Summary

Background

Gastric cancer (GC) is clinically heterogenous according to location (cardia/non-cardia) and histopathology (diffuse/intestinal). We aimed to characterize the genetic risk architecture of GC according to its subtypes. Another aim was to examine whether cardia GC and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC) and its precursor lesion Barrett’s oesophagus (BO), which are all located at the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ), share polygenic risk architecture.

Methods

We did a meta-analysis of ten European genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of GC and its subtypes. All patients had a histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma. For the identification of risk genes among GWAS loci we did a transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) and expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) study from gastric corpus and antrum mucosa. To test whether cardia GC and OAC/BO share genetic aetiology we also used a European GWAS sample with OAC/BO.

Findings

Our GWAS consisting of 5816 patients and 10,999 controls highlights the genetic heterogeneity of GC according to its subtypes. We newly identified two and replicated five GC risk loci, all of them with subtype-specific association. The gastric transcriptome data consisting of 361 corpus and 342 antrum mucosa samples revealed that an upregulated expression of MUC1, ANKRD50, PTGER4, and PSCA are plausible GC-pathomechanisms at four GWAS loci. At another risk locus, we found that the blood-group 0 exerts protective effects for non-cardia and diffuse GC, while blood-group A increases risk for both GC subtypes. Furthermore, our GWAS on cardia GC and OAC/BO (10,279 patients, 16,527 controls) showed that both cancer entities share genetic aetiology at the polygenic level and identified two new risk loci on the single-marker level.

Interpretation

Our findings show that the pathophysiology of GC is genetically heterogenous according to location and histopathology. Moreover, our findings point to common molecular mechanisms underlying cardia GC and OAC/BO.

Funding

German Research Foundation (DFG).

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Oesophageal adenocarcinoma, Genome-wide association study (GWAS), Transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS)

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed on June 30, 2022, to identify genetic risk variants and corresponding risk genes for gastric cancer that have been identified through genome-wide association studies. We did not apply any publication date restrictions. The search was restricted to papers published in the English language. Search terms were: (“gastric cancer” OR “gastric carcinoma” OR “gastric adenocarcinoma”) AND (“genome wide association study” OR “GWAS”). Nine genome-wide association studies for gastric cancer have been published to date in the East-Asian population and one in the European population. In none of these studies, patients’ tumours were characterised with regard to both subtypes, namely location (cardia/non-cardia) and histopathology (diffuse/intestinal). In addition, only one risk locus could be functionally characterized in these studies. The expression of the gene PSCA is regulated by an identified gastric cancer risk variant. Furthermore, it has not been examined so far whether gastric cancer at the cardia and oesophageal adenocarcinoma, which are both localised at the gastro-oesophageal junction, share genetic aetiology.

Added value of this study

Within a European consortium, we did a meta-analysis of ten datasets available to date from genome-wide association studies, including more than 16,000 individuals. We newly identified two and replicated five risk loci, all of them contribute subtype-specific risk to gastric cancer. For the identification of risk genes among the identified loci we used transcriptome-wide expression data from gastric corpus and antrum mucosa. This revealed that an upregulated expression of the genes MUC1, ANKRD50, PTGER4, and PSCA are plausible pathomechanisms at four risk loci. At another risk locus, we found that the blood-group 0 exerts protective effects for non-cardia and diffuse gastric cancer, while blood-group A increases risk for both subtypes. Furthermore, our data on cardia gastric cancer as well as oesophageal adenocarcinoma (26,000 individuals) showed that both cancer entities share genetic aetiology at the polygenic level and identified two new risk loci on the single-marker level.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our results highlight the genetic heterogeneity of gastric cancer and provide insights into distinct and shared aetiological processes underlying different gastric cancer subtypes. This should further help to elucidate the pathomechanisms underlying each gastric cancer subtype. The findings may also serve as basis for a more biologically driven stratification of gastric cancer in the clinical setting.

Introduction

Gastric adenocarcinoma, here called gastric cancer (GC), has a multifactorial aetiology and is clinically heterogeneous. Anatomically, GC is subdivided into a cardia and non-cardia type.1 Cardia GC is located in the proximal stomach at the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ), while non-cardia GC resides in the distal stomach. Various characteristics point to pathomechanisms that are specific for each location-type. Cardia GC is related to gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) and its prevalence is rising.1 In contrast, the prevalence of non-cardia GC has decreased due to a decline in Helicobacter pylori infections, the main risk factor.1 Histopathologically, GC is subdivided into Lauren’s diffuse- and intestinal-type.1 Different pathophysiological processes are also specific for each of these subtypes. While intestinal GC develops from a metaplasia-neoplasia sequence, diffuse GC shows no preneoplastic condition.1

In multifactorial diseases genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have led to the identification of risk variants. Accordingly, nine GC GWAS have been carried out in the East-Asian population (Appendix p 4). Four of them focused on non-cardia GC2, 3, 4, 5 and three also used cardia GC.6, 7, 8 Because the Lauren classification is not widely used in Asia, no information on histopathological types were available in most studies. Only two GWAS in the Japanese population used Lauren’s diffuse- and intestinal-type without information on tumour location.9,10 In total, 12 GC loci have been identified in the East-Asian GWAS (Appendix p 5). Only one GC GWAS has been carried out in Europeans. This study used an Icelandic sample comprising 400 cases along with 2100 patients’ relatives that were counted as cases (Appendix p 4). GC-associations were found on chromosome 11q22 and three East-Asian GC loci were replicated.11 However, no information on GC location- or Lauren-type was available in this study.

To assess the GC genetic susceptibility due to common germline variants we carried out the largest GWAS in the European population and the first GWAS where information on patients’ tumours according to location- and Lauren-type were available. We next used expression data from different gastric regions for a transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) and expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) study to identify GC risk genes at GWAS loci. Finally, we examined whether oesophago-gastric adenocarcinomas at the GOJ share genetic aetiology. In addition to our GWAS on cardia GC this involved a GWAS on oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC) and its precursor lesion Barrett’s oesophagus (BO).12

Methods

Study design and participants

The GC GWAS consisted of ten European case–control samples (Appendix p 6). All patients had a histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma and were recruited between 1990 and 2017 across 24 sites (Appendix p 7). The ethnically-matched controls were recruited between 1988 and 2017 across ten sites (Appendix p 8). For the TWAS/eQTL study we obtained genotype and transcriptome data from healthy European individuals that were recruited between 2016 and 2017 across nine sites (Appendix p 9). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and ethics approval was obtained from ethics boards at each participating institution (Appendix p 40).

