Abstract

The use of oncolytic viruses (OVs) and adoptive cell therapies (ACT) have independently emerged as promising approaches for cancer immunotherapy. More recently, the combination of such agents to obtain a synergistic anticancer effect has gained attention, particularly in solid tumors, where immune-suppressive barriers of the microenvironment remain a challenge for desirable therapeutic efficacy. While adoptive cell monotherapies may be restricted by an immunologically cold or suppressive tumor microenvironment (TME), OVs can serve to prime the TME by eliciting a wave of cancer-specific immunogenic cell death and inducing enhanced antitumor immunity. While OV/ACT synergy is an attractive approach, immune-suppressive barriers remain, and methods should be considered to optimize approaches for such combination therapy. In this review, we summarize current approaches that aim to overcome these barriers to enable optimal synergistic antitumor effects.

Keywords: oncolytic virotherapy, adoptive cellular therapy, CAR-T, NK, CAR NK, tumor microenvironment

Graphical abstract

Cripe and colleagues summarize efforts by investigators to better enable antitumor effects of cellular therapies for solid tumors by combining them with oncolytic viruses. A detailed understanding of the preclinical findings should help investigators develop strategies to leverage combinations of these types of therapies in the clinic.

Introduction

Significant advancements have been made in the field of cancer immunotherapy. Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) has been a great technological advancement for leukemias, lymphomas, and myeloma, but there have not been any significant approvals so far in patients with more conventional solid tumors, likely due to a number of barriers in the solid tumor microenvironment (TME). Oncolytic virotherapy has emerged as a promising strategy for specifically infecting and lysing cancer cells, as well as eliciting antitumor immune responses and modulating the TME.1,2,3 As such, these two modalities may be complementary for solid tumors. Herein we review the state of the art involving the combination of ACT with oncolytic virotherapy and comprehensively outline strategies with the potential to overcome prospective challenges, particularly in solid tumors.

Adoptive cellular therapies

ACT monotherapy is effective for bone marrow-derived cancers

Apart from the early dendritic cell therapy Provenge for prostate cancer approved over a decade ago, all of the other FDA approvals of ACT have been for hematopoietic cancers (Table 1). Based on our search of www.clinicaltrials.gov, ACT is actively being investigated in over 200 clinical trials. To give the reader a sense of the breadth and scope of those trials, we chose representative active or completed trials to highlight that involve various different types of adoptive cells alone, not in combination with other biological therapies (Table 2). Promising ACTs more recently under investigation include chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells, T cell receptor (TCR) T cells, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), and both unmodified and modified/expanded natural killer (NK) cells. Thus far, success of cellular therapy as measured by FDA approval has been limited to CD19- and BCMA-targeting CAR-T cells in the setting of hematological malignancies.

Table 1.

FDA-approved adoptive cell therapies for cancers

| Product | Description | Indication/use | Date approved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provenge | PAP-GMCSF-activated CD54+ cells | hormone refractory prostate cancer | Apr 29, 2010 |

| Kymriah | CD19-directed CAR-T cells | refractory B cell precursor ALL (pediatric), refractory after two lines of systemic therapy: DLBCL, high-grade BCL | Aug 30, 2017 |

| Yescarta | CD19-directed CAR-T cells | refractory after two lines of systemic therapy: DLBCL, PMLBCL, high-grade BCL | Oct 18, 2017 |

| Tecartus | CD19-directed CAR-T cells | refractory MCL, refractory B cell precursor ALL | Jul 24, 2020 |

| Breyanzi | CD19-directed CAR-T cells | DLBCL, high-grade BCL, PMLBCL, follicular lymphoma grade 3B | Feb 5, 2021 |

| Abecma | BCMA-directed CAR-T cells | relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma | Mar 27, 2021 |

| Carvykti | BCMA-directed CAR-T cells | relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma after four or more prior lines of therapy | Feb 28, 2022 |

DLBCL, diffuse large B cell lymphoma; BCL, B cell lymphoma; PMLBCL, primary mediastinal large B cell lymphoma; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma.

Table 2.

List of selected ongoing clinical trials investigating the use of adoptive cell monotherapy

| Biological agent | Indication | Status | Sponsor | Trial ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LN-144 (Lifileucel, autologous TILs, followed by IL-2) | metastatic melanoma | active, phase II | Iovance Biotherapeutics | NCT02360579 |

| LN-145/LN-145-S1, autologous TILs, followed by IL-2) | squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck | active, phase II | Iovance Biotherapeutics | NCT03083873 |

| MC2 (MAGE-C2/HLA-A2) TCR T cells | melanoma, head and neck cancer | recruiting, phase I/II | Erasmus Medical Center | NCT04729543 |

| huMNC2-CAR44 T cells, autologous | metastatic breast cancer | recruiting, phase I | Minerva Biotechnologies | NCT04020575 |

| HER2/EGFRt-CAR-T cells, autologous | CNS tumors | recruiting, phase I | Seattle Children’s Hospital | NCT03500991 |

| MOv19-BBz CAR-T cells | ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, primary peritoneal carcinoma | recruiting, phase I | University of Pennsylvania | NCT03585764 |

| NKX019, allogeneic CD19-CAR NK cells | CD19+ B cell malignancies | recruiting, phase I | Nkarta | NCT05020678 |

| IKDCs (interferon-producing killer dendritic cells), autologous | neoplasm metastasis | completed, phase I | National Defense Medical Center, Taiwan | NCT02661685 |

