Abstract

Functional Dyspepsia (FD), commonly called chronic indigestion, comes under the umbrella of 'Disorders of Gut–Brain Axis'. It manifests as a cluster of upper gastrointestinal symptoms including epigastric pain or burning, postprandial fullness and early satiety. Since the pathophysiology is complex, it is often difficult to effectively manage and significantly impacts the patient's quality of life. This case series aims to elucidate the role of Yoga as an adjuvant therapy to modern medicine in providing relief of dyspeptic symptoms in such patients. Yoga is an ancient Indian mind-body practise that has the potential to be used for various brain-gut disorders. Apart from treating the gut disorders from top down (mind-gut) pathway, it may have more direct physiological effects as well. Researches on IBS and one research on abdominal pain related FGID have shown Yoga therapy to be effective in ameliorating the symptoms.

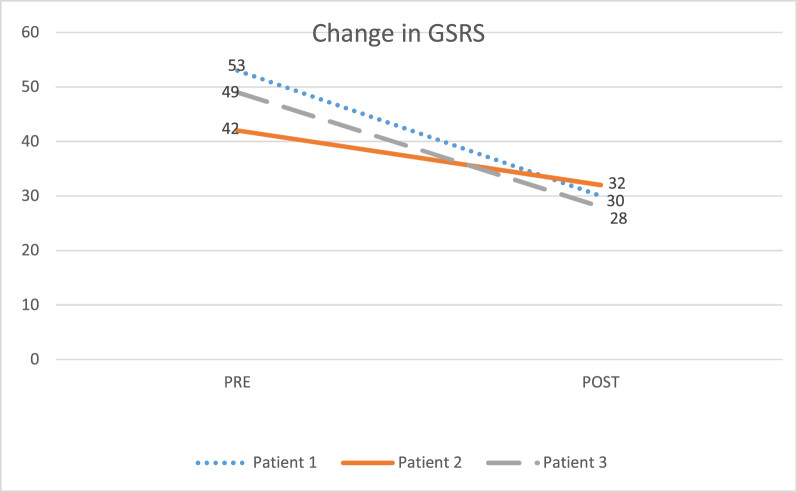

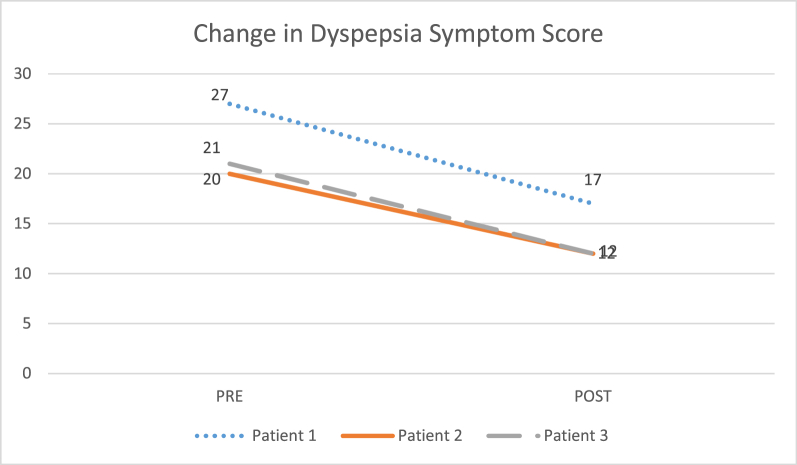

In this study, we present three such cases (1 male and 2 female) having a clinical diagnosis of FD in detail. These patients were initially non-responsive to medications but later showed remarkable improvement in symptoms within one month of added Yoga therapy intervention. This study was conducted as a part of a larger study conducted at a tertiary hospital in Pondicherry in collaboration between its Yoga department and Medical Gastroenterology Department. Yoga therapy protocol was given along with their regular medical management for a month. Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) and Dyspepsia Symptom Score questionnaires were used to assess symptoms before and after the intervention period. All three patients showed marked reductions in symptom scores both in the GSRS and Dyspepsia Questionnaire. The present case series suggests effect of adjuvant Yoga therapy in reducing symptoms of functional dyspepsia. Future studies may clarify the psycho-physiological basis of the same.

Keywords: Functional dyspepsia, Case-series, Yoga therapy, Shatkriya, Brain–gut axis

1. Introduction

Functional Dyspepsia (FD), commonly known as, chronic indigestion is an upper gastrointestinal disorder that consists of a cluster of symptoms including epigastric pain or burning, postprandial fullness and early satiety without any organic or structural cause. Associated complaints may include bloating, belching, nausea, vomiting etc. Rome- IV further categorizes FD into broadly two categories: (i) Epigastric Pain Syndrome (EPS) which includes the presence of bothersome epigastric pain or/and burning, at least once a week for 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior. (ii) Postprandial Distress Syndrome (PDS) which includes bothersome fullness after meals or/and early satiety present at least 2–3 days a week for 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior [1,2].

Estimated prevalence of FD in the Rome Foundation global survey, as per Rome IV criteria in the general population stands at 7.2% [3]. In India prevalence of uninvestigated dyspepsia (UD) is estimated between 7.5% and 49% differing across various states [4]. Female gender, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, smoking [5], psychological distress [6,7] and acute gastroenteritis infection [8] are some of the risk factors for development of FD later. Although, western studies have reported an association between lower socioeconomic status and FD, studies conducted in rural and urban South-east Asia reported a lower prevalence among rural adults of lower socioeconomic status [5,9].

