Abstract

RNA editing in Trypanosoma brucei inserts and deletes uridylates (U's) in mitochondrial pre-mRNAs under the direction of guide RNAs (gRNAs). We report here the development of a novel in vitro precleaved editing assay and its use to study the gRNA specificity of the U addition and RNA ligation steps in insertion RNA editing. The 5′ fragment of substrate RNA accumulated with the number of added U's specified by gRNA, and U addition products with more than the specified number of U's were rare. U addition up to the number specified occurred in the absence of ligation, but accumulation of U addition products was slowed. The 5′ fragments with the correct number of added U's were preferentially ligated, apparently by adenylylated RNA ligase since exogenously added ATP was not required and since ligation was eliminated by treatment with pyrophosphate. gRNA-specified U addition was apparent in the absence of ligation when the pre-mRNA immediately upstream of the editing site was single stranded and more so when it was base paired with gRNA. These results suggest that both the U addition and RNA ligation steps contributed to the precision of RNA editing.

Kinetoplastid RNA editing is a form of mitochondrial (mt) mRNA maturation in which uridylate residues (U's) are inserted and deleted (for recent reviews, see references 1, 26, 27). It is an essential step in the maturation of most mt RNAs in kinetoplastid protozoa since it creates start and stop codons and determines the mature coding sequence, often accounting for more than half of the sequence. The mature mRNA sequence is specified by small guide RNAs (gRNAs), which contain sequences complementary to short regions of edited mRNA, allowing G · U base pairs (6).

In vitro studies using mt extract from the kinetoplastid Trypanosoma brucei (8, 15, 25) indicate that RNA editing occurs by a series of enzymatic reactions, including endonucleolytic cleavage, U addition or removal, and RNA ligation (6). Initially, gRNAs form an anchor duplex with the pre-mRNA immediately downstream of the sequence to be edited. The pre-mRNA is cleaved at a point upstream and adjacent to the anchor duplex, thus selecting the editing site (ES). This cleavage produces a 5′ fragment with a 3′-terminal hydroxyl and a 3′ fragment with a 5′ phosphate (20, 25). The 5′ cleavage fragment may be tethered to the 3′ region of the gRNA, and the gRNA in turn is stably associated to the 3′ fragment by the anchor duplex and also perhaps by association with one or more proteins. Tethering of the 5′ fragment may involve the 3′ oligo(U) tail of gRNA, by interaction with purine-rich sequences in the 5′ fragment and/or by RNA-protein interactions. During insertion editing, one or more U's from free UTP are added to the 3′ end of the 5′ cleavage fragment (15), while U's are removed during deletion to generate free UMP (13). Finally, the processed 5′ cleavage fragment is rejoined to the 3′ fragment extending the anchor duplex in the 5′ direction and yielding RNA edited at one ES. Kinetoplastoid RNA editing is catalyzed by a multiprotein complex, called the editosome or editing complex, that contains the RNA endonuclease, terminal uridylyl transferase (TUTase), 3′ U-specific exonuclease, and RNA ligase activities that catalyze the steps of editing (2, 10, 21, 22).

The insertion of U's appears to be directed by the guiding A's and, less often, G's, in gRNAs (6). However, how the number of U's inserted is specified by gRNAs is unknown. We explored which step(s) during U insertion editing determines the number of inserted U's. The cleavage step determines the site selected for editing, but it cannot directly specify the number of U's that are inserted. Hence, the precision in the number of U's that are inserted is likely to arise during the steps subsequent to cleavage—the U addition and RNA ligation steps. We developed a novel in vitro precleaved insertion editing assay that allows separate assessment of the U addition and ligation steps. This assay, which is an extension of an earlier in vitro assay (15), presents the pre-mRNA as two separate molecules that correspond to the 5′ and 3′ cleavage fragments. Using this system we have characterized the roles of U addition and RNA ligation in determining the number of U's added at the ES during insertion editing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of RNAs.

All RNAs used in this study were prepared by T7 polymerase (Promega) transcription of PCR-generated templates, except for the 3′ fragments 3′CL13pp and 3′CL3′p, which were purchased as RNA oligonucleotides from Oligos, Etc. Since T7 polymerase generates RNA transcripts with heterogeneous 3′ ends (19), the total length and the identity of the 3′-terminal G of 5′CL18 were verified by RNase T1 digestion of the T4 ligation product of 5′CL18 and 3′CL13pp. The presence of the 3′ phosphate on 3′CL13pp was verified by the inability to ligate [5′-32P]pCp to the 3′ end of this molecule using T4 ligase and using the same oligonucleotide lacking the 3′ phosphate as a control.

Template DNA for transcription was prepared by PCR from oligonucleotide pair templates. The transcription template for 5′CL18, the 5′ fragment used in these experiments, was prepared by PCR of 5′CL18-Tmp1 (5′-GGCGGAATTCTGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGAAGTATGAGACGTAGG-3′ and complementary sequence) using primers EcoRI T7 (5′-CGGCGGAATTCTGTAATACGACTCACTATAG-3′) and 5′CL18-3′ (5′-CCTACGTCTCATACTTCCTATAG-3′). Transcription templates for gRNAs gPCA6-0A, -1A, -2A, -3A, -4A, and -5A were prepared by PCR of gPCA6-3A-Tmp1 (5′-CGGCGGAATTCTGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGATATACTATAACTCCGATAAACCTACGTCTCATACTTCC-3′ and complementary sequence) with primers EcoRI T7 and gPCA6-0A-3′, -1A-3′, -2A-3′, -3A-3′, -4A3′, and -5A3′, respectively (5′-GGAAGTATGAGACGTAGG[T]nATCGGAGT-3′, where n equals the number of guiding A residues indicated in the name of the gRNA). Transcription templates for A6AC and A6AC5′CL were prepared by PCR of DNA encoding the pre-mRNA A6e-ES1 (15) with primers A6 Shorter (5′-GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGAAAGGTTAGGG-3′), containing the T7 promoter, and A6AC-3′ (5′-CTATAACTCCAATCAGTACTTTC-3′) and A6AC5′CL-3′ (5′-CAGTACTTTCCCTTTCTTCT-3′), respectively. Transcription templates for gA6[14]USD-1A, -2A, and -3A were prepared by PCR of plasmid pgA6[14]wt (15) with primers EcoRI T7 and gUSD-1A3′, -2A3′, and -3A3′, respectively (5′-AAAGAAAGGGAAAACTTCG[T]nATTGGAGTTATAG-3′). Radiolabeling of RNA at the 5′ terminus was performed either by capping, using [α-32P]GTP (DuPont NEN) and guanylyltransferase (Gibco-BRL), or by phosphorylation of alkaline-phosphatase-treated RNA with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Gibco-BRL) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP (DuPont NEN). Radiolabeling at the 3′ terminus was performed by ligation of [5′-32P]pCp (27). For RNA sequencing, a 10× preparative reaction was performed, and relevant RNA species were excised from the gel, eluted in 0.3 M NaOAc (pH 5.2)–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–1 mM EDTA, and precipitated. RNAs were sequenced using the Pharmacia enzymatic RNA sequencing kit.

Preparation of mt extract.

Mitochondria were isolated from procyclic T. brucei brucei strain IsTat 1.7a as previously described (14). Editing complexes were enriched from a 0.5% Triton X-100 mt lysate (21) by sequential SP Sepharose cation-exchange and Q Sepharose anion-exchange chromatography (A. K. Panigrahi et al., submitted for publication). Cleared mt lysate was bound to a 1-ml SP Sepharose column (Bio-Rad) in SP Sepharose buffer A (10 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.0], 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]), and fractions were eluted by a linear step gradient from 50 to 1,000 mM KCl. Fractions corresponding to 150 to 300 mM KCl were pooled and equilibrated to pH 8.3. Proteins in the pooled fractions were bound to a 1-ml Q Sepharose column in Q Sepharose buffer A (same as SP buffer A with 10 mM Tris [pH 8.3] replacing Tris-HCl [pH 7.0]) and eluted by another 50 to 1,000 mM KCl linear step gradient. Insertion-editing activity elutes from the Q Sepharose column at approximately 200 mM KCl (Panigrahi et al., submitted for publication). The fold purification of precleaved insertion-editing activity varied among preparations, but it was generally about 100-fold greater than in cleared mt lysate (Panigrahi et al., submitted for publication; R. P. Igo, Jr., unpublished results).

