Abstract

Purpose of Review

Imaging is used in the diagnosis of peripheral and axial disease in juvenile spondyloarthritis (JSpA). Imaging of the joints and entheses in children and adolescents can be challenging for those unfamiliar with the appearance of the maturing skeleton. These differences are key for rheumatologists and radiologists to be aware of.

Recent Findings

In youth, skeletal variation during maturation makes the identification of arthritis, enthesitis, and sacroiliitis difficult. A great effort has been put forward to define imaging characteristics seen in healthy children in order to more accurately identify pathology. Additionally, there are novel imaging modalities on the horizon that are promising to further differentiate normal physiologic changes verse pathology.

Summary

This review describes the current state of imaging, limitations, and future imaging modalities in youth, with key attention to differences in imaging interpretation of the peripheral joints, entheses, and sacroiliac joint in youth and adults.

Keywords: Juvenile Spondyloarthritis (JSpA), Sacroiliitis, enthesitis, sacroiliac joint, MRI, ultrasound

Introduction

Juvenile spondyloarthritis (JSpA) is a broad category that encompasses multiple phenotypes such as enthesitis related arthritis (ERA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), inflammatory bowel disease related arthropathy, juvenile ankylosing spondylitis, and reactive arthritis. Juvenile-onset disease typically refers to disease with symptoms that start prior to age 16. JSpA can manifest with peripheral and axial joint involvement either in combination or isolation. Several studies have demonstrated that juvenile-onset disease is associated with more peripheral disease (arthritis and enthesitis), more hip arthritis, and less axial disease. The most common affected peripheral joints in youth are those of the lower extremity and it is most often oligoarticular. It is estimated that about one-fifth of patients diagnosed with JSpA will have axial disease at presentation and up to one-third will develop axial disease within several years of disease onset (1)(2)(3)(4). Peripheral and axial disease in youth may be associated with high morbidity including poorer function, pain, missed school and inability to participate in sports and other activities. Since disease modifying conventional synthetic anti-rheumatic agents (csDMARDs) are not effective for axial disease, the presence of sacroiliitis influences treatment decisions for patients with JSpA, frequently prompting the use of biologics. Several studies have demonstrated that tenderness of lower back by history or direct palpation are often discordant with imaging results. Additionally, youth sacroiliitis may be asymptomatic even in the presence of damage (2)(3)(4)(5)(6). This review will provide an overview of imaging of the peripheral and axial skeleton in JSpA, focusing on differences in youth and adults.

PERIPHERAL SKELETON-

Arthritis.

Peripheral joints in youth are easily and reliably imaged with ultrasonography. Ultrasound can be used as a point of care in the office and can assess for early inflammatory changes. Ultrasound modalities used in assessing pathology do not differ from adults, with structural findings assessed using grayscale imaging. Doppler signaling can be used to show the increased vascularity in inflamed soft tissues (7)(8). The maturing skeleton can pose a challenge to the interpretation of ultrasounds. Ossification centers and physes (growth plates) may make landmarks more difficult to find and these are key to proper image obtainment (Figure 1). Physiologic enhanced blood flow is typical in young children with normal, increased vascularity seen within the synovium, periarticular soft tissues and epiphyseal/apophyseal cartilage. This detectable physiologic vascularity is age and joint dependent, with the youngest children demonstrating the most vascularity (9). Given these challenges the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) ultrasound pediatric task force was formed to establish definitions for normal joint findings in healthy youth. The group defined the expected structural evolution and the appearance and locations of joint physiologic vascularity(9)(10). This work standardized ultrasound examination methods to facilitate increased reliability of findings. An atlas of normal joint anatomic structures and normal vascularization by ultrasound was created as part of this effort (9)(10). This work was pivotal in defining features of healthy children’s joints at different ages, which is necessary in order to accurately and reliably identify joint pathology. Preliminary definitions for synovitis and its descriptors (effusion, synovial Doppler signal, synovial hypertrophy) in youth using grayscale and Doppler mode ultrasonography were developed using a consensus process and subsequently validated using standardized images of joints with varying severity of synovitis (11). Several principles were established for the evaluation of synovitis in youth and include: 1) synovitis assessment should include grayscale and Doppler assessments, 2) synovial thickening can be detected using grayscale alone, 3) key grayscale findings in youth include synovial hypertrophy and joint effusion, 4) effusions in youth are defined as “abnormal, intraarticular, anechoic, or hypoechoic [displaceable] material, 5) Doppler signal must be identified within the synovium, 6) synovial hypertrophy is intraarticular, hypoechoic and non-displaceable.

