Abstract

Background

Intraperitoneal insulin delivery has proven to safely overcome a major limit of subcutaneous delivery—meal announcement—and has been able to optimize glycemic control in adults under controlled experimental conditions. In addition, intraperitoneal delivery avoids peripheral hyperinsulinemia resulting from the subcutaneous route and restores a physiological liver gradient.

Methods

Relying on a unique data set of intraperitoneal closed-loop insulin delivery obtained with a Model Predictive Controller (MPC), we develop a compartmental model of intraperitoneal insulin kinetics, which, once included in the UVa/Padova T1D simulator, will facilitate the investigation of various control strategies, for example, the simpler Proportional Integral Derivative controller versus MPC.

Results

Intraperitoneal insulin kinetics can be described with a 2-compartment model including liver and plasma.

Conclusion

Intraperitoneal insulin transit is fast enough to render irrelevant the addition of a peritoneal compartment, proving the peritoneum being a virtual—not actual—transit space for insulin delivery.

Keywords: intraperitoneal insulin delivery, closed-loop, type 1 diabetes, insulin kinetics

Introduction

Automated insulin delivery (AID) using the subcutaneous route has shifted the paradigm of type 1 diabetes (T1D) treatment by largely improving time in target glucose range even in patients with suboptimal glucose control. 1 However, the non-physiological subcutaneous insulin route provides suboptimal postprandial glucose control and still limits the larger use of AID due to the burden of device use and meal announcement need.

Intraperitoneal delivery avoids peripheral hyperinsulinemia resulting from subcutaneous route and restores a more physiological insulin delivery with a preserved first hepatic pass.2-5 Intraperitoneal route has been proven to safely overcome major limit of subcutaneous AID, as the meal announcement, and has been effective to optimize glycemic control under controlled experimental conditions.6-8 However, the peritoneal compartment could itself add a non-negligible delay to insulin absorption during fully closed-loop (CL) AID with unannounced meal. To sort it out, intraperitoneal insulin kinetics modeling represents a mandatory step: intraperitoneal insulin kinetics has never been described in closed-loop studies, as the only available model is based on open-loop data. 9 Herein, relying on a unique data set of intraperitoneal CL insulin delivery, we develop a compartmental model of intraperitoneal insulin kinetics. Four candidate models have been evaluated on a real-patient data set.

Methods

Data Set Description

Model development was based on previously published cohort of T1D adults who underwent a 24-hour intraperitoneal CL session using the DiaPort intraperitoneal insulin delivery system. 7 Participants consumed three unannounced meals with a 70 g-carbohydrate (CHO) dinner at ~7:00 pm, a 40 g-CHO breakfast at ~8:00 am, and a 70 g-CHO lunch at ~1:00 pm. The CL algorithm was a Zone Model Predictive Control (Zone-MPC) algorithm adjusted for insulin clearance. Blood drawing were performed every hour except around meals, when it was drawn 15, 10, and 5 minutes prior to the meal and 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 80, 100, and 120 minutes after the meal. Current analysis selected data sets obtained from participants with at least 95% of insulin samples over the 24-hour study period. Therefore, we included nine out of ten subjects from the original study cohort for the modeling definition. 7

Modeling Methodology

Intraperitoneal kinetic models

Four linear compartmental models were tested against the data of Dassau et al 7 (Figure 1). Compartmental models are a class of dynamic (ie, differential equation) models derived from mass balance considerations which are widely used for studying quantitatively the kinetics of materials in physiological systems. 5 Briefly, a compartment is a quantity of material that acts as though it is well-mixed and kinetically homogeneous; a compartmental model consists of a finite number of compartments with specified interconnections among them, with the interconnections representing fluxes of material which physiologically constitute transport from one location to another or a chemical transformation or both.

Figure 1.

Four intraperitoneal insulin kinetics models. Abbreviations: RaIP, rate of intraperitoneal glucose appearance; IP, intraperitoneal; Il, liver insulin concentration; IP, plasma insulin concentration; IT, peripheral insulin concentration.

