Background:

Alzheimer disease (AD) poses a major public health crisis, especially among African Americans (AAs) who are up to 3 times more likely to develop AD compared with non-Hispanic Whites. Moreover, cardiovascular risk factors represent a precursor to cognitive decline, which contributes to racial/ethnic disparities seen within AD. Despite these disparities, AAs are underrepresented in neurovascular research. The purpose of this qualitative virtual photovoice project is to explore how older Midwestern AAs perceive neurovascular clinical trials.

Methods:

Five photovoice sessions were held virtually over a 3-month period. Participants took photos each week that captured the salient features of their environment that described their perceptions and experiences related to neurovascular clinical trials. Structured discussion using the SHOWED method was used to generate new understandings about the perspectives and experiences in neurovascular clinical trials. Data was analyzed using strategies in participatory visual research.

Results:

A total of 10 AAs aged 55 years and older participated and a total of 6 themes emerged from the photovoice group discussions.

Conclusion:

Findings from this study inform the development of culturally appropriate research protocols and effective recruitment strategies to enhance participation among older AAs in neurovascular clinical trials.

Key Words: photovoice, neurovascular, African Americans, clinical trials

Of the 5.8 million Americans affected with Alzheimer disease (AD) and related dementias,1 current evidence suggests that African Americans (AAs) are disproportionately affected by AD and are 3 times more likely to develop dementia compared with their White counterparts.2–5 Moreover, it is well-documented that cardiovascular (CV) risk factors represent a precursor to cognitive decline among older adults, which contributes to racial/ethnic disparities seen within AD. Specifically, elevated blood pressure, obesity, and diabetes have been consistently reported as associated with cognitive impairments in the domains of memory and executive function.6,7 Despite these disparities, AA are underrepresented in clinical research. The Food and Drug Administration reported that AA represent 12% of the total US population, but only 5% in clinical research participation.8 Underrepresentation of AA in neurovascular-related clinical research not only limits generalizability of research findings but inadvertently results in a degree of uncertainty in relation to risks for dementia within the AA community.9 This phenomenon demonstrates a need for increased participation among older AA in neurovascular clinical research to identify potential unique differences in risk, prevention, and treatment outcomes.

Previous research has identified lack of awareness about clinical research studies, mistrust, fear of experimentation, and side effects, and belief that research would not benefit the AA community as barriers to participate in clinical trials.10–15 Facilitators identified include altruism, compensation, and access to care.16,17 In addition, previous research has noted that racially and ethnically minoritized communities have indicated that finding a cure for disease and helping others as perceived facilitators in participating in clinical trials.15,18 Few studies have examined both barriers and facilitators for participation in clinical research related to AD among AA.19–22 Of these studies which used focus groups, few asked participants to provide recommendations to enhance AA participation in research. Thus, researchers have limited understanding regarding perspectives of neurovascular clinical trials and of culturally salient methods to adequately increase participation among AA in neurovascular clinical research. Moreover, previous research indicated that AAs are comfortable participating in observational research trials, but are reluctant to participate in invasive clinical trial procedures (ie, lumbar puncture) and fear the unknown of adverse effects related to drug treatments.22 Although, observational studies are useful in capturing outcomes in regular clinical practice settings23 these trials are not designed to prevent or treat diseases such as AD. Therefore, to fully address the disproportionate impact of AD among older AAs there is a need to identify ways to enhance participation to ensure that advancement treatments are generalizable to all.

Photovoice is a participatory action-oriented research method in which community members take photographs of meaningful elements in their environment to communicate issues of concern and to influence social change.24 Photographs are used to (1) stimulate empowering group discussions, (2) create a platform to give community members an opportunity to share their unique narratives, and (3) to identify shared needs of a particular topic.24 Photovoice has been found to be an effective tool for extracting data that identifies both the needs and perceptions of underserved communities in addition to empowering individuals to engage in their personal health.25,26

Photovoice method has been used among older adults, which has provided a novel approach to engage with this population.27,28 Photovoice is increasingly being used in health-related research among older adults such as diabetes and CV disease but has not been widely described in the AD literature.29,30 Given the high prevalence of CV-related risk factors of AD in the AA community coupled with the importance of AA perception and participation in invasive neurovascular clinical trials, using photovoice to understand perspective may be useful in developing culturally tailored research protocols and effective recruitment strategies for AAs. Therefore, the purpose of this qualitative virtual photovoice study is to explore how older Midwestern AA perceive neurovascular clinical trials.