Genome-wide genotyping, quality control and imputation

Except for cases from United Kingdom (UK) and Estonia, for which genotypes were drawn from the UK and Estonian Biobank,13,14 DNA-samples from all GWAS patients and TWAS/eQTL participants were genotyped within this study. For the control samples, genotypes were partly obtained from previous studies. All genotyping array types that were used are listed in the Appendix (p 10).

The pre-imputation quality control (QC) is described in the Appendix (p 3). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were then imputed for all GWAS samples ‒ with exception of the UK and Estonian datasets ‒ using the TOPMed Imputation Server and TOPMed Reference panel.15 For the TWAS/eQTL samples, SNPs were imputed using Impute216 and 1000 Genomes Phase 3 as reference.17

In the post-imputation QC we excluded variants with r2 less than 0.3 (GWAS) and an information score less than 0.8 (TWAS/eQTL), p-values for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) less than 1.0 × 10−6 in patients and less than 1.0 × 10−4 in non-patients, a minor allele frequency (MAF) less than 0.01 or a SNP-missing rate less than 0.05 for best-guessed genotypes at posterior probability of more than 0.9.

Gene-expression analysis

For the TWAS/eQTL analysis, tissue biopsies from five gastric regions (cardia, corpus, fundus, antrum and angulus) were collected from healthy individuals during routine gastroscopies. Pre-experiments revealed that the expression in corpus and antrum covers the transcriptome-variance in almost all gastric regions (Appendix p 20). Thus, both were subjected to 3′-mRNA Sequencing for the TWAS/eQTL analysis using the QuantSeq 3′-mRNA-Seq Library Prep Kit FWD for Illumina (Lexogen, Austria). Details on the QC, gene-alignment and expression-quantification are provided in the Appendix (p 3).

Statistical analysis

GWAS-association testing was performed considering an additive genetic model adjusting for five principal components (PCs) using PLINK2.18 After computing SNP-associations at single-sample level we performed a meta-analysis considering the fixed-effects inverse variance-weighting approach implemented in METAL.19 To test for independence of associated variants we applied a conditional analysis by a stepwise selection procedure implemented in GCTA-COJO.20

SNP-based GC heritability was calculated using LD score regression (LDSR).21 We also applied LDSR to determine the genetic correlation between GC and reported risk factors,1 for which GWAS data from Europeans were available.22 In total, we used four obesity-, two reflux-, five smoking-, five alcohol- and four education-/employment-related phenotypes that have been assessed by the UK Biobank.13 As significance threshold we applied a Bonferroni-correction considering the number of investigated traits (p = 0.05/20 = 2.5 × 10−3).

For the TWAS we created expression prediction models for all genes in the transcriptome with FUSION23 using local SNPs present in the HapMap3 and GC GWAS data (500 kb up- and downstream of the annotated gene start and stop.). For each expressed gene we correlated the predicted gene-expression with our GWAS data using linkage disequilibrium (LD) data from prediction models to identify significant expression disease-associations after Bonferroni-correction for the number of tested genes (pcorpus = 0.05/3269 = 1.5 × 10−5, pantrum = 0.05/4182 = 1.1 × 10−5).

For the eQTL analysis expression and genotype data were analysed using QTLtools24 according to parameters used by The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project.25 Briefly, sex, three genotype-based PCs and a set of PEER-factors derived from the normalized expression data were used for adjustment. A window of 1 Mb around the transcription start site (TSS) of each gene was defined for cis-eQTL detection. SNP-gene pairs were considered significant with a nominal p-value below a genome-wide empirical p-value threshold (pt) determined for each gene by extrapolation from a Beta distribution fitted to adaptive permutations. In contrast to the polygenic TWAS models, eQTL analyses evaluate the effect of single genetic marker on gene expression and are not followed up by testing for association in GWAS datasets.

To examine the genetic architecture of oesophago-gastric adenocarcinomas at the GOJ we computed polygenic risk scores (PRS) by considering as base in-house GWAS data from a European OAC/BO case–control sample that was part of a GWAS published previously12 and for which individual GWAS data were available (Appendix p 11). PRS were calculated after clumping (250 kb regions, clump-p = 1, clump-r2 = 0.1) by testing different p-value thresholds (from genome-wide significant (p = 5.0 × 10−8) to the full model (p = 1)) using PRSice tool.26 As for the GWAS, the analysis was performed independently in each sample considering the overall GC status. Logistic regression models between PRS and the phenotypic status were computed. The single-sample PRS regression-coefficients (beta and standard error) were then combined into a meta-analysis using the restricted maximum-likelihood (REML) estimator as implemented in the R package metaphor.

The PRS analysis revealed a shared polygenic risk architecture between cardia GC and OAC/BO. We, thus, performed a cross-trait GWAS meta-analysis using our cardia GC and the in-house OAC/BO samples. In addition, we used GWAS summary statistics from the other OAC/BO datasets that were published previously.12 All samples that were included are listed in the Appendix (p 11). The cross-trait GWAS meta-analysis was performed considering a fixed-effects inverse variance-weighting approach implemented in METAL.19

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all data and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

In total, information on 7,829,683 SNPs in 5815 patients and 10,999 controls from ten European GWAS were included in the GC meta-analysis. Furthermore, 1291 cardia and 3183 non-cardia GC patients were available for the location-specific as well as 1368 diffuse and 1696 intestinal GC patients for the Lauren-specific GWAS meta-analysis. All Q-Q and Manhattan plots from the GWAS are shown in the Appendix (pp 21–25). The genomic inflation factor lambda was 1.11, 1.07, 1.11, 1.06, and 1.07 for the entire, cardia, non-cardia, diffuse, and intestinal GC GWAS. The lambda values suggest the presence of moderate inflation which can be expected given the experimental design of a GWAS meta-analysis with this sample size including cohorts from different European populations and centres.

