Abstract

Equine arteritis virus (EAV), the prototype arterivirus, is an enveloped plus-strand RNA virus with a genome of approximately 13 kb. Based on similarities in genome organization and protein expression, the arteriviruses have recently been grouped together with the coronaviruses and toroviruses in the newly established order Nidovirales. Previously, we reported the construction of pEDI, a full-length cDNA copy of EAV DI-b, a natural defective interfering (DI) RNA of 5.6 kb (R. Molenkamp et al., J. Virol. 74:3156–3165, 2000). EDI RNA consists of three noncontiguous parts of the EAV genome fused in frame with respect to the replicase gene. As a result, EDI RNA contains a truncated replicase open reading frame (EDI-ORF) and encodes a truncated replicase polyprotein. Since some coronavirus DI RNAs require the presence of an ORF for their efficient propagation, we have analyzed the importance of the EDI-ORF in EDI RNA replication. The EDI-ORF was disrupted at different positions by the introduction of frameshift mutations. These were found either to block DI RNA replication completely or to be removed within one virus passage, probably due to homologous recombination with the helper virus genome. Using recombination assays based on EDI RNA and full-length EAV genomes containing specific mutations, the rates of homologous RNA recombination in the 3′- and 5′-proximal regions of the EAV genome were studied. Remarkably, the recombination frequency in the 5′-proximal region was found to be approximately 100-fold lower than that in the 3′-proximal part of the genome.

Equine arteritis virus (EAV) is the prototype member of the family Arteriviridae (52). Based on similarities in genome organization, protein expression strategies, and the presumed common ancestry of their replicase genes (12), the arteriviruses have recently been grouped together with the coronaviruses and toroviruses in the newly established order Nidovirales (7, 15).

EAV is a spherical, enveloped RNA virus (for a review, see reference 52) and contains a positive-strand genome of approximately 12.7 kb (12). The virion envelope is derived from intracellular host cell membranes and contains five or six structural proteins (14, 52, 53). The envelope surrounds an isometric nucleocapsid, which is composed of the genomic RNA and multiple copies of the nucleocapsid (N) protein.

The EAV replicase is translated in the form of two large polyproteins, the open reading frame 1a (ORF1a) and ORF1ab proteins. The C-terminal part of the latter is produced by an ORF1a/1b ribosomal frameshift (12). Extensive studies on the proteolytic processing of the ORF1a and ORF1ab polyproteins have resulted in an apparently complete processing scheme (54, 62, 63, 66), which comprises the production of 12 end products (nsp1 to nsp12) and a large number of processing intermediates.

As in coronaviruses, the EAV structural proteins are translated from a 3′-coterminal nested set subgenomic mRNAs (sg mRNAs), which also share a common 5′-leader sequence that is derived from the 5′ end of the genome (12, 13, 52). In the genome, the transcription units for all sg mRNA bodies are preceded by transcription-regulating sequences (body TRSs), with the conserved sequence 5′-UCAAC-3′ (11, 13). The same conserved sequence can also be found at the 3′ end of the 211-nucleotide (nt) genomic leader sequence (leader TRS). The leader and body sequences of the sg RNAs are fused via a discontinuous transcription process (3, 30, 56). Nidovirus transcription is still only partially understood, but it has become clear that the TRSs (referred to as intergenic sequence in the coronavirus literature) play an essential role in this process (for a review, see reference 32). By using site-directed mutagenesis of TRSs in an EAV infectious cDNA clone (61), we have recently shown that EAV discontinuous transcription involves base pairing between the genomic leader TRS and the body TRS complements in the viral minus strand (64). Our data were most compatible with a model in which discontinuous transcription yields sg minus strands, which subsequently function as templates for sg mRNA synthesis (51, 64).

Defective interfering (DI) viruses have been widely used to study the replication of RNA viruses (9, 17, 20, 23, 33, 36, 48, 58, 67). The genomes of DI particles are truncated or rearranged RNA molecules which are derived from the helper virus genome. They have generally lost the potential to replicate autonomously due to deletions in the replicase gene(s), and thus their replication depends on the replicative proteins expressed by a coinfecting helper virus. DI RNAs have retained the cis-acting sequences required for replication and in most cases also those needed for encapsidation. Therefore, they are useful tools to study RNA virus replication, encapsidation, and recombination.

Recently, we have described the generation of DI-b, a natural EAV DI RNA of 5.6 kb, and we have reported the construction of pEDI, a full-length cDNA copy of EAV DI-b RNA from which replication-competent RNA can be transcribed in vitro (43). We have used this EDI RNA for deletion mutagenesis, and in this way the sequences that are likely to be required for efficient replication of EAV DI RNAs were reduced to at most 589 and 1,068 nt of the genomic 5′- and 3′-terminal regions, respectively, and a segment of at most 583 nt from the 3′ part of replicase ORF1b (43).

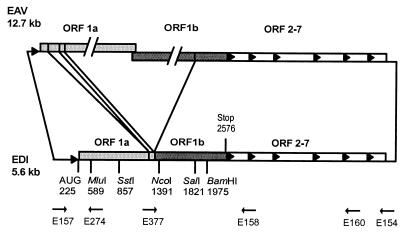

EDI RNA consists of three noncontiguous parts of the EAV genome (Fig. 1): (i) a 5′-terminal segment that includes the genomic leader sequence and the 5′-terminal 0.8 kb of ORF1a, (ii) an internal segment derived from the nsp2-coding region (ORF1a), and (iii) a 3′-terminal segment containing the 3′-terminal 1.2 kb of ORF1b, the complete structural gene region (ORF2a to ORF7), and the 3′ untranslated region of the genome. These three segments of the EDI replicon have been fused in frame with respect to the replicase gene. As a result, the EDI RNA contains a truncated replicase gene, which we will refer to as EDI-ORF, and encodes a truncated replicase polyprotein (EDI-protein) of 784 amino acids (aa). The presence of an ORF, often spanning almost the entire RNA molecule, was described for most coronavirus DI RNAs (38, 41, 47, 58). In addition, the presence of a long ORF has been observed for several DI RNAs of plant viruses (49, 68) and pestiviruses (27, 42). The importance of this translation unit in coronavirus DI RNA propagation has been addressed by a number of researchers. de Groot et al. (10) suggested that translation of the ORF could enhance DI RNA stability or that translating ribosomes could unfold the RNA and thereby facilitate its uncoating or packaging. Alternatively, there may be a cis requirement for specific protein sequences in coronavirus DI RNA replication (8, 35). In contrast, it has been shown that an ORF of only 60 nt is sufficient for the propagation of coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus DI RNAs (48).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the EAV and EDI genomes. The leader and body TRSs are depicted by arrowheads. The ORF1a- and ORF1b-derived segments of the EDI-ORF are indicated by different shadings. Positions of the EDI-ORF translation initiation and termination codons and the restriction sites used for generation of the various EDI-ORF frameshift mutants are also indicated. The positions of oligonucleotides used for RT-PCR are indicated by arrows.

In this study we have analyzed the importance of the EDI-ORF in EDI RNA replication. The EDI-ORF was disrupted at different positions by the introduction of frameshift mutations. These were found either to block DI RNA replication completely or to be removed within one virus passage, probably due to homologous recombination with the helper virus genome. Using recombination assays based on EDI RNA and full-length EAV genomes containing specific mutations, the rate of homologous RNA recombination in the 3′- and 5′-proximal regions of the EAV genome was studied. Remarkably, the recombination frequency in the 5′-proximal region was found to be approximately 100-fold lower than that in the 3′-proximal part of the genome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

Baby hamster kidney cells (BHK-21 cells) were grown in BHK-21 medium (Life Technologies Inc.) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum, 10% tryptose phosphate broth, and 10 mM HEPES. All EAV infections were carried out with the Bucyrus strain (16) at 39.5°C. All EDI passaging experiments were performed as described previously (43).

