Abstract

Background

People with mental illnesses and people living in poverty have higher rates of incarceration than others, but relatively little is known about the long-term impact that incarceration has on an individual’s mental health later in life.

Objective

To evaluate prior incarceration’s association with mental health at midlife.

Design

Retrospective cohort study

Participants

Participants from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79)—a nationally representative age cohort of individuals 15 to 22 years of age in 1979—who remained in follow-up through age 50.

Main Measures

Midlife mental health outcomes were measured as part of a health module administered once participants reached 50 years of age (2008–2019): any mental health history, any depression history, past-year depression, severity of depression symptoms in the past 7 days (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression [CES-D] scale), and mental health-related quality of life in the past 4 weeks (SF-12 Mental Component Score [MCS]). The main exposure was any incarceration prior to age 50.

Key Results

Among 7889 participants included in our sample, 577 (5.4%) experienced at least one incarceration prior to age 50. Prior incarceration was associated with a greater likelihood of having any mental health history (predicted probability 27.0% vs. 16.6%; adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.9 [95%CI: 1.4, 2.5]), any history of depression (22.0% vs. 13.3%; aOR 1.8 [95%CI: 1.3, 2.5]), past-year depression (16.9% vs. 8.6%; aOR 2.2 [95%CI: 1.5, 3.0]), and high CES-D score (21.1% vs. 15.4%; aOR 1.5 [95%CI: 1.1, 2.0]) and with a lower (worse) SF-12 MCS (−2.1 points [95%CI: −3.3, −0.9]; standardized mean difference -0.24 [95%CI: −0.37, −0.10]) at age 50, when adjusting for early-life demographic, socioeconomic, and behavioral factors.

Conclusions

Prior incarceration was associated with worse mental health at age 50 across five measured outcomes. Incarceration is a key social-structural driver of poor mental health.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-022-07983-7.

Keywords: incarceration, mental health, depression, structural determinants of health, longitudinal study

Introduction

At the end of 2001, an estimated 5.6 million adults living in the USA were either currently in prison or had previously been in prison at some point in their lives.1 Since then millions more have been incarcerated as well: each year, there are approximately 577,000 admissions to state and federal prisons2 and 10.3 million admissions to local jails.3

Because the carceral system’s impact in the USA falls disproportionately on people who use substances, people with mental illness, and socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods, persons who become incarcerated have higher rates of psychiatric and substance use disorders than the general population.4,5 Beyond this selection effect, exposure to incarceration may directly lead to poorer mental health—for both individuals6–8 and whole communities.9,10 Indeed, a growing public health literature considers the criminal-legal system to be a key social-structural determinant of health and health disparities,11,12 including in the domain of mental health.13

The temporal durability of incarceration’s effect on mental health deserves additional attention. The carceral environment itself can lead to immediate deterioration in mental health.14,15 After release, the difficult process of reentering society often involves material hardships, social challenges, discrimination, and the enduring stigma of an incarceration history;16–18 the impact of such factors could plausibly persist for many years. However, notwithstanding a recent cross-sectional study by Steigerwald and colleagues,19 relatively little is known about incarceration’s long-term effect on someone’s mental health later in life, in part because national health studies often ignore this important determinant of health.20,21

Using four decades of data from a unique longitudinal cohort study, we sought to evaluate the association between prior incarceration and mental health at midlife (age 50), adjusting for early-life demographic, socioeconomic, and behavioral factors. We hypothesized that prior incarceration would be associated with worse mental health. Among those with an incarceration history, we further hypothesized that greater cumulative exposure to incarceration over the life course and younger age at initial incarceration, respectively, would each be associated with worse mental health.

Methods

Data Source and Cohort Selection

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79), a nationally representative longitudinal study administered by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.22,23 NLSY79 recruited non-institutionalized individuals who were 15 to 22 years old in 1979, conducted annual follow-up surveys through 1994, and has conducted biennial follow-up surveys ever since. Surveys were administered in person or via telephone (see Appendix 1 for more details about data source).

We included participants who survived to 50 years of age and completed NLSY79’s “Health at 50” module, an extensive battery of health-related questions given to each participant on the first biennial survey they successfully completed after their 50th birthday. Each participant completed the module once, and it was administered during the six survey rounds from 2008–2009 to 2018–2019.

The Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Review Board determined that this study did not qualify as human subjects research. Reporting in this study followed all applicable Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational cohort studies.

