Abstract

Thyroid hormone (T3) activates nuclear receptor transcription factors, encoded by the TRα (NR1A1) and TRβ (NR1A2) genes, to regulate target gene expression. Several TR isoforms exist, and studies of null mice have identified some unique functions for individual TR variants, although considerable redundancy occurs, raising questions about the specificity of T3 action. Thus, it is not known how diverse T3 actions are regulated in target tissues that express multiple receptor variants. I have identified two novel TRβ isoforms that are expressed widely and result from alternative mRNA splicing. TRβ3 is a 44.6-kDa protein that contains an unique 23-amino-acid N terminus and acts as a functional receptor. TRΔβ3 is a 32.8-kDa protein that lacks a DNA binding domain but retains ligand binding activity and is a potent dominant-negative antagonist. The relative concentrations of β3 and Δβ3 mRNAs vary between tissues and with changes in thyroid status, indicating that alternative splicing is tissue specific and T3 regulated. These data provide novel insights into the mechanisms of T3 action and define a new level of specificity that may regulate thyroid status in tissue.

The actions of thyroid hormone, 3,5,3′-l-triiodothyronine (T3), are mediated by ligand-inducible transcription factors that are members of the steroid/thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Two T3 receptor (TR) genes, TRα (NR1A1) and TRβ(NR1A2), are conserved in vertebrates (32, 43), while two TRα and two TRβ genes have arisen by gene duplication in Xenopus laevis (65). TRα encodes three C-terminal variants in mammals: α1 (NR1A1a) binds T3 and DNA and is a functional receptor, whereas α2 (NR1A1b) and α3 (NR1A1c) do not bind T3 and are weak dominant negative antagonists in vitro, although their roles in vivo are unclear (33, 40, 50, 57). Recent studies have described a promoter in intron 7 of TRα, which generates two truncated variants, Δα1 and Δα2, that are repressors in vitro but are of unknown physiological significance (9). In contrast, TRβ encodes two N-terminal variants, β1 (NR1A2a) and β2 (NR1A2b), which are transcribed from separate promoters (24, 28, 42, 61). The β1 N terminus is encoded by two exons that are replaced by a single exon in β2. These exons are alternatively spliced to six common exons that encode the DNA binding, ligand binding, and dimerization domains of the receptor (32). This arrangement is conserved in vertebrates, and the invariant splice site between the divergent N termini and the first of the common exons is known as the changing point (65). The changing point is retained in both Xenopus TRβ genes, although additional splicing in the 5′ untranslated region (5′-UTR) results in many transcripts that are temporo-spatially restricted during development (51, 64). TRβ0 is expressed in chicken; it contains only 2 amino acids proximal to the changing point and is similar to a short TRβ in Xenopus, although a mammalian homologue has not been identified (18, 52, 65). T3-regulated development in chicken also involves temporo-spatially regulated expression of TRβ but not of TRα (18).

The actions of T3 are diverse, providing important signals for nervous system, inner ear, muscle, heart, and skeletal development in mammals and for amphibian metamorphosis. T3 is a key regulator of postnatal growth, when it is essential for endochondral bone formation, and is the major regulator of the basal metabolic rate during adulthood, when it also influences cholesterol homeostasis, myocardial contractility, and maintenance of bone mass. Accordingly, TR mRNAs are widely expressed, but there are differences in concentrations of the isoforms in individual tissues (32). In particular, TRβ2 is largely restricted to the anterior pituitary and hypothalamus (24), where it mediates feedback regulation of the hypothalamo-pituitary-thyroid axis (1). It has, however, been difficult to ascribe specific functions to other TR variants, which do not display such restricted patterns of expression. TRα and TRβ each bind T3 with high affinity and recognize identical thyroid hormone response element (TRE) DNA binding sites (22, 32), but some studies have suggested that α and β receptors may show preferential activation of certain target genes (14, 35, 53, 66). The emergence of synthetic ligands that display selective affinities for TR subtypes may help to clarify this issue (10).

Gene-targeting studies to delete either TRα or TRβ (17, 19), creating α/β double-knockout mice (21), α1/β null mice (23), or mice lacking only the α1 (58) or β2 (1) isoforms, have shown considerable redundancy among the various TRs, indicating that loss of one variant can be overcome by the activities of other isoforms in many tissues. These studies, however, showed a discrete role for TRβ1 in the development of auditory function (1, 16); implicated TRα in maintaining thyroid hormone production, development of the small intestine and skeleton (21, 45), and maturation of B-lymphocyte populations (2); and implicated α1 in control of basal heart rate and body temperature (25, 26, 58). Despite this, data from biochemical studies and studies with TR-null mice do not account fully for the diversity and specificity of T3 action and have suggested an additional hormone-independent role for TRs (23).

In earlier studies to examine the action of T3 in osteoblasts, we identified a new 7.0-kb TRβ mRNA (59). The conserved structure of TRβ in all vertebrates, and the lack of C-terminal variants in any species, led to the hypothesis that this transcript may encode a novel N-terminal isoform, and a strategy involving 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′-RACE) was adopted to test it, using an osteoblast cDNA library. These studies report the characterization of two new TRβ isoforms, which are generated by alternative mRNA splicing and are expressed in tissue-specific patterns which alter with changes in thyroid status. TRβ3 is a novel receptor, and TRΔβ3 is a potent dominant negative antagonist that binds T3 with high affinity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and animals.

Pituitary GH3 and ROS 17/2.8, UMR 106, and ROS 25/1 osteosarcoma cells were cultured in Ham's F12 medium plus 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), and COS-7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 5% FCS. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (6 weeks old) were treated for 6 weeks with saline or T4 (50 μg/kg/day) and thyroidectomized rats were given saline to form euthyroid (n = 7), thyrotoxic (n = 8), and hypothyroid (n = 7) groups, respectively. All rats were fed a normal diet, and thyroidectomized animals received Ca2+ lactate supplements to drinking water. Studies were performed under licence in compliance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and were approved by the Imperial College School of Medicine Biological Services Unit ethical review. Plasma T4 concentrations (euthyroid animals, 0.79 ± 0.09 ng/ml: hypothyroid animals 0.06 ± 0.05 ng/ml; thyrotoxic animals, 0.97 ± 0.20 ng/ml) were determined by an immunoradiometric assay (Euro/DPC Ltd., Caernarfon, Gwynedd, Wales), and plasma TSH concentrations (euthyroid animals, 2.7 ± 0.4 ng/ml; hypothyroid animals, 114 ± 22 ng/ml; thyrotoxic animals, 1.2 ± 0.2 ng/ml) were measured using reagents from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Hormone and Pituitary Program (A. Parlow, Harbor University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles, Calif.) as described previously (55).

Accession numbers and primers. All primers were derived from published GenBank sequences (nucleotide positions are given in the 5′-3′ direction of the synthesized oligonucleotide): TRβ1, forward primers B1F1 (nucleotides 324 to 345) and B1F2 (nucleotides 374 to 396) (GenBank accession no. J03819); TRβ2, forward primers B2F1 (nucleotides 348 to 369) and B2F2 (nucleotides 404 to 426) (M25071); common TRβ, forward primers EcoTRBF1 [(Eco)533 to 549] and EcoTRBF2 [(Eco)767 to 783] and reverse primers BR1 (nucleotides 560 to 539), BR2 (nucleotides 633 to 604), BR3 (nucleotides 717 to 695), and BR4 (nucleotides 743 to 721) (J03819); TRβ3/Δβ3 exon A; forward primers EcoAF [(Eco) 1 to 16], AF1 (nucleotides 39 to 60), AF2 (nucleotides 71 to 92), and AF3 (nucleotides 311 to 332), reverse primers AR1 (nucleotides 163 to 142) and AR2 (nucleotides 301 to 280) (AF239914); TRΔβ3 exon A-changing point, reverse primers BAR1 (nucleotides 538 to 538 [J03819] and 342 to 327 [AF239914]); TRβ3 Exon B, forward primers EcoBF1 [(Eco)343 to 359; Eco refers to an EcoRI restriction site at the end of the primer] and EcoBF2 [(Eco) 588 to 604] (AF239915).

5′-RACE and inverse RT-PCR.

UMR106 and GH3 adapter-ligated cDNA libraries were constructed from poly(A)+ mRNA (Marathon cDNA synthesis; Clontech), and 5′-RACE was performed to identify TRβ variants using primers BR2 and BR1 and Marathon adapter primers, AP1 and AP2. TRβ3 contained two exons (A and B), and TRΔβ3 contained only exon A (see Fig. 2). The 5′ boundary of exon A was mapped by inverse reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). cDNA was synthesized from ROS 25/1, UMR 106, and ROS 17/2.8 poly(A)+ RNA (4.5 μg) using 10 μM BR1 with 5× buffer (250 mM Tris [pH 8.3], 30 mM MgCl2, 375 mM KCl), 1 nM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) and Moloney murine leukemia virus MMLV reverse transcriptase (20 U) in 10 μl at 42°C for 1 h. Second-strand cDNA was synthesized with 10 nM dNTPs, 5× buffer (250 mM Tris [pH 7.8], 50 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol DTT, 5 mM ATP, 25% polyethylene glycol 8000) and 20× enzymes (E. coli DNA polymerase I, 6 U/μl; DNA ligase, 1.2 U/μl; RNase H, 0.25 U/μl) in 80 μl at 16°C for 90 min (all reagents from Clontech). A 2-μl volume of T4 DNA polymerase was added for 45 min at 16°C to blunt the cDNA, which was self-ligated, cut with PstI, amplified with AR1 and AF3, and sequenced.

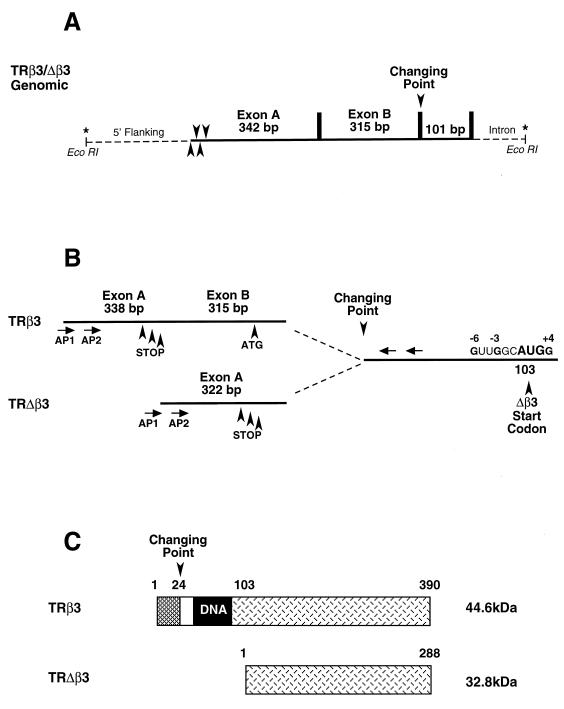

FIG. 2.

