Abstract

Introduction

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is largely underutilized in the Southern United States. Given their community presence, pharmacists are well positioned to provide PrEP within rural, Southern regions. However, pharmacists’ readiness to prescribe PrEP in these communities remains unknown.

Objective

To determine the perceived feasibility and acceptability of prescribing PrEP by pharmacists in South Carolina (SC).

Methods

We distributed a 43-question online descriptive survey through the University of SC Kennedy Pharmacy Innovation Center’s listerv of licensed SC pharmacists. We assessed pharmacists’ comfort, knowledge, and readiness to provide PrEP.

Results

A total of 150 pharmacists responded to the survey. The majority were White (73%, n=110), female (62%, n=93), and non-Hispanic (83%, n=125). Pharmacists practiced in retail (25%, n=37), hospital (22%, n=33), independent (17%, n=25), community (13%, n=19), specialty (6%, n=9), and academic settings (3%, n=4); 11% (n=17) practiced in rural locales. Pharmacists viewed PrEP as both effective (97%, n=122/125) and beneficial (74% n=97/131) for their clients. Many pharmacists reported being ready (60% n=79/130) and willing (86% n=111/129) to prescribe PrEP, although over half (62% n=73/118) cited lack of PrEP knowledge as a barrier. Pharmacists described pharmacies as an appropriate location to prescribe PrEP (72% n=97/134).

Conclusions

Most SC pharmacists surveyed considered PrEP to be effective and beneficial for individuals who frequent their pharmacy and are willing to prescribe this therapy if statewide statutes allow. Many felt that pharmacies are an appropriate location to prescribe PrEP but lack a complete understanding of required protocols to manage these patients. Further investigation into facilitators and barriers of pharmacy-driven PrEP are needed to enhance utilization within communities.

Keywords: PrEP, Southern United States, Pharmacists, South Carolina, HIV Prevention

INTRODUCTION

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently estimated that there were 36,801 new HIV infections in the United States (US) in 2019 with the Southern US accounting for over half of new HIV infections nationally(1, 2). In response to the persistent HIV epidemic, the US Department of Health and Human Services created the Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) initiative with the goal of a 90% reduction in new HIV infections by 2030 by selecting high-priority areas for intensification of HIV prevention strategies such as HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)(3). The Southern US has been the region of lowest PrEP use nationally(4) and six of seven key states targeted by the EHE initiative are from this region(5). South Carolina (SC) is recognized as a state for the EHE initiative due to the disproportionate occurrence of HIV in rural areas(5). With an estimated 10,249 persons aged ≥ 16 who were eligible for PrEP, yet only 11.7% of them receiving the medication in 2018(6), SC is in critical need of creative ways to facilitate PrEP dissemination throughout the state.

While there are many potential barriers to PrEP use, a key factor is patients’ access to providers able to prescribe the medication. PrEP is typically offered at academic healthcare centers and clinics offering sexual health services(7). However, many eligible patients reside in regions with limited access to these specialized locations. A potential solution is the initiation of PrEP through local pharmacies. Pharmacies are a prime location for implementing PrEP services as they are community-facing with wide geographic dispersal. The CDC describes pharmacies as a more accessible and less stigmatizing location for HIV testing and estimates that 70% of rural residents live within 15 miles of a pharmacy and 90% of urban residents live within 2 miles of a pharmacy(8). In addition, pharmacists have reported that that they are well positioned to play a key role in preventing HIV making them a suitable target for PrEP implementation(9). In December 2021, the Biden Harris National HIV/AIDS strategy outlined these very structural barriers, including state or local laws, and suggests expanding prescribing authority and reimbursement of services for PrEP and post exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to pharmacists(10). In 2019, California became the first state to pass legislation to allow pharmacists to prescribe PrEP, and Colorado, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Maine, Virginia, and New Mexico followed shortly thereafter(11).

Despite the need for novel access points for PrEP and the promising aspect of expanding pharmacists’ scope of practice, few studies have investigated the feasibility of providing PrEP in a pharmacy setting. A recent systematic review found no published articles comparing the effectiveness of PrEP initiation or continuation through pharmacies(12). However, there is an increasing number of non-comparative studies showing the feasibility and/or describing a pilot implementation in which PrEP is offered through pharmacies in various geographic regions of the United States including the South (13–17). Similarly, a recent scoping review supported the feasibility of pharmacy-based interventions to increase PrEP use and its acceptability among potential PrEP users(18). Several states have now expanded PrEP access to include pharmacist-prescribed PrEP, although it is not permitted in SC a key state in the EHE initiative.

Although pharmacists cannot currently prescribe PrEP in SC, it is unknown if providing PrEP would be feasible and acceptable to pharmacists should it become legal. The willingness of SC pharmacists to prescribe PrEP is needed to inform policy changes for expanding PrEP access in the state. As a first step, we conducted formative research using an online survey to gather perspectives on prescribing PrEP among practicing pharmacists in SC.

METHODS

We distributed a 43-question online descriptive questionnaire to pharmacists licensed to practice in SC using Qualtrics survey software (Provo, UT) (Supplementary Information). The survey was developed in collaboration with the Duke Initiative on Survey Methodology and focused on assessing pharmacists’ comfort, knowledge, and readiness to provide HIV and sexual health care, as well as perceptions of the feasibility of providing PrEP in a pharmacy setting. Response options included 4-point Likert scales as well as yes/no items. For certain questions free written responses were allowed. Pharmacists were not required to answer every question. For most questions, pharmacists could only select one response. All demographic questions were self-reported. The survey was designed to take less than 15 minutes to complete. all responses were confidential. During development, we cognitively field-tested the survey to evaluate flow, comprehension, and duration of the survey. Field-testing participants were practicing pharmacists who were not members of the study team and were ultimately not eligible to participate in the final survey. We also specifically examined responses from rural-based pharmacists as supported by the EHE initiative.