METHODS

Approval to conduct the study was obtained by the University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB #00147773). This was a noninterventional qualitative study that used photovoice methodology to understand cultural elements relevant to participation in neurovascular interventional clinical trials to inform the design and advance diversity in future randomized controlled neurovascular clinical trials.

Participants and Recruitment

We used purposive sampling to recruit 10 participants, which is congruent with photovoice best practices.25 Specifically, the Outreach and Recruitment Core staff at the University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center contacted potential participants through existing registries via recruitment letter, email, and phone. Individuals interested in participating in the study contacted research staff by phone and completed a brief telephone screening to verify eligibility. Inclusion criteria for eligible participants included: (1) self-identifying as AA or Black, (2) aged 55 years and older, (3) English speaking, (4) cognitively normal with an AD8 <2, (5) 1 or more CV risk factors, (6) has a smartphone, and (7) previously have participated in observational clinical trials. Participants who were cognitively impaired with an AD8 ≥2, did not own a smartphone, or had previously participated in an interventional clinical AD and related dementias trials were not eligible to participate in.

Photovoice Group Process

Six photovoice sessions (Table 1) were conducted between February 2022 and March 2022 and included a cohort of 10 participants. All photovoice sessions were facilitated by an AA facilitator and a research assistant (RA). The AA facilitator and RA received facilitation training that involved the use of a photovoice facilitator’s toolkit31 that provided detailed information about elements of a photovoice project, ethical considerations, and a step-by-step process to executing a photovoice project as a facilitator. In addition, the AA facilitator and RA completed a human subject protection training course as part of their training. The facilitator and RA were provided with documentation including photovoice techniques and procedures to support their efforts through the study. The trained facilitator identified as AA and was selected to facilitate due to her education in addition to her prior experience moderating photovoice and focus group discussions in the AA community.

TABLE 1.

Photovoice Weekly Discussions

| Session 1 | Introduction to photovoice (orientation, description of the project, SHOWED method) |

| Session 2 | Photography (taking good and effective photos, mechanics of working smartphone camera) |

| Session 3 | Photographs of perception of clinical trials |

| Session 4 | Photographs of experience of participating in observational studies |

| Session 5 | Photographs of recommendations for neurovascular clinical trial design |

| Session 6 | Data confirmation session (member checking) |

Each photovoice session lasted 60 minutes and all session were held virtually using the Zoom platform. Before starting the photovoice discussions sessions, participants attended two 60-minute orientation sessions (session 1 and session 2) held via Zoom to learn about the goals of the project, study procedure, and to discuss how to take photos safely and responsibly.

After orientation participants were instructed to use their personal smartphones to take 2 photos (6 photos total) that captured salient features of their environment in relation to the topic questions during sessions 3 to 5. In addition, participants were instructed to submit a reflection form with their 2 photos that described the photos and how the photo reflected the experience/perception related to the research question. Photos and reflection forms submitted by each participant via email to the principal investigator (PI) who stored all of the photos and reflection forms onto secure drive.

During sessions 3 to 5, each participant discussed their photos taken related to session topic (Table 1). Through discussion and voting participants selected 2 photos within the group that trigged critical reflection for in-depth discussion. Facilitators led the group though a structured discussion using the SHOWED method that consists of 5 questions used to describe photos: What do you see here? What is really happening here? How does this relate to our lives? Why does this problem concern exist? What can we do about it?26 The SHOWED method in the present study was used generate new understandings about perspectives and experiences in neurovascular clinical trials.

Upon completion of the data analysis (see below), we conducted a data-checking discussion session (session 6) to ensure that findings were congruent with the community’s interpretation, resulting in a final thematic consensus.

After the data confirmation session, all participants completed a 7-item online satisfaction of photovoice study survey that was individually emailed to them through REDCap.

Data Analysis

Previous researcher has indicated the importance of researchers respecting and accounting for their own interpretations and participations interpretations of a phenomenon in addition to recognizing participants photos and photo descriptions as meaningful data during the data analysis process.32,33 Data was analyzed is this study using strategies in participatory visual research.34–36 Because this practice limits distorting participants interpretations of the phenomenon in addition to generating potential theoretical explanations of the phenomenon. Specifically, the analysis took place in 4 stages, including a photograph analysis based on the PI’s interpretations, a photograph analysis based on the participants’ interpretations, a cross-comparison, and theorization. Additional data analysis details can be found in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Stages to Photovoice Data Analysis