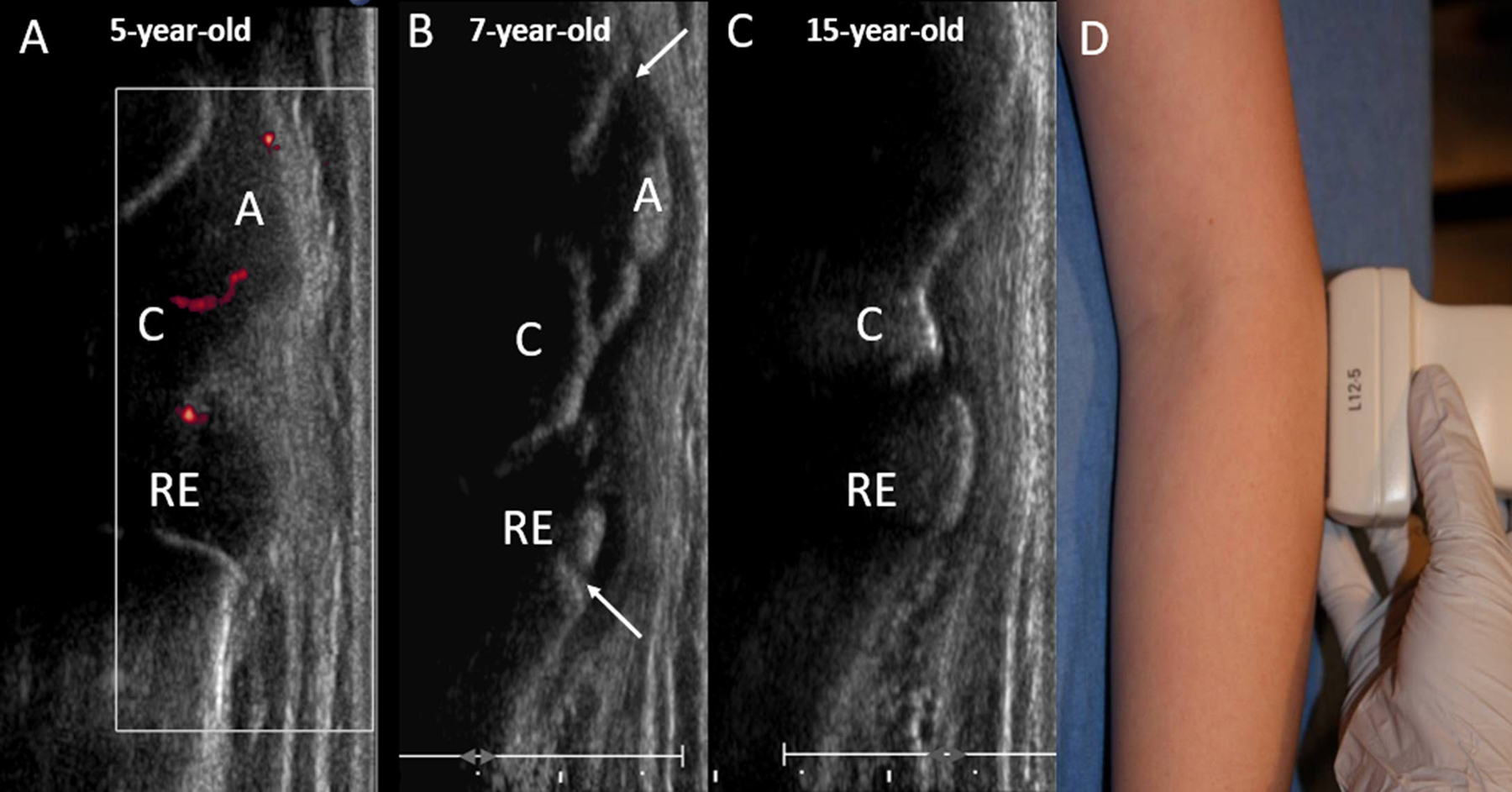

Figure 1.

Normal skeletal maturation. Long axis ultrasound images of the lateral aspect of the elbow in a healthy (A) 5-year-old girl, (B) 7-year-old girl and (C) 15-year-old girl. (A) Shows a completely cartilaginous capitellum, proximal radial epiphysis and lateral epicondylar apophysis. Normal vascularity is demonstrated by power Doppler with blood flow present in the unossified cartilage. (B) At age 7 years, there is partial ossification of the epiphyses and apophysis. The physes (arrows) remain open. (C) At age 15 years, the patient is skeletally mature with closure of the physes. D. Photograph of the elbow demonstrating transducer placement in the long axis along the lateral aspect of the elbow. C=capitellum, RE = proximal radial epiphysis, A= lateral epicondylar apophysis.

MRI is also an excellent tool to assess for peripheral arthritis. Unfortunately, most children younger than 8 years of age cannot tolerate imaging without sedation. Like in adults, MRI can evaluate for both acute changes, such as bone marrow edema, synovitis and effusion (12), and chronic inflammatory changes, such as erosions and cartilage abnormalities. In children, cortical erosion can be challenging to interpret due to physiologic irregularities in newly ossified bones that could be mistaken for erosions. To prevent overcalling of erosions, additional features such as assessment of the overlying cartilage and shape of the bones should be considered in the evaluation of a joint (13).

Dactylitis.

Dactylitis or “sausage digits” is a feature of JSpA and it refers to swelling within a digit that extends beyond the borders of the joint. This swelling can uniformly involve the full digit or be fusiform around the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint; it can be present in the fingers or toes. Dactylitis is often a clinical diagnosis, but imaging can be helpful when diagnosis or exam is unclear. Both ultrasound and MRI can be used to assess dactylitis. The most characteristic finding is flexor tenosynovitis with associated diffuse extra-tendinous edema, enthesitis, and with or without synovitis (14)(15)(Figure 2). In adults, dactylitis can be seen in patients with gout, which is an uncommonly seen in children. Dactylitis in adult psoriatic arthritis is an adverse prognostic sign and is associated more erosive disease (14)(16)(17). This prognostic association has not been established in children with dactylitis.