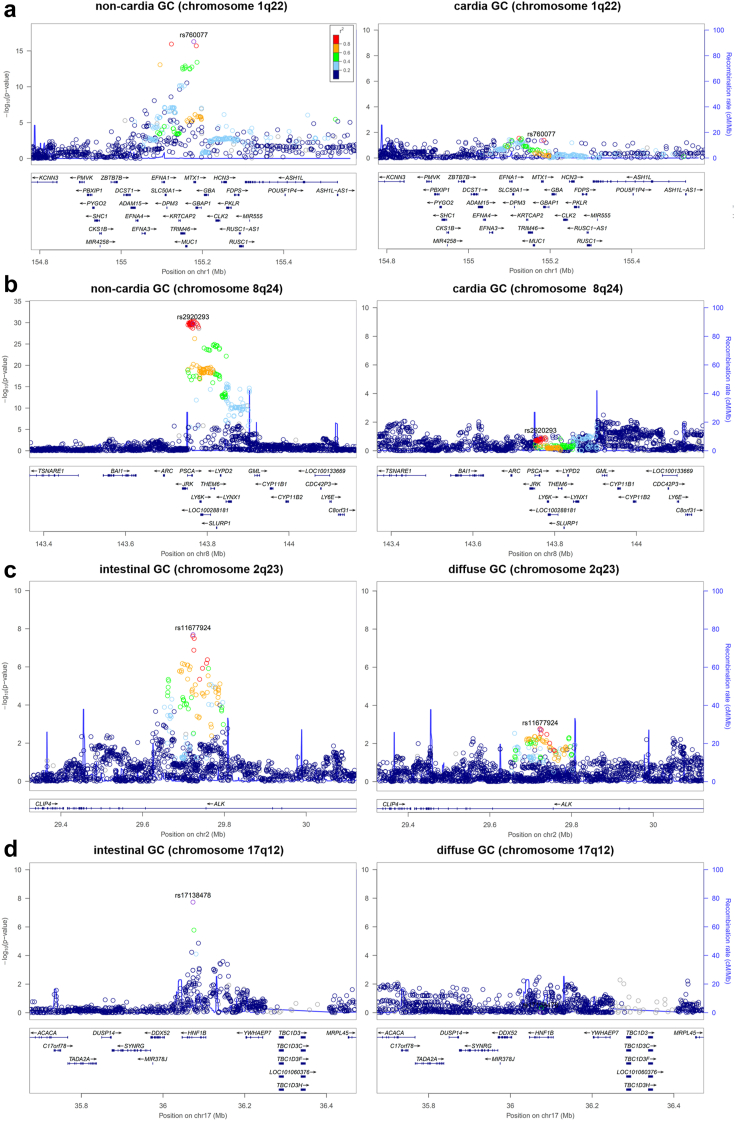

We identified four genome-wide significant GWAS loci, all with subtype-specific GC-association. Two of them ‒ on chromosome 1q22 and 8q24 ‒ have been reported previously,3, 4, 5,7,8,10,11 but not with respect to subtype-specificity. The other two ‒ on chromosome 2p23 and 17q12 ‒ have not been described before. Table 1 lists all associated loci and Fig. 1 shows the subtype-specificity. The consistency of all associations across samples is shown in the Appendix (p 26).

Table 1.

Lead associations of genome-wide significant and replicated GC risk loci.

| SNP | Chromosome (position in bp (hg38)) | Effect /other allelea | Entire GC sample |

Cardia GC sample |

Non-cardia GC sample |

Diffuse GC sample |

Intestinal GC sample |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | |||

| rs760077 | 1q22 (155,208,991) | T/A | 5.23E-21 | 1.27 | 1.21–1.34 | 4.45E-02 | 1.09 | 1.00–1.19 | 5.12E-17 | 1.31 | 1.23–1.40 | 7.41E-11 | 1.35 | 1.23–1.48 | 1.78E-07 | 1.24 | 1.14–1.35 |

| rs67579710b | 1q22 (155,203,736) | G/A | 5.89E-13 | 1.21 | 1.11–1.31 | – | – | – | 4.62E-12 | 1.27 | 1.15–1.42 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| rs11677924 | 2p23 (29,500,326) | G/C | 2.37E-07 | 1.19 | 1.11–1.27 | 5.91E-03 | 1.17 | 1.04–1.32 | 1.29E-05 | 1.20 | 1.10–1.30 | 1.90E-03 | 1.20 | 1.07–1.35 | 2.04E-08 | 1.34 | 1.21–1.49 |

| rs10029005 | 4q28 (124,530,209) | A/G | 4.69E-04 | 1.09 | 1.04–1.15 | 9.31E-01 | 1.00 | 0.91–1.09 | 4.37E-04 | 1.12 | 1.05–1.19 | 2.24E-02 | 1.11 | 1.01–1.21 | 7.72E-02 | 1.08 | 0.99–1.16 |

| rs6897169 | 5q13 (40,726,036) | C/T | 2.96E-04 | 1.13 | 1.06–1.21 | 2.65E-01 | 1.07 | 0.95–1.19 | 9.40E-05 | 1.18 | 1.09–1.28 | 4.20E-02 | 1.13 | 1.00–1.23 | 1.18E-02 | 1.15 | 1.03–1.27 |

| rs2920293c | 8q24 (142,683,996) | G/C | 2.84E-32 | 1.39 | 1.31–1.47 | 1.14E-01 | 1.08 | 0.98–1.19 | 1.80E-30 | 1.46 | 1.36–1.55 | 8.10E-17 | 1.46 | 1.33–1.60 | 4.05E-09 | 1.27 | 1.17–1.37 |

| rs532436c | 9q34 (133,274,414) | A/G | 7.51E-05 | 1.22 | 1.07–1.22 | 4.95E-01 | 1.04 | 0.93–1.17 | 5.82E-06 | 1.19 | 1.10–1.28 | 8.52E-07 | 1.29 | 1.17–1.44 | 3.02E-03 | 1.15 | 1.05–1.26 |

| rs17138478 | 17q12 (37,713,312) | C/A | 4.30E-06 | 1.19 | 1.10–1.28 | 3.96E-02 | 1.15 | 1.00–1.31 | 6.98E-04 | 1.17 | 1.07–1.29 | 8.83E-01 | 1.00 | 0.88–1.14 | 1.83E-08 | 1.44 | 1.27–1.64 |

The associations are shown for the risk alleles (effect alleles) in the entire GC sample as well as in the location- (cardia, non-cardia) and Lauren-specific (diffuse, intestinal) GC samples. p-values, odds ratios (ORs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are shown. Allele frequencies for the associated SNPs among patients and controls are not given, as the GWAS samples were meta-analysed. Instead the frequency of effect alleles in the European population are shown according to gnomAD.27 In addition, on chromosome 8q24 and 9q34 the LD between the lead GC SNPs in the present and East Asian GWAS is shown. At all replicated loci, the same associations contribute to GC risk across populations. All genome-wide significant associated GC loci also remain genome-wide significant associated after applying a genomic-control correction (genomic-control corrected p-values are shown in the Appendix (p 19)).

