Abstract

Background:

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and intermittently scanned CGM (is-CGM) have shown to effectively manage diabetes in the specialty setting, but their efficacy in the primary care setting remains unknown. Does CGM/is-CGM improve glycemic control, decrease rates of hypoglycemia, and improve staff/physician satisfaction in primary care? If so, what subgroups of patients with diabetes are most likely to benefit?

Methods:

A comprehensive search in seven databases was performed in June 2021 for primary studies examining any continuous glucose monitoring system in primary care. We excluded studies with fewer than 20 participants, specialty care only, or hospitalized participants. The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation were used for the quality assessment. The weighted mean difference (WMD) of HbA1c between CGM/is-CGM and usual care with 95% confidence interval was calculated. A narrative synthesis was conducted for change of time in, above, or below range (TIR, TAR, and TBR) hypoglycemic events and staff/patient satisfaction.

Results:

From ten studies and 4006 participants reviewed, CGM was more effective at reducing HbA1c compared with usual care (WMD −0.43%). There is low certainty of evidence that CGM/is-CGM improves TIR, TAR, or TBR over usual care. The CGM can reduce hypoglycemic events and staff/patient satisfaction is high. Patients with intensive insulin therapy may benefit more from CGM/is-CGM.

Conclusions:

Compared with usual care, CGM/is-CGM can reduce HbA1c, but most studies had notable biases, were short duration, unmasked, and were sponsored by industry. Further research needs to confirm the long-term benefits of CGM/is-CGM in primary care.

Keywords: continuous glucose monitor (CGM), flash glucose monitor (FGM), primary care, systematic review, type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus continues to result in considerable morbidity and mortality worldwide, primarily through its strong association with increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality,1,2 but also through vision loss, amputations, chronic kidney disease, and stroke. 3 Although diabetes-related complications have decreased significantly between 1990 and 2010, 4 recent epidemiological studies show that the global prevalence of diabetes mellitus, particularly type 2 diabetes, continues to rise. 5 Numerous studies have shown that optimal glycemic control reduces the risk of morbidity6,7 but has proven to be elusive in a significant portion of the patient population living with diabetes. 8

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and intermittently scanned CGM (is-CGM) are evolving technologies with the potential to add precision to the monitoring and management of diabetes. Both involve the use of subcutaneous sensors that sample interstitial glucose levels, which can be used to alert the patient when the glucose trend is expected to reach hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. In CGM, the device records glucose levels 280 times per day and are worn for ten days. 9 Intermittently scanned CGM (is-CGM), also called flash glucose monitoring (FGM) in some countries, uses similar approaches, but values are measured on demand, up to every minute. There are three different versions of is-CGM systems worldwide (Freestyle Libre, Freestyle Libre Pro, and Freestyle Libre 2).

Recently, both the American Diabetes Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology have issued recommendations supporting the use of CGM/is-CGM for patients using multiple daily insulin injections (MDIs), infusion pumps, and for patients on noninsulin therapies.10,11 The recent increase in use has also resulted in multiple articles in the primary care literature regarding interpretation, 12 integration into clinical workflows,13,14 and reimbursement.15,16 In addition, direct advertising to health care providers and the public has brought further attention to this technology. 17

The CGM and is-CGM use in the specialty care setting is well documented. However, surveys have shown that there is an insufficient number of endocrinologists to care for the large and growing population of patients with diabetes; it is estimated that the US primary care workforce cares for 85% of patients with diabetes. 18 In many countries, people with type 1 diabetes are treated exclusively at the specialist level or in co-management with their primary care physician (PCP). However, most patients have type 2 diabetes, the majority of whom are cared for by primary care, including those managed with insulin. The evidence for widespread use of CGM/is-CGM in patients living with type 2 diabetes is limited 19 and our search showed there are no published systematic reviews for evaluating the use of CGM/is-CGM in the primary care setting. This systematic review aimed to answer the following questions: In primary care, does the use of CGM/is-CGM in patients with diabetes result in improved glycemic control, decreased rates of hypoglycemia, and improved patient and staff satisfaction? If so, what subgroups of primary care patients with diabetes are most likely to benefit?

Methods

This systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines 20 and the checklists are available in Online Appendices A and B.

Sources and Search

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in January 2021 by a medical librarian specialized in systematic reviews (L.Ö.). The search was updated in June 2021. Seven biomedical and health sciences databases, PubMed (NML), MEDLINE (Clarivate), EMBASE (Elsevier), Scopus (Elsevier), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Cochrane Library (Cochrane) and Web of Science (Clarivate), were searched from their inception.

A combination of the search fields “Text Word” (alternatively title, abstract, and keywords) and MeSH/thesaurus terms (when available) was used to locate the best available evidence. The search was performed without any geographical or publication year restrictions. A filter for English language was applied.

Cabell’s Predatory Report (Cabell’s Scholarly Analytics, 2021) 21 was consulted to confirm that none of the finally selected papers were affiliated with potentially predatory publishers or journals. Detailed search reporting of all included sources is available in Online Appendix C.

Study Selection

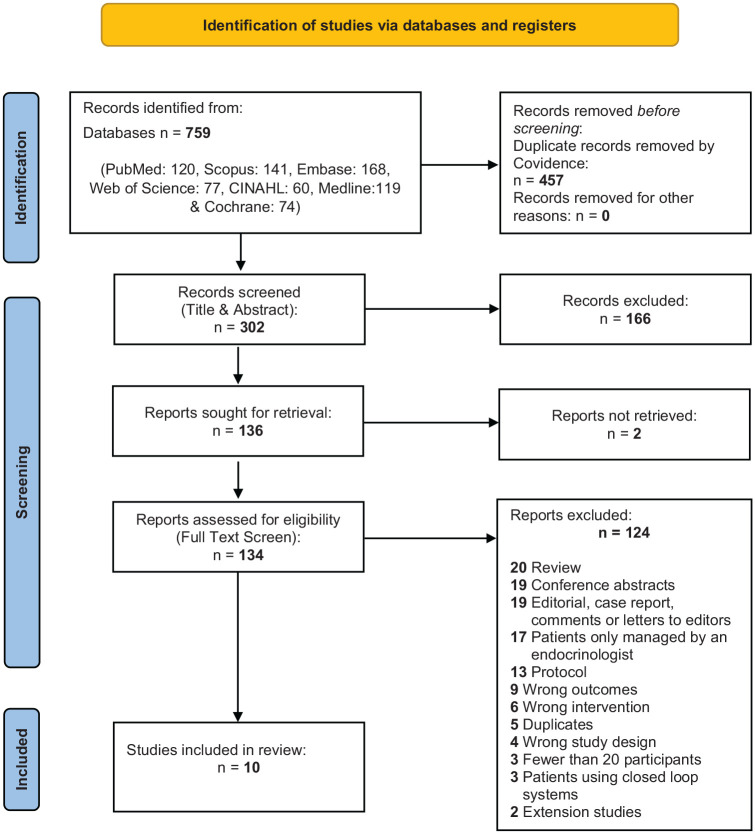

All records identified in the database search were exported to the Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, 2021) 22 for automatic de-duplication, screening, and extraction. Two reviewers independently performed title and abstract (R.D.G. and J.K.) and full-text screening (A.K. and J.K.), including primary studies involving the use of any continuous glucose monitoring system in patients with diabetes (type 1, type 2, and gestational) under the care of a primary care provider, including those co-managed with an endocrinologist. Some studies included patients co-managed by their PCP and an endocrinologist, which reflects the pragmatic study design. In actual practice, PCPs may need consultation with endocrinology. We included these studies to reflect this real-world collaboration to encourage PCPs to consider this practice. Exclusion criteria include gray literature, studies with fewer than 20 participants, participants managed only by an endocrinologist, participants hospitalized or critically ill, and studies where participants used closed-loop systems where the device automatically adjusts the infusion of insulin based on the glucose results. A third reviewer independently resolved any conflicts at each step with the support of the Covidence software. A PRISMA flow diagram of the selection process is available in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram detailing the search, de-duplication, screening, and selection process.

