Key Points

Question

Is there an association between false memories and delusions among individuals with current or future Alzheimer disease who undergo behavioral testing or volumetric neuroimaging?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 728 participants from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort who were diagnosed with Alzheimer disease during follow-up, false recognition was not associated with the presence of delusions when accounting for confounding variables. On volumetric neuroimaging, there was no overlap in brain regions associated with delusions and those associated with false recognition.

Meaning

These findings suggest that delusions experienced by individuals with Alzheimer disease do not arise as a direct consequence of forgetting or misremembering and further support the existence of a transdiagnostic mechanism for psychosis.

This cross-sectional study uses behavioral testing and volumetric neuroimaging data to examine the association between false memories and delusions among individuals in the Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort.

Abstract

Importance

Understanding the mechanisms of delusion formation in Alzheimer disease (AD) could inform the development of therapeutic interventions. It has been suggested that delusions arise as a consequence of false memories.

Objective

To investigate whether delusions in AD are associated with false recognition, and whether higher rates of false recognition and the presence of delusions are associated with lower regional brain volumes in the same brain regions.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Since the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) launched in 2004, it has amassed an archive of longitudinal behavioral and biomarker data. This cross-sectional study used data downloaded in 2020 from ADNI participants with an AD diagnosis at baseline or follow-up. Data analysis was performed between June 24, 2020, and September 21, 2021.

Exposure

Enrollment in the ADNI.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcomes included false recognition, measured with the 13-item Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog 13) and the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) and volume of brain regions corrected for total intracranial volume. Behavioral data were compared for individuals with delusions in AD and those without using independent-samples t tests or Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests. Significant findings were further explored using binary logistic regression modeling. For neuroimaging data region of interest analyses using t tests, Poisson regression modeling or binary logistic regression modeling and further exploratory, whole-brain voxel-based morphometry analyses were carried out to explore the association between regional brain volume and false recognition or presence of delusions.

Results

Of the 2248 individuals in the ADNI database, 728 met the inclusion criteria and were included in this study. There were 317 (43.5%) women and 411 (56.5%) men. Their mean (SD) age was 74.8 (7.4) years. The 42 participants with delusions at baseline had higher rates of false recognition on the ADAS-Cog 13 (median score, 3; IQR, 1 to 6) compared with the 549 control participants (median score, 2; IQR, 0 to 4; U = 9398.5; P = .04). False recognition was not associated with the presence of delusions when confounding variables were included in binary logistic regression models. An ADAS-Cog 13 false recognition score was inversely associated with left hippocampal volume (odds ratio [OR], 0.91 [95% CI, 0.88-0.94], P < .001), right hippocampal volume (0.94 [0.92-0.97], P < .001), left entorhinal cortex volume (0.94 [0.91-0.97], P < .001), left parahippocampal gyrus volume (0.93 [0.91-0.96], P < .001), and left fusiform gyrus volume (0.97 [0.96-0.99], P < .001). There was no overlap between locations associated with false recognition and those associated with delusions.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study, false memories were not associated with the presence of delusions after accounting for confounding variables, and no indication for overlap of neural networks for false memories and delusions was observed on volumetric neuroimaging. These findings suggest that delusions in AD do not arise as a direct consequence of misremembering, lending weight to ongoing attempts to delineate specific therapeutic targets for treatment of psychosis.

Introduction

Dementia is one of the greatest challenges to global health and is the seventh leading cause of death globally.1 More than half of dementia diagnoses are Alzheimer disease (AD),2 costing the UK economy greater than £25 billion (US $31 billion) annually. In AD, delusions (fixed false beliefs) can be divided into 2 subtypes: (1) persecutory, often involving theft or personal harm, and (2) misidentification, including misidentification phenomena and/or hallucinations.3,4 Up to 50% of individuals with AD experience these symptoms, which can be highly distressing, reduce quality of life for patients and caregivers, and precipitate early institutionalization.5,6,7,8 Antipsychotic medications are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality in individuals with AD,9,10,11 and it is imperative that safer treatment approaches are identified. Research that enhances our understanding of the cognitive neuroscience of delusion formation in the context of AD would help to more effectively target nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment strategies.12

In addition to their susceptibility to delusions, up to 90% of individuals with AD experience memory-related false beliefs (false memories),13 including confabulation (giving false information without being aware of it), intrusion errors, misremembering word lists, false recognition of novel stimuli, and distortions in autobiographical memory.14 False memories may be associated with high-risk behaviors, such as missing medication doses due to falsely remembering taking them.15 They also reduce functional ability and increase caregiver distress.16,17

Conceptually, it has been suggested that false memories and delusions are part of a continuum.18 In healthy individuals, false memories correlate with subclinical delusional ideation.19 Individuals with schizophrenia, particularly those with current psychosis symptoms, are more prone to false recognition on memory testing.20,21,22,23 There is preliminary evidence of an association between false memories and delusions in AD, with 2 previous studies reporting higher scores on measures of confabulation in individuals with delusions.24,25 These studies had small sample sizes (<25 participants with delusions) and did not control for confounding variables, so further exploration of the association between false memories and delusions in AD is warranted.

Delusions become more common as global cognitive function declines.5 In 2014, Sultzer et al26 found an association between delusions and impaired short-term memory, measured with the memory subscale of the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale, replicating a finding by Jeste et al27 in 1992. Furthermore, hypometabolism in the right temporal cortex (including the middle, inferior, fusiform gyrus [FFG], and parahippocampal gyrus [PHG]) in participants with AD with greater Mattis Dementia Rating Scale memory impairment overlapped with a region of hypometabolism (including the middle temporal gyrus [MTG] and PHG) also associated with delusions.26 Deficits in visual attention and recognition are also associated with delusions in AD. Individuals with delusions in AD perform more poorly on both the Rapid Visual Information Processing Test and the Incomplete Letters Test of the Visual Object and Space Perception Battery,28 and they have increased brain atrophy in associated ventral visual stream brain regions.28,29 Specifically, individuals with delusions in AD are reported to have lower left PHG volume.29 Frontal cortical networks are also linked to delusional symptoms in AD, with primarily right-sided structural and functional changes identified on neuroimaging and evidence of executive dysfunction on behavioral testing.3,4,30 These findings support the hypothesis that delusions in AD may share neurocognitive foundations with impairments in specific domains of cognitive function.

The aim of the study was to investigate the association between false memories and delusions in AD and to determine whether they have a shared neuropathology, indexed by regional brain volume.

This study hypothesized that (1) individuals with delusions in AD would have more false memories than those without delusions when matched for severity of global cognitive impairment and (2) both false recognition and the presence of delusions would correlate with reduced volume of structures in the medial temporal lobe (MTL), ventral visual stream, prefrontal cortex (PFC), anterior cingulate cortex, or superior parietal lobules.

