

| Hsd11b2 | 0.1506 | 0.0635 | 0.0387 | 0.1238 | 1.2462 | −1.6798 | −1.9625 |

| Hsd3b3 | 0.0001 | 0.0033 | 0.0091 | 0.0001 | −5.0522 | 6.5005 | 6.5005 |

| Hsd3b2 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0061 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 5.9384 | 5.9384 |

| Hsd11b1 | 0.5163 | 0.8529 | 0.7598 | 0.4879 | −0.7241 | 0.6391 | 0.5574 |

| Cyp11a1 | 0.1401 | 0.0826 | 0.0702 | 0.1764 | 0.7634 | −1.3299 | −0.9980 |

| Srd5a1 | 12.0653 | 10.1539 | 17.0068 | 14.9217 | 0.2488 | 0.1887 | 0.4952 |

| Srd5a2 | 0.1948 | 0.1165 | 0.0001 | 0.0628 | 0.7420 | −9.2936 | −10.9279 |

| Akr1c18 | 0.0414 | 0.1358 | 0.0156 | 0.0497 | −1.7133 | −1.6746 | −1.4113 |

| Cyp21a1 | 0.0001 | 0.0163 | 0.0001 | 0.0379 | −7.3526 | −8.5665 | 0.0000 |

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 110-2628-B-A49-001 and MOST 111-2636-B-A49-010)

Footnotes

Author contributions

CYL, HHC, SJH performed the bioinformatics analyses. YJC prepared the samples for RNA-seq. YJC and CHH performed and analyzed the neuroregeneration on CSPGs experiments. YHL performed and analyzed the axon regeneration experiments. CTH and HCC performed and analyzed the neurite outgrowth experiments. PTC and THK performed and analyzed the neurosteroidogenesis inhibitor assays and pregnenolone ELISA quantification. CCC purified erinacine S. EH conceived and designed the study. EH and CYL wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The purified erinacine S was provided by the Grape King Bio who partially provided the funding for this research.

