Abstract

Introduction

Endoscopic transoral outlet reduction (TORe) has emerged as a safe and effective treatment option for weight regain after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB). Factors that predict successful weight loss after TORe are incompletely understood. The aims of this study were to evaluate procedural factors and patient factors that may affect percent total body weight loss (%TBWL) after TORe.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed on patients after TORe. The primary outcomes were %TBWL at 6 and 12 months based on four procedural factors: purse-string (PS) vs. non-purse-string (NPS) suture pattern, gastric pouch sutures (N), change in the diameter of the gastrojejunal anastomosis, and change in the length of the gastric pouch. Secondary outcomes included patient factors that affected weight loss.

Results

Fifty-one patients underwent TORe. Weight loss for completers was 11.3 ± 7.6% and 12.2 ± 9.2% at 6 and 12 months. There was a correlation between %TBWL and change in pouch length at 6 and 12 months and number of sutures in the pouch at 6 months. The difference in %TBWL between PS and NPS groups at 6 months (PS, n=21, 12.3 ± 8.5% and NPS, n=8, 8.7 ± 3.7%) and 12 months (PS, n=21, 13.5 ± 9.2% and NPS, n=5, 7.0 ± 7.9%) did not reach statistical significance. For secondary outcomes, depression was associated with %TBWL.

Conclusion

Change in pouch length and number of sutures in the pouch correlated positively while depression correlated negatively with weight loss after TORe. Further studies are needed to understand these effects.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11605-023-05695-9.

Keywords: TORe, endoscopic suturing, obesity, gastric bypass

Introduction

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) is an effective treatment option for patients with obesity. On average, patients who undergo RYGB experience an initial average total body weight loss (TBWL) of 35-40% within 1 to 3 years of the operation and experience significant improvement in metabolic comorbidities such as diabetes and quality of life.1,2 However, despite a robust initial response, patients will regain an average of 20-30% of their lost weight by 10 years, and only 40% of patients successfully maintain 30% or greater %TBWL by 10 years.3–5 Although the cause of weight regain after RYGB is multifactorial, post-surgical anatomical abnormalities have been shown to play a large role. In particular, dilation of the gastric pouch and the gastrojejunal anastomosis (GJA) have both been shown to independently predict post-RYGB weight regain.6–9

In recent years, endoscopic transoral outlet reduction (TORe) has gained popularity as a minimally invasive method to reduce the size of the GJA and promote post-RYGB weight loss. TORe has been shown in multiple studies including a sham-controlled trial to effectively induce and maintain weight loss as early as six weeks and for up to 5 years after surgery.10–14 However, despite the long-term efficacy of TORe, factors that affect weight loss after TORe, such as procedure technique and pre-procedure patient characteristics, are poorly understood. Therefore, the aims of this study were to determine which procedure and patient factors were associated with weight loss in patients undergoing post-RYGB TORe.

Materials and Methods

Trial Design and Patient Selection

This was a retrospective cohort study performed on data collected at a single tertiary academic bariatric referral center from June 2017 to October 2021. Patients were eligible for TORe if they experienced inadequate weight loss after RYGB, defined as regain of > 20% of the weight lost or < 50% excess weight loss after RYGB surgery, and had a dilated GJA of > 20 mm with or without dilation of the gastric pouch (defined as > 3 cm in length).

Outcomes

Patient %TBWL at both 6 and 12 months were reported for those who completed therapy at each time point (Per Protocol, PP) and with the last observation carried forward for intention-to-treat analysis (ITT). The primary outcome was the association between 6- and 12-month %TBWL and the following procedural factors: PS vs NPS pattern in the GJA, number of sutures placed in the gastric pouch, pre- to post- procedural change in stoma diameter, and pre- to post- procedural change in gastric pouch length. Secondary outcomes included patient factors that predicted %TBWL at 6 and 12 months as well as serious adverse events. Data were recorded until 12 months as follow up after this point was limited.

