Abstract

Background:

It is unclear whether the benefits of administration of antenatal corticosteroids in late preterm gestation outweigh its harms. We sought to understand whether patients and physicians need increased support to decide whether to administer antenatal corticosteroids in late preterm gestation, and their informational needs and preferences for decision-making roles related to this intervention; we also wanted to know if creation of a decision-support tool would be useful.

Methods:

We conducted individual, semistructured interviews with pregnant people, obstetricians and pediatricians in Vancouver, Canada, in 2019. Using a qualitative framework analysis method, we coded, charted and interpreted interview transcripts into categories that formed an analytical framework.

Results:

We included 20 pregnant participants, 10 obstetricians and 10 pediatricians. We organized codes into the following categories: informational needs to decide whether to administer antenatal corticosteroids; preferences for decision-making roles regarding this treatment; the need for support to make this treatment decision; and the preferred format and content of a decision-support tool. Pregnant participants wanted to be involved in decision-making about antenatal corticosteroids in late preterm gestation. They wanted information on the medication, respiratory distress, hypoglycemia, parent–neonate bonding and long-term neurodevelopment. There was variation in physician counselling practices, and in how patients and physicians perceived the balance of treatment harms and benefits. Responses suggested a decision-support tool may be useful. Participants desired clear descriptions of risk magnitude and uncertainty.

Interpretation:

Pregnant people and physicians would likely benefit from increased support to consider the harms and benefits of antenatal corticosteroids in late preterm gestation. Creation of a decision-support tool may be useful.

Administration of antenatal corticosteroids at 34 + 0 to 36 + 6 weeks’ (i.e., late preterm) gestation for pregnancies at risk of imminent delivery decreases the risk of neonatal respiratory distress, but also increases the risk of neonatal hypoglycemia1 and, potentially, impaired neurodevelopment,2,3 although evidence on these long-term effects is conflicting.2,4,5 Thus, although around 1 in 12 births occur at late preterm gestation,6 it remains unclear whether the benefits of antenatal corticosteroids outweigh their harms,7 and current clinical practice guidelines are inconsistent. For example, an American guideline advises routine administration of antenatal corticosteroids until 36 + 6 weeks’ gestation,8 while a Canadian guideline recommends routine administration until 34 + 6 weeks’ gestation and makes the conditional recommendation that they “may be administered between 35 + 0 and 36 + 6 weeks’ gestation […] after risks and benefits are discussed with the woman and the pediatric care provider(s).”9

We aimed to understand whether physicians and pregnant people need increased support to decide whether to administer antenatal corticosteroids in late preterm gestation. We also wanted to understand their informational needs, preferences for decision-making roles and whether creation of a decision-support tool for this treatment decision would be useful.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a qualitative framework analysis using semistructured, 1-on-1 interviews with pregnant people, obstetricians and pediatricians, conducted from April to July 2019 in British Columbia, Canada. This study was based out of BC Women’s Hospital, a tertiary hospital in Vancouver with more than 7000 births per year, where pregnant patients at high risk of late preterm birth are typically assessed by an obstetrician.

We included pregnant people at any gestation, regardless of pregnancy risk profile, given the unfeasibility of interviewing patients in the context of imminent, late preterm birth. We included both obstetricians and pediatricians, as both may be involved in counselling patients at risk of preterm birth; although obstetricians administer antenatal corticosteroids, pediatricians provide care with respect to the neonatal outcomes targeted by this intervention.

We sought to include 20 pregnant participants, 10 obstetricians and 10 pediatricians. This sample size is similar to other studies of physician and patient preferences.10,11 We intended to recruit until saturation, extending recruitment beyond the planned sample size if necessary.

Study procedures

We recruited participants by convenience sampling via posters (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/11/3/E466/suppl/DC1), social media, announcements at prenatal classes (for pregnant people) and announcements at clinical meetings (for physicians). Those interested in participating contacted the study team by email. No previous relationship existed between the research team and pregnant participants; physician participants and research team members worked in the same centre. We offered a $5 gift card to a café to participants after the interview as a token of appreciation.

