Abstract

The objective of this systematic review was to investigate the association between polymorphisms in the progesterone receptor gene (PGR) and breast cancer risk. A search of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases was performed in November 2021. Study characteristics, minor allele frequencies, genotype frequencies, and odds ratios were extracted. Forty studies met the eligibility criteria and included 75 032 cases and 89 425 controls. Of the 84 PGR polymorphisms reported, 7 variants were associated with breast cancer risk in at least 1 study. These polymorphisms included an Alu insertion (intron 7) and rs1042838 (Val660Leu), also known as PROGINS. Other variants found to be associated with breast cancer risk included rs3740753 (Ser344Thr), rs10895068 (+331G/A), rs590688 (intron 2), rs1824128 (intron 3), and rs10895054 (intron 6). Increased risk of breast cancer was associated with rs1042838 (Val660Leu) in 2 studies, rs1824128 (intron 3) in 1 study, and rs10895054 (intron 6) in 1 study. The variant rs3740753 (Ser344Thr) was associated with decreased risk of breast cancer in 1 study. Mixed results were reported for rs590688 (intron 2), rs10895068 (+331G/A), and the Alu insertion. In a pooled analysis, the Alu insertion, rs1042838 (Val660Leu), rs3740753 (Ser344Thr), and rs10895068 (+331G/A) were not associated with breast cancer risk. Factors reported to contribute to differences in breast cancer risk associated with PGR polymorphisms included age, ethnicity, obesity, and postmenopausal hormone therapy use. PGR polymorphisms may have a small contribution to breast cancer risk in certain populations, but this is not conclusive with studies finding no association in larger, mixed populations.

Keywords: breast cancer, single nucleotide polymorphism, progesterone receptor, PROGINS haplotype, Alu insertion, +331G/A

The steroid hormones estrogen and progesterone are important for normal physiological development and function. Estrogen and progesterone are necessary for the development and maintenance of female reproductive tissues including the uterus, ovaries, and mammary glands. In normal breast development and during pregnancy, progesterone is necessary for ductal side-branching and lobuloalveolar development, respectively (1, 2).

Progesterone exerts its physiological functions predominately by binding to the ligand-activated transcription factor, progesterone receptor (PR), which then regulates transcription of target genes (3). The progesterone receptor gene (PGR) is located on chromosome 11q22.1 and has 8 exons and 7 introns (4-6). Separate promoters are utilized to encode for 2 predominant protein isoforms, PR-A (94 kDa) and PR-B (114 kDa) (7, 8). The isoforms are structurally identical except for an additional 164 amino acids found at the N-terminus of PR-B (7). Generally, PR-B is a stronger activator of transcription in response to progesterone than PR-A (9-11). While there are genes regulated by both isoforms, many progesterone-regulated target genes are largely controlled by 1 isoform or the other, predominately PR-B (12). While PR-B is a potent transcriptional activator, PR-A is a repressor of estrogen receptor (ER) and PR-B (13).

Several studies have elucidated the role each PR isoform plays in mammary development and how alterations in the PR-A:PR-B ratio affects normal mammary physiology. PR knockout mouse models that lack both PR isoforms have diminished mammary gland development (14). When PR-A was selectively deleted, PR-B was sufficient to induce normal mammary cell proliferation and differentiation (15). However, selective deletion of PR-B resulted in significantly decreased pregnancy-associated ductal and alveolar epithelial cell proliferation (16). In transgenic mice with increased PR-B expression the mammary glands had inappropriate alveolar growth, a limited capacity for mammary ductal growth, and limited lateral ductal branching (17). Conversely, mammary glands in transgenic mice with increased PR-A expression had ductal hyperplasia, extensive lateral branching, decreased cell–cell adhesion, and disruption in the organization of the basement membrane (18). The latter 2 findings are characteristics of invasiveness of mammary epithelial cells.

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women. In the United States, it is estimated that 287 850 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer and 43 250 women will die from the disease in 2022 (19). Hormonal-based breast cancer risk factors include early age at menarche, nulliparity, late age at menopause, and obesity among postmenopausal women, which are thought to increase risk through exposure to high lifetime levels of estrogen (20, 21). Estrogen mediates its effect by binding to ER alpha, which then promotes gene transcription and ultimately cell proliferation. Endocrine therapies for breast cancer target the estrogen signaling pathway by directly inhibiting or degrading ER protein (tamoxifen, fulvestrant) or by reducing estrogen production (aromatase inhibitors) (22). Tamoxifen, raloxifene, and aromatase inhibitors are endocrine therapy agents that can also be used as chemoprevention for women with elevated lifetime of breast cancer as a risk reduction strategy (23).

In contrast, evidence is less clear regarding the role of progesterone in breast cancer development; however, epidemiologic studies suggest that progesterone may also be involved (24). These studies have shown that combination estrogen and synthetic progestin hormone therapy increases the risk for breast cancer in postmenopausal women, whereas there is less risk from estrogen-only hormone therapy (25-27). Additionally, elevated serum progesterone has been shown to be associated with increased breast cancer risk for postmenopausal women (28), but not for premenopausal women (29).

Progesterone's role in breast cancer development has been theorized, but has not been clearly defined. One theory centers on changes in the relative expression of PR-A and PR-B. While PR-A and PR-B protein are coexpressed at comparable levels in normal breast tissue, this ratio is altered as an early event in the development of breast cancer and can impact patient prognosis and hormonal responsiveness (30-35). Therefore, it has been hypothesized that polymorphisms in PGR that alter protein expression and/or function of PR isoforms may influence the risk for breast cancer. The objective of this systematic review is to provide an updated summary of published studies investigating the association between polymorphisms in PGR and breast cancer risk.

Materials and Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Published retrospective or prospective observational studies investigating the association of PGR polymorphisms and risk of breast cancer diagnosis were eligible for inclusion in this review. Case–control and cohort study designs were eligible. No publication date restrictions were used. Only full-text articles published in English in peer-reviewed journals were included. Unrefereed preprint articles were not eligible for inclusion. Duplicated studies, abstracts, meta-analyses, and reviews were excluded. Studies were grouped for analysis according to the specific PGR polymorphism(s) investigated in each article.

Information Sources

Studies were identified by searching PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science Core Collection. The most recent search was performed on November 13, 2021. Reference lists from the eligible articles were reviewed to identify any additional studies. Reference lists from relevant meta-analyses and review articles were also screened.

Search Strategy

For the PubMed search, the medical subject headings “breast neoplasms/genetics,” “polymorphism, single nucleotide,” and “receptors, progesterone/genetics” were used. For the Scopus and Web of Science searches, the terms “PGR,” “polymorphism,” “breast cancer,” and “risk” were used.

Selection Process

One author performed the initial assessment for inclusion by screening the titles and abstracts and using the full-text article to confirm eligibility. The relevant articles were then independently reviewed by the other 2 authors. Final decision for inclusion was reached by consensus of all authors. No automation tools were used in the selection process.

Data Collection Process

One author performed the data collection using a structured electronic data collection form and 2 authors independently reviewed the accuracy and completeness of the extracted data. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between authors. No automation tools were used in the data collection process.

Data Items

The following variables were extracted from each study: first author's name, publication year, publication journal, country where the study was performed, ethnicity of participants, study design, number of cases and controls, ages of cases and controls, PGR polymorphism(s), allele frequencies, genotype frequencies, odds ratios (OR), and 95% CI.

Effect Measures

OR was the primary measure of the strength of association between an individual PGR variant and breast cancer.

Synthesis Methods

Study characteristics and evaluated polymorphisms are tabulated. Polymorphisms and their association with breast cancer risk are summarized as a narrative synthesis of the findings from the included studies. For variants investigated in at least 4 studies, a random effects model was used to pool the effect sizes across studies with the dominant genetic model (heterozygote + rare minor allele homozygote vs major allele homozygotes). Studies that did not report the individual genotypes or genotype frequencies for cases and controls were excluded from the pooled analysis.

Statistical software used was NCSS 2019, version 19.0.9 (NCSS, LLC, Kaysville, UT). Relevant meta-analyses published for the polymorphisms identified in this systematic review are also summarized in the “Discussion”.