The pathophysiology is complex and is attributed to disordered communication between the gut and the brain leading to motility disturbances, visceral hypersensitivity, altered mucosal and immune function, altered gut microbiota and altered central nervous system (CNS) processing [2,10,11]. In a subset of FD patients, duodenal inflammation is also now implicated in the origin of symptoms [12]. Stress, acute infection or a food allergen may initiate an immune response in the duodenum, resulting in inflammation and cytokine release that triggers CRF release from the hypothalamus, which then may lead to altered sensory-motor gastro-duodenal disturbances. Studies have also found anxiety [6] and depression [13] to play an important causal role in the development of FD. However, in other cases, they may manifest after the gut symptoms [14]. Hence, Rome- IV has redefined Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (FGIDs) as “Disorders of Gut-brain Axis” [15].

Current medical management includes proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for EPS or H2 blockers if the PPI fails to control the symptoms. In PDS, a prokinetic is recommended. Second-line therapy includes tricyclic antidepressants in low doses. Helicobacter Pylori infection must be excluded as it requires specific treatment [11,16]. However, the efficacy of the treatment schedule remains modest and treatment of FD remains unsatisfactory for many patients [1,17,18]. Studies have shown PPI therapy to be effective only in a subset of people with ‘ulcer-like’ and ‘reflux-like’ dyspepsia and no advantage over ‘dysmotility-like’ dyspepsia [19] and its long term use is associated with side-effects like infectious diarrhoea, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) [20]. Prokinetics drugs prolong the QT interval [2]. Because of its chronicity in nature, FD impacts the QoL of patients [9], leads to psychological distress and incurs significant healthcare cost [21] Hence, there is a need to investigate additional interventions such as the role of adjuvant Yoga therapy that can be integrated with the medical treatment which can empower the individual to aid his/her healing.

Yoga therapy is a part of yoga and is defined by IAYT as, “the process of empowering individuals to progress toward improved health and well-being through the application of the teachings and practices of Yoga” [22]. Yoga is an ancient Indian mind-body practise which aim to control the fluctuations of mind. The word yoga is a Sanskrit term which is derived from the root word “yuj” meaning to unite the mind, body and soul [23]. It comprises of physical, mental and spiritual practices for achieving complete state of health and wellness. Role of Yoga in reducing stress, anxiety and depression is well established [[24], [25], [26]]. The calming and relaxing practices in yoga helps to balance the autonomic nervous system by enhancing the parasympathetic tone and decreasing the sympathetic tone [25,27]. Furthermore, yoga may have more direct physiological effects, affecting the peripheral systems directly. It is traditionally taught that Yoga practices such as shatkriya (cleansing practices), asana (postures) and pranayama (breathing practices) help in cleansing and rejuvenating the gut. Thus, yoga can play a bi-directional role in modulating the gut–brain axis. In this case series, we present three cases in detail who were earlier non-responsive to medications alone but showed remarkable improvement in symptoms with one month of adjuvant Yoga therapy intervention.

2. Patient information

In this case series, we are reporting three patients (1 M, 2 F) with a clinical diagnosis of FD who were willing to undergo the Yoga therapy protocol. This study was conducted as a part of a larger study conducted at a tertiary hospital in Pondicherry in collaboration between its Yoga department and Medical Gastroenterology Department. Ethical approval was obtained for the larger study from the Institutional Human Ethics Committee (IHEC) and registered with the Clinical Trials Registry of India, CTRI/2019/10/021,773 [Registered on: 23/10/2019]. The three cases presented here fulfilled the inclusion criteria [Symptoms as per Rome-IV criteria, no evidence of any structural or organic disease in endoscopy, age limit of 18–65 years and willingness to participate in Yoga Therapy] and exclusion criteria [Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), gastric carcinomas, hematemesis, hiatal hernia, congenital malformations, liver disease, history of recent surgery within 6 months, heart disease, hypertension, epilepsy, bleeding piles].

2.1. Case – 1

A 33-year-old male presented with complaints of pain and burning sensation in the upper abdominal region at the Medical Gastroenterology clinic. He complained of fullness and bloating every day, after eating and nausea while brushing in the morning on some days. He reported his symptoms started two years back. He was given omeprazole 20 mg twice daily which he took for 2 months and found relief in symptoms. However, his symptoms reappeared after six months and he was tested H. Pylori positive. He finished the triple therapy course for the same but showed little relief. Since then he was on a combination drug containing Omeprazole and Domperidone on and off. However, he felt only mild symptomatic relief in symptoms with medications and the symptoms would reappear after stopping the medication. He also reported increased stool frequency since one month and passed 4-5 stools/day. There was no relief in dyspeptic symptoms with the passing of stools. He was suggested to have an endoscopy and the report revealed Corpus Gastritis. A biopsy was taken for H. Pylori testing with negative result. He was diagnosed as having FD and prescribed Pantoprazole 40 mg once daily and referred to Yoga therapy. Following written informed consent, yoga therapy was administered to him.

