Abstract

Acute respiratory infections block the bronchial and/or nasal systems’ airways. These infections may present in a variety of ways, from minor symptoms like the common cold to more serious illnesses like pneumonia or lung collapse. Acute respiratory infections cause over 1.3 million infant deaths under the age of 5 each year throughout the world. Among all illnesses, respiratory infections make for 6% of the worldwide disease burden. We aimed to examine the admissions related to acute upper respiratory infections admissions in England and Wales for the period between April 1999 and April 2020. This was an ecological study using publicly available data extracted from the Hospital Episode Statistics database in England, and the Patient Episode Database for Wales for the period between April 1999 and April 2020. The acute upper respiratory infections-related hospital admissions were identified using the Tenth Revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 5th Edition (used by National Health Service [NHS] to classify diseases and other health conditions) (J00–J06). The total annual number of admissions for various reasons increased by 1.09-fold (from 92,442 in 1999 to 193,236 in 2020), expressing an increase in hospital admission rate of 82.5% (from 177.30 [95% confidence interval {CI}: 176.15–178.44] in 1999 to 323.57 [95%CI: 322.13–325.01] in 2020 per 100,000 persons, P < .01). The most common causes were acute tonsillitis and acute upper respiratory infections of multiple and unspecified sites, which accounted for 43.1% and 39.4%, respectively. Hospital admissions rate due to acute upper respiratory infections increased sharply during the study period. The rates of hospital admissions were higher among those in the age group below 15 and 75 years and above for the majority of respiratory infections, with a higher incidence in females.

Keywords: admissions, England, hospitalization, infections, respiratory, upper, wales

1. Introduction

Infections of the lower or upper respiratory tract that obstruct the airway at the bronchial system and\or nasal are referred to as acute respiratory infections. These infections can manifest in diverse ways, ranging from mild symptoms such as the common cold to more severe conditions like lung collapse or pneumonia.[1] Acute respiratory infections involve viruses and bacteria as their causative agents, but 90% of these infections are recognized to be caused by viruses.[2,3] Numerous modifiable risk factors, such as socioeconomic, environmental, dietary, and demographic factors, are associated with acute respiratory infections.[4]

Acute respiratory infections are the main reason for morbidity and mortality among children below 5 years and present a significant burden on the healthcare system.[5,6] Worldwide, acute respiratory infections account for approximately 1.3 million deaths annually among children below 5 years.[7] Respiratory infections account for 6% of the entire global burden of diseases, according to the World Health Organization estimation, which is higher than the burdens of ischemic heart disease, HIV infection, cancer, malaria, or diarrheal disorder.[8]

Acute respiratory infections place a significant financial strain on society regarding visits to healthcare providers, school care, missed work, treatments, day care, and visits to doctors.[9] Due to the direct impact on tissue oxygenation that acute respiratory infections have on children, which leads to complications and worse consequences like raised death and morbidity, these infections frequently qualify as medical emergencies.[10] Annually, more than 12 million children under 5 years old are hospitalized because of acute respiratory infections.[11]

The preponderance of respiratory deaths is related to acute lower respiratory infections, but the most common type of acute respiratory infection is upper respiratory tract infections.[12,13] In England and Wales, acute upper respiratory infections accounted for 11.3% of the total hospital admission due to diseases of the respiratory system, and the rate of hospitalization due to acute upper respiratory infections increased by 79.2% between 1999 and 2019.[14] Thus, this study aims to examine the admissions related to acute upper respiratory infections admissions in England and Wales.

2. Methods

2.1. Study sources and the population

This was an ecological study using publicly available data extracted from the Hospital Episode Statistics database in England and the Patient Episode Database for Wales for the period between April 1999 and April 2020.[15,16] Hospital admission data are subdivided into 4 categories; “below 15 years,” “15–59 years,” “60–74 years,” and “75 years and over.” We identified acute upper respiratory infections-related hospital admissions as the primary cause of admission using the Tenth Revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 5th Edition (used by National Health Service [NHS] to classify diseases and other health conditions) (J00–J06).[17]

2.2. Statistical analysis

Hospital admission rates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the finished consultant episodes divided by the mid-year population. We used the chi-squared test to assess the difference between the hospital admission rates between 1999 and 2020. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

2.3. Ethical approval

This study used de-identified data and was considered exempt from human protection oversight by the institutional review board. This study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Results

The total annual number of admissions for various reasons increased by 1.09-fold (from 92,442 in 1999 to 193,236 in 2020), expressing an increase in hospital admission rate of 82.5% (from 177.30 [95%CI: 176.15–178.44] in 1999 to 323.57 [95%CI: 322.13–325.01] in 2020 per 100,000 persons, P < .01).

