Summary

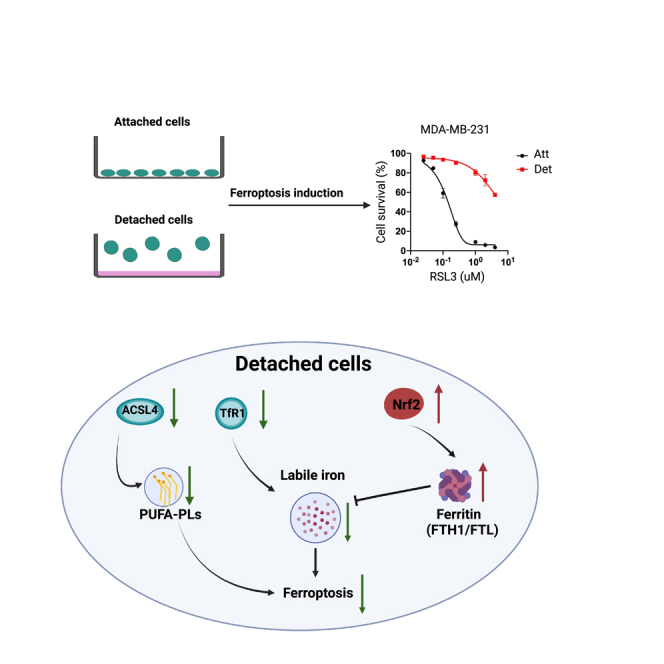

Cancer cells often acquire resistance to cell death programs induced by loss of integrin-mediated attachment to extracellular matrix (ECM). Given that adaptation to ECM-detached conditions can facilitate tumor progression and metastasis, there is significant interest in effective elimination of ECM-detached cancer cells. Here, we find that ECM-detached cells are remarkably resistant to the induction of ferroptosis. Although alterations in membrane lipid content are observed during ECM detachment, it is instead fundamental changes in iron metabolism that underlie resistance of ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis. More specifically, our data demonstrate that levels of free iron are low during ECM detachment because of changes in both iron uptake and iron storage. In addition, we establish that lowering the levels of ferritin sensitizes ECM-detached cells to death by ferroptosis. Taken together, our data suggest that therapeutics designed to kill cancer cells by ferroptosis may be hindered by lack of efficacy toward ECM-detached cells.

Subject areas: Cell biology, Cancer

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

ECM-detached cells are resistant to ferroptosis induction

-

•

Loss of Yap-mediated ACSL4 does not cause ferroptosis resistance during detachment

-

•

ECM detachment causes alterations in iron uptake

-

•

Alterations in NRF2/FTH1 contribute to ferroptosis resistance during ECM detachment

Cell biology; Cancer

Introduction

Mammalian cells often maintain integrin-mediated attachment to the extracellular matrix (ECM) to antagonize cell death programs.1 More specifically, loss of ECM attachment is well known to induce a cell death program termed anoikis, which involves caspase-dependent cell death by apoptosis.2 However, ECM detachment is also well recognized to induce numerous, additional changes that can impact cell viability independent from anoikis.3 These changes include profound alterations in nutrient uptake,4,5 metabolic reprogramming,6,7,8 the induction of mitophagy,9 and the rewiring of signal transduction.10,11,12,13,14,15,16 Given that cancer cells often encounter ECM-detached conditions during tumor progression and metastasis,17 the mechanisms by which cancer cells evade ECM detachment-mediated cell death programs could ultimately serve as targets for the elimination of invasive cancer cells.

Although we (and others) have long been interested in understanding how cancer cells adapt and survive during ECM detachment, less attention has been devoted to attempts to specifically kill cancer cells that have successfully adapted to ECM-detached conditions. In addition to the therapeutic possibilities that could be unveiled by such investigations, understanding the sensitivity (or insensitivity) of ECM-detached cells to extrinsic treatments could also generate important new biological insight. One such avenue that has been explored as a strategy to eliminate cancer cells is the induction of ferroptosis, an iron-dependent, non-apoptotic form of programmed cell death that is characterized by robust lipid peroxidation.18,19,20,21 Sensitivity to cell death by ferroptosis can be regulated by diminished glutathione synthesis owing to impaired cystine uptake,22,23,24,25 alterations in the abundance or activity of the antioxidant selenoprotein glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4),26,27 or alterations in membrane lipid content that favor oxidation.28,29 In addition to these regulatory pathways, recent studies have continued to unveil additional factors that impact the activation or inhibition of ferroptosis.30,31,32,33,34,35 Currently, there is significant interest in the possibility that induction of ferroptosis may be an attractive strategy to kill cancer cells and thus limit tumor progression.36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 However, the sensitivity of ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis induction has not been investigated in detail.

Here, we demonstrate that ECM-detached cells are strikingly resistant to the induction of ferroptosis. This protection from ferroptosis induction extends across multiple cell lines and to both pharmacological and genetic means of ferroptosis activation. ECM-detached cells are well-known to form multicellular aggregates and enhanced cell-cell contacts are linked to alterations in lipid content that cause ferroptosis resistance. However, aggregation-induced changes in membrane lipid content do not underlie ferroptosis resistance during ECM detachment. Instead, we find that ECM-detached cells have low levels of free (redox-active) iron and that addition of excess iron is sufficient to sensitize ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis induction. We also find that iron uptake and iron storage are altered during ECM detachment and that limiting the levels of iron storage proteins can sensitize ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis. Taken together, our results suggest a direct link between ECM detachment and iron metabolism. Strategies that attempt to kill cancer cells through ferroptosis may be hindered as a consequence of this intrinsic resistance during ECM detachment.

Results

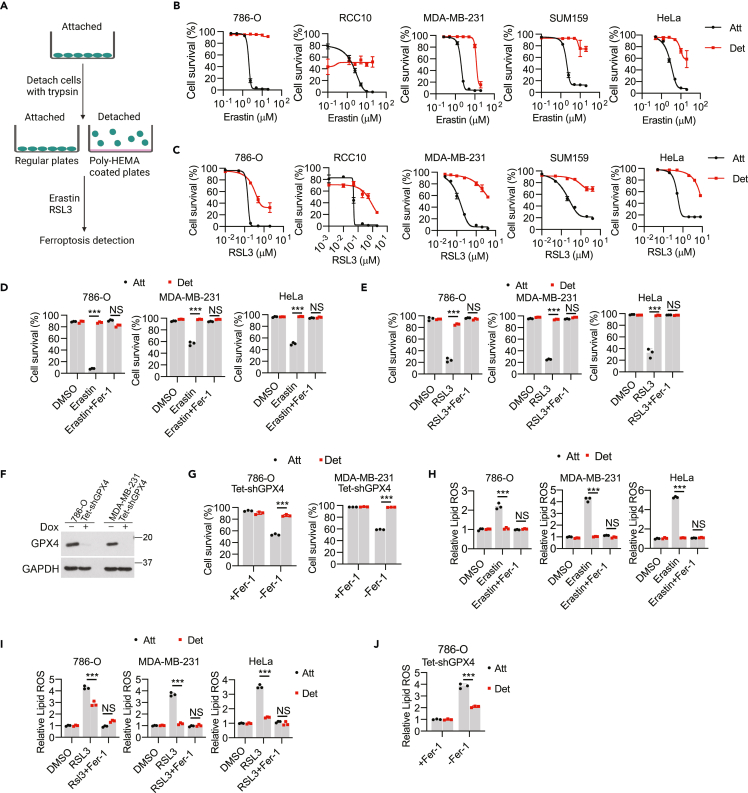

ECM-detached cells are resistant to pharmacological and genetic induction of ferroptosis

To examine the sensitivity of ECM-detached cells to the induction of ferroptosis, we applied an in vitro ECM detachment model by plating cells on poly-(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (poly-HEMA) coated plates (Figure 1A) and induced ferroptosis by treating various cell lines with increasing concentrations of erastin (Figure 1B), which triggers ferroptosis through the inhibition of the system xc− antiporter (xCT).18 We intentionally selected cell lines derived from disparate tissue types to assess whether any observed changes in erastin sensitivity were fundamentally distinct in specific cellular contexts. Of interest, we found that when 786-O, RCC10, MDA-MB-231, SUM159, and HeLa cells were grown in ECM-detached conditions, they were strikingly resistant to erastin-induced cell death (Figures 1B and S1A). The effect of system xc− antiporter inhibition (and consequent ferroptosis induction) can also be achieved by elimination of cystine from the cell culture media.22,23,24,25 Indeed, ECM-detached cells, unlike their ECM-attached counterparts, are resistant to cystine-starvation induced cell death (Figure S1C). We also tested the sensitivity of ECM-detached cells to RSL3, which is known to induce ferroptotic cell death by blocking the activity of GPX4.26,27 Indeed, the capacity of RSL3 to induce cell death is markedly compromised when these cell lines are grown in ECM detachment (Figures 1C and S1B). As expected, treatment with ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1), a well-characterized inhibitor of ferroptosis,18 led to a substantial inhibition of erastin-induced (Figure 1D), RSL3-induced (Figure 1E), and cystine starvation-induced (Figure S1C) cell death in ECM-attached cells. However, the viability of ECM-detached cells treated with these stimuli was not meaningfully altered by Fer-1 treatment. To assess whether the resistance of ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis is reversible, we grew cells in ECM-detached conditions before allowing them to re-attach to the plate. Indeed, the resistance to erastin-induced death acquired during ECM detachment was lost on re-attachment to ECM (Figure S1D).

