Abstract

Background

Liver cirrhosis is associated with significant nutritional risks and poor survival rates. Little is known about the impact of dietary factors on metabolic complications and mortality from cirrhosis.

Aim

The present study investigated the potential associations between dietary fibers and the risk of cirrhosis-related mortality.

Methods

In this prospective study, 121 ambulatory cirrhotic patients with more than six months of cirrhosis diagnosis were followed-up for 4 years. Dietary intakes were assessed using a 168-item semi-quantitative validated food frequency questionnaire. Crude and multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated through cox proportional hazards regression models.

Results

Comparing the highest versus the lowest tertile, soluble and insoluble fiber intake was associated with 62% (HR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.045–3.5, p trend = 0.047) and 73% (HR = 0.27, 95% CI = 0.06–1.2, p trend = 0.021) lower mortality risk, respectively, after full adjustment for potential confounders. Higher intakes of total fiber were inversely but non-significantly associated with mortality risk.

Conclusion

Comprehensive assessment of dietary fiber intake associations with cirrhosis-related mortality showed that higher intakes of soluble and insoluble fiber were significantly associated with reduced mortality risk.

Keywords: Cirrhosis, Mortality, Soluble fiber, Insoluble fiber, Cohort study

1. Introduction

Liver cirrhosis is the final stage of chronic hepatic diseases, which is allied with a high rate of morbidity and mortality [1]. About two million deaths due to liver diseases are reported worldwide yearly, and more than one million of them are caused by liver cirrhosis [2,3]. The number of deaths, disability-adjusted life years and the proportion of all global deaths due to cirrhosis are increasing [4]. In Iran, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) project in 2017 showed that 1.42% of all deaths were caused by cirrhosis and other liver diseases [5].

Diet plays a vital role in the etiology of liver cirrhosis and dietary modification is easy to implement with little risk of side effects or cost, so it can be offered to all patients [1]. It also has proven effects in managing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which is known as the most common cause of cirrhosis [6]. Dietary fiber is widely recognized as an essential part of a healthy diet and has been cited in previous studies which had assessed the effects of nutrition on chronic liver diseases [[7], [8], [9]]. Depending on solubility, dietary fiber can be divided into water-soluble and water-insoluble fiber [10]. Soluble fibers consist of gelforming substances, such as pectins, gums, some hemicelluloses, mucilages, and storage polysaccharides and insoluble fibers consist of structural and/or matrix fibers such as cellulose, part of hemicellulose and lignin [11,12]. The main sources of soluble fiber are fruits, vegetables and oats [11] and insoluble fiber is generally found in whole grains, brans and vegetables [13].

Accumulating evidence indicated that dietary fiber might decrease the risks of obesity, dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia, which are leading causes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and subsequently liver cirrhosis [14,15]. Moreover, dietary fiber could act as a prebiotic through fermentation in the colon, especially soluble fibers, and provide many other health benefits [16]. Dietary fibers also are known to improve insulin sensitivity and have anti-inflammatory properties [17,18].

According to previous studies, higher fiber intake is associated with lower mortality, particularly from cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and inflammatory diseases [19,20]. However, little is known about the association of dietary fiber intake with cirrhosis-related mortality. In this study, we evaluated potential associations between dietary total, soluble and insoluble fibers with total mortality, using data from a prospective cohort study in cirrhotic patients.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Study population

In total, 166 ambulatory cirrhotic patients with more than six months of cirrhosis diagnosis were recruited in this cohort study from 2016 to 2018 and were followed up to 30 April 2022, from two educational hospitals in Tehran, Iran including Ayatollah Taleqani Hospital and Shariati Hospital which are respectively affiliated to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBMU), and Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TMUS). This cohort study was planned to follow up the participants for 4 years after enrollment. After entering the study, the patients were followed up annually. Participants received annual telephone calls during which follow-up questionnaires were completed regarding the occurrence of death or any medical event. At the end of 4 years, mortality and survival were determined.