Frequency of effect alleles in the European (non-Finnish) population according to gnomAD.27 rs760077 allele T 59%, rs67579710 allele G 90%, rs11677924 allele G 15%, rs10029005 allele A 42%, rs6897169 allele C 17%, rs2920293 allele G 47%, rs532436 allele G 20%, rs17138478 allele C 86%.

rs67579710 was the only variant that showed additional association in the entire study after conditioning on lead SNPs using COJO.20 The independent association signal on chromosome 1q22 appeared in the entire and non-cardia GC sample and, thus, the associations are not shown for the other location- or Lauren-specific GC samples.

r2 of 0.88 between rs2920293 and rs2978977, the lead GC SNP on chromosome 8q24 in the East Asian population.8 rs532436 corresponds to the lead SNP rs7849280 in the East Asian population, where a high LD between both variants is present (r2 = 0.76).27 However, no LD between both variants is observed in the European population (r2 = 0.01).27

Fig. 1.

Regional association plots of GC risk loci. Disease associations are shown for non-cardia and cardia GC on chromosome 1q22 (a) and chromosome 8q24 (b). In addition, disease associations are shown for intestinal and diffuse GC on chromosome 2p23 (c) and chromosome 17q12 (d). At each locus, associations (−log10 (p values)) are shown for SNPs flanking 400 kb on either side of the lead associated SNP (Position in hg19). The lead variant is shown in purple. Other markers at each locus are displayed by different colours, which indicates different levels of LD (r2) to the lead SNP. Furthermore, all annotated genes within each region are shown with arrows indicating their transcription direction. The location- and Lauren-specific effects at each locus are also shown in a case-case comparison in the Appendix (p 12).

SNP rs760077 on chromosome 1q22 near MUC1 showed genome-wide significant GC-association (p = 5.23 × 10−21, odds ratio (OR) of 1.27 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.21–1.34)). The risk variant was strongest associated to non-cardia (p = 5.12 × 10−17, OR of 1.31 (95% CI 1.23–1.40)) and diffuse GC (p = 7.41 × 10−11, OR of 1.35 (95% CI 1.23–1.48)), while the association was nearly absent in cardia GC (p = 0.045) (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Moreover, conditioning on the lead SNP using COJO20 revealed an independent GC-association. SNP rs67579710 showed genome-wide significant association to entire (p = 5.89 × 10−13, OR of 1.21 (95% CI 1.11–1.31)) and non-cardia GC (p = 4.62 × 10−12, OR of 1.27 (95% CI 1.15–1.42)) (Table 1).

On chromosome 8q24 near PSCA we found the strongest GC-association for rs2920293 in the entire sample (p = 2.84 × 10−32, OR of 1.39 (95% CI 1.31–1.47)). Also this association was strongest to non-cardia (p = 1.80 × 10−30, OR of 1.46 (95% CI 1.36–1.55)) and diffuse GC (p = 8.10 × 10−17, OR 1.46 (95% CI 1.33–1.60)), while cardia GC showed no association (p = 0.114) (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

SNP rs11677924 on chromosome 2p23 within intron 4 of ALK showed suggestive association in the entire GC sample (p = 2.37 × 10−7, OR of 1.19 (95% CI 1.11–1.27)) and genome-wide significant association to intestinal GC (p = 2.04 × 10−8, OR of 1.34 (95% CI 1.21–1.49)) (Table 1). In contrast, this variant was only moderately associated to diffuse GC (p = 0.002) (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

The association to intestinal GC was even more pronounced for rs17138478 on chromosome 17q12 within intron 4 of HNF1B. This variant showed suggestive association in the entire GC sample (p = 4.30 × 10−6, OR of 1.19 (95% CI 1.10–1.28)) and genome-wide significant association to intestinal GC (p = 1.83 × 10−8, OR of 1.44 (95% CI 1.27–1.64)) (Table 1). In contrast, rs17138478 was not associated to diffuse GC (p = 0.883) (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

We next focused on all 10 remaining GC risk loci that have been reported previously (Appendix p 13).2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 We could replicate disease-associations at three loci. On chromosome 4q28, we observed the strongest association for rs10029005 near ANKRD50 in non-cardia GC patients (p = 4.37 × 10−4, OR of 1.12 (95% CI 1.05–1.19)) (Table 1). On chromosome 5q13, rs6897169 near PTGER4 was also strongest associated to non-cardia GC (p = 9.40 × 10−5, OR of 1.18 (95% CI 1.09–1.28)) (Table 1). Moreover, rs532436 on chromosome 9q34 within intron 1 of ABO encoding for the blood-group system was associated to non-cardia (p = 5.82 × 10−6, OR of 1.19 (95% CI 1.10–1.28)) and ‒ even stronger ‒ to diffuse GC (p = 8.52 × 10−7, OR of 1.29 (95% CI 1.17–1.44)) (Table 1). We, thus, inferred the ABO blood-groups using rs8176719 and rs8176746, which determine the ABO system (Appendix p 14). This revealed that blood-group 0 protects against non-cardia (p = 2.16 × 10−4, OR of 0.86 (95% CI 0.90–0.82)) and diffuse GC (p = 3.04 × 10−5, OR of 0.76 (95% CI 0.70–0.82)), while blood-group A increases risk for both GC subtypes (non-cardia GC: p = 9.27 × 10−10, OR of 1.28 (95% CI 1.32–1.24), diffuse GC: p = 8.01 × 10−6, OR of 1.31 (95% CI 1.37–1.25)) (Appendix p 14).

In pre-experiments for our TWAS/eQTL study we compared the expression profiles from five gastric regions, which showed that the expression in corpus and antrum covers the transcriptome-variance in almost all gastric regions (Appendix p 20). We, thus, selected the corpus and antrum mucosa from 362 and 342 individuals for transcriptome-wide profiling. This revealed specific expression profiles in both gastric regions (Appendix p 27), which were followed-up in our TWAS/eQTL study to prioritize GC risk genes.

