Abstract

Objective:

To compare the safety profiles of low- and high-dose tramadol, short-acting hydrocodone and short-acting oxycodone therapies among chronic non-cancer pain individuals.

Methods:

A retrospective cohort study of individuals with back/neck pain/osteoarthritis with an initial opioid prescription for tramadol, hydrocodone or oxycodone was conducted using IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus claims for Academics database (2006–2020). Two cohorts were created for separately studying opioid-related adverse events (overdoses, accidents, self-inflicted injuries and violence-related injuries) and substance use disorders (opioid and non-opioid). Subjects were followed from the index date until an outcome event, end of enrollment or data end. Time-varying exposure groups were constructed and Cox regression models estimated.

Results:

A total of 1,062,167 [tramadol (16.5%), hydrocodone (61.1%), oxycodone (22.4%)] and 986,809 [tramadol (16.5%), hydrocodone (61.3%), oxycodone (22.2%)] individuals were in the adverse event and substance use disorder cohorts. All high-dose groups had elevated risk of nearly all outcomes, compared to low-dose hydrocodone. Compared to low-dose hydrocodone, low-dose oxycodone was associated with a higher risk of opioid overdose (HR: 1.79 (1.37–2.33)). No difference in risk was observed between low-dose tramadol and low-dose hydrocodone (HR: 0.85 (0.64–1.13)). Low-dose oxycodone had higher risks of opioid use disorder, and low-dose tramadol had lower risk of accidents, self-inflicted injuries and opioid use disorder compared to low-dose hydrocodone.

Discussion:

Low-dose oxycodone had higher risk of opioid-related adverse outcomes compared to low-dose tramadol and hydrocodone. This should be interpreted in conjunction with the benefits of pain control and functioning associated with oxycodone use in future research.

Keywords: tramadol, hydrocodone, oxycodone, overdose, opioid use disorder

Introduction

Opioid prescribing for chronic non-cancer pain increased from 13% in 2001 to 23% per chronic pain visit in 2010.1 However, a linear decline in opioid prescribing was observed until 2016, after which the rate of decline in opioid prescribing increased, in part due to publishing of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) opioid prescribing guideline in 2016.2 The recent decrease in opioid prescribing is shaped by fewer initiations of opioid prescriptions.3 Initiation of prescription opioids decreased from 1.6% in 2012 to 0.8% in 2017 among all enrollees of a large commercial health plan.3 With this downward trend, the focus has shifted towards balancing the benefits of pain relief and better functioning with the risk of overdose, opioid use disorder and opioid-driven accidents and injuries.4,5 One key factor in opioid benefit-risk equation could be the type of initial opioid prescribed.

In 2014, hydrocodone (57%) was the most frequently prescribed opioid on the first pain-related visit, followed by tramadol (32%) and oxycodone (10%) based on commercial insurance claims data.6 These three drugs differ in their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties.7 Tramadol has a dual mechanism of action, with opioid agonist activity and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibition property.8 Desmethyltramadol, an active metabolite of tramadol, has strong opioid mu activity, which makes the efficacy and safety of tramadol dependent on cytochrome P450 metabolism.8 Hydrocodone has an agonist activity on opioid mu receptors at the typically prescribed dose, while also having activity on opioid delta and kappa receptors at high doses.9 Oxycodone also primarily activates opioid mu receptors.10 In the US, oxycodone and hydrocodone are schedule II drugs, while tramadol is a schedule IV drug, highlighting the belief that tramadol is considered to confer a lower risk of abuse compared to hydrocodone and oxycodone.11,12

A few self-controlled studies have evaluated the abuse potential of tramadol, hydrocodone and oxycodone.13,14 Healthy adult volunteers with documented opioid abuse have been the subjects of these studies, wherein physiological and self-reported outcomes were reported.13,14 The studies reported similar abuse liability of each of the three opioid analgesics.13,14 However, it has been shown that abuse potential could be dose-dependent, as higher doses of oxycodone induced more abuse-type of symptoms, quantified using physiological measures such as respiratory rates and pupil size, as compared to low dose oxycodone and hydrocodone.13 Additionally, a randomized trial comparing tramadol and hydrocodone on abuse index (defined as dose escalation without physician indication, loss of control, opioid withdrawal or non-medical use) reported that 2.7% and 4.9% of subjects randomized to tramadol and hydrocodone respectively had an abuse score (p<0.01).15 However, in that study, physicians could switch to or add other opioids after the first randomized opioid, which could have biased the comparison, especially if the comparison of interest is tramadol and hydrocodone-only therapy over the duration of follow-up. As a result, clinical studies assessing the safety profile of commonly prescribed opioids based on the number of days on each opioid therapy and the dose prescribed are warranted.

The objective of this study was to compare the risks of opioid-related adverse events (overdoses, accidents, self-inflicted injuries and violence-related injuries) and substance use disorder outcomes (opioid use disorder and non-opioid substance use disorder), among patients initiating tramadol, short-acting hydrocodone and short-acting oxycodone therapies, accounting for the prescribed dose and the number of days in each group.

Materials and Methods

Data

This study used a 10% random sample of the IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus for Academics database (2006–2020), an administrative health insurance claims database containing information on enrollees in commercial, Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care plans in the United States. Given the deidentified nature of the data used, the study was considered not to be human subjects’ research.

Study design and cohort selection

A retrospective cohort study of adults with chronic non-cancer pain (back pain, neck pain or osteoarthritis) who initiated opioid therapy on tramadol, short-acting hydrocodone or short-acting oxycodone with or without being combined with acetaminophen was conducted. First, individuals with an initial opioid prescription for tramadol, short-acting hydrocodone or short-acting oxycodone between July 01, 2006 and May 30, 2020 were identified. Opioid prescriptions were identified using Generic Product Identifier (GPI) codes.16 The type of formulation (short-acting/long-acting) was identified using the dosage form variable. The date of the first opioid prescription was considered the index date. Individuals were required to be continuously enrolled with medical and pharmacy benefits for six months preceding the index date (baseline period). As the target population of the study was patients with chronic back/neck pain or osteoarthritis, subjects were required to have two diagnosis codes for the same condition of back pain, neck pain or osteoarthritis. The first diagnosis was required in the 90 days prior to or on the index date, and the second diagnosis was required within 30–180 days of the first diagnosis in either baseline or follow-up period. These pain conditions were identified in the inpatient or outpatient setting using International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9-CM or ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes (Supplement Table 1). Individuals with missing dates of birth or missing sex were excluded. Also, the study sample was restricted to individuals 18 years or older to focus on the adult population. To limit the analyses to individuals without cancer and certain pain conditions with complex therapeutic needs, individuals with the following conditions or health service utilization in the baseline were excluded: cancer, hospice care, long-term care, rheumatoid arthritis, spinal injuries, pregnancy or organ transplant. Individuals with opioid prescriptions with negative or greater than 180 days’ supply or greater than 1,000 units were excluded from the sample, as these prescriptions are likely to be erroneous. Individuals with more than one opioid drug dispensed on the index date (for example, tramadol plus morphine, hydrocodone plus oxycodone) were excluded.

Two cohorts were then created for separately studying opioid-related adverse events (overdose, accidents, self-inflicted injuries and poisoning, and violence-related injuries) and substance use disorder outcomes (opioid use disorder and non-opioid substances use disorder). To identify incident cases for our outcome measures, individuals with opioid overdose in the baseline were excluded from the adverse events cohort. For the substance use disorder cohort, individuals with substance use disorder in the baseline (opioid or non-opioid) were excluded. This was done to retain individuals with prior substance use disorder diagnoses to study opioid-related adverse events and to retain individuals with prior overdose to study substance use disorder outcomes. Individuals in both cohorts were followed until the first incidence of the outcome, enrollment end date or data end date, whichever was the earliest.

Study measures

Exposure

Low and high dose tramadol, short-acting hydrocodone and short-acting oxycodone were the main exposures of interest. A time-varying approach was used to construct time windows of exposure to thirteen dose and drug based categories. First, seven exposure groups were created based on which opioid was received on each day in the follow-up period: i) tramadol only, ii) short-acting hydrocodone only, iii) short-acting oxycodone only, iv) tramadol combination, v) non-tramadol opioid combination, vi) other opioids, and vii) no opioid. The other opioids group primarily included codeine, fentanyl, morphine, methadone, tapentadol, hydromorphone, oxymorphone and propoxyphene, and long-acting formulations of oxycodone and hydrocodone. Each of the six opioid therapy groups were then divided into low dose and high dose based on the average Morphine Milligrams Equivalent (MME) per day during the respective time windows resulting in thirteen exposure groups. An average daily dose of less than 50 MME was considered low dose and greater than or equal to 50 MME was considered high dose.17 To better attribute transitions from one opioid to another or a different dose to the outcomes, the treatment windows were adjusted using 30% of days’ received of each opioid exposure group for a maximum of 30 days. A previous study used a fixed 14-day period to extend the total days on opioids, based on the finding that around 40% of the adverse events occurred in that period.18 We used percentage of days’ supply for adjusting the treatment period, instead of a fixed number of days, based on the clinical judgment that it better reflects the actual relationship between opioid therapy and the adverse outcomes. In our approach, for example, if a person had low dose short-acting oxycodone prescriptions for 120 days and no opioid treatment for 80 days starting from 121st day, the time was adjusted as followed: 120 + 30 days of low dose short-acting oxycodone (0.3 × 120=36, which is greater than 30, so 30 days is used for adjustment) and 50 days of no opioid treatment.