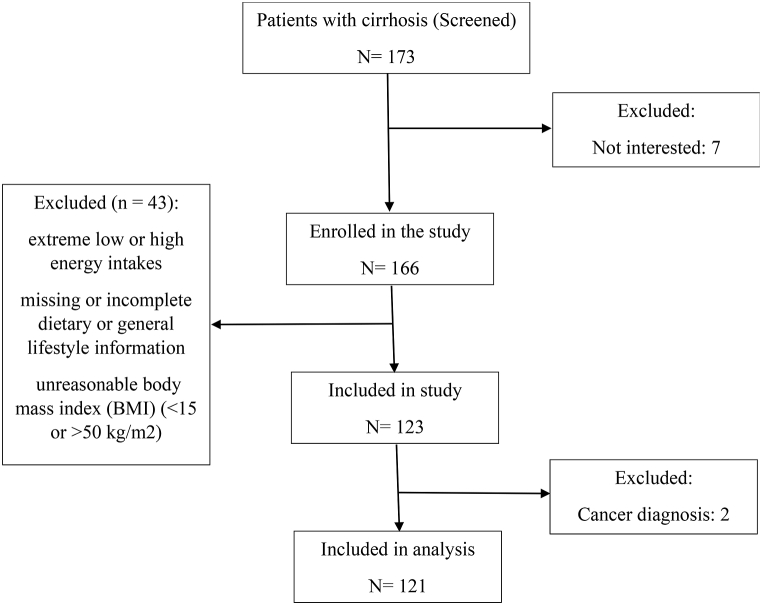

Exclusion criteria were: (1) being pregnant or lactating, (2) having diabetes mellitus, renal failure, chronic cardiac disease, malignancies, infectious disease, pancreatic insufficiency and acquired immune deficiency syndrome. We also excluded participants (n = 45) with extremely low or high energy intakes (<500 or >5000 kcal/day), diagnosis of cancer in the first year, missing or incomplete dietary or general lifestyle information, and those with an unreasonable body mass index (BMI) (<15 or >50 kg/m2). Protocol of this study was approved at National nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute (NNFTRI) ethics committee (Ir.sbmu.nnftri.1396.186). All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment. Finally, 121 participants (83 men and 38 women) were included in the analyses. The flow chart provides a description of the patients recruited and the sample sizes for analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participant recruitment.

2.2. Dietary assessment

At the time of enrollment, dietary intakes were collected through face-to-face interviews using a valid and reliable food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) with 168 items [21]. Typical portion sizes, frequency of consumption, and servings consumed each time for each food item were questioned. A daily, weekly or monthly intake of each food item was recorded and converted to grams using household measurements. The collected data were analyzed using Nutritionist IV software. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) food composition table (FCT) was used to calculate energy and nutrient contents. For traditional Iranian foods that were not provided by the USDA FCT, the Iranian food composition table was used. In addition to total fiber, the contents of insoluble and soluble fiber were calculated and expressed as grams per day.

2.3. Potential confounders

Basic characteristic data including age, sex, smoking and alcohol consumption, subjective global assessment tool (SGA), body mass index (BMI), etiology of cirrhosis, Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and Child-Pugh score were collected at the enrollment. In addition, each patient was weighed with minimal clothes, using a digital scale to the nearest 0.5 kg and height was measured without shoes, using a portable stadiometer to the nearest of 0.1 cm. Moreover, BMI was calculated by dividing the weight (in kilograms) by the square of the height (in meters). The nutritional status of each patient was estimated using the SGA based on Destky et al. study [22]. Based on this assessment, patients were divided into three categories: A: well-nourished, B: moderately malnourished and C: severely malnourished.