On chromosome 1q22, we found significant TWAS-effects to non-cardia (p = 3.83 × 10−13) and diffuse GC (p = 2.40 × 10−10) with an upregulated MUC1-expression in corpus mucosa (Table 2 and Appendix (pp 28–31)). Conditioning on these findings revealed that the MUC1-expression explains most of the GWAS signals (Appendix pp 32–33). Although the upregulated MUC1-expression was also present in antrum mucosa, this TWAS-effect was considerably less significant (non-cardia GC: p = 5.26 × 10−6, diffuse GC: p = 1.01 × 10−5) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Transcriptome-wide significant GC-associations.

| Chromosomal region | Tissue | GC type | Gene | NWGT SNPs | TWAS Z score | TWAS p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1q22 | Corpus | non-cardia | MUC1 | 2 | 7.26 | 3.83E-13 |

| diffuse | MUC1 | 2 | 6.33 | 2.40E-10 | ||

| Antrum | non-cardia | MUC1 | 1 | 4.55 | 5.26E-06 | |

| diffuse | MUC1 | 1 | 4.41 | 1.01E-05 | ||

| 8q24 | Corpus | non-cardia | PSCA | 30 | 11.46 | 2.14E-30 |

| LY6K | 1 | 8.73 | 2.46E-18 | |||

| THEM6 | 1 | 9.31 | 1.23E-20 | |||

| LYNX1 | 26 | −7.23 | 4.85E-13 | |||

| diffuse | PSCA | 30 | 8.14 | 4.11E-16 | ||

| LY6K | 1 | 6.31 | 2.84E-10 | |||

| THEM6 | 1 | 6.34 | 2.28E-10 | |||

| LYNX1 | 26 | −4.65 | 3.35E-06 | |||

| intestinal | PSCA | 30 | 5.96 | 2.60E-09 | ||

| LY6K | 1 | 5.11 | 3.19E-07 | |||

| THEM6 | 1 | 5.24 | 1.62E-07 | |||

| Antrum | non-cardia | PSCA | 46 | 11.34 | 8.42E-30 | |

| LY6K | 26 | 6.75 | 1.46E-11 | |||

| THEM6 | 1 | 9.20 | 3.48E-20 | |||

| LYNX1 | 1 | −6.57 | 5.17E-11 | |||

| diffuse | PSCA | 46 | 8.04 | 8.84E-16 | ||

| LY6K | 26 | 5.90 | 3.69E-09 | |||

| THEM6 | 1 | 6.26 | 3.87E-10 | |||

| LYNX1 | 1 | −4.29 | 1.81E-05 | |||

| intestinal | PSCA | 46 | 5.81 | 6.32E-09 | ||

| THEM6 | 1 | 5.17 | 2.39E-07 |

In total, two risk loci (1q22, 8q24) and three GC types (non-cardia, diffuse, intestinal) as well as five genes were implicated. The number of weighted SNPs (NWGT SNPs, maximum of 50 variants) in the best predicting expression model is shown. In addition, TWAS Z scores indicating the effect of GC expression-association (downregulated/upregulated) and corresponding TWAS p-values are shown.

On chromosome 8q24, an upregulated expression of four genes ‒ PSCA, LY6K, THEM6 and LYNX1 ‒ showed significant GC-associations in the TWAS (Table 2 and Appendix (pp 28–31)). The upregulated PSCA-expression showed the most significant association (Table 2). Moreover, PSCA was the only gene whose expression explained most of the GWAS signals in all conditional analyses (Appendix pp 34–37). Thus, PSCA can be prioritized as the most relevant GC gene at this locus. The PSCA-association was strongest to non-cardia (corpus: p = 2.14 × 10−30, antrum: p = 8.42 × 10−30) and diffuse GC (corpus: p = 4.11 × 10−16, antrum: p = 8.84 × 10−16) (Table 2).

Individual eQTL-effects were comparatively smaller than TWAS-effects at most GWAS loci, highlighting the polygenic component of gene-expression. However, significant single-marker eQTLs at two replicated GC loci were found. On chromosome 4q28, risk allele-carrier at rs10029005 showed an upregulated ANKRD50-expression in corpus mucosa (p = 2.77 × 10−12) (Appendix p 38). On chromosome 5q13, an upregulated PTGER4-expression in corpus (p = 5.66 × 10−21) and to a lesser extent in antrum mucosa (p = 4.67 × 10−6) was present among risk allele-carrier at rs6897169 (Appendix p 38). Both eQTL-effects most probably did not reach significance in the TWAS because the significance of disease-association influences the TWAS outcome.

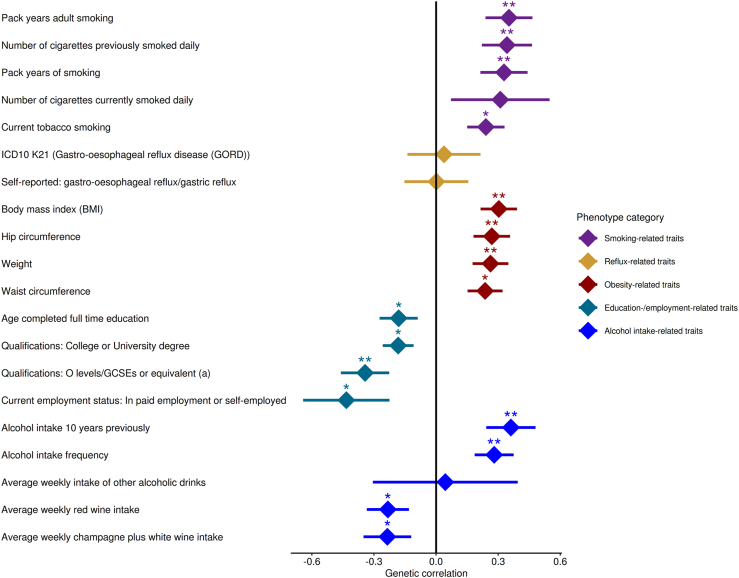

We next applied LDSR and estimated the SNP-based GC heritability to be 8.48 ± 3.12% standard deviation (SD). Unfortunately, we were not able to apply LDSR using GC subtypes due to the limited size of our location- and Lauren-specific samples. However, in the genetic correlation analysis using 20 traits belonging to five phenotype-categories representing GC risk factors, a significant genetic correlation with GC was found for three obesity-related traits, one smoking- and one alcohol-related trait (Fig. 2 and Appendix (p 15)).

Fig. 2.