Methods

Sample

For this cross-sectional study, data were downloaded from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Institute (ADNI) database31 on March 26, 2020. The ADNI launched in 2004, with the aim of identifying biomarkers by which to diagnose and track progression of AD. The database has an extensive archive of behavioral and neuroimaging data for individuals with AD, those with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and control participants who were considered to be cognitively normal. Each of the 59 participating sites has received ethical approval, and all participants provide informed written consent for involvement. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

To maximize the number of individuals with delusions at baseline, ADNI participants who met the study criteria were included from all ADNI phases. Criteria for enrollment in the ADNI are described in detail elsewhere and are presented in eTable 1 in Supplement 1.32,33 Additional study exclusion criteria were as follows: no diagnosis of AD34 at any time point, Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)35 or Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q)36 not completed at baseline, inconsistent diagnosis of AD through follow-up (if a participant reverted to amnestic MCI), baseline magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of insufficient quality for analysis, and false memory measures not completed. Carer-rated NPI and NPI-Q data from all available time points were used to determine whether participants developed delusions. Delusions were considered to be present if a participant scored 1 or more on the NPI-Q delusions item or answered yes to the NPI delusions domain. The control group included participants who experienced no delusions at any time point. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores were used as a measure of overall cognitive function, and category fluency for animals was used as a measure of executive function, as poor performance on measures of executive function is associated with increased false memories.37 Demographic details were compared between individuals with and without delusions using independent-samples t tests or using Mann-Whitney tests if parametric assumptions were violated. Race and ethnicity data were obtained for the ADNI database by self-report. Race data were extracted for the purpose of this study to aid consideration of representativeness of the sample and generalizability of the results.

False Memory Measures

Two behavioral measures routinely completed at ADNI visits included a measure of false memories: the 13-item Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog 13) and the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT). The ADAS-Cog 13 includes a word recognition task of 12 target words and 12 distractor words. Positive responses to distractors (maximum score of 12) were used as an index of false memories. The RAVLT includes a word recognition task of 15 target words and 15 distractor words. The total number of intrusions (maximum score of 120) and positive responses to distractors (maximum score of 15) were used as false memory measures. Discrimination and response bias were calculated for false recognition on both tasks, as in Macmillan.38

MRI Acquisition and Image Processing

Baseline MRI scans were used. Scanner hardware differs among ADNI sites and the MRI protocol changes between ADNI phases.39 Raw T1-weighted sagittal images were downloaded. Image processing was performed using Statistical Parametric Mapping, version 12 (SPM12; University College London), and the Computational Anatomy Toolbox for SPM12 (CAT12), version 7 (r1725; University of Jena).

All MRI scans were individually reviewed for movement artifact and the origin was manually reset to the anterior commissure. Images were processed using the CAT12 Geodesic Shooting pipeline, with graph-cut skull stripping and segmentation. Gray matter volumes were estimated in milliliters for regions of interest (ROIs) using the Neuromorphometrics atlas.40 Gray matter image files were smoothed at 8-mm full width, half maximum prior to whole-brain exploratory voxel-based morphometry (VBM) analysis. The CAT12 measures of image quality were reviewed.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed in SPSS, version 27 (IBM SPSS), with results considered significant at P < .05 (2 tailed). Confounding variables were determined a priori, including age, sex, years of education, MMSE score, cholinesterase inhibitor or memantine prescription, and category fluency for animals. The MRI field strength was included as a covariate for ROI analyses and total intracranial volume (TIV) for VBM analyses. Data analysis was performed between June 24, 2020, and September 21, 2021.

Behavioral Data

Baseline characteristics and task performance were compared between (1) individuals with delusions at baseline and the control group as well as (2) those with delusions at any time point and the control group. Where there was a statistically significant difference in false memory measures, comparisons were rerun excluding outliers and individuals who were cognitively normal at baseline. This was done to confirm that significant results were not an artifact of larger numbers of cognitively normal participants in the control group. Binary logistic regression including confounding variables was then used to further explore statistically significant findings.

Neuroimaging Data

We selected ROIs based on the a priori hypotheses described earlier and corrected for global brain volume by calculating each ROI as a proportion of TIV. Associations between measures of false recognition and ROI volume (as a proportion of TIV) were explored using Poisson regression modeling corrected for overdispersion with the Pearson χ2/degrees of freedom value as described by McCullagh and Nelder.41 For the results of regression analyses, we express change in ROI volume (as a proportion of TIV) as a percentage of overall mean ROI volume for ease of interpretation. Covariates were assessed for collinearity using variance inflation factor scores (threshold of <2.5),42 Pearson residuals were plotted, and statistically significant models were rerun excluding outliers above a conservative threshold for Cook distance43 and individuals who were cognitively normal at baseline.

Prior to VBM analysis, continuous variables were mean centered. Explicit threshold masking was applied using a majority mask as described by Ridgway et al.44 The T contrasts were run to explore both positive and negative correlations between performance on false memory measures and brain volume, with a familywise error (FWE) correction applied and an extent threshold of k = 10. Because positive and negative correlations were run separately, P values were doubled prior to comparison with the significance threshold. Design orthogonality matrices were viewed to assess for collinearity.

We compared the TIV-corrected gray matter volume for ROIs (1) between participants with delusions at baseline and the control group and (2) between those with delusions at any time point and the control group, first using independent-samples t tests and then binary logistic regression models including confounding variables. An exploratory whole-brain VBM analysis was performed to further identify any associations between regional volume and delusion group.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the 2248 individuals in the ADNI database, 728 met the inclusion criteria and were included in this study. There were 317 (43.5%) women and 411 (56.5%) men. Their mean (SD) age was 74.8 (7.4) years, and 16 participants (2.2%) were Asian, 25 (3.4%) were Black, 681 (93.5%) were White, and 6 (0.8%) were of multiple races. A total of 386 participants (53.0%) were diagnosed with AD at baseline and 585 (80.4%) were diagnosed after 2 years of follow-up. The mean (SD) baseline MMSE score among participants was 25.1 (2.9) (scores range from 0 to 30; a higher score indicates better performance). Delusions were present at baseline in 42 participants and at a later time point in a further 137 participants. The 42 participants with delusions at baseline and the 179 participants with delusions at baseline or any other time point were compared with the remaining 549 participants who formed the control group. A breakdown of psychosis symptoms by subtype was only available for the 32 participants with delusions at baseline for whom a full NPI was completed (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). The participant selection flow chart is provided in eFigure 1 in Supplement 1.