When reporting PP weight loss at the 6- and 12-month time points, the weight recorded at the closest clinical encounter to the exact date within a range of ± 45 days was used. For patients who had a recorded weight outside of this window, the weight at last observation prior to 6 or 12 months was carried forward to perform an ITT analysis. Patients without any recorded weight from 0 to 6 months or from 6 to 12 months after TORe were counted as having missing data for those time periods, unless they had not yet participated in the study long enough to reach those respective time points. Patient risk factors studied included: age, sex, weight loss medications use, pre-procedure BMI, years from surgery, post-RYGB percent weight regain, and depression severity (measured per Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score). Both serious and non-serious adverse events were determined via manual chart review of clinic, urgent care, emergency department, and hospital visits viewable in the electronic medical record and classified per Food and Drug Administration criteria.15

Procedural Technique

A video of the procedure technique is included in Appendix A1. All TORe procedures were performed by a single operator as follows:

The margin of the GJA on the gastric side was first ablated using APC (effect 2, flow 0.8 L/min and 55-60 watts) for 1-1.5 cm circumferentially. After APC ablation, the diagnostic endoscope was switched out for a dual lumen endoscope with the Overstitch Endoscopic Suturing System (Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, TX) attached. The suturing system was used to place full thickness running stitches with one suture starting at the 5 o’clock position. All sutures were permanent 2-0 polypropylene (Prolene), monofilament. For the purse-string (PS) technique, this was continued circumferentially around the GJA with the last stitch crossed over the first stitch. A through-the-scope dilating balloon was then placed in the lumen of the GJA and inflated to 8 mm, and the suture was tightened around the balloon, cut, and cinched. For the non-purse-string (NPS) technique interrupted, modified figure of 8 or z-pattern sutures with or without an additional interrupted suture were placed in the anastomosis. Additional sutures were then placed in the gastric pouch, starting distally just proximal to the GJA. An initial running suture from the anterior to posterior gastric pouch wall was placed to support the GJA sutures. Then additional sutures were placed in a u-shape pattern with 6-8 bites. Gastric pouch sutures were placed in all gastric pouches ≥ 3 cm in length, and the number of sutures placed depended on the size of the gastric pouch. Pouches smaller than 3 cm were not sutured owing to technical difficulty maneuvering the endoscope with the suturing device through the limited space.

Patient Management

All patients were started on once daily proton pump inhibitor (PPI) one week before the procedure. Patients were also given aprepitant 80-120 mg and a scopolamine patch placed the night before the procedure. Peri-procedurally, patients were given ampicillin/sulbactam 3 grams IV, ondansetron 4-8 mg IV, and dexamethasone 4-8 mg. Two liters of lactated ringer’s solution were given to all patients without significant heart failure or renal insufficiency. Patients were discharged from the endoscopy lab with prescriptions for sucralfate, ondansetron 8 mg x 7 days, lorazepam 0.5 mg x 10 tablets to be used as needed, and hydrocodone/acetaminophen 7.5/325 mg x 7 doses to be used as needed. They were told to continue their PPI.

Post-procedure dietary instructions included liquids starting 24 hours before the procedure and nothing by mouth after midnight before the procedure. Patients were started on clear liquids for 72 hours after the procedure then advanced to a full liquid diet. As of 2020, the full liquid diet was continued for a total of 6 weeks before advancing to a pureed diet from weeks 6-8 and starting soft food after week 8. Patients had clinical follow up at one week, one month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after TORe and were instructed to continue monthly bariatric surgery support groups for this entire period.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed for all variables, and baseline characteristics were reported using mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and percentages for binary outcomes. Bivariate analysis was performed for the primary and secondary outcomes of interest. The PS and NPS groups were compared using a Student’s t-test, and simple linear regression was performed to test for associations between %TBWL and each other primary and secondary outcome of interest. For each model, 6- and 12-month weight from the intention-to-treat analysis was used and adjusted for individual follow up time. The effect size (β) and 95% confidence interval for each model were reported, with significance for each comparison defined as having a test statistic with p < 0.05. All analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The study was considered exempt by the institutional IRB.

Results

Fifty-one patients underwent TORe during the study time period (Female: 94.1%, age: 47.7 ± 8.0 years, baseline BMI: 39.9 ± 7.5 kg/m2, Table 1). The mean time from baseline RYGB to TORe was 10.2 ± 5.8 years and % weight regain after RYGB and prior to TORe was 50.5 ± 24.3%. Forty-seven patients (92%) were treated with weight loss medications, and 40/47 patients (85%) were started on weight loss medications prior to TORe. Prescribed weight loss medications included topiramate (44.6%), phentermine (25.5%), phentermine/topiramate (14.9%), bupropion (10.6%), bupropion/naltrexone (10.6%), liraglutide (6.4%), and semaglutide (6.4%). Of these patients, all either stayed on the same regimen or stopped weight loss medications alltogether post-TORe except for one patient who went from 25 mg to 50 mg topiramate twice daily. Fifteen patients (29.5%) reported mild depression prior to TORe treatment, and 13 patients (25.5%) reported at least moderate-to-severe depression prior to treatment. Only 3 patients were on psychiatric medications known to cause weight gain and these included paroxetine, lithium, and aripiprazole. All were started prior to TORe. No patient reported having an eating disorder prior to treatment.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and peri-procedural characteristics

