Abstract

Backgrounds

Due to immaturity of their immune system, passive maternal immunization is essential for newborns during their first months of life. Therefore, in the current context of intense circulation of SARS-CoV-2, identifying factors influencing the transfer ratio (TR) of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 (NAb) appears important.

Methods

Our study nested in the COVIPREG cohort (NCT04355234), included mothers who had a SARS-CoV-2 PCR positive during their pregnancy and their newborns. Maternal and neonatal NAb levels were measured with the automated iFlash system.

Results

For the 173 mother-infant pairs included in our study, the median gestational age (GA) at delivery was 39.4 weeks of gestation (WG), and 29.7 WG at maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection. Using a multivariate logistic model, having a NAb TR above 1 was positively associated with a longer delay from maternal positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR to delivery (aOR 1.09, 95% CI: 1.03 – 1.17) and with a later GA at delivery (aOR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.09 – 2.52). It was negatively associated with being a male newborn (aOR 0.21, 95% CI: 0.07 – 0.59). In 3rd trimester SARS-CoV-2 infected mothers, NAb TR was inferior to VZV, toxoplasmosis, CMV, measle and rubella‘s TR. However, in 1st or 2nd trimester infected mothers, only measle TR was different from NAb TR.

Conclusion

Male newborn of mothers infected by SARS-CoV-2 during their pregnancy appear to have less protection against SARS-CoV-2 in their first months of life than female newborns. Measle TR was superior to NAb TR even in case of 1st or 2nd trimester maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection. Future studies are needed to investigate possible differences in transmission of NAb following infection vs vaccination and its impact on TR.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Pregnancy, Neutralizing antibodies, Transplacental transmission, Newborn

Summary.

Using an automated system to measure neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 (NAb) in sera of mothers infected during their pregnancy and their newborns, we found out the NAb transfer ratio (TR) was impacted by the delay from infection to delivery, the gestational age at delivery and the newborn sex. This NAb TR was inferior to the one of various other pathogens tested when SARS-CoV-2 infection occurred in 3rd trimester of pregnancy and only inferior to measle TR when SARS-CoV-2 infection occurred in 1st or 2st trimester. Future studies are needed to investigate possible differences in antibodies transmission following infection vs vaccination.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Backgrounds

Maternal-fetal transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is a rare event and our main concern is the occurrence of infection of an insufficiently immunized neonate by his surroundings and its potential complications [1]. Newborn and infants are reported to be mainly asymptomatic or presenting mild to moderate symptoms. However, compared to other children, a younger age at infection and being a male seem to be risk factors of severity [2,3,4].

Due to the immaturity of their immune system, neonates and infants rely on maternal antibodies to defend themselves against infections. Transplacental transfer begins at around 8 to 10 weeks of gestation (WG) and accelerates in the 3rd trimester, resulting in IgG levels of full-term newborns exceeding those of their mothers [5]. Thus, transfer ratio (TR) of maternal antibodies is reported to be negatively impacted by prematurity [6]. As for other pathogens, anti-SARS-CoV-2 and especially anti-RBD IgG are detected in neonates. A significant positive correlation between IgG anti-RBD in maternal and cord blood sample was reported by Song et al. as well as by Flannery et al. and an association between increased TR and longer time from infection to delivery seems to stand out [7,8].

However, information and factors impacting mother to fetus transfer of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 (NAb) which presence is often correlated with protective immunity [9], remain scarce. This may be mainly due to the conventional virus neutralization test considered as the gold standard which is time-consuming and requires a biosafety level 3 laboratory [10]. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), and ELISA variants can detect anti-S or anti-RBD Ab with high sensitivity but vary in their ability to predict NAb activity, so the results may not directly correlate with protection [11,12]. During the present study we used a surrogate virus neutralization test to evaluate the NAb TR in case of infection during pregnancy, explore its enabling or limiting factors, and compare it to the TR of total antibodies against other pathogens [13].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

We conducted a study nested in the COVIPREG cohort (Prevalence and consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women, the fetus and the newborn, NCT04355234, [14]) which inclusions took place from April 2020 to January 2021 in 9 maternity hospitals in Paris area. This time period includes the two first waves of COVID-19 in France, before vaccine availability. Our work focused on patients who had a symptomatic or non-symptomatic infection confirmed by positive PCR during their pregnancy (Group 3) and for whom maternal and cord blood serum were available. Within the COVIPREG study, maternal and cord blood serum were collected at delivery and stored frozen until analysis. Twin pregnancies were excluded.

Maternal and neonatal information were taken from the COVIPREG data collection in agreement with the scientific committee.

2.2. Antibody measurement

Antibodies measurements were performed on serum from maternal and cord blood punction between January and May 2022. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 NAb testing was performed by immunochimiluminescence using the iFlash-2019-nCoV Neutralization antibody assay on the iFlash analytical system (Shenzhen YHLO Biotech Co. Ltd, Guangdong, China) that was designed to detect total NAbs in an isotype and species-independent manner and can be completed in a biosafety level 2 laboratory; with a positivity threshold of 10 AU/mL.