Abbreviation: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Source: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71.

Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers (A.K. and J.K.) used the Covidence software to extract study characteristics and outcomes. The primary outcome assessed was the change in HbA1c from baseline. The secondary outcomes included the change in percentage of time in range (TIR), time above range (TAR), and time below range (TBR); complications, including hypoglycemic events; physician/staff and patient satisfaction; and data on which subgroups benefit most from CGM/is-CGM, if reported. In addition, each study’s funding sources and conflicts of interest were extracted. These outcomes were compared with usual care, which, in most cases, was self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) with HbA1c. A third reviewer (R.D.G.) resolved conflicts.

Quality Assessment

Two independent reviewers (A.K. and J.K.) used the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Quality Assessment Tools 23 and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation 24 to assess the quality and risk of bias of each included study. The Covidence software enabled a systematic and blinded approach. A third reviewer (R.D.G.) resolved conflicts.

Data Synthesis

The study characteristics and outcomes of each study were summarized in a comprehensive table, which allowed us to group and compare similar relevant findings. For studies comparing our primary outcome, change in HbA1c, between CGM/is-CGM and usual care, the mean difference with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was calculated using standard equations from the reported standard deviation (SD), standard error (SE), CI, and/or P values from each study. 25 If variability was reported as interquartile range, SD was estimated. 26 For studies without comparisons with usual care, the mean difference in HbA1c from baseline to study end was calculated. To accommodate the difference in the number of study participants between the studies when calculating the total mean difference in HbA1c, a weighted mean difference (WMD) was calculated. The WMD in HbA1c was calculated by summing the total mean difference in HbA1c among the ten studies and then taking the average of this total, assigning proportional weight based on the number of participants in each study. Meta-analysis was not performed due to the large heterogeneity of study designs, study participants, interventions, and outcome variables between the trials. The remaining findings, including secondary outcomes, patient/staff satisfaction, and which subgroups of persons with diabetes benefiting most from CGM/is-CGM, were analyzed through a narrative synthesis.

Results

As summarized in Figure 1, 1374 records were identified in the literature search. A total of 302 unique references remained after the automatic de-duplication in Covidence. After the title and abstract screening, 136 papers were selected for full-text screening, of which ten studies were identified eligible for the systematic review.

The total number study participants were 4006 among all ten studies. Four studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), one was a nonrandomized controlled trial (NRCT), three were cohort studies, and two were pre/post uncontrolled interventions. All participants were nonpregnant and 18 years or older. One study solely looked at type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), five exclusively evaluated type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and four studies had a mixed population of T1DM and T2DM. Only two studies used is-CGM (FGM) and only two studies had prolonged and sustained CGM/is-CGM use. The characteristics of each study are compiled in Table 1 and the pertinent outcomes of all included studies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Summary of Characteristics of Included Studies.

| CGM (professional, retrospective) | is-CGM (FGM) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled intervention studies | Observational cohort studies | Controlled intervention | Observational cohort | |||||||

| Title | Reduction in HbA1c using professional FGM in insulin-treated type 2 diabetes patients managed in primary and secondary care settings: a pilot, multicentre, RCT | An exploratory trial of basal and prandial insulin initiation and titration for type 2 diabetes in primary care with adjunct retrospective CGM: INITIATION study | Demonstrating the clinical impact of continuous glucose monitoring within an integrated healthcare delivery system | The effects of professional CGM as an adjuvant educational tool for improving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes | Telemedicine-based KADIS combined with CGMS has high potential for improving outpatient diabetes care | Effect of pharmacist-driven professional continuous glucose monitoring in adults with uncontrolled diabetes | Effect of professional CGM (pCGM) on glucose management in type 2 diabetes patients in primary care | Impact of professional continuous glucose monitoring by clinical pharmacists in an ambulatory care setting | Use of professional-mode FGM, at three-month intervals, in adults with type 2 diabetes in general practice (GP-OSMOTIC): a pragmatic, open-label, 12-month, RCT | Impact of flash glucose monitoring on glucose control and hospitalization in type 1 diabetes: a nationwide cohort study |

| Author, year | Ajjan, 2019 | Blackberry, 2014 | Isaacson, 2020 | Rivera-Avila, 2021 | Salzsieder, 2007 | Sherrill, 2020 | Simonson, 2021 | Van Dril, 2019 | Furler, 2020 | Tsur, 2021 |

| Country | England | Australia | USA | Mexico | Germany & UAE | USA | USA | USA | Australia | Israel |

| Journal | Diabetes & Vascular Disease Research | Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice | Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology | BMC Endocrine Disorders | Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology | Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharm | Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology | Journal of the Amer College of Clin Pharm | Lancet Diabetes | Diabetes Metab Research and Reviews |

| Study design & participant number (N) | Pilot, prospective RCT N = 148 |

Exploratory RCT N = 92 |

Parallel multisite RCT N = 99 |

Quasi-experimental NRCT N = 302 |

Pilot, multicenter, open-label, pre-post intervention, N = 34 | Retrospective cohort study N = 253 |

Prospective cohort blinded study N = 68 |

Quasi-experimental retrospective pre/post N = 29 |

Pragmatic open-label RCT N = 299 |

Observational cohort N = 2682 |

| Study duration | Seven months | 24 weeks | Six months | Six months | Two years | 20 months | ~13 months | Four months | 12 months | ~15 months |

| CGM type | CGM (professional) | CGM (retrospective) | CGM | CGM (professional) | CGM (professional) | CGM (professional) | CGM (professional) | CGM (professional) | FGM (professional) | FGM |

| Device | FreeStyle Libre Pro | Medtronic iPro2 | Dexcom G6 | Medtronic iPro2 | Medtronic (not specified) | FreeStyle Libre Pro | FreeStyle Libre Pro | FreeStyle Libre Pro | FreeStyle Libre Pro | Freestyle Libre |

| CGM usage duration | Varied by group | Seven days at baseline, 12, 24 weeks for control; seven days at baseline and before each visit for intervention group | Six months | Seven days baseline and post CGM | Two 72-hour periods of CGM three months apart | 14 days | Up to 14 days (optimally) at baseline and then before three- or six-month follow-up visit | 14 days (minimum 24 hours) | Five to 14 days before GP visit at baseline, three, six, nine, and 12 months | ~ 15 months |