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Standard recombinant DNA procedures (50) were used. Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, and T7 RNA polymerase were obtained from Life Technologies. All enzyme incubations and biochemical reactions were performed according to the instructions of the manufacturers. Sequencing reactions were performed with a Big Dye Terminator kit (Perkin-Elmer) and analyzed with an ABI PRISM 310 genetic analyzer (Perkin-Elmer). All radiolabeled chemicals were obtained from Amersham/Pharmacia.

Construction of plasmids.

pEDI plasmid DNA (43) was digested with the restriction enzymes listed in Table 1. Next, 3′-recessed ends were filled and 5′-protruding ends were removed by using the Klenow fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I. Subsequent religation of the plasmid resulted in the insertion or deletion of four nucleotides. In this manner, we generated five EDI derivatives with a frameshift in the EDI-ORF and a translation termination codon just downstream of one of the restriction sites indicated in Table 1. The nomenclature of these mutants reflects the size of the truncated EDI-ORF; e.g., pEDI-404 contains a C-terminally truncated EDI-ORF encoding a protein of 404 aa. An EDI derivative carrying an EDI-ORF with an inactivated translation initiation codon (AUG to UAC at the position of the ORF1a translation initiation codon) was constructed by PCR mutagenesis. To generate EDI-ORF mutants which could express the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter gene from sg mRNA2 (Fig. 2B), a BamHI-XhoI fragment (nt 1975 to 5670) of these EDI-ORF mutants was replaced by the corresponding BamHI-XhoI fragment of pEDIC2 (43). Construct pEDIC2-4150 (43) and the full-length EAV cDNA clones with mutations (5′-UCAAC-3′ to 5′-UGAAG-3′) in either the leader TRS (mutant L3) or the RNA7 body TRS (mutant B3) (64) have been described previously.

TABLE 1.

Overview of EDI-ORF frameshift mutants

| Construct | Restriction site | Position (nt)a | Position of stop codon (nt)a | Length of EDI-protein (aa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pEDI | 2576 | 784 | ||

| pEDI-UAC | NAb | 225 | 224 | 0 |

| pEDI-127 | MluI | 589 | 605 | 127 |

| pEDI-215 | SstI | 857 | 869 | 215 |

| pEDI-404 | NcoI | 1391 | 1436 | 404 |

| pEDI-550 | SalI | 1821 | 1874 | 550 |

| pEDI-616 | BamHI | 1975 | 2072 | 616 |

Based on the wt pEDI sequence (43).

NA, not applicable.

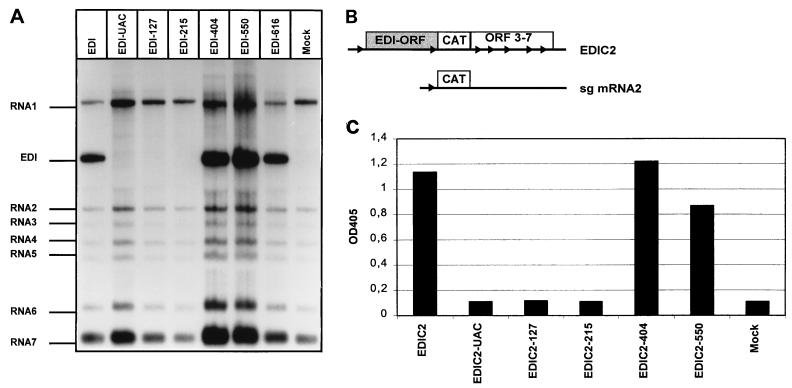

FIG. 2.

Analysis of the replication of EDI-ORF frameshift mutants. (A) RNA from pEDI and EDI-ORF frameshift mutants was transfected into EAV-infected BHK-21 cells. Virus was harvested at 16 h posttransfection and passaged twice. P2 RNA was isolated at 12 h p.i. and subjected to gel electrophoresis and hybridization with an oligonucleotide recognizing the 3′ ends of all viral mRNAs. The mock lane represents cells that were EAV infected but not transfected. (B) Schematic representation of the EDIC2 replicon. The EDI-ORF and position of the CAT gene are indicated. The leader and sg mRNA body TRSs are indicated by arrowheads. (C) Analysis of CAT reporter gene expression from EDIC2 and derivatives. RNA from EDIC2 and EDIC2-derived EDI-ORF frameshift mutants was transfected into EAV-infected BHK-21 cells. At 12 h posttransfection, cells were lysed and tested for CAT expression by CAT ELISA. OD405, optical density at 405 nm.

RNA transcription and transfection.

Plasmid DNA of constructs pEAV030, pEDI, and derivatives thereof was linearized with XhoI, extracted with phenol-chloroform, and ethanol precipitated. RNA was synthesized in vitro by using T7 RNA polymerase as described elsewhere (43). Transfection of in vitro-generated pEDI-derived RNA into EAV-infected cells and cotransfection of EDI RNA with in vitro-generated EAV030 RNA has been described previously (43).

Isolation and analysis of viral RNA.

Intracellular RNA was isolated at 12 h post infection (p.i.) by using Trizol (Life Technologies) and then subjected to isopropanol precipitation. Denaturing RNA electrophoresis was carried out in 1% agarose gels containing 10 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) and 2.2 M formaldehyde. Gels were dried and hybridized with an oligonucleotide recognizing the 3′ end of all viral RNAs as described by Meinkoth and Wahl (40).

CAT ELISA.

CAT expression was determined by using a Boehringer Mannheim CAT enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer. At 12 h posttransfection, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and lysed with the CAT ELISA lysis buffer supplied with the kit.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

For analysis of the EDI-ORF region of EDI RNA and its derivatives, reverse transcription was primed using oligonucleotide E158 (5′-CAGGTCTGTAACGCGCACCTCGTG-3′; negative sense; EDI nt 2751 to 2775). Subsequently, PCR was carried out by using an XL-PCR kit (Perkin-Elmer) according to the instructions of the manufacturer, using as primers oligonucleotides specific for the fusion site of the first and second EDI segments (E377; 5′-GGCCTTCATACCTGAAGGG-3′; positive sense; EDI nt 1049 to 1068) and E158. For sequence analysis of the sg mRNA7 leader-body junction and the genomic leader sequence, cDNA was generated by using oligonucleotide E154 (5′-TTGGTTCCTGGGTGGCTAATAACTACTT-3′; negative sense; EAV genome nt 12680 to 12707). cDNA was amplified by PCR using oligonucleotides E157 (5′-CTTGTGGGCCCCTCTCGGTAAATCC-3′; positive sense; EAV genome positions 63 to 89) and either E160 (CTTACGGCCCTGCTGGAGGCGCAAC-3′; negative sense; EAV genome position 12623 to 12646) for the sg mRNA7 leader-body junction or E274 (5′-CCAGTAGCGGAGAAGGTTGC-3′; negative sense; EAV genome positions 228 to 247) for the genomic leader sequence. The PCR fragments were sequenced using oligonucleotide E157.

Titration of recombinant viruses.