| Stage 1: Photograph analysis—PI interpretation | PI categorized the photos and examined each category, then recategorized them and reexamined the categories, until saturation was reached. Then a preliminary explanation was developed from the perspective of the PI |

| Stage 2: Photograph analysis—Participant interpretation | PI determined if there were alternative explanations for photos based on participants interpretations. The PI examined narratives of the photos and categorized and recategorized the photos and narratives into themes until saturation was reached |

| Stage 3: Cross-comparison | PI compared the 2 sets of results (ie, comparing photos with photos, narratives with narratives, photos and narratives with categories, categories with categories, themes with themes between the sets of results) and created a dialogue between the PI’s interpretation and participants to develop an integrative explanation of the phenomenon |

| Stage 4: Theorization | PI identified the relationship between themes developed during cross-comparison to generate both visual and narrative representation and explanations of the phenomenon |

PI indicates principal investigator.

RESULTS

A total of 10 older AAs (5 women, 5 men) participated in the study. Most participants were between the ages of 65 to 74 (70%); married (60%); retired (60%); with an education level equivalent or higher to a bachelor’s degree (90%); and religiously identifying as a Christian (80%). Most participants indicated that they currently have high blood pressure (70%), high cholesterol (60%), and half of the participants (50%) indicated they had a family history of dementia.

Themes

A total of 6 themes emerged from the focus group discussions. Themes had generally positive, negative, or mixed experiences. The results are summarized according to the major themes and subthemes expressed across all 7 focus group discussions.

Theme 1: The Good, Bad, and the Ugly of Clinical Trials

Many participants perceived clinical trials to be beneficial when done ethically which can lead to advancements in health care and can improve the quality of life for the AA community. In addition, several participants indicated that they believed that AA community members appreciate being compensated for their time when participating in studies, which was viewed as a “good” incentive.

Several participants voiced various aspects clinical trials to be “bad” such as the perception of the time commitment required to participate which was viewed as a barrier. Other aspects of clinical trials that were perceived as “bad” included fears due to negative past experiences with health care professionals in general and the perception that research paperwork to participate in a clinical trial being cumbersome to the community which deters people from wanting to participate. Many participants voiced the importance of incorporating visual information when possible because it was perceived to be an effective tool for communicating health information.

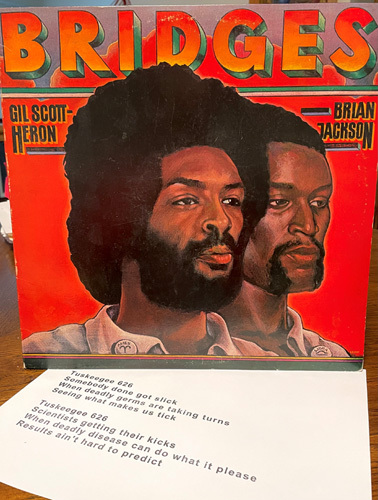

Most participants discussed mistreatment and distrust due to the unethical history of clinical trials in this country. Specifically, several participants mentioned the history of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment and Henrietta Lacks which they believed let to internal resistance towards participating in clinical trials. To address the “ugly” participants voiced that researchers need to focus on methods that will bridge trust between research institutions and the community. Participants indicated that trust comes about in part through sharing accurate information about the history of research (ie, indicating that people were not injected with syphilis in the Tuskegee trial instead treatment was withheld), transparency of all aspects of the research process and expected outcomes, and by communicating findings of clinical trials to the AA community so they have an understanding of how their participation was used to support advancements in science (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

“In 1977, the song Tuskegee 626, exactly 33 and 1/3 seconds-long, shaped my perceptions of clinical trials as a young Black man. I memorized the song, read about the Tuskegee syphilis experiments, and internalized the general sense of distrust. In this image, I am trying to communicate the historical basis for resistance and barriers to African American participation in clinical trials.”

Theme 2: Guinea Pigs in Clinical Trials

Some AA perceived clinical trials as feeling like being a guinea pig, meaning having no voice when it comes to being a part of research and are unaware of what could happen to them by participating in trials; especially pharmaceutical trials. There was also a perception that research institutions pry on vulnerable populations such as the AA community. Due to this belief, many people in the AA community are fearful of being misused and abused in clinical trials.