We distributed the email survey invitation hyperlink through the University of SC Kennedy Pharmacy Innovation Center’s listserv of licensed pharmacists in SC. The initial invitation was delivered on September 22 2020, with a reminder email sent on October 9 2020, with data collection ending on October 17, 2020. The data were collected using Qualtrics survey software which has features to identify duplicate responses. We did not aim to recruit a sample representative of all pharmacists in SC but rather to offer the survey to pharmacists across the state. To encourage participation, all pharmacists were eligible to enter a drawing for one of three $50 gift cards. At the beginning of the survey, participants were informed of the study procedures to keep their responses confidential and that their participation in the survey was voluntary. Winners were selected using a random number generator and notified via email. Pharmacists provided their implied consent by accessing and participating in the survey.

We performed descriptive analysis of the survey close-ended questions. Completed and partially completed surveys were included in our dataset. Illustrative quotes from open-ended questions were selected to highlight salient viewpoints of pharmacists. The study was approved by the Duke and Prisma Health Institutional Review Boards (Protocol 00104626).

RESULTS

Participants

Of the initial 2680 unique email addresses to which we distributed the survey, 200 were returned as undeliverable. A total of 150 pharmacists participated in the survey, with 129 completing the full survey and 21 partially completing the survey. No duplicate responses were identified. The majority of pharmacists were female (62%, n=93), White (73%, n=110), and non-Hispanic (83%, n=125) (Table 1). Pharmacists practice in a wide range of pharmacy settings including retail (25%, n=37), hospital-based (22%, n=33), independent (17%, n=25), community (13%, n=19), specialty (6%, n=9), and academic (3%, n=4) pharmacies, as well as diverse geographic regions, including small towns (25%, n=38), urban (25%, n=37), suburban (24%, n=36), and rural (11%, n=17) locations. The mean length of practice was 17 years with a range of 1–50 years. One respondent was certified by the American Academy of HIV Medicine which requires direct involvement in the care of persons with HIV (PWH) and a minimum of 45 credits of continuing education in HIV or hepatitis C care(19).

Table 1).

Self-Reported Demographics of Pharmacists Responding to Survey

| Characteristic | N (%) (N=150) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Female | 93 (62) |

| Male | 34 (23) |

| Transgender or Non-binary | 0 (0) |

| Prefer Not to Answer | 2 (1) |

| No Response | 21 (14) |

| Race | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) |

| Asian | 3 (2) |

| Black or African American | 12 (8) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0) |

| White | 110 (73) |

| Other Race | 0 (0) |

| Prefer Not to Answer | 3 (2) |

| No Response | 22 (15) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (1) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 125 (83) |

| Prefer Not to Answer | 3 (2) |

| No Response | 21 (14) |

| Practice Location | |

| Rural | 17 (11) |

| Small Town | 38 (25) |

| Suburban | 36 (24) |

| Urban | 37 (25) |

| No Response | 22 (15) |

| Pharmacy Type | |

| Academic | 4 (3) |

| Community | 19 (13) |

| Hospital Based | 33 (22) |

| Independent | 25 (17) |

| Retail | 37 (25) |

| Specialty | 9 (6) |

| No Response | 23 (15) |

Experiences with Providing HIV and Sexual Health Care

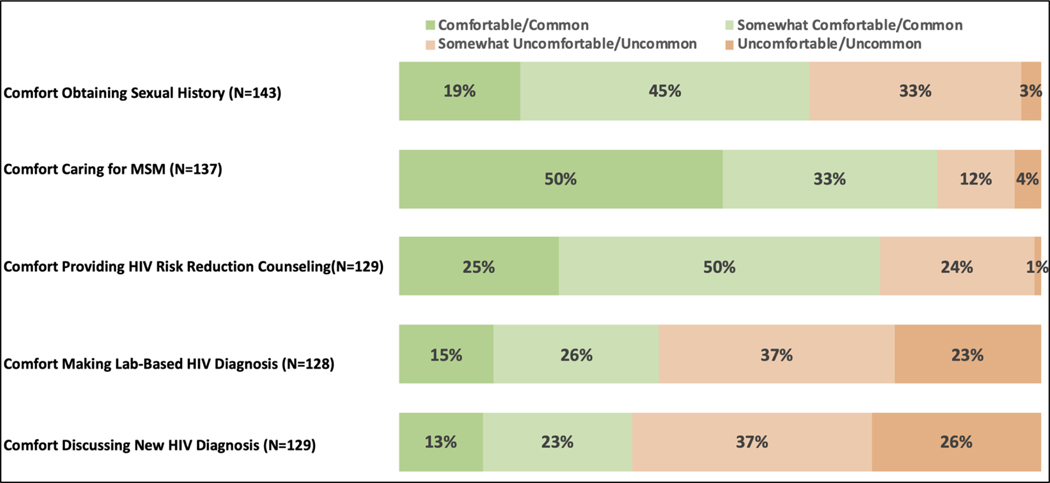

Most pharmacists (64%, n=91/143) reported having comfort with obtaining a sexual health history from their patients (Figure 1), and about half of them (49%, n=66/134) reported having previous sexual health discussions with patients. A similar number (49%, n=66/135) of pharmacists were aware of their patient’s sexual orientation. While many pharmacists reported that they provide care for men who have sex with men (MSM) (67%, n=92/138), more (83%, n=114/137) felt at least somewhat comfortable providing care for this patient population. Pharmacists’ opinions on the prevalence of HIV in their practice community were split. A slim majority of pharmacists (53%, n=73/137) felt HIV was at least somewhat common in their community, while a slightly lower proportion (46%, n=64/137) felt HIV was at least somewhat uncommon. The majority of pharmacists (74%, n=96/129) reported being at least somewhat comfortable providing HIV risk reduction counseling including recommendations for sexually transmitted infections (STI)/HIV testing, discussing risk behaviors, assessing condom use, and discussing number of sexual partners, although 60% (n=76/128) reported being at least somewhat uncomfortable making a lab-based diagnosis of HIV. Even more (63%, n=82/129) were at least somewhat uncomfortable discussing a new HIV diagnosis with a patient.