Between-group differences in demographic details and baseline assessments are reported in Table 1. Participants with delusions at baseline differed substantially from the control group in presence of hallucinations, race, diagnosis at baseline, antipsychotic prescribing, NPI-Q score (range, 0-36; a higher score indicates greater burden of neuropsychiatric symptoms), MMSE score, and category fluency for animals.

Table 1. Demographic Details and Baseline Screening Assessment Resultsa.

| Characteristic | Control group (n = 549)b | Group with delusions at baseline (n = 42) | Group with delusions at any time point (n = 179) | Control group vs group with delusions at baselinec | Control group vs group with delusions at any time pointc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 74.8 (7.5) | 76.0 (6.4) | 75.0 (7.2) | t589 = 1.01; P = .31 | t726 = −0.31; P = .76 |

| Sex | |||||

| Women | 224 (40.8) | 18 (42.9) | 93 (52.0) | χ2 = .07; P = .79 | χ2 = 6.83; P = .009 |

| Men | 325 (59.2) | 24 (57.1) | 86 (48.0) | ||

| Right-handed | 504 (91.8) | 38 (90.5) | 169 (94.4) | P = .77d | χ2 = 1.17; P = .33 |

| Education, y, mean (SD) | 15.6 (2.8) | 15.6 (2.8) | 15.4 (2.9) | t589 = 0.12; P = .91 | t726 = 0.89; P = .37 |

| Hallucinations at baseline | 8 (1.5) | 7 (16.7) | 16 (8.9) | P < .001d | χ2 = 23.70; P < .001 |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

| Asian | 12 (2.2) | 2 (4.8) | 4 (2.2) | P = .04d | P = .06d |

| Black | 13 (2.4) | 4 (9.5) | 12 (6.7) | ||

| White | 519 (94.5) | 36 (85.7) | 162 (90.5) | ||

| Multiple racese | 5 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Diagnosis | |||||

| Cognitively normal | 21 (38.3) | 0 | 6 (3.4) | P = .003d | χ2 = 2.75; P = .25 |

| Amnestic MCI | 228 (41.5) | 8 (19.0) | 87 (48.6) | ||

| Alzheimer disease | 300 (54.6) | 34 (81.0) | 86 (48.0) | ||

| Medication | |||||

| ChEI or memantine | 400 (73.0) | 34 (81.0) | 123 (68.7) | χ2 = 1.27; P = .28 | χ2 = 1.22; P = .27 |

| Antidepressant | 179 (32.7) | 17 (40.5) | 72 (40.2) | χ2 = 1.07; P = .31 | χ2 = 3.41; P = .07 |

| Antipsychotic | 4 (0.7) | 4 (9.5) | 6 (3.4) | P = .001d | P = .02d |

| Screening assessment | |||||

| NPI-Q score, median (IQR)f | 1 (0 to 3) | 7 (5 to 9) | 3 (1 to 6) | U = 3032.0; P < .001 | U = 35 917.0; P < .001 |

| MMSE score, mean (SD)g | 25.0 (2.9) | 23.4 (2.7) | 25.1 (2.9) | t589 = −3.53; P < .001 | t726 = −0.10; P = .92 |

| GDS-15 score, median (IQR)h | 1 (1 to 2) | 1 (0 to 3) | 1 (1 to 2) | U = 10 948.0; P = .58 | U = 48 397.0; P = .76 |

| Category fluency score, mean (SD)i | 14.0 (5.4) | 11.5 (4.5) | 13.8 (4.9) | t588 = 2.92; P = .004 | t725 = 0.41; P = .68 |

Abbreviations: ChEI, cholinesterase inhibitor; GDS-15, short-form Geriatric Depression Scale; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NPI-Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire.

Unless indicated otherwise, values are presented as No. (%) of participants.

In the control group, there were 548 participants each for medication and category fluency.

For means (SDs), t values are presented with degrees of freedom. For medians (IQRs), U values are presented.

P value from the Fisher exact test.

Indicates participant self-reported as “more than 1 race” when demographic details were collected by Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative researchers.

Scores range from 0 to 36, where a higher score indicates greater burden of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Scores range from 0 to 30, where a higher score indicates better performance.

Scores range from 0 to 15, where a higher score indicates more symptoms of depression.

Score measured as the No. of animals named by the participant in 60 seconds, where a higher score indicates better performance.

One scan was removed due to motion artifact. The comparison between this individual and the remaining sample is presented in eTable 3 in Supplement 1.

False Memory Measures in Participants With Delusions vs Control Participants

Participants with delusions at baseline had higher rates of false recognition on the ADAS-Cog 13 and poorer discrimination performance on the RAVLT, with no significant difference between the groups on any other false memory measure (Table 2). All results remained statistically significant after excluding outliers and those who were cognitively normal at baseline. There were no significant differences between individuals with delusions at any time point and control participants for any false memory measure, discrimination, or response bias.

Table 2. Performance on False Memory Measures for Individuals With Delusions at Baseline vs the Control Groupa.

| False memory measure | Control group (n = 549)b | Group with delusions at baseline (n = 42)c | Control group vs group with delusions at baselined |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADAS-Cog 13 | |||

| False recognition (maximum total score of 12) | 2 (0 to 4) | 3 (1 to 6) | U = 9398.5; P = .04 |

| Discrimination | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.1) | 1.3 (0.8 to 1.6) | U = 9451.0; P = .05 |

| Response bias, mean (SD) | −0.1 (0.6) | −0.0 (0.7) | t594 = −1.29; P = .20 |

| RAVLT | |||

| False recognition (maximum total score of 15) | 2 (1 to 4) | 2.5 (1 to 4) | U = 9806.0; P = .11 |

| Discrimination | 1.1 (0.5 to 1.7) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.1) | U = 8738.5; P = .009 |

| Response bias | −0.4 (−0.8 to −0.1) | −0.5 (−0.8 to −0.1) | U = 11 078.5; P = .69 |

| Intrusions (maximum total score of 120) | 4 (2 to 9) | 6 (2 to 8) | U = 10 245.0; P = .55 |

Abbreviations: ADAS-Cog 13, 13-item Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale; RAVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

Unless indicated otherwise, values are presented as the median (IQR).

In the control group, there were 548 participants for RAVLT false recognition and 543 for RAVLT intrusions.

In the group with delusions, there were 40 participants for RAVLT intrusions.

For means (SDs), t values are presented with degrees of freedom. For medians (IQRs), U values are presented.