Figure 1.

ECM-detached cells are resistant to ferroptosis induction

(A) Schematic of ECM detachment model.

(B and C) Survival of various tumor cell lines with erastin treatment for 24 h (B) or RSL3 treatment for 18 h (C).

(D and E) Survival of 786-O, MDA-MB-231, and HeLa cells to erastin (5 μM, 24 h) (D) or RSL3 (0.2 μM, 12 h) (E). Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) was used at 2.5 μM.

(F) Western blot to verify the doxycycline-inducible GPX4 knockdown in 786-O and MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were kept in the medium containing 2.5 μM Fer-1.

(G) Cell survival after 20-h withdrawal of Fer-1.

(H–J) Lipid ROS detection by C11 BODIPY 581/591 staining in erastin (5 μM, 12 h) (H), RSL3 (0.2 μM, 3 h) (I) or Fer-1 withdrawal (5 h) (J) treatments. Fer-1 (2.5 μM) was used to block ferroptosis. ∗∗∗p < 0.001; NS, not significant; two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Data are mean ± SD. Graphs represent data collected from a minimum of three biological replicates and all western blotting experiments were independently repeated a minimum of three times with similar results.

To complement these studies using a genetic method of ferroptosis induction, we utilized cells engineered to express doxycycline-inducible GPX4 shRNA (Figure 1F). These cells grow in the presence of Fer-1 and undergo ferroptosis on removal of Fer-1 from the media.44 Unlike when cells are grown in ECM-attached conditions, Fer-1 withdrawal in cells deficient in GPX4 failed to induce cell death in ECM-detached 786-O or MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 1G). Furthermore, the accumulation of lipid ROS as measured by C11 BODIPY 581/591 in response to erastin (Figure 1H), RSL3 (Figure 1I), cystine starvation (Figure S1E), or GPX4 shRNA (Figure 1J) treatment is blunted when cells are grown in ECM detachment. In addition, lipid ROS accumulation in ECM-detached cells exposed to erastin was restored on re-attachment of ECM-detached cells to the plate (Figure S1F). Importantly, the resistance attained in ECM-detached cells does not extend to more generic oxidative stress as we do not observe differences between ECM-detached and –attached cells in the sensitivity of H2O2 treatment (Figure S1G). In aggregate, these results suggest that cells grown in ECM-detached conditions are resistant to ferroptosis induction by pharmacological and genetic means.

Loss of Yap-mediated ACSL4 does not underlie ferroptosis resistance during ECM detachment

We next sought to assess the molecular mechanism by which ECM-detached cells are resistant to the induction of ferroptosis. Although ECM-detached cells showed reduced cell proliferation evidenced by a decrease of cells that are in S/G2/M phase (Figure S2A), increased resistance to erastin or RSL3-induced ferroptosis in ECM-detached cells was still observed despite the pretreatment of cells with palbociclib (a CDK4/6 inhibitor) (Figures S2B–S2D). Moreover, palbociclib treatment is not sufficient to confer resistance to erastin or RSL3-mediated ferroptosis in ECM-attached cells. Taken together, these data indicate that decreased cell proliferation does not account for the increased resistance to ferroptosis in ECM-detached cells.

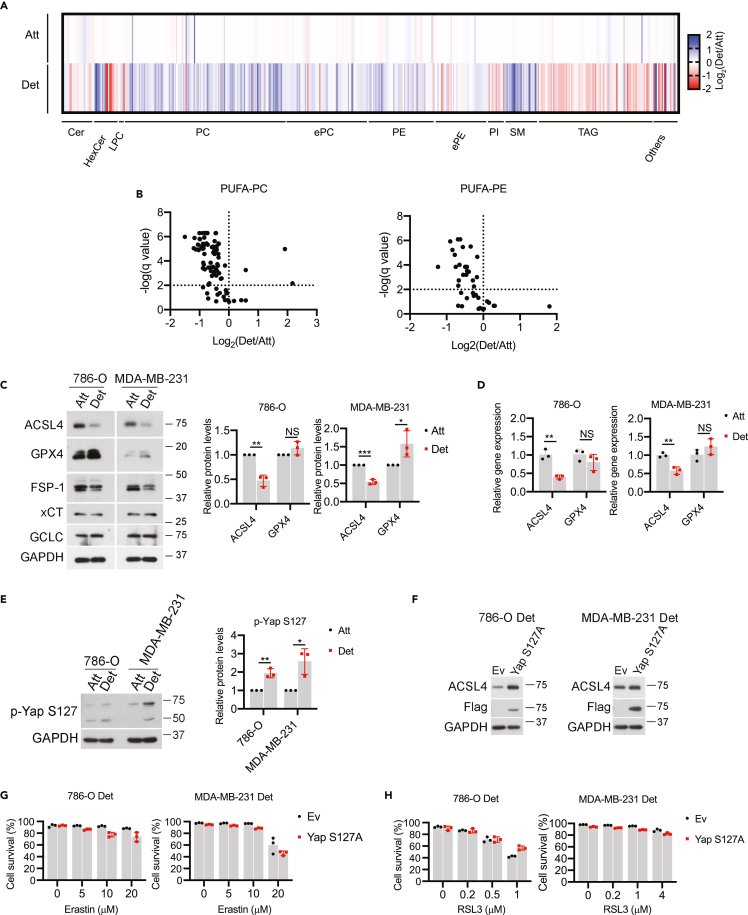

Previous studies in cancer cells suggest that growth in ECM-detached conditions (including as circulating tumor cells) can result in cell-cell clusters that promote cell survival and ultimately, tumor progression and metastasis.45,46,47,48,49 Similarly, the formation of cell-cell clusters has also been linked to ferroptosis resistance because of the inhibition of Yap-mediated expression of ACSL4,29 a protein that stimulates ferroptosis by promoting the incorporation of oxidizable polyunsaturated fatty acid phospholipids (PUFA-PLs) into membranes.28 Given these findings, we sought to assess whether aggregation-induced changes in lipid composition were underlying the resistance of ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis. We first conducted mass spectrometry-based lipidomics analysis and observed alterations in a number of distinct lipid species as a consequence of growth in ECM detachment (Figure 2A). More specifically, growth in ECM-detached conditions resulted in a significant loss of PUFA-containing phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) (Figure 2B). In addition, levels of ACSL4 protein (Figure 2C) and transcript (Figure 2D) were substantially reduced in ECM-detached conditions. Notably, we did not observe large changes in the abundance of other ferroptosis regulators (GPX4, FSP-1, xCT, GCLC) that were likely to account for the resistance of ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis induction (Figure 2C). In sum, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that diminished abundance of ACSL4-mediated PUFAs may contribute to ferroptosis resistance during ECM detachment.

Figure 2.

Loss of Yap-regulated ACSL4 does not account for ferroptosis resistance in ECM-detached cells

(A) Heatmap of the relative lipid abundance between attached and detached 786-O cells after 24-h detachment. Abbreviations: Cer, ceramide; HexCer: hexosylceramide; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; PC, phosphadylcholine; TAG, triacylglycerol; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; ePE, (vinyl ether-linked) PE-plasmalogen; PI, phosphatidylinositol; SM, sphingomyelin. Blue: down-regulated relative to the attached cells, red: upregulated relative to the attached cells.

(B) Volcano plot for poly-unsaturated fatty acid linked phosphatidylcholine (PUFA-PC) or phosphatidylethanolamine (PUFA-PE).

(C) Western blot detection of protein levels in cells after 24-h detachment. Data from three independent experiments were quantified on the right.

(D) Gene expression by quantitative real-time PCR.

(E) Western blot detection of p-Yap S127 after 24-h detachment. Data from three independent experiments were quantified on the right.

(F) Western blot to verify Yap S127A overexpression and rescue of ACSL4 expression under ECM detachment.

(G and H) Cell survival in empty vector (Ev) or Yap S127A expressing cells treated with increasing doses of erastin (G) or RSL3 for 24 h (H).∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; NS, not significant; two-tailed Student’s t test. Data are mean ± SD. Graphs represent data collected from a minimum of three biological replicates and all western blotting experiments were independently repeated a minimum of three times with similar results.

As mentioned above, loss of ACSL4 has been previously linked to the diminished Yap activity as a consequence of cell-cell contacts. Indeed, consistent with previous findings,29 phosphorylation of Yap at serine 127 (which prevents Yap activation by blocking its translocation to the nucleus) was elevated when cells are grown in ECM detachment (Figure 2E). Yap activity can be enhanced through the generation of the S127A mutation which prevents phosphorylation and thus enhances nuclear retention.29 Indeed, expression of the Yap S127A mutant in ECM-detached cells results in elevated levels of ACSL4 (Figure 2F). Despite the restoration of ACSL4 levels in ECM-detached cells, cells expressing Yap S127A remain similarly resistant to ferroptosis induction by erastin (Figure 2G) or RSL3 (Figure 2H). To complement these studies, we also disrupted cell-cell contacts directly using EDTA (Figure S2E) or methylcellulose (MC) (Figure S2F) and assessed the sensitivity to ferroptosis induction. While we did observe marginal changes in erastin or RSL3-mediated cell survival as a consequence of EDTA or MC treatment (Figures S2E and S2F), the levels of lipid ROS remained low during ECM detachment (Figures S2G and S2H). Taken together these results suggest that alterations in the cell contact-Yap-ACSL4 axis do not underlie the sensitivity of ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis induction.