| CGM use | Intermittent | Intermittent | Sustained | Intermittent | Intermittent | Sustained | Intermittent | Sustained | Intermittent | Sustained |

| Diabetes type | Type 2 | Type 2 | Types 1 and 2 | Type 2 | Types 1 and 2 | Types 1 and 2 | Type 2 | Types 1 and 2 | Type 2 | Type 1 |

| Mean age | 63.6 years | 59 years | Median 55-64 years | 59.5 years | 44.6 years | 62.6 years | 61.6 years | 59.6 years | 60.1 years | 46.6 years |

| Baseline A1c | 8.7% | 9.9% | Not given | 9.55% | 8.19% | 9.0% | 8.8% | 9.0% | 8.9% | 8.1% |

| Provider setting | Primary/secondary care | Primary/secondary care | Primary care | Primary care | Primary/secondary care | Primary care | Primary/secondary care | Primary care | Primary care | Primary/secondary care |

| Inclusion criteria of participants | T2DM treated with insulin therapy for at least six months HbA1c 7.5%-12.0% | Insulin naive with T2DM. HbA1c > 7.5% in the last six months. On max tolerated doses of OHA and stable for three months or more. Willing to commence insulin & monitor glucose ≥ twice daily | HbA1c > 6.5%, not currently using a CGM device, not pregnant or planning to become pregnant for the duration of the study, and upon recommendation from their respective PCP | HbA1c > 8%, without diagnosis of memory disorder, informed consent obtained | Insulin-treated type 1 or type 2 diabetes Diabetes duration more than two years Written informed consent |

HbA1c ≥ 7%, proCGM implemented by a pharmacist or physician | T2DM for at least one year, not meeting glycemic goals defined as most recent A1c >7.0% and <11.0%; willing to wear a pCGM device | Professional CGM placed during study dates of July 1, 2017, to October 31, 2017. A1c > 7.0%, insulin therapy | HbA1c in the past month ≥ 0.5% above recommended target despite rx of at least two OHA or insulin (or both), T2DM diagnosed for more than one year, three and more visits to study practice in the past two years & therapy stable for four months | T1DM, enrolled in health system more than six months prior to and after first date of purchase of sensor, with sensor purchases made more than six months ago after the first date of purchase of sensor |

| Exclusion criteria of participants | Use of animal insulin, TDD insulin > 1.75 μ/kg. Insulin pump or CGM use in last six months, steroid therapy, pregnant or planning pregnancy, adhesives allergy, or considered unsuitable to participate by the investigator | T1DM, fasting blood glucose < 6.0 mmol/L, major medical or psychiatric illness, pregnant or planning pregnancy | Unknown | Preceding ketotic acidosis Existing acute hepatic, renal, GI, or inflammatory disease Lactation or pregnancy Lack of willingness or ability to follow written or verbal instructions |

Patients with additional CGM use (whether personal or professional) within the six-month follow-up period | <24 hours of interstitial glucose data Device lost after adhesive failure and patient declined replacement |

Debilitating condition, eGFR < 30, diabetic retinopathy, pregnant, lactating, planning pregnancy, unable to speak English or give informed consent. allergy to adhesive tape. Any condition that renders HbA1c unreliable | If the average sensor purchase was less than one FCGM sensor per month during the follow-up period, consistent with a minimum of 50% adherence | ||

| Study strengths and limitations | Strength: First RCT investigating role of Libre Pro in T2DM in

primary/secondary care settings. Real-world glucose management

used Limitations: Slightly higher dropout rate, nonblinded, strong study effect in control group, choosing TIR as primary endpoint. Exclusion criteria are unclear |

Strengths: First to demonstrate feasibility of rCGM on a

large-scale T2DM population in primary care. Real-world design

and selected population. Strong results within the rCGM

group Limitations: Underpowered to detect difference between rCGM and SMBG groups. |

Strengths: Long duration of CGM usage Limitations: Continuous glucose data not obtained on patients randomized to the usual care FSG, 79% of withdrawals occurred after the participants found out their allocation (potential bias), homogeneous population, unvalidated patient satisfaction questionnaire |

Strengths: Demonstrated CGM could be an adjuvant educational

tool to improve glycemic control Limitations: Selection bias (nonrandomized: more IGr on insulin, higher average baseline HbA1c), treatment selection bias: IGr received more training on daily recordings of meds, diet, foods, physical activity which is confounding |

Limitations: No usual care group, intervention was combination of CGM + decision support via KADIS, unblinded, small number of participants | Strengths: Pharmacist-led interventions can lead to clinical and

economic benefit. Included patients not treated by insulin

(literature lacking for this subgroup) Limitations: Retrospective, no usual care group, confounding interventions, predominant white population |

Strengths: Conducted in a real-world setting, compared two

different models of care (MD vs RN/CDCES) Limitations: Lacked rigor and consistency of follow-up, few P values reported, slightly more than 50% of participants reapplied pCGM |

Strengths: Showed potential for pharmacist-led CGM to reduce

HbA1c Limitations: No control, possible confounding with increased contact with a clinical pharmacist, variability in timing of the pre- and postintervention HbA1c measurements, mostly African American women with T2DM, retrospective study |

Strengths: Largest RCT of the use of professional-mode FGM in

pragmatic, real-world, primary care setting, broad eligibility

criteria, high retention, and longer follow-up (12

months) Limitations: Participants had low levels of diabetes distress at baseline, no independent monitoring of serious adverse events, which were not structurally assessed |

Strengths: Real-world assessment of large cohort with clinically

oriented outcomes; heterogeneous patient

population Limitations: Residual bias or confounders, as patients who were more motivated to improve their diabetes control may have attained the FGM technology, retrospective design, no access to real-time data |

|

1. Study funding sources

2. Possible conflicts of interest for study authors |

1. None declared 2. Honoraria, research support, grants, and personal fees received from Abbott Diabetes Care. Personal fees from Sanofi and CPRD |

1. Sanofi and Medtronic funded and supported; Abbott and BD

supported materials 2. NHMRC and financial relationships with pharmaceutical industries outside submitted work |

1. Intermountain Healthcare Group 2. Authors with relationships with Medtronic, Abbott, among others |

1. Medtronic PLC 2. One of the authors is employee of Medtronic PLC |

1. Grants from the German BMBF and Ministry of Education,

Science & Culture; Medtronic MiniMed and AUST

Network 2. Support from Medtronic MiniMed |

1. No outside funding 2. None reported |

1. Abbott Diabetes Care 2. Author grants from Abbott, Medtronic, and relationships with Dexcom, Medtronic, JDRF, NIH/NIDDK, among others |

1. Unknown 2. None declared |

1. NHMRC Australia, Sanofi Australia, Abbott Diabetes Care

(equipment) 2. Authors with relationships with Medtronic, Abbott, among others |

1. Not reported 2. Grants and personal fees from Medtronic, Abbott, among others |

Abbreviations: CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; is-CGM, intermittently scanned continuous glucose monitoring; rCGM, retrospective continuous glucose monitoring; FGM, flash glucose monitoring; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; RCT, randomized controlled trial; NRCT, nonrandomized controlled trial; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; OHA, oral hypoglycemic agents; PCPs, primary care physicians; TIR, time in range; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose; FSG, finger-stick glucose; CDCES, Certified Diabetes Care and Education Specialist; TDD, total daily insulin dose; GI, gastrointestinal; FCGM, flash continuous glucose monitoring; CGMS, continuous glucose monitoring system.