Outcomes

For the adverse events cohort, the outcomes studied were opioid overdose, accidents, self-inflicted injuries and poisoning, and violence-related injuries. In the primary analysis of overdose, overdose was identified using published ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes (main overdose definition).19 Validation studies of these codes, which used physician charts as the gold standard, reported the sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive values as 25%, 99% and 81% respectively.20,21 Because of the low sensitivity of the overdose diagnosis codes, two additional broader measures of opioid overdose were used in sensitivity analyses. In the first broad measure, procedure codes for naloxone administration in the Emergency Department (ED) and diagnosis codes for opioid-adverse effects in any setting were used, in addition to the overdose diagnosis codes. In the second, and the broadest, overdose measure, diagnosis for respiratory adverse effects (any setting), mechanical ventilation procedures (ED only) or diagnosis for Central Nervous System adverse effects (any setting) for individuals with less than 50 years of age were considered in addition to the first broad measure.

Because misuse of prescription opioids could manifest in events such as accidents, violence-related injuries and self-inflicted injuries, these outcomes were evaluated as well. Accidents and violence-related injuries were identified using ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes obtained from a published study.19 Self-inflicted injuries and poisoning outcomes were identified using a published algorithm, which uses a combination of suicide and poisoning codes in addition to hospitalization information.22

For the substance use disorder cohort, the outcomes were opioid use disorder and other substance use disorders. Opioid use disorder was identified using ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes, based on existing literature.19,23 The other substance use disorder outcome included use disorders of benzodiazepines, amphetamines, marijuana, cocaine, alcohol and other psychoactive drugs.19,23 All diagnosis and procedure codes used for identifying the outcomes are provided in Supplement Table 1.

Covariates

Age and sex have consistently been associated with opioid-related adverse outcomes.24 Substantial geographic variation exists in opioid overdose, opioid use disorder and other substances use disorder.25 As a result, patient age, sex and region of residence were used as covariates. Opioid use disorder is reported to be higher in unemployed and individuals with lower income.26 As a proxy for economic status, payer type variable was used which included coverage by Medicaid. To account for the fact that sicker individuals have higher risk of opioid-related events, Charlson comorbidity index was used.27 Benzodiazepines,28 muscle relaxants,29 hypnotics,30 antidepressants,31 and gabapentinoids32 have been shown to increase the risk of opioid-related adverse outcomes, and were used in the adjusted analyses. Mental health disorders are strongly correlated with substance use disorders and opioid overdose.33 The following mental health disorders were included as covariates: anxiety disorders, personality disorders, mood disorders, major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, nicotine dependence and schizophrenia. (Supplement Table 1). All covariates were gathered from the baseline period.

State-level fatal drug overdose rates were also adjusted for in the models. Fatal drug overdose rates corresponding to the state of residence and for the index year of the individuals in our sample were identified using CDC Wonder database.34,35

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the findings to change in exposure definition and statistical approach. In the first sensitivity analysis, time-varying exposure groups were constructed using the actual days in each exposure group without extending the exposure windows (the 30% approach) as performed in the main analysis. Second, an intent-to-treat type of analysis was conducted using the type of initial opioid as the exposure group (three groups: tramadol only, short-acting hydrocodone only and short-acting oxycodone only), regardless of dose. The individuals were followed until run-out date of any opioid prescription + 180 days, incidence of outcome, loss of enrollment or end of data, whichever was the earliest. The 180-day additional follow-up window was selected, as previous studies have shown that patients are at elevated risk for opioid-related adverse events after opioid discontinuation.36,37 A study by Oliva et al. showed that the risk of overdose decreased monotonically until 180 days following opioid discontinuation and remained stable in the subsequent period.37 Third, the intent-to-treat analysis was conducted using propensity score adjustment. All previously described covariates were used to construct the propensity score for receiving hydrocodone using multinomial logistic regression, and this propensity score was used as the only covariate in the final analysis for the comparison across the three groups. Fourth, a falsification test was conducted to assess the presence and extent of unmeasured confounding. An outcome of dermatitis was used as a falsification outcome because of its implausible association with the use of individual opioid drugs.

Statistical analyses

Time-varying Cox regression models were estimated using the previously described treatment windows as the main variables of interest. Separate analyses were conducted for each outcome using the respective cohorts. Both unadjusted and fully adjusted multivariable analyses were performed, with the multivariable models adjusting for demographics, medication use, pain conditions and mental health conditions previously described. To fully portray the risks of the opioid exposure groups, separate Cox regressions were performed using two reference groups: no opioid and low dose short-acting hydrocodone only. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported. All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.4.

Results

A total of 3,972,126 individuals had an initial opioid prescription for tramadol, short-acting hydrocodone or short-acting oxycodone with no opioid prescriptions in the six months prior. After applying the common inclusion and exclusion criteria for both cohorts, 1,063,887 individuals remained in the overall sample (Table 1). With the requirement of no opioid overdose in the baseline period, 1,062,167 individuals were included in the adverse events cohort. A total of 986,809 individuals were included in the substance use disorder cohort. Approximately 61% initiated opioid use on short-acting hydrocodone, 22% on short-acting oxycodone and 17% on tramadol in both cohorts.

Table 1:

Flow diagram for sample selection for the two cohorts

| Individuals with initial opioid prescription for short-acting hydrocodone, short-acting oxycodone or tramadol | 5,328,474 |

| Individuals with 6 months of enrollment prior to the initial opioid prescription (index date) | 3,972,126 |

| Individuals with back pain, neck pain or osteoarthritis in 90 days prior to and including index date | 1,490,094 |

| Individuals with second diagnosis for the same condition of back pain, neck pain or osteoarthritis within 30–180 days of first diagnosis | 1,430,703 |

| Individuals with age at index date greater than or equal to 18 years | 1,276,074 |

| Individuals with non-missing sex | 1,275,984 |

| Individuals without cancer in the 6 months pre period (baseline) | 1,218,843 |

| Individuals without hospice claims in baseline | 1,218,632 |

| Individuals without long-term care claims in baseline | 1,218,152 |

| Individuals without rheumatoid arthritis in baseline | 1,198,356 |

| Individuals without paraplegia/quadriplegia in baseline | 1,193,799 |

| Individuals without pregnancy in baseline | 1,168,293 |

| Individuals without organ transplant in baseline | 1,165,859 |

| Individuals without potentially erroneous opioid prescriptions in the entire follow-up (negative or greater than 180 days’ supply; negative or greater than 1000 quantities) | 1,078,020 |

| Individuals with only tramadol, short-acting hydrocodone or short-acting oxycodone on the index date | 1,063,887 |

| Opioid-related adverse events cohort | |

| Individuals without opioid overdose (the broadest definition) in the baseline | 1,062,167 |

| Initiated on short-acting hydrocodone | 648,902 (61.1%) |

| Initiated on short-acting oxycodone | 237,762 (22.4%) |

| Initiated on Tramadol | 175,503 (16.5%) |

| Substance use disorder cohort | |

| Individuals without opioid use disorder in the baseline | 1,058,842 |

| Individuals without other substance use disorder in the baseline | 986,809 |

| Initiated on short-acting hydrocodone | 604,991 (61.3%) |

| Initiated on short-acting oxycodone | 218,624 (22.2%) |

| Initiated on Tramadol | 163,194 (16.5%) |

Approximately 63% of the tramadol initiators in both cohorts were female, while approximately 54% of hydrocodone and oxycodone initiators were female (Table 2). More than 70% had chronic osteoarthritis in all three initiator groups while back pain was observed more frequently in tramadol initiators (around 48%) compared to hydrocodone (40%) and oxycodone (36%) initiators. Around 28% of tramadol initiators in either cohort had skeletal muscle relaxant prescriptions, while 21% and 16% of hydrocodone and oxycodone initiators used had skeletal muscle relaxants in the baseline. The total opioid prescriptions and the type of formulations of tramadol, short-acting hydrocodone and short-acting oxycodone are reported in Supplement Table 2.

