Abstract

Objectives

The current study sought to qualitatively characterize the experiences of American users in a recent open trial of the Horyzons digital platform.

Methods

In total, 20 users on Horyzons USA completed semistructured interviews 12 weeks after their orientation to the platform and addressed questions related to (1) the platform, (2) their online therapist, and (3) the peer workers and community space. A hybrid inductive-deductive coding strategy was used to conduct a thematic analysis of the data (NCT04673851).

Results

The authors identified seven prominent themes that mapped onto the three components of self-determination theory. Features of the platform itself as well as inter- and intra-personal factors supported the autonomous use of Horyzons. Users also reflected that their perceived competence in social settings and in managing mental health was increased by the familiarity, privacy, and perceived safety of the platform and an emphasis on personalized therapeutic content. The behaviors or traits of online therapists as perceived by users and regular contact with peers and peer support specialists satisfied users’ need for relatedness and promoted confidence in social settings. Users also described aspects of Horyzons USA that challenged their satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, highlighting potential areas for future iterations of the platform's content and interface.

Conclusions

Horyzons USA is a promising digital tool that provides young adults with psychosis with the means to access tailored therapy material on demand and a supportive digital community to aid in the recovery process.

Keywords: psychotic disorders, social media, qualitative research, social networking, mental health services

Introduction

Digital interventions supplementing standard care for first episode of psychosis

Each year, about 100,000 adolescents and young adults in the United States experience a first episode of psychosis (FEP). 1 Specialized early intervention services for FEP, known as coordinated specialty care (CSC), are effective in symptom reduction, relapse prevention, and improving social functioning through a suite of clinical and peer-led services.2,3 These services, however, may confer benefits that are not sustained over time.4,5 Considering these challenges, digital technology presents novel opportunities for providing young adults with FEP with continued evidence-based recovery support beyond traditional outpatient mental health settings and offers a step-down model across the so-called “critical period.”6,7

The arrival of different formats of digital interventions for FEP (e.g., internet-, mobile phone-, or virtual reality-based applications) has hastened consideration of how such tools can promote “radical change” in early intervention by overcoming barriers to access and delivering individualized treatment. 8 Prior research indicates that young adults with FEP have a fluency with and desire for technology that is comparable to their peers in the general population, suggesting that the integration of such technology into routine care practices for FEP may be well-received. For example, many young adults with FEP own smartphones and use the internet and social media daily. 9 Young people with FEP also respond positively to the idea of receiving mental health support online, with many actively seeking information about and support for their mental illness through social media.9,10 Furthermore, digital interventions and apps are viewed favorably by young adults with FEP as a destigmatizing strategy that can enhance access and expand the reach of available services.8,11 These findings hold promise for the uptake of digital mental health interventions deployed either in isolation or alongside CSC.

Adapting Horyzons for an American setting

Digital interventions that adopt a social media framework may hold appeal for young adults with FEP seeking support for various aspects of social recovery, especially perceived social support, loneliness, and self-efficacy. 12 Among the available digital interventions for individuals experiencing FEP, the Australian-developed Horyzons platform is unique in this regard. Based on the moderated online social therapy (MOST) model13–16 and informed by self-determination theory (SDT), 17 the Horyzons digital intervention blends interactive therapy material, peer-to-peer social networking, and expert moderation. Therapy content on Horyzons is grounded in cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness practice, focusing on several common mental health concerns such as social anxiety, generalized anxiety, depressed mood, and social functioning. A community space, structured much like other social media communication feeds, allows for peer-to-peer networking moderated by peer support specialists (PSS). Both the therapeutic content and the community space are moderated by expert clinicians who monitor activity for safety concerns and tailor therapy material to users’ goals.

Early findings from Australian trials indicate that Horyzons is feasible, safe, acceptable, and beneficial among FEP clients recently discharged from specialized early interventions services. 18 A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in Melbourne, Australia found that Horyzons users were more likely to achieve educational and vocational attainment and less likely to use emergency services than their counterparts receiving treatment as usual (TAU). 19 A secondary analysis of this RCT indicated that users who maintained engagement with both therapy and social components of the platform experienced greater improvements in social functioning and a greater reduction in negative symptoms when compared to TAU participants or Horyzons users who engaged with the social component only or had low engagement overall. 20

Since its development, Horyzons has been implemented outside of Australia including Canada, 21 the Netherlands, 22 and the United States. Preliminary findings from an American adaptation of an earlier version of Horyzons USA showed that users (N = 26) reported fewer psychosis-related symptoms, negative emotions, depressive symptoms, and loneliness at the end of a 12-week period of engagement. 23

Qualitative studies of Horyzons in Australia and Canada have extended these positive findings while highlighting the nuance of user experience within the Horyzons digital environment. Valentine et al 24 reported that some Australian Horyzons users valued the sense of community cultivated on the platform and felt empowered by the peer support they both received and provided. However, others experienced social anxiety, paranoia, or difficulty connecting with the strengths-based framework in Horyzons. Similarly, Lal et al 21 described that Canadian Horyzons users found the therapy content relatable and the community space an effective tool for facilitating access to peer support. However, users also reported concerns about privacy or a lack of Canadian-specific content for finding employment, completing education, or post-discharge care coordination. Taken together, these studies provide valuable insight into the experience of Horyzons at the user level across international settings.

Objectives

Following the initial findings of an earlier version of Horyzons in the United States 23 and in parallel to the Horyzons qualitative studies completed in Australia 24 and Canada, 21 the current study sought to qualitatively characterize the experiences of American users in a recent open trial of the Horyzons platform. The results of this study will inform tailoring of future iterations of the Horyzons platform within the United States as well as ongoing implementation efforts that seek to integrate Horyzons into established early intervention services for FEP.

Methods

Overview

Funding for this study was provided by the State of North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. Ethical review and approval were provided by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (IRB 19-1709).

Participants

Horyzons users consisted of clients (N = 25) from four FEP CSC programs in the state of North Carolina: the Outreach and Support Intervention Services (OASIS) clinic in Chapel Hill; Supporting Hope Opportunities Recovery and Empowerment (SHORE) clinic in Wilmington; Wake Encompass clinic in Raleigh; and the Eagle Program in Charlotte. Clients must have met the following inclusion criteria to participate: (a) Between 18 and 35 years of age, (b) diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorder or other psychotic disorder, (c) actively receiving services at one of the four FEP clinics in North Carolina, (d) absence of suicidal ideation in the month prior to enrollment, (e) no psychiatric hospitalizations in the three months prior to enrollment, (f) no changes in psychiatric medications in the month prior to enrollment, and (e) able to access the internet through a phone, tablet, or computer.

