Significance

Hybrid lethality prior to gastrulation frequently occurs in various animal hybridization experiments. Genome instability is considered as a widespread hybrid incompatibility phenotype. Hybrids derived from Xenopus tropicalis eggs fertilized by Xenopus laevis sperm suffer specific loss of paternal chromosomes 3L and 4L and die before gastrulation. This study aims to investigate the underlying lethal causes for this hybrid. Using a combination of approaches, we find that P53 is stabilized and activated in the hybrids at late blastula stage. Inhibition of P53 activity rescues the early lethality. Our data indicate that P53 is involved in the hybrid lethality.

Keywords: P53, reproductive isolation, Xenopus, hybrid inviability

Abstract

Hybrid incompatibility as a kind of reproductive isolation contributes to speciation. The nucleocytoplasmic incompatibility between Xenopus tropicalis eggs and Xenopus laevis sperm (te×ls) leads to specific loss of paternal chromosomes 3L and 4L. The hybrids die before gastrulation, of which the lethal causes remain largely unclear. Here, we show that the activation of the tumor suppressor protein P53 at late blastula stage contributes to this early lethality. We find that in stage 9 embryos, P53-binding motif is the most enriched one in the up-regulated Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with high-throughput sequencing (ATAC-seq) peaks between te×ls and wild-type X. tropicalis controls, which correlates with an abrupt stabilization of P53 protein in te×ls hybrids at stage 9. Inhibition of P53 activity via either tp53 knockout or overexpression of a dominant-negative P53 mutant or Murine double minute 2 proto-oncogene (Mdm2), a negative regulator of P53, by mRNA injection can rescue the te×ls early lethality. Our results suggest a causal function of P53 on hybrid lethality prior to gastrulation.

Xenopus laevis, an allotetraploid frog with 36 chromosomes, and Xenopus tropicalis, a true diploid frog with 20 chromosomes, are two evolutionarily distant frog species that diverged from a common ancestor approximately 48 Mya (1). Hybrids derived from crossfertilization of X. laevis eggs with X. tropicalis sperm (le×ts) are viable, whereas the reciprocal hybrids developed from X. tropicalis eggs fertilized by X. laevis sperm (te×ls) die before gastrulation (2–4). Defects in the maintenance of specific centromeres and DNA replication stress underlying the nucleocytoplasmic incompatibility between X. tropicalis eggs and X. laevis sperm lead to the specific loss of majorities of paternal chromosomes 3L and 4L (3, 4). To date, no robust models have been established, which could rescue this early lethality.

Nucleocytoplasmic interactions and zygotic genome activation during early development have intrigued embryologists for more than a century (5). Seminal studies in fish and amphibian embryos with X-ray irradiation have experimentally defined the morphogenetic function of nuclei, now more prevailingly known as zygotic genome activation. Upon selective inactivation of embryonic nuclei before mid-blastula transition (MBT) with optimal doses of X-ray, developmental cessation always takes place at the late blastula, before gastrulation, similar to the late blastula arrest observed in numerous fish and amphibian lethal interspecies hybrids (5–7). Ionizing radiation causes DNA damage and activates cell cycle arrest or cell death. It has been firmly established that P53 is a central regulator of the DNA damage response (8, 9). X. laevis embryos irradiated with γ-ray before MBT fail to undergo gastrulation. Of note, apoptosis is induced in these embryos with no detectable stabilization of P53 protein (10). A subsequent study reveals a developmental timer that regulates apoptosis at the onset of gastrulation in Xenopus embryos, which can be activated by either γ-irradiation or inhibition of DNA replication, transcription, or protein synthesis (11). In contrast, time-lapse videoing and TdT (terminaldeoxynucleotidyl transferase)-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) analyses indicate that le×ts hybrids suffer explosive cell lysis rather than apoptosis at gastrulation (3). Lytic cell death is the characteristic of necrosis, necroptosis, or pyroptosis. The subtypes of cell death occurring in le×ts hybrids remain to be defined.

In this study, we aim at addressing the lethal causes of te×ls hybrids and find that stabilization and activation of P53 contributes to the early lethality of te×ls hybrids with partial involvement of apoptosis.

Results

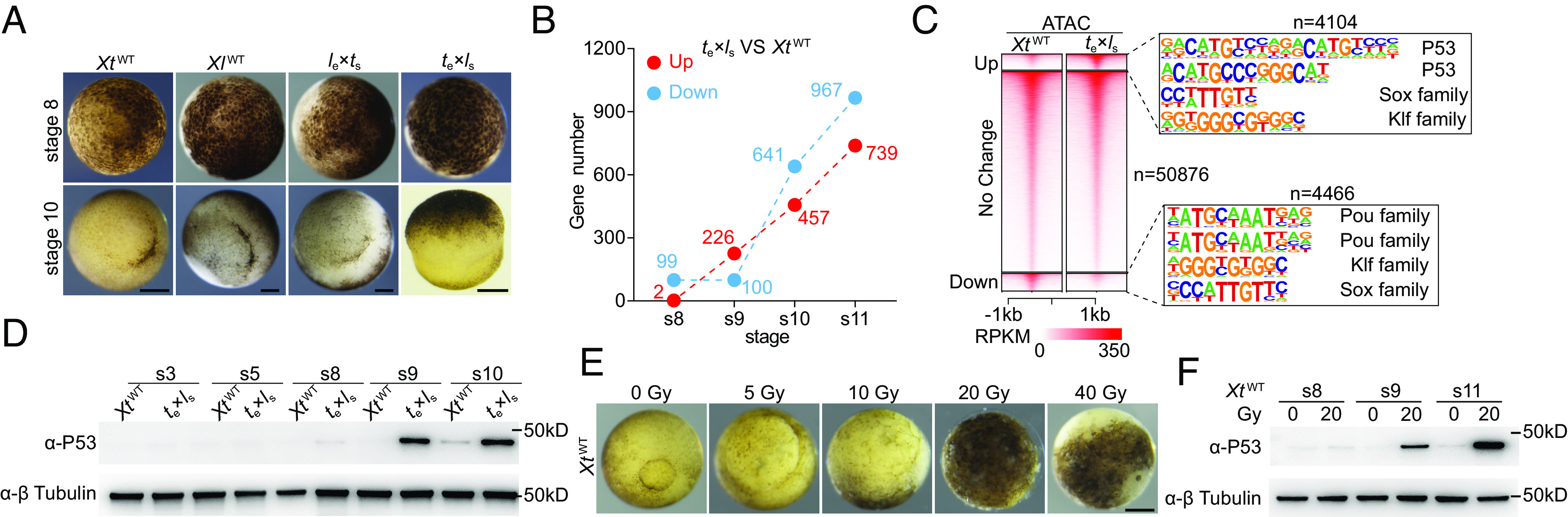

An Abrupt Stabilization of P53 Protein Occurs in te×ls Late Blastulae, as well as Wild-Type Frog Embryos Irradiated with X-Ray or Injected with Linear Plasmid DNA.

To address the early lethality of te×ls hybrids, we conducted a comparative analysis of their early dynamic transcriptional profiles against wild-type controls. High-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analyses of stage 8, 9, 10, and 11 embryos (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) revealed a sharp upregulation of about 200 genes with functional enrichment in epidermis development, stress response, and cell cycle arrest in te×ls hybrids compared to X. tropicalis wild-type ( XtWT) embryos from stage 8 to stage 9, just before and after the major zygotic genome activation, respectively, while the number of down-regulated genes remained relatively stable (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B–F). We reasoned that there might be a corresponding sharp change of chromatin accessibility from stage 8 to stage 9. Given the technical challenge to conduct ATAC-seq analysis with Xenopus embryos before MBT (12), we then chose stage 9 embryos for ATAC-seq analysis. Motif enrichment analysis of the up-regulated ATAC-seq peaks in te×ls hybrids vs. XtWT controls identified that P53-binding motif was the most enriched one (Fig. 1C). Consistent with this, we detected a sharp increase of P53 protein level in stage 9 and 10 te×ls hybrids, which was not observed in either le×ts or XtWT and X. laevis wild-type controls (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). In contrast, given the high levels of maternal full-length tp53 transcripts in both X. laevis (1, 13) and X tropicalis (14), no significant change of full-length tp53 mRNA was detected in all the four groups of embryos from stages 8 to 11 upon RNA-seq analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and C). A discernable increase of Δ99tp53 transcripts was detected between te×ls and XtWT from stage 8 to stage 11 (SI Appendix, Figs. S2D and S8E), which is reminiscent of the morpholino-induced innate immune response, including induction of internal promoter driven Δ99tp53 transcription, in Xenopus (15). X. tropicalis Δ99P53 is equivalent to human Δ133P53 and zebrafish Δ113P53 isoforms, which have been reported to suppress apoptosis by lowering transcriptional activity mediated by full-length P53 (16, 17), suggesting a similar negative feedback response to full-length P53 activation in te×ls hybrids.