Table 2:

Baseline characteristics of the opioid-related adverse events (n=1,062,167) and substance use disorder cohorts (n=986,809)

| Cohort for assessing opioid-related adverse events | Cohort for assessing substance use disorder outcomes | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tramadol (n=175,503) | Hydrocodone (n=648,902) | Oxycodone (n=237,762) | Tramadol (n=163,194) | Hydrocodone (n=604,991) | Oxycodone (n=218,624) | |||||||

| Characteristics | n | percent | n | percent | n | percent | n | percent | n | percent | n | percent |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| Mean (sd) | 49.44 (14.2) | 47.42 (14.2) | 48.18 (14.1) | 49.71 (14.2) | 47.59 (14.3) | 48.35 (14.2) | ||||||

| 18–30 years | 21,203 | 12.1 | 97,582 | 15.0 | 32,887 | 13.8 | 19,146 | 11.7 | 89,654 | 14.8 | 29,943 | 13.7 |

| 31–44 years | 39,851 | 22.7 | 158,829 | 24.5 | 55,865 | 23.5 | 36,556 | 22.4 | 146,482 | 24.2 | 50,756 | 23.2 |

| 45–54 years | 44,055 | 25.1 | 165,661 | 25.5 | 60,837 | 25.6 | 40,752 | 25.0 | 153,888 | 25.4 | 55,493 | 25.4 |

| 55–64 years | 45,899 | 26.2 | 157,201 | 24.2 | 61,075 | 25.7 | 43,182 | 26.5 | 148,239 | 24.5 | 56,730 | 26.0 |

| 65 years and above | 24,495 | 14.0 | 69,629 | 10.7 | 27,098 | 11.4 | 23,558 | 14.4 | 66,728 | 11.0 | 25,702 | 11.8 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 110,055 | 62.7 | 351,499 | 54.2 | 123,625 | 52.0 | 103,325 | 63.3 | 330,187 | 54.6 | 114,953 | 52.6 |

| Male | 65,448 | 37.3 | 297,403 | 45.8 | 114,137 | 48.0 | 59,869 | 36.7 | 274,804 | 45.4 | 103,671 | 47.4 |

| Region of residence | ||||||||||||

| East | 33,654 | 19.2 | 104,791 | 16.2 | 72,872 | 30.7 | 31,465 | 19.3 | 98,027 | 16.2 | 67,981 | 31.1 |

| Mid-west | 51,847 | 29.5 | 195,299 | 30.1 | 62,777 | 26.4 | 47,365 | 29.0 | 178,889 | 29.6 | 56,171 | 25.7 |

| South | 54,611 | 31.1 | 165,737 | 25.5 | 53,226 | 22.4 | 51,474 | 31.5 | 155,932 | 25.8 | 49,448 | 22.6 |

| West | 30,055 | 17.1 | 161,052 | 24.8 | 46,696 | 19.6 | 28,066 | 17.2 | 152,158 | 25.2 | 43,036 | 19.7 |

| Missing | 5,336 | 3.0 | 22,023 | 3.4 | 2,191 | 0.9 | 4,824 | 3.0 | 19,985 | 3.3 | 1,988 | 0.9 |

| Insurance type | ||||||||||||

| Commercial only | 125,703 | 71.6 | 513,566 | 79.1 | 188,134 | 79.1 | 119,121 | 73.0 | 484,875 | 80.2 | 175,346 | 80.2 |

| Medicaid only | 19,679 | 11.2 | 44,931 | 6.9 | 13,960 | 5.9 | 15,624 | 9.6 | 34,929 | 5.8 | 9,966 | 4.6 |

| Medicare only | 15,307 | 8.7 | 40,101 | 6.2 | 15,855 | 6.7 | 14,299 | 8.8 | 37,220 | 6.2 | 14,534 | 6.7 |

| Others/Missing | 1,609 | 0.9 | 6,157 | 1.0 | 2,423 | 1.0 | 1,486 | 0.9 | 5,725 | 1.0 | 2,239 | 1.0 |

| Self-Insured only | 13,205 | 7.5 | 44,147 | 6.8 | 17,390 | 7.3 | 12,664 | 7.8 | 42,242 | 7.0 | 16,539 | 7.6 |

| Index year | ||||||||||||

| 2006 | 6,476 | 3.7 | 37,834 | 5.8 | 11,715 | 4.9 | 6,251 | 3.8 | 36,057 | 6.0 | 11,132 | 5.1 |

| 2007 | 15,032 | 8.6 | 84,129 | 13.0 | 26,527 | 11.2 | 14,345 | 8.8 | 79,872 | 13.2 | 24,930 | 11.4 |

| 2008 | 15,706 | 9.0 | 83,448 | 12.9 | 27,226 | 11.5 | 14,910 | 9.1 | 79,070 | 13.1 | 25,469 | 11.7 |

| 2009 | 14,560 | 8.3 | 73,779 | 11.4 | 25,515 | 10.7 | 13,832 | 8.5 | 69,756 | 11.5 | 23,946 | 11.0 |

| 2010 | 13,147 | 7.5 | 63,459 | 9.8 | 20,878 | 8.8 | 12,474 | 7.6 | 60,064 | 9.9 | 19,508 | 8.9 |

| 2011 | 17,043 | 9.7 | 64,517 | 9.9 | 21,872 | 9.2 | 16,030 | 9.8 | 60,481 | 10.0 | 20,215 | 9.3 |

| 2012 | 16,883 | 9.6 | 55,385 | 8.5 | 20,372 | 8.6 | 15,710 | 9.6 | 51,506 | 8.5 | 18,601 | 8.5 |

| 2013 | 14,638 | 8.3 | 44,842 | 6.9 | 17,920 | 7.5 | 13,278 | 8.1 | 40,698 | 6.7 | 16,091 | 7.4 |

| 2014 | 14,951 | 8.5 | 41,848 | 6. 5 | 17,107 | 7.2 | 13,513 | 8.3 | 37,631 | 6.2 | 15,175 | 6.9 |

| 2015 | 17,701 | 10.1 | 42,058 | 6.5 | 18,570 | 7.8 | 15,543 | 9.5 | 36,450 | 6.0 | 15,880 | 7.3 |

| 2016 | 13,315 | 7.6 | 26,949 | 4.2 | 12,254 | 5.2 | 12,317 | 7.6 | 24,834 | 4.1 | 11,221 | 5.1 |

| 2017 | 7,591 | 4.3 | 15,116 | 2.3 | 8,269 | 3.5 | 7,039 | 4.3 | 14,000 | 2.3 | 7,615 | 3.5 |

| 2018 | 3,981 | 2.3 | 7,566 | 1.2 | 4,702 | 2.0 | 3,751 | 2.3 | 7,116 | 1.2 | 4,367 | 2.0 |

| 2019 | 3,362 | 1.9 | 5,965 | 0.9 | 3,680 | 1.6 | 3,143 | 1.9 | 5,587 | 0.9 | 3,411 | 1. 6 |

| 2020 | 1,117 | 0.6 | 2,007 | 0.3 | 1,155 | 0.5 | 1,058 | 0.7 | 1,869 | 0.3 | 1,063 | 0.5 |

| Pain type | ||||||||||||

| Chronic back pain | 83,896 | 47.8 | 261,191 | 40.3 | 86,418 | 36.4 | 77,782 | 47.7 | 242,730 | 40.1 | 78,610 | 36.0 |

| Chronic neck pain | 31,316 | 17.8 | 104,553 | 16.1 | 36,273 | 15.3 | 29,094 | 17.8 | 96,964 | 16.0 | 32,898 | 15.1 |

| Chronic osteoarthritis | 123,002 | 70.1 | 483,379 | 74.5 | 187,565 | 78.9 | 114,582 | 70.2 | 451,760 | 74. 7 | 173,105 | 79.2 |

| Neuropathic pain | 11,135 | 6.3 | 30,460 | 4.7 | 12,697 | 5.3 | 10,297 | 6.3 | 27,967 | 4.6 | 11,448 | 5.2 |

| Migraine | 9,021 | 5.1 | 24,634 | 3.8 | 9,973 | 4.2 | 8,174 | 5.0 | 22,314 | 3.7 | 8,977 | 4.1 |

| Abdominal pain | 24,507 | 14.0 | 88,467 | 13.6 | 40,327 | 17.0 | 21,916 | 13.4 | 79,472 | 13.1 | 35,888 | 16.4 |

| Chest pain | 18,393 | 10.5 | 61,188 | 9.4 | 26,020 | 11.0 | 15,915 | 9.8 | 53,109 | 8.8 | 22,345 | 10.2 |

| Other pain conditions | 33,555 | 19.1 | 142,546 | 22.0 | 59,955 | 25.2 | 30,734 | 18.8 | 131,749 | 21.8 | 54,976 | 25.2 |

| Mental Health Disorders | ||||||||||||

| Major depressive disorder | 7,748 | 4.4 | 23,318 | 3.6 | 9,640 | 4.1 | 6,482 | 4.0 | 19,744 | 3.3 | 7,992 | 3.7 |

| Anxiety disorders | 16,968 | 9.7 | 53,675 | 8.3 | 21,511 | 9.1 | 14,193 | 8.7 | 45,494 | 7.5 | 17,782 | 8.1 |

