Abstract

Objective

Child maltreatment (CM) is a recognized public health problem, and epidemiologic data suggest that it is a widespread phenomenon, albeit with widely varying estimates. Indeed, CM as well as child abuse (CA) and neglect (CN) are complex phenomena that are difficult to study for several reasons, including terminological and definitional problems that pose a hurdle to estimating epidemiological rates. Therefore, the main aim of this umbrella review is to revise recent review data on the epidemiology of CM, CA, and CN. A second aim was to revise the definitions used.

Method

A systematic search of three databases was performed in March 2022. Recent reviews (published in the last 5 years: 2017-March 2022) addressing the epidemiological rates of CM, CA, and/or CN were included.

Results

Of the 314 documents retrieved by the selected search strategy, the eligibility assessment yielded a total of 29 eligible documents. Because of the great heterogeneity among them, a qualitative rather than a quantitative synthesis was performed.

Conclusions

The data from this umbrella review show that the different age groups, methods, and instruments used in the literature to collect the data on the epidemiology of CM make it difficult to compare the results. Although definitions appear to be quite homogeneous, CM categorization varies widely across studies. Furthermore, this umbrella review shows that the CM reviews considered do not examine some particular forms of CM such as parental overprotection. The results are discussed in detail throughout the paper.

Keywords: child, adolescents, maltreatment, abuse, neglect, epidemiology, terminology

Introduction

Child maltreatment (CM) is internationally recognized as a serious public health, human rights, legal, and social problem (World Health Organization, 2006). Epidemiological studies show that CM is extremely common. Approximately one in four children is affected at some point in their lives (Lippard & Nemeroff, 2020). In terms of mental health, the various forms of CM such as child neglect (CN) and child abuse (CA) are considered the strongest predictors of several mental disorders across the lifespan and are associated with 44.6% of disorders occurring in childhood and 25.932.0% of disorders occurring later (Green et al., 2010; Lippard & Nemeroff, 2020; McCrory et al., 2017). They are also a major cause of more severe symptomatology, poor prognosis, and treatment resistance, regardless of the disorder or type of therapy (McCrory et al., 2017; Farina et al., 2019). For these reasons, the study of CM is crucial not only for developmental psychopathology but also for all mental health fields: from clinical psychiatry to psychotherapy and health psychology.

In the scientific literature, different forms of CM are described: physical, sexual, emotional /psychological abuse, and neglect (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; World Health Organization, 2006). They can occur individually or, more commonly, in combination (Farina et al., 2019; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2022). However, despite their importance and prevalence, definitions and conceptualizations of CM, neglect, and abuse lack broad agreement among researchers. For example, some authors (e.g., Bernstein et al., 1998) acknowledged phenomena such as child abuse and neglect under the conceptualization of trauma, while some other conceptualizations (as in the case of Centers for Disease and Control Prevention, 2022) included them under the wider category of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). This leads to wide variability in epidemiologic data, which is in addition to other complex factors such as the different age groups sampled, the different instruments used, and, in general, the survey method (Stoltenborgh et al., 2011; World Health Organization, 2022). Indeed, as reported by Moody et al. (2018, p. 1) “estimating the prevalence of child maltreatment is challenging due to the absence of a clear ‘gold standard’ as to what constitutes maltreatment”.

Thus, the aim of this umbrella review (Grant & Booth, 2009) is to provide a comprehensive overview of recent review-data on the epidemiology of the various forms of CM and to consider possible moderators. A further aim is to analyze, summarize, and critically discuss the definitions and conceptualizations used in these recent epidemiologic reviews of CM and its various forms.

Methods

Search strategy

The systematic search was conducted on March 28th, 2022, in the Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science (WoS) databases by combining the following search terms: "child maltreatment" or "child abuse" or "child neglect" and "incidence" or "prevalence" or “epidemiology”. The search strategy for each database is reported in table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy

| Database |

Search characteristics

|

Search terms combination |

| Scopus |

|

|

| WoS |

|

( "child maltreatment" OR "child abuse" OR "child neglect" ) AND ( "incidence" OR "prevalence" OR "epidemiology") |

| PubMed |

|

Abbreviation: WoS (Web of Science). Note: *= the research has been conducted on March 28th.

The search was limited to the last five years (i.e., only publications from 2017 to March 2022 were considered) and to review articles. This time period was chosen to cover the most recent reviews, most of which examine different decades of research on CM, CA, and CN. In this way, we chose to conduct an umbrella review (Grant & Booth, 2009) of the recent literature. A glossary of abbreviations used in the text and tables is provided in table 2 to facilitate reading.

Table 2.

Glossary of abbreviations mentioned in the text and tables

| Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|

| ABI | Abuse Behavior Inventory |

| ACEES | Adolescent Complex Emergency Exposure Scale |

| ACE-IQ | Adverse Childhood Experience-International Questionnaire |

| ACEs | Adverse Childhood Experiences |

| AHT | Abusive Head Trauma |

| AJVQ | Applying the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire |

| ASDQ | Applying the Strenght and Difficulties Questionnaire |

| ASI | Adolescent Symptom Inventory |

| CA | Child Abuse |

| CATS | Child Abuse and Trauma Scale |

| CCNS | Chinese Child Neglect Scale |

| CEA | Child Emotional Abuse |

| CECAQ | Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse Questionnaire |

| CECAQ-SF | Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse Questionnaire-short form |

| CEM | Child Emotional Maltreatment |

| CEN | Child Emotional Neglect |

| CEVQ | Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire |

| CIDI PAPI | Composite International Diagnostic Interview – Paper and Pencil Interviewing |

| CM | Child Maltreatment |

| CN | Child Neglect |

| CPA | Child Physical Abuse |

| CPANS | Child Psychological Abuse and Neglect Scale |

| CPN | Child Physical Neglect |

| CPSA | Child Psyhcological Abuse |

| CR | Critical Review |

| CSA | Child Sexual Abuse |

| CSV | Child Sexual Violence |

| CTAS | Childhood Trauma & Abuse Scale |

| CTI | Childhood Trauma Inventory |

| CTQ | Childhood Trauma Questionnaire |

| CTQ-SF | Childhood Trauma Questionnaire- Short Form |

| CTSPC | Confict Tactics Scales Parent Child version |

| CWTQ | Child War Trauma Questionnaire |

| DV | Domestic Violence |

| EDS | Everyday Discrimination Scale |

| EM | Emotional Maltreatment |

| ETI | Early Trauma Inventory |

| EV | Emotional Violence |

| HPSAQ | Histories of Physical and Sexual Abuse Questionnaire |

| I | Incidence |

| ICAST-C | ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tool-Children Version |

| JV | Justice Involved |

| JVQ | Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire |

| JVQ-R2 | Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire Revised 2 |

| K-SADS | Kiddie-Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia |

| LEC | Life Event Checklist |

| m.o. | Months old |

| MA | Meta-analysis |

| MoWCD | Ministry of Women and Child Development |

| MYSI | Massachusetts Youth Screening Instrument |

| N | Neglect |

| NAS | Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome |

| NorAQ | NorVold Abuse Questionnaire |

| P | Prevalence |

| PBI | Parental Bonding Instrument |

| PC-CTS | Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale |

| PHAC | Public Health Agency of Canada |

| PM | Physical Maltreatment |

| PMI | Psychological Maltreatment Inventory |

| PP | Pooled prevalence |

| PRCAS | Personal Report of Childhood Abuse Scale |

| PSDS | Post-traumatic Stress Diagnosis Scale |

| PSY | Psychological Maltreatment Scale |

| PV | Physical Violence |

| R | Review |

| RBQ | Retrospective Bullying Questionnaire |

| SACS | Sexual Abuse Checklist Survey |

| SBS | Shaken Baby Syndrome |

| SCR | Scoping Review |

| SDQ | Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire |

| SES | Sexual Experiences Survey |

| SM | Sexual Maltreatment |

| SR | Systematic review |

| SSQCS | Semistructured Questionnaire for Children/ Students |

| TAA | Trauma Assessment for Adults |

| TAQ | Trauma Antecedents Questionnaire |

| TDS | Trauma and Distress Scale |

| TEC | Trauma Event Checklist |

| THQ | Trauma History Questionnaire |

| TLEQ | Traumatic Life Experience Questionnaire |

| TSA | Teen Sexual Abuse |

| UHR | Ultra High Risk |

| WDW | Witnessing Domestic Violence |

| WEC | War Experience Checklist |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| y.o. | Years old |

| YI | Youth Inventory |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Regarding inclusion criteria, we included documents if they: i) were written in English, ii) were review studies (e.g., narrative reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses), iii) primarily, overtly, and conclusively reported incidence or prevalence rates (or ODD ratio values) for CM, and/or CA, and/or CN as a result of their review process. To this regard, we included both retrospective (e.g., those focusing on adult samples in whom CM/CA/CN occurred in childhood) and developmental (i.e., those focusing on CM/CA/CN that occurred or were reported in childhood) review data. In this context, we did not define CM, CA, and CN or their age range in childhood a priori, but we chose to extract and discuss this information. On the other hand, documents were excluded if they: i) were not written in English, ii) were not review articles, iii) addressed other topics (not aimed at reviewing the epidemiology of CM/CA/CN), iv) did not primarily, overtly, and conclusively reported summary/pooled/range data for incidence or prevalence rates (or ODDs ratio) of CM, and/or CA, and/or CN in the main text as a result of the review process. In accordance with exclusion criterion “iii)”, we chose to exclude reviews on non-accidental trauma because the association with CM, CA, and CN is not direct. Similarly, we excluded all studies dealing with bone fractures where the association with such experiences was not direct. However, we did not exclude studies in which such an association is direct by definition such as, for example, those on Shaken Baby Syndrome/Abusive Head Trauma or Traumatic Head Injury due to Child Maltreatment.

