Abstract

Wound healing is a dynamic process that involves a series of molecular and cellular events aimed at replacing devitalized and missing cellular components and/or tissue layers. Recently, extracellular vesicles (EVs), naturally cell-secreted lipid membrane-bound vesicles laden with biological cargos including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, have drawn wide attention due to their ability to promote wound healing and tissue regeneration. However, current exploitation of EVs as therapeutic agents is limited by their low isolation yields and tedious isolation processes. To circumvent these challenges, bioinspired cell-derived nanovesicles (CDNs) that mimic EVs were obtained by shearing mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) through membranes with different pore sizes. Physical characterisations and high-throughput proteomics confirmed that MSC-CDNs mimicked MSC-EVs. Moreover, these MSC-CDNs were efficiently uptaken by human dermal fibroblasts and demonstrated a dose-dependent activation of MAPK signalling pathway, resulting in enhancement of cell proliferation, cell migration, secretion of growth factors and extracellular matrix proteins, which all promoted tissue regeneration. Of note, MSC-CDNs enhanced angiogenesis in human dermal microvascular endothelial cells in a 3D PEG-fibrin scaffold and animal model, accelerating wound healing in vitro and in vivo. These findings suggest that MSC-CDNs could replace both whole cells and EVs in promoting wound healing and tissue regeneration.

Key words: Extracellular vesicles, Cell-derived nanovesicles, Bionanotechnology, Mesenchymal stem cells, Fibroblasts, Cell proliferation, Cell migration, ECM, Wound healing

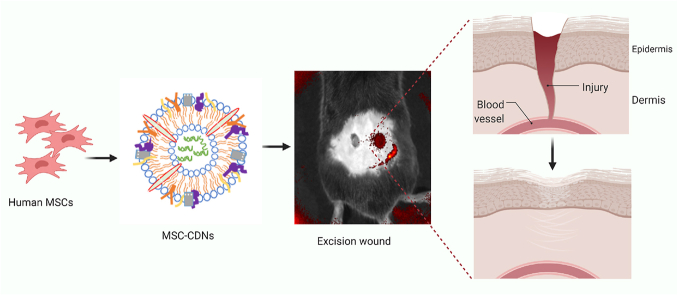

Graphical abstract

Cell-derived nanovesicles generated from mesenchymal stem cells mimic naturally cell-secreted Extracellular Vesicles and accelerate wound healing in-vitro and in-vivo.

1. Introduction

Wound healing is an intricate and dynamic response to injury, which involves the interaction of multiple components such as cells (platelets, macrophages, fibroblasts, epithelial and endothelial cells) and mediators like cytokine networks, chemokines, extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, growth factors (proteins and microRNAs), blood vessels, and nerves1. The cascade of wound recovery requires molecular and cellular events, including cell proliferation and migration, angiogenesis, ECM deposition, and tissue remodeling2. Unfortunately, chronic nonhealing wounds are associated with decreased cell proliferation and migration, reduced angiogenesis, impaired inflammatory response, and decreased production of growth factors and chemokines3. This complex process takes month to years for complete recovery of wounds and is often delayed in patients with underlying chronic conditions (e.g., diabetic skin ulcerations or extensive burns)4.

Cell therapy employs viable cells [e.g., MSCs, dendritic cells (DCs), embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)] to enhance wound healing and tissue regeneration through multiple cellular processes, such as cell proliferation and migration, angiogenesis and re-epithelization5, 6, 7. It has been reported that stem cells exert their therapeutic effects mainly via release of soluble factors that are responsible for paracrine signaling to promote endogenous repair and tissue regeneration3,5,8,9. However, cell therapy has been associated with several challenges such as immunogenicity, cell mutation/chromosome abnormality, and cell senescence10,11. In addition, technical challenges like invasive harvesting techniques, limited cell survival in vivo12, ethical concerns and legal restrictions13 have limited the translation of cell therapy into clinically relevant applications.

In the last few years, extracellular vesicles (EVs), which are naturally cell-secreted lipid-bound membrane vesicles found in all biological fluids14, 15, 16, 17, have gained much attention for their potential role in wound healing8,18, 19, 20, 21. EVs secreted by cells, particularly stem cells, have shown regenerative and/or tissue reparative effects. For instance, EVs produced from iPSC-derived MSCs resulted in accelerated re-epithelialization, reduced scar widths, promotion of collagen maturation and generation of newly formed vessels22. More importantly, EVs represent cell-free approaches as they are non-viable and work mainly via paracrine signaling, thus mitigating the challenges associated with cell-based therapy23. Nonetheless, several limitations need to be addressed before they can be extensively used as therapeutics, and these include long and tedious isolation processes, and low production yields. Indeed, the total amount of proteins present in the EVs secreted by DCs cultured for 24 h has been reported to be as low as ∼500 ng from 1 × 106 cells24.

Recently, CDNs have been developed as promising EV-mimetics, in view of their ability to preserve many cellular components from the parental cells (i.e., they mimic naturally secreted EVs in terms of size, morphology and structure) while shortening the production time by almost half and increasing the production yield by up to 100-fold25,26. As CDNs mimic EVs in terms of cell surface proteins, intracellular contents and lipids, these EV-mimetics are expected to have similar biological activity as previously reported for EVs26,27. Although CDNs have been produced in much higher yield and in shorter time compared to EVs, their biological cargos and intrinsic activity (i.e., therapeutic potential) have been poorly characterized.

On the basis of the previous reports on MSCs' and EVs' role in wound healing, in this study we hypothesized that MSC-CDNs as EV-mimetics could play a significant role in tissue repair. To test this hypothesis, MSC-CDNs produced using a cell shearing approach were fully characterized in terms of size, surface charge, nanovesicles’ concentration, and total proteins. In addition, high-throughput proteomics and gene ontology (GO) analysis were performed to identify the highly enriched proteins and their localization in MSC-CDNs and MSC-EVs. In order to assess their potential for tissue regeneration, MSC-CDNs were also examined for their ability to enhance proliferation and migration of human dermal fibroblasts (HDF) in vitro. Also, pro-angiogenic potency of MSC-CDNs was tested on human dermal microvascular endothelial (HDME) cells in a 3D PEG-fibrin scaffold. Lastly, the potential of MSC-CDNs to accelerate wound healing was tested in an in vivo excisional wound mouse model. Overall, our results confirm that the process of MSC-CDNs production is robust and reproducible, as it preserves both physical and biological characteristics of EVs. Moreover, for the first time ever reported, we demonstrated that these MSC-CDNs acted as EV-mimetics, by accelerating wound healing in vitro and in vivo at a similar rate as EVs and whole MSC cells used as controls, thus paving the way for promising, scalable regenerative approaches.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells

Human umbilical cord MSCs were purchased from PromoCell (Sickingenstraβe, Heidelberg, Germany) and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin medium in 0.2% w/v gelatin coated flask. Human dermal fibroblast (HDF) and human dermal microvascular endothelial (HDME) cells were purchased from PromoCell and grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin medium, and endothelial cell growth medium (ready-to-use, low serum) (C-22020, PromoCell), respectively. All cells were grown to 70%‒80% confluency before next passage and CDNs were produced from human umbilical cord MSCs before 10th passage.

2.2. Production of MSC-CDNs and isolation of MSC-EVs

MSC-CDNs were produced using spin cups via cell shearing approach as described previously28. Briefly, 7.5 × 106 MSC cells/mL were washed and resuspended in PBS before being centrifuged twice at 14,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C in a spin cup pre-fitted with 10 μm polycarbonate membrane (Merck Millipore, MA, USA). The flow through was then transferred to another spin cup fitted with 8 μm polycarbonate membrane (Merck Millipore, MA, USA) and spin down twice at 14,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The dispersion was purified using size-exclusion chromatography column packed with Sephadex G-50 (Sigma-Aldrich, Singapore) pre-equilibrated in PBS and the fractions with high protein content and appropriate hydrodynamic diameters were collected for further investigations.

EVs from MSCs (MSC-EVs) were isolated form the conditioned medium as described previously, with slight modifications27. The conditioned medium was centrifuged at 500×g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove cells and other debris. Then the supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000×g for 30 min at 4 °C to remove larger particles. The subsequent supernatant was then centrifuged at 200,000×g for 1.5 h at 4 °C in a Sorvall™ MTX150 micro-ultracentrifuge (ThermoScientific) fitted with S150-AT fixed angle rotor to pellet EVs. Next, the supernatant was discarded while the pellet was resuspended in PBS and centrifuged at 200,000×g for 1.5 h at 4 °C. The final supernatant was discarded while the pellet was resuspended in PBS.

2.3. Characterization of MSC-CDNs and MSC-EVs

The hydrodynamic diameter and the concentration of nanovesicles were determined using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) (Nanosight, NS300, Malvern instruments, UK) at a wavelength of 405 nm. The zeta potential of MSC-CDNs was measured based on electrophoretic mobility using a Zeta sizer (Malvern, Nano Series, Nano-ZS90, UK). The total amount of proteins present in the nanovesicles was quantified using Bicinchoninic Acid Assay (BCA) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Singapore) as per manufacturer's recommendations.

2.4. Cryo-TEM imaging

Morphology of MSC-CDNs was observed under Cryo-TEM imaging. For this, TEM grids (Lacey Formvar/Carbon, Ted Pella Inc. USA) were pre-treated for 3 min using a glow discharge equipment (HDT400, JEOL). 2 μL of the sample was loaded in the grid and was plunged into liquid ethane using a cryo-plunger 3 system (Cp3, Gatan). The samples were imaged using a TEM (JEOL2010, JEOL) set at 120 kV. Throughout the imaging process, the samples were maintained under cryogenic conditions using liquid nitrogen in a cryo-holder.

2.5. Proteomic analysis

2.5.1. In-trap digestion (S-trap)

MSC-CDNs or MSC-EVs (450 μg/mL dispersed in PBS) were subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen for 10 min and centrifuged at 17,000×g for 10 min at 25 °C. MSC-EVs were resuspended in lysis buffer (5% SDS, 50 mmol/L TEAB in water) after ultracentrifugation. Then MSC-CDNs sample was processed using the S-Trap mini column (Protifi, Farmingdale, NY, USA) and MSC-EVs sample was processed using S-Trap micro column (Protifi), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Eluted peptides were dried using a vacuum evaporator and reconstituted in 2% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC‒MS) analysis.

