Abstract

Background:

Delay in parenthood and the related consequences for health, population, society, and economy are significant global challenges. This study was conducted to determine the factors affecting delay in childbearing.

Materials and Methods:

This narrative review was conducted in February 2022 using databases: PubMed, Scopus, ProQuest, Web of Science, Science Direct, Cochrane, Scientific Information Database, Iranian Medical Articles Database, Iranian Research Institute for Information Science and Technology, Iranian Magazine Database, and Google Scholar search engine. The search terms used included “delayed childbearing,” “delayed parenthood,” “delayed fertility,” “delay of motherhood,” “parenthood postponement,” “deferred pregnancy,” “reproductive behavior,” and “fertility.”

Results:

Seventeen articles were selected for final evaluation. The factors were studied at micro and macro levels. The factors in micro level fell into two classes: personal and interpersonal. Personal factors included extension of women's education, participation in the labor market, personality traits, attitude and personal preferences, fertility knowledge, and physical and psychological preparation. The interpersonal factors included stable relations with spouse and other important people. The macro level included supportive policies, medical achievements, and sociocultural and economic factors.

Conclusions:

Policy-making and enforcement of interventions, such as improvement of the economic conditions, increased social trust, providing adequate social welfare protection, employment, and support of families using such strategies as creating family-friendly laws, taking into consideration the conditions of the country will reduce the insecurity perceived by the spouses and contribute to a better childbearing plan. Also, improving self-efficacy, increasing couples' reproductive knowledge and modifying their attitude can be helpful to better decision-making in childbearing.

Keywords: Decision making, fertility, reproduction, reproductive behavior

Introduction

The increase in childbearing age is a global social issue that has become more pronounced over the recent decades in most countries with different cultural, social, and economic conditions.[1] The average age for the first birth has increased by 2 to 4 years over the past 20 to 30 years, surpassing the age of 30, in many countries.[2,3] According to the latest census in Iran, the highest increase in age-specific fertility rate has occurred in the group of urban women aged 35–39.[4] Nowadays, couples want fewer children and prefer to have their first child at an older age.[5] The optimum entry to parenthood is before the age of 30, and first pregnancies at later ages are considered delayed.[6] However, due to the limitations in fertility for those past the age of 35, pregnancy at the age of 35 and above is generally defined as delayed childbearing as well.[7] Delay in the birth of the first child is of special importance, for it will postpone subsequent births to ages with lower childbearing capability and reduce the chances of pregnancy.[8]

Delay in childbearing and the increase in the first pregnancy age in women is concomitant with a wide range of medical, economic, demographic, and social consequences.[9] The most crucial medical consequence is the risk of infertility.[10,11] The undesirable consequences of pregnancy caused by delay in childbearing include caesarian sections,[6,12] abortion,[11,12] prolonged labor,[13] preterm labor,[14,15] gestational diabetes, stillbirths,[16] hypertension,[17] placental complications and bleeding during the third trimester,[18] maternal mortality,[19] multiple pregnancies,[20] low birth weight,[19] and the occurrence of most chromosomal abnormalities, including Down syndrome.[18,19] The most notable economic consequences include increased costs, such as the costs of using Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) and prenatal screening and, also, increased healthcare costs.[11] The demographic consequences of delay in childbearing include the effect of delayed fertility on birth and fertility rates and the aging of the population.[3] Delay in the first pregnancy lowers the probability in women of having more than one or two children and may result in involuntary childlessness.[21] The social consequences of delay in childbearing include further competitive aims at later ages and complete avoidance of childbearing,[22] smaller families, intergenerational ramifications, emotional gaps, communication problems between parents and children, and issues in relations with grandparents.[3] Furthermore, low pregnancy rates due to delay in childbearing will have serious consequences for the labor market and retirement systems.[23,24] In a study, factors influencing childbearing decision-making were classified into three themes: individual, familial, and social.[25] The significance of the potential consequences of childbearing at later ages has caused the factors effective in postponed parenthood to be studied from demographic, medical, economic, and social perspectives. Thus, this study was conducted to determine the factors affecting the delay of childbearing.

Materials and Methods

This narrative review study was conducted in February 2022, using Google Scholar (as a search engine) and databases of PubMed, Scopus, ProQuest, Web of Science, Science Direct, Cochrane, Scientific Information Database (SID), Iranian Medical Articles Database (IranMedex), Iranian Research Institute for Information Science and Technology (IranDoc), and Iranian Magazine Database (MagIran). The search terms and keywords used included “delayed childbearing,” “delayed parenthood,” “delayed fertility,” “delay of motherhood,” “parenthood postponement,” “deferred pregnancy,” “reproductive behavior,” and “fertility.”