Assays for insertion editing of precleaved and uncleaved pre-mRNAs.

Editing reactions were performed in a total volume of 30 μl in a final concentration of 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.9)–10 mM Mg(OAc)2–5 mM CaCl2–50 mM KCl–0.5 mM DTT–1 mM EDTA. UTP was also present at 100 μM unless otherwise indicated. Editing reactions contained 50 fmol of labeled 5′ fragment, 0.5 pmol of gRNA, and 1 pmol of 3′ fragment. Substrate RNAs and gRNA were annealed prior to the reaction by incubation at 65°C for 2 min and then at room temperature for 15 min. Editing reactions were stopped by addition of 2 μl of 260 mM EDTA–2.5% SDS. Ligation during editing assays was prevented by addition of 4 mM pyrophosphate to the reaction mix 15 min prior to the addition of the RNAs or by use of a 3′ fragment with no 5′ phosphate, 3′CL3′p. To prevent interactions between labeled products and gRNA during electrophoresis, 25 pmol of nonradioactive A6PC (ligation product of 5′CL18 and 3′CL13) competitor RNA was added. After phenol-chloroform extraction and precipitation, the RNA was resuspended in 7 M urea–1× Tris-borate-EDTA containing 0.05% bromophenol blue and 0.05% xylene cyanol dyes, incubated at 100°C for 2 min, and immediately loaded on 18% (wt/vol) denaturing polyacrylamide gels. Reaction products were visualized on a Storm PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Quantification was performed using ImageQuaNT software.

Insertion editing of the intact (uncleaved) A6AC pre-mRNA was assayed in reactions containing 0.25 pmol of pre-mRNA and 0.5 pmol of gRNA, under the same reaction conditions as for the precleaved assay, except that ATP was added to a final concentration of 10 μM. Ligation activity during a full round of insertion editing was prevented by the presence of 0.4 mM pyrophosphate. Products of editing of uncleaved or precleaved A6AC RNA were separated on 9% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels.

Ligation reactions.

Assays for RNA ligation activity were performed in the same manner as editing assays, except that UTP was omitted from the reactions. T4 ligation reactions, used as an RNA size standard, contained the same quantities of 5′CL18, 3′CL13pp, and gPCA6-2A as in the insertion-editing reactions, plus 8 U of T4 RNA ligase (Gibco-BRL). These reactions were in a total volume of 10 μl of T4 ligase buffer (25 mM HEPES [pH 8.3], 5 mM MgCl2, 25 μM ATP, 1.6 mM DTT, 15% glycerol, 10% dimethyl sulfoxide) and were incubated 3 h at 4°C before phenol-chloroform extraction and RNA precipitation.

RESULTS

Editing of precleaved RNA.

The ability of preedited RNA that is presented as separate 5′ and 3′ fragments (Fig. 1) to be accurately edited in vitro was tested, since this would be useful for studies of the individual enzymatic steps of editing. The two fragments were designed to mimic the pre-mRNA cleavage products that result from the editing-associated endonuclease, and thus we refer to this as the precleaved editing assay. The fragments were based on the A6 pre-mRNA that was used to develop the in vitro editing system (15). The sequence of the 3′ fragment, 3′CL13pp, matches that of A6 pre-mRNA edited at ES1 (A6-eES1). It has a 5′ monophosphate like the 3′ cleavage fragment that is produced during editing (15, 23, 25), but a 3′ phosphate was added to prevent U addition to the 3′ terminus by TUTase activity during in vitro incubation. The sequence of the 5′ fragment, 5′CL18, has the same nucleotide composition but not the same sequence as the upstream region of pre-A6 mRNA; it is shorter than the 5′ fragment produced by cleavage of A6-eES1 (15) in order to maximize resolution of the products of editing on polyacrylamide gels. The sequences of the 5′ region of gPCA6 gRNAs match that of gA6[14] and thus can form the same anchor duplex with the 3′ fragment as in the native RNAs.

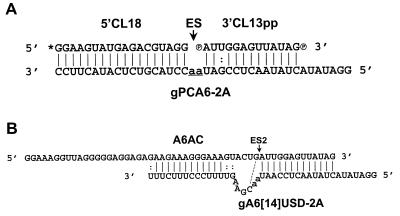

FIG. 1.

(A) Structure of the precleaved insertion-editing substrate RNAs aligned with gRNA. The 5′ cleavage fragment 5′CL18 and 3′ cleavage fragment 3′CL13pp are shown aligned with gRNA gPCA6-2A, which directs insertion of two U's at the ES. The asterisk denotes a 32P-labeled monophosphate or [α-32P]GTP cap. The ES is marked by an arrow, and guiding nucleotides are underlined in lowercase. 5′CL18 contains a 3′ hydroxyl group. 3′CL13pp contains a 5′ and 3′ monophosphate; the latter prevents U addition to the 3′ end of 3′CL13pp by TUTase activity. (B) Structure of A6AC pre-mRNA aligned with gRNA gA6[14]USD-2A. ES2 is indicated by an arrow, and guiding nucleotides are in lowercase. The potential base pair upstream of ES2 is indicated by a dashed line. The sequence of A6AC differs from that of pre-A6 mRNA edited at ES1 (4) in that a GU sequence 4 nt upstream of ES2 was replaced by AC. The information region of gA6[14] (17) was truncated and replaced with an oligopyrimidine sequence complementary to part of the upstream purine-rich region of A6AC.

Incubation of the 5′ and 3′ fragments with gRNA and mt extract containing active editing complexes under conditions that support in vitro insertion editing of pre-A6 mRNA (Fig. 2) resulted in edited RNA and products with added U's (U addition products) (Fig. 3A and B). The species marked U1, U2, and U3 in Fig. 3A represent the products of U addition to the 3′ end of the 5′ fragment, since they were generated in the presence but not the absence of UTP and were generated when the 5′ end of 5′CL18 was blocked by GTP capping (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 7; data not shown). In addition, no U's were added during this reaction to a 3′CL13 RNA labeled at its 3′ end with [5′-32P]pCp, showing that the 3′ phosphate of 3′CL13pp was not removed. Products marked E1, E2, and E3 in Fig. 3A had the correct mobility for edited RNA containing 1, 2, and 3 U's inserted at the ES, respectively. The identity of these edited products was confirmed by RNA sequencing (data not shown). The accurately edited product, containing the number of U's specified by the number of guiding A's in gRNA, represented more than 90% of the total ligation products of editing reactions containing a gRNA with 1, 2, or 3 guiding A's. Thus, the separate 5′ and 3′ fragments were accurately edited in a gRNA-directed fashion. Of the U addition products, those with the number of added U's specified by their respective gRNAs accumulated to the highest level. Addition products with fewer U's than specified by gRNA were also observed but were substantially less abundant. No addition products with more U's than specified by the gRNA were observed. Thus, there was preferential accumulation of addition products with the number of U's specified by the gRNA.

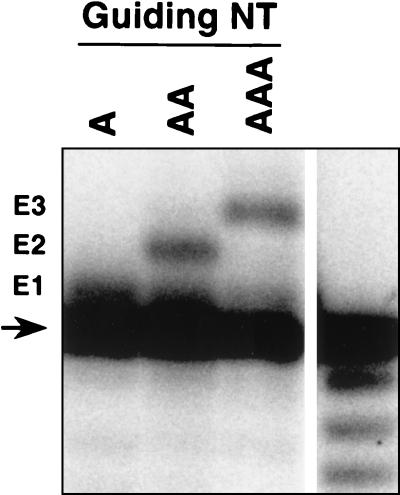

FIG. 2.