Table 2.

Summary of Outcomes of Included Studies.

| CGM (professional, real-time, retrospective) | is-CGM (FGM) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled intervention studies | Observational cohort studies | Controlled intervention | Observational cohort | |||||||

| Title | Reduction in HbA1c using professional FGM in insulin-treated type 2 diabetes patients managed in primary and secondary care settings: a pilot, multicentre, RCT | An exploratory trial of basal and prandial insulin initiation and titration for type 2 diabetes in primary care with adjunct retrospective CGM: INITIATION study | Demonstrating the clinical impact of continuous glucose monitoring within an integrated healthcare delivery system | The effects of professional CGM as an adjuvant educational tool for improving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes | Telemedicine-based KADIS combined with CGMS has high potential for improving outpatient diabetes care | Effect of pharmacist-driven professional continuous glucose monitoring in adults with uncontrolled diabetes | Effect of professional CGM (pCGM) on glucose management in type 2 diabetes patients in primary care | Impact of professional continuous glucose monitoring by clinical pharmacists in an ambulatory care setting | Use of professional-mode FGM, at three-month intervals, in adults with type 2 diabetes in general practice (GP-OSMOTIC): a pragmatic, open-label, 12-month, RCT | Impact of flash glucose monitoring on glucose control and hospitalization in type 1 diabetes: a nationwide cohort study |

| Author, year | Ajjan, 2019 | Blackberry, 2014 | Isaacson, 2020 | Rivera-Avila, 2021 | Salzsieder, 2007 | Sherrill, 2020 | Simonson, 2021 | Van Dril, 2019 | Furler, 2020 | Tsur, 2021 |

| CGM type | CGM (professional) | CGM | CGM | CGM | CGM (professional) | CGM (professional) | CGM (professional) | CGM (professional) | FGM | FGM |

| Device | FreeStyle Libre Pro | Medtronic iPro2 | Dexcom G6 | Medtronic iPro2 | Medtronic (not specified) | FreeStyle Libre Pro | FreeStyle Libre Pro | FreeStyle Libre Pro | FreeStyle Libre Pro | Freestyle Libre |

| Change in HbA1c | Group C decreased from 8.6% to 8.2%. No change in control group (SMBG) or between group B and control. Significant end of study difference of group C vs control (-0.48%, P = .0041) at 230 days | Decrease of 2.7% in rCGM group from 9.9 to 7.3 at 24 weeks (P < .0001). SMBG group also had reduction of -2.4%, and not statistically different from rCGM group (P = .31) | CGM group A1c decreased by median of -0.6% vs SMBG group (-0.1%) with P = .001 at six months | Adjusted diff-in-diff estimator showed improved HbA1c 0.609, P = .006; 0.481% (P = .023) when baseline observations carried forward for n = 34 w/o post three-month evaluation | KADIS-based decision support reduced A1c 0.62%, P < .01 | Improved HbA1c (P < .001 for all values): combined pharmacist (cRPh): -1.1%; one pharm visit (RPh1): -1.0%; two pharm visits (RPh2): -1.3%; one MD visit (MD1): -0.6% | Overall decrease from 8.8% to 8.2% (-0.6%; P = .006), MD Care model -1%, RN/CDCES Care model -0.6% | 9% to 8.3%, P = .156 but low because power low | HbA1c decreased -0.7% in FGM group versus -0.4% in usual care SMBG (P = .0001). FGM group lower by -0.5% (P = .0001) at six months but not statistically significant at 12 months (P = .059) | Overall, A1c decreased from 8.1% to 7.9%, P

< .001; sustained for up to 15 months 25.5% of the overall group had an A1c reduction of ≥ 0.5% |

| TIR | No change noted per group and no significant difference between groups | rCGM increased from 26.5% to 71.5% (P < .0001), but no significant difference vs SMBG (P = .63). | Stable over time for CGM from baseline to study end | Improved in IGr from baseline to three months (+7.65%, P = .005), no control | Increased in subgroup who wore pCGM twice, more in MD model (+17.8%) than RN/CDCES (+4.9%) | No significant difference | FGM group increased from 41.1% to 54.8% vs usual care SMBG (41.1%-46.9%, P = .0060) | |||

| TAR | Nonsignificant decrease in group C versus group A | rCGM decreased from 71% to 26.5% (P < .0001), but no significant difference vs SMBG (P = .82) | CGM odds of glycemic excursion decreased by 5.15% q30d (P < .001) but increased MAGE by 3.46% q30d (P < .001), no control | Improved in IGr from baseline to three months (-6.57%, P = .0184), no control | Time > 8.9 mmol/L decreased from 34.2% to 21.3% (-12.9%) | Decreased in subgroup who wore pCGM twice, more in MD model (-20.2%) versus RN/CDCES (-5.9%). | ||||

| TBR | No significant difference between groups | rCGM group increased from 0% to 2% (P < .0001), but not statistically different from SMBG (P = .18) | No statistically significant; for <70: -0.49% (CI = -1.26 to 0.27); For <54: -0.86% (CI = -1.91 to 0.19), no control | Increased in subgroup who wore pCGM twice, more in the MD model (+2.6%) than RN/CDCES (+0.9%) | ||||||

| Episodes of hypoglycemia | One severe hypoglycemic event in control, four symptomatic hypoglycemic events in four intervention participants. No DKA or HHS | Two hypoglycemic episodes in a patient where an ambulance was called but self-treated and no loss of consciousness | No significant increased risk. | % time where glucose was <54 mg/dL increased in two pCGM wears, more in the MD model (+1.1%) than in RN/CDCES model (+0.2%). | False episodes of hypoglycemia where AGP reported hypoglycemia but was refuted by SMBG (13.8% of participants) | Level 2 hypoglycemia (<3 mmol/L): FGM 33%, usual care 31% over 12 months. No severe hypoglycemia | Decreased hospitalizations for DKA and hypoglycemia from 5.1/100 patient-years to 2.9 patient-years (P = .004) | |||

| Patient satisfaction | DTSQ scores increased for groups B and C (P =

.0277 and P = .0225) Understanding of self-management needs improved in 100% of participants |