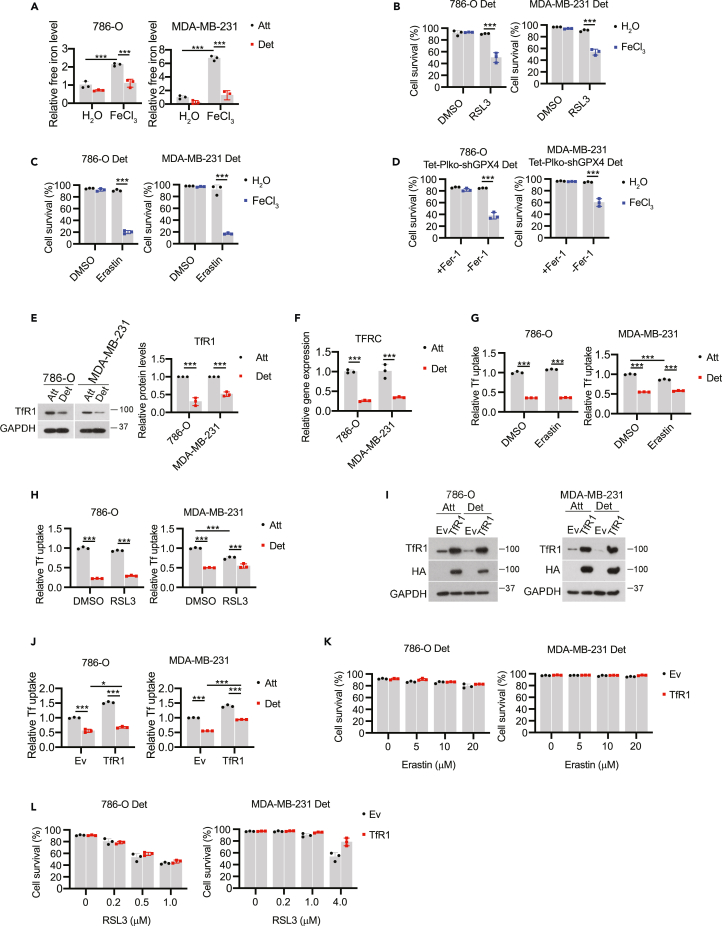

ECM detachment causes alterations in iron uptake

Given that the ECM detachment-mediated changes in ACSL4 do not confer ferroptosis resistance and that we did not detect changes in the abundance of other proteins known to be involved in the detoxification of lipid ROS (Figure 2C), we next investigated whether ECM detachment resulted in modifications in iron metabolism. Of interest, the levels of free (redox-active) iron were diminished during ECM detachment when cells were grown in either normal or iron overload (FeCl3 addition) conditions (Figure 3A). Similarly, free iron levels were markedly reduced when ECM-detached cells were treated with erastin (Figure S3A) or RSL3 (Figure S3B). Thus, we hypothesized that the lower levels of free iron in ECM-detached cells may contribute to the observed ferroptosis resistance. Indeed, supplementation with excess iron (FeCl3 addition) was sufficient to sensitize ECM-detached cells to death caused by RSL3 (Figure 3B), erastin (Figure 3C), or cystine starvation (Figure S3C). Analogous results were obtained using a genetic method of ferroptosis induction as shRNA targeting GPX4 can cause cell death in ECM-detached cells when iron supplementation was provided (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Iron uptake is reduced in ECM-detached cells

(A–D) Free iron level detection in cells treated with either H2O or FeCl3 (100 μM) for 24 h. (B-D) Cell survival in detached cells treated with erastin (B), RSL3 (C) or Fer-1 withdrawal (D) together with either H2O or FeCl3 (100 μM) for 24 h.

(E and F) TfR1 protein (E) and mRNA (F) expression in cells detached for 24 h.

(G and H) Transferrin uptake assay in 786-O and MDA-MB-231 cells treated with erastin (5 μM, 12 h) (G) or RSL3 (0.2 μM, 3 h) (H).

(I) Western blot detection of TfR1 in TfR1-overexpressing cells.

(J) Transferrin uptake assay in Ev or TfR1 overexpressed cells.

(K and L) Cell survival in detached cells treated with increasing doses of erastin (K) or RSL3 (L) for 24 h∗∗∗p < 0.001, two-tailed Student’s t test in E and F. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test in A, B, C, D, G, H, and J. Data are mean ± SD. Graphs represent data collected from a minimum of three biological replicates and all western blotting experiments were independently repeated a minimum of three times with similar results.

We next sought to determine why ECM-detached cells have lower levels of free-iron than their ECM-attached counterparts. As such, we reasoned that alterations in iron uptake may account for the observed differences. Indeed, we discovered that ECM detachment resulted in lower levels of transferrin receptor 1 protein (TfR1, which internalizes transferrin-bound iron through clathrin-mediated endocytosis50) as measured by western blot (Figure 3E) or qRT-PCR (Figure 3F). We also found that transferrin uptake was reduced in ECM-detached conditions in the presence and absence of erastin (Figure 3G) or RSL3 (Figure 3H). These data suggest that deficiencies in transferrin-mediated iron uptake could contribute to the resistance of ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis induction. To test this possibility, we engineered 786-O or MDA-MB-231 cells to express high levels of HA-tagged TfR1 and measured the sensitivity of these cells to ferroptosis induction during ECM detachment. Despite robust elevation of TfR1 in our cell lines (Figure 3I) and a concurrent increase in transferrin uptake (Figure 3J), we did not observe appreciable differences in erastin (Figure 3K) or RSL3 (Figure 3L)-mediated death in cells overexpressing TfR1. These results suggest that rescuing TfR1 levels is not sufficient to sensitize ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis-inducing agents.

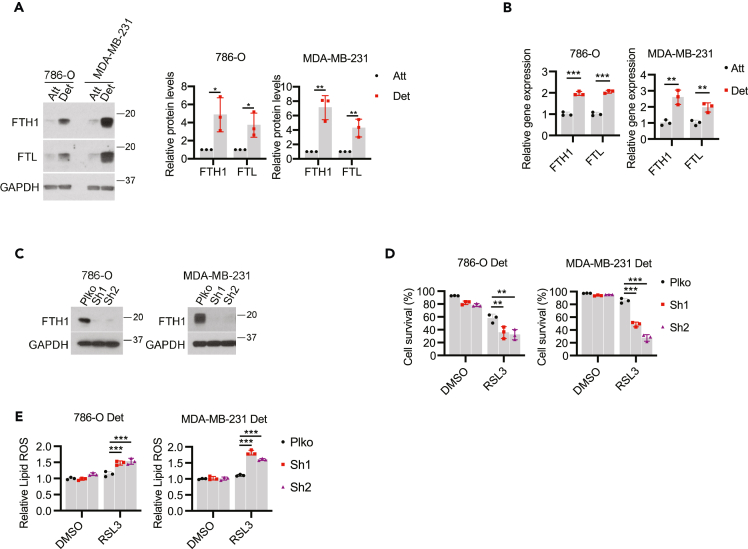

Alterations in FTH1 contribute to ferroptosis resistance during ECM detachment

Given that rescue of TfR1 levels is not sufficient to sensitize ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis induction, we sought to investigate whether changes in iron storage were altered as a consequence of growth in ECM detachment. Most cells will store excess iron in ferritin, a protein made up of ferritin heavy chain (FTH1) and ferritin light chain (FTL) subunits.51 Indeed, the levels of both FTH1 and FTL protein (Figure 4A) and transcript (Figure 4B) were increased on growth in ECM detachment. To assess the contribution of elevated FTH1 levels to ferroptosis resistance during ECM detachment, we engineered 786-O and MDA-MB-231 cells to be deficient in FTH1 (Figure 4C). In both cell lines, shRNA targeting FTH1 was sufficient to sensitize ECM-detached cells to RSL3-mediated cell death (Figure 4D). Similarly, shRNA targeting FTH1 sensitized ECM-detached cells to erastin (Figure S4A) and cystine starvation (Figure S4B) mediated cell death. Furthermore, the shRNA-mediated FTH1 deficiency caused a significant elevation in the levels of lipid ROS in ECM-detached cells exposed to RSL3 (Figure 4E), erastin (Figure S4C), or cystine starvation (Figure S4D). Taken together, these findings suggest that elimination of ECM detachment-mediated upregulation in FTH1 can sensitize ECM-detached cells to death by ferroptosis.

Figure 4.

FTH1 contributes to ferroptosis resistance in ECM-detached cells

(A) Western blot detection of FTH1 and FTL protein expressions in cells detached for 24 h. Quantification of protein levels was shown.