Inclusion of studies was assessed by two independent raters. In disputed cases, a third rater assessed that record and decided on inclusion. In further cases of doubt, inclusion was discussed by conferencing among the three raters until consensus was reached. The inter-rater agreement between the first two raters was fair (Cohen’s kappa= .23; accordance=75.25%).

Data extraction and analysis

The data contained in the included reviews were analyzed and extracted by a trained researcher and independently reviewed by two other trained scholars. In accordance with the aims of the current study, the following data were extracted: author/s, year of publication, type of article, number of studies included in the review, temporal range of the correspondent literature research, CM/CA/CN temporal assessment (retrospectively conducted on adults reporting CM/ CA/CN in childhood or conducted at developmental age and related to ongoing or recent CM/CA/CN), target population, target country (if any), types of CM/ CA/CN considered, macro-category under which they were categorized, epidemiologic rates (these data are presented in table 3). In addition, we also extracted the following definition-related information (table 4): definition of childhood, assessment instruments, types of CM/CA/CN considered (this information overlaps with that previously cited and has been duplicated in tables 3 and 4 for ease of reading), operational definition of CM/CA/CN (according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the included review), cited definition/s for CM/CA/CN (if any), and the respective references (if any). With respect to the cited definitions, in this section we decided to include also macro-definitions under which CM/CA/CN (e.g., polyvictimization) was classified.

Table 3.

Resuming table of included studies

| Study | Type of article |

Included studies a) N, b) research temporal range |

CM, CA, CN assessment methodology/time span | Population | Country | Types of CM/CA/CN* | Epidemiological rates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahad, Parry, and Willis (2021) | SCR |

a) N=7 (those on which summary P data are based), b) 1960-2020 |

Developmental age | Child laborers | South Asian countries | CPM, CE/PM, CSM, CN, financial exploitation, forced work, over burden, witness/indirect victimization | P for CPM =15.14%, CE/PM=52.21%, CSM=16.82%, CN=12.9%, financial exploitation=2.2%, forced work=1.7%, over burden= 3%, witness/indirect victimization= 94.46%. |

| Biswas and Shroff (2021) | R |

a) overall, N=7; b) 2000-2013 |

Mixed | Not specified | Canada and worldwide | SBS/AHT | For Canada, the main text did not provide summary data. Global incidence rates of SBS/AHT not known, its incidence rates go from 14 to 53 per 100,000 live births. |

| Bodkin et al. (2019) | SR and MA |

a) overall, N=29; b) 1987-February 2017 |

Youth and adult samples (retrospective) | Canadian incarcerated population | Canada | CSA, CPA, CN, CEA | The summary P for any type of CA was 65.7% among W; only one study reported the P among M (35.5%). The summary P of CSA was 50.4% among W and 21.9% among M. The P of CN was 51.5% among W and 42.0% among M. The P of CPA was 47.7%, and the P of CEA was 51.5%. |

| Brunton and Dryer (2021) | SR |

a) N=49 overall, n=26 for P; b) 1969-2018 |

Adulthood (retrospective) | Pregnant women | Not specifically addressed (included studies come from different countries, mostly from North America, and Europe) | CSA | The P of CSA in pregnant women ranged from 2.63 to 37.25%. |

| Burrows et al. (2018) | Presentation of the WHO website reporting preva- lence estimates based also on review data |

a) included studies vary for the considered Country**; b) years range varies for the considered Country |

Lifetime prevalence estimates | CN, CPA, CPSA |

The statement on the website report that the following estimates “do not represent national or regional prevalence estimates”. Instead, they are the “median value in the range of lifetime prevalence estimates reported by studies in the database”. CN: median P - USA = 16%, Netherlands= 27%, Turkey= 34%, China= 18%. CPA: median P – Canda= 19%, USA= 19%, Sweden= 14%, Netherlands= 9%, UK and North Ireland= 9%, Turkey= 25%, China= 19%, Japan= 15%, South Africa= 33%, Australia= 11%. Sexual abuse: median P – Canada= 14%, USA= 14%, Mexico= 5%, Brazil= 6%, Norway= 8%, Sweden= 7%, Finland= 5%, Netherlands= 20%, UK and North Ireland= 11%, Switzerland= 11%, Spain= 9%, Turkey= 7%, Japan= 4%, China= 7%, India= 18%, South Africa= 24%, Australia= 12%. New Zeland= 12%. CPSA: median P – USA= 38%, UK and North Ireland= 16%, Netherlands= 18%, Turkey= 22%, China= 38%, South Africa= 32%. |

||

| Choudhry et al. (2018) | SR |

a) overall, N=51; b) 1st January 2006-1st January 2016 |

Mixed | Not specified (studies performed in Indian context) | India | CSA (experience4, perpetration, or response to CSA in India) | The P of CSA went from 4%- 41% in studies on young students W below 18 y.o. Among W above 18 y.o., the lifetime CSA P was of 3–39%. P variations has been observed depending on inclusion or all types of CSA (non-contact, contact, forced). P of CSA goes 4-66% in specific populations such as victims of trafficking girls and W. CSA P reported among boys in educational institutions went from 4% to 57%. P of experiencing one form of CSA (non-contact, contact, forced) in school or college boys goes from 10 to 55 |

| Devries et al. (2019) | SR |

a) N= 72 surveys (2 publications, 70 datasets); b) Up to December 2015 |

Developmental age | 0-19 y.o. | Latin American and Caribbean Countries (34 countries) | PV, EV by caregivers, by students, physical IPV. |

P of PV and EV by caregivers ranged from 30% – 60% and decreased with increasing age. P of physical violence by students (17% – 61%) decreased with age, while EV was constant (60% – 92%). P of physical IPV ranged from 13% – 18% for F aged 15 – 19 years. |

| Fu (2018) | SR and MA |

a) overall, N=32; among which N=9 on total CM, N=22 on CPA, N=27 on CEA, N=23 on CSA, N=20 on CPN, and N=20 on CEN.; b) 2006-2017 (results) |

Youths (retrospective) | Chinese college students | China | CPA, CSA, CE/PA, CN | The PP of CM among college students was 64.7%. For CPA, CEA, CSA, CPN and CEN, the PP estimates were 17.4%, 36.7% 15.7%, 54.9% and 60.0%, respectively |

| Hellström (2019) | SR |

a) overall, N=6; b) Up to 12 March 2019 |

Developmental age | Children with ADHD and ASD | Not specified (included studies come from different countries) | CPA, CEA, CSA, CPN and CEN | Children with ASD reported CM P rates ranging from 16.2 to 50.4%, and those with ADHD rates going from 16.9 to 30.0%. For children with ADHD, P rates for conventional crime were of 34.6–75.5%, CSA were of 6.6–38.2%, and witnessing and indirect violence were of 14.0–41.5%- For children with ASD, they were, respectively, of 8.1–64.2% for conventional crime, 2.8–27.3% for CSA; and 5.9–30.0%, for witnessing and indirect violence. |

| Karlsson and Zielinski (2020) | R |

a) it varied for CSA (N=23), lifetime sexual assault (N=14); and TSA (N=6); b) through August 2017 |

Adulthood (retrospective) | Incarcerated woman | United States | CSA, TSA | CSA rates range goes from 10% to 66%, best estimates for CSA from studies using validated survey methods= 50-66%. Lifetime sexual violence= 56–82%. Limited number of studies for TSA but its range goes from 9% to 36%, |

| Kimber et al. (2017) | CR |

a) overall N=23; b) to 26 October 2015 |

Adulthood (retrospective) | People with eating disorders or eating disordered behaviors | Not specifically addressed (half of studies does not report it, the other half comes from various countries) | CEA, CEN, exposure to IPV | CEA and CEN prevalence among individuals with BN, BED and binge eating symptoms goes from 21.1% to 66.0%. No available data about child IPV exposure P. |

| Laurin, Wallace, Draca, Aterman, and Tonmyr (2018) | SR |

a) overall, N=73 representing N=71 surveys; b) January 2000-March 2016 (data collected after 1999) |