46 participants in the rCGM substudy arm scored the rCGM devices at 6 of 7 regarding satisfaction and 4.5 out of 7 on willingness to continue rCGM | 70% CGM better understand daily activity and diet vs 16% FSG, 90% positively impacted care vs 56%, device helpfulness 92.9 vs 79.7 (on a 0-100 scale) | Generally well tolerated, minimal issues with skin irritation, also sensor adhesion problems | Difference in diabetes-specific distress as measured by PAID was not significant (P = .61) | |||||

| Staff satisfaction | Staff (n = 47) agreed glucose reports supported effective communication with patients (96%), easy to read (91%) | Nurses scored rCGM median IQR 7 of 7 regarding satisfaction and willingness to continue | ||||||||

| Subgroups of patients with diabetes benefiting most | Group C using MDI or biphasic insulin therapy (n = 29) decreased HbA1c -0.67%, P = .0010, but not for those using basal only | Baseline A1c >9% (1.22% reduction), lowest reduction (0.12%) if baseline HbA1c between 6.0% and 7.0%, type 1 0.79% reduction vs 0.48% | Significantly improved HbA1c in participants managed by pharmacists. Pt w/o baseline insulin had 0.5% > A1c reduction than pts on insulin (P = .01) | Age <60 years, higher baseline HbA1c, multiple doses of insulin, lower SES independently associated with a clinically significant HbA1c improvement | ||||||

Abbreviations: CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; is-CGM, intermittently scanned continuous glucose monitoring; FGM, flash glucose monitoring; rCGM, retrospective continuous glucose monitoring; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose; FSG, finger-stick glucose; HHS, hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome; CDCES, Certified Diabetes Care and Education Specialist; AGP, ambulatory glucose profile; PAID, problem areas in diabetes questionnaire; TIR, time in range; TAR, time above range; TBR, time below range; CI, confidence interval; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; IQR, interquartile range; MDI, multiple daily insulin injections; SES, socioeconomic status;; CGMS, continuous glucose monitoring system; DTSQ, Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire.

Glycemic Control

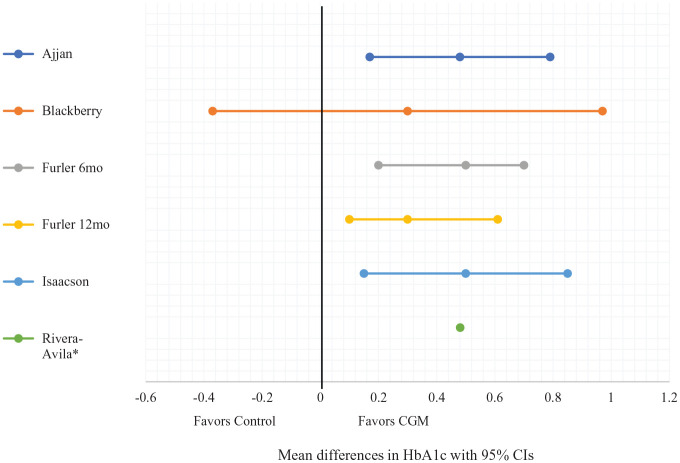

Our results suggest that CGM/is-CGM may be more effective at lowering HbA1c than usual care by a WMD of −0.43% (12 mg/dL, 5 mmol/mol) from the RCTs.27-31Figure 2 depicts the mean differences with 95% CIs in the five controlled interventional trials (four RCTs and one NRCT).27-31 Only one of three RCTs showed that CGM/is-CGM improved TIR compared with usual care27-29 and neither of the two RCTs comparing TAR and TBR of CGM with usual care showed a significant difference.27,28 The certainty of evidence found in the RCTs is moderate and details of our quality assessment are found in Supplementary Figure 1 and Table 3.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of mean differences with 95% CIs of HbA1c at study end between the intervention (CGM) and control groups.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring.

*Values for CI requested from original authors; no response.

Table 3.

Summary of GRADE Assessment.

| Certainty assessment: | Certainty of evidence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies | Study design | 1. Risk of bias | 2. Imprecision | 3. Inconsistency | 4. Indirectness | 5. Publication bias | |

| Mean difference in HbA1c at study end between CGM/is-CGM and usual care | |||||||

| 5 (Ajjan, Blackberry, Furler, Isaacson, Rivera) | Controlled interventions (four RCTs and one NRCT) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| 1a. Lack of allocation concealment: 2/5 studies

(Furler, Rivera lack) 1b. Lack of blinding: 5/5 studies—for participants/providers; 4/5 studies—unknown for outcome assessors 1c. Incomplete accounting of patients and outcome events: 0/5 studies 1d. Selective outcome reporting bias: 0/5 studies 2. Ajjan, Furler, Isaacson precise (no data for Rivera, Blackberry non-sig) 4. Differences in population: 1/5 studies (Rivera) Intervention: 1/5 studies (Blackberry included insulin initiation as additional intervention) Outcome: 0/5 studies Indirect comparison: 0/5 studies | |||||||

| Mean difference in HbA1c from baseline to study end for CGM/is-CGM | |||||||

| 4 (Ajjan, Furler, Isaacson, Rivera) | Controlled interventions (three RCTs and one NRCT) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| 1a. Lack of allocation concealment: 2/4 studies

(Furler, Rivera) 1b. Lack of blinding: 4/4 studies—for participants/providers; 3/4 studies—unknown for outcome assessors 1c. Incomplete accounting of patients and outcome events: 0/4 studies 1d. Selective outcome reporting bias: 0/4 studies 2. Ajjan, Furler, Isaacson precise (no data for Rivera) 4. Differences in population: 1/4 studies (Rivera) Intervention: 0/4 studies Outcome: 0/4 studies Indirect comparison: 0/4 studies | |||||||

| Mean difference in HbA1c from baseline to study end for CGM/is-CGM | |||||||

| 3 (Sherrill, Simonson, Tsur) | Cohort studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Low |

| 1a. Failure to develop/apply appropriate

eligibility criteria (inclusion of control population): 0/3

studies 1b. Flawed measurement of both exposure and outcome: 0/3 studies 1c. Failure to adequately control confounding: 2/3 studies (Sherrill and Simonson) 1d. Incomplete follow-up: 1/3 studies (Sherrill N/A data) 4. Differences in population: 0/3 studies Intervention: 2/3 studies (Sherrill pharmacy visits, Simonson MD/RN models) Outcome: 0/3 studies Indirect comparison: 0/3 studies | |||||||

| Mean difference in HbA1c from baseline to study end for CGM/is-CGM | |||||||

| 2 (Salzsieder, Van Dril) | Pre-post interventions | Very serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Very low |

| 1a. Failure to develop/apply appropriate

eligibility criteria (inclusion of control population): 4/6

studies (Van Dril unclear eligibility/selection criteria;