Insertion editing activity of T. brucei mt extract partially purified by SP and Q Sepharose chromatography. A6AC RNA was 3′ end labeled and incubated with gA6[14]USD-1A (A), -2A (AA), or -3A (AAA) in insertion-editing assays as described in Materials and Methods, and the reaction products were separated on a 9% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel along with a partial alkaline hydrolysis ladder (right lane). An arrow indicates the input RNA, and E1, E2, and E3 indicate edited products containing one, two, and three inserted U's, respectively. The one-U insertion product is incompletely resolved from the input.

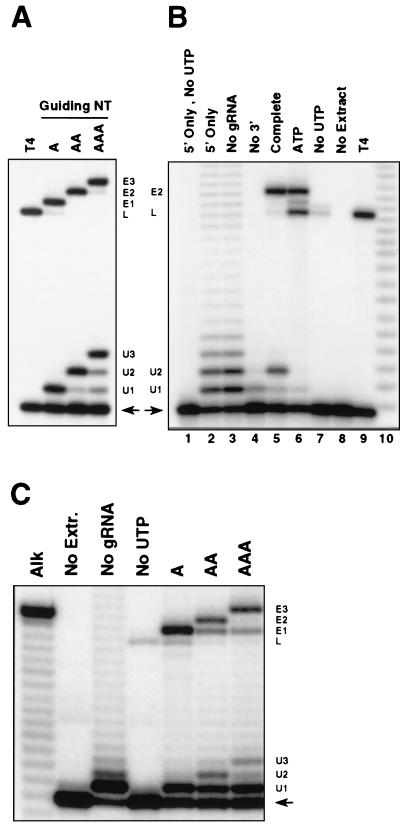

FIG. 3.

Accurate, gRNA-directed insertion editing of precleaved RNA substrates. Editing reactions, assembled as described in Materials and Methods and with variations as described below, were incubated 3 h at 28°C. The RNA products were separated in an 18% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The input 5′CL18 is indicated by an arrow. Products with one, two, or three added U's are indicated as U1, U2, or U3, respectively. L indicates ligated 5′CL18 and 3′CL13pp. Edited RNA with one, two, or three U's inserted at the ES are indicated as E1, E2, or E3, respectively. Lanes labeled T4 contain T4 ligase reactions with 5′CL18 and 3′CL13pp, as a size standard. (A) Products of precleaved editing reactions containing gPCA6-1A (A), gPCA6-2A (AA), and gPCA6-3A (AAA) (see Materials and Methods). (B) gRNA and substrate RNA requirements for precleaved editing. Conditions were as follows: lane 1, 5′CL18 RNA and UTP omitted; lane 2, 5′CL18 only; lane 3, 5′CL18 and 3′CL13pp RNAs and gRNA omitted; lane 4, 5′CL18 and gPCA6-2A RNAs and 3′ fragment omitted; lane 5, complete reaction with 5′CL18, 3′CL13pp, and gPCA6-2A RNAs (same as lane AA in panel A; see Materials and Methods); lane 6, complete reaction with 0.3 mM ATP; lane 7, complete reaction with UTP omitted; lane 8, complete reaction with mt extract omitted. Lane 10, partial alkaline hydrolysis ladder of A6 pre-mRNA, as a size standard. (C) Products of precleaved editing of A6AC pre-mRNA. Reactions were performed omitting mt extract, gRNA, or UTP, and complete reaction mixtures contained gA6[14]USD-1A (A), -2A (AA), and -3A (AAA). Reaction products are labeled as in panels A and B. Alk, partial alkaline hydrolysis ladder.

As expected, neither edited RNA nor the addition products were generated in the absence of UTP or mt extract containing active editing complexes (Fig. 3B, lanes 1, 7, and 8). Little +2-U addition product was produced when the 3′ fragment was omitted; indeed, the +1-U product was more abundant than the +2-U product (Fig. 3B, lane 4). Omission of the gRNA resulted in major products with 1 to 4 added U's, in descending order of abundance, plus a less abundant population of products with 10 to 40 added U's (Fig. 3B, lanes 2 and 3). It cannot be resolved from these data whether the products with few U's result from the simple addition of a few U's or the addition of many U's followed by the removal of most of them by U-specific exonuclease (18). None of these products was due to ligation with the 3′ fragment, since the products appeared in the absence of this fragment (lane 2), nor were they the result of circularization, since they appeared when the 5′ fragment was GTP capped (data not shown). The nucleotide addition activity was highly specific for U; addition of G's or A's was barely detectable even at 5 mM GTP or ATP, and addition of C's occurred with much lower efficiency than addition of U's (R. P. Igo, Jr., et al., unpublished data). Thus, accurate U insertion required all three RNA components, UTP, and mt extract containing active editing complexes.

Insertion editing of the A6AC pre-mRNA precleaved at ES2 (Fig. 1B) was also examined. U addition to the 5′ fragment of A6AC in the absence of gRNA yielded a very abundant product with one added U and much less abundant products with more than one added U. The preponderance of the +1-U-addition product remained in the presence of a gA6[14]USD gRNA containing 1, 2, or 3 guiding A residues. Some of this +1-U product was ligated in the presence of a gRNA with 2 or 3 guiding A residues. Nevertheless, the most prominent ligated product contained the number of U's specified by gRNA, as did the most prominent nonligated product besides the +1-U product. Thus, although U addition to precleaved A6AC was less gRNA specific than to a smaller substrate (Fig. 3A), it still appeared to be responsive to the gRNA sequence.

Insertion editing of precleaved A6-eES1 RNA was extremely inefficient and not always detectable, when directed by wild-type gA6[14] gRNA (15; data not shown). However, substantial edited RNA was generated when a stable Watson-Crick duplex between the gRNA and the 5′ fragment was allowed (Fig. 2). Edited RNA was also produced in the presence of gA6[14]COMP gRNA, in which the U tail of gA6[14] is replaced by a sequence which can form such a duplex (8), and in the presence of a 5′ fragment with base substitutions that allowed a duplex with the gRNA immediately upstream of the ES (data not shown). Editing of A6-eES1 RNA by the complete insertion reaction was also very inefficient in the presence of gA6[14], but it was 14-fold more efficient when the U tail of this gRNA was replaced by a sequence that was complementary to the 5′ fragment (data not shown). Thus, the ability to form a stable upstream duplex enhanced the ability of the RNA to be edited.

Under some conditions, ligation products of 5′CL18 and 3′CL13pp other than the accurately edited RNAs were observed. A small amount of the simple ligation product of 5′CL18 and 3′CL13pp with no inserted U's, designated L, was generated when UTP was omitted from the reaction (Fig. 3B, lane 7). However, a substantial amount of this ligation product was generated when 0.3 mM ATP was added, even in the presence of UTP (Fig. 3B, lane 6). The identity of this ligation product was confirmed by RNA sequencing (data not shown). In the absence of added ATP, the production of edited RNA with the sequence specified by the gRNA (Fig. 3B, lane 5) presumably reflected the activity of adenylylated (charged) ligase in the editing complex (see below). Charged ligase could also generate the very low level of ligated RNA (L) in the absence of UTP (Fig. 3B, lane 7). Thus, the inclusion of ATP appeared to have primarily stimulated nonspecific ligation, i.e., ligation of 5′ fragments without the number of added U's specified by the gRNA. The specific ligation activity was especially evident in the SP Sepharose-Q Sepharose fraction (see Materials and Methods). The active editing fractions from glycerol gradients and from Superdex-200 gel filtration chromatography had very low editing activity in the absence of added ATP, but the addition of ATP stimulated both accurate editing and nonspecific ligation (R. P. Igo, Jr., et al., unpublished results). The stimulation of nonspecific ligation in the presence of ATP may also have accounted for the production of a small amount of edited RNA with one inserted U, rather than the two specified by the gRNA (Fig. 3B, lane 6). While the efficiency of editing, as a percentage of total input, was similar when ATP was either present or absent, a prominent nonligated +2-U-addition product was not observed when ATP was included, suggesting that all of the available +2-U product was incorporated into edited RNA (Fig. 3B, compare lane 6 with lane 5). Overall these results suggested that RNA with the number of U's specified by the gRNA was preferentially ligated in the absence of ATP, presumably by charged ligase in the editing complex.