Procedure

All participants consented verbally over HIPAA-compliant Zoom after in-depth review of the consent form with the research coordinator. This consent process was necessary due to circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic and a lack of alternative consent processes at the time of study completion. After completing verbal informed consent and an on-boarding procedure (i.e., creation of an individual Horyzons profile), each participant met with one of four expert moderators to whom they were assigned. Expert moderators consisted of two graduate students in clinical psychology, a master's-level social worker, and a licensed clinical psychologist. Participants met with their assigned expert moderator on a biweekly basis to review progress toward personal goals with the intervention, discuss engagement issues, and receive tailored therapeutic content.

Users also interacted with five PSS from the participating CSC programs in North Carolina who served as peer moderators of the platform's community space. Peer moderators modeled prosocial behavior in the community space, conducted outreach to encourage engagement with the intervention, and facilitated biweekly synchronous activities (hereafter referred to as “Horyzons Hangs”) using Zoom video conferencing. Some example activities during Horyzons Hangs included: Writing epistolary (letter) poems to themselves, family members, or even to their psychosis; playing a jeopardy-style psychoeducation game; having a “meet the moderator” event where users could ask moderators personal questions. Both expert and peer moderators provided safety oversight of the platform.

Users accessed Horyzons USA for a total period of 12 weeks. Additional details about specific features of the Horyzons platform are provided in Alvarez-Jimenez et al. 19

Data collection

Of the 25 users enrolled in the intervention, five were lost to follow-up. All individual user interviews (N = 20) were semi-structured and completed at post-treatment (12 weeks after baseline) over HIPAA-compliant Zoom video conferencing. The interview questions were presented to users in three broad categories, including questions addressing (1) the platform, (2) their moderator (sometimes referred to as “online therapist”), and (3) the peer workers and community space (see the Appendix). The interview guide was designed to elicit expressions of specific user experiences across different aspects of the platform in addition to potential suggestions for improvement. Follow-up questions were asked as needed to clarify user responses. All interviews were completed by the first author (ELP) who had a standing relationship with each user as the research coordinator for the trial and who was not involved with moderation activities on the platform. Virtual interviews allowed for direct audio recordings which were later transcribed by undergraduate and graduate research assistants.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis included univariate statistics of users’ sociodemographic background and platform usage. Platform usage was divided into quintiles of engagement corresponding to no usage, very low, low, moderate, and high. Qualitative analysis was completed using Dedoose and Microsoft Excel software programs. This study adopted a hybrid process of inductive and deductive coding guided by a phased approach to reflexive thematic analysis.25,26 This study also adopted a primarily essentialist epistemological stance, such that the data were assumed to reflect the lived experiences and reality of participants.

Four coders, including the lead research coordinator (ELP), a clinical psychology graduate student (BJS), and two undergraduate research assistants (RT and KB), were involved with the analysis. All recorded qualitative interviews were first transcribed by research assistants and then reviewed for accuracy by ELP and BJS. Prior to coding, all coders reviewed each transcript for familiarization and reflexively journaled initial impressions. Three transcripts (approximately 15% of the dataset) were randomly sampled for reliability coding. With two of the randomly sampled transcripts, all coders inductively coded and subsequently met to resolve discrepancies in code application and organization. A preliminary codebook was defined, and the last transcript selected for reliability was inductively coded. Similarities and discrepancies between coders were discussed and the codebook was iteratively updated. Once intercoder reliability was deemed satisfactory by the analyst team, the remaining portion of the dataset was divided for inductive coding. Inductive codes were preliminarily categorized into groups with shared meaning.

Transcripts were then coded deductively by aligning the inductive codes with the three primary components of SDT (i.e., autonomy, competence, relatedness) which underpin the design of the Horyzons intervention.17,27 SDT proposes that activities that satisfy basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness are intrinsically motivating, thus fostering high-quality engagement. According to SDT, 17 autonomy reflects individual behavior that is self-determined. The basic need for competence reflects that individuals are more likely to engage in a behavior if they feel in control of an outcome that will promote feelings of self-mastery and self-efficacy. Intrinsic motivation is additionally more likely to develop in environments that promote relatedness, described as interpersonal security in feeling as if one belongs and is connected to others. Thus, the coders sought to understand how these three components were satisfied within Horyzons USA and in turn how users experienced them.

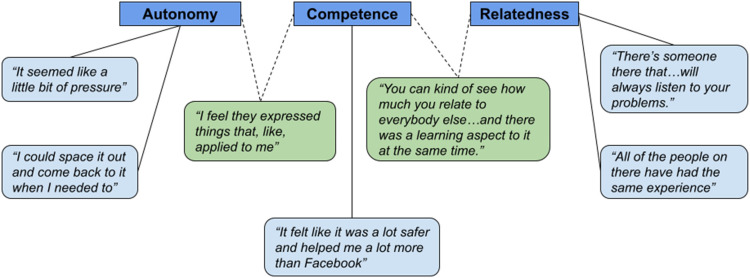

Through weekly team meetings, hybrid inductive-deductive codes were categorized into groups with shared meaning and then organized into broad themes. Once a final thematic map was developed, the coding team defined and named the seven principal themes which emerged from the analysis (see Figure 1). Participants’ quintiles of engagement in the therapy and community components were finally mapped onto their coded feedback to examine the concordance between quantitative usage and self-reported experience of the Horyzons platform.

Figure 1.

Conceptual thematic map.

Results

Participant characteristics

Users were, on average, 25 years old (range = 18–37) and a majority identified as male (76%) and white (63%). A sizable portion of the sample identified as Black or African American (21%). Most users had some college education or higher (76%). Users most often had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (36%), carried a diagnosis of a psychotic spectrum disorder for a median number of 4 years (range = 1–14), and had a median number of 2 hospitalizations across a lifetime (range = 0–5). Additional sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of users are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

| Participants (N = 25) | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Age (M ± SD) | 24.88 ± 4.58 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 19 | 76.0 |

| Female | 6 | 24.0 |

| Race | ||

| White/Caucasian | 15 | 62.5 |

| Black or African American | 5 | 20.8 |

| Asian | 1 | 16.7 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | - | - |

| American Indian or Alaskan native | - | - |

| Other | 3 | 12.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 | 12.0 |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 22 | 88.0 |

| Education | ||

| Middle school or less | - | - |

| Some high school | 2 | 8.0 |

| High school diploma/equivalent | 4 | 16.0 |

| Some college | 12 | 48.0 |

| College degree | 6 | 24.0 |

| Higher than college | 1 | 4.0 |

| Years of education (M ± SD) | 14.16 ± 2.89 | |

| Mother years of education (M ± SD) | 15.29 ± 2.44 | |

| Father years of education (M ± SD) | 14.83 ± 2.71 | |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Schizophrenia | 9 | 36.0 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 7 | 28.0 |