Genetic correlation between GC and risk factors. Genetic correlations determined with LDSR between GC and 20 traits belonging to five phenotype-categories that represent risk factors for GC development are shown. For each trait the genetic correlation (dot) and the standard deviation (line) is given. The significance levels of the genetic correlation are indicated by asterisks (∗p value < 0.05, ∗∗p value < 0.0025). Body mass index (rg = 0.303, p = 6.0 × 10−4), hip circumference (rg = 0.269, p = 2.3 × 10−3) and weight (rg = 0.262, p = 2.4 × 10−3) showed Bonferroni-corrected positive GC correlation along with pack years of adult smoking (rg = 0.352, p = 2.0 × 10−3) and alcohol intake 10 years previously (rg = 0.361, p = 2.0 × 10−3).

Cardia GC and OAC are located in close proximity at the GOJ and belong to oesophago-gastric adenocarcinomas. Both cancer types share common characteristics, as they are related to GOR and their prevalence is rising.1 Thus, it remains controversial whether cardia GC and OAC rather represent one cancer entity.28

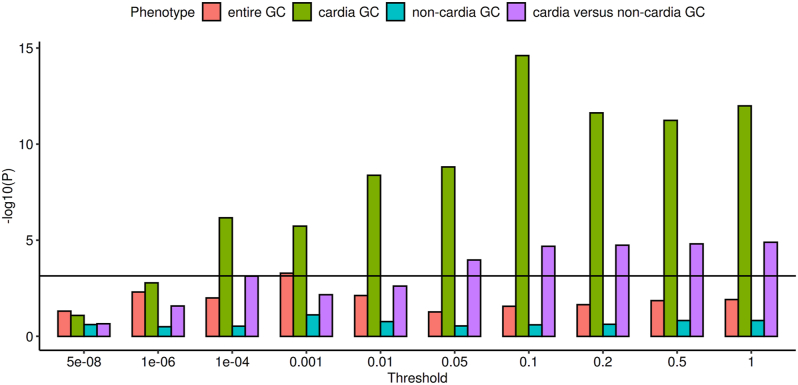

To examine the genetic relation between cardia GC and OAC we performed PRS analyses. We calculated PRS in two in-house discovery GWAS datasets with OAC as well as OAC and its precursor lesion BO.12 We then determined the proportion of variance explained by PRS from the discovery sets in four target datasets. We used the cardia GC GWAS as target set to examine the genetic relation to OAC and OAC/BO. In addition, we used the GWAS of the entire GC, non-cardia GC and cardia-versus-non-cardia GC as target sets to determine whether associations between cardia GC and OAC as well as OAC/BO are specific. In the Appendix (pp 16–17) all p-value thresholds, the number of SNPs included in each PRS and the observed associations are shown. We found highly significant associations between cardia GC and PRS derived from OAC (pthreshold = 0.001, passociation = 2.37 × 10−8) and OAC/BO (pthreshold = 0.2, passociation = 2.79 × 10−17) (Fig. 3). In contrast, no PRS-associations were present in the other GC case–control datasets (Fig. 3). Accordingly, in the case-case comparison (cardia-versus-non-cardia GC) we found significant associations to PRS derived from OAC (pthreshold = 0.5, passociation = 2.18 × 10−9) and OAC/BO (pthreshold = 0.2, passociation = 4.33 × 10−7) (Fig. 3). The results imply a shared genetic aetiology of cardia GC and OAC as well as OAC/BO, while OAC- and OAC/BO-PRS enable to discriminate between cardia and non-cardia GC.

Fig. 3.

Polygenic risk score associations for OAC in the target GC subtypes. The association-values in dependence of different significance thresholds for PRS variant selection are given. The horizontal black line represents the Bonferroni correction threshold. All PRS associations for OAC/BO in the target GC subtypes are shown in the Appendix (p 17).

Based on the shared polygenic risk of cardia GC and OAC/BO we performed a meta-analysis combining our GWAS datasets. This included 1291 cardia GC and 10,279 OAC/BO cases as well as 27,326 controls (Appendix 11). In total, we identified 17 genome-wide significant associated loci for oesophago-gastric adenocarcinoma that are ‒ along with the corresponding Manhattan plot ‒ shown in the Appendix (p 18 and p 39). Two of the identified loci have not been described before in the OAC/BO-only GWAS.12 SNP rs1817002 near HNF4G on chromosome 8q21 showed disease-association with p = 4.10 × 10−8 (OR of 1.11 (95% CI 1.06–1.14)) and rs234506 near NR2F2 on chromosome 15q26 showed disease-association with p = 1.56 × 10−9 (OR of 1.12 (95% CI 1.07–1.16)).

Discussion

The strength of this study is that the genetic heterogeneity of GC could be assessed, as patients’ tumours were characterised according to location and histopathology. This revealed that the known risk loci on chromosome 1q22 (MUC1), 4q28 (ANKRD50), 5p13 (PTGER4), 8q24 (PSCA), and 9q34 (ABO)3,4,7, 8, 9,11 contribute almost exclusively to non-cardia GC. Moreover, the risk loci on chromosome 1q22 (MUC1), 8q24 (PSCA), and 9q34 (ABO) confer substantially higher risk to diffuse than to intestinal GC. In contrast, the newly identified risk loci on chromosome 2p23 (ALK) and 17q12 (HNF1B) contribute almost exclusively to intestinal GC.

Our TWAS/eQTL study revealed that an upregulated expression of MUC1, ANKRD50, PTGER4, and PSCA are the most plausible GC-pathomechanism at four GWAS loci. These effects were strongest in corpus mucosa, except for PSCA that also showed considerable GC-association in antrum mucosa. Moreover, the upregulated MUC1- and PSCA-expression contributed strongest to diffuse GC.

While it has been shown previously that PSCA represents the most plausible risk gene at chromosome 8q24,29,30 the expression-effects of the remaining genes on GC-pathophysiology are novel. MUC1 exerts proto-oncogenic effects via a cytoplasmic domain (CD).31 This might explain why MUC1 particularly increases risk for diffuse GC. It has been shown, that overexpression of MUC1-CD disrupts E-cadherin functionality via increased binding of β-catenin.31 The E-cadherin/β-catenin complex plays an important role in maintaining epithelial integrity and mutations in CDH1—encoding E-cadherin—lead to hereditary diffuse GC (HDGC), the most common monogenic GC.1 So far, little is known about the function of ANKRD50. However, with regard to cancer ANKRD50 represents a hotspot for the genomic integration of human papillomaviruses in the context of cervical carcinoma development.32 PTGER4 encodes the prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) receptor 4, which mediates cellular responses to PGE2. It has been shown previously that PGE2 is important for the inflammatory microenvironment in tumours.33 Based on these findings, functional studies are now required to identify the GC-relevant disease mechanisms in detail.