| Mood disorders | 3,568 | 2.0 | 10,188 | 1.6 | 3,817 | 1.6 | 2,557 | 1.6 | 7,552 | 1.3 | 2,715 | 1.2 |

| Personality disorders | 677 | 0.4 | 1,707 | 0.3 | 835 | 0.4 | 491 | 0.3 | 1,220 | 0.2 | 604 | 0.3 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 1,204 | 0.7 | 3,229 | 0.5 | 1,472 | 0.6 | 867 | 0.5 | 2,414 | 0.4 | 1,099 | 0.5 |

| Nicotine dependence | 12,363 | 7.0 | 45,722 | 7.1 | 21,375 | 9.0 | 2,514 | 1.5 | 9,173 | 1.5 | 6,136 | 2.8 |

| Schizophrenia | 620 | 0.4 | 1,309 | 0.2 | 444 | 0.2 | 360 | 0.2 | 793 | 0.1 | 238 | 0.1 |

| Any surgery | 103,869 | 59.2 | 422,835 | 65.2 | 183,373 | 77.1 | 96,172 | 58.9 | 392,826 | 64.9 | 168,180 | 76.9 |

| Obesity | 17,248 | 9.8 | 46,560 | 7.2 | 22,183 | 9.3 | 15,651 | 9.6 | 42,081 | 7.0 | 19,939 | 9.1 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||||||||||

| Mean (sd) | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.4 (1.0) | ||||||

| 0 | 125,474 | 71.5 | 498,212 | 76.8 | 175,200 | 73.6 | 118,213 | 72.4 | 469,729 | 77.6 | 163,408 | 74.7 |

| 1 | 33,187 | 18.9 | 106,589 | 16.4 | 42,111 | 17.7 | 30,132 | 18.5 | 96,629 | 16.0 | 37,711 | 17.3 |

| 2 | 7,883 | 4.5 | 21,737 | 3.4 | 9,641 | 4.1 | 6,980 | 4.3 | 18,999 | 3.1 | 8,278 | 3.8 |

| 3 or more | 8,959 | 5.1 | 22,364 | 3.5 | 10,810 | 4.6 | 7,869 | 4.8 | 19,634 | 3.3 | 9,227 | 4.2 |

| Baseline drug use | ||||||||||||

| Benzodiazepines | 20,473 | 11.7 | 77,542 | 12.0 | 31,545 | 13.3 | 18,346 | 11.2 | 70,009 | 11.6 | 28,058 | 12.8 |

| Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics | 9,235 | 5.3 | 32,216 | 5.0 | 12,259 | 5.2 | 8,615 | 5.3 | 30,102 | 5.0 | 11,298 | 5.2 |

| Gabapentinoids | 12,040 | 6.9 | 23,403 | 3.6 | 10,581 | 4.5 | 10,717 | 6.6 | 20,552 | 3.4 | 9,065 | 4.2 |

| Skeletal muscle relaxants | 49,926 | 28.5 | 137,889 | 21.3 | 39,097 | 16.4 | 46,105 | 28.3 | 127,569 | 21.1 | 35,459 | 16.2 |

| Antidepressants | 38,324 | 21.8 | 129,025 | 19.9 | 45,159 | 19.0 | 34,391 | 21.1 | 116,828 | 19.3 | 40,008 | 18.3 |

Table 3 describes the events observed, the person time and the unadjusted event rates expressed in events per 100,000 person years for each adverse event for each of the 13 exposure groups observed over the follow up period. A total of 2.9 million person-years of follow up were available for the opioid adverse cohort and 2.7 million person-years of follow up were available for the substance use disorder cohort. A total of 1,443 and 4,806 individuals had opioid overdose based on the main and the broadest definitions respectively. Accident-related injuries was the most common adverse event, with 103,172 individuals having the outcome and opioid use disorder was detected in 9,135 persons. The average daily MME of the low dose tramadol, short-acting hydrocodone and short-acting oxycodone groups were approximately 19, 25 and 31 MME and were 63, 64 and 77 MME for the high dose groups, respectively (Table 4; Supplement Tables 3–9).

Table 3:

Outcome rates for the time-varying opioid exposure groups

| Exposure group | Events; Person-years (percent of total follow-up time) | Event/100,000 person-years | Events; Person-years (percent of total follow-up time) | Event/100,000 person-years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid overdose (main measure) | Opioid overdose (broad measure 1)* | |||

| No opioids | 829; 2,698,741 (93.6%) | 30.7 | 1,177; 2,697,661 (93.6%) | 43.6 |

| Low dose short-acting hydrocodone only | 160; 78,550 (2.7%) | 203.7 | 210; 78,509 (2.7%) | 267.5 |

| Low dose tramadol only | 69; 44,390 (1.5%) | 155.4 | 108; 44,364 (1.5%) | 243.4 |

| Low dose short-acting oxycodone only | 83; 20,485 (0.7%) | 405.2 | 103; 20,467 (0.7%) | 503.3 |

| Low dose tramadol combination | 11; 2,766 (0.1%) | 397.8 | 18; 2,764 (0.1%) | 651.3 |

| Low dose non-tramadol combination | <5; 1,001 (0.0%) | Not calculated | 5; 1,000 (0.0%) | 500.1 |

| Low dose other opioids | 30; 5,889 (0.2%) | 509.4 | 43; 5,879 (0.2%) | 731.5 |

| High dose short-acting hydrocodone only | 20; 6,052 (0.2%) | 330.5 | 26; 6,049 (0.2%) | 429.8 |

| High dose tramadol only | <5; 292 (0.0%) | Not calculated | <5; 292 (0.0%) | Not calculated |

| High dose short-acting oxycodone only | 62; 11,131 (0.4%) | 557.0 | 90; 11,115 (0.4%) | 809.7 |

| High dose tramadol combination | 18; 2,001 (0.1%) | 899.8 | 26; 1,999 (0.1%) | 1,300.5 |

| High dose non-tramadol combination | 95; 6,857 (0.2%) | 1,385.4 | 114; 6,844 (0.2%) | 1,665.6 |

| High dose other opioids | 62; 6,680 (0.2%) | 928.2 | 75; 6,668 (0.2%) | 1,124.7 |

| TOTAL | 1,443; 2,884,835 | 50.0 | 1,999; 2,883,611 | 69.3 |

| Opioid overdose (broad measure 2)** | Accidents | |||

| No opioids | 3,416; 2,693,019 (93.6%) | 126.9 | 88,265; 2,361,665 (93.5%) | 3,737.4 |

| Low dose short-acting hydrocodone only | 375; 78,306 (2.7%) | 478.9 | 6,207; 69,476 (2.8%) | 8,934.0 |

| Low dose tramadol only | 198; 44,263 (1.5%) | 447.3 | 2,413; 39,812 (1.6%) | 6,060.9 |

| Low dose short-acting oxycodone only | 186; 20,395 (0.7%) | 912.0 | 1,708; 17,733 (0.7%) | 9,631.9 |

| Low dose tramadol combination | 31; 2,752 (0.1%) | 1,126.6 | 322; 2,347 (0.1%) | 13,718.7 |

| Low dose non-tramadol combination | 14; 996 (0.0%) | 1,406.3 | 180; 848 (0.0%) | 21,218.9 |

| Low dose other opioids | 59; 5,848 (0.2%) | 1,008.9 | 451; 4,894 (0.2%) | 9,216.2 |

| High dose short-acting hydrocodone only | 49; 6,037 (0.2%) | 811.7 | 808; 5,281 (0.2%) | 15,299.3 |

| High dose tramadol only | <5; 291 (0.0%) | Not calculated | 33; 268 (0.0%) | 12,327.3 |

| High dose short-acting oxycodone only | 154; 11,059 (0.4%) | 1392.6 | 1,244; 9,560 (0.4%) | 13,012.2 |

| High dose tramadol combination | 37; 1,988 (0.1%) | 1,861.4 | 238; 1,695 (0.1%) | 14,038.3 |

| High dose non-tramadol combination | 166; 6,781 (0.2%) | 2,448.1 | 768; 5,590 (0.2%) | 13,737.9 |

| High dose other opioids | 117; 6,616 (0.2%) | 1,768.5 | 535; 5,629 (0.2%) | 9,504.5 |

| TOTAL | 4,806; 2,878,351 | 167.0 | 103,172; 2,524,798 | 4,086.4 |

| Self-inflicted injuries and poisoning | Violence-related injuries | |||

| No opioids | 2,237; 2,695,997 (93.6%) | 83.0 | 1,837; 2,695,208 (93.5%) | 68.2 |

| Low dose short-acting hydrocodone only | 237; 78,443 (2.7%) | 302.1 | 138; 78,502 (2.7%) | 175.8 |

| Low dose tramadol only | 95; 44,333 (1.5%) | 214.3 | 32; 44,392 (1.5%) | 72.1 |

| Low dose short-acting oxycodone only | 100; 20,441 (0.7%) | 489.2 | 44; 20,473 (0.7%) | 214.9 |