| Schizophreniform disorder | 1 | 4.0 |

| Schizotypal personality disorder | 1 | 4.0 |

| Bipolar disorder with psychotic features | 1 | 4.0 |

| Substance-induced psychotic disorder | 1 | 4.0 |

| Unspecified psychotic disorder | 5 | 20.0 |

| Age at diagnosis (M ± SD) | 21.24 ± 3.52 | |

| Median years since diagnosis (range) | 4 (1–14) | |

| Median lifetime hospitalizations (range) | 2 (0–5) | |

Platform engagement

We observed considerable diversity in engagement with the platform. The sample was divided into relatively equal subsets across the engagement quintiles for therapy and community space usage. Nearly half (48%) of all users engaged with the therapy content at moderate to high levels, while the majority (52%) engaged at low rates or less. Similar proportions of engagement were observed for the community. See Table 2 for additional details on quintiles of user engagement with the platform. A participant-level breakdown of engagement quintiles can be found in the Supplemental materials.

Table 2.

Quintiles of engagement across therapeutic and community spaces.

| Participants (N = 25) | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Therapy usage | ||

| None (0) | 5 | 20.0 |

| Very low (1–2) | 4 | 16.0 |

| Low (3–6) | 4 | 16.0 |

| Moderate (7–11) | 6 | 24.0 |

| High (12–63) | 6 | 24.0 |

| Community usage | ||

| None (0) | - | - |

| Very low (1–4) | 7 | 28.0 |

| Low (5–20) | 6 | 24.0 |

| Moderate (21–44) | 6 | 24.0 |

| High (45–229) | 6 | 24.0 |

User experiences with Horyzons USA

We identified seven prominent themes nested within the three components of SDT in user experiences of Horyzons USA. Table 3 outlines each component, theme, and theme description. Figure 1 illustrates the thematic map used in this study.

Table 3.

Theme names and descriptions.

| Self-determination theory component | Theme name | Theme description |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | “I could space it out and come back to it when I needed to” | Experiences of autonomy through programmatic features of the platform |

| “It seemed like a little bit of pressure” | How intra- and interpersonal components of the intervention impacted autonomy within users | |

| Competence | “It felt like it was a lot safer and helped me a lot more than Facebook” | The familiarity, privacy, and perceived safety of the platform facilitates social competence |

| Autonomy × Competence | “I feel they expressed things that, like, applied to me” | Personalized therapy content can build competence by capitalizing on autonomy |

| Relatedness | “There's someone that will … always listen to your problems” | Certain interpersonal behaviors and traits of online therapists both allow for and enhance meaningful social connections |

| “All of the people on there have had the same experience” | Shared lived experiences of peers and peer specialists facilitated a sense of community | |

| Competence × Relatedness | “You can kind of see how much you relate to everybody else … and there was a learning aspect to it at the same time” | Horyzons Hangs promoted social competence through the comfort of shared experiences |

Autonomy: Issues of control in the digital environment

“I could space it out and come back to it when I needed to.” Users reported that certain programmatic features of the platform helped to promote a sense of personal autonomy, while other features (or lack thereof) sometimes hindered this feeling.

For some users, the act of sharing whenever they felt the need provided a feeling of constant support through their mental health experiences. Users were able to apply autonomy in choosing how they wanted to use Horyzons USA:

“Horyzons is great for just throwing out very quick, succinct thoughts about what's going on in my life and how they relate to my plans for my mental health.” (116;very low therapy usage, low community usage)

“What I also liked was a lot of people were venting. I was able to like kind of decide whether not to respond or just kind of leave them be, but also just understand where they were coming from.” (107; no therapy usage, low community usage)

One user likened the availability of support provided by Horyzons USA to the support one's own parent would provide. For example, the platform offers consistent support that is available for the user when and how they need it. Users can access the platform at their own discretion:

“This is your support if you ever need anything. Like almost like a mother to you. Is what that is. I felt like Horyzons, it was meant just for you and it was like this is for you.” (112; very low therapy usage, very low community usage)

“Definitely offers a safer alternative to doing that because in-person right now is a little risky with the pandemic. Certainly the convenience of being able to talk to anyone who is in that group anywhere, that's another really easy one. I would also say maybe, just being able to sort of put things out there right when they hit my mind – I could just be like ‘Hey I’m just thinking about that’ and open up Horyzons and post about it.” (116; very low therapy usage, low community usage)

Autonomy was also reflected in users’ navigation of the therapy material. One user expressed appreciation that they could take the material at their own pace. Although another user found it difficult to connect with certain therapy activities on Horyzons USA, they valued that the content could be easily tailored to meet their individual goals.

“I could space it out and come back to it when I needed to. You didn’t have to do it all at one time. I thought that was helpful." (103; moderate therapy usage, high community usage)

“Well at first it just seemed like random journeys was like thrown at me … and then I talked to my therapist and she helped me find mindfulness journey and that one helped with me.” (123; moderate therapy usage, low community usage)

In contrast, some found that certain features of the platform's interface limited their ability to move autonomously in the digital environment. Several users indicated that logging into the platform through a browser rather than an app posed a problem for their autonomous use of Horyzons and that they would have accessed Horyzons USA more frequently if there was an easier and quicker digital option to do so:

“So if there was a mobile app, that probably would have been a lot better where I could directly click on it and like everything is at the touch of a button nowadays.” (107; no therapy usage, low community usage)

This limitation restricted users in how they could access the platform, therefore making the support of Horyzons USA seem harder to reach. Another user mentioned not having an app was the largest barrier for using the platform due to their busy schedule:

"The biggest thing was just that I had to get on my computer to access it like fully. And I’ll be more on my phone than on my computer. It's just like for class stuff. But that was the biggest thing that held me back.” (110; high therapy usage, low community usage)

“It seemed like a little bit of pressure.” Certain intra- and interpersonal elements of Horyzons USA impacted users’ sense of autonomy in different ways.