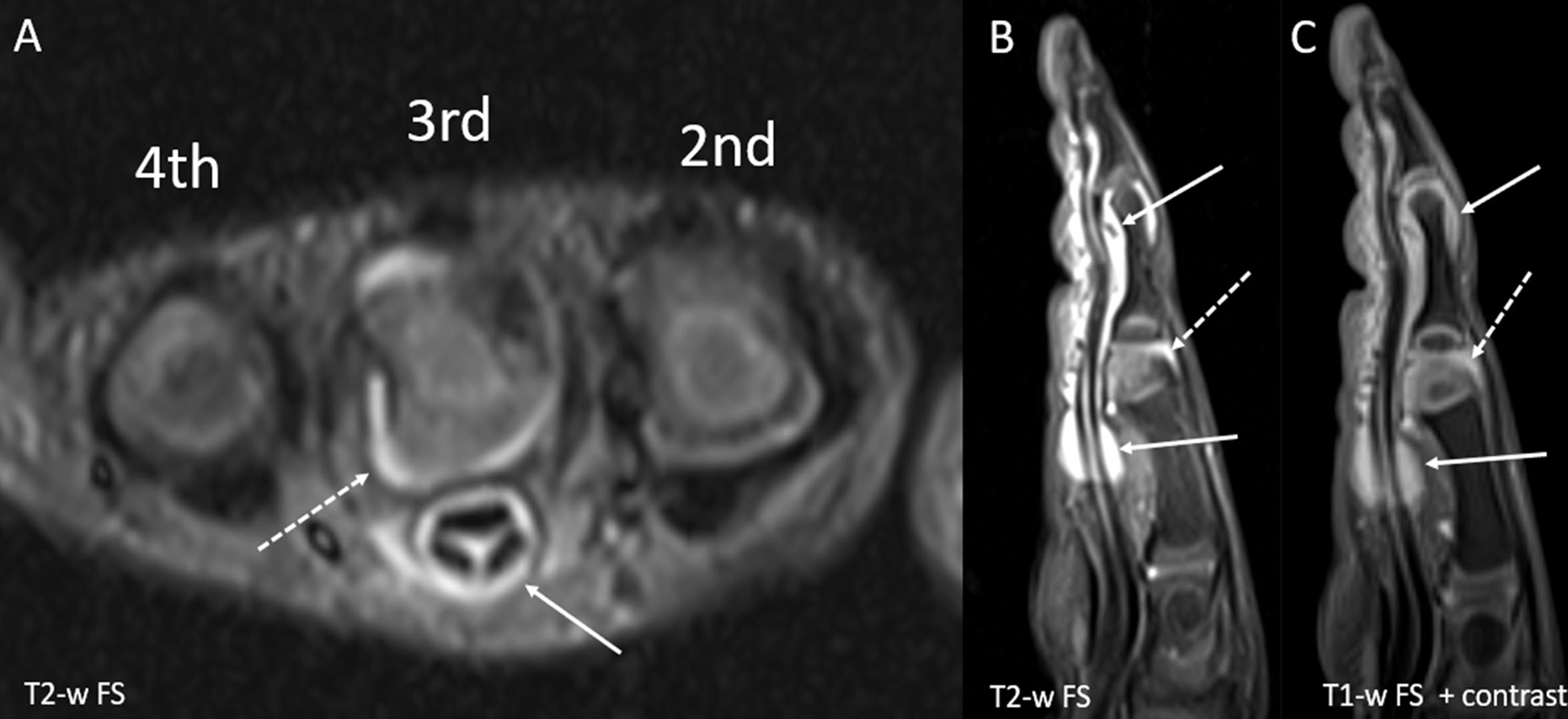

Figure 2.

Dactylitis in a 29-month-old girl with pauciarticular JIA. (A) Short axis and (B) sagittal T2-weighted fat suppressed (FS) images show a large amount of fluid within the flexor tendon sheath of the third digit (solid arrows). There is adjacent soft tissue edema with resultant enlargement of the digit. A small amount of fluid is seen within the proximal interphalangeal joint (dashed arrow) and the distal interphalangeal joint. (C) Sagittal T1-weighted FS post contrast image shows diffuse enhancement of the tendon sheath (solid arrow) as well as the synovium of the proximal interphalangeal joint (dashed arrow) which is compatible with active tenosynovitis and joint synovitis, respectively.

Entheses.

As in adults, the enthesis is a complex structure including the tendon, the sub-tendon bursae and the insertion of tendon fibers into bone through fibrocartilage. Imaging of the entheses can be challenging in youth, particularly in those with unossified cartilage. Additionally, different etiologies of entheseal pathology need to be considered in adults and children. In adults, the tendon and its entheseal attachment is prone to degenerative change such as enthesophyte formation, tendinopathy and tendon rupture. Degenerative change is not typically observed in youth, however, tendon avulsion at the entheses and apophysitis from overuse and strain, especially in young athletes and children undergoing a period of rapid growth, is not uncommon (18). Examples of these common over-use pathologies are Osgood-Schlatter’s disease at the attachment of the inferior patellar tendon on the tibial tuberosity and Sever’s disease at the insertion of the Achilles tendon into the calcaneus. These conditions need to be distinguished from pathologic changes observed with JSpA. A detailed history and exam are critical, and imaging can be very helpful.

The entheses are most often imaged using ultrasonography with Doppler or MRI. Avulsion fractures can sometimes be seen on radiograph. Knowledge of typical physiologic findings is critical to enable reliable identification of pathology. In adults, vascularity at the entheses is an important feature to distinguish SpA from healthy controls(19). However, doppler signal can be seen in the lower extremity entheses of healthy younger children(20)(21)(22). This physiologic signal is typically with 5 mm of the entheses and does not vary with positioning (20). Additionally, cartilage thickness decreases as youth approach maturity with girls maturing earlier than boys(21)(22). Increased peri-tendonous vascularity can also be observed in active pre- and peripubertal youth, this is typically pathologic in adults with SpA (22). Structural lesions at the entheses such as calcifications and enthesophytes are observed much less frequently in youth compared to adults(23) (18).

AXIAL SKELETON

Radiographs can be helpful to exclude non-inflammatory causes of back pain in youth, such as trauma, infection, or malignancy. However, in the evaluation of inflammatory sacroiliitis, the utility of radiographs is limited. Unfortunately, radiographs are not helpful for early detection of disease as they can only show chronic change, not active inflammation (24); normal radiographs do not exclude the presence of early inflammatory axial disease. Difficulty in radiograph interpretation, even by experienced radiologists, results in a large proportion of false positives which can cause youth and their families anxiety(24). Age-related changes at the sacroiliac joint are common in adults and children. In adults, up to 25% of those reporting back pain have cortical irregularities, primarily from sclerosis and osteophytes. Age-related changes in youth are secondary to normal bony contour undulations along the surface of the joint, most often the ilium (25). Despite radiography’s limitations to show early changes, many insurance plans require them before obtaining more advanced imaging. Additionally, in some areas of the world advanced imaging is difficult to access and radiography remains the mainstay for evaluation of disease.