Measures

Three of our mental health outcomes were based on self-reported diagnoses and the other two were based on multi-item assessments of current symptoms. We identified a history of any mental health problem (including depression) using the survey item, “Has a doctor ever told you that you had emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems?” We identified depression history using the survey item, “Has a doctor ever diagnosed you as suffering from depression?” If they reported a depression history, they were also asked, “During the last 12 months, have you suffered from depression?” which we considered as a distinct outcome: past-year depression. NLSY79 administered its own abbreviated 7-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), which consisted of 7 questions about how often one has experienced various depressive symptoms in the past 7 days, each scored from 0 (rarely/none of the time) to 3 (most/all of the time). Because the sum scores were not normally distributed, we dichotomized CES-D scores as high (vs. low) if their sum score was 8 or higher; this cutoff value has been validated against the original 20-item CES-D.24 Finally, we used the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) Mental Component Score (MCS), a continuous measure (theoretical range: 0 to 100; observed range in sample: 8.9 to 70.3; observed mean 52.8 [SD 8.8]) calculated from responses to a 12-item questionnaire on mental health-related quality of life in the past 4 weeks.25,26

Our main exposure variable was any lifetime incarceration prior to the survey in which outcomes were assessed. We identified incarcerations using three sets of survey variables: in 1980, they were asked directly whether they had ever been incarcerated; and in all survey rounds, we identified incarcerations if a participant’s current type of residence was recorded as “jail/prison” or if they were not surveyed that round and the reason was coded as “incarcerated.”

We identified demographic and early-life characteristics that were potential confounders. We included participants’ sex and date of birth (scaled in units of years before or after January 1, 1960). NLSY79 categorized participants’ race and ethnicity into three mutually exclusive groups—Hispanic (of any race), non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic non-Black—based primarily on survey responses by the participant or the head of their household at the beginning of the cohort study, although race was also assigned in part based on the interviewers’ perceptions27 (despite the limitations of NLSY’s race and ethnicity variable, which have been described elsewhere,28,29 a more suitable alternative was not available).

Using retrospective questions about their childhood household, we identified whether each participant had lived with both of their biological parents at 14 years of age. We identified exposure to physical abuse in childhood if a participant chose “more than once” as their response to the question “Before age 18, how often did a parent or adult in your home ever hit, beat, kick or physically harm you in any way? Do not include spanking. Would you say never, once, or more than once?”—which is consistent with previously published measures.30–35 For immigration history, we categorized a participant as a first-generation immigrant if they had been born in another country; second-generation if they were born in the USA and at least one of their parents had been born in another country; and third-generation or higher if they and both of their parents were born in the USA. We also identified whether participants reported having US citizenship.

We identified each participant’s level of education at age 22 as well as the highest level of education attained by either of their parents, both measured in years of formal education completed (continuous variables). Annual household income was rescaled as a percentage of the year-specific federal poverty level and log-transformed (to reduce skew), and we used the mean of all available values from age 22 and before as our income measure. We identified receipt of public assistance income at or before age 22, as a marker of poverty.

We identified early-life disability at age 22 if participants reported that a health condition prevented or limited their ability to work (not including normal pregnancy). Early-life body mass index (BMI), a known prospective risk factor for depression,36 was calculated using self-reported height and weight in 1981.

We identified whether a participant had started smoking cigarettes daily by age 22, using retrospective survey questions about lifetime smoking history. For early-life alcohol use, we identified whether a participant ever reported frequent binge drinking in 1982 (the earliest available measure) if participants reported having had 6 or more drinks on at least 4 occasions in the past 30 days, which approximates a previously published measure, weekly heavy episodic drinking.37,38 Using survey items from 1980, we assessed whether participants reported any past-year cannabis use, use of other illicit drugs, and engagement in illegal activities, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

We used multivariable logistic regression (for the four dichotomous outcomes) and linear regression (for SF-12 MCS) models to assess the association between incarceration and each mental health outcome, adjusting for demographic and early-life characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, family structure, childhood abuse, immigration, citizenship, education, parental education, income, public assistance, disability, BMI, smoking, drinking, cannabis use, drug use, and illegal activities). All regression models accounted for NLSY79’s complex sampling design, including stratification, clustering, and weights. We also performed an exploratory subgroup analysis among those with prior incarceration to assess whether mental health outcomes were associated with any of the following three aspects of incarceration history: age at first incarceration, cumulative exposure to incarceration (number of surveys in which an incarceration was recorded), and time since the last incarceration. All statistical analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) from August 13, 2021, to October 15, 2022. Two-sided p<.05 indicated statistical significance.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess two potential sources of bias. First, we estimated the potential for an unmeasured confounder to explain away the association we found between incarceration and each outcome, using E-values39 for dichotomous outcomes and an analogous method40 for SF-12 MCS. Second, because some of the early-life covariates were measured after some participants had already been incarcerated, we assessed the impact of this temporal overlap by modifying our main analysis in the following ways: (a) excluding participants who had already been incarcerated by age 22; (b) dropping the variables which suffered most from this temporal overlap (namely, participant education, family income, BMI, smoking, and alcohol use); and (c) both of these modifications together.