ACT monotherapy has shown limited efficacy for solid tumors

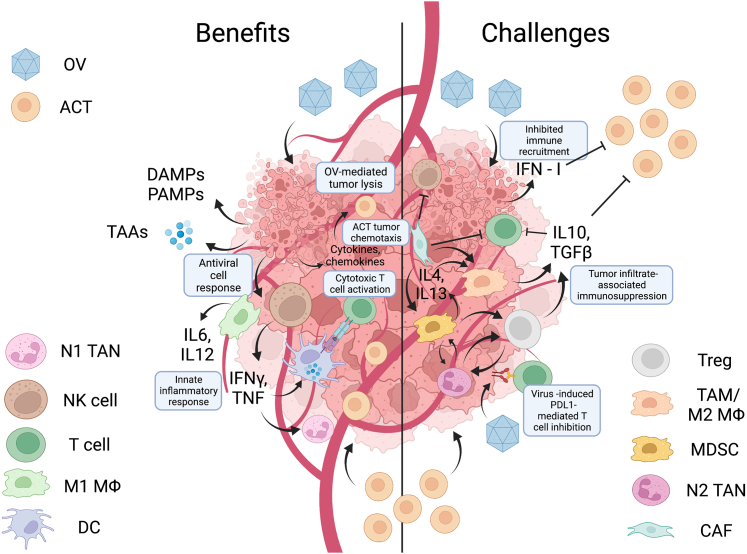

Clinical success of ACTs has largely been limited to hematological cancers likely because solid tumors present a number of distinct barriers. Solid tumors have aberrant vascularity as well as complex, dense extracellular matrix (ECM) that potentially limit physical access of blood cells to tumor cells. Furthermore, there are many immunosuppressive factors within the TME.4,5 Often, immunosuppressive cells such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), regulatory T cells (Tregs), tumor-associated neutrophils, and cancer-associated fibroblasts are adopted by the cancer to maintain immunosuppressive signals and generate physical barriers that mitigate antitumor cellular activity (Figure 1). While next-generation cell therapies are engineered to resist some such immunosuppressive signals such as transforming growth factor β (TGFβ)6 and to express ECM-degrading enzymes,7 immunologically cold tumors and distant metastases lack the necessary chemokines to recruit adoptively transferred cells, further constricting ACT effects. Additionally, solid tumors present a paucity of tumor-selective CAR targets, in which target antigens are both specific to and homogeneously expressed on the tumor cells (see review8). This heterogeneity places a limitation on CAR approaches, as treatment may initially deplete antigen-positive cells and contribute to antigen-negative relapse.9 When considering the setting of combination therapies, understanding potential pitfalls in the dimension of ACT alone is critical in the design of therapies to optimize both safety and efficacy.

Figure 1.

Benefits and challenges of combining oncolytic virotherapies with cellular therapies

Oncolytic viruses have been shown to modify the imunnosuppressive tumor microenvironment in many different ways that might enhance the efficacy of cellular therapies, including the production of immune cell chemokines to improve tumor trafficking as well as the induction of proinflammatory cytokines. Some effects may inhibit the function of cell therapies, however, such as the induction of immune checkpoint expression, the recruitment of more myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and the production of immunosuppressive cytokines. Depending on the timing of the two therapies, type I interferons produced by the virus can also inhibit adoptively transferred immune cells.

Oncolytic virotherapy

Oncolytic virotherapy as a single agent shows moderate efficacy

The first FDA approval of an oncolytic virus (OV) for cancer was IMLYGIC in October 2015, a modified herpesvirus for treatment of patients with relapsed melanoma, following China’s first SDFA approval of Oncorine (H101) for head and neck cancer in November 2005. More recently in 2021, a different oncolytic herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV) (G47Δ; teserpaturev) was approved in Japan for the treatment of patients with brain tumors. Despite these advances, given the large number of different viruses that have been in clinical trials over the past few decades (Table 3), the relative rate of approvals has been quite low. While the reasons underlying the failures so far are multifactorial, in general OVs as single agents have been less efficacious in humans than in animal models, suggesting they might work best in combination with other therapies, particularly with cellular therapies.

Table 3.