Results

Study Selection

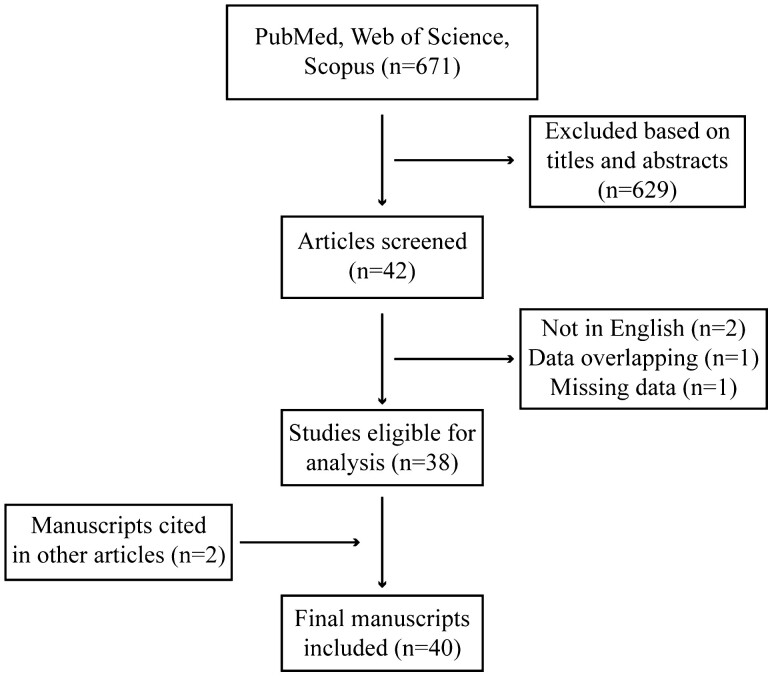

The literature search yielded 671 records (Fig. 1). A final number of 40 studies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (36-75). Non-English publications by Jin et al and Linhares et al were excluded (76, 77). The study reported by De Vivo et al (78) was excluded because that data set was subsequently reanalyzed with additional cases and controls in the report by Huggins et al (56). Gold et al were excluded since the allele frequencies, genotype frequencies, and ORs for the PGR polymorphisms were not included in the publication (79). Rockwell et al were excluded because the study examined the correlation between the frequency of PGR variants and breast cancer incidence across several global populations and did not include genotype frequencies for breast cancer cases and controls within the populations (80). Hertz et al were excluded since the study analyzed the association between PGR variants and PR mRNA and protein expression in patients with hormone receptor positive breast cancer and did not include an analysis of breast cancer risk associated with PGR variants (81). Giacomazzi et al were excluded since the study examined the relationship between PGR polymorphisms and mammographic breast density and body mass index in only women without breast cancer (82). Likewise, Chambo et al were excluded since the study investigated the association of a PGR polymorphism with mammographic breast density in only women without breast cancer (83). Two of the 40 total included studies were identified separate from the electronic literature search by reviewing the included studies from meta-analyses performed by Qi et al (84) and Yao et al (85), which both used Embase in addition to PubMed and Web of Science. No additional studies were identified from other relevant meta-analyses (86-89), systematic reviews (90) or from the review articles published by Peng et al (91) and Jahandoost et al (92).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram demonstrating the study selection process for this systematic review.

Study Characteristics

Key characteristics of the 40 included studies are summarized in Table 1. The publication dates ranged from 1995 to 2022. All studies were retrospective case–control in design. The studies included a total of 75 032 cases (median 564, range 68-23 129) and 89 425 controls (median 679.5, range 33-27 507). The ages for cases ranged from 20 to 88 years old. The ages for controls ranged from 20 to 86 years old.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in this systematic review

| First author, year | Country | Cases (n) | Controls (n) | PGR polymorphisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbas, 2010 (37) | Germany | 3149 | 5489 | rs518162, rs10895068, rs3740753, rs1379130, rs1042838, Alu insertion |

| Albalawi, 2020 (38) | Saudi Arabia | 100 | 100 | Alu insertion |

| The Breast Cancer Association Consortium, 2006 (36) | Breast Cancer Association Consortium (international) | 7593 | 8187 | rs1042838 |

| Canzian, 2010 (39) | United States and Europe | 6292 | 8135 | rs481883, rs1545611, rs1870019, rs1824125, rs473409, rs608995, rs561650, rs529216, rs545835, rs1042838, rs1824128, rs660541, rs477151, rs559700, rs516693, rs508533, rs601040, rs572483, rs543215, rs613120, rs565186, rs529359, rs481775, rs3740753, rs10895068, rs499590, rs474320, rs568157 |

| Clendenen, 2013 (40) | United States and Sweden | 1164 | 2111 | rs1042838 |

| Delort, 2010 (41) | France | 911 | 1000 | rs10895068 |

| De Vivo, 2004 (42) | United States | 1323 | 1854 | rs1042838 |

| Diergaarde, 2008 (43) | United States | 324 | 651 | rs1042838, rs10895068 |

| Donaldson, 2002 (44) | United States | 84 | 141 | Alu Insertion |

| Fabjani, 2002 (45) | Austria | 155 | 106 | rs1042838, rs1042839 |

| Feigelson, 2004 (46) | United States | 479 | 494 | rs10895068 |

| Fernandez, 2006 (47) | Spain | 550 | 564 | rs10895068, rs484389, rs545835, rs1042838 |

| Gabriel, 2013 (48) | United States | 487 | 843 | rs1042839, rs10895054, rs11224580, rs11571271, rs1379131, rs471767, rs492457, rs506487, rs507141, rs518382, rs537681, rs538915, rs553272, rs590688, rs601040, rs635984, rs653752, rs660149, rs7116336, rs1042838 |

| Gallegos-Arreola, 2015 (49) | Mexico | 481 | 209 | Alu Insertion |

| Garrett, 1995 (50) | Ireland | 187 | 90 | Alu Insertion |

| Gaudet, 2009 (51) | Breast Cancer Association Consortium (international) | 23 129 | 27 507 | rs1042838 |

| Ghali, 2020 (52) | Tunisia | 183 | 222 | rs471767, rs578029, rs1042838, rs590688, rs3740753, rs10895068, rs608995, rs1942836 |

| Govindan, 2007 (53) | India | 157 | 108 | Alu Insertion |

| Haddad, 2015 (54) | United States | 3663 | 4687 | rs11571215, rs11571247, rs2124761 |

| Harlid, 2011 (55) | Sweden, Iceland, Poland | 3211 | 4223 | rs529359 |

| Huggins, 2006 (56) | United States | 1322 | 1953 | rs10895068 |

| Jakubowska, 2010 (57) | Poland | 319 | 290 | Alu Insertion, rs10895068 |

| Johnatty, 2008 (58) | Australia | 1847 | 833 | rs518162, rs10895068, rs1042838, rs1042839, rs500760 |

| Kotsopoulos, 2009 (59) | United States | 1664 | 2391 | rs10895068 |

| Lancaster, 1998 (60) | United States | 68 | 101 | Alu Insertion |

| Manolitsas, 1997 (61) | England | 292 | 220 | Alu Insertion |

| Nyante, 2015 (62) | United States | 1972 | 1776 | rs1824128, rs11224575, rs11224579, rs10895068, rs11224565, rs11224566, rs11224570, rs11224590, rs11224591, rs11571247, rs2124761, rs492827, rs495997, rs501732, rs503602, rs538915, rs543936, rs546763, rs548668, rs555653, rs578029, rs596223, rs653752, rs660149, rs679275, rs693765 |

| Pearce, 2005a (63) | United States | 1715 | 2505 | rs474320, rs3740753, Hcv3182868, rs1042838, rs608995, rs10895068 |

| Pooley, 2006 (64) | England | 4647 | 4564 | rs10895068, rs506487, rs566351, rs11571171, rs578938, rs7116336, rs660149, rs1042838, rs492457, rs500760 |

| Ralph, 2007 (65) | United States | 1667 | 3333 | rs1042838, rs10895068 |

| Rebbeck, 2007 (66) | United States | 522 | 708 | rs10895068 |

| Reding, 2009 (67) | United States | 1296 | 1055 | rs10895068, rs1042838, rs500760, rs1042839, rs3740753, rs11224552, rs484389, rs558959, rs492457, rs543936, rs635984, rs503602, rs516693, rs529359, rs542384, rs11224589, rs506487, rs948516, rs521488 |

| Romano, 2006 (68) | Germany | 569 | 484 | rs10895068, rs1042838 |

| Romano, 2007 (69) | Netherlands | 187 | 33 | rs10895068, rs1042838 |

| Runnebaum, 2001 (70) | United States and Canada | 392 | 249 | Alu Insertion |

| Sadia, 2022 (71) | Pakistan | 100 | 115 | rs10895068, rs1042838 |

| Sangrajrang, 2009 (72) | Thailand | 570 | 497 | rs481883, rs578938, rs566351 |

| Spurdle, 2002 (73) | Australia | 1452 | 793 | rs1042838 |

| Surekha, 2009 (74) | India | 250 | 250 | Alu Insertion |

| Wang-Gohrke, 2000 (75) | Germany | 559 | 554 | Alu Insertion |

Remaining 48 PGR SNPs were not available online (63).

There were 14 publications with study populations solely from the United States (42-44, 46, 48, 54, 56, 59, 60, 62, 63, 65-67). Twenty-six publications were from international sources of 1 or more countries (36-41, 45, 47, 49-53, 55, 57, 58, 61, 64, 68-75). The representative countries are detailed in Table 1.

Study participant characteristics were reported with variable detail regarding race or ethnicity. Many publications did not specify race or ethnicity of the study population (37, 38, 41, 45, 47, 49, 50, 52, 55, 57, 61, 69, 71, 72, 74). For most publications, the study population was predominately or entirely Caucasian (36, 39, 40, 42, 43, 46, 51, 56, 58-60, 65-68, 70, 73, 75) or of Anglo-Saxon ancestry (64). All cases from 1 publication were Asian Indian (53). Three publications (39, 51, 63) included participants from the Hawaii and Los Angeles Multiethnic Cohort Study, which consists of African American, Latino, Japanese American, Native Hawaiian, and White individuals (93). One publication focused on breast cancer risk in African American women (54). Three publications used diverse study populations such that subgroup analyses of breast cancer risk for African American women were possible (44, 48, 62).