Figure 1).

South Carolina Pharmacists’ Survey Responses: Experiences with Providing HIV and Sexual Health Care. Pharmacists were not required to answer each question.

Attitudes Toward PrEP

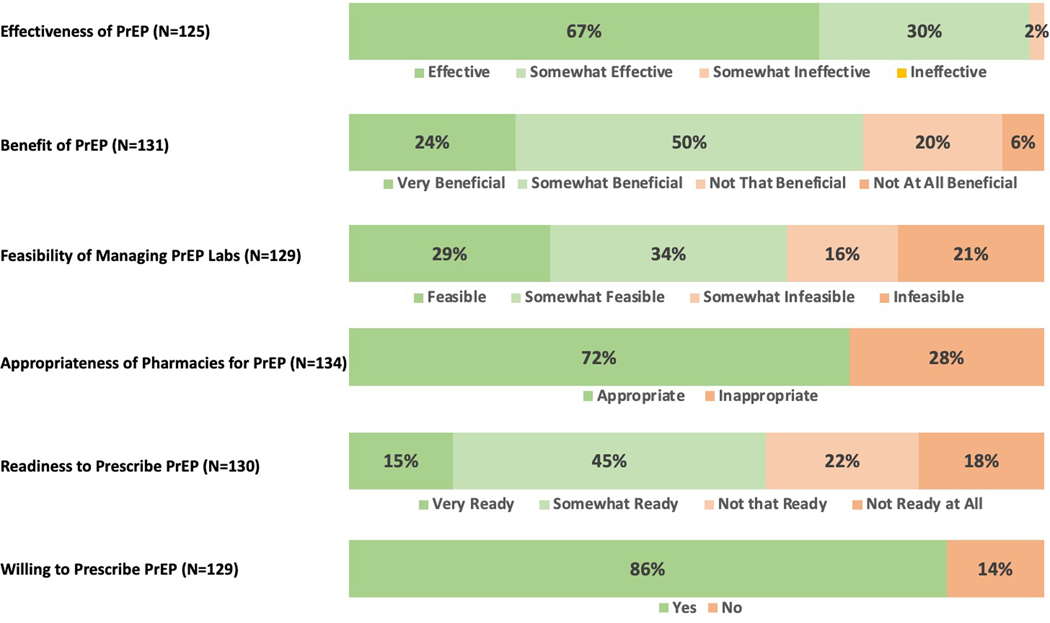

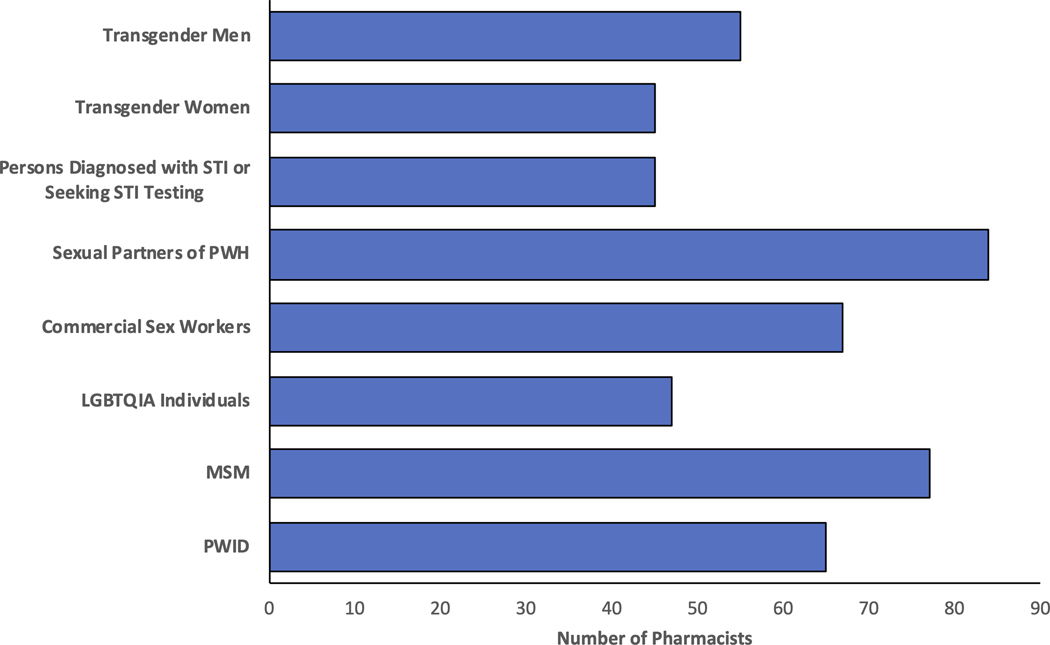

Ninety-three percent of pharmacists (n=128/137), including all rural pharmacists, were aware of PrEP, and 88% (n=119/136) were aware of HIV PEP. Nearly all pharmacists (97%, n=122/125), including all rural pharmacists, thought PrEP was efficacious at preventing the transmission of HIV (Figure 2), and many (74%, n=97/131) felt that providing PrEP would be beneficial to their patient population. Yet, there were differing opinions on which patient groups should be offered PrEP, with only 37% (n=45/122) of pharmacists who felt that persons presenting with STI or for STI testing would be eligible for PrEP (Figure 3). Additionally, 45% (n=60/133) indicated that “providing PrEP will lead some individuals to engage in more high-risk sex behaviors” was a legitimate concern.