MELD and Child-Pugh scores were used to evaluate the prognosis and severity of liver cirrhosis. The MELD score was calculated by formula 9.57 × Ln (creatinine, mg/dl) + 3.78 × Ln (total bilirubin, mg/dl) + 11.2 × Ln (INR) + 6.43 [23]. Child-Pugh score was calculated which included the presence of ascites, encephalopathy, albumin, prothrombin time and serum bilirubin and patients were classified into three categories of A, B and C.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Participants were divided into three groups based on their dietary fiber intake. The basic characteristics of participants were compared among the tertiles of total dietary fiber using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test for continuous variables and the chi-squared (χ2) test for categorical variables. Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated through cox proportional hazards regression models for all-cause mortality associated with the dietary total fiber, soluble fiber and insoluble fiber tertiles. Potential confounders, added in a following series: Model 1: adjusted for age (continuous), and sex (male, female); Model 2: additionally adjusted for energy intake (continuous), BMI (continuous), smoking (yes, no), and alcohol using (yes, no); and Model 3: additionally adjusted for etiology (virus, autoimmune, other), MELD (continuous) and Child-Pugh (A, B & C).

Potential interactions between major risk factors at baseline, including BMI, age, SGA, MELD and Child-Pugh and dietary intakes of total, soluble and insoluble fiber in relation to risk of mortality were tested using the likelihood ratio test (LRT). Person-years of follow-up was considered from the date of enrollment until the date of death, lost to follow-up or censoring on 30 April 2022, whichever occurred first. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 19; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and significance level was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results

The mean age ± standard deviation (SD) of participants at baseline was 54.8 ± 11.9 years. Overall, 31.4% were women and the etiology of cirrhosis in 52.9% of patients was viral hepatitis. During 3955 person-month of follow-up, we documented 43 deaths (7 women, 36 men). Liver failure was responsible for 47% of deaths, cardiovascular diseases 40%, carcinoma 3% and other causes for 10% of deaths.

The mean of total calorie and daily fiber intake of patients was 1900 kcal and 15 g, respectively. The average intake of soluble and insoluble fiber was estimated to be about 8 and 7 g, respectively. The average BMI of the patients was estimated to be 27 kg/m2 and 37, 38 and 25% of them were normal, overweight and obese respectively. Also, alcohol consumption in 22% and smoking in 39% of patients were reported. The baseline characteristics of the participants according to the total dietary fiber tertiles are shown in Table 1. Viral hepatitis was found to be the main cause of liver cirrhosis in patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants according to the fiber intake tertile.

| Tertile of total fiber intake |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | P value | |

| Men, % | 68.3 | 57.5 | 80 | 0.095 |

| Age (y) | 54 ± 12 | 55 ± 13 | 56 ± 9 | 0.735 |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | 0.028 | |||

| Virus | 52.5 | 54.1 | 62.2 | |

| Autoimmune | 40 | 37.8 | 13.5 | |

| Other | 7.5 | 8.1 | 24.3 | |

| MELD score | 12.4 ± 5 | 12.7 ± 5 | 11.4 ± 4 | 0.527 |

| Child Pugh category (A/B/C) | % | 0.566 | ||

| A | 60.7 | 70.6 | 73 | |

| B, C | 39.3 | 29.4 | 32.3 | |

| Alcohol drinker | 18.9 | 17.9 | 33.3 | 0.202 |

| Smoker, % | 44.7 | 32.5 | 43.6 | 0.473 |

| Weight, kg | 70.3 ± 17.8 | 72.7 ± 14.2 | 78.7 ± 16.3 | 0.058 |

| Height, cm | 164.7 ± 7.7 | 163.8 ± 8.7 | 167.5 ± 8.1 | 0.113 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.9 ± 5.6 | 27.3 ± 5 | 28.2 ± 5.1 | 0.149 |

| Subjective global assessment | 0.028 | |||

| A | 14.6 | 35 | 47.5 | |

| B | 65.9 | 50 | 45 | |

| C | 19.5 | 15 | 7.5 | |

| Calorie intake (Kcal/day) | 1718 ± 626 | 1956 ± 518 | 2140 ± 601 | 0.049 |

| Total fiber intake (g/day) | 11.7 ± 3 | 16.8 ± 4 | 18.7 ± 4 | <0.001 |

| Insoluble fiber intake (g/day) | 6.1 ± 3.1 | 9 ± 4.2 | 10.1 ± 3.6 | <0.001 |

| Soluble fiber intake (g/day) | 5.5 ± 2.8 | 7.6 ± 3.5 | 8.8 ± 4.2 | <0.001 |

Values are means ± SDs for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables.