False recognition on the ADAS-Cog 13 or RAVLT was not associated with the presence of delusions when confounding factors were included in binary logistic regression models. Only MMSE score was associated with delusions in the models (eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

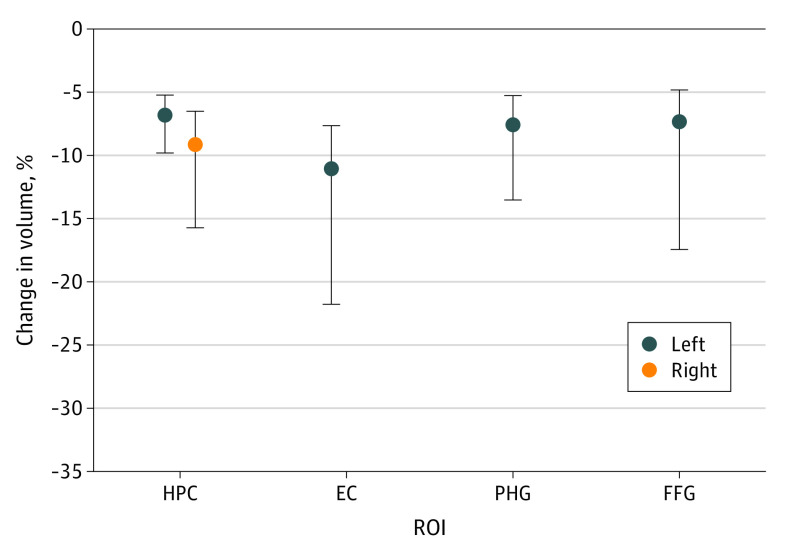

Brain Regions Associated With False Memories

All models that assessed the association between prespecified ROIs, confounding variables, and false recognition on either the ADAS-Cog 13 or the RAVLT revealed an overall association. Within the models, there was an inverse association between volume of several ROIs and number of words falsely recognized (Table 3). Following Bonferroni correction, an association remained between false recognition on the ADAS-Cog 13 and volume of MTL ROIs (hippocampus bilaterally and left entorhinal cortex) and ventral visual stream ROIs (left PHG and FFG) (Figure 1 and Table 3). Associations were observed for all models assessing intrusions on RAVLT; however, no ROI reached individual significance within any model.

Table 3. Association Between the Volume of Regions of Interest (ROIs) and False Recognition Testsa.

| Mean (SD) change in ROI volume per unit, % | ADAS-Cog 13 false recognition models (n = 725) | RAVLT false recognition models (n = 725) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | Percent change in score per unit | OR (95% CI) | P value | Percent change in score per unit | ||

| ROI | |||||||

| Hippocampus | |||||||

| Left | 7.4 (1.6) | 0.91 (0.88-0.94) | <.001b | 9.1 | 0.96 (0.93-0.99) | .008 | 4.0 |

| Right | 6.6 (3.2) | 0.94 (0.92-0.97) | <.001b | 6.0 | 0.98 (0.96-1.01) | .23 | NA |

| Entorhinal cortex | |||||||

| Left | 8.1 (1.9) | 0.94 (0.91-0.97) | <.001b | 6.1 | 0.97 (0.94-1.00) | .03 | 3.2 |

| Right | 7.8 (1.8) | 0.95 (0.92-0.98) | .001 | 5.2 | 0.97 (0.94-1.00) | .05 | NA |

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | |||||||

| Left | 3.9 (0.6) | 0.98 (0.96-1.00) | .03 | 2.3 | 0.99 (0.97-1.01) | .14 | NA |

| Right | 5.2 (1.0) | 0.97 (0.95-1.00) | .01 | 2.6 | 0.98 (0.96-1.00) | .08 | NA |

| Superior parietal lobule | |||||||

| Left | 1.9 (0.3) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | .11 | NA | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | .33 | NA |

| Right | 1.9 (0.3) | 0.99 (0.98-1.01) | .27 | NA | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | .99 | NA |

| Ventral visual stream | |||||||

| Parahippocampal gyrus | |||||||

| Left | 6.0 (1.1) | 0.93 (0.91-0.96) | <.001b | 6.6 | 0.96 (0.94-0.99) | .02 | 3.6 |

| Right | 6.1 (1.2) | 0.96 (0.94-0.99) | .01 | 3.7 | 0.97 (0.94-1.00) | .03 | 3.1 |

| Fusiform gyrus | |||||||

| Left | 2.3 (0.3) | 0.97 (0.96-0.99) | <.001b | 2.6 | 0.99 (0.98-1.01) | .36 | NA |

| Right | 2.4 (0.4) | 0.98 (0.97-1.00) | .01 | 1.9 | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | .10 | NA |

| Lingual gyrus | |||||||

| Left | 2.3 (0.3) | 0.99 (0.98-1.01) | .31 | NA | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | .76 | NA |

| Right | 2.2 (0.3) | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | .74 | NA | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | .43 | NA |

| Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | |||||||

| Middle frontal gyrus | |||||||

| Left | 1.0 (0.1) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | .01 | 0.9 | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | .28 | NA |

| Right | 1.0 (0.1) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | .008 | 0.9 | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | .15 | NA |

| Superior frontal gyrus | |||||||

| Left | 1.3 (0.1) | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | .20 | NA | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | .01 | 1.2 |

| Right | 1.3 (0.1) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | .02 | 1.1 | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | .07 | NA |

| Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex | |||||||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | |||||||

| Left | 5.7 (0.9) | 0.96 (0.93-0.99) | .007 | 4.0 | 0.98 (0.95-1.00) | .08 | NA |

| Right | 5.6 (0.9) | 0.98 (0.95-1.01) | .11 | NA | 0.98 (0.96-1.01) | .23 | NA |

| Inferior frontal orbital gyrus | |||||||

| Left | 11.7 (1.8) | 0.97 (0.91-1.03) | .29 | NA | 1.00 (0.94-1.06) | .93 | NA |

| Right | 12.1 (1.8) | 0.97 (0.91-1.03) | .29 | NA | 1.01 (0.95-1.07) | .83 | NA |

| Inferior frontal angular gyrus | |||||||

| Left | 5.7 (0.9) | 0.98 (0.95-1.01) | .12 | NA | 1.01 (0.98-1.04) | .59 | NA |

| Right | 5.6 (0.8) | 0.98 (0.95-1.02) | .30 | NA | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | .87 | NA |

| Medial prefrontal cortex | |||||||

| Superior medial frontal gyrus | |||||||

| Left | 3.0 (0.4) | 0.97 (0.96-0.99) | .009 | 2.7 | 0.98 (0.96-1.00) | .04 | 2.0 |

| Right | 2.5 (0.4) | 0.98 (0.97-1.00) | .02 | 1.8 | 0.98 (0.97-1.00) | .02 | 1.6 |

| Medial frontal cerebrum | |||||||

| Left | 11.3 (2.2) | 0.95 (0.91-1.00) | .06 | NA | 0.96 (0.92-1.01) | .12 | NA |

| Right | 10.6 (1.9) | 0.95 (0.90-0.99) | .02 | 5.4 | 0.96 (0.92-1.01) | .11 | NA |

| Orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex | |||||||

| Lateral orbital gyrus | |||||||

| Left | 8.2 (1.1) | 0.98 (0.93-1.03) | .41 | NA | 1.00 (0.96-1.05) | .87 | NA |

| Right | 7.7 (1.0) | 1.00 (0.95-1.05) | .92 | NA | 0.99 (0.95-1.04) | .66 | NA |

Abbreviations: ADAS-Cog 13, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale, 13 item; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; RAVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

Poisson regression models include the following covariates: age, sex, years of education, Mini-Mental State Examination score, cholinesterase inhibitor prescription, category fluency for animals, and magnetic resonance imaging field strength.