(A) The 4.5-kb EcoRI genomic fragment containing the β3 and Δβ3 locus. Exons A (342 bp) and B (315 bp) are in continuity with the 101-bp first common TRβ exon. Noncoding sequence is shown as dotted lines, intron/exon boundaries are shown by vertical bars and the exon A 5′ boundary is shown by four arrowheads representing a 20-bp region mapped by 5′-RACE and inverse RT-PCR. The changing-point splice site precedes the first common exon. Asterisks mark each end of the 4.5-kb fragment and are shown in panel D to indicate the location of this clone within the complete TRβ gene. (B) Novel cDNA clones obtained by 5′-RACE from a UMR 106 library. TRβ3 contains exons A and B; in TRΔβ3, exon B is skipped and exon A splices to the changing point. AP1 and AP2 are forward primers complementary to adapters used in library construction. Arrows show locations of the reverse primers used for 5′-RACE. Arrowheads below exon A indicate stop codons in each reading frame, and the arrow below exon B show an ORF in continuity with the rest of TRβ. The sequence at amino acid 103 in TRβ3 shows the next in-frame AUG codon within a Kozak consensus sequence and represents the Δβ3 initiation codon. (C) TRβ3 and Δβ3 predicted proteins of 390 amino acids (44.6 kDa) and 288 amino acids (32.8 kDa). β3 contains a 23-amino-acid N terminus encoded by exon B; Δβ3 lacks a DNA binding domain and results from translation initiated at the downstream AUG codon. (D) Structural arrangement of the TRβ gene as deduced from published data from Xenopus (51, 65), human (3, 48), and mouse (18, 21, 61) TRβ genes and from data obtained in this study with rats. Exons are shown in the upper part of the diagram as solid lines and as shaded boxes beneath; introns are shown as dotted lines and below as thin continuous lines. In the lower part, promoter regions for β1, β2, and β3/Δβ3 are shown as thick solid lines, and the cross lines flanking the β2 region indicate that the relative positions of the β1 and β2 loci have not been determined in any species. Asterisks indicate the location of the 4.5-kb rat genomic fragment shown in panel A and cloned in this study. The common coding exons 3 to 8 lie 3′ to the changing-point splice site, contain the DNA and ligand binding domains of TRβ, and are designated according to the published nomenclature for mouse TRβ1 (18, 21), which corresponds to exons 5 to 10 in human TRβ (3) and differs from that previously reported for mouse TRβ2 (61) and Xenopus (51, 65).

Northern blotting.

UMR 106 and GH3 poly(A)+ blots were probed at 65°C in 50% formamide–5× SSPE (20× SSPE is 175.3 g of NaCl per liter, 27.6 g of NaH2PO4 · H2O per liter, and 7.4 g EDTA per liter)–0.15 M Tris (pH 8.0)–1% sodium dodecyl sulfate–(SDS) 5× Denhardt's solution (50× is 10 g of Ficoll 400 per liter, 10 g of polyvinylpyrrolidone per liter, 10 g of bovine serum albumin per liter)–100 μg of salmon sperm DNA per ml with a TRβ1 riboprobe, transcribed from XhoI-linearized pBS62 (28) using T7 RNA polymerase, and washed in 0.1× SSC (1× is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% SDS at 75°C for 1 h. Multiple tissue blots (Clontech) were hybridized at high stringency to β3- and Δβ3-specific riboprobes (generated by primers EcoBF1 plus BR1 and EcoAF plus BR1, respectively), washed in 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS at 65°C for 30 min, and autoradiographed for 14 days. Multiple tissue blots were also hybridized to specific TRβ1 (EcoRI-XbaI fragment excised from pBS62), TRβ2 (EcoRI-SacI fragment from pSG5hTRβ2), common TRα1/α2 (EcoRI-XbaI fragment from pBSmTRα1), and full-length human actin cDNA probes in ExpressHyb (Clontech) hybridization buffer for 1 h at 68°C, washed in 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS at 50°C for 1 h, exposed overnight, and analyzed with a Molecular Dynamics 445 SI PhosphorImager (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech) using Molecular Dynamics ImageQuant v1.2 software.

RT-PCR.

DNase I-digested RNA (8 μg) was reverse transcribed at 42°C for 30 min using primer BR4 (50 pmol/μl), random hexamers (0.016 unit of absorbance at 260 nm; Amersham-Pharmacia), RNase inhibitor (20 U, Gibco), dNTPs (0.8 mM each), avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (10 U; NBL Gene Sciences), and RT buffer in 20 μl. A 5-μl volume of template, containing dNTPs, was amplified with 50 pmol of BR4 and forward primer (B1F1 for β1, B2F1 for β2, and AF1 for β3 and Δβ3) per μl, 1.2 μl of Taq DNA polymerase/TaqStart antibody mix (Clontech), PCR buffer (Gibco), and 1.5 mM MgCl2 in 25 μl. After denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, 25 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min were followed by a 5-min extension. A total of 25 cycles of nested PCR were performed with 1 μl of template, 0.2 mM (each) dNTPs, 50 pmol of BR3 and forward primer (B1F2, B2F2, or AF2) per μl, 1.2 μl of Taq polymerase/TaqStart mix, PCR buffer, and 1.5 mM MgCl2 in 25 μl. Products were purified and sequenced. Semiquantitative RT-PCR was optimized to detect linear accumulation of TRβ3 and Δβ3. A range of input RNA concentrations (2 to 16 μg) was tested over a range of PCR cycles (20 or 25 cycles for the initial PCR followed by 20, 23, 25, 27, 30, 35, and 40 nested cycles) in tissues that expressed TRβ3 (heart), Δβ3 (spleen), or both mRNAs equally (kidney). The products were Southern blotted, probed with AR2, and the results showed linear accumulation of β3 and/or Δβ3 cDNA in each tissue with 8 μg of RNA and 25 initial and nested PCR cycles (data not shown).

Southern blotting.

Genomic DNA was prepared from normal rat liver, ROS 25/1, UMR 106, and ROS 17/2.8 cells, digested with EcoRI, HindIII, PstI, and BamHI, and Southern blotted. Duplicate filters were hybridized to an exon A probe, amplified using primers AF1 and BAR1 and a TRβ1-specific probe, obtained by EcoRI and XbaI digestion of pBS62, and washed (0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS) at 65°C for 1 h.

Genomic library.

A total of 1.2 × 106 recombinant phages from a λDASH rat genomic library were screened. Duplicate filters were hybridized to the exon A probe and washed to a final stringency of 3× SSC–0.1% SDS at 65°C for 15 min. Five positive plaques were replated and screened twice, and three independent identical clones (λ4, λ12, and λ16), containing inserts of approximately 16 kb, were isolated. Clone λ4 was digested, Southern blotted, and hybridized to the exon A probe. A 4.5-kb EcoRI fragment was isolated, subcloned, and analyzed.

DNA constructs and in vitro transcription-translation.

Full-length TRβ3 and Δβ3 cDNAs were constructed using the XbaI site in TRβ1 (pBS62) (28) and inserted into pBSKS(+) (Stratagene). Then 5′ deletions were made to optimize in vitro transcription-translation. Primers EcoBF1, EcoBF2, EcoTRBF1, or EcoTRBF2 were used with BR1 to create β3 constructs that lacked exon A or its entire 5′ UTR and Δβ3 constructs that lacked exon B or its 5′ UTR. TRβ3 and Δβ3 were subcloned into pCDM8 (Invitrogen) for transfections. Site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange; Stratagene) was performed in β1, β3, and Δβ3 to alter the Δβ3 translation initiation codon to CTG. Both strands of all constructs were sequenced (Thermo-Sequenase I; Amersham) using an ABI 373A apparatus (Applied Biosystems). Transcription-translation (Promega) was performed using pBS62, pBSβ3, pBSΔβ3, pBShRXRα (36), and pBSmTRα1 (46) with T3 polymerase and pSG5hTRβ2 (31) with T7 polymerase. Products were separated on a Sephadex G-50 (Pharmacia) column in 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.8)–50 mM NaCl.

Expression of TR and RXRα fusion proteins.

TRβ1, TRβ3, and TRΔβ3 were subcloned into pCAL-n (Stratagene) to express calmodulin binding-peptide fusion proteins in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysS. Cultures, containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml plus 34 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, were induced at log phase by using 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 30°C for 3 h. Bacteria were resuspended in GTM 375 (15% glycerol, 25 mM Tris [pH 7.8], 375 mM KCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride)–0.05% Triton X-100–2 mM CaCl2 and sonicated. The sonicates were pelleted at 1,100 × g, and the supernatants were agitated for 90 min at 4°C with 1 ml of calmodulin resin in 1 ml of GTM 375–0.05% Triton X-100–2 mM CaCl2. The resin was packed into a 0.5-ml column and washed with 10 ml of GTM 375–0.05% Triton X-100–2 mM CaCl2 at 4°C. CAL-TR fusion protein was eluted with 2.5 ml of GTM 375–0.05% Triton X-100–2 mM EGTA at 4°C and stored at −80°C. RXR was expressed from pQEhRXRα as described previously (67). TR fusion proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using a monoclonal antibody (MA1-215; Affinity Bioreagents Inc.) against amino acids 235 to 414 of TRβ1 (4) and enhanced chemiluminescence detection (Amersham-Pharmacia).

Gel shifts.

DNA binding properties of TRβ3 and TRΔβ3 were determined using a synthetic DR+4 TRE (56). Receptors were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, followed by 10 min at 4°C, with 32P-labeled DR+4 (15,000 cpm), 100 ng of poly(dl-dC) (Amersham-Pharmacia), and 5 μg of bovine serum albumin with or without unlabeled competitor oligonucleotide (DR+4, nonspecific γ-globin promoter sequence [12], or mutated DR+4 [MUT] containing single G-to-A mutations in each half-site) in a 30-μl reaction mixture containing final concentrations of 10% glycerol, 25 mM Tris (pH 7.8), 500 μM EDTA, 90 mM KCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.05% Triton X-100. The reaction products were resolved by nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (5% polyacrylamide) in low-ionic-strength mobility shift buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, 7.5 mM glacial acetic acid, 40 μM EDTA), as described previously (60).

