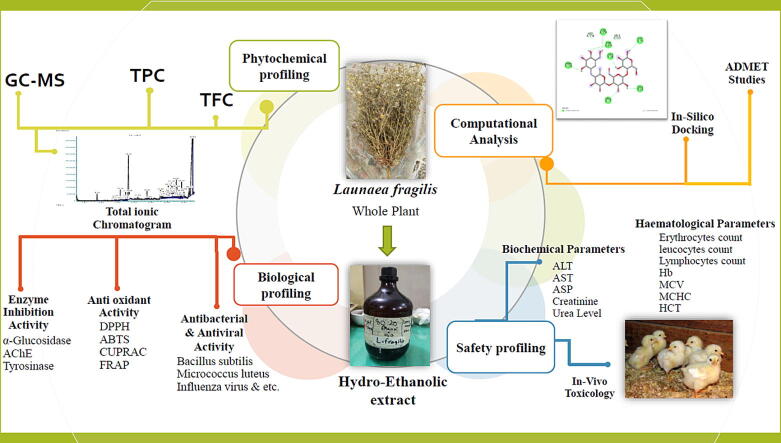

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Launaea fragilis, GC–MS analysis, Toxicity, Antioxidant, Enzyme inhibition, Computational analysis

Abstract

Launaea fragilis (Asso) Pau (Family: Asteraceae) is a wild medicinal plant that has been used in the folklore as a potential treatment for numerous ailments such as skin diseases, diarrhea, infected wounds, inflammation, child fever and hepatic pain. This study explored the chemical constitution, in-vivo toxicity, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and enzyme inhibition potential of ethanolic extract of L. fragilis (EELF). Additionally, in-silico docking studies of predominant compounds were performed against in-vitro tested enzymes. Similarly, in-silico ADMET properties of the compounds were performed to determine their pharmacokinetics, physicochemical properties, and toxicity profiles. The EELF was found rich in TFC (73.45 ± 0.25 mg QE/g) and TPC (109.02 ± 0.23 mg GAE/g). GC–MS profiling of EELF indicated the presence of a total of 47 compounds mainly fatty acids and essential oil. EELF showed no toxicity or growth retardation in chicks up to 300 mg/kg with no effect on the biochemistry and hematology of the chicks. EELF gave promising antioxidant activity through the CUPRAC method with an IC50 value of 13.14 ± 0.18 µg/ml. The highest inhibition activity against tyrosinase followed by acetylcholinesterase and α-Glucosidase was detected. Similarly, the antimicrobial study revealed the extract with good antibacterial and antiviral activity. A good docking score was observed in the in silico computational study of the predominant compounds. The findings revealed L. fragilis as a biocompatible, potent therapeutic alternative and suggest isolation and further in vivo pharmacological studies.

1. Introduction

Since the dawn of civilizations, humans and plants both have co-existed and this co-existence has helped humans in revolutionizing pharmaceutical and nutritional sciences as plants have represented the paradigm of remedies for centuries (Sadeer et al., 2019). Recently, the interest of researchers has increased exponentially to acknowledge the composition of plants and investigate their clinical applications. Moreover, utilizing the power of nature to overcome proliferating diseases like diabetes, skin aging, cancer, heart attack and alarming health conditions like COVID-19 (Coronavirus disease 2019) is the need of the hour (Bhalla et al., 2021). Numerous bioactive compounds have been identified and isolated from the plants serving not only as lead drugs but also as precursors in the development of new drug entities (Parveen et al., 2021). Bioactive secondary metabolites are considered a renewable source of drug leads that are non-toxic, environment friendly, and hold extensive uses in pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, perfume, and agricultural industries (Sharma et al., 2021). These metabolites are responsible for the anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-cancer, anti-diabetic, and numerous other therapeutic properties of the plant. Because of these characteristics about 20,000 different species of plants are used for treatment purposes (Aziz et al., 2022).

Due to the immense medicinal potential of plants, botanical drug investigation programs led by the government are initiated in some countries to discover phytopharmaceuticals (Ahn 2017). Nowadays medicinal chemists make use of virtual screening methods to search drug candidates, these methods are rational and direct with the advantage of being cost-effective and efficient. Scientists in pursuit of novel drugs often adopt the molecular docking method that helps in finding bioactive secondary metabolites from the pool. This method studies the theoretic affinity of a specific molecule with a specific biological target (Tripathi and Misra 2017). Virtual screening through molecular docking helps in determining the potential ability of natural products and developing novel herbal products as remedies for various clinical needs (Parveen et al., 2021).

Launaea fragilis (Asso) Pau is a medicinal xero-halophyte belonging to the Asteraceae family. The genus launaea Cass. is a polymorphic genus that comprises 54 species and 10 subspecies that are distributed throughout SW Asia, South Mediterranean, and Africa (El-Darier et al., 2021). Many of its plants have folklore uses to treat diarrhea, infected wounds, inflammation, bitter stomachic, skin diseases, child fever, and hepatic pain and are also used for their diuretic, insecticidal and soporific properties (Cheriti et al., 2012).

Considering the medicinal importance of the genus launaea Cass. and the ethnobotanical background of L. fragilis, the present study aimed to assess the comprehensive phytochemical make-up, safety or toxicity profile, biological potential, and in-silico computational aspects of ethanolic extract of L. fragilis (EELF) for the first time as there is scarcity of experimental records on this plant. Phytochemical profiling was done with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS) secondary metabolite analysis. To establish safety profile, an in-vivo chronic toxicity study was performed on the chicks. Plants can be applied for multi-targets in treating diseases at a single time. It is possible due to the fact of plant pharmacological and chemical diversity. Therefore, in this study, the biological potential of L. fragilis was assessed through various biological assays including in-vitro antioxidant, antiviral, antibacterial, and various clinically significant enzyme inhibition assays. Moreover, in-silico computational studies of the phytochemicals identified in the EELF were done to highlight the interactions, mechanisms of enzyme inhibition, and ADMET profiles.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant collection and preparation of extract

The naturally grown whole plant of L. fragilis was procured in November 2020 from Dingarh, Mojgarh, and Derawar fort areas in the Bahawalpur region, Pakistan. The plant was identified as L. fragilis by taxonomist Mr. Ghulam Sarwar, from the Department of Botany, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Punjab, Pakistan. The plant sample with the reference number (LS/IUB/163) was also submitted to the official herbarium of the University. The plant was shade dried, powdered (500 g) and the hydroethanolic extract of L. fragilis (EELF) was prepared through maceration in 80% ethanol: water 20% with intermittent shaking for 14 days at room temperature. The macerated plant was filtered and the extract was concentrated at 45 °C and reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator. The extract (53 g) prepared was stored at 2 to 8 °C for further use. The percent (%) yield was calculated on dry weight basis.

2.2. Phytochemical composition

2.2.1. Preliminary phytochemical screening

EELF was subjected to primary and secondary metabolites screening as described previously by (Velavan 2015) to identify the presence of carbohydrates, lipids, amino acids, proteins, alkaloids, glycosides, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, steroids, terpenes, and resins.

2.2.2. Estimation of total flavonoid content and total phenolic content

Previously established methods were utilized to determine TFC (total flavonoid content) and TPC (total phenolic content) respectively (Ahmed et al., 2022). The TFC was reported as mg Quercetin Equivalents (mg QE/g dry extract), whereas the TPC was reported as mg Gallic Acid Equivalents (mg GAE/g dry extract).

2.2.3. Gc–MS analysis

Chemical profiling of EELF was done using GC–MS analysis. Gas chromatogram (Agilent 6890 series) coupled with mass spectrometer detector (Agilent 5973 series) was used. The column used was ultra-inert capillary non-polar HP-5MS with a 30 m column length, 0.25 µm film thickness, and 25 mm internal diameter. Helium gas (99.995%) in the pure form was employed to carry the sample at a constant 1.02 mL/min flow. 1.0 µL of the hydro-ethanol extract diluted with a respective solvent (ethanol) was injected at 245 °C using split-less injection. Initially, the temperature was adjusted at 55–155 °C and then gradually elevated at 3 °C/min with a retention time of 10 min. In the end, 310 °C temperature at 10 °C/min was adjusted. Detected bioactive compounds were identified through a NIST library search (NIST 2011) (Hayat and Uzair 2019).

2.3. In-vivo toxicological evaluation of L. Fragilis

2.3.1. Animals management

Toxicological evaluation of different doses of EELF was conducted on a-day-old broiler chicks (n = 100) procured from Faisal Chicks (Pvt) Ltd, Multan using standard protocols. The study was approved by Pharmacy Animals Ethics Committee (PAEC) with reference number PAEC/21/132. The study was executed in November and December 2021 where these chicks were kept in a semi-open shed under standard conditions of temperature, humidity, feed, and management. Vaccinations of all the chicks were done as per schedule against Infectious Bursal disease (IBD), Hydropericardium (HPS), and Newcastle (ND). A starter diet having 18% crude protein and 2700 Kcal/kg metabolizable energy along with clean water was initiated ad libitum. All the chicks were randomly divided into five groups (G1-G5) after seven days of acclimatization and each group was separated from the other in a 3x3 feet pen covered with an iron mesh. Each group was treated with a different dose of EELF on daily basis for the next 21 days as provided in Table S1.