(B) qRT-PCR detection of FTH1 and FTL gene expressions in cells detached for 24 h.

(C) Western blot detection of FTH1 in cells stably expressing empty vector control (Plko) or FTH1 shRNAs.

(D) Cell survival of detached cells treated by RSL3 (0.2 μM for 786-O, 1 μM for MDA-MB-231) for 24 h.

(E) Lipid ROS of detached cells treated by RSL3 (0.2 μM for 786-O, 1 μM for MDA-MB-231) for 3 h∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, two-tailed Student’s t test in A and B. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test in D and E. Data are mean ± SD. Graphs represent data collected from a minimum of three biological replicates and all western blotting experiments were independently repeated a minimum of three times with similar results.

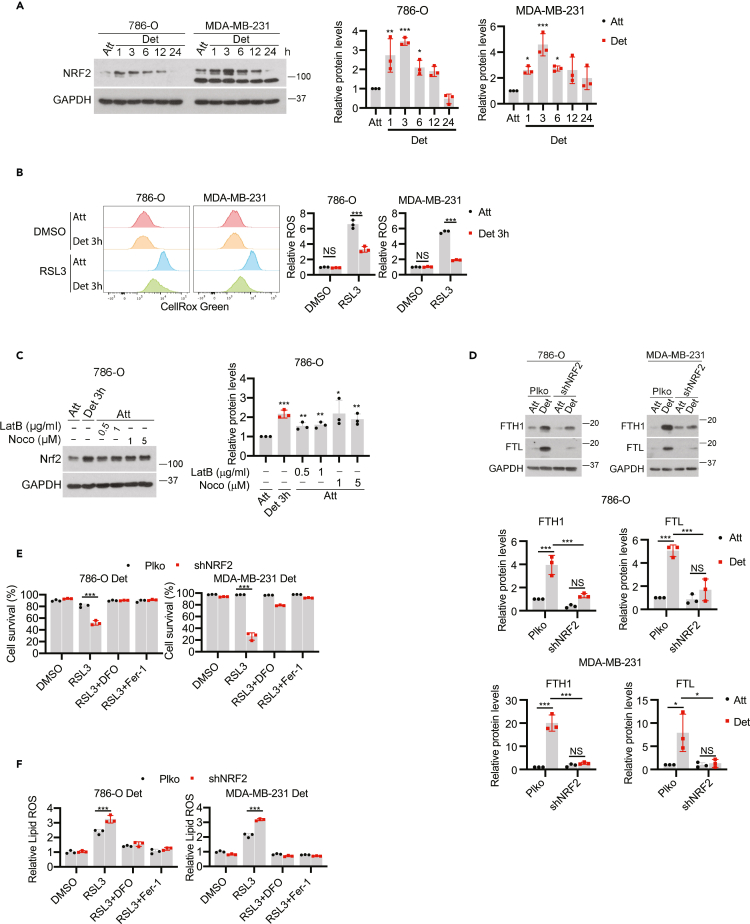

Nrf2 controls FTH1 expression and determines ferroptosis resistance in ECM-detached cells

We next endeavored to identify the upstream regulators of FTH1 during ECM detachment. Both FTH1 and FTL are known targets of the NRF2 transcription factor,52,53 which is typically activated to neutralize excess oxidative stress.54,55 Given that ECM-detached cells are often exposed to elevated oxidative stress,4,9,56 we investigated the levels of NRF2 when cells are grown in ECM-detached conditions. Indeed, we observed a rapid, robust elevation in NRF2 levels in 786-O or MDA-MB-231 cells when grown in ECM detachment (Figure 5A). Of interest, the rapid increase in NRF2 protein during ECM detachment precedes the elevation in ROS levels caused by ECM detachment, which was not evident after 3 h of growth in ECM-detached conditions (Figure 5B). NRF2 levels can also be induced by cytoskeletal changes that impact Keap1,57 a negative regulator of NRF2. Indeed, disruption of actin filaments with latrunculin B (LatB) or interference of microtubules with nocodazole (Noco) in ECM-attached cells leads to elevated NRF2 expression (Figure 5C). Given that changes in the cytoskeleton during ECM detachment have been previously reported,58 this mechanism may underlie the rapid induction of NRF2 during ECM detachment.

Figure 5.

Nrf2-FTH1 signaling determines ferroptosis resistance in ECM-detached cells

(A) Western blot detection of NRF2 expression in cells detached for different time points. Quantification from three independent experiments was shown on the right.

(B) ROS detection by CellRox Green staining in attached and detached cells treated with DMSO or RSL3 (0.2 μM) for 3h.

(C) Western blot detection of NRF2 in 786-O cells treated with latrunculin B or nocodazole for 3 h. Quantification from three independent experiments was shown on the right.

(D) Western blot detection of FTH1 and FTL protein expressions in 786-O and MDA-MB-231 cells expressing empty control (Plko) or NRF2 shRNA (shNRF2). Protein quantification was shown.

(E) Cell survival of detached cells treated with RSL3 (0.2 μM for 786-O, 1 μM for MDA-MB-231) for 24 h.

(F) Lipid ROS detection in detached cells treated with RSL3 (0.2 μM for 786-O, 1 μM for MDA-MB-231) for 3 h. For ferroptosis inhibition, 100 μM DFO or 2.5 μM Fer-1 was used. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test in A and C. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, NS, not significant, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test in B, D, E and F. Data are mean ± SD. Graphs represent data collected from a minimum of three biological replicates and all western blotting experiments were independently repeated a minimum of three times with similar results.

We next generated cells that were deficient in NRF2 (Figure S5A) and found a substantial reduction in the abundance of both FTH1 and FTL protein (Figure 5D) and mRNA (Figure S5B) as a consequence of NRF2 shRNA. Moreover, when we assessed the sensitivity of NRF2-deficient cells to ferroptosis induction, we found that shRNA targeting NRF2 was sufficient to sensitize ECM-detached cells to RSL3 (Figure 5E), erastin (Figure S5C), or cystine starvation (Figure S5D)-mediated cell death. Notably, cell death in each of these cases was blocked by treatment with DFO or Fer-1. Furthermore, NRF2-deficiency promoted lipid ROS accumulation in ECM-detached cells treated with RSL3 (Figure 5F), erastin (Figure S5E), or cystine starvation (Figure S5F) which could also be blocked by either DFO or Fer-1. As such, these data suggest that antagonizing NRF2-mediated changes in FTH1 can sensitize ECM-detached cells to death by ferroptosis.

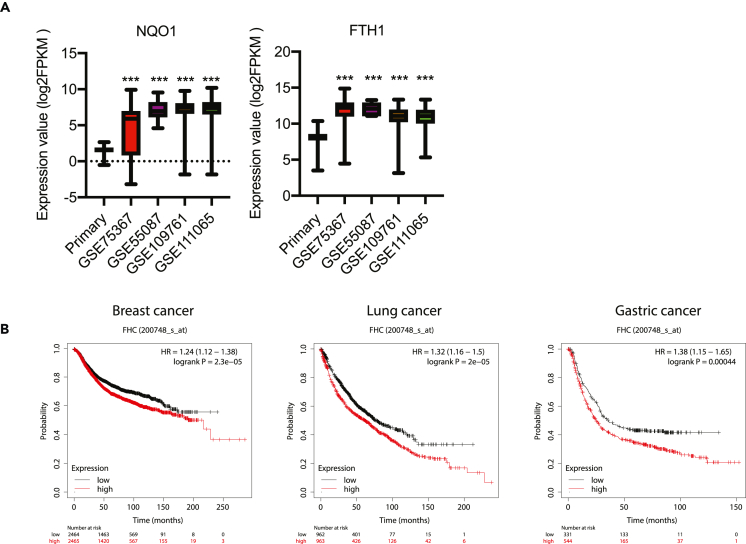

FTH1 expression is increased in CTCs and correlates with poor clinical outcome

One scenario in which cancer cells would be exposed to ECM detachment is in the bloodstream during metastatic dissemination. As such, we would expect the insensitivity of ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis to be important in circulating tumor cells (CTCs). Indeed, there is already evidence that ferroptosis resistance is important for the survival of CTCs. For example, CTCs from melanoma patients are protected from ferroptosis in the lymph and exhibit alterations in lipogenesis and iron homeostasis pathways.59,60 As such, we reasoned that Nrf2-FTH1 signaling is turned on in CTCs in a fashion that protects these cells from ferroptosis induction. To assess this possibility, we analyzed the expression of NQO1 (a canonical Nrf2 target gene) and FTH1 in breast cancer CTCs using the publicly available ctcRbase tool.61 Compared with primary breast tumors, CTCs did display higher expression of both NQO1 and FTH1 (Figure 6A). Relatedly, high expression of FTH1 correlates with poor clinical outcomes in patients with breast, lung, or gastric cancers (Figure 6B). Altogether, these data suggest that the activation of Nrf2-FTH1 signaling in CTCs may increase the resistance of CTCs to ferroptosis and promote tumor metastasis.

Figure 6.