Figure 2).

South Carolina Pharmacists’ Survey Responses: Attitudes, Feasibility, Acceptability, and Readiness to Provide PrEP Services. Pharmacists were not required to answer each question.

Figure 3).

Pharmacists’ Perceived Eligibility for PrEP (N=122)

PWID (Persons Who Inject Drugs), MSM (Men who have sex with men), LGBTQIA (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual), PWH (Persons With HIV), STI (Sexually Transmitted Infection)

Feasibility and Acceptability of Providing PrEP Services

Many pharmacists reported that they were currently providing counseling for multiple chronic health conditions including hypertension (86%, n=128/149), diabetes (86%, n=128/149), anticoagulation (76%, n=111/147), and hepatitis (40%, n=57/141), in addition to administering vaccinations (79%, n=117/148). Furthermore, many pharmacists indicated that they already provide HIV antiretroviral medications (78%, n=108/138) and counseling for these medications (78%, n=84/108). Fewer pharmacists reported dispensing PrEP medication (41%, n=56/135) and some pharmacists (18%, n=24/135) were unsure whether this medication was dispensed at their pharmacy or not.

Two-thirds of pharmacists said they were not aware of how to manage a patient on PrEP (67%, n=90/135). Of these pharmacists, the majority practiced in retail, hospital based, and independent pharmacies (n=25, n=23, n=18, respectively). Despite lack of PrEP management awareness, pharmacists reported that management of laboratory testing in a pharmacy setting was feasible (63%, n=81/129). They also reported many aspects of clinical PrEP management that would be difficult to implement. Pharmacists ranked hepatitis B serologies, which are necessary to review prior to starting PrEP per CDC guidelines, as the most difficult test to interpret followed by HIV testing, serum creatinine, and urine pregnancy testing (n=111). When discussing results with patients, pharmacists ranked discussing the results of HIV testing with the patient to be the most difficult, followed by hepatitis B serologies, serum creatinine, and urine pregnancy testing (n=105).

Overall, 72% of pharmacists (n=97/134) thought that a pharmacy was an appropriate location to provide PrEP services. Rural pharmacists felt similarly on the appropriateness of pharmacies for PrEP. In the free response sections of the survey asking why pharmacies are an appropriate place to prescribe PrEP, pharmacists stated: “Pharmacies are accessible to anyone off the street. There are many barriers, some perceived, to getting a patient seen by a physician” and “Patients are more likely to come to the pharmacy before seeking care from a physician” and “Prescribing PrEP at a pharmacy will allow more patients to have access to care and pharmacists/pharmacy interns are able to provide proper counseling and follow-up”.