2.5.2. Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LCMS) analysis

For mass spectrometry analysis, sample was separated by Eksigent ChromXP (Framingham, MA, USA) C18-CL trap column (3 μm, 120 Å, 200 μm × 0.5 mm) and Eksigent ChromXP C18-CL analytical column (3 μm, 120 Å, 75 μm × 150 mm), while MSC-EVs sample was separated by Trajan ProteoCol C18P trap column (3 μm particle size, 120 Å, 300 μm i.d. × 10 mm) and Thermo Scientific Acclaim PepMap 100 C18 analytical column (3 μm particle size, 75 μm i.d. × 250 mm). Acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid was used as mobile phase at flow rate of 300 nL/min. An ionSpray voltage of 2200 V (for MSC-CDNs peptides) and 2300 V for MSC-EVs peptides was applied. MS–IDA (information-dependent acquisition) was performed where full MS (SCIEX TripleTOF 5600 system) scans (on positive mode) from 350 to 1250 m/z were acquired at the accumulation time of 250 ms, where maximum 50 precursors were selected for fragmentation at charge state 2‒5, intensity > 125 cps and dynamic exclusion for 15 s. Simultaneously, MS/MS parameters were in the scanning range of 100–1800 m/z with accumulation time of 50 ms at high sensitivity mode and at rolling collision energy.

2.5.3. Data analysis

The MSC-CDNs MS raw data were processed with ProteinPilot 5.0 (SCIEX) before using Mascot Server (version 2.7, Matrix Science, Boston, MA, USA) to search against the Human SwissProt Reference Proteome database (2019 Nov release, 20,352 entries), and spiked with common contaminant proteins (cRAP). Similarly, the MSC-EVs MS raw data were processed with ProteinPilot 5.03 (SCIEX) to search against the Human SwissProt Reference Proteome database (2022 Feb release, 20,361 entries), and spiked with cRAP. The protein (gene) lists obtained were subjected to gene ontology (GO) analysis to annotate cellular component (CC) (sub-cellular localization of proteins) and biological process (BP) enriched in the samples using Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID, Bioinformatics Resources version 6.8, NIH)29.

2.6. Cell uptake study via confocal microscopy

For cell uptake study, MSC-CDNs were labelled with cyanine-3-N-hydroxysuccinimide (Cy3-NHS) monoester (Lumiprobe) by adding the dye as per manufacturer instructions at pH 8 and incubating the mixture for 4 h on ice. The labelled MSC-CDNs were then returned to pH 7 and free dye was removed through overnight dialysis (10 kDa MWCO; ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in PBS, before being introduced to a Sephadex G50 size exclusion column equilibrated with PBS. 500 μL of fractions were collected and analyzed for protein content using a standard BCA protein assay kit and for fluorescence corresponding to excitation/emission of 550/570 nm.

2 × 104 HDF cells were cultured in 24-well plate (glass bottom) in 500 μL of cell culture medium for 24 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Then the cells were treated with 5 and 50 μg/mL of Cy3-labelled MSC-CDNs (Cy3-MSC-CDNs) for 1, 4 and 24 h before being washed with PBS twice. Then, hoechst 33342 dye and cellmask green were added to the HDF cells to stain nuclei and cell membrane, respectively. Cy3-MSC-CDNs treated HDF cells stained with hoechst 33342 dye and cellmask green were imaged using laser scanning confocal microscope (FluoView, FV1000 Olympus) and images were processed using Fluoview FV10ASW Version 4.2a software.

2.7. Cell proliferation assay

5 × 104 HDF cells were cultured in 12-well plate in 1 mL of cell culture medium for 24 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After 24 h, cells were treated with 5 and 50 μg/mL of MSC-CDNs for 24 and 72 h before being digested with trypsin. Then, the cells were stained with trypan blue and live cells were counted using automated cell counter (Invitrogen Countess 3, Waltham, MA, USA) and cell proliferation rate was calculated with respect to their initial cell number seeded.

2.8. Western blotting

2.5 × 105 HDF cells were cultured in a 6-well plate in 1.5 mL of cell culture medium for 24 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After 24 h, cells were treated with 5 and 50 μg/mL of MSC-CDNs for 24 h. Cytoplasmic and membrane proteins were extracted after cell lysis with RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and protein concentration was measured using BCA assay. Protein samples were mixed with sample buffer before being loaded in 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel followed by transferred to PVDF membrane (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk in 0.1% tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline (TBST) at RT for 1 h followed by reaction with primary antibody solution overnight at 4 °C. After washing, primary antibody was probed with secondary antibody at RT for 1 h, followed by development of signals using Bio-Rad Clarity Western ECL substrate. The protein bands were imaged using BioRad's ChemiDoc system. The following antibodies were used: anti-α-actin (ab68194, Boston, MA, USA), anti-rabbit HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA), anti-PCNA (Santa Cruz, sc-25280 HRP) and anti-Ki67 (Santa Cruz, sc-23900 HRP, Dallas, TX, USA).

2.9. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis

HDF cells grown and treated with MSC-CDNs as described in Section 2.8. They were washed with ice-cold PBS twice before the isolation of total mRNA using RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN), as per recommended protocol, and the concentration was measured using NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher). 125 ng of mRNA was used for cDNA conversion using QuantiTect-Reverse-Transcription Kit (QIAGEN). qPCR was then performed in triplicates with iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) in a real-time thermal cycler, QuantStudio 7 (ThermoFisher). GAPDH was used as the housekeeping gene and mRNA expression level was normalized to control. The following primers were used: TGF-β1: Forward TTCAGTCACCATAGCAACACTC, Reverse GAACTCCTCCCTTAACCTCTCT; VEGF-α: Forward CTCTCACCAGGAAAGACTGATAC, Reverse CAGAGTCTCCTCTTCCTTCATTT; GAPDH: Forward AGGGCTGCTTTTAACTCTGGT; Reverse CCCCACTTGATTTTGGAGGGA.

2.10. Measurement of p38 MAPK-α, VEGF-α and pro-collagen I-α 1 via ELISA kit

HDF cells were grown and treated with MSC-CDNs as reported in Section 2.8. Then p38 MAPK-α, VEGF-α and Pro-Collagen I-α 1 were measured using ELISA kit (ab221012, ab119566 and ab210966, respectively, Boston, MA, USA) as per manufacturer's recommended protocol. Briefly, 50 μL of sample was added to the pre-coated 96-well plate followed by addition of antibody cocktail (as recommended in protocol) and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Each plate was washed with buffer before the addition of 100 μL TMB development solution, followed by addition of 100 μL of stop solution. The optical density of each well was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

2.11. In vitro scratch closure assay

In vitro scratch closure (as a surrogate of wound healing) assay was performed as described previously30. Briefly, 5 × 104 HDF cells were cultured in 12-well plate in 1 mL of cell culture medium for 48 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After 48 h, cell monolayer was scraped with sterilized 1 mL micropipette tip and washed with PBS to remove detached cells and cell debris. Then the cells were treated with 5 and 50 μg/mL of MSC-CDNs, and the scratched area was imaged at different time intervals using Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope. Images were processed using ImageJ software and cell free area was calculated for each time point; the percentage of scratch closure (healing) against initial (0 h) wound gap at a particular time point was calculated according to Eq. (1):

| Scratch closure (%) = 100 × (IA‒FA)/IA | (1) |

where IA and FA denote the initial area at time 0 h and final area after different time intervals (12 h, 24 h and 36 h), respectively.

2.12. In vitro angiogenesis assay in a 3D PEG-fibrin scaffold

HDME and HDF cells were co-cultured in a 3D PEG-fibrin scaffold as described previously31. Briefly, fibrinogen from bovine plasma and polyethylene glycol-4-arm succinimidyl glutarate terminated were used to fabricate PEG-fibrin gel, which was prepared by mixing fibrinogen to PEG ratio of 40:1 w/w, making the final concentration of fibrinogen and PEG to 10 and 0.25 mg/mL, respectively. This mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min before being added with an optimized cell density in an appropriate volume of media in PEG-fibrinogen mixture. In parallel, human thrombin was used for the gelation of PEG-fibrinogen mixture in the presence of 40 mmol/L calcium chloride solution and was mixed in a ratio of 3:1 v/v. A PEG-fibrin scaffold consisting of cells was fabricated and cultured. Optimal cell-cell ratio and growth factors (VEGF, EGF and bFGF) of optimized concentrations were used to stimulate viable chord-like vascular structures and were adapted from published report31. MSC-CDNs at 5 and 50 μg/mL were supplemented to the cell-laden PEG-fibrin scaffold, taking control sample without CDNs, and cultured for 10 days. Calcein-AM dye was used to stain the vascular structures and images were captured using inverted fluorescent microscope (Olympus X73). Data were processed using Tube Formation FastTrack AI Image Analysis (ibidi, Singapore, Singapore).

2.13. In vivo animal studies

2.13.1. Animals

The in vivo experiments were performed on male (obtained from The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) heterozygous lean (m+/+ Leprdb) BKS.Cg-Dock7m mice weighing between 26 and 32 g. All animals were housed individually in standard temperature-controlled, adequately ventilated, facility with 12 h light/dark cycle, and ad libitum food and water. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the National Advisory Committee for Laboratory Animal Research as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (Protocol no. A0373). In total, 5 mice received unlabelled MSC-CDNs as treatment control, while 2 received Cy5.5-MSC-CDNs instead for fluorescence in vivo imaging.

2.13.2. Excisional wound model

The excisional wound model was conducted as recommended with minor modifications32. Briefly, while mice were under anaesthesia, skin of the dorsal region of each mouse was shaved clean and disinfected with 70% ethanol before 2 full thickness excisions were created, 1 on each side of the midline, using a 15-mm diameter sterile biopsy punch (Miltex Inc, Mettawa, IL, USA). Immediately, 4.2 × 109 nanovesicles of MSC-CDNs, 1 × 106 of MSCs, or 4.8 × 109 nanovesicles of MSC-EVs per treatment were topically applied to wound 1, while another wound on the same mouse received saline as control. Successively, the wounds were covered with transparent Tegaderm dressing (3M, St Paul, MN, USA) and mice were monitored for pain indicators daily during the course of the experiment. Later on, all mice were euthanized by CO2 gas asphyxiation and wound tissues were harvested in tissue freezing medium (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) or in 4% paraformaldehyde and paraffin-embedded.