Model 1

This model assumes that the intraperitoneal system is a cascade of two compartments by using data of open- and closed-loop, 10 intraperitoneal insulin delivery undergoes a ~100% first-hepatic pass without intraperitoneal degradation. 11 The intraperitoneal system feeds the classical whole-body 3-compartment insulin kinetics model 12 describing the exchanges between liver, plasma, and peripheral tissues. The model equations are

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where denotes insulin delivery; , are insulin masses in the two intraperitoneal compartments, respectively; , , represent insulin mass in the liver, plasma, and peripheral compartments, respectively; the various are transfer rate parameters; VI is the plasma distribution volume assumed equal to 45 mL/kg as in Sherwin et al, 12 and the measured plasma insulin concentration.

Model 2

The intraperitoneal system is described as a single compartment feeding the same insulin kinetics model. The model equations are

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

where is insulin mass in the intraperitoneal compartment.

Model 3

Model 3 assumes that intraperitoneal kinetics is fast enough to make un-relevant the addition of intraperitoneal compartments, thus reducing to the 3-compartment insulin kinetics model, with entering directly the liver compartment, that is, the model is described by

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

Model 4

Model 4 assumes that the tissue compartment can be neglected due to its slow exchange with plasma, thus Model 3 reduces to the following 2-compartment model:

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

Model Identification

Models 1, 2, 3, and 4 were numerically identified on plasma insulin concentration data with a Bayesian Maximum a Posteriori (MAP) estimator. 5 Insulin measurement error was described as in Campioni et al. 13

Models 1 and 2

A priori information for , , , and was derived from Sherwin et al 12 —the constant value of 0.268 for was generalized to a distribution with SD of 25% since in Sherwin et al 12 Least Squares was used for model identification—while the intraperitoneal parameters and (Model 1) and (Model 2) were estimated from the data, that is, the first term of the cost function.

Model 3

A priori information for , , , , and was used as described above.

Model 4

A priori information for , , and was used as described above.

The most parsimonious model was selected based on standard criteria 5 : randomness of residuals, precision of parameter estimates (expressed as coefficient of variation [CV] = standard deviation/estimate), parameter physiological plausibility and model parsimony based on Bayesian information criterion (BIC). 14

Statistical analysis

Model parameters are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Skewness of the distributions was assessed by the Lilliefors test. SAAM v2.3 2012-2013 (The Epsilon Group) software was used for modeling.

Results

All four models exhibit a similar weighted residual pattern, that is, no improvement was brought by the additional parameters of Model 1, Model 2, Model 3, versus Model 4 and they were on average within the ±1 region. In Figure 2, the insulin data versus Model 4 prediction in a representative subject is shown, while the average weighted residual plot is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Model 4 fit (continuous line) against plasma insulin data (circles) for participant 9.

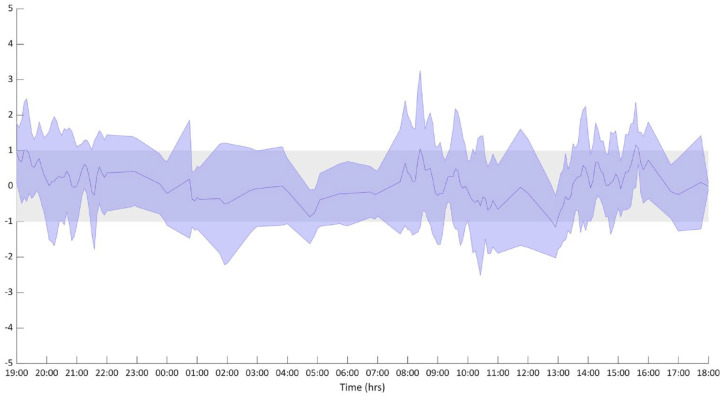

Figure 3.

Weighted residual plot on all the nine subjects. Data are presented as median and interquartile range. Modeling methodology requires that most of the weighted residuals lay in the +1/−1 region. 5

Model 1 exhibited a very fast transfer of insulin from compartment IP1 to IP2 (average was 0.000071 minutes so that Model 3 collapses into Model 2).

Model 2 exhibited in some participants unsatisfactory precision for (two subjects reached 1,050 and 128%). But more importantly, the transfer from the intraperitoneal compartment to the liver ( was physiologically unplausible being 76 minutes on average.

Model 3 performed satisfactorily, but the transfer rate parameters of the plasma-tissue exchange were more difficult to estimate, in particular the parameter reached an uncertainty of 178% in one subject.