Virus harvests were titrated in plaque assays, which were performed on 106 BHK-21 cells in 35-mm-diameter cell culture dishes. Cells were infected with dilutions of the passage 1 (P1) virus harvest obtained at 12 or 24 h posttransfection, as indicated in the appropriate figure legend. After 1 h of infection, a 1% agarose overlay in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 2% fetal calf serum was applied to the cells. The cells were then incubated at 39.5°C until plaques became visible (after 2 to 3 days). Plaque assays were fixed with 10% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline and stained with a 1% solution of crystal violet (Merck) in 50% ethanol. Alternatively, virus was isolated from individual plaques and used to infect a fresh monolayer of cells, from which intracellular RNA was isolated at 12 h p.i.

Immunofluorescence assays.

Immunofluorescence assays were performed essentially as described before (57). A CAT-specific rabbit antiserum was obtained from 5 Prime → 3 Prime Inc. and used at a 1:500 dilution. The EAV nsp3-specific rabbit antiserum has been described elsewhere (46). As secondary antibody, a Cy3-coupled donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) was used.

RESULTS

Translation of the 5′-terminal half of EDI-ORF appears to be required for efficient EDI RNA propagation.

We have previously reported the construction of pEDI, a full-length cDNA copy of the EAV DI-b genome from which replication-competent EDI RNA can be transcribed in vitro (Fig. 1) (43). As described in the introduction, the in-frame fusion of the three EAV genome segments that constitute the EDI sequence has resulted in the presence of a truncated replicase ORF, EDI-ORF, that starts at the natural ORF1a translation initiation codon (nt 225) and ends at the ORF1b termination codon (nt 2576 of the EDI sequence; nt 9749 of the EAV genome). EDI-ORF encodes a truncated replicase fusion protein of 784 aa, consisting of nsp1, two segments of nsp2, the C-terminal part of nsp10, nsp11, and nsp12 (43). Since the sequences upstream of the truncated EDI-ORF are identical to the 5′ nontranslated region of the EAV genome, we assumed that EDI-ORF can be translated from EDI RNA. This was confirmed by in vitro translation of pEDI transcripts in a reticulocyte lysate (data not shown). In this experiment, we also observed that nsp1 autoproteolytically cleaved itself from the remainder of the EDI-protein. We expect that in cells infected with EAV and transfected with EDI RNA, the EDI-protein is further processed in trans at the nsp10/11 and nsp11/12 sites by the nsp4 serine protease encoded by the helper virus (55, 62).

In view of the presence (and, in some cases, proven importance) of a large ORF in many natural nidovirus DI RNAs, we have investigated the significance of the EDI-ORF in EAV DI RNA propagation. To this end, we engineered a set of pEDI derivatives containing C-terminally truncated EDI-ORFs of different sizes. By using a number of convenient restriction sites, we introduced frameshift mutations into the EDI-ORF. Furthermore, in construct pEDI-UAC, the EDI-ORF translation initiation codon was mutated. In the context of the full-length EAV genome, the latter mutation was recently shown not to affect the RNA signals required for genome replication and sg mRNA synthesis (M. A. Tijms, L. C. van Dinten, A. E. Gorbalenya, and E. J. Snijder, unpublished data). The first AUG initiation codon downstream of the mutations in pEDI-UAC (nt 304) is in the +1 reading frame with respect to the EDI-ORF and encodes a protein of only 35 aa. An overview of the EDI-ORF mutants, including the position of the termination codon and the size of the truncated EDI-ORF, is presented in Table 1.

In vitro-transcribed RNA of the EDI-ORF mutants was transfected into EAV-infected BHK-21 cells, and standard (undiluted) virus passaging experiments (43) were performed. Intracellular RNA was isolated after P2 and analyzed by denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis and hybridization (Fig. 2A). The positive control, EDI RNA containing the full-length EDI-ORF (784 aa), was replicated and passaged efficiently. Remarkably, RNA derived from the EDI-UAC translation initiation codon mutant could not be detected in P2 RNA samples. Likewise, the EDI-ORF mutants containing a relatively short reading frame (EDI-127 and EDI-215) could not be rescued. We also analyzed P2 RNA by EDI-specific RT-PCR (Fig. 3A). Again, the positive control (EDI RNA) was easily detected in P2, but EDI-UAC-, EDI-127-, and EDI-215-specific RT-PCR products were not observed. In contrast, the EDI-ORF mutants with a longer reading frame (EDI-404, EDI-550, and EDI-616) were rescued efficiently (Fig. 2) and were readily detected with RT-PCR (Fig. 3A). These results suggest that translation of either the 5′-terminal half of EDI-ORF or the N-terminal part of the EDI-protein is required for passaging of this EAV DI RNA.

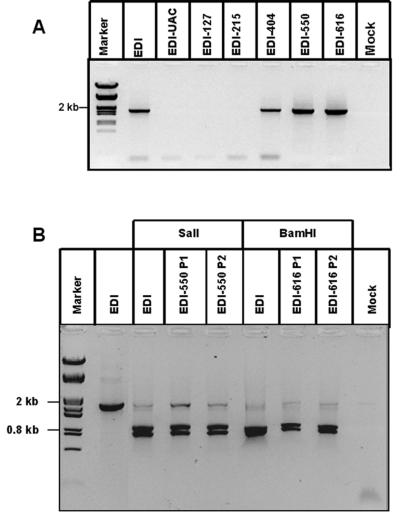

FIG. 3.

Analysis of in-frame escape mutants. (A) P2 RNA derived from EDI and all EDI-ORF frameshift mutants was analyzed by EDI-RNA-specific RT-PCR (see Materials and Methods). Subsequent sequence analysis of RT-PCR products revealed that in the efficiently rescued EDI-ORF mutants (EDI-404, EDI-550, and EDI-616), the region containing the frameshift mutation has been replaced by wt sequences. (B) P1 and P2 RNA derived from EDI, EDI-505, and EDI-616 was analyzed by RT-PCR and assayed by digestion with the restriction enzyme for which the site has been removed during the generation of the corresponding frameshift mutation (SalI and BamHI for EDI-505 and EDI-616, respectively). Almost complete digestion of the RT-PCR products was observed for both P1 and P2 RNA of EDI-505 and EDI-616, indicating that the restriction site was restored early in our passaging experiment. The mock RNA sample was derived from EAV-infected but untransfected cells.

To investigate whether the EDI mutants with the relatively short reading frames were replicated in transfected cells (P0), a sensitive and convenient assay was required. Previously, we have shown that the CAT reporter gene, under the control of the sg mRNA2 TRS, can be used to monitor EDI replication and sg mRNA synthesis (construct pEDIC2 [43]). Hence, we now inserted the CAT gene at the same position in all EDI-ORF mutants except EDI-616 (Fig. 2B). RNA derived from these constructs was transfected into EAV-infected BHK-21 cells. At 12 h posttransfection, cells were lysed and the amount of CAT was determined by CAT ELISA. In cells transfected with the original EDIC2 RNA, containing the complete 784-codon reading frame, or with EDI-ORF mutants EDIC2-404 and EDIC2-550, CAT expression was readily detected (Fig. 2C). In contrast, EDIC2-UAC, EDIC2-127, and EDIC2-215 failed to express the CAT reporter gene in transfected cells (Fig. 2C). This strongly suggested that the frameshift mutants with the shorter reading frames (EDIC2-UAC, EDIC2-127, and EDIC2-215) were not replicated and indicated that the EDI-ORF and/or its translation plays a crucial role in the replication of EDI RNA and its derivatives.

Detection of in-frame escape mutants.