2.13.3. Imaging

Macroscopic photograph of wounds of mice that received MSC-CDNs were recorded daily post wounding using regular handheld mobile device before euthanasia on Day 7. The wound size was measured along the leading edge of newly generated epidermis and analysed using ImageJ software version 1.52 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The percentage of wound closure was calculated based on Days 0 and 7 of the same wound and compared between treatment and control. The harvested wound tissues were prepared for brightfield imaging using the scanner, AxioScan.Z1 (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany), by staining with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and picrosirius red (PSR). Mice that received Cy5.5-MSC-CDNs (MSC-CDNs were labelled with Cyanine5.5 N-hydroxysuccinimide (Cy5.5-NHS) monoester (Lumiprobe) as per supplier's recommendations and were dialysed in dialysis cups (10 kDa MWCO; ThermoFisher Scientific) overnight changing PBS twice to remove free dye (Cy5.5) were euthanised on Day 2 for fluorescence imaging using IVIS SpectrumCT (PerkinElmer Inc, Waltham, MA, USA) to identify any off-site interaction of MSC-CDNs at the saline control wound.

2.14. Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis between treatment and control (untreated) group was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.4.0, San Diego USA (unless otherwise stated). P values less than 0.05 were considered as significantly different.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Production and characterization of MSC-CDNs and MSC-EVs

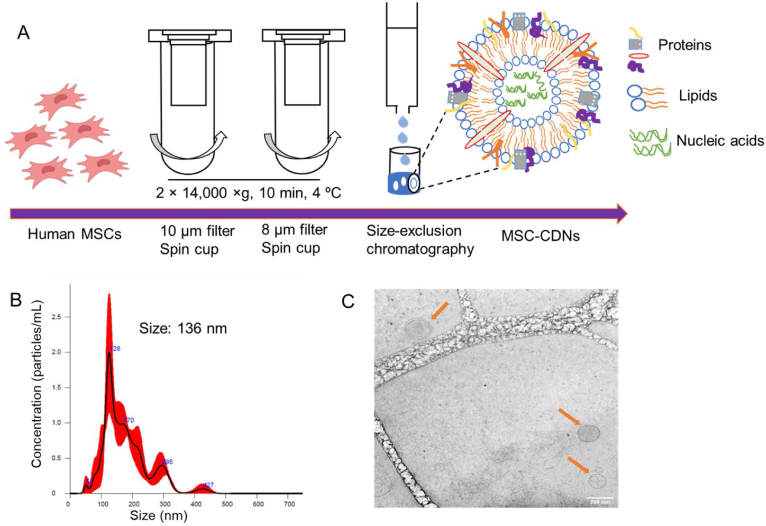

The production process of MSC-CDNs from MSC cells is schematized in Fig. 1A and adapted from our previously reported protocol27,28: MSC cells were added to spin cups fitted with different pore size membrane (10 and 8 μm) filters and sheared using centrifugal forces. The choice of these pore size (10 and 8 μm) membrane filters was based on an optimized protocol that enabled the production of nanovesicles (CDNs) with desirable size, polydispersity and protein content. The centrifugation at 14,000×g resulted in the formation of lipid bilayer fragments, which spontaneously self-assembled into nano spherical lipid bilayer constructs termed CDNs. During this self-assembling process, various biological cargos (proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids) derived from MSCs became integrated into CDNs. The so-formed CDNs were further purified via size exclusion chromatography to obtain the desired size range to be amenable for sterilization through a 0.22 μm membrane filter. The hydrodynamic diameter of MSC-CDNs measured via NTA was 136 ± 12.44 nm (n = 3) (Fig. 1B). Similarly, the hydrodynamic diameter of MSC-EVs secreted from cells was measured via NTA and showed values of 119 ± 12.3 nm (n = 3), indicating that MSC-CDNs were similar to naturally secreted exosomes (the smallest EVs), which usually range in size between 50 and 150 nm33,34. In addition, cryo-TEM images confirmed the vesicular structure of the nanovesicles (Fig. 1C), similar to naturally secreted EVs from bone marrow-derived MSCs3. The zeta potential, an indicator of colloidal stability measured based on electrophoretic mobility of the nanovesicles, was −7.87 ± 2.04 mV (n = 3) for MSC-CDNs and −3.90 ± 3.44 mV (n = 3) for MSC-EVs. This nearly neutral surface charge did not result in aggregation of nanovesicles. The concentration of nanovesicles, quantified via NTA, was ∼8.41 × 1010 MSC-CDNs per mL while MSC-EVs were ∼2.40 × 1010 nanovesicles per mL. MSC-CDNs and MSC-EVs were also quantified in terms of total proteins (μg/mL) via BCA assay and corresponded to 580 ± 4.03 μg/mL (from ∼7.5 × 106 cells) and 118.13 ± 0.39 μg/mL (from ∼2.25 × 107 cells), respectively. The total proteins quantified in MSC-CDNs were significantly (∼15-fold) higher in comparison to MSC-EVs, in agreement with our previous publication27. These results imply that MSC-CDNs generated via cell shearing approach using spin cups provided nanovesicles with size, morphology, and zeta potential comparable to EVs, but at higher production yield for downstream applications.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of production of MSC-CDNs via cell shearing approach using spin cups fitted with 10 and 8 μm polycarbonate membranes. MSC-CDNs were purified using a size-exclusion chromatography column packed with Sephadex G-50 pre equilibrated in PBS. (B) Size distribution profile of MSC-CDNs measured via NTA. (C) Cryo-TEM images of MSC-CDNs (scale bar: 200 nm).

3.2. Proteomics analysis

Proteins represent one of the most important biological components of EVs and take part in important processes such as intercellular communication35, 36, 37. Various cell membrane proteins, transmembrane proteins and cytosolic proteins are sorted into EVs as natural biological cargo during EV biogenesis38. Moreover, key surface proteins (cell membrane proteins) of EVs have shown to be responsible for their intrinsic targeting effect in various diseases39. Therefore, proteomic analysis was performed to assess how closely MSC-CDNs mimicked EVs in terms of proteins, and the proteomics profiles were then compared to the top proteins listed in the ExoCarta database (http://www.exocarta.org/).

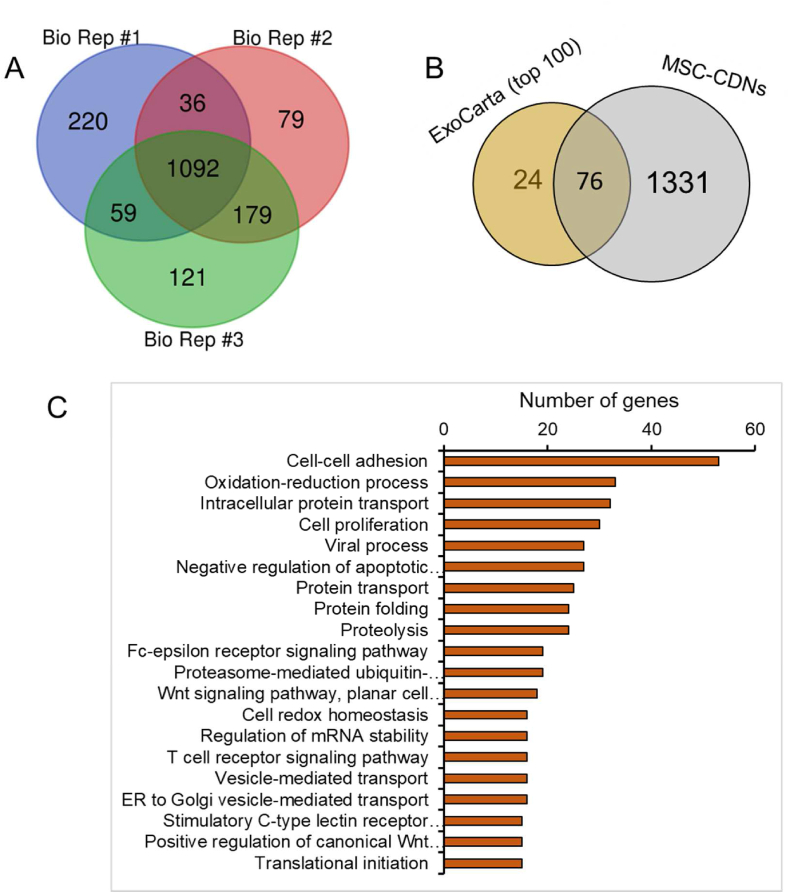

In this study, at 95% confidence interval (CI) and 1% FDR analysis, ∼1400 proteins were identified in MSC-CDNs in each independent biological replicate (n = 3), as shown in Fig. 2A, and 656 proteins were identified in MSC-EVs. In addition, 1092 (78%) proteins were common among those three independent biological replicates, suggesting that our CDNs’ production protocol via spin cups (which we proved is also amenable for upscaling through extrusion, data not shown) was reproducible and robust in generating MSC-CDNs with consistent protein profiles. Moreover, ∼72.5% of proteins (476 out of a total of 656 in MSC-EVs) were in common between MSC-CDN and MSC-EV samples (Supporting Information Fig. S1A), suggesting that the majority of the natural proteins in MSC-EVs were preserved in our mimetics.

Figure 2.

(A) Venn diagram for comparison of proteins from three independent biological replicates (Bio Rep, n = 3) of MSC-CDNs. (B) Comparison of proteins present in MSC-CDNs with ExoCarta (top 100) EV marker proteins. (C) Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of proteins present in MSC-CDNs with respect to biological processes (BP). Top 20 highly enriched GO terms were selected based on the number of genes involved in each GO term.