Readiness to Provide PrEP Care

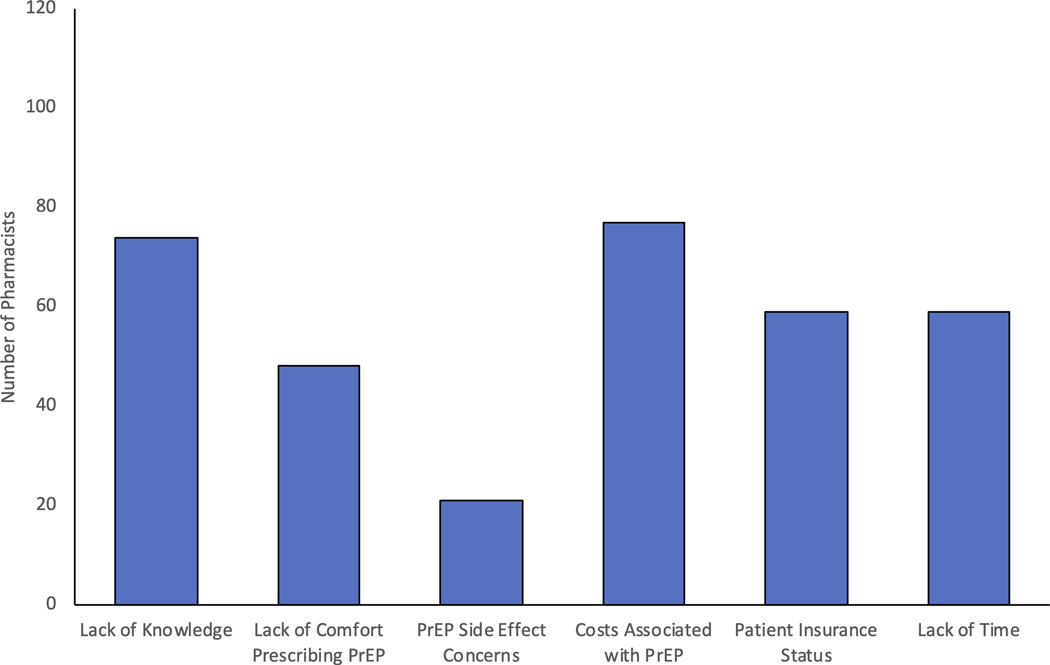

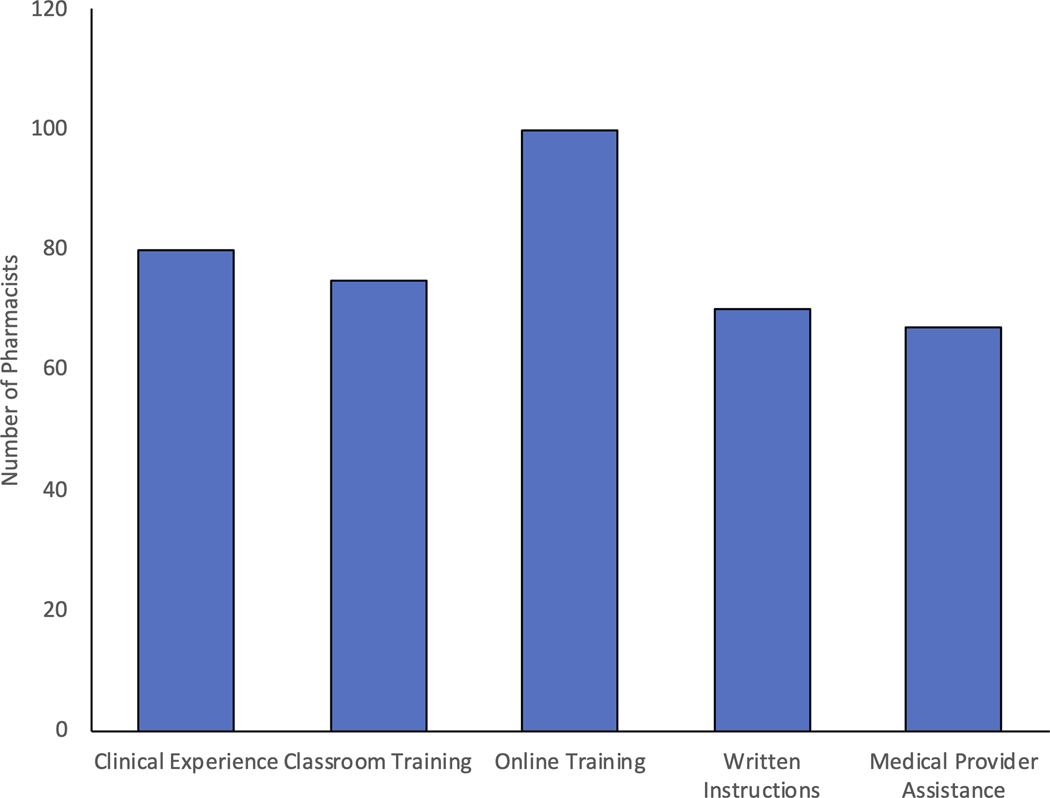

A large proportion of pharmacists (60%, n=79/130) reported being at least somewhat ready to provide PrEP services including 65% of rural pharmacists. Barriers to providing PrEP care from most to least reported included costs, lack of staff knowledge with PrEP, insurance status of patient, lack of time, lack of comfort prescribing PrEP, and concerns regarding the side effects of PrEP (Figure 4A). Pharmacists also indicated in free-response answers that patient follow up-visits, staffing limitations, liability, and communication with providers were potential barriers. One pharmacist noted, “We are a small pharmacy with only one pharmacist on duty at a time. We also have limited space for counselling. This type of program would need more staff and more space than we have available”. To overcome these obstacles, pharmacists requested additional trainings, guidelines, medical provider assistance, and experience with the medication (Figure 4B). The vast majority of pharmacists (86%, n=111/129), including 94% of rural pharmacists, stated they would be willing to prescribe PrEP.

Figure 4).

Pharmacists’ Perceived Barriers and Needs to Providing PrEP

A) Pharmacists Perceived Barriers to Providing PrEP (N= 118)

B) Pharmacists’ Perceived Needs for PrEP (N=118)

DISCUSSION

Our study represents the first broad survey to assess pharmacists’ readiness to provide PrEP in SC, a priority jurisdiction of the national Ending HIV Epidemic initiative. This sample of pharmacists was representative of a broad swath of SC pharmacists and nearly all surveyed pharmacists were aware of PrEP and thought it was an efficacious way to prevent HIV transmission. The majority believed that pharmacies were appropriate for PrEP prescription and that PrEP would be beneficial for their clientele. The vast majority of pharmacists surveyed indicated that they would be willing to prescribe PrEP, and many were also ready to provide PrEP. These findings are encouraging and can lead to further evaluation of PrEP dissemination throughout the region.

Similar to prior studies(20–23), we found that pharmacists were supportive of providing PrEP within pharmacies but required additional training on PrEP and its management in order to feel more comfortable delivering PrEP services. This training would need to include monitoring for side effects, interpretation of lab results, handling of specimens for blood tests, and appropriate communication about sexual health and drug use in a culturally sensitive conversation. The training should also include information on the prevalence of HIV in the United States as slightly less than half of surveyed pharmacists thought that HIV was somewhat uncommon in their region despite being in SC, a key state for the EHE initiative. In turn, this can highlight the importance of HIV prevention in the pharmacists’ practice location. Furthermore, pharmacists may benefit from training that describes indications for PrEP as many pharmacists in our survey did not choose persons diagnosed with or seeking testing for STIs as eligible for PrEP despite its inclusion in recent guidelines.