Some users struggled with forgetting to log on or having other obligations distract them from accessing Horyzons USA:

“Sometimes it just kind of got away from me as far as actually logging on.” (106; high therapy usage, low community usage)

“Pretty much entirely the demands of my job. It's basically a 32-hour workweek so… For me personally that is a big jump from a zero-hour workweek. Reacclimating to that… Horyzons has been on the backburner a little bit. I still try to post there when I can but not as much as I would have liked." (116; very low therapy usage, low community usage)

"What held me back was school and work.” (123; moderate therapy usage, low community usage)

Moderators communicated with users periodically about platform use and potential engagements, focusing especially on individuals who were not accessing Horyzons USA regularly. Some users appreciated these reminders and found that they helped facilitate their choice to engage with the platform:

“I think it's valuable because you kind of realize that you’re connected in that way. Like if she wasn’t kind of reminding me or like checking back in with me, I might have been on Horyzons less.” (103; moderate therapy usage, high community usage)

Others felt that these reminders limited their autonomy in choosing when and how to interact with the platform:

“But if he were to say hey if you did the journeys in Horyzons they would help you out a little bit more like … If he didn’t give it to me, it seemed like a little bit of pressure. Like hey kind of get on the site.” (112; very low therapy usage, very low community usage)

Additionally, one user expressed concern about the focus of the platform, as he primarily wanted to connect with other users but felt that this was deemphasized when compared to promotion of the therapy material:

“It feels like to me that the journeys are like the primary focus on Horyzons. And I feel like for me personally I’d rather get to know people better first than to like hey here are journeys, you should go do those instead of like hey meet these cool people, they’re on the website first. They’ll help you out.” (112; very low therapy usage, very low community usage)

Feeling limited in the type of content shared on the community space of the platform was also reported. Tensions between respecting autonomy and adhering to community guidelines for appropriate use of Horyzons USA were reflected in one user's frustration with the PSS when sharing content about personal topics:

“They would say things that I’ve heard a million times before and it made me feel like my opinion was less valid because I haven’t gone through what they’ve gone through. Or that when I spoke of supernatural stuff it was like oh everyone thinks about stuff that way and you shouldn’t be worried. I just felt like there was a disconnect… I couldn't say whatever I wanted… I think they understood me. There's just that… to them my opinion wasn’t as valid.” (105; high therapy usage, low community usage)

Competence: Digital facilitators of mastery

“It felt like it was a lot safer and helped me a lot more than Facebook.” The form and delivery of the intervention reduced barriers to accessing the platform. Specifically, familiarity with technology and comfort with social media allowed users to feel more comfortable and confident when using the site. Users made several connections between Horyzons USA and various social media platforms, including Instagram, GroupMe, Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit. As young adults, many users reported enjoying the platform because it reminded them of the social media platforms they already use. Nevertheless, Horyzons USA stood apart from other social media platforms for its perceived safety and privacy - qualities which accentuated positive gains in social recovery:

“It was very much like other social media. I would log in, post something about something I was doing at the time, I might post pictures of something that I thought was really cool… and I would appreciate the replies.” (116; very low therapy usage, low community usage)

“I thought it was very similar to almost like Facebook. And I liked that a lot about it. But it felt like it was a lot safer and helped me a lot more than Facebook.” (101; high therapy usage, high community usage)

“I think the platform was very user friendly and safe for people who have experienced you know anything with mental illness or mental health. It felt like it was a warm environment.” (114; high therapy usage, high community usage)

This familiarity, as well as the features of the community space itself (e.g., reactions), cultivated an environment where individuals felt more comfortable interacting with others. Specifically, Horyzons USA appeared to facilitate communication that might be more difficult for users during face-to-face social interactions:

“I think meeting people digitally is less stressful for me than meeting people in-person.” (125; low therapy usage, moderate community usage)

“I think virtually you’re more comfortable but in reality when you walk up to somebody it's a whole different thing.” (108; low therapy usage, moderate community usage)

“…it's like a lower barrier of entry. You don’t have to go meet up with a stranger, you can just type a comment and have a conversation…” (120; no therapy usage, moderate community usage)

“I think it was pretty easy because you know if someone posts something you can easily high five it.” (103; moderate therapy usage, high community usage)

However, not all users were initially comfortable and competent navigating the Horyzons USA digital environment. Although eventually they were able to troubleshoot, one user described difficulty utilizing various features of the community space to interact with others.

“It took me a little while to figure out the whole… like reacting to their posts. Or like posting a comment to their post. I thought I was doing alright but I don’t know. I messed something up at some point. But I figured it out eventually.” (106; high therapy usage, low community usage)

Users reported that posts made in the community cultivated a space that reflected their own experiences and identities which, in turn, made them feel more comfortable and self-confident engaging with others:

“I guess seeing everyone post things and maybe posting something that I shared a similar experience with. And then just kind of getting in the… just getting used to posting stuff and liking stuff and it just became really easy.” (101; high therapy usage, high community usage)

However, one user reported finding that the limited range of communication cues on digital platforms posed a challenge for forging connections with others and building mastery in social settings:

“Well, connecting digitally on the phone you can see… like over the phone you can hear their voice and you can see how they say things and their tone and stuff like that. Digitally and over the media… you can’t tell their tone or like… sometimes you can’t tell if they are happy unless they use exclamation marks or stuff like that and you can’t hear them say it. And sometimes the connection is better over phone or in-person.” (123; moderate therapy usage, low community usage)

“I just feel like when you’re in person it's more like you know like instant feedback, instant reactions to people. And you can kind of gauge body language more. But you know virtually, you don’t really… can’t really see how other people are reacting to what you’re saying.” (110; high therapy usage, low community usage)

Frustration not only stemmed from the challenges of the platform itself, but also from the online community. Some users reflected that there was limited client-to-client exchange in the community space throughout the open trial. Since PSS posted more during times of relative inactivity among client users in the community space, some felt that this dynamic did not promote an environment which felt natural or conducive to enhancing mastery in social settings:

“It would be nice to see 100% posts and replies coming from clients. Just personally I like things to be as organic as possible.” (116; very low therapy usage, low community usage)

“I would think it’d improve it if the people who were using it were to like interact with you and more people. So like there’d be more people posting on the newsfeed because I feel like most of the posts were made by like the peer support people. So it kind of felt like you weren’t so much interacting with like you know other people like you. More like peer support people… I could definitely see it being even more helpful if you know like the community was even larger.” (110; high therapy usage, low community usage)

The lack of private one-on-one communication between users was also identified as a shortcoming of the Horyzons USA platform, which, according to one user, additionally diminished the range of social experiences that they were able to practice:

“I thought it would be a lot more like social media. It was definitely a social media, but it wasn’t like your typical social media in terms of like how you were able to interact and comment and DM and things of that nature. So it didn’t feel as social as a typical social media.” (107; no therapy usage, low community usage)

Promoting competence through autonomy:“I feel they expressed things that, like, applied to me.” Several users felt that the therapy material on Horyzons USA provided flexibility through personalization–through individual choice, platform algorithms, and suggestions from moderators–that allowed for increased sense of competence in certain coping skills:

“There were like other options that you could choose if you weren’t happy with the journey you were doing at that particular time. I felt like there was a lot of flexibility… there was like some mindfulness and like some meditations that I looked… different meditations and stuff. Those were helpful.” (103; moderate therapy usage, high community usage)