In addition, when comparing MSC-CDNs’ proteins with the ExoCarta's (a web-based compendium of exosomal cargo (http://www.exocarta.org)) 76 (out of the 100 top EV marker proteins (n = 100; ExoCarta)) were present in MSC-CDNs (Fig. 2B and Supporting Information Table S2). Similarly, 83 (out of the 100 top EV marker proteins (n = 100; ExoCarta)) were present in MSC-EVs (Supporting Information Fig. S1B and Table S1). These unique EV marker proteins are sorted in the final EVs during EV biogenesis either via ESCRT-dependent or independent pathways40,41. This is in line with previous studies, where EVs were isolated from human bone marrow MSCs, Huh7 hepatocellular carcinoma cells and U87 glioblastoma cells using ultracentrifugation method and reported to share ∼90 top EV marker proteins (n = 100; ExoCarta)42. In another study, EVs isolated from leech microglia using density gradient ultracentrifugation method reported to share ∼64 top EV marker proteins present in ExoCarta data (n = 100; ExoCarta)43. Similarly, label-free proteomic analysis of EVs derived from inducible hepatitis B virus-replicating HepAD38 cell line revealed that ∼83 proteins were overlapped with ExoCarta (n = 100) database44. This close similarity of MSC-CDNs with ExoCarta database suggests that MSC-CDNs produced via spin cups are enriched with similar exosomal marker proteins as naturally secreted EVs.

Next, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of proteins associated with MSC-CDNs and MSC-EVs with respect to the cellular component (CC) to predict and compare subcellular localization of proteins in MSC-CDNs and MSC-EVs. GO is a knowledgebase used to perform enrichment analysis on gene sets42. Based on the number of genes associated with our samples, the top 20 highly enriched GO terms with respect to CC were selected. Cytoplasm, cytosol, etracellular exosome, nucleus, membrane, nucleoplasm, cell–cell adherens junction and focal adhesion were highly enriched in GO terms for both MSC-CDNs and MSC-EVs (Supporting Information Figs. S2 and S3). Our results corroborate previously reported proteomic profiles of EVs derived from bone marrow MSCs, Huh7 hepatocellular carcinoma cells and U87 glioblastoma cells. In those studies, GO analysis revealed that EVs were enriched in extracellular vesicle proteins, membrane-associated proteins, extracellular matrix, focal adhesion and GTPases42.

In addition, GO analysis with respect to biological processes (BP) was performed to predict the biological mechanisms associated with MSC-CDNs’ and MSC-EVs’ proteins. As shown in Fig. 2C and Supporting Information Fig. S4, cell-cell adhesion, oxidation-reduction process, protein transport, cell proliferation, cell migration, and negative regulation of apoptotic processes were highly enriched in our MSC-CDNs and in MSC-EVs. Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) are binding proteins located on the surface of the cell and bind to other cells (cell–cell adhesion) or ECM (cell-ECM adhesion). These CAMs include integrins, selectins and cadherins, which play a vital role in wound healing45. CAMs during tissue repair enable cell proliferation, cell migration, protein production and also stimulate cell-cell adhesion and cell-matrix adhesion, and their bioadhesive nature allows them to bind to other ECM proteins such as vitronectin, fibronectin, laminin and collagen45. As reported, EVs from various stem cell origin are promising cell-free therapeutics in tissue regeneration and repair22,30,34. As a proof of this, our GO analysis for MSC-CDNs’ and MSC-EVs’ proteins showed various biological processes related to wound healing and tissue regeneration.

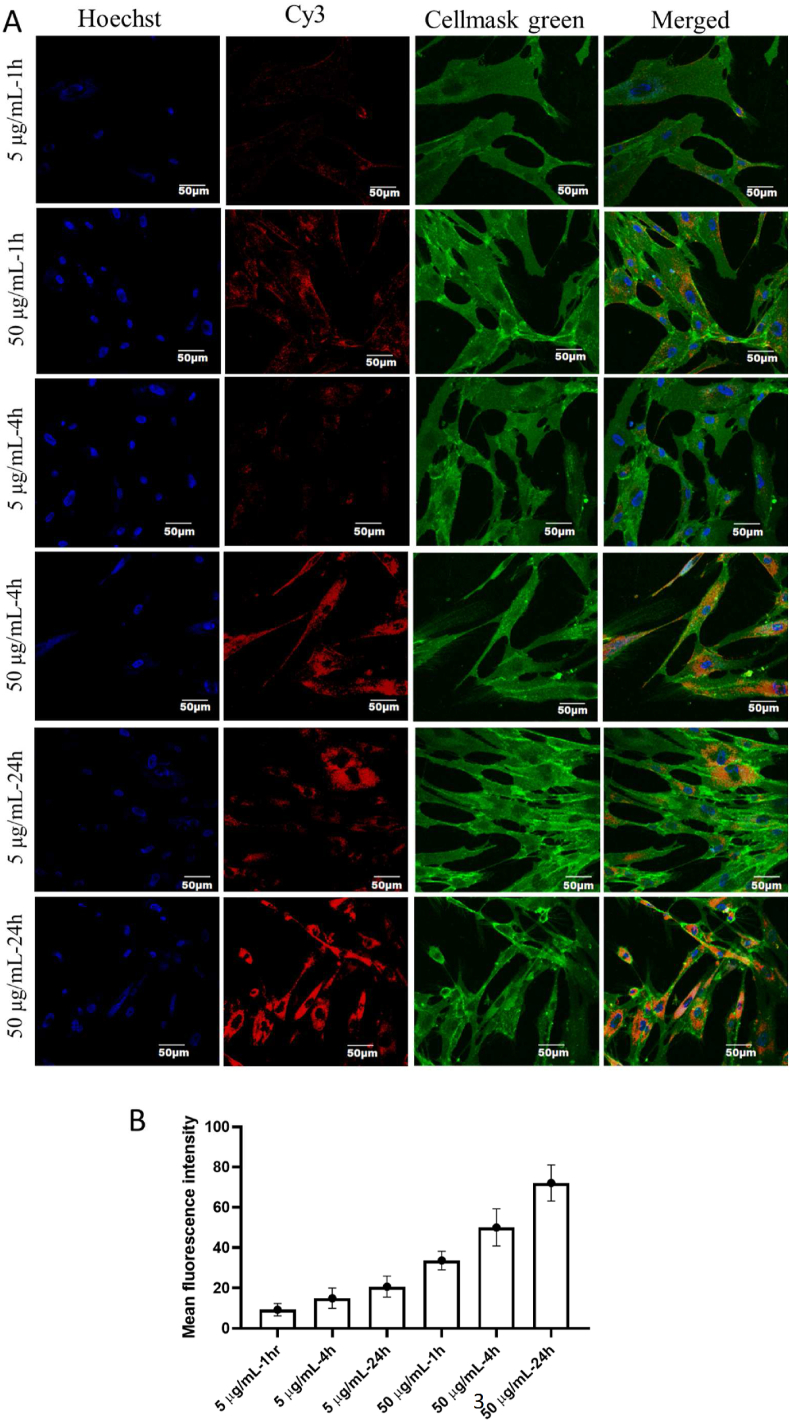

3.3. Uptake of MSC-CDNs by HDF cells

The uptake of Cy3-labelled MSC-CDNs by the HDF cells was confirmed using confocal microscopy. Cy3-MSC-CDNs cellular uptake was observed to be both time- and dose-dependent at the perinuclear region of the cytoplasm (Cy3-MSC-CDNs (red, Fig. 3). This time- and dose-dependent uptake demonstrates that the MSC-CDNs entered HDF cells through the plasma membranes30.

Figure 3.

(A) Uptake of Cy3-labelled MSC-CDNs (5 and 50 μg/mL) by HDF cells at different time points, visualized via confocal microscopy. Nuclei and cell membrane of skin fibroblast cells were stained with hoechst 33342 dye and cellmask green, respectively. Scale bars represent 50 μm. (B) Uptake of Cy3-labelled MSC-CDNs (5 and 50 μg/mL) by HDF cells at different time points, quantified using ImageJ. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

3.4. MSC-CDNs enhance HDF cell proliferation

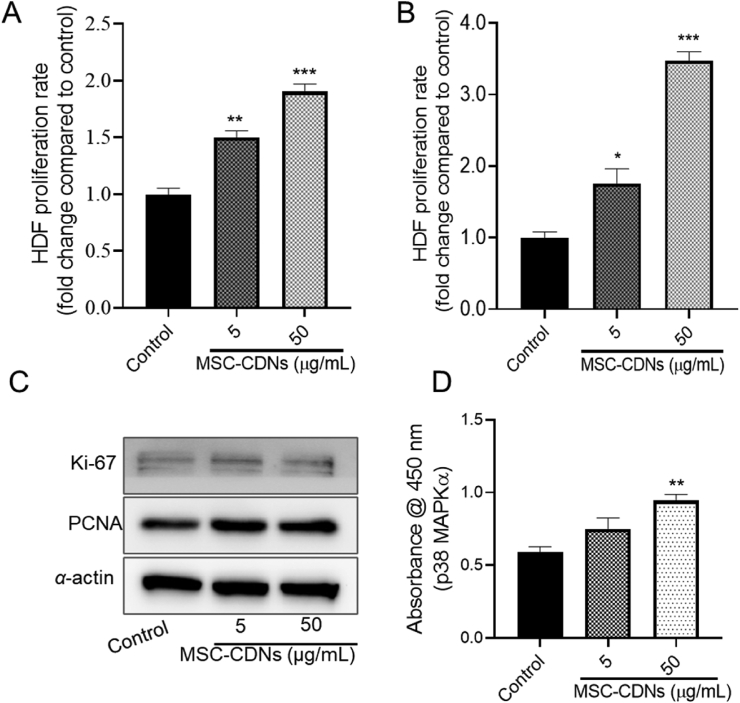

The proliferative phase of wound healing comprises proliferation and migration of fibroblasts to the wound area and is considered as one of the most important phases of wound healing3. HDF cells proliferate and migrate towards the wound bed to restore skin integrity in response to injury. To explore whether MSC-CDNs could induce HDF cells proliferation, HDF cells were treated with different concentrations (5 and 50 μg/mL) (these doses were selected based on a previous study on wound healing30) of MSC-CDNs and compared with untreated cells (control). Interestingly, HDF cells treated with MSC-CDNs enhanced cell proliferation in a dose- and time-dependent manner, as shown in Fig. 4A and B. It was observed that HDF cells treated with MSC-CDNs showed significantly (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001 for 5 and 50 μg/mL, respectively) higher cell proliferation compared to untreated cells (control) after 24 h of treatment (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, after 72 h, proliferation rate of HDF cells was more than 3-fold higher in 50 μg/mL MSC-CDNs treatment in comparison to untreated cells (Fig. 4B). This cell proliferation was further confirmed through Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) and Ki-67 analysis via western blotting. As shown in Fig. 4C, at the same level of α-actin (housekeeping protein), the expression level of PCNA and Ki-67 was higher in the MSC-CDN-treated HDF cells compared to controls. Our results are in accordance with previous reports, where nanovesicles (EV-mimetics) engineered from ESCs (although not suitable for large scale production due to ethics and costs) enhanced proliferation (by ∼1.3 fold) of HDF cells after 48 h31. Similarly, EVs secreted from iPSC-derived MSCs and human umbilical cord MSCs have been reported to enhance the skin fibroblast proliferation22,46.