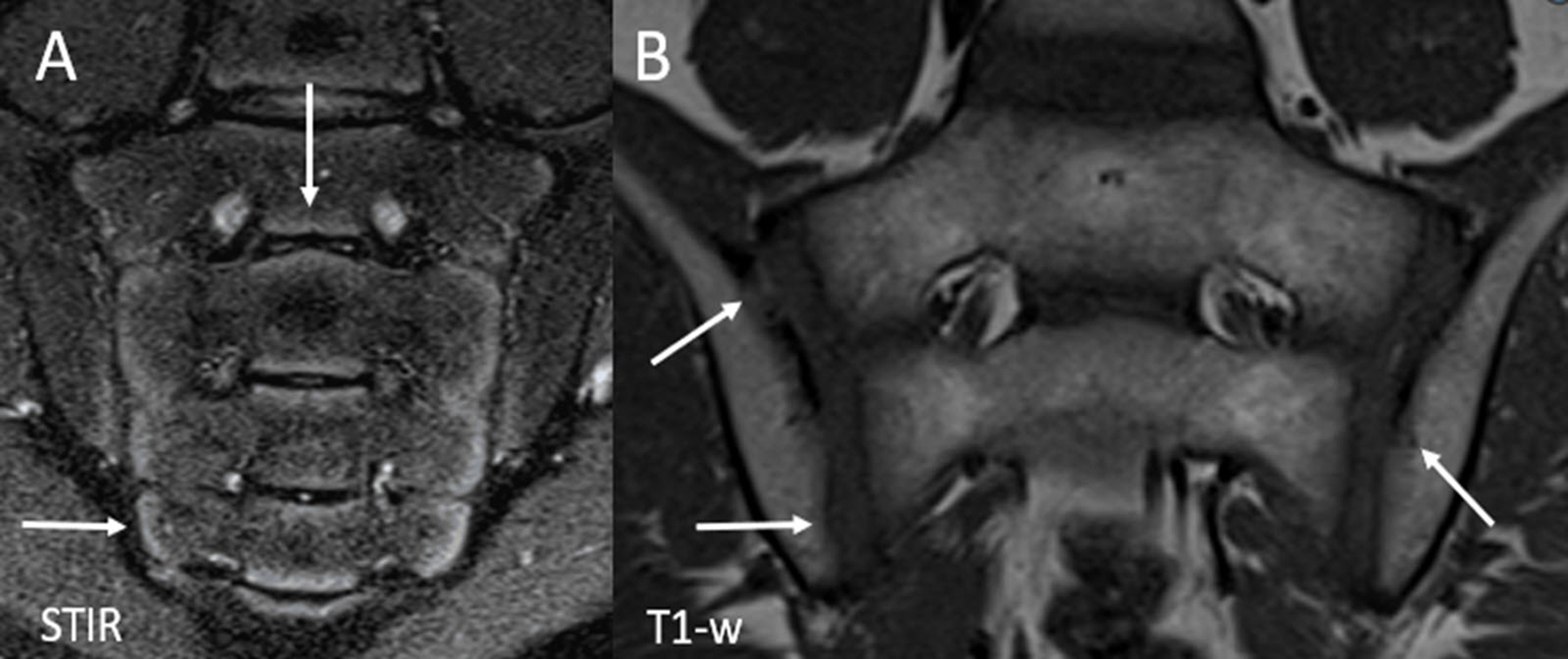

MRI is a non-invasive imaging technique that has no associated radiation exposure and is increasinglu used in the evaluation of axial disease in adults and youth (26). MRI of the sacroiliac joint typically requires 30–40 minutes in the scanner and are more costly to perform compared with radiographs. Many studies have shown that, when compared to radiographic imaging of the pelvis, MRI is diagnostically superior at identifying inflammation and facilitating diagnosis of axial arthritis in children with JSpA (24)(27). Importantly, MRI can detect early subchondral inflammation and structural lesions long before findings can be identified on radiographs. The sequences used to evaluate the sacroiliac joint are similar to those used in adults and include enhanced T1-weighted sequences without fat suppression for assessment of chronic structural changes, and fluid-sensitive sequences such as Short Tau Inversion Recovery (STIR) or T2-weighted fat-saturated sequences for the assessment of active inflammation (28)(29). Given the anatomy and angle of the sacroiliac joint, coronal oblique slices are optimal to capture the full extent of the joint (FIGURE 3). Chronic changes typical of sacroiliitis that can be seen in youth are the same as seen in adults and on T1-weighted imaging include erosion, sclerosis, fat lesion, backfill, and ankylosis (29) (FIGURE 4). The fluid-sensitive sequences can identify subchondral bone marrow edema (BME), joint space inflammation, capsulitis, and enthesitis, which are all features of active inflammation of JSpA (28)(FIGURE 4).

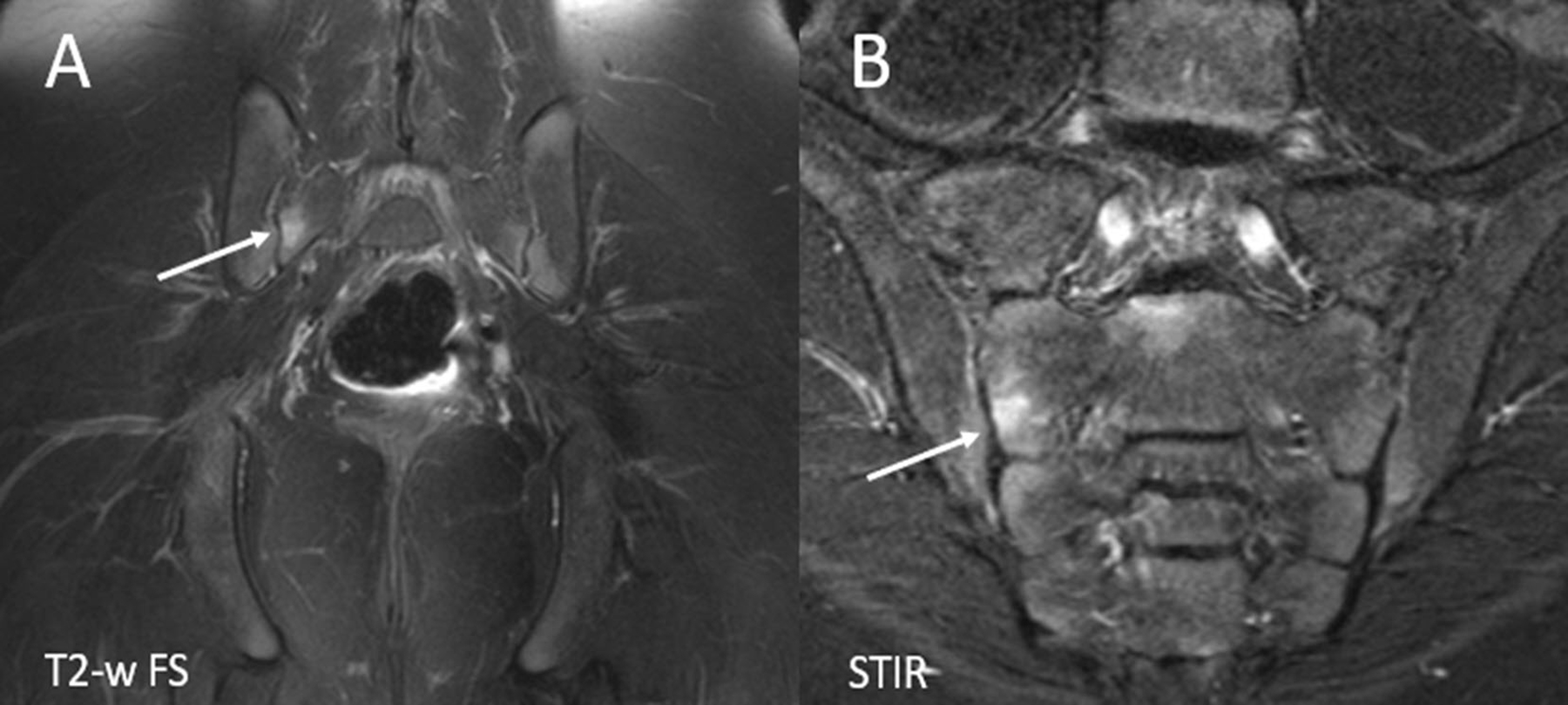

Figure 3.

Large versus small field of view imaging. (A) Coronal T2-weighted fat suppressed (FS) large field of view image of the pelvis shows a small amount of marrow edema within the right aspect of the sacrum (arrow). B. Small field of view coronal oblique STIR image of the sacroiliac joints shows the focus of bone marrow edema within the right aspect of the sacrum, confirming the periarticular location and better demonstrating the location within the mid to lower aspect of the right S2 level. STIR= Short tau inversion recovery.