2.2. Case - 2

A 19-year female presented at the gastroenterology clinic, with abdominal and retrosternal burning sensation. Her complaint started a year back for which she was given pantoprazole at that time for 8 weeks, after which she took it on & off, with little to no relief. She was on medications on and off for the same, with little to no relief. She also reported bloating after food and regurgitation since six months. Her endoscopy was done and revealed normal study. She was diagnosed as having FD by the gastroenterologist and prescribed Esomeprazole 40 mg once daily and a combination syrup of omeprazole and domperidone 5 ml for 15 days. She was referred to the Yoga therapy clinic. She reported that symptom onset started after admission into college and shifting to a local accommodation which resulted in change of food. She also felt stressed with the new environment and pressure of her studies. Yoga therapy was started for her along with medications.

2.3. Case – 3

A 48-year-old female presented with typical dyspeptic symptom of pain in the upper abdominal region. The pain was of dull aching nature. She also reported abdominal burning since 5 years that decreases with food intake. She was on medications (on and off) giving only mild symptomatic relief. She reported bloating on intake of spicy food, decreased appetite and early satiety. She had started experiencing difficulty in passing stools since past one month. Her endoscopy report revealed Corpal and Antral Gastritis. She was diagnosed as FD and put on a Pantaprazole 40 mg once a day and Domperidone 10 mg twice a day along with a laxative syrup containing Sodium picosulfate, liquid paraffin, and milk of magnesia for her constipation twice a day. When she came for yoga therapy, the patient revealed she was anxious and stressed because of being away from her son. Following written informed consent, yoga practices were started for her. A brief timeline of the occurrence of symptoms, diagnosis, and commencement of Yoga therapy for all three patients is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Timeline of events for the participants.

| Health Event | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Occurrence of first symptom | June 2017 | August 2018 | April 2014 |

| Visit to Medical Gastroenterology clinic | July 15, 2019 | August 2, 2019 | August 19, 2019 |

| Endoscopy/Diagnosis of FD | July 16, 2019 | August 5, 2019 | August 20, 2019 |

| Medications & Start of Yoga Therapy | July 16, 2019 | August 5, 2019 | August 21, 2019 |

| [Practices of 1st week were given (Refer to Table 3)] | |||

| Follow up at 2nd week | July 22, 2019 (Symptom frequency reduced) | August 12, 2019 (Burning sensation reduced) | August 29, 2019 (Patient reported little relief in overall symptoms) |

| [Practices of 2 nd week were given (Refer to Table 3)] | |||

| Follow up at 3rd week | July 29, 2019 (epigastric pain and burning sensation reduced) | August 19, 2019 (No further improvement) | September 4, 2019 (Significant relief in burning sensation, improvement in appetite) |

| [Practices of 3rd week were given (Refer to Table 3)] | |||

| Follow up at the beginning of 4th week | August 5, 2019 (No further improvement) | August 27, 2019 (No regurgitation, significantly reduced burning) | September 11, 2019 (Relief in epigastric pain; bloating however persisted; same 3rd week practices were given) |

| [Practices of 4th week were given (Refer to Table 3)] | |||

| Final follow up at the end of 30 days | August 16, 2019 (Bloating sensation reduced significantly, it was present only after morning meal but normal during the rest of the day) | September 4, 2019 (All symptoms including bloating reduced significantly) | September 20, 2019 (Decrease in bloating sensation after food but general heaviness persisted) |

For weekly details of Yoga practices, refer to Table 3.

3. Clinical findings

Diagnosis of FD was confirmed by the gastroenterologist with the help of endoscopy to rule out any organic or structural causes. The endoscopy report for the three patients revealed corpus gastritis, normal study, and corpal and antral gastritis respectively. A biopsy too was taken for H. Pylori testing for Case-1 with negative result.

4. Diagnostic assessment

The above mentioned clinical findings were used only as diagnostic criteria to confirm the diagnosis of FD. Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) [28] and Dyspepsia Symptom Score Questionnaire [29] were used to assess the symptoms of FD. The patients had to rate their symptoms in the previous week on a scale of 1–7 in GSRS, where 1 represents absence of troublesome symptoms and 7 represents very troublesome symptoms. Similarly they had to rate their symptoms on a scale of 1–4 taking into account the frequency and intensity of symptoms in the previous two weeks in dyspepsia questionnaire: 1 - if the symptom did not bother at all or only infrequently; 2 - if it bothered only a little; 3 - if it bothered moderately; and 4 - if it bothered a lot. Sum of all symptom scores was assessed to obtain the total symptom score. Baseline and post assessments were taken before and after one month of adjuvant Yoga therapy. Patients were to continue their medical management along with yoga practices taught to them.

5. Therapeutic intervention

Following informed consent and baseline assessments, yoga therapy was administered five days a week (two supervised sessions and three home practice sessions). Pre-recorded yoga videos were given to facilitate practice at home. The detailed procedure of the techniques in the yoga therapy protocol are given in Table 2. A step-by-step, graded approach was adopted and components of the yoga therapy protocol were added to the practice sessions every week based on the progress of the participant, details of which are given in Table 3. The practices selected in the protocol are based on traditional texts that detail their efficacy in handling digestive disorders [30].

Table 2.