Time course of precleaved insertion editing.

The accumulation kinetics of the products of precleaved editing provided information on gRNA specificity. Using gRNAs specifying insertion of 1, 2, or 3 U's, the 5′ fragments with added U's appeared and accumulated early in the reaction and then reached or nearly reached a steady-state level within 1 h (Fig. 4). This paralleled the kinetics of accumulation of U addition products in an assay in which the pre-mRNA is cleaved by the editing complex (15). The edited RNA appeared after the 5′ fragments with added U's and continued to accumulate over the entire 3-h course of the incubation. Thus, the order of appearance and accumulation of U addition and ligation products closely resembled that of substrates that are cleaved during a full round of in vitro editing (15, 25). Accumulation of edited RNA continued at a gradually slowing rate for 16 h, although significant degradation of the input RNA occurred after 3 h (data not shown). Importantly, the nonligated product with the number of added U's specified by the gRNA accumulated to a higher level than did those products with fewer added U's. Furthermore, the products with fewer U's accumulated before those with more added U's and more quickly reached a steady-state level, suggesting stepwise U addition. These experiments further supported the hypothesis that the gRNA sequence determines the number of U's that are added during this step of editing, although U removal may also contribute to the preferential accumulation of the gRNA-specified product by removing U's added beyond the specified number.

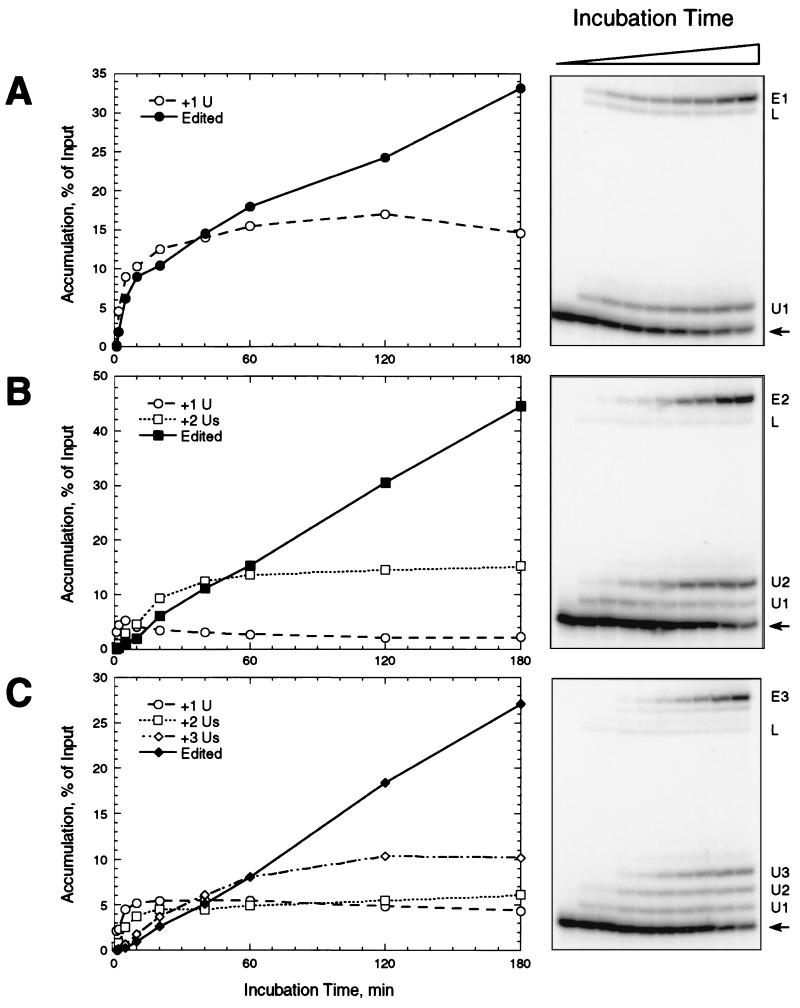

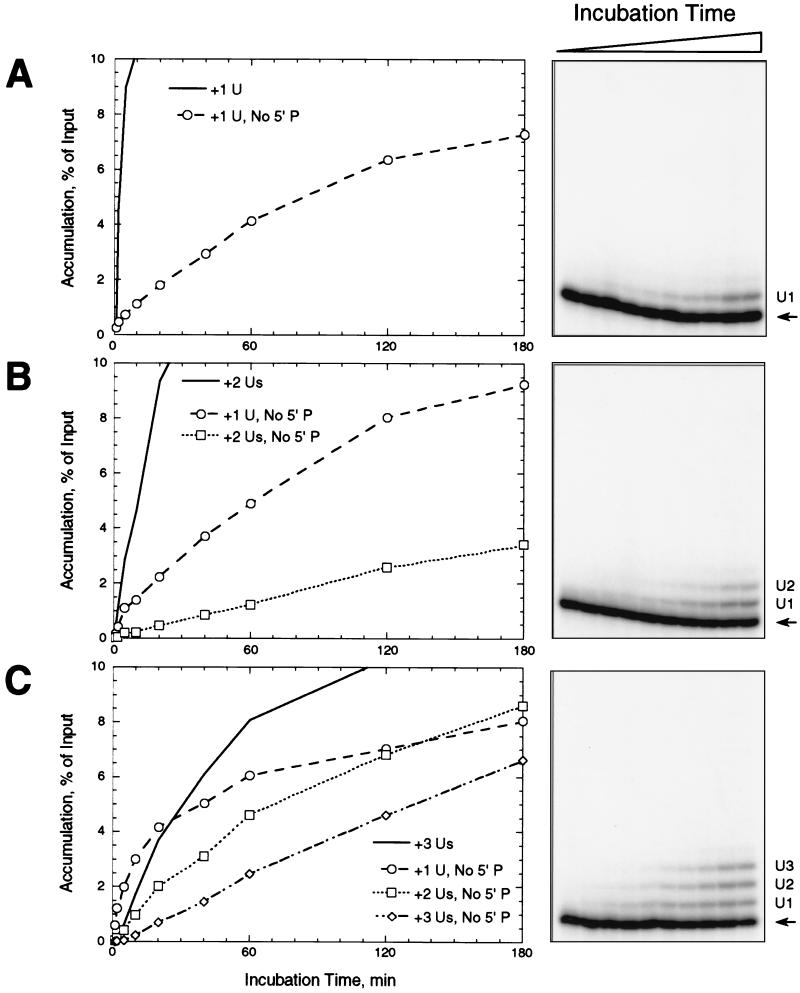

FIG. 4.

Time course of precleaved insertion. Precleaved editing reactions, with gPCA6-1A (A), gPCA6-2A (B), or gPCA6-3A (C), were incubated for various time periods at 28°C before adding stop buffer. Panels at right show denaturing polyacrylamide gels of the reaction products. U addition products and edited RNA are labeled as in Fig. 2. Graphs at left show the accumulation of products over time. Accurately edited RNAs are depicted by filled symbols and solid lines, while U addition products are depicted by open symbols and dashed or dotted lines (see legends of graphs).