Fig. 1.

Specific stabilization of P53 protein in te×ls hybrids and X-ray-irradiated embryos. (A) Representative images of wild-type and hybrid embryos at stage 8 (animal pole view) and stage 10 (vegetal pole view). Independent crossfertilization experiments have been carried out for more than 6 times. (Scale bars, 200 µm). (B) Differential gene expression analysis of the RNA-seq data revealing dynamics of the number of differentially expressed genes between te×ls and XtWT from stage 8 to stage 11. s, stage; VS, versus. (C) ATAC-seq heatmaps and enriched motifs showing P53-binding motif as the most enriched one in the up-regulated peaks between te×ls and XtWT at stage 9. (D) Western blot data showing specific stabilization of P53 protein in te×ls embryos at stages 9 and 10. Identical results were obtained in three independent experiments. s, stage; β-tubulin was used as a loading control. (E) Representative images of embryos irradiated with different doses of X-ray. Identical results were obtained in three independent experiments. (Scale bar, 200 µm). (F) Western blot data showing specific stabilization of P53 protein in X-ray-irradiated embryos at stages 9 and 11. Identical results were obtained in three independent experiments. s, stage; β-tubulin was used as a loading control.

In nonstressed conditions, P53 levels and activity are kept low by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Mdm2-mediated degradation. In response to various stresses, including DNA damage, P53 activation occurs largely through protein stabilization (18). We assessed P53 protein levels in X. tropicalis embryos either irradiated with X-ray, or treated with DNA replication inhibitor aphidicolin, transcription inhibitors α-amanitin and triptolide, or protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (3, 11). All the treatments were carried out before MBT, which led to developmental arrest at the onset of gastrulation (3, 11 and Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S2E). Robust increase of P53 protein levels was only detected in X-ray-irradiated stage 9 and stage 11 embryos, while weak signals were observed with the two transcription inhibitors, α-amanitin and triptolide (Fig. 1F and SI Appendix, Fig. S2F). X-ray irradiation also induced P53 stabilization in X. laevis embryos (SI Appendix, Fig. S2G). Although we used X-ray instead of γ-ray, the previous failure in detecting P53 stabilization in γ-irradiated X. laevis embryos is likely due to the antibody used (10). Thus, with respect to the effect on P53 stabilization, te×ls hybrid incompatibility resembles X-ray irradiation.

It has been reported that relatively high doses of exogenous DNA have an unspecific toxicity to Xenopus embryos and lead to gastrulation defects (19–21). Linearized plasmid DNA injected into Xenopus fertilized eggs can form head-to-tail tandem repeats and become degraded after gastrulation (20, 21). Small pseudonuclei can be formed around the injected bacteriophage λ DNA (linear) in both Xenopus unfertilized eggs and embryos (22, 23). Although we did not analyze the formation of tandem repeats or pseudonuclei after linear plasmid DNA injection, we noticed that fertilized eggs of our tp53-null X. tropicalis line (24) could withstand four times more exogenous plasmid DNA than their wild-type counterparts. We reasoned that P53 pathway might be activated in the exogenous DNA-induced gastrulation defect model. Indeed, western blot analysis revealed a dose-dependent P53 protein stabilization in XtWT embryos in response to injected linear pBluescript II SK+ plasmid, which could occur as early as stage 4 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 H and I). These embryos partially resemble the te×ls hybrids at both morphological and molecular levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 J–M). Together, the te×ls hybrid incompatibility, X-ray irradiation, and exogenous plasmid DNA can all lead to gastrulation defects and P53 stabilization in Xenopus.

Activation of P53 Pathway Contributes to te×ls Early Lethality.