Measurements of anti-N (positivity threshold ≥ 1 U/mL) and anti-S (positivity threshold ≥ 0.8 U/mL) antibody levels were carried out on the Cobas immunoanalytical instrument (Roche diagnostics, Meylan, France) by electrochemiluminescence. Measurements of antibody levels against pathogens other than SARS-CoV-2 were performed by chemiluminescence on the Liaison XL instrument (Diasorin®, Saluggia, Italy) with the following positivity thresholds: anti-toxoplasmosis IgG ≥ 8.8 IU/mL, anti-CMV IgG ≥ 14 U/mL, anti-measles IgG ≥ 16. 5 AU/mL, anti-rubella IgG ≥ 10 IU/mL, and anti-VZV IgG ≥ 150 mIU/mL.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Newborns antibody titers were measured for the different pathogens only in those whose mothers had an antibody titer above the threshold of positivity of the related pathogen.

Antibodies TR were calculated by dividing the neonatal cord blood antibody titer by the maternal blood antibody titer. We removed mother-infant pair from the TR determination when we were not able to measure it because newborns antibodies levels were out of the linearity limit of the instrument or mothers’ antibodies limits were above. We kept in the TR determination the mother-infant pair when neonates had antibodies levels that were under the threshold of positivity but in the linearity limit of the automated system.

Maternal and neonatal characteristics are given as median with interquartile range (IQR) or proportions with percentage (%). Spearman's coefficient correlation (non-parametric) between maternal and neonatal NAb serum concentration, between NAb TR and delay from maternal PCR positive to delivery, were estimated.

Comparison of TR between other pathogens and NAb or anti-N or anti-S were performed by Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests (non-parametric tests) with adjusted p-values by Bonferroni test in couples having TR values for each of the pathogens compared two by two.

To determine factors associated with a NAb TR ≥ 1, we used a multivariate logistic regression with a backward step-by-step model integrating factors with a p-value < 0.2 in the univariate analysis. The adjusted odd-ratios were estimated with their confidence interval at 95%.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, R 4.1.2 software was used to perform analyses. The primary author and a dedicated statistician performed the analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

Among 310 patients included in the 3rd group of the COVIPREG study, we included 173 mother – infants’ pairs in our study. Maternal and neonatal prevalences as well as TR available according to each pathogen are presented in Table 1 (and supplementary appendix 1).

Table 1.

Maternal and neonatal prevalence and TR available for each pathogen tested.

| Maternal prevalence: | Prevalence of newborns of positive mothers * | Number of transfer ratio available: ⁎⁎ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rubella | 138 / 173 (80%) | 133 / 135 (98.5%) | 130 pairs |

| Measles | 138 / 173 (80%) | 132 / 137 (96.4%) | 81 pairs |

| CMV | 135 / 173 (78%) | 131 / 132 (99.2%) | 115 pairs |

| Toxoplasmosis | 52 / 173 (30%) | 47 / 51 92.2%) | 47 pairs |

| VZV | 164 / 173 (95%) | 156 / 161 (96.9%) | 161 pairs |

| SARS-CoV-2 anti-N | 137 / 173 (79%) | 119 / 136 (87.5%) | 136 pairs |

| SARS-CoV-2 anti-S | 142 / 173 (82%) | 135 / 142 (95.1%) | 121 pairs |

| Nab | 107 / 173 (62%) | 76 / 105 (71.4%) | 94 pairs |

Exclusion for insufficient volume of neonatal samples: N = 14 (Rubella n = 3, Measles n = 1, CMV n = 3, Toxoplasmosis n = 1, VZV n = 3, Anti-N n = 1, Anti-S n = 0, NAb n = 2).

Exclusion of LOQ samples (LOQ limit of quantification): N = 112 (Rubella: n = 1 pair > 350 IU/mL + n = newborns 4 > 350 IU/mL ; Measles: n = 37 pairs > 300 AU/mL + n = 18 newborns > 300 AU/mL + 1 newborn 〈 5 AU/mL; CMV: n = 11 pairs 〉 180 U/mL + n = 1 mother > 180 U/mL + n = 5 newborns > 180 U/mL; Toxoplasmosis: n = 2 newborns > 400 IU/mL + n = 2 mothers > 400 IU/mL; SARS-CoV-2 anti-S: 7 newborns 〈 0.39 U/mL, 2 mothers 〉 243 U/mL, 2 newborns > 243 /mL, 8 pairs > 243 /mL; NAb: n = 1 pair > 800 AU/mL + n = 1 newborn > 800 AU/mL+ n = 9 newborns < 4 AU/m).