The relative abundance of the products with added U's reflected the rate of ligation of each product. For each gRNA tested, the 5′ fragment with the number of added U's specified by the gRNA became most abundant, and the edited RNA which resulted from the ligation of that fragment accumulated to a much higher level than the other ligated products (compare Fig. 4A, B, and C), in a manner resembling RNA ligase activity observed in Leishmania tarentolae (5). Indeed, while the simple ligation product of the 5′ and 3′ fragments appeared within 2 min, its abundance did not increase appreciably over the course of the experiments despite the substantial abundance of the input 5′ fragment. The level of U addition products with more U's than specified by gRNA was less than 0.5% of input or undetectable throughout the time course (Fig. 4, right-hand panels). The formation of edited product initially closely followed the formation of the U addition product of the length specified by gRNA and continued after the specific U addition product reached a steady-state abundance. The order of appearance of the various intermediates and edited RNA was consistent with the smaller U addition products being intermediates in the reaction and the gRNA-specified U addition product being the immediate precursor of edited RNA.

U addition to the 5′ cleavage fragment without ligation.

The U addition step was examined in the absence of ligation, since the kinetic data suggested that products with the number of added U's specified by the gRNA may be the end product of this step. Ligation was prevented by pretreatment of the extract with pyrophosphate to deadenylylate the charged RNA ligase in the editing complex (22, 24) or by using a 3′ fragment that lacks the 5′ phosphate (5), unlike the 3′ fragment that is generated by the editing-associated endonuclease (20, 25). Pretreatment of mt extract with 4 mM pyrophosphate (Fig. 5, lanes 4 and 8) prevented ligation in reactions containing 5′CL18 and 3′CL13pp mRNA fragments and gRNA gPCA6-1A or gPCA6-2A. This indicated that ligation during precleaved editing in the absence of ATP was catalyzed by adenylylated ligase. Similarly, use of the 3′ fragment which lacked the 5′ phosphate, 3′CL3′p, rather than 3′CL13pp, also prevented ligation in editing reactions (Fig. 5, lanes 3 and 7). In addition, accumulation of gRNA-specified U addition products was reduced under both experimental conditions. There was a 25 to 35% reduction in the accumulation of the nonligated +1-U-addition product with gPCA6-1A (Fig. 5, compare lane 3 with lane 2) and an 80% reduction of the nonligated +2-U product with gPCA6-2A (Fig. 5, compare lane 7 with lane 6). When the edited products derived from these U addition products were included, the overall reductions of gRNA-specified addition products (ligated and nonligated) were greater than 85 and 95% with gPCA6-1A and gPCA6-2A, respectively. Pyrophosphate treatment itself inhibited U addition. In the absence of the 5′ phosphate, an additional inhibition of 75% occurred after pyrophosphate treatment (Fig. 5, compare lane 3 with lane 5 and lane 7 with lane 9). However, as mentioned previously, omission of the 5′ phosphate from the 3′ cleavage fragment by itself also reduced accumulation of gRNA-specific U addition products. With gPCA6-2A in the absence of the 5′ phosphate, the major U addition product contained only one U (Fig. 5, lane 7). Nevertheless, the maximum number of added U's was that specified by gRNA; the shift in the major U addition product was likely a result of slower U addition (see below). Products with added U's were reduced to barely detectable levels when the 3′ fragment with no 5′ phosphate was used along with the pyrophosphate pretreatment (Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 9); the accumulation of U addition products was reduced by more than 75% compared with omission of the 5′ phosphate alone (Fig. 5, compare lane 5 with lane 3 and lane 9 with lane 7). Although blocking ligation inhibited U addition, the addition was still clearly directed by the sequence of gRNA even in the absence of ligation, since no products with more U's than specified by gRNA accumulated in the absence of ligation.

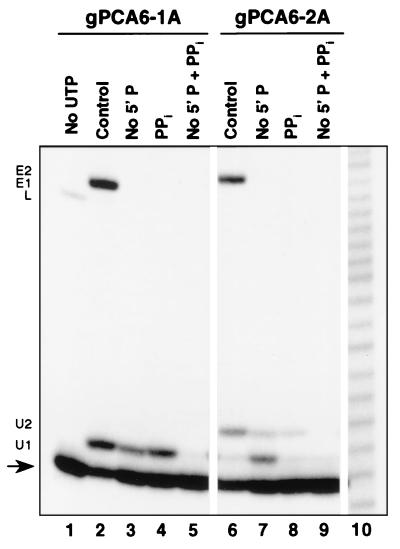

FIG. 5.

Uridylate addition to the 5′ fragment 5′CL18 in the absence of ligation. The 5′-end-labeled 5′ fragment, 5′CL18, was incubated for 3 h with gPCA6-1A (lanes 1 through 5) or gPCA6-2A (lanes 6 through 9), which specifies insertion of one or two U's, respectively. Ligation was prevented by pretreatment with 4 mM pyrophosphate for 15 min at 28°C (PPi) and/or by use of a 3′ fragment with no 5′ phosphate, 3′CL3′p (No 5′ P), as indicated. The input 5′CL18 (arrow), resultant addition products (U1 and U2), ligation product with no inserted U's (L), and RNA edited by the insertion of one (E1) or two (E2) U's are indicated. UTP was omitted in the negative control (lane 1). Partially hydrolyzed A6 pre-mRNA was used for sizing (lane 10).

Pyrophosphate also inhibited full-round insertion editing of A6AC RNA (Fig. 6A). The production of 3′ cleavage fragments at 40 μM pyrophosphate, which substantially inhibited editing, indicated that the loss of editing activity did not occur at the cleavage step. Pyrophosphate did partially inhibit cleavage at and above 400 μM. U addition did occur to the 5′ fragment of 5′-end-labeled A6AC during full-round editing, although the addition products were not abundant, most likely reflecting partial inhibition of cleavage and U addition by pyrophosphate (Fig. 6B). Importantly, the major U addition products contained the number of added U's specified by gRNA or fewer. Products with more U's than specified were very low in abundance or not detectable. U addition to the 5′ fragment of precleaved A6AC RNA in the presence of pyrophosphate was also gRNA specific, although less so (Fig. 6C). Although a low level of multiple-U addition occurred in the presence of gRNA, the most prominent addition product, besides the +1-U product, contained the number of added U's specified by gRNA. Therefore, the inhibition of editing of the uncleaved A6AC pre-mRNA by pyrophosphate resulted from prevention of the ligation step, and U addition was still responsive to the gRNA sequence under conditions in which ligation did not occur.

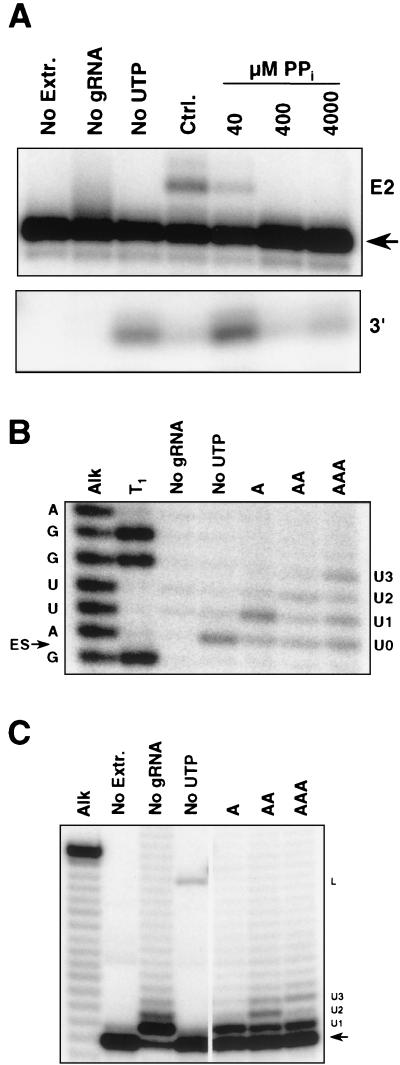

FIG. 6.