The most common causes were acute tonsillitis and acute upper respiratory infections of multiple and unspecified sites, which accounted for 43.1% and 39.4%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Percentage of number of admission from total number of admissions per ICD code.

| ICD code | Description | Percentage from total number of admissions |

|---|---|---|

| J00 | “Acute nasopharyngitis [common cold]” | 1.2% |

| J01 | “Acute sinusitis” | 1.0% |

| J02 | “Acute pharyngitis” | 4.6% |

| J03 | “Acute tonsillitis” | 43.1% |

| J04 | “Acute laryngitis and tracheitis” | 0.9% |

| J05 | “Acute obstructive laryngitis [croup] and epiglottitis” | 9.8% |

| J06 | “Acute upper respiratory infections of multiple and unspecified sites” | 39.4% |

ICD = Tenth Revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10).

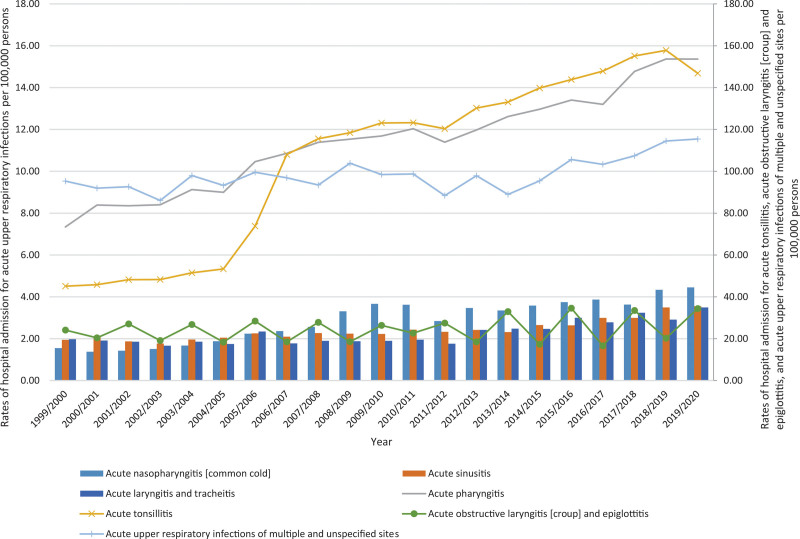

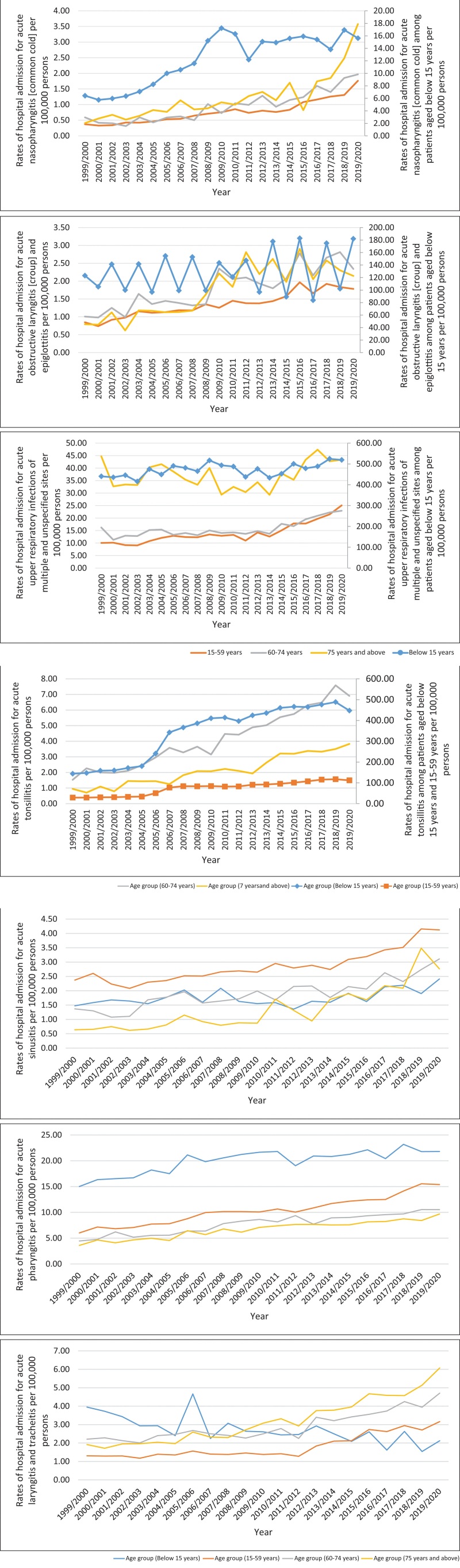

During the study duration, a tremendous increase in hospital admissions rate was seen in acute tonsillitis, acute nasopharyngitis [common cold], and acute pharyngitis by 2.26-fold, 1.87-fold, and 1.09-fold. Furthermore, hospital admissions rates for acute sinusitis, acute laryngitis and tracheitis, acute obstructive