FTH1 expression is increased in CTCs and correlates with poor prognosis

(A) NQO1 and FTH1 gene expressions in primary breast cancer and CTCs. Selective gene expressions were analyzed using ctcRbase by comparing TCGA primary breast cancer (n = 1097) with GSE75367 (n = 61), GSE55087 (n = 6), GSE109761 (n = 59) and GSE111065 (n = 70).

(B) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of cancer patients. Relapse-free survival for breast cancer patients and overall survival for lung and gastric cancer patients were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier Plotter.∗∗∗p < 0.001, two-tailed Student’s t test in A compared with primary tumor. Data are mean ± SD.

Discussion

Our studies reveal that growth in ECM detachment can substantially alter the sensitivity of cells to ferroptosis induction. ECM-detached cells are starkly resistant to ferroptosis triggered by distinct pharmacological stimuli (e.g. erastin, RSL3) and genetic changes (e.g., shRNA of GPX4). Although ECM detachment does promote enhanced cell-cell contacts, diminished Yap-mediated expression of ACSL4, and reduced levels of PUFAs; these changes do not underlie the resistance of ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis induction. Instead, we found that ECM detachment can cause profound changes in iron metabolism and demonstrated that the addition of excess, redox-active iron is sufficient to confer sensitivity to ferroptosis induction during ECM detachment. We revealed that ECM-detached cells have both significant downregulation of TfR1-mediated iron uptake and upregulation of ferritin-related iron storage. Relatedly, we found that shRNA-mediated reduction of FTH1 was sufficient to sensitize ECM-detached cells to ferroptosis induction.

Our data suggest that as a consequence of ECM detachment, cells undergo profound changes in iron metabolism that bestow significant resistance to ferroptosis induction. Notably, these changes in iron metabolism mirror other, previously defined changes in both glucose and glutamine metabolism and suggest that there are perhaps additional nutrients whose metabolism is altered during ECM detachment.4,5 Furthermore, our data provide important nuance to understanding ferroptosis regulation. Previous studies have reported evidence that ECM detachment can function as a trigger for the activation of ferroptosis because of deficient α6β4-mediated signal transduction.62 Thus, ECM detachment could function to initiate ferroptosis in some cell types but ultimately those cells that survive acquire profound resistance to ferroptosis induction by other stimuli. In addition, the process of adaptation undertaken by cells that survive ECM detachment may create de novo mechanisms of resistance or vulnerability.

Lastly, our data raise important questions about the capacity to utilize ferroptosis activation as a strategy against invasive or metastatic cancers. As discussed previously, there is broad interest in devising novel compounds that may target cancer cells for ferroptotic death.25,36,37,38,39,40,41,42 However, our data raise the distinct possibility that such approaches may need to account for the fact that ECM-detached cells, as a consequence of reprogramming of iron metabolism, may be resistant to efforts to cause ferroptosis. As such, therapeutic strategies that rely on ferroptosis induction may be hindered by the difficulty in killing ECM-detached cells. On the other hand, the reprogramming of iron metabolism during ECM detachment may be a vulnerability that could be targeted to specifically eliminate cells on loss of ECM-attachment. Future studies aimed at sensitizing cancer cells in ECM-detached conditions (e.g., as circulating tumor cells) to ferroptosis may involve simultaneous treatment with ferroptosis activating compounds and agents that cause elevation in redox-active iron.

Limitations of the study

Our findings in Figure 6 suggest that elevated FTH1 levels in CTCs and poor outcomes in patients with high FTH1 correlate with enhanced resistance to ferroptosis during ECM-detached conditions. However, this association does not prove that FTH1-mediated ferroptosis resistance during ECM detachment is a cause of CTC survival or enhanced metastasis. Additional investigation that moves beyond our study will be important in assessing the pathophysiological relevance of alterations in iron metabolism and ferroptosis sensitivity during ECM detachment. Furthermore, our data reveal that changes in the proliferative capacity of ECM-detached cells do not account for ferroptosis resistance during ECM detachment (see Figures S2A-S2D). However, the induction of cell-cycle arrest via palbociclib treatment does partially desensitize ECM-attached cells to erastin (but not RSL3); a finding that is consistent with previously published links between cell cycle regulators and ferroptosis sensitivity.40 As such, additional studies that investigate the interplay between proliferative changes, iron metabolism, and ferroptosis sensitivity will help provide additional context to the molecular mechanisms that promote ferroptosis resistance during ECM detachment.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| GPX4 | Abcam | Cat#ab41787, RRID:AB_941790 |

| GCLC | Abcam | Cat#ab190685, RRID:AB_2889925 |

| NRF2 | Abcam | Cat#ab62352, RRID:AB_944418 |

| ACSL4 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat#sc-271800, RRID:AB_10715092 |

| GAPDH | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#5174, RRID:AB_10622025 |

| FTH1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#3998, RRID:AB_1903974 |

| FTL | Proteintech | Cat#10727-1-AP, RRID:AB_2278673 |

| xCT | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#12691, RRID:AB_2687474 |

| p-Yap S127 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#13008, RRID:AB_2650553 |

| TfR1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#13113, RRID:AB_2715594 |

| FLAG Tag | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2368, RRID:AB_2217020 |

| FSP1 | Proteintech | Cat#20886-1-AP, RRID:AB_2878756 |

| HA | Biolegend | Cat#901501, RRID:AB_2565006 |

| Anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#7076, RRID:AB_330924 |

| Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#7074, RRID:AB_2099233 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Erastin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#329600 |

| RSL3 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# SML2234 |

| Ferrostatin-1 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#SML0583 |

| Deferoxamine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#D9533 |

| Nocodazole | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#M1404 |

| Latrunculin B | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#428020 |

| Poly-HEMA | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#P3932 |

| Methylcellulose | Fisher Scientific | Cat#80080 |

| C11-Bodipy 581/591 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#D3861 |

| CellRox Green | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#C10444 |

| Calcein-AM | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#C3099 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated human transferrin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#T13342 |

| Prodidium iodide | Sigma | Cat#P4170 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| 786-O | ATCC | Cat#CRL-1932 |

| RCC10 | Celeste Simon lab | N/A |

| MDA-MB-231 | ATCC | Cat#HTB-26 |

| SUM159 | BioIVT | Cat#HUMANSUM-0003006 |

| HeLa | ATCC | Cat#CCL-2 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primer for human GPX4 Forward: 5′-GGAGCCAGGGAGTAACGAAG-3′ |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer for human GPX4 Reverse: 5′-CACTTGATGGCATTTCCCAGG-3′ |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer for human FTL Forward: 5′-CAGCCTGGTCAATTTGTACCT-3′ |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer for human FTL Reverse: 5′-GCCAATTCGCGGAAGAAGTG-3′ |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer for human FTH1 Forward: 5′-CCAGAACTACCACCAGGACTC-3′ |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer for human FTH1 Reverse: 5′-GAAGATTCGGCCACCTCGTT-3′ |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer for human TFRC Forward: 5′-GGCTACTTGGGCTATTGTAAAGG-3′ |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer for human TFRC Reverse: 5′-CAGTTTCTCCGACAACTTTCTCT-3′ |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer for human ACSL4 Forward: 5′-ACTGGCCGACCTAAGGGAG-3′ |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer for human ACSL4 Reverse: 5′-GCCAAAGGCAAGTAGCCAATA-3′ |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer for human 18S Forward: 5′-GGCGCCCCCTCGATGCTCTTAG-3′ |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer for human 18S Reverse: 5′-GCTCGGGCCTGCTTTGAACACTCT-3′ |

This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pQCXIH-Flag-YAP-S127A | Addgene | Cat#33092 |

| pcDNA3.2/DEST/hTfR-HA | Addgene | Cat#69610 |

| pBabe-puro-TfR1-HA | This paper | N/A |

| Tet-Plko-Puro | Addgene | Cat#21915 |

| Tet-Plko-Puro-shGPX4 | This paper | N/A |

| shFTH1-1 | Sigma-Aldrich | Clone: TRCN0000029432 |

| shFTH1-2 | Sigma-Aldrich | Clone: TRCN0000029433 |

| shNRF2 | Sigma-Aldrich | Clone: TRCN0000273494 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| ImageJ, version 1.52a for Mac | National Institutes of Health | https://ImageJ.nih.gov/ij/index.html |

| Prism, version 8.0.0 for Mac | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Flowjo, version 10.8.1 for windows | BD Biosciences | https://www.flowjo.com |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Zachary T. Schafer (zschafe1@nd.edu).

Materials availability

Plasmids and/or cell lines generated in this study are available upon reasonable request. Please contact the lead contact.

Experimental model and subject details

Cell lines

MDA-MB-231, 786-O and HeLa cells were from ATCC. SUM159 cell line was from BioIVT. RCC10 cell line was kindly provided by Dr. Celeste Simon (University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine). SUM159 cell line was maintained in Ham’s F12 (Gibco). All other cell lines were maintained in DMEM (Gibco). Culture medium was supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Mycoplasma testing was routinely performed using mycoplasma PCR detection kit (LiliF, 102407-870) in all cell lines.

Reagents

Erastin (329600), RSL3 (SML2234), Ferrostatin-1 (SML0583), Deferoxamine (DFO; D9533), Nocodazole (M1404), and Latrunculin B (428020) were from Sigma. Methylcellulose (80080) was from Fisher Scientific.