2.3.2. Toxicity variables investigated

The toxicity investigations of EELF were conducted through already established methods with slight modifications (Shahzad et al., 2012, Ghaffar et al., 2017, Saleem et al., 2019). All the experimental birds were examined three times a day for any irregularity and a record was maintained. Clinical signs, behavioral changes, stimuli response, physical appearance, and mortality were observed. Feed consumption along with water intake was also observed. On days 7, 14, and 21 after the commencement of dosing, blood samples were drawn from the chicks for serum biochemical and hematological examinations. On the same sampling days, five birds from each group were weighed to obtain live weight and then slaughtered to obtain carcass and different body organ weights.

2.3.3. Haematological and serum biochemical examination

A hematological examination was performed through an automated hematological analyzer and the parameters considered were leucocytes, lymphocytes, erythrocytes, hemoglobin, HCT, MCHC, and MCV count. For serum biochemical analysis, serum was separated by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 15 mins and stored at 8℃. AST, ALT, ALP, Urea, and serum creatinine were determined through commercially available kits.

2.3.4. Body weight and organs index

The chicks were slaughtered by cutting the jugular vein. Carcass weight along with visceral organ weights (absolute weight) and organ indexes (Organ weight/ Body weight) were calculated.

2.4. Antioxidant activity

Radical scavenging activity quantification (RSA) was done through ABTS (2,2-azinobis 3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) and DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl). The reducing capability of EELF was determined using FRAP (ferric-reducing antioxidant power) and CUPRAC (Cupric-reducing antioxidant capacity). Already established methods were used with slight modifications.

2.4.1. 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazy assay

Plant extract (2500 μL) and 2500 μL ethanolic extract of DPPH (0.004%) were mixed and then incubated in the dark at 25 °C and stirred for 20 min. For baseline correction, 90% aqueous ethanol was prepared as a negative control, and absorbance was taken at 517 nm. The outcomes were measured as IC50 value (Shahzad et al., 2022).

2.4.2. 2,2-azinobis(3-ethylbenothiazoline)-6-sulfonic acid assay

ABTS+ cation was produced by incubating potassium persulfate (2.5 mM) and ABTS mixture (7 mM) in the absence of light at room temperature. Plant extract (75 µL) was mixed with ABTS+ solution (150 µL) and the absorbance was taken at 734 nm after 30 mins (Grochowski et al., 2019). The results were measured as IC50 value.

2.4.3. Cupric reducing antioxidant capacity assay

Plant extract (75 µL) was mixed with [7.5 mM neocuprine (150 µL), 10 mM CuCl2 (150 µL), 1 M NH4Ac buffer (150 µL)] mixture, at 450 nm absorbance was taken after 30 mins (Grochowski et al., 2019). The results were measured as IC50 value.

2.4.4. Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay

Plant extract (75 µL) was added to the reagent (1500 µL) in 10 mM TPTZ (2,4,6-tris(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine) in Hydrochloric acid (40 mM), 20 mM ferric chloride and acetate buffer (0.3 M) in a final 10:1:1 ratio. At 593 nm absorbance was noted after 30 min (Khursheed et al., 2022). The results were measured as IC50 value.

2.5. Enzyme inhibition assays

The inhibition potential of EELF was tested against α-glucosidase, tyrosinase, and acetylcholinesterase. Eserine, kojic acid and agarose were used as standards for acetylcholinesterase, tyrosinase, and α-glucosidase respectively.

2.5.1. α-glucosidase

α-glucosidase inhibitory potential of EELF was determined using an already established method (Palanisamy et al., 2011) with minute changes. The test was performed using a 96-well microplate, with agarose as standard and P-NPG (P-nitrophenyl-D-glucopyranoside) as a substrate. α-glucosidase (0.4 U/mL) was dissolved in a phosphate buffer solution having pH 6.8 and BSA(0.2%) added to it. The sample was prepared by mixing plant extract (40 μL), P-NPG (40 μL), and α-Glucosidase solution (40 μL) in phosphate buffer (pH6.8) in 96 well microplate and incubating at 37 °C for 20 min. At 400 nm, absorbance was observed and the IC50 value was determined.

2.5.2. Acetylcholinesterase

The spectrophotometric procedure developed by (Ellman et al., 1961) was employed to analyze the acetylcholinesterase inhibitory potential as formerly described by (Aktumsek et al., 2013) with minute changes. The test was performed using a 96-well microplate, Eserine as a positive control and acetylthiocholine iodide as a substrate. Fifty μL sample extract (2 mg/ml), 125 μL 0.3 mM 5,5′-Dithio-bis(2-nitro- benzoic) acid in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8) and 20 μL of acetylthiocholine iodide (1.5 mM) were taken in 96 well microplate. Absorbance at 405 nm was taken after every 45 s. Thereafter, 25 μL acetylcholinesterase was mixed with it. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm after 15 mins and the IC50 value was calculated.

2.5.3. Tyrosinase

The Dopachrome method established by (Ghalloo et al., 2022) with some changes was used. The test was performed using a 96-well microplate, Kojic acid as standard and L- DOPA as a substrate. The sample was prepared by mixing 25 μL plant extract, phosphate buffer (100 μL), and tyrosinase solution (40 μL) in 96 well microplate. Thereafter, 40 μL L-DOPA was mixed with it. At 492 nm, the absorbance was observed after 15 mins of incubation at 37 °C and IC50 was calculated.

2.6. Anti-bacterial potential of L. fragilis

2.6.1. Tested strains

In-vitro Antibacterial potential of EELF was examined against gram-positive strains including Micrococcus luteus (ATCC 4925), Bacillus pumilus (ATCC 13835), Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 1692), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538), Staphylococcus epidermidis (ATCC 8724) and gram-negative strains including Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 9027). Drug Testing Laboratory Punjab, Pakistan provided these strains. The Standard drug used was a combination of Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid.

2.6.2. Agar well diffusion method

Already established protocols as described by were used (Shahid et al., 2023). Bacterial cultures were prepared by streaking on Mueller Hinton agar plates and incubating at 37℃ for 24 h. After a day, a few colonies of each bacteria were added to sterile nutrient broth in a test tube and incubated at 37℃ overnight. In the end, dilutions of 108 CFU/mL cell density were prepared for each bacterial colony. Sample solutions of EELF were prepared at concentrations of 50,100 and 150 mg/mL by dissolving the extract in 10% DMSO (Dimethyl sulfoxide) solution. The bacterial inoculum (0.1 mL) was spread evenly throughout the surface of Mueller Hinton agar (30 mL) in a petri dish. Four wells having 5 mm diameter were punched into the plates and a sample solution (80 µL) was added to each well. The Petri dishes were incubated for 24 h at 37℃ and the results were computed as Zone of Inhibition expressed in millimeters.

2.7. Antiviral activity of L. fragilis

The anti-viral potential of EELF was assessed according to protocols established by (Dilshad et al., 2022) with slight modifications. Three strains include Newcastle disease virus (NDV, Lasoota strain), Avian infectious Bronchitis Virus (IBV, H120 strain), and Influenza Virus (H9, H9N2 strain).

2.7.1. Viral inoculation in chicken eggs

Chicken eggs possess numerous advantages as it is readily available, easy to handle, cheap, and require little storage space hence, are used for preliminary viral growth. Chorioallantoic membrane fluid provides optimum conditions for viral replication. Specific pathogen-free 8–12 days old chicken embryonated eggs were inoculated with above mentioned viral strains. Before inoculation, eggs were sterilized with a spirit swab, and with the help of a 3 cc syringe, a hole was made and viral strains were injected into embryonated eggs. After inoculation, melted wax was used to seal holes and inoculated eggs were incubated for 72 h at 37℃. Allantoic fluids were harvested (after 72 h) with the help of a syringe and subjected to Hemagglutination Test (HA) to compute the titer of each virus using a 96-well microtiter round bottom plate.

2.7.2. Hemagglutination (HA) assay

Hemagglutination (HA) assay was performed by collecting 5 mL of chicken blood using Alsever’s solution. Blood was centrifuged at 4500 RPMs for 4–5 mins and the supernatant was disposed of. The process was repeated thrice for better purification and results. RBC solution (1%) was prepared by mixing 20 µL packed RBCs with phosphate buffer saline solution (2 mL) and shaken gently in Eppendorf tubes to avoid precipitation. PBS (40 µL) was poured into each microtiter plate well and samples (40 µL) were added to the first well, mixed thoroughly, and 40 µL of this solution was transferred to 2nd well, and the process repeated up to the 11th well while 12th well only contained PBS (negative control). RBC solution (40 µL) was mixed in each well, incubated for an hour at 37℃, and Hemagglutination activity was observed.

