Abstract

Background

Government guidelines for lockdown and quarantine measures impacted the daily lives and health of individuals amid the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The pandemic caused significant changes in the daily routine and lifestyles of individuals worldwide with the simultaneous emergence of mental health disorders. Stress caused by COVID-19 pandemic outbreaks and consequent social isolation significantly influenced the mental health and quality of life of professionals among Indian population. This study aimed to evaluate the mental health and quality of life among Indian professionals embarked as COVID-19 survivors.

Methods

A 20-item self-administered questionnaire was developed and circulated among the participants with the following domains: helplessness, apprehension, mood swing, physical activity, restlessness, insomnia, irritation, mental stress, and emotional instability to assess their mental health and quality of life.

Results

Of the total 322 participants, 73.6% of individuals experienced helplessness, 56.2% felt the need for counseling, 65.5% reported feeling irritated even over minor issues, 62.1% experienced negative thoughts during isolation, 76.5% experienced difficulty in falling asleep, and 71.9% felt restless during their course of illness.

Conclusion

The study concludes that mental health and quality of life among COVID-19 survivors was affected by sleep, physical activities, emotional instability, and job profile, as well as support from others, mood swings, and the need for counseling.

Keywords: COVID-19, Exercise, Mental health, Quality of life, Quarantine

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), an acute respiratory syndrome caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 pathogen, was first found in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China in December 2019 [1]. It’s been nearly 2 years and COVID-19 are still surging at intervals across different nations. COVID-19 caused an estimated of more than 260 million cases and 5 million deaths globally and approximately more than 4 crore confirmed cases and 4 lacs death in India. World health organization declared it as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [2]. Highest weekly average peak of 4.3 million confirmed new cases were found in December 2020 than at any other time [3].

Measures to control escalation of the virus comprised of track and tracing, self-isolation, quarantine, social distancing, community containment and nationwide lockdown [4]. To reduce the danger of infection, authorities around the world recommended individuals to reduce their pace take a slow in their daily routines and to stick on social distancing [5]. Implementation of lockdown affected individual’s health at a great extent, mental health being maximally affected regardless of age, sex, occupation, or other factors [3].

Mental health is defined as a state of well-being in which an individual recognises his or her own abilities and can manage typical life challenges, work successfully and fruitfully and contribute to community [6]. Stress from rapidly spreading disease, abrupt end of social interactions and the disruption of daily routines had significant impacted individuals mental health and quality of life. Quality of life is defined as an individual’s perception of their position in life in context to culture and value system in which they live and in relation to their goals expectations, standards and concerns [7]. Rapid spread of COVID-19 presented with plenty of new issues for individuals expanding to all ages, including reduced outdoor or free-living, reduced physical activity, increased idle time, interrupted sleep and all these resulted in affected health-related quality of life [8]. COVID-19 is yet to be treated with a promising medication and many people around the world are still under quarantine.

COVID-19 has potential to harm individual’s mental health in n number of ways, possibly because of managing work from home with burden of worries [9]. The implementation of home confinement policies and restrictions to prevent mass gatherings around the world was believed to have exacerbated cases of daytime stress and sleep disruption [4]. Feeling of loss, excessive use of internet to seek information or maintain social contacts, fear of becoming infected, impulsive decisions and strict expectations were only a few of the things that could have interfered with good sleep quality during that tough period [9].

Sleep difficulties are far more common in individuals who suffer from mental illnesses, it is a biological indication of depression, a relapse indicator in bipolar disorder and can be found in up to 80.0% of people with psychotic diseases often persisting after other symptoms have been treated [10]. Amid COVID-19, sleep disruption was most common reported mental symptom among general population, with insomnia being the topmost among all, ranging from 6.0% to 30.0% [10]. During COVID-19 emergence, major concerns including fear of contaminating others, social isolation, running out of all savings, fear of dying from this fatal and incurable condition and capacity to perform work in near future, were all the considerable causes for mental distress over a long period of time [11].