For missing covariate data, we performed hot-deck multiple imputation (with 10 imputations) with the Approximate Bayesian Bootstrap method41,42 using the SURVEYIMPUTE procedure in SAS, defining imputation cells by sampling stratum, sex, race/ethnicity, and age in 1979 (integer years). Fourteen out of 19 covariates had any missing values, ranging from only 1 participant (<0.1%) to 489 participants (6.2%) (Table 1). In total, 1548 (19.6%) of the participants had missing values for one or more covariates.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics, Overall and by Incarceration History*

| No incarceration history | Prior incarceration history | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants | 7312 | 577 | |

| Weighted % of total= | 94.6% | 5.4% | p-value† |

| Age in 1979 | 0.03 | ||

| 15–16 | 23.9 | 26.9 | |

| 17–18 | 24.7 | 29.1 | |

| 19–20 | 25.7 | 21.2 | |

| 21–22 | 25.7 | 22.8 | |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 48.8 | 86.1 | |

| Female | 51.2 | 13.9 | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| Black | 13.2 | 31.3 | |

| Hispanic | 6.4 | 9.6 | |

| White/other | 80.4 | 59.1 | |

| Lived with both biological parents at age 14 | 75.7 | 53.1 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 0.1 | 0.7 | |

| Childhood physical abuse, before age 18 | 10.8 | 20.3 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 3.5 | 4.9 | |

| Immigration generation | 0.89 | ||

| 1st | 4.0 | 3.8 | |

| 2nd | 5.2 | 4.7 | |

| 3rd or higher | 90.3 | 90.2 | |

| Missing | 0.6 | 1.4 | |

| US citizen (1984) | 97.0 | 95.9 | 0.24 |

| Missing | 0.8 | 1.0 | |

| Highest grade completed at 22, mean (SD) | 12.5 (1.8) | 10.8 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Highest grade completed by either parent, mean (SD) | 12.6 (3.1) | 11.2 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 2.6 | 5.2 | |

| Family income (%FPL) at ages 15–22, median [IQR] | 271 [173, 398] | 168 [113, 263] | <0.001 |

| Missing | 4.9 | 3.9 | |

| Public assistance receipt (ages 15–22) | 15.0 | 30.0 | <0.001 |

| Missing | <.1 | none | |

| Any disability at age 22 | 4.5 | 5.4 | 0.38 |

| Missing | <.1 | none | |

| BMI (1981), mean (SD) | 22.9 (3.7) | 23.1 (3.2) | 0.13 |

| Missing | 2.6 | 4.6 | |

| Ever daily smoker by age 22 | 47.2 | 78.6 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 1.3 | 1.3 | |

| Frequent binge drinking, past month (1982) | 16.8 | 25.9 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 2.2 | 6.2 | |

| Cannabis use, past year (1980) | 45.4 | 65.9 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 5.9 | 7.2 | |

| Drug use, past year (1980) | 19.3 | 34.4 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 5.8 | 8.0 | |

| Delinquency/illegal activities, past year (1980) | 62.9 | 84.5 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 5.0 | 5.8 |

%FPL, percent of the federal poverty level (for a given year and family size); BMI, body mass index

*Values reported are survey-weighted percentages, unless otherwise specified

†p-values are from Pearson chi-square tests for categorical variables and two-tailed t-tests for continuous variables

Results

Of the original 9964 NLSY79 participants, 619 died before age 50 and therefore were ineligible for our study. An additional 1456 participants were lost to follow-up, and the remaining 7889 successfully completed the Health at 50 module and therefore were included in our study sample (Supplemental Figure). There were differences in early-life characteristics between our study sample and those who were lost to follow-up, with those lost to follow-up tending to have higher socioeconomic status, e.g., higher income and more education (Supplemental Table 1). Due to differential item non-response, the actual sample size for each outcome was slightly lower than our overall sample size, ranging from 7804 for SF-12 MCS to 7887 for any mental health history.