Developmental age | Youths | Not specified | CM including CSA, CPA, CEM, CN, and IPV exposure. | Summary estimates for lifetime P ranged from .3% to 44.3% for CSA, 4.2% to 58.3% for CPA, 3.1% to 78.3% for CEM, .9% to 38.3% for CN, and .6% to 30.9% for IPV exposure. |

| Le, Holton, Romero, and Fisher (2018) | SR and MA |

a) overall, N=30; b) 2005-2015 |

Developmental age | Children and adolescents | Low- and lower middle-income countries | Various forms of victimization: PM, SM, EM, N, witnessing violent acts; experiences of being robbed; having personal property vandalized and abduction. | PP of experiences of any victimization was 76.8%. The P overall estimate of polyvictimization was of 38.1%. |

| Malvaso et al. (2021) | SR |

a) Overall, N=124; b) 1st January 2000 to 31st December 2019 |

Youths (retrospective) | JI youths | Not specifically addressed (included studies come from different countries; mostly from Western cultures) | CSA, CPA, CEA, CEN, CPN, DV, and parental offending, others. | Compared with NJI youths, for JI ones the odds of experiencing at least one ACE were greater (over 12 times). P of individual ACEs ranged from 12.2% for CSA among JI youth. The PP of JI youths who were reported to have experienced CPA of 27.4%. The PP of JI youth who were reported to have experienced CEA of 34.2%. The PP of parental offending was of 60.8%. The PP of JI youths who were reported to have experienced DV was of 55.3%. |

| Mlouki, Nouira, Hmaied, and El Mhamdi (2020) | SR |

a) overall, N=16 articles; b) Until 2 October 2019 |

Developmental age | Youths (13-24 y.o.) | Maghreb countries | Exposure to violence by youth (13-24 years), including exposure to violence: PV, EV, SA). | P of CPA=43.8%, resulted as the most common type of violence. Adolescent M were mostly affected by PV, F were more exposed to EV (63% vs 51%). |

| Mo et al. (2020) | SR |

a) overall, N= 39; studies included in quantitative synthesis for N=10 CPA, N=6 for CSA, N=5 for CN, N=4 for CEA, N=3 for WDW; b) December 2010 to March 2018 |

Not specified | Not specified (Japanese context children) | Japan | CPA, CSA, CPSA (WDV and other/CEA), CN. | CPA2 – P= 8.40% and I= 1.50% for M, and P=6.69% and I=1.19% for F. CSA - P= .33% and I= .11 % for M, and P=7.38% and I=2.54% for F. CPSA (WDV) - P= 9.94% and I= 2.16% for M, and P= 16.75% and I=3.64% for F. CPSA (Other)3 - P= 5.64% and I= 1.23% for M, and P=5.95% and I=1.29% for F. CN - P= 8.89% and I= 1.93% for M, and P=9.01% and I=1.96% for F. |

| Moody, Cannings-John, Hood, Kemp, and Robling (2018) | SR |

a) N=10; b) 1st January 1990 to 30th June 2014 |

Developmental age (included studies are defined as retrospective) | Young children (≤5 y.o. as inclusion criterium) with rib fractures | Not specified | CSA, CPA, CEA, CPN, CEN | Among infants < 12 months old, abuse prevalence ranged from 67% to 84%, whereas children 12-23 months old and 24-35 months old had study-specific abuse P of 29% and 28% respectively. |

| Pan et al. (2021) | MA |

a) N=48; b) Up to 2nd April 2018 |

Adulthood (retrospective) | Women | Worldwide (16 countries) | CSA | The pooled overall rate of CSA was of 24%. |

| Peh, Rapisarda, and Lee (2019) | SR and MA |

a) overall, N=17 studies (28 publications); |

b) to 25 September 2018 |

Mixed [both retrospective and prospective (longitudinal studies)] Mainly adolescents and young adults, UHR for psychosis versus controls | Not specifically addressed (included studies come from various countries) | CEA, CPA, CEN, CPN, CSA | Overall, the P of CEA, CPA, CEN, CPN, CSA goes from 54 to 90%. People with UHR were 5.06 times like to report CEA, and 3.19 times to report CPA. |

| Pignatelli, Wampers, Loriedo, Biondi, and Vanderlinden (2017) | SR and MA |

a) N=7; b) Up to July 2015 |

Adolescents and adulthood (retrospective) | People with eating disorders | Not specified | CPN, CEN | Among individuals with EDs, the P of CEN is 53.3%, and of 45.4% for CPN. |

| Prangnell, Imtiaz, Karamouzian, and Hayashi (2020) | SR |

a) overall N=17, all of them measured CSA, N=6 CPA, N=3 CEA; b) Not reported. |

Adulthood (retrospective) | Adult participants with injection drug use | Not specified | CSA, CEA, CPA | CSA on injection drug use, with P of CSA in the studies ranging from 1.4% to 42%; the P of CEA is reported in two studies (2.3% and 49.6%, respectively); the reported P of CPA ranged from 1.9% to 49.5%. |

| Rees et al. (2020) | SR and MA |

a) overall, N=15 studies; b) 1st January 1975 to 3rd September 2019 |

Prospective (NAS preceding CM), included samples were 0-16 y.o. | People having suffered of NAS | Not specifically addressed (included studies come from various countries) | CM | As compared to people without NAS, CM odds were 13.96 higher in those with NAS. A strong association was found between NAS and subsequent child maltreatment (aOR, 6.49; 95% CI, 4.46-9.45; I2= 52%), injuries and poisoning (aOR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.21-1.49; I2= 0%). |

| Rumble et al. (2020) | SR |

a) overall, N=15; b) 2006-2016 |

Not specified | Indonesian context children | Indonesia | CSV | CSV estimates went from 0% to 66%. |

| Tanaka, Suzuki, Aoyama, Takaoka, and MacMillan (2017) | SR |

a) N= 6+2 (8); b) Up to July 2015 |

Both adults and developmental age (e.g., high school students) | Non-clinical samples | Japan | CSA | P range for contact CSA was of 10.4%–60.7% for F, and of 4.1% for M. P range of penetrative CSA for F was of 1.3%–8.3% and of .5%–1.3% for M. |

| Wang et al. (2020) | SR and MA |

a) overall, N=19; b) Up to 2019 |

Developmental age | Chinese primary school and middle school students | China | CPA, CEA, CSA, CPN, CEN | The PP of CPA, CEA, CSA, CPN and CEN were .20%, .30%, .12%, .47% and .44%. |

| Zhang et al. (2020) | MA |

a) N=10; b) Up to 2nd April 2018 |

Retrospective | People with substance use disorder | Not specified | CEA, CPA, CSA, CEN, CPN | P estimates were as follows: CEA= 38%, CPA= 36%, CSA= 31%, CEN= 31%, and CPN=32%. |

| Zhang, Ji, Wang, Xu, and Shi (2021) | MA |

a) N=21; b) Up to April 2019 |

Developmental age | 3-6 y.o. children in China | China | CPN, CEN, educational, security, and medical N | The PP for N was of 32.1%. The P of CPN, CEN, educational, security, and medical N was of 15.2%, 15.2%, 10.4%, 13.8%, and 11.5%, respectively |

Abbreviations: the glossary of terms is reported in table 2.

Note: *= in this section, only information relevant to the aims of the current study are reported, **= only data coming from ≥ than 5 studies were reported; ***= included studies were those in which the participant – which could be > or < to < 18 - self-reported lifetime CM occurred prior to 18 y.o., studies for which this information was reported by secondary persons were excluded; 1= not specified but often referred as to CEA/CPSA, 2= for all reported data of this study authors stated that they “were discounted at 2% and conservative estimates were given for sensitivity analyses”, 3= here it should be noted an overlap between the definition of CEA and CPSA; 4= according to the aims of the current work, only these data have been reported.

Table 4.