Median gestational age (GA) at delivery was 39.4 [38.6–40.4] WG. Delay from infection to delivery was available for 163/173 (94.2%) mothers and its median was 9 WG [3.5–16.5], 109/151 (72.2%) mothers were symptomatic, and 26 / 173 (15%) needed hospitalization (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Maternal characteristics of the 173 pregnant women in the CompaCoV study.

| Maternal characteristics N = 173 | Median (IQR); n / N (%) |

|---|---|

| Maternal Age (years) | 32.0 [28.0–36.0] |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| < 25 | 96 / 173 (55%) |

| ≥ 25 | 77 / 173 (45%) |

| Tobacco use | |

| Never | 150 / 172 (87%) |

| Stop, before pregnancy | 12 / 172 (7.0%) |

| Stop, during pregnancy | 2 / 172 (1.2%) |

| Yes, smoking | 8 / 172 (4.7%) |

| Difficult psychosocial conditions | 6 (3.5%) |

| Number of previous pregnancies | |

| 0 | 41 / 173 (24%) |

| 1 | 29 / 173 (17%) |

| 2 | 42 / 173 (24%) |

| ≥ 3 | 61 / 173 (35%) |

| Comorbidities prior to pregnancy | 47 / 171 (27%) |

| Pathologies during pregnancy | 81 / 172 (47%) |

| Gestational diabetes or unbalanced pre-existing diabetes | 40 / 172 (23%) |

| Gestational age (GA) at delivery (WG) | 39.4 [38.6–40.4] |

| Gestational age (GA) at infection (WG) | 29.7 [22.9–35.5] |

| Not available | 10 |

| Delay between infection and delivery (WG) | 9.00 (3.5, 16.5) |

| Not available | 10 |

| SARS-CoV-2 Symptoms | 109 / 151 (72%) |

| fever | 35 / 151 |

| cough | 42 / 151 |

| anosmia or ageusia | 53 / 151 |

| diarrhea | 8 / 151 |

| vomiting | 8 / 151 |

| severe headache | 15 / 151 |

| others | 78 / 151 |

| SARS-CoV-2 hospitalization | 26 / 173 (15%) |

| Oxygenotherapy | 13 / 26 |

| ICU | 5/26 |

Concerning newborns: 160/173 (92.5%) were born at term, 76/173 (44%) were female, and the median weigh at birth was 3260 g [2930–3560] (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Neonatal characteristics of the 173 newborns in the CompaCoV study.

| Neonatal characteristics N = 173 | Median (IQR); n / N (%) |

|---|---|

| Prematurity [32–37) WG | 8 / 173 (4.6%) |

| Prematurity < 32 WG | 5 / 173 (2.9%) |

| Newborn sex | |

| Female | 76 / 173 (44%) |

| Male | 97 / 173 (56%) |

| Newborn weight at delivery (g) | 3260.0 [2930.0–3560.0] |

| Apgar at 5 min | |

| [6,7[ | 2 / 172 (1.2%) |

| [7,10] | 170 / 172 (99%) |

| Delivery mode | |

| cesarian section | 38 / 172 (22%) |

| Non-spontaneous vaginal delivery (forceps, spatula or suction cup) | 21 / 172 (12%) |

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 113 / 172(66%) |

| Neonatal resuscitation maneuvers at birth | 13 / 173 (7.5%) |

| Ventilation | 13/13 |

| Intubation | 3/13 |

| Neonatal transfer | |

| Neonatology (resuscitation or intensive care or routine care) | 18/173 (10%) |

| Mother and Child Unit | 13/173 (7.5%) |

| Neonatal respiratory disorder | 9 / 172 (5.2%) |

| resorption disorder | 6 / 9 |

| hyaline membrane disorder | 2 / 9 |

| meconium inhalation | 1 / 9 |

| Others | 3 / 9 |

| Breast-feeding | |

| Artificial breastfeeding | 18 171 (10%) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 117 171 (68%) |