Figure 4.

MSC-CDNs enhance proliferation of HDF cells. (A) HDF cells proliferation rate (fold change compared to control) measured after 24 h of MSC-CDNs (5 and 50 μg/mL) treatment. (B) HDF cells proliferation rate (fold change compared to control) measured after 72 h of MSC-CDNs (5 and 50 μg/mL) treatment. (C) Western blot analysis of cell proliferation-related marker proteins (PCNA and Ki-67) and their expression level in HDF cells after treatment with MSC-CDNs for 24 h, where α-actin was used as housekeeping protein. (D) Measurement of activation of p38 MAPK-α in HDF cells after treatment with MSC-CDNs for 24 h. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 compared with untreated cells (control). Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

In order to assess the biochemical pathway involved in this study, we further measured the activation level of p38 MAPK-α (mitogen-activated protein kinases) in HDF cells after treatment with MSC-CDNs via ELISA. MAPK signaling cascades are related to various cellular activities including cell proliferation, cell differentiation, and cell survival47. As shown in Fig. 4D, HDF cells treated with MSC-CDNs showed significantly (P < 0.01) higher level of p38 MAPK-α compared to untreated cells. Previously, it has been reported that conditioned medium (which might contain EVs) from human multipotent stromal cell enhanced wound healing via p38 MAPK activation48, suggesting that MSC-CDNs generated using spin cups possess biological cargos that could elicit a similar biological activity to naturally secreted EVs. Taken together, these results implicate that MSC-CDNs activate the MAPK signaling pathway and have the ability to enhance the proliferation of HDF cells.

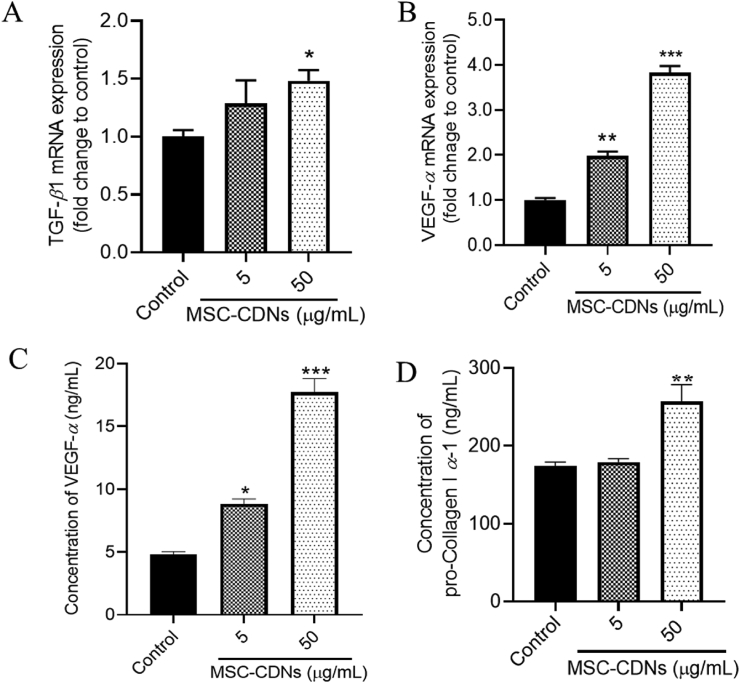

3.5. MSC-CDNs enhance growth factors and ECM protein secretions from HDF cells

Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and vascular endothelial growth factor alpha (VEGF-α) are cell proliferation-related growth factors that are secreted by HDF cells30. These growth factors have multifaceted roles: specifically, during wound healing, they have chemotactic properties that attract fibroblast cells towards the wound bed, act as mitogens to stimulate cell proliferation, promote vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, stimulate cells to produce ECM synthesis and fibroblast cells to repair damaged tissue30,49,50. In the preceding experiments, we observed that HDF cells treated with MSC-CDNs enhanced cell proliferation and cell proliferation-related markers. To confirm this, we measured the gene and protein expression levels of proliferation-related growth factors (TGF-β1 and VEGF-α). According to the qPCR results, the gene expression level (fold change to control) of TGF-β1 was significantly (P < 0.05) higher in MSC-CDN-(50 μμg/mL) treated HDF cells compared to the control after 24 h (Fig. 5A). Similarly, the gene expression level of VEGF-α was 2 and 4 times higher in 5 and 50 μg/mL MSC-CDN-treated HDF cells, respectively, as compared to the control after 24 h (Fig. 5B). To confirm and validate the qPCR results, the protein concentration of VEGF-α secreted by HDF cells after 24 h of MSC-CDNs treatment was measured through ELISA. As shown in Fig. 5C, the concentration of VEGF-α (ng/mL) secreted by HDF cells treated with MSC-CDNs was nearly 2 and 4 times higher in 5 and 50 μg/mL MSC-CDN-treated skin fibroblasts, respectively, compared with control (P < 0.001). These results are in agreement with a previous study, where nanovesicles engineered (EV-mimetics) (50 μg/mL) from embryonic stem cells were reported to enhance the secretion of growth factors (VEGF-α) from HDF cells (∼3-fold higher compared to untreated cells 48 h post treatment).

Figure 5.

Effects of MSC-CDNs on gene and protein expression levels of growth factors and ECM proteins secreted by HDF cells. (A, B) qPCR analysis for TGF-β1 and VEGF-α expressed as fold change to control. (C, D) Concentration of VEGF-α and Pro-Collagen I α-1 measured via ELISA kit. The data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 compared to control.

It has been reported that the most abundant proteins in the ECM are the collagens and are synthesised by cells, particularly fibroblasts, as pro-collagens51. As shown in Fig. 5D, the concentration of pro-collagen I α-1 secreted by HDF cells was measured to be significantly (P < 0.01) higher in MSC-CDN- (50 μg/mL) treated cells compared with control. This indicates that the MSC-CDNs promote the secretion of collagen I from HDF cells and the expression level of collagen I increased proportionally to HDF cells’ increase. ECM is a dynamic, organized interlocking mesh of various macromolecules (collagens, laminins, elastins, fibronectins, proteoglycans) and proteolytic enzymes52. ECM possesses numerous functions, since it provides structure, organization, and orientation to cells and tissues. It also acts as a template for cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis, differentiation and adhesion and, finally, it regulates cell activity and function via directly binding to integrins and other cell surface receptors53. Interestingly, it has also being found to act as a reservoir for growth factors and to regulate their bioavailability54. Once again, these results demonstrate that MSC-CDNs have the potential to stimulate HDF cells to increase the secretion of growth factors and ECM proteins into the surrounding microenvironment, which is utmost necessary during wound healing.

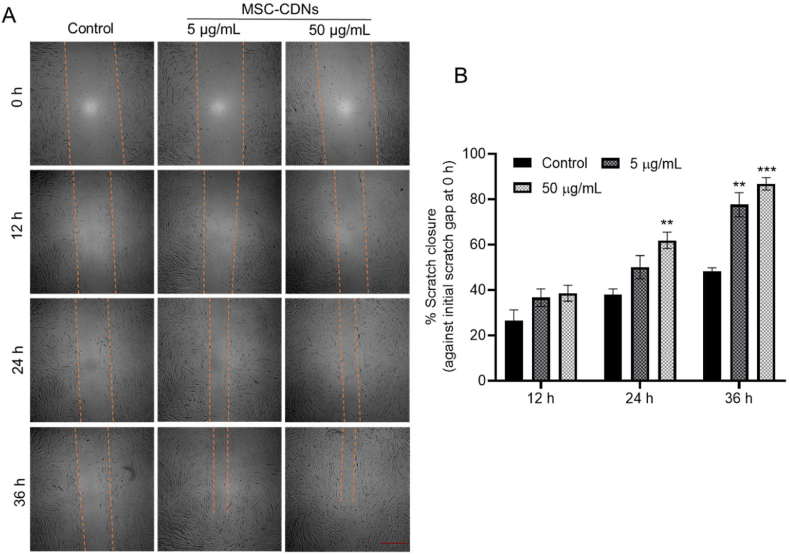

3.6. MSC-CDNs enhance in vitro scratch closure in HDF cells

The ability of MSC-CDNs to enhance HDF cell migration towards the wound gap during wound healing was assayed via scratch closure (as a surrogate of wound healing) assay. In this, HDF cells were cultured to form a confluent monolayer and were scratched to form a certain gap between cell monolayer, as shown in Fig. 6A. After creation of the scratch, cells were treated with different concentrations (5 and 50 μg/mL) of MSC-CDNs and the percentage of scratch closure with respect to the initial gap (0 h) was calculated and compared with untreated cells (control). Fig. 6A clearly indicates that HDF cells treated with MSC-CDNs migrated faster towards the gap in a dose-dependent manner compared to the control. Further, it was observed that at 24 h time point, more than 50% of the gap was closed in the MSC-CDNs treated groups, while untreated (control) group closed only by ∼36% (Fig. 6B). The results were more prominent at 36 h time point, where ∼90% of the scratch gap was closed in the MSC-CDNs (50 μg/mL) treated groups. In contrast, untreated control closed only ∼48% of the scratch gap. The ability of naturally cell secreted nanovesicles (MSC-EVs) to enhance the migration of HDF cells towards scratch gap compared to untreated cells (control) has been documented in previous studies30,55. Similar to naturally cell secreted nanovesicles (MSC-EVs, 50 μg/mL), MSC-CDNs enhanced migration of HDF cells towards the scratch gap (which is an important phase of wound healing and tissue regeneration30) in addition to HDF cells proliferation.