Model 4 by neglecting the tissue compartment was accurately resolvable and we report its satisfactory precision (CV%) in Table 1.

Table 1.

Model 4 Parameter Estimates With Their Coefficient of Variation (in Parenthesis) for the Nine Participants.

| ID | kP, L | kL, P | k0, P | k0, L |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.005 (20%) | 0.165 (39%) | 0.121 (51%) | 0.016 (7%) |

| 2 | 0.016 (21%) | 0.275 (23%) | 0.110 (55%) | 0.011 (25%) |

| 3 | 0.008 (15%) | 0.418 (16%) | 0.161 (39%) | 0.004 (23%) |

| 4 | 0.007 (15%) | 0.427 (14%) | 0.091 (68%) | 0.003 (32%) |

| 5 | 0.005 (22%) | 0.291 (23%) | 0.129 (48%) | 0.012 (13%) |

| 6 | 0.003 (28%) | 0.216 (30%) | 0.087 (70%) | 0.009 (10%) |

| 7 | 0.010 (16%) | 0.383 (14%) | 0.086 (71%) | 0.004 (36%) |

| 8 | 0.012 (15%) | 0.404 (15%) | 0.148 (42%) | 0.003 (48%) |

| 9 | 0.007 (20%) | 0.322 (20%) | 0.137 (45%) | 0.011 (12%) |

| All | 0.008 ± 0.002 (19%) |

0.322 ± 0.062 (21%) |

0.119 ± 0.062 (54%) |

0.008 ± 0.001 (23%) |

Mean ± standard deviation for all participants and average precision of parameter estimates (in parenthesis) are reported.

We also calculated BIC for Models 3 and 4, which, on average, was 237 and 234, respectively, confirming that Model 4 is the most parsimonious.

Discussion

We described for the first-time intraperitoneal insulin kinetics identified from intraperitoneal CL data with a 2-compartment model including liver and plasma. Intraperitoneal kinetics was fast enough to render irrelevant the addition of a peritoneal compartment, proving the peritoneum being a virtual—not actual—transit space for insulin delivery.

The initial 5-compartment Model 1 resulted into a redundant system with two intraperitoneal compartments with fast transit, when tested against individual in vivo data. Model 2 with a single-intraperitoneal compartment turned out to be poorly reproducible with unsatisfactory precision of some parameter estimates. The exclusion of the intraperitoneal compartment led to the 3-compartment model of intraperitoneal insulin kinetics. Finally, to make the model fully resolvable we neglected the tissue compartment, thus arriving at the 2-compartment Model 4. Model 4 also allows to estimate hepatic extraction and post-hepatic insulin [48 ± 47% and 12 ± 20% mL/min, respectively] with similar results to previous reports.14,15 Our finding confirms that the 2-compartment structure of the liver-plasma model of the UVA/Padova T1D Simulator,16,17 also used in Toffanin et al 8 is adequate, but the use of real intraperitoneal has revealed that parameter values in the simulator should be updated for further intraperitoneal studies.

The major strength of this model is the use of in vivo data from CL intraperitoneal study. 7 In Dassau et al, 7 the Zone-MPC controller was, in absence of in vivo data, designed in silico. While the Zone-MPC was effective at preventing hypoglycemia, postprandial glucose control remained suboptimal. The fast intraperitoneal insulin kinetics would allow us to investigate simpler control algorithms, for instance, Proportional Integral Derivative.

The major limitations of our findings are (a) the 1-day time of observation and (b) the assumption of a constant insulin hepatic extraction, that might be affected by daily activities or dietary content. 15

To date, this is the first intraperitoneal insulin delivery model identified on intraperitoneal CL data that will enable to study in silico new control algorithms for the next generation of intraperitoneal CL system.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AID, automated insulin delivery; T1D, type 1 diabetes; CL, closed-loop, CHO, carbohydrate, Zone-MPC, Zone Model Predictive Control.