Resuming table of CM, CA, CN definitions adopted in the included studies*

| Study | Types of CM/CA/CN* |

a) Operative definition of CM/CA/CN** b) Childhood temporal range c) CM/CA/CM assessment instruments |

Cited definition/s | Cited definition/s’ references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Maltreatment (CM) | ||||

| Ahad et al. (2021) | CM= CPM, CE/PM, CSM, CN, forced work, witness/indirect victimization, financial exploitation, over burden |

a) CM specifically of child laborers (agricultural, industrial, domestic). The focus is “on CM in response to intentional abuse of children within their immediate environmental setting, family, and workplace” (Ahad et al., 2021, p. 2). b) Under 18 y.o. c) Not an inclusion criterium. Various instruments including self-developed questionnaire, AJVQ, ASI, ASDQ, JVQs, SDQ child laborer report, SDQ care-home employes report, YI child-laborers report, YI-4R. |

CM [from National Research Council (1993)] = “an action against children that is outside the norms of conduct and results in the risk of possible physical injury and psychological disorder”. CM [from WHO (general citation) and Rutherford, Zwi, Grove, and Butchart (2007)] = “all forms of physical or psychological harm, sexual abuse, neglect or other types of exploitation that results in potential harm to children’s health, their survival or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power”. CM [from Amdi (1990)] = it “implies an injury that is non-accidental, or deliberately inflicted on the child”. |

National Research Council (1993); WHO (general citation); Rutherford et al. (2007, p. 678); Amdi (1990). |

| Burrows et al. (2018)–WHO platform | CM= CN, CPA, CPSA |

a)- b) Under 18 y.o. c) Various (main survey instruments reported on the website are the followings: ACE, JVQ, ICAST, PC-CTS) |

CM (from World Health Organization ) = “Child maltreatment is the abuse and neglect of people under 18 years of age. It includes all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other exploitation, resulting in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power. Four types of child maltreatment are generally recognized: physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological (or emotional or mental) abuse, and neglect” (World Health Organization). | World Health Organization |

| Kimber et al. (2017) | CM= CEA, CEN, exposure to IPV |

a) Not specifically defined b) Prior to 18 y.o. c) Not an inclusion criterium. Various instruments including CTQ, self-developed/single item measures, CTI, CATS, CEVQ, PBI, PMI, PSY, TAQ. |

CM [from Gilbert et al. (2009)] = it “includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, physical and emotional neglect and child exposure to intimate partner violence”. CEA= “an act of omission and commission, which is judged based on a combination of community standards and professional expertise to be psychologically damaging. It is committed by parents or significant others who are in a position of differential power that render the child vulnerable, damaging immediately or ultimately the behavioral, cognitive, affective, social and physiological functioning of the child” (Caslini et al., 2016). Authors report that CM research suggest that EA (acts of commission) and EN (acts of omission) are distinct forms of CA with physiological and psychological consequences Hibbard et al. (2012). Child exposure to IPV [from Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, and Hamby (2013)] = “includes child exposure to the intentional use of physical, sexual, or verbal violence between their adult caregivers”. |

Gilbert et al. (2009); Caslini et al. (2016); Hibbard et al. (2012); Finkelhor et al. (2013) |

| Wang et al. (2020) | CM= CPA, CEA, CSA, CPN, CEN |

a) 1 or more CM forms among CPA, CEA, CSA, CPN and CEN occurred prior to 18 y.o. b) Under 18 y.o. c) Not an inclusion criterium. Various instruments including CTQ, CTSPC, PRCAS and other self-developed single or multiple item questionnaires about sexual abuse. |

CM [according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019)] = “physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse and neglect suffered by individuals during childhood (under the age of 18)”. |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019) |

| Laurin et al. (2018) | CM= CSA, CPA, CEM, CN, and IPV exposure. |

a) Even if Authors found a variability in definitions of CM, they noted that they were conceptually similar to PHAC classifications. They applied this classification, for which CM includes EM, N, IPV exposure, PA, SA. Articles were included if the CM perpetrator was a parent/other caregiver (exceptionally for SA the perpetrator could be anyone). Articles were excluded if focused on peer/online victimization. b) Under 18 y.o. c) Not an inclusion criterium. When reported, instruments (often modified from the original) included (but are not limited to): JVQ, different versions of the CTS, and the ICAST-C. |

CM= Authors adopted the classification of PHAC, they also reported a classification table (Laurin et al., 2018; pag. 40-41). |

Public Health Agency of Canada (2010) |

| Fu (2018) | CM= CPA, CEA, CSA, CPN and CEN |

a) CM= CPA, CEA, CSA, CPN and CEN; b) Prior to 18 y.o. c) They included only articles reporting validated measurement of CM. Instruments included CTQ, CPANS, ACEs, CECA, PRCAS. |

CM= “as the abuse and neglect of children under the age of 18, includes physical abuse, emotional abuse (also referred to as psychological abuse), sexual abuse and neglect”. |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017) |

| Hellström (2019) | CM= CPA, CEA, CSA, CPN and CEN |

a) They included studies investigating ≥ 4 different victimization forms in children and adolescents; b) Up to 19 y.o. c) Not an inclusion criterium but a reported assessment method was sought for inclusion. Instruments included JVQ (mostly), and a modified scale of ACE questionnaire. |

Polyvictimization [as macro-category, according to Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, and Hamby (2005)]= “exposure to multiple forms of abuse, victimization, or violence including, but not limited to, conventional crime, child maltreatment, peer and sibling victimization, sexual assault, and witnessing and indirect victimization”. Authors also added that “polyvictimization can also be expressed as exposure to violence in different settings or environments, such as the school, home, and community”. CM [according to World Health Organization (2019)] = CM is “also referred to as child abuse or neglect” concerns “all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, negligence, and commercial or other exploitation, which results in actual or potential harm to child’s health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility trust or power. Exposure to IPV is also sometimes included as a form of CM”. |

Finkelhor et al. (2005); World Health Organization (2019) |

| Moody et al. (2018) | CM=CSA, CPA, CEA, CN |

a) CSA, CPA, CEA, CN. Authors also highlight variations in categories’ definitions in UK countries suggesting that, even if this can produce some difficulties in comparisons, according to the aims of their work them all can be classified in terms of ‘maltreatment’. They included studies in which lifetime CM was reported by people (irrespective of their age, they can be or children or adults) as occurred prior to 18 y.o. Studies were excluded if they restrict CM to “a specific time reference period (…) compared to entire 18 years of childhood” and if CM was not reported by the participant (e.g., parent-reported). b) Under 18 y.o.; c) They included only self-reported lifetime CM, self-or researcher- administered. Instruments: Not reported. |

CM [according to World Health Organization (1999)] = “All forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other exploitation, resulting in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power” (World Health Organization, 1999), along with the statement added by Authors “with the clear realisation that the four categories may coexist in the same child” (Moody et al., 2018). In the appendix, authors also reported core definitions (according to [*]) including: Physical abuse= “A form of abuse which may involve hitting, shaking, throwing, poisoning, burning or scalding, drowning, suffocating or otherwise causing physical harm to a child. Physical harm may also be caused when a parent or carer fabricates the symptoms of, or deliberately induces, illness in a child”. Emotional abuse= “The persistent emotional maltreatment of a child such as to cause severe and persistent adverse effects on the child’s emotional development”. Sexual abuse= “Involves forcing or enticing a child or young person to take part in sexual activities, not necessarily involving a high level of violence, whether or not the child is aware of what is happening”. Neglect: “The persistent failure to meet a child’s basic physical and/or psychological needs”. |

World Health Organization (1999) [*] Authors cited: “HM Gov, 2013” but it is not overtly reported in reference section, however, we found overlapping definitions at: https://www.havering.gov.uk/info/20083/safeguarding_children/383/what_is_child_abuse#:~:text=Emotional%20abuse%20is%20the%20persistent,the%20needs%20of%20another%20person, and at https://www.canschools.co.uk/937/categories-of-abuse. |

| Nelson et al. (2017) | CM=CSA, CPA, CEA, CEN, CPN |

a) CM defined as CSA, CPA, or CEA, and/or CPN or CEN; b) Up to 18 y.o c) Not an inclusion criterium. Instruments: not reported. |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Le et al. (2018) |

Victimization forms= PM, SM, and EM. N, violent acts witnessing, being robbed; abduction, having personal property vandalized. |

a) Victimization= “experiences of physical, verbal/ emotional, or sexual violence; neglect; witnessing of violent acts in the family or in the community; property vandalism; abduction; displacement; being threatened; or robbed” (Le et al., 2018, p. 325). For polyvictimization a cutoff of 4 forms of victimization was used. b) Up to 19 y.o c) Not an inclusion criterium. Various instruments including face-to-face interviews, self-administered questionnaires, both or not specified; most of studies used study specific questionnaires, other instruments included YRBS, ACES, ACEES, ACEs, EDS, DSM-IV TR, WEC, LEC, modified TEC, JVQ R2, CWTQ, K-SADS traumatic event checklist, SSQCS. |

CM = “all forms of physical and emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, and exploitation that results in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, development or dignity” (World Health Organization, 2015). Polyvictimization [according to Finkelhor et al. (2005)] = “experiences of multiple forms of victimization, not only child maltreatment but also victimization perpetrated by peers and siblings; conventional crimes including property vandalism, robbery, theft, physical assault, and abduction; witnessing of family and community violence; and cyber bullying”. |