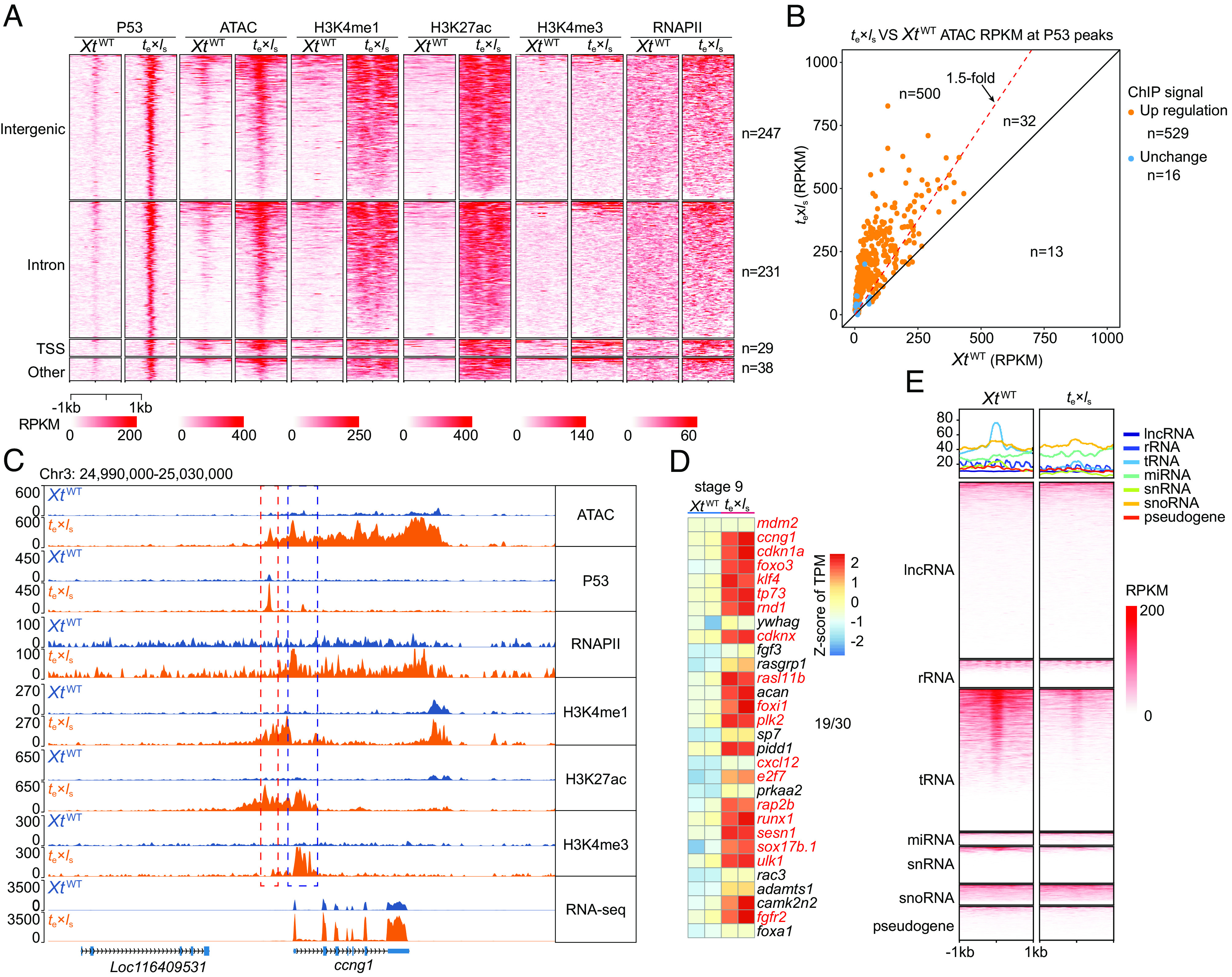

To assess the functionality of stabilized P53 in te×ls hybrids, we carried out a P53 chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis. Consistently, we observed a sharp increase of P53 occupancy throughout the genome at stage 9 in te×ls compared to XtWT, which in turn matched with the up-regulated ATAC-seq peaks (Fig. 2 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A–C). H3K4me1/H3K27ac and H3K27ac/H3K4me3 are active enhancer and promoter histone marks, respectively. The up-regulated P53 ChIP-seq signals correlate with increased RNA Pol II, H3K4me1, H3K27ac, and H3K4me3 ChIP-seq signals (Fig. 2A), as well as the up-regulated RNA-seq signals, which is well illustrated via zooming in individual P53 target genes, such as maternal ccng1 and cdkn1a (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S3D) and paternal ccng1.l, ccng1.s, and foxi1.s (SI Appendix, Fig. S3E). Based on the up-regulated ATAC-seq signals, a similar correlation also exists (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C), indicating the reliability of our multiomics data. Among the differentially expressed genes between te×ls and XtWT, at stage 9, 19 of the top 30 up-regulated hub genes, based on the node degrees of protein–protein interaction (PPI) network analysis, were covered by P53 ChIP-seq signals, including mdm2, ccng1, and cdkn1a (Fig. 2D). At stages 10 and 11, significant numbers of both top up-regulated and top down-regulated hub genes were covered by P53 ChIP-seq signals, relating to cell cycle arrest, perturbation of signaling pathways involved in germ layer specification, and apoptosis (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

Fig. 2.

Activation of P53 signaling pathway in stage 9 te×ls embryos. (A) Heatmaps showing correlation of up-regulated P53 occupancy with increased ATAC-seq signals, as well as increased H3K4me1, H3K27ac, H3K4me3, and RNA Pol II ChIP-seq signals in stage 9 te×ls embryos versus XtWT controls. Heatmaps are centered at P53 peak summits. Regions are ranked by the average P53 signal within 1 kb of the peak. (B) A scatter plot showing ATAC-seq signal intensity at each P53 ChIP-seq peaks in XtWT and te×ls embryos at stage 9. (C) Representative genome tracks showing transcriptional activation of P53 target gene ccng1 (the X. tropicalis version) in te×ls embryos at stage 9. (D) Heatmap of the top 30 hub genes identified in the PPI networks of up-regulated genes between te×ls and XtWT. Genes in red were covered by increased P53 ChIP-seq signals in stage 9 te×ls embryos. (E) Heatmaps showing the distribution of ATAC-seq signals in different noncoding RNA gene loci and pseudogene. Heatmaps are centered at different inputs. Regions are ranked by the ATAC-seq signal within 1 kb of input.

P53 is known to regulate various metabolic pathways and can act as a metabolic sensor (25, 26). Our functional enrichment analysis of differential expression genes between te×ls and XtWT in the context of metabolism attributed to P53 and FoxO pathways (SI Appendix, Fig. S1F). Further analysis of the differentially expressed genes in each signaling pathway suggested their step-wise and fine-tuned regulation of cell cycle, apoptosis, DNA repair, and metabolism during stages 8 to 11 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Inspection of the ATAC-seq signal distribution in the noncoding gene loci revealed a sharp decrease of chromatin accessibility in genome-wide tRNA loci in te×ls vs. XtWT (Fig. 2E).

Together, the activity of activated P53 in te×ls hybrid inviability is reminiscent of embryonic lethality caused by P53 overexpression in X. laevis embryos (27) or Mdm2 knockout in mice, which can be rescued by deletion of P53 (28, 29), suggesting a causal role of P53 to the death of the te×ls hybrids.

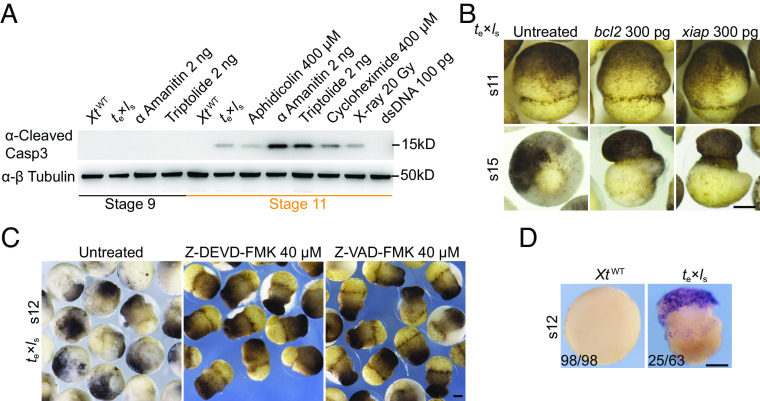

Apoptosis Is Partially Involved in te×ls Lethality.

To validate our multiomics data on P53-mediated apoptosis, we modulated the apoptotic pathway in te×ls hybrids. Despite the robust stabilization of P53 in te×ls hybrids, activated Caspase-3 was relatively low compared to other treatments (Fig. 3A). Blocking apoptosis with either the pan-Caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK and the Caspase-3 inhibitor Z-DEVD-FMK, or antiapoptotic Bcl2 and Xiap (inhibitor of apoptosis), partially rescued te×ls lethality (Fig. 3 B and C), reminiscent of the partial rescue effects of Bcl2 on the cell death induced by P53 (27), γ-ray, α-amanitin, or cycloheximide in X. laevis embryos (11). Consistent with the previous study (3), TUNEL staining signals can hardly be detected in te×ls hybrids at stage 10.5. However, clear TUNEL staining signals were detected in te×ls hybrids when control siblings reached stage 12 (Fig. 3D). Together, these data suggest that apoptosis plays a partial role in te×ls lethality, and additional types of cell death underlying te×ls inviability remain to be defined.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of apoptosis pathway only partially rescued the death of te×ls hybrids. (A) Western blot data showing the levels of cleaved Caspase 3 in te×ls hybrids, as well as in XtWT embryos subjected to various treatments as indicated. Identical results were obtained in three independent experiments. β-tubulin was used as a loading control. (B) Representative images showing the partial rescue of the death of te×ls hybrids by Bcl2 or Xiap overexpression. Identical results were obtained in three independent experiments. (Scale bar, 200 µm). s, stage. (C) Representative images showing the partial rescue of the death of te×ls hybrids upon Z-DEVD-FMK (Caspase 3 inhibitor) or Z-VAD-FMK (a pan-Caspase inhibitor) treatment. Identical results were obtained in three independent experiments. s, stage; (Scale bar, 200 µm). (D) Representative TUNEL staining images showing positive signals in te×ls hybrids when control siblings reached stage 12. s, stage; (Scale bar, 200 µm).