Ligand binding.

The T3 binding affinities of CAL-β1, CAL-β3, and CAL-Δβ3 proteins were determined by saturation and competition binding with minor adaptations to published methods (28, 42). The receptor was incubated with 0.01 to 5 nM [125l]T3 (2,200 Ci/mmol; NEN) with or without unlabeled T3 (500 nM) to determine specific binding at each concentration in saturation binding studies. The receptor was incubated with 30,000 cpm of [125l]T3 in the presence of 0.01 to 3.2 nM unlabeled T3 in competition studies, and 100 nM T3 was used to determine nonspecific binding. Reactions were performed in 100 μl of GTME 400 (15% glycerol, 25 mM Tris [pH 7.8], 500 μM EDTA, 400 mM KCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) plus 0.0025% Triton X-100, and the mixtures were incubated for 30 min at room temperature and 4 h at 4°C. Bound T3 was separated on a Sephadex G-25 (fine) column, equilibrated in GTME 400, eluted with 2 column volumes of GTME 400–0.0025% Triton X-100, and quantified by γ-scintillation counting. Data were analyzed by nonlinear regression, and binding constants were calculated using GraphPad Prism software.

Transfections.

COS-7 cells were seeded in six-well plates (105 cells/well) containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium–5% charcoal-stripped FCS (CSS medium) (49) and transferred to serum-free medium for transfection with Lipofectamine PLUS (Gibco) as follows: 500 ng of luciferase reporter driven by a thymidine kinase (Tk) promoter controlled by TREs from the rat malic enzyme or α-myosin heavy-chain genes (59) or by two copies of a palindromic TRE (54); 40 to 200 ng of TR plasmid (β1, β3, or Δβ3 in pCDM8 or α2 in pRSV) (47); and 100 ng of Renilla internal control reporter (Promega) and pCDM8 carrier DNA to a total of 1.5 μg of DNA per well. After 3 h, 1 ml of 10% CSS medium was added and the cells were incubated for 24 h. The contents of each transfected well were split into four in a 24-well plate containing 5% CSS medium with or without T3 (10 nM) and incubated for 48 h. Reporter gene activities were determined using a dual luciferase assay (Promega), and luciferase was normalized to Renilla prior to calculation of T3 induction ratios.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Rat TRΔβ3 and TRβ3 mRNA and genomic sequences were submitted to DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession numbers AF239914, AF239915, and AF239916.

RESULTS

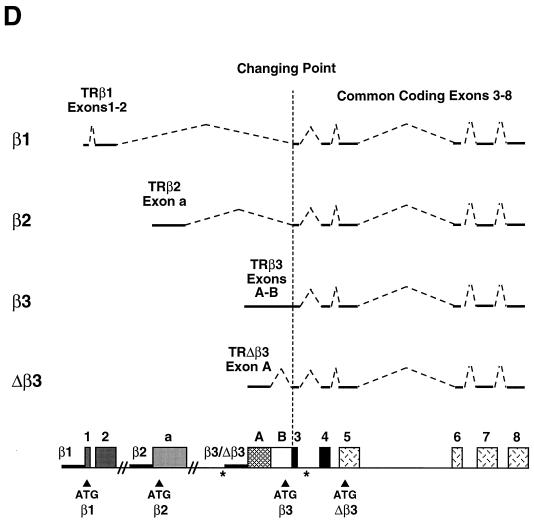

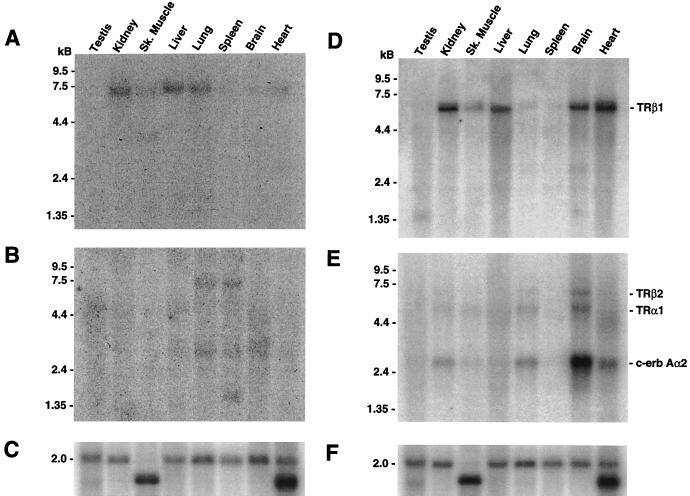

A novel 7.0-kb TRβ mRNA was identified previously in UMR 106 cells (59). This transcript was expressed with a 6.2-kb TRβ1 mRNA in osteoblastic cells but was found to be absent from GH3 cells (Fig. 1A), which express separate 6.2-kb mRNAs encoding TRβ1 and TRβ2 (24). Southern blotting of normal liver and osteosarcoma cell DNA indicated that no major rearrangements of the TRβ genomic locus occurred in osteosarcoma cells that might generate an abnormal transcript (Fig. 1B). Alternative splicing of TRβ mRNA occurs only proximal to the changing point (32, 51, 64), and therefore, 5′-RACE was employed to isolate novel TRβ isoforms from UMR 106 and GH3 cDNA libraries.

FIG. 1.

(A) Northern blot of pituitary GH3 and osteosarcoma UMR 106 cell poly(A)+ mRNA (5 μg, duplicate lanes) hybridized to a TRβ1 cRNA. A 6.2-kb mRNA is present in both cell types, and a 7.0-kb mRNA is present only in UMR 106 cells. (B) Southern blot of normal liver (N) and ROS 17/2.8, ROS 25/1, and UMR 106 osteosarcoma cell (lanes 17, 25, and U) genomic DNA, digested with EcoRI, HindIII, PstI, and BamHI and probed with TRβ1 (top) and exon A (bottom) probes.

Only TRβ and TRβ2 were isolated from the GH3 library (data not shown). Three cDNA populations were identified in UMR 106 cells by sequencing of individual 5′-RACE clones; one population contained TRβ1, the other two were novel, and TRβ2 was not isolated. The shorter novel cDNA contained a 322-bp sequence (exon A) that joined the changing point (Fig. 2B). The longer cDNA contained a 653-bp sequence that included a new 315-bp sequence (exon B), which separated exon A from the changing point, and a further 16 proximal nucleotides that extended exon A to 338 bp (Fig. 2B). Sequencing revealed stop codons in all three reading frames of exon A, indicating that it is noncoding and forms a 5′-UTR. The 315-bp exon B consists of 245 bp of 5′-UTR that is continuous with exon A, followed by a 70-bp open reading frame (ORF) in continuity with the remainder of TRβ.

Thus, the longer cDNA containing exons A and B was designated TRβ3 and consisted of a 583-bp 5′-UTR with a 70-bp ORF spliced onto the six exons that encode DNA and ligand binding domains common to all TRβ isoforms (common exons 3 to 8 in Fig. 2D). Its 5′-UTR contains five overlapping ORFs encoding 5 to 60 amino acids, proximal to the ORF encoding TRβ3. The 70-bp in-frame ORF encodes a 23-amino-acid N terminus that replaces the A and B regions of β1 or β2. Database homology searches revealed no matches with known proteins or motifs. The predicted TRβ3 protein contains 390 amino acids with a molecular mass of 44.6 kDa (Fig. 2C).

The shorter cDNA that lacked exon B was designated TRΔβ3 and is predicted to direct translation from the next in-frame ATG codon, located at amino acid 174 of TRβ1 (28) (position 103 in β3) and situated within a consensus Kozak translation initiation sequence (30) (Fig. 2B and D). The Δβ3 cDNA contained a 458-bp 5′-UTR derived from exon A and 136 bp of common TRβ sequence that precedes the next in-frame ATG codon described above (Fig. 2B and D). The 5′-UTR contained six overlapping ORFs encoding 4 to 60 amino acids, proximal to the predicted coding region. The predicted TRΔβ3 protein contains 288 amino acids with a molecular mass of 32.8 kDa (Fig. 2C). The 5′ terminus of exon A was also determined independently, by inverse RT-PCR, in three populations of correctly spliced clones. The largest clone extended exon A by 4 nucleotides to 342 bp, and other populations contained mRNAs in which exon A was 338 or 325 bp long. These findings agree with the results obtained with RACE clones that contained exon A sequences of 322 and 338 bp and map the 5′ mRNA boundary to a 20-bp region (Fig. 2A). Additional RT-PCR studies established that exons A and/or B were not spliced between TRβ1 or TRβ2-proximal exons and the changing point and vice versa (data not shown).

A 16-kB genomic clone was isolated, from which a 4.5-kb subclone was characterized and found to contain 886 bp of 5′-flanking sequence, exon A, exon B, the 101-bp common TRβ exon beginning at the changing point, and a 3′ intron of at least 2.8 kb (Fig. 2A and D). The 16-kb clone did not contain TRβ1- or TRβ2-proximal exons, indicating that the β3/Δβ3 locus is in continuity with the common TRβ exon and located between the β1 and β2 loci and the changing point (Fig. 2D). Database searching revealed that the 5′-flanking region contains numerous possible binding sites for a variety of transcription factors, including Pit-1, Sp-1, Oct-1, and C-EBP, but lacks a TATA box upstream of the exon A transcription start site (data not shown). No sequence homologies to exon A and exon B 5′-UTRs were identified. However, the 70-bp ORF in exon B was 80 to 93% homologous to the 58 published nucleotides of the intron which precedes the changing point in the mouse TRβ gene (61). This 58-bp region begins with an ATG triplet and contains an in-frame ORF whose product has 70% amino acid identity to the 23-amino-acid N terminus of rat TRβ3. The homologous region in the human TRβ gene remains unpublished. The splice site between exons A and B consists of the exact metazoan 5′ RNA splice site consensus sequence, A(G/G)UAAGU (8). These analyses support the finding that exon B is transcribed in TRβ3 mRNA but excised during Δβ3 mRNA processing, and they indicate that the TRβ locus in this region is conserved between the rat and the mouse. Taken together with data that map the 5′-UTR of exon A to a 20-bp region, these findings suggest that TRβ3 and TRΔβ3 originate from a third TRβ promoter.