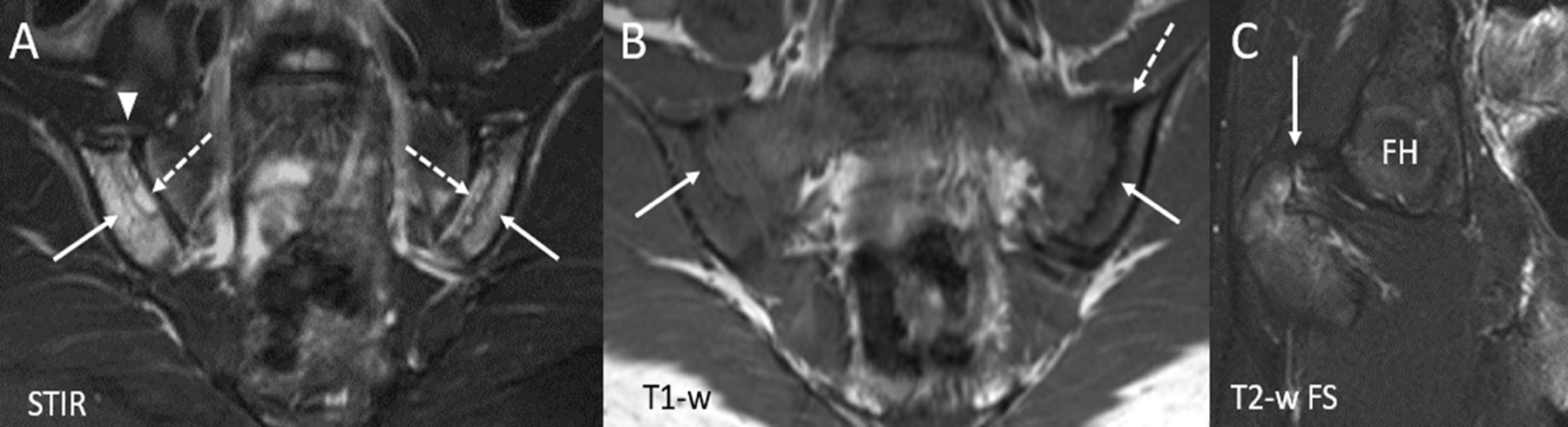

Figure 4.

16-year-old boy with juvenile spondyloarthritis. (A) Coronal oblique STIR image of the sacroiliac joints shows active inflammatory changes with bone marrow edema within right and left iliac bones (solid arrows) with edema within erosion cavities (dashed arrows). There is capsulitis along the anterior aspect of the right sacroiliac joint (arrowhead). (B) Coronal oblique T1-weighted image of the sacroiliac joints depicts chronic, structural changes with erosion cavities seen along the articular surfaces of the both iliac bones (solid arrows). There is a small amount of sclerosis along the superior aspect of the left iliac bone (dashed arrow). (C) Coned down coronal T2-weighted fat suppressed (FS) image of the right hip (obtained from large field of view pelvis image) shows active enthesitis at the ligamentous insertion of the greater trochanter (arrow). STIR = Short tau inversion recovery, FH= Femoral head.

Ascertainment of normal versus abnormal in youth can be tricky secondary to normal developmental changes in the immature skeleton. One recent publication underscores the difficulty in interpretation, even at large academic centers (30). In this study, Weiss et al evaluated the agreement between local radiology reports and central imaging reviewers in identification of active inflammation and structural damage of the sacroiliac joint. Sensitivity across institutions for inflammatory sacroiliitis was high, meaning very few cases of sacroiliitis are missed. However, the positive predictive value, using a central imaging team as the reference standard, was highly variable with a range of 12.5% to 100% across institutions for the detection of inflammation. The primary reason for this variability is that the sacroiliac joint is a complex structure that undergoes many developmental physiologic changes along with anatomic variation (25). Normal features in a developing skeleton, such as increased vascularity, cartilage maturation, and active hematopoietic marrow, can have hyperintense signal on STIR, which can be mistaken for active inflammation by those not familiar with the appearance of the maturing skeleton (25)(31)(32) (Figure 5). Fortunately, there are some lessons learned from healthy youth that can help differentiate normal from abnormal (25). In healthy young children, the physiologic metaphyseal equivalent signal that is seen on STIR sequences is primarily homogenous and is located along the articular surface of the sacrum, tracing the contour of the segmental sacral apophyses. As youth approach skeletal maturity this signal becomes thinned, less pronounced, and may no longer extend along the entire sacral articular surface.

Figure 5.

Normal skeletal maturation in a healthy 10-year-old girl. (A) Coronal oblique STIR image of the sacroiliac joints demonstrates physiologic hyperintense metaphyseal equivalent signal along the periphery of the sacral apophyses (arrows) and to a lesser extent, the articular aspect of the iliac bones. The signal extends along the entire aspect of the sacrum (S4 and S5), inferior to the level of the joint space. (B) Coronal oblique T1-weighted image of the sacroiliac joints shows normal undulations and irregularities along the articular surface of the joints (arrows) which are more commonly found on the iliac side. STIR = Short tau inversion recovery.

In adults, the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis (ASAS) International Society developed and validated criteria of a positive MRI result for sacroiliitis in 2009 and updated the definition in 2016 (33). When these criteria are applied to images of children, there is low sensitivity in identifying active sacroiliitis (31). Another study showed that up to 40% of young adult athletes–both recreational and elite– met ASAS criteria for sacroiliitis (34). These athletes had 3–4 affected sacroiliac joint quadrants, however most of the BME was confined to the posterior ilium and there were no detectable erosions (34). Subsequently a data-driven quantitative definition of BME in ≥4 sacroiliac joint quadrants at any location or at the same location on more than 3 consecutive slices was developed and achieved a specificity of greater than 95% in adults (35). The OMERACT juvenile arthritis imaging workgroup developed definitions of inflammation and damage in JSpA (28)(29)(36). These criteria were not intended for diagnostic purposes, but for research purposes in defining positive MRI results. Importantly, definitions developed by this group encompassed comparisons with normal physiologic changes in age- and sex-matched children. Atlases of MRI findings of sacroiliitis in JSpA were created as part of this endeavor (28)(29). The goal is to apply these definitions to a pediatric scoring system, the Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis MRI Score (JAMRIS-SIJ)(37). Recently, a data-driven quantitative definition for active inflammatory lesions typical of JSpA was developed, and subsequently validated in an independent cohort (38). This quantitative definition in youth leveraged the JAMRIS-SIJ definition of subchondral BME in youth. Positive MRI in youth with JSpA and suspected axial disease was defined as BME in ≥3 quadrants across all MRI slices (sensitivity 98.6%, specificity 96.5%); this definition had higher sensitivity and specificity in youth than the adult data-driven definition of positive inflammatory MRI.