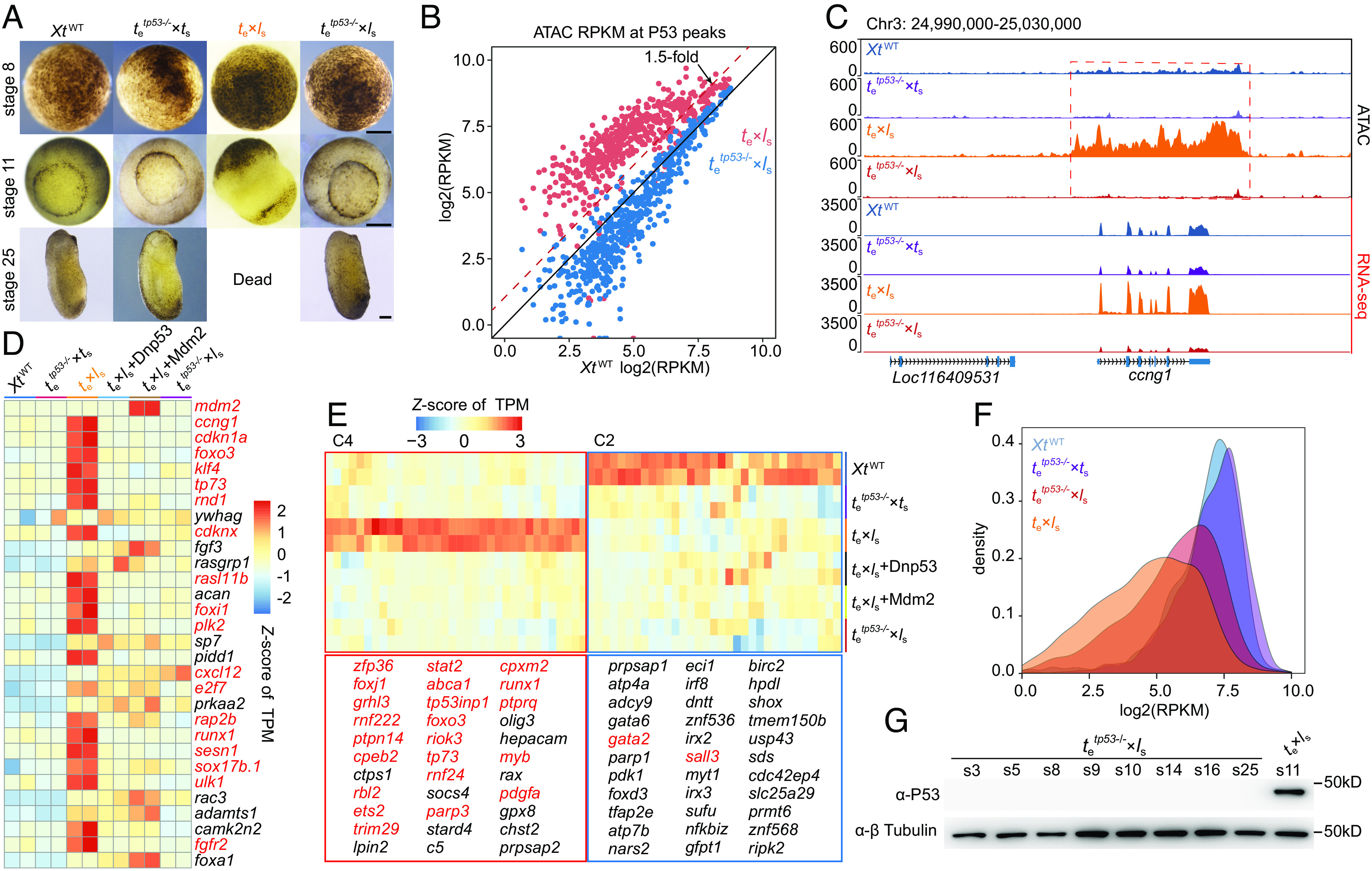

Inhibition of P53 Activity Rescues te×ls Hybrid Early Lethality.

Utilizing a tp53 knockout line established in our laboratory (24), which disrupted both the full-length P53 and the Δ99P53 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A), we found that hybrids produced from crossfertilization of X. tropicalis tp53−/− eggs with wild-type X. laevis sperm (referred to as tetp53−/−×ls) exhibited a successful progression through gastrulation and continued to survive until stage 37, indicating a clear rescue that significantly postponed the lethal stage (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S6 B and C). Overexpression of a dominant-negative P53 (Dnp53) mutant or Mdm2 by mRNA injection can also rescue the early lethality of te×ls hybrids to stage 25 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 C and F). Similarly, disruption of P53 rescued 5 Gy of X-ray-induced gastrulation lethality in X. tropicalis (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 D, E, and G ).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of P53 activity leading to partial rescue of te×ls lethality. (A) Representative images showing the delay of te×ls lethality in tetp53−/−×ls. Identical results were obtained in 5 independent experiments. (Scale bars, 200 µm). (B) A scatter plot showing ATAC-seq signals at P53 ChIP-seq peaks plotted within te×ls and XtWT or tetp53−/−×ls and XtWT. (C) Representative genome tracks showing the rescuing effect on ccng1 (the X. tropicalis version) transcription in stage 9 tetp53−/−×ls embryos. (D) Heatmap showing rescue of the expression of the top 30 hub genes identified in the PPI networks of up-regulated genes between stage 9 te×ls and XtWT. Genes in red were covered by P53 ChIP-seq signals detected in stage 9 te×ls embryos. (E) Heatmaps of Cluster 2 (hardly rescuable) and Cluster 4 (P53 activated) metabolism genes. Genes in red were covered by P53 ChIP-seq signals. (F) Density plot showing partial rescue of ATAC-seq signals in tRNA gene loci upon tp53 knockout. (G) Western blot data showing no P53 expression in tetp53−/−×ls embryos. s, stage; β-tubulin was used as a loading control. Identical results were obtained in three independent experiments.

ATAC-seq and RNA-seq analyses indicate that P53 activation–related chromatin accessibility changes and up-/down-regulated expression of hub genes seen in te×ls hybrids are largely corrected in tetp53−/−×ls hybrids (Fig. 4 B–D and SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S7 A–C). For the previously reported 165 differentially expressed metabolism transcripts (3) between te×ls and XtWT, we could categorize them into 5 classes in our rescue model. Except for the expression of 33 genes in Class 2, which can hardly be rescued in tetp53−/−×ls hybrids, the expression of the rest ones, especially of Class 4 genes, can be rescued to almost normal levels in tetp53−/−×ls hybrids, suggesting that alteration of these transcripts in te×ls is the consequence of activated P53, rather than the cause of hybrid inviability (Fig. 4E and SI Appendix, Fig. S7C).

It has been reported that P53 activation can repress RNA polymerase III-mediated transcription by targeting TBP and inhibiting promoter occupancy by TFIIIB (30). Based on the ATAC-data, the reduction of chromatin accessibility in genome-wide tRNA loci seen in te×ls was also partially rescued in tetp53−/−×ls, indicating the dependence of this reduction on activated P53 (Fig. 4F). X. laevis tp53l locus located on chromosome 3L is lost in the te×ls hybrids, while the tp53s locus is retained. Western blot analysis indicates that no full-length P53 (potentially from the X. laevis tp53s locus) is expressed in tetp53−/−×ls, ruling out P53 contribution to the death of tetp53−/−×ls at tailbud stage of development (Fig. 4G).

The tetp53−/−×ls and te×ls hybrids provide a valuable reciprocal reference for comparative analyses of the paternal genome-related data. Focusing solely on the paternal genome, we observed that the most enriched motifs of up-/down-regulated ATAC-seq signals between te×ls and tetp53−/−×ls illustrated just a reverse picture of those seen in the comparison between XtWT and te×ls based on maternal genome alone (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A in comparison with Fig. 1C). Similarly, analyzing the paternal genome alone revealed a reversed picture of the changes in chromatin accessibility in genome-wide tRNA loci between the te×ls /tetp53−/−×ls pair and the XtWT/te×ls pair (SI Appendix, Fig. S8B in comparison with Fig. 2E). Examination of paternal-only differential expression genes between te×ls and tetp53−/−×ls demonstrated the rescue of the most prominently activated P53 pathway and down-regulated developmental signaling pathways in stage 9 te×ls hybrids (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 C and D). Integrative analysis of ATAC-seq, H3K4me3 ChIP-seq, and RNA-seq data on individual paternal loci revealed the rescue of the paternal response to activated P53 pathway in stage 9 te×ls hybrids (SI Appendix, Fig. S8E).

Specific Loss of Paternal Chromosomes 3L and 4L Persists in tetp53−/−×ls Hybrids.