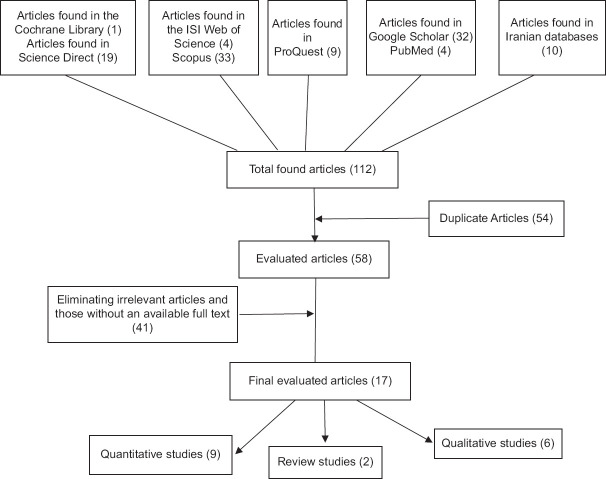

In the present study, first, the articles were retrieved using the search terms and their combinations after limiting the search time to articles published between January 2005 and January 2022. In addition, the reference list of the obtained articles was studied for a more comprehensive literature search. The initial search was as broad as possible, to the extent that in the first stage, 112 articles were extracted. English and Persian articles on the factors affecting the postponement of childbearing were included in this study. Articles that were not accessible in full text or were in languages other than Persian and English and gray articles were excluded from the study. In the second stage, the articles were evaluated in two steps, given the study's inclusion criteria. In the first step, after reviewing the title of the articles, 54 duplicate articles were excluded. In the second step, a total of 41 articles were excluded due to irrelevant titles, aims, and contents (34 articles) or inaccessibility of their full texts (7 articles) [Figure 1]. Finally, 17 articles were selected [Table 1]. It should be noted that the search process was conducted independently by two reviewers, and where there were disagreements, a third person was consulted. Data extraction tools were developed and used by the authors to analyze the results. The data were extracted, including the articles' aims, samples, authors, dates, and conclusions.

Figure 1.

The flowchart for the selection process of the articles

Table 1.

Studies of factors affecting childbearing delayed from 2005 to 2022

| Authors and Publication Years | Type of Study | Sample Size | Place of Study | Data-Gathering Tools | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Williamson et al., 2014[26] | Experimental | 69 young childless female students | Saskatchewan | Questionnaire | Fertility knowledge in the intervention group where young women received brief fertility information was significantly higher than in the control group where they received brief information about alcohol. The women in the intervention group reported being less intent on delaying childbearing than was the control group |

| Willett et al.,2010[27] | Cross-Sectional | 424 residents (women and men) | America | Questionnaire | Resident women, despite having more accurate knowledge of age-related fertility, were still intent on delaying childbearing; their most important reason was perceived threat and concern about extended residency training |

| de la Rica & Iza, 2005[28] | Cross-Sectional | 130,000 adults aged 16 and over (data from 12 European countries) | Spain | Questionnaire | Fixed-term employment contracts compared to indefinite contracts causing delayed motherhood for all childless women |

| Bretherick et al.,2010[29] | Quantitative | 360 Canadian undergraduate women | Canada | Questionnaire | While most students were aware of fertility decline with increasing age, significantly overestimated the odds of pregnancy at all ages and were unaware of the high rate of fertility decline with age. |

| Cooke et al., 2012[30] | Quantitative | 18 Women aged 35 and over | United Kingdom | semi-structured interview | Three main themes that emerged from all participant groups were; “within or beyond control,” “the chapters of life,” and “the need to know” |

| Lebano & Jamieson, 2020[21] | Qualitative | 35 childless women Italian and Spanish aged 30 to 35 years | Italy and Spain | Interview | Reasons for postponing childbearing included: “taking time” to achieve other goals or “stopping” to change the circumstances, optimism about the capacity to conceive, flexible norms about the “right age,” long-term dependence on one’s parents, the normative prominence of “perfect mothers” and family-unfriendly, gender-unequal workplaces. |

| Tough et al. 2007[31] | Mixed Methods | 1,006 women and 500 men (20–45-year-old) without children | Canada | Focus groups (women), interviews (men) and questionnaire | Four main factors were determined for delaying childbearing: financial security, partner’s suitability for parental interest or desire to have children, and partner’s interest or desire to have children |

| Benzies et al.,2006[25] | Qualitative | 45 Canadian women aged 20 to 48 | Canada | Focus groups and individual telephone interviews | Women felt that the current social expectation for personal independence before childbearing realized on a late motherhood schedule was more acceptable and normal. |

| Kearney & White, 2016[32] | Mixed method | 358 Australian women aged 18–30 years | Australia | Focus group and Questionnaire | Three psychosocial factors: attitude, pressure from others, and perceived self-confidence have a significant role as predictors of women’s intentions to delay childbearing, have strong accounting for 59% of the total variance |