| Mixed breastfeeding | 36 171 (21%) |

3.2. Factors associated with NAb TR

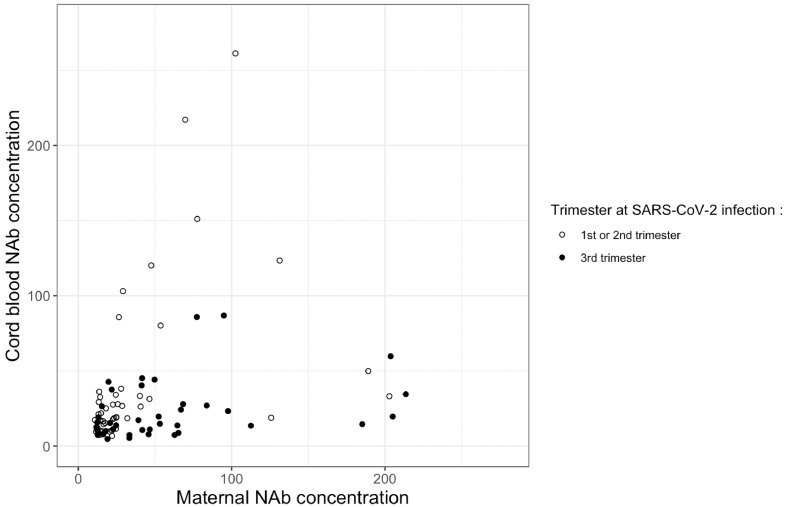

Out of 94 mother-infant pairs for which we were able to calculate NAb TR, information about delay from infection to delivery was available for 86 pairs. A significant correlation was estimated at 0.67 (p<0.001) between NAb concentration in cord blood sera and mother sera in mothers infected in the 1st or 2nd trimester, and estimated at 0.41 (p<0.01) in mothers infected in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Scatter plot of maternal and cord blood NAb with Spearman's correlation between NAb titer (AU/mL) in cord blood and mothers’ sera according to the trimester at SARS-CoV-2 infection. In 1st or 2nd trimester SARS-CoV-2 infection: N = 46, rho = 0.67, p < 0.001. In 3rd trimester SARS-CoV-2 infection: N = 40, rho = 0.41, p < 0.01. the empty dots represent the observed data for 1st and 2nd trimester at SARS-CoV-2 infection and the filled dots represent the 3rd trimester.

Median TR for NAb was 0.75 [0.38–1.17] on 94 mother – infant pairs, whom 30 had a TR ≥ 1. In multivariate analysis performed on 86 pairs: factors associated positively with a TR ≥ 1 were a longer delay from infection to delivery (aOR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.03 – 1.17) and a later GA at delivery (aOR = 1.58, 95% CI 1.09 – 2.52); being a male newborn was negatively associated with having a TR ≥ 1 (aOR = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.07 – 0.59) (AUC 0.8054, IC95% 0.6992–0.9116, Hosmer-Lemeshow test p = 0.037; univariate and multivariate results detailed in supplementary appendix 2). When comparing NAb TR by neonatal sex according to the trimester at infection we found a trend toward a better TR in female which was not significative after adjusting p-value by Holm (supplementary appendix 3). Concerning the other pathogens tested, we did not find significant differences in TR according to the newborn sex (Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests, supplementary appendix 4).

