Abstract

Aims: There are very few detailed post-mortem studies on idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH) and there is a lack of proper neuropathological criteria for iNPH. This study aims to update the knowledge on the neuropathology of iNPH and to develop the neuropathological diagnostic criteria of iNPH.

Methods: We evaluated the clinical lifelines and post-mortem findings of 29 patients with possible NPH. Pre-mortem cortical brain biopsies were taken from all patients during an intracranial pressure measurement or a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunt surgery.

Results: The mean age at the time of the biopsy was 70±8 SD years and 74±7 SD years at the time of death. At the time of death, 11/29 patients (38%) displayed normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment (MCI), 9/29 (31%) moderate dementia and 9/29 (31%) severe dementia. Two of the demented patients had only scarce neuropathological findings indicating a probable hydrocephalic origin for the dementia. Amyloid-β (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylated τ (HPτ) in the biopsies predicted the neurodegenerative diseases so that there were 4 Aβ positive/low Alzheimer’s disease neuropathological change (ADNC) cases, 4 Aβ positive/intermediate ADNC cases, 1 Aβ positive case with both low ADNC and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), 1 HPτ/PSP and primary age-related tauopathy (PART) case, 1 Aβ/HPτ and low ADNC/synucleinopathy case and 1 case with Aβ/HPτ and high ADNC. The most common cause of death was due to cardiovascular diseases (10/29, 34%), followed by cerebrovascular diseases or subdural hematoma (SDH) (8/29, 28%). Three patients died of a postoperative intracerebral hematoma (ICH). Vascular lesions were common (19/29, 65%).

Conclusions: We update the suggested neuropathological diagnostic criteria of iNPH, which emphasize the rigorous exclusion of all other known possible neuropathological causes of dementia. Despite the first 2 probable cases reported here, the issue of “hydrocephalic dementia” as an independent entity still requires further confirmation. Extensive sampling (with fresh frozen tissue including meninges) with age-matched neurologically healthy controls is highly encouraged.

Keywords: Hydrocephalus, Normal pressure hydrocephalus, Post-mortem, Neuropathology, Neurodegeneration

Introduction

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) has a classic triad of clinical symptoms: impaired cognition, urinary incontinence and gait disturbance [1]. NPH is considered idiopathic (iNPH) in the absence of known predisposing factors such as neurotrauma or hemorrhage [1],[2]. The surgical insertion of a shunt in order to bypass cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) usually eases the symptoms [3], but unfortunately the improvements often decline over the years [4]. A considerable number of the patients with iNPH seem to develop cognitive impairment, eventually reaching dementia, commonly due to concomitant Alzheimer’s disease (AD), frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), vascular degeneration, or compellingly due to iNPH by yet unknown neurodegenerative mechanisms [5],[6]. In the Norwegian population, the prevalence of iNPH is estimated to be approximately 22 cases per 100,000 people [7] and it is more common in the older age groups [8]. Recent studies reporting familiar aggregation indicate that iNPH may be an independent neurodegenerative disorder that potentially has its own specific molecular biological basis and etiology [9]. In a study of 10 patients – 9 of whom are included in this study – it was shown that signs of other diseases such as AD, corticobasal degeneration (CBD) and vascular lesions can be identified in the post-mortem brains of the patients suspected to have NPH [10]. The number of detailed post-mortem studies on iNPH is very small and there is a lack of defined and universally accepted neuropathological criteria for iNPH. The Kuopio NPH Registry (http://www.uef.fi/nph) consists of data on the patients with presumed NPH. They underwent intraventricular pressure (ICP) monitoring together with right frontal cortical biopsies from 1991 up until 2010. From 2010 onwards, the shunt surgery has included the cortical brain biopsy. This study contains 29 patients with full post-mortem neuropathological examinations and with clinical follow-ups after the procedures with the biopsies.

Materials and methods

Kuopio NPH registry

The Neurosurgical Department of Kuopio University Hospital (KUH) alone provides full-time acute and elective neurosurgical services for the KUH catchment population in Eastern Finland. The medical evaluation of the KUH Neurosurgery for possible NPH has contained a clinical examination by a neurologist and a neurosurgeon, a computed tomography (CT) or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, and a 24-h ICP monitoring together with a right frontal cortical biopsy up until 2010. In 2010, a 3-step prognostic test protocol was launched. First, CSF tap tests are performed on all patients with suspected NPH, where at least a 20% improvement in the gait speed in a 10-m walk is considered a positive result. In the second phase, those with negative tap tests undergo lumbar infusion tests, where a conductance of ≤ 10 is considered a positive result. In the third step, the participants with negative findings in both of the tests mentioned above undergo a 24-h monitoring of the ICP or undergo a shunt surgery based on a clinical and radiological evaluation. Brain biopsies are acquired from the patients who undergo the ICP monitoring or the CSF shunt surgery [11]. Kuopio NPH Registry includes (i) the clinical baseline and the follow-up data and (ii) other hospital diagnoses, medications and the causes of death from the national registries, as well as the autopsy findings. In this study, NPH is defined as a state with the typical clinical and imaging findings, and it is classified as iNPH when no predisposing factors are found. The shunt response may be present or absent.

Basic study cohort

From 1991 up until 2017, 879 patients with possible NPH had been studied with the diagnostic protocol described above including the right frontal cortical biopsies.

Final study cohort

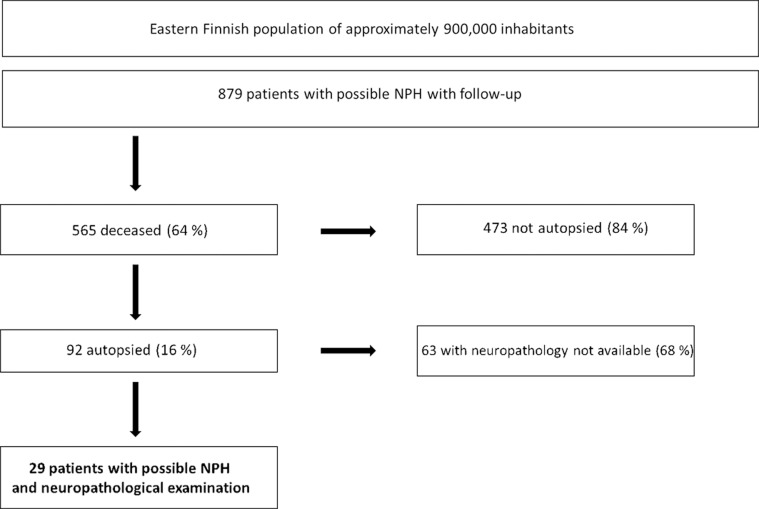

The construction of this study is outlined in Figure 1. The patients in this study cohort were followed up until their deaths. All clinical data available from the hospitals in the KUH catchment area was collected. Overall, 565 patients had died and 92 of them were autopsied, 29 of whom had had a full neuropathological examination. Out of the 29 patients, 23 were shunted according to the diagnostic procedure. The development of the clinical symptoms was documented by neurologists, general practitioners, or both. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was tested on 26 patients at the baseline. All available data was re-evaluated by 2 neurologists subspecialized in memory disorders (A. M. K. or H. S.), blinded for the cortical biopsy and the autopsy findings. Dementia was diagnosed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria [12]. The cognitive status was evaluated at the time of the biopsy and retrospectively at the time of death and classified as normal, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), moderate or severe dementia (bedridden).

Figure 1. Flow chart of 879 consecutive patients with possible NPH.