Van Dril unknown if representative; in both studies, not all

eligible participants enrolled) 1b. Flawed measurement of both exposure and outcome: 0/2 studies 1c. Failure to adequately control confounding: 1/2 studies (Van Dril, many confounders) 1d. Incomplete follow-up: 1/2 studies (Salzsieder >20% loss to f/u) 4. Differences in population: 0/2 studies Intervention: 1/2 studies (Salzsieder with additional KADIS) Outcome: 0/2 studies Indirect comparison: 0/2 studies | |||||||

| Mean difference of change in % TIR of CGM/is-CGM compared with usual care | |||||||

| 3 (Ajjan, Blackberry, Furler) | RCTs | Serious | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Very low |

| 1a. Lack of allocation concealment: 1/3 studies

(Furler) 1b. Lack of blinding: 3/3 studies—for participants/providers; 2/3 studies—unknown for outcome assessors 1c. Incomplete accounting of patients and outcome events: 0/3 studies 1d. Selective outcome reporting bias: 0/3 studies 2. Furler precise (Ajjan CI crosses 0, Blackberry non-sig) 4. Differences in population: 0/3 studies Intervention: 0/3 studies Outcome: 0/3 studies Indirect comparison: 0/3 studies | |||||||

| Mean difference of change in % TAR of CGM/is-CGM compared with usual care | |||||||

| 2 (Ajjan, Blackberry) | RCTs | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Low |

| 1a. Lack of allocation concealment: 0/2

studies 1b. Lack of blinding: 2/2 studies—for participants/providers; 2/2 studies—unknown for outcome assessors 1c. Incomplete accounting of patients and outcome events: 0/2 studies 1d. Selective outcome reporting bias: 0/2 studies 2. Ajjan lower end of CI crosses 0, Blackberry non-sig 4. Differences in population: 0/2 studies Intervention: 0/2 studies Outcome: 0/2 studies Indirect comparison: 0/2 studies | |||||||

| Mean difference of change in % TBR of CGM/is-CGM compared with usual care | |||||||

| 2 (Ajjan, Blackberry) | RCTs | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Low |

| 1a. Lack of allocation concealment: 0/2

studies 1b. Lack of blinding: 2/2 studies—for participants/providers; 2/2 studies—unknown for outcome assessors 1c. Incomplete accounting of patients and outcome events: 0/2 studies 1d. Selective outcome reporting bias: 0/2 studies 2. Ajjan lower end of CI crosses 0, Blackberry non-sig 4. Differences in population: 0/2 studies Intervention: 0/2 studies Outcome: 0/2 studies Indirect comparison: 0/2 studies | |||||||

Abbreviations: HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; is-CGM, intermittently scanned continuous glucose monitoring; RCT, randomized controlled trial; NRCT, nonrandomized controlled trial; TIR, time in range; CI, confidence interval; TAR, time above range; TBR, time below range.

Inclusive of all studies (RCTs, cohort, pre-post), without comparing to usual care, eight of ten studies demonstrated CGM/is-CGM significantly reduced HbA1c from baseline to study end by a WMD of −0.31% (9 mg/dL, 3 mmol/mol).27-36 However, the certainty of evidence is low to moderate, depending on the study design, which is summarized in Supplementary Figure 1 and Table 3.

We have grouped the analysis of each outcome by diabetes type to better assist the reader in navigating the body of existing literature.

Type 2 diabetes

Two RCTs demonstrated CGM/is-CGM improved HbA1c at 230 days after implementation (8.6%-8.2%, P = .004) 27 and six months (P < .001) 29 respectively, but not at 12 months (P = .059). One NRCT showed improved HbA1c in CGM than control by 0.481%, P = .023 (using adjusted diff-in-diff estimator) after three months. 31 Although one RCT suggested is-CGM (FGM, Freestyle Libre Pro) can improve TIR (P = .006), 29 another exploratory RCT concluded no statistically significant difference between CGM and SMBG in HbA1c, TBR, TIR, and TAR. 28

One cohort study demonstrated a HbA1c reduction of 0.6% (P = .006) at three to six months post-CGM and improvement in TIR and TAR (+17.8% and −20.2% in MD model, +4.9% and −5.9% in RN/Certified Diabetes Care and Education Specialist [CDCES] model, respectively). 34

Type 1 diabetes

A large observational cohort study found that HbA1c declined from 8.1% to 7.9% after three months (P < .001) and was sustained for up to 15 months. In addition, about 25.5% of the overall group recorded a HbA1c reduction of ≥0.5%. 34

Studies including both T1DM and T2DM

One RCT demonstrated CGM can reduce HbA1c an additional −0.5% compared with SMBG (P = .001) 30 and one cohort study also demonstrated reduced HbA1c after six months of CGM use. 33

One pre/post study showed CGM can decrease HbA1c by 0.62% (P < .01) and TAR from 8.2 to 5.1 hours a day (P < .05), 34 but the other did not record any significant difference. 36

Decreased Rates of Hypoglycemia

Three studies looked at TBR. Two RCTs did not find a significant difference in TBR between CGM and usual care,27,28 but one study reported that their subgroup of participants who wore CGM for an additional time period increased their TBR (+2.6% in MD model and +0.9% in RN/CDCES-model). 34

One cohort study found is-CGM (FGM) use reduced overall hospital admissions for hypoglycemia (from 5.1/100 patient-years to 2.9, P = .004), as well as hospitalizations for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)/hypoglycemia (P = .004). 35 One RCT reported no episodes of DKA or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome, although a greater percentage of their participants on CGM experienced hypoglycemia (4.2% vs 1.9%). 27 Two more studies demonstrated no significant increased risk of hypoglycemia with CGM 32 or is-CGM (FGM) use compared with usual care over 12 months. 29

Patient and Staff Satisfaction

Patient satisfaction

A variety of patient satisfaction questionnaires were used between the studies. The Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire reported CGM helped participants improve their understanding of self-management needs (100%), glucose abnormalities (96%), treatment changes (99%), and how therapies work (99%). 27 The Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life questionnaire found participant satisfaction was higher for the CGM group, scoring 6 out of 7 (P = .031). 28 One study found a nonsignificant difference between the is-CGM (FGM) group and the usual care group in the Problem Areas in Diabetes, a diabetes-specific distress scoring scale. 29 Another study found patient satisfaction was higher in their CGM arm (90%) compared with SMBG (56%) and 70% in the CGM group reported better understanding of daily activity and diet compared with 16% for SMBG. 29

Staff satisfaction

Most health care professionals in one RCT reported that the CGM reports assisted in effective communication with patients (96%) and they were easy to read (91%) and understand (85%). 27 The staff nurses in the INITIATION study scored CGM at 7 out of 7 in terms of both satisfaction and willingness to continue CGM use. 28

Subgroups Benefiting From CGM/is-CGM

Certain subgroups benefited more from CGM/is-CGM. Participants using MDI therapy were independently associated with decreased HbA1c (P < .001). 35 Another study similarly showed that their participants with four CGM wears using MDI or biphasic insulin showed a larger decrease of HbA1c (0.67%, P = .001). 27 Participants with higher baseline HbA1c demonstrated that CGM/is-CGM can result in greater reductions in HbA1c (baseline HbA1c >9%: −1.22% vs HbA1c 6%–7%: −0.12% 30 and baseline HbA1c ≥8%: −0.6%, P < .001). 35 However, one cohort study found that patients not treated with insulin had a larger reduction in HbA1c than those treated with insulin (difference of 0.5%, P = .01). 33

HbA1c decreased for participants with low and medium socioeconomic status (SES, which is not defined in the study, P < .001) but not for high SES (P = .187). For age, HbA1c decreased in all ages (P < .001) except 61+ (P = .115). 35 In another study, participants with T1DM had a greater benefit of CGM use (−0.79% HbA1c reduction vs −0.48% in T2DM). 32