Although MOST platforms are not designed to replace in-person receipt of services, users nevertheless found that it was a helpful supplement to leverage as desired. Users identified available support on Horyzons USA with an increased ability to work through and manage difficult situations:

“Well, because at first I was dealing with my anxiety. And it was the anxiety journey that I had to do. And I think that helped me cope with my anxiety. So now I think I’m doing better with my anxiety. And it was a social journey that I was doing. And that helped me stop being anti-social.” (102; moderate therapy usage, high community usage)

“If I was going through something and didn’t have my therapist on hand or someone else I could lean to, it was a nice little addition to have to like help me with my psychosis or like give me pointers as to help me through a certain phase or something.” (112; very low therapy usage, very low community usage)

Unfortunately, not all users found a journey or activity that best fit their social and mental health needs. Some users struggled with finding something that applied to the areas they wanted to focus on, or even found that the content altogether did not interest them:

“My biggest challenge was like finding journeys that fit me.” (123; moderate therapy usage, low community usage)

“The content wasn’t as funny as I thought it would be. So I didn’t think it would be something that would make my day more enjoyable.” (105; high therapy usage, low community usage)

Relatedness: Making the digital connection

“There's someone there that … will always listen to your problems.” Users noted that certain interpersonal behaviors and traits of their assigned moderator facilitated opportunities for meaningful social connection.

Some found that moderator support was helpful when listening to their concerns and guiding use of the platform:

“[She] listens to my problems. [She] helps me set goals.” (109; high therapy usage, high community usage)

“I feel like [their] presence just allowed networking to be easier.” (107; no therapy usage, moderate community usage)

“I think it is just the general flow of the meetings. Just being very like, ‘what are some stuff that you are curious about working on? Would doing these journeys or interacting with Horyzons in this way accommodate that need to improve? How do you feel about getting started on that?’ I feel like it was very empowering…” (116; very low therapy usage, low community usage)

Others were primarily interested in their ability to connect with their moderators through similar interests and relatability:

“I think we enjoyed each other's company and we had similar interests. Like sports and you know. He's from like areas where I have family. So it was just… We kind of just had a lot in common.” (114; high therapy usage, high community usage)

“He actually… on our second call he pointed out that he watched a couple hip hop documentaries. So I thought that was like an attempt to relate. And I appreciated it.” (107; no therapy usage, low community usage)

In general, users felt that their moderators’ genuine interest in their personal experiences and growth allowed for improvement in their relationships over time:

“By the first call it was like ‘oh who is this guy.’ But by the second call he had already made it clear that like he was just interested in my growth. And it continued to be that way so it improved.” (107; no therapy usage, low community usage)

“He like seemed to care a lot about who I was as a person and what I go through.” (112; very low therapy usage, very low community usage)

Users were asked about the potential of replacing or supplementing moderator-user relationships with an automated chatbot feature. While a couple of users expressed that a chatbot would be a great way to share their feelings unencumbered by social conventions, most felt that a chatbot simply could not compare to the person-to-person interactions they gained from their moderator:

“The thing about chatbots is that they’re impersonal which is a con. But at the same time you feel a little bit more comfortable telling your thoughts to a wall in your own room sometimes because you’re not comfortable with the response people might give you. So at the same time it's also impersonal which is a pro.” (107; no therapy usage, low community usage)

“I think that would also be helpful. I think personally maybe like both would be helpful. Like an online therapist and a bot. Like it kind of reminds you like of what you need to be doing on the site. Like maybe the bot could check in once a week or once every few days and then the therapist could be like every two weeks. Just to kind of keep you on track.” (103; moderate therapy usage, high community usage)

“I kind of liked the online therapist. So yeah, I would stick with that, not really a chatbot. Cause I liked talking to a person that tries to get to know me and stuff like that.” (123; moderate therapy usage, low community usage)

“All of the people on there have had the same experience.” The PSS also had a significant impact on users. Users mentioned how PSS helped them stay active on the site through attentive commenting and reacting to posts on the community page:

“I think [peer support specialist] in particular… Her and I like… We chatted very frequently. And she asked me like questions about like just day-to-day things and like stuff that I was going through at the time. I think that was helpful because you could see that they’re actually pretty invested in your well-being. And your activity on the site.” (103; moderate therapy usage, high community usage)

“You know I would say it was good that the peer support workers were on top of it and were always active in the community online and making people feel better.” (114; high therapy usage, high community usage)

“One of the peer workers reached out to me and we started becoming… I don’t know if you can really be friends with peer workers but we started talking and… If we made a post all the peer workers would comment and that made me feel like I was really listened to. And that people really have an interest in what I was posting. All the peer workers were very, very nice.” (109; high therapy usage, high community usage)

Similarly, interacting with other users on the community page allowed individuals to enhance their sense of belonging by building social connections through recognition of similar lived experiences of psychosis:

“It is a closed, safe environment and all of the people on there have had the same experience.” (120; no therapy usage, moderate community usage)

“…a good opportunity just to interact with other people that have similar struggles to what I have.” (103; moderate therapy usage, high community usage)

“Well there is certainly the idea that… I don’t want to say exclusivity because it makes it sound super exclusive but there is definitely the idea that it is built for a specific group of people in a specific place in their lives that are dealing with a specific thing. And that is certainly not a bad thing, I think it is very good thing because it allows us to have an almost natural icebreaker the moment we get in there because we all know that at least somewhat that we have something in common. So, with that in mind, that is a good thing… but it is definitely vastly different from random strangers asking to follow you on Twitter because you made some post that they like.” (116; very low therapy usage, low community usage)

Promoting competence through relatedness: “You can kind of see how much you relate to everybody else … and there was a learning aspect to it at the same time.” Several users identified the value of bi-weekly “Horyzons Hangs” meetings in terms of the bond and sense of community forged among those who participated. However, for some, the benefit of these meetings extended beyond the promotion of relatedness. The social component of Horyzons Hangs fostered a host of learning experiences that reinforced aspects of the therapy content on Horyzons and normalized living with symptoms of psychosis which, in turn, facilitated self-efficacy:

“Yeah I think the community aspect and also the meet up that I did with everybody else on… I think that was over Zoom. That was really helpful. It was cool to like play a game with everybody else and kind of hear about their personal experiences and kind of… There was a learning aspect to it at the same time.” (103; moderate therapy usage, high community usage)

“…there was a lot of things on there that we discussed like maintaining relationships, anxiety, and just different things like that… we talked about their problems as far as what their mental disorders were. It was nice seeing other people that were going through the same things that I’m going through.” (124; moderate therapy usage, very low community usage)

“Especially the game that we played… Like you can kind of see how much you relate to everybody else.” (103; moderate therapy usage, high community usage)

Discussion

Primary findings

The authors identified seven prominent themes of user experiences with Horyzons USA which were subsequently mapped onto the three primary components of SDT: Autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Some themes crossed into multiple SDT components. Users identified (1) features of the platform itself as well as (2) inter- and intra-personal factors which either supported or interrupted autonomous use of Horyzons. Users felt their competence in social spaces as well as their competence in managing mental health was increased respectively by the (3) familiarity, privacy, and perceived safety of the platform and (4) an emphasis on personalized therapeutic content. Users’ sense of relatedness was fostered by (5) the behaviors or traits of online therapists or (6) recognition of shared experiences with peers/PSS. This sense of community was harnessed by bi-weekly virtual get-togethers to (7) promote further confidence in social settings through the comfort of shared experiences.