We developed interview guides for each participant group (Appendix 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/11/3/E466/suppl/DC1) using our expertise as our team includes obstetricians (J.B., E.K., J.L.), a neonatologist (S.S.), decision scientists and qualitative methodologists (N.B., R.M.) and perinatal epidemiologists (J.A.H., A.B.). We asked what information was important for counselling about antenatal corticosteroids in late preterm gestation and whether patients wanted to be involved in this decision. To understand the need for support in making this decision, we asked participants for their perspectives on the balance of harms and benefits of the treatment, and we asked obstetricians about their current counselling practices. We also asked if a decision-support tool would be useful and, if so, how information should be presented. We asked pregnant participants to imagine a scenario in which they were at risk for late preterm birth. We reviewed the first 2 transcripts of interviews with pregnant participants to ensure the interview guide elicited the topics we sought. Initially, we discussed all benefits and harms of antenatal corticosteroids in 1 question. However, the review suggested this may have been difficult to follow for participants, so we subsequently separated this question into 2 (questions 2 and 4 in Appendix 2). We retained the first 2 interviews in the data set.

Two female study members (J.L., H.F.) conducted interviews in-person at the hospital campus or another site (e.g., workplace, coffee shop), as preferred by the participant. J.L. is an obstetrician with subspecialty training in maternal–fetal medicine and graduate-level training in health research methods, including courses in medical decision-making; at the time of interviews, H.F. was a medical student. After observing J.L. conduct 2 interviews, H.F. conducted 2, and J.L. reviewed their audio recordings for quality. J.L. and H.F. then divided conducting the remaining interviews. N.B. and R.M. provided mentorship and supervision for data collection, given their expertise and experience leading qualitative interview studies on decision-making in pregnancy.12

At the start of each interview, the interviewer provided introductions and reasons for the research. Participants completed a consent form and written questionnaire of demographic information. Only the interviewer and participant were present; in public places, semiprivate areas allowed private conversation. There were no repeat interviews. Each interview’s audio recording was transcribed verbatim by a transcription service. We reviewed transcripts for accuracy. Interviewers also kept written field notes for each interview.

Data analysis

We analyzed interview transcripts and written field notes using a framework analysis.13 Three research team members (J.L., H.F., R.M.) familiarized themselves with the transcripts and field notes, and developed a codebook. Initial coding took place in a group setting — comparing how each member would independently code the same data — so that any inconsistencies, misunderstandings or gaps in the codebook could be addressed immediately. We grouped codes into categories that formed an analytical framework. The team then divided the remaining transcripts and applied codes from the analytic framework to them independently (i.e., indexing). Questions were resolved by consensus. We summarized data from each transcript by category (i.e., charted into the framework). We used NVivo 12 for coding and indexing, and Microsoft Word for charting. We did not ask participants for feedback on findings. We analyzed participant data from patients and physicians separately.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia Children’s and Women’s Research Ethics Board (H18–03721).

Results

We interviewed 20 pregnant participants, 10 obstetricians and 10 pediatricians (n = 40). Most pregnant participants were nulliparous and all had postsecondary education. The physicians had a wide range of years of clinical experience (Table 1). No participants withdrew after giving informed consent. Interviews lasted 30–60 minutes. In conducting the last few interviews, interviewers noted that no new concepts emerged.

Table 1:

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | No. (%) of participants* |

|---|---|

| No. of pregnant participants | 20 |

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 34.05 ± 3.33 |

| Gestational age at the time of the interview, wk | |

| < 12 | 0 (0) |

| 12–27 | 5 (25) |

| > 28 | 15 (75) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 20 (100) |

| Parity | |

| 0 | 15 (75) |

| 1 | 5 (25) |

| Had previous baby admitted to NICU | |

| No or not applicable if parity 0 | 20 (100) |

| Yes | 0 (0) |

| Had previous preterm baby | |

| No or not applicable if parity 0 | 17 (85) |

| Yes | 1 (5) |

| Unsure | 2 (10) |

| Ever received antenatal corticosteroid treatment before (in current or previous pregnancy) | |

| No or not applicable if parity 0 | 18 (90) |

| Yes | 0 (0) |

| Unsure | 2 (10) |

| Also identifies as an obstetrical care provider (e.g., physician, midwife or nurse) | |

| Yes | 2 (10) |

| No | 18 (90) |

| No. of physician participants | 20 |

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 42.63 ± 9.08 |

| Discipline | |

| Obstetrician | 10 (50) |

| Pediatrician | 10 (50) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 6 (30) |

| Female | 14 (70) |

| Years in practice | |

| Currently in fellowship training | 1 (5) |

| < 5-year postcompletion of training | 8 (40) |

| 5–10 years postcompletion of training | 2 (10) |

| > 10 years postcompletion of training | 9 (45) |

Note: NICU = neonatal intensive care unit.

