Abstract

This cohort study evaluates trends in the adoption of robotic surgery among Medicare beneficiaries and privately insured patients for common general surgical procedures.

Introduction

The extent to which the adoption of robotic surgery varies among patients with different insurance types is unknown. On the one hand, given that payments from private payers are, on average, 224% of Medicare payments, this difference in reimbursement may be a key factor associated with greater adoption of robotic surgery among privately insured patients.1 On the other hand, private and public payers may both balance concerns for higher costs by incentivizing the use of robotic surgery where it adds the most value (eg, transitioning from traditional open surgery to a minimally invasive approach). In this cohort study, we evaluated trends in adoption of robotic surgery among Medicare beneficiaries and privately insured patients for common general surgical procedures experiencing the most rapid increase in the use of the robotic platform.

Methods

We identified 2 cohorts of patients, Medicare Fee-for-Service beneficiaries and a group of privately insured patients in the MarketScan database, undergoing ventral hernia repair, inguinal hernia repair, colectomy, or proctectomy from January 1, 2010, through December 30, 2018. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision or International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes were used to identify procedures (eAppendix in Supplement 1). The University of Michigan institutional review board exempted the study and waived informed consent because this was a secondary analysis and data were deidentified, in accordance with 45 CFR §46. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines for cohort studies.

We used multivariate logistic regression to adjust longitudinal trends in the use of robotic, laparoscopic, and open approaches, accounting for patient age, sex, and Elixhauser comorbidities.2 Risk-adjusted proportions are shown throughout. Data were analyzed from July to August 2022 using STATA/MP statistical software version 17 (StataCorp).