| Low dose tramadol combination | 12; 2,758 (0.1%) | 435.1 | 12; 2,759 (0.1%) | 435.0 |

| Low dose non-tramadol combination | 6; 1,001 (0.0%) | 599.1 | 5; 1,003 (0.0%) | 498.6 |

| Low dose other opioids | 31; 5,866 (0.2%) | 528.5 | 7; 5,902 (0.2%) | 118.6 |

| High dose short-acting hydrocodone only | 21; 6,039 (0.2%) | 347.8 | 12; 6,056 (0.2%) | 198.2 |

| High dose tramadol only | 0; 292 (0.0%) | 0.0 | 0; 292 (0.1%) | 0.0 |

| High dose short-acting oxycodone only | 65; 11,104 (0.4%) | 585.4 | 28; 11,153 (0.4%) | 251.1 |

| High dose tramadol combination | 21; 1,998 (0.1%) | 1,051.1 | <5; 2,010 (0.1%) | Not calculated |

| High dose non-tramadol combination | 81; 6,834 (0.2%) | 1,185.2 | 9; 6,930 (0.2%) | 129.9 |

| High dose other opioids | 52; 6,659 (0.2%) | 780.9 | 9; 6,746 (0.2%) | 133.4 |

| TOTAL | 2,958; 2,881,765 | 102.7 | 2,136; 2,881,426 | 74.1 |

| Opioid use disorder | Non-opioid substance use disorder | |||

| No opioids | 5,618; 2,540,315 (93.9%) | 221.2 | 73,023; 2,363,740 (94.2%) | 3,089.3 |

| Low dose short-acting hydrocodone only | 1,159; 69,648 (2.6%) | 1,664.1 | 6,864; 61,361 (2.5%) | 11,186.2 |

| Low dose tramadol only | 336; 40,710 (1.5%) | 825.3 | 2,503; 37,413 (1.5%) | 6,690.2 |

| Low dose short-acting oxycodone only | 486; 17,657 (0.7%) | 2,752.4 | 1,919; 15,380 (0.6%) | 12,477.3 |

| Low dose tramadol combination | 60; 2,398 (0.1%) | 2,501.7 | 302; 2,060 (0.1%) | 14,658.7 |

| Low dose non-tramadol combination | 35; 835 (0.0%) | 4,191.9 | 163; 688 (0.0%) | 23,698.3 |

| Low dose other opioids | 136; 5,100 (0.2%) | 2,666.9 | 411; 4,429 (0.2%) | 9,280.1 |

| High dose short-acting hydrocodone only | 129; 5,359 (0.2%) | 2,407.1 | 731; 4,727 (0.2%) | 15,463.6 |

| High dose tramadol only | 6; 264 (0.0%) | 2,271.0 | 33; 243 (0.0%) | 13,559.6 |

| High dose short-acting oxycodone only | 442; 9,149 (0.3%) | 4,830.9 | 1,365; 7,861 (0.3%) | 17,363.8 |

| High dose tramadol combination | 85; 1,712 (0.1%) | 4,965.1 | 291; 1,407 (0.1%) | 20,681.1 |

| High dose non-tramadol combination | 406; 5,367 (0.2%) | 7,564.2 | 845; 4,309 (0.2%) | 19,608.6 |

| High dose other opioids | 237; 5,577 (0.2%) | 4,249.5 | 593; 4,813 (0.2%) | 12,320.5 |

| TOTAL | 9,135; 2,704,091 | 337.8 | 89,043; 2,508,740 | 3,549.8 |

Opioid overdose diagnosis codes (main overdose definition) + Naloxone administration in the Emergency Department + Opioid-related adverse effects codes

Opioid overdose diagnosis codes (main overdose definition) + Naloxone administration in the Emergency Department + Opioid-related adverse effects codes + Respiratory depression (inpatient/outpatient/Emergency Department; age 50 years or less) + Central Nervous System depression (inpatient/outpatient/Emergency Department; age 50 years or less)

Table 4:

Summary statistics for average daily Morphine Milligrams Equivalent (MME) for the different dose-based exposure groups for the main overdose measure

| Exposure groups | Mean | Median | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low dose short-acting hydrocodone only | 24.9 | 25.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 50.0 |

| Low dose tramadol only | 18.7 | 16.4 | 8.7 | 0.0 | 50.0 |

| Low dose short-acting oxycodone only | 30.7 | 32.8 | 11.0 | 0.0 | 50.0 |

| Low dose tramadol combination | 29.3 | 30.4 | 12.6 | 0.0 | 50.0 |

| Low dose non-tramadol combination | 31.9 | 33.8 | 12.8 | 0.0 | 50.0 |

| Low dose other opioids | 24.7 | 22.5 | 12.2 | 0.0 | 50.0 |

| High dose short-acting hydrocodone only | 64.3 | 56.3 | 30.9 | 50.0 | 7,500.0 |

| High dose tramadol only | 63.6 | 50.0 | 35.2 | 50.0 | 1,000.0 |

| High dose short-acting oxycodone only | 77.3 | 75.0 | 41.3 | 50.0 | 2,857.1 |

| High dose tramadol combination | 90.4 | 70.0 | 65.6 | 50.0 | 1,930.0 |

| High dose non-tramadol combination | 140.3 | 102.3 | 127.1 | 50.0 | 4,020.0 |

| High dose other opioids | 197.1 | 171.4 | 155.7 | 50.0 | 6,000.0 |

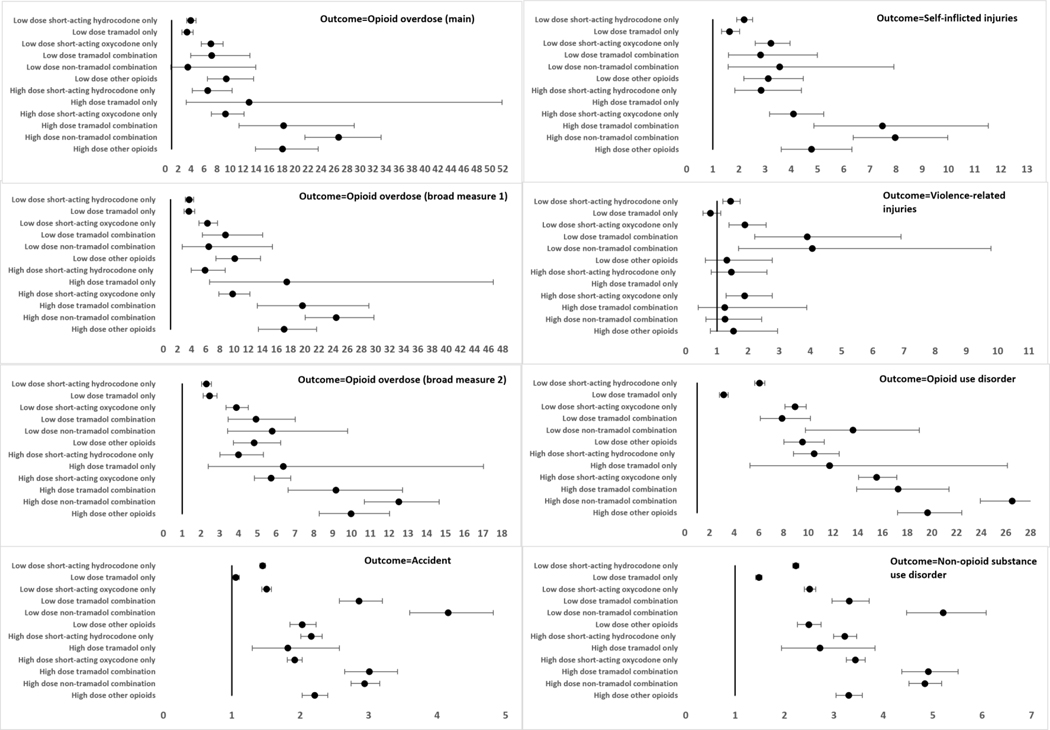

Compared to no opioid therapy, all the opioid therapy groups were associated with increased risks of all study outcomes in the adjusted and unadjusted analyses except for the outcome of violence-related injuries (Figure 1; Supplement Tables 10 and 11). For violence-related injuries, no difference in risk was observed between no opioid therapy and the exposure groups of low dose tramadol only, high dose tramadol combination, high dose non-tramadol combination, low dose other opioids and high dose other opioids. In general, the high dose opioid exposure groups had higher risks of opioid overdose and opioid use disorder than their lower dose exposure counterparts. For example, high dose hydrocodone therapy (compared to no opioid therapy) had a higher risk of opioid use disorder [HR (95% CI): 10.48 (8.79–12.49)] than low dose hydrocodone therapy (compared to no opioid therapy) [HR (95% CI): 6.05 (5.66–6.47)] (Figure 1; Supplement Table 11).

Figure 1: Adjusted* hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for dose-based opioid exposure categories (reference=no opioids).

