Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic generated economic contraction across the world. In India, the stringent lockdown led to extreme distress. The unprecedented situation adversely affected the women’s efforts to balance professional life with family life because of a disproportionate increase in their domestic work burden and a shift in their workstation to home. Since every job cannot be performed remotely, women employed in healthcare services, banks and media witnessed additional risks of commuting and physical interaction at the workplace. Based on personal interviews of women in the Delhi-NCR region, the study aims to explore the commonalities and variances in the challenges experienced by the women engaged in diverse occupations. Using the qualitative methodology of flexible coding, the study finds that a relatively larger section of women travelling to their office during the pandemic, rather than those working from home, had an effective familial support system that helped them navigate this tough time.

Keywords: COVID-19, work–family balance, flexible coding, Delhi metro, work from home

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and the economic contraction that followed it have had a massive effect on everyone across the globe. The adverse impact of this shock has been exceptionally high for working women as it has led to a disproportionate increase in their already unequally distributed domestic work burden, making them more vulnerable to ‘cuts and lay-offs’ (Collins, Landivar, Ruppanner, & Scarborough, 2020). The global scenario was also mirrored in India, where the pandemic led to a lockdown that was among the longest and most stringent in the world. Findings indicate a gender gap in economic outcomes, with women facing a higher risk of losing livelihoods (Abraham, Basole, & Kesar, 2021; Dang and Nguyen, 2021). Those who were able to retain their jobs faced severe challenges due to closure of schools, stoppage of hired domestic help, recurrent kitchen time, limited social interaction, irregular office hours, the pressure of job insecurity and simultaneous demands of all family members present in the home, etc. (Adisa, Aiyenitaju, & Adekoya, 2021; Boncori, 2020; United Nations, 2020). All this, together with the constant fear of contagion in the workplace and during commuting, increased the mental pressure on working women. Commuting to the office in a public or shared vehicle increased the risk of getting infected by the virus on the way to and from work. Working at the office made it difficult to avoid direct or indirect contact with colleagues, visitors and objects at the workplace (Uehara et al., 2021). Thus, the spill-over effects of tension and fatigue from the professional life to the family life and vice-versa may be of a much higher magnitude during the current pandemic and lockdown, making it difficult for women to strike a balance between the two (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985; Grzywacz & Marks, 2000; Leiter & Durup, 1996).

Studies indicate that despite the common work–family balancing issues, every section of working women faced additional problems that were linked to their specific professional requirements. In the case of healthcare workers, the uncertainty imposed by the heightened risk of COVID-19 infection due to the nature of their job, added another dimension of self-isolation to their balancing efforts. They felt abandoned due to the stigma of transmitting infection back home (Aughterson, McKinlay, Fancourt, & Burton, 2021; Dagyaran et al., 2021). On the other hand, the sudden shift from face-to-face to online teaching mode increased the workloads of women in academics. They experienced a loss of creativity due to the varied problems like learning how to use a digital platform for preparing illustrative presentations for the students, addressing the specific needs of children as per their competencies and interacting with them effectively, etc. (Aperribai, Cortabarria, Aguirre, Verche & Borges, 2020; Dogra & Kaushal, 2021). Similarly, women in the information technology (IT) industry suffered from low productivity due to repeatedly moving between family needs and work, with no clocks setting the limits (Roy, 2021; Russo, Hanel, Altnickel, & van Berkel, 2021).

Given this background, the study uses a qualitative approach to explore the many challenges experienced by working women in balancing work and family needs and the factors that helped them navigate through this tough time. It also tries to understand the differences in the way in which the pandemic affected women who were employed in diverse occupations.

Our paper contributes to the existing understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on working women in several ways. First, it distinguishes between the situations of women working in occupations that could be performed remotely (i.e. from home) and those that required travel to the workplace. This approach helps the paper bring forth the differences and commonality in the balancing issues pertaining to both the categories of working women, that is, those for whom the workstation shifted to the home and those exposed to the risks of commuting to and from the workplace and being in that enclosed space with co-workers for 8 hours or more. Second, given the hazard of catching an infection while commuting, the study examines the risks faced by women utilizing the Delhi metro for travelling to work and those who changed their preferred means of travel away from the metro. The importance of this dimension arises from the fact that over the years, the availability of the Delhi metro has served as a milestone in facilitating women of Delhi-NCR to gain access to the labour market. Third, the paper captures the relative differences in the situations of the two sets of working women based on the extent to which they received support and cooperation from their spouse, in-laws and other family members and whether this helped them in steering through this extreme situation while continuing to work. It also explores the reasons for differences in the way that women coped in order to overcome the stress of balancing the dual fronts. Fourth, the strength of this work lies in its mixed-method approach whereby the qualitative methodology of flexible coding used for interpreting the open-ended, in-depth interviews of working women is supported by the quantitative survey that enabled an understanding of the background characteristics of the respondents in our sample.

The findings from the study indicate that women in professions such as teaching, research, information technology, marketing and event management could perform their work remotely, thus reducing their workplace-related risks. However, their official burden blurred the time and space boundaries between work and family life. Simultaneous functioning of office and school within the living area and physical disconnect from the colleagues and seniors generated job dissatisfaction among them. On the other hand, women engaged as doctors, nurses, pharmacists, bankers, communication managers, daily wage workers, etc., had to visit their workplace. They performed their official duties with the additional stress of catching and transmitting infection. A few women quarantined themselves to protect their family members, while others found it infeasible to do so. The fear also prevented them from utilizing the services of the Delhi metro for commuting to their workplace. But non-metro using women too expressed their anxiety of travelling alone on deserted roads. Moreover, irrespective of the work arrangement, all the women who were interviewed expressed concerns about the health of their elderly family members and children. In terms of the facilitating factors, a relatively larger section of women travelling to their workplace, rather than those working from home, had an adequate support system in the form of sharing domestic responsibilities and emotional baggage by the spouse, in-laws and other co-residing family members.

The outline of the paper is as follows. The second and third sections explain the study setting, sample design, methodology and sample description. The fourth section presents the challenges experienced by women working from home and travelling to the workplace. The fifth section explores the relative differences in the factors facilitating both sets of working women in tiding over the difficult situation created by the pandemic. The sixth section discusses and summarizes the findings and the last section concludes the paper.

Study Setting and Design

The paper is based on a larger study for which we conducted a primary survey in the Delhi-NCR region, comprising a sample of 462 women. 1 Its objective was to explore the labour supply dynamics and changes in the commuting patterns and preferences of educated middle-class urban women in the context of improved urban connectivity due to the growth of the Delhi Metro Rail Network. The women in the sample were in the age group of 20 years to 65 years, and the majority of them were educated up to at least the secondary level.

A mixed-methods approach was used, in which a household questionnaire was prepared to gather quantitative data, followed by personal interviews to capture detailed qualitative information. A combination of purposive sampling and snowball sampling techniques was used for undertaking the survey during the extreme circumstances created by the pandemic and lockdown. The entire survey was completed in two phases. The first phase was conducted between April and May 2020, 2 in which we collected detailed information on the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

The second phase of the survey was undertaken in October and November 2020, when the Indian economy started finding ways of resuming normalcy. We selected a set of 40 women from our existing sample of 145 working respondents based on their diverse occupational status. All of them were contacted again and requested for additional time. 30 of them agreed to give us more time for detailed personal interviews. An open-ended semi-structured questionnaire was used for collecting information on the impact of COVID-19 on their professional and personal life, the challenges of balancing the two domains and factors that helped them tide over the difficult situation. This paper is based on the analysis of qualitative findings from these interviews.

Methodology and Sample Description

Given the study’s objective and availability of primary findings from quantitative analysis of our dataset, we utilized a mix of deductive and inductive coding strategies for analysing information collected through our in-depth interviews. This iterative coding procedure of moving between literature and data is consistent with the flexible coding approach of Deterding and Waters (2021). A deductive method was used to develop the initial coding framework based on our understanding of the existing literature. It was followed by an inductive strategy, whereby new codes were generated and added from the data. After that, all codes were grouped into themes, each representing a meaningful pattern in the data. The complete analysis of qualitative data was performed by using the NVivo12 software.