Discussion

Summary

Our review suggests, with moderate certainty of evidence, that CGM/is-CGM may be more effective at lowering HbA1c than usual care by a WMD of −0.43% (12 mg/dL, 5 mmol/mol)27-31 in the RCTs. However, according to our quality and risk of bias assessment, these five trials had notable biases, limiting our certainty of evidence. In addition, most of these trials were of short duration; only one trial evaluated the effects of is-CGM (FGM) beyond seven months and that study did not find significant HbA1c reduction at 12 months. 29 It is worth noting that CGM was not the main intervention in one of the studies; CGM was used to evaluate insulin initiation, but within the study design, participants using CGM were compared with participants using SMBG. 28

Regarding TIR, our review of three RCTs shows very low certainty of evidence that CGM/is-CGM is superior to usual care.27-29 Similarly, from our review of two RCTs, there is low certainty of evidence that CGM use results in improved TAR compared with usual care.27,28 For hypoglycemia, only one of four studies found that is-CGM (FGM) could decrease hospitalizations for DKA and/or hypoglycemia 35 and there is low certainty of evidence that CGM can reduce TBR compared with usual care.27,28

Studies have highlighted that only consistent use of CGM yields improved clinical outcomes,37-39 which suggests patient satisfaction is clinically relevant. Based on our review, CGM/is-CGM appears to have high patient satisfaction as all four studies measuring this outcome recorded generally favorable responses.27-30 Moreover, critical components of success with CGM/is-CGM are appropriate patient selection and adequate clinician training and support. Although our review of staff satisfaction with CGM was limited to two studies, both studies demonstrated positive responses.27,28

MDI therapy,27,32 higher baseline HbA1c,32,35 and T1DM 35 were variables resulting in more significant reductions in HbA1c. One study, however, did demonstrate greater HbA1c reduction in non-insulin-treated diabetes, but this study had significant heterogeneity among participants along with many confounding interventions influencing their results. 33

The included studies that used is-CGM utilized first-generation is-CGM devices that only allowed alerts for actual hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. The advent of second-generation is-CGM allows the device to provide alerts for anticipated out-of-range values, which allows the patient to adjust their diet, exercise, and medication in real time. Further research on second-generation is-CGM is needed to evaluate benefits in glycemic control and avoidance of hypoglycemia.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this analysis is the first to systematically review the clinical benefits of CGM/is-CGM specifically in primary care. The strengths include a comprehensive literature search; a clinically relevant summary of the benefits of CGM/is-CGM, including staff/patient satisfaction; an analysis of multiple diabetic subgroups; and the use of validated quality assessment tools. Acknowledged limitations include heterogeneity of study designs, study outcomes and participant baseline therapy which precluded rigorous meta-analysis, exclusion of non-English-language sources, and underpowered studies. Only two studies used is-CGM (FGM) and only two studies had prolonged and sustained CGM/is-CGM use, so we were unable to compare CGM with is-CGM and sustained use with intermittent use. In addition, we observed performance biases as no study blinded participants, detection biases as minimal studies blinded outcome assessors, and seven of ten studies were either funded by industry or disclosed possible conflicts of interest.

Although four studies yielded favorable patient satisfaction scores, no study specifically evaluated whether or to what extent individualized patient training was provided. Because adequate patient education is paramount for CGM/is-CGM benefit, future studies can evaluate how the quality and quantity of individualized patient training affects outcomes.

Comparison With Existing Literature

Our findings are consistent with Maiorino et al’s systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs, which found that CGM modestly reduces HbA1c by 0.17% in unmasked short-term studies among persons treated with intensive insulin regimens. 40 Also complementing Maiorino’s et al’s findings, our review suggests that CGM/is-CGM may be more suitable for persons on intensive insulin therapy. 40 We cannot conclude whether SES has an association with CGM/is-CGM benefit as Tsur et al indicate low SES (SES not defined in their study) results in improved HbA1c, 32 but Tan et al’s baseline analysis of the GP-OSMOTIC study showed the opposite. 41

Interestingly, our review has shown that CGM/is-CGM can help lower HbA1c; however, similar benefit was not seen in two of three RCTs for TIR and both RCTs for TAR and TBR. This is inconsistent with both Maiorino et al and Beck et al’s findings.40,42 Ajjan et al attributed this discrepancy to the Hawthorne effect 27 and Blackberry et al’s study was not powered sufficiently to find a significant effect of CGM on HbA1c, TIR, TAR, or TBR compared with usual care. 28 Additional research is needed to determine whether this observation is related to study design or an actual difference in effects is present between CGM in primary care compared with specialty care.

Conclusions

Primary care providers should familiarize themselves with this new technology and utilize it in patients who would benefit from more rapid titration of insulin. Shared decision-making with the patient can set the appropriate shared expectation of modest benefit of glycemic control with minimal risk of hypoglycemia. In addition, with the acceleration of a shift to telemedicine, CGM technology can support both patient-centered out-of-office care and collaboration between the patient, the primary care provider, and, if needed, an endocrinologist in consultation.

As the complexity of diabetes management in the primary care setting continues to increase, 43 CGM/is-CGM is an attractive tool. This increasingly common technology has demonstrated benefit in T1DM and, to a lesser extent, T2DM. Because diabetes, particularly T2DM, is most commonly treated in the primary care setting, 44 this review focuses on CGM/is-CGM’s efficacy in a clinic environment where the attention and focus are not primarily on diabetes but also on screening, prevention, and the care of non-diabetes-related conditions. This review acknowledges the short-term benefit of CGM/is-CGM. However, before this promising technology becomes widely adopted into primary care practice, more research is required to confirm its long-term benefits of both improving glycemic control and reducing adverse events.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dst-10.1177_19322968211070855 for The Benefits of Utilizing Continuous Glucose Monitoring of Diabetes Mellitus in Primary Care: A Systematic Review by Alexander Kieu, Jeffrey King, Romona Devi Govender and Linda Östlund in Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dst-10.1177_19322968211070855 for The Benefits of Utilizing Continuous Glucose Monitoring of Diabetes Mellitus in Primary Care: A Systematic Review by Alexander Kieu, Jeffrey King, Romona Devi Govender and Linda Östlund in Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Mariam Al Ahbabi for her support in locating all full-text articles and for verifying the nonpredatory status of all included open access papers with the help of Cabell’s Predatory Report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CDCES, Certified Diabetes Care and Education Specialist; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; CI, confidence interval; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; FGM, flash glucose monitoring; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; is-CGM, intermittently scanned continuous glucose monitoring; MDI, multiple daily injection (of insulin); NRCT, nonrandomized controlled trial; PCPs, primary care physicians; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; rt-CGM, real-time continuous glucose monitoring; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; SES, socioeconomic status; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; TAR, time above range; TBR, time below range; TIR, time in range; WMD, weighted mean difference.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: Given this manuscript is a systematic review, an ethics approval was not obtained.

Registration and Protocol: This review was registered under PROSPERO, the international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews in health and social care (Registration No. CRD42021229416). A protocol was submitted and is currently under review.