ANOVA for quantitative variables and χ2 test for qualitative variables.

Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all-cause mortality associated with dietary fiber intake are shown in Table 2. Total fiber intake was inversely but non-significantly associated with risk of mortality. The risk of all-cause mortality was lower in patients in the last tertile (T3) of soluble fiber intake (HR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.04–3.5, p trend = 0.047) in comparison with those in the first tertile (T1), after adjustment for all confounders. Similar results were achieved in the analysis of insoluble fiber. Higher intakes of insoluble fiber were associated with a lower risk of mortality in both model 2 (HR = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.07–1.4, p trend = 0.024) and model 3 (HR = 0.27, 95% CI = 0.06–1.2, p trend = 0.021). Dietary intakes of total, soluble and insoluble fiber were not significantly associated with mortality risk in the age- and sex-adjusted models.

Table 2.

Hazard ratios for total mortality, according to the fiber intake tertile.

| Tertiles of fiber intake |

P trend |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total fiber | ||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | ||

| No. of deaths | 19 | 13 | 11 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.42 (0.07–2.62) | 0.52 (0.04–7.5) | 0.264 |

| Model 2 | ref | 0.64 (0.25–1.62) | 0.41 (0.1–1.3) | 0.123 |

| Model 3 |

ref |

0.67 (0.23–1.98) |

0.37 (0.07–1.85) |

0.071 |

| Soluble fiber | ||||

| T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

||

| No. of deaths | 24 | 11 | 8 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.81 (0.26–2.47) | 0.5 (0.17–1.4) | 0.089 |

| Model 2 | ref | 0.49 (0.2–1.2) | 0.32 (0.09–1.09) | 0.060 |

| Model 3 |

ref |

0.69 (0.1–5.07) |

0.38 (0.04–3.5) |

0.047 |

| Insoluble fiber | ||||

| T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

||

| No. of deaths | 22 | 12 | 9 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.65 (0.11–3.92) | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) | 0.083 |

| Model 2 | ref | 0.45 (0.16–1.23) | 0.31 (0.07–1.4) | 0.024 |

| Model 3 | ref | 0.41 (0.16–1.05) | 0.27 (0.06–1.2) | 0.021 |

Cox proportional hazards regression models for estimating HRs and 95% CIs.

Model 1: adjusted for age and sex.

Model 2: additionally adjusted for energy intake, BMI, smoking and alcohol

Model 3: additionally adjusted for etiology, MELD and child.