| Behboudi-Gandevani et al., 2015[6] | Qualitative | 23 women aged under 30 | Iran | Semi-Structured Interviews | Three main themes and nine subthemes emerged in the study: “personal preference” (physical and mental readiness, stable relationship, and socioeconomic stability),” “perceived beliefs about the delay in childbearing” (attitudes toward childbearing, underestimation risks, gender beliefs, and concerns about the impact of childbearing on life) and “social support” (social acceptability, social facilities) |

| Mills et al. 2011[10] | Review | 139 Articles | America | Library research | The main reasons for postponing the first child: access to effective contraceptive methods, the extended women’s education, participation in the labor market and normative and value changes (including higher acceptance of childlessness), and lower levels of gender equality, delayed and more unstable partnerships, low availability and high costs of housing, Lack of family support policies and economic uncertainty and precarious forms of employment. |

| Cooke et al. 2010[33] | Meta-synthesis | Twelve papers | United Kingdom | Library research | Women who have delayed childbearing are divided into three groups: those who think they have enough information but may not have realized the dangers for themselves. Women who are unaware and become aware of the danger only when they are either pregnant or going to the clinic for infertility and the third group who are fully aware but still decide to delay childbearing |

| Brauner Otto et al. 2018[23] | Quantitative | Young men and women from age 18 until age 28, an analytic sample of 3,545 person-year observations from 1,465 respondents | America | Observation of data, from the 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2011 waves of the Transition to Adulthood (TA) study in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) | Men and women with lower incomes, lower education, and more concerned about their future careers were unsure whether to have children. Among those who expect to have children, those with higher education and more worries expect to have children later |

| Adachi et al.,2020[34] | Cross-Sectional | 388 couples seeking fertility treatment (219 women and 169 men) | Japan | Questionnaire | The three main reasons for delay in childbearing in women were “establishing relations,” “health problems,” and “financial security,” and in men, the reasons were “establishing relations,” “financial security,” and “lack of awareness of fertility”” |

| Smith, 2020[35] | Qualitative | 200 Married couples | Nigeria | Interview and observation | For Nigerian men, the main reason for delaying marriage and parenting is worrying about the economic burden and changing expectations. Nigerian men see having money as the basis for successful reproduction |

| Tavares, 2016[36] | Quantitative | 5,754 women under 80 | Italy | interview | From the five personality traits studied (the big five), openness is the most influential personality trait in terms of reproductive behavior, and higher levels of openness delay childbearing. The relation between openness and the time of the first childbirth is partly mediated by education |

| Kreyenfeld, 2010[9] | Quantitative | 5,998 female respondents of childbearing age (aged 15–44) | Germany | Interview | More educated women postpone their parenthood when faced with job insecurity, but women with lower levels of education often respond by becoming mothers |

Ethical considerations

The ethical code IR.MUI.RESEARCH.REC.1399.610 was acquired from the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. For this study, the data collected were used for scientific purposes, and the authors of this paper were committed to protecting the intellectual property of the authors of the studied articles in reporting their conclusions.

Results

Based on a review of the studies (17 articles), the factors affecting the delay in childbearing can be subdivided into micro and macro levels.

Micro level factors

According to the studies examined, the micro level factors affecting the delay in childbearing include personal and interpersonal factors.

Personal factors

Personal factors affecting the delay in childbearing include women's extended education, participation in the labor market, personality traits, fertility knowledge, attitude and personal preferences, and physical and psychological preparation.

Women's further education

Based on the studies, there is a significant inverse relationship between women's further education and earlier first births.[12,37,38,39] This is partly related to problems with creating a balance between the student role and the motherhood role.[10,40] Moreover, women with a higher education pursue more demanding professions that require further investment of time and energy.[41] In a study conducted by Brauner-Otto on education and the expected delay in childbearing in young people in the future, there was a significant relation between the two, and young people with higher education expected to have children at a later age.[23] Culturally, education impacts the ideas, values, wishes, preference for self-realization, employment, leisure time, and family life and promotes delay in childbearing.[41]

Participation in the labor market and job development

Numerous studies have indicated that for women, employment is the key factor in delay in childbearing.[3,12,42,43] Having conducted a meta-analysis, Matysiak and Vignoli concluded that employment had a negative impact on women's childbearing,[44] and another study indicated the same negative impact on the second childbirth.[45] Furthermore, several studies have concluded that having children is an obstacle to women's employment.[46,47] The challenges are more pronounced for jobs requiring higher skills and generally involving postgraduate studies. In a study, 64% of medical doctors postponed childbearing to pursue their medical professions.[48] Accordingly, Willet showed that female residents continued delaying childbearing, and their principal perceived threat posed by childbearing was the extension of their residency program.[27]