Multiple studies, mainly from the 1950s and 1960s, reported an association between ABO blood-groups and gastrointestinal cancers, most strongly for gastric and pancreatic cancer.34,35 We confirm these findings on the genetic level and show that the protective effect of blood-group 0 and the risk effect of blood-group A is restricted to non-cardia and diffuse GC in Europeans. As with the risk genes mentioned above, functional studies are now required to show how ABO contributes to non-cardia and diffuse GC at the cellular level.

Although we could not functionally characterise the remaining GWAS loci, promising GC candidate genes are located in close proximity to the associated risk variants. The risk SNP on chromosome 2p23 is located in intron 4 of ALK, which encodes for a receptor tyrosine kinase that plays a role in cancer development. Germline mutations in ALK lead to monogenic neuroblastomas36 and somatic ALK mutations are key driver events in non-small cell lung cancers,37 but have also been observed in GC.38 On chromosome 17q12 the risk SNP is located in intron 4 of HNF1B, which encodes a transcription factor that plays a role in cancer development. Accordingly, SNPs in HNF1B have been repeatedly identified as risk factors in GWAS of prostate, endometrial, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer.39, 40, 41, 42 However, we could not functionally characterise both GWAS loci and, thus, it remains speculative that ALK and HNF1B represent the true susceptibility genes for GC at these loci.

This study is the first that analysed GWAS data for GC on the polygenic level. We estimated the SNP-based GC heritability to be 8.48 ± 3.12 SD, which already explains around 30% of the reported GC twin-based heritability of 28%.43 Furthermore, we found genetic correlations between GC and GC risk factors obesity, smoking and alcohol-intake on the polygenic level.

Most importantly, we found highly significant associations between cardia GC and PRS derived from OAC and OAC/BO. Moreover, OAC- and OAC/BO-PRS enabled to discriminate between cardia and non-cardia GC. The findings imply that cardia GC and OAC or oesophago-gastric adenocarcinomas at the GOJ share polygenic risk architecture, which points to common molecular mechanisms conferring to both cancer types.

Promising candidate genes are also in close vicinity to the newly identified risk SNPs for oesophago-gastric adenocarcinoma, namely HNF4G on chromosome 8q21 and NR2F2 on chromosome 15q26. NR2F2 is a known coregulator of HNF4G and both genes play a prominent role in intestinal-like cell transformations in gastric cell lineages.44

Our study has limitations. Because GWAS only allow the identification of common risk variants for multifactorial diseases, we could not identify rare risk variants in our patients. Thus, we are not able to completely capture the genetic risk architecture underlying GC. Future studies are warranted that cover the entire genetic variability leading to GC development. Furthermore, the size of our GWAS sample was not large enough to develop GC PRS that can be used for disease prediction. For other cancer types, this has already become possible due to the availability of larger GWAS samples.

In summary, this European GWAS shows that all known and new risk loci contribute subtype-specifically to GC. Our findings should further help to elucidate the pathomechanisms underlying each GC type. At four GWAS loci we identified that an upregulated MUC1-, ANKRD50-, PTGER4-, and PSCA-expression represent the most plausible GC-pathomechanisms. In addition, we show that blood-group 0 exerts protective effects against non-cardia and diffuse GC, while blood-group A increases risk for both GC subtypes. Finally, we identified that cardia GC and OAC share genetic aetiology and, thus, support that common molecular pathomechanisms confer risk to oesophago-gastric adenocarcinomas at the GOJ.

Contributors

CarM, JG, JohS, MarV, and TH designed the study, verified the underlying data, and wrote the manuscript. AndMa, CarM, EH, JG, JanS, MicK, OB, PK, TH, and VS performed statistical analysis and conducted experiments. AdrM, AgoS, AH, AndMe, AngL, APA, AJ, AnnL, AnnM, ABA, AntS, ArmS, AHH, CarP, CZ, ChiS, CJB, ClaP, ClaS, CT, DC, DA, DD, DP, ES, ER, EMP, FMT, FS, FG, FL, FT, FLD, GCT, GT, GK, GP, HA, HanL, HL, HenN, HB, IG, IB, JRI, JL, JFD, JT, JE, JOJ, JH, JK, JurS, JA, JD, KR, KM, KO, LV, LB, LH, MagN, MalL, ManK, MarL, MarMa, MR, MAGG, MPo, MPe, MarV, MDR, MTL, MarMo, MarN, MarK, MatL, MicGe, MS, MicGh, MonL, NF, NK, NV, NA, OK, OC, OG, OP, PE, PM, PPG, PL, RafC, RRS, RenC, RusT, RobPa, RobPe, RA, RM, SEAB, SA, SB, SLH, SusB, ThoS, TOG, TomS, VDR, VicMa, VicMO, VA, and YV contributed to sample collection, including handling of data. AQ, AMH, DH, HIG, JulS, JR, MMN, MicV, and PH reviewed data and provided critical comments or suggestions. JohS had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

Summary statistics of the GC GWAS are available on request from the corresponding author (Johannes.schumacher@uni-marburg.de).