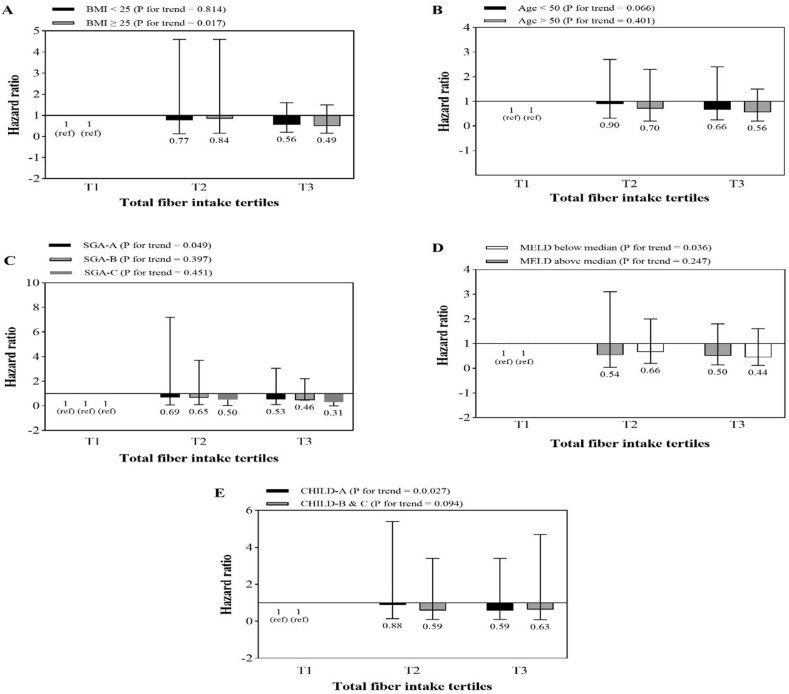

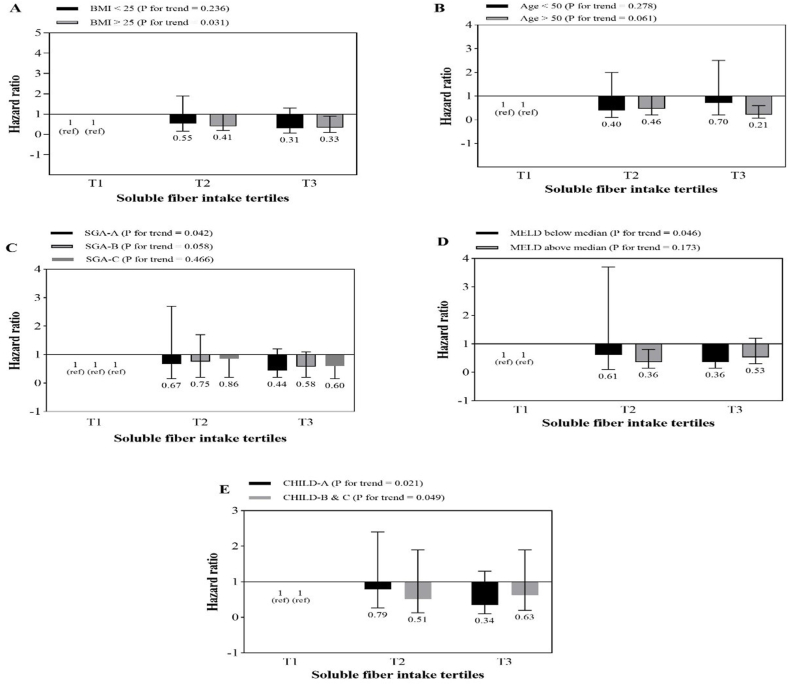

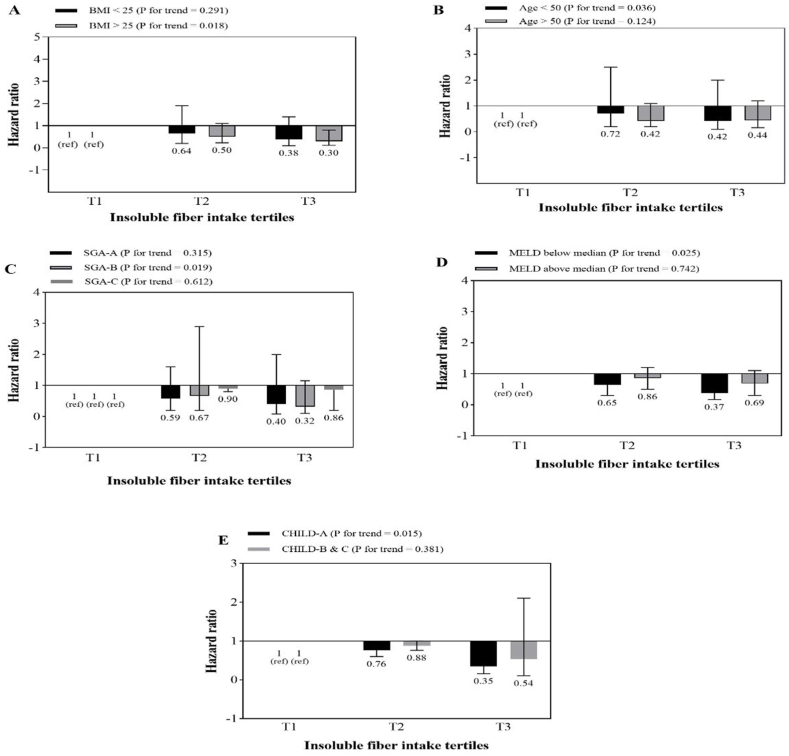

The association between total fiber intake and mortality risk according to BMI, age, SGA, MELD and Child-Pugh stratification is shown in Fig. 2. A similar analysis for soluble and insoluble fiber are shown in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, respectively. The results showed that higher intakes of dietary fiber, including total, soluble and insoluble fiber, were significantly associated with a lower risk of total mortality in patients who were obese or overweight (BMI≥ 25), those with MELD scores above the median (>11), and those who were in the first category of Child-Pugh (A). Also, with an increase in insoluble fiber intake, the risk of mortality in patients under 50 compared to those over 50 years old showed a significant decrease (p = 0.036).

Fig. 2.

Multivariate hazard ratios of total fiber intake tertiles for cirrhosis-related mortality according to risk factor status at baseline (Cox proportional hazards regression models for estimating HRs and 95% CIs, multivariable models were adjusted for sex, age, energy intake, BMI, smoking, alcohol, etiology, MELD and child, except for the respective stratifying factor). Data are reported as HR (95% CI).

A, BMI<25 vs ≥ 30 (P = 0.011 for interaction); B, age <50 years vs ≥ 50 years (P = 0.01 for interaction); C, SGA A vs B and C (P = 0.021 for interaction); D, MELD score below median vs above median (P < 0.001 for interaction); E, Child Pugh A vs B&C (P = 0.001 for interaction).

Fig. 3.