Theme 3: Informative and Enlightening

A number of participants indicated that their experience participating in an observational study was positive due to the professionalism of the research team (ie, being organized, transparent about the trial by providing specific details) which made them feel like there was not a hidden agenda. Also, with respect to their experience, there was a belief that everyone has an opportunity to be treated equally participating in observational studies. What some participants valued during their experience in an observational study was the educational resources provided to further enhance their understanding of dementia and dementia prevention. To further enhance the entire research experience community members emphasized the importance of use of lay language to describe clinical terms in conversation and in documentation. Last, most participants indicated the importance of researchers emphasizing to participants how their participation, even in an observational trial can impact the health and well-being of the AA community in the future (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

“I dealt out this random game of Texas Hold-Em Poker. Each hand of two cards is unique, but is subject to the same set of variables introduced by “the dealer” to build the best hand of five cards. With one more variable (the River card) yet to be introduced, each participant can evaluate strengths, calculate probabilities, assess risks and make a decision on completing the hand. In real life, each study participant comes to the table with a unique hand of experiences and qualities. Within the parameters of an Observational study, “the dealer” can analyze the response behavior and decisions of the participants in order to predict outcomes.”

Theme 4: Unfairness of Standardized Testing

Many participants indicated that everyone has a unique background, and it is important to be mindful and embrace various dialects and communication styles when researchers are performing tests. There was a strong belief among participants that research instruments and standardized tests used in observational studies have demonstrated value of some dialects over others. Many participants strongly believed research measurements used may not be an accurate or fair when having cognition assessed. In addition, many participants believed that standardized tests need to be revised and tailored towards AA cultural dialects and that the research team conducting testing needs to have better awareness of varies dialects to properly assess cognition.

Theme 5: Connection With the Community

Participants voiced the importance of connection with the community through outreach, communication, and diversity among the research team to enhance participation among AA in neurovascular clinical trials. Many participants indicated the importance of developing unique and inviting ways to reach the community in addition to sharing resources with the community instead of only talking about research to the community. Several participants indicated that outreach needs to be designed in a manner that reduces burden of access for families which demonstrates caring to the AA community which can lead to a greater willingness to participate in clinical trials. Last, several participants indicated that connecting with the community requires diversity among the entire research team (ie, recruiters, RAs, PIs) in which the research team as a whole reflects the AA community. Several participants believed seeing research personal who looked like them would help aid in developing trust within the community and further advancing research participation among older AA (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

“To engage people of diversity, it is imperative (in my opinion), to have the research staff including the doctors look like the participants. This will aid in trust being established. Too often we are asked to participate in studies, and we do not see any “like” us in the research technician/doctor role.”

Theme 6: Overcoming Opposition Before Starting a Clinical Trial

Most participants indicated that to enhance participation among older AA in clinical trials it was important to overcome opposition by researchers acknowledging concerns related to clinical trials that the AA community may have such as risks of participating, fear of the unknown, trust of researchers, commercialism, and long-term goals of the research. Participants also indicated that researchers need to be the forefront of change and be prepared to provide clear and concise information to influence change that can help eliminate concerns and doubt related to research that the community has. This can be done by presenting information a way that thoroughly explains the different types of clinical trials (ie, pharmaceutical vs. nonpharmaceutical trials), incorporating concise information of how clinical trials can not only support them, but also benefit their families, and community, and lastly showing compassion to help ease the minds of the community. Last, as a mechanism to overcome opposition most participants indicated the importance of collaborating with current participants (ie, community champions) who can leverage their platform and connections to share about their experience participating in clinical trials. Many participants believed using the mechanism could help create a snowball effect for research interest and recruitment within neurovascular clinical trials (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

“This is photo of myself and my wife making a presentation at our church during our pastor’s anniversary service. With respect to the research question, this picture depicts a method that can be used to increase diversity for clinical trials by getting support from participants to share their clinical trial experiences with the Afro-American community, especially in church settings.”

Poststudy Survey

Overall, most participants rated their research experience in the photovoice study as excellent or very good (90%) and indicated that they were very interested in participating in future neurovascular clinical trials (77.8%).

DISCUSSION

This photovoice study provides insight from older AAs by exploring how older Midwestern AA perceive neurovascular clinical trials and the cultural needs to participate in neurovascular clinical trials. Our study revealed 6 themes: (1) The good, bad, and the ugly of clinical trials, (2) Guinea pigs in clinical trials, (3) Informative and enlightening, (4) Unfairness of standardized testing, (5) Connection with the community, and (6) Overcoming opposition before starting a clinical trial. The concept of trust is weaved throughout all 6 themes of this study.