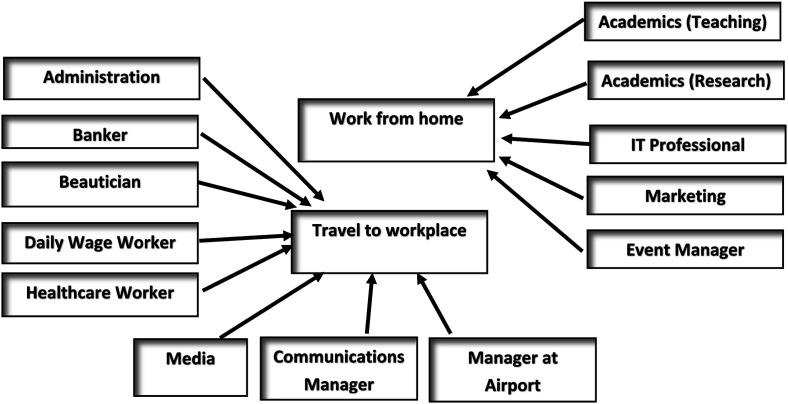

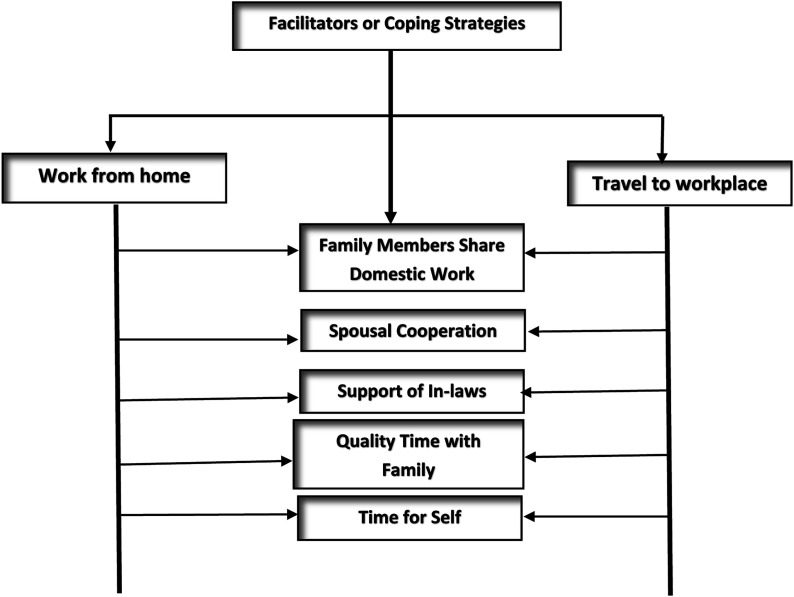

We first divided the women employed in diverse occupations into two sections based on their work arrangements during the pandemic. Figure 1 shows that women in academics (college professor, school teacher and researcher), IT companies, marketing and event management worked remotely. On the other hand, women engaged as healthcare workers (doctor, nurse, pharmacist and dietician), daily wage workers, beauticians, communications managers, managers at the airport and those in banks, media and administration had to travel to their workplace.

Figure 1.

Work Arrangement Wise Distribution of Working Women in Diverse Occupations. Source: Authors’ creation from qualitative survey.

Details regarding the occupations and personal attributes of the 30 women who gave us time for the in-depth interviews are in Appendix Table A1. Briefly, while 17 women had to travel to their place of work during the pandemic, 13 were able to work from home. All the women are educated. While four women working as daily wage earners have completed their secondary or higher secondary level of education, all the others are graduates or postgraduates. The three women in the IT industry and media house are engineers. 12 women live in small families with four or fewer members, while 18 reside in a large joint family set up with 5–10 members.

Regarding their marital status, 22 women are married, six unmarried and two divorced or separated from their spouse. Among the married women, all except 3, have one or more school-going children, and 17 are co-residing with their in-laws. Also, the two unmarried women have school-going siblings in their families. Spouses of 13 out of 21 women who are married are well-qualified or have professional training. Spouses of nine are relatively less educated and employed in insecure jobs. Care was taken to inform each respondent about the purpose of the study and get their permission before proceeding with the survey. In order to protect the identity of the respondents, their names have been changed and their place of work is not mentioned.

The qualitative analysis helped us to identify four themes (Appendix Table A2): (i) work–family balance–related challenges faced by women in occupations that can be undertaken remotely; (ii) work–family balance–related challenges experienced by women in occupations that require commuting to the workplace; (iii) challenges faced by all working women, irrespective of the workstation; and (iv) coping strategies or factors which facilitate working women in navigating through the hardships due to the pandemic. In the following paragraphs, we explain the findings based on each of these themes.

Challenges of Work–Family Balance

Globally, women and girls shoulder the bulk of the burden of domestic responsibilities that include time and resources spent on domestic chores, childcare and elderly care. This requires that they ‘combine the roles of mother, domestic manager and wage earner within a finite time’ (Pickup, 1984). Moreover, they are expected to perform equally well by simultaneously fulfilling the mutually incompatible demands from work and family. The physical and mental limitations of handling the multiple fronts, together with time constraints lead to inter-role conflicts (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985).

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic was marked by a disproportionate increase in women’s burden of unpaid household work (Craig & Churchill, 2020; Chauhan, 2020). The findings from our quantitative sample of 145 working women showed that during the pandemic, 89% of them experienced an increase in the amount of time devoted to domestic responsibilities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Increase in Average Time Spent (Per Day) on Domestic Chores During Pandemic (%).

| No. of Hours | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 0 hours | 16 | 11.0 |

| 1–2 hours | 90 | 62.1 |

| 3–4 hours | 26 | 17.9 |

| 5 hours or more | 13 | 9.0 |

| Total | 145 | 100.0 |

Source: Primary survey.

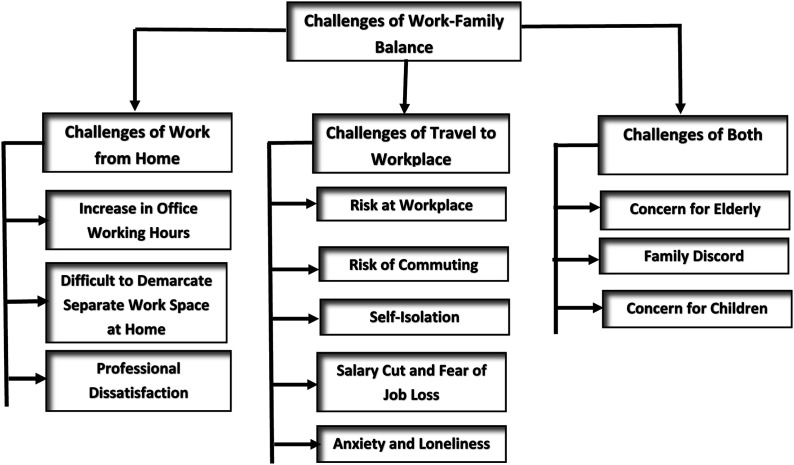

Home schooling, intensified care needs of the elderly, completion of household chores like sweeping, cleaning utensils, washing clothes, etc. due to absence of hired help, together with psychological stress of salary cut, job insecurity, official deadlines, masking, social distancing and sanitization, exacerbated the work–life balancing problems of working women (Seck, Encarnacion, Tinonin, & Duerto-Valero, 2021). However, several of these challenges are linked specifically with the type of work arrangement of women during COVID-19. In order to capture such commonalities and variations, we explore the impact of pandemic on women employed in diverse occupations, some of which could be performed remotely while others required travel to the workplace. Thematic map 1 in Figure 2 provides an overview of our segmented approach to enable a better understanding of the issue.

Figure 2.

Thematic Map 1 for Challenges of Working Women in Diverse Work Arrangements. Source: Authors’ creation from qualitative survey.

Challenges of Work from Home

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed the world of work. The risk of getting the infection while travelling or meeting colleagues at the workplace has forced companies to allow their employees to work from home. Physical distancing through teleworking or remote working was adopted globally as a necessary measure for reducing the spread of coronavirus infection. Agba et al., (2020) define work from home as ‘a flexible work arrangement in which staff of an organization performs their assigned tasks at home while communicating and maintaining contact(s) with their office via emails, chats, phone or through the deployment of internet facilities’. Though work from home enabled women to work safely and save commuting time, it posed several challenges to their efforts at striking a work–family balance.

Increase in office working hours

The use of digital technology has blurred the time interface between work and family. The flexibility provided by remote working is accompanied by increased inter-role interruptions (Allen, Golden, & Shockley, 2015). The individual remains connected to the official position, resulting in work intensification (Kelliher & Anderson, 2010). There is an erosion of the concept of nine to five work or regular working hours. Thus, there is a constant mental pressure of responding to the office demands. This new form of work arrangement does not seem to facilitate working women in striking a balance between their work life and family life (Noonan & Glass, 2012). In this regard, we cite the experiences of women academicians and information technology (IT) professionals in our survey sample.