Multivariate hazard ratios of soluble fiber intake tertiles for cirrhosis-related mortality according to risk factor status at baseline (Cox proportional hazards regression models for estimating HRs and 95% CIs, multivariable models were adjusted for sex, age, energy intake, BMI, smoking, alcohol, etiology, MELD and child, except for the respective stratifying factor). Data are reported as HR (95% CI).

Fig. 4.

Multivariate hazard ratios of insoluble fiber intake tertiles for cirrhosis-related mortality according to risk factor status at baseline (Cox proportional hazards regression models for estimating HRs and 95% CIs, multivariable models were adjusted for sex, age, energy intake, BMI, smoking, alcohol, etiology, MELD and child, except for the respective stratifying factor). Data are reported as HR (95% CI).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the association of dietary total, soluble and insoluble fiber intake with the risk of mortality in cirrhotic patients has not been investigated yet. Comparing the highest versus the lowest tertile in the present cohort study showed that soluble and insoluble fiber intake was associated with 62% and 73% lower mortality risk, respectively, after full adjustment for potential confounders. Higher intakes of total fiber were inversely but non-significantly associated with the risk of mortality.

A meta-analysis study reported an inverse association between higher dietary fiber intake and all-cause mortality risk [24]. Similarly, the results of a recently published cohort study indicated an inverse association between fiber intake and the risk of mortality from chronic liver diseases, including cirrhosis [7]. The National Institutes of Health–American Association of Retired Persons Diet and Health Study cohort (993 deaths from chronic liver disease) reported an inverse association between dietary fiber intakes and chronic liver disease mortality (HRQ5 vs. Q1 = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.29–0.48) [7].