World Health Organization (2015); Finkelhor et al. (2005) |

| Rees et al. (2020) | CM |

a) Not specified; b) Not specified; c) Not an inclusion criterium. Instruments: not reported. |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Child Abuse (CA) | ||||

| Karlsson and Zielinski (2020) | CSA, TSA |

a) Not specifically defined. b) Under 18 y.o. c) Not an inclusion criterium. Various instruments (exclusively or in combination) included single or multiple item self-developed questionnaires, modified version or selected items of the SES or SES-R, selected items or full version of the CTQ, TLEQ, adapted or selected items from the LSC-R, modified version of CSA index, “slightly revised” version of the HPSAQ, modified version of the TAA, PDS, THQ, SACS, selected items from the ABI, ACES, adapted items from the trauma exposure section of the CIDI PAPI, or not specified. |

Authors highlight the difficult in operationalizing sexual victimization since the lack of a commonly accepted definition and the presence of different operationalization. Accordingly, they suggest some definitions from other works (Black, 2011; Tjaden, 2000) which have some common points such as “the occurrence of unwanted or coerced contact of a sexual nature”. Furthermore, they suggest that several researchers are in accordance with the fact that rape’s definition should involve “all three components of rape: the sexual act, the tactic used to attempt or complete the act, and the expression of nonconsent” (Cook, 2011). |

Tjaden (2000); Black (2011); Cook (2011, p. 210) |

| Bodkin et al. (2019) | CA= CSA, CPA, CN, CEA |

a) Authors used the WHO’s definition, they categorized CA as any abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional/psychological abuse, or neglect. They excluded witnessing abuse and attending residential school. They do not limit the setting and the perpetrator of the abuse1. b) Prior to 18 y.o. c) Not an inclusion criterium. Instruments: not reported. Data were collected via interviews, administrative file reviews, and questionnaires. |

CA or CM= “constitutes all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other exploitation [of children younger than 18 years], resulting in actual or potential development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power.” | WHO (not specific reference) |

| Brunton and Dryer (2021) | CSA |

a) Not specified. Articles were excluded if CA was under broader categories (e.g., trauma). b) Not a priori defined. c) Not an inclusion criterium. Various instruments including self-developed questionnaires, NorAQ, ACEs, SES, CTQ, CSA inventory, CECAQ -SF, CSA scale, CEVQ. |

CSA= a type of trauma, which is defined as “the involvement of a child in any sexual activity, in which they lack comprehension of the act, cannot consent or are developmentally unprepared, and the act contravenes laws or societal taboos” (Krug et al., 2002a). | Krug et al. (2002a) |

| Choudhry et al. (2018) | CSA |

a) CSA (experience, perpetration, or response to CSA)2. b) Generally, ≤ 18 y.o. (also studies considering an age range crossing that cut-off were included and authors were asked for disaggregated data) c) Not an inclusion criterium. Various instruments including (but not limited to) ICAST-C, CTQ, self-developed ones, Adapted MoWCD questionnaire on child abuse. |

CSA [according to WHO definition (World Health Organization, 1999)] = “the involvement of a child in sexual activity that he or she does not fully comprehend, is unable to give informed consent to, or for which the child is not developmentally prepared and cannot give consent, or that violates the laws or social taboos of society. . .”. Authors also reported [citing Putnam (2003); Wolak, Finkelhor, Mitchell, and Ybarra (2010)] that “CSA includes an array of sexual activities like fondling, inviting a child to touch or be touched sexually, intercourse, exhibitionism, involving a child in prostitution or pornography, or online child luring by cyber-predators”. |

World Health Organization (1999); Putnam (2003); Wolak et al. (2010) |

| Prangnell et al. (2020) | CA=CSA, CPA, CEA |

a) CA was assessed separately for SA, PA, EA occurred during childhood (Pais & Bissell, 2006) b) Prior to 18 y.o. c) Not an inclusion criterium but they included only studies in which CSA, CPA, CEA were assessed separately. Instruments: not reported. Most studies made a definition-based operationalization of CA experiences, while a minor part based the operationalization on some CTQ items. |

CA [according to Norman et al. (2012)] = it “typically includes physical, sexual or emotional abuse. Physical abuse has been defined as the intentional use of physical force against a child likely to cause physical injury”. SA [according to Kairys and Johnson (2002)] = it “is defined as any sexual activity where the child is unable to provide informed consent, unable to fully comprehend or is developmentally unprepared, as well as situations that violate local laws”. Furthermore, it “can occur between any two people when there is a power imbalance, regardless of age. Finally, emotional abuse, also referred to as psychological abuse, has broadly been defined as a failure to provide developmentally appropriate and supportive environments for a child, which results in psychological harm to the child” [according to Kairys and Johnson (2002); Norman et al. (2012)]. |

Norman et al. (2012); Kairys and Johnson (2002); Pais and Bissell (2006) |

| Paine et al. (2019) | Abuse in children with rib fractures |

a) Authors included studies on ≤ 5 y.o. children (or in which data from this population could be extracted). They were excluded those “studies that a priori included only children with rib fractures from either accidental mechanisms or abusive mechanisms”. The methodology of abuse determination was not a priori defined; b) ≤ 35 m.o. (included sample); c) Not an inclusion criterium. Instruments: not reported. Assessment was made in various ways including assessment based on site's Child Protection Unit and Suspected Abuse and Neglect Team, on ICD-9th Revision E-codes, specific case-based criteria, abuse stated but without supporting details on how a determination of abuse was made or suspected abuse without supporting details. |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Biswas and Shroff (2021) | SBS/AHT |

a) SBS/AHT b) Not reported c) Operationalization for inclusion not reported. Instruments: not reported. |

AHT [according to Canadian Paediatric Society (2008)] = “a specific form of traumatic brain injury and is medically defined by the constellation of symptoms, physical signs, laboratory, imaging and pathologic findings that are a consequence of violent shaking, impact or a combination of the two”. SBS [according to Canadian Paediatric Society (2001)] = “the statement did not implicitly define SBS but described it as a collection of findings including intracranial hemorrhage, retinal hemorrhage, rib fractures and fractures involving ends of the long bones. The statement added that all the findings might not be found in any individual child with the condition”. The authors add that it also stated: “impact trauma may produce additional injuries such as bruises, lacerations or other fractures”. THI-CM [according to Ward (2020)] = “traumatic injury to the head (skull and/or brain and/or intracranial structures), which may also be accompanied by injury to the face, scalp, eye, neck or spine, as a result of the external application of force from child maltreatment”. |

Canadian Paediatric Society (2008); Canadian Paediatric Society (2001); Ward (2020) |

| Tanaka et al. (2017) | CSA |

a) Authors included article measuring CSA (prior to 18 y.o.); b) prior to 18 y.o. c) Not an inclusion criterium. Assessment methodologies mostly included anonymous self-report but also face-to-face interviews (one study). Various instruments including study specific questionnaires, ACEs, IES-R. |

CSA [according to World Health Organization (2006)] = “the involvement of a child in sexual activity that he or she does not fully comprehend, is unable to give informed consent to, or for which the child is not developmentally prepared, or else that violates the laws or social taboos of society. Children can be sexually abused by both adults and other children who are – by virtue of their age or stage of development – in a position of responsibility, trust or power over the victim” World Health Organization (2006). Authors also stated the following sentence “CSA, as well as other subtypes of child maltreatment, including physical abuse, emotional/psychological abuse, and neglect”. |

World Health Organization (2006) |

| Child Neglect (CN) | ||||

| Pignatelli et al. (2017) | CN= CPN, CEN |

a) Not reported; b) Not reported. c) Authors only included studies using retrospective self-report questionnaires. Various instruments including CTQ-SF, CTQ, TEC. |

N [according to World Health Organization (1999)] = “...the failure to provide for the development of the child in all spheres: health, education, emotional development, nutrition, shelter, and safe living conditions, in the context of resources reasonably available to the family or caretakers and causes or has a high probability of causing harm to the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development. This includes the failure to properly supervise and protect children from harm as much as is feasible” (World Health Organization, 1999). Authors also add that “efforts to better define the concept of neglect have highlighted the importance of identifying specific types of the traumatic condition, i.e., emotional, physical, educational, medical and supervisory neglect” [citing Child Welfare Information Gateway (2013); Fornari et al. (2001); Gaudin Jr, Polansky, and Kilpatrick (1992); Jenny (2011); Jenny (2007); Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, and Van Ijzendoorn (2013)]. |

World Health Organization (1999); Child Welfare Information Gateway (2013); Gaudin Jr et al. (1992); Fornari et al. (2001); Jenny (2007); Jenny (2011); Stoltenborgh et al. (2013) |

| Zhang et al. (2021) | CN= CPN, CEN, educational, security, and medical N |

a) Included studies reported N rates, degree, and its subtypes in 3–6 y.o. children. Furthermore, Authors included only studies measuring N by means of the CCNS. b) Participants were 3-6 y.o. c) Only studies using the CCNS were included. |