As mental health and quality of life are vital aspects of health, they have been an area of concern in normal as well as the affected population. Professionals are defined as personals of a community who shares similar values and norms for an acceptable practice and have specialised knowledge and judgement skills for a defined work. Professionalism includes working for a nation with altruism, autonomy, lifelong learning and adherence to code of ethics and laws of working organization [12]. Work from home emerged as a perk to protect from infection but on other hand it resulted in overburden and stressful long duration in majority of cases. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate mental health and quality of life among COVID-19 survivors Indian professionals. The results of this study will aid in understanding the impact of COVID-19 on mental health and quality of life of working professionals who tested positive for COVID-19 disease and aid in development of appropriate strategies to cope with affected mental health thus improving the overall quality of life.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Following approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee, the study was done in accordance with the National ethical guidelines for Biomedical and Health Research involving human participants-Indian Council of Medical Research guidelines and guidelines of Helsinki declaration 2013 [13]. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Maharishi Markandeshwar (Deemed to be Universty)(IRB no. MMDU/IEC-2164).

A cross sectional, descriptive online survey was conducted to explore impact of COVID-19 on mental health and quality of life of Indian working male and female professionals of age ≥ 23 years, tested positive for COVID-19 during any of three COVID-19 waves. Participants were excluded if they were having any pre-existing neurological condition and on medication of any psychiatric condition.

Data was collected via online mode using snowball sampling. This method was chosen as it showcased highest possibility during COVID-19 crisis for maximum participation from individuals. A self-administered questionnaire containing complete description of the study’s objective, procedures and rights of participants were sent to professionals in all regions of the country via E-mails, WhatsApp Messenger, and other social media applications. Before administration, the questionnaire was tested on different web browsers to secure validness. The layout was checked on different devices including laptops, tablets, and smartphones to make sure the ease of reading and answering the questions. Other technical and security features were also considered including no more than one response from the same participant.

Data collection was started on 30 December 2021 and entries stopped on 28 January 2022. A consent form was attached with questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of three sections; consent form, demographic data, and survey questions and total 25 questions out of which five questions were on demographic data of participant and 20 questions were based on following domains; Helplessness, Apprehension, Mood swings, Physical activity, Restlessness, Insomnia, Irritation, Mental stress, Emotional Instability.

Sample size of 322 was obtained using formula n = Zα2 (p)(1–p)/d2. A total of 372 participants participated. Out of which 50 participants left the form unfiled. Complete 322 responses were obtained and evaluated.

Data was analysed using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft). Frequency distribution including tables, pie charts and bar graphs were used to analyse data. The data of age was found to be normally distributed therefore results were represented using mean and percentage.

RESULTS

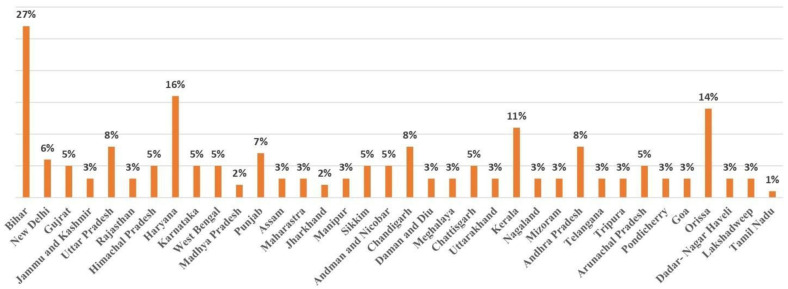

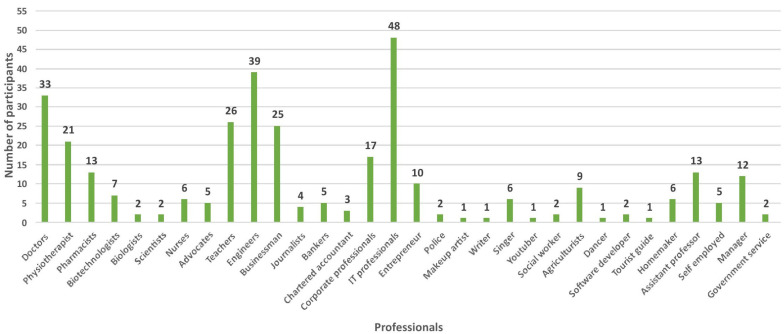

A total of 322 responses were obtained from across the nation, of which 202 (62.7%) were males and 120 (37.3%) were females. Mean age of male participants was 36.0±12.6 and female participants was 33.0±10.9 (Table 1). Responses were obtained from all over India including 7 union territories and 29 states. Maximum responses were obtained from Bihar (27.0%) and minimum responses were obtained from Tamil Naidu (1.0%) as shown in Fig. 1. Participants pursuing various types of professions participated from all over India. Out of all highest participation was done by doctors and minimum participation was done by makeup artist, youtuber, writer, dancer and tourist (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Age distribution of participants

| Sex | Mean ± SD | Minimum age (In yr) | Maximum age (In yr) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 36.0 ± 12.6 | 23 | 72 | 22–72 |

| Female | 33.0 ± 10.9 | 23 | 66 | 23–66 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation, number only, or mean (range).

Fig. 1.

State wise distribution.

Fig. 2.

Occupation.

1. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health

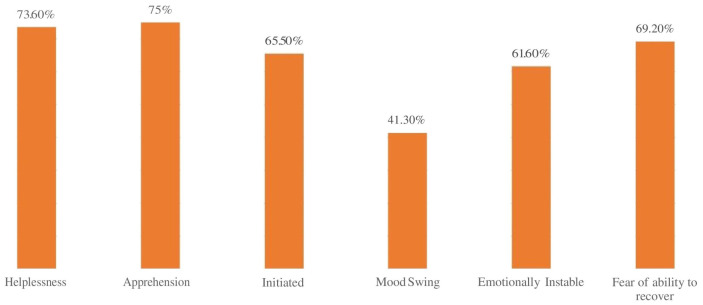

Of total 322 participants, 73.6% stated that they experienced helplessness when they tested positive for COVID-19, 75.0% experienced the state of apprehension when they were under isolation during COVID-19 illness, 65.5% reported that they get irritated over minor issues, 41.3% experienced mood swings during illness, 61.6% experience emotional instability due to isolation and 69.2% reported fear of not being able to recover from illness (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health.

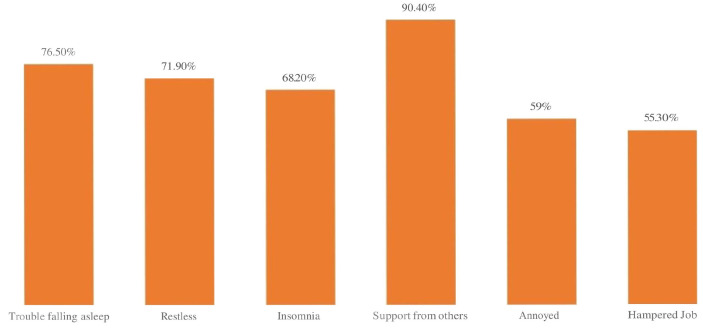

2. Impact of COVID-19 on quality of life

Of total 322 participants, 76.5% of the individuals experienced trouble while falling asleep, 71.9% reported that they experienced restlessness while laying on bed due to overthinking, 68.2% experienced insomnia while worrying about their future and family, 90.4% got enough support from family members, relatives, friends, and colleagues, 59.0% find themselves getting annoyed with their closed ones during their illness and 55.30% reported that they felt that illness impacted their job profile and relationship with colleagues (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Impact of COVID-19 on quality of life.

3. Combined effect of COVID-19 on mental health and quality of life

Out of all participants only 25.0% reported that they got proper medical care during the scarcity of medical facilities, 38.5% were able to perform physical activity during their course of illness, 38.9% experienced emotional instability, 42.2% come up against financial crisis, 43.8% felt the need of counselling to cope with mental stress emerged during their illness, 34.5% have changed their perception towards their life and 37.9% experienced worsening of pre-existing health condition during their illness (Table 2).

Table 2.

Affected mental health and quality of life post COVID-19 pandemic illness

| Question | Response (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Yes | No | |

| Accessibility of proper medical care during scarcity of medical facilities | 25.0 | 75.0 |

| Indulgence in physical activity | 38.5 | 61.5 |

| Emotional instability during isolation | 38.9 | 61.6 |

| Financial crisis during COVID-19 illness | 42.2 | 57.8 |

| Need of counselling to cope up with the mental stress during COVID-19 illness | 43.8 | 56.2 |

| Changed perception towards life after the illness | 34.5 | 65.5 |

| Worsening of pre-existing health condition during and after the passage of illness period | 37.9 | 62.1 |

Values are presented as number (%).

DISCUSSION

322 COVID-19 survivors from all over India, pursuing different kinds of jobs participated in the study. There were 202 (62.7%) males and 120 (37.3%) females with mean age 36.0±12.6 and 33.0±10.9 years respectively. The findings of present study showed that 76.5% of individuals experienced trouble while falling asleep during COVID-19 illness period most probably because of frequent talking and thinking about the pandemic, overthinking about their future and family and having fear of contaminating their family members [9]. Of total 322 participants 67.6% experienced difficulty while settling into a comfortable sleeping position while laying on bed. These findings are in line with previous study. Yu et al. [4] found that isolated populations particularly those who are medically isolated have a higher prevalence of sleep issues with over 70.0% reporting trouble falling asleep and getting up early at least once in the previous week. Of total 322 participants 68.2% experienced insomnia while worrying about their future and family and patients recovered from COVID-19 infection have high rates of sleeplessness [14]. Mandelkorn et al. [15] also showed that changes imposed due to pandemic resulted in an increase in emergence of sleep issues throughout the world. Intake of sleeping drugs were also documented. Women aged 31 years-45 years who were under quarantine and were less physically active were most sensitive to have sleep disorders.

According to this study, 71.9% of participants stated that due to overthinking they experienced restlessness i.e. they were unable to relax themselves as a result of anxiety. Recent studies shows individuals who self-isolated themselves in fear of getting infected from virus and have increased alcohol intake reported more loss of sleep, disrupted sleep, daytime sleepiness, symptoms of restless leg compared to those who do not self-isolated themselves during the course of illness [2].

Most participants (58.7%) reported experience of mood swings during their illness period. The suspected cause of this could be self-isolation, home confinement, loss of the daily routine, decreased physical activity and increased inactive or sedentary behaviours during COVID-19 restrictions. According to some recent studies there is clear indication of increased stress, depression, annoyance, over-tiredness and confusion as well as decreased strength indicating significant mood disruption and raising the risk of a mental health emergency [16].

Current study findings reveal 70.7% of the population to report being in a scared state during the course of their illness. The probable reason for this could be the virus which was progressively infecting the population. Lack of appropriate treatment and drugs were the main reason that was making most of the population afraid during their illness. Initially, there was little awareness of the virus among general public and it was creating havoc on the country day by day. Amid COVID-19 peak from April to June 2021 there was a huge paucity of beds and lack of appropriate treatment and drugs at hospitals during the pandemic most of the patients were unable to access proper medical care during that time and findings of current study revealed that 75.0% of the population was unable to access proper medical care during the scarcity of medical facilities.

Of total 322 participants 73.6% reported feeling of helplessness on being tested positive for COVID-19. The most probable cause for this could be self-isolation which led to changes in regular daily events such as spending time with family, close friends and loved ones. As the virus has a very high human-to-human transmission rate the threat of being infected with COVID-19 was high which was hampering the socialization of the participants and making them feel helpless.

Approximately 35.0% of the population reported lack of indulgence in any kind of physical activity during their illness might be because of symptoms of high fever, cough, and breathing difficulties, vomiting, diarrhoea, headache and body pain during COVID-19 illness which make it difficult to participate in any physical activity but 90.4% of the population reported getting enough support from family members, relatives, friends, and colleagues while 9.6% of them did not get support or help from family, relatives, friends or co-workers. Study also shows approximately 65.5% of participants used to be irritated over minor issues when asked if they were annoyed with close ones during most probably because of self-isolation which resulted in loneliness or boredom. Most of the individuals were confused about their disease, they didn’t know what was going to happen to them and their family members which made them irritated and annoyed with their close ones. Recent studies showed that mild to severe level of depression and anxiety was reported during lockdown. Non-medical professionals had considerably higher anxiety and depression scores than medical professionals because they are constantly servicing COVID-19 intensive care unit or non-COVID wards of hospitals under tremendous mental stress many of them suffer from aloneness, sadness, worry, and sleep disturbances [5,17]. The incidence of depression, anxiety, loneliness and sleep disturbances among health care providers were found to be 44.0%, 78.0%, 89.0%, and 87.0% respectively [5]. Of total 322 participants 56.2% felt the need of help or counselling to cope with mental stress during illness probably because of worsening of condition day by day due to increase in number of cases. Certain restrictions implemented by the government included not steeping from home and avoid gathering in public places all of these created havoc in the mind of people. Of total 322 participants 55.3% believes that their illness has impacted their job profile and relationships with colleagues while 44.7% believe their illness has had no impact on their job profile or relationships with colleagues. The expected reason could be because people were isolated from their friends, family, and even co-workers which resulted in an abrupt end to social connections and weakened bonds between them affecting their job profile and relationships with co-workers. Of total 322 participants 58.3% felt that they have been under pressure to meet work-related deadlines. It was possible that the COVID-19 health crisis was causing this because of its unprecedented shock that affecting people lives and livelihoods all around the world [5].

Many countries implemented widespread employment retention programs and income assistance schemes as industries forced to close operations. This has had far-reaching moments with millions of workers losing their jobs or losing livings completely which could have resulted in a financial crisis for the general public. According to this study 57.8% of population has experienced financial crisis as a result of illness.

The major epidemic and pandemic outbreaks have negative consequences for individuals and society’s mental health. According to this study 62.1% population had negative thoughts when they were in isolation. The fear of dying from a potentially fatal and incurable condition causes great misery which could have led to mental illness or exacerbate an existing psychiatric issue. COVID-19 symptoms particularly severe symptoms such as; fear of infecting others, social isolation and concerns about loss of money and future capacity to work can cause considerable mental distress that can last for a long time [18].

Of total 322 participants 62.7% addicted to binge-watching during their illness most probably because of isolation due to which the participants were in a state of boredom. This could have led excessive use of electronic gadgets and they may have addicted to binge-watching. During and after the illness period 62.1% population experienced worsening of pre-existing health conditions may be because of lack of physical activity.

Professionals are a big contributor for a country. Their mental health and quality of life plays a critical role in the growth and development of the country. The ongoing condition during the COVID-19 pandemic has created havoc and affected every individual to a great extent. Understanding the status of mental health and quality of life of working professionals during such critical crisis will aid in the development of coping strategies for the betterment of their lives as well as for country. Results from this study will aid to understand that how many Indian pursuing various types of professions were affected during the crisis of COVID-19.

The limitation of this study is that the severity of symptoms of COVID-19 were not considered as a predictor of affected mental health and quality of life, and secondly, this study has a small sample size so studies with larger sample size are required to understand the mental health and quality of life of Indian professionals in a deeper extent.

CONCLUSION

The study concludes COVID-19 pandemic to pose negative impact on few rational parameters of Mental health and quality of life among Indian professionals. The majorly impacted parameters are sleep, physical activities, emotional instability, and job profile along with support from others, mood swing and need of counselling are also impacted.

• Acknowledgements

None.

NOTES

• Authors’ contributions

M.K., K.A., N.S., A.S., S.V., G.K., A.C., K. participated in conceptualization. M.K., K.A., N.S., A.S., S.V., G.K., A.C., K. participated in data curation. K.A., N.S., A.S., M.J., S.V., G.K., A.C. performed formal analysis. M.K., K.A., N.S., S.V., G.K., A.C., K. formed methodology. M.K., K.A., A.S., M.J., S.V., G.K., A.C., K. partcipated for project administration. K.A., N.S., A.S., S.V., G.K., A.C., K. Participation in validation. K.A., N.S., A.S., S.V., G.K., A.C., K. paticipated in writing–original draft of the study. K.A., N.S., A.S., M.J., G.K., A.C., K. paticipated in writing–review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

• Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest.

• Funding

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tomar BS, Singh P, Nathiya D, Suman S, Raj P, Tripathi S, et al. Indian community's knowledge, attitude, and practice toward COVID-19. Ind J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;37(1):48–56. doi: 10.4103/ijsp.ijsp_133_20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pérez-Carbonell L, Meurling IJ, Wassermann D, Gnoni V, Leschziner G, Weighall A, et al. Impact of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on sleep. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12(Suppl 2):S163–S175. doi: 10.21037/jtd-cus-2020-015. Erratum in: J Thorac Dis 2021;13(2):1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das R, Hasan MR, Daria S, Islam MR. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health among general Bangladeshi population: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(4):e045727. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu BY, Yeung WF, Lam JC, Yuen SC, Lam SC, Chung VC, et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances during COVID-19 outbreak in an urban Chinese population: A cross-sectional study. Sleep Med. 2020;74:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Repon MAU, Pakhe SA, Quaiyum S, Das R, Daria S, Islam MR. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health among Bangladeshi healthcare professionals: A cross-sectional study. Sci Prog. 2021;104(2):368504211026409. doi: 10.1177/00368504211026409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galderisi S, Heinz A, Kastrup M, Beezhold J, Sartorius N. A proposed new definition of mental health. Psychiatr Pol. 2017;51(3):407–11. doi: 10.12740/PP/74145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haraldstad K, Wahl A, Andenæs R, Andersen JR, Andersen MH, Beisland E, et al. A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(10):2641–50. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02214-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Lei SM, Le S, Yang Y, Zhang B, Yao W, et al. Bidirectional influence of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns on health behaviors and quality of life among Chinese adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5575. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franceschini C, Musetti A, Zenesini C, Palagini L, Scarpelli S, Quattropani MC, et al. Poor sleep quality and its consequences on mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Front Psychol. 2020;11:574475. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.574475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faulkner S, Bee P. Perspectives on sleep, sleep problems, and their treatment, in people with serious mental illnesses: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazza MG, De Lorenzo R, Conte C, Poletti S, Vai B, Bollettini I, et al. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grosso LJ, Goode LD, Kimball HR, Kooker DJ, Jacobs C, Lattie G. The subspecialization rate of third year internal medicine residents from 1992 through 1998. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16(1):7–13. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1601_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathur R, Swaminathan S. National ethical guidelines for biomedical & health research involving human participants, 2017: A commentary. Indian J Med Res. 2018;148(3):279–83. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.245303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu F, Wang X, Yang Y, Zhang K, Shi Y, Xia L, et al. Depression and insomnia in COVID-19 survivors: A cross-sectional survey from Chinese rehabilitation centers in Anhui province. Sleep Med. 2022;91:161–5. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandelkorn U, Genzer S, Choshen-Hillel S, Reiter J, Meira E Cruz M, Hochner H, et al. Escalation of sleep disturbances amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional international study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(1):45–53. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terry PC, Parsons-Smith RL, Terry VR. Mood responses associated with COVID-19 restrictions. Front Psychol. 2020;11:589598. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.589598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hummel S, Oetjen N, Du J, Posenato E, Resende de Almeida RM, Losada R, et al. Mental health among medical professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in eight European countries: Cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1):e24983. doi: 10.2196/24983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sher L. Post-COVID syndrome and suicide risk. QJM. 2021;114(2):95–8. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcab007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]