| Baseline Characteristics | Observations* |

|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | |

| Age (years) | 47.7 ± 8.0 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 3 (5.9%) |

| Female | 48 (94.1%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 39.9±7.5 |

| Years from Surgery | 10.2 ± 5.8 |

| Percent Weight Regain | 50.5 ± 24.3 |

| Outpatient Weight before TORe (lbs) | 241.1 ± 51.0 |

| Depression Severity | |

| None | 23 (45%) |

| Mild | 15 (29.5%) |

| Moderate | 7 (13.7%) |

| Moderately Severe | 6 (11.8%) |

| Severe | 0 |

| Procedural Characteristics | |

| Suture Type | |

| Purse-String | 43 (84%) |

| Non-Purse-String | 8 (16%) |

| Number of Pouch Sutures | 1.5 ± 0.9 |

| Change in Pouch Length (cm) | 2.7 ± 1.6 |

*Reported as mean ± SD for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables

For the TORe procedure, the PS technique was used for most cases (n=43, 84%) compared to NPS technique (n=8, 16%). The mean diameter of the stoma prior to TORe was 27.6 ± 5.6 mm, and the mean procedural change in stoma diameter was 19.7 ± 5.8 mm. The mean change in pouch length was 2.7 ± 1.6 cm. An average of 1.5 ± 0.9 sutures was placed in the gastric pouch, and the majority of patients had 2 sutures placed (n=21). No patient underwent repeat TORe during their 12 month follow up period.

Two patients did not have any follow up after TORe and were counted as having missing data. Analysis was performed on 49 patients who had at least some follow up therapy. Twenty-one (48%) patients in the PS group and 8 (100%) patients in the NPS group had complete 6-month weight loss data, and 21 (48%) patients in the PS group and 5 (63%) patients in the NPS group had 12-month weight loss data.

Per intention-to-treat analysis, the average %TBWL was 10.2 ± 6.9% at 6 months and 10.3 ± 7.7% at 12 months. For the per protocol analysis, %TBWL was 11.3 ± 7.6% (n=29) and 12.2 ± 9.2% (n=26) at 6 and 12 months among all patients. Among 6-month completers, the difference in %TBWL between patients who had PS vs. NPS TORe was 3.6% (PS: 12.3 ± 8.5% and NPS: 8.7 ± 3.7%, p=0.15). The difference in %TBWL at 12 months was 6.5% (PS: 13.5 ± 9.2% and NPS: 7.0 ± 7.9%, p=0.14). These differences did not reach statistical significance (Table 2).

Table 2.

%TBWL after TORe at 6 months and 12 months

| Post – Procedure Weight Loss Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Group | 6-month %TBWL | 12-month %TBWL |