Consistent with prior qualitative studies of digital mental health interventions, 28 we found that many users valued the autonomy and choice with which they could utilize the Horyzons USA platform. In this study, users underscored a variety of features associated with the digital platform itself which promoted self-determined use of the intervention's various components. For example, some users valued that they could complete the therapy material at their own pace, request tailored therapy material from their moderator, or decide whether or how to engage their peers in the platform's social network. Users who commented on these features further expressed their autonomy directly through engagement with the platform, presenting in usage groups across the spectrum in both therapy and community space metrics. Nevertheless, we found that several factors associated with the platform's interface or features of the moderation may have curtailed users’ autonomous navigation of Horyzons USA. Several users desired an app version of the platform, with some indicating that the primary method of logging into the platform (i.e., Internet browser on computer or smartphone) limited the extent to which they used Horyzons USA. Furthermore, although some users appreciated reminders from their assigned online therapist to interact with the platform during periods of disengagement, others reported feeling pressured by such contact. Emphasis placed on completion of therapy material by the online therapist during regular check-ins may have similarly diminished users’ sense of autonomy in choosing how often to use the platform. Those who mentioned these barriers to autonomy tended to have low or very low community usage, yet a range of usage levels within the therapeutic content. It is possible that these barriers may have diminished engagement with the community space over and above decisions of whether or not to engage with the therapeutic aspect of the platform.

While prior research suggests that digital interventions which integrate live human support are more effective than unsupported, self-guided digital programs, 29 varied experiences of autonomy in this study suggest that digital interventions may be most successful when experiences are personalized rather than a one-size-fits-all model. Providing users with a larger range of choices in digital reminders, access, and therapeutic content may promote stronger overall engagement in future cohorts. Future use of MOST platforms should continue to evaluate whether components of the platform's interface (i.e., unsupported digital features or human-to-human interaction) facilitate perceived autonomy support.

In this study, we found that users endorsed varying levels of competence using the social space of the platform. Consistent with past qualitative studies of Horyzons, 24 many users drew parallels and distinctions between Horyzons USA and other forms of social media. While such similarities appeared to lower the barrier of access to the Horyzons platform and conferred a level of “digital mastery,” we found that components unique to MOST platforms, such as the private social network, particularly resonated with some young persons. Users who detailed these aspects of the community space tended to have moderate to high engagement metrics with that aspect of the platform, while those who mentioned struggling in the digital environment tended towards low or very low community usage. The finding that a safe, digital space encouraged some users to feel confident navigating social situations, which may be otherwise difficult to manage in face-to-face contexts, holds promise for digital interventions like Horyzons USA to address prevalent challenges in FEP with social anxiety 30 and general social functioning. 31 However, this finding is tempered by feedback from users who felt that the digital space of Horyzons USA, by design, limited certain types of cues (e.g., tone, body language) that are helpful for gauging social interactions. This finding rings particularly true for individuals who endorse heightened social anxiety. 32 Future development of MOST moderation protocol should consider the extent to which the use of nonverbal social cues (e.g., emojis) by online therapists and peer specialists can impact the development of a user's social mastery in a digital space. Focus on feedback from those with low community space engagement may provide insight into potential areas for improvement.

Due to the closed nature of the platform, the privacy of the community space also resulted in only a handful of users posting on a regular basis, leading to more frequent posts by PSS. Users reported mixed sentiments about increased activity from PSS, with a few in the low community space engagement group mentioning that they would have preferred a larger number of people on the platform so that PSS did not have to post on the newsfeed so often. Although users in this study were not directly asked about experiences of social media-related social anxiety, 24 it is possible that ambiguous social cues, compounded by a reticence to post on the social network, might have interrupted attempts to foster social mastery for some young persons.

With respect to the platform's therapy material and in a theme that blended SDT elements of autonomy and competence, we found that some users experienced a mismatch between their current mental health needs or interests and the therapy pathway or “journey” content suggested to them through the platform algorithm. Though generally accurate in determining appropriate and beneficial content, the platform is unable to use clinical judgment to assign journeys to each user. This discrepancy was often solved through a user's moderator, who was able to personalize the content within a journey or even switch the user to a new journey altogether. Even with personalization, however, we found that not every user was satisfied with the therapeutic content available on Horyzons USA. This does not seem to limit use of therapeutic content, however, as those individuals most vocal about struggling to find modules they liked nevertheless showed moderate to high engagement with the therapy aspect of the platform. Future use of Horyzons USA may benefit from a wider range of activities, including new content areas and activity types that continue to advance and change based on user requests.

We found that users described a variety of factors that promoted a sense of relatedness, especially among users with shared lived experiences, such as the PSS or peers in the social network. Relatedness in general seemed to have no clear connection with usage of therapeutic content on the platform, as individuals expressing similar thematic experiences exhibited a wide range of engagement metrics within the activities completed. Despite occasional dissatisfaction with the moderation approach, users reflected that a stance of unconditional positive regard by their online therapist (e.g., genuine expression of interest, acceptance, and empathy towards the user) encouraged feelings of continuous support. Consistent with recent commentaries, 33 the notion of supplementing or replacing online therapists with an artificially-intelligent tool like a chatbot garnered mixed feedback and most users commented on the importance of having live, human support available. Specifically, they described the presence and support of live therapists facilitated users’ sense of relatedness on Horyzons USA. We also found that the availability of peer support on the platform played a critical role in fostering a sense of community among users who faced “similar struggles,” creating a more engaging social environment through which users felt better able to express themselves openly compared to more traditional forms of social media. These findings are consistent with prior research on digital interventions for FEP suggesting some users may be more inclined to seek certain types of support from peers rather than a trained clinician. 24 Users who expressed the strongest bonds with peers tended towards high community engagement, emphasizing the importance of these unique relationships. While we did not explicitly ask users about their preferences consulting with a peer worker versus an online therapist, the positive reception of online therapists and peer specialists in the current study provides evidence for continued use of two complementary, but distinct, types of support in digital environments.