List of selected ongoing clinical trials investigating the use of OV monotherapy

| Biological agent | Indication | Status | Sponsor | Trial ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad5-DNX-2401 (adenovirus) | central nervous system tumors | recruiting, phase I | MD Anderson Cancer Center | NCT03896568 |

| LOAd703 (adenovirus 5/35 encoding TMZ-CD40L and 41BBL) | various carcinomas | recruiting, phase I/II | Lokon Pharma AB | NCT03225989 |

| L-IFN (adenovirus encoding IFN) | various carcinomas | recruiting, phase I | Shanghai Yuansong Biotechnology | NCT05180851 |

| NG-641 (adenovirus encoding CXCL9, CXCL10, IFNa, and FAP-TAc antibody) | metastatic cancer | recruiting, phase I | PsiOxus Therapeutics | NCT04053283 |

| C134 (HSV-1) | central nervous system tumors | recruiting, phase I | University of Alabama | NCT03657576 |

| RP1 (HSV-1) | various carcinomas and melanoma | recruiting, phase I/II | Replimune | NCT04349436 |

| VG161 (HSV-1 encoding IL12/15-PDL1B) | advanced malignant solid tumor | recruiting, phase I | CNBG-Virogin Biotech (Shanghai) | NCT04758897 |

| OH2 (HSV-2) | central nervous system tumors | recruiting, phase I/II | Wuhan Binhui Biotechnology | NCT05235074 |

| GL-ONC1 (vaccinia virus) | advanced solid tumors | completed, phase I | Genelux | NCT00794131 |

| ASP9801 (vaccinia virus encoding IL-7, IL-12) | advanced solid tumors | recruiting, phase I | Astellas Pharma Global Development | NCT03954067 |

| Reolysin (reovirus) | various sarcomas | completed, phase II | Oncolytics Biotech | NCT00503295 |

| MV-s-NAP (measles virus encoding H. pylori neutrophil activating protein) | advanced breast cancer | recruiting, phase I | Mayo Clinic | NCT04521764 |

Opportunities for combining OVs with ACTs

OVs have key features to reduce the immunosuppression within the tumor microenvironment and enable an increased immune-cellular response

OVs have recently been recognized for their potential to enhance ACT. They have the capacity to specifically lyse cancer cells, which contributes to immunogenic cell death via release of damage-associated molecular patterns, pathogen-associated molecular patterns, and novel tumor-associated antigens, facilitating antiviral and antitumor responses.2 In the context of combination therapy, OVs elicit a wave of tumor cell lysis that liberates potential immunogenic tumor-associated antigens, which can result in “epitope spread” wherein endogenous immunity is sensitized to non-ACT target antigens, minimizing the possibility that a tumor can escape all potential epitopes, even if it manages to lose the target of the adoptively transferred T cells. OVs also change a previously cold TME to one that actively recruits effector immune cells, thus likely becoming more favorable for a host immune and an ACT antitumor response. OV-induced responses include induction of interferon (IFN) and IFN-inducible chemokines, promoting influx of T cells, NK cells, and dendritic cells to initiate a proinflammatory environment (see review10). Stimulation of pathogen recognition receptors not only drives novel chemokine production to promote host-mediated clearance of virus-infected cancer cells, but it concomitantly provides beneficial recruitment of novel immune cells. Additionally, OV-induced neovascularization of the TME11 may aid in delivery of ACTs to both primary tumor and subsequent metastases, though some OVs paradoxically decrease vascular access.12

Challenges to combining OV and ACT for solid tumor therapy

While OV therapy provides potential benefits in enhancing ACT, existing challenges hinder the extent to which OVs can act to provide optimal therapeutic responses in the context of combination therapy. As is a similar barrier to ACT, TME-secreted ECM elements physically prevent ideal OV replication and spread,13 restricting OV access to pockets within the tumor bed. Tumor sites unperturbed by OVs may prevail and persist to recruit infiltrating immune cells to sustain immunosuppressive signals, mitigating ideal ACT performance. OV-mediated upregulation of programmed death-ligand 1 on cancer cells has been observed,14,15,16 which can contribute to immune subversion of ACT. The induction of type I interferons by virus infection, particularly when expressed as a viral transgene, was shown in one study to paradoxically diminish CAR-T antitumor effects by inducing T cell apoptosis and inducing expression of inhibitory receptors, which could be circumvented by knocking out the IFNAR receptor on the CAR-T cells.17 Furthermore, repetitive administration of OVs may have mitigated efficacy via timely neutralization from acquired antiviral immunity, calling for strategies that can more efficiently subvert the TME to optimize synergy of combination immunotherapies in solid tumors. In addition, ACT itself may limit the spread of OV, requiring carefully timed sequential administration to achieve the best synergy.18

While significant work has been done to characterize strengths of OVs and ACTs against cancers, more recent studies have explored the potential of synergizing these two cutting-edge approaches in a multi-faceted approach to enhance therapeutic efficacy beyond the current potential of either approach alone. Despite the field being nascent, efforts to enhance the potential of such combinations are already underway. Investigations of this combination are in early stages, with numerous preclinical investigations published (Table 4) and four phase I clinical trials launched (Table 5).