Personality traits

The relation between personality traits and the time of the first birth reveals itself in how the costs and benefits of childbearing are perceived. Of the Big Five personality traits, openness is the most effective in terms of reproductive behavior. The people with a higher level of openness pursue self-realization, believing that the mental costs of childbearing are high; hence, they do not have a positive attitude towards childbearing.[36]

Fertility knowledge

In one study, despite the reduced chances of pregnancy in the 36–40 age range, many had postponed childbearing for two or more years, and 32% of the women and 37% of the men in this age range still intended to have children. This group had overestimated their fertility potential.[49] Studies indicated that lack of sufficient awareness on the part of women of their biological capacity or their misunderstanding of their reproductive ability was the main reason for the delay in childbearing.[29,33,50,51] In these studies, women were either unaware of the age-related reduction of fertility or overestimated the chances of both spontaneous and assisted pregnancy.[15,52]

Attitude and personal preferences

The attitude to being a woman and mother affects the tendencies and behavior of childbearing. In a study, three psychosocial criteria, attitude, mental norm (the pressure from important people), and perceived self-efficacy, accounted for 59% of the total variance in the intention to delay childbearing. Of these cases, the positive attitude to childbearing in women aged 18–30 was the strongest predictor of the intention to delay childbearing.[32] Also, in one study, the attitudes, mental norms, and perceived behavioral control, combined, accounted for 61% of the variance in the intention to delay childbearing.[15]

Becoming a mother in today's world is no longer the work of fate; rather, it has changed into a choice and personal preference. Delay in childbearing arises from a preference and tendency to have a smaller family as a result of the second population transition, in which individualism, self-realization, choice, and personal development, direct many of the decisions about fertility.[9] In this regard, a study conducted by Schytt showed that 44% of 36-40-year-old Swedish men and women reported that a lack of desire to have children up to that age was the reason for their delay in childbearing.[49] Furthermore, a study indicated that, for men, the interest or desire of their partners for childbearing was the second factor in determining the time of childbearing.[50]

Physical and psychological preparation

Some health- and disease-related problems prevent the proper planning for childbearing.[53] In a study by Behboudi-Gandevani et al., and another study by Molina-Garcia, the participants believed that heart disease, diabetes, and other health-related problems were the medical reasons preventing them from deciding on a time for childbearing.[6,54] In one study, health problems were the second important reason for women to delay childbearing.[34] For many people, sufficient psychological maturity to assume childcare responsibility was seen as a prerequisite to parenthood. In another study, perceived self-confidence was recognized as a predictor of the intention to postpone childbearing.[32] Also, Behboudi-Gandevani showed that women postpone parenthood to achieve self-efficacy, which is an aspect of psychological preparation.[6]

Interpersonal factors

The interpersonal factors affecting delay in childbearing include stable relations with the spouse and with other important people (peers, colleagues, relatives, and close friends).

Stable relations with the spouse

A stable relationship between a man and woman and being a partner suitable for parenthood is the most crucial criterion for the decision about childbearing.[31] A study revealed that for childless men and women, after the mother's health, the most important factor for deciding about childbearing is having a supportive partner.[55] Benzies et al.[25] showed that a stable relationship with the spouse affects the decision about the time for becoming a mother.

Relations with other important people

“Other important people,” refers to the network of the surrounding relatives and nonrelatives (especially of friends and peers). Friends with children are an effective source of social pressure. In a study, women had a stronger preference for having children three years after their friends had children.[56] On the other hand, the individual's informal relations with their family and peers, considered social resources, played an important part in providing emotional and material support in planning for childbearing.[57] A study conducted in East and West Germany revealed that access (to relatives) for informal childcare considerably increased the probability of pregnancy and childbirth.[58]

Macro level factors

“Macro level factors” are the supportive policies, medical achievements, and sociocultural and economic factors that affect fertility in the community.

Supportive policies

The absence of supportive work-family policies, organizational policies on women's employment, such as the possibility to use childcare leave, low fringe benefits, and gender segregation, make it difficult or impossible to combine employment and motherhood, resulting in delays in childbearing.[31,59] In a study, 75% of the employed women with children reported they had to cope with job-family conflicts and that to create a balance between the roles, many of them had turned to part-time jobs after their first childbirth.[60] In a study conducted in Canada, about one-quarter of the women reported that support or lack of support at work affected their decision about the time of childbearing.[61]

Medical achievements in the prevention of pregnancy and modern infertility therapies

Access to safe, efficient, and reversible pregnancy prevention methods,[3,6,8,36] especially emergency methods,[12] has fostered women's independence in fertility; hence, they have achieved more effective control over fertility planning. A feeling of false security about pregnancy at older ages thanks to the advanced ART, and neglect of the fact that this technology would not fully compensate the effects of old-age pregnancy (except by egg donation), are other factors for delay in childbearing.[12,29]