Survived Bonferroni correction (P < .001).

Figure 1. Change in Region of Interest (ROI) Volume per Additional Word Falsely Recognized on the 13-Item Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog 13).

Dots represent the change in mean ROI volume per additional word falsely recognized on the ADAS-Cog 13; whiskers represent the 95% CI. EC indicates entorhinal cortex; FFG, fusiform gyrus; HPC, hippocampus; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus.

Model diagnostics are presented in eTable 5 in Supplement 1, and they indicated good model fit by the parameters described. The ROIs that survived Bonferroni correction remained significant when excluding outliers (left hippocampus: odds ratio [OR], 0.90 [95% CI, 0.88-0.93], P < .001; right hippocampus: 0.94 [95% CI, 0.92-0.97], P < .001; left entorhinal cortex: 0.93 [95% CI, 0.91-0.96], P < .001; left PHG: 0.94 [95% CI, 0.91-0.96], P < .001; and left FFG: 0.98 [95% CI, 0.96-0.99], P < .001) and those who were cognitively normal at baseline (left hippocampus: OR, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.89-0.94], P < .001; right hippocampus: 0.94 [95% CI, 0.92-0.97], P < .001; left entorhinal cortex: 0.94 [95% CI, 0.91-0.97], P < .001; left PHG: 0.94 [95% CI, 0.91-0.96], P < .001; and left FFG: 0.98 [95% CI, 0.96-0.99], P = .001).

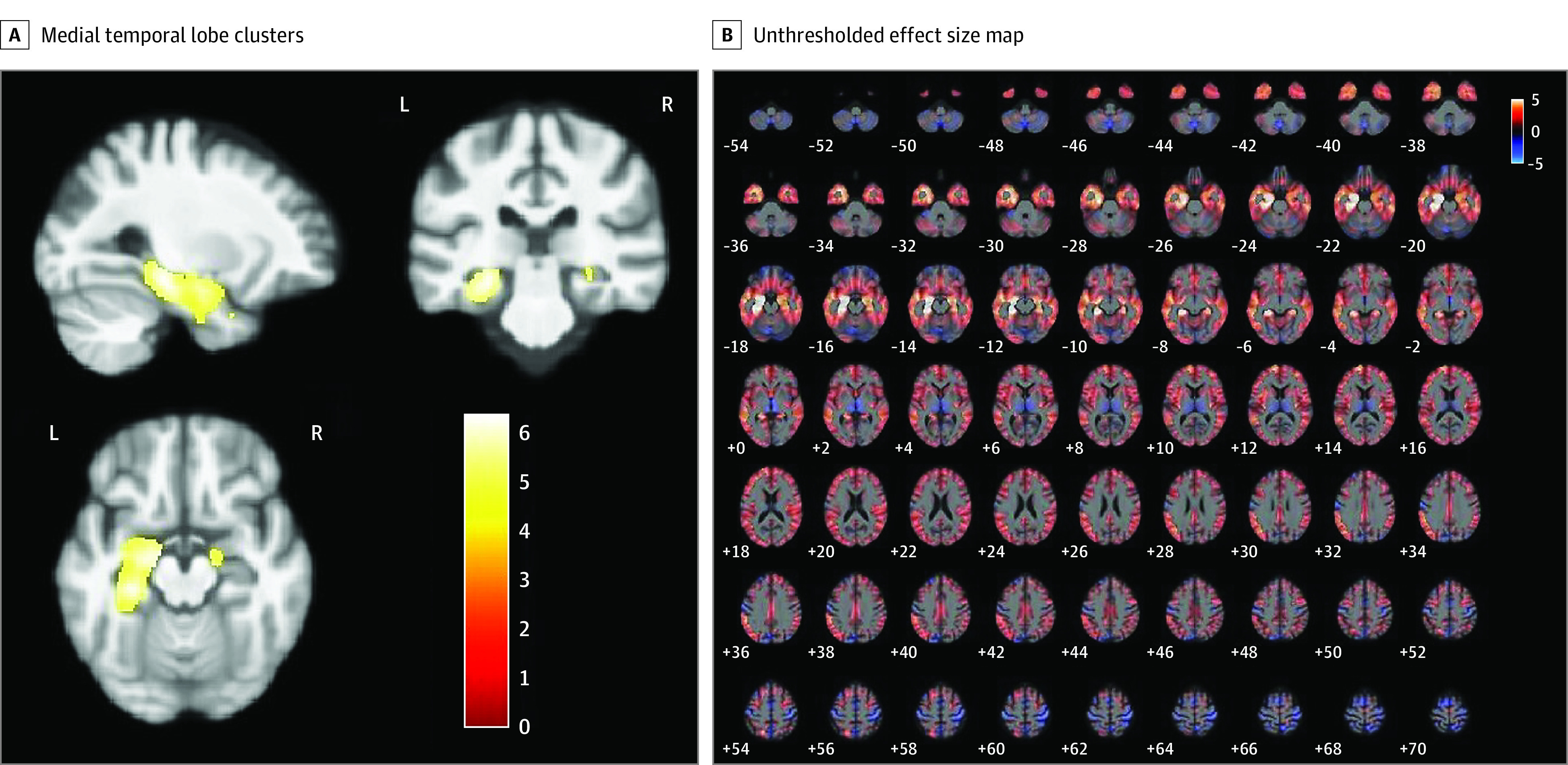

On VBM analysis, the model for false recognition on the ADAS-Cog 13 revealed an inverse association between false recognition and gray matter volume in the right hippocampus (Montreal Neurological Institute space coordinates of peak voxel: x = 17, y = −11, z = −14, k = 76, Z = 5.01, and FWE-corrected P = .02; and x = 29, y = −29, z = −9, k = 40, Z = 4.53, and FWE-corrected P = .04), left FFG (x = −27, y = −29, z = −15, k = 3220, Z = 6.27, and FWE-corrected P < .001), and left MTG (x = −35, y = 9, z = −33, k = 100, Z = 4.92, and FWE-corrected P = .01) that was significant at the cluster level (Figure 2A). The unthresholded effect size map for the model is displayed in Figure 2B. Design orthogonality matrices are presented in eFigure 2 in Supplement 1.