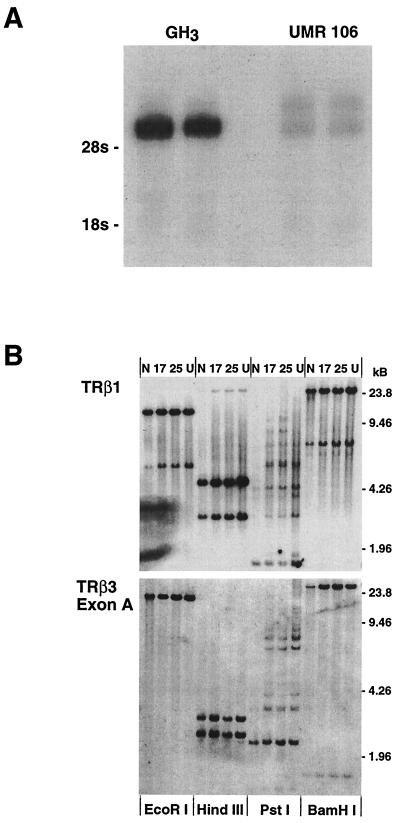

To determine whether exon B was retained in mature mRNA or whether its presence indicated the presence of unspliced RNA, an RT-PCR assay was designed using a reverse primer from the second common TRβ exon and a forward primer from exon A. The resulting products crossed splice sites between the two common DNA binding domain exons, at the changing point, and between exons A and B. The cDNAs generated in this assay were correctly spliced, indicating that β3 and Δβ3 mRNAs are mature transcripts. Expression of β3 and Δβ3 mRNAs differed between tissues; Δβ3 alone was expressed in the spleen, only β3 was present in the heart and both were identified in the kidneys, suggesting that the relative expression of the transcripts may be tissue specific (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR using forward primers from exon A (common to β3 and Δβ3) and TRβ reverse primers (from the second common TRβ exon) to show β3 (767 bp) and Δβ3 (452 bp) mRNA expression in the spleen, heart, and kidneys. Genomic DNA, H2O, or RNA template lacking reverse transcriptase (−) negative controls confirm that expression is dependent on RT (+) and processing of the primary transcript.

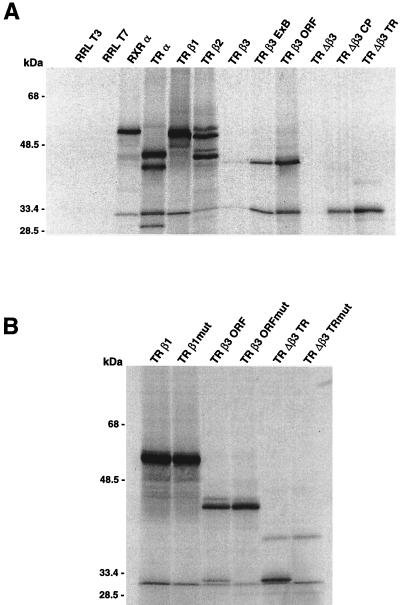

Multiple-tissue Northern blots were hybridized to TRβ3 and TRΔβ3 probes to determine their tissue distribution. Both isoforms were expressed at low levels. TRβ3 was expressed widely as a 7.0-kb mRNA and was relatively abundant in the liver, kidneys, and lungs compared to other tissues; was present at lower levels in the skeletal muscle, heart, spleen, and brain; but was absent from the testes. A second, 4.0-kb transcript was expressed in skeletal muscle (Fig. 4A). A 7.0-kb Δβ3 mRNA was expressed in the spleen and lungs and was present at very low levels in the brain but was undetectable in other tissues. Additional Δβ3 mRNAs of 3.0 kb in the spleen, lungs, and brain and of 1.5 kb in the spleen were observed (Fig. 4B). Thus, both β3 and Δβ3 are encoded by 7.0-kb mRNAs, which were not resolved by Northern blotting and are of identical size to the transcript first identified in UMR 106 cells. For comparison, multiple tissue blots were also hybridized to probes that detected each of the other TRβ and TRα mRNA isoforms (Fig. 4D and E). The 6.2-kb TRβ1 mRNA was expressed predominantly in the kidney, liver, brain, and heart, was less prominent in skeletal muscle, and was just detectable in the lungs and spleen but was absent from the testes. The 6.2-kb TRβ2 mRNA was largely restricted to the brain, since expression was barely detectable in the lungs and heart and was absent from other tissues. TRα1 and TRα2 mRNAs were detected at the highest levels in the brain and at lower levels in the kidneys, skeletal muscle, lungs, and heart. TRα1 and TRα2 transcripts were barely detectable in the testes and liver and were absent from the spleen. Thus, the patterns of expression of the TRβ3 and TRΔβ3 mRNAs were different from those of the TRα1, TRα2, TRβ1, and TRβ2 isoforms and varied between tissues.

FIG. 4.

(A) Multiple-tissue Northern blot hybridized to a β3-specific exon B probe. A 7.0-kb mRNA is predominant in the kidneys, liver and lungs, expressed at lower levels in the skeletal muscle, spleen, brain, and heart, and absent from the testes. An additional 4.0-kb mRNA is restricted to skeletal muscle. (B) The same blot hybridized to a Δβ3 probe at high stringency. A 7.0-kb mRNA predominates in the lungs and spleen and is present at low levels in the brain. A 3.0-kb mRNA is present in the same tissues, and a 1.5-kb transcript is evident in the spleen. (C) The same blot hybridized to a β-actin cDNA to show that similar amounts of intact RNA are loaded in each lane. (D) Multiple-tissue Northern blot hybridized to a β1-specific probe. A 6.2-kb mRNA is predominant in the kidneys, liver, brain, and heart, expressed at lower levels in the skeletal muscle, just detectable in the lungs and spleen, and absent from the testes. (E) The same blot hybridized to β2- and α1/α2-specific probes. A 6.2-kb β2 mRNA is clearly expressed in the brain and is just detectable in the lungs and heart but absent from other tissues. The 5.5- and 2.6-kb TRα1 and TRα2 transcripts were expressed at the highest levels in the brain and at lower levels in the kidneys, skeletal muscle, lungs, and heart, were barely detectable in the testes and liver, and were absent from the spleen. (F) Same blot as in panels D and E hybridized to a β-actin cDNA.

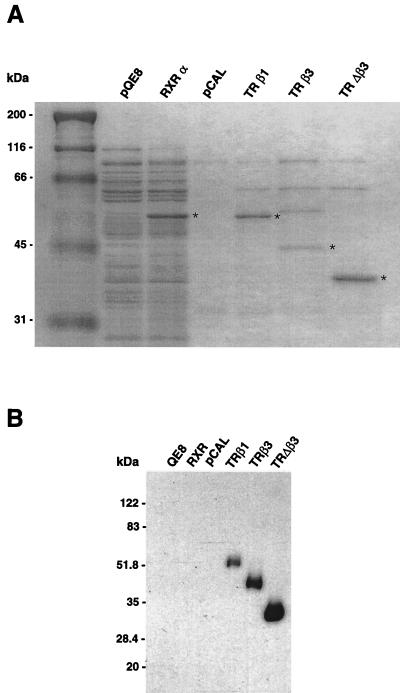

In vitro transcription-translation of β3 and Δβ3 cDNAs generated proteins migrating at 45 and 32.5 kDa (Fig. 5A), in agreement with calculated molecular masses of 44.6 and 32.8 kDa. Truncation of the 5′-UTR up to the exon A/B junction or initiation codon in β3 and to the changing point or putative initiation codon in Δβ3 increased translation efficiency. Site-directed mutagenesis of the ATG at position 174 in TRβ1, position 103 in TRβ3, and position 1 in TRΔβ3 was performed to determine whether Δβ3 was translated from the predicted initiation site and to examine whether the codon was used in β1 or β3 mRNAs. Transcription-translation of the mutants resulted in loss of the 32.5 kDa protein compared to the wild type in both β3 and Δβ3 (Fig. 5B). Accordingly, translation of full-length TRβ3 was more efficient in the mutant than in the wild type. Thus, the TRΔβ3 mRNA encodes the predicted 288-amino-acid protein that lacks a DNA binding domain. Furthermore, the codon at position 103 was used to initiate translation of Δβ3 from the TRβ3 mRNA, which thus encodes two proteins in vitro. Use of the codon in β1 was barely detectable, indicating that no significant translation occurs from this site in TRβ1 mRNA.

FIG. 5.

(A) [35S]methionine-labeled RXRα and TR isoforms, with controls containing unprogrammed lysate incubated with T3 or T7 polymerase (RRL). β3 products were derived from full-length cDNA and constructs lacking exon A (TRβ3ExB) or the 5′-UTR (TRβ3ORF); Δβ3 products were derived from full-length cDNA and constructs lacking exon A (TRΔβ3CP) or the 5′-UTR (TRΔβ3TR). The 32.5-kDa Δβ3 product consists of two proteins, resolved after further electrophoresis. (B) Products from wild-type TRβ1, TRβ3, and TRΔβ3 cDNAs and constructs in which the AUG codon at position 174 in β1, 103 in β3, and 1 in Δβ3 was mutated to CTG (TRβ1mut, TRβ3ORFmut, and TRΔβ3TRmut).

TRβ3, TRΔβ3, and TRβ1 fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli. Partially purified receptors were analyzed by Coomassie blue staining and Western blotting to confirm that full-length proteins were expressed (Fig. 6). T3 binding affinities were determined in saturation and competition assays, and the binding constants derived from the two methods were in close agreement. Thus, β3 (KD = 0.63 ± 0.13 nM) and Δβ3 (KD = 0.51 ± 0.09 nM) bound T3 with high affinity, similar to β1 (KD = 0.49 ± 0.10 nM) and in agreement with published data (28). E. coli extracts transformed with empty vector did not bind T3.

FIG. 6.

(A) Coomassie blue-stained extracts from E. coli programmed with empty vector (pQE8 or pCAL) and receptor-expressing plasmids (RXRα, TRβ1, TRβ3, and TRΔβ3). Expressed receptors were purified by Ni-nitrilotriacetate-agarose (pQE8 and RXRα) or calmodulin (pCAL and TRs) column chromatography. Asterisks show receptor fusion proteins of the appropriate sizes. (B) Western blotting with a monoclonal antibody to amino acids 235 to 414 of TRβ, showing expression of full-length β1, β3, and Δβ3 fusion proteins.