2.8. Molecular docking studies

Different tools like PyRx, Babel, auto dock vina software, Discovery studio, and MGL Tools were used to carry out molecular docking studies. PubChem database was used to download the structures (3D) of the ligand molecules in SDF and were optimized using Babel. The optimized ligand molecules were docked with three enzymes namely acetylcholinesterase, α-glucosidase, and tyrosinase. The co-crystal structures of α-glucosidase with a code 5ZCB (Auiewiriyanukul et al., 2018), acetylcholinesterase with a code 1GQR (Bar-On et al., 2002), and tyrosinase with a code 3NM8 (Sendovski et al., 2011) were downloaded from protein data bank (PDB). Before docking enzymes were prepared using Discovery Studio 2021 Client and all co-crystallized molecules, water molecules, and inhibitors were removed. Docking was performed by uploading prepared enzymes and ligands to vina, embedded in PyRx. The outcomes were expressed as binding energies and the docked ligands along with their intermolecular interactions with the active sites were visualized using Discovery Studio 2021 Client (Nisar et al., 2022).

2.9. Evaluation of ADMET properties

On 7st january 2023, SwissADME (https://www.swissadme.ch/), was used to determine ADME attributes of bioactive compounds (Daina et al., 2017) and PROTOX II (https://tox-new.charite.de/protox_II/) was used to determine the toxicity profiles of the bioactive compounds.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Each evaluation was performed thrice to calculate their mean. The outcomes were presented as mean ± SD. SPSS (v22.0) software was operated for analyzing data, one-way analysis of variance and then post hoc Tukey’s test were performed. p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

3. Results

3.1. Extraction and preliminary phytochemical screening

The powdered material of L. fragilis soaked in hydroethanolic solvent system (Ethanol 80: 20 Distilled water) yielded an extract of 53 g. The percent yielded was calculated on dry weight basis which was 10.6 %. EELF was qualitatively screened for the primary and secondary phytoconstituents. The results of the preliminary phytochemical profiling of EELF are summarized in Table S2.

3.2. Total bioactive content

In the current study, EELF was tested for total bioactive content (TPC and TFC). The results are expressed in Table 1. which showed that EELF had 73.45 ± 0.25 mg QE/g TFC and 109.02 ± 0.23 mg GAE/g TPC.

Table 1.

Total polyphenolic content and antioxidant potential of ethanol extract of L. fragilis (EELF).

| Extract | Total bioactive Content | Antioxidant activity IC50 µg/mL |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFC (mg QE/g) |

TPC (mg GAE/g) |

DPPH |

ABTS |

CUPRAC |

FRAP |

|

| EELF | 73.45 ± 0.25 | 109.02 ± 0.23 | 39.27 ± 0.90 | 26.87 ± 1.21 | 13.14 ± 0.18 | 18.06 ± 0.34 |

All the data was represented as mean ± STD, (n = 3).

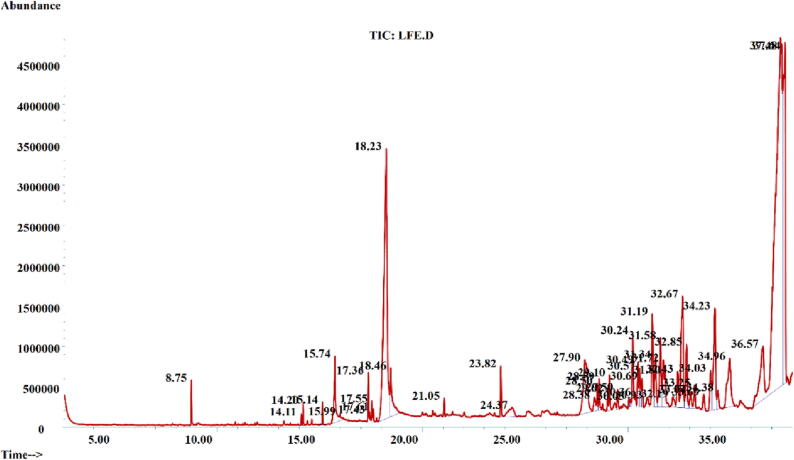

3.3. Gc–MS analysis

GC–MS analysis of EELF was done and the results are shown in Table 2. The chromatogram showed 47 peaks (Fig. 1). These compounds were tentatively identified through the NIST library. Major classes of compounds were steroids, fatty acids, esters, and vitamins. β-Amyrin (34.25%) (46), Alpha-Linoleic acid (13.13%) (11), β-Gurjunene (11.77%) (10), Bicyclogermacrene (3.69%) (36), β-Sitosterol (3.43%) (45), Friedelan-3-one (3.40%) (16), 1-ethenyl-1-methyl-4-methylene-2-(2-methyl-1-propenyl)-Cycloheptane (3.01%) (42), Ursa-9-(11),12-dien-3-ol (2.52%) (44), 2,2,6-Trimethylcyclohexanone (1.81%) (29), Ergosta-4,6,22-trien-3-beta-ol (1.68%) (31), 9,17-Octadecadienal, (Z)- (1.57%) (12) and Myristic acid (1.51%) (5) were among the major identified compounds.

Table 2.

Compounds identified in GC–MS analysis EELF.

| Peak No. | Retention time (min) | Tentative compound identification | Molecular Formula | Molecular Weight | Chemical class | Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.75 | Gamma-nonalactone | C9H16O2 | 156.2221 | Esters | 0.36 |

| 2 | 14.11 | Cis-pinane | C10H18 | 138.25 | Hydrocarbons | 0.12 |

| 3 | 14.19 | Hexahydrofarnesyl acetone | C18H36O | 268.5 | Terpenoids | 0.16 |

| 4 | 15.14 | Methyl palmitate | C17H34O2 | 270.5 | Esters | 0.20 |

| 5 | 15.74 | Myristic acid | C14H28O2 | 228.37 | Fatty acids | 1.51 |

| 6 | 15.99 | Ethyl palmitate | C18H36O2 | 284.5 | Fatty acids | 0.18 |

| 8 | 17.43 | Methyl oleate | C19H36O2 | 296.487 | Esters | 0.11 |

| 9 | 17.55 | gamma-Palmitolactone | C16H30O2 | 254.41 | Esters | 0.21 |

| 10 | 17.61 | 1,4-Eicosadiene | C20H38 | 278.5 | Hydrocarbons | 0.14 |

| 11 | 18.23 | Alpha-Linoleic acid | C18H32O2 | 280.4 | Fatty acids | 13.33 |

| 12 | 18.46 | 9,17-Octadecadienal, (Z)- | C18H32O | 264.4 | Fatty acid | 1.77 |

| 13 | 21.05 | 4,8,12,16-Tetramethylheptadecan-4-olide | C21H40O2 | 324.5 | Esters | 0.21 |

| 14 | 23.82 | Phthalic acid | C8H6O4 | 166.13 | Carboxylic acids | 0.58 |

| 15 | 24.37 | 2′,4′-Dihydroxy-4-methoxychalcone | C16H14O4 | 270.28 | ketones | 0.76 |

| 16 | 27.90 | Friedelan-3-one | C30H50O | 426.7 | Terpenoid | 3.50 |

| 17 | 28.37 | 1-Pyrrolidinebutanoic acid | C8H15NO2 | 157.21 | Carboxylic acid | 0.34 |

| 18 | 28.50 | A-Neooleana-3(5),12-diene | C30H48 | 408.7 | Hydrocarbons | 0.38 |

| 19 | 28.60 | 2-(7-Hydroxymethyl-3,11-dimethyl-dodeca-2.6,10-trienyl)-[1,4]-benzoquinone | C21H28O3 | 328.4 | Benzene derivatives | 0.44 |

| 20 | 29.10 | Oxoglaucine | C20H17NO5 | 351.4 | Alkaloid | 0.49 |

| 21 | 29.50 | β-Sitosterol acetate | C31H52O2 | 456.7 | Esters | 0.31 |

| 22 | 30.05 | Histidine, N-TFA-4-trifluoromethyl-, methyl ester | C10H9F6N3O3 | 333.19 | Esters | 0.11 |

| 23 | 30.24 | Carvestrene | C10H16 | 136.23 | Hydrocarbons | 1.38 |

| 24 | 30.36 | 4-Methoxybenzyl azidoformate | C9H9N3O3 | 207.19 | Esters | 0.21 |

| 25 | 30.49 | 3,5,6,7,8,8a-hexahydro-4,8a-dimethyl-6-(1-methylethenyl)-2(1H)-Naphthalenone | C15H22O | 218.33 | Ketones | 0.73 |

| 26 | 30.57 | Cedran-diol, (8S,14)- | C15H26O2 | 238.3657 | Cyclic Diol | 0.78 |

| 27 | 30.69 | Aristol-9-en-8-one | C15H22O | 218.33 | Ketones | 0.55 |

| 28 | 30.93 | Olean-12-ene | C30H50 | 410.7 | Hydrocarbons | 0.32 |

| 29 | 31.19 | 2,2,6-Trimethylcyclohexanone | C9H16O | 140.22 | Ketones | 1.81 |

| 30 | 31.33 | Ethyl stearate | C20H40O2 | 312.5304 | Esters | 1.22 |

| 31 | 31.58 | Ergosta-4,6,22-trien-3-beta-ol | C28H44O | 396.6 | Sterols | 1.68 |

| 32 | 31.73 | a-Neooleana-3,12-diene | C30H48 | 408.7 | Hydrocarbons | 1.13 |

| 33 | 31.80 | Pseudotaraxasterol | C30H50O | 426.7 | Terpenoids | 0.87 |

| 34 | 32.18 | 7alpha-Ethyl-8beta-hydroxy-2,6-dimethylbicyclo[4.4.0]dec-1-ene | C14H24O | 208.34 | Ketones | 0.36 |