The ongoing ossification process in youth can also lead to articular cortical undulations, which on T1 imaging, can be difficult to discern from erosion for those not familiar with the appearance of the maturing skeleton (25)(31)(32) (Figure 5). A study of 70 healthy youth found that cortical irregularities were most common along the ilium and in the peripubertal group (25). These findings are in accordance with an earlier autopsy study that reported smooth bony surfaces until puberty and subsequent development of bony ridges and grooves, mostly on the ilium (39). Recently, a data-driven quantitative definition for chronic structural lesions typical of JSpA was developed, and subsequently validated in an independent cohort (38). This quantitative definition in youth leveraged the JAMRIS-SIJ definitions of structural changes in youth. Positive MRI for structural lesions in youth with JSpA typical of axial disease was defined as structural lesion(s): erosion in ≥3 quadrants or sclerosis or fat lesion in ≥2 SIJ quadrants or backfill or ankylosis in ≥2 joint halves across all SIJ MRI slices (sensitivity 98.6%, specificity 95.5%).

Though identification of active sacroiliitis of children on MRI can be challenging, it is still the mainstay of the imaging evaluation of axial disease in JSpA in most parts of the world.

Novel Techniques on the Horizon

There are novel imaging techniques of the sacroiliac joint that are being explored, specifically MRI T2-mapping, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and Dual-energy CT (40).

MRI T2-mapping is being explored as a possible biomarker to assess for sacroiliitis. This technique is used to study tissues at the molecular level and assesses water mobility. T2 relaxation times are calculated with increased T2 relaxation times indicating increased water mobility in tissues. Therefore, T2-mapping can provide a quantitative means to identify the early stages of cartilage matrix changes that precede visible morphologic damage (41). T2-mapping has been shown to be feasible in adults with SpA and is promising at assessing axial disease (44, 45). (43). T2-maps showed longer T2 relaxation times in cases of sacroiliitis vs healthy controls. Larger T2-mapping studies are needed to assess its potential usefulness in clinical practice and clinical trials.

DWI is an imaging method on T2 sequences that measures random Brownian motion of water molecules within tissue—based off the type of tissue water content an apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) is generated(44). Several studies have shown that DWI is effective quantitative method in the early diagnosis of adults with Spondyloarthritis and recent work has explored its use in JSpA(40)(45)(46). ADC values are significantly different in adolescents with active sacroiliitis compared to those without disease and potentially could be used for diagnosis and disease monitoring (47)(48). It is important to note that ADC values in normal immature skeletons have overlap with ADC values of active sacroiliitis, leading to potential misdiagnosis in younger patients(49).

Another imaging modality being studied is dual-energy virtual noncalcium (VNCa) computed tomography (CT). While CT imaging is typically avoided in children as it requires radiation,, CT imaging is more widely available, quicker to obtain, and more tolerated by younger children than MRI. Dual-energy CT uses two different energy sources to evaluate tissues (40)(50). Algorithms are based on the X–ray absorption of bone minerals and bone marrow, which allows for the detection of BME (50) (51). Its high resolution enables precise and more sensitive detection of small erosions than in conventional radiography and MRI (50)(51). In a prospective study of patients ages 14–41 years, dual-energy VNCa CT was able to detect BME in patients with axial spondylarthritis (51). This study showed feasibility, but further studies are needed to validate in the adult population along with children.

Conclusion

Imaging plays a key role in the diagnosis of peripheral and axial disease in JSpA. Early and accurate identification of peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, and sacroiliitis impacts treatment and overall disease trajectory of youth with JSpA. Imaging of the peripheral joints in maturing youth is challenging due not only to the variable appearance of ossification centers and physes, but also physiologic periarticular vascularity. However, international efforts and imaging atlases have made strides to improving the reliability and accuracy of detection of pathology in youth. MRI is the key imaging modality used to evaluate for inflammation and early structural changes seen in sacroiliitis. Distinguishing physiologic subchondral marrow signal from mild pathologic subchondral edema is challenging for those unfamiliar with the appearance of the maturing sacroiliac joint. Imaging atlases of normal and pathologic findings in the sacroiliac joints of youth as well as data-driven definitions of inflammation and structural change in youth are published and should aid in the assessment of axial disease.

Key points:

Identification of arthritis, dactylitis, enthesis, or sacroiliitis associated with JSpA early in the disease course is key to positivity impacting future morbidity.

When using ultrasound to assess for peripheral joint disease, knowledge of age-related changes in ossification centers and periarticular vascularity are key to accurate interpretation.

Compared to adults, pediatric entheses are more vascularized and are more prone to apophysitis, making ultrasound and MRI evaluation of enthesitis more challenging in pediatrics.

As in adults, MRI is the preferred modality for assessing the sacroiliac joints; however, age-related maturation changes must be considered when assessing for pathology

Footnotes

Disclosures:

HC- no disclosures.

NAC- Royalties: Elsevier (<$1000 to author)

PFW- Support for the present manuscript: NIH K24 AR078950 (payment to institution); Grants: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, NIH, Spondylitis Association of America (payment to institution); Royalties/licenses: Up-to-date (<$10K to author); Consulting fees: Site investigator for Pfizer and Abbvie Clinical Trials (Payment to institution), Advisory Board member: Lily, Biogen, Novartis (all <$10K to author), and Consulting fees: Pfizer, Cerecor (payment to institution); Speaking payment or honoraria: 2022 Rheum Now Speaker (<$5K to author), Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, and Psoriasis Foundation – honoraria for educational materials (<$5k to author).

Contributor Information

Hallie Carol, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Rheumatology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Nancy A. Chauvin, Department of Radiology, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH.

Pamela F. Weiss, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Rheumatology and Center for Pediatric Clinical Effectiveness, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia PA, USA.