Figure 2. False Recognition Model Using the 13-Item Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog 13).

A, Medial temporal lobe clusters with an inverse association with false recognition on the ADAS-Cog 13. B, Unthresholded T-contrast effect size map for the association between false recognition on the ADAS-Cog 13 and gray matter volume. Color bars represent the t-statistic.

Brain Regions Associated With Delusions

In participants with delusions at baseline, the right anterior cingulate cortex was significantly smaller as a proportion of TIV compared with the control group, with values of 1.87 ± 0.39 × 10−3 and 1.99 ± 0.35 × 10−3, respectively (t589 = 2.15; P = .03). However, this finding was no longer significant when Bonferroni correction was applied or when confounding factors were included in the regression model (OR, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.83-1.00], P = .05). The right PHG was the only ROI that achieved individual significance within regression models for presence of delusions at baseline (OR, 1.15 [95% CI, 1.00-1.31], P = .047; eTable 6 in Supplement 1). Delusions at baseline were associated with increased right PHG volume (as a proportion of TIV) (OR, 1.15 [95% CI, 1.00-1.31], P = .047). This finding did not survive Bonferroni correction. None of the regression models for those with delusions at any time point reached statistical significance. On VBM analysis, no clusters reached statistical significance.

Discussion

In line with our hypothesis, the initial results of this cross-sectional study suggested that participants with delusions at baseline had higher rates of false recognition on the ADAS-Cog 13. However, the association did not survive the inclusion of multiple confounding variables in regression models. On ROI analysis, there was an inverse association between false recognition on the ADAS-Cog 13 and volumes of ROIs within the MTL (hippocampus bilaterally and left entorhinal cortex) and ventral visual stream (left PHG and FFG). None of the associations between ROI volume and delusions survived Bonferroni correction, nor was there overlap with areas associated with false recognition. This lack of association between delusions and false recognition is in contrast with 2 previous studies24,25 that reported greater confabulation in patients with AD with delusions. However, as discussed, these studies had small sample sizes and did not control for confounding variables.24,25

Our results confirm a role for the MTL and ventral visual stream in false memories in AD. Both the hippocampus45,46,47,48 and the entorhinal cortex49,50,51 are known to be crucial for recognition memory. Individuals with hippocampal lesions demonstrate a combination of impaired recollection with preserved familiarity, thought to predispose to false recognition.52,53 Reduced left hippocampal (and PHG) volume was previously associated with increased false recognition on the RAVLT in a smaller group of 77 individuals with AD.54 The PHG and FFG are part of the hippocampal-PFC network of context encoding and retrieval.55,56,57 Activity in the PHG and left FFG is observed during correct recognition on recognition memory testing and thus has been implicated in distinguishing true from false memories.58,59 Our data confirm these findings, as lower volumes of left PHG and FFG were associated with increased false memories.

Although we observed no overlap between the neural networks involved in false memories and delusions, the brain regions in which reduced volume was associated with increased false recognition have been associated with psychosis symptoms in AD in other cohorts. Lower right hippocampal volume has been consistently linked to psychosis symptoms in AD,60,61,62 with left entorhinal atrophy in AD recently reported to increase risk of psychosis.60 The MTL is part of a network involved in encoding and retrieval of memory for spatial and temporal context, mediated via functional connections to the PFC.63,64 It has been hypothesized that MTL volume loss, and subsequent dysfunction within this network, leads to psychosis as a result of impaired ability to attribute context to sensory input, causing increased prediction errors and delusion formation.65 Lower PHG volume has been observed in individuals with current delusions in AD, and prospectively in those who go on to develop delusions,29,66 and right FFG atrophy has also been associated with AD psychosis.67

In this study, delusions at baseline were associated with increased right PHG volume. Although this did not survive Bonferroni correction, it may indicate a potential role of asymmetry in delusion formation in AD. Rightward asymmetry of PHG volume has also been found when comparing individuals with AD with those with MCI and healthy older adults,68 and it may thus be a marker of disease severity rather than a causal factor in delusion formation. However, limited data suggest a possible role for right PHG overactivity in delusion formation in schizophrenia. Surguladze et al69 found that individuals with schizophrenia had reduced right PHG activity in response to fearful faces and increased activity in response to neutral faces compared with control participants, with increased activity correlating with the degree of reality distortion. Kirino et al70 observed that right PHG activity on functional MRI correlated with the severity of positive symptoms.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the number of participants with delusions at baseline was relatively small. This is unsurprising, given the relatively mild severity of AD in the sample. It is therefore reassuring that including participants with delusions at any time point also did not show any association between delusions and regional brain volume. Of note, we were unable to explore our findings by psychosis subtype. Given that the subtypes are associated with distinct neural correlates, this may have obfuscated the results and may go some way to explain why no frontal lobe involvement was identified.

Overlap in cognitive function between participants with MCI and early AD is acknowledged, making correctly diagnosing these individuals challenging.71 As the ADNI cutoff for cognitively normal participants is an MMSE score of 24, we included individuals who were diagnosed with AD at any time point in order to maximize sample size. This introduced further diagnostic heterogeneity. However, cognitive function (measured by the MMSE) was included as a covariate in analyses, which may go some way in controlling for this. It cannot be completely ruled out that a proportion of participants had undiagnosed Lewy body dementia or posterior cortical atrophy, although a previous analysis of atrophy in the posterior cortex and visuospatial deficits in ADNI participants did not reveal the deterioration over time that would be expected with a posterior cortical atrophy diagnosis.72 Relying on the carer-rated NPI to determine the presence of delusions has limitations, as carers may have been unaware of infrequently experienced unusual beliefs. In addition, the nature of longitudinal research with set follow-up time points means that some occurrences of delusions could have been missed. We chose variables to include in regression models a priori; in balancing potential contributing confounding factors with the risk of multicollinearity and overfitting of models, we did not include antipsychotic use, presence of hallucinations, or biomarkers.