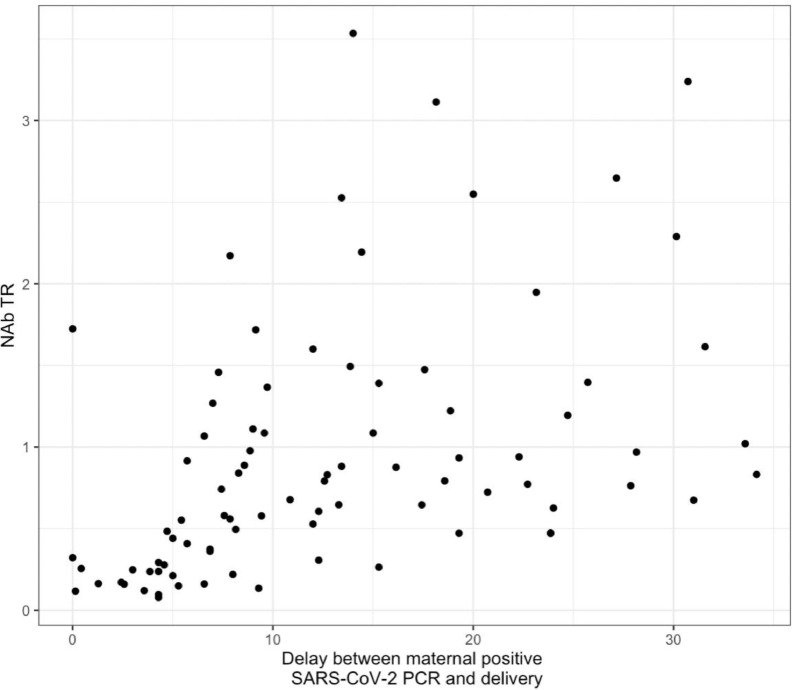

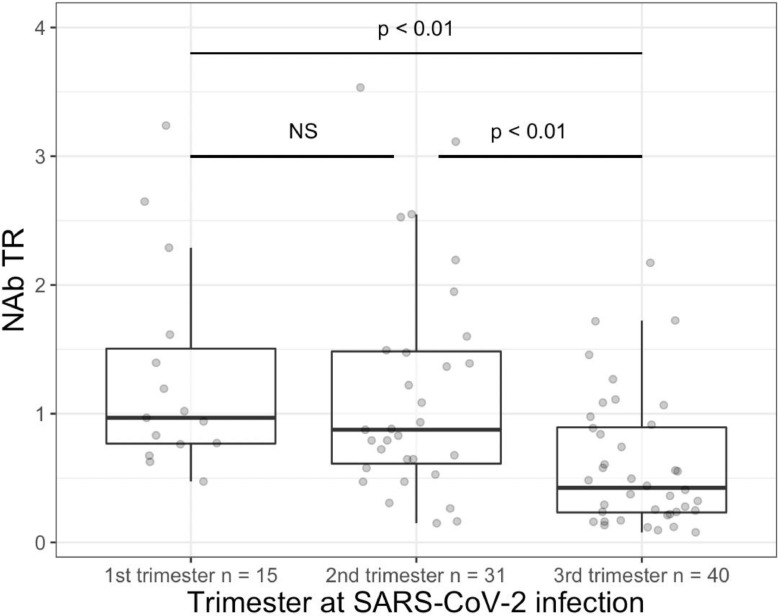

Likewise, we found a positive correlation (rho coefficient 0.58, p <0.001) between SARS-CoV-2 NAb TR and delay from infection to delivery (Fig. 2 ). SARS-CoV-2 NAb TR was significantly inferior in case of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the third trimester compared to 1st or 2nd trimester (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 2.

Scatter plot of NAb TR and delay from infection to delivery with the Spearman correlation: N = 86, rho coefficient = 0.58, p < 0.001.

Fig. 3.

Boxplot of NAb TR according to pregnancies’ trimester at SARS-CoV-2 infection. Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests, adjusted p-value by Holm, NS: non-significant test (lower hinge = 25% quantile, upper hinge = 75% quantile, lower whisker = smallest observation greater than or equal to lower hinge - 1.5 * IQR, upper whisker = largest observation less than or equal to upper hinge + 1.5 * IQR). the gray dots represent the observed data.

3.3. Comparison between SARS-CoV-2 NAb TR and other pathogens’ TR

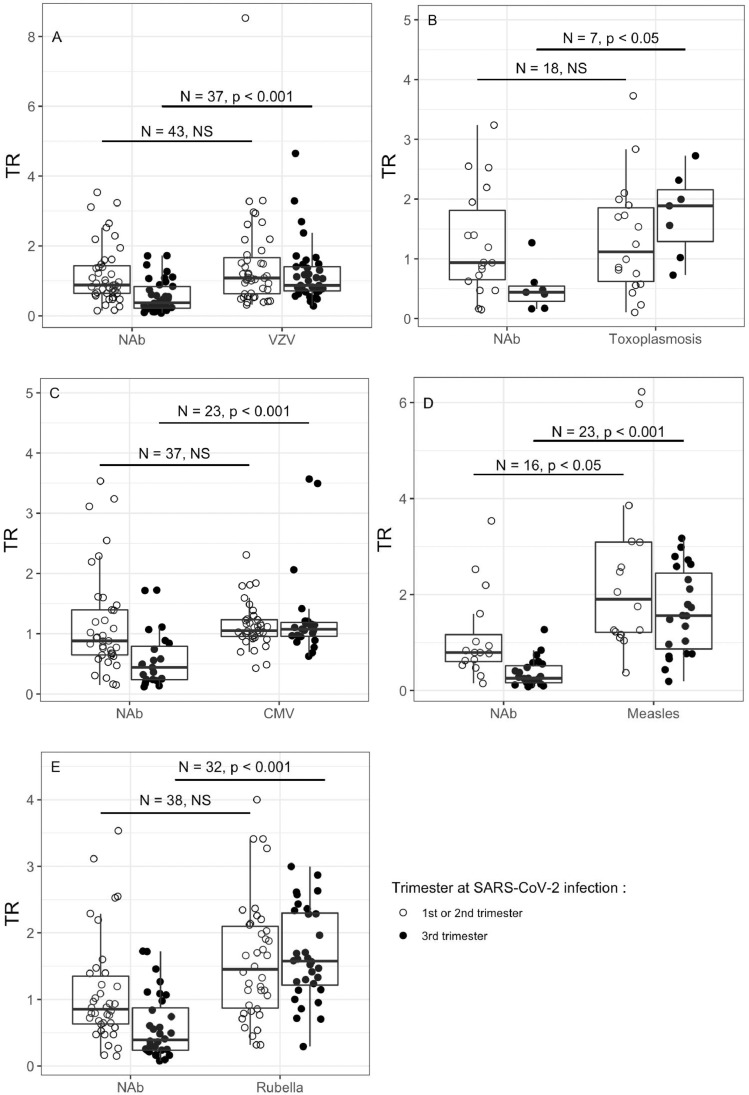

In patients infected in the 3rd trimester, TR of SARS-CoV-2 NAb were significantly inferior than those of total antibodies specific of rubella, measles, CMV, VZV and toxoplasmosis. When infected in the 1st or 2nd trimester, NAb TR was only significantly inferior to measles TR. (Fig. 4 A to Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Boxplot between TR and pathogens other than SARS-CoV or SARS-CoV-2 NAb according to patients' trimester at SARS-CoV-2 infection with the comparison using Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, adjusted p-value by Bonferroni (number of tests = 10). NS: non-significant test. Lower hinge = 25% quantile, upper hinge = 75% quantile, lower whisker = smallest observation greater than or equal to lower hinge - 1.5 * IQR, upper whisker = largest observation less than or equal to upper hinge + 1.5 * IQR. the empty dots represent the observed data for 1st and 2nd trimester at SARS-CoV-2 infection and the filled dots represent the 3rd trimester.