| 35 | 32.42 | Benzo[b]naphtho[2,3-d]furan | C16H10O | 218.25 | Benzene derivatives | 0.85 |

| 36 | 32.66 | Bicyclogermacrene | C30H50O | 426.7 | Terpenes | 3.69 |

| 37 | 32.85 | 9,19-Cycloergost-24(28)-en-3-ol | C32H52O2 | 468.75 | Cholesterol derivative | 1.47 |

| 38 | 33.04 | Hop-22(29)-en-3beta-ol | C30H50O | 426.7 | Terpenoid | 0.41 |

| 39 | 33.25 | Cinchoninic Acid | C10H7NO2 | 173.17 | Carboxylic acids | 0.48 |

| 40 | 33.69 | 4-Amino-5-imidazolecarboxamide | C4H6N4O | 126.12 | Imidazoles | 0.34 |

| 41 | 34.03 | β-Caryophyllene | C15H24 | 204.35 | Terpenoids | 1.08 |

| 42 | 34.23 | 1-ethenyl-1-methyl-4-methylene-2-(2-methyl-1-propenyl)-Cycloheptane | C15H24 | 204.35 | Hydrocarbons | 3.01 |

| 43 | 34.39 | 3-Hydroxy-3-Methyl-2-Butanone | C5H10O2 | 102.13 | ketones | 0.45 |

| 44 | 34.96 | Ursa-9(11),12-dien-3-ol | C30H48O | 424.7 | Cholesterol derivative | 2.52 |

| 45 | 36.57 | β-Sitosterol | C29H50O | 414.7 | Sterols | 3.43 |

| 46 | 37.48 | β-Amyrin | C30H50O | 426.7 | Terpenoids | 34.25 |

| 47 | 37.64 | β-Gurjunene | C15H24 | 204.3511 | Ketones | 11.77 |

Fig. 1.

GC–MS chromatogram of ethanolic extract of L. fragilis (EELF).

Overall, the compounds obtained were from different Chemical classes and showed different percent areas as shown in Table 2. In detail the terpenoids showed highest percent area (40.97 %), followed by fatty acids (16.79 %), ketones (16.43%), hydrocarbon (6.48%), sterols (5.11 %), cholesterol derivatives (3.99 %), terpenes (3.69 %), esters (2.94 %), Benzene and its derivatives (1.29 %), carboxylic acids (1.4 %), cyclic diols (0.78%), alkaloids (0.49%), and imidazole (0.34%). The diversity in chemical classes might be the reason of pharmacological potential of the species.

3.4. In-vivo toxicological evaluation of EELF

The safety profile of EELF was established through an in-vivo toxicity study on chicks divided into five groups. Different parameters such as hematological, biochemical, and physical responses were assessed during the study with a sampling interval of 7 days. The chicks showed no behavioral alteration or clinical signs on receiving treatment. The outcomes are notified in Table S3. The chicks of each group showed no depression, dullness, tremors, gasping, alteration in feed or water intake, weight loss, or morphological changes. During the experiment period (21 days) of continuous treatment, no deaths or toxicity symptoms were observed. The effects of EELF on the chick’s hematopoietic system and biochemical parameters after oral administration were examined and results are summarized in Table S4 and S5. Haematological (hemoglobin, erythrocytes, MCHC, leucocytes, lymphocytes, and HCT) and biochemical (ALT, AST, Serum urea, ALP, and creatinine) parameters of the control and all the experimental groups showed no significant difference in the values. Effect of EELF after oral administration was also observed on the live weight, carcass weight, and organs indexes. The results are tabulated in Table S6. No significant difference in weights and injuries to any organs were observed even at higher doses.

3.5. Antioxidant activity

In this study, EELF was tested for its antioxidant potential through four different assays Table 1. The extract had an IC50 value of 39.27 ± 0.90 and 26.87 ± 1.21 µg/mL for DPPH and ABTS, respectively. Whereas, the IC50 values of 13.14 ± 0.18 and 18.06 ± 0.34 µg/mL for CUPRAC and FRAP, respectively.

3.6. Enzyme inhibition potential

The EELF presented significant enzyme inhibition and outcomes are tabulated in Table 3. For α-glucosidase, EELF showed an IC50 value of 36.53 ± 0.05 µg/mL in comparison to agarose (standard) 5.87 ± 0.01 µg/mL. For acetylcholinesterase, EELF showed an IC50 value of 33.28 ± 0.08 µg/mL in comparison to Eserine (standard) 1.87 ± 0.01 µg/mL. EELF showed an IC50 value of 27.85 ± 0.04 µg/mL against tyrosinase, while the standard Kojic acid showed an IC50 value of 2.87 ± 0.01 µg/mL.

Table 3.

Enzyme inhibition assays of ethanol extract of L. fragilis (EELF).

| Assays | Sample | (IC50 µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes inhibition assay | ||

| α-glucosidase | EELF agarose |

36.53 ± 0.05 5.87 ± 0.01 |

| Acetylcholinesterase | EELF Eserine |

33.28 ± 0.08 1.87 ± 0.01 |

| Tyrosinase | EELF Kojic Acid |

27.85 ± 0.04 2.87 ± 0.01 |

All the data was represented as mean ± STD, (n = 3).

3.7. Antibacterial activity of EELF

The antibacterial potential of L. fragilis was screened against two gram-negative and five gram-positive strains. Results are shown in Table 4. as the zones of inhibition which suggests dose-dependent inhibition of bacterial growth by the EELF. The extract showed a maximum zone of inhibition of 23 mm at 150 g/ml against micrococcus luteus and was active against other strains as well.

Table 4.

Antiviral and Antibacterial activity of EELF.

|

Zones of Inhibition (mm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains |

Amoxicillin + Clavulanic acid (mg/ml) |

Concentration of EELF (mg/ml) |

||

| 1 | 50 | 100 | 150 | |

| Bacillus subtilis | 20 mm | 17 mm | 20 mm | 20 mm |

| Bacillus pumilus | 21 mm | 18 mm | 18 mm | 20 mm |

| Escherichia coli | 26 mm | 10 mm | 12 mm | 15 mm |

| Micrococcus luteus | 24 mm | 18 mm | 18 mm | 23 mm |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | – | 11 mm | 14 mm | 14 mm |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 17 mm | 20 mm | 22 mm | 22 mm |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | – | 16 mm | 18 mm | 18 mm |

| Titer Count | ||||

| Viral Strains | Acyclovir | EELF | control | |

| H9 | 00 | 00 | 1024 | |

| NDV | 00 | 00 | 1024 | |

| IBV | 00 | 00 | 1024 | |

“-“ Not observed; NDV = Newcastle disease virus; H9 = Influenza virus; IBV = Avian infectious bronchitis virus; HA titer count 0 to 8 = very strong; 16 to 32 = strong; 64 to 128 = moderate; 256 to 2048 = Inactive (Aati et al., 2022).

3.8. Antiviral potential of EELF

A hemagglutination test was employed to test the anti-viral capabilities of L. fragilis against H9, NDV, and IBV strains. The results are expressed as Titer count as shown in Table 4. EELF showed very strong antiviral activity similar to Acyclovir (standard) against all the tested strains as their titer count was 00.