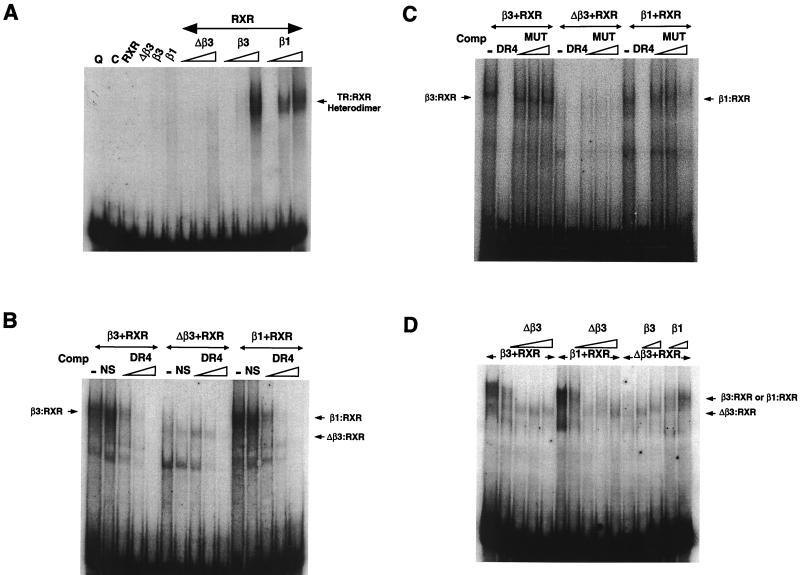

DNA binding was investigated by a gel shift assay using a DR+4 TRE (56). RXRα, TRβ3, TRΔβ3, and TRβ1 failed to bind DNA when incubated alone with the element. Coincubation of RXR with β3 or β1 resulted in binding of β3-RXR or β1-RXR heterodimers, whereas coincubation of RXR with identical concentrations of Δβ3 resulted in no binding (Fig. 7A). Addition of higher concentrations of Δβ3 resulted in binding of Δβ3-RXR complexes with greater mobility than β3 or β1 heterodimers (Fig. 7B and D and data not shown). β3, Δβ3, and β1 heterodimer binding was sequence specific since complexes were competed by 50- to 100-fold excesses of unlabeled DR+4 but not by nonspecific competitor (Fig. 7B). Specificity was further confirmed by incubation of heterodimer complexes with up to a 150-fold excess of an unlabeled mutated DR+4 element (MUT; containing two AGATCA half-sites in place of the wild-type sequence AGGTCA), which failed to compete with the wild-type DR+4 TRE for heterodimer binding (Fig. 7C). In contrast, coincubation of preformed β3-RXR or β1-RXR heterodimers with increasing concentrations of Δβ3 resulted in disruption of these complexes and formation of Δβ3-RXR heterodimers, indicating that Δβ3 competes efficiently with β3 or β1 for RXR. Reciprocal experiments demonstrated a less potent disruption of preformed Δβ3/RXR complexes by increasing concentrations of β3 or β1 (Fig. 7D).

FIG. 7.

(A) Gel shift assay showing QE8 and pCAL extracts and overexpressed RXRα, TRΔβ3, TRβ3, or TRβ1 (2 μl) incubated with 32P-labeled DR+4 in the first six lanes. The following lanes contain 2 μl of RXRα with increasing concentrations (0.2, 1, and 2 μl) of TRΔβ3, TRβ3, or TRβ1. The migration position of the β1-RXR and β3-RXR heterodimers is shown on the right. (B) Competition of TR-RXR complexes with a 100-fold excess of unlabeled nonspecific oligonucleotide (NS) or increasing excess (10-, 50-, and 100-fold) of unlabeled DR+4. The lanes contain 2 μl of RXRα coincubated with 2 μl of β3, 7.5 μl Δβ3, or 2 μl of β1. The migration positions of β3-RXR and β1-RXR heterodimers are shown on the left and right, respectively, and the position of faster-migrating Δβ3-RXR complexes in the middle lanes is shown on the right. (C) Competition of TR-RXR complexes with a 100-fold excess of unlabeled DR+4 or increasing excess (50-, 100-, and 150-fold) of unlabeled mutated DR+4 element (MUT). Lanes contain 1 μl of RXRα coincubated with 2 μl of β3, 4 μl of Δβ3, or 2 μl of β1. The migration positions of β3-RXR and β1-RXR heterodimers are shown on the left and right, respectively. Δβ3-RXR complexes form only weakly with this reduced concentration of receptor compared to panels B and D. (D) Coincubation of increasing concentrations of Δβ3 (1, 2, 5, and 10 μl) with preformed RXRα-β3 and RXRα-β1 heterodimers is shown in the first 10 lanes; the lanes contain 2 μl of RXRα plus 2 μl of TRβ3 or TRβ1. The effect of increasing concentrations of TRβ3 or TRβ1 (2 and 5 μl) on preformed RXRα-Δβ3 (2 μl of RXRα plus 7.5 μl of Δβ3) complexes is shown in the following lanes. The position of β3-RXR and β1-RXR heterodimers is shown on the right, and the position of faster-migrating Δβ3-RXR complexes is also shown.

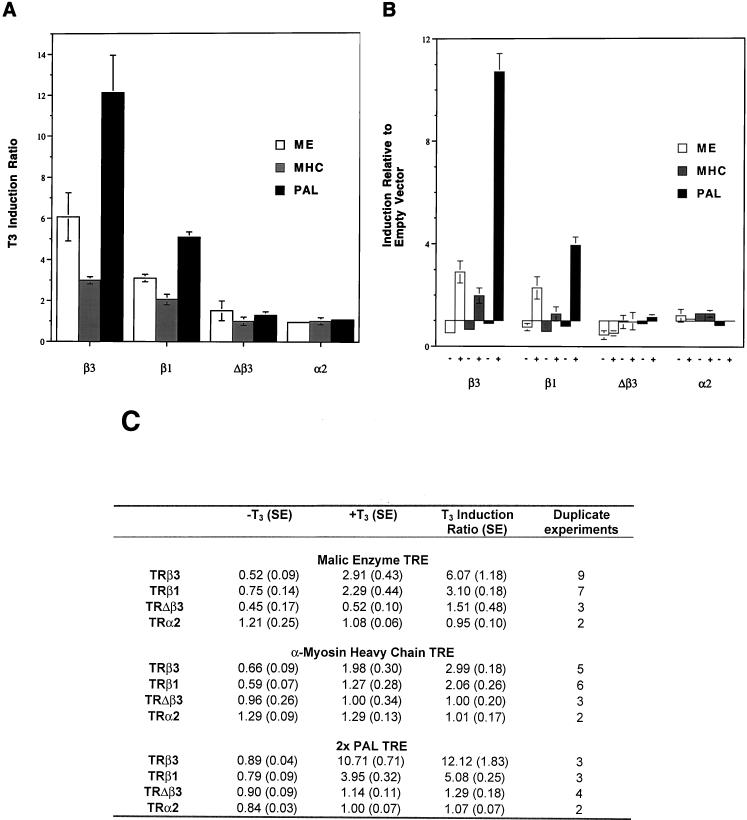

TRβ3, TRΔβ3, TRβ1, and TRα2, a well characterized weak dominant negative TRα isoform (47), were transfected with reporters driven by TREs from the α-myosin heavy chain (MHC) or malic enzyme (ME) genes (59) or by two copies of a palindromic element (PAL) (54) into COS-7 cells, which lack significant concentrations of functional endogenous TRs (28). TRβ3 was a twofold more potent activator of the ME TRE than was TRβ1. This increased potency resulted from greater repression of basal gene expression by unliganded β3 compared with β1, as well as from increased T3 activation (Fig. 8). On the MHC element, β3 was 1.5-fold more potent, because of increased gene activation rather than because of changes in basal expression. TRβ3 was a 2.4-fold more potent activator of the PAL TRE than was TRβ1, and this increased potency also resulted from increased gene activation rather than from differences in levels of basal expression. TRΔβ3 and TRα2 did not activate any of the three elements in response to T3, although Δβ3 acted as a potent repressor of the ME TRE by markedly inhibiting both basal and T3-activated expression (Fig. 8B and C). On the MHC and PAL TREs, Δβ3 did not influence basal expression or T3 activation.

FIG. 8.

COS-7 cells were transfected with TR (160 ng) or a luciferase reporter (500 ng) driven by the thymidine kinase promoter and controlled by either the ME or MHC gene TRE or a TRE containing two copies of PAL, an internal control Renilla reporter (100 ng) and pCDM8 carrier DNA (740 ng). (A) T3 induction of each TRE mediated by each receptor. Luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla to control for transfection efficiency, and the results are expressed as mean T3 induction ratio (with standard errors shown), calculated by dividing normalized luciferase activities following T3 treatment by basal values. (B) Induction of each TRE mediated by each receptor in the absence or presence of hormone. Luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla to control for transfection efficiency and the results shown as reporter gene activity in the absence (−) or presence (+) of T3 relative to the level of reporter gene activity under each condition in the absence of cotransfected receptor, which was normalized to a value of 1. Values below 1 in the absence of T3 indicate repression by unliganded receptor; values above 1 after addition of T3 indicate gene activation. (C) Complete data that were plotted in panels A and B, showing the values for mean basal (−T3) and T3-induced (+T3) luciferase/Renilla ratios as well as T3 induction ratios (standard errors are given). Basal and T3-induced values are relative to reporter gene activity in the absence of cotransfected receptor, which was normalized to a value of 1.

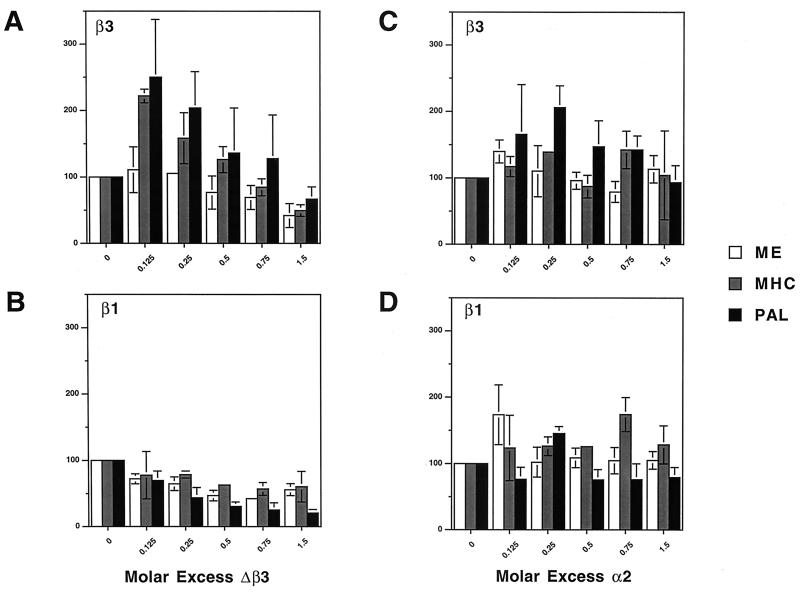

In cotransfections, TRΔβ3 inhibited β3 and β1 induction of the ME TRE by up to 58%. Similarly, Δβ3 inhibited β3 induction of the MHC TRE by 50% and inhibited β1 induction by up to 43%. Furthermore, Δβ3 inhibited β3 induction of the PAL TRE by up to 44% and inhibited β1 induction by up to 80%. In marked contrast, low concentrations of Δβ3 increased β3 induction of both the MHC and PAL TREs by more than twofold, but this effect was not seen on the ME TRE or for β1 induction of any of the three elements (Fig. 9A and B). TRα2 did not inhibit or consistently influence β1 or β3 induction of any of the three elements (Fig. 9C and D).