The biological mechanisms for the inverse associations of dietary fiber with cirrhosis remain to be fully elucidated. The imbalance of the intestinal microbiome has been proposed as one of the possible mechanisms in the pathophysiology of cirrhosis [25,26]. This effect might be attributed to the increased production of endotoxins or lipopolysaccharides by pathogenic bacteria (e.g., Enterobacteriaceae), which can impair intestinal integrity and exacerbate inflammation in the liver [27]. Dietary fibers, as prebiotics, can reduce liver oxidative stress and inflammation by improving intestinal dysbiosis and tight junction integrity. Prebiotics can normalize plasma endotoxin concentrations by stimulating the growth of Gram-positive bacteria such as Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus and inhibiting the endotoxemic Gram-negative bacteria [28].

In addition, dietary fibers can also prevent cirrhosis by ameliorating NAFLD, one of the most important causes of cirrhosis. A 20-year multiethnic cohort with 2974 NAFLD cases and 29,474 matched controls reported an inverse significant association between total dietary fiber and risk of NAFLD (OR = 0.84; P = 0.003) [29]. In accordance, a large Chinese cross-sectional study showed that higher intakes of insoluble fiber were associated with a lower prevalence of newly-diagnosed NAFLD in men (OR = 0.60; P < 0.001) [30]. However, this study failed to show this association for soluble fiber. As a result of the fermentation of dietary fibers by gut bacteria, short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) are produced, which have been revealed to play a role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD [31]. It has also been demonstrated that SCFAs may suppress inflammation and lipid peroxidation [31]. Other potential mechanisms of dietary fibers that have been proposed in prevention and treatment of fatty liver are as follows: (1) reducing carbohydrate and fat absorption, (2) enhancing glycemic control (3) improving insulin sensitivity, (4) lipid-lowering effects and (5) reducing weight and adiposity [32,33]. The beneficial effects of dietary fiber in reducing encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients have also been reported in few studies [34,35]. This could be another explanation for the association of dietary fiber with reduced cirrhosis-related mortality. More investigation is needed to further clarify the potential mechanisms.

Investigating the association of fiber, separately by solubility, with the risk of cirrhosis-related mortality is one of the strengths of present cohort study. Prospective cohort design with 4-year follow-up in evaluating this association is another strength. Moreover, all potential confounders were considered in the analyses. Also, in this study, the relationship between total fiber intake and mortality risk was measured based on BMI, age, SGA, MELD and Child-Pugh classification. Our study also has some limitations. First, the study population was relatively small, limiting the precision of our effect estimates, therefore, results should be interpreted with caution, and confirmation from larger studies is warranted. Second, the use of FFQ is inevitably allied with recall bias and patients may over-report as well as underreport dietary intake. Third, about 15% of the enrolled patients were missing. Furthermore, as in many epidemiological studies, we cannot rule out that the results are partially biased by residual and unmeasured confounders and loss to follow-up. Conducting clinical trials in these patients to compare the difference in complications and mortality will add strength to this study.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, we found significant inverse associations between soluble and insoluble dietary fiber intake with mortality in cirrhotic patients. Further studies are recommended to determine the effectiveness and the appropriate amount of fiber, including total, soluble and insoluble, in cirrhotic patients.

Author contribution statement

Zahra Hariri: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Azita Hekmatdoost: Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Fereshteh Pashayee-khamene: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Sara Karimi, Salehe Ahmadzadeh: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Zahra Yari: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Sources of support

No funding has been received for this study.

Author declarations

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper

Acknowledgements

Authors have no acknowledgments to declare.