laryngitis (croup) and epiglottitis, and acute upper respiratory infections of multiple and unspecified sites were increased by 82.8%, 77.2%, 42.6%, and 21.2%, respectively (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

Figure 1.

Rates of hospital admission between 1999 and 2020.

Table 2.

Percentage change in the hospital admission rates.

| Diseases | Rate of diseases in 1999 per 100,000 persons (95%CI) | Rate of diseases in 2020 per 100,000 persons (95%CI) | Percentage change from 1999 to 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Acute nasopharyngitis [common cold]” | 1.55 (1.44–1.66) |

4.45 (4.28–4.62) |

187.1% |

| “Acute sinusitis” | 1.94 (1.83–2.06) |

3.55 (3.40–3.71) |

82.8% |

| “Acute pharyngitis” | 7.34 (7.11–7.57) |

15.36 (15.05–15.67) |

109.2% |

| “Acute tonsillitis” | 45.10 (44.53–45.68) |

146.8 (145.91–147.85) |

225.7% |

| “Acute laryngitis and tracheitis” | 1.97 (1.85–2.09) |

3.49 (3.34–3.64) |

77.2% |

| “Acute obstructive laryngitis [croup] and epiglottitis” | 24.11 (23.69–24.53) |

34.38 (33.91–34.85) |

42.6% |

| “Acute upper respiratory infections of multiple and unspecified sites” | 95.28 (94.44–96.11) |

115.45 (114.59–116.31) |

21.2% |

CI = confidence interval.