Author Contributions: JL and CT performed model identification; AG and CC defined the three intraperitoneal insulin kinetics to be identified based on the data obtained during the clinical study and drafted the manuscript; ED, FJD, ER, and HZ conducted the original clinical study and critically reviewed the manuscript; CC was the principal investigator of this project and is the guarantor of this work. All authors reviewed and provided edits and comments on manuscript drafts and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: JL, AG, ER, CT, and CC have no conflict of interest to report related to this article; ED is currently an employee and shareholder of Eli Lilly and Company, the work presented in this article was performed as part of his academic appointment and is independent of his employment with Eli Lilly and Company; FJD reports equity, licensed IP, and is a member of the scientific advisory board of Mode AGC; HCZ is currently employed by Verily Diabetes. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Funding: The contrbuting authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: European Commission HORIZON2020, FORGETDIABETES-FET-EU951933 (to CC), JDRF (grant 17-2011-515), and National Institutes of Health (grants: R01DK085628, DP3DK101068) to HZ, FJD, and ED.The current study has been entirely supported by the European Commission HORIZON2020, FORGETDIABETES-FET-EU951933 (to CC).

ORCID iDs: Alfonso Galderisi  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8885-3056

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8885-3056

Francis J. Doyle  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3293-9114

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3293-9114

Eric Renard  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3407-7263

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3407-7263

Chiara Toffanin  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1288-3456

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1288-3456

Claudio Cobelli  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0169-6682

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0169-6682

References

- 1.Tauschmann M, Thabit H, Bally L, et al. Closed-loop insulin delivery in suboptimally controlled type 1 diabetes: a multicentre, 12-week randomised trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1321-1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giacca A, Caumo A, Galimberti G, et al. Peritoneal and subcutaneous absorption of insulin in type I diabetic subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77(3):738-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson J, Stephen R, Landau S, Wilson D, Tyler F.Intraperitoneal insulin administration produces a positive portal-systemic blood insulin gradient in unanesthetized, unrestrained swine. Metabolism. 1982;31(10):969-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schade D, Eaton R, Davis T, et al. The kinetics of peritoneal insulin absorption. Metabolism. 1981;30(2):149-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cobelli C, Carson E.Introduction to Modelling in Physiology and Medicine. 2nd ed.San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renard E, Place J, Cantwell M, Chevassus H, Palerm C.Closed-loop insulin delivery using a subcutaneous glucose sensor and intraperitoneal insulin delivery: feasibility study testing a new model for the artificial pancreas. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):121-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dassau E, Renard E, Place J, et al. Intraperitoneal insulin delivery provides superior glycaemic regulation to subcutaneous insulin delivery in model predictive control-based fully-automated artificial pancreas in patients with type 1 diabetes: a pilot study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(12):1698-1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toffanin C, Magni L, Cobelli C. Artificial pancreas: in silico study shows no need of meal announcement and improved time in range of glucose with intraperitoneal vs. subcutaneous insulin delivery. IEEE Trans Med Robot Bionics. 2021;3(2):306-314. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiavon M, Cobelli C, Dalla Man C.Modeling intraperitoneal insulin absorption in patients with type 1 diabetes. Metabolites. 2021;11(9):600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moret F, Schiavon M, Cobelli C, Dalla Man C.Insulin kinetics in patients with type 1 diabetes. GNB2020, June 10th-12th 2020. GNB2020 Proceedings, https://www.grupponazionalebioingegneria.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/GNB2020_Proceedings_full.pdf.

- 11.Dirnena-Fusini I, Åm M, Fougner A, Carlsen S, Christiansen S.Intraperitoneal insulin administration in pigs: effect on circulating insulin and glucose levels. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2021;9(1):e001929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherwin R, Kramer K, Tobin J, et al. A model of the kinetics of insulin in man. J Clin Invest. 1974;53(5):1481-1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campioni M, Toffolo G, Basu R, Rizza R, Cobelli C.Minimal model assessment of hepatic insulin extraction during an oral test from standard insulin kinetic parameters. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E941-E948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kass RE, Raftery AE.Bayes Factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995, 90:430, 773-795. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polidori DC, Bergman RN, Chung ST, Sumner AE.Hepatic and extrahepatic insulin clearance are differentially regulated: results from a novel model-based analysis of intravenous glucose tolerance data. Diabetes. 2016;65(6):1556-1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Visentin R, Campos-Náñez E, Schiavon M, et al. The UVA/Padova type 1 diabetes simulator goes from single meal to single day. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12(2):273-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Man CD, Micheletto F, Lv D, Breton M, Kovatchev B, Cobelli C.The UVA/PADOVA type 1 diabetes simulator: new features. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2014;8:26-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]