Results of Individual Studies

The list of PGR variants and corresponding minor allele frequencies, genotype frequencies, and ORs are shown elsewhere (Table S1 (94)). In total, 84 PGR variants have been evaluated for association with breast cancer risk. Six polymorphisms are located upstream of the PGR gene (approximately 3, 12, 13, 14, 24, and 49 kb). Two polymorphisms are located in the 5′ untranslated region. Within the protein-coding region of PGR, 5 variants are located in exons and 58 within introns. Ten polymorphisms are located in the 3′ untranslated region, and 2 are downstream of the PGR gene (approximately 0.2 and 2 kb). The location of 1 polymorphism (Hcv3182868) could not be determined since it was not defined in the publication (63) or included in the Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/.

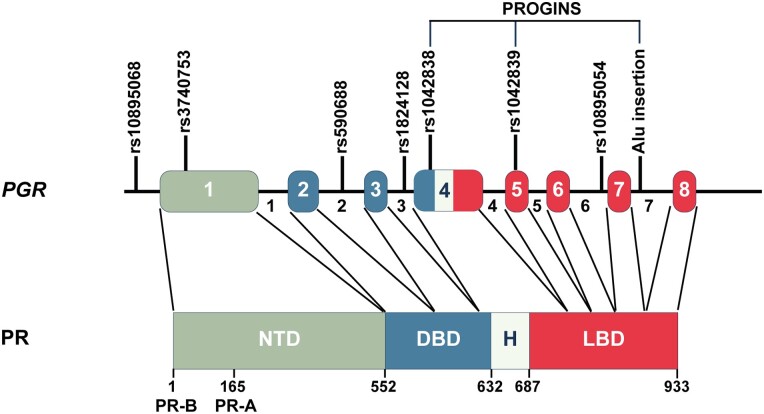

Of the 84 polymorphisms investigated, 7 were found to be significantly associated with breast cancer risk in at least 1 study (Table 2). These polymorphisms included the Alu insertion, rs1042838 (Val660Leu), rs3740753 (Ser344Thr), rs10895068 (+331G/A), rs590688 (intron 2), rs1824128 (intron 3), and rs10895054 (intron 6). All of these polymorphisms localize to the protein-coding region of PGR except rs10895068 (+331G/A), which is found in the 5′ untranslated region (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

PGR polymorphisms associated with breast cancer in at least 1 study

| Polymorphism | Increased association OR (95% CI) |

Decreased association OR (95% CI) |

No association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alu insertion | Hh = 3.44 (1.30-9.09) (38) Hh + hh = 3.11 (1.24-7.79) (38) |

Hh + hh = 0.76 (0.58-1.00) (75) | (37, 44, 50, 57, 60, 61, 70, 74) |

| Hh + hh = 1.7 (1.14-2.60) (49) minor allele = 1.9 (1.3-2.9) (49) | — | — | |

| minor allele = 2.9179 (1.1459-7.4302) (53) | — | — | |

| rs1042838 (Val660Leu) |

Hh = 1.83 (1.13-2.97) (52) | — | (36, 37, 39, 40, 42, 43, 45, 47, 48, 51, 58, 63, 65, 67-69, 71, 73) |

| Hh = 1.13 (1.03-1.24) (64) hh = 1.30 (0.98-1.73) (64) | |||

| rs3740753 (Ser344Thr) |

— | hh = 0.27 (0.07-0.96) (52) | (37, 39, 63, 67) |

| rs10895068 (+331G/A) |

Hh = 3.58 (1.38-9.29) (52) | minor allele OR not reported (71) | (37, 39, 41, 43, 46, 47, 57, 58, 62-64, 66-69) |

| Hh + hh = 1.31 (1.04-1.65) (59) | |||

| Hh + hh = 1.41 (1.10-1.79) (56) | |||

| rs590688 (intron 2) |

hh = 1.85 (1.11-3.08) (52) | minor allele = 0.56 (0.39-0.82) (48) | — |

| rs1824128 (intron 3) |

Hh + hh = 1.33 (1.14-1.55) (62) | — | (39) |

| rs10895054 (intron 6) |

minor allele = 2.9 (1.47-6.02) (48) | — | — |

Abbreviations: Hh, heterozygote; hh, rare minor allele homozygote; OR, odds ratio, as reported in each individual study.

Figure 2.

Polymorphism locations in the human progesterone receptor gene (PGR) reported to be associated with breast cancer risk. PGR is located on chromosome 11 and is comprised of 8 exons and 7 introns. The PGR gene maps to 101,019,603-101,139,830 in GRCh38.p13 coordinates. Exon coordinates and polymorphism locations can be found on the NCBI Variation Viewer website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/variation/view/). Polymorphisms reported to have an association with breast cancer in at least 1 study have been found in the 5′ untranslated region, within exons and introns. These polymorphisms include rs10895068 (+331G/A), rs3740753 (Ser344Thr), rs590688 (intron 2), rs1824128 (intron 3), rs1042838 (Val660Leu), rs10895054 (intron 6), and the Alu insertion (intron 7). The PROGINS haplotype consists of the Alu insertion (intron 7), rs1042838 (Val660Leu), and rs1042839 (His770His). Polymorphisms with no association with breast cancer risk are detailed in Table 2 and elsewhere (Table S1 (94)). Separate promoters are utilized to encode for 2 predominant progesterone receptor (PR) protein isoforms, PR-B (933 amino acids) and PR-A (769 amino acids; lacks first 164 amino acids in the N-terminus). NTD, N-terminal domain; DBD, DNA binding domain; H , hinge; LBD, ligand binding domain.

Increased risk of breast cancer was associated with rs1042838 (Val660Leu) in 2 studies (52, 64), rs1824128 (intron 3) in 1 study (62), and rs10895054 (intron 6) in 1 study (48). The variant rs3740753 (Ser344Thr) was associated with decreased risk of breast cancer in 1 study (52). Mixed results were reported for the variants rs590688 (intron 2), rs10895068 (+331G/A), and the Alu insertion. The Alu insertion was associated with increased breast cancer risk in 3 studies (38, 49, 53) and decreased risk in 1 study (75). The rs10895068 (+331G/A) was also associated with increased breast cancer risk in 3 studies (52, 56, 59) and decreased risk in 1 study (71). The variant rs590688 (intron 2) was associated with increased breast cancer risk in 1 study (52) and decreased risk of breast cancer in 1 study (48).

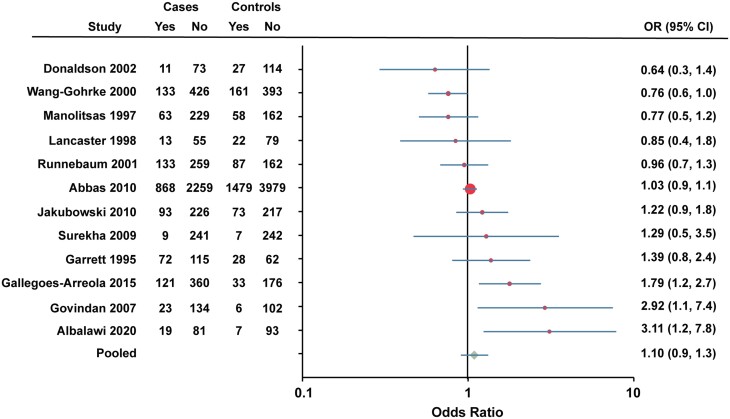

Results of Pooled Analyses

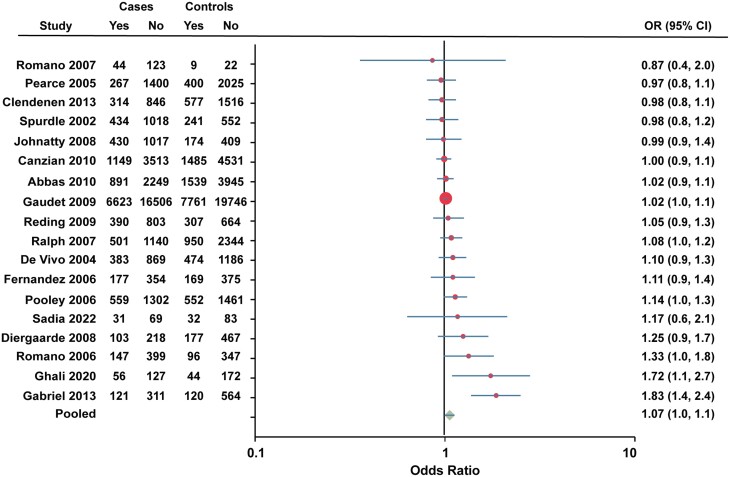

To summarize the results of individual studies, Forest plots were generated for variants that were included in 4 or more studies (Figs. 3-6). Twelve studies were combined to determine the association between the Alu insertion and breast cancer risk (Fig. 3). The pooled OR for the Alu insertion was 1.10 (95% CI 0.9-1.3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of association between Alu insertion and breast cancer risk. Data for Caucasian and African American women were combined for Donaldson et al (44). Data for Runnebaum et al (70) were calculated from percentages reported. Cases, individuals with breast cancer. Controls, individuals without breast cancer. Yes, heterozygote + rare homozygote. No, major allele homozygote. OR, odds ratio (unadjusted).

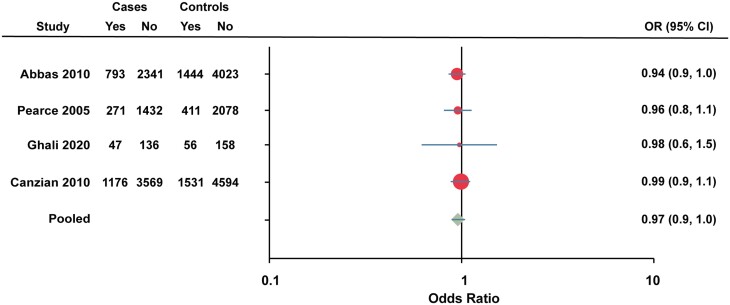

Figure 6.

Forest plot of association between rs3740753 (Ser344Thr) and breast cancer risk. Cases, individuals with breast cancer. Controls, individuals without breast cancer. Yes, heterozygote + rare homozygote. No, major allele homozygote. OR, odds ratio (unadjusted).

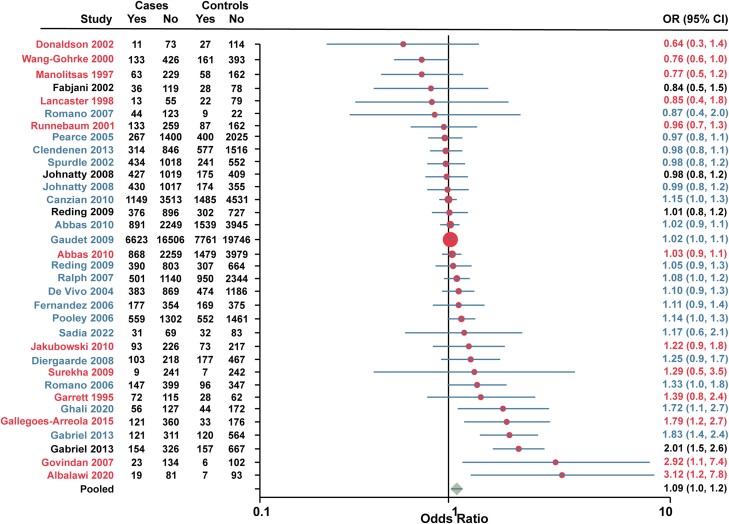

Eighteen studies were combined for rs1042838 (Val660Leu). The published study from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium in 2006 was excluded due to lack of reporting of the total individuals for each allele. The study by Fabjani et al (45) was also excluded from the pooled analysis since their data for rs1042838 (Val660Leu) and rs1042839 (His770His) could not be separated. The pooled OR for rs1042838 (Val660Leu) was 1.07 (95% CI 1.0-1.1; Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of association between rs1042838 (Val660Leu) and breast cancer risk. Data for European American and African American women were combined for Gabriel et al (48). Cases, individuals with breast cancer. Controls, individuals without breast cancer. Yes, heterozygote + rare homozygote. No, major allele homozygote. OR, odds ratio (unadjusted).

Since the Alu insertion and rs1042838 (Val660Leu) in combination with rs1042839 (His770His) have been found to be in complete linkage disequilibrium, an analysis was performed for studies which included these 3 variants (Fig. 5). There were 31 studies that included at least 1 variant classified as PROGINS with 3 studies examining multiple PROGINS variants. The pooled OR was 1.09 (95% CI 1.0-1.2).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of association between PROGINS and breast cancer risk. Red, Alu insertion. Black, rs1042839 (His770His). Blue, rs1042838 (Val660Leu). Note that the study by Fabjani et al (45) included both rs1042838 (Val660Leu) and rs1042839 (His770His). Data for European American and African American women were combined for Gabriel et al (48) Cases, individuals with breast cancer. Controls, individuals without breast cancer. Yes, heterozygote + rare homozygote. No, major allele homozygote. OR, odds ratio (unadjusted).

Pooled analysis of rs3740753 (Ser344Thr) was performed on 4 studies. The study by Pearce et al (63) was excluded from the pooled analysis due to lack of access to the raw data of the total individuals for each allele (Fig. 6). The pooled OR for rs3740753 (Ser344Thr) was 0.97 (95% CI 0.9-1.0).

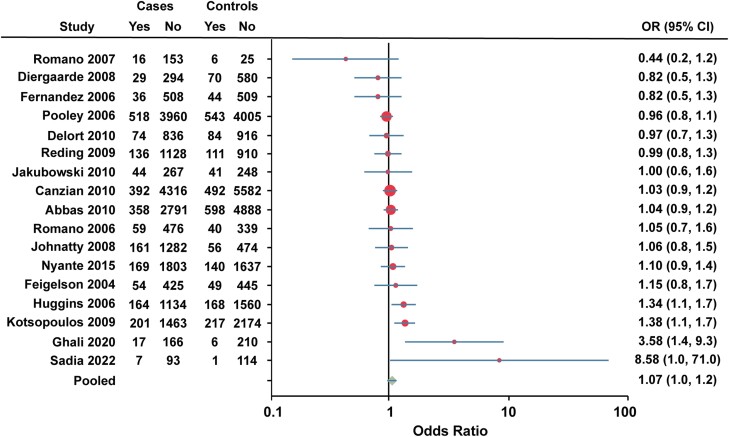

Seventeen studies were combined for rs10895068 (+331G/A). The study by Rebbeck et al (66) was excluded from the pooled analysis due to lack of reporting number of cases and controls for each allele (Fig. 7). The study by Pearce et al (63) was also excluded due to raw data inaccessibility. The pooled OR for rs10895068 (+331G/A) was 1.07 (95% CI 1.0-1.2).

Figure 7.

Forest plot of association between rs10895068 (+331G/A) and breast cancer risk. Cases, individuals with breast cancer. Controls, individuals without breast cancer. Yes, heterozygote + rare homozygote. No, major allele homozygote. OR, odds ratio (unadjusted).

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate the association between polymorphisms in PGR with breast cancer risk. Of the 84 polymorphisms investigated, 7 variants were found to be associated with breast cancer risk in at least 1 study. These 7 variants included the PROGINS haplotype (Alu insertion and rs1042838 (Val660Leu)), rs3740753 (Ser344Thr), rs10895068 (+331G/A), rs590688 (intron 2), rs1824128 (intron 3), and rs10895054 (intron 6). However, pooled analyses for the Alu insertion, rs1042838 (Val660Leu), rs3740753 (Ser344Thr), and rs10895068 (+331G/A) did not show an association with breast cancer risk. The functional effects of these polymorphisms and results of the individual published studies and meta-analyses will be discussed further.

PROGINS

The PROGINS variant was first described as a 306-bp Alu element insertion in intron 7 of PGR between exons 7 and 8 (95). Subsequently, the Alu insertion was demonstrated to be in complete linkage disequilibrium with 2 single nucleotide polymorphisms, meaning these 3 polymorphisms always occur together (73, 96, 97). One of these polymorphisms, rs1042838 (Val660Leu), is located in exon 4 and results in a missense mutation in the ligand binding domain (73, 96, 97). The other polymorphism, rs1042839 (His770His), is found in exon 5 and results in a silent mutation (96, 97). Any 1 of these 3 polymorphisms may be detected as a marker of the PROGINS variant. T47D breast cancer cells are heterozygous for the PROGINS variant and MCF-7 breast cancer cells are homozygous for the PROGINS variant (98). The altered risks observed with the PROGINS variant are thought to be due to functional consequences resulting from the intronic Alu insertion and the Val660Leu missense mutation.

PROGINS—Alu Insertion

Rowe et al identified a variant PGR allele consisting of a 306-base pair sequence insertion (NCBI Z49816) within intron 7 (historically referred to as intron G) between exons 7 and 8 which includes an Alu direct repeat element of the predicted variant/human-specific subfamily (95). The Alu insertion contains an extra TaqI restriction enzyme recognition site, which led to its initial identification as a restriction fragment length polymorphism (99). The Alu insertion polymorphism is found in humans but is not present in nonhuman primates (44). Interestingly, the Alu insertion was found to be polymorphic among the sequenced genomes of Neanderthals (60 000-120 000 years old) (100). In modern humans, the highest allelic frequency of the Alu insertion was observed in the Greek population (22%) and was lowest in 2 African groups (0%) with an average allele frequency of 11% across all populations (44). Rockwell et al found that breast cancer incidence positively correlated with the frequency of the Alu insertion (r = 0.86, P < .05) across 15 populations worldwide (80).

Possible functional effects of the Alu insertion include altered DNA methylation, gene transcription and transcription factor binding, or generation of splice variants. The Alu insertion introduces a consensus splice acceptor site downstream of a consensus splice donor site, which was initially hypothesized to result in missplicing and an exon 8 splice variant that could impact PR ligand binding and transcriptional activity (95). However, Romano et al characterized the Alu insertion and found that this polymorphism does not generate splice variants, nor does it alter DNA methylation (98). The Alu insertion contains a half estrogen response element/Sp1 binding site, which acts as an enhancer, increasing the transcription of the PROGINS allele in response to 17β-estradiol (98). This study also found that the Alu insertion results in reduced transcript stability, which may be due to RNA decay pathways or dsRNA-mediated degradation (98). Thus, the functional effect of the Alu insertion is increased transcription of the PROGINS allele in response to 17β-estradiol, but with reduced transcript stability (98).

Twelve studies examined the association between the Alu insertion and breast cancer risk. In the study by Govindan et al which included Asian Indian women, the Alu insertion was associated with increased risk of breast cancer (minor allele OR 2.9179, 95% CI 1.1459-7.4302, P = .0332) (53). Gallegos-Arreola et al also found an increased association of the Alu insertion with breast cancer (heterozygote + rare homozygote OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.14-2.6, P = .009) in their study population of women living in Mexico (49). For Saudi Arabian women, Albalawi et al demonstrated that the Alu insertion was associated with increased breast cancer risk (heterozygote OR 3.44, 95% CI 1.30-9.09 and heterozygote + rare homozygote OR 3.11, 95% CI 1.24-7.79) (38). In contrast, Wang-Gohrke et al found the polymorphism was protective against breast cancer development before the age of 50 years in German Caucasian women (heterozygote + rare homozygote OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.58-1.00) (75). Furthermore, their data suggest an allele dosage effect since the OR decreased with increased number of polymorphic alleles (75). Other studies found no association with breast cancer risk (37, 44, 50, 57, 60, 61, 70, 74). The largest study, Abbas et al (37), included 3149 postmenopausal breast cancer cases and 5489 controls from 2 German population-based case–control studies which showed no association with an OR of 1.04 (95% CI 0.9-1.1). The underlying basis for these conflicting findings is not clear but may be related to a weak differential effect on disease risk by menopausal status (75).

A systematic review published by Dunning et al (90), which included a joint analysis of 3 studies (50, 60, 61), reported that individuals carrying the rare homozygote genotype were at decreased risk for breast cancer, though this result was of borderline statistical significance (joint analysis OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.15-0.95). Subsequently, Yao et al conducted an updated meta-analysis of 10 studies and concluded that the Alu insertion was not associated with breast cancer risk under the dominant genetic model (pooled OR 1.025, 95% CI 0.526-1.994, P = .943) (85). However, under subgroup analysis according to ethnicity, the Alu insertion was associated with decreased breast cancer risk in Indian individuals (OR 0.091, 95% CI 0.033-0.254, P < .001) and increased breast cancer risk in Indo-European mixed racial groups (OR 11.620, 95% CI 5.331-25.327, P < .001). No association was present for Caucasian or Latino individuals (85). This difference in association may be attributed to the genetic backgrounds of racial groups, as well as different environmental and lifestyle factors.

PROGINS—rs1042838 (Val660Leu)

The rs1042838 (Val660Leu) allele was found to be homozygously present among several genomes from Neanderthal individuals but was not observed in the Denisovan genome, another group of archaic humans who lived 72 000 years ago (100, 101). A 40 000-year-old individual from Tianyuan Cave, China, is the oldest modern human with this variant (100, 102). The variant was found to become progressively more common in Western Eurasia genomes between 5000 and 10 000 years old (100). Currently, the rs1042838 (Val660Leu) variant is found more often in European (18% frequency) and South Asian populations (7% frequency) and is not found in African populations (101).

The proposed functional consequences of rs1042838 (Val660Leu) may be due to its impact on the hinge region of PR protein between the DNA binding domain and ligand binding domain. The hinge region has roles in receptor dimerization and coregulator interaction (103, 104). Leucine differs from valine by an additional methyl group, and this larger amino acid may alter the angle and flexibility of the hinge region. In support of this hypothesis, Romano et al showed that the conformational change in PR with ligand binding differs with Val660Leu compared with wild type (98). Agoulnik et al demonstrated increased protein stability of Val660Leu PR resulting in higher protein levels than wild-type PR for both A and B isoforms (97). Using data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression project, Zeberg et al also found that Val660Leu was associated with higher PR mRNA expression (100). Furthermore, there was increased transcriptional activity of Val660Leu PR compared with wild-type PR for both A and B isoforms in transiently transfected COS-1 (African green monkey kidney fibroblast-like) cells, MDAH:2774 ovarian cancer cells, and HeLa cervical cancer cells using a glucocorticoid response element-chloroamphenicol acetyltransferase reporter gene assay (97). No difference in hormone binding or hormone dissociation rates were observed (97). In contrast, Romano et al demonstrated decreased transcriptional activity of Val660Leu PR-B and PR-A stably expressed in CHO-K1 (Chinese hamster ovary) cells and in transiently transfected SKOV-3 ovarian cancer cells (98). There was no effect of Val660Leu on PR transcriptional activity in transiently transfected HeLa cervical cancer cells, MDAH-2774 ovarian cancer cells, or MCF-7 breast cancer cells using an mouse mammary tumor virus luciferase reporter gene assay (98). This study also revealed differences in PR phosphorylation and protein degradation for Val660Leu PR compared with wild-type PR (98). For instance, Val660Leu PR was more extensively phosphorylated after 24 hours of ligand treatment compared with wild-type PR for both isoforms (98). Also, proteasome-mediated degradation of PR-A protein in response to ligand was reduced with the Val660Leu variant compared with wild type (98). There was no effect of Val660Leu on ligand-induced protein degradation for PR-B (98). The inhibitory effect of progestin on proliferation of CHO stable cell lines was reduced in Val660Leu PR-A expressing cells (98). Thus, the effect of the rs1042838 (Val660Leu) polymorphism on PR function appears to be cell type, gene promoter, and receptor isoform specific. Another hypothesized functional effect of Val660Leu is abnormal RNA splicing and exon skipping; however, this has not been tested (64).

Twenty studies evaluated the association between the rs1042838 (Val660Leu) polymorphism and breast cancer risk. Ghali et al concluded that Tunisian women carrying the heterozygote genotype had an increased risk of breast cancer (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.13-2.97) (52). Similarly, Pooley et al found that the rs1042838 (Val660Leu) allele was associated with a small increased risk of breast cancer (64). In their study population from the United Kingdom, the heterozygote and rare homozygote genotypes were associated with increased risk of breast cancer (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.03-1.24 and OR 1.30, 95% CI 0.98-1.73, respectively) (64). These investigators also performed a combined analysis of their data and 3 other published studies (42, 63, 73) which demonstrated a similar increased risk estimate (OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02-1.17, P = .009) (64). However, the authors comment that “it should be emphasized that the size of the estimated odds ratios are moderate and despite the size of the combined data set (10 648 cases and 7915 controls), the level of significance is such that the association could still be attributable to chance” (64).

Most studies found no statistically significant association between rs1042838 (Val660Leu) and breast cancer risk (36, 37, 39, 40, 42, 43, 47, 48, 51, 63, 65, 67-69, 71, 73). The largest study reported by Gaudet et al consisted of 23 129 cases and 27 597 controls using data from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium concluded that rs1042838 (Val660Leu) was not associated with risk of invasive breast cancer. However, significant between-study heterogeneity was observed, and the authors noted that this polymorphism “may be associated with breast cancer risk for small subgroups of women” (51). This study was performed as follow up of their initial study published in 2006 with borderline significant results (P = .047) of an association between rs1042838 (Val660Leu) and breast cancer risk (36). Fabjani et al used reverse allele-specific oligonucleotide hybridization to measure both the rs1042838 (Val660Leu) and rs1042839 (His770His) variants and similarly found no significant association with breast cancer risk (45). Although there was no significant association in the overall population reported by Diergaarde et al, the authors found that the polymorphism increased risk associated with postmenopausal hormone therapy use (estrogen and progesterone) (43). There was a statistically significant interaction between rs1042838 (Val660Leu) and years of estrogen and progesterone hormone therapy use (OR 1.9 for 1-10 years of use, 95% CI 1.1-3.2, and OR 3.1 for greater than 10 years of use, 95% CI 1.8-5.6, P = .01) (43). Johnatty et al found no statistically significant association between rs1042838 (Val660Leu) and breast cancer risk in their Australian study population that included familial breast cancer cases (58). These investigators also performed a meta-analysis combining their data and 6 other published studies (42, 47, 63, 64, 68, 75), for a total of 10 205 cases and 11 320 controls (58). The meta-analysis demonstrated a statistically nonsignificant increased risk for breast cancer for heterozygote and rare homozygote genotypes; however, they found a significant leucine allele dosage effect (per leucine allele OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.02-1.13, P = .01), thus concluding that the rs1042838 (Val660Leu) variant may be associated with a small increase in breast cancer risk (58). A large meta-analysis subsequently published by Zhang et al found no association between rs1042838 (Val660Leu) and breast cancer risk (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.98-1.07, P = .300) in 28 studies with 31 672 cases and 37 579 controls (89).

rs3740753 (Ser344Thr)

A PGR polymorphism that is in partial linkage disequilibrium with the PROGINS haplotype is rs3740753 (Ser344Thr) (96, 105, 106). MCF-7 and T47D human breast cancer cell lines have been shown to have the rs3740753 (Ser344Thr) variant (107). This variant is located in exon 1 of PGR and the N-terminal domain of PR-A and PR-B protein. Although the N-terminal domain contains several serine residues for basal and hormone-induced phosphorylation, serine 344 is not a known site of phosphorylation (108-110). However, the adjacent serine 345 residue is a well-characterized phosphorylation site in response to rapid progesterone signaling (109, 111, 112). It has also been hypothesized that the change in size of the side chain due to Ser344Thr may have steric effects on tertiary protein structure; however, this has not been directly tested (64). To investigate the functional consequences of this variant, Stenzig et al created stable cell lines expressing Ser344Thr and Val660Leu for both PR-A and PR-B isoforms using PR-negative T47DY breast cancer cells (113). They found no difference in hormone binding or transactivation function with the variant PR compared with wild-type PR (113). Thus, there does not appear to be a significant effect of Ser344Thr on PR function.

Five studies have investigated the association of rs3740753 (Ser344Thr) with breast cancer risk (37, 39, 52, 63, 67). Ghali et al demonstrated an association with marginally decreased breast cancer risk for women with the homozygote minor allele (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.07-0.96) (52). However, other studies (37, 39, 63) did not find a statistically significant association, including the large study by Abbas (37) with 3149 postmenopausal breast cancer cases and 5489 controls.

rs10895068 (+331G/A)

The rs10895068 (+331G/A) variant is found in the PGR gene between the transcriptional start sites for PR-B (nucleotide position +1) and PR-A (nucleotide position +751) and has been widely studied due to its functional effects (96). This variant localizes to the 5′ untranslated region of PR-B and the promoter region for PR-A (96). De Vivo et al demonstrated that the rs10895068 (+331G/A) variant produces a new transcriptional start site and increases PGR promoter activity (96). Additionally, this polymorphism enhances transcription of PR-B resulting in increased expression of PR-B protein (96). Altered regulation of the relative expression levels of PR-A and PR-B has been shown to occur early in the development of breast cancer (30). Huggins et al demonstrated that the rs10895068 (+331G/A) variant is immediately downstream of a GATA protein binding site (AGATAA) (56). The GATA family are transcription factors that share DNA binding sites and activate genes important for cell differentiation (114). Huggins et al found that GATA5 is preferentially expressed in breast cancer compared with normal mammary tissue and that GATA5 binds to the GATA recognition site, increases PGR promoter activity, and favors increased PR-B transcript expression (56). The authors also showed that the rs10895068 (+331G/A) variant increases PGR promoter activation by GATA5 compared to wild-type and does not alter GATA5 binding to the GATA recognition site (56). Thus, the rs10895068 (+331G/A) variant affects GATA5-dependent regulation of PGR (56).

Rockwell et al found that breast cancer incidence positively correlated with the frequency of the rs10895068 (+331G/A) variant (r = 0.57, P < 0.05) across 15 populations worldwide (80). Among 19 studies evaluating the rs10895068 (+331G/A) variant, 3 studies demonstrated a statistically significant association with increased breast cancer risk (52, 56, 59). Using data from the Nurses’ Health Study cohort, Huggins et al found a significant association between the variant and breast cancer risk (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.10-1.79) (56). Furthermore, they observed the strongest association (OR 2.87, 95% CI 1.40-5.90) in postmenopausal, obese (body mass index >30 kg/m2) women (56). In a subsequent analysis restricted to Caucasian postmenopausal women, Kotsopoulos et al reported a significant association between the variant and breast cancer risk (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.04-1.65) (59). Contrary to their hypothesis, the association was strongest among women who never used postmenopausal hormone therapy (OR 2.57, 95% CI 1.64-4.02) (59). Ghali et al concluded that women carrying the heterozygote genotype have an increased risk for breast cancer (OR 3.58, 95% CI 1.38-9.29) (52). In contrast, 1 study published by Sadia et al found an inverse association between rare homozygote carriers of rs10895068 (+331G/A) and breast cancer risk in Southern Punjab Pakistani women (χ2 = 9.13, P = .004) (71). However, the sample size in their study was small with large variance, and thus should be interpreted with caution.

Other studies did not find an association between rs10895068 (+331G/A) and breast cancer risk (37, 39, 41, 43, 46, 47, 57, 58, 62-64, 66-69). Two of the largest studies were reported by Abbas (37), with 3149 postmenopausal breast cancer cases and 5489 controls from 2 German population-based case–control studies, and by Canzian et al (39), with 6292 cases and 8135 controls, mostly Caucasian postmenopausal women, from the National Cancer Institute Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium. Likewise, Romano et al did not detect an association between the rs10895068 (+331G/A) variant and breast cancer risk when analyzed alone (68). However, increased breast cancer risk was identified for the small number of patients carrying both the rs10895068 (+331G/A) and rs1042838 (Val660Leu) alleles (OR 3.9; 95% CI 1.1-13.5, P = .02) (68). Furthermore, the rs10895068 (+331G/A) variant may act synergistically with BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations (69). Rebbeck et al found no overall association of the rs10895068 (+331G/A) variant and breast cancer risk but did observe increased risk of ductal carcinoma (adjusted OR 3.35; 95% CI 1.13-9.99) and PR+ tumors (adjusted OR 3.82; 95% CI 1.26-11.55) for women who inherited the rs10895068 (+331G/A) variant and have long-term use of combined hormone replacement therapy containing both estrogens and progestins (66). Thus, the association between rs10895068 (+331G/A) and breast cancer risk appears to be modified by the presence of other PGR variants, pathogenic BRCA gene mutations, and combined hormone replacement therapy.

Several meta-analyses have been performed to clarify the association between the rs10895068 (+331G/A) polymorphism and breast cancer risk which have yielded differing results (84,87-89). Meta-analyses performed by Yu et al (88) and Zhang et al (89) found no association with breast cancer risk. In the meta-analysis performed by Yang et al, no association with breast cancer risk was observed in the overall study population (87). However, subgroup analysis showed an increased risk of breast cancer in Americans with the rs10895068 (+331G/A) polymorphism (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.10-1.58), but not for European or Australian women (87). The most recently published meta-analysis by Qi et al found an overall association with breast cancer risk (pooled OR 1.140, 95% CI 1.015-1.279) (84). However, subgroup analysis based on ethnicity did not show a significant association (84). A broader meta-analysis published by Chaudhary et al, which included 10 studies of breast cancer, 6 studies of ovarian cancer, and 3 studies of endometrial cancer, concluded that the rs10895068 (+331G/A) variant was associated with mild increased risk of overall female reproductive cancer (OR 1.067, 95% CI 1.002-1.136) (86).

rs590688 (intron 2)

The variant rs590688 localizes to intron 2 of PGR and any functional consequences of this variant have yet to be reported. Using data from the Women's Insights and Shared Experiences (WISE) study involving postmenopausal women living in the Philadelphia metropolitan area, Gabriel et al (48) found that each addition of the variant C allele decreased the risk of breast cancer compared with the wild-type G allele in the African American subgroup (per allele OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.39-0.82). A nonsignificant decreased risk of breast cancer was seen in European American women (48). The discrepancy in findings between the European and African American subgroups was not clear and the authors postulate possible interactions between multiple SNPs and environmental or genetics factors that were not measured in the study (48). In contrast, Ghali et al found an association between rs590688 and increased breast cancer risk (homozygote minor allele OR 1.85, 95% CI 1.11-3.08) in a retrospective case–control study of Tunisian women (52). The variant rs590688 (intron 2) was found to be in linkage disequilibrium with rs1042838 (Val660Leu) and rs10895068 (+331G/A) in this study population (52).

rs1824128 (intron 3)

rs1824128 is found in intron 3 of PGR, and there are no proposed functional effects of this polymorphism. The variant was evaluated in a population-based case–control study of breast cancer in North Carolina consisting of 1972 cases and 1766 controls (Carolina Breast Cancer Study) (62). Nyante et al found that rs1824128 was associated with increased breast cancer risk (heterozygote + rare homozygote OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.14-1.55) (62). In this study, there was a stronger association between rs1824128 and risk among African American women compared with non-African American women despite similar genotype frequencies for rs1824128 in both populations (62). No association was found between this polymorphism and breast cancer risk in the large study by Canzian et al which used the National Cancer Institute Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium (6292 cases and 8135 controls), consisting mostly of postmenopausal Caucasian women (39).

rs10895054 (intron 6)

rs10895054 is found in intron 6 of PGR. No known functional consequences of this variant have been reported. Using data from the Women's Insights and Shared Experiences (WISE) study involving postmenopausal women living in the Philadelphia metropolitan area, Gabriel et al found that each addition of the variant T allele for rs10895054 increased the risk of breast cancer compared to the wild-type A allele in the African American subgroup (per allele OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.47-6.02) (48). The authors note that their study was the first to demonstrate an association between this PGR variant and breast cancer risk in African American women. For European American women, there was a slight increased risk of breast cancer (per allele OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.93-1.52), but this result was not statistically significant (48). Interestingly, nulliparity and obesity (body mass index ≥30.0 kg/m2) were associated with a statistically significant decrease in breast cancer risk in the European American cohort. Thus, factors such as race, parity, and body mass index appear to modify the effect of rs10895054 on breast cancer risk.

Conclusions

This systematic review has several strengths. First, this review is a comprehensive examination of the polymorphisms in PGR studied in association with breast cancer risk, whereas previous reviews have focused on only 1 variant in PGR or several variants and several genes. The systematic approach of this review allows for interpretation of the published results in a collective manner. Second, this review maps each variant to the gene location and discusses the structure-function analyses that have been performed, thus placing into context the potential impact of PGR variants on PR protein isoform expression levels and transcriptional activity. Lastly, recently published studies that have not been used in previous reviews and meta-analyses are included.

There are some limitations of this systematic review. First, the retrospective case–control study design used by the included studies can be susceptible to selection bias. Second, some PGR polymorphisms have only been evaluated in 1 or a few studies resulting in small sample sizes, which makes it difficult to generate generalizable conclusions. Third, differences in the methods used for reporting results make direct comparison between studies challenging. For example, which frequencies were recorded and which parameters were used to adjust ORs frequently differed. Participant characteristics were also described with variable detail, and ethnicity was often lacking, which could be an important factor. Rockwell et al analyzed global patterns of polymorphisms in PGR and incidence of female reproductive cancers (80). The researchers found differences in the frequency of each of the variants across study populations, indicating roles of genetics, the environment, and lifestyle in female reproductive cancer development (80). Therefore, another limitation of this review is the inability to account for other factors influencing breast cancer risk such as the environment, diet, and lifestyle that may contribute to genetic factors.

There is some evidence that several polymorphisms in PGR may have a small contribution to breast cancer risk in certain populations. However, larger studies with mixed populations and our pooled analysis have not confirmed these findings. The underlying basis for conflicting findings between the studies is not clear. Individual studies discuss possible explanations such as “gene–gene” or “gene–environment” interactions (36), age-specific genetic associations (65), and genotype–hormone interactions (66). Furthermore, differences in ethnicity, menopausal status, and obesity of the cohorts may be contributing factors to conflicting study findings (56). Heterogeneous study populations may obscure weak genetic associations, which are diluted by lack of association in the entire sample set (65).

It is interesting that 2 of the polymorphisms comprising the PROGINS allele (rs1042838 and the Alu insertion) have been frequently reported to be in complete linkage disequilibrium, yet the literature regarding their relative allele frequencies in subpopulations and their reported associations, or lack thereof, with breast cancer differs. The cause for this discrepancy is not clear but implies the possible influence of additional nongenetic modifying factors.

Further research is needed to better understand PGR polymorphisms and their potential functional consequences. Based on the results of this systematic review, attention should focus on PGR variants found to be associated with breast cancer risk in at least 1 study: rs1042838 (Val660Leu), rs3740753 (Ser344Thr), rs10895068 (+331G/A), rs590688 (intron 2), rs1824128 (intron 3), rs10895054 (intron 6), and the Alu insertion (intron 7). In addition, ethnicity may have a role in influencing breast cancer development in the presence of PGR polymorphisms and therefore future studies should be conducted examining different ethnic groups. Other factors reported to contribute to differences in breast cancer risk associated with PGR polymorphisms, including obesity and postmenopausal hormone therapy use, will be important to consider. A better understanding of high prevalence, low penetrance genetic modifiers of breast cancer risk may help personalize screening approaches and risk-reducing preventive strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Health Sciences Learning Center Ebling Library's Systematic Review Team at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health for assistance with the electronic literature search.

Abbreviations

- ER

estrogen receptor

- PR

progesterone receptor

- PGR

progesterone receptor gene

Contributor Information

Alecia Vang, Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI 53792, USA.

Kelley Salem, Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI 53792, USA.

Amy M Fowler, Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI 53792, USA; University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center, Madison, WI 53792, USA; Department of Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI 53705, USA.

Funding

Research support was provided by the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Shapiro Summer Research Program, the University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Radiology, and the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA014520. Funding sources for AMF include the American Cancer Society (RSG-22-015-01-CCB) and the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (R01 CA272571). The funders had no role in the design, performance, or publication of the review.

Disclosures

A.V. and K.S. have nothing to declare. A.M.F. receives book chapter royalty from Elsevier, Inc., and has served on an advisory board for GE Healthcare. The University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Department of Radiology receives research support from GE Healthcare.

Data Availability

Data extracted from the included studies and the data used for all analyses are available as tables in this review.

Registration and Protocol

Details of the protocol for this systematic review are registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) (115) under CRD42020208369 and can be accessed at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020208369.