To analyze whether escape mutants containing a restored EDI-ORF were generated, intracellular P2 RNA of all EDI-ORF mutants was analyzed. The region corresponding to the EDI-ORF was amplified by using an EDI RNA-specific RT-PCR. PCR products were analyzed on agarose gel (Fig. 3A), and the region containing the frameshift mutation was sequenced for each of the mutants that yielded a product. To our surprise, in all EDI-ORF frameshift mutants that were rescued efficiently (EDI-404, EDI-550, and EDI-616), the restriction site used to generate the frameshift mutation had been repaired and the flanking sequences in this region were completely identical to the wild-type (wt) EAV sequence. The control RT-PCR on RNA from EAV-infected cells that had not been transfected with an EDI construct did not yield a product (Fig. 3A, mock lane). This proved the DI RNA specificity of the PCR and excluded the possibility that the PCR products and wt sequences were derived from amplification of the corresponding region of the helper virus genome. The result for all three mutants implied removal of the four nucleotides that had been inserted into the pEDI sequence (by polishing of sticky ends) after digestion of the corresponding restriction sites. This strongly suggested that these mutants had undergone homologous recombination with the helper virus genome, thereby repairing the frameshift mutation and restoring the full-length EDI-ORF (see also Discussion). Furthermore, this underlines the importance of the EDI-ORF since the recombinant EDI RNAs with a full-length ORF were selectively amplified during passaging at the expense of the original DI RNAs carrying frameshift mutations.

To investigate at which stage recombination had occurred, intracellular P1 and P2 RNA was isolated during EDI-550 and EDI-616 passaging experiments and used for RT-PCR as described above. Subsequently, the RT-PCR products were digested with the restriction enzyme for which the site had been removed during generation of the corresponding EDI-ORF mutant (SalI and BamHI, respectively), and the digestion products were analyzed on agarose gel (Fig. 3B). Both the P1 and P2 RT-PCR products were almost completely digested by the restriction enzyme, indicating that the wild-type EDI sequence had been restored. This experiment demonstrated that recombination had occurred very early in the passaging experiment, possibly during P0.

An approximately 100-fold difference in the RNA recombination rate in the 5′- and 3′-proximal regions of EAV030 and EDI RNA.

The results obtained with our EDI-ORF mutants strongly suggested that efficient homologous recombination between the helper virus genome and EDI RNA occurred during our transfection and passaging experiments. Recombination in the ORF1b region (EDI-404, EDI-550, and EDI-616), however, appeared to be much more efficient than in the ORF1a region (EDI-UAC, EDI-127, and EDI-215) of the DI RNA. This suggested that the rates of recombination may vary in different regions of the genome. To characterize this phenomenon in more detail, we investigated the relative rates of RNA recombination in the 3′- and 5′-proximal regions of the EAV genome. We designed recombination assays in which we made use of two previously described noninfectious but replication competent full-length cDNA clones, mutants L3 and B3 (64). In these constructs, either the leader TRS (L3 mutant [Fig. 4A]) or the RNA7 body TRS (B3 mutant [Fig. 4B]) has been changed from 5′-UCAAC-3′ to 5′-UGAAG-3′. Either of these mutations renders the full-length clone noninfectious due to defects in sg RNA synthesis and structural protein expression: in mutant L3 sg mRNA synthesis is completely abolished, whereas mutant B3 does not generate sg mRNA7, which encodes the viral N protein. However, replicase expression and genome replication of both the L3 and B3 mutants occurs with wt efficiency (64). Thus, these mutant full-length RNAs could be used to express the replicase required for their own amplification and that of cotransfected EDI RNA. In addition, they could serve as a potential partner in RNA recombination, which would yield an infectious EAV genome when the region containing the L3 or B3 TRS mutation would be exchanged for the corresponding region of an EDI RNA containing a wt TRS at the homologous site.

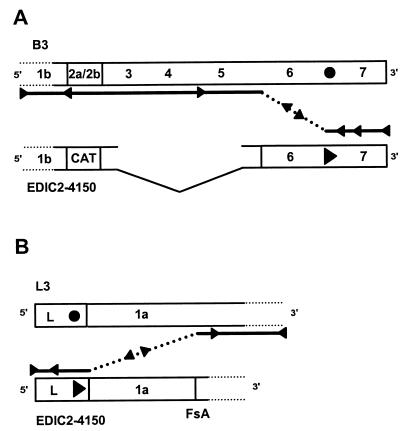

FIG. 4.

Schematic representation of possible homologous recombination events between mutant B3 or L3 and EDIC2-4150. Arrowheads represent a wt 5′-UCAAC-3′ TRS; circles represent a nonfunctional mutant 5′-UGAAG-3′ TRS. The lines represent the nascent minus- or plus-strand transcript. The regions in which a recombination event must occur in order to generate a wt infectious genome are indicated with a dashed line. (A) Recombination between mutant B3 and EDIC2-4150 results in a wt genome when a crossover occurs in the region between the RNA7 TRS (EDI nt 5649 to 5653) and the 3′ border of the deletion in EDIC-4150 (EDI nt 5033). (B) Recombination between mutant L3 and EDIC2-4150 results in a wt genome when a crossover takes place in the region between the leader (L) TRS (nt 211) and the first EDI fusion site (FsA; nt 1054 [43]).

To analyze the rate of recombination in the 3′-proximal region of the EAV genome, mutant B3 was cotransfected with EDIC2-4150 RNA (43). This EDI derivative contained the CAT reporter gene at the position normally occupied by ORF2b. In addition, EDIC2-4150 contains a deletion ranging from the 3′ end of ORF3 (EAV nt 10723) to the 3′ end of ORF5 (EAV nt 11636). All other sequences (including the leader TRS) were identical to those of EDI. CAT expression was under the control of the RNA2 TRS and was used to determine the number of double-transfected cells in an immunofluorescence assay, since only cells containing both RNAs could express the reporter gene. Furthermore, EDIC2-4150 contained the wt RNA7 body TRS, and hence a single recombination with the B3 RNA in the 616-nt region between the 3′ border of the deletion and the RNA7 TRS of EDIC2-4150 could yield a full-length, infectious EAV genome (Fig. 4B). Likewise, the rate of recombination in the 5′-proximal region of the genome was analyzed by cotransfection of the L3 mutant and EDIC2-4150. In this case (Fig. 4A), a single recombination event occurring in the 846-nt region between the leader TRS and the fusion of the first and second EDI segments of EDIC2-4150 (fusion site A) could generate a full-length, infectious RNA molecule. In both recombination assays, recombinant genomes should be readily detected in an infectivity assay since they would be infectious, in contrast to their two parental RNA replicons.

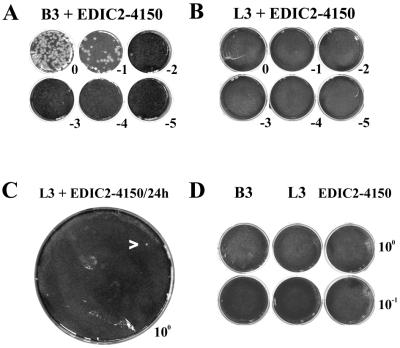

Medium from double-transfected cells was harvested at 12 h posttransfection (i.e., after a single EAV replication cycle), and the presence of infectious virus particles was determined by plaque assays (Fig. 5). Surprisingly, medium harvested from cotransfections of mutant B3 and EDIC2-4150 (Fig. 5A) contained substantially more recombinant virus particles than medium harvested from cotransfections of mutant L3 and EDIC2-4150 (Fig. 5B). Only when a large amount of a 24-h harvest of the L3/EDIC2-4150 double transfection was used, a single plaque was observed (Fig. 5C). Upon titration of the 24-h harvests from single transfections of mutant B3, mutant L3, or EDIC2-4150, no plaques were detected (Fig. 5D), indicating that reversion of the L3 and B3 TRS mutations did not occur during the 24-h incubation period.