Unless indicated otherwise. Denominators are the total number of participants by type (i.e., pregnant participants or physician participants).

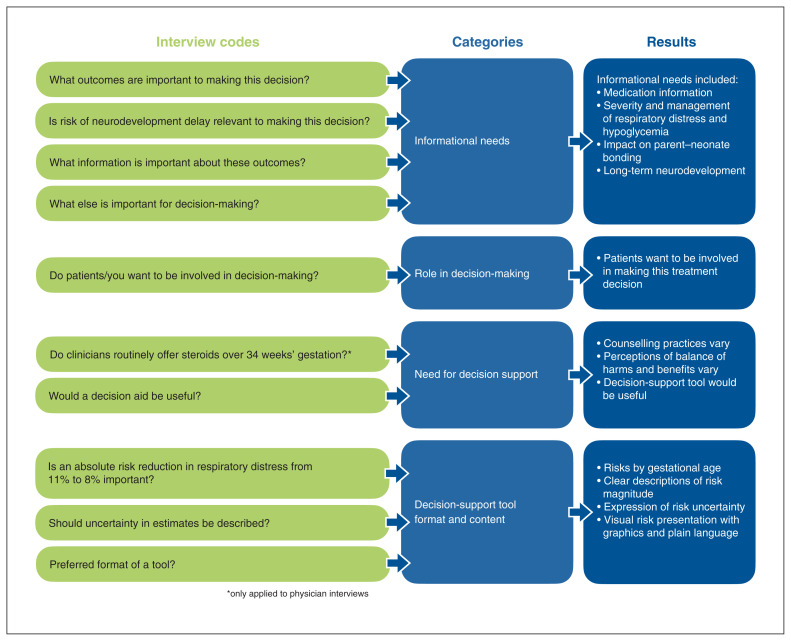

We organized data into the following framework categories: informational needs to decide whether to administer antenatal corticosteroids; preferences for decision-making roles regarding this treatment; need for support to make this treatment decision; and preferred format and content of a decision-support tool (Figure 1). We elaborate on each category below and provide illustrative quotes in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Figure 1:

Summary of categories in analytic framework. Coded interview data were charted to, then interpreted within, categories.

Table 2:

Illustrative quotes regarding informational needs

| Participant group | Quote |

|---|---|

| Pregnant participants | “I’d have more questions, more about the breathing problems … what that means, how long the baby would need to be in some kind of care unit. Can I take the baby home, or does it have to stay in hospital for a period of time? What’s the average or usual period of time … how long the period is of these concerns?” — Pr 2 “At first, low blood sugar does not sound scary. But … I’d need more clarification on what does that mean for a newborn?” — Pr 14 “[Hearing about neurodevelopmental outcomes] may or may not change the decision, but at least having, knowing that you made a decision based with as much information as you could possibly have.” — Pr 17 “[Patients] go home and do their own research and then come up with this, then they might want to hear it from the doctor first … rather than looking up something on Google and saying that ‘Oh, now my baby is gonna have, like, learning disability from getting the steroids,’ where you’re misinterpreting the information.” — Pr 20 |

| Obstetricians | “I talk about how the benefits would be decreased respiratory distress, decrease in intraventricular hemorrhage, and decrease in needing ventilation, and a decrease in NEC … over 34 weeks, there probably is a higher risk of hypoglycemia” — OB 7 “RDS and requiring oxygen or even CPAP or intubation … and time spent in NICU.” — OB 10 “Low blood sugar, like, that doesn’t really mean as much to [parents] as, like, oh, a small head or … lower test scores. … I think any evidence that there could be harm is concerning to a degree.” — OB 6 “I’m trying not to place too much emphasis on neurodevelopmental problems because it’s very fuzzy” — OB 5 |

| Pediatricians | “Hypoglycemia is bad. And that may be a risk for, that may be part of the long-term risks for the developing brain … If you monitor well, it should be preventable, minimized for the most part. … the neonatal or the perinatal brain is very vulnerable to that kind of insult.” — Peds 9 “There is absolutely nothing that proves [association of hypoglycemia and long-term neurodevelopmental outcome]. The only thing that is proven is an association between persistent, symptomatic, severe hypoglycemia and long-term outcome.” — Peds 7 “Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes are … a very challenging thing to study.” — Peds 1 “We have the same dilemma with postnatal corticosteroids, and we bring it up all the time. It’s out there. It’s in the literature. Someone will Google and find it. And we’ve, in our practice in the NICU, we’ve always been completely transparent. And I think parents understand the — they probably feel more reassured that we talk about it.” — Peds 9 |