References

- 1.Weiss PF, Xiao R, Biko DM, Chauvin NA. Assessment of Sacroiliitis at Diagnosis of Juvenile Spondyloarthritis by Radiography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, and Clinical Examination. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016. Feb;68(2):187–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bollow M, Braun J, Biedermann T, Mutze S, Paris S, Schauer-Petrowskaja C, et al. Use of contrast-enhanced MR imaging to detect sacroiliitis in children. Skeletal Radiol 1998. Nov;27(11):606–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.STOLL ML, BHORE R, DEMPSEY-ROBERTSON M, PUNARO M. Spondyloarthritis in a Pediatric Population: Risk Factors for Sacroiliitis. J Rheumatol 2010. Nov;37(11):2402–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pagnini I, Savelli S, Matucci-Cerinic M, Fonda C, Cimaz R, Simonini G. Early predictors of juvenile sacroiliitis in enthesitis-related arthritis. J Rheumatol 2010. Nov;37(11):2395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taxter AJ, Chauvin NA, Weiss PF. Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain in the Pediatric Population. Phys Sportsmed 2014. Feb;42(1):94–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demir S, Ergen FB, Taydaş O, Sağ E, Bilginer Y, Aydıngöz Ü, et al. Spinal involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: what do we miss without imaging? Rheumatol Int 2022. Mar;42(3):519–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss PF, Chauvin NA. Imaging in the diagnosis and management of axial spondyloarthritis in children. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2020. Dec;34(6):101596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ultrasound in sacroiliitis: the picture is shaping up | SpringerLink [Internet] [cited 2023 Jan 21]. Available from: 10.1007/s00296-017-3863-6 [DOI]

- 9.Collado P, Windschall D, Vojinovic J, Magni-Manzoni S, Balint P, Bruyn GAW, et al. Amendment of the OMERACT ultrasound definitions of joints’ features in healthy children when using the DOPPLER technique. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2018. Apr 10;16:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collado P, Vojinovic J, Nieto JC, Windschall D, Magni-Manzoni S, Bruyn GAW, et al. Toward Standardized Musculoskeletal Ultrasound in Pediatric Rheumatology: Normal Age-Related Ultrasound Findings. Arthritis Care & Research 2016;68(3):348–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth J, Ravagnani V, Backhaus M, Balint P, Bruns A, Bruyn GA, et al. Preliminary Definitions for the Sonographic Features of Synovitis in Children. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017. Aug;69(8):1217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nusman CM, Hemke R, Schonenberg D, Dolman KM, van Rossum MAJ, van den Berg JM, et al. Distribution pattern of MRI abnormalities within the knee and wrist of juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients: signature of disease activity. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014. May;202(5):W439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erosion or normal variant? 4-year MRI follow-up of the wrists in healthy children | SpringerLink [Internet] [cited 2023 Jan 22]. Available from: 10.1007/s00247-015-3494-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.McGonagle D, Tan AL, Watad A, Helliwell P. Pathophysiology, assessment and treatment of psoriatic dactylitis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2019. Feb;15(2):113–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamard A, Burns R, Miquel A, Sverzut JM, Chicheportiche V, Wybier M, et al. Dactylitis: A pictorial review of key symptoms. Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging 2020. Apr 1;101(4):193–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brockbank JE, Stein M, Schentag CT, Gladman DD. Dactylitis in psoriatic arthritis: a marker for disease severity? Ann Rheum Dis 2005. Feb;64(2):188–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Healy PJ, Groves C, Chandramohan M, Helliwell PS. MRI changes in psoriatic dactylitis—extent of pathology, relationship to tenderness and correlation with clinical indices. Rheumatology 2008. Jan 1;47(1):92–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss PF, Roth J. Juvenile-Versus Adult-Onset Spondyloarthritis: Similar, but Different. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2020. May;46(2):241–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guldberg-Møller J, Terslev L, Nielsen SM, Kønig MJ, Torp-Pedersen ST, Torp-Pedersen A, et al. Ultrasound pathology of the entheses in an age and gender stratified sample of healthy adult subjects: a prospective cross-sectional frequency study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019;37(3):408–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roth J, Stinson SE, Chan J, Barrowman N, Di Geso L. Differential pattern of Doppler signals at lower-extremity entheses of healthy children. Pediatr Radiol 2019. Sep;49(10):1335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jousse-Joulin S, Cangemi C, Gerard S, Gestin S, Bressollette L, de Parscau L, et al. Normal sonoanatomy of the paediatric entheses including echostructure and vascularisation changes during growth. Eur Radiol 2015. Jul;25(7):2143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chauvin NA, Ho-Fung V, Jaramillo D, Edgar JC, Weiss PF. Ultrasound of the joints and entheses in healthy children. Pediatr Radiol 2015. Aug;45(9):1344–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss PF, Chauvin NA, Klink AJ, Localio R, Feudtner C, Jaramillo D, et al. Detection of enthesitis in children with enthesitis-related arthritis: dolorimetry compared to ultrasonography. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014. Jan;66(1):218–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss PF, Xiao R, Brandon TG, Biko DM, Maksymowych WP, Lambert RG, et al. Radiographs in screening for sacroiliitis in children: what is the value? Arthritis Res Ther 2018. Jul 11;20(1):141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chauvin NA, Xiao R, Brandon TG, Biko DM, Francavilla M, Khrichenko D, et al. MRI of the Sacroiliac Joint in Healthy Children. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2019. Apr 11;1–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Mandl P, Navarro-Compán V, Terslev L, Aegerter P, van der Heijde D, D’Agostino MA, et al. EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in the diagnosis and management of spondyloarthritis in clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis 2015. Jul;74(7):1327–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaremko JL, Liu L, Winn NJ, Ellsworth JE, Lambert RGW. Diagnostic utility of magnetic resonance imaging and radiography in juvenile spondyloarthritis: evaluation of the sacroiliac joints in controls and affected subjects. J Rheumatol 2014. May;41(5):963–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.**Herregods N, Maksymowych WP, Jans L, Otobo TM, Sudoł-Szopińska I, Meyers AB, et al. Atlas of MRI findings of sacroiliitis in pediatric sacroiliac joints to accompany the updated preliminary OMERACT pediatric JAMRIS (Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis MRI Score) scoring system: Part I: Active lesions. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2021. Oct;51(5):1089–98.This article is an atlas that highlights normal MRI findings and growth related changes of the sacroiliac joint in pediatrics. Additionally, goes through MRI imaging of sacroiliitis that can be used as references.

- 29.**Herregods N, Maksymowych WP, Jans L, Otobo TM, Sudoł-Szopińska I, Meyers AB, et al. Atlas of MRI findings of sacroiliitis in pediatric sacroiliac joints to accompany the updated preliminary OMERACT pediatric JAMRIS (Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis MRI Score) scoring system: Part II: Structural damage lesions. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2021. Oct;51(5):1099–107.This article is the second part of the atlas. It highlights normal MRI findings and growth related structural changes of the sacroiliac joint in pediatrics. Additionally, goes through MRI identified structural lesions seen in active sacroiliitis that can be used as references.