List of practices in Yoga Therapy Protocol.

| S.No. | Yoga Technique | Procedure (Ref.: APMB [23]) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Vibhaga Pranayama (Yogic Deep Breathing) | Sit comfortably in Sukhasana (cross legged position)/Ardha Padmasana (half-lotus pose) or lie in Shavasana (corpse pose) and relax the whole body. Inhale slowly and deeply, allowing the abdomen to expand fully. At the end of abdominal expansion, start to expand the chest outward and upward. This completes one inhalation. Now start to exhale. First, relax the chest and in the end draw the abdomen inward. This completes one round of yogic breathing. |

| (i) Madhyam Pranayama (Chest breathing) | Sit in a meditation posture or lie in shavasana and relax the whole body. Begin to inhale by slowly expanding the ribcage. Expand the chest as much as possible. Exhale by relaxing the chest muscles. This completes one round. Continue thoracic breathing for a few minutes. | |

| (ii) Adham Pranayama (Abdominal Breathing) | Sit in a meditation posture or lie in shavasana and relax the whole body. Inhale while expanding the abdomen as much as is comfortable. On exhalation, the abdomen moves inward. | |

| 2. | Nadi Shuddhi (alternate nostril breathing) | Sit in a comfortable position. Eyes closed gently. Adopt nasagra mudra (nosetip position) with the right hand and place the left hand on the knee in chin or jnana mudra. Close the right nostril with the right thumb. Gently inhale through left nostril as deep and as long you can without straining or any sound. After the end of inhalation, close your left nostril, open your right nostril and gently exhale through the right nostril. At the end of exhalation, inhale through the right nostril. Then close the right nostril gently exhale through the left nostril. This is one round. |

| 3. | Vatasara (air swallowing) | Sit comfortably. Close your eyes. Purse the lips, forming a beak called Kaki Mudra, through which air may be inhaled. Inhale slowly and deeply through the pursed lips as much as you can, completely filling air into the gut up till the throat. If you can't inhale in one go, take air in small–small sips and fill up till the throat. At the end of inhalation close the lips and exhale slowly through the nose. This is one round. |

| Vatasara with holding | With practise, after inhalation, hold the air inside for as long as you are comfortable. Then exhale gently through nose. | |

| 4. | Laghoo Shankh Prakshalana (short intestinal wash) | Prepare two litres of warm saline water. Sit and drink 2 glasses of the prepared water. Perform the 5 asanas 8 times each: a) Tadasana, b) Tiryaka tadasana, c) Kati chakrasana, d) Tiryaka bhujangasana, e) Udarakarshanasana. After completing, again drink 2 glasses of water and repeat the asanas 8 times each. Repeat the process for a third and last time. Go to the toilet, but do not strain, whether there is a bowel movement or not. If there is no motion immediately, it will come later on. |

| 5. | Kapalabhati (frontal brain cleansing) | Sit in a comfortable meditation asana. The head and spine should be straight with the hands resting on the knees in either chin or jnana mudra. Close the eyes and relax the whole body. Exhale through both nostrils with a mild forced contraction of the abdominal muscles. The following inhalation should be passive by allowing the abdominal muscles to relax. After completing 10–20 strokes. Relax. Allow the breath to return to normal. This is one round. |

| 6. | Agnisara (activating the digestive fire) | Sit in ardhapadmasana. Inhale deeply and then exhale completely as much as possible contracting the abdomen. Lean forward slightly. Push down on the knees with the hands and perform chin lock. With the breath held outside, move the abdominal muscles in and out, for as long as it is possible to hold the breath outside comfortably. Do not strain. When you can't hold, release chin lock and inhale. This is one round. Relax until the breathing normalizes. |

| 7. | Suryanamaskar (Sun Salutation) |

Pranamasana (Prayer pose) - Stand upright with the feet together. Slowly bend the elbows and place the palms together in front of the chest in namaskara mudra. Hasta Uttanasana (Raised Arms pose) - Separate the hands, raise and stretch both arms above the head, keeping them shoulder width apart. Bend the head, arms and upper trunk slightly backward. Padahastasana (hand to foot pose) - Bend forward from the hips as much as you are comfortable. If possible touch the fingers or palms of the hands on either side of the feet. Do not strain. Keep the knees straight. Ashwa Sanchalanasana (equestrian pose) - Place the hands on the floor (bend the knees if required) beside the feet. Stretch the right leg back as far as is comfortable. Santolasana (plank pose) - Take the left leg back and place it by the side of the right leg. Balance on both the hands and foot. Keep the back straight and straighten the knees, buttocks should neither sink, nor lifted up. The arms should be straight. Ashtanga Namaskara (salute with eight parts or points)- Keep the hands and feet in place. Lower the knees, chest and chin to the floor. The buttocks and abdomen should be raised. Bhujangasana (cobra pose) – Flatten the toes. Push the hands on the floor and slide the chest forward. Raise first the head, then shoulders, and then arch the back into the cobra pose. Parvatasana (mountain pose)- From bhujangasana, raise the buttocks and knees and lower the heels to the floor forming a mountain. Keep the back, arms and legs straight. Ashwa Sanchalanasana (equestrian pose) - From parvatasana, inhale and bring your right foot forward in between your hands. Keep the left leg straight and look up. Padahastasana (hand to foot pose) - Bring the left foot forward next to the right foot. Straighten both legs. With torso folded forward without straining with or without hands touching the floor. Shift the weight little forward on the toes to make the legs perpendicular to the ground. Hasta Uttanasana (raised arms pose) – Inhale and raise the torso up. Stretch the arms above the head. Keeping the arms shoulder width apart, bend the head, arms and upper trunk backward slightly. Pranamasana (prayer pose) - Bring the palms together in front of the chest. |