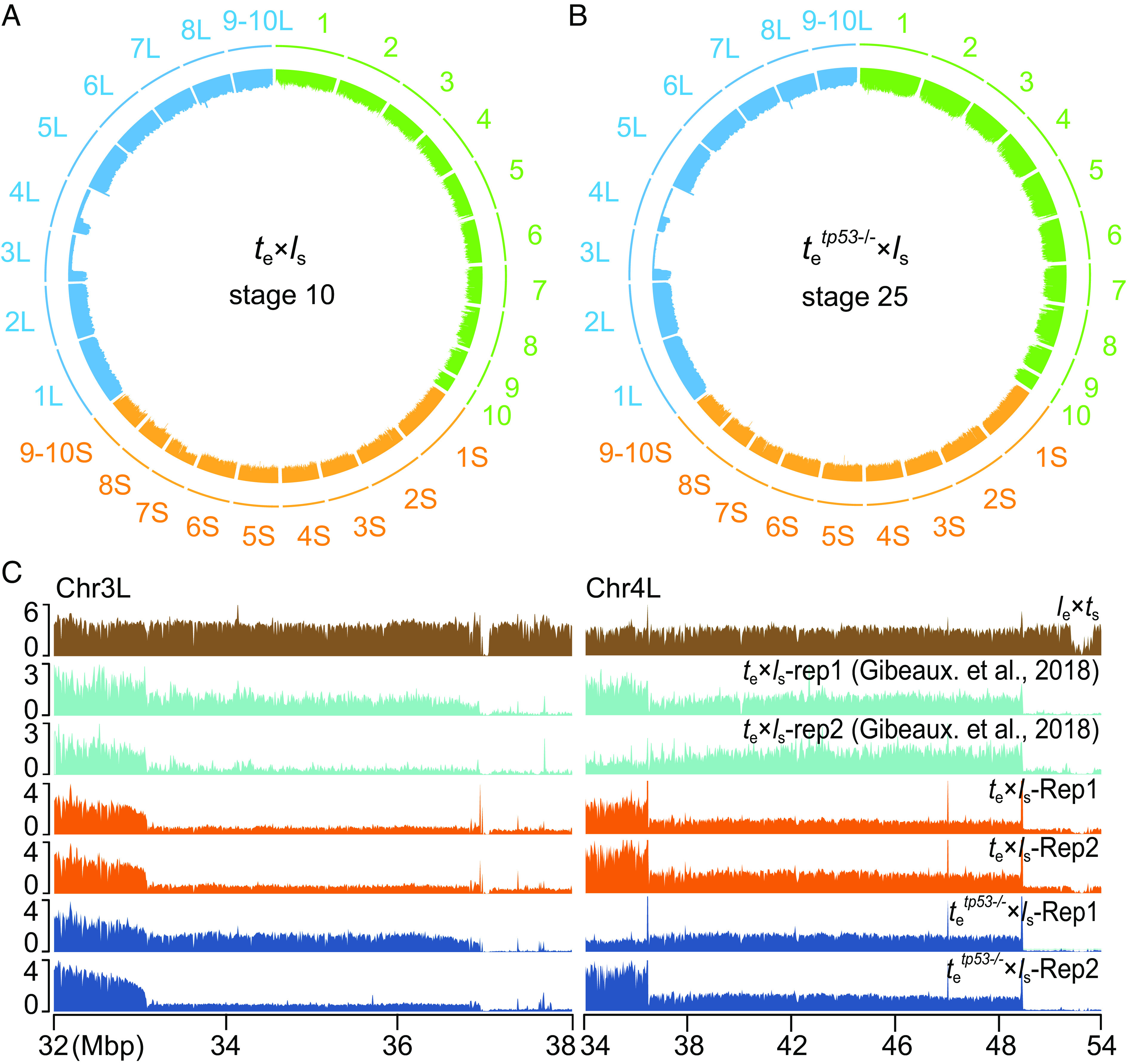

It was shown that cold shock–induced triploid hybrid tte×ls can survive longer, but the X. laevis DNA was eliminated by the tadpole stage (3). Our whole-genome sequencing (WGS-Seq) data revealed that the majority of the paternal chromosomes 3L and 4L were similarly lost in tetp53−/−×ls hybrids and this hybrid genotype was maintained in tailbud stage tetp53−/−×ls hybrids (Fig. 5 A–C). The death of tetp53−/−×ls at late tailbud stage of development is likely due to the specific loss of chromosomes 3L and 4L, which remains to be further investigated.

Fig. 5.

Stable genotype in tetp53−/−×ls hybrids. (A) Circle plot of whole-genome sequencing data for stage 10 te×ls hybrids aligned and normalized to the genomes of X. tropicalis (green) and X. laevis (orange and blue). Underrepresented genome regions (dents) represent deletion of chromosomes 3L and 4L. (B) Circle plot of whole-genome sequencing data for stage 25 tetp53−/−×ls hybrids aligned and normalized to the genomes of X. tropicalis (green) and X. laevis (orange and blue). Underrepresented genome regions (dents) represent deletion of chromosomes 3L and 4L. (C) Expanded view of chromosome 3L and 4L breakpoints with the lost regions indicated in two biological replicates. Chr, chromosome; Rep, replicate.

Discussion

In fish and amphibians, many interspecific lethal hybrids arrest their embryonic development prior to gastrulation, which resembles the phenotype induced by ionizing radiation applied before MBT (5–7). In this study, we find that P53 protein is indeed stabilized in both te×ls hybrids and X-ray-irradiated wild-type Xenopus embryos, which plays a pivotal role in controlling the fate of these embryos around gastrulation. As a third model, linear plasmid DNA can also induce gastrulation defects and P53 stabilization in X. tropicalis embryos in a dose-dependent manner.

P53 is known to regulate various forms of cell death, including necrosis and necroptosis (31–33). Our study shows that apoptosis only partially contributes to the death of te×ls hybrids. We were unable to identify significant signals for other types of cell death from our multiomics data including the P53 ChIP-seq data. The transcription-independent cytoplasmic function of P53 is important for regulating cell death. For example, in mammalian cells, P53 can accumulate in the mitochondrial matrix in response to oxidative stress, physically interact with cyclophilin D, and trigger mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening and necrosis (31). The other types of P53-regulated cell death involved in the lethality of te×ls hybrids, as well as X-ray-irradiated and linear plasmid DNA-injected embryos, remain to be identified.

In sum, chromosome loss has also been detected in lethal hybrids of fish (34, 35) and Drosophila (36) and genome instability might be a widespread hybrid incompatibility phenotype (37). It has been proposed that quality control of germ cells is the ancestrally conserved function of the P53 family members (38, 39). Here, we find that P53 is involved in Xenopus te×ls hybrid lethality.

Materials and Methods

Frogs and Animal Experimentation.

All animal experiments in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Southern University of Science and Technology. Adult X. tropicalis and X. laevis frogs were purchased from NASCO. All X. tropicalis tadpoles, froglets, and frogs were housed in a room with a constant temperature at 25 °C and the constant room temperature for X. laevis was 18 °C. The frog housing rooms follow a 12-h light-dark cycle. The X. tropicalis tp53−/− line was established using the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted disruption strategy in our laboratory (24). Embryos were obtained from mature X. tropicalis (8 mo to 2 y) and X. laevis (approximately 2 y old) frogs via either hormone-induced mating or artificial fertilization/crossfertilization. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Hormone-Induced Mating, Artificial In Vitro Fertilization, and Crossfertilization.

Mature X. laevis males and females were primed with 300 U and 500 U of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), respectively. Mature X. tropicalis males and females were initially primed with 20 U of hCG 1 d in advance, followed by injection of a full dose (150 U of hCG).

For hormone-induced mating, each pair of frogs (one male and one female of the same species) was housed in individual tanks containing 0.1× Mordified Barth's Solution (MBS) 1× MBS: 88 mM NaCl, 1.0 mM KCl, 0.41 mM CaCl2, 0.33 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.82 mM MgSO4, 2.4 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). Once sufficient quantities of eggs were spawned and fertilized, they were promptly collected.