Meenu is a 53-year-old assistant professor. On a usual basis, she spent 5 hours a day in her college and an additional 4 hours at home for completing her office work. Through judicious time management and the support of family members, she can strike a balance between her professional and personal life.

‘During the pandemic, my entire routine is in a state of utter chaos. The official work pressure has increased because the work from the home system requires preparation of presentations for online teaching, organizing digitally managed workshops, attending untimely meetings, conducting exams, attending calls of parents’, solving the queries of students, etc. Now, my working hours are scattered throughout the day. Often, I have to work late into the night to meet the deadlines and commitments’ (College Professor 1).

Shivani is a 26-year-old automation engineer working with an IT company. At the beginning of the COVID-19 scare, her company started functioning in the work from home mode. She said, ‘my office timings have stretched from 8 hours a day (before Covid-19) to 12 hours a day (during Covid-19). My work starts at 11 am and the office continues to function till 11 pm. There is no specific lunch time or tea time, and meetings can be scheduled at any time during the day. There is no personal space left. Also, I am under a persistent pressure of attaining the performance targets’. It is hard for her to find time for online education of her younger siblings and help her mother in domestic duties. She fears that this change in work pattern might continue even after COVID-19. We quoted her statement as ‘the IT industry is moving away from the Brick-and-Mortar offices, and seems to be permanently switching towards work from home culture’ (IT Professional 2).

Difficult to demarcate separate work space at home

Work from home is linked with the problem of spatially demarcating and assuring smooth simultaneous functioning of the school, office, kitchen and living space within a restricted closed-door home. It is challenging for working mothers to draw clear boundaries between the several mutually exclusive domains, often forcing them to schedule new routines (Lau & Lee, 2020; Uddin, 2021). Two academics Brittany and Sheva very aptly explained this dimension of work–family balancing in their autoethnographic study (Guy & Arthur, 2020). Brittany shared her experience, ‘My seven months old son regularly makes an appearance on conference calls and meetings. I hold him as he screams, smacks me, and pulls my hair during a tantrum. Today that means my child is also my most important colleague’.

In our qualitative survey, 54% of the women working from home, particularly with small children or joint families, experienced such problems. Some of our respondents said the noise of children playing around generates distractions, making it impossible to complete the assigned tasks on time. One of them stated, ‘often, I have to postpone my official meetings and shift my prime office hours to dawn and night when my children are sleeping’.

Komal is 29-year-old woman working in the social media department of a consulting company. Her family includes her 3-year-old daughter and her mother-in-law. Her usual office hours are from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Her husband does not contribute to the domestic responsibilities. Work from home during COVID-19 enhanced the pressure of multiple obligations.

She said, ‘there is no domestic help in the house. I try to complete the cleaning and washing by waking up early in the morning. While attending my meetings and making important official calls, I have to keep my daughter by my side. I simultaneously try to fulfill her pre-school education requirements from home, play with her, and engage her in creative activities’ (Marketing Executive).

Sheena is a 35-year-old lady living in a big joint family of eight members. In their house, she has to share a small space of one room with her husband and two small daughters aged 12 years and two and a half years. She narrates her problems as follows.

‘My work involves lots of social interaction and networking, all of which I have to manage from home. I have no separate space to conduct my zoom meetings peacefully. I experience frequent interruptions by my daughters. I repeatedly request my husband to take our younger daughter away to my in-laws’ room so that I can focus on my work and simultaneously help my older daughter in her online schooling. My husband and I alternately try to attend to our children and fulfil our respective official commitments. But, that’s not enough! I have to spend sleepless nights meeting my deadlines’ (Event Manager).

Professional dissatisfaction

During COVID-19, job dissatisfaction has increased due to the absence of direct physical interaction with colleagues and isolation from the professional work environment. There is a fear that out-of-sight from the employer and the organization may limit the opportunities of reward (Cooper & Kurland, 2002). While working from home, employees are under constant pressure to perform and establish their potential (Darcy, McCarthy, Hill, & Grady, 2012; Sturges & Guest, 2004). Sheva and Brittany grappled with guilt and shame because of the loss of productivity and exhaustion in simultaneously managing the twin identities of mother and professional. Both were worried that concurrent appearance with the children in the video calls might lead their seniors to doubt their commitment, adversely affecting their career growth (Arthur & Guy, 2020).

In our survey, 77% of the remotely working women expressed professional dissatisfaction with this new work arrangement. This was explicitly indicated by women involved in teaching, research and information technology. Whether engaged in educating school children or those handling adult college students, all academicians had similar views.

‘Online teaching doesn’t allow me to connect to the students due to their physical absence. Students seem distracted and lack adequate motivation to participate in learning. At times, I feel that I cannot engage them effectively due to this digital teaching method’ (College Professor 2).

Similarly, Shruti, a young girl who recently joined a research institute, said, ‘my home is very far away from my workplace. During the pandemic, I preferred to work from home rather than taking the risk of commuting to my office. As a result, I was unable to participate in some important projects in my organization. Another colleague who frequently visited the office got better opportunities due to closer interaction with the seniors. This has negatively affected my career growth at such an early stage of my professional life’ (Researcher 1).

Motherhood Penalty

In a normal situation, mothers’ demand for flexibility in their work schedules puts them in a less competitive position than their female and male colleagues with no childcare responsibilities. Though it may facilitate them to strike a work–family balance, it has many unintended consequences often expressed in the ‘motherhood penalty’ (Correll, Benard, & Paik, 2007). They are stereotyped as professionally less capable by the employers (Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2004). Their commitment to the job is considered doubtful (Benard, Paik, & Correll, 2007). As a result, the labour market penalizes mothers by denying them wage hikes and promotions (Benard & Correll, 2010; Budig, Misra, & Boeckmann, 2012). This bias against working mothers seems to have enhanced during the current pandemic. It is likely to negatively impact their future career graph or what Cooper (2020) describes as an ‘unprecedented risk of experiencing a pandemic-size motherhood penalty’.

Divya found herself in a similar situation. While both Divya and her husband work in the IT industry, she has to reschedule her official presentations and meetings to fulfil the needs of their little children. She is a qualified, skilled and hardworking employee. She said, ‘on several occasions, I am unable to accept important job assignments, make early departures from the office, request an emergency leave, etc., all of which has led to a loss of promotion and increments. This adversely affected my professional growth, despite all my efforts at attaining assessment parameters of the organization’. Such professional dissatisfaction worsened due to work from home arrangements. ‘The additional burden of domestic responsibilities and home-schooling of children tend to interfere with my enhanced pressure of work commitments. Now I am planning a job switch-over in the expectation that other organizations may value my sincerity on a more egalitarian platform of performance’ (IT Professional 1).

Challenges of Travel to Workplace

All working women were not fortunate enough to exercise the option of work from home. Jobs like those of healthcare workers, bankers, media, etc., cannot be performed remotely and require travel to the workplace. The same applies to women employed as daily wage earners or those in low-paying informal sector jobs. Thus, while juggling domestic responsibilities, they are forced to bear the mental stress of bringing home the increased risk of COVID-19 from interacting with varied sections of people at the workplace and while commuting.

Risks at the workplace

Women employed in essential services suffer from a higher threat of infection because of their proximity to patients and clients. Despite using personal protective equipment (PPE) like face masks, gloves and gowns, the risk of contamination through surfaces may still exist (Ozenen, 2020). Any loss of vigilance or mistake may spread the virus throughout the workplace and to the employees’ family members. In our qualitative survey, all 17 women travelling to their workplace were worried about this.

Tanisha, a 56-year-old gynaecologist, lives in a family of four members, including an adult daughter and 90-year-old mother-in-law. She told us that ‘in the present situation, my profession is filled with risks. I tried my best to fulfil my commitments by attending to the existing patients and successfully conducting several deliveries. Despite taking all the precautionary measures like wearing a PPE kit in the nursing home, sanitizing my belongings frequently, etc., I tested Covid positive. Since my daughter helped me with domestic responsibilities, she too got infected because of me. Thankfully our timely action prevented the infection from transmitting to my husband and mother-in-law’ (Doctor).