Results

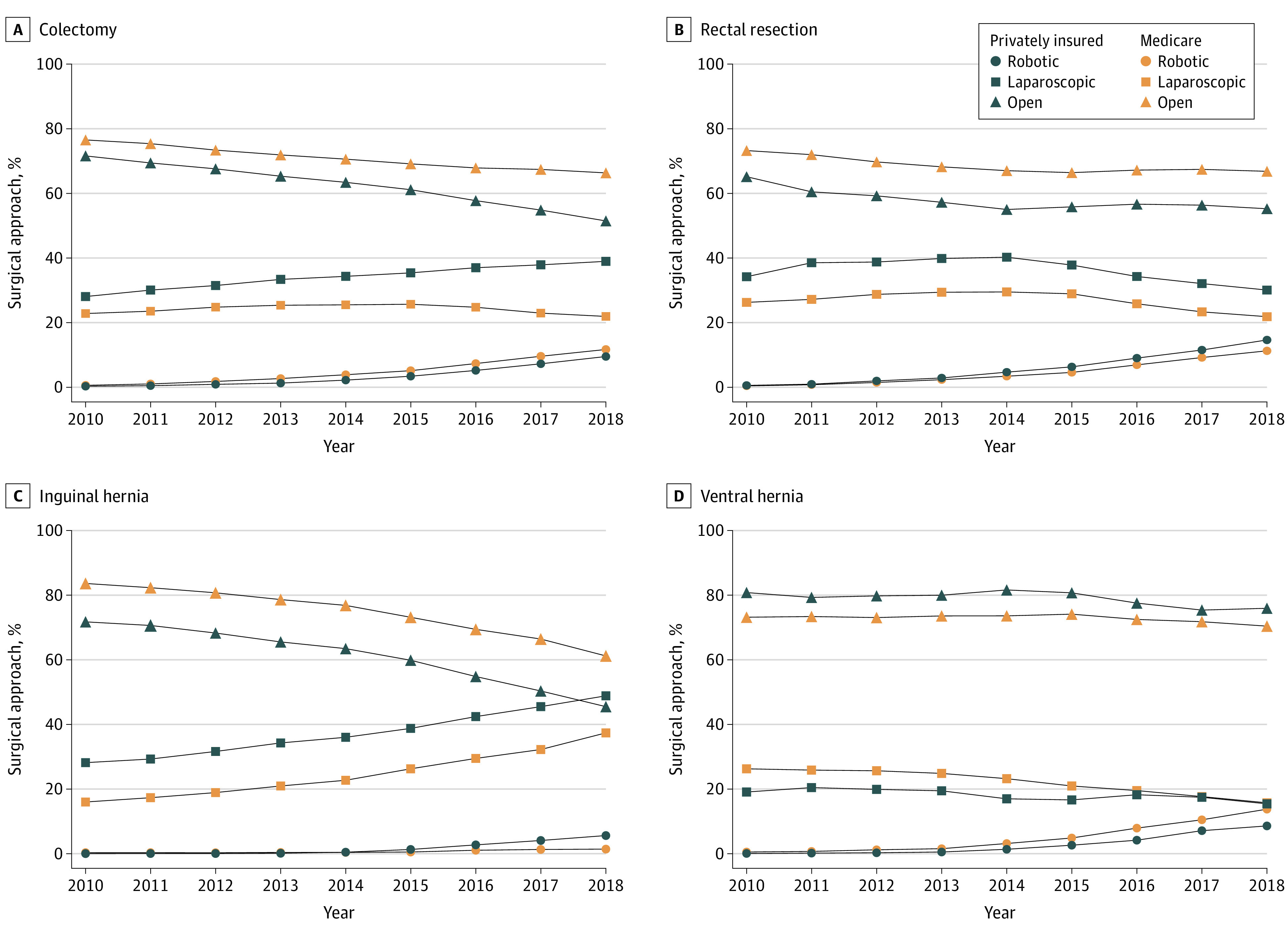

A total of 1 668 697 Medicare beneficiaries and 616 129 privately insured patients underwent the 4 operations studied. The use of robotic surgery for all operations increased from 0.5% in 2010 to 11.9% in 2018 among Medicare patients (22.3%-fold increase; change per year, 1.6%; 95% CI, 1.6%-1.6%) and from 0.3% to 9.2% among privately insured patients (29.6%-fold increase; change per year, 1.0%; 95% CI, 1.0%-1.0%) (Table). Overall, there was a decline in open surgery among Medicare beneficiaries and privately insured patients (−1.3% per year vs −2.4% per year) in the study period. Notably, for ventral hernia repair and colectomy, the trends in increased robotic adoption among both Medicare beneficiaries and privately insured patients was associated with a decrease in laparoscopic surgery (Figure). Colectomy had the largest increase in robotic use among Medicare patients, from 0.4% to 11.5% (29.1%-fold increase). In contrast, among privately insured patients, inguinal hernia repair had the largest increase in robotic utilization, from 0.04% to 5.5% (154.5%-fold increase).

Table. Trends in the Use of Robotic, Laparoscopic, and Open Surgery Among Medicare Beneficiaries and Privately Insured Patients by Specific Procedures, 2010-2018.

| Procedure | Medicare beneficiaries (n = 1 668 697)a | Privately insured patients (n = 616 129)b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operations per year, risk-adjusted % | Annual slope, % (95% CI)c | Fold differenced | Operations per year, risk-adjusted % | Annual slope, % (95% CI)c | Fold differenced | |||

| 2010 | 2018 | 2010 | 2018 | |||||

| Robotic | ||||||||

| All | 0.5 | 11.9 | 1.6 (1.6 to 1.6) | 22.3 | 0.3 | 9.2 | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.0) | 29.6 |

| Inguinal hernia repair | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.2) | 3.9 | 0.04 | 5.5 | 0.6 (0.6 to 0.7) | 154.5 |

| Ventral hernia repair | 0.5 | 13.8 | 1.7 (1.6 to 1.7) | 25.9 | 0.1 | 8.7 | 0.9 (0.9 to 1.0) | 90.0 |

| Colectomy | 0.4 | 11.5 | 1.6 (1.6 to 1.6) | 29.1 | 0.6 | 14.9 | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.6) | 24.8 |

| Proctectomy | 1.6 | 20.7 | 2.5 (2.4 to 2.5) | 13.2 | 2.3 | 22.7 | 2.3 (2.1 to 2.4) | 10.0 |

| Laparoscopic | ||||||||

| All | 21.4 | 22.2 | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.06) | 1.0 | 27.9 | 39.6 | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.5) | 1.4 |

| Inguinal hernia repair | 16.1 | 37.5 | 2.6 (2.5 to 2.7) | 2.3 | 28.0 | 49.3 | 2.6 (2.5 to 2.7) | 1.8 |

| Ventral hernia repair | 25.8 | 15.9 | −1.3 (−1.4 to −1.2) | 0.6 | 19.0 | 15.5 | −0.5 (−0.6 to −0.3) | 0.8 |

| Colectomy | 24.1 | 22.3 | −0.4 (−0.4 to −0.3) | 0.9 | 33.8 | 30.8 | −0.4 (−0.5 to −0.3) | 0.9 |