As for SARS-CoV-2 NAb, concerning mother infected in 3rd trimester anti-S TR was significantly reduced compared to the other pathogens’ TR tested except for toxoplasmosis, for which a small number of pairs were available. When infected in the 1st or 2nd trimester, the results were also slightly different from those of NAb, as anti-S TR was only significantly inferior to rubella TR (supplementary appendix 4A to 4E).

For anti-N, TR was significantly inferior than those of rubella, measle, CMV, VZV and Toxoplasmosis in patients infected in the 3rd trimester and there was no difference when infected in 1st or 2nd trimester (Supplementary 6A to 6E).

There was no significative difference in NAb TR versus anti-S or anti-N TR in mothers infected in 1st and 2nd trimester or in 3rd trimester (Supplemental appendix 7A and 7B).

4. Discussion

Our study aimed to investigate transplacental transfer of SARS-CoV-2 NAb in 94 mothers who were infected during their pregnancy. The NAb positivity threshold of 10 AU/mL, recommended by the manufacturer, has been described to have excellent agreement to the conventional neutralization assay in a previous study, however the accuracy of this threshold is variable in later studies which might recommend higher threshold [15,16,17,13] . We assume the choice of the 10 AU/mL even if it might have increased the number of mothers presenting Nab. Indeed, it has not really impacted the comparison with newborns as we were using ratios. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 NAb in mothers was slightly lower than SARS-CoV-2 anti-S or anti-N, and may be linked to the delay of apparition and detection of total antibodies versus NAb [18]. NAb levels in cord blood and maternal sera were correlated with a higher correlation when mothers were infected earlier in pregnancy. However this correlation was not as high as previously reported for total SARS-CoV-2 specific antibodies either after infection or vaccination [7,19,20].

We report a positive impact of a longer delay between infection and delivery on having a NAb TR ≥ 1, which is consistent with a previous study on 12 patients reporting a higher number of positive NAb rate in cord blood when the mothers where infected earlier in pregnancy [21]. This result is also consistent with previous studies on anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies reporting a correlation between the delay from positive PCR to delivery and anti-RBD TR on 26 pairs and a difference in TR according to trimester at infection on 65 pairs [8,19] . In vaccinated mother, it has also been reported a positive association between NAb TR and increased time since vaccination in 33 pairs [22]. However another study reported that infection-induced NAb TR was stable across gestation, and TR was maximal upon vaccination in the second trimester [23].

Similarly to what has been reported in another study, it seems that being a male newborn to a mother infected by SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy has a negative impact on SARS-CoV-2 specific antibodies TR [24]. The authors stand out as underlying mechanism the difference in antibody glycosylation and a lower maternal production of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 that could not be counteracted by up-regulation of placental FC-receptors in male fetuses [24]. However this observation is not consensual as no difference was reported in NAb activity, after exposure anytime during pregnancy, according to the sex of the fetus in another study [23]. The AUC of our multivariate model, finding the impact of the sex of the newborn on NAb TR in mother infected during pregnancy, was quite high taking into account the small number of events. Further studies should be carried out on a larger scale, indeed when disaggregating by trimester at infection we were not able to find any significant different between male and female TR probably due to a lack of power.

We report a correlation between maternal and neonatal NAb titers and it has been previously reported that SARS-CoV-2 specific antibodies titers were correlated with disease symptoms or severity [25,26]. On a small number of mothers – infants ‘ pairs, authors reported a significantly higher TR when mothers had a severe-critically symptomatic infection compared to mothers who were asymptomatic or mild-moderately symptomatic [7]. However, this result is not consensual as another study didn't report differences in maternal transplacental transfer depending on disease severity [27]. Likewise, we didn't find out any association between the presence of symptoms and having a TR ≥ 1 in multivariate logistic regression. Unfortunately, information about disease severity was not available in our data collection so we could not go further in our research by evaluating severity impact on NAb TR in symptomatic mothers.