Adjusting for survey weights, our overall study population was 51% male, 14% non-Hispanic Black, 7% Hispanic (of any race), and evenly distributed in age. In total, 577 participants (5.4%) experienced at least one incarceration by 50 years of age (Table 1). Among participants with prior incarceration, the median (IQR) number of surveys with an incarceration was 2 (1, 4), and the median (IQR) age at first incarceration was 24 (19, 33) years. Those with prior incarceration were more likely to be male and Black or Hispanic, and had lower average levels of education and income. Those without prior incarceration were less likely to report substance use and illegal activities in early life.

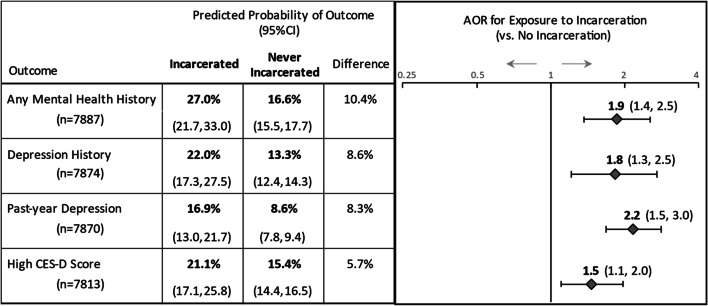

For all four dichotomous outcomes, those with a history of incarceration had higher unadjusted rates compared to those who were never incarcerated (Supplemental Table 2). In our multivariable analysis, those with prior incarceration, compared to those without, were significantly more likely to have a history of any mental health problem (predicted probability 27.0% vs. 16.6%; adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.9 [95%CI: 1.4, 2.5]), any history of depression (22.0% vs. 13.3%; aOR 1.8 [95%CI: 1.3, 2.5]), past-year depression (16.9% vs. 8.6%; aOR 2.2 [95%CI: 1.5, 3.0]), and high CES-D score (21.1% vs. 15.4%; aOR 1.5 [95%CI: 1.1, 2.0]) (Fig. 1; see Supplemental Table 3 for estimates for all covariates). Adjusting for early-life factors, those with prior incarceration had a lower (worse) SF-12 MCS by 2.1 points (95%CI: −3.3, −0.9), standardized mean difference (i.e., Cohen’s d)43 −0.24 (95%CI −0.37, −0.10) (Table 2; see Supplemental Table 4 for estimates for all covariates).

Table 2.

Mental Health-Related Quality of Life at Age 50 Years by Incarceration History

| SF-12 Mental Component Score (n=7804) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior incarceration | No prior incarceration | Between-groups difference | ||||||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Absolute mean difference (95%CI) | Standardized mean difference‡ (95%CI) | |||||||||

| Unadjusted* | 50.3 | 49.2 | 51.5 | 53.0 | 52.7 | 53.2 | −2.6 | −3.8 | −1.4 | −0.30 | −0.43 | −0.16 |

| Adjusted† | 50.9 | 49.7 | 52.0 | 53.0 | 52.8 | 53.2 | −2.1 | −3.3 | −0.9 | −0.24 | −0.37 | −0.10 |

*Unadjusted estimates accounted for cluster sampling design and sample weights (but did not adjust for any covariates)

†Multivariable regression model accounted for cluster sampling design and sample weights and adjusted for early-life characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, family structure, childhood abuse, immigration, citizenship, education, parental education, income, receipt of public assistance, disability, body mass index (BMI), self-esteem, locus of control, smoking, binge drinking, marijuana use, drug use, and illegal activities)

‡Standardized mean difference calculated using Cohen’s d, which divides the absolute mean difference between exposure groups by the pooled standard deviation of the entire sample

Figure 1.

Associations of incarceration with dichotomous mental health outcomes—results of multivariable logistic regression analysis: National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979, USA, 1979 to 2019. For each of the four dichotomous mental health outcomes, results from our multivariable logistic regression analyses are shown: the adjusted/predicted probabilities for those with vs. without a history of incarceration (and absolute difference between groups) in the table on the left; and the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and 95% CI for prior incarceration in the forest plot on the right. Predicted probabilities and adjusted odds ratios were estimated from multivariable logistic regression models that accounted for cluster sampling design and sample weights and adjusted for early-life covariates (age, sex, race/ethnicity, family structure, childhood abuse, immigration, citizenship, education, parental education, income, receipt of public assistance, disability, body mass index [BMI], smoking, binge drinking, marijuana use, drug use, and illegal activities)