*The models were adjusted for age, sex, region of residence, insurance type, index year, chronic back pain, chronic neck pain, chronic osteoarthritis, neuropathic pain, migraine, abdominal pain, chest pain, other miscellaneous pain, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, nicotine dependence, Schizophrenia, any surgical procedure, obesity, Charlson comorbidity index, state drug overdose rate (index year), benzodiazepines, non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, gabapentinoids, skeletal muscle relaxants and antidepressants

Opioid overdose (broad measure 1): Opioid overdose diagnosis codes (main overdose definition) + Naloxone administration in the Emergency Department + Opioid-related adverse effects codes

Opioid overdose (broad measure 2): Opioid overdose diagnosis codes (main overdose definition) + Naloxone administration in the Emergency Department + Opioid-related adverse effects codes + Respiratory depression (inpatient/outpatient/Emergency Department; age 50 years or less) + Central Nervous System depression (inpatient/outpatient/Emergency Department; age 50 years or less)

There were zero events in the high dose tramadol group for self-inflicted injuries and violence-related injuries, so the regression coefficients were not estimated

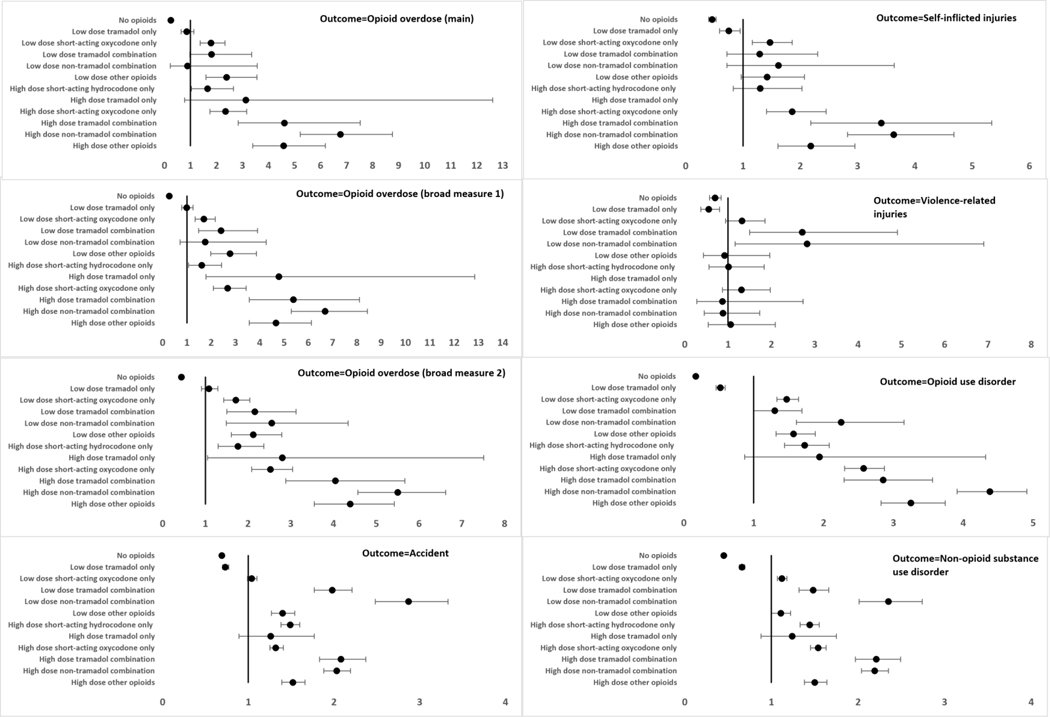

In the adjusted analyses comparing the exposure groups to low dose hydrocodone only therapy, low dose short-acting oxycodone only had a higher risk of opioid overdose [main overdose measure: HR (95% CI): 1.79 (1.37–2.33)], self-inflicted injuries [HR (95% CI): 1.47 (1.16–1.86)], opioid use disorder [HR (95% CI): 1.47 (1.33–1.64] and non-opioid substance use disorder [HR (95% CI): 1.13 (1.07–1.19)] (Figure 2; Supplement Table 11). Low dose tramadol only was not associated with opioid overdose [main overdose measure: HR (95% CI): 0.85 (0.64–1.13)] but was associated with a lower risk of accidents [HR (95% CI): 0.73 (0.70–0.77)], self-inflicted injuries [HR (95% CI): 0.75 (0.59–0.95)], and violence related injuries [HR (95% CI): 0.55 (0.37–0.80)], compared to low dose hydrocodone only. In general, the risk of all the outcomes were higher among the high dose groups compared to the low dose groups with the highest risks observed for the high dose groups in which opioids were combined. For example, high dose opioid combinations not involving tramadol, had substantially elevated risk of opioid overdose [main overdose measure: HR (95% CI): 6.76 (5.22–8.76)], self-inflicted injuries [HR (95% CI): 3.63 (2.82–4.68)] and opioid use disorders [HR (95% CI): 4.38 (3.91–4.91)] compared to low dose hydrocodone only.

Figure 2: Adjusted* hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for dose-based exposure categories (reference=low dose short-acting hydrocodone only).

*The models were adjusted for age, sex, region of residence, insurance type, index year, chronic back pain, chronic neck pain, chronic osteoarthritis, neuropathic pain, migraine, abdominal pain, chest pain, other miscellaneous pain, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, nicotine dependence, Schizophrenia, any surgical procedure, obesity, Charlson comorbidity index, state drug overdose rate (index year), benzodiazepines, non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, gabapentinoids, skeletal muscle relaxants and antidepressants

Opioid overdose (broad measure 1): Opioid overdose diagnosis codes (main overdose definition) + Naloxone administration in the Emergency Department + Opioid-related adverse effects codes

Opioid overdose (broad measure 2): Opioid overdose diagnosis codes (main overdose definition) + Naloxone administration in the Emergency Department + Opioid-related adverse effects codes + Respiratory depression (inpatient/outpatient/Emergency Department; age 50 years or less) + Central Nervous System depression (inpatient/outpatient/Emergency Department; age 50 years or less)

There were zero events in the high dose tramadol group for self-inflicted injuries and violence-related injuries, so the regression coefficients were not estimated

Sensitivity Analyses

In the sensitivity analysis using the actual days in each exposure group, low dose oxycodone only therapy had higher risks of opioid overdose [main overdose measure: adjusted HR (95% CI): 1.84 (1.36–2.48)], self-inflicted injuries [adjusted HR (95% CI): 1.46 (1.12–1.89)], opioid use disorder [adjusted HR (95% CI): 1.56 (1.38–1.76)] and non-opioid substance use disorder [adjusted HR (95% CI): 1.14 (1.08–1.21)], compared to low dose hydrocodone only (Supplement Tables 12 and 13). No difference in risk for the three measures of overdose was observed between low dose tramadol only and low dose hydrocodone only groups, whereas the low dose tramadol group had lower risk of the other outcomes. Similar to main analysis, high dose and combination groups had elevated risks of nearly all outcomes, which was more pronounced for the overdose and opioid use disorder outcomes.

In the intent-to-treat analyses, short-acting oxycodone only initiators had a higher risk of opioid overdose and other adverse effects, [main overdose measure: HR (95% CI): 1.62 (1.37–1.91)], accidents [HR (95% CI): 1.08 (1.06–1.10)], self-inflicted injuries [HR (95% CI): 1.42 (1.25–1.61)] and opioid use disorder [HR (95% CI): 1.37 (1.28–1.47)] compared to short-acting hydrocodone only initiators (Supplement Tables 14 and 15). Initiating opioid therapy on tramadol was not associated with opioid overdose [HR (95% CI): 1.08 (0.89–1.31)] but was associated with a lower risk of accidents [HR (95% CI): 0.77 (0.75–0.79)], violence related injuries [HR (95% CI): 0.75 (0.64–0.88)] and opioid use disorder [HR (95% CI): 0.82 (0.76–0.89)] compared to short-acting hydrocodone initiators. Qualitatively similar results were observed with propensity score adjusted analyses. A modest 4% increase in the hazard of the falsification outcome of atopic dermatitis was observed for tramadol only initiators [HR (95% CI): 1.04 (1.01–1.08)], while short-acting oxycodone only initiators had a 6% lower hazard [HR (95% CI): 0.94 (0.92–0.97)], both compared to short-acting hydrocodone only initiators (Supplement Table 15).

Discussion

Compared to exposure windows where opioids were not dispensed, any opioid therapy at any dose was shown to substantially increase the risk of opioid overdose with hazard ratios of approximately 3.4 to 9.4 when opioid doses were less than 50 MME while hazard ratios varied between 6.6 and 26.7 for opioid doses greater than or equal to 50 MME. Similar but less pronounced relationships between dose groups were observed for accidents, self-inflicted injuries, violence-related injuries, opioid use and non-opioid use disorders. The monotonic increase in opioid overdose and opioid-related mortality with increases in dose is well-documented.30,38–40 Opioid doses are often titrated based on a patient’s adequacy of pain relief; however, escalation of opioid dose is correlated with elevated risks of overdose, injuries and opioid use disorder, without any improvement in pain intensity.23,41 Our findings show that the dose effect is observed across different opioid drugs, emphasizing that prescribers should be cognizant of the risk of high dose opioid prescriptions irrespective of the type of prescribed opioid.