Fortunately, there are many resources that can be utilized by pharmacists for PrEP training. The CDC provides eLearning modules for pharmacists that address common concerns such as prescribing PrEP, engaging patients in discussions about PrEP, HIV testing interpretation, and how PrEP can be used for HIV prevention(8, 24). In addition, the CDC provides guidelines to help prescribers determine who is eligible to be started on the medication(25). Regional AIDS Education and Training Centers can play a key role in expanding awareness and building capacity for PrEP implementation. There are also resources specifically for pharmacists implementing PrEP into their practice(26). Educational efforts such as these have been effective in increasing PrEP prescriptions among Southern primary care providers(27).

Pharmacists are already providing preventative services such as providing unused syringes and naloxone to persons who inject drugs, prescribing and administering injectable and self-administered hormonal contraceptives, HIV and hepatitis C testing, blood glucose monitoring for diabetes, and cholesterol and blood pressure checks for cardiovascular disease(28–30). More recently, pharmacists have been allowed to prescribe nirmatrelvir/ritonavir with the Emergency Use Authorization during the COVID pandemic(31). As pharmacists’ scope of practice expands with prescriptive authority(32, 33), pharmacists may prescribe PrEP and HIV PEP in certain states(34, 35). Unfortunately, SC law does not currently allow pharmacists the ability to provide PrEP, limiting their ability to provide this vital preventative service. Collaboration with policy makers is needed to expand the scope of practice of SC pharmacists to include PrEP prescribing and allowing local pharmacies to serve as access points for HIV preventative services.

Affordability of the medication is also a common concern when managing PrEP. Patient assistance programs exist such as the federal Ready, Set, PrEP program that work with pharmacies to provide PrEP at no cost to patients(36). Pharmacists play a key role in managing health care costs for their health systems and patients(37). They often have experience managing prior authorizations, insurance claims, out of pocket costs, and completing patient assistance applications for the patients they serve. Pharmacist-driven medication therapy management, including for HIV care, has resulted in improved patient outcomes and costs(38).

Another barrier to PrEP implementation at pharmacies is the time commitment needed to counsel, test, and start a patient on PrEP. Pharmacists are frequently overburdened which can limit the amount of time they have to spend with a patient and lead to potential adverse events(39). Additionally, their pharmacy may not have confidential areas to privately discuss PrEP in a pharmacy setting(40). These concerns may be partially mitigated by the route that the patient prefers to access the pharmacy. A prior study demonstrated that patients tend to obtain confidential prescriptions through drive-through pharmacies, but are more open to counseling when entering the pharmacy in-person(41). Still, pharmacies that plan to begin providing PrEP services will need to allow for adequate time and a confidential location for pharmacists and patients to discuss PrEP based on their own unique practice structure and layout.

Pharmacists also had concerns about PrEP leading to increased high-risk sexual encounters which in turn may lead to increased STI transmission rates in their patients. This a valid concern as PrEP has been associated with increased STI rates(42). This is especially important in SC which was ranked as the fourth highest state for reported rates of chlamydia and third highest state for reported cases of gonorrhea in 2020(43). Fortunately, pharmacists are uniquely situated to help reduce the surge of infections. Prior studies have shown that pharmacists can reduce time to therapy and ensure optimum therapy for patients with STIs(35). In addition, patients have found pharmacist-led testing for and managing of STIs to be acceptable(44).

Limitations to our study include a low response rate. Our aim was to collect descriptive data from a sample of pharmacists from a variety of practice locations and pharmacy types across SC on their readiness to provide PrEP. However, the response rate achieved is typical for surveys administered in the manner we used including those for medical providers and pharmacists(45, 46). Yet, surveys with low response rates can still provide quality and useful data, especially when the aim of a study is to gather information to help inform subsequent interventions, such as ours (47). The US Department of Health and Human Services reported the demographics of pharmacists nationally to be 45.% Male, 54.5% Female, 70.4% White, 5.9% Black, 17.9% Asian, 0.2% American Indian/Alaska Native, 0.1% Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, 1.8% Multiple/Other race, and 3.7% Hispanic from 2011–2015(48). The demographics self-reported in our survey are similar but with under reporting from Asian and Hispanic pharmacists. It is important to engage these underrepresented groups in future studies since patients may prefer racial and ethnic concordance with their healthcare providers(49). This is especially important as Black and Hispanic persons are less likely to use PrEP and are disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic(50).

In addition, pharmacists who received an invitation to participate in our survey had to have an email address listed within the University of SC’s professional listserv. It is possible that this skewed results toward pharmacists who have ties to academia. However, we did have a range of different practice types among responding pharmacists in the online survey. There may also be responder and confirmation bias in that pharmacists responding to the survey may have wanted to appear more knowledgeable and accepting of PrEP and less willing to share negative PrEP viewpoints. Similarly, responses may be skewed either positively or negatively based on time constraints of pharmacist who participated in the survey. Our results also have a limitation in that pharmacists were only able to select one practice location and type in our survey, while it is very possible that pharmacists were working in multiple settings or having overlap between pharmacy sites. In addition, we did not define the different pharmacy practice settings offered in our survey. By allowing pharmacists to choose which option best described their pharmacy practice, there may be discrepancies in how different pharmacists interpret their workplace. Our survey was also administered prior to the 2021 update to the CDC PrEP guidelines which updated eligibility criteria for PrEP and ways to provide PrEP counseling (25). Ultimately, our formative results can help provide a framework toward a pharmacist-driven PrEP model which can then be disseminated and used to create a PrEP program among pharmacists in SC. However, the generalizability of this model and pharmacist prescribing practice to other states is ultimately dependent upon individual state laws.