References

- 1.Wiegand J., Berg T. The etiology, diagnosis and prevention of liver cirrhosis: part 1 of a series on liver cirrhosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110(6):85–91. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuppan D., Afdhal N.H. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2008;371(9615):838–851. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60383-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mokdad A.A., et al. Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):1–24. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0145-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sepanlou S.G., et al. The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;5(3):245–266. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30349-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anushiravani A., Ghajarieh Sepanlou S. Burden of liver diseases: a review from Iran. Middle East J. Dig. Dis. 2019;11(4):189–191. doi: 10.15171/mejdd.2019.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berna G., Romero-Gomez M. The role of nutrition in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: pathophysiology and management. Liver Int. 2020;40(Suppl 1):102–108. doi: 10.1111/liv.14360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X., et al. Higher intake of whole grains and dietary fiber are associated with lower risk of liver cancer and chronic liver disease mortality. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):6388. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26448-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zolfaghari H., et al. Intake of nutrients, fiber, and sugar in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in comparison to healthy individuals. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2016;7:98. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.188083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao H., et al. Association between dietary fiber intake and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. Front. Nutr. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.593735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams B.A., et al. Gut fermentation of dietary fibres: physico-chemistry of plant cell walls and implications for health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18(10):2203. doi: 10.3390/ijms18102203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chawla R., Patil G. Soluble dietary fiber. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2010;9(2):178–196. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner N.D., Lupton J.R. Dietary fiber. Adv. Nutr. 2011;2(2):151–152. doi: 10.3945/an.110.000281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreher M.L. Handbook of Dietary Fiber. CRC Press; 2001. Dietary fiber overview; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Agroudy N.N., et al. Are lifestyle therapies effective for NAFLD treatment? Trends Endocrinol. Metabol. 2019;30(10):701–709. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2019.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim E.J., et al. Cholesterol-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and atherosclerosis aggravated by systemic inflammation. PLoS One. 2014;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slavin J. Fiber and prebiotics: mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients. 2013;5(4):1417–1435. doi: 10.3390/nu5041417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiller G.A. CRC press; 2001. CRC Handbook of Dietary Fiber in Human Nutrition. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson J.W., et al. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr. Rev. 2009;67(4):188–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chuang S.-C., et al. Fiber intake and total and cause-specific mortality in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012;96(1):164–174. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.028415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim Y., Je Y. Dietary fiber intake and total mortality: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014;180(6):565–573. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mirmiran P., et al. Reliability and relative validity of an FFQ for nutrients in the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Publ. Health Nutr. 2010;13(5):654–662. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009991698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Detsky A.S., et al. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 1987;11(1):8–13. doi: 10.1177/014860718701100108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malinchoc M., et al. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 2000;31(4):864–871. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y., et al. Association between dietary fiber and lower risk of all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015;181(2):83–91. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y., et al. Characterization of fecal microbial communities in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;54(2):562–572. doi: 10.1002/hep.24423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee N.Y., Suk K.T. The role of the gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;22(1):199. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Betrapally N.S., Gillevet P.M., Bajaj J.S. Gut microbiome and liver disease. Transl. Res. 2017;179:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho M.S., et al. Modulation of gut microbiome in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: pro-, pre-, syn-, and antibiotics. J. Microbiol. 2018;56(12):855–867. doi: 10.1007/s12275-018-8346-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noureddin M., et al. Diet associations with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in an ethnically diverse population: the multiethnic cohort. Hepatology. 2020;71(6):1940–1952. doi: 10.1002/hep.30967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia Y., et al. Insoluble dietary fibre intake is associated with lower prevalence of newly-diagnosed non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Chinese men: a large population-based cross-sectional study. Nutr. Metabol. 2020;17(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12986-019-0420-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu H., et al. Small metabolites, possible big changes: a microbiota-centered view of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2019;68(2):359–370. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nie Y., Luo F. Dietary fiber: an opportunity for a global control of hyperlipidemia. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/5542342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lovegrove A., et al. Role of polysaccharides in food, digestion, and health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017;57(2):237–253. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2014.939263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malaguarnera M., et al. Bifidobacterium combined with fructo-oligosaccharide versus lactulose in the treatment of patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010;22(2):199–206. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328330a8d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Birkett A., et al. Resistant starch lowers fecal concentrations of ammonia and phenols in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1996;63(5):766–772. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.5.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.