CN [according to World Health Organization (2016a)] = it “signifies the failure, to provide adequate medical care, education, shelter, or other essentials for a child’s healthy development, despite having the means to do so”. | World Health Organization (2016a) |

| Other definitions | ||||

| Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) | ||||

| Malvaso et al. (2021) | ACEs= CSA, CPA, CEA, CEN, CPN, DV, parental offending, others. |

a) Measure of ACEs according to Felitti et al. (1998); b) prior to 18 y.o. c) They included studies using an ACEs measure “congruent in scope and/or content with the ACE scale developed by Felitti et al. (1998)” (Malvaso et al., 2021; pag. 3). Various instruments including CTQ, MAYSI, ACEs, others. |

ACEs [according to Felitti et al. (1998)] = “the cumulative effects of both maltreatment (physical, sexual and emotional abuse, and physical and emotional neglect) and household dysfunction (parental separation, domestic violence, mental illness, substance abuse, and incarceration) before the age of 18”. | Felitti et al. (1998) |

| Definitions including Childhood Trauma (CT) | ||||

| Zhang et al. (2020) | CM/CT= CEA, CPA, CSA, CEN, CPN |

a) CM/CT= CEA, CPA, CSA, CEN, CPN. Included studies reported CM on the basis of CTQ-SF with cutoff scores going from “moderate to extreme” levels of exposure (i.e., CEA . 13; CPA . 10; CSA . 8; CEN . 15; CPN . 10); b) Not reported; c) Only studies using the CTQ-SF and in which cutoff scores for each subscale were from “moderate to extreme” levels of exposure (or as follows: emotional abuse . 13; physical abuse . 10; sexual abuse . 8; emotional neglect .15; physical neglect . 10) were included. |

CM [citing World Health Organization (2016b)] = it “involves repeated trauma, physical, emotional or sexual abuse, or neglect experiences in childhood or adolescence, primarily within the family or social context” (Zhang et al., 2020, p. 2). | World Health Organization (2016b) |

| Peh et al. (2019) | Childhood adversities=CT (CEA, CPA, CEN, CPN, CSA), bullying victimization, parental separation/loss. |

a) Childhood adversities including CT, bullying victimization, parental separation/loss; b) prior to 18 y.o.; c) Not an inclusion criterium. Various instruments including CTQ, CTAS, single questions, TADS, ETI, CECA-Q, RBQ, not specified. |

“Childhood adversities typically include childhood trauma (emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect and physical neglect), peer bullying and parental separation or loss”. | Not reported |

| Pan et al. (2021) | CT=CSA |

a) CSA measured by the CTQ-SF, “where the severity of CSA exposure greater than moderate was considered positive (score .8)”; b) Not reported; c) Only studies using CTQ-SF. |

CSA [according to World Health Organization (2016b)] = it “is one of the most common types of CT”. | World Health Organization (2016b) |

| Violence | ||||

| Rumble et al. (2020) | CSV |

a) Any definition of sexual violence was accepted. Studies were excluded if merge estimates for sexual and nonsexual violence. Authors specify that they used the term “childhood violence” in order “to acknowledge the violence perpetrated by children against other children” (Rumble et al., 2020, p. 285). b) under 18 y.o.; c) They excluded studies that did not report a description of the instruments. Instruments: not reported. Various methodologies (e.g., face-to-face interviews, focus group discussions, self-administered questionnaires) |

CSV [according to Krug et al. (2002b); World Health Organization (1999, 2014)] = “the involvement of a child in sexual activity that they are unable to give informed consent to, or for which the child is not developmentally prepared, or else that violates the laws of society”. |

Krug et al. (2002b); World Health Organization (1999); World Health Organization (2014) |

| Mlouki et al. (2020) | Violence exposure (PV, EV, and SA) |

a) Violence: PV, EV, SA; b) youth going from 13 to 24 y.o.; c) Not an inclusion criterium. Various instruments and methodologies including (but not limited to) structured interview, self-administered questionnaire, clinical, medical or autopsy records, validated arabic version of the ACE-IQ. |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Devries et al. (2019) | PV, EV by caregivers, by students, physical IPV, SV |

a) Included studies were surveys reporting the P of PV, SV, EV against 0 – 19 y.o. people. Authors accepted all definitions of violence and of perpetrators, as well as both self- and caregivers (proxy)-reports. Furthermore, Authors reported that “Data from surveys reporting age bands up to 14 years or recall periods up to 14 years were eligible, but only reports over a narrow age range (5 years or less) were included given the goal of summarizing the prevalence of recent violence”. b) Up to 19 y.o.***; c) Not an inclusion criterium. Instruments: not reported. Relevant international datasets from surveys, known to the authors, were included. |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Others | ||||

| Mo et al. (2020) | CPA, CSA, CPSA (WDV and other/ CEA), CN. |

a) Not specified; b) Not reported; c) Not an inclusion criterium. Instruments: not reported. |

Not reported | Not reported |

Abbreviations: the glossary of terms is reported in table 2.

Note: *= in this table, only information relevant to the aims of the current study are reported; **=as reported by inclusion criteria of the included articles; ***= Authors stated that “although the CRC defines children as 0 . 17 years of age, data on 18- and 19-year-olds were included given the ambiguities in age ranges in some datasets (e.g., labeled “≤18 years” or “≤19 years”)” (Devries et al., 2019, p. 2);1= Authors also stated that even if its exclusion, the “abuse in residential schools may have been captured in our prevalence estimates because we did not specify any limits regarding the setting of abuse or the perpetrator of abuse” (Bodkin et al., 2019, p. e8);2= Authors (Choudhry et al., 2018) considered also perpetration and response, for the aim of the current work we considered only the experience of CSA.

A qualitative synthesis was performed to interpret the results. Due to the heterogeneity of the designs and analysis methods of the reviews included in the current work, no quantitative synthesis was performed.

Results

General results

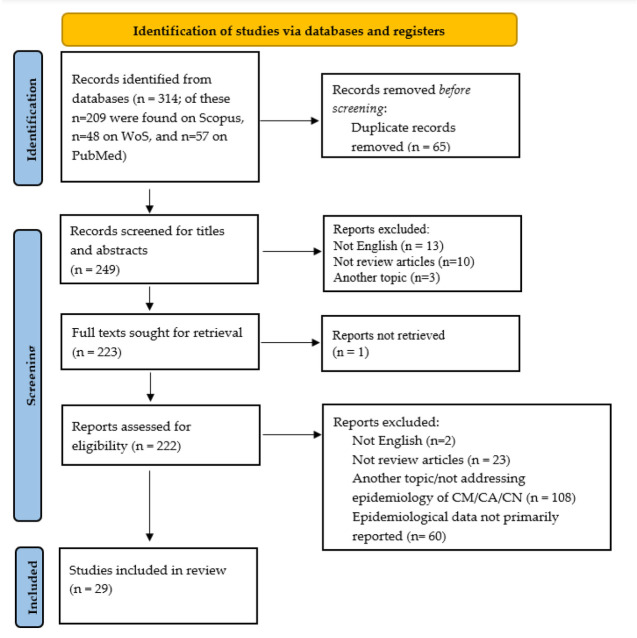

In total, the systematic search yielded 314 studies (n= 209 on Scopus, n= 57 on PubMed, and n= 48 on WoS). Of these, n= 65 records were excluded because they were duplicates. Thus, n= 249 studies were screened for eligibility. Title and abstract screening excluded a total of n=26 documents. Of these, n=13 were excluded because they were not in English, n=10 because they were not review articles, n=3 because they concerned other topics. Thus, n=223 full texts were sought for retrieval and n=1 document was not found. Thus, n=222 documents were assessed for eligibility. Of these, n=2 were excluded because they were not in English, n=23 because they were not review articles, n=108 because they addressed a different topic, and n=60 because epidemiologic data for CM/CA/CN were not primarily reported or were not specifically, overtly, and conclusively reported in terms of range values/ pooled data/ODDs ratio. Thus, 29 documents were considered eligible for the current umbrella review. The PRISMA (Page et al., 2021) flow diagram of included reviews is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of eligibility process

Of the included reviews, n=11 related to retrospective data (generally on adults), n=9 related to developmental age (of which n=1 review focused on developmental age, but the authors described the included studies as retrospective), n=1 review was prospective (i.e., considers Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) as a risk factor preceding CM), n=1 review considered both retrospective and prospective data (i.e., longitudinal studies), n=1 review considered both developmental-age individuals (i.e., high school students) and adults, n=2 did not specify, and the remaining n=3 considered mixed research designs. Furthermore, n=1 study addresses the presentation of the WHO Violence Prevention Information System, an interactive knowledge platform that contains scientific data on violence and specifically on CM, CA, and CN. The data available on this platform are based on different data sources and, according to our inclusion/ exclusion criteria, we report only the data based on a review-like methodology (i.e., merged data coming from different studies, specifically, from a number ≥ 5 studies). Regarding the target country, the above-mentioned search provides country-specific review data for all countries in the world for which such data are available (see table 3 for more details). In addition, of the included studies, n=3 were worldwide meta-analyses, n=12 were reviews conducted at country level or targeted a specific geographic area [i.e., Latin American and Caribbean countries, Maghreb, Japan (n=2), China (n=3), Canada, India, Indonesia, South Asian countries], n=1 focused on low- and lower middle-income countries, and the remaining n=12 systematic reviews or meta-analyses were conducted without considering a geographic/political criterion.