U addition to the 5′ fragment of A6AC RNA without ligation. (A) Inhibition of insertion editing by pyrophosphate. Editing reactions containing 3′-end-labeled A6AC and gA6[14]USD-2A were preincubated for 15 min at 28°C in the presence or absence of pyrophosphate. The input A6AC (arrow), edited product containing two inserted U's (E2), and the 13-nt 3′ cleavage fragment (3′) are indicated. (B) U addition to the 5′ fragment of A6AC during the uncleaved editing assay. Reactions contained 5′-end-labeled A6AC and no gRNA, gA6[14]USD-1A (No UTP and A), -2A (AA), or -3A (AAA) and were preincubated with 400 μM pyrophosphate. Lane T1 is a partial RNase T1 digest of 5′-end-labeled A6AC. The ES2 cleavage site is marked by an arrow. Cleavage fragments with no added U's (U0), and one (U1), two (U2), and three added U's (U3) are indicated. (C) U addition to the 5′ fragment of precleaved A6AC. Reaction conditions were the same as described in panel B. Reaction products are marked as in Fig. 3C.

Time course of U addition without ligation.

In order to analyze further the specificity of U addition without ligation, kinetic assays similar to those of Fig. 4 were performed under conditions that prevented ligation (Fig. 7). Products with added U's did not reach a steady-state level during a 3-h incubation, and they accumulated more slowly in experiments using 3′CL3′p, a 3′ fragment that lacks the 5′ phosphate, than when the 5′ phosphate was present (compare Fig. 7 to Fig. 4). The products with the number of U's specified by the gRNAs accumulated to a much lower level in the absence of the 5′ phosphate during the course of the experiment. However, products with fewer U's than specified by the gRNAs accumulated to a higher level by 3 h (compare Fig. 7 to Fig. 4). Thus, the rate of accumulation rather than the ultimate level was reduced by omission of the phosphate. Nevertheless, omission of the 5′ phosphate did not impair the gRNA-specificity of the U addition reaction since U addition terminated with the number of U's specified by the gRNA (Fig. 7, right-hand panels).

FIG. 7.

Time course of U addition in the absence of ligation. Precleaved insertion reactions were performed as described in the legend of Fig. 3, except that 3′CL3′p, lacking the 5′ phosphate, was used in place of 3′CL13pp. Symbols and lines for nonligated U-addition products are the same as in Fig. 3. The solid lines without symbols show nonligated U-addition products formed in the presence of the 5′ phosphate, from Fig. 3. Note differences in scale from Fig. 3 in the graphs at left.

gRNA specificity of ligation.

We studied the gRNA specificity of RNA ligation in the absence of U addition by performing editing reactions in the absence of UTP. Ligation of 5′CL18 and 3′CL13pp was measured as a function of the length of “gap” between the ligatable RNA termini bridged by gRNA (Fig. 8A) (5). The gap consists of the guiding A nucleotides, which separate the ES termini of the cleavage fragments annealed to the upstream and downstream regions of the gRNA. The precleaved substrate was ligated most rapidly when splinted by a gPCA6 gRNA containing no A residues at the ES (gPCA6-0A), presumably by bringing the RNA termini into close apposition (Fig. 8B, gap length 0). Accumulation of ligated RNA in the presence of this gRNA was linear for the first 15 min of incubation (data not shown); thus, we chose this length of time for measuring the effect of gap length. In reactions containing 0.3 mM ATP (Fig. 8B, +ATP), ligated product was generated most quickly when no gap was present between the 3′ and 5′ termini, and this activity decreased with each increase in gap length up to 5 nucleotides (nt). Significant ligation occurred even with a 5-nt gap. In the absence of exogenous ATP (Fig. 8B, -ATP), the efficiency of ligation dropped off much more steeply with increasing distance between the ligatable RNA termini. Without ATP, the ligation product was undetectable when the gap was greater than 3 nt in length. These results confirm those of Fig. 3B, in which addition of ATP to the precleaved insertion reaction increased the production of ligation products with the number of inserted U's other than that specified by the gRNA. By this direct analysis of ligation activity, ligation occurring across a gap of at least 1 nt was analogous to the formation of improperly edited products. Overall, increased gap length decreased the efficiency of ligation, as was seen for the L. tarentolae mt RNA ligase (5), indicating that preferential ligation of 5′ cleavage fragments of the correct length contributed to accuracy during precleaved editing.

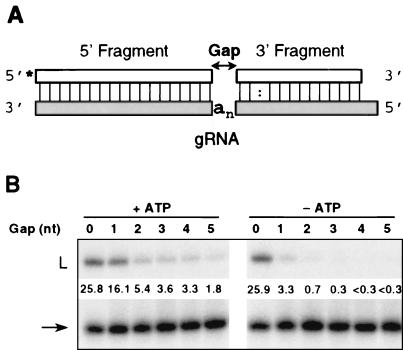

FIG. 8.

RNA ligation in the absence of UTP. (A) Pre-mRNA fragments aligned with gRNA, diagramming an n-nucleotide “gap” between 5′CL18 and 3′CL13pp. (B) Precleaved ligation reactions, in the presence (lanes 1 through 6) and absence (lanes 7 through 12) of 0.3 mM ATP, were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The input (arrow) and ligated (L) RNA species are indicated. The efficiency of ligation in each reaction is indicated below the ligated product, and it is expressed as the percentage of total input 5′CL18.

DISCUSSION

This study reports the development of a precleaved in vitro editing system, in which the pre-mRNA was provided as two fragments, and its use to examine the U addition and ligation steps of RNA editing. The 5′ fragments with the number of added U's specified by the gRNA preferentially accumulated during in vitro editing. The 5′ fragments with the number of U's specified by the gRNA were preferentially ligated with the 3′ fragment to produce accurately edited RNA. Thus, both the U addition and RNA ligation steps acted in concert to contribute to the specificity of the edited sequence.

The precleaved assay displayed all of the features of kinetoplastid insertion RNA editing consistent with the cleavage ligation model for editing (6). The reaction required gRNA, UTP, and mt extract that contained active editing complexes which were capable of catalyzing a full round of in vitro editing (Fig. 3B). It catalyzed the addition of U's to the 3′ end of the 5′ pre-mRNA fragment and generated accurately edited RNA by ligation with the 3′ fragment of 5′ fragments that had the correct (i.e., gRNA-specified) number of added U's (Fig. 3A). The kinetics of this editing reaction (Fig. 4) were similar to those of in vitro U-insertion-editing reactions that use pre-mRNAs which must be cleaved by the editing complex (15). In addition, the precleaved assay was efficient. Typically, 15 to 20% of input 5′ fragment was processed into accurately edited RNA, which was severalfold as efficient as in vitro editing of A6 pre-mRNA, which was not precleaved. This suggested that the endonucleolytic cleavage step can limit the rate of editing in vitro. Cleavage appeared to be rate limiting, using the SP and Q Sepharose purified mt extract, since a full round of editing of A6-eES1 RNA was no more efficient using this extract than that purified by glycerol gradient sedimentation (data not shown). The precleaved insertion activity also cofractionated, by several different purification strategies, with the activity that accurately edited RNA which was not precleaved, even though the individual TUTase and RNA ligase activities have different profiles in some cases (Panigrahi et al., submitted for publication). The U addition and ligation activities observed here remain to be conclusively shown to be components of the editing complex.