Surbhi continued to visit the dispensary during the pandemic and expressed her fears in this regard. ‘My job is to counsel patients regarding their medicines, so I often come into direct contact with them. Also, some people are not ready to properly follow the norms of physical distancing and wearing face masks. Such instances raise my stress levels. I am always worried about catching an infection and transmitting it to my family members’ (Pharmacist).

Eittee did not have the work from home option because banks had to stay open. She experienced objections by people in her apartment due to her daily commute to the workplace. This behaviour was because of the stigma linked with the spread of the virus from the bank, as the work involves a lot of interaction. Nevertheless, she says, ‘while at the bank, I take all preventive measures such as maintaining a physical distance from colleagues and clients, wearing a mask, and sanitizing my things. I eat on a separate desk and do not share my food with anyone. Unfortunately, their apprehensions came true when 21 people tested Covid positive in my Bank branch. Though I was not infected, my anxiety persists’ (Banker).

Risks of commuting to workplace

Commuting is an integral part of women’s labour market engagement. It is known that women prefer shorter work trips than men, measured in terms of time travelled or distance covered between the place of residence and workplace (Fanning Madden, 1981). Part of these differences may be explained in terms of the disproportionate burden of domestic responsibilities at home, which forces women to shorten their commuting time (MacDonald, 1999).

Given the commuting constraints, the start of the metro service in Delhi in 2002 marked a milestone by providing a gender-sensitive means of public transport. It facilitated women from diverse occupations to overcome the domestic restrictions and enter the labour market. Swati, the administrative head, and Komal, the marketing executive, separately said, ‘it was because of the availability of metro connectivity between my home and workplace, which helped me convince my marital family to allow me to work outside the home’. In the pre-COVID-19 times, nearly 50% of the 145 working women in our quantitative survey were regular metro riders and used this means of transport for commuting to their workplace. Substantiating this finding, Preeti said, ‘metro is my lifeline because it is a reliable, dependable, and a safe means of commuting for me. It saves my time as I no longer get caught in unpredictable traffic jams on the roads of Delhi. I feel relaxed and comfortable while riding back home. It also gives me personal space to talk to my friends and colleagues’ (Communications Manager).

Perception of Risk by Users of Delhi Metro

The COVID-19 pandemic posed a challenge to the usage of public transport. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that people should avoid closed and crowded places. They should maintain a physical distance of at least one metre between themselves (WHO, 2020). However, this measure of social distancing conflicts with the very concept of public transport, which millions of people use for commuting to their workplace each day. Moreover, metro coaches tend to be overcrowded during peak office hours, carrying passengers much ahead of their permitted capacity (Musselwhite, Avineri, & Susilo, 2020). Hence, one cannot avoid touching the commonly used surfaces like elevators, handles, handrails, seats and doors, which may also enhance the probability of contagion. It is also believed that the longer the duration of the journey in public vehicles and the higher the density of people commuting together, the greater is the duration of exposure and risk of contamination (Tirachini & Cats, 2020).

The resulting psychological stress of getting infected due to overcrowding in a means of mass transit altered the perception of women towards the utility of metro (Tayal & Mehta, 2021). To capture this dimension, we enquired from our entire quantitative sample of 462 women about their willingness to use the metro during the current pandemic. 33% of them said they would not use the metro during the pandemic while 45.2% raised doubts about the possibility of using it regularly. Only 22% gave us an affirmative response.

Such a preference change was depicted by Preeti and Swati as well. While Preeti chose to travel to her place of work with her spouse in their car, Swati became dependent on hired auto-rickshaws. According to Preeti, ‘in the current pandemic situation, I do not consider it advisable to use the metro. The overcrowding problem makes it impossible to follow the physical distancing guidelines. Moreover, my family won’t allow me to commute to the office in the metro. Hence, my husband helps me overcome the commuting problem’.

However, women like Palavi and Anshu, who cannot afford to utilize the services of a personal or hired vehicle, tend to continue using Delhi metro. In this context, Palavi said, ‘I do not want to use the metro during the pandemic, but I have no other option’. Citing her experience of using the metro in the current situation, she added, ‘initially, when the Metro re-started functioning in September 2020, the guidelines about physical distancing, mask-wearing, and sanitization were followed. However, over time people seem to be tired of following the rules. They have started crowding and pushing during peak office hours. They are now taking the Covid-19 scare lightly’ (Palavi – Administrative Assistant and Anshu – Researcher 2).

Risks Experienced by Non-users of Delhi Metro

Pranusha is a sound engineer working with a media house. Her working hours extend from 3 a.m. to 2 p.m. She cannot use the Delhi metro. Given the safety issues due to travelling in the early morning hours, Pranusha uses an office cab with colleagues to commute to the workplace. The onset of COVID-19 enhanced her problems. She said, ‘I can't follow the norm of physical distancing in the official cab which carries three to four colleagues simultaneously. Instead, I started using a privately hired cab in which I travel alone to my office. This kind of a trade-off has raised my stress levels of commuting alone with a stranger at 3 am’ (Media).

The commuting problems and risks are much more intense for women from the lower-income strata. In this regard, we interviewed four migrant women who are working as daily wage earners in different manufacturing units. All of them constitute migrant workers from the states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Their average education level is secondary school. Most women are paid based on 12 hours of work per day. Their average monthly family income is in the range of Rs. 15,000 to Rs. 20,000. They cannot afford to use the metro for commuting to their office because they would have to incur a monthly expense of Rs 2400. Vinita, a widowed woman, said, ‘during the pre-Covid-19 situation, I tried to minimize my travel expenses by boarding a shared auto-rickshaw or bus. During the pandemic, due to social distancing norms, I stopped using shared vehicles. I daily walk for the entire 5 to 6 kilometres between my residence and workplace. Besides physical fatigue, I suffer from extreme anxiety of walking alone on deserted roads at 7 am and 7:30 pm’ (Daily Wage Earner 1).

Self-quarantine or isolation

Women travelling to their workplace suffered from the stress of carrying infection back home. As a result, they felt the necessity of self-isolating from the rest of the family members. In our sample, all the women were willing to quarantine themselves for the sake of the safety of their children and elderly family members. However, just 18% of them could practice it, while the remaining 82% found it impossible due to varied reasons.

Soon after the spread of COVID-19 in her Bank, Eittee isolated herself in a separate room. ‘Earlier, I helped my mother in the domestic duties. But now, I have stopped entering the kitchen and try to maintain distance from the rest of my family members. I wash my utensils and clothes separately. I am unhappy that the entire responsibility of managing the house is a burden on my old mother and sister. Nevertheless, my family is happy that I am employed in a government Bank which provides long-term job security and stability, necessary for a working woman’.

Likewise, Tanisha said, ‘when my daughter and I tested positive for Covid-19, both of us immediately quarantined ourselves. Since then, we have restricted our movement in the house. We keep our belongings separately and take all possible measures of minimizing direct interaction with my old mother-in-law’.

Rani is a 45-year-old healthcare worker in a renowned hospital in Delhi. She lives with her husband, adult daughter and 85-year-old mother-in-law. Given the type of job, she faces a constant risk of catching an infection. She explained, ‘during Covid-19, I am working 24/7 with necessary reporting to the hospital during an emergency. My husband has taken the responsibility of picking and dropping me to-and-from the workplace. Given the risks that both of us go through daily, we have no option but to isolate ourselves on a separate floor in the house. It seems like - my life itself is in quarantine for so many months now’ (Senior Nurse).

The commonly cited constraints for the inability to quarantine were domestic responsibilities, small residential space and the presence of small children. Swati said, ‘I alone bear the burden of all the household responsibilities and my children are not mature enough to take care of things on their own. Moreover, our small residential apartment doesn’t permit me to isolate myself’.

Preeti also explained, ‘I live in a joint family of 10 members, and given the requirements of such a big family, I do not have the option of confining myself. Moreover, since women in our house share the domestic work burden, I too have to contribute my share of responsibilities during such a rough spell’.

Salary cut and fear of job loss

In our sample, among the set of women travelling to the workplace, 47% experienced salary cuts. This situation was particularly true for women who were informally employed with insecure job tenure. As a result, they could be retained or sacked at the will of the employer.

Palavi lives in a big family of 10 members. Her father and elder brother are businessmen, but the out-migration of employees during the lockdown led to the closure of their factories. Both of them were facing financial problems. Palavi found herself in a similar situation.

‘Due to the pandemic, I lost my job in June 2020. With great difficulty, I found another job in October 2020. But due to lack of a written job contract, I am always worried about becoming unemployed again’ (Administrative Assistant).