In our subgroup analysis of those with prior incarceration, there were virtually no significant associations between any of the outcomes and cumulative exposure to incarceration, age at first incarceration, or time since last incarceration, regardless of whether these aspects of incarceration history were coded as continuous or ordinal variables (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations Between Patterns of Incarceration History and Mental Health Outcomes at Mid-Life (Subgroup Analysis)*

| Variable type | Any mental health history n=576 aOR (95%CI) |

Depression history n=575 aOR (95%CI) |

Past-year depression n=574 aOR (95%CI) |

High CES-D score n=568 aOR (95%CI) |

SF-12 MCS n=569 Beta (95%CI) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first incarceration | Categorical | ||||||||||||||||

| ≤21 years | (n=186) | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | −0.4 | −3.0 | 2.3 | |||||||||

| 22–30 years | (n=206) | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 2.5 | −0.3 | −3.0 | 2.4 | |

| 31+ years | (n=185) | 1.6 | 0.8 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.9 | (ref.) | |||

| Continuous† | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.2 | −0.4 | 0.9 | ||

| Cumulative exposure (no. of incarcerations) | Categorical | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 time | (n=223) | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | |||||||||||

| 2–4 times | (n=190) | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 2.5 | −1.3 | −3.9 | 1.2 | |

| 5+ times | (n=168) | 1.1 | 0.5 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 2.9 | −1.0 | −3.8 | 1.8 | |

| Continuous‡ | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 0.2 | ||

| Time since last incarceration | Categorical | ||||||||||||||||

| 0–5 years | (n=113) | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | |||||||||||

| 6–15 years | (n=175) | 1.6 | 0.6 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 4.3 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 5.7 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 3.1 | −3.7 | −6.9 | −0.5§ | |

| 16+ years | (n=289) | 1.0 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 3.5 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 2.1 | −1.7 | −4.6 | 1.2 | |

| Continuous† | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.1 | −0.5 | 0.7 | ||

Abbreviations: SF-12 MCS, SF-12 Mental Component Score; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; ref, reference group

*All results displayed in the table are from multivariable regression models which accounted for cluster sampling design and sample weights and adjusted for early-life characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, family structure, childhood abuse, immigration, citizenship, education, parental education, income, receipt of public assistance, disability, body mass index (BMI), self-esteem, locus of control, smoking, binge drinking, marijuana use, drug use, and illegal activities)

†Adjusted odds ratios for a 5-year increment in the continuous variable (5-year increment used for both the age of first incarceration continuous variable and the time since last incarceration continuous variable)

‡ Adjusted odds ratios for a 1-unit increment in the continuous variable for the number of follow-up surveys with a documented incarceration

§ p<0.05 (note: no other adjusted effect estimate (aOR or beta coefficient) shown in this table reached this threshold for statistical significance)

In our first sensitivity analysis, for a hypothetical unmeasured confounder to explain away any of our results, it would have to have very strong associations (net of all covariates) with both incarceration and each outcome (see Appendix 1 and Supplemental Table 5 for details).

In our second sensitivity analysis, when we excluded participants who had already been exposed to incarceration by age 22, or dropped the covariates that had the most temporal overlap with incarceration exposure, or employed both of these modifications together, our estimates of the association between incarceration and each outcome generally increased in magnitude (Supplemental Table 6).

Discussion

In this longitudinal cohort followed for almost four decades, individuals who had experienced an incarceration in their lifetime had worse mental health at age 50, even when adjusting for a broad set of early-life social, economic, and behavioral risk factors. Our study is broadly consistent with existing research on the connection between prior incarceration and poor mental health and adds the unique perspective of longitudinal data with a long time horizon.

Large cross-sectional studies of US adults from a broad range of ages have found that prior incarceration was associated with the development of mood disorders,6 a greater burden of depressive symptoms and psychological distress,16 and lower levels of mental health well-being,7 but such studies had limited ability to disentangle possible confounding. In a cross-sectional study of older adults (65 years or older) matched on age, gender, race, and education level, prior incarceration was associated with worse CES-D scores among women but not among men.19 Among fathers in the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study cohort, current and recent (within the past 2 years) incarceration were associated with depression, but this study did not assess the impact of more remote incarceration histories.8