Note: CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure, NEC = necrotizing enterocolitis, NICU = neonatal intensive care unit, OB = obstetrician, Peds = pediatrician, Pr = pregnant, RDS = respiratory distress syndrome.

Table 3:

Illustrative quotes regarding preferences for shared decision-making

| Participant group | Quote |

|---|---|

| Pregnant participants | “Given that we don’t know the long-term risks of antenatal steroids, and that this is later on where the benefits aren’t as clear, it becomes, I think, more of an individual choice into what is important to you. And so, it feels like something that I would be better suited to decide … with the doctor’s guidance and help.” — Pr 1 “I would prefer that they make the decision and counsel me through it … because I think it’s, it’s still a lot of information to parse.” — Pr 11 |

| Obstetricians | “Women are often more invested in the well-being of their infants than they are in their own well-being, so … I think they’d want to be part of the decision-making.” — OB 3 |

| Pediatricians | “I think especially at this gestation, families would want to be involved because it’s kind of, it’s less of a clear-cut area … it’s more a grey zone.” — Peds 6 “To put that onto a mom who’s staring down delivering a baby early and not knowing what that’s all going to mean, and so on — my guess is, honestly, most people put their faith in you [the doctor] to help make decisions.” — Peds 5 |

Note: OB = obstetricians, Peds = pediatricians, Pr = pregnant.

Table 4:

Illustrative quotes regarding the need for increased support in decision-making

| Theme and participant group | Quote |

|---|---|

| Obstetrician counselling | |

| Obstetricians | “To 34 and 6 [weeks’ gestation], I generally recommend steroids if I think that the patient is at high risk of delivering within 7 days.” — OB 7 “It’s in those cases [at 34 + 0 to 34 + 6 weeks’ gestation] that I would typically speak to MFM — just a phone call and ask their opinion. And I get varying opinions. It’s not consistent.” — OB 8 After 35 [weeks’ gestation], I wouldn’t necessarily even bring it up — unless the patient perhaps asked about it. […] After 36 weeks, I wouldn’t even bring it up.” — OB 6 [For 35 + 0 to 35 + 6 weeks’ gestation] “That’s my grey zone.” — OB 4 |

| Pediatricians | “I think it’s variable.” — Peds 8 “I certainly do not think there’s any consensus amongst them, so it’s very operator dependent, from what my experience is in coming and meeting these parents.” — Peds 6 |

| Balance of harms and benefits | |

| Pregnant participants | “The things that are mentioned seem very small and … relatively insignificant in comparison to the risk of a respiratory problem.” — Pr 17 “The neurodevelopment … that the baby’s brain is still developing, and those neural paths and everything is still developing … those would be the kind of risks that I’d be most concerned about.” — Pr 5 “I’m not sure. I really need some help to understand, long-term, which one is, which problem is worse, which one is harder treat … I’m unable to determine, you know, assign a greater weight to either problem.” — Pr 14 |

| Obstetricians | “Our Canadian organization and a lot of people in the world feel that the benefits outweigh the risks.” — OB 5 “I don’t think that there is a clear, obvious thing, where I say, ‘This is really bad, and this is the worse outcome you should be worried about.’ I think that the biggest risk is something that only the patient and her or his support network can understand, right?” — OB 7 |

| Pediatricians | “If this was a child that was otherwise going to have a totally normal respiratory course, we gave the antenatal corticosteroid just because that’s what we now do … they end up needing a nursery stay for hypoglycemia. That seems like morbidity, to me, in a child that otherwise … may not have happened for.” — Peds 1 |