Swati joined her current job in 2018 and has been working on a contractual basis. At the beginning of the COVID scare in Delhi, her office was closed, and she did not receive any salary. After that, she was assigned some work that could be completed from home for 2 months, but with a salary cut. However, from June, her office started functioning normally. She said, ‘now I visit my office on alternate days. I receive my monthly salary with deductions. They have stopped all increments or compensatory allowances. Now I am apprehensive of job loss’ (Administrative Head).

The worst situation was that of the four daily wage workers in our survey. The onset of COVID-19 was followed by a complete lockdown of the Indian economy. During this time, they were not paid any wages. Due to the absence of a formal contract, they were constantly afraid of losing their meagre source of income. Seema said, ‘the monetary constraints during this phase have made it impossible for me to meet even the basic requirements of our family’ (Daily Wage Earner 2).

Anxiety due to loneliness

In our survey, the problem of anxiety due to loneliness was articulated by three women, two of whom were either divorced or widowed. They lived in a family of two to three members and found it challenging to deal with the prevailing unprecedented situation. In other words, the importance of a family, particularly during such a pandemic, can be judged from their conversation.

Sakshi, a single 50-year-old mother, lives alone with her adult daughter and works at a Delhi airport. During COVID-19, she continued to fulfil her professional responsibilities by visiting her workplace. She said, ‘I am always worried about passing on an infection to my daughter. My daughter tends to fall sick very easily. We have no close relatives in the city to provide us immediate help if either of us catches the virus’. Due to her apprehensions, she got herself and her daughter tested for the contagion several times (Senior Manager).

Anshu, a 28-year-old unmarried woman, lives alone with her widowed mother. She commutes to her workplace using Delhi metro. The nearest metro station from her home is 4 km away, and this stretch is not safe for women commuters because of the presence of a wine shop on the route. Several instances of eve-teasing are experienced by women. Anshu’s anxiety also arises from the road’s isolated look due to the limited or partial opening of the economy after the lockdown. She adds, ‘I have no family member who can help me by picking me up from the metro station during the late evening. In addition to the fear of infection, my safety on a deserted road causes a lot of stress for my mother and for me’(Researcher 2).

A similar expression of distress was visible from our interview with Vinita, the daily wage worker who walks alone during dawn and dusk to and from her workplace (Daily Wage Worker 1).

Common Set of Challenges

In addition to the distinctions explained above regarding the issues confronting women based on their work arrangements during the pandemic, both sets of women shared some common sources of anxiety and distress.

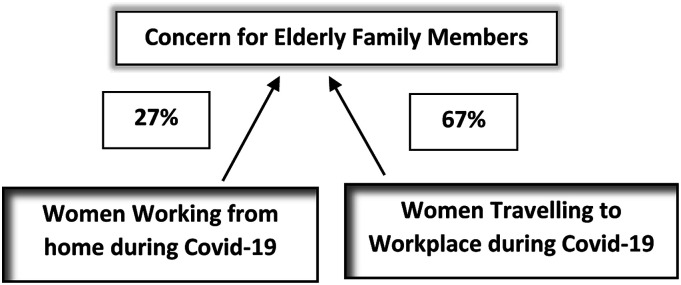

Concern for elderly family members

Care for elderly family members is another vital responsibility traditionally assigned to women (Singleton, 2000). Societal and cultural values endorse daughters or daughters-in-law as natural caregivers for their parents and parents-in-law than sons of the family (Doress-Worters, 1994). The pandemic has brought about a rise in their mental burden for the safety of older people. The reason being, with an increase in age, the body’s immune system becomes weak, making them more vulnerable to infection than the younger people (Sundararajan, 2020).

In our survey, 23 women were co-residing with elderly family members. Among them, 27% of those working from home expressed their concern for such members. This proportion was relatively higher at 67% for those travelling-to-workplace (Figure 3). The difference may be due to more apprehension suffered by the latter section of women about bringing infection home from their workplace.

Figure 3.

Work Arrangement of Women and Concern for Elderly Family Members. Source: Authors’ creation from qualitative survey.

Rani and Tanisha were less worried about their health because the risk is a part of their profession. Both of them suffered from far greater anxiety for their old mother-in-law. Even strong measures like self-quarantine could not lay their fears at rest. Tanisha said, ‘my mother-in-law is asthmatic and is much more vulnerable to infection. All of us constantly monitor her health. We repeatedly get ourselves tested for Covid-19’.

Eittee shared a similar feeling for her sick father. She said, ‘My father had a jewellery shop a few years back. But due to a high level of diabetes and ill health, he stopped working and stayed at home. I am always stressed about catching an infection from my Bank and getting it back home. While, at home, I keep away from directly interacting with my father’.

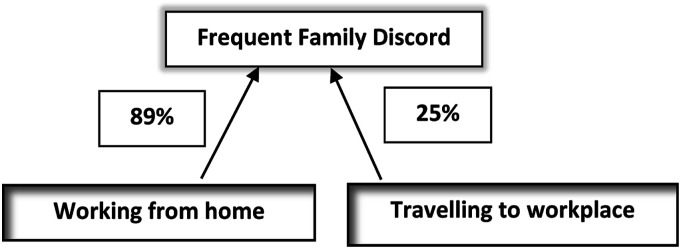

Frequent family discord

In general, factors like social distancing, stay at home, fear of infection, limited physical access to a social support network, disappointment, exhaustion, financial losses and stigma are likely to increase the levels of arguments, disagreements and conflicts between couples and among family members due to proximity of the entire family over a prolonged duration (Kaukinen, 2020; Sharifi et al., 2020). The frequency of such discord and magnitude of discontent generated from it may persist longer when the women are working from home rather than when they can move out of the house to their workplace. We found that among the women working from home, 89% shared their experiences of arguments and clashes in the family. In comparison, 25% of those travelling to the workplace found themselves in similar conditions (Figure 4). Also, the phenomenon was primarily linked with the 17 married women co-residing with their in-laws.

Figure 4.

Work Arrangement of Women and Frequent Family Discord. Source: Authors’ creation from qualitative survey.

The problem of financial constraints aggravated during COVID-19 and was an important reason for quarrels among the couples in our study. Tyesha lives in a small family of four members, constituting her husband, mother-in-law and 4-year-old child. Her husband is educated only up to the ninth standard and is involved in the transport business. She said, ‘my husband is an alcoholic, and this is the prime reason for frequent clashes between us. Disruption of his business due to Covid-19 and no work enhanced his alcohol requirements. My parlour was also shut down for five months, and my employer put me on unpaid leave. With the re-opening of the parlour in September, I received payment on a daily basis depending on the amount of work I contributed. The resulting financial tussle gave a reason for my mother-in-law to criticize me for not opting for a more secure job of a government school teacher’ (Beautician).

Komal works in the social media department of a consulting company. Her husband has a business of rental cars, and her brother-in-law has a tours and travels company. Her family was not keen on her working outside the home. They prefer that Komal uses her marketing skills for the family business. With the onset of the pandemic, their business suffered a setback due to financial losses. Komal said, ‘such adverse circumstances have given my marital family another alibi for blaming and dissuading me from working. On the other end are my parents, who are of the view that I should continue making efforts and not leave my job…tumne itne padai aur mehanat ghar batane ke liye nahi kari hai (meaning you did not study and work so hard to sit at home)’.

Lack of sharing of domestic work burden was also a common reason for conflict in the family. Alina lives with her husband, in-laws and 6-year-old son. Her husband works in a government organization and does not have the work from home option. During the pandemic, her official work pressure increased a lot. She said, ‘my son being small, needscomplete attention and help in attending online classes. My in-laws are very demanding and uncooperative. In the absence of hired domestic help, constant taunts of my in-laws have made it extremely difficult for me to manage things’. As a result, ‘I often lose my patience. My husband and I frequently get into arguments on the division of responsibilities…and my in-laws blame me for my inability to manage the house efficiently’ (Research Consultant).

Concern for children

In our study, out of 22 married women, 19 had school-going children (below 18 years). Among them, 52.6% were worried about the educational performance of their children, and 73.7% expressed their concern for the physical and mental well-being of children. Both these dimensions are linked with the problems arising from the new digital education system and home restriction.

Hashwi is anxious about the learning and progress of her son from home-schooling. She expressed her worries, ‘my son is studying in 9th standard. While at home, he is no longer following any routine. Most of the time, he is distracted while attending online classes. He is not taking his schooling and education seriously. He is prone to sitting on the laptop and surfing the internet. My husband and I have to maintain a constant vigil on him. An increase in screen time has affected his eyes. He complains of pain in his eyes but continues with his new habit of playing online games and chatting with friends’ (School Teacher 4).