By using data from the Health at 50 module, our study adds a decade of follow-up time compared to two previous studies using NLSY79 data that found associations between prior incarceration and worse mental health outcomes, as measured by the “Health at 40” module. One study included problems with depression, worrying, and sleep.44 The other study found among men that initial exposure to incarceration during emerging adulthood (ages 18–24) was associated with a higher CES-D score at age 40 but did not find this association for initial incarceration at a later age.45 Our subgroup analysis did not find any such difference in mental health outcomes by age of first incarceration, and other studies on this topic have yielded mixed results. While one nationally representative cross-sectional study46 found that prior juvenile incarceration had a stronger association with lifetime suicide attempt than adult incarceration did, a longitudinal study47 of formerly incarcerated women from a national cohort found no differences in CES-D scores by age of first incarceration, by duration of incarceration, nor by number of incarceration episodes. These findings suggest that any incarceration can have significant and persistent effects on mental health while the relative amount or timing of exposure to incarceration may have little marginal impact.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. Study findings in this specific age cohort may not be generalizable to the rest of the population; however, this age cohort is the first generation to enter adulthood since the era of mass incarceration began in the 1980s.48 Attrition from follow-up did not occur at random which could have introduced bias in our sample selection, although we used sample weights that adjusted for variable completion of the Health at 50 module. Our relatively insensitive method for detecting incarcerations was likely to miss brief incarcerations that occurred between surveys, and we cannot know whether or how such misclassification errors might have biased our findings. While we adjusted for a broad array of potential confounders, it is possible that unmeasured factors still confounded our estimates of the relationships between incarceration and mental health outcomes. Nevertheless, based on our sensitivity analysis, it seems less likely that any such unmeasured confounder would be strong enough to nullify all the associations we found. As mentioned above, the structure of our data source did not allow us to measure all participants’ early-life covariates prior to when they were at risk for exposure to incarceration, but our sensitivity analysis of this issue suggested that, if anything, this overlap may have caused our estimates to be more conservative. Because many of the covariates, e.g., income, could function as either a confounder (if measured prior in exposure) or a mediator (if measured after exposure) of the relationship between incarceration and mental health, controlling for a partial mediator in this situation might have masked the full association between incarceration and mental health for some participants, which may explain the general pattern of results from this sensitivity analysis. Three of our mental health measures (any mental health history, depression history, past-year depression) have not been validated and could underestimate prevalences among people with limited access to mental healthcare. Additionally, while SF-12 MCS is a validated measure of mental health–related quality of life, we did not have a directly applicable empiric benchmark (e.g., minimum important difference) to better gauge the clinical significance of measured differences.

Conclusion

The results of this study add to a growing public health literature which finds incarceration to be a toxic exposure that worsens mental health. Because experiences of incarceration are common and yet so unevenly distributed in the USA, mass incarceration should be understood as a key social-structural determinant of health disparities—one that had remained relatively underappreciated until recently. If efforts to achieve mental health equity are to succeed, they must consider the impact that the criminal-legal system has on the well-being of many already marginalized populations.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 158 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the user services staff of the National Longitudinal Surveys of Youth, a program sponsored by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, for their assistance with understanding and using the NLSY79 cohort data.

Disclaimer

This research was conducted with restricted access to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Funding

Dr. Bovell-Ammon’s work on this study was supported by training grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to The Miriam Hospital, Lifespan, “HIV and Other Infectious Consequences of Substance Abuse” (T32DA013911) and “Lifespan/Brown Criminal Justice Research Training Program on Substance Use and HIV” (R25DA037190), and by a training grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to Boston Medical Center, the Boston University Clinical HIV/AIDS Research Training Program (T32-AI052074). The other authors did not receive any funding support for this study. The funders had no role in designing, conducting, writing, or deciding whether to publish this study. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the funder(s).

Data Availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study was generated primarily from the online database of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 which is publicly available at no cost at https://www.nlsinfo.org/investigator. However, in order to properly adjust our variance/uncertainty estimates for NLSY79’s complex sample design, our analytic dataset also included restricted access geocoded data (https://www.bls.gov/nls/request-restricted-data/nlsy-geocode-data.htm) about participants’ sampling strata and primary sampling units (or clusters). Statistical programming code and a non-restricted version of this study’s analytic dataset (containing only the publicly available data but not the restricted access data) are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. LaRochelle received consulting funds for research on opioid use disorder treatment pathways paid to his institution from OptumLabs, which was not related to this study. Drs. Bovell-Ammon and Fox have no potential or actual conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bonczar TP. Prevalence of Imprisonment in the U.S. Population, 1974-2001; 2003:12. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/prevalence-imprisonment-us-population-1974-2001