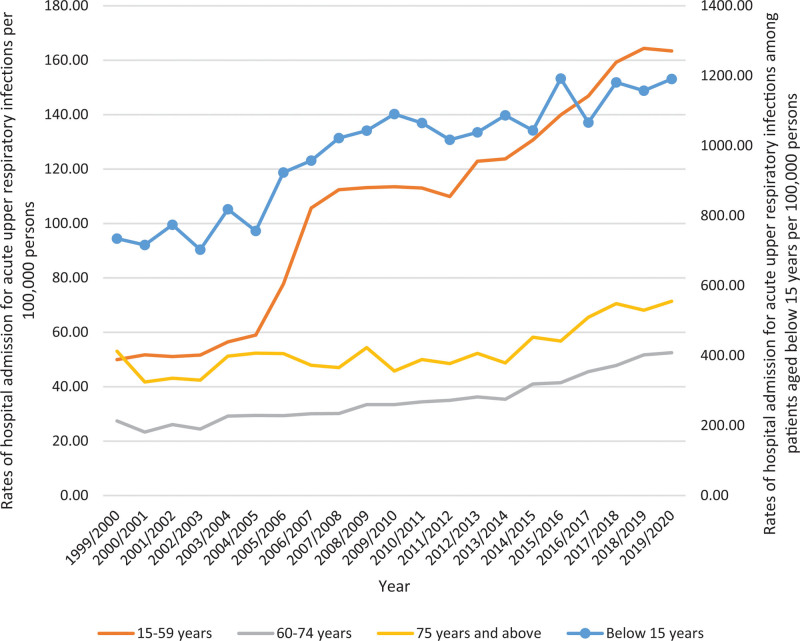

Concerning age group differences for acute upper respiratory infections hospital admission, the age group below 15 years accounted for 70.8% of the total number of acute upper respiratory infections hospital admissions, followed by the age group 15 to 59 years with 25.5%, the age group 60 to 74 years with 2.1%, and then the age group 75 years and above with 1.7%. Rates of hospital admission for acute upper respiratory infections among patients aged below 15 years increased by 62.1% (from 734.50 [95%CI: 729.18–739.82] in 1999 to 1190.91 [95%CI: 1184.42–1197.40] in 2020 per 100,000 persons). Rates of hospital admission for acute upper respiratory infections among patients aged 15 to 59 years increased by 2.27-fold (from 49.94 [95%CI: 49.16–50.72] in 1999 to 163.44 [95%CI: 162.09–164.79] in 2020 per 100,000 persons). Rates of hospital admission for acute upper respiratory infections among patients aged 60 to 74 years increased by 91.6% (from 27.39 [95%CI: 26.16–28.63] in 1999 to 52.49 [95%CI: 51.02–53.96] in 2020 per 100,000 persons). Rates of hospital admission for acute upper respiratory infections among patients aged 75 years and above increased by 34.6% (from 53.03 [95%CI: 50.75–55.31] in 1999 to 71.40 [95%CI: 69.10–73.70] in 2020 per 100,000 persons) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Rates of hospital stratified by age group.

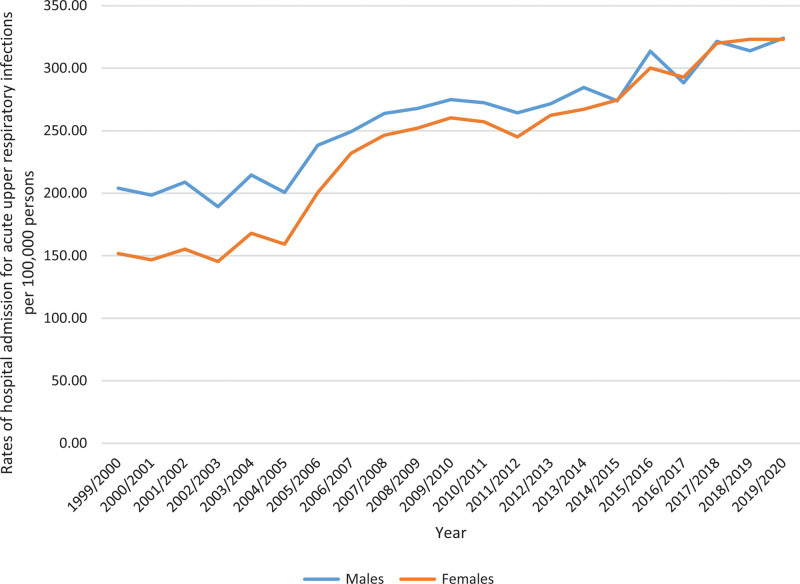

A total of 2923,517 acute upper respiratory infections hospital admission episodes were reported in England and Wales during the study time. Males contributed to 51.3% of the total number of acute upper respiratory infections hospital admission accounting for 1500,144 hospital admission episodes by a mean of 71,435 per year. Acute upper respiratory infections hospital admission rate among females increased by 1.13-fold (from 151.79 [95%CI: 150.31–153.26] in 1999 to 323.10 [95%CI: 321.08–325.13] in 2020 per 100,000 persons). Acute upper respiratory infections hospital admission rate among males increased by 58.8% (from 204.07 [95%CI: 202.32–205.82] in 1999 to 324.02 [95%CI: 321.97–326.07] in 2020 per 100,000 persons) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Rates of hospital admission stratified by gender.