Figure 6.

MSC-CDNs enhance in vitro scratch closure in HDF cells. (A) Representative photomicrograph of the gap edge (orange line) in the in vitro scratch closure assay (scale bar 500 μm). (B) Quantitative analysis of percent of scratch closure (as a surrogate of wound healing) after MSC-CDNs treatment at specified time points and compared with control (untreated cells) (∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 compared with control). Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

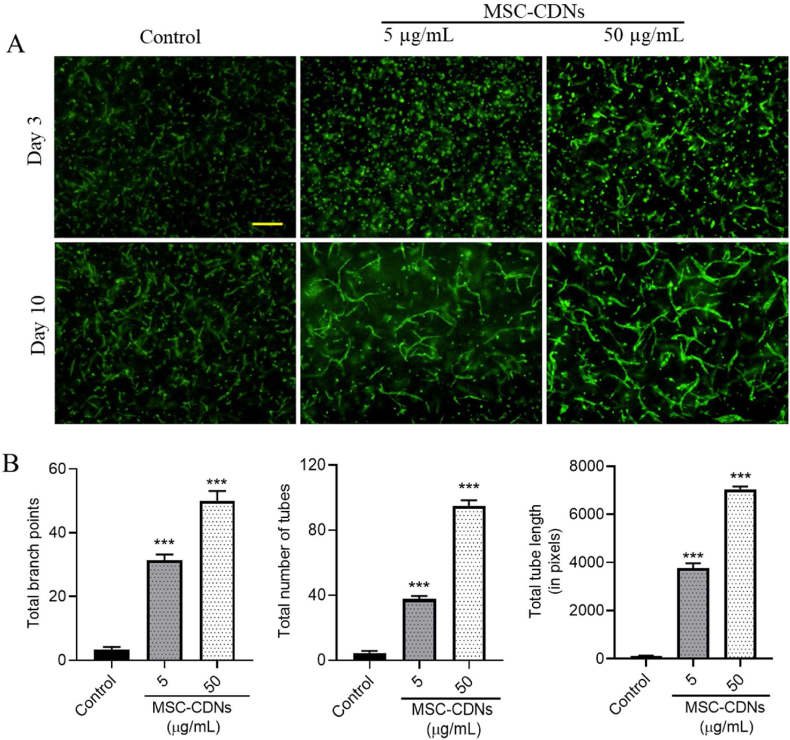

3.7. MSC-CDNs enhance angiogenesis in HDME cells in a 3D PEG-fibrin scaffold

Angiogenesis is the formation of new capillaries from the pre-existing vasculature by migration and proliferation of endothelial cells that eventually develop into mature blood vessels. Angiogenesis plays a major role in wound healing, as it is essential to deliver immune cells, to remove debris and to provide nutrients and oxygen for tissue regeneration56. This process is a crucial step in various physiological and pathological processes, including wound healing and tissue repair57. During the proliferative phase of wound healing, various growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and angiopoietins are released from various cells, and act as molecular mediators of angiogenesis56,58,59. In the preceding experiments, we observed that MSC-CDNs enhanced growth factors (TGF-β1 and VEGF-α) and ECM protein secretions from HDF cells (2D cell culture model) (Fig. 5). We hypothesized that MSC-CDNs could induce angiogenesis in HDME (human dermal microvascular endothelial) cells, when co-cultured with HDF cells in a 3D PEG-fibrin scaffold. As shown in Fig. 7A, MSC-CDNs enhanced microvascular tubular network formation (angiogenesis) in HDME cells in a time and dose-dependent manner at day 10 post treatment. Furthermore, the total number of branch points, tubes and tube length were found to be significantly (P < 0.001) higher in MSC-CDN-treated samples compared to control (Fig. 7B). The ability of naturally secreted EVs (especially from stem cells) to enhance the tube formation in endothelial cells (i.e. pro-angiogenic activity) in 2D Matrigel assay has been reported and showed that EVs from stem cell origin enhanced angiogenesis in vitro via transfer of endogenous biological cargos loaded in the EVs22,60, 61, 62. Similarly, we proved the pro-angiogenic potency of CDNs, which has not been previously reported in a 3D PEG-fibrin scaffold. The co-culture of cells in the 3D PEG-fibrin scaffold offers several advantages over 2D cell culture (monolayer), where 3D co-cultured cells structurally resemble native tissue, and allow spatial and temporal interaction among multiple cells63,64.

Figure 7.

MSC-CDNs enhance angiogenesis in HDME cells in vitro in a 3D PEG-fibrin scaffold. (A) Representative images of microvascular tubular network formation (angiogenesis) in MSC-CDN-treated HDME cells in a dose-dependent manner (scale bar: 200 μm). (B) Quantification of fractal dimensions of microvascular networks formed in HDME cells after MSC-CDNs treatment and compared without treatment (control) after 10 days, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

3.8. MSC-CDNs promote wound healing in an in vivo excisional wound mouse model

To confirm the efficacy of MSC-CDNs in promoting wound healing, in vivo full thickness excisions (deep wound with loss of continuity of the skin, and tissue loss of the epidermis and dermis) were carried out on mice using a biopsy punch, i.e., a simple and efficient process with consistent wounding depth and area32. The fluorescence signal of Cy5.5 was detected on and around the Cy5.5-MSC-CDN-treated wound (right side), and no fluorescence signal was detected at the control wound (left side) even after reducing the minima and increasing the maxima of radiant efficiency (Fig. 8A). This confirms that there was no crossover of the MSC-CDNs from the treatment wound bed to the control wound bed and the MSC-CDNs were localized at the site of application.

Figure 8.

MSC-CDNs promote wound healing in an in vivo excisional wound mouse model. (A) Representative image showing retention of Cy5.5-MSC-CDNs at the treated wound (right) with high fluorescence of Cy5.5 in IVIS imaging 2 days post topical application of Cy5.5-MSC-CDNs and control wound (left) without any fluorescence. (B) Representative images of full thickness wound and their subsequent contraction over 7 days after treatment. (C) Reduction in wound size (mm) over 7 days post wounding and treatment with MSC-CDNs, MSC-EVs and MSCs (whole cells). (D) Wound recovery calculated against wound gap at Day 0, where the percentage of wound recovery in MSC-CDNs (n = 5), MSC-EVs (n = 4) and MSCs (n = 4) is almost twice compared to control. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, ∗P < 0.05 vs. control.

As mentioned before, closure of wound requires a mix of contraction and re-epithelialization, which is deduced from decreasing the distance of peripheral edges (wound size), as well as the differentiation of the dark red surface that had developed over the wound to a relatively normal lighter skin colour65. As shown in Fig. 8B, the wound healing effect of MSC-CDNs, as well as of MSC-EVs and MSCs used as positive controls, was clearly observed on Day 4 post treatment and almost completely recovered on Day 7 compared to the control wound, which remained bigger in size till Day 7. This was further confirmed by comparing the wound size (mm) between MSC-CDNs treatment and control, where significant (P < 0.05) reduction in wound size was observed in the treatment wound compared to control at day 7 (Fig. 8C). The overall percentage of wound recovery after treatment with MSC-CDNs, MSC-EVs and MSCs was calculated at day 7 against wound gap on Day 0, as shown in Fig. 8D. Intriguingly, MSC-CDNs, MSC-EVs and MSCs similarly and significantly (P < 0.05) promoted the wound healing process almost 2-fold faster than that of control (Fig. 8D), suggesting that they carry several biological molecules responsible for promoting wound healing.

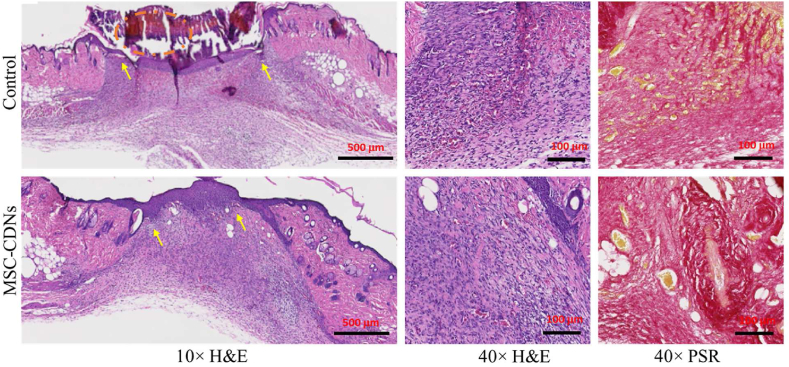

Next, tissues from skin wounds were harvested on Day 7 post-wounding and 10 mm sections were stained with H&E as well as PSR, as shown in Fig. 9 and Supporting Information Fig. S5. H&E staining is the most common tool to visualize the different types of cells present at the wound site, as haematoxylin stains nucleus (blue) and eosin stains cytoplasm of the cells in pink66. PSR, on the other hand, helps to expose the degree of repair and remodelling according to ECM deposition and arrangement by staining collagen in red67. As observed in Fig. 9, under 10 × (H&E) magnification, the control wound showed a thick crust from dead tissue comprising red blood cells, platelets, and fibrin (orange dotted circle), poor integrated epithelium (yellow arrows) and layer of blood immediately beneath the arrows, thus appearing reddish. In contrast, the treated wound showed fully integrated epithelium, with signs of developing epidermal ridges (yellow arrows). Fibroblasts are responsible for repairing damaged tissue by enhancing formation of granulation tissues and restoring the ECM, which provides a structural support to cells and tissues at the wound site68. These fibroblast cells are easily distinguished by the spindle shape, large euchromatic nuclei and the basophilic cytoplasm, and were densely concentrated (due to migration at the site of injury) at the periphery of the wound in MSC-CDN-treated samples compared to control (40 × H&E). Similarly, increased collagen (ECM) deposition and maturation at the injured site is a sign of wound recovery and remodelling, and is used to assess the degree of wound healing22. In PSR staining at 40 × magnification, several bundles of collagen (stained in deep red) and a few blood cells (stained in yellow) were observed in the treatment group (MSC-CDNs); in contrast, a few streaks of collagen and a large number of blood cells were observed in the control groups (Supporting Information Fig. S6). This indicates that collagen, as ECM protein, is perfectly deposited in the treatment group (MSC-CDNs) compared to control group, where tissue regeneration is still in progress (i.e., more blood cells are present in the control group).