For artificial in vitro fertilization and crossfertilization, the frogs were primed with hCG as mentioned above. Males and females were kept separately. When females started spawning, males were killed by injecting 200 to 300 µL 4% tricaine (MS222) and the testes were dissected. X. laevis testes can be stored in 1× MBS at 4 °C for 1 to 2 wk, while X. tropicalis testes should be used immediately as sperm viability is severely reduced upon 4 °C storage. The testes were minced in a small Petri dish using a sharp blade, suspended in 1× MBS (500 µL for two minced X. tropicalis testes and 1 ml for one minced X. laevis testis), and kept on ice. To generate embryos with X. tropicalis eggs, approximately 1,000 eggs were squeezed onto a Petri dish, mixed well with 500 µL of desired (either X. tropicalis or X. laevis) sperm suspension, incubated for 2 min, then added with 4.5 mL double distilled water (ddH2O), swirled, and further incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The fertilized eggs were transferred to a beaker and dejellied with 3% L-cysteine solution (pH 8.0) by swirling for 3 min and washing five times with 0.1× MBS. They were then transferred to Petri dishes coated with 1% agarose and incubated at 25 °C. To generate embryos with X. laevis eggs, about 500 eggs were squeezed to a Petri dish, mixed well with 2 mL of desired sperm suspension (200 µL of either X. laevis or X. tropicalis sperm suspension diluted with 1.8 mL of ddH2O), and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The fertilized eggs were dejellied with 2% L-cysteine solution (pH 8.0) for 3 to 5 min, washed five times with 0.1× MBS, transferred to a new Petri dish, and incubated at 18 °C with 0.1× MBS.

Plasmid Construction and Microinjection.

The open-reading frames of four X. tropicalis genes, tp53, mdm2, bcl2, and xiap, were amplified by RT-PCR using total RNA extracted from stage 11 X. tropicalis embryos and cloned into the pCS2+ vector. To design an X. tropicalis Dnp53, we deleted amino acids 10 to 282 including the whole DNA-binding domain (40). To clone this fragment, the segment coding for the first 9 amino acids was prepared by annealing two synthesized primers and the fragment coding for amino acids 283 to 362 was obtained by PCR amplification. The two fragments were assembled into the linearized pCS2+ vector using a one-step clone method (pEASY®-Basic Seamless Cloning and Assembly Kit, CU201-02, TransGen Biotech). All constructs were verified by Sanger DNA sequencing. Linear double-stranded DNA used for microinjection was generated by PCR amplification with pBluescript II SK+ plasmid as a template and purified by gel electrophoresis using a Gel Extraction kit (28706, Qiagen). Sequences of all primers are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1.

For mRNA injection, all constructs were linearized with NotI and transcribed with the mMESSAGE mMACHINE SP6 Kit (AM1340, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The synthesized mRNAs were purified with the RNeasy Mini Kit (74106, Qiagen), dissolved in nuclease-free water, quantified by NanoPhotometer (IMPLEN), and stored at −80 °C. Two nanoliters of each mRNA (300 pg per egg) was injected into fertilized eggs at 1-cell stage at the animal pole using a pneumatic Pico Pump PV830 (WPI, Sarasota, Florida). The injected embryos were collected or imaged at desired stages using a stereo microscope (SMZ18, Nikon).

Chemical Treatments.

All chemicals were purchased from MedChemExpress unless otherwise stated. The experimental procedure for chemical treatment of embryos is as described previously (3, 11). The 24-well cell culture plates were precoated with 1% agarose, and each treatment and control group used 30 embryos. Stage 6 embryos were transferred to the coated plates and incubated in 1 mL of 0.1× MBS solution containing the appropriate concentration of chemicals at 25 °C. The stock solutions of aphidicolin (ab142400, Abcam), α-amanitin (HY-19610), triptolide (HY-32735), cycloheximide (46401, Merck), Z-DEVD-FMK (HY-12466), and Z-VAD-FMK (HY-16658B) were prepared with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), which allow for at least 1:1,000 dilution in use. Corresponding volumes of DMSO were added to the controls. α-amanitin and triptolide were injected into each fertilized egg at the 1-cell stage at the dose of 2 ng per egg.

X-Ray Irradiation.

For each X-ray irradiation group, 30 embryos at stage 6 were used and irradiated using the RS2000 X-ray irradiator (RS2000pro-225, Rad Source). For doses below 5 Gy, embryos were placed on the first tier of the shelf and the RS2000 irradiator was set to operate at 10 mA and 225 kV. For doses above 5 Gy, embryos were placed on the sixth tier of the shelf and the X-ray machine was configured to operate at 17.7 mA and 225 kV.

Whole-Mount TUNEL Staining.

Whole-mount TUNEL staining was performed as described previously (11). After MEMFA: (MOPS (3-morpholinopropanesulfoinc Acid)/EGTA (ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid)/Magnesium Sulfate/Formaldehyde fixative: 100 mM Mops, pH 7.4, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgSO4, and 4% formaldehyde) fixation, embryos were dehydrated and stored in Dent's solution (20% DMSO in methanol) overnight at −20 °C. The embryos were then rehydrated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and permeabilized in PTw (0.2% Tween 20 in 1× PBS). For the end labeling reaction, the embryos were first bleached with a mixed solution containing 2% H202 and 5% formamide and 0.5× SSC (saline-sodium citrate: 7.5 mM NaCl, 7.5 mM C6H5Na3O7, pH 7.0) for 2 h under light, washed three times with PBS, incubated for 1 h at room temperature in 1× TdT buffer, followed by overnight incubation in a TdT buffer containing 150 U/mL TdT enzyme (10533065, Invitrogen) and 1 pmol/l digoxigenin-11-dUTP (11570013910, Roche). The reaction was terminated in 1 mM EDTA-containing PBS at 65 °C and washed three times at room temperature with 1× MAB (100 mM maleic acid, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5). For antibody incubation, the embryos were blocked in a 1× MAB solution containing 2% BMB for 1 h, incubated in a 1×MAB solution containing the antidigoxigenin AP antibody (diluted 1:5,000) and 2% BMB at room temperature for 4 h, and then washed with large volume (50 mL) of 1× MAB overnight at 4 °C. For chromogenic reaction, the embryos were incubated in APB (Alkaline Phosphatase Detection Buffer: 100 mM Tris, pH 8.45, 50 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) for 10 min and stained with APB buffer containing nitro blue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate for 2 h. Afterward, the embryos were washed with H2O, transferred to 1× MEM (0.1M MOPS, 0.2mM EGTA, 1mM MgSO4, pH 7.4), and imaged using a stereo microscope (SMZ18, Nikon).

Western Blot Analysis.

Western blot was performed as described previously (41). Ten embryos at indicated stages were collected and homogenized in immunoprecipitation assay buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Merck). Anti-P53 (1:3,000, ab16465, Abcam), anticleaved Caspase-3 (1:3,000, 9661S, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-HA (1:3,000, 3724S, Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-β-tubulin (1:3,000, HC101, TransGen Biotech) were used as the primary antibodies. β-tubulin was used as the loading control. Goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:10,000, HS201-01, TransGen Biotech) was used as the secondary antibody. The signal was detected using a chemiluminescent western blot detection kit (Millipore) and imaged using the ChemiDox XRS Bio-Rad Imager.

RNA-Seq Library Preparation.

Ten embryos at the desired developmental stages were collected for RNA-seq library preparation. Total RNA was extracted using TransZol Up lysis reagent (ET111-01, TransGen Biotech). RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the VAHTS® Universal V6 RNA-seq Library Prep for Illumina Kit (NR604, Vazyme) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of the libraries was assessed using an Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent). Sequencing of the libraries was performed on the NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina).

ChIP-Seq Library Preparation.

ChIP-seq library preparation was performed as described previously (41). Briefly, 300 to 1,000 embryos at the desired stages were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 30 min. Fixation was then stopped by a 10-min incubation in 0.125 M of glycine dissolved in 0.1× MBS, followed by three washes with 0.1× MBS. The fixed embryos were frozen at −80 °C in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes with 200 embryos per tube. Chromatin was sheared to an average size of 150 bp using a sonicator (Bioruptor Pico; Diagenode). Sonicated chromatin fragments were immunoprecipitated with 3 μg anti-P53 (ab16465, Abcam), anti-Rpb1 (sc-56767, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-H3K27ac (39685, Active Motif), anti-H3K4me1 (39635, Active Motif), and anti-H3K4me3 (61379, Active Motif). Chromatin-bound antibodies were recovered with 30 μl Protein A/G Magnetic Beads (16 to 663; Millipore). Immunoprecipitated DNA and input DNA were recovered using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (28006, QIAGEN). The final libraries were prepared using the VAHTS Universal DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina V3 (ND607, Vazyme). Amplified libraries were sequenced on the NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina).

WGS-Seq Library Preparation.