We also report that in case of SARS-CoV-2 3rd trimester infection, NAb TR was inferior to those of other pathogens tested, as previously reported in comparison to influenzae and pertussis [28]. This difference is probably due to changes in SARS-CoV-2 antibodies glycosylation that were not totally balanced by Rc receptor regulation and possibly to the fact that influenza and pertussis vaccination were performed earlier in pregnancy than the occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 symptoms onset [28]. When infected in 1st or 2nd trimester, we report that SARS-CoV-2 NAb TR was inferior to measles TR, and that SARS-CoV-2 anti-S TR was inferior to rubella TR. These results raise questions about differential TR of antibodies following natural infection or vaccination. Firstly, it was previously reported in a study on 30 infected and 30 vaccinated pairs that vaccination and infection-elicited SARS-CoV-2 NAb might have different transfer kinetics and that transfer might be more efficient in vaccinated than in infected mothers [23]. Besides, long term immunity against measles was reported to have slight variation in IgG isotypes whether immunity stemmed from vaccination or natural infection [29]. Moreover apart from IgG1 that cross preferentially through the placenta, the order of the others isotypes is not consensual [30,31]. Therefore, it might be interesting to explore isotypes and type of antibodies glycosylation produced after infection and vaccination in short- and long-term immunity against various pathogens and their impacts on TR. As it has been suggested that FcRn could be saturated in case of hypergammaglobulinemia, we suppose that high concentrations of vaccine induced antibodies might possibly result in lower TR [32]. Therefore, it might also be interesting to explore the impact of SARS-CoV-2 and pertussis vaccination during pregnancy on other pathogens’ TR.

Our study presents strengths including its large number of mothers – infants ‘pairs for whom we measured NAb levels on automated system and for whom TR was available; its multicentric characteristic; and the important number of pathogens for which antibody levels were measured in sera enabling TR comparison between them and different types of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. However, it also has limitations. Among the mothers for whom information was collected, 72% had presented with symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection. This large percentage, compared to what has been described in the literature may be related to the fact that there was no systematic screening at delivery at the beginning of the inclusions, nor during pregnancy, with a potential screening bias in symptomatic patients [33,8]. However, presence of symptoms did not stand out as a factor impacting TR in multivariate analysis. Concerning newborns, our small number of preterm babies (13/173), did not allow us to perform subgroup analyses according to the GA at birth [34]. Another point is that NAbs is only a portion of total antibody response and thus comparing NAbs against SARS-CoV-2 TR to other pathogens total antibody response might induce bias. We didn't choose to do so due to the lack of automated measure of NAb against other pathogens. However, we didn't find any difference in NAb versus anti-S or anti-N TR in mother infected in 1st or 2nd trimester or in 3rd trimester. The last point is that we didn't evaluate other pathogens’ TR in a control group of mothers who weren't infected by SARS-CoV-2 during their pregnancy. However, our VZV, measle and rubella TR were close to those described earlier [6]. Nevertheless, even if previous studies didn't report changes in influenza and pertussis TR in case of SARS-CoV-2 infection it should be confirmed on a larger cohort with a control group [28,27].

5. Conclusion

Our study strengthens information about the possible difference in NAb TR in mother infected during pregnancy according to the sex of the fetus. This might be due to differentiated immune response, however further studies are needed to confirm these hypothesizes. Questions raised about a possible differentiated immune response to natural infection or vaccination and its impact on TR will need to be investigated in future studies; as well as the impact of vaccination during pregnancy on other pathogens’ TR.

Funding

Grant from the Groupe de Recherche sur les Infections pendant la Grossesse (GRIG).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The author, Diane Brebant, declare receiving a grant from the Groupe de Recherche sur les Infections pendant la Grossesse (GRIG) for this work.

Acknowledgments

Estelle Marcaut / Rahema Coriolan / Julie Tisserand / Florence Loiseau / Frederic Veillet