| 8. | Shitali (cooling breath) | Sit in a comfortable posture. Close the eyes and relax the whole body. Extend the tongue outside the mouth. Roll the sides of the tongue up, so that it forms a tube. Inhale slowly through the rolled tongue as deep as you can. At the end of the inhalation, draw the tongue in, close the mouth and exhale through the nose. A feeling of coolness will be experienced on the tongue and the roof of the mouth. This is one round. |

| 9. | Shitkari (hissing breath) | Sit in a comfortable posture. Close the eyes and relax the whole body. Hold the teeth lightly together. Separate the lips, exposing the teeth. Inhale slowly and deeply through the teeth. At the end of the inhalation, close the mouth. Exhale slowly through the nose in a controlled manner. This is one round. |

| 10. | Shavasana (corpse pose) | Lie flat on the back with the arms few inches away from the body, palms facing upward. A thin pillow or folded cloth may be placed below the head. Move the feet slightly apart and close the eyes. Keep the body in a straight line and relax. Become aware of the natural breath and allow it to become relaxed. After some time, again become aware of the body and surroundings, and gently release the posture. |

| 11. | Om Chanting | Sit in a comfortable posture. Close your eyes. Inhale slowly and when ready to exhale, chant A-U-M slowly and steadily. |

Table 3.

Weekly yoga therapy protocol.

| S.No. | Practices | Duration/Repetitions |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | ||

| 1 | Yogic Deep Breathing | 3 rounds | 5 rounds | 5 rounds | 5 rounds |

| (i) Chest breathing | 5 rounds | – | – | – | |

| (ii) Abdominal Breathing | 5 rounds | – | – | – | |

| 2 | Nadi Shuddhi | 3 rounds | 6 rounds | 9 rounds | 9 rounds |

| 3 | Vatasara | 5-10 rounds | 10 rounds | 5 rounds | 5 rounds |

| Vatasara with holding | – | – | 5 rounds | 5 rounds | |

| 4 | Laghoo Shankh Prakshalana | – | Twice a week | Once a week | Once a week |

| 5 | Kapalabhati | – | – | 2 rounds (20–30 strokes each) Once a week |

2 rounds (20–30 strokes each) Once a week |

| 6 | Agnisara | – | – | – | 2 rounds (10–20 strokes each) Once a week |

| 7 | Suryanamaskar | – | – | 2 rounds | 2 rounds |

| 8 | Shitali | 5 rounds | 5 rounds | 5 rounds | 5 rounds |

| 9 | Shitkari | 5 rounds | 5 rounds | 5 rounds | 5 rounds |

| 10 | Shavasana | 5 min | 5 min | 5 min | 5 min |

| 11 | Om Chanting | 3 times | 3 times | 3 times | 3 times |

6. Follow up & outcomes

Patients were followed up every week. Case −1 after five days reported decreased stool frequency to one stool per day. After 15 days, his epigastric pain and burning sensation reduced but the bloating after food persisted. At the end of the month, the bloating sensation was present only after the morning meal as reported by the patient and was normal during the rest of the day. After the completion of one month, post-assessments were taken. Case −2 found some relief in burning sensation after 1st week; however, bloating persisted. By the end of 3rd week, there was relief in regurgitation (completely absent in the last 10 days) and burning (present in 2 out of 10 days). The bloating sensation also reduced significantly at the end of the month. Case −3, after two weeks of Yoga practise, reported relief in burning sensation as well as improvement in appetite. She would pass stool with medication but the bloating sensation persisted. Complete yoga protocol could not be finished for her within a month because of slow progress. By the end of the month, there was a decrease in bloating sensation after food but the general heaviness persisted. She was advised to continue the practices to attain further benefit. After the completion of one month, post-assessments were taken. All three patients showed improvement in their symptom scores. The pre and post-scores on GSRS and dyspepsia symptom questionnaire are given in Table 4 and shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Change in symptom scores.

| Patient | GSRS |

Percentage decrease |

Dyspepsia Symptom Score |

Percentage decrease |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRE | POST | % | PRE | POST | % | |

| Patient 1 | 53 | 30 | 43.39% | 27 | 17 | 37.03% |

| Patient 2 | 42 | 32 | 23.80% | 20 | 12 | 40.00% |

| Patient 3 | 49 | 28 | 42.85% | 21 | 12 | 42.85% |

Fig. 1.

Graph showing change in GSRS scores of the three subjects.

Fig. 2.

Change in Dyspepsia Symptom Score of the three subjects.

7. Discussion

7.1. Limitations

Because of the absence of control group, these results only provide preliminary findings and hence cannot be generalized to the whole population. We recommend further studies be done with a larger sample size to provide the next levels of evidence. Also adding tools to measure mental health status such as stress, anxiety and depression would help in a better understanding of the bi-directional interplay of the gut–brain axis in alleviation of GI symptoms.

7.2. Strengths

Most of the earlier research in this field has been done on patients with irritable bowel syndrome and to the best of our knowledge, the present study is a novel attempt to highlight the role of Yoga therapy as an adjuvant in FD. One study [31] that used yoga therapy on abdominal pain related FGID in children, included few FD cases as well (11.6%). In this study Yoga was more effective in reducing pain intensity and monthly school absence but was not significantly more effective in improving pain frequency or QoL when compared to standard medical care. However, the relief in pain in FD cases separately is not known.