FIG. 5.

Titration of recombinant viruses. Medium from cotransfections of the B3 mutant (A) or L3 mutant (B) and EDIC2-4150 was harvested at 12 h posttransfection and titrated in plaque assays. Dilutions ranged from undiluted (upper left well) to 10−5 (lower right well). (C) Undiluted medium from a cotransfection of mutant L3 and EDIC2-4150, harvested at 24 h posttransfection, was used for a large-scale plaque assay. The single plaque observed is indicated with an arrow. (D) Control experiment. Medium isolated from single transfections of either the B3 mutant, the L3 mutant, or EDIC-4150 was harvested at 24 h posttransfection and used in a plaque assay. No plaques were detected.

To estimate the efficiency of double transfection in both experiments, immunofluorescence assays were performed with a CAT-specific antiserum. CAT expression implied that the transfected DI RNA was replicated and transcribed by the replicase of the cotransfected L3 or B3 mutant full-length genome. Similar transfection efficiencies (±10%) were observed for both double transfections (data not shown). This allowed us to compare the relative recombination rates in the 3′- and 5′-terminal regions of the genome by determining the number of infectious recombinant viruses released into the medium. The mean number of PFU from two independent plaque assays was corrected for the length of the region in which a crossover had to occur to restore the infectivity of the mutant full-length genome (616 and 846 nt for recombination in the 3′- and 5′-proximal regions, respectively [Fig. 4]). In this manner, we estimated that recombination in the 5′-proximal region of the genome was at least 100-fold less efficient than recombination in the 3′-terminal region.

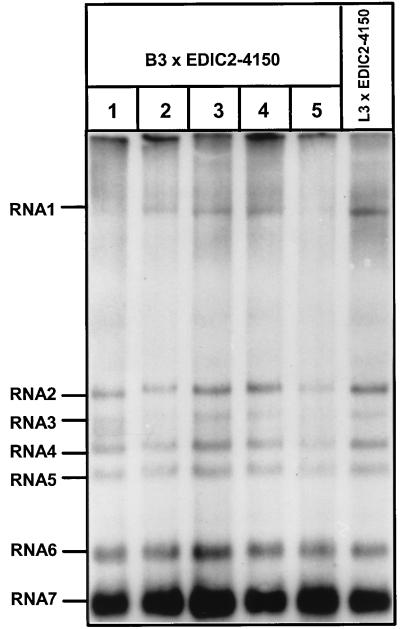

The plaque titrations of medium from B3/EDIC2-4150 double transfections were linear, which indicates that the plaques were derived from single virus particles and not, e.g., from a mixed population of DI particles and virions containing the full-length mutant genome. To confirm that the observed plaques were indeed derived from true recombinants, virus was isolated from individual plaques and used to infect a fresh dish of BHK-21 cells. Subsequently, intracellular RNA was isolated and analyzed by gel electrophoresis and hybridization with an oligonucleotide recognizing all viral mRNAs (Fig. 6). From this experiment we concluded that the DI RNA was not present in the virus isolated from the plaques. Furthermore, RT-PCRs specific for the sg mRNA7 leader-body junction and the genomic leader sequence were performed. These PCR products were sequenced and found to contain exclusively the wt 5′-UCAAC-3′ TRS at the sg mRNA7 leader-body junction and in the genomic leader (data not shown). This again confirmed that true recombinant genomes had been generated by removal of the TRS mutations from the L3 and B3 mutant RNAs.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of plaque-purified recombinant viruses. Virus isolated from individual plaques (Fig. 5) was used to infect a monolayer of BHK-21 cells. At 12 h p.i., viral RNA was isolated and subjected to gel electrophoresis and hybridization with an oligonucleotide recognizing the 3′ ends of all viral RNAs. In none of the recombinant virus preparations was EDIC2-4150 RNA detected, indicating that the plaque was derived from a true recombinant virus and not from a pseudotype virus containing both EDIC2-4150 RNA and the L3 or B3 mutant genome.

DISCUSSION

Frameshift mutations in EDI-ORF either block replication or are rapidly removed.

In this paper we demonstrate the importance of the EDI-ORF for the propagation of EDI RNA. Frameshift mutations in this truncated replicase ORF were found either to block DI RNA propagation completely or to be removed within one passage, probably by homologous recombination with the helper virus genome. At first, our data suggested that EDI mutants carrying a relatively short EDI-ORF (215 codons or less) could not be rescued by the helper virus, whereas EDI derivatives containing a larger ORF appeared to be propagated efficiently (Fig. 2A). However, our analysis of the latter EDI-ORF mutants after one or two virus passages revealed that the originally transfected mutant replicon was no longer present. Instead, the full-length EDI-ORF had been restored by removal of the frameshift-inducing mutations. The restriction site used to create the truncated EDI-ORF had been repaired, and not a single nucleotide difference with the genomic sequence in this region could be detected. In principle, errors made by the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase during the replication of EDI-ORF frameshift mutants, followed by selection of specific mutations, could have resulted in restoration of the EDI-ORF. However, restoration of the EDI-ORF does not require reversion to the exact wt sequence, as it was observed for each of the three mutants. Thus, the simultaneous elimination of all four mutations in these constructs strongly suggested that these in-frame escape mutants were derived not from reversion due to RNA polymerase errors but rather from homologous recombination with the helper virus genome.

The experiments presented in Fig. 2C suggest that the inability of EDI derivatives with a short EDI-ORF (EDI-UAC, EDI-127, and EDI-215) to be rescued by the helper virus resulted from their poor replication competence and not from, e.g., an encapsidation defect of these DI RNAs. Formally, we cannot exclude the possibility that these specific mutations disrupted only sg mRNA2 synthesis, which is required for the expression of the CAT reporter gene. However, the EDI frameshift mutants with larger reading frames, which differ from the three CAT-negative constructs by only a few nucleotides, replicated efficiently in P0 and expressed CAT to similar levels as the wt EDIC2 replicon. It is possible that the EDI mutants carrying longer reading frames replicate more efficiently, thereby increasing the possibilities for homologous recombination with the helper virus genome by polymerase template switching. Alternatively, all EDI-ORF mutants might replicate much more poorly than the wt EDI RNA, and the outcome of the passaging experiments might reflect differences in the frequency of recombination events that convert the EDI-ORF mutants to a wt EDI RNA. In this case, the difference in recombination properties between the EDI-ORF mutants with a small ORF (which require a recombination event in the ORF1a region of the DI RNA for repair of the ORF) and those with a large ORF (requiring a recombination event in the ORF1b region) might reflect certain characteristics of the ORF1a and ORF1b regions of the DI RNA.

Theoretically, the length of the potential crossover region between genome and EDI RNA might have accounted for the differences between EDI mutants with short and long ORFs. However, the crossover regions in EDI-UAC, EDI-127, and EDI-215 (the group of nonpropagated EDI-ORF mutants) are 827, 436, and 195 nt, respectively, while for the efficiently propagated EDI-ORF mutants EDI-404, EDI-550, and EDI-616 these regions are 36, 466, and 619 nt in length. Thus, it is clear that this parameter does not explain the different outcomes of the passaging experiments with these two groups of EDI-ORF mutants.