NPH = normal pressure hydrocephalus.

Radiological evaluation

All available CT and MRI scans were re-evaluated separately by 2 experienced neuroradiologists (A. S. and R. V.), blinded for the biopsy and the neuropathological findings. In the incongruent evaluations, a consensus reading was performed. Cortical and subcortical (lacunar) infarctions and cerebral white matter changes (WMCs) were especially looked for. The WMCs were categorized according to the modified Fazekas scale: no WMC (grade 0), punctuate (grade 1), early confluent (grade 2) and confluent (grade 3) [13].

Biopsy

The biopsy procedure has been described previously [14]. Briefly, 1 to 3 cylindrical right frontal cortical brain biopsies of 1-3 mm in diameter and 1-8 mm in length were obtained with biopsy forceps or a needle before inserting the intraventricular catheter for the 24-h ICP monitoring or the shunt. The samples were fixed in buffered formalin overnight and then embedded in paraffin.

Apolipoprotein E genotyping

DNA was extracted and the apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotypes were determined as described previously [15].

Autopsies and the neuropathological examination

The main findings and the causes of death were assessed from the original autopsy reports. The brains were stored in 10% buffered formaldehyde for at least 1 week before being cut into 1-cm-thick coronal slices and assessed macroscopically by a neuropathologist. The brain specimens were taken from 16 standard regions and embedded in paraffin. The included brain regions were: the frontal cortex, the temporal cortex, the cingular gyrus at the level of the mammillary bodies, the parietal cortex, the motor cortex, the occipital cortex, the anterior and the posterior hippocampus with the entorhinal cortex, the basal forebrain including the amygdala, the striatum, the thalamus, the midbrain, the pons, the medulla, the cerebellar vermis and the cortex [16]. Additional samples were taken if necessary for the diagnostics.

Histology and immunochemistry

The 7-μm sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated through the standard procedures. All sections were stained by using haematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and a selection of the sections also with immunohistochemical (IHC) methods. The antibodies used are described in Table 1. Shortly after the pretreatment, the sections were incubated with normal goat serum for 30 min at room temperature to block non-specific reactions. After unmasking the epitope, the antibodies were added to the dilution. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C. During the next day, the sections were incubated with a biotinylated second antibody for 30 min, followed by streptavidin enzyme conjugate (LABSA Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction products were visualized by using 3-amino-9-ethyl-carbazole (AEC) or 3-3’-diaminobenzidin (DAB). All immunostained sections were counterstained with Harris’ haematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted in DePex (BDH Chemicals, Hull, UK). An Amyloid-β (Aβ) staining was performed on the biopsies and 5 neuroanatomical regions (the frontal cortex, the hippocampus, the basal forebrain including the amygdala, the substantia nigra and the cerebellar cortex). Hyperphosphorylated tau (HPτ) was performed on the biopsies and 5 neuroanatomical regions (the temporal cortex, the occipital cortex, the anterior and the posterior hippocampus and the basal forebrain including the amygdala). An α-synuclein staining was performed on the biopsies and 7 neuroanatomical regions (the cingular gyrus, the parietal cortex, the posterior hippocampus, the substantia nigra, the pons, the medulla oblongata and the basal forebrain including the amygdala). Transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP43) was used on the biopsies and the posterior hippocampal sample. P62 was used on selected cases. All sections were evaluated with light microscopy by an experienced neuropathologist (T.R., J.R.). The pathology observed while applying the IHC techniques was assessed as described earlier [17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22]. In the biopsy samples, HPτ was classified as being present or absent and the type of the specific lesions was noted. The Aβ pathology was classified as being present in mild, moderate or extensive extent, and the vessel wall positivity was noted, suggesting cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Alzheimer’s disease neuropathological change (ADNC) was assessed according to the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association (NIA-AA) criteria [23].

Table 1. Immunohistochemistry.

HPτ = hyperphosphorylated τ, TDP43 = transactive response DNA-binding protein 43, AC = autoclave, CB = citrate buffer, FA = formic acid, DAB = 3-3’-diaminobenzidin, AEC = 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Biocare Medical).

| Antigen | Clone | Company | Pretreatment | Chromogen | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPτ | AT8 | Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium | None | DAB | 1:500 |

| p62 lck ligand | 3 | BD Biosciences Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA | AC at 120°C in 0.01 mol/l CB pH 6.0 | Romulin AEC | 1:1000 |

| Amyloid-β | 6F/3D | Dako | 80% FA 6h | DAB | 1:100 |

| α-synuclein | KM51 | Novocastra | AC in CB 80% 120°C FA 5 min | Romulin AEC | 1:1000 |

| TDP43 | 2E2-D3 | Abnova | AC in aqua, 120°C and FA 5 min | Romulin AEC | 1:1000 |

The statistical methods

SPSS Statistics (version 22.0 SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used for correlating Aβ in the biopsies and the autopsies.

Ethical issues

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Northern Savonia. All patients recruited after 2008 provided a written informed consent. Patient treated in neurosurgery prior to that, were studied according to the permissions from the Finnish National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health, and the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

Results

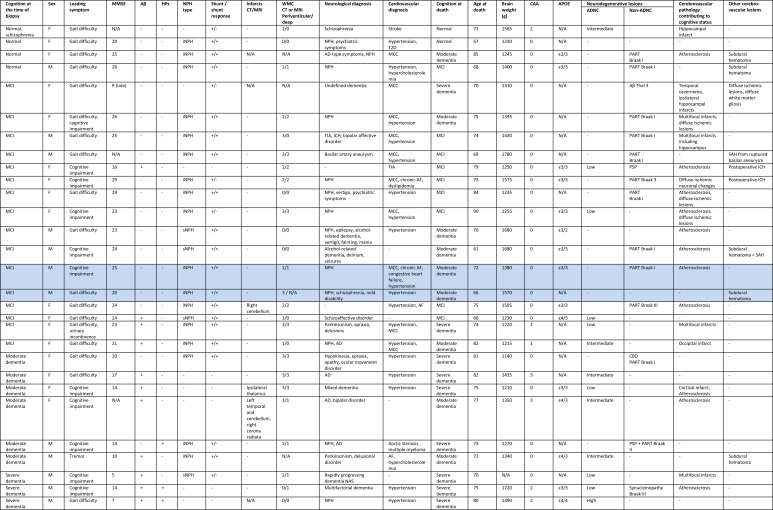

Demographics: The patient demographics, the clinical findings including the brain imaging and the cortical biopsies, are described in Table 2. More than half of the patients were female (17/29, 59%). The mean age at the time of the biopsy was 70±8 SD (standard deviation) years and 74±7 SD years at the time of death. The patients with clinically severe dementia died at the average age of 76±5 SD years. The age at death did not differ between the cognitively normal/MCI or the moderately demented patients. The follow-up time from the brain biopsy to the autopsy was 47±44 SD months, ranging from less than 1 month to 165 months.

Table 2. Patient characteristics at the time of the biopsies and the final clinical diagnoses.

* No amyloid-ß.

MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination, Aβ = Amyloid-β, HPτ = hyperphosphorylated τ, iNPH = idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus, CT = computerized tomography, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, WMC = white matter change (Fazekas grade [13] at least 1), PV = periventricular, NA = not available, AD = Alzheimer’s disease, HTA = arterial hypertension, CHD = coronary heart disease, T2D = type 2 diabetes.

| Cognition at the time of biopsy | n | Sex | Leading symptom (n) | MMSE mean±SD | Aβ (n) | HPτ (n) | iNPH (n) | Shunt / shunt response (n) | Infarcts CT/MRI | WMC CT/MRI (n) | Neurological diagnosis | Cardiovascular diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) | 20 | M 7 F 13 | Gait difficulty (15) Cognitive impairment (5) | 23±5 | 4/20 | 0/20 | 14/20 | 19/15 | 1 cortical grade 1, 2 lacunar grade 1, 1 lacunar grade 2 | PV: 9/20 NA (2/20) Deep: 8/20 NA(4/20) | Psychiatric disorders, (6/20), schizophrenia (2/20), AD-type dementia (2/20) | HTA (13/20), CHD (9/20), T2D (7/20) |

| Moderate dementia | 6 | M 2 F 4 | Cognitive impairment (3) Gait difficulty (2) Tremor (1) | 15±4 | 3/6 | 1*/6 | 3/6 | 3/2 | 1 cortical grade 2, 2 lacunar (grades 2 and 1) | PV: 5/6 NA (1/6) Deep: 5/6 NA (1/6) | AD (3/6), psychiatric disorders (2/6) | HTA (3/6), T2D (2/6) |

| Severe dementia | 3 | M 3 | Cognitive impairment (2) Gait difficulty (1) | 9±5 | 3/3 | 2/3 | 0/3 | 1/0 | - | PV: 1/3 Deep: 2/3 | “Rapidly progressing dementia”, non-specific dementia | HTA (2/3) |

Clinical findings: At the time of the clinical work-up and the cortical biopsy, the leading symptom was gait difficulty in 75% of the subjects with normal cognition or MCI (n=20). In the moderately demented group, half of the subjects (n=3/6) presented with cognitive impairment as the leading symptom, followed by gait difficulty (n=2) and tremors (n=1). In the severely demented group, 2 out of the 3 patients presented with cognitive impairment and 1 with gait difficulty as the leading symptom. In this study, iNPH is defined as a state in which the clinical findings, the imaging and the post-mortem findings are typically consistent with NPH, the predisposing factors are excluded, and the shunting procedure has been performed with a positive shunt response. Idiopathic NPH was seen in 70% of the subjects with normal cognition or MCI and 33% of the clinically demented subjects. Secondary NPH (sNPH) was seen in 3/20 (15%) of the subjects in the group with normal cognition or MCI.

The most common clinical diagnosis was hypertension (18/29, 62%), present in all groups. Other common clinical diagnoses were coronary heart disease, type II diabetes (T2D), AD, psychiatric disorders, cancer and asthma. Two of the patients in the group with normal cognition or MCI had clinically cognitive impairment related to alcohol, 1 patient presented with parkinsonism and 1 with epilepsy. Regarding the psychiatric morbidities, 1 patient had a history of schizoaffective disorder, 2 patients had schizophrenia and 2 had a long history of psychiatric symptoms and 1 of maniac episodes. No specific neuropathological findings were seen in this group.

Shunting: One patient in the group with normal cognition or MCI was not shunted and 15/19 (79%) of the shunted patients had positive responses. In the moderately demented group, 3/6 of the patients were shunted and 2 of them responded positively. One patient in the severely demented group (1/3) was shunted without a response.

Imaging: Radiologically, cortical and lacunar infarctions were found in the normal or MCI and the moderately demented groups. The findings are summarized in Table 2. The infarctions were of grades 1 and 2. Both periventricular and deep white matter changes were present in all groups. The changes ranged from grades 0 to 3.

Cortical biopsies: Aβ aggregates were seen in 10 patients: 4/20 (20%) in the group with normal cognition or MCI, 3/6 (50%) and 3/3 (100%) in the moderately and the severely demented groups, respectively. HPτ was not seen in the group with normal cognition or MCI. One patient in the moderately demented group had HPτ immunopositive lesions (without Aβ) and 2 out of the 3 patients in the severely demented group had HPτ positivity. Prominent HPτ pathology was seen upon the neuropathological examinations in all the 3 cases with HPτ in the biopsies. The presence of Aβ in the biopsies correlated with the extent of Aβ (Thal phase) [22] defined at the neuropathological examinations (Spearman’s r 0.775, P = 0.01).

At the time of death, 11/29 patients (38%) displayed normal cognition or MCI, 9/29 (31%) moderate dementia, and 9/29 (31%) severe dementia. The causes of death are described in Table 3. The most common cause of death was due to cardiovascular diseases (10/29, 34%), followed by cerebrovascular diseases (n=5/29, 17%) or acute subdural hematoma (SDH) (3/29, 10%), pneumonia (5/29, 17%) and metastatic carcinoma (4/29, 14%). Two patients died of postoperative intracerebral hematoma (ICH) indicating the 0.2% (2/879) risk of fatal ICH, related to the combined procedure of the brain biopsy and the insertion of the intraventricular catheter in the NPH population.

Table 3. Causes[HEG1] of death. [HEG1]Maybe cause of death ”ICH” should be added, as it is mentioned in the results section?

| Cause of death | Without dementia | With dementia | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | 5 | 5 | 10[HEG1] | 34 |

| Cerebrovascular or subdural hematoma | 2 | 4 | 6 | 21 |

| Pneumonia | 0 | 5 | 5 | 17 |

| Metastatic neoplasia | 0 | 4 | 4 | 14 |

| Intracerebral hematoma | 2 | 0 | 2 | 7 |

| Alcoholism with liver cirrhosis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Traumatic | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 29 | 100 |

Neuropathology: The neuropathological findings are described in Table 4. Enlarged ventricles were seen to variable degrees in all cases. The neuropathological examination revealed that in the group with normal cognition or MCI, almost half (5/11, 45%) of the patients had cerebrovascular atherosclerosis and more than a half (5/9, 55%) of the moderately demented patients had notable cerebrovascular atherosclerosis. All of the severely demented patients had cerebrovascular atherosclerosis to variable degrees. One patient in the least cognitively affected group had a ruptured basilar artery aneurysm resulting in subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), 1 had SDH and 1 patient had a hippocampal infarct. In the moderately demented group, 4 out of the 9 patients had acute SDH and 75% of these were traumatic in origin, and 1 patient had traumatic SAH. In the severely demented group, 1 patient had a multifocal metastatic (including meninges) carcinoma explaining the dementia, and 1 patient a temporal cavernoma with an ipsilateral hippocampal infarct. Multifocal brain infarcts sufficient to be causative for the cognitive decline were seen in 3 patients, 2 demented (occurred after the shunting procedure) and 1 with MCI (occurred during the year of death). In these patients, small lacunar infarctions were seen in the CT during the evaluation prior to the ICP measurement or the shunting. Gliosis in the subependymal region was seen in all cases to variable degrees and at least mild meningeal thickening was seen in 60% of the patients. The most common secondary findings are summarized in Table 5, among the pooled findings from previous literature reviewed in 2012 [10].

Table 4. Post-mortem neuropathological findings.

CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy, APOE = apolipoprotein E, NA = not available, ADNC = Alzheimer’s disease neuropathological change (NIA-AA [24]), PART = primary age-related tauopathy, PSP = progressive supranuclear palsy, CBD = corticobasal degeneration, Aβ = Amyloid-β deposition, ICH = Intracerebral hematoma, SAH = subarachnoidal hematoma, SDH = subdural hematoma.

| Cognitive status at death | n | Sex | Age at death ± (SD) | Brain weight (g) | CAA (n) | APOE | Neurodegenerative lesions | Cerebrovascular pathology contributing to cognitive status | Other cerebrovascular lesions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADNC | Non-ADNC | |||||||||

| Normal or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) | 11 | M 3 F 8 | 73±9 | 1413±19 | 1/11 | 10/11 ε3/3 (8/10) ε4/3 (1/10) ε3/2 (1/10) 1 NA | Low (3/11) Intermediate (1/11) High - | PART 6/11 PSP 1/11 | Cerebrovascular atherosclerosis 5/11 Infarct(s) 4/11 | Postoperative ICH (2/11) SAH (1/11) Acute SDH (1/11) |

| Moderate dementia | 9 | M 5 F 4 | 73±7 | 1428±17 | 2/9 | 3/9 ε4/3 (2/3) ε3/3 (1/3) | Low - Intermediate (3/9) High - | PART 4/9 | Cerebrovascular atherosclerosis (5/9) Infarct(s) (2/9) | Acute SDH (4/9) SAH (1/9) |

| Severe dementia | 9 | M 4 F 5 | 76±5 | 1349±19 | 4/9 | 2/9 ε3/3 (1) ε4/4 (1) | Low (4/9) Intermediate (1/9) High (1/9) | PART 2/9 CBD 1/9 PSP 1/9 Aβ 1/9 Synucleinopathy 1/9 | Infarct(s) 4/9 Cerebrovascular atherosclerosis (9/9) |

Table 5. Neuropathological findings in NPH.

NPH = normal pressure hydrocephalus, NA = not available, AD = Alzheimer’s disease.

| Neuropathological findings in NPH | Previous pooled studies (reviewed by Leinonen et al. 2012) | Cabral 2011 | Magdalinou 2013 | Del Bigio 2014 | McCarty 2019 | Present study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of cases | 40 | 9 | 4 | 28 | 1 post-mortem | 29 |

| Idiopathic NPH | 55% | NA | 0% | 18% | Yes | 58% |

| Cortical atrophy | 43% | No | 45% | |||

| Meningeal thickening | 64% | Yes | 60% | |||

| Subependymal gliosis | 60% | Yes | 77% | |||

| Periventricular white matter demyelination | 60% | 48% | ||||

| Vascular changes | 76% | 33% | 75% | 65% | ||

| AD-changes | 48% | 89% | No | 48% |

For ADNC evaluation, NIA-AA criteria were used [23]. Four of the subjects with normal cognition or MCI had ADNC and 6 had primary age-related tauopathy (PART) of Braak Stage III at maximum. One patient with low ADNC had also progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). In the moderately demented group, 3 had intermediate ADNC and 4 had Braak I PART. In the severely demented group, 6 patients had ADNC and 2 had PART. In addition, single cases of PSP, CBD, α-synucleinopathy and Aβ depositions of Thal stage 3 (without HPτ) were displayed. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) was seen in 1 out of the 11 subjects with normal cognition or MCI, 22% of the moderately demented patients and 44% of the severely demented patients.

The APOE genotype was found in 15/29 patients. At the time of biopsy, in the group with normal cognition or MCI, 8/10 (80%) had genotype ε3/3, 1 ε3/4 and 1 ε2/3. Among the moderately demented patients, 2/3 (67%) had the ε3/4 and 1 had the ε3/3 genotype. In the group of the severely demented patients, 1 had ε3/3 and 1 ε4/4 genotype.

Neuropathological WMCs in the form chronic vascular type were seen to a variable extent and did not correlate to the cognitive status.

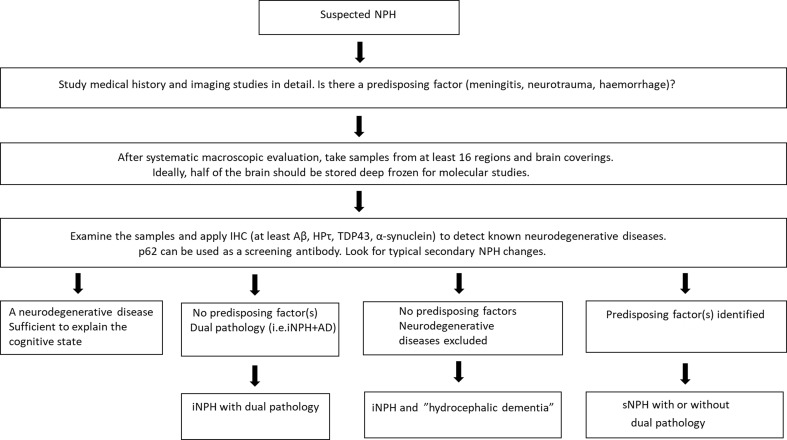

In Figure 2, we describe a model for the neuropathological evaluation of the NPH cases.

Figure 2. Our suggested model for neuropathological evaluation of NPH cases.

(i/s)NPH = (idiopathic/secondary) normal pressure hydrocephalus, IHC = immunohistochemistry, Aβ = Amyloid-β, HPτ = hyperphosphorylated τ, TDP43 = transactive response DNA-binding protein 43, AD = Alzheimer’s disease.

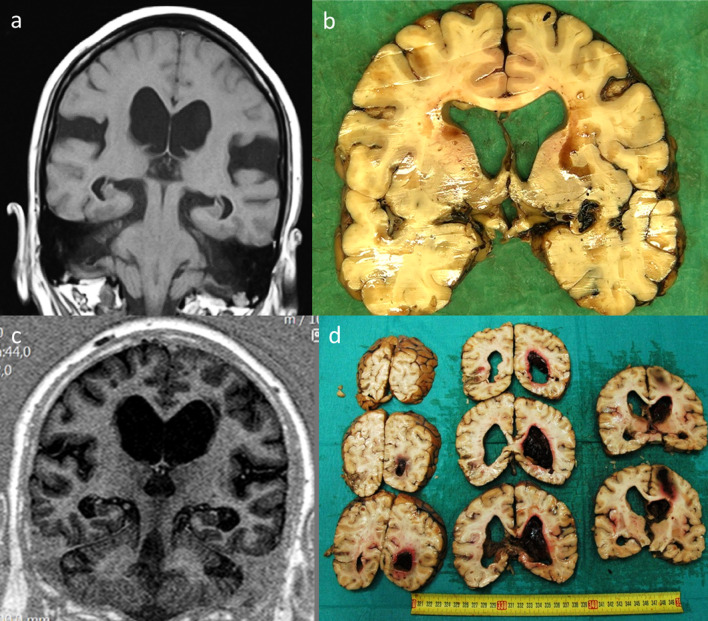

We present examples of radiological and post-mortem sectional findings in Figure 3. Figure 4 is the case-by-case representation of the patients. Two subjects with disproportionate neuropathological findings to the degree of cognitive impairment at death are highlighted, representing cases of probable “hydrocephalic dementia”.

Figure 3. Radiological and post-mortem sectional findings.

a: coronal MRI demonstrating ventricular enlargement pre-shunting, b: same case post-mortem section after shunting (time interval 2 years), c: coronal MRI demonstrating ventricular enlargement pre-shunting, d: intracerebral hematoma after the shunting procedure (time interval 3 months).

Figure 4. Case-by-case representation of the patients. Probable NPH-dementia subjects are highlighted. + = Yes, - = No.