- 30.Weiss PF, Brandon TG, Bohnsack J, Heshin-Bekenstein M, Francavilla ML, Jaremko JL, et al. Variability in Interpretation of Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Pediatric Sacroiliac Joint. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2021. Jun;73(6):841–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herregods N, Dehoorne J, Van den Bosch F, Jaremko JL, Van Vlaenderen J, Joos R, et al. ASAS definition for sacroiliitis on MRI in SpA: applicable to children? Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2017. Apr 11;15:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herregods N, Jans LBO, Chen M, Paschke J, De Buyser SL, Renson T, et al. Normal subchondral high T2 signal on MRI mimicking sacroiliitis in children: frequency, age distribution, and relationship to skeletal maturity. Eur Radiol 2021. May;31(5):3498–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burgos-Vargas R The assessment of the spondyloarthritis international society concept and criteria for the classification of axial spondyloarthritis and peripheral spondyloarthritis: A critical appraisal for the pediatric rheumatologist. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2012. May 31;10:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weber U, Jurik AG, Zejden A, Larsen E, Jørgensen SH, Rufibach K, et al. Frequency and Anatomic Distribution of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Features in the Sacroiliac Joints of Young Athletes: Exploring “Background Noise” Toward a Data-Driven Definition of Sacroiliitis in Early Spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018. May;70(5):736–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambert RGW, Bakker PAC, van der Heijde D, Weber U, Rudwaleit M, Hermann KG, et al. Defining active sacroiliitis on MRI for classification of axial spondyloarthritis: update by the ASAS MRI working group. Ann Rheum Dis 2016. Nov;75(11):1958–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Otobo TM, Herregods N, Jaremko JL, Sudol-Szopinska I, Maksymowych WP, Meyers AB, et al. Reliability of the Preliminary OMERACT Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis MRI Score (OMERACT JAMRIS-SIJ). Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021. Jan;10(19):4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.*Otobo TM, Herregods N, Jaremko JL, Sudol-Szopinska I, Maksymowych WP, Meyers AB, et al. Reliability of the Preliminary OMERACT Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis MRI Score (OMERACT JAMRIS-SIJ). J Clin Med 2021. Sep 30;10(19):4564.This study reports the reliability of the juvenile idiopathic arthritis magnetic resonance imaging scoring system (JAMRIS-SIJ). Eight physicians rated MRI imaging of patient with JSpA and the inter-rater agreement was evaluated. The BME and ankylosis scores had good inter-rater reliability. The study showed that further refinement of the scoring system is needed to decrease variability while not jeopardizing accuracy.

- 38.**Weiss PF, Brandon TG, Lambert RG, Biko DM, Chauvin NA, Francavilla ML, et al. Data-Driven Magnetic Resonance Imaging Definitions for Active and Structural Sacroiliac Joint Lesions in Juvenile Spondyloarthritis Typical of Axial Disease: A Cross-Sectional International Study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2022. Sep 5This study proposed and validated a data-driven quantitative definition for chronic structural lesions typical of JSpA. This quantitative definition in youth leveraged the JAMRIS-SIJ definitions of structural changes in youth. Positive MRI for structural lesions in youth with JSpA typical of axial disease was defined as structural lesion(s): erosion in ≥3 quadrants or sclerosis or fat lesion in ≥2 SIJ quadrants or backfill or ankylosis in ≥2 joint halves across all SIJ MRI slices (sensitivity 98.6%, specificity 95.5%).

- 39.Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Masi AT, Carreiro JE, Danneels L, Willard FH. The sacroiliac joint: an overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications. J Anat 2012. Dec;221(6):537–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.*Morbée L, Jans LBO, Herregods N. Novel imaging techniques for sacroiliac joint assessment. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2022. Jul 1;34(4):187–94.This article describes new imaging techniques that assess spondyloarthritis. It is a great review of innovative technology.

- 41.Apprich S, Welsch GH, Mamisch TC, Szomolanyi P, Mayerhoefer M, Pinker K, et al. Detection of degenerative cartilage disease: comparison of high-resolution morphological MR and quantitative T2 mapping at 3.0 Tesla. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010. Sep;18(9):1211–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albano D, Bignone R, Chianca V, Cuocolo R, Messina C, Sconfienza LM, et al. T2 mapping of the sacroiliac joints in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Eur J Radiol 2020. Oct;131:109246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.*Francavilla ML, Serai SD, Brandon TG, Biko DM, Khrichenko D, Nguyen JC, et al. Feasibility of T2 Mapping of the Sacroiliac Joints in Healthy Control Subjects and Children and Young Adults with Sacroiliitis. ACR Open Rheumatol 2022. Jan;4(1):74–82.T2-mapping has been shown to be feasible in adults with SpA and is promising at assessing axial disease. This study illustrated that in children and young adults, T2-maps showed longer T2 relaxation times in cases of sacroiliitis vs healthy controls, which is promising as a potential new way to assess for sacroiliitis in the pediatric population.

- 44.Baliyan V, Das CJ, Sharma R, Gupta AK. Diffusion weighted imaging: Technique and applications. World J Radiol 2016. Sep 28;8(9):785–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gezmis E, Donmez FY, Agildere M. Diagnosis of early sacroiliitis in seronegative spondyloarthropathies by DWI and correlation of clinical and laboratory findings with ADC values. European Journal of Radiology 2013. Dec;82(12):2316–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beltran LS, Samim M, Gyftopoulos S, Bruno MT, Petchprapa CN. Does the Addition of DWI to Fluid-Sensitive Conventional MRI of the Sacroiliac Joints Improve the Diagnosis of Sacroiliitis? American Journal of Roentgenology 2018. Jun;210(6):1309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bray T JP, Vendhan K, Ambrose N, Atkinson D, Punwani S, Fisher C, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging is a sensitive biomarker of response to biologic therapy in enthesitis-related arthritis. Rheumatology 2016. Dec 19;kew429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Vendhan K, Bray TJP, Atkinson D, Punwani S, Fisher C, Sen D, et al. A diffusion-based quantification technique for assessment of sacroiliitis in adolescents with enthesitis-related arthritis. BJR 2016. Mar;89(1059):20150775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bray TJP, Vendhan K, Roberts J, Atkinson D, Punwani S, Sen D, et al. Association of the apparent diffusion coefficient with maturity in adolescent sacroiliac joints: Association of ADC With Maturity in SIJ. J Magn Reson Imaging 2016. Sep;44(3):556–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu L, Leng S, McCollough CH. Dual-energy CT-based monochromatic imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012. Nov;199(5 Suppl):S9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu H, Zhang G, Shi L, Li X, Chen M, Huang X, et al. Axial Spondyloarthritis: Dual-Energy Virtual Noncalcium CT in the Detection of Bone Marrow Edema in the Sacroiliac Joints. Radiology 2019. Jan;290(1):157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]