References

- 1. Friedman M. Chemistry, nutrition, and health-promoting properties of Hericium erinaceus (Lion's Mane) Mushroom Fruiting Bodies and Mycelia and Their Bioactive Compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:7108–23. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li IC, Lee LY, Tzeng TT, Chen WP, Chen YP, Shiao YJ, et al. Neurohealth Properties of Hericium erinaceus Mycelia Enriched with Erinacines. Behav Neurol. 2018;2018:5802634. doi: 10.1155/2018/5802634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen CC, Tzeng TT, Chen CC, Ni CL, Lee LY, Chen WP, et al. Erinacine S, a Rare Sesterterpene from the Mycelia of Hericium erinaceus. J Nat Prod. 2016;79:438–41. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li IC, Chang HH, Lin CH, Chen WP, Lu TH, Lee LY, et al. Prevention of Early Alzheimer's Disease by Erinacine A-Enriched Hericium erinaceus Mycelia Pilot Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:155. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kawagishi H, Shimada A, Hosokawa S, Mori H, Sakamoto H, Ishiguro Y, et al. Erinacines E, F, and G, stimulators of nerve growth factor (NGF)-synthesis, from the mycelia of Hericium erinaceum. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:7399–402. In English. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kawagishi H, Shimada A, Shirai R, Okamoto K, Ojima F, Sakamoto H, et al. Erinacines A, B and C, strong stimulators of nerve growth factor (NGF)-synthesis, from the mycelia of Hericium erinaceum. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:1569–72. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kawagishi H, Simada A, Shizuki K, Mori H, Okamoto K, Sakamoto H, et al. Erinacine D, a stimulator of NGF-synthesis, from the mycelia of Hericium erinaceum. Heterocycl Commun. 1996;2:51–4. In English. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee EW, Shizuki K, Hosokawa S, Suzuki M, Suganuma H, Inakuma T, et al. Two novel diterpenoids, erinacines H and I from the mycelia of Hericium erinaceum. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2000;64:2402–5. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shimbo M, Kawagishi H, Yokogoshi H. Erinacine A increases catecholamine and nerve growth factor content in the central nervous system of rats. Nutr Res. 2005;25:617–23. In English. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tsai-Teng T, Chin-Chu C, Li-Ya L, Wan-Ping C, Chung-Kuang L, Chien-Chang S, et al. Erinacine A-enriched Hericium erinaceus mycelium ameliorates Alzheimer's disease-related pathologies in APPswe/PS1dE9 transgenic mice. J Biomed Sci. 2016;23:49. doi: 10.1186/s12929-016-0266-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tzeng TT, Chen CC, Chen CC, Tsay HJ, Lee LY, Chen WP, et al. The Cyanthin Diterpenoid and Sesterterpene Constituents of Hericium erinaceus Mycelium Ameliorate Alzheimer's Disease-Related Pathologies in APP/PS1 Transgenic Mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19 doi: 10.3390/ijms19020598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Charalampopoulos I, Remboutsika E, Margioris AN, Gravanis A. Neurosteroids as modulators of neurogenesis and neuronal survival. Trends Endocrinol Metabol. 2008;19:300–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang YA, Hsu CH, Chiu HC, Hsi PY, Ho CT, Lo WL, et al. Actin waves transport RanGTP to the neurite tip to regulate non-centrosomal microtubules in neurons. J Cell Sci. 2020;133(9):jcs241992. doi: 10.1242/jcs.241992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang YA, Kao JW, Tseng DT, Chen WS, Chiang MH, Hwang E. Microtubule-Associated Type II Protein Kinase A Is Important for Neurite Elongation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang YA, Ho CT, Lin YH, Lee CJ, Ho SM, Li MC, et al. Nanoimprinted Anisotropic Topography Preferentially Guides Axons and Enhances Nerve Regeneration. Macromol Biosci. 2018:e1800335. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201800335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ho SY, Chao CY, Huang HL, Chiu TW, Charoenkwan P, Hwang E. NeurphologyJ: an automatic neuronal morphology quantification method and its application in pharmacological discovery. BMC Bioinf. 2011;12:230. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:907–15. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, Marshall J, Ohan V, Pollard MO, et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience. 2021:10. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang TC, Mendell JT, Salzberg SL. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:290–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Sato Y, Ishiguro-Watanabe M, Tanabe M. KEGG: integrating viruses and cellular organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D545–51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hertel C, Hauser N, Schubenel R, Seilheimer B, Kemp JA. Beta-amyloid-induced cell toxicity: enhancement of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide-dependent cell death. J Neurochem. 1996;67:272–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67010272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang YA, Kao CW, Liu KK, Huang HS, Chiang MH, Soo CR, et al. The effect of fluorescent nanodiamonds on neuronal survival and morphogenesis. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6919. doi: 10.1038/srep06919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaech S, Banker G. Culturing hippocampal neurons. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2406–15. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.356. In eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chandran V, Coppola G, Nawabi H, Omura T, Versano R, Huebner EA, et al. A Systems-Level Analysis of the Peripheral Nerve Intrinsic Axonal Growth Program. Neuron. 2016;89:956–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moore DL, Blackmore MG, Hu Y, Kaestner KH, Bixby JL, Lemmon VP, et al. KLF family members regulate intrinsic axon regeneration ability. Science. 2009;326:298–301. doi: 10.1126/science.1175737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yiu G, He Z. Glial inhibition of CNS axon regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:617–27. doi: 10.1038/nrn1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nascimento AI, Mar FM, Sousa MM. The intriguing nature of dorsal root ganglion neurons: Linking structure with polarity and function. Prog Neurobiol. 2018;168:86–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Neumann S, Woolf CJ. Regeneration of dorsal column fibers into and beyond the lesion site following adult spinal cord injury. Neuron. 1999;23:83–91. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80755-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fontaine-Lenoir V, Chambraud B, Fellous A, David S, Duchossoy Y, Baulieu EE, et al. Microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) is a neurosteroid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4711–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600113103. In eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kasubuchi M, Watanabe K, Hirano K, Inoue D, Li X, Terasawa K, et al. Membrane progesterone receptor beta (mPRbeta/Paqr8) promotes progesterone-dependent neurite outgrowth in PC12 neuronal cells via non-G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5168. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05423-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Djebaili M, Guo Q, Pettus EH, Hoffman SW, Stein DG. The neurosteroids progesterone and allopregnanolone reduce cell death, gliosis, and functional deficits after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:106–18. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schumacher M, Sitruk-Ware R, De Nicola AF. Progesterone and progestins: neuroprotection and myelin repair. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:740–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weill-Engerer S, David JP, Sazdovitch V, Liere P, Eychenne B, Pianos A, et al. Neurosteroid quantification in human brain regions: comparison between Alzheimer's and nondemented patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:5138–43. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The chemical structure of erinacine S.

The expression level of two house-keeping genes is not altered when erinacine S was applied to the neuronal culture. The primers used to amplify beta-actin produce a PCR product 772 bp in length while those used to amplify GAPDH produce a PCR product 860 bp in length. The analysis on 2 independent experiments is shown.

The procedure for RNA-seq analysis used in this study.