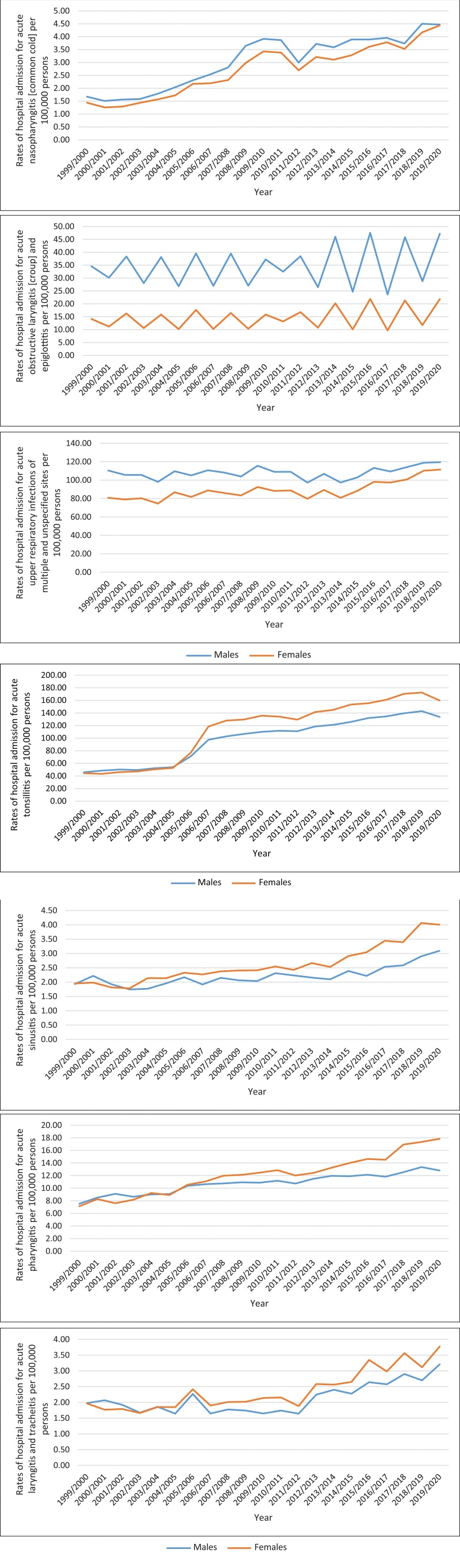

3.1. Acute upper respiratory infections admission rate by gender

The bulk of acute upper respiratory infections hospital admission rates was higher among females compared to males, that include the following: acute sinusitis, acute pharyngitis, acute tonsillitis, and acute laryngitis and tracheitis (Fig. 4). However, acute upper respiratory infections hospital admission rates for acute nasopharyngitis (common cold), acute obstructive laryngitis (croup) and epiglottitis, and acute upper respiratory infections of multiple and unspecified sites were higher among males compared to females (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Hospital admission rates for acute upper respiratory infections in England and Wales stratified by gender.

3.2. Acute upper respiratory infections admission rate by age group

Hospital admissions due to acute pharyngitis and acute tonsillitis were inversely related to age (more common among the age group below 15 years). Hospital admissions due to acute obstructive laryngitis (croup) and epiglottitis were more common among the age group: below 15 years, 60 to 74 years, 75 years and above, and 15 to 59 years, respectively. Hospital admissions due to acute nasopharyngitis (common cold) and acute upper respiratory infections of multiple and unspecified sites were more common among the age group: below 15 years, 75 years and above, 60 to 74 years, and 15 to 59 years, respectively. Hospital admissions due to acute sinusitis were more common among the age group: 15 to 59 years, 60 to 74 years, below 15 years, and 75 years and above. Hospital admissions due to acute laryngitis and tracheitis were more common among the age group: 75 years and above, 60 to 74 years, below 15 years, and 15 to 59 years, respectively (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Hospital admission rates for acute upper respiratory infections in England and Wales stratified by age group.

4. Discussion

Understanding the burden of respiratory diseases on the healthcare systems is essential to improve responses and interventions in public health. Respiratory diseases represent a large proportion of morbidity and mortality in the United Kingdom (UK).[18] They are also one of the most causes of recurrent hospital admission and primary care visits in the UK.[18] In this study, we found that the hospital admission rate due to various respiratory illnesses has increased by 82.5% between 1999 and 2020 per 100,000 persons in England and Wales. It has been shown that respiratory disease causes around 700,000 hospital admissions per year (>6.1 million bed days) in the UK.[19] Respiratory diseases account for a large part of the disease burden in the UK, which reflects that funding respiratory research is very important to enhance the responses of health care systems.