Sociocultural factors

Today, the concept of “fertility” has changed into a social expectation. In a study by Benzies,[25] women believed that the increased social expectations for financial independence and stability prior to childbearing had made delay in childbearing acceptable to them. Due to the widespread use of information and communication technologies, social networks, and mass media, modern women have become more aware of their rights and are demanding the same social and family rights as men. Therefore, egalitarian attitudes postpone parenthood.[40] Some have referred to gender equality as the main factor in the perceived changes in fertility behavior.[10] A qualitative study revealed that women demanded the same job opportunities as their husbands, believing that delay in childbearing would protect them from social inequalities.[6] In a study, Spanish and Italian women reported that one reason for the delay in childbearing was their unfriendly work environment and gender inequality.[21] The increase in the divorce rate is another concern that forces women to pursue education and look for a job to achieve financial independence. In a study, women's awareness of and concern about the divorce rate in the community was reported to affect childbearing.[25]

Economic factors

The economic factors include employment status, children's expenses, consumerism, and increased costs of the opportunities for women.

Employment status

One of the main causes of delay in childbearing is economic insecurity,[6] a product of the uncertain labor market positions (labor market instability). Having compared 14 countries, Mills et al.[10] concluded that for young people, uncertain labor market positions, like temporary employment, job instability, or unemployment, would considerably increase the chances of postponing the first birth. Furthermore, a meta-analysis exploring the impact of unemployment and temporary employment on fertility in Europe revealed that people who had experienced periods of unemployment tended to postpone fertility.[62] In a qualitative study, British women felt they had no control over their childbearing time, for their financial stability was beyond their control.[30] In one study, for all the childless women, job instability and fixed-term employment contracts increased chances of postponed motherhood compared to employment contracts for indefinite periods.[28] In a study by Kreyenfeld, faced with job insecurity, the German women with a higher education postponed their childbearing.[9]

Children's expenses

Young people believe that the costs of childbearing prevented childbearing. Therefore, if they are vulnerable in terms of economic resources, they may decide to postpone childbearing until they are able to cover the expenses.[10] In a study, young people who believed that they were in a better financial position were more optimistic about becoming parents.[23]

Consumerism

According to studies, consumerism or increased consumer expectations is the gift of the modern lifestyle. With the development of consumerism, the cost-of-living increases, leading to decrease or delay in childbearing.[34,35,46]

Increased opportunity costs for women

For mothers who are either studying or employed, childbearing may be at the cost of losing opportunities. As a result, women restrict their childbearing to avoid it.[63] Transition to motherhood requires two important opportunity costs: a short-term opportunity cost which is losing income due to leaving work for delivery, and a long-term opportunity cost which is reduced future wages due to the effect of the job interruption on work experience such that if a mother had not left her job for childcare, she would have received higher wages due to higher work experience and job skills.[36]

Housing

Limited access to housing is a sociocultural factor leading to postponed parenthood. Large down payments for the purchase or rental of housing make it difficult for young people to become homeowners and affects their childbearing behavior.[10]

Discussion

This review was conducted to determine the factors affecting the delay in childbearing and showed that the delay in childbearing could be generally studied at both micro and macro levels. These influential factors interact at different levels, and their interaction and complexity determine the decisions of individuals during the time of childbearing. At the micro level, extension of women's education is one of the most important and most common motivating factors of delay in childbearing. Other factors affecting the scheduling of parenthood are either related to or the result of academic achievement.[41] Although having an education increases the income potential of individuals and prepares them for coping with childbearing costs, since the opportunity cost of childbearing is higher for educated women, they prefer to postpone childbearing until their career status is established.[11] Due to the conflict between work and family, as well as the challenges of keeping jobs and taking care of children, employed women largely suppress or postpone fertility. These findings are consistent with a review study by Mills et al.[10]

Changes in attitude and personal preferences are another major factor in delaying childbearing. Nowadays, couples tend to focus on self-actualization and fulfilling their other goals instead of having children.[10] Based on the theory of planned behavior, couples control their reproductive behavior by delaying childbearing to achieve other life goals. In the reviewed studies, attitudes toward parenthood play a key role in the timing of childbearing,[15,32] which can be justified by this theory. Based on studies, emotional and physical health is essential for the transition to parenthood.[6,32] The sense of immaturity for taking responsibility of the child is one reason for childbearing delay.[32] Consistent with this finding, Kariman expressed uncertainty about physical and psychological readiness as one of the effective factors in making decisions about having a child.[64] However, the most worrying reasons for the delay in childbearing in this study are poor knowledge about fertility and misunderstandings about reproduction potential, which have also been addressed in other studies.[29,33,51] According to studies, many see ART as an effective strategy for coping with age-related infertility, to the extent that even women over 40 hope to become pregnant using these methods.[3] To this end, it is essential that a team of health specialists explore the complexities of the factors affecting women's decisions and, then, provide them with the suitable sensitive information about older-age fertility risks.