MCI = mild cognitive impairment, MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination, Aβ = amyloid-β, HPτ = hyperphosphorylated τ, N/A = not available, (i/s)NPH = (idiopathic/secondary) normal pressure hydrocephalus, CT = computed tomography, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, WMC = white matter changes (Fazekas grades [13]), AD = Alzheimer’s disease, TIA = transient ischemic attack, ICH = intracerebral hematoma, T2D = type 2 diabetes, MCC = morbus cordis coronarius, AF = atrial fibrillation, CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy, APOE = apolipoprotein E, ADNC = Alzheimer’s disease neuropathological change, PART = primary age-related tauopathy, PSP = progressive supranuclear palsy, CBD = corticobasal degeneration, SAH = subarachnoid hemorrhage, ICH = intracerebral hemorrhage.

Discussion

Hakim and Adams [24] described the clinical triad of NPH, including the gait difficulty, the cognitive decline and the urinary incontinence, more than 50 years ago. Due to its relative rarity, iNPH is still a rather poorly understood disease and the number of studies with full systematic neuropathological examinations is limited. In this study, we describe the post-mortem findings in 29 patients with presumed NPH. Idiopathic NPH differs from most neurodegenerative diseases presenting with dementia, as the symptoms can be alleviated surgically [3],[25]. Idiopathic NPH mostly affects the elderly population. The median age of the patients studied here at the time of the diagnosis is comparable to previous studies [7],[26]. In this study, all patients were followed from the time of the shunting or the ICP monitoring up until their deaths, and cortical biopsies were taken from all subjects during the operation. Overall, in previous studies, the neuropathological findings have been reported to be highly variable and no specific findings of “hydrocephalic dementia” have been described up to date [10],[27],[28]. Del Bigio describes 5 patients with iNPH, 3 with sNPH and 20 patients in whom the ventriculomegaly could not be explained by the other disease processes identified. Neuropathologically, these groups did not differ [2].

The classical Hakim’s triad is only seen in full in 50% of the NPH cases [1]. In our study, gait difficulty was the most common leading symptom in the group with normal cognition or MCI. In the moderately demented group, half of the subjects presented clinically with cognitive impairment as the leading symptom and in the group of the severely demented patients, cognitive symptoms were more common than gait difficulty or incontinence. Previous studies have shown that more than 20% of the initially shunt-responsive iNPH patients develop AD later in life [5],[10]. The outcome of the shunting is more favorable if the procedure is done at the earlier stages of the disease [29],[30]. Therefore, the candidates for the shunting procedure need to be carefully selected as comorbid AD can make the shunting outcome less favorable [5],[31]. The correlation of Aβ seen in the biopsies and the overall Aβ load justify the use of the biopsies in the clinical evaluation, although many neurodegenerative diseases generally cannot be ruled out by examining a small cortical biopsy representing a small fraction of the brain tissue. However, HPτ in the biopsies predicted the neuropathological diagnosis of tauopathy or AD. Clinically, it is especially important to rule out other types of dementia in patients with cognitive impairment as the leading symptom [32]. The shunting procedure itself may results in complications such as postoperative ICH. In our study cohort, the neuropathological examination revealed that 2 patients had PSP and 1 CBD. In previous studies, it has been shown that PSP and Parkinson’s disease can clinically mimic iNPH [28],[33]. In this study, the most common neuropathological finding in the demented group was ADNC or early AD/PART, followed by multifocal infarcts. In the study published by Del Bigio and coworkers [34], significant co-morbidity was frequent in NPH. It is noteworthy that mixed diagnoses and co-pathologies are common especially in the elderly age groups [35]. McCarty et al. pointed out that a feature of NPH, disproportionately enlarged subarachnoid-space hydrocephalus (DESH), is often misdiagnosed as cortical atrophy [36].

In a recent study, it was shown that schizophrenia occurs 3 times more frequently among the iNPH patients when compared to the general population in Finland [37]. Studies using different imaging modalities have revealed that there are several progressive structural changes in the brains of the patients suffering from schizophrenia. The most common findings are the enlargements of the lateral ventricles and the reduction of the grey matter volume [38],[39] and the smaller hippocampi [40]. At the microanatomical level, various cytoarchitectural alterations such as a decreased number of neurons and increased neuronal densities in various neuronal populations have been reported [41]. In our study, we did not use a stereological methodology to quantify the cytoarchitectural alterations. Overall, our cases with comorbid psychiatric diseases did not differ from the other NPH cases.

Among our study subjects, acute SDH was a relatively common cause of death. One possible explanation for this is that gait disturbance is common in NPH and this might lead to falls resulting in SDH. Another explanation may be that the CSF shunt can be a risk factor for SDH [42]. It should also be noted that atrophic brains may be more prone to develop SDH. Three of the patients in this study died of postoperative ICH, indicating the 0.2% (2/879) risk of fatal ICH related to the combined procedure of the brain biopsy and the insertion of the intraventricular catheter in the NPH population.

Previous studies have shown that iNPH patients often have cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases [10],[43],[44],[45]. In a recent study by Israelsson and coworkers, it was shown that iNPH patients are more prone to vascular risk factors such as dyslipidemia and obesity [46]. In functional imaging studies, cerebral blood flow has been shown to be reduced in people with iNPH [47],[48]. In our study cohort, cerebrovascular atherosclerosis was a common finding to variable degrees and cardiovascular diseases were the most common cause of death. Cerebral infarcts were seen in all groups, and some of these were multifocal, suggesting that dementia could be attributed to these lesions in some cases, i.e. representing “vascular dementia.”

The etiology and the pathophysiology of iNPH are still poorly understood. The components of the NPH clinical triad are likely to result from subcortical disconnections and disrupted axons. This differs from white matter damage in pediatric hydrocephalus where axonal stretch and local ischemia occur in a simple tissue environment. Secondary changes occur in the neuronal cell bodies and at the synaptic level, but the neurons are viable. The CSF shunting may reverse the dysfunction up to some degree, but the axonal damage cannot be restored [34],[49]. The subependymal gliosis and the fragmented ependymal lining seen in most of the cases in this study to variable extents may be reactive changes to the chronically increased CSF pressure, rather than causative alterations. Similarly, the white matter rarefaction may result from the CSF leakage into the brain tissue and white matter changes are common in vascular pathologies in any case. Another common finding was the meningeal thickening. This can be a secondary alteration to the edema caused by chronic hydrocephalus or the result of mild meningitis in the past, among other possible etiologies. The meningeal tissue assessed here represents only a fraction of the whole meninges and therefore, there is a risk of sampling bias. There has been a recent interest in the role of the disrupted glial-lymphatic, the “glymphatic circulation” in iNPH [50],[51]. Aquaporin 4 (AQP4) may be one of the key molecules involved in the glymphatic system [52]. However, the concept of the CNS glymphatic system is currently evolving and needs to be studied further [53]. A recent study by Eide and Hansson revealed that astrogliosis is common in the cortical iNPH biopsies and that the expression of AQP4 and dystrophin protein 71 is reduced in the astrocytic perivascular endfeet [54]. The expression of the perivascular AQP4 water channel has been shown to be altered in the iNPH patients [55]. Other interesting structures possibly involved in iNPH are the ependymal cilia [56],[57],[58]. However, the number of studies assessing these structures is very limited. The CSF is mostly produced by the choroid plexuses and flows through the arachnoid villi and the granulations into the blood. It has been suggested that the chronic increase in the ICP causes the downregulation of the CSF regulation [59]. In this study, we did not study these structures in detail, but hypothetically the function of these structures could be altered in iNPH patients and therefore should be further studied.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. The cases selected for this study presented with clinically presumed NPH. First of all, we have studied only selected cases (only 29 out of the 565 deceased were available for the neuropathological examination) and therefore, there is a risk of selection bias. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive study of its kind in the literature. The cognitive status of the patients at death was retrospectively assessed based on the clinical records and there is a chance that this could be biased. However, it is unlikely that cases with full-blown dementia were missed. Another strength is the availability of the follow-up data with the cortical biopsies.