The efficiency of editing was very low for A6-eES1 precleaved at ES2, when gA6[14] was used, but it was more robust when the U-tail was replaced with a sequence designed to form a stable duplex with the 5′ fragment. A stable upstream duplex has been shown to enhance the efficiency of complete editing reactions as well (8, 16). In addition, partially purified mt RNA ligase from L. tarentolae requires an upstream duplex of 7 nt for optimal ligation of two substrate RNAs splinted by a complementary RNA molecule (5). Furthermore, a strong upstream duplex can counteract inhibition of insertion editing caused by modification of the 3′ end of gRNA (8). Finally, a stable duplex immediately upstream of the ES dramatically increases editing efficiency of NADH dehydrogenase subunit 7 RNA by crude L. tarentolae mt extract (16). These observations suggest that stable interactions between the 3′ region of gRNA and the 5′ pre-mRNA fragment enhance the efficiency of editing. This greater efficiency may be due to more closely tethering the 5′ fragment to gRNA, preventing chimera formation and also reducing religation (without U addition) by promoting base pairing of added U's with gRNA.

The step of U addition to the 3′ end of the 5′ pre-mRNA fragment appeared to be gRNA specific. Abundant products with the number of added U's specified by the gRNA accumulated (Fig. 2 and 3). This activity was highly specific for U; other nucleotides were added very inefficiently, if at all, even in the presence of complementary “guiding” nucleotides. Thus, the observed U addition was unlikely to have been the result of an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. In addition, prevention of ligation by using a 3′ fragment that lacks a 5′ phosphate or by pyrophosphate treatment reduced the rate of U addition but did not prevent the accumulation of 5′ fragments with the correct number of added U's (Fig. 7). The basis for specific gRNA-directed U addition is unclear. It may be controlled by stopping U addition beyond the number of guiding nucleotides in gRNA, suggesting that it is a property of the enzyme that adds U's. Alternatively, it may occur by trimming of excess U's by a 3′ U-specific endonuclease (1). A robust U-specific exonuclease activity is present in the mt extract used in this study (Panigrahi et al., submitted for publication; D. Weston and S. Lawson, unpublished data) and may remove 3′ terminal U's not protected by base pairing (18). We did not observe ligation of 5′ cleavage fragments with more added U's than specified by gRNA, as was seen in L. tarentolae (9). This difference may reflect our direct analysis of intermediates and edited RNA rather than the indirect (i.e., primer extension) analysis of reverse transcription-PCR products of edited RNA. The differences may also be explained by differences in activity between L. tarentolae and T. brucei editing complexes or between crude mt extract (9) and our partially purified extract. However, our results would be consistent with the conclusions drawn in that study (9), if the removal of excess U's occurred very rapidly in our mt extract.

U addition in the precleaved assay appeared to be more gRNA specific than that previously observed in the complete insertion-editing reaction (15), in which the gRNA-specified addition product was not the most prominent nonligated addition product and in which U's appeared to be added beyond the gRNA-specified number. However, accumulation of U addition products appeared to be substantially restricted to those with the gRNA-specified number of added U's or fewer in A6AC RNA after cleavage during a complete editing reaction in which ligation was prevented (Fig. 6B). Nonligated addition products with more than the specified number of added U's were also observed in the precleaved A6AC editing reaction (Fig. 6C). This may reflect the weaker tethering of the 3′ terminus of the 5′ fragment to the gRNA, thus allowing TUTase to add multiple U's to the 5′ fragment (see below). In addition, the lower specificity observed earlier (15) may have resulted from the use of less pure mt extract. Although the specificity of U addition seemed to vary among substrate RNAs, accumulation of U addition products appeared to be responsive to the sequence of gRNA even in the absence of ligation activity.

The U addition activity was greatly affected by the presence of the 3′ fragment, 5′ phosphorylation of the 3′ fragment, and the ability of the ligase to ligate the two fragments. Dephosphorylation of the 3′ fragment or deadenylylation of the ligase slowed the U addition overall and also resulted in an increased accumulation of products with fewer U's than specified by the gRNA, compared to the correct addition product (Fig. 5). Omission of the 3′ fragment resulted in preferential accumulation of 5′ product with only a single added U using gRNA specifying the addition of two U's (Fig. 3B); this was also the consequence of slowing of U addition (data not shown). The accurate and efficient U addition that relied on the presence of a 3′ fragment with a 5′ phosphate may reflect the interactions among the pre-mRNA, gRNA, and editing complex. Indeed, removal of U's from a 5′ fragment in the presence of a gRNA specifying U deletion is also slowed in the absence of the 5′ phosphate (D. Weston, unpublished data), perhaps reflecting a similar effect of altered RNA-complex interaction. The importance of the gRNA in the specificity at the addition step is clearly illustrated by the production of a ladder of 5′ products with increasing numbers of added U's upon the omission of the gRNA (Fig. 3). This may reflect the altered context of the 5′ fragment, since its 3′ terminus is presumably single stranded in the absence of complementary gRNA. Alternatively, the 5′ fragment may not be bound by the editing complex and hence may not be associated with gRNA. Indeed, U addition without gRNA may simply be due to a TUTase activity not involved with editing, possibly the TUTase which adds U's to the gRNA tail.

The RNA ligation step also appeared to contribute to the accuracy of the edited RNA. The experiments presented here and elsewhere (15) show that although a family of 5′ fragments may differ in the number of U's produced during editing, those with the number specified by the gRNA are preferentially ligated to form edited RNA. The simplest explanation for this specificity is that base pairing of the correct 5′ fragment with the gRNA will place the RNA termini to be ligated in closer proximity than would be the case with incorrect 5′ fragments. The incorrect 5′ fragments could be ligated but appeared to do so at a lower efficiency (Fig. 6). Ligation of incorrect 5′ fragments appeared to be more efficient in the absence of the correct fragment (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 5 and 7). These characteristics of the RNA ligase activity in our mt extract were similar to those of partially purified mt RNA ligase from L. tarentolae (5). Potentially this preference reflects accessibility of the RNA termini to the active site of the editing-associated ligase.

The production of accurately edited RNA from the precleaved substrate occurred in the absence of added ATP. This is likely to have been due to the action of adenylylated ligase (11, 22, 24), since treatment with pyrophosphate eliminated the ATP-independent ligation activity (Fig. 5). Deadenylylation of RNA ligase in mt extract with 8 mM pyrophosphate during purification, before the Q Sepharose fractionation step, also greatly reduced ATP-independent ligation. However, ligation was unaffected in its gRNA specificity when ATP was added to deadenylylated RNA ligase, producing approximately equal levels of gRNA-specific and -nonspecific ligation products (R. P. Igo, Jr., unpublished results). The addition of low to moderate levels of ATP (<1 μM to 0.3 mM) stimulated ligation activity but only of incorrect pre-mRNA fragments, i.e., those with fewer added U's than specified by the gRNA (Fig. 2B and data not shown). Ligation of U addition products of correct length was unaffected by ATP (Fig. 3B), as was ligation of RNA termini with no gap (Fig. 8B). Cruz-Reyes et al. (11, 12) found that procyclic mitochondria contain 0.1 to 1 mM ATP and that increased ATP reduced the production of RNA that is accurately edited in vitro by U insertion. They concluded that this effect resulted from inhibition of endonucleolytic cleavage by ATP. However, unlike the precleaved assay, editing assays that rely on endonucleolytic cleavage of the pre-mRNA do not detect ligated fragments to which no U's are added (or removed), since these molecules have the same mobility as the input pre-mRNA. Hence the reduced editing observed by Cruz-Reyes et al. can also be explained by ATP-stimulated religation of 5′ fragments without added U's, which would reduce the pool of available 5′ cleavage fragments for U addition. The effect of ATP on precleaved editing reflects an increase in ligation activity but not U addition activity, as indicated by the reduction in nonligated U addition products (Fig. 3A, lane 6). The increased ligation may reflect activation of an RNA ligase that is not involved in editing or an editing RNA ligase that is not associated with the editing complex. Alternatively, it may reflect an inappropriate ATP-dependent step, such as mistimed adenylylation of the editing ligase or a conformational change in an editing complex protein allowing more efficient ligation but with reduced specificity.