FIG. 9.

Effect of cotransfecting a relative molar amount (0.125- to 1.5-fold) of TRΔβ3 (A and B) or TRα2 (C and D) on TRβ3 (A and C) and TRβ1 (B and D)-mediated induction of ME, MHC, and PAL reporters. Cells were transfected with β3 or β1 (160 ng), Δβ3 or α2 (0 to 240 ng), ME, MHC, or PAL luciferase reporter (500 ng), Renilla internal control (100 ng), and pCDM8 carrier DNA to a constant amount of 1.5 μg. Graphs show T3 induction mediated by each receptor on each TRE in the absence and presence of Δβ3 or α2. Luciferase activities were normalized to Renilla, and the results are expressed as a percentage of the maximal T3 induction ratio, where mean induction in the absence of Δβ3 or α2 was normalized to 100% (means and standard errors for three determinations are shown).

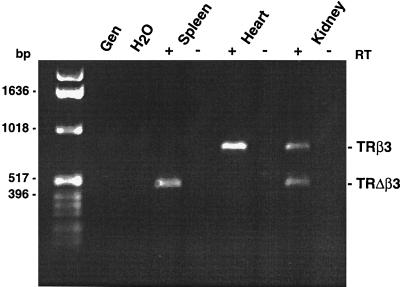

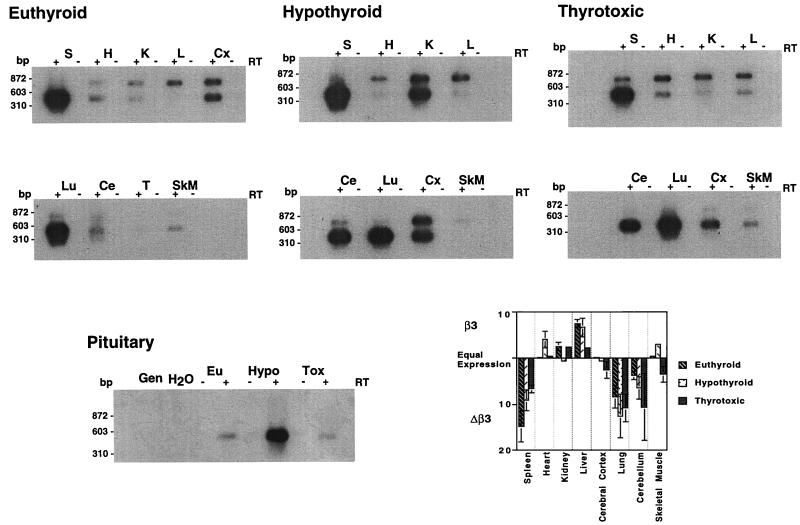

Since the activities of TRβ3 and TRΔβ3 differed and their mRNAs were expressed in tissue-specific patterns, semiquantitative RT-PCR was used to examine expression in euthyroid, hypothyroid, and thyrotoxic tissues. These studies confirmed that β3 and Δβ3 mRNAs were expressed in tissue-specific ratios (Fig. 10). For example, in euthyroid animals only β3 was expressed in the liver and only Δβ3 was present in the spleen, while both transcripts were expressed equally in the cerebral cortex but neither were present in the testes. Changes in the ratio of β3 to Δβ3 occurred in some tissues after manipulation of the thyroid status. Both mRNAs were expressed equally in the euthyroid and hypothyroid cerebral cortex, but Δβ3 predominated in the thyrotoxic cerebral cortex. In contrast, both transcripts were expressed equally in the euthyroid and thyrotoxic heart but β3 predominated in the hypothyroid heart. In the lungs, only Δβ3 was detectable irrespective of the thyroid status. The concentrations of β3 and Δβ3 mRNAs in the pituitary were also determined. TRΔβ3 alone was expressed in glands from each group, but the concentration was markedly increased in pituitaries from hypothyroid individuals. Although the assay was designed to determine relative expression within an individual sample and not to quantitate between samples, it is likely that this large difference reflects a true increased Δβ3 expression in the hypothyroid pituitary since the method was optimized to measure linear product accumulation over a range of input RNA concentrations. These findings indicate that alternative splicing of β3 and Δβ3 mRNA is tissue specific and show that it is influenced by thyroid status.

FIG. 10.

Southern blot of β3 and Δβ3 products from rat tissues following manipulation of thyroid status, hybridized to an exon A internal probe. The 767-bp product is β3, and the lower, 452-bp band is Δβ3. Expression in the pituitary is shown in the lower left panel using RNA from three to five glands of euthyroid (Eu), hypothyroid (Hypo), and thyrotoxic (Tox) rats. Lanes containing genomic DNA (Gen), water (H2O), and the absence or inclusion of reverse transcriptase (RT) (−) or (+) are shown. The upper panels show data from a representative experiment, and the graph represents mean values from three animals (with standard error shown). Graphed data are expressed as the relative ratio of β3 to Δβ3; predominant expression of β3 is in the upward direction, and that of Δβ3 is downward.

DISCUSSION

Two novel TR isoforms, TRβ3 and TRΔβ3, have been isolated. Exons encoding unique β1 or β2 N termini are replaced by two new exons in β3 or one in Δβ3. Convergence of the four variants occurs at the common changing-point splice site (65). Thus, the existence of β3 and Δβ3 cannot have been predicted with TRβ null mice, since gene targeting was directed at conserved exons common to all four variants (17, 21). TRβ1 and TRβ2 are transcribed from separate promoters (61), and data presented here suggest that β3 and Δβ3 mRNAs are transcribed from a third promoter and arise by alternative mRNA splicing. TRβ3 mRNA encodes a 390-amino-acid, 44.6-kDa receptor that contains a unique 23-amino-acid N terminus, and TRΔβ3 mRNA encodes a 288-amino-acid, 32.8-kDa protein that lacks the DNA binding domain but retains the nuclear localization signal and ligand binding domain. β3 is a functional receptor, and Δβ3 is a potent antagonist that may also potentiate the action of TRβ3, but not TRβ1, on some response elements under specific circumstances.

The patterns of expression of the β3, Δβ3, β1, β2, α1, and α2 mRNAs differed in individual tissues and were distinct for each isoform, indicating that relative levels of expression of the various TR proteins could potentially differ between tissues. TRβ3 and TRΔβ3 were expressed primarily as 7.0-kb mRNAs, but shorter additional transcripts were seen in some tissues. The 5′-UTR and coding sequence of β3 is 1,445 bp long; in Δβ3 and β1 the region is 1,130 and 1,386 bp, respectively, while the 3′-UTR is longer than 2.9 kb (28). Thus, the smaller β3 mRNA of 4.0 kb and the Δβ3 mRNAs of 3.0 and 1.5 kb could contain the complete 5′-UTR and encode full-length proteins, which is likely since they hybridize to 5′-UTR probes. Such transcripts would include a short 3′-UTR resulting from differential mRNA processing, as described previously in human (48) and chicken (52) TRβ genes. Alternatively, smaller mRNAs could arise from events in which exon A or B skips some or all coding exons and splices to distal sites, resulting in untranslated transcripts that would also include short 3′-UTRs. This is less likely since the changing-point splice site contains a consensus sequence (8) and is used in all species (32). Furthermore, no splicing events that skip the changing point have been documented previously and none were identified in these studies.

In vitro transcription-translation and site-directed mutagenesis confirmed that β3 and Δβ3 cDNAs encode the proteins predicted. These studies showed that TRΔβ3 is translated from β3 mRNA via the internal AUG at position 103, a site retained in TRα and TRβ in all species and conserved in most nuclear receptors (37). Comigration of similar proteins resulting from translation of RXRα, TRα1, and TRβ2 cDNAs in these studies suggests that use of this codon may be a feature in other nuclear receptors. Previous studies have shown that internal AUG codons, including the conserved site used to translate Δβ3 from β3 mRNA, initiate translation from chicken TRα1 mRNA and that the use of these sites is influenced by the 5′-UTR. Thus, chicken TRα1 mRNA encodes four proteins that are expressed in vivo and bind T3 with high affinity (5, 6, 18).

The long 5′-UTRs of β3 and Δβ3 are unusual and of likely functional significance. They contain multiple short ORFs, which occur in only 5 to 10% of eukaryotic mRNAs, particularly those encoding proteins that regulate cell growth and differentiation (29). Similar 5′-UTRs are present in Xenopus TRα and TRβ and are proposed to regulate TR protein synthesis (65) from mRNAs that are temporo-spatially regulated during development (51, 64). 5′-UTR heterogeneity has been reported in mouse retinoic acid receptor (RARγ) (27) and RARβ2 (68) mRNAs. The RARβ2 5′-UTR contains five overlapping ORFs that alter protein expression in a tissue-specific and developmentally regulated manner in transgenic mice (68). The human androgen receptor also contains a 577-bp 5′-UTR, which is necessary for induction of translation (41). These considerations suggest that translation of β3 and Δβ3 proteins is likely to be tightly regulated. Expression of their mRNAs was also regulated (Fig. 4 and 10) and varied in relation to the levels of expression of β1, β2, α1, and α2 mRNAs in different tissues (Fig. 4). β3 and Δβ3 mRNAs were expressed in all tissues studied except the testes, indicating that the proposed third promoter is transcribed widely. Additional, shorter transcripts were expressed in some tissues, and differing ratios of β3 and Δβ3 mRNAs suggested that mRNA splicing is tissue specific. Alteration of β3 and Δβ3 mRNA ratios following changes in thyroid status further suggests that splicing may be regulated by thyroid hormones.