Preeti said, ‘my daughter is currently in the 10th standard and faces immense pressure due to the board exams. Her regular school hours from 9 am to 1:30 pm are followed by online tuition classes from 3 pm to 7 pm. After that, she spends time on revisions, completing assignments and projects, etc. I don't have to monitor or pressurise my daughter to study, but my apprehension is about the long-term effects on her overall health due to lack of physical activity’.

In a similar state of mind, Leena said, ‘it’s only after a few years that we will be able to understand the actual impact of home confinement and loss of interaction with the peers on our children’s overall development’ (Executive Officer).

It is feared that screen addiction may generate several psychosocial problems among children. Some observed emotional variations among children, like restlessness, concentration difficulties, boredom, increased demand for parental attention, rebellious outbursts, etc., may indicate the onset of such problems (Adıbelli & Sümen, 2020; Panda et al., 2021). In our interviews, Swati and Meenu talked about similar behavioural changes in their children. Both of them have two sons in the age group of above 10 years.

‘They no longer listen to me and obey me. They have stopped cooperating with me and often argue with me on little things. At times, I lose my patience and strength to handle them’ (Swati).

‘My boys keep complaining about restrictions on their mobility and socialization with friends. They have become aggressive and irritable. Frequent sibling spats on minor issues has raised my concern for them’ (Meenu).

Ideal Motherhood

Working mothers also suffer from the guilt arising from the societal expectations that it is their responsibility to devote significant amounts of time to their children (Clark et al., 2020). The physical absence of mothers from their children is perceived as a deviation from what is expected of an ‘ideal’ mother (Maclean, Andrew, & Eivers, 2021). At times, they are also made to juggle with the feeling that failure to conform to the motherhood standards will ultimately harm their child’s physical and emotional development (Borelli et al., 2017).

Ritu is often criticized by her in-laws for not being a perfect mother. She lives in a family of six members that includes her husband, in-laws and two children aged 5 and 8 years. She states, ‘my father-in-law is a retired army officer and has played a significant role in maintaining discipline in the house. He has always been critical of my parenting style. He believes that I cannot fulfil my prime responsibility of inculcating values in children unless I spend sufficient time with them. Covid-19 pandemic, work from home, absence of hired domestic help, etc., has provided him an excuse to point fingers at me and question my ability to fulfil children’s requirement’ (School Teacher 1).

Facilitators or Coping Strategies

The COVID-19 pandemic has proved to be a testing time for women’s ability to balance several aspects of their professional and personal life. The success of their efforts depends not only on their familial support system but also on their own ability to find ways of dealing with the crisis. Thematic map 2 in Figure 5 provides an overview of the factors that facilitated the working women in study, irrespective of their work arrangement to navigate through the challenges posed by pandemic.

Figure 5.

Thematic Map 2 for the Common Facilitators or Coping Strategies for Women in the Two Work Arrangements. Source: Authors’ creation from qualitative survey.

Family Members’ Share Domestic Work

Working women can fulfil their dual responsibilities if they have a support system at home. The hiring of domestic help is one such option that can reduce the burden of daily household chores. Our quantitative survey of 145 working women showed that during the pre-COVID-19 situation, 38% of women had part-time domestic help, 7% had the support of full-time help and 55% had no such benefit. However, during COVID-19 and the ensuing lockdown, the families discontinued the entry of any outside help, and women were left alone to manage everything independently (Borah Hazarika & Das, 2021).

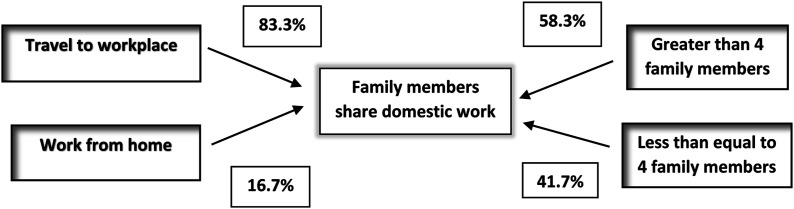

Formally employed paid help can partially reduce the physical work burden, but it has to be supplemented by family members’ support (Aycan & Eskin, 2005). Our qualitative interviews showed that in the case of 12 working women, family members shared domestic responsibilities. In terms of factors (Figure 6), women travelling to their workplace were more likely (83.3%) to get help and support than those working from home (16.7%). Also, with an increase in family size to more than four members, sharing responsibilities becomes more common.

Figure 6.

Factors Linked with the Sharing of Domestic Work by Family Members. Source: Authors’ creation from qualitative survey.

Surbhi and Preeti live in a big joint family of nine or more members. In their families, women in the house have divided domestic duties among themselves based on their availability after meeting their professional commitments. Due to the absence of paid help during the pandemic, the burden of responsibilities increased, but the sharing pattern continued. Surbhi said, ‘I visit the dispensary between 8 am and 2 pm. In the morning, my sister-in-law manages all the kitchen work. In the afternoon, I wash the utensils and clean the house. We prepare the evening dinner together. Our mother-in-law and great grandmother take care of the three children in the family’.

Spousal Cooperation

Among all the family members, the spouse or partner’s role is the most important. A negative relationship exists between spousal contribution to domestic responsibilities and the magnitude of women’s inter-role conflict (Aycan & Eskin, 2005). A supportive husband may act as a buffer, protecting the wife from experiencing high stress levels (Suchet & Barling, 1986; Erdwins et al., 2001). On the other hand, partners with patriarchal thinking may enhance women’s emotional suffering because, given the traditionally defined roles, they may be forced to feel as if they are not fulfilling the expectations of an ‘ideal wife’ (Rosenbaum & Cohen, 1999).

COVID-19 seems to have marginally impacted the dynamics of the couple relationship. Restrictions on mobility and work from home compulsion forced husbands to share some amount of domestic responsibilities. But they prefer to increase their childcare time rather than engage themselves in any other household work (Craig & Churchill, 2020). Our findings do not depict any such adjustment in the roles played by the spouse. In the cases where the husband always tried sharing the wife’s work burden, the pattern continued in the current stressful situation.

Tanisha praised her husband for his unbridled support over the years. ‘In the absence of the cooperation of my husband, it would have been impossible for me to bear the challenges of a demanding career, particularly during the pandemic’.

On the other hand, Swati had no such expectations from her husband. ‘I never received my husband’s help in managing the household responsibilities along with career commitments. He remains indifferent to my sufferings even in the present situation’.

We utilized the qualitative methodology to explore the possible factors (Table 2) that may explain this variance in the husband’s attitude towards sharing domestic duties and the wife’s distress. In our sample of 22 married women, we found that the spouse’s education level plays a vital role in shaping his approach towards his wife’s problems. Well-educated or professionally trained husbands seem to have a greater understanding of their needs and requirements. They are relatively more accommodating with a lesser patriarchal bent in their thinking pattern. For instance, the spouses of Meenu and Shreya are also college professors. Being in the same profession as their wives, they recognize the demands and problems of teaching adult students. Shreya said, ‘my husband tries not to schedule his classes when I am busy with important meetings with my students’.

Table 2.

Factors Linked with Variance in the Attitude of Husband Towards Wife’s Domestic Work Burden.

| Factors | Support of Husband (22) | |

|---|---|---|

| Shares Responsibilities | Unwilling to Help | |

| Education of Husband | ||

| Not well-educated (9) | 2 | 7 |

| Well-educated (13) | 10 | 3 |

| Work arrangement of wife during COVID-19 | ||

| Work from home (11) | 5 | 6 |

| Travel to workplace (11) | 7 | 4 |

| Co-residence of in-laws | ||

| Yes (17) | 7 | 10 |

| No (5) | 5 | 0 |

| Family size | ||

| Less than equal to four (8) | 7 | 1 |

| Greater than four (14) | 5 | 9 |

Source: Primary survey.

The table shows that the type of work arrangement of the wife during the pandemic is also an important factor that influences the willingness of the spouse to help and support. In the cases where the wife has to travel to the workplace, the husband facilitates the wife’s commuting to the workplace. In this regard, Preeti said, ‘in the current situation, my family didn’t allow me to commute to office in Delhi metro. But my husband helped me overcome this constraint. He asked me to accompany him on his way to the office in their car. Thus, both of us can fulfil our respective official commitments by travelling together to our workplace’.