COVIPREG study : sponsor was Assistance Publique – Hopitaux de Paris (Delegation a la Recherche Clinique et al Innovation).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2023.105495.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Allotey J., Chatterjee S., Kew T., et al. SARS-CoV-2 positivity in offspring and timing of mother-to-child transmission: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-067696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Götzinger F., Santiago-García B., Noguera-Julián A., et al. COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: a multinational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2020;4:653–661. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouldali N., Yang D.D., Madhi F., et al. Factors associated with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatrics. 2021;147 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-023432. Available atAccessed 15 November 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodruff R.C., Campbell A.P., Taylor C.A., et al. Risk factors for severe COVID-19 in children. Pediatrics. 2022;149 doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-053418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fouda G.G., Martinez D.R., Swamy G.K., Permar S.R. The impact of IgG transplacental transfer on early life immunity. IH. 2018;2:14–25. doi: 10.4049/immunohorizons.1700057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van den Berg J.P., Westerbeek E.A.M., Smits G.P., van der Klis F.R.M., Berbers G.A.M., van Elburg R.M. Lower transplacental antibody transport for measles, mumps, rubella and varicella zoster in very preterm infants. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e94714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song D., Prahl M., Gaw S.L., et al. Passive and active immunity in infants born to mothers with SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flannery D.D., Gouma S., Dhudasia M.B., et al. Assessment of maternal and neonatal cord blood SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and placental transfer ratios. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:594–600. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luchsinger L.L., Ransegnola B.P., Jin D.K., et al. Serological assays estimate highly variable SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody activity in recovered COVID-19 patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58:e02005–e02020. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02005-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.2020. CDC. Labs.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/lab-biosafety-guidelines.html Available at. Accessed 22 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu W., Liu L., Kou G., et al. Evaluation of nucleocapsid and spike protein-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for detecting antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58:e00461. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00461-20. -20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manenti A., Maggetti M., Casa E., et al. Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies using a CPE-based colorimetric live virus micro-neutralization assay in human serum samples. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:2096–2104. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mouna L., Razazian M., Duquesne S., Roque-Afonso A.-M., Vauloup-Fellous C. Validation of a SARS-CoV-2 surrogate virus neutralization test in recovered and vaccinated healthcare workers. Viruses. 2023;15:426. doi: 10.3390/v15020426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsatsaris V., Mariaggi A.-A., Launay O., et al. SARS-COV-2 IgG antibody response in pregnant women at delivery. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2021;50 doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2020.102041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan K.-H., Leung K.-Y., Zhang R.-R., et al. Performance of a surrogate SARS-CoV-2-neutralizing antibody assay in natural infection and vaccination samples. Diagnostics. 2021;11:1757. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11101757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Favresse J., Gillot C., Di Chiaro L., et al. Neutralizing antibodies in COVID-19 patients and vaccine recipients after two doses of BNT162b2. Viruses. 2021;13:1364. doi: 10.3390/v13071364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saker K., Pozzetto B., Escuret V., et al. Evaluation of commercial Anti-SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody assays in seropositive subjects. J. Clin. Virol. 2022;152 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2022.105169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chvatal-Medina M., Mendez-Cortina Y., Patiño P.J., Velilla P.A., Rugeles M.T. Antibody responses in COVID-19: a review. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.633184. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.633184 Available at. Accessed 28 July 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beharier O., Plitman Mayo R., Raz T., et al. Efficient maternal to neonatal transfer of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. J. Clin. Invest. 2021;131 doi: 10.1172/JCI150319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prabhu M., Murphy E.A., Sukhu A.C., et al. Antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines in pregnant women and their neonates. Immunology. 2021 http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2021.04.05.438524 Available at. Accessed 20 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houhou-Fidouh N., Bucau M., Bertine M., et al. Preliminary results on transmission of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies to the fetus and serum neutralizing activity. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstetr. 2022 doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14185. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ijgo.14185 n/a. Available at. Accessed 8 April 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rottenstreich A., Zarbiv G., Oiknine-Djian E., et al. Timing of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy and transplacental antibody transfer: a prospective cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022;28:419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsui Y., Li L., Prahl M., et al. American Society for Clinical Investigation; 2022. Neutralizing Antibody Activity Against SARS-CoV-2 Variants in Gestational Age–Matched Mother-Infant Dyads After Infection Or Vaccination.https://insight.jci.org/articles/view/157354/pdf Available at. Accessed 28 July 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bordt E.A., Shook L.L., Atyeo C., et al. Maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection elicits sexually dimorphic placental immune responses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021;13:eabi7428. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abi7428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joseph N.T., Dude C.M., Verkerke H.P., et al. Maternal antibody response, neutralizing potency, and placental antibody transfer after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2021;138:189–197. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trinité B., Tarrés-Freixas F., Rodon J., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection elicits a rapid neutralizing antibody response that correlates with disease severity. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:2608. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81862-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edlow A.G., Li J.Z., Collier A.Y., et al. Assessment of maternal and neonatal SARS-CoV-2 viral load, transplacental antibody transfer, and placental pathology in pregnancies during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.30455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atyeo C., Pullen K.M., Bordt E.A., et al. Compromised SARS-CoV-2-specific placental antibody transfer. Cell. 2021;184:628–642.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isa M.B., Martínez L., Giordano M., Passeggi C., de Wolff M.C., Nates S. Comparison of Immunoglobulin G Subclass Profiles Induced by Measles Virus in Vaccinated and Naturally Infected Individuals. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2002;9:693–697. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.3.693-697.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malek A., Sager R., Kuhn P., Nicolaides K.H., Schneider H. Evolution of maternofetal transport of immunoglobulins during human pregnancy. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1996;36:248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1996.tb00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clements T., Rice T.F., Vamvakas G., et al. Update on transplacental transfer of IGG subclasses: impact of maternal and fetal factors. Front. Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01920. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01920 Available at. Accessed 7 April 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilcox C.R., Holder B., Jones C.E. Factors affecting the FcRn-mediated transplacental transfer of antibodies and implications for vaccination in pregnancy. Front. Immunol. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01294. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01294 Available at. Accessed 27 July 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allotey J., Stallings E., Bonet M., et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.ENP2016_rapport_complet.pdf. Available at: http://www.xn–epop-inserm-ebb.fr/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ENP2016_rapport_complet.pdf. Accessed 22 July 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.