According to the studies, achieving a stable relationship with the spouse is important regarding psychological readiness for childbearing.[6] For a young woman, childbearing is a significant source of stress, so uncertainty about the continuation of cohabitation, poor relationships with partners, and lack of emotional and practical social support can lead to delayed childbearing.[65] Studies have shown that the reproductive behavior of important people partly shapes the pattern of childbearing because important people form part of the normative atmosphere of the society a person lives in, and this affects reproductive choices and decisions, including fertility time.[56] In line with this study, Amerian showed that others, including parents, friends, relatives, and even neighbors, play an important role in women's decision-making in childbearing.[66] At the macro level, the economic conditions (employment status, income, and career prospects) are directly related to fertility behavior.[67] A review of the studies revealed that unfavorable economic conditions, such as increased unemployment, future job insecurity, job instability, and the changing housing market, affect parenthood planning in different ways.[11] Macroeconomic recession leads to financial insecurity on a micro and personal level. Lack of perceived trust in the future job prospects and economic prospects prioritizes educational and professional goals, and young people postpone childbearing to reach these goals.[67] Young people see childbearing as a burden requiring resources, and when they do not have the necessary economic resources, for example, job and income, their mental health is affected as well, and they will suffer from interpersonal conflicts in their relations,[23] which leads to delay in childbearing. In this process, the way the factors interact at micro and macro levels and their reinforcing effect on one another is tangible. Therefore, preventive policies must consider access to labor in the younger generation as an important factor in this regard. In Japan, employers prefer to employ the recently graduated to employing other groups. This policy will indirectly affect childbearing time and family formation.[10]

Childbearing is surrounded by values, beliefs, norms, that is, the social culture.[46] In this age, such cultural components as independent thinking, freedom of choice, individualism, consumerism, and self-realization are valued as part of modern life.[10] Modern values combined with increased consumerism, economic recession, and increased uncertainty, are changing the reproductive behavior patterns. Therefore, it can be said that delay in childbearing is the in deliberate consequence of a set of deliberate acts in the direction of self-realization.[68] The modern woman values the independence she can acquire from education, a secure job, and financial stability. For this reason, women prefer to postpone their maternal roles as long as possible by assuming the student or employee roles instead.[25]

One of the limitations of the present study was inaccessibility of some databases and the full texts of some of the articles. One of the strengths of this study was the broad range of literature obtained from different databases, so the findings can offer insights into subsequent research necessities.

Conclusion

The review of the studies revealed that delay in childbearing is affected by many different factors at micro and macro levels. It seems that making policies and interventions, such as strengthening the economic context, increasing social trust, powerfully protecting social welfare, creating employment opportunities, and supporting the family by using such strategies as creating family-friendly laws, while taking into consideration the national conditions and realities will reduce the insecurity perceived by spouses and will contribute to the proper planning of childbearing. At the micro level, improving self-efficacy, increasing the couples' reproductive knowledge, and modifying their attitude can help better decision-making.

Financial support and sponsorship

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflicts of interest

Nothing to declare.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for their support. This article was derived from a Ph.D. thesis in reproductive health with the project number 399719.

REFERENCES

- 1.Šprocha B, Tišliar P, Šídlo L. A cohort perspective on the fertility postponement transition and low fertility in Central Europe. Morav Geogr Rep. 2018;26:109–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leridon H, Slama R. The impact of a decline in fecundity and of pregnancy postponement on final number of children and demand for assisted reproduction technology. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1312–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt L, Sobotka T, Bentzen JG, Nyboe Andersen A. Demographic and medical consequences of the postponement of parenthood. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18:29–43. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Statistical Center of Iran According to the 2016 census total fertility rate of Iran reached to 2.01 between 2011 and 2016 [Persian] Available from: https://www.amar.org.ir/news/ID/5080 .