| Utility of decision support tool | |

| Pregnant participants | “I could go away, read it, talk it over with my husband … cover enough of the considerations that I wouldn’t feel like I need to go down the rabbit hole of going through the Internet, finding information that I may or may not trust.” — Pr 2 |

| Obstetricians | “What would be really helpful is something more geared towards physicians about how to understand the risks and benefits … that would be really helpful for me in order to have a conversation where I felt a bit more confident in being able to make a recommendation or being able to present all the data … if somebody wanted something to read about or to think about, then you could give it to them. They could read it on their own with their partner, with their family, and then come back to you with other questions … There may be two opportunities. One is a way to provide the information to clinicians.” — OB 7 |

| Pediatricians | “We kind of take for granted that, for us, the routine, the mundane, is all new to them, and it’s always anxiety-inducing. We know what happens when we’re anxious. Things get shut down. Information isn’t fully processed, but the tools sometimes, it’s something concrete that they reference back to.” — Peds 8 |

Note: MFM = maternal–fetal medicine, OB = obstetricians, Peds = pediatricians, Pr = pregnant.

Table 5:

Illustrative quotes regarding the preferred format and content of a decision-support tool

| Theme and participant group | Quote |

|---|---|

| Information format: numerical risks | |

| Pregnant participants | “I think saying the range is from 6 to 10 would also be meaningful.” — Pr 11 [Presenting risk uncertainty] “might just start to make everything kind of hazy.” — Pr 1 “Interested in the number of participants in the study … It makes a big difference when you are telling the story of 1 person versus analyzing the data of a province.” — Pr 15 “I might just want to know … if a baby is born at 35 weeks or 36 weeks, how many of them do have breathing problems?” — Pr 11 “The 30 percent [relative risk reduction] would be, I would feel, like ‘Yeah, that’s worth it’. … going from 11 to 8 [absolute risk reduction per 100 deliveries], I don’t know.” — Pr 10 |

| Obstetricians | “I find that patients, when they see a range, they focus on one number. And depending on their context, it could be the lower number or the high number.” — OB 2 “I think relative risk reduction from the patient’s perspective probably is more impactful.” — OB 8 “A number needed to treat, for me, is a very helpful number because I think it’s easy to communicate to patients and it’s easy for me to contextualize what that means … and a number needed to harm.” — OB 7 |

| Pediatricians | “All these 95 percent confidence intervals … too complicated for the general people to understand” — Peds 4 “Doesn’t necessarily need to be, like, written on the algorithm … there’s always uncertainty, and so, that’s just part of medicine.” — Peds 1 “What I’m guessing would be relevant to say is that ‘The risk of your baby having, needing to go to the NICU for respiratory distress would go from X percent to X percent’ … the risk without the intervention, the risk with the intervention.” — Peds 9 “Absolute risks are probably the most useful … it’s like, ‘This is a real possibility’.” — Peds 1 |

| Information format: visual | |

| Pregnant participants | “I like to see, like, a visual representation … to see ‘What are the possibilities?’” — Pr 17 “A flow chart, easy … ‘I’m in this pathway. I belong in this category.’ … ‘Okay what are the important points to know when being in that category?’” — Pr 6 “Something I could take away with me, something I could scribble on, whatever, write some notes on, write some questions on, and then bring that back with me.” — Pr 2 “Access to as much information as I wanted in the form of references, and I’d probably dive deep if I was concerned or not so deep if I wasn’t concerned.” — Pr 4 |

| Obstetricians | [Describing a visual tool with icons and colors] “Visual tools like that are really good because you can talk, talk, talk, but, you know, it’s just another way of presenting the information.” — OB 1 “Give a patient information in a way that lays it out in easy-to-understand ways … uses plain language and is something that you could sort of go through with the patient.” — OB 6 |

| Pediatricians | “Endorsed resources that if they want to take a little bit more on and read, they can.” — Peds 8 |

Note: OB = obstetricians, NICU = neonatal intensive care unit, Peds = pediatricians, Pr = pregnant.

Informational needs

Illustrative quotes are in Table 2. Many pregnant participants stated they would want to know the logistics of administration, adverse effects, contraindications, interactions, mechanism of action and cost of antenatal corticosteroids.