References

- 1. Brisken C, Scabia V. 90 years of progesterone: progesterone receptor signaling in the normal breast and its implications for cancer. J Mol Endocrinol. 2020;65(1):T81–T94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Giulianelli S, Lamb CA, Lanari C. Progesterone receptors in normal breast development and breast cancer. Essays Biochem. 2021;65(6):951–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horwitz KB, Sartorius CA. 90 years of progesterone: progesterone and progesterone receptors in breast cancer: past, present, future. J Mol Endocrinol. 2020;65(1):T49–T63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rousseau-Merck MF, Misrahi M, Loosfelt H, Milgrom E, Berger R. Localization of the human progesterone receptor gene to chromosome 11q22-q23. Hum Genet. 1987;77(3):280–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mattei MG, Krust A, Stropp U, Mattei JF, Chambon P. Assignment of the human progesterone receptor to the q22 band of chromosome 11. Hum Genet. 1988;78(1):96–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Misrahi M, Venencie PY, Saugier-Veber P, Sar S, Dessen P, Milgrom E. Structure of the human progesterone receptor gene. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1216(2):289–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kastner P, Krust A, Turcotte B, et al. Two distinct estrogen-regulated promoters generate transcripts encoding the two functionally different human progesterone receptor forms A and B. EMBO J. 1990;9(5):1603–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kastner P, Bocquel MT, Turcotte B, et al. Transient expression of human and chicken progesterone receptors does not support alternative translational initiation from a single mRNA as the mechanism generating two receptor isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(21):12163–12167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vegeto E, Shahbaz MM, Wen DX, Goldman ME, O'Malley BW, McDonnell DP. Human progesterone receptor A form is a cell- and promoter-specific repressor of human progesterone receptor B function. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7(10):1244–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Salem K, Kumar M, Yan Y, et al. Sensitivity and isoform specificity of (18)F-fluorofuranylnorprogesterone for measuring progesterone receptor protein response to estradiol challenge in breast cancer. J Nucl Med. 2019;60(2):220–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giangrande PH, Pollio G, McDonnell DP. Mapping and characterization of the functional domains responsible for the differential activity of the A and B isoforms of the human progesterone receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(52):32889–32900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Richer JK, Jacobsen BM, Manning NG, Abel MG, Wolf DM, Horwitz KB. Differential gene regulation by the two progesterone receptor isoforms in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(7):5209–5218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Graham JD, Clarke CL. Expression and transcriptional activity of progesterone receptor A and progesterone receptor B in mammalian cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2002;4(5):187–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Funk CR, et al. Mice lacking progesterone receptor exhibit pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1995;9(18):2266–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mulac-Jericevic B, Mullinax RA, DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP, Conneely OM. Subgroup of reproductive functions of progesterone mediated by progesterone receptor-B isoform. Science. 2000;289(5485):1751–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mulac-Jericevic B, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Conneely OM. Defective mammary gland morphogenesis in mice lacking the progesterone receptor B isoform. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(17):9744–9749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shyamala G, Yang X, Cardiff RD, Dale E. Impact of progesterone receptor on cell-fate decisions during mammary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(7):3044–3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shyamala G, Yang X, Silberstein G, Barcellos-Hoff MH, Dale E. Transgenic mice carrying an imbalance in the native ratio of A to B forms of progesterone receptor exhibit developmental abnormalities in mammary glands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(2):696–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kampert JB, Whittemore AS, Paffenbarger RS Jr. Combined effect of childbearing, menstrual events, and body size on age-specific breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128(5):962–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Travis RC, Key TJ. Oestrogen exposure and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5(5):239–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Waks AG, Winer EP. Breast cancer treatment: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(3):288–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nelson HD, Fu R, Zakher B, Pappas M, McDonagh M. Medication use for the risk reduction of primary breast cancer in women: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2019;322(9):868–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pike MC, Spicer DV, Dahmoush L, Press MF. Estrogens, progestogens, normal breast cell proliferation, and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15(1):17–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's health initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer . Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. Lancet. 2019;394(10204):1159–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beral V. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the million women study. Lancet. 2003;362(9392):419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trabert B, Bauer DC, Buist DSM, et al. Association of circulating progesterone with breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3(4):e203645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Key TJ, Appleby PN, Reeves GK, et al. Sex hormones and risk of breast cancer in premenopausal women: a collaborative reanalysis of individual participant data from seven prospective studies. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(10):1009–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mote PA, Bartow S, Tran N, Clarke CL. Loss of co-ordinate expression of progesterone receptors A and B is an early event in breast carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;72(2):163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bamberger AM, Milde-Langosch K, Schulte HM, Loning T. Progesterone receptor isoforms, PR-B and PR-A, in breast cancer: correlations with clinicopathologic tumor parameters and expression of AP-1 factors. Horm Res. 2000;54(1):32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Graham JD, Yeates C, Balleine RL, et al. Characterization of progesterone receptor A and B expression in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55(21):5063–5068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lamb CA, Fabris VT, Jacobsen B, Molinolo AA, Lanari C. Biological and clinical impact of imbalanced progesterone receptor isoform ratios in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(12):R605–R624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hopp TA, Weiss HL, Hilsenbeck SG, et al. Breast cancer patients with progesterone receptor PR-A-rich tumors have poorer disease-free survival rates. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(8):2751–2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rojas PA, May M, Sequeira GR, et al. Progesterone receptor isoform ratio: a breast cancer prognostic and predictive factor for antiprogestin responsiveness. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(7):djw317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Breast Cancer Association Consortium . Commonly studied single-nucleotide polymorphisms and breast cancer: results from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(19):1382–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Abbas S. Polymorphisms in genes of the steroid receptor superfamily modify postmenopausal breast cancer risk associated with menopausal hormone therapy. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(12):2935–2946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Albalawi IA, Mir R, Abu-Duhier FM. Molecular evaluation of PROGINS mutation in progesterone receptor gene and determination of its frequency, distribution pattern and association with breast cancer susceptibility in Saudi Arabia. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2020;20(5):760–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Canzian F, Cox DG, Setiawan VW, et al. Comprehensive analysis of common genetic variation in 61 genes related to steroid hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I metabolism and breast cancer risk in the NCI breast and prostate cancer cohort consortium. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(19):3873–3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Clendenen T, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Wirgin I, et al. Genetic variants in hormone-related genes and risk of breast cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Delort L, Satih S, Kwiatkowski F, Bignon Y-J, Bernard-Gallon DJ. Evaluation of breast cancer risk in a multigenic model including low penetrance genes involved in xenobiotic and estrogen metabolisms. Nutr Cancer. 2010;62(2):243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. De Vivo I, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ. The progesterone receptor Val660 →leu polymorphism and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(6):R636–R639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Diergaarde B, Potter JD, Jupe ER, et al. Polymorphisms in genes involved in sex hormone metabolism, estrogen plus progestin hormone therapy use, and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(7):1751–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Donaldson CJ, Crapanzano JP, Watson JC, Levine EA, Batzer MA. PROGINS Alu insertion and human genomic diversity. Mutat Res. 2002;501(1-2):137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fabjani G, Tong D, Czerwenka K, et al. Human progesterone receptor gene polymorphism PROGINS and risk for breast cancer in Austrian women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;72(2):131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Feigelson HS, Rodriguez C, Jacobs EJ, Diver WR, Thun MJ, Calle EE. No association between the progesterone receptor gene +331G/A polymorphism and breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(6):1084–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fernandez LP, Milne RL, Barroso E, et al. Estrogen and progesterone receptor gene polymorphisms and sporadic breast cancer risk: a Spanish case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(2):467–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gabriel CA, Mitra N, Demichele A, Rebbeck T. Association of progesterone receptor gene (PGR) variants and breast cancer risk in African American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139(3):833–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gallegos-Arreola MP, Figuera LE, Flores-Ramos LG, Puebla-Perez AM, Zuniga-Gonzalez GM. Association of the Alu insertion polymorphism in the progesterone receptor gene with breast cancer in a Mexican population. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11(3):551–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Garrett E, Rowe SM, Coughlan SJ, et al. Mendelian Inheritance of a TaqI restriction fragment length polymorphism due to an insertion in the human progesterone receptor gene and its allelic imbalance in breast cancer. Cancer Res Ther Control. 1995;4(3):217–222. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gaudet MM, Milne RL, Cox A, et al. Five polymorphisms and breast cancer risk: results from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(5):1610–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ghali RM, Al-Mutawa MA, Ebrahim BH, et al. Progesterone receptor (PGR) gene variants associated with breast cancer and associated features: a case-control study. Pathol Oncol Res. 2020;26(1):141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Govindan S, Ahmad SN, Vedicherla B, et al. Association of progesterone receptor gene polymorphism (PROGINS) with endometriosis, uterine fibroids and breast cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2007;3(2):73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Haddad SA, Lunetta KL, Ruiz-Narváez EA, et al. Hormone-related pathways and risk of breast cancer subtypes in African American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;154(1):145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Harlid S, Ivarsson MI, Butt S, et al. A candidate CpG SNP approach identifies a breast cancer associated ESR1-SNP. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(7):1689–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Huggins GS, Wong JY, Hankinson SE, De Vivo I. GATA5 Activation of the progesterone receptor gene promoter in breast cancer cells is influenced by the +331G/A polymorphism. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1384–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jakubowska A, Gronwald J, Menkiszak J, et al. BRCA1-associated Breast and ovarian cancer risks in Poland: no association with commonly studied polymorphisms. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119(1):201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Johnatty SE, Spurdle AB, Beesley J, et al. Progesterone receptor polymorphisms and risk of breast cancer: results from two Australian breast cancer studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109(1):91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kotsopoulos J, Tworoger SS, De Vivo I, et al. +331G/A variant in the progesterone receptor gene, postmenopausal hormone use and risk of breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(7):1685–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lancaster JM, Berchuck A, Carney ME, Wiseman R, Taylor JA. Progesterone receptor gene polymorphism and risk for breast and ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;78(2):277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Manolitsas TP, Englefield P, Eccles DM, Campbell IG. No association of a 306-bp insertion polymorphism in the progesterone receptor gene with ovarian and breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1997;75(9):1398–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nyante SJ, Gammon MD, Kaufman JS, et al. Genetic variation in estrogen and progesterone pathway genes and breast cancer risk: an exploration of tumor subtype-specific effects. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(1):121–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pearce CL, Hirschhorn JN, Wu AH, et al. Clarifying the PROGINS allele association in ovarian and breast cancer risk: a haplotype-based analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(1):51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pooley KA, Healey CS, Smith PL, et al. Association of the progesterone receptor gene with breast cancer risk: a single-nucleotide polymorphism tagging approach. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(4):675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ralph DA, Zhao LP, Aston CE, et al. Age-specific association of steroid hormone pathway gene polymorphisms with breast cancer risk. Cancer. 2007;109(10):1940–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rebbeck TR, Troxel AB, Norman S, et al. Pharmacogenetic modulation of combined hormone replacement therapy by progesterone-metabolism genotypes in postmenopausal breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(12):1392–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Reding KW, Li CI, Weiss NS, et al. Genetic variation in the progesterone receptor and metabolism pathways and hormone therapy in relation to breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(10):1241–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Romano A, Lindsey PJ, Fischer DC, et al. Two functionally relevant polymorphisms in the human progesterone receptor gene (+331 G/A and progins) and the predisposition for breast and/or ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101(2):287–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Romano A, Baars M, Martens H, et al. Impact of two functional progesterone receptor polymorphisms (PRP): +331G/A and PROGINS on the cancer risks in familial breast/ovarian cancer. Open Cancer J. 2007;1(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Runnebaum IB, Wang-Gohrke S, Vesprini D, et al. Progesterone receptor variant increases ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers who were never exposed to oral contraceptives. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11(7):635–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sadia S, Shaikh RS, Tariq N, Kausar T. Analysis of P4 receptors polymorphisms in the development of breast cancer: a study of Southern Punjab (Pakistan). Pure Appl Biol. 2022;11(3):181–190. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sangrajrang S, Sato Y, Sakamoto H, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of estrogen metabolizing enzyme and breast cancer risk in Thai women. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(4):837–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Spurdle AB, Hopper JL, Chen X, et al. The progesterone receptor exon 4 Val660Leu G/T polymorphism and risk of breast cancer in Australian women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(5):439–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Surekha D, Sailaja K, Nageswararao D, Raghunadharao D, Vishnupriya S. Lack of influence of PROGIN polymorphism in breast cancer development and progression. J Cell Tissue Res. 2009;9(3):1995–1998. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wang-Gohrke S, Chang-Claude J, Becher H, Kieback DG, Runnebaum IB. Progesterone receptor gene polymorphism is associated with decreased risk for breast cancer by age 50. Cancer Res. 2000;60(9):2348–2350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Jin YL, Shen YP, Chen JL, et al. A case-control study on the associations of ER codon 325 and PR +331G/A with the risk of breast cancer. Tumor. 2008;28(10):859–863. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Linhares JJ, Silva I, Souza N, Noronha EC, Ferraro O, Baracat FF. Polymorphism in genes of the progesterone receptor (PROGINS) in women with breast cancer: a case-control study. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2005;27(8):473–478. [Google Scholar]

- 78. De Vivo I, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ. A functional polymorphism in the progesterone receptor gene is associated with an increase in breast cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2003;63(17):5236–5238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gold B, Kalush F, Bergeron J, et al. Estrogen receptor genotypes and haplotypes associated with breast cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2004;64(24):8891–8900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rockwell LC, Rowe EJ, Arnson K, et al. Worldwide distribution of allelic variation at the progesterone receptor locus and the incidence of female reproductive cancers. Am J Hum Biol. 2012;24(1):42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hertz DL, Henry NL, Kidwell KM, et al. ESR1 And PGR polymorphisms are associated with estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in breast tumors. Physiol Genomics. 2016;48(9):688–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Giacomazzi J, Aguiar E, Palmero EI, et al. Prevalence of ERalpha-397 PvuII C/T, ERalpha-351 XbaI A/G and PGR PROGINS polymorphisms in Brazilian breast cancer-unaffected women. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2012;45(10):891–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Chambo D, Kemp C, Costa AM, Souza NC, Guerreiro da Silva ID. Polymorphism in CYP17, GSTM1 and the progesterone receptor genes and its relationship with mammographic density. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2009;42(4):323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Qi X-L, Yao J, Zhang Y. No association between the progesterone receptor gene polymorphism (+331G/A) and the risk of breast cancer: an updated meta-analysis. BMC Med Genet. 2017;18(1):123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Yao J, Qi X-L, Zhang Y. The Alu-insertion progesterone receptor gene polymorphism is not associated with breast cancer: a meta-analysis. BMC Med Genet. 2018;19(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Chaudhary S, Panda AK, Mishra DR, Mishra SK. Association of +331G/A PgR polymorphism with susceptibility to female reproductive cancer: evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Yang DS, Sung HJ, Woo OH, et al. Association of a progesterone receptor gene +331 G/A polymorphism with breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;196(2):194–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]