| Proctectomy | 3.9 | 14.8 | 1.9 (1.9 to 2.0) | 3.8 | 4.6 | 14.1 | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.6) | 3.1 |

| Open | ||||||||

| All | 78.2 | 65.9 | −1.5 (−1.5 to −1.4) | 0.8 | 71.8 | 51.0 | −2.5 (−2.5 to −2.4) | 0.7 |

| Inguinal hernia repair | 83.5 | 61.1 | −2.7 (−2.8 to −2.6) | 0.7 | 71.9 | 45.1 | −3.2 (−3.2 to −3.1) | 0.6 |

| Ventral hernia repair | 73.7 | 70.2 | −0.3 (−0.4 to −0.2) | 1.0 | 80.9 | 75.9 | −0.5 (−0.6 to −0.3) | 0.9 |

| Colectomy | 75.7 | 66.2 | −1.0 (−1.0 to −0.98) | 0.9 | 65.6 | 54.3 | −1.3 (−1.4 to −1.2) | 0.8 |

| Proctectomy | 94.7 | 64.6 | −4.3 (−4.3 to −4.2) | 0.7 | 93.1 | 63.2 | −3.7 (−3.8 to −3.5) | 0.7 |

For Medicare beneficiaries undergoing surgery between 2010 and 2018, data were collected from MEDPAR files.

For privately insured patients undergoing surgery between 2010 and 2018, data were collected from MarketScan.

Refers to annual increase or decrease in the proportional use of each approach by operation.

Fold difference was defined by dividing the proportional use of a given approach in 2018 by the proportional use in 2010.

Figure. Temporal Trends in the Proportional Use of Robotic, Laparoscopic, and Open Surgery Among Privately Insured Patients vs Medicare Beneficiaries.

Graphs show data for surgical trends in colectomy (A), rectal resection (B), inguinal hernia (C), and ventral hernia (D) from 2010 to 2018.

Discussion

The findings of this cohort study demonstrate that the adoption of robotic surgery for common general surgical procedures was similar between Medicare Fee-for-Service beneficiaries and privately insured patients. This suggests that potential differences in reimbursement and potential differences in consumer preferences between younger patients with employee-sponsored insurance compared with older adults with Medicare do not appear to be associated with adoption. However, for both cohorts, the magnitude of increase in robotic surgery adoption appears to outpace the relative increase in laparoscopic approaches and decrease in open approaches. Similar to prior findings,3 we found evidence for the replacement of both open and laparoscopic techniques with robotic surgery for common operations. The replacement of laparoscopic surgery with robotic approaches requires ongoing evaluation given the unclear clinical benefits and increase costs and resource allocation.4,5

Our results should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. This study is limited by changes in patient and surgeon factors that may contribute to surgical approach, such as complexity of hernia repair or increased training in robotic surgery by surgical trainees and practicing surgeons.5 However, given the lack of consensus regarding patient selection for robotic approaches and variation in surgeon robotic training, inclusion of these factors could introduce potential bias.6 Furthermore, our study does not address how nonclinical factors, such as advertisement of robotic surgery, may contribute to patient preference for robotic approaches regardless of payer. Research centered on the evaluation adoption of robotic surgery will require ongoing considerations of hospital, surgeon, and patient factors.

eAppendix. Codes Used for Operations

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Whaley CM, Briscombe B, Kerber R, O’Neill B, Kofner A. Prices paid to hospitals by private health plans: findings from round 4 of an employer-led transparency initiative. RAND Corporation. July 1, 2022. Accessed April 14, 2023. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1144-1.html [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheetz KH, Claflin J, Dimick JB. Trends in the adoption of robotic surgery for common surgical procedures. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1918911. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khorgami Z, Li WT, Jackson TN, Howard CA, Sclabas GM. The cost of robotics: an analysis of the added costs of robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic surgery using the National Inpatient Sample. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(7):2217-2221. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6507-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prabhu AS, Carbonell A, Hope W, et al. Robotic inguinal vs transabdominal laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: the RIVAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(5):380-387. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen R, Rodrigues Armijo P, Krause C, Siu KC, Oleynikov D; SAGES Robotic Task Force . A comprehensive review of robotic surgery curriculum and training for residents, fellows, and postgraduate surgical education. Surg Endosc. 2020;34(1):361-367. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-06775-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Codes Used for Operations

Data Sharing Statement