- 2.Minton TD, Zeng Z. Jail Inmates in 2020 – Statistical Tables. Bureau Just Stat; 2021:27. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/jail-inmates-2020-statistical-tables

- 3.Carson EA. Prisoners in 2020 – Statistical Tables. Bureau Just Stat; 2021:50. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/prisoners-2020-statistical-tables

- 4.Steadman HJ, Osher FC, Robbins PC, Case B, Samuels S. Prevalence of serious mental illness among jail inmates. Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC) 2009;60(6):761–765. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW, et al. The Health and Health Care of US Prisoners: Results of a Nationwide Survey. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):666–672. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schnittker J, Massoglia M, Uggen C. Out and Down: Incarceration and Psychiatric Disorders. J Health Soc Behav. 2012;53(4):448–464. doi: 10.1177/0022146512453928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundaresh R, Yi Y, Roy B, Riley C, Wildeman C, Wang EA. Exposure to the US Criminal Legal System and Well-Being: A 2018 Cross-Sectional Study. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(S1):S116–S122. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turney K, Wildeman C, Schnittker J. As Fathers and Felons: Explaining the Effects of Current and Recent Incarceration on Major Depression. J Health Soc Behav. 2012;53(4):465–481. doi: 10.1177/0022146512462400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowleg L, Maria del Río-González A, Mbaba M, Boone CA, Holt SL. Negative Police Encounters and Police Avoidance as Pathways to Depressive Symptoms Among US Black Men, 2015–2016. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(S1):S160–S166. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes K, Hamilton A, Uddin M, Galea S. The Collateral Damage of Mass Incarceration: Risk of Psychiatric Morbidity Among Nonincarcerated Residents of High-Incarceration Neighborhoods. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(1):138–143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowleg L. Reframing Mass Incarceration as a Social-Structural Driver of Health Inequity. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(S1):S11–S12. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Cloud DH. Mass Incarceration as a Social-Structural Driver of Health Inequities: A Supplement to AJPH. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(S1):S14–S15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotter M, Compton M. Criminal Legal Involvement: A Cause and Consequence of Social Determinants of Health. PS. 2022;73(1):108–111. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore KE, Siebert S, Brown G, Felton J, Johnson JE. Stressful life events among incarcerated women and men: Association with depression, loneliness, hopelessness, and suicidality. Health & Justice. 2021;9(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s40352-021-00140-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reiter K, Ventura J, Lovell D, et al. Psychological Distress in Solitary Confinement: Symptoms, Severity, and Prevalence in the United States, 2017–2018. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(S1):S56–S62. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Assari S, Miller RJ, Taylor RJ, Mouzon D, Keith V, Chatters LM. Discrimination Fully Mediates the Effects of Incarceration History on Depressive Symptoms and Psychological Distress Among African American Men. J Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2018;5(2):243–252. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0364-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Semenza DC, Link NW. How does reentry get under the skin? Cumulative reintegration barriers and health in a sample of recently incarcerated men. Social Sci Med. 2019;243:112618. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112618 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Western B, Braga AA, Davis J, Sirois C. Stress and Hardship after Prison. Am J Socio. 2015;120(5):1512–1547. doi: 10.1086/681301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steigerwald VL, Rozek DC, Paulson D. Depressive symptoms in older adults with and without a history of incarceration: A matched pairs comparison. Aging Mental Health. 2021;0(0):1–7. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2021.1984392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahalt C, Binswanger IA, Steinman M, Tulsky J, Williams BA. Confined to Ignorance: The Absence of Prisoner Information from Nationally Representative Health Data Sets. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(2):160–166. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1858-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Binswanger IA, Maruschak LM, Mueller SR, Stern MF, Kinner SA. Principles to Guide National Data Collection on the Health of Persons in the Criminal Justice System. Public Health Rep. 2019;134(1_suppl):34S–45S. doi: 10.1177/0033354919841593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Bureau of Labor Statistics National Longitudinal Surveys. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79). Accessed October 14, 2022. https://www.nlsinfo.org/content/cohorts/nlsy79

- 23.Rothstein DS, Carr D, Cooksey E. Cohort Profile: The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79) Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(1):22–22e. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine SZ. Evaluating the seven-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale short-form: a longitudinal US community study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(9):1519–1526. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0650-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. SF-12: How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales. 2nd ed. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1995.