Plasmids and retrovirus packaging

pQCXIH-Flag-YAP-S127A was from Addgene (#33092). pBabe-puro-TfR1-HA plasmid was generated by amplifying TfR1-HA from pcDNA3.2/DEST/hTfR-HA (Addgene, #69610) and inserting into pBabe-puro vector. For retrovirus packaging, 1.5 μg empty vector (EV) or plasmids carrying overexpressed genes were transfected to HEK293T cells together with 1.5 μg pCLAmpho. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Virus supernatant was collected 48 h after transfection and passed through 0.45 μm filter (EMD Millipore). Target cells were infected with virus supernatant in the presence of 10 μg/mL polybrene. Stable cell lines were selected using 750 μg/mL hygromycin (Sigma) for pQCXIH or 2 μg/mL puromycin (Invitrogen) for pBabe-puro.

Lentivirus mediated shRNA

For inducible GPX4 knockdown, shRNA sequence targeting human GPX4 (5′-GTGGATGAAGATCCAACCCAA-3′, TRCN0000046251) was cloned to Tet-Plko-puro according to the manual. Tet-pLKO-puro was a gift from Dmitri Wiederschain (Addgene, #21915). MISSION shRNA constructs for human FTH1 (NM_002032; clone nos TRCN0000029432, TRCN0000029433), human NRF2 (NM_006164; clone no TRCN0000273494), in the puromycin-resistant pLKO vectors were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

For packaging of lentivirus, HEK293T cells were transfected with 2 μg target DNA along with the packaging vectors psPAX2 (2.5 μg) and pCMV-VSV-G (0.5 g) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Virus supernatant was collected 48 h after transfection and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter (EMD Millipore). Cells were infected with virus supernatant in the presence of 10 μg/mL polybrene. Stable populations of cells were selected using 2 μg/mL puromycin (Invitrogen).

Method details

Western blot

After treatment, both attached and detached cells are washed once with 2 mL PBS. ECM-attached and detached cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with 1 μg/mL aprotinin, 5 μg/mL leupeptin, 20 μg/mL phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and HALT phosphatase inhibitor mixture (Thermo Scientific). For attached cells, cells are lysed directly on 6-well plate. For detached cells, cells are resuspended in RIPA buffer. Cell lysates are sonicated with 1-s pulse on and 1-s pulse off for 8 s using Branson sonifier at 10% amplitude. After sonication, cell lysates were cleared by centrifuging at 13,000 rpm for 15 min. Supernatants were quantified by BCA assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Waltham, MA, USA) and normalized to same protein concentrations. 4X Lamelli sample buffer was added and heated at 95°C for 10 min. After SDS-PAGE, transfer and blocking, membranes were probed with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) linked secondary antibody incubation followed by chemiluminescent detection using SignalFire ECL Reagent (CST; 6883) was used to detect the blots. The following antibodies were used for western blotting: GPX4 (Abcam; ab41787; 1:2000), GCLC (Abcam; ab190685; 1:5000), NRF2 (Abcam; ab62352; 1:1000), ACSL4 (Santa Cruz biotechnology; sc-271800; 1:1000), GAPDH (CST; 5174S; 1:5000), FTH1 (CST; 3998S; 1:1000), FTL (Proteintech; 10727-1-AP; 1:1000), FSP1 (Proteintech; 20886-1-AP; 1:1000), xCT (CST; 12691), p-Yap S127 (CST; 13008T; 1:1000), HA-Tag (Biolegend; 901501; 1:2000), FLAG Tag (CST; 2368S; 1:1000), TfR1 (CST; 13113S; 1:1000).

Poly-HEMA coating

Poly-HEMA (Sigma; P3932) stock solution was made by dissolving 6 g Poly-HEMA in 1 L 95% ethanol (stir overnight at room temperature). For 6 well plates, add 1 mL poly-HEMA stock solution to each well, for 12 well plates add 0.5 mL poly-HEMA stock solution to each well. Keep plates in 37°C incubator for about one week until all liquid evaporates. Store coated plates at room temperature.

PI staining for cell viability

Cells plated on 12 well plates (8×104 cells per well) under attached or detached (Poly-HEMA) conditions were treated with different compounds for the indicated time. At the end of treatment, for attached cells, to include any floating dead cells, culture medium was collected. Cells were then washed with 300 μL PBS and PBS was combined together with culture medium. Cells were trypsinized and trypsin neutralized with the collected culture medium. For detached cells, cells were spun down and washed with 300 μL PBS. After trypsinization, trypsin was neutralized with complete medium. Both trypsinized attached and detached cells were spun down and resuspended in 180 μL PBS containing 2 μg/mL prodidium iodide (PI) (Sigma; P4170) and detected by flow cytometry (BD fortessa X-20). Single cells were gated and cell survival was measured by analyzing PI-negative and FSC-A high cells.

PI staining for cell cycle

Cells were trypsinized and fixed in pre-chilled 70% ethanol for 30 min or kept at −20°C overnight. Cells were spun down, resuspended in 300 μL staining solution (25 μg/mL PI, 100 μg/mL Rnase A in PBS), and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Single cells were analyzed by flow cytometry and cell cycle distribution was analyzed using Flowjo.

C11-bodipy 581/591 staining

After treatment, both attached and detached cells were trypsinized to single cells as described in PI staining. Cells were then stained in 300 μL 1 μM C11-Bodipy 581/591 (Invitrogen; D3861) dissolved in PBS at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were spun down, resuspended in 180 μL PBS and detected by flow cytometry. Live single cells were gated and the geometry mean of FITC intensity was quantified. Relative lipid ROS was then calculated.

CellRox green staining for ROS detection

Cells were trypsinized to single cells and stained with 5 μM CellRox Green (Invitrogen; C10444) at 37°C in PBS for 30 min. Cells were analyzed with flow cytometry and the geometry mean intensity FITC channel was quantified.

Calcein staining for labile iron

After treatment, both attached and detached cells were trypsinized to single cells. Cells were resuspended in 500 μL PBS containing 100 nM Calcein-AM (Thermo Fisher; C3099) and kept at 37°C for 15 min. Cells were then washed once with PBS and separated into two tubes. Tube 1 was resuspended in 200 μL PBS and tube 2 was resuspended in 200 μL PBS with 100 μM deferiprone (Sigma; 379409). Both tubes were kept at 37°C for 30 min. Calcein fluorescence was detected by flow cytometry and the difference in fluorescent intensity between tube 2 and tube 1 was used to indicate the labile iron pool.

Transferrin uptake assay

After treatment, both attached and detached cells were balanced for 1 h in 500 μL serum-free DMEM containing 25 mM HEPES, pH7.4 with 1% BSA. Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated human transferrin (Invitrogen; T13342) (5 mg/mL stock solution in PBS) was added at 20 μg/mL, and kept at 37 for 30 min. Cells were washed with PBS and trypsinized into single cells. To remove surface-bound transferrin, cells were washed twice with pre-chilled PBS (pH 5.0). Transferrin uptake was determined by flow cytometry.

Real-time PCR

Cells were plated on attached or detached conditions for 24 h. For mRNA extraction, RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen; 74104) was used. For attached cells, cells were lysed directly on plates. For detached cells, cells were spun down and lysed. Total mRNA was extracted according to manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using reverse transcription supermix (Bio-rad; 1708840) and resulted cDNAs were further utilized for RT-PCR using SYBR green supermix (Bio-rad; 1725271). The following primers were used:

Human GPX4, Forward: 5′-GGAGCCAGGGAGTAACGAAG-3′; Reverse: 5′-CACTTGATGGCATTTCCCAGG-3′

Human FTL, Forward: 5′-CAGCCTGGTCAATTTGTACCT-3′; Reverse: 5′-GCCAATTCGCGGAAGAAGTG-3′

Human FTH1, Forward: 5′-CCAGAACTACCACCAGGACTC-3′; Reverse: 5′-GAAGATTCGGCCACCTCGTT-3′

Human TFRC, Forward: 5′-GGCTACTTGGGCTATTGTAAAGG-3′; Reverse: 5′-CAGTTTCTCCGACAACTTTCTCT-3′

Human ACSL4, Forward: 5′-ACTGGCCGACCTAAGGGAG-3′; Reverse: 5′-GCCAAAGGCAAGTAGCCAATA-3′

Human 18S, Forward: 5′-GGCGCCCCCTCGATGCTCTTAG-3′; Reverse: 5′-GCTCGGGCCTGCTTTGAACACTCT-3′