Our data concerning the recombination frequencies in the 5′- and 3′-terminal regions of the EAV genome (see below) indicate that recombination close to the 5′ end of the genome may be much less efficient than that in the 3′-terminal region. Information on the recombination frequency in each of the genome segments that forms the (potential) crossover region for one of the EDI-ORF mutants is currently not available. If the recombination frequency of the arterivirus genome were indeed found to decrease in the 3′-to-5′ direction, this phenomenon might account, at least in part, for the differences observed between the two groups of EDI-ORF mutants. For mutants EDI-UAC, EDI-127, and EDI-215, recombination has to occur in the 5′-proximal EDI segment, for which the rate of recombination with a full-length genome was found to be drastically reduced (Fig. 4 and 5).

The importance of the EDI-ORF in EDI RNA replication.

As proposed by de Groot et al. (10) and supported by van der Most et al. (60), translation of the ORF in coronavirus DI RNAs, which often spans almost the entire DI genome, could enhance DI RNA stability. Consequently, the fitness of DI RNAs with an interrupted or truncated ORF might be reduced, explaining why these replicons are outcompeted by recombinant DI RNAs with a restored ORF. In the case of EDI, the ORF covers only half of the RNA molecule (43). However, it is interesting to note that in the region downstream of the truncated replicase ORF, in contrast to other nidovirus DI RNAs, EDI has retained the genomic 3′-terminal region that includes the cis-acting sequences required for the synthesis of all sg mRNAs. It has been shown that sg mRNA transcription by the helper virus replicase does indeed take place from the EDI RNA template (43). Therefore, we speculate that the nontranslated 3′-terminal part of the EDI genome might be stabilized by sg mRNA transcription rather than by translation.

An alternative explanation for the requirement for a DI ORF is that one or more of the proteins it encodes is needed in cis for the replication of the DI RNA. Conflicting data concerning this issue have been published for coronaviruses. Chang and Brian (8) described that N protein-specific sequences are required for the replication of bovine coronavirus DI RNAs. In contrast, Liao and Lai (35) and van der Most et al. (60) have reported that a cis-acting viral protein is not required for the replication of mouse hepatitis coronavirus (MHV) DI RNAs. The analysis of our mutant EDI-404, which was rescued efficiently, demonstrated that the nsp11 and nsp12 sequences encoded by the EDI-ORF are not essential. Furthermore, we have previously shown that an EDI derivative that lacks the region encoding the C-terminal part of nsp1 and the nsp2 and nsp10 segments of the EDI-protein (construct pEDIC2-0613) was replicated efficiently (43). Therefore, if part of the EDI-protein would be required in cis for the replication of EDI RNA, this region would have to be restricted to the N-terminal part of nsp1. It was recently shown that the entire nsp1 protein is dispensable for EAV genome replication and is in fact an essential factor for sg mRNA synthesis that can act in trans (Tijms et al., unpublished). Thus, we consider it highly unlikely that any part of the EDI-protein is required for the replication of EDI RNA.

Variable rates of recombination in the 5′- and 3′-proximal regions of the EAV genome.

Frequent homologous RNA recombination is a remarkable feature of RNA viruses in general (5, 6, 21, 24, 28, 44, 45) and of coronaviruses in particular, especially in view of their genome size and unique sg RNA transcription mechanism (31, 37; for reviews, see references 4 and 29). Coronavirus recombination has been studied extensively. By using recombination assays based on temperature-sensitive mutants, the recombination frequency for the entire MHV genome was estimated to be approximately 25% during one replication cycle (2, 19). The development of a targeted recombination approach (25, 39, 59) allowed the introduction of specific mutations in the large coronavirus genome and has become an important tool for studying coronavirus replication.

For the arterivirus lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV), homologous genetic recombination was observed in mice infected with two distinct LDV strains (34). This allowed Li and Plagemann (34) to estimate the recombination frequency in a 1,276-nt region from the 3′-proximal region of the LDV genome at approximately 5% during 1 day of replication in mice. Furthermore, recombination in tissue culture was observed between two North American strains of the arterivirus porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (69). In this study, the frequency of recombination was estimated to be 2 to 10% in a 1,182-nt structural protein-coding region.

In this study, we compared the relative rates of recombination in the 5′- and 3′-proximal regions of an EAV DI RNA and mutant full-length genomes. Our assays used previously characterized lethal mutations in the EAV leader and RNA7 body TRSs, which could be removed by a single recombination event with the DI RNA in a specific, restricted region of the genome, thereby restoring infectivity of the full-length genome. In addition to these recombinants, pseudotype virions could have been produced, containing both the DI RNA and the mutant genome, which might complement each other at the level of protein expression. However, our plaque assays and the analysis of the viral RNA isolated from individual plaques revealed that pseudotype virions were not generated. Furthermore, by partial sequence analysis of the genomes of these viruses, it was confirmed that in these recombinants the wt TRS sequence had been restored in either leader or RNA7 body. In theory, this could be the result of a double reversion due to polymerase errors. However, single transfections of the B3 and L3 mutant full-length RNAs showed that such revertants were not generated within the 24 h incubation period, although we cannot formally exclude the possibility that the reversion frequency might be influenced by the cotransfection of a DI RNA.

For the coronavirus MHV, it has been shown that the recombination frequency varies throughout the genome (18, 19). The predicted recombination frequency in the spike protein gene was three times higher than that in the replicase gene (18). Interestingly, our data showed that the relative rates of recombination in different regions of the EAV genome can also vary. The relative recombination frequency in the 5′-proximal region of the genome was found to be approximately 100-fold lower than that in the 3′-terminal region. It has been proposed that the high rate of recombination in coronaviruses might be linked directly to the discontinuous sg mRNA transcription mechanism (1, 22, 29, 31). Based on that assumption, we can envision two explanations for the difference in recombination efficiency between the 5′- and 3′-proximal regions of the EAV genome. First, in infected cells, the number of RNA molecules carrying homologous sequences is much higher for the 3′-proximal sequences due to the abundant transcription of sg plus- and minus-strand RNAs. EDI-derived sg mRNAs could act as potential donor and acceptor RNA molecules for recombination with the 3′-proximal region of the mutant full-length genome. Since high concentrations of donor and acceptor molecules generally increase the chance of a recombination event (24), the presence of the sg RNA molecules could enhance the recombination efficiency in the 3′-proximal part of the genome and EDI RNA. In this case the recombination frequency in the structural gene region should increase in the 5′ → 3′ direction and reflect the concentration gradient of the sg mRNAs. Furthermore, recombination events between the DI RNA and the mutant genome will generate a recombinant wt genome that produces high levels of wt sg mRNAs (in this case, sg mRNAs containing the wt RNA7 TRS). This again increases the concentration of RNA molecules containing wt 3′-terminal sequences and may thus promote RNA recombination in this part of the genome.

Alternatively, the high rate of recombination in the 3′ end of the genome might be an even more direct result of the discontinuous nature of nidovirus sg RNA transcription. It has been proposed that minus-strand RNA synthesis is attenuated at body TRSs, a step which should be followed by base pairing with the leader TRS and reinitiation of minus-strand synthesis to add the antileader sequence (26, 51, 64, 65). In a similar manner, attenuation of minus-strand synthesis might facilitate RNA recombination. The polymerase complex could reinitiate transcription of the nascent minus strand at the same body TRS of a different template, and thus in our case continue to transcribe a recombinant full-length genome after initiating minus strand RNA synthesis from an EDI template (Fig. 4). At the 5′ end of the EAV genome, minus-strand synthesis might be attenuated much less frequently, which could explain the much lower rate of recombination in this region. Finally, we cannot exclude that the mutated TRS region of the EAV leader has special characteristics that could explain a low recombination frequency. Future analysis of the recombination behavior of other silent markers near the 5′ end of the genome may reveal a higher recombination rate.