Regarding one of the main questions this study sought to address, we found that low dose short-acting oxycodone therapy nearly doubles the risk of opioid overdose (HR=1.79 ; 95%CI =1.37–2.33) compared to low dose short-acting hydrocodone, while the risk of overdose was not significantly different between low dose tramadol and low dose short-acting hydrocodone. Low dose oxycodone was also associated with a higher risk of self-inflicted injuries, while low dose tramadol was associated with modest reductions in the risk of accidents, self-inflicted and violence-related injuries compared to low dose hydrocodone. These data appear to suggest that the type of opioid may influence overdose risk, opioid-related accidents and injuries independent of the opioid dose, such that oxycodone may increase risk whereas tramadol may have equal or lower risk compared to hydrocodone. Similarly, a study conducted in Tennessee Medicaid adolescents reported a 68% higher risk of opioid overdose for short-acting oxycodone therapy compared to short-acting hydrocodone,.42 That study, unlike our findings, showed that tramadol had a 185% higher risk of opioid overdose.42 The study was conducted at the prescription-level, wherein the total days’ supply for each opioid drug were counted without accounting for combination opioid treatment, and the study cohort included both incident and prevalent users, which could partly explain the discrepancy with our findings. Another study conducted using Veterans Affairs data that used time-varying approach to construct exposure groups reported that tramadol and short acting opioid therapy conferred similar opioid overdose risk compared to no opioid (tramadol only HR=1.52; other short acting opioid HR=1.69).43 Another study, conducted among Medicare osteoarthritis patients, reported slightly higher adverse outcomes-related hospitalization with non-tramadol opioid compared to tramadol therapy. Despite constructing low and high dose categories in our study, modest differences in dose might also explain the differences in risk between the low dose opioid therapies as the average daily MME for low dose short-acting oxycodone only was slightly higher (31 MME) than low dose short-acting hydrocodone only (25 MME) which was higher than low dose tramadol only (19 MME).

Similar findings were observed when contrasting the risk of opioid and non-opioid substance use disorders among exclusive therapy of low dose hydrocodone, oxycodone and tramadol. Our data suggest that low dose oxycodone was associated with an increase in the risk of opioid use disorder by approximately 50% and a smaller increase in non-opioid use disorders while low dose tramadol was associated with a lower risk of these substance use disorders, including opioid use disorders, compared to exclusive use of hydrocodone. A study published using National Survey on Drug Use and Health reported that past-year misuse was 4% among tramadol users, compared to 8% for hydrocodone and oxycodone users, which is consistent with our tramadol findings but at odds with the oxycodone findings having the highest risk of substance use disorders based on documented diagnoses.44 Another study comparing self-reported abuse reported similar rates of opioid abuse among tramadol and oxycodone users.45 These studies used cross-sectional approaches and self-reported measures of misuse and abuse, which reported descriptive findings compared to our study which utilized provider diagnosed cases of substance abuse.44,45 In addition, these studies compare tramadol abuse and oxycodone abuse, which is a different question than the risk of opioid abuse when prescribed tramadol or oxycodone. Our study could not evaluate the use of illicit opioids among the individuals on tramadol, hydrocodone or oxycodone therapy. The fact that the risk of non-opioid substance use disorder was also highest among those on low dose oxycodone therapy (compared to low dose hydrocodone and tramadol) suggests that illicit drug use might be more prevalent during oxycodone therapy.

The similar or lower rates of opioid-related adverse outcomes and substance use disorders among individuals on low dose tramadol only therapy, compared to those on low dose short-acting hydrocodone only, should be interpreted in the broader context of tramadol’s unique safety profile. Tramadol therapy has been found to be associated with higher risks of hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations, serotonin syndrome and seizures, cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality, which were risks this study did not consider.46–48 Additionally, individuals initiating opioid therapy on tramadol had a 41% higher risk of long-term opioid use compared to those initiating the therapy on other short-acting opioids.49 Tramadol prescribing has increased monotonically in the recent years with corresponding decreases in hydrocodone and oxycodone prescribing.50,51 Although our findings suggest that tramadol has similar risks of overdose and lower risk of accidents, injuries and substance use disorders compared to hydrocodone, one needs to consider these other risks, and in particular potential increases in all-cause mortality when considering tramadol as an analgesic strategy.

The highest risks of opioid overdoses and opioid use disorders were observed when persons combined opioids leading to high doses or used high dose opioids that did not include one of the three target opioids. In a study conducted using Medicare data on individuals with long-term opioid therapy, combination opioid therapy had a five-fold increase in the odds of opioid overdose compared to short-acting opioids.52 In comparison to no opioid therapy, combination of short-acting and long-acting was associated with a 384% increase in the hazard of overdose, while short-acting only had a 69% higher hazard of the overdose.43 Likewise, the literature is consistent on elevated risks of opioid-related adverse outcomes when prescribing long-acting opioids which accounted for 40% of high dose other opioid category in our study.43,52,53 Our study reported higher risks of opioid-related adverse outcomes for combination of opioids with and without tramadol, although the estimates had higher magnitudes for non-tramadol combination. These findings suggest that more caution is needed when co-prescribing more than one opioid, and strategies such as opioid rotation, which is shown to help with pain control in cancer patients,54 may be evaluated for chronic non-cancer pain.55

This study has several limitations. First, although we constructed exposure groups using a time-varying approach which restricts the attribution of outcome events to the treatment windows, we only adjusted for potential confounders from the baseline period and did not adjust for time-varying confounding. Second, patient characteristics such as family income, race and pain severity, which are correlates of opioid-related adverse outcomes and could also be associated with type of opioid prescribed, and prescriber characteristics (specialty, preferences) were not adjusted for in the analyses. Furthermore, confounding by indication is likely as different opioids may be prescribed with different treatment goals. Third, the study could not account for adverse events that did not lead to a health care encounter. This could have biased the results if, for instance, individuals on low dose tramadol were more likely to have adverse events that did not involve ER visits, outpatient visits or hospitalizations, compared to those on low dose hydrocodone. Fourth, the severity of the outcomes was not considered, including whether the events were fatal or nonfatal, due to the lack of death information in the data. This could be meaningful if there is a differential severity of the outcomes across the exposure groups. Lastly, exclusive use of high dose tramadol is rare. High dose tramadol only accounted for 0.01% of observed person time which resulted in less precise estimates for that exposure group and for self-inflicted and violence related injuries, hazard ratios could not be estimated at all.

In summary, this study found that exclusive use of low dose oxycodone was associated with increased risks of opioid overdose, violence and self-inflicted injuries, and opioid and non-opioid substance use disorders controlling for MME dose compared to low dose short acting hydrocodone among non-cancer patients with chronic back or joint pain. Exclusive use of hydrocodone or oxycodone at doses greater than 50 MME were associated with even higher risks of these opioid related adverse outcomes. Low dose tramadol was associated with lower risks of opioid and non-opioid substance use disorders compared to low dose hydrocodone. The highest risk of nearly all the outcomes examined were found among persons combining opioids that had doses greater than 50 MME. These findings confirm the well-established risks of prescribing higher opioid doses and suggest that tramadol at low doses have lower risk of opioid-related adverse outcomes than low dose oxycodone. This study did not evaluate the analgesic benefits among the three most commonly prescribed opioids and further research is warranted to fully elucidate the risk-benefit profiles of these opioid analgesics. Likewise, the lower risks of low dose tramadol therapy should be considered together with its serotonin-related adverse events.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure:

The data used for this study was supported by the UAMS Translational Research Institute (TRI), NIH grant UL1TR000039. Dr. Martin has received royalties from TrestleTree, LLC for the commercialization of an opioid risk prediction tool which is unrelated to this investigation.