Figure 9.

Representative images of histological examination of 10 mm thick cross section of skin wounds 7-day post treatment with MSC-CDNs and compared with control. Tissues were stained with H&E and PSR, then imaged at 10 × (scale bar: 500 μm) and 40 × (scale bar: 100 μm) magnification. Yellow color pointed arrows indicate full integrated epithelium with signs of developing epidermal ridges in MSC-CDNs treated sample while absent in control sample.

Studies have demonstrated that EVs isolated from stem cells accelerate wound healing and tissue regeneration in vitro as well as in vivo through multiple cellular processes, such as cell proliferation, cell migration, angiogenesis, and re-epithelization22,34,46. For instance, MSC-EVs isolated from human umbilical cord MSCs (HucMSC-EVs) exhibited significantly accelerated re-epithelialization with increased expression of PCNA and collagen I in vivo when applied to wounds46. Furthermore, HucMSC-EVs promoted proliferation and inhibited apoptosis of skin cells after heat-stress in vitro46. Similarly, Zhang et al.69 developed a cell-free therapy for wound healing using adipose tissue stem cell-derived EVs (ADSC-EVs), where these ADSC-EVs were efficiently internalized into HDF cells and showed a significant dose-dependent enhancement in cell proliferation and migration. Moreover, both mRNA and protein levels of collagen I and TGF-β1 were increased in fibroblasts after treatment with ADSC-EVs. ADSC-EVs promoted wound healing via PI3K/Akt signaling pathway69. In agreement with previous findings (although those were limited to naturally secreted EVs), our results suggest that MSC-CDNs could mimic naturally secreted EVs and possess the ability to accelerate wound healing in vitro and in in vivo. To our knowledge, such a comprehensive study that investigates the therapeutic potential of MSC-CDNs and compares it with MSC-EVs and MSCs for wound healing and tissue regenerative applications is unprecedented in the literature.

4. Conclusions

CDNs from MSCs were successfully produced as EV-mimetics via cell shearing approach. MSC-CDNs mimic naturally cell-secreted EVs in terms of size and zeta potential while requiring a simpler and convenient production method. MSC-CDNs emulated EVs with respect to key canonical proteins that were associated with multiple biological functions (cell adhesion, cell proliferation) responsible for wound healing. These MSC-CDNs activated MAPK signaling pathway in HDF cells, and enhanced proliferation and migration of HDF cells towards the wound bed, along with an enhanced release of cell-proliferation related markers, growth factors and ECM proteins from HDF cells. For the first time, we demonstrate that MSC-CDNs as EV-mimetics promoted angiogenesis in HDME cells co-cultured with HDF cells in a 3D PEG-fibrin scaffold in vitro. MSC-CDNs also promoted wound healing in an in vivo wound (excisional) mouse model to a similar extent to MSC-EVs and even MSCs (whole cells), and almost 2 times faster compared to the untreated control mice. Besides similar therapeutic efficacy in wound healing, MSC-CDNs seem to offer several advantages over both EVs and MSCs: in terms of production time, yields and costs, for CDNs production cells do not require to secrete vesicles (which is a tedious process that results in only a few μg of EVs in terms of protein amount) and/or to use EV-free medium (which is very costly compared to normal cell growth media); they can be directly produced from confluent cells (which can be continuously cultured in a bioreactor) and are amenable for scale-up production through extrusion. In addition, CDNs can be easily lyophilized and stored in powder at room temperature over 6 months without compromising their physical, morphological, and intrinsic biological properties28. Lyophilization of MSC-CDNs would avoid cold chain and enable simpler sample handling. Moreover, MSC-CDN applications involve minimal ethical requirement in comparison to MSCs. Overall, this study highlights that CDNs hold a lot of promise for various biomedical applications, although future studies are required to further characterize their acute and chronic toxicity, as well as eventual immunogenicity.

Acknowledgments

Yub Raj Neupane would like to acknowledge the Ministry of Education, Singapore for providing SINGA (Singapore International Graduate Award) scholarship to support his graduate study in Department of Pharmacy, National University of Singapore. Chenyuan Huang would like to acknowledge the Ministry of Education for providing research scholarship to support his graduate study in Department of Surgery, National University of Singapore. Authors would like to acknowledge Norliza Binte Esmail Sahib for the histology analyses.

This work was supported by the National University of Singapore (NanoNash Program A-0004336-00-00 & A-0008504-00-00, Singapore), and Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (grant number 001487-00001). Giorgia Pastorin. would also like to thank the Industry Alignment Fund—Pre-Positioning (IAF-PP) grant (A20G1a0046 and R-148-000-307-305/A-0004345-00-00). This work was also supported by the Singapore Ministry of Education, under its Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund Tier 1 (10051 - MOE AcRF Tier 1: Thematic Call 2020) from Bertrand Czarny. Jiong-Wei Wang would like to thank the National University of Singapore NanoNASH Program (NUHSRO/2020/002/NanoNash/LOA) and the National University of Singapore Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine Nanomedicine Translational Research Program (NUHSRO/2021/034/TRP/09/Nanomedicine). Authors would also like to thank for the financial supports from Agency for Science, Technology, and Research (A∗STAR, Singapore) Advanced Manufacturing and Engineering Individual Research Grant (AME IRG) (Project ID: A1883c0013, Singapore).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.10.022.

Contributor Information

Bertrand Czarny, Email: bczarny@ntu.edu.sg.

Giorgia Pastorin, Email: phapg@nus.edu.sg.