Almost all pregnant participants wanted to know about the range of severity and management of both respiratory outcomes and hypoglycemia (Table 2, pregnant participants 2 and 14). Many also wanted to know about impacts on admissions to the neonatal intensive care unit, parent–child bonding and long-term complications. All obstetricians reported discussing respiratory benefits (Table 2, obstetricians 7 and 10) in their counselling about antenatal corticosteroids in late preterm gestation. Some, but not all, discuss the increased risk of hypoglycemia (Table 2, obstetricians 7 and 6). Most obstetricians said patients should be made aware of possible intensive care and impacts on parent–child bonding (Table 2, obstetrician 10). Pediatricians also discussed these outcomes, except many said it was important to discuss the management and importance of hypoglycemia, but others said the information regarding this outcome was controversial (Table 2, pediatricians 9 and 7).

Most pregnant participants said knowing about neurodevelopmental outcomes would help them feel informed in the decision (Table 2, pregnant participant 17). However, they were divided on whether this information would ultimately change their decision. Notably, participants said it would be important to discuss these outcomes with their health care provider instead of coming across the information independently (i.e., online) (Table 2, pregnant participant 20).

About half of obstetricians said it was difficult to counsel patients on neurodevelopmental outcomes because of the uncertainty of the evidence, but most said it should be discussed (Table 2, obstetricians 6 and 5). Pediatricians also indicated that the evidence on neurodevelopmental outcomes was uncertain, noting division within their practice communities about how to interpret it, the poor quality of current evidence and the difficulty in obtaining quality data on child development (Table 2, pediatricians 1 and 9).

Preferences for decision-making roles

Illustrative quotes are in Table 3. Except for 1 pregnant participant who said they would want the doctor to make the decision about administration of antenatal corticosteroids in late preterm gestation (Table 3, pregnant participant 11), all others wanted to be involved in the decision (Table 3, pregnant participant 1). Some stated they would want the physician’s opinion and rationale to help decide.

One pediatrician stated that many patients facing a preterm delivery want the physician to help make clinical decisions (Table 3, pediatrician 5). All other physicians thought patients preferred to be involved in decision-making (Table 3, obstetrician 3 and pediatrician 6); many said this is especially true in this “grey zone,” where the balance of harms and benefits was less clear.

The need for increased support in decision-making

Illustrative quotes are in Table 4. Obstetricians had varied counselling practices regarding antenatal corticosteroids in late preterm gestation (Table 4, obstetricians 7, 8, 6 and 4), which was also observed by pediatricians (Table 4, pediatricians 8 and 6). Only half the obstetricians stated they routinely offered antenatal corticosteroids to patients in the 34th week of gestation (34 + 0 to 34 + 6 weeks’ gestation) who were at high risk of preterm birth. In the 35th week, most obstetricians stated they did not routinely offer antenatal corticosteroids, while some offered them in select circumstances. In the 36th week, none of the obstetricians routinely offered antenatal corticosteroids.

Participants had varied perceptions of the balance of benefits and harms of antenatal corticosteroids in late preterm gestation. Around half of pregnant participants felt that benefits outweighed harms because of the manageability of hypoglycemia, the uncertainty of the evidence on neurodevelopment and the immediacy of respiratory outcomes (Table 4, pregnant participant 17). The other pregnant participants stated they would choose not to administer antenatal corticosteroids because their harms — particularly potential neurodevelopmental effects — outweighed benefits (Table 4, pregnant participant 5) or stated they were unsure of what they would decide (Table 4, pregnant participant 14). Perceptions of the harm–benefit balance also differed among obstetricians and pediatricians, with some saying the benefits outweighed manageable and uncertain harms, and others saying that the possibility for harm outweighed an insubstantial benefit (Table 4, obstetricians 5 and 7, and pediatrician 1).

Most participants said a decision-support tool would be useful in deciding whether to administer antenatal corticosteroids in late preterm gestation. Pregnant participants said it would be a useful reference document after the clinical encounter (Table 4, pregnant participant 2). Several physicians mentioned the same (Table 4, obstetrician 7 and pediatrician 8), as well as the value of a separate tool designed for physicians, as a counselling guide with discussion points and risk information (Table 4, obstetrician 7). A few physician and pregnant participants did not think that — or were unsure if — a tool would help decision-making.