- 5.Bellieni C. The best age for pregnancy and undue pressures. Family Reprod Health. 2016;10:104–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behboudi-Gandevani S, Ziaei s, Farahani FK, Jasper M. The perspectives of Iranian women on delayed childbearing: A qualitative study. J Nurs Res. 2015;23:313–21. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0000000000000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adashi EY, Gutman R. Delayed childbearing as a growing, previously unrecognized contributor to the national plural birth excess. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:999–1006. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasić P. Fertility postponement between social context and biological reality: The case of Serbia. Sociológia-Slovak Sociological Rev. 2021;53:309–36. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreyenfeld M. Uncertainties in female employment careers and the postponement of parenthood in Germany. Eur Sociol Rev. 2010;26:351–66. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mills M, Rindfuss RR, McDonald P, te Velde E. Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:848–60. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neels K, Theunynck Z, Wood J. Economic recession and first births in Europe: Recession-induced postponement and recuperation of fertility in 14 European countries between 1970 and 2005. Int J Public Health. 2013;58:43–55. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0390-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sobotka T, Beaujouan É. Preventing Age Related Fertility Loss. Switzerland: Springer Publishing; 2018. Late Motherhood in Low-Fertility Countries: Reproductive Intentions, Trends and Consequences. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirshfeld-Cytron JE. Cost implications to society of delaying childbearing. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2013;8:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leader J, Bajwa A, Lanes A, Hua X, Rennicks White R, Rybak N, et al. The effect of very advanced maternal age on maternal and neonatal outcomes: A systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018;40:1208–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williamson LEA, Lawson KL. Young women's intentions to delay childbearing: A test of the theory of planned behaviour. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2015;33:205–13. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lean SC, Derricott H, Jones RL, Heazell AEP. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2017;12:e0186287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kariman N, Simbar M, Ahmadi F, Vedadhir AA. Socioeconomic and emotional predictors of decision making for timing motherhood among Iranian women in 2013. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e13629. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.13629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sauer MV. Reproduction at an advanced maternal age and maternal health. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:1136–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinheiro RL, Areia AL, Mota Pinto A, Donato H. Advanced maternal age: Adverse outcomes of pregnancy: A Meta-Analysis. Acta Med Port. 2019;32:219–26. doi: 10.20344/amp.11057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson JA, Tough S. Delayed childbearing. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34:80–93. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lebano A, Jamieson L. Childbearing in Italy and Spain: Postponement narratives. Popul Dev Rev. 2020;46:121–44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan SP, Taylor MG. Low fertility at the turn of the twenty-first century. Annu Rev Sociol. 2006;32:375–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brauner-Otto SR, Geist C. Uncertainty, doubts, and delays: Economic circumstances and childbearing expectations among emerging adults. J Fam Econ Issues. 2018;39:88–102. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safdari-Dehcheshmeh F, Noroozi M, Taleghani F, Memar S. Explaining the pattern of childbearing behaviors in couples: Protocol for a focused ethnographic study. J Educ Health Promot. 2022;11:71. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_579_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benzies K, Tough S, Tofflemire K, Frick C, Faber A, Newburn-Cook C. Factors influencing women's decisions about timing of motherhood. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:625–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williamson LE, Lawson KL, Downe PJ, Pierson RA. Informed reproductive decision-making: The impact of providing fertility information on fertility knowledge and intentions to delay childbearing. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36:400–5. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30585-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willett LL, Wellons MF, Hartig JR, Roenigk L, Panda M, Dearinger AT, et al. Do women residents delay childbearing due to perceived career threats? Acad Med. 2010;85:640–6. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2cb5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de la Rica S, Iza A. Career planning in Spain: Do fixed-term contracts delay marriage and parenthood? Rev Econ Househ. 2005;3:49–73. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bretherick KL, Fairbrother N, Avila L, Harbord SH, Robinson WP. Fertility and aging: Do reproductive-aged Canadian women know what they need to know? Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2162–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooke A, Mills TA, Lavender T. Advanced maternal age: Delayed childbearing is rarely a conscious choice a qualitative study of women's views and experiences. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:30–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tough S, Tofflemire K, Benzies K, Fraser-Lee N, Newburn-Cook C. Factors influencing childbearing decisions and knowledge of perinatal risks among Canadian men and women. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11:189–98. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kearney AL, White KM. Examining the psychosocial determinants of women's decisions to delay childbearing. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:1776–87. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooke A, Mills TA, Lavender T. Informed and uninformed decision making'—Women's reasoning, experiences and perceptions with regard to advanced maternal age and delayed childbearing: A meta-synthesis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:1317–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adachi T, Endo M, Ohashi K. Uninformed decision-making and regret about delaying childbearing decisions: A cross-sectional study. Nurs Open. 2020;7:1489–96. doi: 10.1002/nop2.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith DJ. Masculinity, money, and the postponement of parenthood in Nigeria. P Popul Dev Rev. 2020;46:101–20. doi: 10.1111/padr.12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tavares LP. Who delays childbearing? The associations between time to first birth, personality traits and education. Eur J Popul. 