This photovoice study is a good addition to the current literature on clinical trial participation as it provides insights into culturally tailored methods to enhance participation in neurovascular clinical trials among older Midwestern AA that were not previously captured in the literature. Although past research recognizes barriers and facilitators to participation in clinical trials among racially and ethnically minoritized communities,11,16 few have focused on examining barriers and facilitators in AD-related trials.22 Of those studies, findings indicated mistrust, fear of the unknown, and transportation were perceived as barriers, which is congruent with our findings in which participants captured distrust due to the history of clinical trials, fear of side effects from pharmaceutical clinical trials, and reducing the burden of access. In addition, our findings highlight the imperative role trust holds in contributing to the recruitment and design of neurovascular clinical trials to enhance diversity, which is congruent with previous literature.22 Trust is a fundamental construct that has been defined in terms of consistency, compassion, communication, and competency.37 This photovoice study gave context to the 4 components of trust in relation to enhancing diversity in neurovascular trials in the following manner: (1) sharing resources with the community through consistent outreach, which demonstrates a sense of caring to older AA, (2) showing compassion by displaying vulnerability to help ease minds of community members due to the unethical history of clinical trials and its impact on the AA community, (3) openly communicating research findings to participants in which sharing research results demonstrates that the community is not being exploited, (4) having communication competence to adequately assess cognitive health and the ability to communicate with the AA community in a culturally appropriate manner.

This study suggests that photovoice serves as a vehicle for comprehending needs and concerns related to neurovascular clinical trials in the AA community. Specifically, it provides insight regarding refining invasive procedures which should be explored in future research. We propose that photovoice be considered as a tool used by aging researchers to build equity into clinical trial design. Specifically, using photovoice to gain diverse communities’ input of novel approaches that can give aging researchers an opportunity to enhance neurovascular quantitative assessment data with grassroot visuals and narrative data. In addition, we recommend use of photovoice to enhance aging researchers’ skills as advocates by equipping them with narrative-driven intervention development and health policy recommendations to support diversity in clinical trials. Last, we recommend that aging researchers use photovoice as a dissemination tool to educate diverse community members about clinical trials within the parameters of its emphasis on lifestyle and treatment trials. This study had limitations including small sample size and use of purposive sampling method which limits generalizability of study findings. Since the photovoice study was conducted virtually, the virtual format removed the intimacy seen in traditional in person photovoice sessions which may have impacted comfort in sharing one’s experience and perspectives as related to the research topic. Also, due to sole use of a virtual format for this study those who may not have had internet access were not included in our study. Although the virtual format removed the intimacy element within the sessions, the virtual aspect eliminated transportation barrier for older adults commonly noted in previous literature.38 Using the Zoom platform gave an opportunity of community members to participate in which distance or transportation may have been barrier. Future studies should build on this photovoice study using traditional social science approaches (ie, focus groups, individual interviews) to both refine and validate this study findings.

CONCLUSIONS

The application of photovoice is based on the notion that older AA community members participate in capturing photos that shape their reality to foster change. Our findings from the emerged themes in this study highlight the importance of researchers cultivating trust as well as the valuable role trust plays in enhancing recruitment and participation among older AA in neurovascular clinical trials. Diversity in neurovascular clinical trials is both morally and scientifically imperative. Therefore, it is a commitment from researchers to cultivate trust and engage community members throughout the research process to support both development and advancements in reducing health disparities seen in neurovascular research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to acknowledge the participants in this study as well as support from Dr. Azure Thompson and the Leo and Anne Albert Charitable Trust.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Health grants 5R25HL105446-11, 1K01AG072034, and 1P30AG072973.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Ashley R. Shaw, Email: ashaw10@kumc.edu.

Saria Lofton, Email: slofto4@uic.edu.

Eric D. Vidoni, Email: evidoni@kumc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:321–387. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alzheimer’s Association, Thies W, Bleiler L. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:208–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rajan KB, Weuve J, Barnes LL, et al. Prevalence and incidence of clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease dementia from 1994 to 2012 in a population study. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Potter GG, Plassman BL, Burke JR, et al. Cognitive performance and informant reports in the diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia in African Americans and Whites. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:445–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gurland BJ, Wilder DE, Lantigua R, et al. Rates of dementia in three ethnoracial groups. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14:481–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tsivgoulis G, Alexandrov AV, Wadley VG, et al. Association of higher diastolic blood pressure levels with cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2009;73:589–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johansen MC, Langton-Frost N, Gottesman RF. The role of cardiovascular disease in cognitive impairment. Curr Geriatr Rep. 2020;9:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8. The Society for Women’s Health Research. United States Food and Drug Administration Office of Women’s Health. Dialogues on diversifying clinical trials; successful strategies for engaging women and minoriteis in clincial trials. 2011. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/84982/download .