3.9. In-silico studies/molecular docking

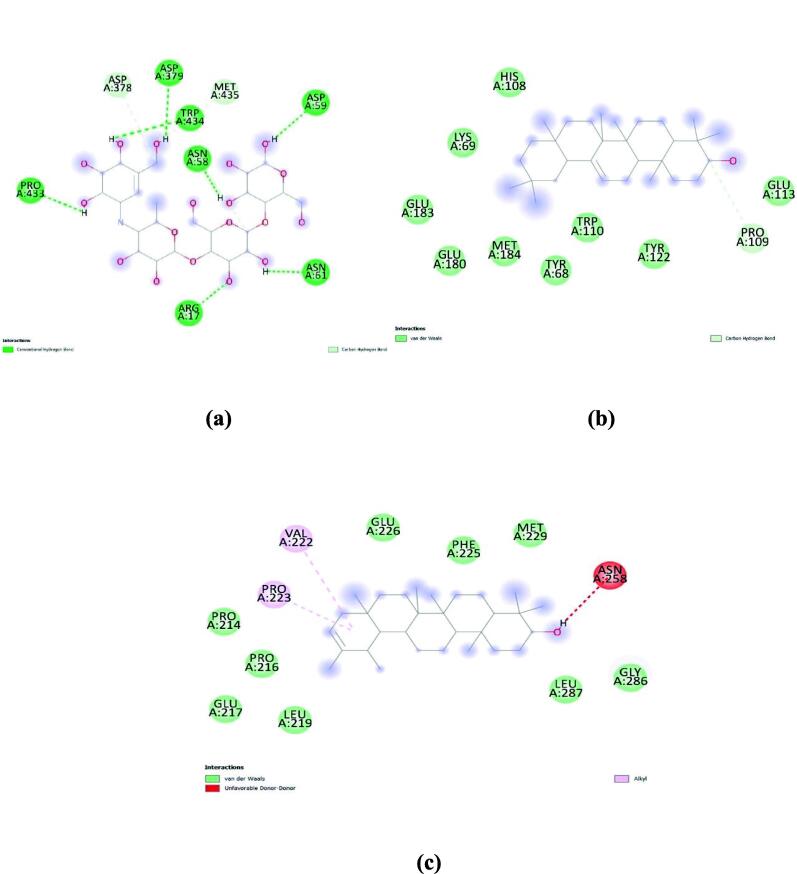

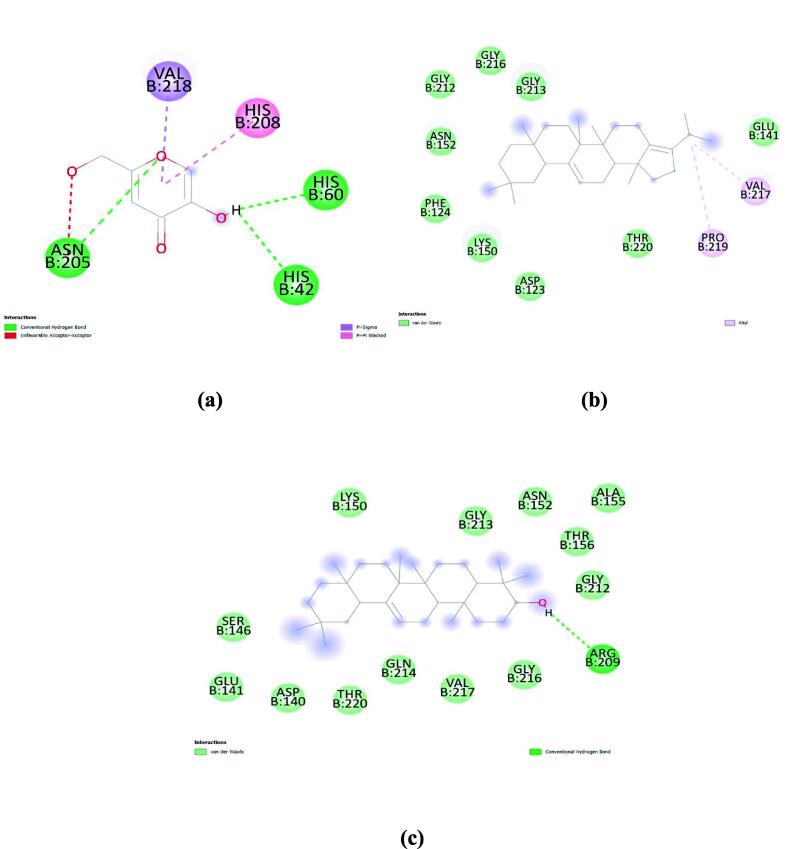

To highlight vital molecules and possible underlying mechanisms/interactions involved in the enzyme’s inhibition, docking studies were performed with the secondary metabolites tentatively identified in the EELF through GC–MS. Docking of control ligands was done to detect the active site of enzymes. All the tentative compounds were docked with each enzyme and compounds with the least binding energies (kcal/mol) are tabulated along with their interaction site. The results obtained after docking are represented in Table S7.

In the case of α-glucosidase, agarose (standard) had a binding energy of −6.8 kcal/mol. whereas, β-Amyrin and Pseudotaraxasterol showed −8.4 kcal/mol, and Friedelan-3-one showed −7.9 kcal/mol. Molecular interactions of these compounds with α-glucosidase are represented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Molecular interaction of (a) agarose (standard); (b) β-Amyrin; and (c) Pseudotaraxasterol with α-glucosidase.

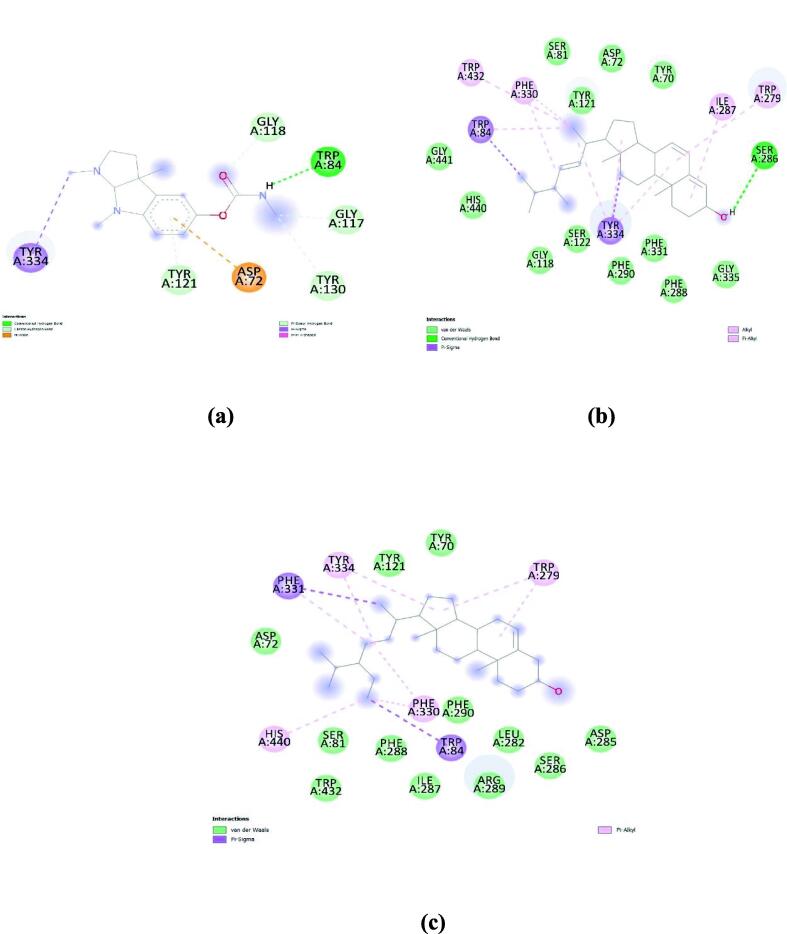

Docking studies of Acetylcholinesterase showed that Eserine (standard) had a binding energy of −8.9 kcal/mol and Ergosta-4,6,22-trien-3.-beta.-ol showed the least binding energy (-12 kcal/mol) followed by beta-Sitosterol (-11.6 kcal/mol) and beta-Sitosterol acetate (-11.4 kcal/mol). Fig. 3. represents the molecular interaction between these compounds and acetylcholinesterase.

Fig. 3.

Molecular interaction of (a) Eserine (standard); (b) Ergosta-4,6,22-trien-3.-beta.-ol; and (c) Beta-Sitosterol against active site of acetylcholinesterase.

In the case of tyrosinase, Kojic acid (standard) showed a binding energy of −5.7 kcal/mol. Whereas a-Neooleana-3,12-diene showed even better binding energy (-8.3 kcal/mol). Followed by Pseudotaraxasterol (-8.1 kcal/mol) and β-Amyrin (-8.0 kcal/mol). Molecular interactions of these compounds with tyrosinase are represented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Molecular interactions of (a) Kojic Acid (standard); (b) a-Neooleana-3,12-diene; and (C) Pseudotaraxasterol with Tyrosinase.

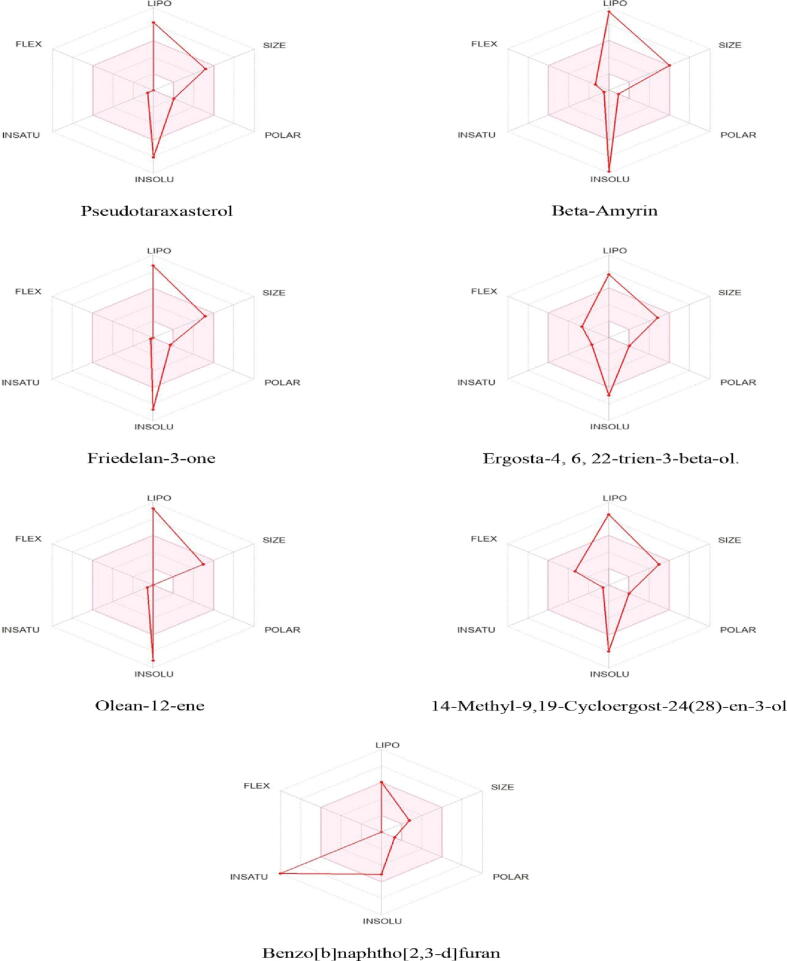

3.10. Evaluation of ADMET characteristics.

The results of ADMET studies are compiled in Table S8 and S9. All the compounds showed only 1 violation of Lipinski’s rule, showing that they are orally bioavailable drugs. Whereas Benzo[b]naphtho[2,3-d]furan violated zero criteria and possessed high gastrointestinal absorption and blood–brain barrier penetration. The bioavailability radar is shown in Fig. 5. The results of in silico toxicity prediction through ProTox-II compiled in Table S10. showed that all the best-docked compounds have low toxic potential. Whereas, β-Amyrin and pseudotaraxasterol are non-toxic.