Table 4.

List of preclinical studies investigating the use of combination OV and adoptive cell therapy

| Oncolytic virus | Transgene(s) | Cells | Cancer type(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus (Ad5Delta24) | CCL5, IL-15 | GD2-CAR-T | neuroblastoma | Nishio (2014)19 |

| Vaccinia virus (vvDD) and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSVDeltaM51) | N/A | HER2-CAR-T (loaded with the OV) | breast cancer | VanSeggelen (2015)20 |

| HSV-1 (oHSV-1) | N/A | EGFR-CAR NK | breast cancer brain metastases | Chen (2016)21 |

| HSV-1 (oHSV-1) | N/A | NK cells | glioblastoma | Yoo (2016)22 |

| Adenovirus (Ad5/3Delta24) | IL12, anti-PDL1 expressed by co-injected helper Ad | HER2-CAR-T | head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Rosewell Shaw (2017)23 |

| Adenovirus (Ad5/3Delta24) | Anti-PDL1 expressed by co-injected helper Ad | HER2-CAR-T | prostate, squamous cell carcinoma | Tanoue (2017)24 |

| Adenovirus (ICOVIR15K) | EGFRxCD3 bispecific | folate receptor-CAR-T | pancreatic ductal carcinoma/colorectal carcinoma | Wing (2018)25 |

| Adenovirus (Ad5/3E2FDelta24) | TNFα, IL-12 | mesothelin-CAR-T | pancreatic ductal carcinoma | Watanabe (2018)26 |

| Vaccinia virus (vvDD) | CXCL-11 | mesothelin-CAR-T | lung cancer | Moon (2018)27 |

| Chimeric vaccinia virus (CF33) | truncated CD19 | CD19-CAR | breast cancer | Park (2019)28 |

| Vesicular stomatitis virus | mIFNβ | mEGFRvIII | murine melanoma | Evgin (2020)17 |

| Vaccinia Western Reserve | CCL5 | CCR5-NK | various carcinomas | Li (2020)29 |

| Adenovirus (Ad5/3Delta24) | CD44v6xCD3 bispecific, IL-12, anti-PDL1 expressed by co-injected helper Ad | HER2-CAR-T | pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma | Porter (2020)30 |

| Adenovirus (rAd.sT) | TGFb decoy | mesothelin-CAR-T | breast cancer | Li (2020)31 |

| Vaccinia virus | CD19 | CD19-CAR-T | Melanoma | Aalipour (2020)32 |

| Adenovirus | CD19 tag | CD19-CAR-T | liver cancer | Tang (2020)33 |

| Adenovirus (Ad5/3Delta24) | IL12, anti-PDL1 expressed by co-injected helper Ad | HER2-CAR-T | pancreatic cancer | Rosewell Shaw (2021)34 |

| Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSVDeltaM51) | IL-15 | NKT | pancreatic cancer | Nelson (2022)35 |

| HSV-1 (G47Δ) | N/A | Lp2-CAR-T | Glioblastoma | Chalise (2022)36 |

| Vesicular stomatitis virus, reovirus | mIFNβ (VSV) | mEGFRvIII | murine melanoma, glioma | Evgin (2022)37 |

| HSV-1 | OX40L, IL-12 | TILs | colon cancer, pancreatic cancer | Ye (2022)38 |

Table 5.

Combination OV and adoptive cell clinical trials for cancers

| Biological agent | Combination | Indication | Status | Sponsor | Trial ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TILT-123 (adenovirus coding TNFα and IL2) | adoptive cell therapy with TILs | metastatic melanoma | recruiting, phase I | TILT Biotherapeutics | NCT04217473 |

| CAdVEC (binary oncolytic adenovirus) | HER2-specific CAR-T cells | advanced solid tumors | recruiting, phase I | Baylor College of Medicine | NCT03740256 |

| VCN-01 (oncolytic adenovirus expressing hyaluronidase) | mesothelin-specific CAR-T cells | pancreatic cancer, serous ovarian cancer | recruiting, phase I | University of Pennsylvania | NCT05057715 |

| OVV-01 (oncolytic vaccinia virus) | trained immunity NK cells IBR900 | advanced solid tumors including lymphoma | terminated | Beijing Boren Hospital | NCT05271279 |