Acute upper respiratory infections represent around 39.4% of total hospital admissions, with a higher prevalence in the below 15 years’ group (70.8%). In agreement with this finding, a study showed that upper respiratory infections are inversely proportional to age.[9] Children typically get 6 to 8 upper respiratory infections a year, compared to 2 to 4 times in adults. During the preschool year, attendance at large day-cares is a risk factor for more upper respiratory infections.[20] However, it was shown that frequent infections in the preschool years provide protection from the common cold during the early school years.[20]

Hospital admission rates due to acute upper respiratory infections have increased in all age groups from 1999 to 2020, with a higher incidence in the age group 15 to 59 years. This increase could be due to a number of reasons. First, cigarette smoking is a significant risk factor for many respiratory diseases. Although the number of smokers has fallen in the UK, the current smokers represent around 14% of the total population aged 18 and above.[21] secondhand smoke can also contribute to respiratory illness, particularly in children and other vulnerable people.[22] More than 500,000 smokers have been admitted to hospitals between 2018 and 2019 in England.[21] Therefore, the government priority is to reduce the prevalence of cigarette smoking.

Air pollution is another risk factor that may contribute to the rise of hospital admission due to different respiratory diseases, including acute upper respiratory infections. Air pollution is a significant environmental risk to public health in the UK. The annual mortality from air pollution in the UK is around 28,000 and 36,000 per year.[23] It is estimated that the total cost to the national health system (NHS) due to air pollutants will be £1.6 billion.[23] Air pollution can contribute to health conditions in the population, particularly in vulnerable people. Long-term exposure to air pollution can result in chronic illnesses like respiratory diseases, which may reduce life expectancy.[24] In addition, short-term exposure to air pollution can also impact health, including effects on lung function and increases in hospital admissions and mortality due to respiratory illnesses.[23,25]

Gender type is an important epidemiological element for a variety of diseases. Our study showed that the majority of acute upper respiratory infections hospital admission rates were higher in females compared to males. In agreement with our findings, a study demonstrated that females are more likely to get upper respiratory infections, specifically sinusitis and tonsillitis.[26] However, upper respiratory infections in males are more severe than in females, which may lead to a higher mortality rate.[26] Sex hormones play a role in regulating the immune system, which could contribute to the differences in the incidence and severity of various upper respiratory infections, especially in adults.[26,27]

Noticeably, the hospital admission rates due to acute upper respiratory infections in our study were higher in the age group below 15, and 75 years and above. As per NHS guidance, older people (>60 years and above) are at high risk from respiratory infections. In older people, vaccination against some respiratory infections, such as influenza, may help to reduce hospital admission, especially during the influenza season. However, the lack of vaccines against several respiratory pathogens like respiratory syncytial virus may lead to severe pneumonia in some individuals at risk.[28] Furthermore, several viruses have the ability to mutate, causing more deadly strains which can spread very quickly and cause serious illness.[29] The management of respiratory infections has improved, but the fight against infectious pathogens is still in place.

The aging immune system is widely recognized as a major contributor to the vulnerability of the elderly to respiratory viral infections, with the immune system being further dysregulated in patients with underlying respiratory disorders such as COPD.[30–32] Inflammaging is a further intertwined process in which the aging immune system produces more inflammatory mediators and increases susceptibility to several kinds of infections.[32]

Interestingly, the rate of hospital admissions due to respiratory infections declined during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. A reduction of around 19% in respiratory-related admissions in England was seen during the first lockdown.[33] Various social measures, such as hand washing and face covering, in addition to school closures, lockdowns, and travel restrictions, helped reduce hospital admissions due to respiratory infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the burden of admissions for respiratory diseases could be reduced by implementing strategies such as face coverings and hand washing, especially in crowded public places.

This study highlighted significant epidemiological findings related to hospital admissions due to respiratory infections, which is essential to improve responses and interventions in public health. However, some limitations need to be addressed. The first limitation is that this study focuses on hospital admissions related to respiratory infections in England and Wales, which are under the umbrella of the NHS, limiting the generalizability to other countries. Second, due to the nature of this study, we have poor control over the covariates, exposure factor and potential confounders such as other comorbidities. Our hospital admission rate estimates included both admissions and re-admissions, which might lead to overestimation. Besides, we used the total population size as the denominator while calculating the admission rates. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted carefully.