Quality assessment of raw data for 150 bp paired-end (R1 and R2) RNA-seq. (A) Per base sequence quality. There are four groups of samples (a total of 12) from primary mouse cortical neurons used for RNA-seq analyses; each group contains 3 independent repeats (rep1-rep3), including 1) DMSO solvent control treatment for 16 h, 2) 1 μg/mL erinacine S treatment for 16 h, 3) DMSO solvent control treatment for 48 h, and 4) 1 μg/mL erinacine S treatment for 48 h. The red lines indicate the median value, and the blue lines represent the mean quality. The Y-axis represents the quality scores with calls of good quality fall in the green area, calls of reasonable quality in orange, and calls of poor quality in red. (B) Per sequence quality scores. The most frequently observed mean quality for all of our RNA-seq data is 36, indicating a universally good quality.

Table S1.

The expression profiles of 25 representative genes in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, steroid biosynthesis, and steroid hormone biosynthesis pathways.

| Gene name | Mean of erinacine S (16 h) | Mean of DMSO (16 h) | Mean of erinacine S (48 h) | Mean of DMSO (48 h) | log2FoldChange (erinacine 16 h/DMSO16 h) | log2FoldChange (erinacine 48 h/DMSO 48 h) | log2FoldChange (erinacine 48 h/erinacine 16 h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acat2 | 361.6090 | 316.2732 | 432.7321 | 327.7989 | 0.1933 | 0.4007 | 0.2590 |

| Acat3 | 60.5840 | 51.1709 | 69.7669 | 53.6660 | 0.2436 | 0.3785 | 0.2036 |

| Hmgcs1 | 1143.5020 | 1028.2884 | 1434.2570 | 1169.0247 | 0.1532 | 0.2950 | 0.3268 |

| Hmgcs2 | 0.0649 | 0.0488 | 0.0160 | 0.0136 | 0.4110 | 0.2355 | −2.0149 |

| Fdps | 778.6338 | 688.5077 | 846.9608 | 607.8225 | 0.1775 | 0.4786 | 0.1214 |

| Mvk | 132.1852 | 119.0552 | 127.3504 | 110.7471 | 0.1509 | 0.2015 | −0.0538 |

| Nsdhl | 144.2580 | 120.0450 | 149.0973 | 100.0962 | 0.2651 | 0.5749 | 0.0476 |

| Hsd17b7 | 28.6533 | 27.0347 | 37.3982 | 29.8658 | 0.0839 | 0.3245 | 0.3843 |

| Cyp51 | 282.8622 | 255.7440 | 334.1518 | 277.3857 | 0.1454 | 0.2686 | 0.2404 |

| Msmo1 | 208.4856 | 186.7944 | 240.3518 | 181.1271 | 0.1585 | 0.4081 | 0.2052 |

| Sc5d | 88.6097 | 83.0326 | 120.8936 | 88.8171 | 0.0938 | 0.4448 | 0.4482 |

| Dhcr7 | 160.8497 | 137.9424 | 188.6604 | 131.6858 | 0.2216 | 0.5187 | 0.2301 |

| Soat1 | 4.8730 | 4.7322 | 4.5008 | 4.7582 | 0.0423 | −0.0802 | −0.1146 |

| Soat2 | 0.6062 | 0.4746 | 0.2589 | 0.1537 | 0.3531 | 0.7528 | −1.2272 |

| Cel | 0.0664 | 0.0106 | 0.0001 | 0.0078 | 2.6502 | −6.2816 | −9.3744 |

| Lss | 131.1258 | 114.7167 | 130.7294 | 95.8294 | 0.1929 | 0.4480 | −0.0044 |

| Hsd11b2 | 0.1506 | 0.0635 | 0.0387 | 0.1238 | 1.2462 | −1.6798 | −1.9625 |

| Hsd3b3 | 0.0001 | 0.0033 | 0.0091 | 0.0001 | −5.0522 | 6.5005 | 6.5005 |

| Hsd3b2 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0061 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 5.9384 | 5.9384 |

| Hsd11b1 | 0.5163 | 0.8529 | 0.7598 | 0.4879 | −0.7241 | 0.6391 | 0.5574 |

| Cyp11a1 | 0.1401 | 0.0826 | 0.0702 | 0.1764 | 0.7634 | −1.3299 | −0.9980 |

| Srd5a1 | 12.0653 | 10.1539 | 17.0068 | 14.9217 | 0.2488 | 0.1887 | 0.4952 |

| Srd5a2 | 0.1948 | 0.1165 | 0.0001 | 0.0628 | 0.7420 | −9.2936 | −10.9279 |

| Akr1c18 | 0.0414 | 0.1358 | 0.0156 | 0.0497 | −1.7133 | −1.6746 | −1.4113 |

| Cyp21a1 | 0.0001 | 0.0163 | 0.0001 | 0.0379 | −7.3526 | −8.5665 | 0.0000 |

Data Availability Statement

The accession number for RNA-seq data reported in this paper is GEO: GSE208121.