In conclusion, in this study we report the neuropathological findings on NPH in a post-mortem series, which is the largest to the best of our knowledge. The neuropathological diagnostic criteria of iNPH are still lacking, and despite the first probable cases reported here, the issue of “hydrocephalic dementia” as an independent entity still requires further confirmation. The neuropathological findings in our cohort of possible NPH patients were highly heterogeneous, which is in line with previous literature. Esiri and Rosenberg have recommended that the principal goal in the neuropathological work-up in hydrocephalic dementia is the exclusion of the defined entities [60]. Here, we described a model for the neuropathological evaluation of the NPH cases. Future studies may eventually reveal that iNPH belongs to the family of “proteinopathies” with the dysfunctional protein yet to be discovered. The use of more extensive sampling (with fresh frozen tissue including meninges) than in the protocol used here and the use of age-matched healthy controls is highly encouraged. Special interest should be directed towards the demented patients with neuropathological findings disproportionate to the clinical presentation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Diagnosing idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Relkin Norman, Marmarou Anthony, Klinge Petra, Bergsneider Marvin, Black Peter McL. Neurosurgery. 2005 Sep 01;57(suppl_3) doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000168185.29659.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bigio Marc R. In: Adult Hydrocephalus. Rigamonti Daniele., editor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014. Neuropathology of human hydrocephalus978-1-139-38281-6 [Google Scholar]