Rani was filled with appreciation for her husband. She stated that ‘in this distressing condition, my husband is my primary source of mental, emotional, social, and physical support. He has taken the responsibility of picking and dropping me to-and-from the workplace. He also risks his life by helping me transfer corona patients from their place of residence to the hospital. It would have been impossible for me to pursue the career of a nurse without the constant help of my husband’.

However, co-residence with in-laws and a relatively large family size of more than four members emerged as two crucial factors that can constrain or limit the husband’s sensitivity towards the challenges faced by their wives.

‘My husband and my in-laws, have always maintained an unsupportive attitude towards me, despite all my efforts towards keeping all of them happy. Over the past 15 years of my married life, my husband’s thinking pattern has been solely governed by my in-laws' patriarchal perception and behaviour (Smriti, Marketing Head).

Komal lives in a big joint family. The men in her house do not share any household work. Komal said, ‘I am not allowed even to hire domestic help for easing my work burden’.

This observed linkage may be explained in terms of the process of inter-generational transmission of gender ideology (Epstein & Ward, 2011; Halpern & Perry-Jenkins, 2016). Parents’ belief about men’s and women’s rightful roles in our society may directly influence their behaviour towards the daughter-in-law. Indirectly, their thinking pattern may percolate to their descendants. Children learn and imitate the gendered behaviour of their parents’, thus transmitting it from one generation to another. For instance, the extent of a father’s participation in stereotypically female duties may profoundly influence their son’s relative participation in the household tasks (Cunningham, 2001).

Support of In-Laws

Proximity to or co-residence with elderly parents or parents-in-law can provide support for the working women. The importance of this relationship lay in the childcare needs, which grandparents willingly fulfil (Compton & Pollak, 2014). This gives the working mothers a sense of security for their children, facilitating them in performing their job efficiently (Arpino, Pronzato, & Tavares, 2014). Our findings support the fact that working women prefer leaving their children with their in-laws rather than depending on formally employed nannies or maids.

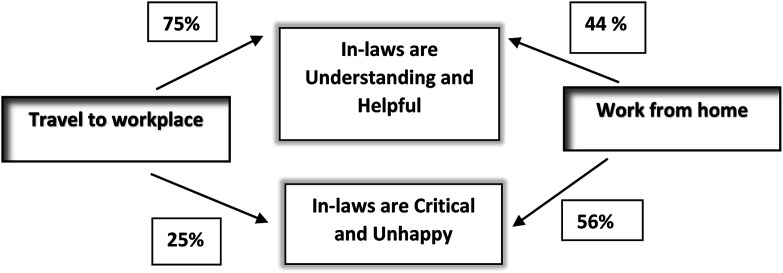

In our sample of 22 married women, 17 were found to be co-residing with their in-laws. Figure 7 shows that this co-residence seemed relatively more beneficial for the women travelling to their workplace. 75% of such women said that their in-laws' understanding and helpful nature helped them fulfil their professional commitments. A few women also expressed their gratitude towards their in-laws for providing a support system during such a stressful time. ‘Despite being so old, my mother-in-law has been extremely caring for my 20 year old daughter. I am grateful to her for being so understanding and accommodating while I stay quarantined to perform my essential responsibility of a healthcare worker’ (Rani).

Figure 7.

Work Arrangement of Women and Supporting Attitude of In-laws. Source: Authors’ creation from qualitative survey.

Among women working from home, 56% said that their in-laws maintained a critical and unhappy attitude towards them even during the pandemic. However, most of them were cited as acknowledging their caring attitude towards the grandchildren. For instance, Divya said, ‘I adjust to the fault-finding nature of my mother-in-law simply because of her love towards my two little children’.

However, it is important to note that the need for such internal support for the children has become more crucial during the pandemic because of the closure of schools, daycare facilities and risks linked with keeping hired domestic help. In this context, we cite the concerns of two women who do not reside with their in-laws.

Ruchi has an 8-year-old daughter. Till February 2020, her father-in-law was alive. She said, ‘he was good support for my daughter. Under his love and affection, I never felt worried for my daughter. Now in his absence, I am filled with apprehensions about my child’s safety. There is no good daycare facility in our area, and such options are also not safe during the pandemic. I am even rethinking of discontinuing my job so that I can attend to my daughter’.

Similarly, Pranusha said, ‘I wish I had my parents or parents-in-law staying with me. I won’t have been forced to send my 4 year old daughter to daycare and depend on outsiders for taking care of her in my absence’.

Quality Time with Family

Despite the various downsides of the pandemic, a few women highlighted that this phase helped them develop closer bonds with their family members. Spending quality time with family can serve as a vital factor in strengthening relationships. It may help them cope with the stress of pandemic, isolation, loss and insecurity (Salin, Kaittila, Hakovirta, & Anttila, 2020).

Pranusha’s husband is a financial expert employed in a leading private equity firm. She said, ‘before the onset of Covid-19, my husband never had time for the family. I alone managed all domestic duties. But his current work from home arrangement has given him time to perceive and accept my burden of multiple responsibilities. Now, he is helping me deal with the difficult situation. In my absence, he cooks the afternoon meal and handles the online education of our daughter. For the first time in my married life, I can enjoy already cooked fresh hot lunch with my small family. I will always cherish these happy moments of togetherness’.

Similarly, Meenu said, ‘I am grateful to my husband for his ability to bring the family together. After a week-long juggle, he manages to counterbalance the weekend atmosphere with smiles and laughs. It is because of his effort that our small family of 5 members can sit together, eat together, and sometimes watch movies together’.

Time for Self

While navigating through the hardships of the pandemic, some women managed to find their ways of overcoming stress. They utilized technology to establish links with the near and dear ones (Drouin, McDaniel, Pater, & Toscos, 2020). Britney and Sheva in Guy and Arthur (2020) explained how connecting with others was one of the ways of self-care and served as a trauma coping strategy for them. Sheva said, ‘I skyped friends for virtual happy hours and started a feminist book club’. Britney added, ‘My colleagues and I developed a group chat where we can brainstorm ideas, provide support for one another, and share our authentic selves’.

In our study, we found that working women were trying to find space for themselves by using a digital platform to upgrade their skills and engage in destressing activities like yoga, dance, etc. We cite the experiences of a few women.

While expressing her dissatisfaction with her job, Divya said, ‘I am enhancing my expertise through online courses. This will help me to explore better employment opportunities and plan a job switch-over’.

‘I utilized the time for learning car driving. Now, instead of depending on hired auto-rickshaw, I can commute to the workplace using my vehicle’ (Tyesha).

‘Online availability of classes has made it easier for people like me to pick up a regular online routine of learning and practicing Kathak. This has saved my time on searching and visiting places for the same. I also feel less stressed about managing multiple responsibilities’ (Meenu).

Swati is a woman from Himachal Pradesh and has always lived close to nature. While staying in Delhi, she missed proximity to trees, plants and flowers. Engaging her children in the activity, she said, ‘I try to relax myself by spending some time on gardening. I have created a small beautiful nursery in my house’.

Discussion and Summary

The major finding of our analysis is that some work–family balance–related challenges are specific to the occupational choices of women as well as their work arrangements or work stations during the pandemic.

Women academicians, information technology professionals, marketing experts and event managers were allowed to work from home. Though they had the advantage of saving time and risks of commuting to the workplace, the volume and duration of their official burden blurred the personal–professional boundaries beyond the usual 8-hour work schedule. They found it difficult to physically restrict tasks related to the office, school, kitchen and living area to the confined spaces in their homes. Remote working also became a reason for job dissatisfaction among those using digital technology for online teaching and those who were conducting all their official meetings through platforms like zoom and teams.

On the other hand, women employed as doctors, nurses, pharmacists, dieticians, bankers, communication managers, executive officers, beauticians, administrative heads and daily wage workers had no option but to travel to their workplace. They suffered from the additional psychological burden of catching an infection in their office or while commuting. The resulting anxiety of contaminating their family members forced a few women to self-quarantine. Others expressed their helplessness because it was practically infeasible for them to maintain a distance from their little children and family members. Moreover, women with informal employment suffered severe financial constraints due to salary cuts. They worked under the stress of losing their job due to the economic downturn that resulted from the lockdown.