The retrospective nature of this study meant that we did not use a validated false memory test and had to repurpose components of available test data. In terms of neuroimaging methodology, while including participants from the entire database allowed a larger sample size, the inclusion of data acquired from different imaging protocols was a substantial source of heterogeneity. However, previous VBM analyses using structural MRI data from participants with AD across multiple sites and scanners have reported minimal confounding of results73,74 and magnetic field strength was included as a confounding variable in our analyses. As is the case for all research using structural MRI, limitations include the inability to infer causality from patterns of atrophy and poor reproducibility of MRI findings across studies.75,76

Conclusions

The findings of this cross-sectional study suggest that despite the superficial resemblances, delusions in AD are more than simply an extension of memory errors or confabulation. Furthermore, these findings suggest that psychosis in AD is a valid target for pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment approaches and support the existence of a transdiagnostic mechanism for psychosis.

eTable 1. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

eTable 2. Breakdown and Classification of Psychosis Symptoms at Baseline (n = 32)

eFigure 1. Participant Selection Flow Chart

eTable 3. Comparison Between Remaining Sample and Participant Excluded Due to Poor Scan Quality

eTable 4. Binary Logistic Regression Modeling to Predict Presence of Delusions at Baseline

eTable 5. Region of Interest Analysis Model Diagnostics

eFigure 2. Voxel-Based Morphometry (VBM) Design Orthogonality Matrices

eTable 6. Comparison of Volume in Identified Regions of Interest Between Those With Delusions at Baseline and the Control Group

Nonauthor Collaborators. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global status report on the public health response to dementia. 2021. Accessed January 19, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033245

- 2.Prince M, Jackson J. World Alzheimer Report 2009. Alzheimer’s Disease International. 2009. Accessed January 19, 2022. https://www.alzint.org/resource/world-alzheimer-report-2009/. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reeves SJ, Gould RL, Powell JF, Howard RJ. Origins of delusions in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(10):2274-2287. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ismail Z, Nguyen M-Q, Fischer CE, Schweizer TA, Mulsant BH, Mamo D. Neurobiology of delusions in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(3):211-218. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0195-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ropacki SA, Jeste DV. Epidemiology of and risk factors for psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a review of 55 studies published from 1990 to 2003. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(11):2022-2030. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee S, Smith SC, Lamping DL, et al. Quality of life in dementia: more than just cognition. An analysis of associations with quality of life in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):146-148. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.072983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magni E, Binetti G, Bianchetti A, Trabucchi M. Risk of mortality and institutionalization in demented patients with delusions. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1996;9(3):123-126. doi: 10.1177/089198879600900303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern Y, Tang MX, Albert MS, et al. Predicting time to nursing home care and death in individuals with Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 1997;277(10):806-812. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540340040030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maust DT, Kim HM, Seyfried LS, et al. Antipsychotics, other psychotropics, and the risk of death in patients with dementia: number needed to harm. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(5):438-445. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al. ; CATIE-AD Study Group . Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1525-1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider LS, Dagerman K, Insel PS. Efficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(3):191-210. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000200589.01396.6d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geda YE, Schneider LS, Gitlin LN, et al. ; Neuropsychiatric Syndromes Professional Interest Area of ISTAART . Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: past progress and anticipation of the future. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(5):602-608. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turk KW, Palumbo R, Deason RG, et al. False memories: the other side of forgetting. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2020;26(6):545-556. doi: 10.1017/S1355617720000016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schacter DL. The seven sins of memory. Insights from psychology and cognitive neuroscience. Am Psychol. 1999;54(3):182-203. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El Haj M, Colombel F, Kapogiannis D, Gallouj K. False memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Neurol. 2020;2020:5284504. doi: 10.1155/2020/5284504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seltzer B, Vasterling JJ, Yoder JA, Thompson KA. Awareness of deficit in Alzheimer’s disease: relation to caregiver burden. Gerontologist. 1997;37(1):20-24. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steeman E, Abraham IL, Godderis J. Risk profiles for institutionalization in a cohort of elderly people with dementia or depression. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1997;11(6):295-303. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9417(97)80002-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson MK, Hashtroudi S, Lindsay DS. Source monitoring. Psychol Bull. 1993;114(1):3-28. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dehon H, Bastin C, Larøi F. The influence of delusional ideation and dissociative experiences on the resistance to false memories in normal healthy subjects. Pers Individ Dif. 2008;45(1):62-67. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.02.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brébion G, Amador X, Smith MJ, Malaspina D, Sharif Z, Gorman JM. Opposite links of positive and negative symptomatology with memory errors in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1999;88(1):15-24. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(99)00076-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brébion G, Amador X, David A, Malaspina D, Sharif Z, Gorman JM. Positive symptomatology and source-monitoring failure in schizophrenia—an analysis of symptom-specific effects. Psychiatry Res. 2000;95(2):119-131. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00174-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moritz S, Woodward TS. Memory confidence and false memories in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190(9):641-643. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200209000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhatt R, Laws KR, McKenna PJ. False memory in schizophrenia patients with and without delusions. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(2):260-265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee E, Meguro K, Hashimoto R, et al. Confabulations in episodic memory are associated with delusions in Alzheimer’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2007;20(1):34-40. doi: 10.1177/0891988706292760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee E, Akanuma K, Meguro M, Ishii H, Yamaguchi S, Meguro K. Confabulations in remembering past and planning future are associated with psychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22(8):949-956. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sultzer DL, Leskin LP, Melrose RJ, et al. Neurobiology of delusions, memory, and insight in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(11):1346-1355. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeste DV, Wragg RE, Salmon DP, Harris MJ, Thal LJ. Cognitive deficits of patients with Alzheimer’s disease with and without delusions. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(2):184-189. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.2.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reeves SJ, Clark-Papasavas C, Gould RL, Ffytche D, Howard RJ. Cognitive phenotype of psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for impaired visuoperceptual function in the misidentification subtype. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(12):1147-1155. doi: 10.1002/gps.4265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLachlan E, Bousfield J, Howard R, Reeves S. Reduced parahippocampal volume and psychosis symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(2):389-395. doi: 10.1002/gps.4757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian W, Schweizer TA, Churchill NW, et al. Gray matter changes associated with the development of delusions in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(5):490-498. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2018.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Institute . ADNI database. 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020. https://adni.loni.usc.edu/

- 32.Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Protocol. ADNI; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74(3):201-209. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cb3e25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939-944. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.7.939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308-2314. doi: 10.1212/WNL.44.12.2308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):233-239. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cunningham JM, Pliskin NH, Cassisi JE, Tsang B, Rao SM. Relationship between confabulation and measures of memory and executive function. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1997;19(6):867-877. doi: 10.1080/01688639708403767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macmillan NA. Signal detection theory as data analysis method and psychological decision model. In: Keren G, Lewis C, eds. A Handbook for Data Analysis in the Behavioral Sciences: Methodological Issues. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1993:21-57. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Institute . MRI acquisition. Accessed August 25, 2022. https://adni.loni.usc.edu/methods/mri-tool/mri-analysis/