Strategies to improve the synergy between OVs and ACTs

OV-encoded immune-promoting transgenes

One approach used to enhance ACT involves adjuvant administration of recombinant chemokines and cytokines, which have been shown to enhance therapeutic response via improved intratumoral recruitment and activation of adoptively transferred cells (see review39). Examples include the expression from the virus (or a co-injected helper virus) of chemokines such as CCL5, IL12, IL15, and CXCL11 and/or an anti-PDL1 antibody (Table 4). While such activating signals can provide beneficial responses locally, circulating levels can also elicit toxicity. Because they are often administered intratumorally and their replication is generally restricted to cancer cells, OVs can maximize the potential for localized expression of cytokines, chemokines, and/or immune checkpoint inhibitors to tumor sites while minimizing systemic levels to a clinically safe range. With the exception of the previously mentioned expression of type I interferon from the virus, most OVs expressing immunogenic transgenes as monotherapy have demonstrated superior efficacy relative to their “unarmed” counterparts (Table 4), providing groundwork for investigational use for optimizing ACT. One phase I clinical trial investigating the combination of OV + adoptive T cell therapy involves the use of TILT-123, an adenovirus-encoding tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-2 (IL-2), in association with T cell therapy using TILs in patients diagnosed with metastatic melanoma.40

Viral boosting of adoptively transferred cells

A current challenge of enhancing the potential of ACT lies in the limited ability of adoptively transferred cells to specifically recognize cancer cells. While CAR-based approaches are beneficial in some cancers, they are limited in efficacy relative to homogeneous expression and specificity of CAR targets, particularly in solid tumors. One strategy explores the advantage of tumor-selectivity that OVs provide in order to further enhance antitumor efficacy of ACT. By first loading CAR-T cells with OV in vitro, Evgin et al. stimulated in vivo expansion of CAR-T cells at the site of the tumor relative to unloaded CAR-T cells, and this strategy was associated with prolonged survival in several mouse models.37 Furthermore, systemic boosting via additional administration of OV in vivo, aimed to propagate activation of adoptively transferred cells against viral or virally encoded epitopes at tumor sites, resulted in >80% cures in mice. This evidence provides rationale for co-administration of ACT cells with pre-loaded OV as well as systemic boosting as a means to promote specific immune activation status at tumor sites.

Modulating the tumor microenvironment via targeting suppressive host immune cells

A major proposed barrier to reaching the potential of most immunotherapies is thought to be the immunosuppressive microenvironment maintained in solid tumors. While mechanisms are not fully understood as to how immune-suppressive cells such as MDSCs, TAMs, and Tregs are sustained in TMEs, inhibition or depletion of such cells in some cases results in impaired tumor growth and induction of antitumor responses.41,42,43,44 Furthermore, targeted depletion of MDSCs and TAMs results in enhanced effects of OV and ACT therapies independently45,46 Therefore, although speculative, it stands to reason that targeting these immunosuppressive cells in the TME may enhance the combination of OV with ACT, but there are no data yet reported to support that supposition. FDA-approved drugs that reduce or deplete MDSCs and TAMs such as trabectedin, doxorubicin, gemcitabine, lurbinectedin, and indoximod may be useful in this endeavor. Additionally, Goswami et al. recently highlighted small-molecule inhibitors targeting pro-tumor myeloid mechanisms that have demonstrated antitumor efficacy, providing rational combination strategies for solid tumors.47 Overall, targeted depletion/functional modulation of such cells has a potential to enhance antitumor response in the setting of OV + ACT.

Potentially misleading immunologic modeling

Currently, a major challenge in developmental therapeutics, especially for biologic therapies, is highlighted by their suboptimal success in clinical trials after encouraging results in animal models. One explanation may be that many OVs under investigation differ in their infectivity between species. As a result, not only are the direct lytic effects not seen (or underappreciated) in some animal models, but the effects of a robust infection on immune stimulation are not recapitulated. For example, in our experience, recovery of infectious virus particles following intratumor injection of a variety of different oncolytic human herpes simplex type 1 viruses into mouse tumors (even when implanted into immunodeficient mice) either does not amplify at all or increases only 1–2 logs at best, depending on the model, whereas the same viruses increase 4–5 logs in human xenograft tumors. Thus, depending on the virus and the model, use of fully immune competent models is limited in their ability to emulate the effects of OV infection on ACT activity and may underestimate effects that might be result from a robust virus replication in humans. On the other side, the use of xenografts in immunodeficient mice does allow study of the immunologic response to viruses, and may over estimate the oncolytic effects as the infection is not constrained by immunity. These concerns may be mitigated somewhat by the use of human tumor xenografts in bone marrow humanized mice as was used in at least one study,34 though immune cells and tumors in that setting expressed mismatched major histocompatibility complex, which could also artificially impact the results.