Lipidomics and mass spectrometry

Lipids were extracted from cells by Bligh Dyer extraction. For adherent cells, plates were first scraped into ice-cold methanol, then transferred to a tube containing chloroform. Suspension cells were lysed directed in chloroform:methanol (1:1, v/v). To induce phase separation, water was added to achieve a final chloroform:methanol:water ratio of 2:2:1.8 (v/v). The lipid containing organic layer was collected, dried in a speedvac, and resuspended in 1:1 (v/v) isopropanol:acetonitrile. 100uL of each sample was used to make a pooled sample for lipid identification. Lipidomics analysis was collected by LC/MS using an ID-X Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific)> 2uL of reconstituted extract was injected for liquid chromatography separation using a C30 column (27826–152130, Thermo) maintained at 50°C. Lipids were eluted with a gradient (A: 60% acetonitrile, B: 90% isopropanol, 8% acetonitrile, both with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid) of 0-30min starting at 75%A, 1-3min ramp from 75%A to 60%A, 3-19min from 60%A to 25%A, 19-20.5min from 25%A to 10%A, 20.5–28min from 10%A to 5%A, 28-28.1min from 5%A to 0%A, and ending with an isocratic hold at 0%A from 28.1–30minat 400uL/min. Lipids were detected in ESI+ positive mode (spray voltage of 3250 V, sheath gas: 40 a.u., aux gas: 10 a.u., sweep gas: 1 a.u., ion transfer tube: 300°C, vaporizer: 275°C). Experimental replicates were analyzed in MS1 only at a resolution of 240,000 FWHM. Pooled samples were used for lipid ID via data dependent MS3 method that triggers all ions reaching an intensity threshold 10x above a blank for HCD fragmentation. An HCD MS2 fragment of 184, a diagnostic ion for phosphatidyl choline, triggered an additional MS2 fragmentation scan using CID to gain information on acyl chain composition. A neutral loss of acyl chains triggered MS3 scan in HCD to gain further structural information. ddMS3 samples. ddMS3 data from pooled samples was used for lipid annotation in LipidSearch (Thermo, v5.0). Annotated lipids were then used to generate a mass list (accurate mass at retention time) for Compound Discoverer (Thermo, v3.3), which was used for peak picking and integration of experimental replicates. Differential abundance of lipids was accomplished with Metabolanlyst (v5.0) with an FDR set at 0.05.

Gene expression analysis in ctcRbase and patient survival analysis

The expression of selected genes was analyzed with ctcRbase (http://www.origin-gene.cn/database/ctcRbase/). Relapse-free survival for breast cancer patients and overall survival for lung and gastric cancer were analyzed through the Kaplan-Meier plotter (KM plotter).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± SD. All graphs and statistical analysis were made in Graphpad Prism (8.0.0). Densitometry analysis of western blotdata was completed with ImageJ. Flow cytometry data were analyzed with Flowjo. Student two-tailed unpaired t-test was used for two-group comparison and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey test was used for multi-group comparisons. Details for each figure are included in the Figure Legends.

Acknowledgments

We thank Veronica Schafer and all current/past Schafer lab members for helpful comments and/or valuable discussion. We thank the Flow Cytometry Facility and the Notre Dame Integrated Imaging Facility for experimental assistance. We thank Dr. Celeste Simon (UPenn) for the RCC-10 cell line. ZTS is supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (R01CA262439), the Coleman Foundation, the Boler-Parseghian Center for Rare & Neglected Diseases at Notre Dame, the Malanga Family ExcellenceFund for Cancer Research at Notre Dame, the College of Science at Notre Dame, the Department of Biological Sciences at Notre Dame, and funds from Mr. Nick L. Petroni. RGJ is supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI165722), the Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group Distinguished Investigator Program, and the Van Andel Institute (VAI). We are also grateful for support and inspiration for this work from Mr. Christopher Kiergan and family.

Author contributions

J.H., A.M.A., B.P.M., and R.S.M. conducted experiments, analyzed data, and interpreted results. R.S. and R.G.J. assisted with the lipidomics and LC/MS experiments. J.H. and Z.T.S. wrote the manuscript with feedback from all other authors. J.H. and Z.T.S. were responsible for conception/design of the project and Z.T.S. was responsible for overall study supervision.

Declaration of interests

R.G.J. is a scientific advisor for Agios Pharmaceuticals and Servier Pharmaceuticals and is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Immunomet Therapeutics. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Inclusion and diversity

We support inclusive, diverse, and equitable conduct of research.

Published: May 9, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.106827.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