DNA binding studies support the likelihood that regulated tissue-specific expression of β3 and Δβ3 is functionally important. TRβ3, like TRβ1, bound specifically to DNA as a heterodimer with RXR, but Δβ3-RXR heterodimers interacted poorly, presumably because these complexes contain a single DNA binding domain. RXR binds as a homodimer to elements organized as a DR+1 but does not bind DR+4 elements (22), as seen in Fig. 7A. It appears surprising, therefore, that Δβ3-RXR complexes interact with the DR+4 element, albeit poorly, since TRΔβ3 lacks a DNA binding domain. Presumably, the formation of putative Δβ3-RXR heterodimers results in a conformational change in RXR that enables a stable complex to bind weakly to the DR+4 element. This seems a likely probability since heterodimerization of RXR with other TR isoforms, which contain identical ligand binding and dimerization domains to Δβ3, results in the formation of complexes that possess two DNA binding domains and bind to DR+4 elements with high affinity (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, preformed β1- or β3-RXR heterodimers were disrupted efficiently by lower concentrations of Δβ3 than those required for DNA binding, suggesting that Δβ3 competes for RXR in solution to limit its availability for heterodimerization with β1 or β3. Alternatively, Δβ3 could interact with β1 or β3 to limit their access to RXR. This seems less likely since studies with chicken TRα failed to identify interactions between truncated and full-length TRs (6). Thus, an equilibrium can be proposed in which the ratio of β3 to Δβ3, relative to concentrations of other TR isoforms and RXR, influences which functional heterodimers coexist within T3 target cells. Varying ratios of β3 to Δβ3 mRNAs in different tissues indicate that these equilibria are tissue specific. In this model, small increases in the concentration of Δβ3 are predicted to disrupt DNA binding of TR-RXR heterodimers and alter the balance of such equilibria, in keeping with its potent dominant negative activity. This model is likely to be applicable to signaling via other nuclear receptors that heterodimerize with and compete for RXR (11, 20, 34).

The mechanism of transcriptional activation by TRs and other nuclear receptors includes repression of basal gene expression by unliganded receptor, involving interaction with a corepressor complex containing histone deacetylase activity, followed by T3 induction, involving displacement of the corepressor by the ligand and recruitment of coactivator proteins with intrinsic histone acetylase activity (39, 62). Similarly, TRβ3 induces reporter gene expression in two stages, involving repression by unliganded receptor followed by hormone activation, as described previously for TRs (7, 13). However, transactivation mediated by TRβ3 was TRE specific. T3 activation of each of the three elements was more potently induced by β3 than by β1, but the magnitude of activation differed between elements and the differential potencies of β3 and β1 varied between elements (Fig. 8B and C). Repression of gene expression by unliganded receptor was greater with TRβ3 than with TRβ1 on the ME TRE but was similar for both receptors on the MHC and PAL elements. In contrast, Δβ3 failed to activate transcription, although its actions were also TRE specific. Δβ3 was a potent inhibitor of ME TRE gene expression in the absence and presence of T3 (Fig. 8B and C), but expression of MHC and PAL was unaffected under either condition. The mechanisms responsible for these differences are unknown at this stage. The data, however, suggest the possibility that a specific factor whose activity is inhibited by both unliganded and liganded Δβ3 is required for basal expression of the ME TRE in COS-7 cells but not for basal expression of the MHC and PAL TREs.

In cotransfections, Δβ3 was a potent antagonist of both β1 and β3 at equimolar concentrations but α2 was inactive, in agreement with published data (47) and indicating that Δβ3 is at least 10-fold more potent. Thus, Δβ3 differs from α2 since it is a potent repressor and retains ligand binding activity whereas α2 displays weak activity, cannot bind T3, and does not interact with corepressor proteins (54). Repression of β1-mediated induction of each TRE by Δβ3 was proportional to the concentration of cotransfected Δβ3 (Fig. 9B) and correlated with the degree to which the three elements were activated by T3. Antagonism of β3 actions by Δβ3 differed between the TREs and, in contrast, involved an initial potentiation of TRβ3 action on the MHC and PAL elements (Fig. 9A). On the MHC element, low concentrations of Δβ3 increased β3-mediated induction of the element whereas addition of higher concentrations resulted in repression. A similar observation was seen for the PAL element but not for the ME TRE, on which β3-mediated activation was inhibited in a concentration-dependent fashion by Δβ3. These data, together with the findings that Δβ3 potently inhibits ME TRE gene expression but not MHC or PAL TRE gene expression, in the absence and presence of T3 (Fig. 8B and C), indicate that additional unknown factors are likely to influence the actions of, and interactions between, TRΔβ3 and TRβ3. Thus, induction of MHC and PAL by β3, but not β1, is proposed to involve a cofactor that moderates its transactivation potency. In accordance with this model, low concentrations of cotransfected Δβ3 are predicted to inhibit the activity of this moderating cofactor and result in the net potentiation of β3-mediated transactivation. At higher concentrations, Δβ3 would inhibit the expression of MHC and PAL by acting as a dominant negative antagonist of β3. This hypothesis emphasizes the primarily inhibitory action of Δβ3. The specificity of the model to TRβ3-induced activation of certain TREs may result from the unique β3 N-terminal domain. Thus, the β3 N terminus is predicted to interact specifically with the proposed moderating cofactor, which would therefore not interact with TRβ1. Interestingly the N terminus of β2, but not of β1, interacts with a subset of coactivators (44) and the SMRT corepressor (63) in the absence of T3, supporting the view that the region confers specificity to TRβ isoforms (31).

These studies characterize two novel, alternatively spliced TRβ isoforms which are expressed widely. TRβ3 is a functional receptor, and TRΔβ3 is a potent dominant negative antagonist that binds hormone. Similar examples of truncated nuclear receptors that act as antagonists have been identified (15, 38), in addition to those described for chicken TRα1 (6). Thus, a hypothesis can be proposed in which tissue-specific and hormone-regulated variation in the relative concentrations of TRβ3 and TRΔβ3 modulates target organ responsiveness to T3. Such a mechanism defines a new level of specificity in the control of tissue thyroid status, which may be applicable to the actions of other nuclear receptors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by an MRC Career Establishment Grant (G9803002) and a Wellcome Trust Project Grant (050570).