The preferred format and content of a decision-support tool

Illustrative quotes are in Table 5. Physician and pregnant participants stated that it was important for a decision-support tool to include gestational age–specific baseline risks of outcomes and effects of antenatal corticosteroids (Table 5, pregnant participant 11). Although relative risks were described as more impactful than absolute risks, responses varied on whether absolute or relative risk measures were more helpful in risk communication (Table 5, pregnant participant 10, obstetricians 8 and 7, and pediatricians 9 and 1).

Many pregnant participants stated that presenting a range of risk estimates would be meaningful if there was uncertainty about the point estimate (Table 5, pregnant participant 11). Some said that presenting confidence intervals would be confusing and would not help decision-making, but that uncertainty should be expressed somehow (e.g., noting limited sample size) (Table 5, pregnant participants 1 and 15). Most obstetricians and pediatricians said that presenting confidence intervals in decision-support tools for patients would not be helpful, adding that confidence intervals could be confusing (Table 5, pediatrician 4), could lead patients to focus on one end of the interval (Table 5, obstetrician 2) or were unnecessary to report because uncertainty is intrinsic to medicine (Table 5, pediatrician 1). In contrast, for decision-support tools for physicians, most physicians favoured inclusion of confidence intervals.

Physician and pregnant participants preferred graphical representations of risk and plain language, saying this would make complex information easier to understand (Table 5, pregnant participants 17 and 6, and obstetricians 1 and 6). They also suggested a hard-copy format (Table 5, pregnant participant 2) with inclusion of endorsed references (Table 5, pregnant participant 4 and pediatrician 8).

Interpretation

In this study, obstetricians reported varied counselling when discussing antenatal corticosteroids in late preterm gestation with patients, and less counselling at later preterm gestations. Although these findings are somewhat expected, given the current Canadian clinical practice guideline, they also suggest that some eligible pregnant people may be receiving variable information about this treatment or may not have a chance to participate in making this decision at all. However, almost all pregnant participants preferred to have a role in decision-making about this treatment, and after discussing harms and benefits, only half stated they would want the medication.

Previous studies have also shown that patients prefer shared decision-making in maternity care.14 Although patient decision aids have been developed and evaluated to improve decision-making for several interventions in obstetrics and gynecology,15 these efforts have primarily targeted decisions that usually do not have to be made in an acute clinical context and are often assumed to be driven by patient values (e.g., invasive prenatal testing). In contrast, the decision to administer antenatal corticosteroids is often made acutely.16 However, our findings show that clinicians and patients may benefit from improved support when deciding whether to administer antenatal corticosteroids in late preterm gestation.

Most participants thought a decision-support tool would help guide counselling and decision-making. Participants had variable preferences for the presentation of risks and uncertainty. However, previous studies have shown limited statistical literacy in interpreting absolute and relative risk comparisons among patients and obstetrician–gynecologists.17–20 Current guidance regarding risk communication suggests the use of absolute risks and representation of uncertainty by using confidence intervals with explanations or by specifying sample sizes and quality of studies.17–19,21–23

Previous quantitative studies for decision-making for antenatal corticosteroids have included a Markov decision analysis model to optimize timing of antenatal corticosteroids (i.e., immediate v. delayed administration after deciding that treatment is warranted),24 and a decision tree model to assess administration of antenatal corticosteroids in the context of maternal infection with SARS-CoV-2.25 Our use of semistructured interviews and framework analysis with patients, obstetricians and pediatricians allowed us to explore diverse perspectives and ensure participants understood the decision problem, while still effectively answering the main study questions.

Limitations

Physician participants were from a single tertiary teaching hospital, and pregnant participants had high levels of education, both of which may limit the generalizability of our results.26 We did not collect information on race, ethnicity or other sociodemographic details that may influence perspectives. In addition, we described a hypothetical situation to pregnant participants; their perspectives may differ from those of pregnant patients facing an actual, imminent risk of late preterm birth. An area for future research is to understand patient and physician perspectives on what it means to be at high risk for preterm birth; achieving the optimal timing for administration of antenatal corticosteroids (within 7 days of delivery) is a ubiquitous clinical challenge, which adds complexity to discussing risks and decision-making.

Conclusion

Pregnant people and physicians would likely benefit from increased support to consider the harms and benefits of late preterm antenatal corticosteroids and to decide whether they should be administered.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: Jason Burrows is a committee chair with the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada; regional division head of Maternal–Fetal Medicine with Fraser Health; regional department head and program medical director of the Maternal, Infant, Child and Youth (MICY) program with Fraser Health; chair of the quality management committee of the MICY program with Fraser Health; board member with the Canadian Obstetrics and Gynecology Review Program; and member of the department executive of the University of British Columbia Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Amelie Boutin reports a research scholar award from Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All authors contributed to study conception and design. Hannah Foggin and Jessica Liauw contributed to data collection. Hannah Foggin, Rebecca Metcalfe and Jessica Liauw made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. All of the authors revised it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This study was supported by the D.A. Boyes Memorial Award, from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of British Columbia.

Data sharing: In accordance with the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board, only members of the research team have access to the data.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/11/3/E466/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, et al. Antenatal betamethasone for women at risk for late preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1311–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crowther CA, Middleton PF, Voysey M, et al. Effects of repeat prenatal corticosteroids given to women at risk of preterm birth: an individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16:1–25. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asztalos EV, Murphy K, Willan A, et al. Multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroids for preterm birth study: outcomes in children at 5 years of age (MACS-5) JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:1102–10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts D, Brown J, Medley N, et al. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3:CD004454. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004454.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerstjens JM, Bocca-Tjeertes I, de Winter A, et al. Neonatal morbidities and developmental delay in moderately preterm-born children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e265–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Lackritz E. Epidemiology of late and moderate preterm birth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;17:120–5. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaempf JW, Suresh G. Antenatal corticosteroids for the late preterm infant and agnotology. J Perinatol. 2017;37:1265–7. doi: 10.1038/jp.2017.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 713: Antenatal corticosteroid therapy for fetal maturation. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:102–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skoll A, Boutin A, Bujold E, et al. No. 364-antenatal corticosteroid therapy for improving neonatal outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018;40:1219–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2018.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brotto LA, Branco N, Dunkley C, et al. Risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and sexual health: a qualitative study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34:172–8. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35160-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maxwell E, Mathews M, Mulay S. The impact of access barriers on fertility treatment decision making: a qualitative study from the perspectives of patients and service providers. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018;40:334–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metcalfe RK. Patient-oriented research to support decision-making in pregnancy hypertension [dissertation] Vancouver: University of British Columbia; 2021. Aug 19, [accessed 2023 May 9]. Available: https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0401459. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013 Sep 18;13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vedam S, Stoll K, McRae DN, et al. Patient-led decision making: measuring autonomy and respect in Canadian maternity care. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102:586–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poprzeczny AJ, Stocking K, Showell M, et al. Patient decision aids to facilitate shared decision making in obstetrics and gynecology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:444–51. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Travers CP, Clark R, Spitzer A, et al. Exposure to any antenatal corticosteroids and outcomes in preterm infants by gestational age: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;356:j1039. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malenka DJ, Baron JA, Johansen S, et al. The framing effect of relative and absolute risk. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:543–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02599636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berry DC, Knapp P, Raynor T. Expressing medicine side effects: assessing the effectiveness of absolute risk, relative risk, and number needed to harm, and the provision of baseline risk information. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller YD, Holdaway W. How communication about risk and role affects women’s decisions about birth after caesarean. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson BL, Gigerenzer G, Parker S, et al. Statistical literacy in obstetricians and gynecologists. J Healthc Qual. 2014;36:5–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2011.00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trevena LJ, Zikmund-fisher BJ, Edwards A, et al. Presenting quantitative information about decision outcomes: a risk communication primer for patient decision aid developers. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bansback N, Harrison M, Marra C. Does introducing imprecision around probabilities for benefit and harm influence the way people value treatments? Med Decis Making. 2016;36:490–502. doi: 10.1177/0272989X15600708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpkin AL, Armstrong K. Communicating uncertainty: a narrative review and framework for future research. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:2586–91. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04860-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lapinsky SC, Wee WB, Penner M. Timing of antenatal corticosteroids for optimal neonatal outcomes: a Markov decision analysis model. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2022;44:482–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2021.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Packer CH, Zhou CG, Hersh AR, et al. Antenatal corticosteroids for pregnant women at high risk of preterm delivery with COVID-19 infection: a decision analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:1015–21. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1713145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin LT, Ruder T, Escarce JJ, et al. Developing predictive models of health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1211–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1105-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.