References

- 1.Larochelle MR, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, Wharam JF. Trends in opioid prescribing and co-prescribing of sedative hypnotics for acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain: 2001–2010. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(8):885–892. doi: 10.1002/PDS.3776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohnert ASB, Guy GP, Losby JL. Opioid Prescribing in the United States Before and After the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2016 Opioid Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(6):367–375. doi: 10.7326/M18-1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu W, Chernew ME, Sherry TB, Maestas N. Initial Opioid Prescriptions among U.S. Commercially Insured Patients, 2012–2017. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380(11):1043–1052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1807069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen SP, Hooten WM. Balancing the Risks and Benefits of Opioid Therapy: The Pill and the Pendulum. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(12):2385–2389. doi: 10.1016/J.MAYOCP.2019.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alford DP. Opioid Prescribing for Chronic Pain — Achieving the Right Balance through Education. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374(4):301–303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMP1512932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mundkur ML, Rough K, Huybrechts KF, et al. Patterns of opioid initiation at first visits for pain in United States primary care settings. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(5):495–503. doi: 10.1002/pds.4322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inturrisi CE, Jamison RN. Clinical pharmacology of opioids for pain. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2002;18(4 SUPPL.):S3–S13. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200207001-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grond S, Sablotzki A. Clinical pharmacology of tramadol. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(13):879–923. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443130-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hydrocodone - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. Accessed July 5, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537288/

- 10.Oxycodone - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. Accessed July 5, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482226/

- 11.Drug Scheduling. Accessed January 24, 2020. https://www.dea.gov/drug-scheduling

- 12.Cowles C. Tramadol Becomes Schedule IV Drug. Caring for the Ages. 2014;15(9):5. doi: 10.1016/J.CARAGE.2014.08.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh SL, Nuzzo PA, Lofwall MR, Holtman JR. The relative abuse liability of oral oxycodone, hydrocodone and hydromorphone assessed in prescription opioid abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;98(3):191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babalonis S, Lofwall MR, Nuzzo PA, Siegel AJ, Walsh SL. Abuse liability and reinforcing efficacy of oral tramadol in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;129(1–2):116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams EH, Breiner S, Cicero TJ, et al. A Comparison of the Abuse Liability of Tramadol, NSAIDs, and Hydrocodone in Patients with Chronic Pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(5):465–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.About - Generic Product Identifier | Medi-Span | Wolters Kluwer. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/medi-span/about/gpi

- 17.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recommendations and Reports. 2016;65(1):1–49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1er [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung CP, Callahan ST, Cooper WO, et al. Outpatient Opioid Prescriptions for Children and Opioid-Related Adverse Events. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2). doi: 10.1542/PEDS.2017-2156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(9):940–947. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowe C, Vittinghoff E, Santos GM, Behar E, Turner C, Coffin PO. Performance Measures of Diagnostic Codes for Detecting Opioid Overdose in the Emergency Department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2017;24(4):475–483. doi: 10.1111/acem.13121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green CA, Perrin NA, Janoff SL, Campbell CI, Chilcoat HD, Coplan PM. Assessing the accuracy of opioid overdose and poisoning codes in diagnostic information from electronic health records, claims data, and death records. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(5):509–517. doi: 10.1002/pds.4157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Callahan ST, Fuchs DC, Shelton RC, et al. Identifying Suicidal Behavior among Adolescents Using Administrative Claims Data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(7):769. doi: 10.1002/PDS.3421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes CJ, Krebs EE, Hudson T, Brown J, Li C, Martin BC. Impact of opioid dose escalation on the development of substance use disorders, accidents, self-inflicted injuries, opioid overdoses and alcohol and non-opioid drug-related overdoses: a retrospective cohort study. Addiction. Published online January 15, 2020. doi: 10.1111/add.14940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Hudson T, Harris KM, Sullivan M. Risk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and dependence among veterans using opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2007;129(3):355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dwyer-Lindgren L, Bertozzi-Villa A, Stubbs RW, et al. Trends and patterns of geographic variation in mortality from substance use disorders and intentional injuries among us counties, 1980–2014. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2018;319(10):1013–1023. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Crane E, Lee J, Jones CM. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorders in U.S. Adults: 2015 national survey on drug use and health. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):293–301. doi: 10.7326/M17-0865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun EC, Dixit A, Humphreys K, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Association between concurrent use of prescription opioids and benzodiazepines and overdose: retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2017;356:j760. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Delcher C, Wei YJJ, et al. Risk of Opioid Overdose Associated With Concomitant Use of Opioids and Skeletal Muscle Relaxants: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. Published online 2020. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1807 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Garg RK, Fulton-Kehoe D, Franklin GM. Patterns of Opioid Use and Risk of Opioid Overdose Death Among Medicaid Patients. Med Care. 2017;55(7):661–668. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sung HG, Li J, Nam JH, Won DY, Choi B, Shin JY. Concurrent use of benzodiazepines, antidepressants, and opioid analgesics with zolpidem and risk for suicide: a case–control and case–crossover study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 2019 54:12. 2019;54(12):1535–1544. doi: 10.1007/S00127-019-01713-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gomes T, Juurlink DN, Antoniou T, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, van den Brink W. Gabapentin, opioids, and the risk of opioid-related death: A population-based nested case–control study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(10). doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toblin RL, Paulozzi LJ, Logan JE, Hall AJ, Kaplan JA. Mental illness and psychotropic drug use among prescription drug overdose deaths: A medical examiner chart review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71(4):491–496. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05567blu [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Underlying Cause of Death, 1999–2020 Request Form. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/datarequest/D76

- 35.Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2018 Key Findings Data from the National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.; 2020. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm.

- 36.Mark TL, Parish W. Opioid medication discontinuation and risk of adverse opioid-related health care events. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;103:58–63. doi: 10.1016/J.JSAT.2019.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oliva EM, Bowe T, Manhapra A, et al. Associations between stopping prescriptions for opioids, length of opioid treatment, and overdose or suicide deaths in US veterans: observational evaluation. BMJ. 2020;368. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.M283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85–92. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bohnert ASB, Logan JE, Ganoczy D, Dowell D. A Detailed Exploration Into the Association of Prescribed Opioid Dosage and Overdose Deaths Among Patients With Chronic Pain. Med Care. 2016;54(5):435. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dasgupta N, Funk MJ, Proescholdbell S, Hirsch A, Ribisl KM, Marshall S. Cohort Study of the Impact of High-Dose Opioid Analgesics on Overdose Mortality. Pain Medicine. 2016;17(1):85–98. doi: 10.1111/PME.12907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayes CJ, Krebs EE, Hudson T, Brown J, Li C, Martin BC. Impact of opioid dose escalation on pain intensity: a retrospective cohort study. Pain. 2020;161(5):979. doi: 10.1097/J.PAIN.0000000000001784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung CP, Callahan ST, Cooper WO, et al. Individual short-acting opioids and the risk of opioid-related adverse events in adolescents. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(11):1448–1456. doi: 10.1002/pds.4872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mudumbai SC, Lewis ET, Oliva EM, et al. Overdose Risk Associated with Opioid Use upon Hospital Discharge in Veterans Health Administration Surgical Patients. Pain Medicine. 2019;20(5):1020–1031. doi: 10.1093/PM/PNY150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reines SA, Goldmann B, Harnett M, Lu L. Misuse of Tramadol in the United States: An Analysis of the National Survey of Drug Use and Health 2002–2017. Subst Abuse. 2020;14:1178221820930006. doi: 10.1177/1178221820930006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwanicki JL, Schwarz J, May KP, Black JC, Dart RC. Tramadol non-medical use in Four European countries: A comparative analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217:108367. doi: 10.1016/J.DRUGALCDEP.2020.108367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fournier JP, Azoulay L, Yin H, Montastruc JL, Suissa S. Tramadol use and the risk of hospitalization for hypoglycemia in patients with noncancer pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):186–193. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hassamal S, Miotto K, Dale W, Danovitch I. Tramadol: Understanding the Risk of Serotonin Syndrome and Seizures. American Journal of Medicine. 2018;131(11):1382.e1–1382.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie J, Strauss VY, Martinez-Laguna D, et al. Association of Tramadol vs Codeine Prescription Dispensation With Mortality and Other Adverse Clinical Outcomes. JAMA. 2021;326(15):1504–1515. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2021.15255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thiels CA, Habermann EB, Hooten WM, Jeffery MM. Chronic use of tramadol after acute pain episode: cohort study. BMJ. 2019;365:l1849. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bigal LM, Bibeau K, Dunbar S. Tramadol Prescription over a 4- Year Period in the USA. Current Pain and Headache Reports 2019 23:10. 2019;23(10):1–7. doi: 10.1007/S11916-019-0777-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rui P, Koredana Santo MD, Ashman JJ. Trends in Opioids Prescribed at Discharge from Emergency Departments among Adults : United States, 2006–2017. Vol 135.; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salkar M, Ramachandran S, Bentley JP, et al. Do Formulation and Dose of Long-Term Opioid Therapy Contribute to Risk of Adverse Events among Older Adults? J Gen Intern Med. Published online July 13, 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1007/S11606-021-06792-8/TABLES/3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chua KP, Brummett CM, Conti RM, Bohnert A. Association of Opioid Prescribing Patterns With Prescription Opioid Overdose in Adolescents and Young Adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(2):141–148. doi: 10.1001/JAMAPEDIATRICS.2019.4878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim HJ, Kim YS, Park SH. Opioid rotation versus combination for cancer patients with chronic uncontrolled pain: A randomized study. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/S12904-015-0038-7/FIGURES/1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Slatkin NE. Opioid switching and rotation in primary care: implementation and clinical utility. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(9):2133–2150. doi: 10.1185/03007990903120158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.