Ten embryos from each experimental group were used for WGS-seq library construction. Genomic DNA was extracted using the EasyPure Genomic DNA Kit (EE101, TransGen Biotech) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The genome was fragmented using a sonicator (Bioruptor Pico; Diagenode). The fragmented DNA was purified and concentrated with a MinElute PCR Purification Kit (28006, QIAGEN). WGS-seq libraries were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the VAHTS® Universal DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina V3 (ND607, Vazyme). Amplified WGS libraries were subsequently sequenced on both the NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina) and DNBSEQ-T7 (MGI Tech Co) platform.

ATAC-Seq Library Preparation and Analysis.

ATAC-seq was performed with a significantly modified protocol. To analyze the obtained data, the genomes of X. tropicalis v10.0 and X. laevis v10.1 were merged into a fusion genome and an index was generated. Raw fastq reads were trimmed by fastp and aligned to the fusion genome using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) (42). Low mapping quality (MAPQ < 20) and PCR-duplicated reads were removed by (Sequence Alignment/Map format (SAMtools) and sambamba, respectively. The filtered Binary Alignment Map (BAM) files were split according to the genomes of X. tropicalis and X. laevis, thus generating the X. tropicalis and X. laevis bam files, respectively. The sequencing coverage of X. tropicalis and X. laevis was calculated using bamCoverage (43) with options “--binSize 10 --normalizeUsing RPKM –ignoreDuplicates.” Peaks were identified using MACS2 with the options “macs2 callpeak -f BAM -g 1.4e9/2.6e9 -B -q 0.1 --nomodel --shift 70 --extsize 140 --keep-dup all” (44). High-confidence accessible regions were determined by merging the two ATAC-seq replicates and calling peaks from the merged data. Only peaks that had more than 50% overlap with peaks called from both biological replicates individually were defined as accessible regions (45, 46). Peak merging and identification of differential peaks were performed using DiffBind (False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05, absolute fold change > 1.5) (47). Accessible regions with significantly higher or lower ATAC-seq signals between the control and the experimental groups were further used for motif enrichment. The Homer script “findMotifsGenome.pl” was used to enrich known motifs and predict new motifs for specified genomic regions (48).

RNA-Seq Analysis.

The low-quality and adapter sequences of raw fastq reads were removed by fastp with the option “-f 15 -F 15 -c” (49). The clean reads were mapped to the combined X. tropicalis v10.0 and X. laevis v10.1 reference genomes downloaded from Xenbase (http://www.xenbase.org/, Research Resource Identifiers (RRID): SCR_003280) using HISAT2 (50). Low MAPQ reads (MAPQ < 20) and PCR duplicates were filtered by SAMtools and sambamba, respectively (51, 52). The genes in X. tropicalis and X. laevis were counted separately using featureCounts (53). The XB_GENE_NAME of X. tropicalis and X. laevis was then converted to XB_GENEPAGE_NAME according to the gene ID conversion file provided by Xenbase. The count values of genes with the same NAME were combined. Genes that could be converted to XB_GENEPAGE_NAME and were contained in X. laevis but not in X. tropicalis will be removed (3). Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (54), and genes with an adjusted P-value <0.05 and absolute log2(fold change) > 1 were considered differentially expressed. The protein interaction network of related differentially expressed genes was analyzed using the STRING database V11.5 (55). For metabolism gene analysis, we obtained a list of metabolism genes from publicly available sources PANTHER version 16 (56) and filtered the list using X. tropicalis and “metabolic process” as the keywords in AmiGO (57). Gene Ontology (GO) (58) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (59) enrichment analyses were performed with the R package clusterProfiler version 4.2.2 (60). Adjusted P values were used to screen for plausible biological process terms and KEGG pathways. The dot and bar plots for enrichment analysis were drawn by the python package Matplotlib version 3.5.1 (61). Path plots for KEGG were redrawn based on the R package pathview version 1.34.0 (62).

ChIP-Seq Analysis.

Raw data trimming and mapping analysis was carried out as previously described (41). To assess the reproducibility of replicates, the read coverage of genomic regions was calculated for filtered BAM files using the deeptools v3.5 multiBamSummary bins command with a bin size of 10 kb. The coverage was calculated by bamCoverage with options “--binSize 10 --normalizeUsing RPKM –ignoreDuplicates.” The replicate BAM files were merged for further peak calling analysis using MACS v.2.0 (63) with options “macs2 callpeak -f BAMPE -g 1.4e9 -q 0.05.” High-confidence determination and differential peak identification were handled as described for ATAC-seq. Peaks were annotated using the Homer script “annotatePeaks.pl” with default parameters.

WGS-Seq Analysis.

The low-quality and adapter sequences of raw fastq reads were removed by fastp. The resulting clean reads were then mapped to the combined X. tropicalis v10.0 and X. laevis v10.1 reference genome using BWA. Low MAPQ reads were removed by samtools (MAPQ < 20). The comparison data of X. tropicalis and X. laevis were split and stored. BAM files were converted to bigwig files using bamCoverage (bin size = 10 and 1,000,000). The bigwig files with a bin size of 1,000,000 were converted to bedgraph files using bigWigToBedGraph and utilized to generate circle plots. The circos graph was created using the R package “circlize” (version 0.4.15) (64).

Heatmaps and Plots.

Heatmap plots based on RNA-seq data were generated using R 3.6 and the pheatmap package (https://github.com/raivokolde/pheatmap). Heatmaps for scores associated with genomic regions based on ATAC-seq and ChIP-seq data were generated using plotHeatmap. Scatter plots, bar plots, and density plots were created using the R package ggplot2 (65). Correlation matrix was generated using multiBamSummary and plotted using plotCorrelation with default parameter.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Chen laboratory for support and discussions. We thank Xi Chen, Huanhuan Cui, and Weizheng Liang for ATAC-seq assistance. We are grateful to Jiarong Wu for technical supports and Pingyuan Zou for frog husbandry. We acknowledge the Center for Computational Science and Engineering of SUSTech for the support on computational resource and acknowledge the SUSTech Core Research Facilities for technical support. This work was supported by Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20210324120205015 to Y.C.), Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Cell Microenvironment and Disease Research (2017B030301018 to Y.D. and Y.C.), and Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Cell Microenvironment (ZDSYS20140509142721429 to Y.D. and Y.C.).