5. Conclusion

Hospital admissions rate due to acute upper respiratory infections increased sharply during the study period. The rates of hospital admissions were higher among those in the age group below 15 and 75 years and above for the majority of respiratory infections, with a higher incidence in females. Further research is needed to identify the causes and developing better treatment and preventive strategies.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Ahmed M. Al Rajeh, Abdallah Y. Naser.

Data curation: Ahmed M Al Rajeh, Abdallah Y. Naser.

Formal analysis: Ahmed M. Al Rajeh, Abdallah Y. Naser.

Funding acquisition: Ahmed M. Al Rajeh.

Investigation: Ahmed M. Al Rajeh, Abdallah Y. Naser, Rayan Siraj, Abdulrhman Alghamdi, Jaber Alqahtani, Yousef Aldabayan, Abdulelah Aldhahir, Ahmed Al Haykan, Yousif Mohammed Elmosaad.

Methodology: Ahmed M. Al Rajeh, Abdallah Y. Naser.

Project administration: Ahmed M. Al Rajeh, Abdallah Y. Naser.

Resources: Ahmed M. Al Rajeh, Abdallah Y. Naser.

Software: Ahmed M. Al Rajeh, Abdallah Y. Naser.

Supervision: Ahmed M. Al Rajeh, Abdallah Y. Naser.

Validation: Ahmed M. Al Rajeh, Abdallah Y. Naser.

Visualization: Ahmed M. Al Rajeh, Abdallah Y. Naser.

Writing – original draft: Ahmed M. Al Rajeh, Abdallah Y. Naser.

Writing – review & editing: Ahmed M. Al Rajeh, Abdallah Y. Naser, Rayan Siraj, Abdulrhman Alghamdi, Jaber Alqahtani, Yousef Aldabayan, Abdulelah Aldhahir, Ahmed Al Haykan, Yousif Mohammed Elmosaad.

Abbreviations:

- CI

- confidence interval

- NHS

- National Health Service

- UK

- United Kingdom

This study used de-identified data and was considered exempt from human protection oversight by the institutional review board at Isra University, Jordan. This study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association (WMA) Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-tools-and-services/data-services/hospital-episode-statistics

Patient Episode Database for Wales (PEDW): https://www.bing.com/search?q=Patient+Episode+Database+for+Wales&cvid=8b6a4c3935ae4b8e906e348b39915be2&aqs=edge..69i57j69i64.244j0j4&FORM=ANAB01&PC=DCTS

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

How to cite this article: Al Rajeh AM, Naser AY, Siraj R, Alghamdi A, Alqahtani J, Aldabayan Y, Aldhahir A, Al Haykan A, Elmosaad YM. Acute upper respiratory infections admissions in England and Wales. Medicine 2023;102:21(e33616).

Contributor Information

Abdallah Y. Naser, Email: abdallah.naser@iu.edu.jo.

Rayan Siraj, Email: rsiraj@kfu.edu.sa.

Abdulrhman Alghamdi, Email: aalghamdi5@ksu.edu.sa.

Jaber Alqahtani, Email: Alqahtani-Jaber@hotmail.com.

Yousef Aldabayan, Email: yaldabayan@kfu.edu.sa.

Abdulelah Aldhahir, Email: aldhahir.abdulelah@hotmail.com.

Ahmed Al Haykan, Email: aalhaykan@kfu.edu.sa.

Yousif Mohammed Elmosaad, Email: yelmosaad@kfu.edu.sa.