-

•

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Buchheit C.L., Rayavarapu R.R., Schafer Z.T. The regulation of cancer cell death and metabolism by extracellular matrix attachment. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012;23:402–411. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frisch S.M., Francis H. Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 1994;124:619–626. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mason J.A., Hagel K.R., Hawk M.A., Schafer Z.T. Metabolism during ECM detachment: achilles heel of cancer cells? Trends Cancer. 2017;3:475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schafer Z.T., Grassian A.R., Song L., Jiang Z., Gerhart-Hines Z., Irie H.Y., Gao S., Puigserver P., Brugge J.S. Antioxidant and oncogene rescue of metabolic defects caused by loss of matrix attachment. Nature. 2009;461:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature08268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grassian A.R., Metallo C.M., Coloff J.L., Stephanopoulos G., Brugge J.S. Erk regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase flux through PDK4 modulates cell proliferation. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1716–1733. doi: 10.1101/gad.16771811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason J.A., Cockfield J.A., Pape D.J., Meissner H., Sokolowski M.T., White T.C., Valentín López J.C., Liu J., Liu X., Martínez-Reyes I., et al. SGK1 signaling promotes glucose metabolism and survival in extracellular matrix detached cells. Cell Rep. 2021;34:108821. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mason J.A., Davison-Versagli C.A., Leliaert A.K., Pape D.J., McCallister C., Zuo J., Durbin S.M., Buchheit C.L., Zhang S., Schafer Z.T. Oncogenic Ras differentially regulates metabolism and anoikis in extracellular matrix-detached cells. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:1271–1282. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang L., Shestov A.A., Swain P., Yang C., Parker S.J., Wang Q.A., Terada L.S., Adams N.D., McCabe M.T., Pietrak B., et al. Reductive carboxylation supports redox homeostasis during anchorage-independent growth. Nature. 2016;532:255–258. doi: 10.1038/nature17393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawk M.A., Gorsuch C.L., Fagan P., Lee C., Kim S.E., Hamann J.C., Mason J.A., Weigel K.J., Tsegaye M.A., Shen L., et al. RIPK1-mediated induction of mitophagy compromises the viability of extracellular-matrix-detached cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018;20:272–284. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchheit C.L., Angarola B.L., Steiner A., Weigel K.J., Schafer Z.T. Anoikis evasion in inflammatory breast cancer cells is mediated by Bim-EL sequestration. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:1275–1286. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsegaye M.A., He J., McGeehan K., Murphy I.M., Nemera M., Schafer Z.T. Oncogenic signaling inhibits c-FLIP(L) expression and its non-apoptotic function during ECM-detachment. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:18606. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97715-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weigel K.J., Jakimenko A., Conti B.A., Chapman S.E., Kaliney W.J., Leevy W.M., Champion M.M., Schafer Z.T. CAF-secreted IGFBPs regulate breast cancer cell anoikis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2014;12:855–866. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.Mcr-14-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Debnath J., Mills K.R., Collins N.L., Reginato M.J., Muthuswamy S.K., Brugge J.S. The role of apoptosis in creating and maintaining luminal space within normal and oncogene-expressing mammary acini. Cell. 2002;111:29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reginato M.J., Mills K.R., Paulus J.K., Lynch D.K., Sgroi D.C., Debnath J., Muthuswamy S.K., Brugge J.S. Integrins and EGFR coordinately regulate the pro-apoptotic protein Bim to prevent anoikis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:733–740. doi: 10.1038/ncb1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reginato M.J., Mills K.R., Becker E.B.E., Lynch D.K., Bonni A., Muthuswamy S.K., Brugge J.S. Bim regulation of lumen formation in cultured mammary epithelial acini is targeted by oncogenes. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:4591–4601. doi: 10.1128/mcb.25.11.4591-4601.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Overholtzer M., Mailleux A.A., Mouneimne G., Normand G., Schnitt S.J., King R.W., Cibas E.S., Brugge J.S. A nonapoptotic cell death process, entosis, that occurs by cell-in-cell invasion. Cell. 2007;131:966–979. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchheit C.L., Weigel K.J., Schafer Z.T. Cancer cell survival during detachment from the ECM: multiple barriers to tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2014;14:632–641. doi: 10.1038/nrc3789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dixon S.J., Lemberg K.M., Lamprecht M.R., Skouta R., Zaitsev E.M., Gleason C.E., Patel D.N., Bauer A.J., Cantley A.M., Yang W.S., et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149:1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stockwell B.R. Ferroptosis turns 10: emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic applications. Cell. 2022;185:2401–2421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magtanong L., Mueller G.D., Williams K.J., Billmann M., Chan K., Armenta D.A., Pope L.E., Moffat J., Boone C., Myers C.L., et al. Context-dependent regulation of ferroptosis sensitivity. Cell Chem. Biol. 2022;29:1409–1418.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2022.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang X., Stockwell B.R., Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021;22:266–282. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badgley M.A., Kremer D.M., Maurer H.C., DelGiorno K.E., Lee H.J., Purohit V., Sagalovskiy I.R., Ma A., Kapilian J., Firl C.E.M., et al. Cysteine depletion induces pancreatic tumor ferroptosis in mice. Science. 2020;368:85–89. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw9872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kremer D.M., Nelson B.S., Lin L., Yarosz E.L., Halbrook C.J., Kerk S.A., Sajjakulnukit P., Myers A., Thurston G., Hou S.W., et al. GOT1 inhibition promotes pancreatic cancer cell death by ferroptosis. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4860. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24859-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poursaitidis I., Wang X., Crighton T., Labuschagne C., Mason D., Cramer S.L., Triplett K., Roy R., Pardo O.E., Seckl M.J., et al. Oncogene-selective sensitivity to synchronous cell death following modulation of the amino acid nutrient cystine. Cell Rep. 2017;18:2547–2556. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y., Swanda R.V., Nie L., Liu X., Wang C., Lee H., Lei G., Mao C., Koppula P., Cheng W., et al. mTORC1 couples cyst(e)ine availability with GPX4 protein synthesis and ferroptosis regulation. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1589. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21841-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang W.S., SriRamaratnam R., Welsch M.E., Shimada K., Skouta R., Viswanathan V.S., Cheah J.H., Clemons P.A., Shamji A.F., Clish C.B., et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156:317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang W.S., Stockwell B.R. Synthetic lethal screening identifies compounds activating iron-dependent, nonapoptotic cell death in oncogenic-RAS-harboring cancer cells. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:234–245. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doll S., Proneth B., Tyurina Y.Y., Panzilius E., Kobayashi S., Ingold I., Irmler M., Beckers J., Aichler M., Walch A., et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:91–98. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu J., Minikes A.M., Gao M., Bian H., Li Y., Stockwell B.R., Chen Z.N., Jiang X. Intercellular interaction dictates cancer cell ferroptosis via NF2-YAP signalling. Nature. 2019;572:402–406. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1426-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mishima E., Ito J., Wu Z., Nakamura T., Wahida A., Doll S., Tonnus W., Nepachalovich P., Eggenhofer E., Aldrovandi M., et al. A non-canonical vitamin K cycle is a potent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature. 2022;608:778–783. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05022-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venkatesh D., O'Brien N.A., Zandkarimi F., Tong D.R., Stokes M.E., Dunn D.E., Kengmana E.S., Aron A.T., Klein A.M., Csuka J.M., et al. MDM2 and MDMX promote ferroptosis by PPARα-mediated lipid remodeling. Genes Dev. 2020;34:526–543. doi: 10.1101/gad.334219.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doll S., Freitas F.P., Shah R., Aldrovandi M., da Silva M.C., Ingold I., Goya Grocin A., Xavier da Silva T.N., Panzilius E., Scheel C.H., et al. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature. 2019;575:693–698. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1707-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z., Ferguson L., Deol K.K., Roberts M.A., Magtanong L., Hendricks J.M., Mousa G.A., Kilinc S., Schaefer K., Wells J.A., et al. Ribosome stalling during selenoprotein translation exposes a ferroptosis vulnerability. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022;18:751–761. doi: 10.1038/s41589-022-01033-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bersuker K., Hendricks J.M., Li Z., Magtanong L., Ford B., Tang P.H., Roberts M.A., Tong B., Maimone T.J., Zoncu R., et al. The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis. Nature. 2019;575:688–692. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown C.W., Amante J.J., Chhoy P., Elaimy A.L., Liu H., Zhu L.J., Baer C.E., Dixon S.J., Mercurio A.M. Prominin2 drives ferroptosis resistance by stimulating iron export. Dev. Cell. 2019;51:575–586.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yi J., Zhu J., Wu J., Thompson C.B., Jiang X. Oncogenic activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling suppresses ferroptosis via SREBP-mediated lipogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:31189–31197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2017152117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiernicki B., Maschalidi S., Pinney J., Adjemian S., Vanden Berghe T., Ravichandran K.S., Vandenabeele P. Cancer cells dying from ferroptosis impede dendritic cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:3676. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31218-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hassannia B., Vandenabeele P., Vanden Berghe T. Targeting ferroptosis to iron out cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:830–849. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao J., Luo T., Wang J. Gene interfered-ferroptosis therapy for cancers. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:5311. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25632-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarangelo A., Magtanong L., Bieging-Rolett K.T., Li Y., Ye J., Attardi L.D., Dixon S.J. p53 suppresses metabolic stress-induced ferroptosis in cancer cells. Cell Rep. 2018;22:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu S., Mao C., Kondiparthi L., Poyurovsky M.V., Olszewski K., Gan B. A ferroptosis defense mechanism mediated by glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 2 in mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2121987119. e2121987119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koppula P., Lei G., Zhang Y., Yan Y., Mao C., Kondiparthi L., Shi J., Liu X., Horbath A., Das M., et al. A targetable CoQ-FSP1 axis drives ferroptosis- and radiation-resistance in KEAP1 inactive lung cancers. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:2206. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29905-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y., Shi J., Liu X., Feng L., Gong Z., Koppula P., Sirohi K., Li X., Wei Y., Lee H., et al. BAP1 links metabolic regulation of ferroptosis to tumour suppression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018;20:1181–1192. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0178-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friedmann Angeli J.P., Schneider M., Proneth B., Tyurina Y.Y., Tyurin V.A., Hammond V.J., Herbach N., Aichler M., Walch A., Eggenhofer E., et al. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:1180–1191. doi: 10.1038/ncb3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rayavarapu R.R., Heiden B., Pagani N., Shaw M.M., Shuff S., Zhang S., Schafer Z.T. The role of multicellular aggregation in the survival of ErbB2-positive breast cancer cells during extracellular matrix detachment. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:8722–8733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.612754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu X., Taftaf R., Kawaguchi M., Chang Y.F., Chen W., Entenberg D., Zhang Y., Gerratana L., Huang S., Patel D.B., et al. Homophilic CD44 interactions mediate tumor cell aggregation and polyclonal metastasis in patient-derived breast cancer models. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:96–113. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-18-0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aceto N., Bardia A., Miyamoto D.T., Donaldson M.C., Wittner B.S., Spencer J.A., Yu M., Pely A., Engstrom A., Zhu H., et al. Circulating tumor cell clusters are oligoclonal precursors of breast cancer metastasis. Cell. 2014;158:1110–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheung K.J., Padmanaban V., Silvestri V., Schipper K., Cohen J.D., Fairchild A.N., Gorin M.A., Verdone J.E., Pienta K.J., Bader J.S., Ewald A.J. Polyclonal breast cancer metastases arise from collective dissemination of keratin 14-expressing tumor cell clusters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E854–E863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508541113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown C.W., Amante J.J., Mercurio A.M. Cell clustering mediated by the adhesion protein PVRL4 is necessary for α6β4 integrin-promoted ferroptosis resistance in matrix-detached cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:12741–12748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.003017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shen Y., Li X., Dong D., Zhang B., Xue Y., Shang P. Transferrin receptor 1 in cancer: a new sight for cancer therapy. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2018;8:916–931. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Torti S.V., Torti F.M. Iron and cancer: more ore to be mined. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013;13:342–355. doi: 10.1038/nrc3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kerins M.J., Ooi A. The roles of NRF2 in modulating cellular iron homeostasis. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2018;29:1756–1773. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dodson M., Castro-Portuguez R., Zhang D.D. NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2019;23:101107. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rojo de la Vega M., Chapman E., Zhang D.D. NRF2 and the hallmarks of cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:21–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sporn M.B., Liby K.T. NRF2 and cancer: the good, the bad and the importance of context. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:564–571. doi: 10.1038/nrc3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davison C.A., Durbin S.M., Thau M.R., Zellmer V.R., Chapman S.E., Diener J., Wathen C., Leevy W.M., Schafer Z.T. Antioxidant enzymes mediate survival of breast cancer cells deprived of extracellular matrix. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3704–3715. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-12-2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kang M.I., Kobayashi A., Wakabayashi N., Kim S.G., Yamamoto M. Scaffolding of Keap1 to the actin cytoskeleton controls the function of Nrf2 as key regulator of cytoprotective phase 2 genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2046–2051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308347100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao B., Li L., Wang L., Wang C.Y., Yu J., Guan K.L. Cell detachment activates the Hippo pathway via cytoskeleton reorganization to induce anoikis. Genes Dev. 2012;26:54–68. doi: 10.1101/gad.173435.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ubellacker J.M., Tasdogan A., Ramesh V., Shen B., Mitchell E.C., Martin-Sandoval M.S., Gu Z., McCormick M.L., Durham A.B., Spitz D.R., et al. Lymph protects metastasizing melanoma cells from ferroptosis. Nature. 2020;585:113–118. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2623-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hong X., Roh W., Sullivan R.J., Wong K.H.K., Wittner B.S., Guo H., Dubash T.D., Sade-Feldman M., Wesley B., Horwitz E., et al. The lipogenic regulator SREBP2 induces transferrin in circulating melanoma cells and suppresses ferroptosis. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:678–695. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao L., Wu X., Li T., Luo J., Dong D. ctcRbase: the gene expression database of circulating tumor cells and microemboli. Database. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1093/database/baaa020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown C.W., Amante J.J., Goel H.L., Mercurio A.M. The α6β4 integrin promotes resistance to ferroptosis. J. Cell Biol. 2017;216:4287–4297. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201701136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.