Availability of Data, Code, and Other Materials: Data extracted from included studies and the data used for all analyses were obtained directly from each study.

ORCID iD: Alexander Kieu  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5434-9705

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5434-9705

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Barr ELM, Zimmet PZ, Welborn TA, et al. Risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in individuals with diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity, and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Circulation. 2007;116:151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavalot F, Pagliarino A, Valle M, et al. Postprandial blood glucose predicts cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes in a 14-year follow-up: lessons from the San Luigi Gonzaga Diabetes study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2237-2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harding JL, Pavkov ME, Magliano DJ, et al. Global trends in diabetes complications: a review of current evidence. Diabetologia. 2019;62:3-16. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4711-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregg EW, Li Y, Wang J, et al. Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States, 1990-2010. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(16):1514-1523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan MAB, Hashim MJ, King JK, et al. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes—global burden of disease and forecasted trends. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020;10(1):107-111. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.191028.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathan DM, Genuth S, Lachin J, et al. ; Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 1998;352:837-853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edelman SV, Polonsky WH.Type 2 diabetes in the real world: the elusive nature of glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1425-1432. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park C, Le QA.The effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of literature and meta-analysis. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2018;20(9):613-621. doi: 10.1089/dia.2018.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Diabetes Association. Diabetes technology: standards of medical care in diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(suppl 1):S85-S99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunberger G, Sherr J, Allende M, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: the use of advanced technology in the management of persons with diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2021;27:505-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ajjan R, Slattery D, Wright E.Continuous glucose monitoring: a brief review for primary care practitioners. Adv Ther. 2019;36(3):579-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelman SV, Cavaioloa TS, Boeder S, Pettus J.Utilizing continuous glucose monitoring in primary care practice: what the numbers mean. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021;15(2):199-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch IB.Professional flash continuous glucose monitoring as a supplement to A1c in primary care. Postgrad Med. 2017;129(8):781-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unger J, Kushner P, Anderson JE.Practical guidance for using the FreeStyle Libre flash continuous glucose monitoring in primary care. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(4):305-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adkison JK, Chung P.Implementing continuous glucose monitoring in clinical practice. Fam Pract Manag. 2021;28(2):7-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stankiewicz K.Dexcom’s Super Bowl ad with Nick Jonas sparked record interest in its glucose monitor, CEO says. CNBC. February12, 2021. http://www.cnbc.com. Accessed May 2, 2021.

- 18.Vigersky RA, Fish L, Hogan P, et al. The clinical endocrinology workforce: current status and future projections of supply and demand. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(9):3112-3121. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robertson SL, Shaughnessy AF, Slawson DC.Continuous glucose monitoring in type 2 diabetes is not ready for widespread adoption. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(11):646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabell’s Scholarly Analytics. Cabell’s predatory report; 2021. https://www2.cabells.com/about-predatory.

- 22.Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software; 2021. https://www.covidence.org.

- 23.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study quality assessment tools. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed June 24, 2021.

- 24.Siemieniuk R, Guyatt G. Evidence based medicine (EBM) toolkit: what is GRADE? BMJ Best Practice. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/toolkit/learn-ebm/what-is-grade/.

- 25.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al., eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 6.0; 2019. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed July 1, 2021.

- 26.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T.Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ajjan RA, Jackson N, Thomson SA.Reduction in HbA1c using professional flash glucose monitoring in insulin-treated type 2 diabetes patients managed in primary and secondary care settings: a pilot, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2019;16(4):385-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blackberry ID, Furler JS, Ginnivan LE, et al. An exploratory trial of basal and prandial insulin initiation and titration for type 2 diabetes in primary care with adjunct retrospective continuous glucose monitoring: INITIATION study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;106(2):247-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furler J, O’Neal D, Speight J, et al. Use of professional-mode flash glucose monitoring, at 3-month intervals, in adults with type 2 diabetes in general practice (GP-OSMOTIC): a pragmatic, open-label, 12-month, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(1):17-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isaacson B, Kaufusi S, Sorensen J, et al. Demonstrating the clinical impact of continuous glucose monitoring within an integrated healthcare delivery system [published online ahead of print September 16, 2020]. J Diabetes Sci Technol. doi: 10.1177/1932296820955228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rivera-Ávila DA, Esquivel-Lu AI, Salazar-Lozano CR, Jones K, Doubova SV.The effects of professional continuous glucose monitoring as an adjuvant educational tool for improving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC Endocr Disord. 2021;21(1):79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salzsieder E, Augstein P, Vogt L, et al. Telemedicine-based KADIS® combined with CGMS™ has high potential for improving outpatient diabetes care. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007;1(4):511-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherrill CH, Houpt CT, Dixon EM, Richter SJ.Effect of pharmacist-driven professional continuous glucose monitoring in adults with uncontrolled diabetes. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(5):600-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simonson G, Bergenstal RM, Johnson ML, Davidson JL, Martens TW.Effect of professional CGM (pCGM) on glucose management in type 2 diabetes patients in primary care. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2021;15(3):539-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsur A, Cahn A, Israel M, Feldhamer I, Hammerman A, Pollack R.Impact of flash glucose monitoring on glucose control and hospitalization in type 1 diabetes: a nationwide cohort study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2021;37(1):e3355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Dril E, Schumacher C. Impact of professional continuous glucose monitoring by clinical pharmacists in an ambulatory care setting. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2018;1(2):184-185. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirsch IB, Abelseth J, Bode BW, et al. Sensor-augmented insulin pump therapy: results of the first randomized treat-to-target study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2008;10(5):377-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garg S, Zisser H, Schwartz S, et al. Improvement in glycemic excursions with a transcutaneous, real-time continuous glucose sensor: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(1):44-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamborlane WV, Beck RW, Bode BW, et al. ; Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study Group. Continuous glucose monitoring and intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(14):1464-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maiorino MI, Signoriello S, Maio A, et al. Effects of continuous glucose monitoring on metrics of glycemic control in diabetes: a systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(5):1146-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan ML, Manski-Nankervis JA, Thuraisingam S, Jenkins A, O’Neal D, Furler J.Socioeconomic status and time in glucose target range in people with type 2 diabetes: a baseline analysis of the GP-OSMOTIC study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2018;18(1):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beck RW, Riddlesworth T, Ruedy K, et al. Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes using insulin injections: the DIAMOND randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(4):371-378. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shrivastav M, Gibson W, Jr, Shrivastav R, et al. Type 2 diabetes management in primary care: the role of retrospective, professional continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Spectr. 2018;31(3):279-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidson JA.The increasing role of primary care physicians in caring for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(suppl 12):S3-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dst-10.1177_19322968211070855 for The Benefits of Utilizing Continuous Glucose Monitoring of Diabetes Mellitus in Primary Care: A Systematic Review by Alexander Kieu, Jeffrey King, Romona Devi Govender and Linda Östlund in Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dst-10.1177_19322968211070855 for The Benefits of Utilizing Continuous Glucose Monitoring of Diabetes Mellitus in Primary Care: A Systematic Review by Alexander Kieu, Jeffrey King, Romona Devi Govender and Linda Östlund in Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology