Abstract

Objective:

Chronic illness in children and adolescents is associated with significant stress and risk of psychosocial problems. In busy pediatric clinics, limited time and resources are significant barriers to providing mental health assessment for every child. A brief, real-time self-report measure of psychosocial problems is needed.

Methods:

An electronic distress screening tool, Checking IN, for ages 8–21 was developed in 3 phases. Phase I used semi-structured cognitive interviews (N = 47) to test the wording of items assessing emotional, physical, social, practical, and spiritual concerns of pediatric patients. Findings informed the development of the final measure and an electronic platform (Phase II). Phase III used semi-structured interviews (N = 134) to assess child, caregiver and researcher perception of the feasibility, acceptability, and barriers of administering Checking IN in the outpatient setting at 4 sites.

Results:

Most patients and caregivers rated Checking IN as “easy” or “very easy” to complete, “feasible” or “somewhat feasible,” and the time to complete the measure as acceptable. Most providers (n = 68) reported Checking IN elicited clinically useful and novel information. Fifty-four percent changed care for their patient based on the results.

Conclusions:

Checking IN is a versatile and brief distress screener that is acceptable to youth with chronic illness and feasible to administer. The summary report provides immediate clinically meaningful data. Electronic tools like Checking IN can capture a child’s current psychosocial wellbeing in a standardized, consistent, and useful way, while allowing for the automation of triaging referrals and psychosocial documentation during outpatient visits.

Keywords: children, adolescents, chronic illness, distress screening, electronic, psychosocial, outpatient care

Advances in pediatric disease prevention, detection, and treatment have dramatically increased rates of survival of children with cancer and other life-limiting illnesses. Unfortunately, these developments have not erased the challenges of the treatment regimens, adverse effects, and disruptions to daily life that these children often face. Over the trajectory of their disease, children with serious illnesses are exposed to numerous, varied emotional and behavioral stressors that may significantly impact their overall quality of life. In particular, seriously ill children can experience major chronic stressors resulting from their traumatic reactions to repeated procedures or hospitalizations. Anxiety, depression, fatigue, difficulty with peers, and poor academic progress, poor body image, and difficulty with medication adherence have been reported (Nijhof et al., 2021; Sansom-Daly & Wakefield, 2013; Wakefield et al., 2010; Wiener et al., 2017).

While children are closely observed by their healthcare providers during inpatient stays, the outpatient setting does not afford the same opportunity for careful observation, such that manifestations of emotional and behavioral distress may be missed by healthcare providers and opportunities for provision of appropriate referrals lost. In pediatric oncology, routine screening and assessment for psychosocial stressors is an evidence-based Standard of Care supported by 149 studies (Kazak et al., 2015), yet lack of staff and resources is an often documented barrier to meeting this Standard (Barrera et al., 2018; Kazak et al., 2017; McCarthy et al., 2016; Schepers et al., 2017). Other organizational barriers to routine psychosocial distress screening in pediatric outpatient settings include potential burden on patients and their caregivers and distribution of findings in a timely manner (Schepers, Haverman, Zadeh, Grootenhuis, Wiener, 2016). Even when routine screenings do take place, most assessments are limited to caregiver report, limiting any insight into the child’s experience (Deighton et al., 2014).

Child friendly, engaging, and easy to administer patient reported distress screening with validated tools is one way to quickly identify children who are experiencing psychosocial distress. An earlier study assessed the validity, inter-rater reliability, and sensitivity/specificity of a pediatric distress thermometer (DT) with medically ill youth ages 7–21 (Wiener et al., 2017). The study also assessed the acceptability and feasibility of administering the DT with two hundred eighty-one patient–caregiver–provider triads in the outpatient setting. Using the checklist items most often endorsed on the DT and an adjusted age range based on item comprehension, a next generation electronic distress screening tool, Checking IN was developed for youth 8–21 years of age. Checking IN builds upon the DT to capture important details regarding patients’ mental health, and has been designed for enhanced screening sensitivity as well as electronic administration, thus incorporating lessons learned from the extant literature to create a novel, acceptable, and ultimately beneficial screener appropriate for the pediatric outpatient setting (Gilleland Marchak et al., 2021; Schepers et al., 2017; Wiener et al., 2017). The development of Checking IN took part in 3 phases. Given the challenges of comprehension across a broad developmental period, the first phase used semi-structured cognitive interviews (Willis, 2010) to test/refine and ensure comprehension of the items assessing emotional, physical, social, practical, and spiritual concerns of pediatric patients in different age groupings. The results from Phase I informed the development of the final measure, which was then built within an electronic platform (Phase II). This paper focuses primarily on the results of Phase III; child, caregiver and research administrator perception of the feasibility, acceptability, and barriers of administering Checking IN in the outpatient setting.

Method

Participants

Eligible participants were 8–21 years old, able to speak and read English, receiving outpatient care for cancer or another chronic illness, and had a parent/caregiver available to complete the study measures. Data for Phase I was collected at the NIH Clinical Center between 2016–2018. The electronic screen was developed in 2018 (Phase II) and pilot tested for further refinement in 2019. Data for Phase III was collected at 4 hospital centers between 2020–2021. All caregivers and patients 18 years of age and older provided written informed consent, and children and adolescents <18 years provided assent. No compensation was provided. The study was approved by the NIMH Institutional Review Board and the IRB at each of the participating sites.

Study Procedures

Phase 1:

In-depth 1–1 cognitive interviews were conducted by clinicians (LW, SZB) with 3 age groups (i.e., 8–12; 13–17; 18–21) to evaluate each youth’s comprehension to the Checking IN items. The semi-structured interview guide utilized cognitive interview techniques (Willis, 2010) and was refined by a multi-disciplinary group of researchers and clinicians. Participants completed a paper version of Checking IN and were then asked 5 follow-up questions per item to test the accuracy and quality of each: 1) “What do you think this question is asking?”; 2) “Was this question easy to understand?”; 3) “How would you change the words to make it easier to understand?”; 4) “Was this item hard to answer?”; and 5) “How did you choose your answer?”

To test the response choices, each child was asked to explain why they chose their answers, whether the choices helped describe why each symptom has been a problem for them, and how they would make the choices more clear/easier to understand. To determine participants’ comprehension of the recall period (i.e., “the past 7 days”) and their ability to accurately identify events within that time, the child was asked 4 questions: 1) What does “in the last 7 days” mean to you?; 2) When you see “in the last 7 days”, what days did you include?; 3) What symptoms did you experience in the past 7 days vs the past month?; and 4) Which is easier to respond to, symptoms “in the past 7 days” or symptoms in the past week? Phase I results were used to further refine the items selected for Checking IN.

Phase II:

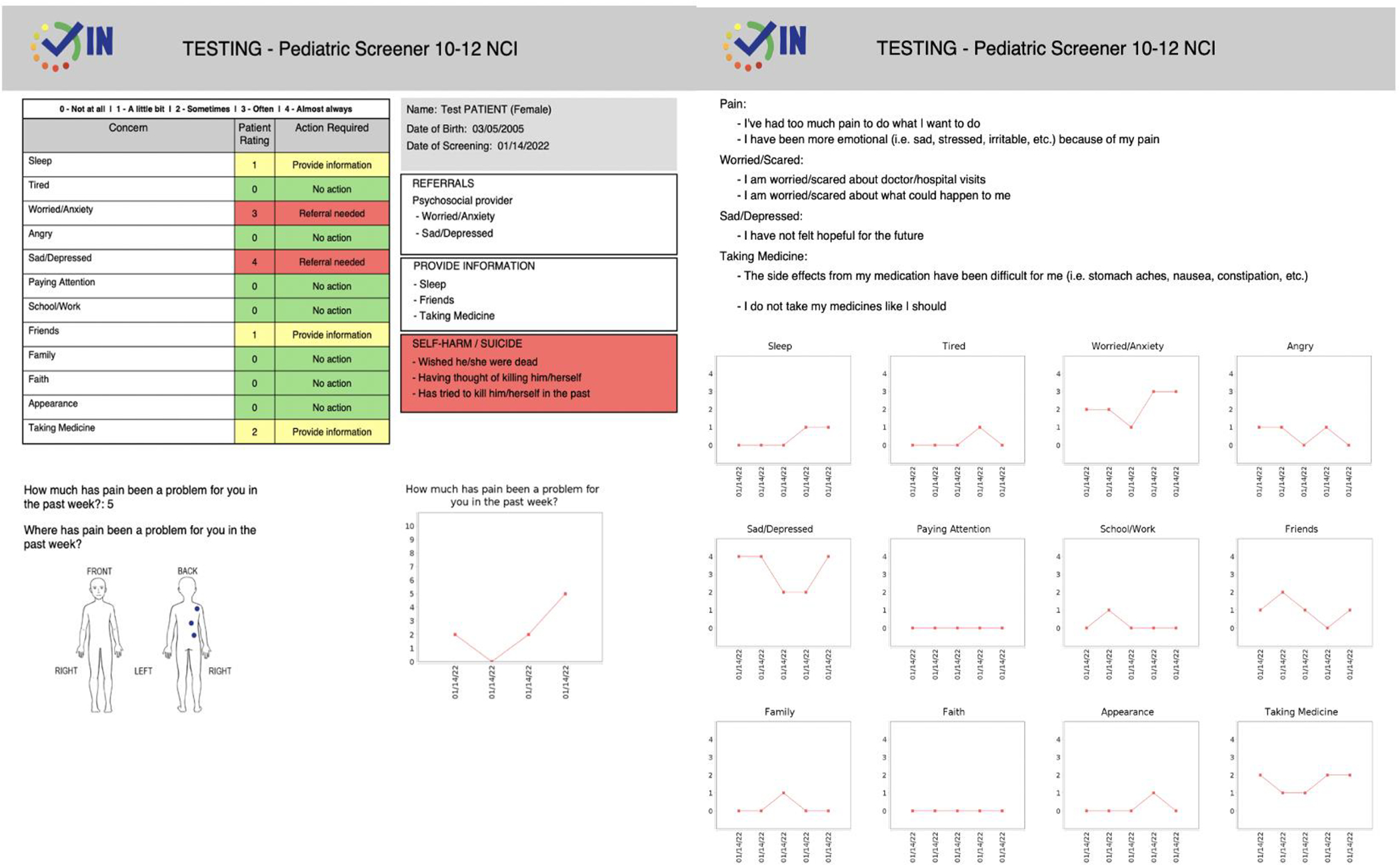

We collaborated with Patient Planning Services, a technology subsidiary of the Cancer Support Community. They developed the electronic versions of Checking IN and created an automated provider summary report (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Provider Summary Report

Phase III:

Patients (ages 8–21) and their caregivers were each given a tablet or laptop by a study investigator and were asked to complete an age-specific version of Checking IN. All study investigators were clinicians who helped ensure that the patient and caregiver completed responses independently. Patients and their caregivers were then administered a brief questionnaire that assessed how feasible and acceptable they found Checking IN to complete. The administering study investigator also completed a brief questionnaire rating the feasibility of administration and all barriers encountered, as well as the amount of support the patient and caregiver needed from them to complete Checking IN (Supplemental Tables 1–3). Finally, medical providers were given the Checking IN summary report and asked to complete a survey to evaluate its utility. Providers indicated whether the information in the report was 1) clinically important, 2) presented in a user-friendly manner, and 3) impacted or changed the care provided for the child. Providers also gave feedback on the format and content of the summary report. Demographic information, including medical diagnosis, was collected as part of the measure.

Measures (collected during phase III of the study)

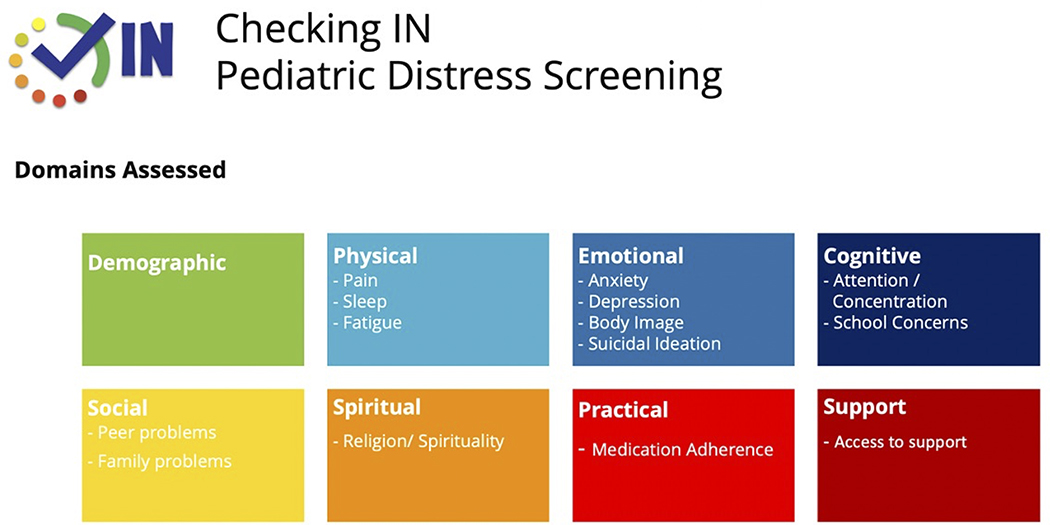

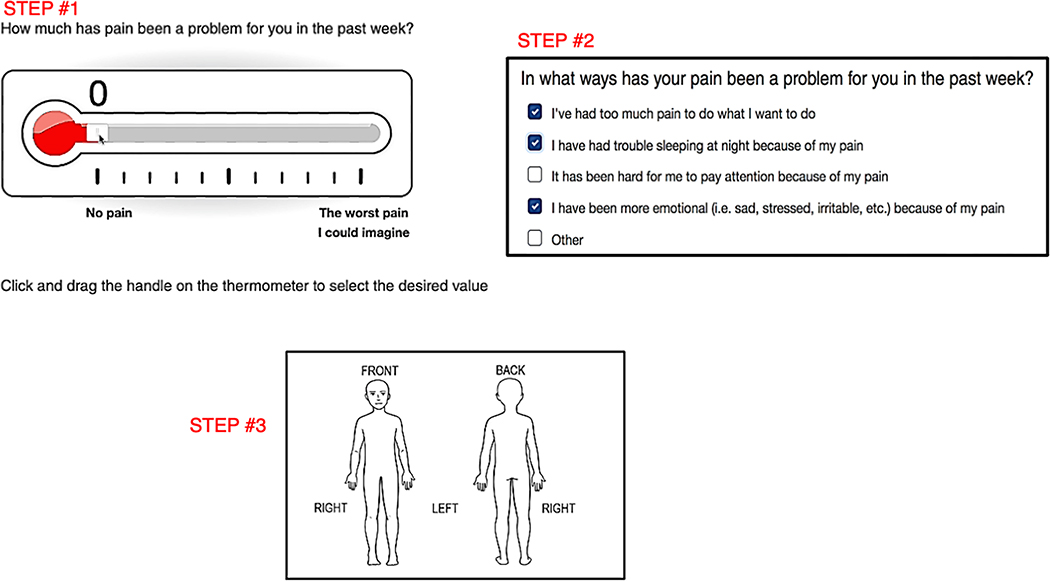

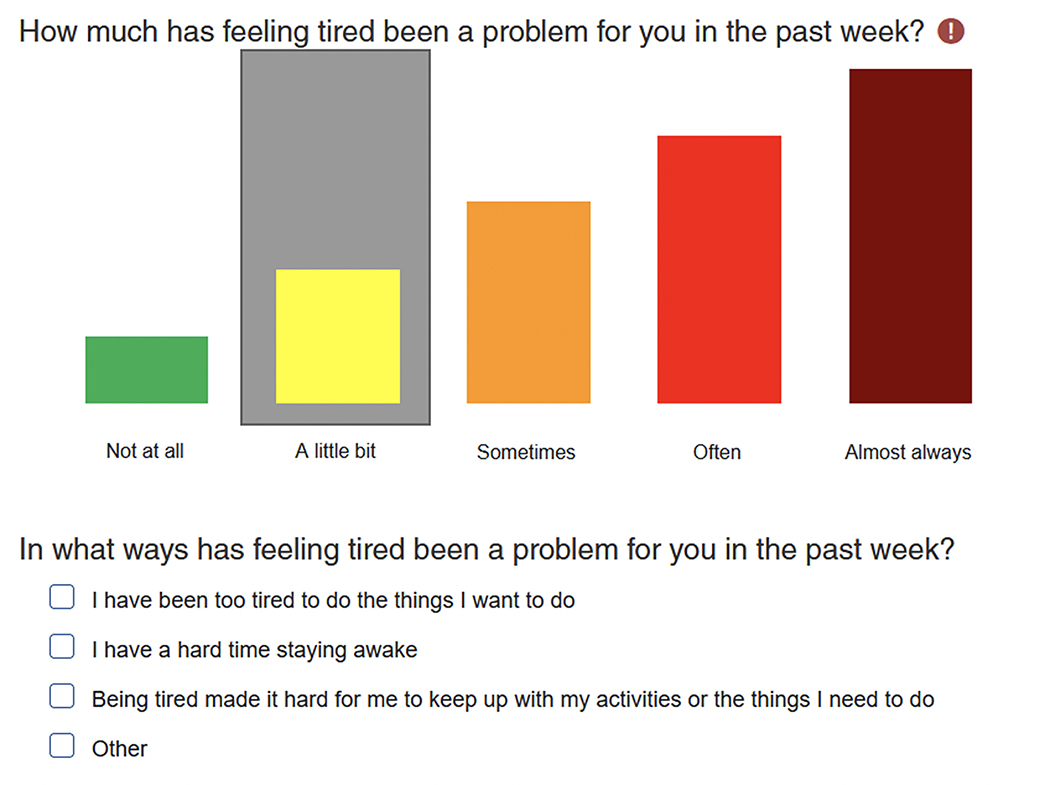

Checking IN: Checking IN consists of 6 problem areas that cover 12 different domains (Figure 2). To better appreciate the pain experience given its significant potential impact on psychosocial functioning, level of disability and dependency (Jibb et al., 2015; Simons et al., 2018), a front and back drawing of a body is included on which participants mark where in the body they are experiencing pain (Figure 3). To obtain the most clinically useful data and to focus on symptoms that interfere most with the child’s quality of life, each domain assessed within Checking IN begins with, “Has [domain] been a problem for you in the past week”. Response options include “Not at all”, “A little bit”, “Sometimes”, “Often”, and “Almost Always”. If “Not at all” is endorsed, branching logic skips to the next domain. For all other responses, a set of 3–7 checkbox items appear, allowing the participant to specify ways that the symptom has been problematic (See example in Figure 4). An “other” option is also provided with free text space in the event the reason for the domain being problematic is not captured. Given that 9% of youth endorsed suicidal ideation on the Children’s Depression Inventory in the previous validation of the DT (Wiener et al., 2017), we embedded the Ask Suicide-Screening (ASQ; (Horowitz et al., 2020)), an evidence-based 4-item suicide screen, within Checking IN for patients ages ≥10.

Figure 2.

Domains Assessed

Figure 3.

Checking IN Pain Assessment

Figure 4.

Example of Colored Response Bars and Checkbox Items

Feasibility and Acceptability

Patients and caregivers were asked “how easy was it to complete Checking IN?” with response options provided on a 4-point scale (“very easy,” “easy,” “hard,” or “very hard”). Other specific items included: 1) the ease of navigating the response options (e.g., colored response bars, a glider to indicate degree of pain, and illustrating pain location, 2) the ease of describing why a particular domain has been a problem in the past week, 3) whether the amount of time it took to complete Checking IN was “too long”, “too short”, or “OK”, and 4) if they would be comfortable completing Checking IN each time they returned for a medical appointment. Patients 10 years of age and older and their caregivers were asked their perspectives of being asked questions about self-harm and suicide risk in the outpatient setting.

Researcher Feasibility Form

The researcher who administered Checking IN to the patient and caregiver completed a brief feasibility survey using a 4-point scale: “very feasible,” “somewhat feasible,” “somewhat unfeasible” and “unfeasible”. They were also asked about the amount of support participants needed to complete the screen. Researchers documented the difficulty patients had reading/understanding the items or answering the questions, issues associated with electronic administration, or any concerns about the items.

Data Analyses

Descriptive analyses were calculated to characterize the demographic and medical variability of the sample. Responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics, adjusting the sample size as appropriate based on the proportion of participants to whom each item/domain was posed. Analyses were conducted using SPSS 28 software.

If the percent of responses from pediatric participants indicating that Checking IN was difficult to complete (“somewhat hard” or “very hard”) exceeded 25%, Checking IN was deemed to have low acceptability. Recommended changes to Checking IN (e.g., colors, font) were analyzed descriptively. Questions related to Checking IN by primary caregivers and medical providers and its feasibility in a clinical setting were explored for common themes. If more than 25% of administrations in any of the settings were ranked “somewhat unfeasible” or “unfeasible”, the instrument was considered not feasible for use in the pediatric outpatient setting. All responses other than “very feasible”, were descriptively reported.

Results

Phase 1: Cognitive Interviews

Forty-seven (47) children aged 8 to 21 (M = 13.47 years, SD = 3.97) participated in Phase I of the study. To determine if different versions of Checking IN were needed, we focused on interviewing children in 3 age groups: 8–12 years (N = 22, 46.8%), 13–17 years (N = 15, 31.9%), and 18–21 years (N = 10, 21.3%). One child did not complete the interview and was excluded from the analyses. Diagnoses of participants included cancer (33.3%) and NF1 (66.6%) as these were the patients receiving care in our pediatric clinic during the study period. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Description of Sample in Phase I and Phase III

| Phase I | Phase III | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N (%) | N (%) |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 25 (53.2%) | 67 (50.0%) |

| Male | 22 (46.8%) | 66 (49.3%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) |

|

| ||

| Age | ||

| 8–9 years old | 10 (21.3%) | 25 (18.7%) |

| 10–12 years old | 11 (23.4%) | 28 (20.9%) |

| 13–17 years old | 16 (34.0%) | 50 (37.3%) |

| 18–21 years old | 10 (21.3%) | 31 (23.1%) |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 35 (74.4%) | 102 (76.2%) |

| Black/African American | 6 (12.8%) | 17 (12.7%) |

| Asian | 0 (0%) | 8 (6.0%) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 3 (6.4%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (2.1%) | 2 (1.5%) |

| Biracial | 0 (0%) | 3 (2.2%) |

| Missing | 2 (4.3%) | 1 (0.7%) |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino/a | 7 (14.9%) | 13 (9.7%) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino/a | 39 (83.0%) | 118 (88.1%) |

| Missing | 1 (2.1%) | 3 (2.2%) |

|

| ||

| Medical Diagnosis | ||

| Cancer | 17 (36.2%) | 88 (65.7%) |

| Other | ||

| Primary Immune Deficiency | 0 (0%) | 9 (6.7%) |

| Neurofibromatosis Type 1 | 29 (61.7%) | 32 (23.9%) |

| Sickle Cell Disease | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Missing | 1 (2.1%) | 4 (3.0%) |

Cognitive interviewing helped identify the items and/or wording that patients found unclear or confusing, with several wording changes suggested across age groups. These included a need to 1) differentiate between problems falling asleep versus staying asleep, 2) utilize more understandable language describing cognitive issues, 3) clarify differences between physical and emotional difficulties, 4) include items unrelated to physical problems (e.g., pill swallowing difficulties/side effects) when assessing for adherence challenges, and 5) label the body image (i.e., front/back, left/right) to provide more clarity where in the body pain is experienced. Other suggestions for the design, formatting, and response options were incorporated, such as adding color to supplement response options. As the participants were often confused by the phrasing “past 7 days” and were better able to report symptoms when “the past week” was used, this change was also made.

When feedback became consistent and no new information was being obtained, we completed Phase I of the study. Checking IN was revised based on item comprehension, resulting in a specific version for children aged 8–9, 10–12, and 13–21, along with a corresponding caregiver proxy tool with parallel items. Self-harm and suicide screening was included in the versions for youth 10 years of age and older.

Phase 2: Development of the Electronic Screen

We collaborated with Patient Planning Services, a technology subsidiary of the Cancer Support Community who developed the platform for 3 electronic versions of Checking IN and the provider summary reports.

Phase 3: Feasibility and Acceptability

One hundred thirty-four (134) participants aged 8 to 21 (M=13.98 years, SD=4.03) and their caregiver were included in this phase of the study. Response rate across sites was 75%. Reasons for declining participation including lack of interest in participating in an additional study or a study without compensation, not feeling well, and lack of time during a busy clinic day. Demographic information of participants is provided in Table 1.

The amount of time to complete Checking In averaged 15 minutes for children ages 8–9 and 13 minutes for their caregivers. For youth ages 10–21, the average time to complete Checking IN was 13 minutes and 11 minutes for their caregivers. Most participants rated Checking IN as “easy” or “very easy” to complete (Children: 98.3%; Caregivers: 99.1%) and the amount of time needed to complete the measure as acceptable (Children: 93.1%; Caregivers: 81.7%). Participants largely rated the colored response bars used to assess the Checking IN domains on a Likert scale as easy to use (Children: 97.8%; Caregivers: 97.0%). As previously described, if a participant responds to any domain with anything other than “Not at all,” a series of checkbox prompts are generated to facilitate clarifying how that domain has been a problem. To assess the feasibility of this checkbox structure, participants were asked “Were the checkbox items easy to use?”. Again, the vast majority indicated ease of use (Children: 95.5%; Caregivers: 97.0%), though many asked for the font size to be increased.

The items on pain received the most feedback. When asked “Was the pain thermometer easy to use to describe how much pain you’ve (your child has) had?” 82.8% of children and 79.9% of caregivers said yes and 11.2% of children and 10.4% of caregivers responded “n/a” since there was no pain to report. Of those who indicated the pain thermometer was not easy to use (Children: 6.0%; Caregivers: 9.0%), participants noted a need for more clear instructions, technical difficulties, or difficulty assigning a number to a whole week’s time. Participants who endorse experiencing any pain are prompted to indicate where they experience pain by digitally marking a front and back image of a human body. Most participants found this process easy to do (Children: 73.13%; Caregivers: 72.4%). Those who found this process “not easy” (Children: 17.2%; Caregivers: 17.2%) noted difficulties with the technical process (e.g., accurately placing the mark, using the undo feature).

Among youth aged 10 and up to whom questions about self-harm and suicidal ideation were posed, most felt that asking these questions was appropriate (Children: 88.1%; Caregivers: 97.2%). A slim majority of youth reported that they had been asked about suicide directly in the past (60%). Most participants endorsed feeling comfortable repeating the screener at future follow-up appointments (Children: 84%; Caregivers: 92.2%).

During monthly study site meetings, areas not currently assessed within Checking IN that have been shown to cause stress to youth aged 13–21 were considered important to include. In response, the relevant version has been updated to include a checklist on which youth can indicate additional topics to address, such as gender identity and substance use.

Researcher Feasibility

Researchers were asked to rate “How feasible was it to administer Checking IN to the patient/caregiver in a pediatric outpatient setting?” on a scale of “very feasible,” “somewhat feasible,” “somewhat unfeasible,” to “unfeasible.” The majority indicated that it was very feasible (Children: 74.6%; Caregivers: 83.6%) or “somewhat feasible” (Children: 21.6%; Caregivers: 13.4%), with only one researcher noting the administration was “somewhat unfeasible” due to interruptions by nursing staff.

Provider Feedback

Most providers (N = 68) reported Checking IN elicited clinically useful (97.7%) and novel (59.4%) information from their patients. Fifty-six percent (56.1%) changed care for their patient based on the screener results and of these, 87.1% provided additional discussion with patient and parent, 14.5% made additional referrals they were not previously planning, and 14.5% reported other interventions including changing medications and reviewing sleep/hygiene.

Discussion

Given the acute, chronic, and long-term stressors associated wth the diagnosis, treatment, and condition management that youth living with a serious illness can have (Compas et al., 2012) and how these stressors can be missed during busy outpatient visits, distress screening can provide important clinical information. Checking IN, a brief electronic distress screening tool, assesses for physical pain, sleep, and fatigue; anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation and body image concerns; peer, school/work and cognitive problems, family problems; medication adherence and access to support. Our findings demonstrate that youth receiving treatment in the outpatient setting and their caregivers are willing and able to self-report on these domains. Checking IN was found to be acceptable to both youth and their caregivers, and feasible to implement in the outpatient setting.

Checking IN provides medical and psychosocial providers real-time feedback, which allows for triage of the highest acuity patients, and for a tailored/personalized intervention plan to be created based on real-time patient voice and caregiver feedback. For example, the receipt of electronic patient-reported data from Checking IN has the potential to improve treatment adherence by identifying the self- and caregiver endorsed barriers to taking mediation. The real-time data can also be translated into opportunities to address other patient or caregiver identified concerns instead of waiting for the patient or caregiver to report them (Weaver & Wiener, 2021).

While this was an acceptability and feasibility study, and information was obtained in a highly monitored context, we found that the technology generated summary report with Checking IN fostered real-time clinical awareness and the opportunity for prompt responses. The automated tracking of endorsed domains over the past 5 visits also provides clear identification of trends, problem areas, and psychosocial risks.

It has been speculated that child and adolescent patients might not want or are unwilling to communicate with their parents or medical providers about psychosocial concerns for various reasons, such as not wanting to increase their parents’ worries and/or wanting to be good patients (Lai et al., 2020). Parents can be unaware of the specific difficulties that their children face and discordance between parent and child reports is common (Theunissen et al., 1998; Wiener et al., 2014; Wiener et al., 2017). Parents more accurately report on their child’s observable problems (e.g., mobility), but are less aware of the severity of their child’s internalizing symptoms (Varni et al., 2015). Hence, obtaining both the child and caregiver voice across multiple domains can capture the most comprehensive assessment of the child’s psychosocial wellbeing (Martin et al., 2020). While we found that the youth and caregivers that participated in this study were willing to share their psychosocial concerns via an electronic screen, further work is needed to address potential barriers to integrating a screening tool such a Checking IN into a clinic workflow. Considerations to be addressed include time constraints, the unpredictability in knowing if (and when) providers will read the symptom report, and whether the findings are integrated within the electronic medical record (EMR) (Leahy et al., 2021).

The strengths of the present study were the rigorous multi-steps taken to generate the items and develop and assess the feasibility and acceptability of Checking IN. The items are based on the concerns of individual children, ages 8–17, not just caregiver report, the latter of whom may not be aware of the child’s personal concerns. Additionally, youth from 4 different settings, with varied medical conditions were included in the development of Checking IN.

Despite these strengths, several limitations are important to note. First, we currently only have an English version of Checking IN and interviews did not include Spanish speaking participants (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). As children and caregivers from different cultural backgrounds may have different perspectives and practices surrounding reporting on emotional symptoms or family distress (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005), our lack of diversity limits the generalizability of the findings. Second, the majority of caregivers were female and biological parents. Male perspectives and the inclusion of other types of caregivers (e.g., grandparents) along with greater ethnic diversity, may provide additional breath to the feasibility and acceptability of Checking IN. Third, we do not know whether the time to complete Checking IN would be different outside of the research setting. Comments from the researcher (e.g., answering study questions) suggests that the time to complete the tool in the clinic setting would be shorter than what was documented. Fourth, we did not assess the developmental abilities of the study participants. Along with work to be done to realize the potential benefits of using distress screening for children in general, further investigation regarding the feasibility and usefulness of distress screening for youth with neurocognitive and developmental disabilities is warranted (Huang et al., 2014). An audio option within Checking IN is currently in development. Finally, although neither the specific items endorsed, nor the discordance between child and caregiver reports, are included in this paper, the differences between self- and proxy-report on measures of distress and quality of life have been well-documented, with arguments made emphasizing the value of both reporters, with the child’s voice being considered paramount (Lai et al., 2007; Leahy & Steineck, 2020; Mack et al., 2020; Sheffler et al., 2009; Theunissen et al., 1998; Wiener et al., 2014; Wiener et al., 2017). This is especially true for suicide screening. Further research is needed to develop standard operating procedures for resolving discordant information and to effectively integrate this type of information into the clinical workflow.

Validation of Checking IN is an important next step. However, we suggest caution in choosing the measures with which to validate Checking IN. Checking IN asks about domains that have been a problem for the patient over the past week. It does not ask whether the symptom exists. For example, the PROMIS pediatric anxiety scale asks: In the past 7 days …. “I have felt nervous” whereas, Checking IN asks: “How much has feeling anxious or worried been a problem for you in the past week?” An exception is the PROMIS measure on pain interference which inquires about how the symptom is interfering with the child’s life (e.g., In the past 7 days, “I had trouble sleeping when I had pain”. Moreover, aside from the Distress Thermometer, no other pediatric distress screening tools are publicly available. A future study could consider comparing specific domains of Checking IN with the same domains on a quality-of-life measure, such as the PedsQL, which does ask about domains that are a problem for the child. Checking IN also does not assess parent distress or a parent’s report of family psychosocial concerns. Therefore, complementing Checking IN with other evidence-based psychosocial assessment tools, such as the PAT (Kazak et al., 2018), might provide a more comprehensive assessment of a child and family needs.

In conclusion, the present study describes the development in a cognitively and developmentally sensitive-manner and pilot-testing of the acceptability, feasibility, and barriers to a newly developed electronic distress screening tool. Our data provides evidence that Checking IN is acceptable to youth living with a chronic illness and their caregiver and feasible to administer in the outpatient setting. The electronic screening tool has been designed for ease of administration with patient-reported information via a summary report providing added value with immediate results and clinically meaningful data that was found to impact care. As the majority of youth and their caregivers endorsed being comfortable with repeated administration of Checking IN, this lends itself well for longitudinal use in pediatric outpatient settings. Patient- and caregiver reported screening tools, such as Checking IN, used in a standard manner with children receiving treatment for a chronic condition may be the best way to facilitate early recognition of psychosocial distress, enhance communication with the treatment team (Bradford et al., 2021), increase family engagement in care (Takeuchi et al., 2011; Wolfe et al., 2014), and ultimately lead to better clinical outcomes (Leahy & Steineck, 2020).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

This work was supported, in part, by the Intramural Programs of the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Mental Health (ZIA-MH002922-13) at the National Institutes of Health. We thank our technology development collaborators, Cate O’Reilly, MSW, Peyton Lengacher and Damian Piccolo, MSC. IT, MBA at Patient Planning Services, a Cancer Support Community subsidiary for their time, effort and expertise in developing the electronic platform of Checking IN and the introduction by Vicki Kennedy, LCSW to the Cancer Support Community which led to this collaboration. We are grateful to Dr. Marina Colli, PhD and Ms. Julia Tager, BS for their assistance with data collection during Phase I of the study and to Drs. Kelly Scherger and Laura Reiman for data collection at their sites. We thank Samantha Holden for illustrating the drawings of the body figure used in Checking IN.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement. The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT NCT02423031

Contributor Information

Lori Wiener, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Sima Z. Bedoya, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland

Mallorie Gordon, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Abigail Fry, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Robert Casey, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, Colorado.

Amii Steele, Levine Children’s Hospital, Charlotte, North Carolina.

Kathy Ruble, The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Devon Ciampa, The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Maryland Pao, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

References

- Barrera M, Alexander S, Shama W, Mills D, Desjardins L, & Hancock K (2018, Dec). Perceived benefits of and barriers to psychosocial risk screening in pediatric oncology by health care providers. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 65(12), e27429. 10.1002/pbc.27429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford NK, Bowers A, Chan RJ, Walker R, Herbert A, Cashion C, Condon P, & Yates P (2021, Nov-Dec 01). Documentation of Symptoms in Children Newly Diagnosed With Cancer Highlights the Need for Routine Assessment Using Self-report. Cancer Nursing, 44(6), 443–452. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Jaser SS, Dunn MJ, & Rodriguez EM (2012). Coping with chronic illness in childhood and adolescence. Annu Rev Clin Psychol, 8, 455–480. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, & Kazdin AE (2005, Jul). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: a critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychol Bull, 131(4), 483–509. 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deighton J, Croudace T, Fonagy P, Brown J, Patalay P, & Wolpert M (2014). Measuring mental health and wellbeing outcomes for children and adolescents to inform practice and policy: a review of child self-report measures. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health, 8, 14. 10.1186/1753-2000-8-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilleland Marchak J, Halpin SN, Escoffery C, Owolabi S, Mertens AC, & Wasilewski-Masker K (2021). Using formative evaluation to plan for electronic psychosocial screening in pediatric oncology. Psycho-Oncology, 30(2), 202–211. 10.1002/pon.5550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LM, Wharff EA, Mournet AM, Ross AM, McBee-Strayer S, He JP, Lanzillo EC, White E, Bergdoll E, Powell DS, Solages M, Merikangas KR, Pao M, & Bridge JA (2020, Sep). Validation and Feasibility of the ASQ Among Pediatric Medical and Surgical Inpatients. Hosp Pediatr, 10(9), 750–757. 10.1542/hpeds.2020-0087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang IC, Revicki DA, & Schwartz CE (2014, Apr). Measuring pediatric patient-reported outcomes: good progress but a long way to go. Quality of Life Research, 23(3), 747–750. 10.1007/s11136-013-0607-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jibb LA, Nathan PC, Stevens BJ, Seto E, Cafazzo JA, Stephens N, Yohannes L, & Stinson JN (2015, Nov). Psychological and Physical Interventions for the Management of Cancer-Related Pain in Pediatric and Young Adult Patients: An Integrative Review. Oncol Nurs Forum, 42(6), E339–357. 10.1188/15.Onf.E339-e357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak AE, Abrams AN, Banks J, Christofferson J, DiDonato S, Grootenhuis MA, Kabour M, Madan-Swain A, Patel SK, Zadeh S, & Kupst MJ (2015, Dec). Psychosocial Assessment as a Standard of Care in Pediatric Cancer. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 62 Suppl 5, S426–459. 10.1002/pbc.25730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak AE, Barakat LP, Askins MA, McCafferty M, Lattomus A, Ruppe N, & Deatrick J (2017, Jul 1). Provider Perspectives on the Implementation of Psychosocial Risk Screening in Pediatric Cancer. J Pediatr Psychol, 42(6), 700–710. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsw110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak AE, Hwang WT, Chen FF, Askins MA, Carlson O, Argueta-Ortiz F, & Barakat LP (2018, Aug 1). Screening for Family Psychosocial Risk in Pediatric Cancer: Validation of the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) Version 3. J Pediatr Psychol, 43(7), 737–748. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsy012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai JS, Beaumont JL, Kupst MJ, Peipert JD, Cella D, Fisher AP, & Goldman S (2020, Jul 15). Symptom burden trajectories experienced by patients with brain tumors. Cancer, 126(14), 3341–3351. 10.1002/cncr.32879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai JS, Cella D, Kupst MJ, Holm S, Kelly ME, Bode RK, & Goldman S (2007, Jul). Measuring fatigue for children with cancer: development and validation of the pediatric Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (pedsFACIT-F). J Pediatr Hematol Oncol, 29(7), 471–479. 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318095057a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahy AB, Schwartz LA, Li Y, Reeve BB, Bekelman JE, Aplenc R, & Basch EM (2021, Aug 15). Electronic symptom monitoring in pediatric patients hospitalized for chemotherapy. Cancer, 127(16), 2980–2989. 10.1002/cncr.33617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahy AB, & Steineck A (2020, Nov 1). Patient-Reported Outcomes in Pediatric Oncology: The Patient Voice as a Gold Standard. Jama Pediatrics, 174(11), e202868. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack JW, McFatrich M, Withycombe JS, Maurer SH, Jacobs SS, Lin L, Lucas NR, Baker JN, Mann CM, Sung L, Tomlinson D, Hinds PS, & Reeve BB (2020, Nov 1). Agreement Between Child Self-report and Caregiver-Proxy Report for Symptoms and Functioning of Children Undergoing Cancer Treatment. Jama Pediatrics, 174(11), e202861. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SR, Zeltzer LK, Seidman LC, Allyn KE, & Payne LA (2020, May 1). Caregiver-Child Discrepancies in Reports of Child Emotional Symptoms in Pediatric Chronic Pain. J Pediatr Psychol, 45(4), 359–369. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsz098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MC, Wakefield CE, DeGraves S, Bowden M, Eyles D, & Williams LK (2016, Sep-Oct). Feasibility of clinical psychosocial screening in pediatric oncology: Implementing the PAT2.0. J Psychosoc Oncol, 34(5), 363–375. 10.1080/07347332.2016.1210273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhof LN, van Brussel M, Pots EM, van Litsenburg RRL, van de Putte EM, van Montfrans JM, & Nijhof SL (2021, Aug). Severe Fatigue Is Common Among Pediatric Patients with Primary Immunodeficiency and Is Not Related to Disease Activity. J Clin Immunol, 41(6), 1198–1207. 10.1007/s10875-021-01013-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom-Daly UM, & Wakefield CE (2013, Oct). Distress and adjustment among adolescents and young adults with cancer: an empirical and conceptual review. Transl Pediatr, 2(4), 167–197. 10.3978/j.issn.2224-4336.2013.10.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepers SA, Sint Nicolaas SM, Haverman L, Wensing M, Schouten van Meeteren AYN, Veening MA, Caron HN, Hoogerbrugge PM, Kaspers GJL, Verhaak CM, & Grootenhuis MA (2017, Jul). Real-world implementation of electronic patient-reported outcomes in outpatient pediatric cancer care. Psycho-Oncology, 26(7), 951–959. 10.1002/pon.4242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffler LC, Hanley C, Bagley A, Molitor F, & James MA (2009, Dec). Comparison of self-reports and parent proxy-reports of function and quality of life of children with below-the-elbow deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 91(12), 2852–2859. 10.2106/JBJS.H.01108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons LE, Sieberg CB, Conroy C, Randall ET, Shulman J, Borsook D, Berde C, Sethna NF, & Logan DE (2018, Feb). Children With Chronic Pain: Response Trajectories After Intensive Pain Rehabilitation Treatment. J Pain, 19(2), 207–218. 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi EE, Keding A, Awad N, Hofmann U, Campbell LJ, Selby PJ, Brown JM, & Velikova G (2011, Jul 20). Impact of patient-reported outcomes in oncology: a longitudinal analysis of patient-physician communication. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29(21), 2910–2917. 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theunissen NC, Vogels TG, Koopman HM, Verrips GH, Zwinderman KA, Verloove-Vanhorick SP, & Wit JM (1998, Jul). The proxy problem: child report versus parent report in health-related quality of life research. Quality of Life Research, 7(5), 387–397. 10.1023/a:1008801802877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Thissen D, Stucky BD, Liu Y, Magnus B, He J, DeWitt EM, Irwin DE, Lai JS, Amtmann D, & DeWalt DA (2015, Aug). Item-level informant discrepancies between children and their parents on the PROMIS((R)) pediatric scales. Quality of Life Research, 24(8), 1921–1937. 10.1007/s11136-014-0914-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield CE, McLoone J, Goodenough B, Lenthen K, Cairns DR, & Cohn RJ (2010, Apr). The psychosocial impact of completing childhood cancer treatment: a systematic review of the literature. J Pediatr Psychol, 35(3), 262–274. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver MS, & Wiener L (2021, Aug 15). Symptom screening via screen: Real-time electronic tracking of pediatric patient-reported outcomes. Cancer, 127(16), 2877–2879. 10.1002/cncr.33614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener L, Baird K, Crum C, Powers K, Carpenter P, Baker KS, MacMillan ML, Nemecek E, Lai JS, Mitchell SA, & Jacobsohn DA (2014, Feb). Child and parent perspectives of the chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) symptom experience: a concept elicitation study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(2), 295–305. 10.1007/s00520-013-1957-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener L, Battles H, Zadeh S, Widemann BC, & Pao M (2017, Apr). Validity, specificity, feasibility and acceptability of a brief pediatric distress thermometer in outpatient clinics. Psycho-Oncology, 26(4), 461–468. 10.1002/pon.4038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis G (2010). Cognitive interviewing: a tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe J, Orellana L, Cook EF, Ullrich C, Kang T, Geyer JR, Feudtner C, Weeks JC, & Dussel V (2014, Apr 10). Improving the care of children with advanced cancer by using an electronic patient-reported feedback intervention: results from the PediQUEST randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32(11), 1119–1126. 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.5981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.