- Lumboperitoneal shunt surgery for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (SINPHONI-2): An open-label randomised trial. Kazui Hiroaki, Miyajima Masakazu, Mori Etsuro, Ishikawa Masatsune. The Lancet Neurology. 2015 Jun;14(6) doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of surgery for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: Role of preoperative static and pulsatile intracranial pressure. Eide Per Kristian, Sorteberg Wilhelm. World Neurosurgery. 2016 Feb;86 doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poor Cognitive outcome in shunt-responsive idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Koivisto Anne M., Alafuzoff Irina, Savolainen Sakari, Sutela Anna, Rummukainen Jaana, Kurki Mitja, Jääskeläinen Juha E., Soininen Hilkka, Rinne Jaakko, Leinonen Ville. Neurosurgery. 2013 Jan;72(1) doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31827414b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High risk of dementia in ventricular enlargement with normal pressure hydrocephalus related symptoms. Koivisto Anne M., Kurki Mitja I., Alafuzoff Irina, Sutela Anna, Rummukainen Jaana, Savolainen Sakari, Vanninen Ritva, Jääskeläinen Juha E., Soininen Hilkka, Leinonen Ville. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2016 May 10;52(2) doi: 10.3233/JAD-150909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of probable idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus in a Norwegian population. Brean Are, Eide Per K. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2008 Jul;118(1) doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Jaraj D., Rabiei K., Marlow T., Jensen C., Skoog I., Wikkelso C. Neurology. 2014 Apr 22;82(16) doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Familial idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Huovinen Joel, Kastinen Sami, Komulainen Simo, Oinas Minna, Avellan Cecilia, Frantzen Janek, Rinne Jaakko, Ronkainen Antti, Kauppinen Mikko, Lönnrot Kimmo, Perola Markus, Pyykkö Okko T., Koivisto Anne M., Remes Anne M., Soininen Hilkka, Hiltunen Mikko, Helisalmi Seppo, Kurki Mitja, Jääskeläinen Juha E., Leinonen Ville. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2016 Sep;368 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post-mortem findings in 10 patients with presumed normal-pressure hydrocephalus and review of the literature: Brain biopsy and autopsy findings in NPH. Leinonen V., Koivisto A. M., Savolainen S., Rummukainen J., Sutela A., Vanninen R., Jääskeläinen J. E., Soininen H., Alafuzoff I. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 2012 Feb;38(1) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Kuopio idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus protocol: initial outcome of 175 patients. Junkkari A., Luikku A. J., Danner N., Jyrkkänen H. K., Rauramaa T., Korhonen V. E., Koivisto A. M., Nerg O., Kojoukhova M., Huttunen T. J., Jääskeläinen J. E., Leinonen V. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS. 2019 Dec;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12987-019-0142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frances A, Pincus H A, First M B. In: Psychiatric diagnosis. 4. Mezzich J E, Kastrup M C, Honda Y, editors. New York, NY: Springer; Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer's dementia and normal aging. Fazekas F, Chawluk Jb, Alavi A, Hurtig Hi, Zimmerman Ra. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1987 Aug;149(2) doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amyloid and tau proteins in cortical brain biopsy and Alzheimer's disease. Leinonen Ville, Koivisto Anne M., Savolainen Sakari, Rummukainen Jaana, Tamminen Juuso N., Tillgren Tomi, Vainikka Sannakaisa, Pyykkö Okko T., Mölsä Juhani, Fraunberg Mikael, Pirttilä Tuula, Jääskeläinen Juha E., Soininen Hilkka, Rinne Jaakko, Alafuzoff Irina. Annals of Neurology. 2010 Oct;68(4) doi: 10.1002/ana.22100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of the apolipoprotein e genotype on cognitive change during a multidomain lifestyle intervention: A Subgroup analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Solomon Alina, Turunen Heidi, Ngandu Tiia, Peltonen Markku, Levälahti Esko, Helisalmi Seppo, Antikainen Riitta, Bäckman Lars, Hänninen Tuomo, Jula Antti, Laatikainen Tiina, Lehtisalo Jenni, Lindström Jaana, Paajanen Teemu, Pajala Satu, Stigsdotter-Neely Anna, Strandberg Timo, Tuomilehto Jaakko, Soininen Hilkka, Kivipelto Miia. JAMA Neurology. 2018 Apr 01;75(4) doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The need to unify neuropathological assessments of vascular alterations in the ageing brain. Alafuzoff Irina, Gelpi Ellen, Al-Sarraj Safa, Arzberger Thomas, Attems Johannes, Bodi Istvan, Bogdanovic Nenad, Budka Herbert, Bugiani Orso, Englund Elisabet, Ferrer Isidro, Gentleman Stephen, Giaccone Giorgio, Graeber Manuel B., Hortobagyi Tibor, Höftberger Romana, Ironside James W., Jellinger Kurt, Kavantzas Nikolaos, King Andrew, Korkolopoulou Penelope, Kovács Gábor G., Meyronet David, Monoranu Camelia, Parchi Piero, Patsouris Efstratios, Roggendorf Wolfgang, Rozemuller Annemieke, Seilhean Danielle, Streichenberger Nathalie, Thal Dietmar R., Wharton Stephen B., Kretzschmar Hans. Experimental Gerontology. 2012 Nov;47(11) doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staging of neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer's disease: A study of the BrainNet Europe Consortium. Alafuzoff Irina, Arzberger Thomas, Al-Sarraj Safa, Bodi Istvan, Bogdanovic Nenad, Braak Heiko, Bugiani Orso, Del-Tredici Kelly, Ferrer Isidro, Gelpi Ellen, Giaccone Giorgio, Graeber Manuel B., Ince Paul, Kamphorst Wouter, King Andrew, Korkolopoulou Penelope, Kovács Gábor G., Larionov Sergey, Meyronet David, Monoranu Camelia, Parchi Piero, Patsouris Efstratios, Roggendorf Wolfgang, Seilhean Danielle, Tagliavini Fabrizio, Stadelmann Christine, Streichenberger Nathalie, Thal Dietmar R., Wharton Stephen B, Kretzschmar Hans. Brain Pathology. 2008 Mar 27;0(0) doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inter-laboratory comparison of neuropathological assessments of β-amyloid protein: A study of the BrainNet Europe consortium. Alafuzoff Irina, Pikkarainen Maria, Arzberger Thomas, Thal Dietmar R., Al-Sarraj Safa, Bell Jeanne, Bodi Istvan, Budka Herbert, Capetillo-Zarate Estibaliz, Ferrer Isidro, Gelpi Ellen, Gentleman Stephen, Giaccone Giorgio, Kavantzas Nikolaos, King Andrew, Korkolopoulou Penelope, Kovács Gábor G., Meyronet David, Monoranu Camelia, Parchi Piero, Patsouris Efstratios, Roggendorf Wolfgang, Stadelmann Christine, Streichenberger Nathalie, Tagliavini Fabricio, Kretzschmar Hans. Acta Neuropathologica. 2008 May;115(5) doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staging/typing of Lewy body related α-synuclein pathology: A study of the BrainNet Europe Consortium. Alafuzoff Irina, Ince Paul G., Arzberger Thomas, Al-Sarraj Safa, Bell Jeanne, Bodi Istvan, Bogdanovic Nenad, Bugiani Orso, Ferrer Isidro, Gelpi Ellen, Gentleman Stephen, Giaccone Giorgio, Ironside James W., Kavantzas Nikolaos, King Andrew, Korkolopoulou Penelope, Kovács Gábor G., Meyronet David, Monoranu Camelia, Parchi Piero, Parkkinen Laura, Patsouris Efstratios, Roggendorf Wolfgang, Rozemuller Annemieke, Stadelmann-Nessler Christine, Streichenberger Nathalie, Thal Dietmar R., Kretzschmar Hans. Acta Neuropathologica. 2009 Jun;117(6) doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0523-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of β-amyloid deposits in human brain: a study of the BrainNet Europe Consortium. Alafuzoff Irina, Thal Dietmar R., Arzberger Thomas, Bogdanovic Nenad, Al-Sarraj Safa, Bodi Istvan, Boluda Susan, Bugiani Orso, Duyckaerts Charles, Gelpi Ellen, Gentleman Stephen, Giaccone Giorgio, Graeber Manuel, Hortobagyi Tibor, Höftberger Romana, Ince Paul, Ironside James W., Kavantzas Nikolaos, King Andrew, Korkolopoulou Penelope, Kovács Gábor G., Meyronet David, Monoranu Camelia, Nilsson Tatjana, Parchi Piero, Patsouris Efstratios, Pikkarainen Maria, Revesz Tamas, Rozemuller Annemieke, Seilhean Danielle, Schulz-Schaeffer Walter, Streichenberger Nathalie, Wharton Stephen B., Kretzschmar Hans. Acta Neuropathologica. 2009 Mar;117(3) doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0485-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staging TDP-43 pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Josephs Keith A., Murray Melissa E., Whitwell Jennifer L., Parisi Joseph E., Petrucelli Leonard, Jack Clifford R., Petersen Ronald C., Dickson Dennis W. Acta Neuropathologica. 2014 Mar;127(3) doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1211-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phases of Aβ-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Thal Dietmar R., Rüb Udo, Orantes Mario, Braak Heiko. Neurology. 2002 Jun 25;58(12) doi: 10.1212/WNL.58.12.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: A practical approach. Montine Thomas J., Phelps Creighton H., Beach Thomas G., Bigio Eileen H., Cairns Nigel J., Dickson Dennis W., Duyckaerts Charles, Frosch Matthew P., Masliah Eliezer, Mirra Suzanne S., Nelson Peter T., Schneider Julie A., Thal Dietmar Rudolf, Trojanowski John Q., Vinters Harry V., Hyman Bradley T. Acta Neuropathologica. 2012 Jan;123(1) doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The special clinical problem of symptomatic hydrocephalus with normal cerebrospinal fluid pressure. Hakim Salomón, Adams Raymond D. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1965 Jul;2(4) doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(65)90016-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postshunt cognitive and functional improvement in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Katzen Heather, Ravdin Lisa D., Assuras Stephanie, Heros Roberto, Kaplitt Michael, Schwartz Theodore H., Fink Matthew, Levin Bonnie E., Relkin Norman R. Neurosurgery. 2011 Feb 01;68(2) doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181ff9d01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shunting normal-pressure hydrocephalus: Do the benefits outweigh the risks?: A multicenter study and literature review. Vanneste Jeroen, Augustijn Paul, Dirven Clemens, Tan Wee Fu, Goedhart Zeger D. Neurology. 1992 Jan;42(1) doi: 10.1212/WNL.42.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frequency of Alzheimer's disease pathology at autopsy in patients with clinical normal pressure hydrocephalus. Cabral Danielle, Beach Thomas G., Vedders Linda, Sue Lucia I., Jacobson Sandra, Myers Kent, Sabbagh Marwan N. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2011 Sep;7(5) doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normal pressure hydrocephalus or progressive supranuclear palsy? A clinicopathological case series. Magdalinou Nadia K., Ling Helen, Smith James D. Shand, Schott Jonathan M., Watkins Laurence D., Lees Andrew J. Journal of Neurology. 