References

- [1].Filho E, Silva A, Santos A, et al. Infecções respiratórias de importância clínica: uma revisão sistemática: respiratory infections of clinical importance: a systematic review. Rev Fimca. 2017;4:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Azevedo JVVD, Santos CACD, Alves TLB, et al. Influência do clima na incidência de infecção respiratória aguda em crianças nos municípios de campina grande e monteiro, paraíba, brasil. Rev Bras Meteorol. 2015;30:467–77. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lagare A, Maïnassara HB, Issaka B, et al. Viral and bacterial etiology of severe acute respiratory illness among children < 5 years of age without influenza in Niger. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bhat RY, Manjunath N. Correlates of acute lower respiratory tract infections in children under 5 years of age in India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:418–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Accinelli RA, Leon-Abarca JA, Gozal D. Ecological study on solid fuel use and pneumonia in young children: a worldwide association. Respirology (Carlton, Vic). 2017;22:149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gahlot A, Kumar S, Som Nath M, et al. ARI in underfive children with associated risk factors. Rama Univ J Med Sci. 2015;1:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- [7].World Health Organization. Ending preventable child deaths from pneumonia and diarrhoea by 2025: the integrated global action plan for pneumonia and diarrhoea. The integrated Global Action Plan for Pneumonia and Diarrhoea (GAPPD). 2013. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241505239 [accessed February 05, 2023]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [8].Mizgerd JP. Lung infection--a public health priority. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e761–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Heikkinen T, Järvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361:51–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Correia W, Dorta-Guerra R, Sanches M, et al. Study of the etiology of acute respiratory infections in children under 5 years at the Dr. Agostinho Neto Hospital, Praia, Santiago Island, Cabo Verde. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Nair H, Simões EAF, Rudan I, et al. Global and regional burden of hospital admissions for severe acute lower respiratory infections in young children in 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2013;381:1380–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bhuyan GS, Hossain MA, Sarker SK, et al. Bacterial and viral pathogen spectra of acute respiratory infections in under-5 children in hospital settings in Dhaka city. PLoS One. 2017;12:e01744881–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Marcone DN, Carballal G, Ricarte C, et al. Respiratory viral diagnosis by using an automated system of multiplex PCR (FilmArray) compared to conventional methods. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2015;47:29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Naser AY, Mansour MM, Alanazi AFR, et al. Hospital admission trends due to respiratory diseases in England and Wales between 1999 and 2019: an ecologic study. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC). Hospital episode statistics. 2021. Available at: http://content.digital.nhs.uk/hes [accessed January 13, 2021].

- [16].NHS Wales Informatics Service. Annual PEDW data tables. 2021. Available at: http://www.infoandstats.wales.nhs.uk/page.cfm?pid=41010&orgid=869 [accessed January 13, 2021].

- [17].ICD10 Codes. ICD-10-CM codes. 2021. Available at: https://www.aapc.com/codes/icd-10-codes-range/ [accessed July 22, 2022].

- [18].Chung F, Barnes N, Allen M, et al. Assessing the burden of respiratory disease in the UK. Respir Med. 2002;96:963–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Snell N, Strachan D, Hubbard R, et al. Burden of lung disease in the UK; findings from the British Lung Foundation’s “respiratory health of the nation” project. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(suppl 60):PA4913. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ball TM, Holberg CJ, Aldous MB, et al. Influence of attendance at day care on the common cold from birth through 13 years of age. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Office for National Statistics. Adult smoking habits in the UK: 2019. 2021. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandlifeexpectancies/bulletins/adultsmokinghabitsingreatbritain/2019 [accessed December 7, 2021].

- [22].Carreras G, Lugo A, Gallus S, et al.; TackSHS Project Investigators. Burden of disease attributable to second-hand smoke exposure: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2019;129:105833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].The Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Air pollution: applying all our health. 2021. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/air-pollution-applying-all-our-health/air-pollution-applying-all-our-health.

- [24].Lee YG, Lee PH, Choi SM, et al. Effects of air pollutants on airway diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:9905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Huang ZH, Liu XY, Zhao T, et al. Short-term effects of air pollution on respiratory diseases among young children in Wuhan city, China. World J Pediatr. 2022;18:333–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Falagas ME, Mourtzoukou EG, Vardakas KZ. Sex differences in the incidence and severity of respiratory tract infections. Respir Med. 2007;101:1845–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kadel S, Kovats S. Sex hormones regulate innate immune cells and promote sex differences in respiratory virus infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fraser CS, Jha A, Openshaw PJ. Vaccines in the prevention of viral pneumonia. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38:155–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Leung NHL. Transmissibility and transmission of respiratory viruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:528–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Day K, Ostridge K, Conway J, et al. Interrelationships among small airways dysfunction, neutrophilic inflammation, and exacerbation frequency in COPD. Chest. 2021;159:1391–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wilkinson TMA. Immune checkpoints in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, et al. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:92–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Shah SA, Brophy S, Kennedy J, et al. Impact of first UK COVID-19 lockdown on hospital admissions: interrupted time series study of 32 million people. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;49:101462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]