Treatment of FD has remained a challenge due to varied causes that has no proven cause–effect relationship and hence lack of targeted treatment. Our present study indicates that adjuvant Yoga Therapy in patients with FD can play an important role in reducing symptoms. Yoga therapy has already shown its efficacy in Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), in reducing symptom severity score, gastric motility, autonomic and somatic symptom scores as well as depression, anxiety, gastrointestinal-specific anxiety, and quality of life [32,33].

One probable mechanism by which Yoga therapy seems to work in FD patients is enhancing the vagus nerve tone and parasympathetic tone. Impaired vagal tone has been implicated in a subset of FD patients [34]. Yoga has been hypothesised to work in part by enhancing the vagus nerve tone and hence parasympathetic tone [35]. In a study done by Udupa et al. Pranayama training involving nadishuddhi, mukh-bhastrika, pranava and savitri pranayama for 20 min daily for a duration of 3 months increased parasympathetic tone [36]. In another study Sudarshan Kriya Yoga for 4 weeks enhanced parasympathetic activity and vagal tone [37]. Further, yoga works centrally to inhibit pain by increasing GABA levels in thalamus [35], thus can help in pain like symptoms in FD. Duodenal inflammation is now considered an important factor in developing FD symptoms and levels of inflammatory cytokines are found to be increased in FD [12]. Researches have shown that yoga helps in reduction of inflammatory cytokines like IL 6, TNF- alpha [38] as well reduced expression of pro-inflammatory genes [39].

Further, the practices in our study have been specifically selected which can play a bi-directional role in modulating gut–brain axis. Practices like Vatasara, Laghoo shankh Prakshalana, Agnisara can directly influence the gut. Vatasara that involves swallowing air through the mouth helps in lowering acidity as per a research conducted by Gharote [40], thus directly affecting the gut. Laghoo Shankh Prakshalana (LSP) that involves performing set of asanas after drinking warm saline water and finally passing it in the bowels stimulates peristalsis of intestines. It aids in reducing ailments of the digestive system like constipation, biliousness, indigestion and chronic gastritis [41]. The probable mechanism by which LSP works in FD seems multi-faceted. It may work by increasing gastric motility [42] as well as alleivate the hypersensitivity of the stomach to acid. Also gut microbiota dysbiosis which is now considered an important factor in developing FD symptoms, LSP with its gut cleansing action may be helpful in eliminating harmful bacteria and restoring the gut dysbiosis. However, researches are needed to substantiate these mechanisms. Researches till date on LSP shows it effective in bowel health, spinal felxibility, low back pain and anxiety [42,43]. In a recent study on Agnisara, it was found in 12 subjects that properly performed agnisara improved the blood flow to splanchic region which may lead to improved digestive function [44].

On the other hand, relaxative practices in the protocol like deep breathing, nadi shuddhi, Om Chanting influence the autonomic balance and address psychological states like stress, anxiety and depression [25,27,[45], [46], [47]]. Turankar et al. in their study reported anuloma viloma to bring about a parasympathetic shift in the autonomic functions within a short span of one week [48]. Studies on ‘Om’ chanting have demonstrated increased parasympathetic nervous activity and physiologic relaxation [49,50].

Other practices like Suryanamaskar, Kapalabhati have both physiological as well as psychological benefits. The practice of Suryanamaskar in an RCT study done on highly stressed college students suggested Suryanamaskar as an effective relaxation strategy. It lead to physical relaxation, mental quiet, ease/peace, rested and refreshed, strength, awareness and joy. Suryanamaskar group was lower on the stress dispositions like somatic stress, worry, and negative emotion compared with the control group [51]. In another comparative study [52] on slow and fast Suryanamaskar, practise of slow Suryanamaskar led to a reduction in heart rate and diastolic blood pressure indicating a shift towards parasympathetic nervous system. Kapalabhati, even though shows parasympathetic withdrawal during the practise, Malhotra et al. in their study observed parasympathetic activation after kapalabhati. Due to expulsion of body carbon dioxide, it gives a feeling of joy and stillness in the practitioners [53].

All these studies on the various yogic techniques demonstrate the possible mechanisms with which these may have been useful in our study. Our results demonstrate a significant improvement in symptoms of patients with FD which needs to be further substantiated with a larger sample size and control group over a longer period.

8. Conclusion

The present case series suggests role of adjuvant Yoga therapy in reducing symptoms of functional dyspepsia such as bloating, burning sensation and post prandial fullness. Additionally, an improvement in appetite as well as relief from regurgitation were noted. Future studies may elaborate the psycho-physiological basis of the same.

9. Patient perspective

All the three patients reported feeling happy, calm and relaxed after Yoga therapy sessions. At the end of intervention period, they were satisfied with the outcomes and felt that yoga module was helpful in managing their condition. Case – 1 reported “All my symptoms have significantly reduced and I feel so much better and confident now that my symptoms will fully disappear, which I thought may never go away”. Case −2 mentioned great relief in symptoms but inability to practice consistently because of pressure of studies and exams. According to Case- 3, “My appetite is restored now and I will continue Yoga for further benefit”.

10. Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all the three participants before administering Yoga therapy and data collection.

Source of funding

This study was supported by the UGC-NET Junior Research Fellowship granted to the first author.