Author contributions

Z.S. and Y.C. designed research; Z.S., G.L., X.Z., and Y.D. performed research; Z.S., H.J., and S.S. analyzed data; and Y.C. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Genomic studies data have been deposited in National Genomics Data Center of China (CRA007094) (66). All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Session A. M., et al. , Genome evolution in the allotetraploid frog Xenopus laevis. Nature 538, 336–343 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narbonne P., Simpson D. E., Gurdon J. B., Deficient induction response in a Xenopus nucleocytoplasmic hybrid. PLoS Biol. 9, e1001197 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibeaux R., et al. , Paternal chromosome loss and metabolic crisis contribute to hybrid inviability in Xenopus. Nature 553, 337–341 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitaoka M., Smith O. K., Straight A. F., Heald R., Molecular conflicts disrupting centromere maintenance contribute to Xenopus hybrid inviability. Curr. Biol. 32, 3939–3951.e6 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neyfakh A. A., Radiation investigation of nucleo-cytoplasmic interrelations in morphogenesis and biochemical differentiation. Nature 201, 880–884 (1964). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korzh V., Zygotic genome activation: Critical prelude to the most important time of your life. Methods. Mol. Biol. 2218, 319–329 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore J. A., Abnormal combinations of nuclear and cytoplasmic systems in frogs and toads. Adv. Genet. 7, 139–182 (1955). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kastan M. B., Onyekwere O., Sidransky D., Vogelstein B., Craig R. W., Participation of p53 protein in the cellular response to DNA damage. Cancer. Res. 51, 6304–6311 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaddavalli P. L., Schumacher B., The p53 network: Cellular and systemic DNA damage responses in cancer and aging. Trends. Genet. 38, 598–612 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson J. A., Lewellyn A. L., Maller J. L., Ionizing radiation induces apoptosis and elevates cyclin A1-Cdk2 activity before but not after the midblastula transition in Xenopus. Mol. Biol. Cell. 8, 1195–1206 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hensey C., Gautier J., A developmental timer that regulates apoptosis at the onset of gastrulation. Mech. Dev. 69, 183–195 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gentsch G. E., Spruce T., Owens N. D. L., Smith J. C., Maternal pluripotency factors initiate extensive chromatin remodelling to predefine first response to inductive signals. Nat. Commun. 10, 4269 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tchang F., Gusse M., Soussi T., Méchali M., Stabilization and expression of high levels of p53 during early development in Xenopus laevis. Dev. Biol. 159, 163–172 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owens N. D. L., et al. , Measuring absolute RNA copy numbers at high temporal resolution reveals transcriptome kinetics in development. Cell. Rep. 14, 632–647 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gentsch G. E., et al. , Innate immune response and off-target mis-splicing are common morpholino-induced side effects in Xenopus. Dev. Cell. 44, 597–610.e10 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bourdon J. C., et al. , p53 isoforms can regulate p53 transcriptional activity. Genes. Dev. 19, 2122–2137 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J., et al. , p53 isoform delta113p53 is a p53 target gene that antagonizes p53 apoptotic activity via BclxL activation in zebrafish. Genes. Dev. 23, 278–290 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hafner A., Bulyk M. L., Jambhekar A., Lahav G., The multiple mechanisms that regulate p53 activity and cell fate. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 199–210 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurdon J., Brown D., “Towards an in vivo assay for the analysis of gene control and function” in The Molecular Biology of the Mammalian Gene Apparatus, Ts’o P. O. P., Ed. (North-Holland Publishing Company, ed. 2, 1977), pp. 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bendig M. M., Persistence and expression of histone genes injected into Xenopus eggs in early development. Nature 292, 65–67 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rusconi S., Schaffner W., Transformation of frog embryos with a rabbit beta-globin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78, 5051–5055 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forbes D. J., Kirschner M. W., Newport J. W., Spontaneous formation of nucleus-like structures around bacteriophage DNA microinjected into Xenopus eggs. Cell 34, 13–23 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trendelenburg M. F., Oudet P., Spring H., Montag M., DNA injections into Xenopus embryos: Fate of injected DNA in relation to formation of embryonic nuclei. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 97 (Suppl.), 243–255 (1986). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ran R., et al. , Disruption of tp53 leads to cutaneous nevus and melanoma formation in Xenopus tropicalis. Mol. Oncol. 16, 3554–3567 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kruiswijk F., Labuschagne C. F., Vousden K. H., p53 in survival, death and metabolic health: A lifeguard with a licence to kill. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 393–405 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacroix M., Riscal R., Arena G., Linares L. K., Le Cam L., Metabolic functions of the tumor suppressor p53: Implications in normal physiology, metabolic disorders, and cancer. Mol. Metab. 33, 2–22 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiokawa K., et al. , Occurrence of pre-MBT synthesis of caspase-8 mRNA and activation of caspase-8 prior to execution of SAMDC (S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase)-induced, but not p53-induced, apoptosis in Xenopus late blastulae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 336, 682–691 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.R. Montes de Oca Luna, D. S. Wagner, G. Lozano, Rescue of early embryonic lethality in mdm2-deficient mice by deletion of p53. Nature 378, 203–206 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones S. N., Roe A. E., Donehower L. A., Bradley A., Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm2-deficient mice by absence of p53. Nature 378, 206–208 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crighton D., et al. , p53 represses RNA polymerase III transcription by targeting TBP and inhibiting promoter occupancy by TFIIIB. Embo. J. 22, 2810–2820 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaseva A. V., et al. , p53 opens the mitochondrial permeability transition pore to trigger necrosis. Cell 149, 1536–1548 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rius-Pérez S., Pérez S., Toledano M. B., Sastre J., p53 drives necroptosis via downregulation of sulfiredoxin and peroxiredoxin 3. Redox. Biol. 56, 102423 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamada K., Yoshida K., Mechanical insights into the regulation of programmed cell death by p53 via mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Cell. Res. 1866, 839–848 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujiwara A., Abe S., Yamaha E., Yamazaki F., Yoshida M. C., Uniparental chromosome elimination in the early embryogenesis of the inviable salmonid hybrids between masu salmon female and rainbow trout male. Chromosoma 106, 44–52 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakai C., et al. , Chromosome elimination in the interspecific hybrid medaka between Oryzias latipes and O. hubbsi. Chromosome. Res. 15, 697–709 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferree P. M., Barbash D. A., Species-specific heterochromatin prevents mitotic chromosome segregation to cause hybrid lethality in Drosophila. PLoS. Biol. 7, e1000234 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dion-Côté A. M., Barbash D. A., Beyond speciation genes: An overview of genome stability in evolution and speciation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 47, 17–23 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levine A. J., Tomasini R., McKeon F. D., Mak T. W., Melino G., The p53 family: Guardians of maternal reproduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12, 259–265 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gebel J., et al. , Control mechanisms in germ cells mediated by p53 family proteins. J. Cell. Sci., 10.1242/jcs.204859 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Okita K., et al. , An efficient nonviral method to generate integration-free human-induced pluripotent stem cells from cord blood and peripheral blood cells. Stem Cells. 31, 458–466 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niu L., et al. , Three-dimensional folding dynamics of the Xenopus tropicalis genome. Nat. Genet. 53, 1075–1087 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H., Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv [Preprint] (2013). 10.48550/arXiv.1303.3997. Accessed 25 November 2021. [DOI]

- 43.Ramírez F., et al. , deepTools2: A next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 44, W160–W165 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barisic D., Stadler M. B., Iurlaro M., Schübeler D., Mammalian ISWI and SWI/SNF selectively mediate binding of distinct transcription factors. Nature 569, 136–140 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quinlan A. R., Hall I. M., BEDTools: A flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miao L., et al. , The landscape of pioneer factor activity reveals the mechanisms of chromatin reprogramming and genome activation. Mol. Cell. 82, 986–1002.e9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ross-Innes C. S., et al. , Differential oestrogen receptor binding is associated with clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nature 481, 389–393 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heinz S., et al. , Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell. 38, 576–589 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eriksson P., et al. , A comparison of rule-based and centroid single-sample multiclass predictors for transcriptomic classification. Bioinformatics 38, 1022–1029 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim D., Paggi J. M., Park C., Bennett C., Salzberg S. L., Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Danecek P., et al. , Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10, giab008 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarasov A., Vilella A. J., Cuppen E., Nijman I. J., Prins P., Sambamba: Fast processing of NGS alignment formats. Bioinformatics 31, 2032–2034 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liao Y., Smyth G. K., Shi W., featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Love M. I., Huber W., Anders S., Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome. Biol. 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Szklarczyk D., et al. , The STRING database in 2021: Customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 49, D605–D612 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mi H., et al. , PANTHER version 16: A revised family classification, tree-based classification tool, enhancer regions and extensive API. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 49, D394–D403 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carbon S., et al. , AmiGO: Online access to ontology and annotation data. Bioinformatics 25, 288–289 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gene Ontology Consortium, The gene ontology resource: Enriching a GOld mine. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 49, D325–D334 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kanehisa M., Furumichi M., Tanabe M., Sato Y., Morishima K., KEGG: New perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 45, D353–D361 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu G., Wang L. G., Han Y., He Q. Y., clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics 16, 284–287 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hunter J. D., Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luo W., Brouwer C., Pathview: An R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and visualization. Bioinformatics 29, 1830–1831 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang Y., et al. , Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome. Biol. 9, R137 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gu Z., Gu L., Eils R., Schlesner M., Brors B., circlize Implements and enhances circular visualization in R. Bioinformatics 30, 2811–2812 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Villanueva R. A. M., Chen Z. J., ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Meas-Interdiscip. Res. 17, 160–167 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shi Z., et al. , Activation of P53 pathway contributes to Xenopus hybrid inviability. Genome Sequence Archive. https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA007094. Deposited 2 June 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

Genomic studies data have been deposited in National Genomics Data Center of China (CRA007094) (66). All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.