| All (intention-to-treat) | 10.2 ± 6.9% | 10.3 ± 7.7% |

| All (per-protocol) | 11.3±7.6% (n=29) | 12.2±9.2% (n=26) |

| Purse-String | 12.3±8.5% (n=21) | 13.5±9.2% (n=21) |

| Non-Purse String | 8.7±3.7% (n=8) | 7.0±7.9% (n=5) |

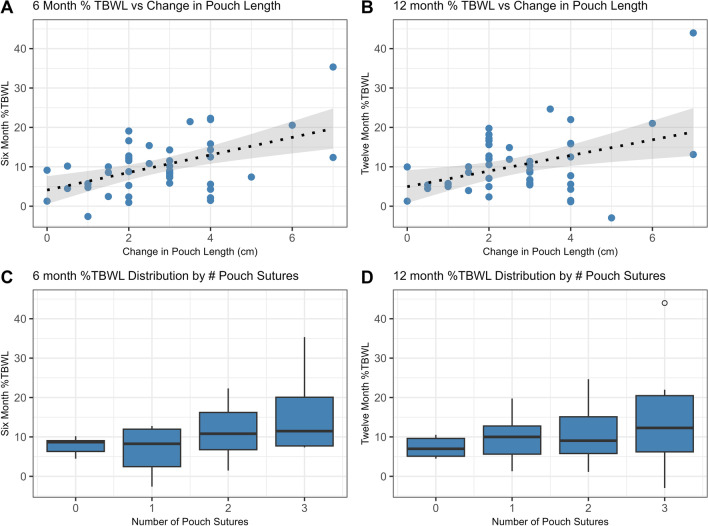

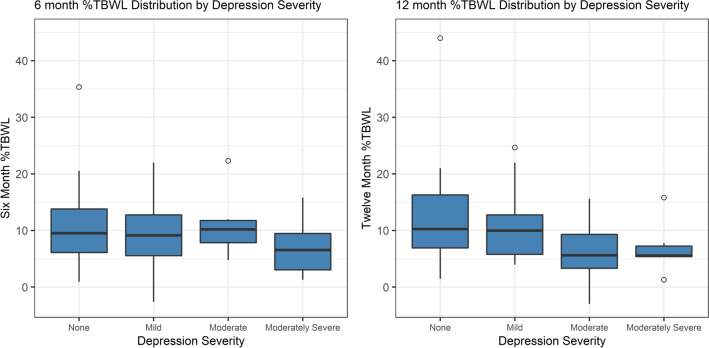

Simple linear regression revealed a correlation between %TBWL and change in pouch length at 6 months and 12 months (6-month ß = 2.19 [95% CI = 1.09-3.29], p = 0.0002; 12-month ß = 1.94 [0.62-3.26], p = 0.005, Fig. 1a and b) and number of sutures in the pouch but only at 6 months (6-month ß = 3.46 [1.38-5.53], p = 0.0016; 12-month ß = 2.11 [-0.31-4.69], p = 0.0845, Fig. 2a and b). Change in stoma diameter was not found to significantly correlate with weight loss at either six or twelve months. Among patient factors, only depression was associated with %TBWL at 12 months (6-month ß = -1.11 [-2.99-0.77], p = 0.24; 12-month ß = -2.20 [-4.22—0.18], p = 0.0335, Fig. 2). No significant change in %TBWL was found for age, gender, weight loss medication use, number of years after RYGB, or percent weight regain after RYGB.

Fig. 1.

Correlation between %TBWL and change in pouch length at 6 months (A) (p <0.05) and at 12 months (B), (p <0.05) and correlation between %TBWL and number of pouch sutures at 6 months (C) (p <0.05) and at 12 months (D)

Fig. 2.

Negative correlation between depression and %TBWL at 6 and 12 months (p < 0.05)

Serious adverse events occurred in 2 patients. One patient experienced a perforated marginal ulcer 5 days after TORe in the setting of proton pump inhibitor noncompliance, dietary noncompliance, and smoking cessation noncompliance and improved with exploratory laparotomy and repair of the GJA perforation with an omental patch. One patient had a bleeding event after receiving a heparin bolus during hemodialysis 10 days after the TORe procedure that required hospital admission, blood transfusion, and endoscopic therapy. Non-serious adverse events included intraprocedural bleeding treated endoscopically during the procedure without sequalae or need for blood transfusion (4%), nausea (41%), vomiting (18%), and abdominal pain (12%). Four patients in the purse-string group experienced GJ stenosis manifested by nausea and vomiting after TORe and required repeat EGD with dilation of the anastomosis.

Discussion

In this study, alterations in the gastric pouch, namely change in pouch length and number of sutures in the gastric pouch, independently correlated with the degree of weight loss after TORe in patients with weight regain or inadequate weight loss after RYGB. Among patient factors, depression severity was found to significantly correlate with the amount of weight lost after TORe. Across the entire cohort, TORe was generally effective at promoting weight loss after RYGB with a low SAE rate.

The effect of procedural technique on post-TORe weight loss has been described in several studies. In a single center study, Schulman et al. previously demonstrated the superiority of PS vs NPS TORe. In a single center retrospective analysis, %TBWL at one year in patients undergoing PS TORe, with suture bites placed radially around the GJA, was higher than in those treated with an interrupted suture technique (8.6% vs 6.4%, p = 0.02).12 Our data similarly demonstrated a clinical difference in %TBWL between the PS and NPS group at one year (13.5% vs 7.0%). This difference was not statistically significant however, which is most likely due to the small numbers of patients in our NPS group.