Finally, a novel feature of the Horyzons USA implementation effort, “Horyzons Hangs,” comprised a theme integrating competence and relatedness among users. On a biweekly basis, Horyzons users met virtually via videoconferencing. These virtual hangouts provided an opportunity for users to build community and practice social skills in a low-stakes environment. Users who shared their personal experiences of Horyzons Hangs tended to engage with the platform at moderate to high levels overall, suggesting potential benefits of forming personal relationships with platform users outside of the platform itself. Considering the novelty of integrating Horyzons Hangs as a feature of MOST platforms, future research should continue to evaluate factors that facilitate or hinder the extent of a user's engagement with synchronous social events conducted remotely as part of a digital intervention. Of note, Horyzons USA was implemented in the context of the global COVID-19 pandemic, which precluded many persons from engaging socially in person for health and safety reasons. Considering the significant impact of the pandemic on social isolation and loneliness among persons with and without mental health conditions, facilitating access to platforms such as Horyzons USA may foster a sense of community, support, and belonging for individuals at increased risk during precarious times.

Limitations

Prior qualitative research examining the implementation of Horyzons in Australia revealed social media anxiety among FEP users. 24 Although Americans who participated in this trial did not express social media anxiety during qualitative interviews, this may reflect a limitation of the interview guide, as it did not specifically address the potential concern of overwhelming peers with mental health content or pressure to post/react to messages displayed on the community page. Future research of Horyzons USA should be deliberate in evaluating the effect of social media-related social anxiety on user engagement with digital interventions. Another limitation of the present study is that our engagement metrics do not account for potential “lurking” in the therapy or community spaces, i.e., passive visits to the platform without active interaction. Given this, it is possible that the engagement quintiles underestimate the extent of participant involvement in Horyzons. We acknowledge several other limitations of the current study, including a short intervention period and a relatively small sample size of users who were recruited from CSC programs and may not be representative of most young persons experiencing FEP.

Conclusions

Although Horyzons has been implemented at a number of CSC clinics in the United States, this is the first study to collect and comprehensively evaluate qualitative interviews about American user's experience using the platform. User experiences with Horyzons USA were variable, as is reflected in qualitative reports of experiences. Notably, Horyzons USA is a “warm environment” that promotes a low barrier of entry through understood shared experiences and moderation of the social and therapeutic platform. In addition, Horyzons Hangs provides a safe and interactive space for users to strengthen social skills in real-time with the support and guidance of peers. Future iterations of the platform will benefit from expanding the number of users involved in the platform and determining which users might benefit most from participation. The authors hope to continue learning from the valuable insights and lived experiences shared by FEP users involved in Horyzons USA.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076231176700 for User experiences of an American-adapted moderated online social media platform for first-episode psychosis: Qualitative analysis by Elena L Pokowitz, Bryan J Stiles, Riya Thomas, Katherine Bullard, Kelsey A Ludwig, John F Gleeson, Mario Alvarez-Jimenez, Diana O Perkins and David L Penn in DIGITAL HEALTH

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the State of North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services for their funding of Horyzons USA and the support from the following NCDHHS staff: Nicole Cole, Kristin Jerger, and Jimmy Treires. We also thank Simon D’Alfonso and Carla McEnery at Orygen Digital, for supporting the American adaption of the MOST platform. In addition, we thank Amanda Teer at UNC for managing the contract with NCDHHS, Dennis Schmidt at UNC for helping us navigate the technical aspects of hosting the Horyzons platform, Jennifer Nieri at UNC who was an invaluable moderator on the platform, and undergraduate research assistants Kate Welch, Yongyi Li, and Caroline Vincent for their training support. We are extremely grateful to the staff and clients at Encompass, Eagle, OASIS and SHORE programs for their critical role in this project, especially PSS Alabama Stone, Bodi Bodenhamer, Dashel Nance, David Boyle, and Sarah Brown, and clinical directors Sylvia Saade, Deborah Redman-Szajnberg, Ashlynn Reed, and Brenda Caldwell.

ELP and BJS certify the accuracy of the results described within this manuscript.

Appendix. Interview guide used by the first author to guide participant questioning.

The Platform

Why did you decide to join Horyzons? What were your goals for using the platform?

- How engaged or motivated were you to use the platform?

- Inactive users: What held you back?

- Active users: What motivated you to login and engage more?

What did you like most about Horyzons? What did you find most helpful?

What did you like least about Horyzons? What was your biggest challenge in Horyzons or using it?

- Do you feel that the overall goals of the Horyzons platform were aligned with your personal goals and that Horyzons provided you with relevant tasks to meet your goals?

- If yes: What made you feel this way?

- If no: What got in the way? What could have been different?

For you personally, what do you think are the most important differences between connecting with others digitally or virtually versus other forms of interactions (e.g., in person, over the phone)?

- Do you use other forms of social media (e.g., facebook, Instagram)?

- If yes: How similar was Horyzons to your social media platforms?

- What else did you notice?

- What was the most different?

- In what way (positive or negative)?

- If no: (i.e., they don't use other social media platforms): What prompted you to join Horyzons?

- Tell me more about that.

What suggestions would you make to improve Horyzons?

Online therapist

- How would you describe your relationship with your online therapist on Horyzons?

- How was this relationship similar to or different from your face-to-face therapist?

- Did your relationship with your online therapist improve/decline/stay the same during your time on Horyzons? In what ways?

What kind of support did you receive from your online therapist?

What kind of support would you liked to have received from your online therapist, but did not?

- How often did you meet with your online therapist?

- In your opinion, what is the ideal number of times or frequency meeting with an online therapist on a platform like Horyzons?

- How did the way you met with your online therapist (i.e., on Zoom, by phone, or a mix) affect your relationship with them, good and/or bad?

- Do you feel like you and your online therapist were compatible, meaning you liked, respected, and trusted each other and felt a common purpose?

- If yes: What did your online therapist do which made you feel this way?

- If no: What got in the way? What could have been different?

- In your opinion, what is valuable about having an online therapist on a program like Horyzons?

- What would you change about the online therapist role?

- Would it be easier for you to engage with a chatbot or a non-human avatar instead of an online therapist? Why or why not?

Peer workers and community space

- What was your relationship like with the peer workers on the community page?

- Was there anything different about the relationship you had with the peer workers versus the online therapists? What contributed to that?

What kind of support did you receive from the peer workers on the community space?

What kind of support would you liked to have received from the peer workers, but did not?

How easy or difficult was it for you to interact with other users on the community space? What made it that way?

Did you feel supported by other users on Horyzons? If not, what kind of support would you like to have received from other users?