Previous results indicate that ATP is required for accurate in vitro insertion editing using a 20S glycerol gradient fraction as the source of the editing complex (15). However, the 20S fraction has very low precleaved insertion activity in the absence of ATP (ca. 0.25% of input) compared to the fraction from SP Sepharose and Q Sepharose chromatography (15 to 20% of input), which contains more concentrated and more highly purified editing complexes (A. K. Panigrahi et al., submitted for publication). The SP Sepharose-Q Sepharose fraction has much more ligase activity in the absence of added ATP than does the 20S fraction (S. S. Palazzo, unpublished results). In addition, the less pure glycerol-gradient extract may contain inhibitors of ligase adenylylation or ligase activity, since the adenylylation activity of this extract increased after dilution of the extract (10). The increased accuracy of insertion completed by adenylylated ligase could indicate that RNA ligase is adenylylated prior to assembly of active editing complexes and that misedited products in the presence of abundant ATP are ligated by RNA ligase not associated with such complexes. We are currently characterizing the precharged ligase to determine whether it is identical to the adenylylated ligase described by Sabatini and Hajduk (24).

The results presented here show that the U addition and ligation steps act in concert to contribute to the generation of accurately edited RNA. The former adds the number of U's specified by the gRNA, and the latter preferentially ligates the 5′ fragment with the number of added U's specified by gRNA. However, several important issues are not yet resolved. Additional study is needed to determine the RNA structure that the editing-associated U addition enzyme requires for substrate recognition. Does the enzyme add U's to the 5′ fragment only when the 3′ terminal nucleotide is base paired with the gRNA, as the current results suggest, or does it polymerize U's which can form base pairs with the guiding A's or G's in gRNA, regardless of the RNA structure at the terminus? It is also unclear whether the activity that adds the U's to the 5′ fragment is the same as the U addition activity that occurs in the absence of gRNA (Fig. 3B) and which is measured in various assays for TUTase activity (3, 10, 22). The relationship of the activity that adds oligo(U) tails to gRNA (7) to the U addition seen here is also unknown. Our results also hint that adenylylation of RNA ligase may occur in a controlled fashion, perhaps with the participation of other factors, and hence be important to the mechanism and control of editing.

The precleaved assay is useful for elucidating the characteristics of the specific steps of editing. The relatively high efficiency of the reaction allows accurate, quantitative analysis of the effects of various editing conditions on the production of editing intermediates and end products under different experimental conditions, thus facilitating analysis of the factors that contribute to accurate editing during the U addition and ligation steps. Additionally, the independence from endonucleolytic cleavage allows study of the effects of gRNA and pre-mRNA sequences in and around the editing site that would normally disrupt cleavage. Such work is in progress in our laboratory.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank RoseMary Reed, Barbara Morach, and Nicole Carmean for their assistance in preparation of T. brucei mitochondria.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM42188 and HFSPO grant RG/97 to K.S. and NIH postdoctoral fellowship AI10312 to R.P.I.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfonzo J D, Thiemann O, Simpson L. The mechanism of U insertion/deletion RNA editing in kinetoplastid mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3751–3759. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.19.3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen T E, Heidmann S, Reed R, Myler P J, Göringer H U, Stuart K D. The association of guide RNA binding protein gBP21 with active RNA editing complexes in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6014–6022. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.6014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakalara N, Simpson A M, Simpson L. The Leishmania kinetoplast-mitochondrion contains terminal uridylyltransferase and RNA ligase activities. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18679–18686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat G J, Koslowsky D J, Feagin J E, Smiley B L, Stuart K. An extensively edited mitochondrial transcript in kinetoplastids encodes a protein homologous to ATPase subunit 6. Cell. 1990;61:885–894. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90199-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanc V, Alfonzo J D, Aphasizhev R, Simpson L. The mitochondrial RNA ligase from Leishmania tarentolae can join RNA molecules bridged by a complementary RNA. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24289–24296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum B, Bakalara N, Simpson L. A model for RNA editing in kinetoplastid mitochondria: “guide” RNA molecules transcribed from maxicircle DNA provide the edited information. Cell. 1990;60:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90735-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blum B, Simpson L. Guide RNAs in kinetoplastid mitochondria have a nonencoded 3′ oligo(U) tail involved in recognition of the preedited region. Cell. 1990;62:391–397. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90375-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgess M L K, Heidmann S, Stuart K. Kinetoplastid RNA editing does not require the terminal 3′ hydroxyl of guide RNA, but modifications to the guide RNA terminus can inhibit in vitro U insertion. RNA. 1999;5:883–892. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrne E M, Connell G J, Simpson L. Guide RNA-directed uridine insertion RNA editing in vitro. EMBO J. 1996;15:6758–6765. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corell R A, Read L K, Riley G R, Nellissery J K, Allen T E, Kable M L, Wachal M D, Seiwert S D, Myler P J, Stuart K D. Complexes from Trypanosoma brucei that exhibit deletion editing and other editing-associated properties. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1410–1418. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruz-Reyes J, Rusché L N, Piller K J, Sollner-Webb B. T. brucei RNA editing: adenosine nucleotides inversely affect U-deletion and U-insertion reactions at mRNA cleavage. Mol Cell. 1998;1:401–409. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruz-Reyes J, Rusché L N, Sollner-Webb B. Trypanosoma brucei U insertion and U deletion activities co-purify with an enzymatic editing complex but are differentially optimized. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3634–3639. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.16.3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruz-Reyes J, Sollner-Webb B. Trypanosome U-deletional RNA editing involves guide RNA-directed endonuclease cleavage, terminal U exonuclease, and RNA ligase activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8901–8906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris M E, Moore D R, Hajduk S L. Addition of uridines to edited RNAs in trypanosome mitochondria occurs independently of transcription. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11368–11376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kable M L, Seiwert S D, Heidmann S, Stuart K. RNA editing: a mechanism for gRNA-specified uridylate insertion into precursor mRNA. Science. 1996;273:1189–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5279.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapushoc S T, Simpson L. In vitro uridine insertion RNA editing mediated by cis-acting guide RNAs. RNA. 1999;5:656–669. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299982250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koslowsky D J, Riley G R, Feagin J E, Stuart K. Guide RNAs for transcripts with developmentally regulated RNA editing are present in both life cycle stages of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2043–2049. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McManus M T, Adler B K, Pollard V W, Hajduk S L. Trypanosoma brucei guide RNA poly(U) tail formation is stabilized by cognate mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:883–891. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.883-891.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milligan J F, Groebe D R, Witherell G W, Uhlenbeck O C. Oligoribonucleotide synthesis using T7 RNA polymerase and synthetic DNA templates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8783–8798. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.21.8783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piller K J, Decker C J, Rusché L N, Harris M E, Hajduk S L, Sollner-Webb B. Editing domains of Trypanosoma brucei mitochondrial RNAs identified by secondary structure. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2916–2924. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollard V W, Harris M E, Hajduk S L. Native mRNA editing complexes from Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. EMBO J. 1992;11:4429–4438. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rusché L N, Cruz-Reyes J, Piller K J, Sollner-Webb B. Purification of a functional enzymatic editing complex from Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. EMBO J. 1997;16:4069–4081. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.4069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rusché L N, Piller K J, Sollner-Webb B. Guide RNA-mRNA chimeras, which are potential RNA editing intermediates, are formed by endonuclease and RNA ligase in a trypanosome mitochondrial extract. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2933–2941. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabatini R, Hajduk S L. RNA ligase and its involvement in guide RNA/mRNA chimera formation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7233–7240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seiwert S D, Heidmann S, Stuart K. Direct visualization of uridylate deletion in vitro suggests a mechanism for kinetoplastid RNA editing. Cell. 1996;84:831–841. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stuart K, Allen T E, Heidmann S, Seiwert S D. RNA editing in kinetoplastid protozoa. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:105–120. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.1.105-120.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stuart K, Kable M L, Allen T E, Lawson S. Investigating the mechanism and machinery of RNA editing. Methods. 1998;15:3–14. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]