CONCLUSION

To our knowledge this was the first survey of SC pharmacists on their viewpoints surrounding providing PrEP services. In our sample pharmacists believed that PrEP was beneficial, and that the pharmacy was a feasible and acceptable location for providing PrEP services. The majority of surveyed pharmacists were willing to prescribe PrEP if allowed. However, further educational programs may be needed to prepare and support pharmacists in providing PrEP services. We will use these data, coupled with data from a subsequent qualitative descriptive study we conducted with selected survey participants, to begin the development of a framework for pharmacists to deliver PrEP in the South. Ultimately, the decision to allow SC pharmacists to prescribe PrEP will be made by the SC legislature. However, it is our hope that real world data from our survey, combined with the new National HIV/AIDS Strategy, will help the needle move in the right direction. We are hopeful that increasing PrEP access through pharmacies will provide this highly effective HIV prevention medication to persons at risk for HIV and who may not have had access previously.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Portions of this work was presented in an abstract at the Duke University 17th Annual Center for AIDS Research Retreat in October 2021 and the National Center for AIDS Research Meeting in November 2021. Study data is available upon request from the corresponding author.

FUNDING

This research was supported by the Duke University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program [5P30 AI064518]. CMB was supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award of the National Institutes of Health under award number [T32AI007392]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

MSM received a grant from the Gilead Foundation paid to her institution.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report: Statistics Overivew. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/index.html. Accessed July 30, 2021.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnosis of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2017. HIV Surveillance Report, vol. 29. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2017-vol-29.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services. Ending the HIV Epidemic: About Ending the HIV Epidemic in the US: Overview. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview. Accessed July 30 2021.

- 4.Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Giler RM, Weiss K, Pembleton E, Guest J, et al. The prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis use and the pre-exposure prophylaxis-to-need ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):841–9. Epub 2018/07/10. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services. Ending the HIV Epidemic: About Ending the HIV Epidemic in the US: Priority Jurisdictions: Phase I. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/jurisdictions/phase-one. Accessed July 30 2021.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas, 2018. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2020;25(No. 2). http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published May 2020. Accessed July 30, 2021.

- 7.Mayer KH, Chan PA, R RP, Flash CA, Krakower DS. Evolving Models and Ongoing Challenges for HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Implementation in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(2):119–27. Epub 2017/10/31. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Diseaes Control and Prevention. HIV Testing in Retail Pharmacies. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/effective-interventions/diagnose/hiv-testing-in-retail-pharmacies/index.html?Sort=Title%3A%3Aasc&Intervention%20Name=HIV%20Testing%20in%20Retail%20Pharmacies. Accessed August 3 2021.

- 9.Meyerson BE, Ryder PT, von Hippel C, Coy K. We can do more than just sell the test: pharmacist perspectives about over-the-counter rapid HIV tests. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):2109–13. Epub 2013/02/19. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0427-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The White House. 2021. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States 2022–2025. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong BJ. Are Pharmacists Prepped for PrEP? AIDS Education & Training Center Program National Resource Center. https://aidsetc.org/blog/are-pharmacists-prepped-prep. Published March 24, 2022. Accesssed February 8, 2023. 2022.

- 12.Kennedy CE, Yeh PT, Atkins K, Ferguson L, Baggaley R, Narasimhan M. PrEP distribution in pharmacies: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e054121. Epub 20220221. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Havens JP, Scarsi KK, Sayles H, Klepser DG, Swindells S, Bares SH. Acceptability and feasibility of a pharmacist-led HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) program in the Midwestern United States. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(10). doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khosropour CM, Backus KV, Means AR, Beauchamps L, Johnson K, Golden MR, et al. A Pharmacist-Led, Same-Day, HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Initiation Program to Increase PrEP Uptake and Decrease Time to PrEP Initiation. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2020;34(1):1–6. doi: 10.1089/apc.2019.0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tung EL, Thomas A, Eichner A, Shalit P. Implementation of a community pharmacy-based pre-exposure prophylaxis service: a novel model for pre-exposure prophylaxis care. Sex Health. 2018;15(6):556–61. Epub 2018/11/08. doi: 10.1071/SH18084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan K, Lewis J, Sanchez D, Anderson B, Mercier R-C. 1293. The Next Step in PrEP: Evaluating Outcomes of a Pharmacist-Run HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Clinic. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2018;5(suppl_1):S395–S. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy210.1126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gauthier TP, Toro M, Carrasquillo MZ, Corentin M, Lichtenberger P. A PrEP Model Incorporating Clinical Pharmacist Encounters and Antimicrobial Stewardship Program Oversight May Improve Retention in Care. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(2):347–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao A, Dangerfield DT 2nd, Nunn A, Patel R, Farley JE, Ugoji CC, et al. Pharmacy-Based Interventions to Increase Use of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis in the United States: A Scoping Review. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(5):1377–92. Epub 20211020. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03494-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Academy of HIV Medicine. HIV Pharmacist. https://aahivm.org/hiv-pharmacist/. Accessed September 15, 2021.

- 20.Okoro O, Hillman L. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: Exploring the potential for expanding the role of pharmacists in public health. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2018;58(4):412–20 e3. Epub 2018/05/24. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaeer KM, Sherman EM, Shafiq S, Hardigan P. Exploratory survey of Florida pharmacists’ experience, knowledge, and perception of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2014;54(6):610–7. Epub 2014/10/25. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.14014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unni EJ, Lian N, Kuykendall W. Understanding community pharmacist perceptions and knowledge about HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) therapy in a Mountain West state. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2016;56(5):527–32 e1. Epub 2016/09/07. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koester KA, Saberi P, Fuller SM, Arnold EA, Steward WT. Attitudes about community pharmacy access to HIV prevention medications in California. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2020;60(6):e179–e83. Epub 20200712. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Care System. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/effective-interventions/prevent/prep/index.html#PrEP-Training. Accessed August 4 2021.