- 27.US Bureau of Labor Statistics National Longitudinal Surveys. Race, Ethnicity & Immigration Data (NLSY79). National Longitudinal Surveys. Published November 11, 2021. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.nlsinfo.org/content/cohorts/nlsy79/topical-guide/household/race-ethnicity-immigration-data

- 28.Light A, Nandi A. Identifying race and ethnicity in the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Popul Res Pol Rev. 2007;26(2):125. doi: 10.1007/s11113-007-9021-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bovell-Ammon BJ, Xuan Z, Paasche-Orlow MK, LaRochelle MR. Association of Incarceration With Mortality by Race From a National Longitudinal Cohort Study. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(12):e2133083. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.33083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prevent Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell JA, Walker RJ, Egede LE. Associations Between Adverse Childhood Experiences, High-Risk Behaviors, and Morbidity in Adulthood. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(3):344–352. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cronholm PF, Forke CM, Wade R, et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences: Expanding the Concept of Adversity. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skarupski KA, Parisi JM, Thorpe R, Tanner E, Gross D. The association of adverse childhood experiences with mid-life depressive symptoms and quality of life among incarcerated males: exploring multiple mediation. Aging Mental Health. 2016;20(6):655–666. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1033681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bethell CD, Carle A, Hudziak J, et al. Methods to Assess Adverse Childhood Experiences of Children and Families: Toward Approaches to Promote Child Well-being in Policy and Practice. Acad Pediatrics. 2017;17(7):S51–S69. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.04.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Testa A, Jackson DB, Ganson KT, Nagata JM. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Criminal Justice Contact in Adulthood. Acad Pediatr. Published online November 6, 2021:S1876-2859(21)00532-5. 10.1016/j.acap.2021.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Faith MS, Butryn M, Wadden TA, Fabricatore A, Nguyen AM, Heymsfield SB. Evidence for prospective associations among depression and obesity in population-based studies. Obesity Rev. 2011;12(5):e438–e453. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health. Published online 2011. Accessed March 18, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44499

- 38.Zhang J, Bray BC, Zhang M, Lanza ST. Personality profiles and frequent heavy drinking in young adulthood. Personal Indiv Diff. 2015;80:18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity Analysis in Observational Research: Introducing the E-Value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268. doi: 10.7326/M16-2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.VanderWeele TJ, Arah OA. Bias Formulas for Sensitivity Analysis of Unmeasured Confounding for General Outcomes, Treatments, and Confounders. Epidemiol. 2011;22(1):42–52. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181f74493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andridge RR, Little RJA. A Review of Hot Deck Imputation for Survey Non-response. Int Stat Rev. 2010;78(1):40–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-5823.2010.00103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple Imputation for Interval Estimation From Simple Random Samples With Ignorable Nonresponse. J Am Stat Assoc. 1986;81(394):366–374. doi: 10.2307/2289225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andrade C. Mean Difference, Standardized Mean Difference (SMD), and Their Use in Meta-Analysis: As Simple as It Gets. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(5):20f13681. 10.4088/JCP.20f13681 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Massoglia M. Incarceration as Exposure: The Prison, Infectious Disease, and Other Stress-Related Illnesses. J Health Soc Behav. 2008;49(1):56–71. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim Y. The Effect of Incarceration on Midlife Health: A Life-Course Approach. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2015;34(6):827–849. doi: 10.1007/s11113-015-9365-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith M, Udo T. The Relationship Between Age at Incarceration and Lifetime Suicide Attempt Among a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Adults. Community Ment Health J. Published online March 5, 2022. 10.1007/s10597-022-00952-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Zhao Q, Afkinich JL, Valdez A. Incarceration History and Depressive Symptoms Among Women Released from US Correctional Facilities: Does Timing, Duration, or Frequency Matter? Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2021;19(2):314–326. doi: 10.1007/s11469-019-00058-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Research Council. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. (Travis J, Western B, Redburn S, eds.). The National Academies Press; 2014. 10.17226/18613

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 158 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analyzed during the current study was generated primarily from the online database of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 which is publicly available at no cost at https://www.nlsinfo.org/investigator. However, in order to properly adjust our variance/uncertainty estimates for NLSY79’s complex sample design, our analytic dataset also included restricted access geocoded data (https://www.bls.gov/nls/request-restricted-data/nlsy-geocode-data.htm) about participants’ sampling strata and primary sampling units (or clusters). Statistical programming code and a non-restricted version of this study’s analytic dataset (containing only the publicly available data but not the restricted access data) are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.