- 40.Neuromorphometrics . Neuromorphometrics atlas. Accessed September 10, 2021. http://www.neuromorphometrics.com

- 41.McCullagh P, Nelder J. Generalized Linear Models II. Chapman and Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Brien RM. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant. 2007;41(5):673-690. doi: 10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fox J, ed. Outlying and influential data. In: Regression Diagnostics. SAGE; 1991:22-40. doi: 10.4135/9781412985604.n4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ridgway GR, Omar R, Ourselin S, Hill DL, Warren JD, Fox NC. Issues with threshold masking in voxel-based morphometry of atrophied brains. Neuroimage. 2009;44(1):99-111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eichenbaum H, Otto T, Cohen NJ. The hippocampus–what does it do? Behav Neural Biol. 1992;57(1):2-36. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(92)90724-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eichenbaum H, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C. The medial temporal lobe and recognition memory. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:123-152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wixted JT, Squire LR. The medial temporal lobe and the attributes of memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(5):210-217. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Squire LR, Wixted JT, Clark RE. Recognition memory and the medial temporal lobe: a new perspective. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(11):872-883. doi: 10.1038/nrn2154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sauvage MM, Beer Z, Ekovich M, Ho L, Eichenbaum H. The caudal medial entorhinal cortex: a selective role in recollection-based recognition memory. J Neurosci. 2010;30(46):15695-15699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4301-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yonelinas AP, Widaman K, Mungas D, Reed B, Weiner MW, Chui HC. Memory in the aging brain: doubly dissociating the contribution of the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. Hippocampus. 2007;17(11):1134-1140. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson DI, Langston RF, Schlesiger MI, Wagner M, Watanabe S, Ainge JA. Lateral entorhinal cortex is critical for novel object-context recognition. Hippocampus. 2013;23(5):352-366. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yonelinas AP, Quamme JR, Widaman KF, Kroll NE, Sauvé MJ, Knight RT. Mild hypoxia disrupts recollection, not familiarity. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2004;4(3):393-400. doi: 10.3758/CABN.4.3.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aggleton JP, Vann SD, Denby C, et al. Sparing of the familiarity component of recognition memory in a patient with hippocampal pathology. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43(12):1810-1823. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flanagan EC, Wong S, Dutt A, et al. False recognition in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease—disinhibition or amnesia? Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:177. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bar M, Aminoff E, Schacter DL. Scenes unseen: the parahippocampal cortex intrinsically subserves contextual associations, not scenes or places per se. J Neurosci. 2008;28(34):8539-8544. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0987-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eichenbaum H, Lipton PA. Towards a functional organization of the medial temporal lobe memory system: role of the parahippocampal and medial entorhinal cortical areas. Hippocampus. 2008;18(12):1314-1324. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weiner KS, Zilles K. The anatomical and functional specialization of the fusiform gyrus. Neuropsychologia. 2016;83:48-62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.06.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cabeza R, Rao SM, Wagner AD, Mayer AR, Schacter DL. Can medial temporal lobe regions distinguish true from false? an event-related functional MRI study of veridical and illusory recognition memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(8):4805-4810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081082698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Slotnick SD, Schacter DL. A sensory signature that distinguishes true from false memories. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(6):664-672. doi: 10.1038/nn1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee YM, Park JM, Lee BD, et al. The role of decreased cortical thickness and volume of medial temporal lobe structures in predicting incident psychosis in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective longitudinal MRI study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;30(1):46-53. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee K, Lee YM, Park JM, et al. Right hippocampus atrophy is independently associated with Alzheimer’s disease with psychosis. Psychogeriatrics. 2019;19(2):105-110. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Serra L, Perri R, Cercignani M, et al. Are the behavioral symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease directly associated with neurodegeneration? J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21(2):627-639. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burgess N, Maguire EA, Spiers HJ, O’Keefe J. A temporoparietal and prefrontal network for retrieving the spatial context of lifelike events. Neuroimage. 2001;14(2):439-453. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jenkins LJ, Ranganath C. Prefrontal and medial temporal lobe activity at encoding predicts temporal context memory. J Neurosci. 2010;30(46):15558-15565. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1337-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tamminga CA, Stan AD, Wagner AD. The hippocampal formation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(10):1178-1193. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nakaaki S, Sato J, Torii K, et al. Neuroanatomical abnormalities before onset of delusions in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a voxel-based morphometry study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.D’Antonio F, Di Vita A, Zazzaro G, et al. Psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease: neuropsychological and neuroimaging longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(11):1689-1697. doi: 10.1002/gps.5183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang C, Zhong S, Zhou X, Wei L, Wang L, Nie S. The abnormality of topological asymmetry between hemispheric brain white matter networks in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:261. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Surguladze S, Russell T, Kucharska-Pietura K, et al. A reversal of the normal pattern of parahippocampal response to neutral and fearful faces is associated with reality distortion in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(5):423-431. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kirino E, Hayakawa Y, Inami R, Inoue R, Aoki S. Simultaneous fMRI-EEG-DTI recording of MMN in patients with schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0215023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):183-194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sun N, Mormino EC, Chen J, Sabuncu MR, Yeo BTT; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Multi-modal latent factor exploration of atrophy, cognitive and tau heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2019;201:116043. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stonnington CM, Tan G, Klöppel S, et al. Interpreting scan data acquired from multiple scanners: a study with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2008;39(3):1180-1185. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marchewka A, Kherif F, Krueger G, Grabowska A, Frackowiak R, Draganski B; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Influence of magnetic field strength and image registration strategy on voxel-based morphometry in a study of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(5):1865-1874. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johnson KA, Fox NC, Sperling RA, Klunk WE. Brain imaging in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(4):a006213. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weinberger DR, Radulescu E. Structural magnetic resonance imaging all over again. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(1):11-12. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

eTable 2. Breakdown and Classification of Psychosis Symptoms at Baseline (n = 32)

eFigure 1. Participant Selection Flow Chart

eTable 3. Comparison Between Remaining Sample and Participant Excluded Due to Poor Scan Quality

eTable 4. Binary Logistic Regression Modeling to Predict Presence of Delusions at Baseline

eTable 5. Region of Interest Analysis Model Diagnostics

eFigure 2. Voxel-Based Morphometry (VBM) Design Orthogonality Matrices

eTable 6. Comparison of Volume in Identified Regions of Interest Between Those With Delusions at Baseline and the Control Group

Nonauthor Collaborators. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative

Data Sharing Statement