Our studies with the EDI-ORF mutants showed that recombination can take place in the ORF1b region of the genome. Also this region is not used for the transcription of sg RNAs, and thus attenuation of minus-strand synthesis would not be expected to occur with a high frequency. Unfortunately, due to the nature of the passaging experiments with the EDI-ORF mutants, the recombination frequencies in ORF1b could not be easily estimated or compared with those in 5′-proximal region. It will be very interesting to address the question of whether the low recombination efficiency in the genomic 5′ end is a property specifically associated with this region. Alternatively, the recombination efficiency may gradually decline from the 3′ to the 5′ end of the EAV genome. For the design of recombination assays to investigate this issue, DI RNAs with large deletions in the replicase gene (like EDI) will not be very useful. Instead, we hope to identify selectable marker mutations throughout the replicase gene, e.g., mutations giving rise to amino acid substitutions that induce a temperature-sensitive phenotype, and use these to analyze recombination upon cotransfection of two mutant full-length RNA transcripts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marieke Tijms and Sasha Pasternak for helpful comments and discussions. We are grateful to Guido van Marle and Jessika Dobbe for the EAV mutant clones L3 and B3 and to Marieke Tijms for the PCR product containing the ORF1a translation initiation codon mutant.

R.M. was supported by grant 700-31-020 from the Council for Chemical Sciences of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (CW-NWO).