In a previous study by Jirapinyo et al., no significant correlation was found between number of sutures in the pouch or around the GJA and weight loss at five years after TORe.12 Our study is the the first to our knowledge to demonstrate that change in length of the gastric pouch after TORe has a significant effect on post-TORe weight loss at 6 and 12 months. This is also supported by a significant correlation between number of sutures used in the pouch and weight loss at 6 months, with a trend towards signficance at 12 months. Although surgical data has previously demonstrated16,17 a correlation between pouch size and weight loss, recent data has shown that endoscopic plication of the pouch can lead to significant weight loss after bypass surgery.18 This effect may be mediated by delayed gastric emptying, as TORe has previously been effectively used to treat dumping syndrome.19 Despite these associations, there currently is no standard accepted cutoff for a normal versus abnormal pouch size,7 and our data further support that the role of gastric pouch reduction during TORe deserves future study.

Stomal diameter has been previously shown to affect weight loss after operative revision of RYGB,20 but we did not find a correlation in our study. There are several possible explainations for this. First, the majority of patients in this analysis had PS suture technique in the GJA with standard cinching around a dilation balloon to 8 mm, resulting in very consistent final GJA diameter. Therefore, it is possible that the final post-TORe GJA diameter may be more important for weight loss than the change in diamter from pre-TORe to post TORe. Second, our findings regarding the significance of pouch length and number of pouch sutures and their effect on %TBWL suggest that changes in the pouch may play a larger role in post-TORe weight regain than previously recognized by gastroenterologists.

Regarding patient factors, Jirapinyo et al. previously demonstrated percent weight regain at index TORe and %TBWL at one year were significant predictors of %TBWL at 5 years.12 We did not find a correlation between the percent of weight regained at the time of TORe and weight loss at 6 or 12 months; however, our patients had a lower variability in percent weight regain based on a comparison of standard deviation, which was almost double in the population studied by Jirapinyo et al. This may explain a lack of correlation in our data set. Our study is the first to demonstrate a negative correlation between depression severity and post-TORe %TBWL. While the effect of patient factors including behavioral and mental health issues has previously been demonstrated to play a major role in weight regain after initial RYGB surgery,9,21 knowledge about the effect of mental health on weight loss outcomes in endoscopic bariatric therapy is still limited. While our study was not powered to detect the relative effect of mental health factors vs procedural factors on weight regain after TORe, our findings highlight the need to consider broader patient-centered approaches to addressing post-RYGB weight regain.

Our study has several limitations. Although the difference in clinical weight regain between PS and NPS groups was larger than that seen by Schulman et al., this difference was not statistically significant, likely due to the low number of patients in the NPS group. Since NPS GJA suturing technique is no longer performed at our institution, no further data collection will occur for NPS GJA suturing technique in this patient population. Although we tried to accurately capture variables relating to patient factors and procedural technique, our data collection does not completely account for variations in patient anatomy such as pouch angle or pouch width, as well as evolution in endoscopy technique that may have influenced outcomes. There was significant loss of patients to follow up, in part due to the unforeseen COVID-19 pandemic which resulted in cancellation of clinic visits for a number of patients. Moreover, many visits that did occur were telehealth, and only patient reported weights could be collected. To address this, an intention to treat analysis was included in our analysis, but we cannot exclude the possibility of differential missingness in patients who were lost to follow up. Due to loss to follow up, our study was also not powered to detect all but large effects in patient and procedural factors on %TBWL at the 12-month mark and analysis past the 12-month mark was not possible. Our study was similarly not powered to perform multivariable analysis, thus the relative strength of these effect sizes independent of other factors and the strength of procedural vs patient risk factors on post-TORe weight regain was not delineated. This may partially explain why some significant associations observed in our cohort at 6 months were not observed at 12 months. Most of the patients in this analysis were on weight loss medications. Patients may have already reached maximal medical weight loss benefit prior to the procedure or may have had poor response to concomitant medication therapy, however that data was not captured in this study, and further speculation on the effect of weight loss medications on outcomes after TORe cannot be made.

Conclusion

In summary, we demonstrated that TORe was safe and effective at treating weight regain or inadequate weight loss after RYGB. The change in pouch length and number of sutures in the pouch significantly correlated with %TBWL after TORe, suggesting that the size of the gastric pouch plays a significant role in weight loss. Among patient factors, depression negatively correlated with %TBWL. Further studies are needed to understand and mitigate this effect.