Fig. 5.

The bioavailability radar, pink area shows the best physicochemical indicators such as solubility, lipophilicity, polarity, size, saturation, and flexibility for oral bioavailability.

4. Discussion

Primary and secondary metabolites produced by plants govern important functions for plants, for instance, primary metabolites oversee photosynthesis, growth, development, and respiration. Whereas, secondary metabolites are useful in ethnomedicinal perspectives (Crozier et al., 2008). For instance, alkaloids possess anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, antiviral, and anti-tumor activities (Cahlíková et al., 2020). Tannins, phenols, and flavonoids possess antioxidant and antitumor potential (Muniyandi et al., 2019). Saponins have anti-inflammatory, Antidiabetic, antibacterial, and antitumor activity. The preliminary phytochemical profiling of EELF showed that extract is a great source of these primary and secondary metabolites. Owing to the presence of these bioactive metabolites, L. fragilis can be considered an important therapeutic plant. The extract also revealed a high value of TPC and TFC however, a higher quantity of TPC as compared to TFC was present in the extract. Hence, the ethanolic extract is proved to be a suitable solvent in the preparation of plant extracts with rich polyphenolic content. Therefore, the pharmacological evaluation of ethanolic extracts is of prime significance due to high polyphenolic content.

GC–MS analysis is widely applied for the tentative identification of secondary metabolites present in plant extracts (Yousuf et al., 2022). In recent times, the use of this efficient tool has increased and has provided a vital scientific platform for the chemical profiling of medicinal plants (Aye et al., 2019). In the present analysis, GC–MS profiling of EELF showed 47 compounds. Many of these identified compounds have been reported to possess medicinal properties for example, β-Amyrin possesses antihyperglycemic, hypolipidemic agents, and anti-tyrosinase activity (Nogueira et al., 2019, Viet et al., 2021). Beta-Sitosterol is usually used in hypercholesterolemia, heart problems, cancer, neuroprotection, and diabetes (Saeidnia et al., 2014). Friedelan-3-one is an antidiabetic agent (Harley et al., 2021). The pharmacological activities of EELF may be due to these identified compounds so we planned to establish a safety profile and analyze the antioxidant, enzyme inhibition (antidiabetic, skin, and neuroprotective), antibacterial and antiviral potential of L. fragilis.

Hematological parameters are one the most essential indicators of human and animal physiological and pathological status as these parameters are targeted by chemical toxins (Nghonjuyi et al., 2016). In toxicological studies hematopoietic system plays a vital role in assessing toxicity, while blood analysis is appropriate for the evaluation of risk as the abnormalities in the values of animal blood can be extrapolated to predict toxicity in humans (Olson et al., 2000). The hematological analysis of chicks showed that different doses of EELF have no detrimental effect on the blood system. However, a small increase in lymphocytes and leucocytes count of the groups treated with EELF after 2 weeks of administration was observed, which suggests that EELF contains bioactive components capable of boosting the immune system as the increase in leucocytes indicates the boosting of the immune system (Gill and Rutherfurd 2001). In addition, the biochemical parameters, body weight, and organ indexes of treated chicks were also examined at the same intervals. Oral administration of EELF for continuous 21 days showed no significant difference in the biochemical parameters, Body weight and organ indexes. Hence, EELF can be considered safe and non-toxic because no significant deteriorative changes in the experimental chicks as compared to control were observed throughout the toxicological evaluation.

Radicals with unpaired electrons and the capability to damage biomolecules are termed reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS can also damage DNA resulting in mutations and different diseases (Halliwell, 1990, Halliwell, 1995, Alho and Leinonen, 1999, Martelli and Giacomini, 2018). Antioxidants considerably delay or stop oxidative stress and discovering novel antioxidants from natural sources is of great importance as they block oxidation, hence preventing oxidative stress-related diseases (Zengin et al., 2018, Basit et al., 2022). The extract showed strong antioxidant activity correlating to polyphenolic content present in the extract (i.e. higher the polyphenolic content stronger the antioxidant) (Chavan et al., 2013). The antioxidant potential of EELF might be the underlying mechanism responsible for its pharmacological activities, as the involvement of ROS in the pathophysiology of several diseases including diabetes, ulcer, and aging is well established (Ahmad et al., 2019).

To combat global health-associated crises, the inhibition of clinically important enzymes is a vital strategy. α-glucosidase is a clinically important enzyme that is present in GIT and is involved in carbohydrate digestion hence regulating blood glucose levels (Mollica et al., 2019). The unchecked elevated level of blood sugar can result in diabetes, which can cause kidney, cardiovascular, and eye disorders. Therefore, α-glucosidase inhibition is of vital importance for curing diabetes (Bhandurge et al., 2010). The extract showed an IC50 value of 36.53 ± 0.05 µg/mL and agarose (standard) gave IC50 value of 5.87 ± 0.01 µg/mL. An earlier study on the ethanolic extract of L. nudicaulis showed a hypoglycemic effect on diabetic rats at a dose of 250 and 500 mg/kg/day (El-Newary et al., 2021). The presence of compounds such as β-Amyrin, β-Sitosterol, Friedelan-3-one, etc. is interrelated to the anti-diabetic activity of the extract. Likewise, acetylcholinesterase is another important enzyme that converts acetylcholine into choline and acetic acid hence playing a key part in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis (García-Ayllón et al., 2011). AD is a neurodegenerative disease causing irreversible damage to the brain. As a result, cholinergic neurons are affected and neurotransmission is terminated (Ritter 2012). Recent experiments revealed that inhibition of AChE enhances cholinergic neurotransmission in CNS and treat AD (Bursal et al., 2021). Commercially available synthetic drugs currently in use for treating these diseases have limitations associated with their adverse reactions (Zengin et al., 2016, Zengin et al., 2017). In the current research, EELF showed an IC50 value of 33.28 ± 0.08 µg/mL, while the Eserine (standard) gave 1.87 ± 0.01 µg/mL. Previous research work showed that the methanolic extract of L. procumbens possesses cholinesterase inhibition activity at 100 and 200 mg/kg B.W. (Khan 2012). Moreover, triterpenoids and sterols present in the ethyl acetate extract of S. maritima provide its neuroprotective activity against neuroinflammation occurring in neurodegenerative diseases (George et al., 2020). GC–MS of EELF also showed the presence of sterols and triterpenoids emphasizing the neuroprotective property of the plant and potential treatment for neurodegenerative diseases. EELF was also tested against tyrosinase involved in the production of melanin. Tyrosinase plays a vital role in skin disorders and its inhibitors are beneficial in treating hyperpigmentation in humans (Parvez et al., 2006). EELF showed an IC50 value of 27.85 ± 0.04 µg/mL against tyrosinase and Kojic acid (standard) showed an IC50 value of 2.87 ± 0.01 µg/mL. Tyrosinase inhibition activity is correlated to the presence of polyphenolic compounds as it is reported earlier that polyphenolic compounds bind reversibly to tyrosinase enzyme and reduce its catalytic activity (Chang 2009). EELF also contains polyphenols contributing to its tyrosinase inhibition activity. Conclusively, EELF is rich in antioxidants and secondary metabolites making it inhibitor of clinically important enzymes.

GC–MS analysis revealed that EELF contains many compounds which may synergistically be responsible for its antibacterial and antiviral potential namely Octadecanoic acid (Jasim et al., 2015), β-caryophyllene (Tariq et al., 2019), alpha-Linoleic acid (Krishnaveni et al., 2014), Phthalic acid (Huang et al., 2021), etc. as they all possess antibacterial and antiviral activities. Hence, the plant extract was subjected to antibacterial and antiviral assays. L. fragilis showed significant antimicrobial activity as the zones of inhibition computed against all the tested strains were greater than 9 mm. As for the antiviral assay, EELF showed very strong activity even comparable to Acyclovir (standard) with a titer count of 00 against all tested strains.