I am indebted to Clare Harvey for help with transfections and experimental advice and am most grateful to the following investigators for essential materials: Reed Larsen (Boston, Mass.) for rTRβ1 (erb62) and mTRα1 (erb13); Greg Brent (Los Angeles, Calif.) for pQE8hRXRα; Ron Evans (San Diego, Calif.) for hRXRα; Fred Wondisford (Boston, Mass.) for pSG5hTRβ2; Larry Jameson (Chicago, Ill.) for MEpA3LUC, MHCpA3LUC, and PALpA3LUC reporters and pRSVhTRα2; Dave Carling (London, United Kingdom) for the λDASH genomic library.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abel E D, Boers M E, Pazos-Moura C, Moura E, Kaulbach H, Zakaria M, Lowell B, Radovick S, Liberman M C, Wondisford F. Divergent roles for thyroid hormone receptor beta isoforms in the endocrine axis and auditory system. J Clin Investig. 1999;104:291–300. doi: 10.1172/JCI6397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arpin C, Pihlgren M, Fraichard A, Aubert D, Samarut J, Chassande O, Marvel J. Effects of T3R alpha 1 and T3R alpha 2 gene deletion on T and B lymphocyte development. J Immunol. 2000;164:152–160. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck-Peccoz P, Chatterjee V K K, Chin W W, DeGroot L J, Jameson J L, Nakamura H, Refetoff S, Usala S J, Weintraub B D. Nomenclature of thyroid hormone receptor beta-gene mutations in resistance to thyroid hormone: consensus statement from the first workshop on thyroid hormone resistance, July 10–11, 1993, Cambridge, United Kingdom. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78:990–993. doi: 10.1210/jcem.78.4.8157732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat M K, Parkison C, McPhie P, Liang C M, Cheng S Y. Conformational changes of human beta 1 thyroid hormone receptor induced by binding of 3,3′,5-triiodo-l-thyronine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;195:385–392. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bigler J, Eisenman R N. c-erbA encodes multiple proteins in chicken erythroid cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4155–4161. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.10.4155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bigler J, Hokanson W, Eisenman R N. Thyroid hormone receptor transcriptional activity is potentially autoregulated by truncated forms of the receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2406–2417. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brent G A, Dunn M K, Harney J W, Gulick T, Larsen P R, Moore D D. Thyroid hormone aporeceptor represses T3-inducible promoters and blocks activity of the retinoic acid receptor. New Biol. 1989;1:329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burge C B, Tuschl T, Sharp P A. The RNA world: the nature of modern RNA suggests a prebiotic RNA. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chassande O, Fraichard A, Gauthier K, Flamant F, Legrand C, Savatier P, Laudet V, Samarut J. Identification of transcripts initiated from an internal promoter in the c-erbA alpha locus that encode inhibitors of retinoic acid receptor-alpha and triiodothyronine receptor activities. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1278–290. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.9.9972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiellini G, Apriletti J W, al Yoshihara H, Baxter J D, Ribeiro R C, Scanlan T S. A high-affinity subtype-selective agonist ligand for the thyroid hormone receptor. Chem Biol. 1998;5:299–306. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu R, Madison L D, Lin Y, Kopp P, Rao M S, Jameson J L, Reddy J K. Thyroid hormone (T3) inhibits ciprofibrate-induced transcription of genes encoding beta-oxidation enzymes: cross talk between peroxisome proliferator and T3 signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11593–11597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham J M, Purucker M E, Jane S M, Safer B, Vanin E F, Ney P A, Lowrey C H, Nienhuis A W. The regulatory element 3′ to the A gamma-globin gene binds to the nuclear matrix and interacts with special A-T-rich binding protein 1 (SATB1), and SAR/MAR-associating region DNA binding protein. Blood. 1994;84:1298–1308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damm K, Thompson C C, Evans R M. Protein encoded by v-erbA functions as a thyroid-hormone receptor antagonist. Nature. 1989;339:593–597. doi: 10.1038/339593a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denver R J, Ouellet L, Furling D, Kobayashi A, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Puymirat J. Basic transcription element-binding protein (BTEB) is a thyroid hormone-regulated gene in the developing central nervous system. Evidence for a role in neurite outgrowth. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23128–23134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebihara K, Masuhiro Y, Kitamoto T, Suzawa M, Uematsu Y, Yoshizawa T, Ono T, Harada H, Matsuda K, Hasegawa T, Masushige S, Kato S. Intron retention generates a novel isoform of the murine vitamin D receptor that acts in a dominant negative way on the vitamin D signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3393–3400. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forrest D, Erway L C, Ng L, Altschuler R, Curran T. Thyroid hormone receptor beta is essential for development of auditory function. Nat Genet. 1996;13:354–357. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forrest D, Hanebuth E, Smeyne R J, Everds N, Stewart C L, Wehner J M, Curran T. Recessive resistance to thyroid hormone in mice lacking thyroid hormone receptor beta: evidence for tissue-specific modulation of receptor function. EMBO J. 1996;15:3006–3015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forrest D, Sjoberg M, Vennstrom B. Contrasting developmental and tissue-specific expression of alpha and beta thyroid hormone receptor genes. EMBO J. 1990;9:1519–1528. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraichard A, Chassande O, Plateroti M, Roux J P, Trouillas J, Dehay C, Legrand C, Gauthier K, Kedinger M, Malaval L, Rousset B, Samarut J. The T3R alpha gene encoding a thyroid hormone receptor is essential for post-natal development and thyroid hormone production. EMBO J. 1997;16:4412–4420. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Villalba P, Jimenez-Lara A M, Aranda A. Vitamin D interferes with transactivation of the growth hormone gene by thyroid hormone and retinoic acid. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:318–327. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gauthier K, Chassande O, Plateroti M, Roux J P, Legrand C, Pain B, Rousset B, Weiss R, Trouillas J, Samarut J. Different functions for the thyroid hormone receptors TRalpha and TRbeta in the control of thyroid hormone production and post-natal development. EMBO J. 1999;18:623–631. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glass C K. Differential recognition of target genes by nuclear receptor monomers, dimers, and heterodimers. Endocr Rev. 1994;15:391–407. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-3-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gothe S, Wang Z, Ng L, Kindblom J M, Barros A C, Ohlsson C, Vennstrom B, Forrest D. Mice devoid of all known thyroid hormone receptors are viable but exhibit disorders of the pituitary-thyroid axis, growth, and bone maturation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1329–1341. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodin R A, Lazar M A, Wintman B I, Darling D S, Koenig R J, Larsen P R, Moore D D, Chin W W. Identification of a thyroid hormone receptor that is pituitary-specific. Science. 1989;244:76–79. doi: 10.1126/science.2539642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johansson C, Gothe S, Forrest D, Vennstrom B, Thoren P. Cardiovascular phenotype and temperature control in mice lacking thyroid hormone receptor-beta or both alpha1 and beta. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H2006–H2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.6.H2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansson C, Vennstrom B, Thoren P. Evidence that decreased heart rate in thyroid hormone receptor-alpha1-deficient mice is an intrinsic defect. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R640–R646. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.2.R640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kastner P, Krust A, Mendelsohn C, Garnier J M, Zelent A, Leroy P, Staub A, Chambon P. Murine isoforms of retinoic acid receptor gamma with specific patterns of expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2700–2704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koenig R J, Warne R L, Brent G A, Harney J W, Larsen P R, Moore D D. Isolation of a cDNA clone encoding a biologically active thyroid hormone receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5031–5035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozak M. An analysis of vertebrate mRNA sequences: intimations of translational control. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:887–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.4.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozak M. The scanning model for translation: an update. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:229–241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langlois M F, Zanger K, Monden T, Safer J D, Hollenberg A N, Wondisford F E. A unique role of the beta-2 thyroid hormone receptor isoform in negative regulation by thyroid hormone. Mapping of a novel amino-terminal domain important for ligand-independent activation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24927–24933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lazar M A. Thyroid hormone receptors: multiple forms, multiple possibilities. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:184–193. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-2-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lazar M A, Hodin R A, Darling D S, Chin W W. Identification of a rat c-erbA alpha-related protein which binds deoxyribonucleic acid but does not bind thyroid hormone. Mol Endocrinol. 1988;2:893–901. doi: 10.1210/mend-2-10-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehmann J M, Zhang X K, Graupner G, Lee M O, Hermann T, Hoffmann B, Pfahl M. Formation of retinoid X receptor homodimers leads to repression of T3 response: hormonal cross talk by ligand-induced squelching. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7698–7707. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lezoualc'h F, Hassan A H, Giraud P, Loeffler J P, Lee S L, Demeneix B A. Assignment of the beta-thyroid hormone receptor to 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine-dependent inhibition of transcription from the thyrotropin-releasing hormone promoter in chick hypothalmic neurons. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6:1797–1804. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.11.1480171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mangelsdorf D J, Ong E S, Dyck J A, Evans R M. Nuclear receptor that identifies a novel retinoic acid response pathway. Nature. 1990;345:224–229. doi: 10.1038/345224a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez E, Moore D D, Keller E, Pearce D, Robinson V, MacDonald P N, Simons S S, Jr, Sanchez E, Danielsen M. The Nuclear Receptor Resource Project. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:163–165. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsui T, Sashihara S. Tissue-specific distribution of a novel C-terminal truncation retinoic acid receptor mutant which acts as a negative repressor in a promoter- and cell-type-specific manner. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1961–1967. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKenna N J, Lanz R B, O'Malley B W. Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:321–344. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitsuhashi T, Tennyson G E, Nikodem V M. Alternative splicing generates messages encoding rat c-erbA proteins that do not bind thyroid hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5804–5808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizokami A, Chang C. Induction of translation by the 5′-untranslated region of human androgen receptor mRNA. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25655–25659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murray M B, Zilz N D, McCreary N L, MacDonald M J, Towle H C. Isolation and characterization of rat cDNA clones for two distinct thyroid hormone receptors. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:12770–12777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nuclear Receptors Committee. A unified nomenclature system for the nuclear receptor superfamily. Cell. 1999;97:161–163. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80726-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oberste-Berghaus C, Zanger K, Hashimoto K, Cohen R N, Hollenberg A N, Wondisford F E. Thyroid hormone-independent interaction between the thyroid hormone receptor beta2 amino terminus and coactivators. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1787–792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plateroti M, Chassande O, Fraichard A, Gauthier K, Freund J N, Samarut J, Kedinger M. Involvement of T3Ralpha- and beta-receptor subtypes in mediation of T3 functions during postnatal murine intestinal development. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1367–1378. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prost E, Koenig R J, Moore D D, Larsen P R, Whalen R G. Multiple sequences encoding potential thyroid hormone receptors isolated from mouse skeletal muscle cDNA libraries. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6248. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.6248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rentoumis A, Chatterjee V K, Madison L D, Datta S, Gallagher G D, Degroot L J, Jameson J L. Negative and positive transcriptional regulation by thyroid hormone receptor isoforms. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:1522–1531. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-10-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakurai A, Nakai A, DeGroot L J. Structural analysis of human thyroid hormone receptor beta gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1990;71:83–91. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(90)90245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samuels H H, Stanley F, Casanova J. Depletion of l-3,5,3′-triiodothyronine and l-thyroxine in euthyroid calf serum for use in cell culture studies of the action of thyroid hormone. Endocrinology. 1979;105:80–85. doi: 10.1210/endo-105-1-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sap J, Munoz A, Damm K, Goldberg Y, Ghysdael J, Leutz A, Beug H, Vennstrom B. The c-erb-A protein is a high-affinity receptor for thyroid hormone. Nature. 1986;324:635–640. doi: 10.1038/324635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shi Y B, Yaoita Y, Brown D D. Genomic organization and alternative promoter usage of the two thyroid hormone receptor beta genes in Xenopus laevis. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:733–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Showers M O, Darling D S, Kieffer G D, Chin W W. Isolation and characterization of a cDNA encoding a chicken beta thyroid hormone receptor. DNA Cell Biol. 1991;10:211–221. doi: 10.1089/dna.1991.10.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strait K A, Zou L, Oppenheimer J H. Beta 1 isoform-specific regulation of a triiodothyronine-induced gene during cerebellar development. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6:1874–1880. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.11.1282672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tagami T, Kopp P, Johnson W, Arseven O K, Jameson J L. The thyroid hormone receptor variant alpha2 is a weak antagonist because it is deficient in interactions with nuclear receptor corepressors. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2535–2544. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.5.6011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Todd J F, Small C J, Akinsanya K O, Stanley S A, Smith D M, Bloom S R. Galanin is a paracrine inhibitor of gonadotroph function in the female rat. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4222–4229. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Umesono K, Murakami K K, Thompson C C, Evans R M. Direct repeats as selective response elements for the thyroid hormone, retinoic acid, and vitamin D3 receptors. Cell. 1991;65:1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90020-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weinberger C, Thompson C C, Ong E S, Lebo R, Gruol D J, Evans R M. The c-erb-A gene encodes a thyroid hormone receptor. Nature. 1986;324:641–646. doi: 10.1038/324641a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wikstrom L, Johansson C, Salto C, Barlow C, Campos Barros A, Baas F, Forrest D, Thoren P, Vennstrom B. Abnormal heart rate and body temperature in mice lacking thyroid hormone receptor alpha 1. EMBO J. 1998;17:455–461. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams G R, Bland R, Sheppard M C. Characterization of thyroid hormone (T3) receptors in three osteosarcoma cell lines of distinct osteoblast phenotype: interactions among T3, vitamin D3, and retinoid signaling. Endocrinology. 1994;135:2375–2385. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.6.7988420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams G R, Harney J W, Forman B M, Samuels H H, Brent G A. Oligomeric binding of T3 receptor is required for maximal T3 response. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19636–19644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wood W M, Dowding J M, Haugen B R, Bright T M, Gordon D F, Ridgway E C. Structural and functional characterization of the genomic locus encoding the murine beta 2 thyroid hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:1605–1617. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.12.7708051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu L, Glass C K, Rosenfeld M G. Coactivator and corepressor complexes in nuclear receptor function. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:140–147. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang Z, Hong S H, Privalsky M L. Transcriptional anti-repression. Thyroid hormone receptor beta-2 recruits SMRT corepressor but interferes with subsequent assembly of a functional corepressor complex. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37131–37138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yaoita Y, Brown D D. A correlation of thyroid hormone receptor gene expression with amphibian metamorphosis. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1917–1924. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.11.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yaoita Y, Shi Y, Brown D. Xenopus laevis alpha and beta thyroid hormone receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7090–7094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zavacki A M, Harney J W, Brent G A, Larsen P R. Dominant negative inhibition by mutant thyroid hormone receptors is thyroid hormone response element and receptor isoform specific. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:1319–1330. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.10.8264663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zavacki A M, Harney J W, Brent G A, Larsen P R. Structural features of thyroid hormone response elements that increase susceptibility to inhibition by an RTH mutant thyroid hormone receptor. Endocrinology. 1996;137:2833–2841. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.7.8770904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zimmer A, Zimmer A M, Reynolds K. Tissue specific expression of the retinoic acid receptor-beta 2: regulation by short open reading frames in the 5′-noncoding region. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1111–1119. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.4.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]