Regarding the type of CM/CA/CN reviewed, results revealed that n=6 studies focused only on Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) [also called Child Sexual Violence (CSV)], n=12 addressed both Child Physical Abuse (CPA), Child Emotional Abuse (CEA)/Child Psychological Abuse (CPA), CN [Child Neglect; expressed in terms of Child Emotional Neglect (CEN) and Child Physical Neglect (CPN), or CN only], and CSA. Other review studies were conducted on mixed forms of victimization, specifically, n=1 on Child Physical Maltreatment (CPM), Child Emotional Maltreatment (CEM)/Child Psychological Maltreatment (CPM), Child Sexual Maltreatment (CSM), CN, and financial exploitation, forced work, over burden, witness/ indirect victimization; n=1 on CEA, CEN and exposure to Intimate Partner Violence (IPV); n=1 on CSA, CPA, CEA, CEN, CPN and domestic violence, parental offending and other forms of victimization; n=1 on CSA, CPA, CEM, CN and exposure to IPV; n=1 on CPM, CPS, CEM, CN and witnessing violent acts, experiencing being robbed, having personal properties vandalized, and abduction; n=1 on exposure to violence by youths which included Physical Violence (PV), Emotional Violence (EV), and Sexual Abuse (SA); n=1 on PV, EV by caregivers, by students, and on physical IPV. In addition, n=1 addressed CM in general, n=1 addressed the Shaken Baby Syndrome/Abusive Head Trauma, and n=2 focused on CN only (one on CPN and CEN, and the other on CPN, CEN, educational, security and medical neglect). Heterogeneity in terminology and definitions used is described in more detail in a dedicated section.

A detailed description of the above reported information for the included reviews as well as for the other extracted – but here not mentioned – can be found in table 3.

Qualitative synthesis of CM/CA/CN definitions

Cited definitions

This section provides an overview of CM, CA, and the definitions used in the reviews considered. The results show heterogeneity in the definitions cited. Detailed information is provided below, and full data on these are presented in table 4.

Of the reviews considered, a large proportion cites the World Health Organization (WHO) definition. In this definition, CM is a macro-category that includes both CA and CN. Some of these studies added other citations to the WHO definition, such as in the review by Ahad et al. (2021), who also cited Amdi (1990); National Research Council (1993); and Rutherford et al. (2007). However, in studies citing the WHO for the CM definition, some differences can be found in the WHO citation, such as the document (e.g., Krug et al., 2002a; World Health Organization, 1999) or the online resource cited [e.g., the definition reported on the WHO online website visited at different time points (e.g., World Health Organization, 2015; World Health Organization, 2016a, 2019)], but also the way in which the definitions are reported. In this context, Zhang et al. (2020), for example, do not quote the World Health Organization (2016a) verbatim, and report that CM “involves repeated trauma (…)” (Zhang et al., 2020; p. 1). This aspect differs from the ongoing WHO definition which can be found on the World Health Organization (2022) website [or that reported in World Health Organization (1999)]. However, the other studies chose different citations or approaches: some of them cited definitions reported in previous studies and others cited those reported by a specific institutional consortium (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2010). For example, Wang et al. (2020) and Fu (2018) reported citations of CM from CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017; 2019, respectively), that were quite similar to those reported by WHO (see table 2 for more details). In addition, one study overlapped the concepts of CA and CM and offered a cumulative definition for them, generally citing WHO. Furthermore, Tanaka et al. (2017), whose work focused on CSA, reported it as a subtype of CM (i.e., “CSA, as well as other subtypes of child maltreatment”; p. 32).

On the other hand, some authors have classified the experiences of CA and CN (and often their subtypes CEA, CPA, CSA, CEN/CPSN, CPN) into macro-categories other than CM, such as “childhood adversities” and “childhood trauma”. For example, in the study by Peh et al. (2019), CA and CN are defined under the macro-category CT (and not CM), which in turn is defined under the macro-category “childhood adversities”. Furthermore, in the review by Kimber et al. (2017), the authors report that research on CM suggests that CEA and CEN are two different forms of CA, as the former is an act of commission and the latter is an act of omission. Apart from the classification of the act based on the agency, it can be stated in this definition that CEA and CEN fall under the category CA, which in turn is considered under the broader category CM. In doing so, the authors refer to the definition of Caslini et al. (2016), while for the definition of CM they refer to that of Gilbert et al. (2009) which, unlike other defintions such as the ones citing the WHO, includes children’s exposure to IPV as a form of CM. In addition, in the Malvaso et al. (2021) study, the authors referred to the term ACEs by Felitti et al. (1998) to indicate “the cumulative effects of both maltreatment (physical, sexual and emotional abuse, and physical and emotional neglect) and household dysfunction (parental separation, domestic violence, mental illness, substance abuse, and incarceration) before the age of 18” (as reported in Malvaso et al., 2021; p. 1). According to this definition, ACEs represent a macro-category that includes the cumulative effects of household dysfunction and CM which, in turn, include both CA and CN. In contrast, some other definitions adopted by authors group CM under the broad categories of “victimization” and “polyvictimization” (i.e., Hellström, 2019; Le et al., 2018).

Other studies focused on sexual victimization/ abuse/violence against children. Again, the included reviews show definitional inconsistencies. Indeed, as openly reported by Karlsson and Zielinski (2020; p. 327): “Operationalizing sexual victimization, on the other hand, is more challenging as there is no universal definition of sexual violence or sexual assault”. Indeed, the majority of studies define the term as CSA, but the terms CSV and Teen Sexual Abuse have also been adopted by some other authors.

In addition, n=2 studies (Pignatelli et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021) addressed CN only and provided different definitions, although both included the WHO’s citation. Furthermore, n=1 study (Biswas & Shroff, 2021) addressed a specific form of abuse, namely Shaken Baby Syndrome/Abusive Head Trauma. Again did not report a specific definition, some other included reviews. More detailed information for each included review is provided in table 4.

Operationalizations

Regarding the operationalization of CM, CA, and CN, the included studies also showed variability in this regard. Specifically, a large proportion of the reviews defined childhood as before age 18 (i.e., 0-18 years old), whereas some other studies operationalized developmental age as 0-19 years old, and still others defined youths as between 13 and 24 years old. In addition, some operationalizations considered only CSA, while others considered both CSA, CEA, and CEN and CPSN. Others defined these categories in the context of maltreatment rather than abuse, such as the study by Ahad et al. (2021), which included Child Physical Maltreatment (CPM) – rather than CSA –, Child Emotional/Psychological Maltreatment (CE/PSM) – rather than CEA/CPSA -, Child Sexual Maltreatment (CSM) – rather than CSA. Another example is the study by Devries et al. (2019), which considered PV and EV (perpetrated by different actors) instead of CPA and CEA or CPM or CEM. Again, some studies categorize CSA, CPA, CEA, CN under the definition of ACEs (Malvaso et al., 2021), while other studies categorize them as CM (Laurin et al., 2018). Full data on operationalizations as well as on assessment materials are presented in table 4.

Qualitative synthesis of epidemiological data

Worldwide data

In a world-wide meta-analysis on the prevalence of CSA in women (Pan et al., 2021), the authors used the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) as an outcome measure. The results showed that the overall pooled rate of CSA was 24%. They also reported that the rate of CSA was higher in females compared with the general group in people with mental illness. In this regard, it should be noted that this result varied by geographic region. Indeed, in the study by Moody et al. (2018), which aimed to estimate worldwide prevalence rates considering self-report studies on maltreatment, the results showed that the median prevalence of CSA among girls was 20.4% in North America and 28.8% in Australia. For boys, results showed that they generally had lower rates. Regarding CPA, rates were similar between the sexes, except in Europe, where they were 12% for girls and 27% for boys. In other countries (e.g., in Africa), CPA rates appear to be very high (e.g., 50.8% and 60.2% for African girls and boys, respectively). Regarding median rates of emotional abuse, they appear to be almost twice as high for girls as for boys in both North America (28.4% and 13.8%, respectively) and Europe (12.9% and 6.2%, respectively). However, in other countries, they appear to be more similar in girls and boys. Although few studies were available for CN, median rates were high in Africa and South America (girls: 41.8%, boys: 39.1% for the first continent; girls: 54.8%, boys: 56.7% for the second continent). On the other hand, when considering North America and Asia (i.e., the continents with the highest number of available studies) CN median rates differ between girls and boys for the first continent (40.5% and 16.6%, respectively), whereas they are similar for Asia (girls: 26.3%, boys: 23.8%). The review by Biswas and Shroff (2021) also looked at worldwide data but, unlike the other studies, focused on a specific form of abuse: the Shaken Baby Syndrome/Abusive Head Trauma. The results showed that global rates for this form of abuse are unknown. Incidence rates from the available population studies (i.e., Switzerland, New Zealand, Wales, Scotland, Queensland – Australia, USA, Canada) ranged from 14 to 53 per 100,000 live births. Epidemiologic data from the included studies are shown in table 3.