Given the risk of commuting using crowded public transport, some women indicated a shift in their preference away from Delhi metro. They felt that travelling in a personal or hired vehicle would help them in maintaining social distancing, thus partially averting the fear of contagion. However, some women were forced to use the metro for their regular commute to the workplace due to a lack of access to alternative means of transport. At the same time, non-metro using working women expressed their anxiety about travelling alone on deserted roads during the late evening. The irony of the situation is that in keeping safe from the risks of COVID-19, many women are placing themselves at a greater risk of insecurity on Delhi roads and public places.

Irrespective of the type of work arrangement, both sets of women had some common concerns. All of them, whether married or unmarried, were anxious about the health of their elderly family members. Mothers were worried about the impact of online education and lack of physical activity on children’s performance and health. They felt that home confinement and restrictions on face-to-face peer interaction are making their children aggressive and ill-mannered.

In examining the factors that facilitated working women to navigate this testing phase, we found that the sharing of domestic work burden by the family members and the caring attitude of in-laws towards the grandchildren played a significant role. Nevertheless, spousal cooperation stands out as a central pillar in the working women’s efforts at balancing work and home. Men with supportive attitudes before the pandemic maintained similar behaviour during the current situation. Education level of the spouse, work arrangement of women, presence of in-laws and family size were the main variables explaining the differences in perception of husband. Well-educated spouses, particularly those engaged in the same occupation as their wives, showed relatively greater sensitivity towards the challenges faced by their wives. Partners also expressed their concern by helping their wife commute to the workplace, thus protecting them from the risks of commuting. On the other hand, women residing with their in-laws, especially in big joint families, experienced a much greater magnitude of hostility from their spouses. This may be because of the patriarchal thinking pattern inherited from the older generation.

A notable feature of our study is the relative differences in the support received by the two sets of women from their spouse, in-laws and other family members. As far as women working from home is concerned, more than 50% of them complained of constant criticism by the in-laws even during the pandemic. 16.7% got help from the family members, and 45% had spousal cooperation in sharing the household work burden. Also, a larger section of these women (89%) experienced frequent family discord due to the presence of in-laws, monetary difficulties and a disproportionate rise in domestic responsibilities. In contrast, the corresponding support system seemed more potent for the women travelling to their workplace. Family members of 83% of them shared household responsibilities. In-laws of 75% were understanding and helpful towards the professional compulsions of their daughters-in-law. Spouses of 65% cooperated with them in a varied manner. Additionally, a smaller proportion of them women (25%) witnessed instances of family discord.

Such observed disparities between the women based on their work arrangement may be explained in terms of the displaced aggression theory of psychology (Hoobler & Brass, 2006; Liu et al., 2015). The American Psychological Association defines displaced aggression as a defence mechanism whereby the individuals are often unable to confront the stress generator source directly. Hence, they may turn towards a less threatening person(s) to vent out their frustrations (Chung, Chan, Lanier, & Wong, 2020).

For example, a woman annoyed by the critical remarks of her mother-in-law may argue with her spouse instead of directly expressing her anger against the elderly family member. Due to physical detachment from close friends, she may not be able to release her stress outside the home by sharing her feelings with them. It is also not possible for her to travel to her workplace and move away temporarily from the source of stress. Hence, this form of displaced aggression onto other family member(s) is likely to trigger an unintended chain reaction within the house. The spouse may also dissipate his professional frustration on the children. Similarly, the mother-in-law may argue with her other co-residing son (s) and daughters-in-law. The consequence of this displaced interpersonal aggression is an environment of hostility within the family. However, in the case of women travelling to the workplace, mobility away from home or source of stress provides them the option to share their feeling with colleagues and friends. They may also vent out their anxiety outside the domestic sphere either on subordinates or on any other person who is less likely to retaliate or is more likely to understand such negative outbursts of emotions. Thus, they can displace their aggression outside the four walls of the house. Also, fear of risks due to travelling outside the home is likely to divert the spouse’s attention from the underlying issues of conflict to concern for the well-being of the wife. The outcome may be an atmosphere of cooperation and support in the family.

Amidst this interplay of disabling and enabling factors, a few women devised coping strategies by utilizing the technology and squeezing out time for self-enhancing activities. They also garnered memories of spending quality time with their spouse and children.

Conclusion

The paper finds that the COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly imposed enormous challenges on the lives of working women in the Delhi-NCR region. The gravity of these challenges varied depending upon their occupational compulsions, workstation, that is, office or home, and familial support systems.

Working women’s experiences during such an unprecedented crisis force us to learn several lessons and strengthen our efforts towards generating an egalitarian society so that we can prevent our economy from suffering severe long-term setbacks post-COVID-19. The pandemic provides us with an opportunity to dismantle gender stereotypes and enable extensive behavioural change that can help us discard the belief that unpaid domestic care work is automatically women’s work. Instead, it is a combined responsibility that men and women must equally share in the family. It is time that our educational system, cultural settings at home and organizational policies sensitize boys and men to acknowledge and contribute to the unequally distributed burden of unpaid care work traditionally borne by the girls and women. The school curriculum and textbooks should lay the foundation for gender-equal thinking patterns at the early stages of education. At home, recognizing women as equally crucial income-earning family members as men may help dismantle the generationally transmitted patriarchal attitudes. Organizationally, men should be encouraged to opt for flexible work schedules and paid family leave so that they can participate in the care responsibilities of the household on a platform of equality. This will facilitate companies in mitigating biases against working mothers.

The pandemic has exacerbated and highlighted the invisible and unrecognized nature of unpaid domestic care work that is borne disproportionately by women. If our data systems can capture this, and if our policy frameworks can develop enabling systems that can recognize, reduce and redistribute unpaid care work, the pain that women have suffered globally during this phase will not be in vain.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the Indian Council of Social Science Research and their IMPRESS project team for sponsoring this research; Professor Alakh N. Sharma and his team at IHD for inputs and support; anonymous reviewers for very useful comments; our team of investigators and interns, Jaswant Rao Gautam, Anisha Yadav, Shweta Sharma, Swayam Singh, Tanvi Rao, Amarjeet Singh Lamba, and Adarsh Mishra; and most importantly, all the respondents for their valuable inputs.

Appendix.

Table A1.

Description of the Sample (n=30) of Working Women.

| S. No. | Occupations | Name of the Respondent | Work Arrangement (during COVID-19) | Personal Attributes | Family Features | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Completed Education | Marital Status | Number of Members | Education of Husband | Co-Residence of In-Laws | Presence of School-Going Children or Sibling | ||||

| 1 | Administration | |||||||||

| a | Administrative Assistant | Palavi | Travel to workplace | 26 | Post graduate | Unmarried | 10 | Not applicable | Not applicable | No |

| b | Administrative Head | Swati | Travel to workplace | 41 | Post graduate | Married | 5 | Not well-educated | Yes | Yes |

| c | Executive Officer | Leena | Travel to workplace | 49 | Graduate | Married | 4 | Well-educated | No | Yes |

| 2 | Academics (teaching) | |||||||||

| a | College Professor 1 | Meenu | Work from home | 53 | Above post graduate | Married | 5 | Well-educated | Yes | Yes |

| b | College Professor 2 | Shreya | Work from home | 55 | Above post graduate | Married | 3 | Well-educated | No | No |

| c | School Teacher 1 | Ritu | Work from home | 35 | Graduate | Married | 6 | Well-educated | Yes | Yes |

| d | School Teacher 2 | Rishika | Work from home | 35 | Graduate | Married | 6 | Well-educated | Yes | Yes |

| e | School Teacher 3 | Ruchi | Work from home | 36 | Graduate | Married | 4 | Well-educated | No | Yes |

| f | School Teacher 4 | Hashwi | Work from home | 39 | Graduate | Married | 6 | Well-educated | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | Academics (research) | |||||||||

| a | Research Consultant | Alina | Work from home | 31 | Post graduate | Married | 5 | Well-educated | Yes | Yes |

| b | Researcher 1 | Shruti | Work from home | 25 | Post graduate | Unmarried | 5 | Not applicable | Not applicable | Yes |

| c | Researcher 2 | Anshu | Travel to workplace | 28 | Above post graduate | Unmarried | 2 | Not applicable | Not applicable | No |

| 4 | Banker | Eittee | Travel to workplace | 25 | Post graduate | Unmarried | 4 | Not applicable | Not applicable | No |

| 5 | Beautician | Tyesha | Travel to workplace | 31 | Graduate | Married | 4 | Not well-educated | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Daily wage worker | |||||||||

| a | Daily Wage Earner 1 | Vinita | Travel to workplace | 41 | Secondary | Separated or divorced | 3 | Not applicable | No | No |