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: ELP conducted qualitative interviews. RT and KB transcribed interviews which were supervised by the ELP and BJS. ELP, BJS, RT, and KB conducted the data analysis and manuscript production. The study was supervised by DOP and DLP. All authors contributed to the manuscript and reviewed the final paper.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Horyzons technology is owned by Australian Catholic University (ACU) and was used in this study. In addition, David Penn, the principal investigator of this study, participates in paid activities, which are not part of this study, with the Australian Catholic University (ACU). These activities may include consulting, service on committees or advisory boards, giving speeches, or writing reports.

Ethical approval: The institutional review board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill reviewed and approved all work on this study (UNC IRB #19-1709).

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by the State of North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services for their funding of Horyzons USA (NCDHHS/SAMHSA contract to Diana Perkins (PI) and David L. Penn, Co-I).

Guarantor: DLP

ORCID iDs: Elena L Pokowitz https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1153-2371

Bryan J Stiles https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3939-1366

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Simon GE, Coleman KJ, Yarborough BJH, et al. First presentation with psychotic symptoms in a population-based sample. Psychiatr Serv 2017; 68: 456–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Correll CU, Galling B, Pawar A, et al. Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry 2018; 75: 555–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nossel I, Wall MM, Scodes J, et al. Results of a coordinated specialty care program for early psychosis and predictors of outcomes. Psychiatr Serv 2018; 69: 863–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gafoor R, Nitsch D, McCrone P, et al. Effect of early intervention on 5-year outcome in non-affective psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 2010; 196: 372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Secher RG, Hjorthøj CR, Austin SF, et al. Ten-year follow-up of the OPUS specialized early intervention trial for patients with a first episode of psychosis. Schizophr Bull 2015; 41: 617–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torous J, Bucci S, Bell IH, et al. The growing field of digital psychiatry: current evidence and the future of apps, social media, chatbots, and virtual reality. World Psychiatry 2021; 20: 318–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birchwood M, Fiorillo A. The critical period for early intervention. Psychiatric Rehab Skills 2000; 4: 182–198. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rus-Calafell M, Schneider S. Are we there yet?!-a literature review of recent digital technology advances for the treatment of early psychosis. MHealth 2020; 6: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birnbaum ML, Rizvi AF, Faber K, et al. Digital trajectories to care in first-episode psychosis. Psychiatr Serv 2018; 69: 1259–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buck B, Chander A, Tauscher J, et al. Mhealth for young adults with early psychosis: user preferences and their relationship to attitudes about treatment-seeking. J Technol Behav Sci 2021; 6: 667–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Alcazar-Corcoles MA, González-Blanch C, et al. Online, social media and mobile technologies for psychosis treatment: a systematic review on novel user-led interventions. Schizophr Res 2014; 156: 96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodgekins J, Birchwood M, Christopher R, et al. Investigating trajectories of social recovery in individuals with first-episode psychosis: a latent class growth analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2015; 207: 536–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Gleeson JF, Bendall S, et al. Enhancing social functioning in young people at ultra high risk (UHR) for psychosis: a pilot study of a novel strengths and mindfulness-based online social therapy. Schizophr Res 2018; 202: 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Rice S, D’Alfonso S, et al. A novel multimodal digital service (moderated online social therapy + ) for help-seeking young people experiencing mental ill-health: pilot evaluation within a …. JMIR 2020; 22: e17155. https://www.jmir.org/2020/8/e17155/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rice S, Gleeson J, Davey C, et al. Moderated online social therapy for depression relapse prevention in young people: pilot study of a ‘next generation’ online intervention. Early Interv Psychiatry 2018; 12: 613–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lederman R, Wadley G, Gleeson J, et al. Moderated online social therapy: designing and evaluating technology for mental health. ACM Trans Comput-Hum Interact 2014; 21: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 2000; 55: 68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Bendall S, Lederman R, et al. On the HORYZON: Moderated online social therapy for long-term recovery in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 2013; 143: 143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Koval P, Schmaal L, et al. The Horyzons project: a randomized controlled trial of a novel online social therapy to maintain treatment effects from specialist first-episode psychosis services. World Psychiatry 2021; 20: 233–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Sullivan S, Schmaal L, D’Alfonso S, et al. Characterizing use of a multicomponent digital intervention to predict treatment outcomes in first-episode psychosis: cluster analysis. JMIR Ment Health 2022; 9: e29211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lal S, Gleeson J, Rivard L, et al. Adaptation of a digital health innovation to prevent relapse and support recovery in youth receiving services for first-episode psychosis: results from the Horyzons-Canada phase 1 study. JMIR Form Res 2020; 4: e19887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Doorn M, Popma A, van Amelsvoort T, et al. ENgage YOung people earlY (ENYOY): a mixed-method study design for a digital transdiagnostic clinical – and peer- moderated treatment platform for youth with beginning mental health complaints in the Netherlands. DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-273804/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Ludwig KA, Browne JW, Nagendra A, et al. Horyzons USA: a moderated online social intervention for first episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry 2021; 15: 335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valentine L, McEnery C, O’Sullivan S, et al. Young people’s experience of a long-term social Media-based intervention for first-episode psychosis: qualitative analysis. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e17570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 2019; 11: 589–597. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Bendall S, Koval P, et al. HORYZONS Trial: Protocol for a randomised controlled trial of a moderated online social therapy to maintain treatment effects from first-episode psychosis services. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e024104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel S, Akhtar A, Malins S, et al. The acceptability and usability of digital health interventions for adults with depression, anxiety, and somatoform disorders: Qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e16228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tremain H, McEnery C, Fletcher K, et al. The therapeutic alliance in digital mental health interventions for serious mental illnesses: Narrative review. JMIR Ment Health 2020; 7: e17204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birchwood M, Trower P, Brunet K, et al. Social anxiety and the shame of psychosis: a study in first episode psychosis. Behav Res Ther 2007; 45: 1025–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Addington J, Addington D. Social and cognitive functioning in psychosis. Schizophr Res 2008; 99: 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilboa-Schechtman E, Shachar-Lavie I. More than a face: a unified theoretical perspective on nonverbal social cue processing in social anxiety. Front Hum Neurosci 2013; 7: 904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pham KT, Nabizadeh A, Selek S. Artificial intelligence and chatbots in psychiatry. Psychiatr Q 2022; 93: 249–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076231176700 for User experiences of an American-adapted moderated online social media platform for first-episode psychosis: Qualitative analysis by Elena L Pokowitz, Bryan J Stiles, Riya Thomas, Katherine Bullard, Kelsey A Ludwig, John F Gleeson, Mario Alvarez-Jimenez, Diana O Perkins and David L Penn in DIGITAL HEALTH