Author contributions

GS – Conceptualization, Methodology/Study Design, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing original draft, review and editing, visualisation, funding acquisition. MR – Writing- Review and editing, formal analysis, resources, visualisation, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. ABB - Methodology/Study Design, Writing original draft, review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. SMP - Conceptualization, Methodology/Study Design, Investigation, resources, supervision. BV – Resources, review and editing, supervision. AK – Conceptualization, resources, review and editing, supervision, project administration.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the management and administration of Sri Balaji Vidyapeeth for all their support. Our gratitude to the nurses at the Medical gastroenterology department and the endoscopy unit for their support in patient recruitment. We would also like to thank Mr. G Dayanidy, Assistant Professor, ISCM for all the technical help and support in publishing the article. This study was supported by the UGC-NET Junior Research Fellowship Ref. No. 3930/(NET-DEC 2018) granted to the first author, hence we would like to extend our gratitude to the University Grants Commission for providing the funding to assist the study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Transdisciplinary University, Bangalore.

References

- 1.Harer K.N., Hasler W.L. Functional dyspepsia: a review of the symptoms, evaluation, and treatment options. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;16:66–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford A.C., Mahadeva S., Carbone M.F., Lacy B.E., Talley N.J. Functional dyspepsia. Lancet. 2020;396:1689–1702. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30469-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sperber A.D., Bangdiwala S.I., Drossman D.A., Ghoshal U.C., Simren M., Tack J., et al. Worldwide prevalence and burden of functional gastrointestinal disorders, results of Rome foundation global study. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:99–114. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.014. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghoshal U.C., Singh R. Functional dyspepsia: the Indian scenario. J Assoc Phys India. 2012;60(Suppl):6–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford A.C., Marwaha A., Sood R., Moayyedi P. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, uninvestigated dyspepsia: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2015;64:1049–1057. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aro P., Talley N.J., Ronkainen J., Storskrubb T., Vieth M., Johansson S.-E., et al. Anxiety is associated with uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia (Rome III criteria) in a Swedish population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:94–100. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones M.P., Tack J., Van Oudenhove L., Walker M.M., Holtmann G., Koloski N.A., et al. Mood and anxiety disorders precede development of functional gastrointestinal disorders in patients but not in the population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1014–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.12.032. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Futagami S., Itoh T., Sakamoto C. Systematic review with meta-analysis: post-infectious functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:177–188. doi: 10.1111/apt.13006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahadeva S., Yadav H., Rampal S., Everett S.M., Goh K.-L. Ethnic variation, epidemiological factors and quality of life impairment associated with dyspepsia in urban Malaysia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:1141–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanheel H., Carbone F., Valvekens L., Simren M., Tornblom H., Vanuytsel T., et al. Pathophysiological abnormalities in functional dyspepsia subgroups according to the Rome III criteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:132–140. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talley N.J. Functional dyspepsia: new insights into pathogenesis and therapy. Korean J Intern Med (Engl Ed) 2016;31:444–456. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2016.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enck P., Azpiroz F., Boeckxstaens G., Elsenbruch S., Feinle-Bisset C., Holtmann G., et al. Functional dyspepsia. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mak A.D.P., Wu J.C.Y., Chan Y., Chan F.K.L., Sung J.J.Y., Lee S. Dyspepsia is strongly associated with major depression and generalised anxiety disorder - a community study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:800–810. doi: 10.1111/apt.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koloski N.A., Jones M., Walker M.M., Holtmann G., Talley N.J. Functional dyspepsia is associated with lower exercise levels: a population-based study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:577–583. doi: 10.1177/2050640620916680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.What's New for Rome IV. Rome Foundation n.d. https://theromefoundation.org/romeiv/whats-new-for-rome-iv/(accessed December 13, 2021).

- 16.Madisch A., Andresen V., Enck P., Labenz J., Frieling T., Schemann M. The diagnosis and treatment of functional dyspepsia. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:222–232. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacy B.E., Talley N.J., Locke G.R., Bouras E.P., DiBaise J.K., El-Serag H.B., et al. Review article: current treatment options and management of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:3–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamawaki H., Futagami S., Wakabayashi M., Sakasegawa N., Agawa S., Higuchi K., et al. Management of functional dyspepsia: state of the art and emerging therapies. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2018;9:23–32. doi: 10.1177/2040622317725479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talley N.J., Meineche-Schmidt V., Paré P., Duckworth M., Räisänen P., Pap A., et al. Efficacy of omeprazole in functional dyspepsia: double-blind, randomized, placebocontrolled trials (the Bond and Opera studies) Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:1055–1065. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilhelm S.M., Rjater R.G., Kale-Pradhan P.B. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expet Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443–451. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2013.811206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahadeva S., Wee H.-L., Goh K.-L., Thumboo J. Quality of life in South east asian patients who consult for dyspepsia: validation of the short form nepean dyspepsia index. Health Qual Life Outcome. 2009;7:45. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Contemporary Definitions of Yoga Therapy - International Association of Yoga Therapists (IAYT) n.d. https://www.iayt.org/page/ContemporaryDefiniti (accessed December 5, 2022).