2016;32:575–97. doi: 10.1007/s10680-016-9393-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Billari FC, Philipov D, Testa MR. Attitudes, norms and perceived behavioural control: Explaining fertility intentions in Bulgaria. Eur J Popul. 2009;25:439. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nojomi M, Haghighi L, Bijari B, Rezvani L, Tabatabaee SK. Delayed childbearing: Pregnancy and maternal outcomes. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2010;8:80. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neels K, Murphy M, Ní Bhrolcháin M, Beaujouan É. Rising educational participation and the trend to later childbearing. Popul Dev Rev. 2017;43:667–93. doi: 10.1111/padr.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Billari FC, Liefbroer AC, Philipov D. The postponement of childbearing in Europe: Driving forces and implications. Vienna Yearb Popul Res. 2006:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ní Bhrolcháin M, Beaujouan É. Fertility postponement is largely due to rising educational enrolment. Popul Stud (Camb) 2012;66:311–27. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2012.697569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mac Dougall K, Beyene Y, Nachtigall RD. Age shock: Misperceptions of the impact of age on fertility before and after IVF in women who conceived after age 40. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:350–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gutiérrez-Domènech M. The impact of the labour market on the timing of marriage and births in Spain. J Popul Econ. 2008;21:83–110. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matysiak A, Vignoli D. Fertility and women's employment: A meta-analysis. Eur J Popul. 2008;24:363–84. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim HS. Female labour force participation and fertility in South Korea. Asian Popul Stud. 2014;10:252–73. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Behjati-Ardakani Z, Navabakhsh M, Hosseini SH. Sociological study on the transformation of fertility and childbearing concept in Iran. J Reprod Infertil. 2017;18:153–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Florian SM. Motherhood and employment among Whites, Hispanics, and Blacks: A life course approach. J Marriage Fam. 2018;80:134–49. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bering J, Pflibsen L, Eno C, Radhakrishnan P. Deferred personal life decisions of women physicians. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27:584–9. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.6315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schytt E, Nilsen A, Bernhardt E. Still childless at the age of 28 to 40 years: A cross-sectional study of Swedish women's and men's reproductive intentions. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2014;5:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roberts E, Metcalfe A, Jack M, Tough SC. Factors that influence the childbearing intentions of Canadian men. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1202–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sørensen NO, Marcussen S, Backhausen MG, Juhl M, Schmidt L, Tydén T, et al. Fertility awareness and attitudes towards parenthood among Danish university college students. Reprod Health. 2016;13:146. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0258-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gossett DR, Nayak S, Bhatt S, Bailey SC. What do healthy women know about the consequences of delayed childbearing? J Health Commun. 2013;18:118–28. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.825677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lassi ZS, Mansoor T, Salam RA, Das JK, Bhutta ZA. Essential pre-pregnancy and pregnancy interventions for improved maternal, newborn and child health. Reprod Health. 2014;11(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Molina-García L, Hidalgo-Ruiz M, Cocera-Ruíz EM, Conde-Puertas E, Delgado-Rodríguez M, Martínez-Galiano JM. The delay of motherhood: Reasons, determinants, time used to achieve pregnancy, and maternal anxiety level. PloS One. 2019:14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Testa MR. Childbearing preferences and family issues in Europe: Evidence from the Eurobarometer 2006 survey. Vienna Yearb Popul Res. 2007:357–79. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kotte M, Ludwig V. Intergenerational transmission of fertility intentions and behaviour in Germany: The role of contagion. Vienna Yearb Popul Res. 2011;9:207–26. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Balbo N, Mills M. The effects of social capital and social pressure on the intention to have a second or third child in France, Germany, and Bulgaria, 2004–05. Popul Stud (Camb) 2011;65:335–51. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2011.579148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rossier C, Bernardi L. Social interaction effects on fertility: Intentions and behaviors. Eur J Popul. 2009;25:467–85. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adachi T, Endo M, Ohashi K. Regret over the delay in childbearing decision negatively associates with life satisfaction among Japanese women and men seeking fertility treatment: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:886. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09025-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown LM. The relationship between motherhood and professional advancement: Perceptions versus reality. Employ Relat. 2010;32:470–494. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Metcalfe A, Vekved M, Tough SC. Educational attainment, perception of workplace support and its influence on timing of childbearing for Canadian women: A cross-sectional study. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:1675–82. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fostik A. COVID-19 and fertility in Canada: A commentary. Can Stud Popul. 2021;48:217–24. doi: 10.1007/s42650-021-00054-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de la Croix D, Pommeret A. Childbearing postponement, its option value, and the biological clock. J Econ Theory. 2021:193. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kariman N, Simbar M, Ahmadi F, Vedadhir AA. Concerns about one's own future or securing child's future: Paradox of childbearing decision making. Health. 2014;6:1019–29. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Timæus IM, Moultrie TA. Pathways to low fertility: 50 years of limitation, curtailment, and postponement of childbearing. Demography. 2020;57:267–96. doi: 10.1007/s13524-019-00848-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amerian M, Mohammadi S, Faghani Aghoozi M, Malari M. Related determinants of decision-making in the first childbearing of couples: A narrative review. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J. 2019;9:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vignoli D, Tocchioni V, Mattei A. The impact of job uncertainty on first-birth postponement. Adv Life Course Res. 2020;45:100308. doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2019.100308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mauceri S, Valentini A. The European delay in transition to parenthood: The Italian case. Int Rev Sociol. 2010;20:111–42. [Google Scholar]