National/specific context data

Among the review studies that focused on a national – or, generally, on a specific – context, Choudhry et al. (2018) conducted a systematic review that focused on CSA in the Indian context and considered literature published from 2006 to 2016. The results showed that CSA prevalence went from 4% to 41% among girls under 18 years of age, and among those who exceeded this age window lifetime CSA-P went from 3% to 39%. Among boys in educational institutions, CSA-P went from 4% to 75%. Furthermore, Fu (2018) conducted a systematic-review and meta-analytic study in the Chinese context, considering studies published in a time window that overlapped with the above study (from 2006 to 2017). Specifically, the authors aimed to estimate CM prevalence among college students. The results showed that the CM pooled prevalence among college students was 64.7%. Specifically, the pooled estimates for CPA, CEA, CSA, CPN, and CEN were 17.4%, 36.7%, 15.7%, 54.9%, and 60%, respectively. Even in the Chinese context, in another review (i.e., specifically a systematic review and meta-analytic study) (Wang et al., 2020), the authors considered studies up to 2019 that addressed CPA, CEA, CSA, CPN, and CEN in Chinese primary school and middle school students. They found that the pooled prevalence was 0.20% for CPA, 0.30% for CEA, 0.12% for CSA, 0.47% for CPN, and 0.44% for CEN. Of note, CEN was reported primarily in rural areas. In addition, CPN and CEN were higher in studies conducted in the northern part of the Country than in southern and central China. The results also showed that children with mental health symptoms (compared with children without them) had a higher incidence for all CM categories. In another study conducted in the Chinese context (Zhang et al., 2021), the authors meta-analyzed studies up to 2019 (April) on CN in 3-6-year-old children in China. The results showed that the PP for CN was 32.1%, while for CN subtypes it was as follows: CPN=15.2%, CEN=15.2%, educational CN=10.4%, security CN=13.8%, and medical CN=11.5%.

In the Japanese context, two review studies have been conducted (Mo et al., 2020; Tanaka et al., 2017). In the systematic review by Mo et al. (2020), the results based on studies from 2010 to 2018 yielded the following estimates for the following types of CA and CN. In males, CPA-prevalence was 8.40% and CPA incidence was 1.50%. In females, they were 6.69% and 1.19%, respectively. In males, CSA prevalence was 0.33% and the incidence was 0.11 %; in females, the prevalence was 7.38% and the incidence was 2.54%. The prevalence of Child Psychological Abuse (CPSA) associated with witnessing domestic violence (WDV) was 9.94% and the incidence was 2.16% for males. For females, the prevalence and incidence were 16.75% and 3.64%, respectively. For other forms of CPSA, the prevalence was 5.64% and the incidence was 1.23% for males. In females, the prevalence was 5.95% and the incidence was 1.29%. For CN, the prevalence and the incidence in males were 8.89% and 1.93%, respectively. In females, they were 9.01% and 1.96%, respectively. In the other systematic review conducted in the Japanese context (Tanaka et al., 2017), the authors focused on CSA studies conducted in non-clinical samples that included both individuals younger than 18 years and adults. The results showed that the prevalence of physical contact (not involving penetration)-CSA ranged from 10.4% to 60.7% in females and was 4.1% in males. On the other hand, the prevalence of penetrative-CSA went from 1.3% to 8.3% in females, and from 0.5% to 1.3% in males. Regarding South Asian countries in general, the scoping review by Ahad et al. (2021) examined studies from 1960 to 2020 that estimated the epidemiology of child laborers’ CPM, CE/PM, CSM, CN, financial exploitation, forced work, over burden, witness/indirect victimization. The results showed the following prevalence values: CPM=15.14%, CE/PM=52.21%, CSM=16.82%, CN=12.9%, financial exploitation=2.2%, forced work=1.7%, over burden= 3%, witness/indirect victimization= 94.46%.

Another review (Mlouki et al., 2020) focused on studies that addressed exposure to violence among youths - including exposure to PV, EV, and SA - in Maghreb countries. They considered studies on youths conducted up to 2019 (October). The results showed that CPA-P was the most common type of violence, accounting for 43.8%. In addition, male adolescents were found to be most frequently affected by PV, while females were more likely to experience EV (63% vs. 51%). Another systematic review (Devries et al., 2019) focused on estimating the prevalence of recent PV, SV, and EV among 0-19-year-olds in Latin America and the Caribbean countries using studies and surveys up to 2015. The results showed that the prevalence of PV-and EV among caregivers ranged from 30% to 60% and decreased with age. In addition, PV prevalence among students ranged from 17% to 61% and decreased with age, which was different from EV prevalence, which was found to be constant. The prevalence of EV ranged from 60% to 92%, while the prevalence of physical IPV ranged from 13% to 18% among 15-19-year-old females. Data from Canada came from a systematic review and meta-analysis of CSA, CPA, CEA, and CN among Canadian incarcerated population (Bodkin et al., 2019). Results showed that the summary prevalence for each type of CA was 65.7% in women; only one of the studies reviewed by the authors reported prevalence in men (35.5%). The summary prevalence of CSA was 50.4% in women and 21.9% in men. The prevalence of CN was 51.5% in women and 42.0% in men. The prevalence of CPA was 47.7%, and the prevalence of CEA was 51.5%.

Of the included reviews, the one by Karlsson and Zielinski (2020) was conducted in the United States. Specifically, the authors retrospectively examined CSA and Teen Sexual Abuse (TSA) in studies conducted on incarcerated women up to 2017 (August). The results showed that the best estimates for CSA from studies that used validated survey methods ranged from 50% to 66% and that lifetime sexual violence ranged from 56% to 82%. For TSA, the authors found a limited number of studies that did not allow summation of estimates.

In addition, the systematic review and meta-analysis by Le et al. (2018) focused on data on victimization among children and adolescents from low- and lower-middle-income countries. They examined diferent forms of victimization, including CPS, CEM, CN, witnessing violent acts, experiencing being robbed, having personal property vandalized, and abduction. Results showed that the pooled prevalence of experiencing any type of victimization was 76.8%, while the overall prevalence estimate for polyvictimization was 38.1%. Another study that considers country-level data is the WHO’s Violence Info platform presentation by Burrows et al. (2018). For it, we only consider data based on a review-like methodology (i.e., merged data from a number ≥ 5 studies). Several country-level data were available (see table 3) but, as stated on their website (https://apps.who.int/violence-info/child-maltreatment), “these do not represent national or regional prevalence estimates” but “the median value in the range of lifetime prevalence estimates reported by studies in the database”.

Other data – not a priori considering a specific geographic/political context

Among reviews that did not address a specific geographic/political context (i.e., did not overtly aim to estimate epidemic rates worldwide or at a national/ specific level), a recent review by Brunton and Dryer (2021) focused on the prevalence of CSA and its associated outcomes during pregnancy and childbirth. The results showed that the prevalence of CSA in pregnant women ranged from 2.63% to 37.25%. Notably, the authors found that prevalence rates were often higher or lower depending on certain aspects (e.g., low income for higher rates and higher education for lower). In addition, pregnant women with a history of CSA (compared with women without such a history) are often more concerned about their care and childbirth, have more health-related complaints, dificulty giving birth, and are more likely to have psychiatric symptoms, poor health and sleep, and appearance related concerns. They may also use harmful substances and have a higher risk of being re-victimized.

A meta-analysis by Zhang et al. (2020) aimed at estimating the prevalence of Childhood Trauma (measured by the CTQ short form) among people with substance use disorders. CT subtypes prevalence among all samples of people with substance use disorder considered was 38% for CEA; 36% for CPA; 31% for CSA; 31% for CEN and 32% for CPN. Of note, the highest prevalence rates for emotional abuse were found in North America and South America (45%). Furthermore, prevalence rates were highest in North America (compared to other continents) for CPA and CSA, CEN, and CPN (39%-44%). In the systematic review by Paine et al. (2019), the authors examined the prevalence of abuse in children with rib fractures. Results showed that CA prevalence rates varied by age group considered. Indeed, the CA prevalence i) ranged from 67% to 82% in infants younger than 12 months, ii) was of 29% in infants aged 12 to 23 months, and iii) was of 28% in infants aged 24 to 35 months. Accordingly, the authors reported that age younger than 12 months was highly associated with an increased likelihood of abuse across studies (i.e., “the only characteristic significantly associated”, Paine et al., p. 1). In contrast, location of rib fracture was not associated.