- 23.Saraswati S.S. 1997. Asana pranayama mudra bandha. Yoga publications trust. Revised & Enlarged edition (1 January 1997) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen K.W., Berger C.C., Manheimer E., Forde D., Magidson J., Dachman L., et al. Meditative therapies for reducing anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:545–562. doi: 10.1002/da.21964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pascoe M.C., Bauer I.E. A systematic review of randomised control trials on the effects of yoga on stress measures and mood. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;68:270–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li A.W., Goldsmith C.-A.W. The effects of yoga on anxiety and stress. Alternative Med Rev. 2012;17:21–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hepburn S.-J., Carroll A., McCuaig-Holcroft L. A complementary intervention to promote wellbeing and stress management for early career teachers. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2021;18:6320. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulich K.R., Madisch A., Pacini F., Piqué J.M., Regula J., Van Rensburg C.J., et al. Reliability and validity of the gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (GSRS) and quality of life in reflux and dyspepsia (QOLRAD) questionnaire in dyspepsia: a sixcountry study. Health Qual Life Outcome. 2008;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bisbal-Murrugarra O., León-Barúa R., Berendson-Seminario R., Biber-Poillevard M. A new questionnaire for the diagnosis of dyspepsia. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2002;32:25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhatt G.P., Sinh P., Chandra Vasu R.B.S. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.; 2004. The forceful yoga: being the translation of haṭhayoga-pradīpikā, gheraṇḍa-saṁhitā and siva-saṁhitā. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korterink J.J., Ockeloen L.E., Hilbink M., Benninga M.A., Deckers-Kocken J.M. Yoga therapy for abdominal pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders in children: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63:481–487. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D'Silva A., MacQueen G., Nasser Y., Taylor L.M., Vallance J.K., Raman M. Yoga as a therapy for irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:2503–2514. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05989-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taneja I., Deepak K.K., Poojary G., Acharya I.N., Pandey R.M., Sharma M.P. Yogic versus conventional treatment in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized control study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2004;29:19–33. doi: 10.1023/b:apbi.0000017861.60439.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holtmann G., Goebell H., Jockenhoevel F., Talley N.J. Altered vagal and intestinal mechanosensory function in chronic unexplained dyspepsia. Gut. 1998;42:501–506. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.4.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Streeter C.C., Gerbarg P.L., Saper R.B., Ciraulo D.A., Brown R.P. Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Udupa K., Madanmohan N., Bhavanani A.B., Vijayalakshmi P., Krishnamurthy N. Effect of pranayam training on cardiac function in normal young volunteers. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;47:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldstein M.R., Lewis G.F., Newman R., Brown J.M., Bobashev G., Kilpatrick L., et al. Improvements in well-being and vagal tone following a yogic breathing-based life skills workshop in young adults: two open-trial pilot studies. Int J Yoga. 2016;9:20–26. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.171718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Estevao C. The role of yoga in inflammatory markers. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2022;20 doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2022.100421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bower J.E., Irwin M.R. Mind-body therapies and control of inflammatory biology: a descriptive review. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;51:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gharote M.L. Effect of air swallowing on the gastric acidity: a pilot study. Yoga Mimamsa. 1971;14:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swathi P.S., Raghavendra B.R., Saoji A.A. Health and therapeutic benefits of Shatkarma: a narrative review of scientific studies. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2021;12:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kiran S., Sapkota S., Shetty P., Honnegowda T. Effect of yogic colon cleansing (laghu sankhaprakshalana kriya) on bowel health in normal individuals. Yoga Mimamsa. 2019;51:26. doi: 10.4103/ym.ym_4_19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haldavnekar R.V., Tekur P., Nagarathna R., Nagendra H.R. Effect of yogic colon cleansing (Laghu Sankhaprakshalana Kriya) on pain, spinal flexibility, disability and state anxiety in chronic low back pain. Int J Yoga. 2014;7:111–119. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.133884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Minvaleev R.S., Bogdanov R.R., Kuznetsov A.A., Bahner D.P., Levitov A.B. Yogic agnisara increases blood flow in the superior mesenteric artery. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2022;31:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2022.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhavanani A. Role of yoga in health and disease. Journal of Symptoms and Signs. 2014;3:399–406. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhavanani A. HRV as a research tool in yoga. Yoga Mimamsa. 2012;44:188–199. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Innes K.E., Bourguignon C., Taylor A.G. Risk indices associated with the insulin resistance syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and possible protection with yoga: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:491–519. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.6.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turankar A.V., Jain S., Patel S.B., Sinha S.R., Joshi A.D., Vallish B.N., et al. Effects of slow breathing exercise on cardiovascular functions, pulmonary functions & galvanic skin resistance in healthy human volunteers - a pilot study. Indian J Med Res. 2013;137:916–921. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Inbaraj G., Rao R.M., Ram A., Bayari S.K., Belur S., Prathyusha P.V., et al. Immediate effects of OM chanting on heart rate variability measures compared between experienced and inexperienced yoga practitioners. Int J Yoga. 2022;15:52. doi: 10.4103/ijoy.ijoy_141_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Telles S., Nagarathna R., Nagendra H.R. Autonomic changes during “OM” meditation. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;39:418–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Godse A.S., Shejwal B.R., Godse A.A. Effects of suryanamaskar on relaxation among college students with high stress in Pune, India. Int J Yoga. 2015;8:15–21. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.146049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhavanani A.B., Udupa K., Madanmohan Ravindra P. A comparative study of slow and fast suryanamaskar on physiological function. Int J Yoga. 2011;4:71–76. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.85489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Malhotra V., Javed D., Wakode S., Bharshankar R., Soni N., Porter P.K. Study of immediate neurological and autonomic changes during kapalbhati pranayama in yoga practitioners. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2022;11:720–727. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1662_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]