Computational chemistry, especially in-silico molecular docking is a reliable and accurate tool for predicting the interaction of ligands with targeted molecules, their binding energy, underlying mechanisms and correlating the biological activities of therapeutic plants observed in the experiments on a molecular basis (Baig et al., 2018). All the tentative compounds along with standards were docked with acetylcholinesterase, tyrosinase, and α-glucosidase. The inhibition of enzymes was mainly attributed to the formation of Van der Waals, hydrogen bond, pi-alkyl, alkyl, and pi-sigma interactions at the active sites of the enzymes. Compounds like β-Amyrin, Ergosta-4,6,22-trien-3-beta-ol, Pseudotaraxasterol, and Beta-Sitosterol showed even better binding as compared to standards.

To determine the drug-likeness, physiochemical properties, and pharmacodynamics of the compounds, the SwissADME was used (Al-Qahtani et al., 2023). ADME properties provide insight whether molecules under study can be used as future medicines or not (Türkan et al., 2021). Compounds having lower molecular weight, Lipophilicity, and lower hydrogen bond capacity possess good absorption, high bioavailability, and distribution (Daina et al., 2014, Duffy et al., 2015). If a chemical compound follows all the criteria of Lipinski’s rule it can show a drug-like behavior and considered as potential therapeutic agent. On the other hand, if a chemical compound fails to follow more than one Lipinski’s criteria it is considered an orally unavailable drug. Lipinski’s rule has the following five criteria: (1) Molecular weight (less than 500); (2) Lipophilicity (Log Po/w less than 5); (3) Molecular refractivity (40–130); (4) Hydrogen bond acceptor (≤10); Hydrogen bond donor (less than equal to 5) (Lipinski 2004). All the best-docked compounds showed only one violation showing that all the compounds are orally bioavailable drugs. To predict toxicity, the PROTOX-II program makes use of the chemical structure and compares it with other chemical compounds with known toxicity (Banerjee et al., 2018). The results of in silico toxicity analysis showed that all the best-docked compounds have low toxic potential. Whereas, β-Amyrin and pseudotaraxasterol are non-toxic.

5. Conclusion

In this study, L. fragilis ethanol extract (EELF) was explored for the first time for its phytochemical composition, in-vivo toxicity, in-vitro biological potential, and in-silico computational studies. The chemical profiling of EELF showed presence of important primary, and secondary metabolites with pharmacologically significant chemical compounds revealed in the GC–MS analysis. Hence, the extract showed antioxidant, enzyme inhibition, antibacterial, and antiviral activities. The results of in-vivo toxicological evaluation showed the ethanol extract safe after oral administration at different doses for 21 days. The enzyme inhibition ability was also tested theoretically through docking studies, and underlying mechanisms were reported which further supported the enzyme inhibition potential of the plant. ADMET studies for best-docked compounds revealed that these compounds followed Lipinski’s rule rendering them as potential therapeutic agents. Overall, it can be demonstrated that L. fragilis is a safe medicinal plant that can be used as an important source of natural antioxidants, inhibitors of clinically significant enzymes, and antimicrobials that can serve as leads in designing novel phytopharmaceuticals. It is suggested that further studies in the future should be done on the isolation and pharmacological profiling of the compounds tentatively identified in this study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors are thanks to Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2023R504), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University. Production and hosting by Elsevier.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.04.028.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Aati H.Y., Anwar M., Al-Qahtani J., et al. Phytochemical profiling, in vitro biological activities, and in-silico studies of Ficus vasta Forssk.: An unexplored plant. Antibiotics. 2022;11(9):1155. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11091155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S., Hassan A., Rehman T., et al. In vitro bioactivity of extracts from seeds of Cassia absus L. growing in Pakistan. Journal of Herbal Medicine. 2019;16 doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2019.100258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M., Khan K.-u.-R., Ahmad S., et al. Comprehensive phytochemical profiling, biological activities, and molecular docking studies of Pleurospermum candollei: An insight into potential for natural products development. Molecules. 2022;27(13):4113. doi: 10.3390/molecules27134113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn K. The worldwide trend of using botanical drugs and strategies for developing global drugs. BMB Rep. 2017;50(3):111–116. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2017.50.3.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aktumsek A., Zengin G., Guler G.O., et al. Antioxidant potentials and anticholinesterase activities of methanolic and aqueous extracts of three endemic Centaurea L. species. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013;55:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alho H., Leinonen J. [1] Total antioxidant activity measured by chemiluminescence methods. Methods in Enzymology, Elsevier. 1999;299:3–15. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)99004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qahtani J., Abbasi A., Aati H.Y., et al. Phytochemical, Antimicrobial, Antidiabetic, Thrombolytic, anticancer Activities, and in silico studies of Ficus palmata Forssk. Arab. J. Chem. 2023;16(2) doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Auiewiriyanukul W., Saburi W., Kato K., et al. Function and structure of GH 13_31 α-glucosidase with high α-(1→ 4)-glucosidic linkage specificity and transglucosylation activity. FEBS Lett. 2018;592(13):2268–2281. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aye M.M., Aung H.T., Sein M.M., et al. A review on the phytochemistry, medicinal properties and pharmacological activities of 15 selected Myanmar medicinal plants. Molecules. 2019;24(2):293. doi: 10.3390/molecules24020293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz M., Ahmad S., Iqbal M.N., et al. Phytochemical, pharmacological, and In-silico molecular docking studies of Strobilanthes glutinosus Nees: An unexplored source of bioactive compounds. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022;147:618–627. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2021.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baig M.H., Ahmad K., Rabbani G., et al. Computer aided drug design and its application to the development of potential drugs for neurodegenerative disorders. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018;16(6):740–748. doi: 10.2174/1570159X15666171016163510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee P., Eckert A.O., Schrey A.K., et al. ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W257–W263. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On P., Millard C., Harel M., et al. Kinetic and structural studies on the interaction of cholinesterases with the anti-Alzheimer drug rivastigmine. Biochemistry. 2002;41(11):3555–3564. doi: 10.1021/bi020016x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basit A., Ahmad S., Naeem A., et al. Chemical profiling of Justicia vahlii Roth. (Acanthaceae) using UPLC-QTOF-MS and GC-MS analysis and evaluation of acute oral toxicity, antineuropathic and antioxidant activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022;287 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla N., Ingle N., Patri S.V., et al. Phytochemical analysis of Moringa oleifera leaves extracts by GC-MS and free radical scavenging potency for industrial applications. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2021;28(12):6915–6928. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.07.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandurge P., Rajarajeshwari N., Alagawadi K., et al. Antidiabetic and hyperlipaemic effects of Citrus maxima Linn fruits on alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Int. J. Drug Dev. Res. 2010;2(2):273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Bursal E., Turkan F., Buldurun K., et al. Transition metal complexes of a multidentate Schiff base ligand containing pyridine: synthesis, characterization, enzyme inhibitions, antioxidant properties, and molecular docking studies. Biometals. 2021;34:393–406. doi: 10.1007/s10534-021-00287-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahlíková L., Breiterová K., Opletal L. Chemistry and biological activity of alkaloids from the genus Lycoris (Amaryllidaceae) Molecules. 2020;25(20):4797. doi: 10.3390/molecules25204797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T.-S. An updated review of tyrosinase inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009;10(6):2440–2475. doi: 10.3390/ijms10062440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan J.J., Gaikwad N.B., Kshirsagar P.R., et al. Total phenolics, flavonoids and antioxidant properties of three Ceropegia species from Western Ghats of India. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2013;88:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2013.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheriti A., Belboukhari M., Belboukhari N., et al. Phytochemical and biological studies on Launaea Cass. genus (Asteraceae) from Algerian Sahara. Phytochemistry. 2012;11:67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Crozier A., Clifford M.N., Ashihara H. John Wiley & Sons; 2008. Plant secondary metabolites: occurrence, structure and role in the human diet. [Google Scholar]

- Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. iLOGP: a simple, robust, and efficient description of n-octanol/water partition coefficient for drug design using the GB/SA approach. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014;54(12):3284–3301. doi: 10.1021/ci500467k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilshad R., Ahmad S., Aati H.Y., et al. Phytochemical profiling, in vitro biological activities, and in-silico molecular docking studies of Typha domingensis. Arab. J. Chem. 2022;15(10) doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy F.J., Devocelle M., Shields D.C. Computational approaches to developing short cyclic peptide modulators of protein–protein interactions. Computational Peptidology, Springer. 2015;1268:241–271. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2285-7_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Darier S.M., Kamal S.A., Marzouk R.I., et al. Anti-proliferative activity of Launaea fragilis (Asso) pau and Launaea nudicaulis (L.) hookf extracts. J Sci Tech Res. 2021;35(2):27492–27496. doi: 10.26717/BJSTR.2021.35.005674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellman G.L., Courtney K.D., Andres V., Jr, et al. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961;7(2):88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Newary S.A., Afifi S.M., Aly M.S., et al. Chemical Profile of Launaea nudicaulis Ethanolic Extract and Its Antidiabetic Effect in Streptozotocin-Induced Rats. Molecules. 2021;26(4):1000. doi: 10.3390/molecules26041000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Ayllón M.-S., Small D.H., Avila J., et al. Revisiting the role of acetylcholinesterase in Alzheimer’s disease: cross-talk with P-tau and β-amyloid. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2011;4:22. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George B., Varathan P., Suchithra T. Meta-analysis on big data of bioactive compounds from mangrove ecosystem to treat neurodegenerative disease. Scientometrics. 2020;122(3):1539–1561. doi: 10.1007/s11192-020-03355-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffar A., Hussain R., Abbas G., et al. Cumulative Effects of Sodium Arsenate and Diammonium Phosphate on Growth Performance, Hemato-Biochemistry and Protoplasm in Commercial Layer. Pakistan Vet. J. 2017;37(2):257–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ghalloo B.A., Khan K.-u.-R., Ahmad S., et al. Phytochemical Profiling, In Vitro Biological Activities, and In Silico Molecular Docking Studies of Dracaena reflexa. Molecules. 2022;27(3):913. doi: 10.3390/molecules27030913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill H.S., Rutherfurd K.J. Probiotic supplementation to enhance natural immunity in the elderly: effects of a newly characterized immunostimulatory strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 (DR20™) on leucocyte phagocytosis. Nutr. Res. 2001;21(1–2):183–189. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5317(00)00294-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grochowski D.M., Uysal S., Zengin G., et al. In vitro antioxidant and enzyme inhibitory properties of Rubus caesius L. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2019;29(3):237–245. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2018.1533532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. How to characterize a biological antioxidant. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 1990;9(1):1–32. doi: 10.3109/10715769009148569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Antioxidant characterization: methodology and mechanism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995;49(10):1341–1348. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00088-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley B.K., Amponsah I.K., Ben I.O., et al. Myrianthus libericus: Possible mechanisms of hypoglycaemic action and in silico prediction of pharmacokinetics and toxicity profile of its bioactive metabolite, friedelan-3-one. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021;137 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayat M.M., Uzair M. Biological potential and GC-MS analysis of phytochemicals of Farsetia hamiltonii (Royle) Biomed. Res. 2019;30:609–616. [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Zhu X., Zhou S., et al. Phthalic acid esters: Natural sources and biological activities. Toxins. 2021;13(7):495. doi: 10.3390/toxins13070495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasim H., Hussein A.O., Hameed I.H., et al. Characterization of alkaloid constitution and evaluation of antimicrobial activity of Solanum nigrum using Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) J. Pharmacogn. Phytother. 2015;7(4):56–72. doi: 10.5897/JPP2015.0346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan R.A. Effects of Launaea procumbens on brain antioxidant enzymes and cognitive performance of rat. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012;12(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khursheed A., Ahmad S., Khan K.-u.-R., et al. Efficacy of Phytochemicals Derived from Roots of Rondeletia odorata as Antioxidant, Antiulcer, Diuretic, Skin Brightening and Hemolytic Agents—A Comprehensive Biochemical and In Silico Study. Molecules. 2022;27(13):4204. doi: 10.3390/molecules27134204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnaveni M., Dhanalakshmi R., Nandhini N. GC-MS analysis of phytochemicals, fatty acid profile, antimicrobial activity of Gossypium seeds. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2014;27(1):273–276. [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C.A. Lead-and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004;1(4):337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli G., Giacomini D. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities for natural and synthetic dual-active compounds. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;158:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica A., Zengin G., Durdagi S., et al. Combinatorial peptide library screening for discovery of diverse α-glucosidase inhibitors using molecular dynamics simulations and binary QSAR models. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019;37(3):726–740. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2018.1439403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muniyandi K., George E., Sathyanarayanan S., et al. Phenolics, tannins, flavonoids and anthocyanins contents influenced antioxidant and anticancer activities of Rubus fruits from Western Ghats. India. Food Science and Human Wellness. 2019;8(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2019.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nghonjuyi N.W., Tiambo C.K., Taïwe G.S., et al. Acute and sub-chronic toxicity studies of three plants used in Cameroonian ethnoveterinary medicine: Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. (Xanthorrhoeaceae) leaves, Carica papaya L. (Caricaceae) seeds or leaves, and Mimosa pudica L. (Fabaceae) leaves in Kabir chicks. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;178:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisar R., Ahmad S., Khan K.-u.-R., et al. Metabolic profiling by GC-MS, in vitro biological potential, and in silico molecular docking studies of Verbena officinalis. Molecules. 2022;27(19):6685. doi: 10.3390/molecules27196685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira A.O., Oliveira Y.I.S., Adjafre B.L., et al. Pharmacological effects of the isomeric mixture of alpha and beta amyrin from Protium heptaphyllum: a literature review. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019;33(1):4–12. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson H., Betton G., Robinson D., et al. Concordance of the toxicity of pharmaceuticals in humans and in animals. Regul. Toxicol. Pharm. 2000;32(1):56–67. doi: 10.1006/rtph.2000.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanisamy U.D., Ling L.T., Manaharan T., et al. Rapid isolation of geraniin from Nephelium lappaceum rind waste and its anti-hyperglycemic activity. Food Chem. 2011;127(1):21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.12.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen S., Saleem H., Sarfraz M., et al. Phytochemical profiling, In vitro antioxidant and identification of urease inhibitory metabolites from Erythrina suberosa flowers by GC-MS analysis and docking studies. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021;143:422–427. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2021.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parvez S., Kang M., Chung H.S., et al. Survey and mechanism of skin depigmenting and lightening agents. Phytotherapy Research: An International Journal Devoted to Pharmacological and Toxicological Evaluation of Natural Product Derivatives. 2006;20(11):921–934. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter J.M. Drugs for Alzheimer's disease. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012;73(4):501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeer N.B., Llorent-Martínez E.J., Bene K., et al. Chemical profiling, antioxidant, enzyme inhibitory and molecular modelling studies on the leaves and stem bark extracts of three African medicinal plants. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019;174:19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2019.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeidnia S., Manayi A., Gohari A.R., et al. The story of beta-sitosterol-a review. European Journal of Medicinal Plants. 2014;4(5):590. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem H., Zengin G., Locatelli M., et al. Pharmacological, phytochemical and in-vivo toxicological perspectives of a xero-halophyte medicinal plant: Zaleya pentandra (L.) Jeffrey. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019;131 doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sendovski M., Kanteev M., Ben-Yosef V.S., et al. First structures of an active bacterial tyrosinase reveal copper plasticity. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;405(1):227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahid A., Rao H., Aati H.Y., et al. Phytochemical Profiling of the Ethanolic Extract of Zaleya pentandra L. Jaffery and Its Biological Activities by In-Vitro Assays and In-Silico Molecular Docking. Appl. Sci. 2023;13(1):584. doi: 10.3390/app13010584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad M.N., Javed M.T., Shabir S., et al. Effects of feeding urea and copper sulphate in different combinations on live body weight, carcass weight, percent weight to body weight of different organs and histopathological tissue changes in broilers. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2012;64(3):141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad M.N., Ahmad S., Tousif M.I., et al. Profiling of phytochemicals from aerial parts of Terminalia neotaliala using LC-ESI-MS2 and determination of antioxidant and enzyme inhibition activities. PLoS One. 2022;17(3):e0266094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Bhardwaj G., Cannoo D.S. Antioxidant potential, GC/MS and headspace GC/MS analysis of essential oils isolated from the roots, stems and aerial parts of Nepeta leucophylla. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021;32 doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2021.101950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tariq S., Wani S., Rasool W., et al. A comprehensive review of the antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral potential of essential oils and their chemical constituents against drug-resistant microbial pathogens. Microb. Pathog. 2019;134 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi A., Misra K. Molecular docking: A structure-based drug designing approach. JSM Chem. 2017;5(2):1042–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Türkan F., Taslimi P., Abdalrazaq S.M., et al. Determination of anticancer properties and inhibitory effects of some metabolic enzymes including acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase, alpha-glycosidase of some compounds with molecular docking study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021;39(10):3693–3702. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1768901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velavan S. Phytochemical techniques-a review. World Journal of Science and Research. 2015;1(2):80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Viet T.D., Xuan T.D., Anh L.H. α-Amyrin and β-Amyrin Isolated from Celastrus hindsii Leaves and Their Antioxidant, Anti-Xanthine Oxidase, and Anti-Tyrosinase Potentials. Molecules. 2021;26(23):7248. doi: 10.3390/molecules26237248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf M., Khan H.M.S., Rasool F., et al. Chemical profiling, formulation development, in vitro evaluation and molecular docking of Piper nigrum Seeds extract loaded Emulgel for anti-Aging. Molecules. 2022;27(18):5990. doi: 10.3390/molecules27185990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengin G., Degirmenci N., Alpsoy L., et al. Evaluation of antioxidant, enzyme inhibition, and cytotoxic activity of three anthraquinones (alizarin, purpurin, and quinizarin) Human & Experimental Toxicology. 2016;35(5):544–553. doi: 10.1177/0960327115595687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengin G., Mollica A., Aktumsek A., et al. In vitro and in silico insights of Cupressus sempervirens, Artemisia absinthium and Lippia triphylla: Bridging traditional knowledge and scientific validation. European Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2017;12:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2017.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zengin G., Llorent-Martínez E.J., Fernández-de Córdova M.L., et al. Chemical composition and biological activities of extracts from three Salvia species: S. blepharochlaena, S. euphratica var. leiocalycina, and S. verticillata subsp. amasiaca. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018;111:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.09.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.