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Public Health Service: Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States - 2021 Update: A Clinical Practice Guideline. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2021.pdf. Published December 2021.

- 26.Lopez MI, Cocohoba J, Cohen SE, Trainor N, Levy MM, Dong BJ. Implementation of pre-exposure prophylaxis at a community pharmacy through a collaborative practice agreement with San Francisco Department of Public Health. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2020;60(1):138–44. Epub 2019/08/14. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2019.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clement ME, Seidelman J, Wu J, Alexis K, McGee K, Okeke NL, et al. An educational initiative in response to identified PrEP prescribing needs among PCPs in the Southern U.S. AIDS Care. 2018;30(5):650–5. Epub 2017/10/04. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1384534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyerson BE, Davis A, Agley JD, Shannon DJ, Lawrence CA, Ryder PT, et al. Predicting pharmacy syringe sales to people who inject drugs: Policy, practice and perceptions. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;56:46–53. Epub 2018/03/21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snella KA, Canales AE, Irons BK, Sleeper-Irons RB, Villarreal MC, Levi-Derrick VE, et al. Pharmacy- and community-based screenings for diabetes and cardiovascular conditions in high-risk individuals. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2006;46(3):370–7. Epub 2006/06/03. doi: 10.1331/154434506777069598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Min AC, Andres JL, Grover AB, Megherea O. Pharmacist Comfort and Awareness of HIV and HCV Point-of-Care Testing in Community Settings. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21(5):831–7. Epub 2019/07/02. doi: 10.1177/1524839919857969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA News release. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Pharmacists to Prescribe Paxlovid with Certain Limitations. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-pharmacists-prescribe-paxlovid-certain-limitations. Published July 6 2022. Accesssed September 28 2022.

- 32.Adams AJ, Weaver KK. The Continuum of Pharmacist Prescriptive Authority. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(9):778–84. Epub 2016/06/17. doi: 10.1177/1060028016653608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving Patient and Health System Outcomes through Advanced Pharmacy Practice. A Report to the U.S. Surgeon General. Office of the Chief Pharmacist. U.S. Public Health Service. Dec 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farmer EK, Koren DE, Cha A, Grossman K, Cates DW. The Pharmacist’s Expanding Role in HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019;33(5):207–13. Epub 2019/05/09. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Navarrete J, Yuksel N, Schindel TJ, Hughes CA. Sexual and reproductive health services provided by community pharmacists: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(7):e047034. Epub 20210726. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy. Ready, Set, PrEP. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/prep-program. Accessed September 21, 2021.

- 37.Dalton K, Byrne S. Role of the pharmacist in reducing healthcare costs: current insights. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2017;6:37–46. Epub 2018/01/23. doi: 10.2147/IPRP.S108047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirsch JD, Gonzales M, Rosenquist A, Miller TA, Gilmer TP, Best BM. Antiretroviral therapy adherence, medication use, and health care costs during 3 years of a community pharmacy medication therapy management program for Medi-Cal beneficiaries with HIV/AIDS. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(3):213–23. Epub 2011/03/26. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2011.17.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shao SC, Chan YY, Lin SJ, Li CY, Kao Yang YH, Chen YH, et al. Workload of pharmacists and the performance of pharmacy services. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231482. Epub 2020/04/22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Famiyeh IM, McCarthy L. Pharmacist prescribing: A scoping review about the views and experiences of patients and the public. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13(1):1–16. Epub 2016/02/24. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chui MA, Halton K, Peng JM. Exploring patient-pharmacist interaction differences between the drive-through and walk-in windows. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2009;49(3):427–31. Epub 2009/05/16. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.07165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Traeger MW, Cornelisse VJ, Asselin J, Price B, Roth NJ, Willcox J, et al. Association of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis With Incidence of Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Individuals at High Risk of HIV Infection. Jama. 2019;321(14):1380–90. Epub 2019/04/10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 STD Surveillance Report: State Ranking Tables. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2020/tables/2020-STD-Surveillance-State-Ranking-Tables.pdf. Accessed June 23 2022.

- 44.Deppe SJ, Nyberg CR, Patterson BY, Dietz CA, Sawkin MT. Expanding the role of a pharmacist as a sexually transmitted infection provider in the setting of an urban free health clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(9):685–8. Epub 2013/08/16. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silverman TB, Schrimshaw EW, Franks J, Hirsch-Moverman Y, Ortega H, El-Sadr WM, et al. Response Rates of Medical Providers to Internet Surveys Regarding Their Adoption of Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV: Methodological Implications. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2018;17:2325958218798373. Epub 2018/09/19. doi: 10.1177/2325958218798373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hardigan PC, Popovici I, Carvajal MJ. Response rate, response time, and economic costs of survey research: A randomized trial of practicing pharmacists. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016;12(1):141–8. Epub 2015/09/04. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Response Rates - An Overview. 2021. https://www.aapor.org/Education-Resources/For-Researchers/Poll-Survey-FAQ/Response-Rates-An-Overview.aspx. Accessed February 19 2021.

- 48.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. 2017. Sex, Race, and Ethnic Diversity of U.S, Health Occupations (2011–2015), Rockville, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takeshita J, Wang S, Loren AW, Mitra N, Shults J, Shin DB, et al. Association of Racial/Ethnic and Gender Concordance Between Patients and Physicians With Patient Experience Ratings. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024583. Epub 20201102. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kanny D, Jeffries WLt, Chapin-Bardales J, Denning P, Cha S, Finlayson T, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex with Men - 23 Urban Areas, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(37):801–6. Epub 20190920. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6837a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.