Another major area of disconnect that might underly differences between animal models and patient outcomes lies in the immunological differences between humans and preclinical models. As highlighted by Mestas and Hughes,48 proportional differences in immune cell subsets, toll-like receptor differences, and varying levels of cytokine responses have been noted between humans and mice. Furthermore, many mouse cytokines and chemokines do not cross-react with their human counterparts and vice versa. For example, while type I interferons are potent activators of antiviral and immunoregulatory responses,37 no appreciable cross-reactivity is seen between human and mouse type I interferons.48 In human xenograft models, this alone would detract from biologically relevant cross-talk—resulting in lack of innate antiviral responses—potentially providing an overestimate of true viral permissivity by allowing an “artificially” extended viral spread and reduced antitumor immune response relative to the therapeutic response that would be found in human patients. Thus, in the ongoing investigation for biological therapeutic approaches, it may be critical to implement models on various axes of interaction to more closely mimic those that occur in human patients. While current advancements of such humanization methods largely include immune cell engraftment, as highlighted in a recent review,49 the use of supplementing human versions of chemokines and cytokines expressed from an OV within a humanized model may also uniquely serve to mimic responses seen in humans.

Conclusions

There are numerous biologic rationales for combining adoptive cellular therapy with oncolytic virotherapy, and preclinical efficacy looks promising in some studies but is cross-inhibitory in others. Many unknowns still need to be investigated, however, including relative dosing, timing, and engineering of each to overcome mitigating factors when these two promising therapies are combined. Better preclinical models that more accurately recapitulate complex human immune cell interactions are needed in order to improve our success rates in clinical translation. Focusing on these challenges will be pivotal for fully realizing the potential of ACT + OV combinations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Moonshot Award U54-CA232561-01A1. The figure was drawn using biorender.com.

Author contributions

J.A.M., C.Y.C., M.A.C., and T.P.C. wrote the manuscript, and K.C., D.A.L., and T.P.C. edited the manuscript. J.A.M. drew the figure.

Declaration of interests

D.A.L. is an inventor on patents in cellular therapy and has licensed related technology to Sanofi. The other authors are inventors on patents or pending patents regarding oncolytic virotherapy. T.P.C. has licensed one such OV technology to Vironexis Biotherapeutics, Inc.