Supplementary information

(MP4 119849 kb)

Disclosures

Shelby Sullivan: Contracted research with Obalon Therapeutics, Aspire Bariatrics, Allurion Technologies, ReBiotix, Finch Therapeutics; Consulting for Allurion Technologies, Endo Tools Therapeutics, Nitinotes Surgical, Elira therapeutics, Fractyl Laboratories, Phenomix Sciences and Biolinq; Stock ownership/options: Elira therapeutics and Biolinq.

All other authors declare that they have no relationships to disclose.

Funding

No funding was provided for this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Author 7 (active within the last 24 months): Contracted research for Obalon therapeutics (ended), Aspire Bariatrics (ended), Allurion Therapeutics (active), Finch Therapeutics (ended), and ReBiotix (active); Consulting for Allurion (active), Biolinq (active), Endo Tools Therapeutics (active), Fractyl Laboratories (active), Elira Therapeutics (ended), Nitinotes Surgical (ended); Stock or Stock Warrents: Biolinq and Elira Therapeutics. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Matthew H. Meyers and Eric C. Swei contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al. Bariatric Surgery versus Intensive Medical Therapy for Diabetes — 3-Year Outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(21):2002–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gloy VL, Briel M, Bhatt DL, et al. Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Bmj. 2013;347:f5934. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christou NV, Look D, Maclean LD. Weight gain after short- and long-limb gastric bypass in patients followed for longer than 10 years. Annals of surgery. 2006;244(5):734–40. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217592.04061.d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jirapinyo P, Abu Dayyeh BK, Thompson CC. Weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has a large negative impact on the Bariatric Quality of Life Index. 2017;4(1):e000153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, et al. Weight and Metabolic Outcomes 12 Years after Gastric Bypass. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377(12):1143–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Athanasiadis DI, Martin A, Kapsampelis P, et al. Factors associated with weight regain post-bariatric surgery: a systematic review. 2021;35(8):4069-84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Heneghan HM, Yimcharoen P, Brethauer SA, et al. Influence of pouch and stoma size on weight loss after gastric bypass. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2012;8(4):408–15. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coakley BA, Deveney CW, Spight DH, et al. Revisional bariatric surgery for failed restrictive procedures. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2008;4(5):581–6. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karmali S, Brar B, Shi X, et al. Weight Recidivism Post-Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review. Obesity surgery. 2013;23(11):1922–33. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson CC, Chand B, Chen YK, et al. Endoscopic suturing for transoral outlet reduction increases weight loss after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):129–37.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jirapinyo P, Kröner PT, Thompson CC. Purse-string transoral outlet reduction (TORe) is effective at inducing weight loss and improvement in metabolic comorbidities after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Endoscopy. 2018;50(4):371–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-122380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jirapinyo P, Kumar N, AlSamman MA, et al. Five-year outcomes of transoral outlet reduction for the treatment of weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(5):1067–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulman AR, Kumar N, Thompson CC. Transoral outlet reduction: a comparison of purse-string with interrupted stitch technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87(5):1222–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar N, Thompson CC. Transoral outlet reduction for weight regain after gastric bypass: long-term follow-up. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(4):776–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.What is a serious adverse event? : U.S. Food and Drug Administration; [cited 2022 January 14]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/safety/reporting-serious-problems-fda/what-serious-adverse-event.

- 16.Riccioppo D, Santo MA, Rocha M, et al. Small-Volume, Fast-Emptying Gastric Pouch Leads to Better Long-Term Weight Loss and Food Tolerance After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Obesity surgery. 2018;28(3):693–701. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2922-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts K, Duffy A, Kaufman J, et al. Size matters: gastric pouch size correlates with weight loss after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(8):1397–402. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC. Endoscopic gastric plication for the treatment of weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;96(1):51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2022.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pontecorvi V, Matteo MV. Long-term Outcomes of Transoral Outlet Reduction (TORe) for Dumping Syndrome and Weight Regain After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horgan S, Jacobsen G, Weiss GD, et al. Incisionless revision of post-Roux-en-Y bypass stomal and pouch dilation: multicenter registry results. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2010;6(3):290–5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maleckas A, Gudaitytė R, Petereit R, et al. Weight regain after gastric bypass: etiology and treatment options. Gland Surgery. 2016;5(6):617–24. doi: 10.21037/gs.2016.12.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(MP4 119849 kb)