2013 Apr;260(4) doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6745-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surgical treatment of idiopathic hydrocephalus in elderly patients. Petersen R. C., Mokri B., Laws E. R. Neurology. 1985 Mar 01;35(3) doi: 10.1212/WNL.35.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natural course of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Andrén K., Wikkelso C., Tisell M., Hellstrom P. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2014 Jul 01;85(7) doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health-related quality-of-life outcome in patients with idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus - a 1-year follow-up study. Junkkari A., Häyrinen A., Rauramaa T., Sintonen H., Nerg O., Koivisto A. M., Roine R. P., Viinamäki H., Soininen H., Luikku A., Jääskeläinen J. E., Leinonen V. European Journal of Neurology. 2017 Jan;24(1) doi: 10.1111/ene.13130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippocampal atrophy correlates with severe cognitive impairment in elderly patients with suspected normal pressure hydrocephalus. Golomb Julie D., Leon Mony J., George Analy E., Kluger Alan, Convit Antonio J., Rusinek Henry, de Santi Susan, Litt Abninder, Foo Sun-Hoo, Ferris Steve H. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1994 May 01;57(5) doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.5.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hydrocephalic Parkinsonism: Lessons from normal pressure hydrocephalus mimics. Starr Brian W., Hagen Matthew C., Espay Alberto J. Journal of Clinical Movement Disorders. 2014 Dec;1(1) doi: 10.1186/2054-7072-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuropathological changes in chronic adult hydrocephalus: Cortical biopsies and autopsy findings. Del Bigio Marc R., Cardoso Erico R., Halliday William C. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences / Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques. 1997 May;24(2) doi: 10.1017/S0317167100021442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mixed brain pathologies in dementia: The BrainNet Europe Consortium experience. Kovacs Gabor G., Alafuzoff Irina, Al-Sarraj Safa, Arzberger Thomas, Bogdanovic Nenad, Capellari Sabina, Ferrer Isidro, Gelpi Ellen, Kövari Viktor, Kretzschmar Hans, Nagy Zoltan, Parchi Piero, Seilhean Danielle, Soininen Hilkka, Troakes Claire, Budka Herbert. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2008;26(4) doi: 10.1159/000161560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disproportionately enlarged subarachnoid-space hydrocephalus (DESH) in normal pressure hydrocephalus misinterpreted as atrophy: Autopsy and radiological evidence. McCarty Arthur M., Jones David T., Dickson Dennis W., Graff-Radford Neill R. Neurocase. 2019 Jul 04;25(3-4) doi: 10.1080/13554794.2019.1617319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of schizophrenia in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Vanhala Vasco, Junkkari Antti, Korhonen Ville E., Kurki Mitja I., Hiltunen Mikko, Rauramaa Tuomas, Nerg Ossi, Koivisto Anne M., Remes Anne M., Perälä Jonna, Suvisaari Jaana, Lehto Soili M., Viinamäki Heimo, Soininen Hilkka, Jääskeläinen Juha E., Leinonen Ville. Neurosurgery. 2019 Apr;84(4) doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyy147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Are there progressive brain changes in schizophrenia? A meta-analysis of structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. Olabi Bayanne, Ellison-Wright Ian, McIntosh Andrew M., Wood Stephen J., Bullmore Ed, Lawrie Stephen M. Biological Psychiatry. 2011 Jul;70(1) doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meta-analysis of brain weight in schizophrenia. Harrison Paul J., Freemantle Nick, Geddes John R. Schizophrenia Research. 2003 Nov;64(1) doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippocampal volume is reduced in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder but not in psychotic bipolar I disorder demonstrated by both manual tracing and automated parcellation (FreeSurfer) Arnold Sara J. M., Ivleva Elena I., Gopal Tejas A., Reddy Anil P., Jeon-Slaughter Haekyung, Sacco Carolyn B., Francis Alan N., Tandon Neeraj, Bidesi Anup S., Witte Bradley, Poudyal Gaurav, Pearlson Godfrey D., Sweeney John A., Clementz Brett A., Keshavan Matcheri S., Tamminga Carol A. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2015 Jan 01;41(1) doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The neuropathology of schizophrenia: A selective review of past studies and emerging themes in brain structure and cytoarchitecture. Bakhshi Kirran, Chance Steven A. Neuroscience. 2015 Sep;303 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subdural hematomas in 1846 patients with shunted idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: Treatment and long-term survival. Sundström Nina, Lagebrant Marcus, Eklund Anders, Koskinen Lars-Owe D., Malm Jan. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2018 Sep;129(3) doi: 10.3171/2017.5.JNS17481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vascular risk factors and arteriosclerotic disease in idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus of the elderly. Krauss Joachim K., Regel Jens P., Vach Werner, Droste Dirk W., Borremans Jan J., Mergner Thomas. Stroke. 1996 Jan;27(1) doi: 10.1161/01.STR.27.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus patients compared to a population-based cohort from the HUNT3 survey. Eide Per, Pripp Are. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS. 2014;11(1) doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vascular factors in suspected normal pressure hydrocephalus: A population-based study. Jaraj Daniel, Agerskov Simon, Rabiei Katrin, Marlow Thomas, Jensen Christer, Guo Xinxin, Kern Silke, Wikkelsø Carsten, Skoog Ingmar. Neurology. 2016 Feb 16;86(7) doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vascular risk factors in INPH: A prospective case-control study (the INPH-CRasH study) Israelsson Hanna, Carlberg Bo, Wikkelsö Carsten, Laurell Katarina, Kahlon Babar, Leijon Göran, Eklund Anders, Malm Jan. Neurology. 2017 Feb 07;88(6) doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattern of white matter regional cerebral blood flow and autoregulation in normal pressure hydrocephalus. Momjian Shahan, Owler Brian K., Czosnyka Zofia, Czosnyka Marek, Pena Alonso, Pickard John D. Brain. 2004 May;127(5) doi: 10.1093/brain/awh131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A prospective study of cerebral blood flow and cerebrovascular reactivity to acetazolamide in 162 patients with idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus: Clinical article. Chang Chia-Cheng, Asada Hiroyuki, Mimura Toshiro, Suzuki Shinichi. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2009 Sep;111(3) doi: 10.3171/2008.10.17676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuropathology and structural changes in hydrocephalus. Del Bigio Marc R. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2010;16(1) doi: 10.1002/ddrr.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glymphatic MRI in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Ringstad Geir, Vatnehol Svein Are Sirirud, Eide Per Kristian. Brain. 2017 Oct 01;140(10) doi: 10.1093/brain/awx191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brain-wide glymphatic enhancement and clearance in humans assessed with MRI. Ringstad Geir, Valnes Lars M., Dale Anders M., Pripp Are H., Vatnehol Svein-Are S., Emblem Kyrre E., Mardal Kent-Andre, Eide Per K. JCI Insight. 2018 Jul 12;3(13) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.121537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The glymphatic pathway in neurological disorders. Rasmussen Martin Kaag, Mestre Humberto, Nedergaard Maiken. The Lancet Neurology. 2018 Nov;17(11) doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30318-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The role of brain barriers in fluid movement in the CNS: is there a ‘glymphatic’ system? Abbott N. Joan, Pizzo Michelle E., Preston Jane E., Janigro Damir, Thorne Robert G. Acta Neuropathologica. 2018 Mar;135(3) doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1812-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrogliosis and impaired aquaporin-4 and dystrophin systems in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Eide P. K., Hansson H.-A. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 2018 Aug;44(5) doi: 10.1111/nan.12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loss of perivascular aquaporin-4 in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Hasan-Olive Md Mahdi, Enger Rune, Hansson Hans-Arne, Nagelhus Erlend A., Eide Per Kristian. Glia. 2019 Jan;67(1) doi: 10.1002/glia.23528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deletions in CWH43 cause idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Yang Hong Wei, Lee Semin, Yang Dejun, Dai Huijun, Zhang Yan, Han Lei, Zhao Sijun, Zhang Shuo, Ma Yan, Johnson Marciana F., Rattray Anna K., Johnson Tatyana A., Wang George, Zheng Shaokuan, Carroll Rona S., Park Peter J., Johnson Mark D. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2021 Mar 05;13(3) doi: 10.15252/emmm.202013249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exploring mechanisms of ventricular enlargement in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: a role of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics and motile cilia. Yamada Shigeki, Ishikawa Masatsune, Nozaki Kazuhiko. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS. 2021 Dec;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12987-021-00243-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonsense mutation in CFAP43 causes normal-pressure hydrocephalus with ciliary abnormalities. Morimoto Yoshiro, Yoshida Shintaro, Kinoshita Akira, Satoh Chisei, Mishima Hiroyuki, Yamaguchi Naohiro, Matsuda Katsuya, Sakaguchi Miako, Tanaka Takeshi, Komohara Yoshihiro, Imamura Akira, Ozawa Hiroki, Nakashima Masahiro, Kurotaki Naohiro, Kishino Tatsuya, Yoshiura Koh-ichiro, Ono Shinji. Neurology. 2019 May 14;92(20) doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downregulation of cerebrospinal fluid production in patients with chronic hydrocephalus. Silverberg Gerald D., Huhn Stephen, Jaffe Richard A., Chang Steven D., Saul Thomas, Heit Gary, Von Essen Ann, Rubenstein Edward. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2002 Dec;97(6) doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.6.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esiri Margaret M., Rosenberg Gary A. In: The Neuropathology of Dementia. 2. Esiri Margaret M., Lee Virginia M.-Y., Trojanowski John Q., editors. Cambridge University Press; Jul 22, 2004. Hydrocephalus and dementia978-0-521-81915-2 [Google Scholar]