References

- 1.Lemos de Matos A., Franco L.S., McFadden G. Oncolytic viruses and the immune system: the dynamic duo. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020;17:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahman M.M., McFadden G. Oncolytic viruses: newest frontier for cancer immunotherapy. Cancers. 2021;13:5452. doi: 10.3390/cancers13215452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo Z.S., Liu Z., Kowalsky S., Feist M., Kalinski P., Lu B., Storkus W.J., Bartlett D.L. Oncolytic immunotherapy: conceptual evolution, current strategies, and future perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:555. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munn D.H., Bronte V. Immune suppressive mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2016;39:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henke E., Nandigama R., Ergün S. Extracellular matrix in the tumor microenvironment and its impact on cancer therapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019;6:160. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foltz J.A., Moseman J.E., Thakkar A., Chakravarti N., Lee D.A. TGFbeta imprinting during activation promotes natural killer cell cytokine hypersecretion. Cancers. 2018;10:423. doi: 10.3390/cancers10110423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caruana I., Savoldo B., Hoyos V., Weber G., Liu H., Kim E.S., Ittmann M.M., Marchetti D., Dotti G. Heparanase promotes tumor infiltration and antitumor activity of CAR-redirected T lymphocytes. Nat. Med. 2015;21:524–529. doi: 10.1038/nm.3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z., Chen W., Zhang X., Cai Z., Huang W. A long way to the battlefront: CAR T cell therapy against solid cancers. J. Cancer. 2019;10:3112–3123. doi: 10.7150/jca.30406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kochenderfer J.N., Somerville R.P.T., Lu T., Shi V., Bot A., Rossi J., Xue A., Goff S.L., Yang J.C., Sherry R.M., et al. Lymphoma remissions caused by anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells are associated with high serum interleukin-15 levels. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:1803–1813. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wojton J., Kaur B. Impact of tumor microenvironment on oncolytic viral therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aghi M., Cohen K.S., Klein R.J., Scadden D.T., Chiocca E.A. Tumor stromal-derived factor-1 recruits vascular progenitors to mitotic neovasculature, where microenvironment influences their differentiated phenotypes. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9054–9064. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breitbach C.J., Paterson J.M., Lemay C.G., Falls T.J., McGuire A., Parato K.A., Stojdl D.F., Daneshmand M., Speth K., Kirn D., et al. Targeted inflammation during oncolytic virus therapy severely compromises tumor blood flow. Mol. Ther. 2007;15:1686–1693. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKee T.D., Grandi P., Mok W., Alexandrakis G., Insin N., Zimmer J.P., Bawendi M.G., Boucher Y., Breakefield X.O., Jain R.K. Degradation of fibrillar collagen in a human melanoma xenograft improves the efficacy of an oncolytic herpes simplex virus vector. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2509–2513. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samson A., Scott K.J., Taggart D., West E.J., Wilson E., Nuovo G.J., Thomson S., Corns R., Mathew R.K., Fuller M.J., et al. Intravenous delivery of oncolytic reovirus to brain tumor patients immunologically primes for subsequent checkpoint blockade. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018;10:eaam7577. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam7577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speranza M.C., Passaro C., Ricklefs F., Kasai K., Klein S.R., Nakashima H., Kaufmann J.K., Ahmed A.K., Nowicki M.O., Obi P., et al. Preclinical investigation of combined gene-mediated cytotoxic immunotherapy and immune checkpoint blockade in glioblastoma. Neuro. Oncol. 2018;20:225–235. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zamarin D., Ricca J.M., Sadekova S., Oseledchyk A., Yu Y., Blumenschein W.M., Wong J., Gigoux M., Merghoub T., Wolchok J.D. PD-L1 in tumor microenvironment mediates resistance to oncolytic immunotherapy. J. Clin. Invest. 2018;128:5184. doi: 10.1172/JCI125039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evgin L., Huff A.L., Wongthida P., Thompson J., Kottke T., Tonne J., Schuelke M., Ayasoufi K., Driscoll C.B., Shim K.G., et al. Oncolytic virus-derived type I interferon restricts CAR T cell therapy. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3187. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17011-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvarez-Breckenridge C.A., Yu J., Price R., Wojton J., Pradarelli J., Mao H., Wei M., Wang Y., He S., Hardcastle J., et al. NK cells impede glioblastoma virotherapy through NKp30 and NKp46 natural cytotoxicity receptors. Nat. Med. 2012;18:1827–1834. doi: 10.1038/nm.3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishio N., Diaconu I., Liu H., Cerullo V., Caruana I., Hoyos V., Bouchier-Hayes L., Savoldo B., Dotti G. Armed oncolytic virus enhances immune functions of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5195–5205. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.VanSeggelen H., Tantalo D.G., Afsahi A., Hammill J.A., Bramson J.L. Chimeric antigen receptor-engineered T cells as oncolytic virus carriers. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2015;2:15014. doi: 10.1038/mto.2015.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X., Han J., Chu J., Zhang L., Zhang J., Chen C., Chen L., Wang Y., Wang H., Yi L., et al. A combinational therapy of EGFR-CAR NK cells and oncolytic herpes simplex virus 1 for breast cancer brain metastases. Oncotarget. 2016;7:27764–27777. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoo J.Y., Jaime-Ramirez A.C., Bolyard C., Dai H., Nallanagulagari T., Wojton J., Hurwitz B.S., Relation T., Lee T.J., Lotze M.T., et al. Bortezomib treatment sensitizes oncolytic HSV-1-Treated tumors to NK cell immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;22:5265–5276. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosewell Shaw A., Porter C.E., Watanabe N., Tanoue K., Sikora A., Gottschalk S., Brenner M.K., Suzuki M. Adenovirotherapy delivering cytokine and checkpoint inhibitor augments CAR T cells against metastatic head and neck cancer. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:2440–2451. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanoue K., Rosewell Shaw A., Watanabe N., Porter C., Rana B., Gottschalk S., Brenner M., Suzuki M. Armed oncolytic adenovirus-expressing PD-L1 mini-body enhances antitumor effects of chimeric antigen receptor T cells in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2040–2051. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wing A., Fajardo C.A., Posey A.D., Jr., Shaw C., Da T., Young R.M., Alemany R., June C.H., Guedan S. Improving CART-cell therapy of solid tumors with oncolytic virus-driven production of a bispecific T-cell engager. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018;6:605–616. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watanabe K., Luo Y., Da T., Guedan S., Ruella M., Scholler J., Keith B., Young R.M., Engels B., Sorsa S., et al. Pancreatic cancer therapy with combined mesothelin-redirected chimeric antigen receptor T cells and cytokine-armed oncolytic adenoviruses. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e99573. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.99573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moon E.K., Wang L.C.S., Bekdache K., Lynn R.C., Lo A., Thorne S.H., Albelda S.M. Intra-tumoral delivery of CXCL11 via a vaccinia virus, but not by modified T cells, enhances the efficacy of adoptive T cell therapy and vaccines. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1395997. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1395997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park A.K., Fong Y., Kim S.I., Yang J., Murad J.P., Lu J., Jeang B., Chang W.C., Chen N.G., Thomas S.H., et al. Effective combination immunotherapy using oncolytic viruses to deliver CAR targets to solid tumors. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020;12:eaaz1863. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaz1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F., Sheng Y., Hou W., Sampath P., Byrd D., Thorne S., Zhang Y. CCL5-armed oncolytic virus augments CCR5-engineered NK cell infiltration and antitumor efficiency. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2020;8:e000131. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter C.E., Rosewell Shaw A., Jung Y., Yip T., Castro P.D., Sandulache V.C., Sikora A., Gottschalk S., Ittman M.M., Brenner M.K., Suzuki M. Oncolytic adenovirus armed with BiTE, cytokine, and checkpoint inhibitor enables CAR T cells to control the growth of heterogeneous tumors. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:1251–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y., Xiao F., Zhang A., Zhang D., Nie W., Xu T., Han B., Seth P., Wang H., Yang Y., Wang L. Oncolytic adenovirus targeting TGF-beta enhances anti-tumor responses of mesothelin-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy against breast cancer. Cell. Immunol. 2020;348:104041. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2020.104041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aalipour A., Le Boeuf F., Tang M., Murty S., Simonetta F., Lozano A.X., Shaffer T.M., Bell J.C., Gambhir S.S. Viral delivery of CAR targets to solid tumors enables effective cell therapy. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2020;17:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang X., Li Y., Ma J., Wang X., Zhao W., Hossain M.A., Yang Y. Adenovirus-mediated specific tumor tagging facilitates CAR-T therapy against antigen-mismatched solid tumors. Cancer Lett. 2020;487:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosewell Shaw A., Porter C.E., Yip T., Mah W.C., McKenna M.K., Dysthe M., Jung Y., Parihar R., Brenner M.K., Suzuki M. Oncolytic adeno-immunotherapy modulates the immune system enabling CAR T-cells to cure pancreatic tumors. Commun. Biol. 2021;4:368. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-01914-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson A., Gebremeskel S., Lichty B.D., Johnston B. Natural killer T cell immunotherapy combined with IL-15-expressing oncolytic virotherapy and PD-1 blockade mediates pancreatic tumor regression. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2022;10:e003923. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-003923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chalise L., Kato A., Ohno M., Maeda S., Yamamichi A., Kuramitsu S., Shiina S., Takahashi H., Ozone S., Yamaguchi J., et al. Efficacy of cancer-specific anti-podoplanin CAR-T cells and oncolytic herpes virus G47Delta combination therapy against glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2022;26:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2022.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evgin L., Kottke T., Tonne J., Thompson J., Huff A.L., van Vloten J., Moore M., Michael J., Driscoll C., Pulido J., et al. Oncolytic virus-mediated expansion of dual-specific CAR T cells improves efficacy against solid tumors in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022;14:eabn2231. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abn2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ye K., Li F., Wang R., Cen T., Liu S., Zhao Z., Li R., Xu L., Zhang G., Xu Z., et al. An armed oncolytic virus enhances the efficacy of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy by converting tumors to artificial antigen-presenting cells in situ. Mol. Ther. 2022;30:3658–3676. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Graaf J.F., de Vor L., Fouchier R.A.M., van den Hoogen B.G. Armed oncolytic viruses: a kick-start for anti-tumor immunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2018;41:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGrath K., Dotti G. Combining oncolytic viruses with chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2021;32:150–157. doi: 10.1089/hum.2020.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ries C.H., Cannarile M.A., Hoves S., Benz J., Wartha K., Runza V., Rey-Giraud F., Pradel L.P., Feuerhake F., Klaman I., et al. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages with anti-CSF-1R antibody reveals a strategy for cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:846–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shimizu J., Yamazaki S., Sakaguchi S. Induction of tumor immunity by removing CD25+CD4+ T cells: a common basis between tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 1999;163:5211–5218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Califano J.A., Khan Z., Noonan K.A., Rudraraju L., Zhang Z., Wang H., Goodman S., Gourin C.G., Ha P.K., Fakhry C., et al. Tadalafil augments tumor specific immunity in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:30–38. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weed D.T., Vella J.L., Reis I.M., De la Fuente A.C., Gomez C., Sargi Z., Nazarian R., Califano J., Borrello I., Serafini P. Tadalafil reduces myeloid-derived suppressor cells and regulatory T cells and promotes tumor immunity in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:39–48. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Denton N.L., Chen C.Y., Hutzen B., Currier M.A., Scott T., Nartker B., Leddon J.L., Wang P.Y., Srinivas R., Cassady K.A., et al. Myelolytic treatments enhance oncolytic herpes virotherapy in models of ewing sarcoma by modulating the immune microenvironment. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2018;11:62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez-Garcia A., Lynn R.C., Poussin M., Eiva M.A., Shaw L.C., O'Connor R.S., Minutolo N.G., Casado-Medrano V., Lopez G., Matsuyama T., Powell D.J., Jr. CAR-T cell-mediated depletion of immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages promotes endogenous antitumor immunity and augments adoptive immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:877. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-20893-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goswami S., Anandhan S., Raychaudhuri D., Sharma P. Myeloid cell-targeted therapies for solid tumours. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023;23:106–120. doi: 10.1038/s41577-022-00737-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mestas J., Hughes C.C.W. Of mice and not men: differences between mouse and human immunology. J. Immunol. 2004;172:2731–2738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cogels M.M., Rouas R., Ghanem G.E., Martinive P., Awada A., Van Gestel D., Krayem M. Humanized mice as a valuable pre-clinical model for cancer immunotherapy research. Front. Oncol. 2021;11:784947. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.784947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]