Author contributions

Data curation, Yub Raj Neupane, Harish K Handral, and Syed Abdullah Alkaff; Formal analysis, Wei Heng Chng, Gopalakrishan Venkatesan, Chenyuan Huang and Choon Keong Lee; Methodology, Yub Raj Neupane; Resources, Bertrand Czarny, Jiong-Wei Wang and Giorgia Pastorin; Supervision Giorgia Pastorin; Visualization, Rhonnie Austria Dienzo, Gopu Sriram, Wen Feng Lu, Yusuf Ali; Writing–original draft, Yub Raj Neupane.; Review & editing, Giorgia Pastorin. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Rodrigues M., Kosaric N., Bonham C.A., Gurtner G.C. Wound healing: a cellular perspective. Physiol Rev. 2019;99:665–706. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00067.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum C.L., Arpey C.J. Normal cutaneous wound healing: clinical correlation with cellular and molecular events. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:674–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shabbir A., Cox A., Rodriguez-Menocal L., Salgado M., van Badiavas E. Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes induce proliferation and migration of normal and chronic wound fibroblasts, and enhance angiogenesis in vitro. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24:1635–1647. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rani S., Ritter T. The exosome-a naturally secreted nanoparticle and its application to wound healing. Adv Mater. 2016;28:5542–5552. doi: 10.1002/adma.201504009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duscher D., Barrera J., Wong V.W., Maan Z.N., Whittam A.J., Januszyk M., et al. Stem cells in wound healing: the future of regenerative medicine? A mini-review. Gerontology. 2016;62:216–225. doi: 10.1159/000381877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nourian Dehkordi A., Mirahmadi Babaheydari F., Chehelgerdi M., Raeisi Dehkordi S. Skin tissue engineering: wound healing based on stem-cell-based therapeutic strategies. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:111. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1212-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freitas G.P., Lopes H.B., Souza A.T.P., Oliveira P.G.F.P., Almeida A.L.G., Souza L.E.B., et al. Cell therapy: effect of locally injected mesenchymal stromal cells derived from bone marrow or adipose tissue on bone regeneration of rat calvarial defects. Sci Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50067-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hocking A.M., Gibran N.S. Mesenchymal stem cells: paracrine signaling and differentiation during cutaneous wound repair. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:2213–2219. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teixeira-Pinheiro L.C., Toledo M.F., Nascimento-dos-Santos G., Mendez-Otero R., Mesentier-Louro L.A., Santiago M.F. Paracrine signaling of human mesenchymal stem cell modulates retinal microglia population number and phenotype in vitro. Exp Eye Res. 2020;200 doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romano M., Zendrini A., Paolini L., Busatto S., Berardi A.C., Bergese P., et al. In: Nanomaterials for theranostics and tissue engineering. Rossi Filippo, Rainer Alberto., editors. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2020. Extracellular vesicles in regenerative medicine; pp. 29–58. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Master Z., McLeod M., Mendez I. Benefits, risks and ethical considerations in translation of stem cell research to clinical applications in Parkinson's disease. J Med Ethics. 2007;33:169–173. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.013169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorecka J., Kostiuk V., Fereydooni A., Gonzalez L., Luo J., Dash B., et al. The potential and limitations of induced pluripotent stem cells to achieve wound healing. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:87. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1185-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teng M., Huang Y., Zhang H. Application of stems cells in wound healing—an update. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22:151–160. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong S.Y., Lee C.K., Huang C., Ou Y.H., Charles C.J., Richards A.M., et al. Extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular diseases: alternative biomarker sources, therapeutic agents, and drug delivery carriers. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3272. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang C., Neupane Y.R., Lim X.C., Shekhani R., Czarny B., Wacker M.G., et al. In: Makowski Gregory S., editor. vol. 103. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2021. Extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular disease; pp. 47–95. (Advances in clinical chemistry). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suri R., Neupane Y.R., Jain G.K., Kohli K. Recent theranostic paradigms for the management of age-related macular degeneration. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2020;153 doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2020.105489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neupane Y.R., Mahtab A., Siddiqui L., Singh A., Gautam N., Rabbani S.A., et al. Biocompatible nanovesicular drug delivery systems with targeting potential for autoimmune diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26:5488–5502. doi: 10.2174/1381612826666200523174108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manchon E., Hirt N., Bouaziz J.D., Jabrane-Ferrat N., Al-Daccak Stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles: potential therapeutics for wound healing in chronic inflammatory skin diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:3130. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang B.C., Tian X.Y., Hao J., Xu G., Zhang W.G. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration. Cell Transplant. 2020;29 doi: 10.1177/0963689720908500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casado-Díaz A., Quesada-Gómez J.M., Dorado G. Extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) in regenerative medicine: applications in skin wound healing. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:146. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang J.H., Zhang J., Xiong J.Y., Sun S.Q., Xia J., Yang L., et al. Stem cell-derived nanovesicles: a novel cell-free therapy for wound healing. Stem Cells Int. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/1285087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J.Y., Guan J.J., Niu X., Hu G.W., Guo S.C., Li Q., et al. Exosomes released from human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived MSCs facilitate cutaneous wound healing by promoting collagen synthesis and angiogenesis. J Transl Med. 2015;13:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0417-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cha H., Hong S., Park J.H., Park H.H. Stem cell-derived exosomes and nanovesicles: promotion of cell proliferation, migration, and anti-senescence for treatment of wound damage and skin ageing. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12:1135. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12121135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Théry C., Amigorena S., Raposo G., Clayton A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2006;30:3–22. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb0322s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haque S., Sinha N., Ranjit S., Midde N.M., Kashanchi F., Kumar S. Monocyte-derived exosomes upon exposure to cigarette smoke condensate alter their characteristics and show protective effect against cytotoxicity and HIV-1 replication. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16301-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jang S.C., Kim O.Y., Yoon C.M., Choi D.S., Roh T.Y., Park J., et al. Bioinspired exosome-mimetic nanovesicles for targeted delivery of chemotherapeutics to malignant tumors. ACS Nano. 2013;7:7698–7710. doi: 10.1021/nn402232g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goh W.J., Zou S., Ong W.Y., Torta F., Alexandra A.F., Schiffelers R.M., et al. Bioinspired cell-derived nanovesicles versus exosomes as drug delivery systems: a cost-effective alternative. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14725-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neupane Y.R., Huang C., Wang X., Chng W.H., Venkatesan G., Zharkova O., et al. Lyophilization preserves the intrinsic cardioprotective activity of bioinspired cell-derived nanovesicles. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:1052. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13071052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeong D., Jo W., Yoon J., Kim J., Gianchandani S., Gho Y.S., et al. Nanovesicles engineered from ES cells for enhanced cell proliferation. Biomaterials. 2014;35:9302–9310. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sriram G., Handral H.K., Gan S.U., Islam I., Rufaihah A.J., Cao T. Fabrication of vascularized tissue constructs under chemically defined culture conditions. Biofabrication. 2020;12 doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/aba0c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan N.S., Wahli W. Studying wound repair in the mouse. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol. 2013;3:171–185. doi: 10.1002/9780470942390.mo130135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doyle L.M., Wang M.Z. Overview of extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells. 2019;8:727. doi: 10.3390/cells8070727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao B., Zhang Y., Han S., Zhang W., Zhou Q., Guan H., et al. Exosomes derived from human amniotic epithelial cells accelerate wound healing and inhibit scar formation. J Mol Histol. 2017;48:121–132. doi: 10.1007/s10735-017-9711-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maacha S., Bhat A.A., Jimenez L., Raza A., Haris M., Uddin S., et al. Extracellular vesicles-mediated intercellular communication: roles in the tumor microenvironment and anti-cancer drug resistance. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:55. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0965-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kourembanas S. Exosomes: vehicles of intercellular signaling, biomarkers, and vectors of cell therapy. Annu Rev Physiol. 2015;77:13–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021014-071641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pluchino S., Smith J.A. Explicating exosomes: reclassifying the rising stars of intercellular communication. Cell. 2019;177:225–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bebelman M.P., Smit M.J., Pegtel D.M., Baglio S.R. Biogenesis and function of extracellular vesicles in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;188:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy D.E., de Jong O.G., Brouwer M., Wood M.J., Lavieu G., Schiffelers R.M., et al. Extracellular vesicle-based therapeutics: natural versus engineered targeting and trafficking. Exp Mol Med. 2019;51:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0223-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y., Liu Y., Liu H., Tang W.H. Exosomes: biogenesis, biologic function and clinical potential. Cell Biosci. 2019;9:19. doi: 10.1186/s13578-019-0282-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colombo M., Moita C., van Niel G., Kowal J., Vigneron J., Benaroch P., et al. Analysis of ESCRT functions in exosome biogenesis, composition and secretion highlights the heterogeneity of extracellular vesicles. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:5553–5565. doi: 10.1242/jcs.128868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haraszti R.A., Didiot M.-C., Sapp E., Leszyk J., Shaffer S.A., Rockwell H.E., et al. High-resolution proteomic and lipidomic analysis of exosomes and microvesicles from different cell sources. J Extracell Vesicles. 2016;5 doi: 10.3402/jev.v5.32570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arab T., Raffo-Romero A., Van Camp C., Lemaire Q., Le Marrec-Croq F., Drago F., et al. Proteomic characterisation of leech microglia extracellular vesicles (EVs): comparison between differential ultracentrifugation and OptiprepTM density gradient isolation. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019;8 doi: 10.1080/20013078.2019.1603048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jia X., Chen J., Megger D.A., Zhang X., Kozlowski M., Zhang L., et al. Label-free proteomic analysis of exosomes derived from inducible hepatitis B virus-replicating HepAD38 cell line. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2017;16:S144–S160. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M116.063503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Houreld N.N., Ayuk S.M., Abrahamse H. Cell adhesion molecules are mediated by photobiomodulation at 660 nm in diabetic wounded fibroblast cells. Cells. 2018;7:30. doi: 10.3390/cells7040030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang B., Wang M., Gong A.H., Zhang X., Wu X.D., Zhu Y.H., et al. HucMSC-exosome mediated-Wnt4 signaling is required for cutaneous wound healing. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2158–2168. doi: 10.1002/stem.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang W., Liu H.T. MAPK signal pathways in the regulation of cell proliferation in mammalian cells. Cell Res. 2002;12:9–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yew T.L., Hung Y.T., Li H.Y., Chen H.W., Chen L.L., Tsai K.S., et al. Enhancement of wound healing by human multipotent stromal cell conditioned medium: the paracrine factors and p38 MAPK activation. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:693–706. doi: 10.3727/096368910X550198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Velnar T., Bailey T., Smrkolj V. The wound healing process: an overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:1528–1542. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Greenhalgh D.G. The role of growth factors in wound healing. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 1996;41:159–167. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199607000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xue M., Jackson C.J. Extracellular matrix reorganization during wound healing and its impact on abnormal scarring. Adv Wound Care. 2015;4:119–136. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mathew-Steiner S.S., Roy S., Sen C.K. Collagen in wound healing. Bioengineering. 2021;8:63. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering8050063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Domínguez-Bendala J., Inverardi L., Ricordi C. Regeneration of pancreatic beta-cell mass for the treatment of diabetes. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12:731–741. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.679654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schultz G.S., Wysocki A. Interactions between extracellular matrix and growth factors in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:153–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim S., Lee S.K., Kim H., Kim T.M. Exosomes secreted from induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells accelerate skin cell proliferation. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3119. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bodnar R.J. Chemokine regulation of angiogenesis during wound healing. Adv Wound Care. 2015;4:641–650. doi: 10.1089/wound.2014.0594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu P., Yang Q., Wang Q., Shi C.S., Wang D.L., Armato U., et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells-exosomes: a promising cell-free therapeutic tool for wound healing and cutaneous regeneration. Burn Trauma. 2019;7:38. doi: 10.1186/s41038-019-0178-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ucuzian A.A., Gassman A.A., East A.T., Greisler H.P. Molecular mediators of angiogenesis. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:158–175. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181c7ed82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chong S.Y., Zharkova O., Yatim S.M.J.M., Wang X., Lim X.C., Huang C., et al. Tissue factor cytoplasmic domain exacerbates post-infarct left ventricular remodeling via orchestrating cardiac inflammation and angiogenesis. Theranostics. 2021;11:9243. doi: 10.7150/thno.63354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hu L., Wang J., Zhou X., Xiong Z., Zhao J., Yu R., et al. Exosomes derived from human adipose mensenchymal stem cells accelerates cutaneous wound healing via optimizing the characteristics of fibroblasts. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep32993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hu Y., Rao S.S., Wang Z.X., Cao J., Tan Y.J., Luo J., et al. Exosomes from human umbilical cord blood accelerate cutaneous wound healing through miR-21-3p-mediated promotion of angiogenesis and fibroblast function. Theranostics. 2018;8:169–184. doi: 10.7150/thno.21234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li X.C., Jiang C.Y., Zhao J.G. Human endothelial progenitor cells-derived exosomes accelerate cutaneous wound healing in diabetic rats by promoting endothelial function. J Diabetes Complicat. 2016;30:986–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ashok A., Choudhury D., Fang Y., Hunziker W. Towards manufacturing of human organoids. Biotechnol Adv. 2020;39 doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2019.107460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ranga A., Gjorevski N., Lutolf M.P. Drug discovery through stem cell-based organoid models. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;69–70:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kubinova S., Zaviskova K., Uherkova L., Zablotskii V., Churpita O., Lunov O., et al. Non-thermal air plasma promotes the healing of acute skin wounds in rats. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep45183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chan J.K.C. The wonderful colors of the hematoxylin–eosin stain in diagnostic surgical pathology. Int J Surg Pathol. 2014;22:12–32. doi: 10.1177/1066896913517939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lattouf R., Younes R., Lutomski D., Naaman N., Godeau G., Senni K., et al. Picrosirius red staining: a useful tool to appraise collagen networks in normal and pathological tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2014;62:751–758. doi: 10.1369/0022155414545787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singer A.J., Clark R.A.F. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang W., Bai X.Z., Zhao B., Li Y., Zhang Y.J., Li Z.Z., et al. Cell-free therapy based on adipose tissue stem cell-derived exosomes promotes wound healing via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2018;370:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.