REFERENCES

- 1.Baric R S, Fu K, Schaad M C, Stohlman S A. Establishing a genetic recombination map for murine coronavirus strain A59 complementation groups. Virology. 1990;177:646–656. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90530-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baric R S, Schaad M C, Wei T, Fu K S, Lum K, Shieh C, Stohlman S A. Murine coronavirus temperature sensitive mutants. Adv Exp Biol Med. 1990;276:349–356. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5823-7_47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baric R S, Stohlman S A, Lai M M C. Characterization of replicative intermediate RNA of mouse hepatitis virus: presence of leader RNA sequences on nascent chains. J Virol. 1983;48:633–640. doi: 10.1128/jvi.48.3.633-640.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brian D A, Spaan W J M. Recombination and coronavirus defective interfering RNAs. Semin Virol. 1997;8:101–111. doi: 10.1006/smvy.1997.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bujarski J J, Dzianott A M. Generation and analysis of nonhomologous RNA-RNA recombinants in brome mosaic virus: sequence complementarities at crossover sites. J Virol. 1991;65:4153–4159. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4153-4159.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bujarski J J, Kaesberg P. Genetic recombination between RNA components of a multipartite plant virus. Nature. 1986;321:528–531. doi: 10.1038/321528a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavanagh D. Nidovirales: a new order comprising Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae. Arch Virol. 1997;142:629–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang R Y, Brian D A. cis requirement for N-specific protein sequence in bovine coronavirus defective interfering RNA replication. J Virol. 1996;70:2201–2207. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2201-2207.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang R Y, Hofmann M A, Sethna P B, Brian D A. A cis-acting function for the coronavirus leader in defective interfering RNA replication. J Virol. 1994;68:8223–8231. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8223-8231.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Groot R J, van der Most R G, Spaan W J M. The fitness of defective interfering murine coronavirus DI-a and its derivatives is decreased by nonsense and frameshift mutations. J Virol. 1992;66:5898–5905. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.5898-5905.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.den Boon J A, Kleijnen M F, Spaan W J M, Snijder E J. Equine arteritis virus subgenomic mRNA synthesis: analysis of leader-body junctions and replicative-form RNAs. J Virol. 1996;70:4291–4298. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4291-4298.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.den Boon J A, Snijder E J, Chirnside E D, de Vries A A F, Horzinek M C, Spaan W J M. Equine arteritis virus is not a togavirus but belongs to the coronaviruslike superfamily. J Virol. 1991;65:2910–2920. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.2910-2920.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.deVries A A F, Chirnside E D, Bredenbeek P J, Gravestein L A, Horzinek M C, Spaan W J M. All subgenomic mRNAs of equine arteritis virus contain a common leader sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3241–3247. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.11.3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.deVries A A F, Chirnside E D, Horzinek M C, Rottier P J M. Structural proteins of equine arteritis virus. J Virol. 1992;66:6294–6303. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6294-6303.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.deVries A A F, Horzinek M C, Rottier P J M, de Groot R J. The genome organization of the Nidovirales: similarities and differences between arteri-, toro-, and coronaviruses. Semin Virol. 1997;8:33–47. doi: 10.1006/smvy.1997.0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doll E R, Bryans J T, McCollum W H, Crowe M E W. Isolation of a filterable agent causing arteritis of horses and abortion by mares. Its differentiation from the equine abortion (influenza) virus. Cornell Vet. 1957;47:3–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fosmire J A, Hwang K, Makino S. Identification and characterization of a coronavirus packaging signal. J Virol. 1992;66:3522–3530. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3522-3530.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu K, Baric R S. Evidence for variable rates of recombination in the MHV genome. Virology. 1992;189:88–102. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90684-H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu K, Baric R S. Map locations of mouse hepatitis virus temperature-sensitive mutants: confirmation of variable rates of recombination. J Virol. 1994;68:7458–7466. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7458-7466.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izeta A, Smerdou C, Alonso S, Penzes Z, Mendez A, Plana-Duran J, Enjuanes L. Replication and packaging of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus-derived synthetic minigenomes. J Virol. 1999;73:1535–1545. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1535-1545.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarvis T C, Kirkegaard K. Poliovirus RNA recombination: mechanistic studies in the absence of selection. EMBO J. 1992;11:3135–3145. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keck J G, Stohlman S A, Soe L H, Makino S, Lai M M. Multiple recombination sites at the 5′-end of murine coronavirus RNA. Virology. 1987;156:331–341. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90413-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim Y N, Jeong Y S, Makino S. Analysis of cis-acting sequences essential for coronavirus defective interfering RNA replication. Virology. 1993;197:53–63. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirkegaard K, Baltimore D. The mechanism of RNA recombination in poliovirus. Cell. 1986;47:433–443. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90600-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koetzner C A, Parker M M, Ricard C S, Sturman L S, Masters P S. Repair and mutagenesis of the genome of a deletion mutant of the coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus by targeted RNA recombination. J Virol. 1992;66:1841–1848. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.1841-1848.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konings D A, Bredenbeek P J, Noten J F, Hogeweg P, Spaan W J M. Differential premature termination of transcription as a proposed mechanism for the regulation of coronavirus gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10849–10860. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kupfermann H, Thiel H J, Dubovi E J, Meyers G. Bovine viral diarrhea virus: characterization of a cytopathogenic defective interfering particle with two internal deletions. J Virol. 1996;70:8175–8181. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8175-8181.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai M M. RNA recombination in animal and plant viruses. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:61–79. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.61-79.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai M M C. Recombination in large RNA viruses: coronaviruses. Semin Virol. 1996;7:381–388. doi: 10.1006/smvy.1996.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai M M C, Baric R S, Brayton P R, Stohlman S A. Characterization of leader RNA sequences on the virion and mRNAs of mouse hepatitis virus, a cytoplasmic RNA virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3626–3630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.12.3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai M M C, Baric R S, Makino S, Keck J G, Egbert J, Leibowitz J L, Stohlman S A. Recombination between nonsegmented RNA genomes of murine coronaviruses. J Virol. 1985;56:449–456. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.2.449-456.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai M M C, Cavanagh D. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res. 1997;48:1–100. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levis R, Weiss B G, Tsiang M, Huang H V, Schlesinger S. Deletion mapping of Sindbis virus DI RNAs derived from cDNAs defines the sequences essential for replication and packaging. Cell. 1986;44:137–145. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li K, Plagemann P G W. High-frequency homologous genetic recombination of an arterivirus, lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus, in mice and evolution of neuropathogenic variants. Virology. 1999;258:73–83. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao C L, Lai M M C. A cis-acting viral protein is not required for the replication of a coronavirus defective-interfering RNA. Virology. 1995;209:428–436. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin Y J, Lai M M C. Deletion mapping of a mouse hepatitis virus defective interfering RNA reveals the requirement of an internal and discontiguous sequence for replication. J Virol. 1993;67:6110–6118. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6110-6118.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Makino S, Keck J G, Stohlman S A, Lai M M C. High-frequency RNA recombination of murine coronaviruses. J Virol. 1986;57:729–737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.3.729-737.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makino S, Shieh C K, Soe L H, Baker S C, Lai M M C. Primary structure and translation of a defective interfering RNA of murine coronavirus. Virology. 1988;166:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90526-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masters P S. Reverse genetics of the largest RNA viruses. Adv Virus Res. 1999;53:245–264. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60351-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meinkoth J, Wahl G. Hybridization of nucleic acids immobilized on solid supports. Anal Biochem. 1984;138:267–284. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90808-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendez A, Smerdou C, Izeta A, Gebauer F, Enjuanes L. Molecular characterization of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus defective interfering genomes: packaging and heterogeneity. Virology. 1996;217:495–507. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyers G, Thiel H-J, Rumenapf T. Classical swine fever virus: recovery of infectious viruses from cDNA constructs and generation of recombinant cytopathogenic defective interfering particles. J Virol. 1996;70:1588–1595. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1588-1595.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Molenkamp R, Rozier B C D, Greve S, Spaan W J M, Snijder E J. Isolation and characterization of an arterivirus defective interfering RNA genome. J Virol. 2000;74:3156–3165. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3156-3165.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagy P D, Bujarski J J. Genetic recombination in brome mosaic virus: effect of sequence and replication of RNA on accumulation of recombinants. J Virol. 1992;66:6824–6828. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6824-6828.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagy P D, Bujarski J J. Targeting the site of RNA-RNA recombination in brome mosaic virus with antisense sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6390–6394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pedersen K W, van der Meer Y, Roos N, Snijder E J. Open reading frame 1a-encoded subunits of the arterivirus replicase induce endoplasmic reticulum-derived double-membrane vesicles which carry the viral replication complex. J Virol. 1999;73:2016–2026. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2016-2026.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Penzes Z, Tibbles K W, Shaw K, Britton P, Brown T D K, Cavanagh D. Characterization of a replicating and packaged defective RNA of avian coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus. Virology. 1994;203:286–293. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Penzes Z, Wroe C, Brown T D K, Britton P, Cavanagh D. Replication and packaging of coronavirus infectious bronchitus virus defective RNAs lacking a long open reading frame. J Virol. 1996;70:8660–8668. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8660-8668.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pogany J, Romero J, Bujarski J J. Effect of 5′ and 3′ terminal sequences, overall length, and coding capacity on the accumulation of defective RNAs associated with broad bean mottle bromovirus in planta. Virology. 1997;228:236–243. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sawicki S G, Sawicki D L. Coronaviruses use discontinuous extension for synthesis of subgenome-length negative strands. Adv Exp Biol Med. 1995;380:499–506. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1899-0_79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Snijder E J, Meulenberg J J M. The molecular biology of arteriviruses. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:961–979. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-5-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Snijder E J, van Tol H, Pedersen K W, Raamsman M J B, de Vries A A F. Identification of a novel structural protein of arteriviruses. J Virol. 1999;73:6335–6345. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6335-6345.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Snijder E J, Wassenaar A L M, Spaan W J M. Proteolytic processing of the replicase ORF1a protein of equine arteritis virus. J Virol. 1994;68:5755–5764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5755-5764.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Snijder E J, Wassenaar A L M, van Dinten L C, Spaan W J M, Gorbalenya A E. The arterivirus nsp4 protease is the prototype of a novel group of chymotrypsin-like enzymes, the 3C-like serine proteases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4864–4871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spaan W J M, Delius H, Skinner M, Armstrong J, Rottier P J M, Smeekens S, van der Zeijst B A M, Siddell S G. Coronavirus mRNA synthesis involves fusion of non-contiguous sequences. EMBO J. 1983;2:1839–1844. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01667.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Meer Y, van Tol H, Krijnse Locker J, Snijder E J. ORF1a-encoded replicase subunits are involved in the membrane association of the arterivirus replication complex. J Virol. 1998;72:6689–6698. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6689-6698.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van der Most R G, Bredenbeek P J, Spaan W J M. A domain at the 3′ end of the pol gene is essential for encapsidation of coronaviral defective interfering RNAs. J Virol. 1991;65:3219–3226. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3219-3226.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van der Most R G, Heijnen L, Spaan W J, de Groot R J. Homologous RNA recombination allows efficient introduction of site-specific mutations into the genome of coronavirus MHV-A59 via synthetic co-replicating RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3375–3381. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.13.3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Most R G, Luytjes W, Rutjes S, Spaan W J M. Translation but not the encoded sequence is essential for the efficient propagation of the defective interfering RNAs of the coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus. J Virol. 1995;69:3744–3751. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3744-3751.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Dinten L C, den Boon J A, Wassenaar A L M, Spaan W J M, Snijder E J. An infectious arterivirus cDNA clone: identification of a replicase point mutation which abolishes discontinuous mRNA transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:991–996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Dinten L C, Rensen S, Spaan W J M, Gorbalenya A E, Snijder E J. Proteolytic processing of the ORF1b-encoded part of the arterivirus replicase is mediated by the nsp4 serine protease and is essential for virus replication. J Virol. 1999;73:2027–2037. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2027-2037.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Dinten L C, Wassenaar A L M, Gorbalenya A E, Spaan W J M, Snijder E J. Processing of the equine arteritis virus replicase ORF1b protein: identification of cleavage products containing the putative viral polymerase and helicase domains. J Virol. 1996;70:6625–6633. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6625-6633.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Marle G, Dobbe J C, Gultyaev A P, Luytjes W, Spaan W J M, Snijder E J. Arterivirus discontinuous mRNA transcription is guided by base-pairing between sense and antisense transcription-regulating sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12056–12061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Marle G, Luytjes W, van der Most R G, van der Straaten T, Spaan W J M. Regulation of coronavirus mRNA transcription. J Virol. 1995;69:7851–7856. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7851-7856.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wassenaar A L M, Spaan W J M, Gorbalenya A E, Snijder E J. Alternative proteolytic processing of the arterivirus ORF1a polyprotein: evidence that nsp2 acts as a cofactor for the nsp4 serine protease. J Virol. 1997;71:9313–9322. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9313-9322.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.White C L, Thomson M, Dimmock N J. Deletion analysis of a defective interfering Semliki Forest virus RNA genome defines a region in the nsp2 sequence that is required for efficient packaging of the genome into virus particles. J Virol. 1998;72:4320–4326. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4320-4326.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yeh T Y, Lin B Y, Chang Y C, Hsu Y H, Lin N S. A defective RNA associated with bamboo mosaic virus and the possible common mechanisms for RNA recombination in potexviruses. Virus Genes. 1999;18:121–128. doi: 10.1023/a:1008008400653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yuan S, Nelsen C J, Murtaugh M P, Schmitt B J, Faaberg K S. Recombination between North American strains of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virus Res. 1999;61:87–98. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(99)00029-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]