Declaration of interests

MDR reports consulting fees from Roche Diagnostics and Medtronic; leadership or fiduciary role in the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and World Endoscopy Organization (WEO). All other authors report no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) (SCHU 1596/6–1, KN 378/3–1, LO 1147/1-1, and VE 917/1-1). Additional funding institutions that indirectly supported the study can be found in the Appendix (p 40). The authors thank all study participants, scientists and clinicians who contributed to this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104616.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Smyth E.C., Nilsson M., Grabsch H.I., van Grieken N.C., Lordick F. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2020;396(10251):635–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin G., Ma H., Wu C., et al. Genetic variants at 6p21.1 and 7p15.3 are associated with risk of multiple cancers in Han Chinese. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91(5):928–934. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi Y., Hu Z., Wu C., et al. A genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for non-cardia gastric cancer at 3q13.31 and 5p13.1. Nat Genet. 2011;43(12):1215–1218. doi: 10.1038/ng.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z., Dai J., Hu N., et al. Identification of new susceptibility loci for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma: pooled results from two Chinese genome-wide association studies. Gut. 2017;66(4):581–587. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan C., Zhu M., Ding Y., et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies and functional assays decipher susceptibility genes for gastric cancer in Chinese populations. Gut. 2020;69(4):641–651. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abnet C.C., Freedman N.D., Hu N., et al. A shared susceptibility locus in PLCE1 at 10q23 for gastric adenocarcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2010;42(9):764–767. doi: 10.1038/ng.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu N., Wang Z., Song X., et al. Genome-wide association study of gastric adenocarcinoma in Asia: a comparison of associations between cardia and non-cardia tumours. Gut. 2016;65(10):1611–1618. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishigaki K., Akiyama M., Kanai M., et al. Large-scale genome-wide association study in a Japanese population identifies novel susceptibility loci across different diseases. Nat Genet. 2020;52(7):669–679. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0640-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Study Group of Millennium Genome Project for Cancer. Sakamoto H., Yoshimura K., Saeki N., et al. Genetic variation in PSCA is associated with susceptibility to diffuse-type gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40(6):730–740. doi: 10.1038/ng.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanikawa C., Kamatani Y., Toyoshima O., et al. Genome-wide association study identifies gastric cancer susceptibility loci at 12q24.11-12 and 20q11.21. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(12):4015–4024. doi: 10.1111/cas.13815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helgason H., Rafnar T., Olafsdottir H.S., et al. Loss-of-function variants in ATM confer risk of gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2015;47(8):906–910. doi: 10.1038/ng.3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gharahkhani P., Fitzgerald R.C., Vaughan T.L., et al. Genome-wide association studies in oesophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett's oesophagus: a large-scale meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(10):1363–1373. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30240-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sudlow C., Gallacher J., Allen N., et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leitsalu L., Haller T., Esko T., et al. Cohort profile: Estonian biobank of the Estonian genome center, University of Tartu. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(4):1137–1147. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taliun D., Harris D.N., Kessler M.D., et al. Sequencing of 53,831 diverse genomes from the NHLBI TOPMed Program. Nature. 2021;590(7845):290–299. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03205-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howie B.N., Donnelly P., Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genomes Project C., Auton A., Brooks L.D., et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Purcell S., Neale B., Todd-Brown K., et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willer C.J., Li Y., Abecasis G.R. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(17):2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang J., Ferreira T., Morris A.P., et al. Conditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nat Genet. 2012;44(4):369–375. doi: 10.1038/ng.2213. S1-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bulik-Sullivan B., Finucane H.K., Anttila V., et al. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat Genet. 2015;47(11):1236–1241. doi: 10.1038/ng.3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng J., Erzurumluoglu A.M., Elsworth B.L., et al. LD Hub: a centralized database and web interface to perform LD score regression that maximizes the potential of summary level GWAS data for SNP heritability and genetic correlation analysis. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(2):272–279. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gusev A., Ko A., Shi H., et al. Integrative approaches for large-scale transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2016;48(3):245–252. doi: 10.1038/ng.3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fort A., Panousis N.I., Garieri M., et al. MBV: a method to solve sample mislabeling and detect technical bias in large combined genotype and sequencing assay datasets. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(12):1895–1897. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.GTEx Consortium. Laboratory, Data Analysis and Coordinating Center (LDACC)—Analysis Working Group. Statistical Methods groups—Analysis Working Group Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature. 2017;550(7675):204–213. doi: 10.1038/nature24277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi S.W., O'Reilly P.F. PRSice-2: polygenic Risk Score software for biobank-scale data. Gigascience. 2019;8(7) doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giz082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karczewski K.J., Francioli L.C., Tiao G., et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581(7809):434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayakawa Y., Sethi N., Sepulveda A.R., Bass A.J., Wang T.C. Oesophageal adenocarcinoma and gastric cancer: should we mind the gap? Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(5):305–318. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sung H., Hu N., Yang H.H., et al. Association of high-evidence gastric cancer susceptibility loci and somatic gene expression levels with survival. Carcinogenesis. 2017;38(11):1119–1128. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgx090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heinrichs S.K.M., Hess T., Becker J., et al. Evidence for PTGER4, PSCA, and MBOAT7 as risk genes for gastric cancer on the genome and transcriptome level. Cancer Med. 2018;7(10):5057–5065. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farahmand L., Merikhian P., Jalili N., Darvishi B., Majidzadeh A.K. Significant role of MUC1 in development of resistance to currently existing anti-cancer therapeutic agents. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2018;18(8):737–748. doi: 10.2174/1568009617666170623113520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang-Chun F., Sen-Yu W., Yuan Z., Yan-Chun H. Genome-wide profiling of human papillomavirus DNA integration into human genome and its influence on PD-L1 expression in Chinese Uygur cervical cancer women. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/6284960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Echizen K., Hirose O., Maeda Y., Oshima M. Inflammation in gastric cancer: interplay of the COX-2/prostaglandin E2 and Toll-like receptor/MyD88 pathways. Cancer Sci. 2016;107(4):391–397. doi: 10.1111/cas.12901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aird I., Bentall H.H., Roberts J.A. A relationship between cancer of stomach and the ABO blood groups. Br Med J. 1953;1(4814):799–801. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4814.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marcus D.M. The ABO and Lewis blood-group system. Immunochemistry, genetics and relation to human disease. N Engl J Med. 1969;280(18):994–1006. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196905012801806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosse Y.P., Laudenslager M., Longo L., et al. Identification of ALK as a major familial neuroblastoma predisposition gene. Nature. 2008;455(7215):930–935. doi: 10.1038/nature07261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soda M., Choi Y.L., Enomoto M., et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448(7153):561–566. doi: 10.1038/nature05945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wen Z., Xiong D., Zhang S., et al. Case report: RAB10-ALK: a novel ALK fusion in a patient with gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.645370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gudmundsson J., Sulem P., Steinthorsdottir V., et al. Two variants on chromosome 17 confer prostate cancer risk, and the one in TCF2 protects against type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39(8):977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klein A.P., Wolpin B.M., Risch H.A., et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies five new susceptibility loci for pancreatic cancer. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):556. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02942-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pharoah P.D., Tsai Y.Y., Ramus S.J., et al. GWAS meta-analysis and replication identifies three new susceptibility loci for ovarian cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):362–370. doi: 10.1038/ng.2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spurdle A.B., Thompson D.J., Ahmed S., et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a common variant associated with risk of endometrial cancer. Nat Genet. 2011;43(5):451–454. doi: 10.1038/ng.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lichtenstein P., Holm N.V., Verkasalo P.K., et al. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer--analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(2):78–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007133430201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sousa J.F., Nam K.T., Petersen C.P., et al. miR-30-HNF4gamma and miR-194-NR2F2 regulatory networks contribute to the upregulation of metaplasia markers in the stomach. Gut. 2016;65(6):914–924. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.