- 9. Hughes TB, Varma VR, Pettigrew C, et al. African Americans and clinical research: evidence concerning barriers and facilitators to participation and recruitment recommendations. Gerontologist. 2017;57:348–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brown M, Moyer A. Predictors of awareness of clinical trials and feelings about the use of medical information for research in a nationally representative US sample. Ethn Health. 2010;15:223–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e16–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Byrd GS, Edwards CL, Kelkar VA, et al. Recruiting intergenerational African American males for biomedical research Studies: a major research challenge. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:480–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2458–2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Owens OL, Jackson DD, Thomas TL, et al. African American men’s and women’s perceptions of clinical trials research: focusing on prostate cancer among a high-risk population in the South. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24:1784–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Calderón JL, Baker RS, Fabrega H, et al. An ethno-medical perspective on research participation: a qualitative pilot study. MedGenMed. 2006;8:23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Factors that influence African-Americans’ willingness to participate in medical research studies. Cancer. 2001;1(suppl):233–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Byrne MM, Tannenbaum SL, Glück S, et al. Participation in cancer clinical trials: why are patients not participating. Med Decis Making. 2014;34:116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schnieders T, Danner DD, McGuire C, et al. Incentives and barriers to research participation and brain donation among African Americans. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28:485–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bonner GJ, Miles TP. Participation of African Americans in clinical research. Neuroepidemiology. 1997;16:281–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Darnell KR, McGuire C, Danner DD. African American participation in Alzheimer’s disease research that includes brain donation. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2011;26:469–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lambe S, Cantwell N, Islam F, et al. Perceptions, knowledge, incentives, and barriers of brain donation among African American elders enrolled in an Alzheimer’s research program. Gerontologist. 2011;51:28–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Williams MM, Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, et al. Barriers and facilitators of African American participation in Alzheimer disease biomarker research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(suppl):S24–S29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Onder G. The advantages and limitations of observational studies. G Ital Cardiol (Rome). 2013;14(suppl 1):35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:369–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cohen D, Crabtree B. Qualitative research guidelines project. 2006.

- 26. Gant LM, Shimshock K, Allen-Meares P, et al. Effects of photovoice: civic engagement among older youth in urban communities. J Community Pract. 2009;17:358–376. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bryanton O, Weeks L, Townsend E, et al. The utilization and adaption of photovoice with rural women aged 85 and older. Int J Qual Methods. 2019;18:1609406919883450. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Novek S, Morris-Oswald T, Menec V. Using photovoice with older adults: some methodological strengths and issues. Ageing Soc. 2012;32:451–470. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yankeelov PA, Faul AC, D’Ambrosio JG, et al. “Another day in paradise” a photovoice journey of rural older adults living with diabetes. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;34:199–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fitzpatrick AL, Steinman LE, Tu S-P, et al. Using photovoice to understand cardiovascular health awareness in Asian elders. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Apaza V, DeSantis P, DeLeon A, et al. Facilitator’s Toolkit for Photovoice Project. United for Prevention in Passaic County and the William Paterson University Department of Public Health. 2018. Accessed August 1, 2022. 2018. https://www.gocolumbia.edu/institutional_research/photovoice_page_documents/Facilitators_Toolkit.pdf .

- 32. Ciolan L, Manasia L. Reframing photovoice to boost its potential for learning research. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16:1609406917702909. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Oliffe JL, Bottorff JL, Kelly M, et al. Analyzing participant produced photographs from an ethnographic study of fatherhood and smoking. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31:529–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Glaw X, Kable A, Hazelton M. Visual methodologies in qualitative research: autophotography and photo elicitation applied to mental health research. 2017.

- 35. Plunkett R, Leipert BD, Ray SL. Unspoken phenomena: using the photovoice method to enrich phenomenological inquiry. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oliffe JL, Bottorff JL, Kelly M, et al. Analyzing participant produced photographs from an ethnographic study of fatherhood and smoking. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37. Vodicka D. The Four Elements of Trust. Principal Leadership. 2006;7(3):27–30.

- 38. Rigatti M, DeGurian AA, Albert SM. “Getting There”: Transportation as a barrier to research participation among older adults. J Appl Gerontol. 2022;41:1321–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]