Abstract

Background

Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most frequently prescribed medications worldwide and are widely used for patients with low‐back pain. Selective COX‐2 inhibitors are currently available and used for patients with low‐back pain.

Objectives

The objective was to assess the effects of NSAIDs and COX‐2 inhibitors in the treatment of non‐specific low‐back pain and to assess which type of NSAID is most effective.

Search methods

We searched the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials up to and including June 2007 if reported in English, Dutch or German. We also screened references given in relevant reviews and identified trials.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials and double‐blind controlled trials of NSAIDs in non‐specific low‐back pain with or without sciatica were included.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed methodological quality. All studies were also assessed on clinical relevance, from which no further interpretations or conclusions were drawn. If data were considered clinically homogeneous, a meta‐analysis was performed. If data were lacking for clinically homogeneous trials, a qualitative analysis was performed using a rating system with four levels of evidence (strong, moderate, limited, no evidence).

Main results

In total, 65 trials (total number of patients = 11,237) were included in this review. Twenty‐eight trials (42%) were considered high quality. Statistically significant effects were found in favour of NSAIDs compared to placebo, but at the cost of statistically significant more side effects. There is moderate evidence that NSAIDs are not more effective than paracetamol for acute low‐back pain, but paracetamol had fewer side effects. There is moderate evidence that NSAIDs are not more effective than other drugs for acute low‐back pain. There is strong evidence that various types of NSAIDs, including COX‐2 NSAIDs, are equally effective for acute low‐back pain. COX‐2 NSAIDs had statistically significantly fewer side‐effects than traditional NSAIDs.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence from the 65 trials included in this review suggests that NSAIDs are effective for short‐term symptomatic relief in patients with acute and chronic low‐back pain without sciatica. However, effect sizes are small. Furthermore, there does not seem to be a specific type of NSAID which is clearly more effective than others. The selective COX‐2 inhibitors showed fewer side effects compared to traditional NSAIDs in the RCTs included in this review. However, recent studies have shown that COX‐2 inhibitors are associated with increased cardiovascular risks in specific patient populations.

Plain language summary

Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for low‐back pain

Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most frequently prescribed medications worldwide and are commonly used for treating low‐back pain. This review found 65 studies (including over 11,000 patients) of mixed methodological quality that compared various NSAIDs with placebo (an inactive substance that has no treatment value), other drugs, other therapies and with other NSAIDs. The review authors conclude that NSAIDs are slightly effective for short‐term symptomatic relief in patients with acute and chronic low‐back pain without sciatica (pain and tingling radiating down the leg). In patients with acute sciatica, no difference in effect between NSAIDs and placebo was found.

The review authors also found that NSAIDs are not more effective than other drugs (paracetamol/acetaminophen, narcotic analgesics, and muscle relaxants). Placebo and paracetamol/acetaminophen had fewer side effects than NSAIDs, though the latter has fewer side effects than muscle relaxants and narcotic analgesics. The new COX‐2 NSAIDs do not seem to be more effective than traditional NSAIDs, but are associated with fewer side effects, particularly stomach ulcers. However, other literature has shown that some COX‐2 NSAIDs are associated with increased cardiovascular risk.

The review noted a number of limitations in the studies. Only 42% of the studies were considered to be of high quality. Many of the studies had small numbers of patients, which limits the ability to detect differences between the NSAID and the control group. There are few data on long term results and long‐term side effects.

Background

Low‐back pain is a major health problem among populations in western industrialized countries and a major cause of medical expenses, absenteeism and disablement (Deyo 1991; van Tulder 1995). Although low‐back pain is usually a benign and self‐limiting disease which tends to improve spontaneously over time (Waddell 1987), a wide variety of therapeutic interventions is available for treatment (Deyo 1987; Spitzer 1987; van Tulder 1997). However, the effectiveness of most of these interventions has not yet been demonstrated beyond doubt and consequently, the therapeutic management of low‐back pain varies widely. A major challenge for researchers is to provide evidence of which treatment, if any, is of most benefit for (sub‐groups of) patients with low‐back pain.

Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most frequently prescribed medications worldwide and are widely used for patients with low‐back pain. The rationale for the treatment of low‐back pain with NSAIDs is based both on their analgesic potential and their anti‐inflammatory action.

Guidelines for the management of low‐back pain in primary care have been published in various countries around the world (Airaksinen 2006; Koes 2001; Koes 2006; van Tulder 2006). All these guidelines recommend the prescription of NSAIDs as one option for symptomatic relief in the management of low‐back pain. In most guidelines, NSAIDs are recommended as a treatment option after paracetamol has been tried. In addition to symptomatic relief, facilitating early return to normal activities is a goal of NSAID therapy.

In recent years, the selective cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) inhibiting NSAIDs have become available as an alternative to traditional NSAIDs. The putative advantage of the COX‐2 inhibitors is lower risk of gastro‐intestinal side effects as compared with the traditional NSAIDs. However, recently there has been substantial debate on their cardiovascular safety. A few randomised clinical trials have evaluated the efficacy of selective COX‐2 inhibitors for low‐back pain and will be included in this updated systematic review.

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review was to determine if NSAIDs are more efficacious than various comparison treatments for non‐specific low‐back pain and if so, which type of NSAID is most efficacious.

Comparisons of NSAIDs with reference treatments that were investigated are NSAIDs versus placebo, NSAIDs versus acetaminophen/paracetamol, NSAIDs versus other drugs (e.g. narcotic analgesics or muscle relaxants), NSAIDs versus NSAIDs (e.g. traditional NSAIDs versus selective COX‐2 inhibitors), NSAIDs versus NSAIDs plus muscle relaxant, NSAIDs versus NSAIDs plus B vitamins, and NSAIDs versus non‐drug treatment.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised trials (double‐blind, single‐blind and open‐label) and double‐blind controlled trials were included.

Types of participants

Subjects age 18 years or older, treated for non‐specific low‐back pain with or without sciatica, were included. Subjects with specific low‐back pain caused by pathological entities such as infection, neoplasm, metastasis, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or fractures were excluded. Both acute (12 weeks or less) and chronic (more than 12 weeks) low‐back pain patients were included.

Types of interventions

One or more types of NSAIDs were included. Additional interventions were allowed if there was a contrast for NSAIDs in the study. For example, studies comparing NSAIDs plus muscle relaxants versus muscle relaxants alone were included, while studies comparing NSAIDs plus muscle relaxants versus paracetamol were not.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome measures were (in hierarchical order): 1) pain intensity (e.g. Visual Analog Scale or Numerical Rating Scale), 2) global measure (e.g. overall improvement, proportion of patients recovered), 3) back pain‐specific functional status (e.g. Roland Disability Questionnaire, Oswestry Scale), 4) return to work (e.g. return to work status, number of days off work), and 5) side effects (proportion of patients experiencing side effects). Physiological outcomes (e.g. range of motion, spinal flexibility, degrees of straight leg raising or muscle strength) and generic functional status (e.g. SF‐36, Nottingham Health Profile, Sickness Impact Profile) were considered secondary outcomes. Other symptoms such as health care consumption were also considered.

Search methods for identification of studies

All relevant RCTs meeting our inclusion criteria were identified by: A) a computer‐aided search of the MEDLINE (from 1966 to June 2007) and EMBASE (from 1988 to June 2007) databases using the search strategy recommended by the Cochrane Back Review Group (van Tulder 2003). RCTs published in English, Dutch and German were included because the review authors who conducted the methodological quality assessment and data extraction were able to read papers published in these languages. B) a search in CENTRAL, the Cochrane Library 2007, issue 2. C) screening references given in relevant reviews and identified RCTs.

The intervention specific search contained MeSH‐headings (explode 'anti‐inflammatory agents, non‐steroidal') and textwords in title, keywords and abstracts ('nsaid', 'non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug'). The complete search strategy is presented in Appendix 1; Appendix 2; and Appendix 3.

Data collection and analysis

Study selection

Two review authors independently selected the trials to be included in the systematic review according to the inclusion criteria. Consensus was used to resolve disagreements concerning inclusion of RCTs.

Methodologic quality assessment

The criteria list recommended by the Cochrane Back Review Group (Table 1) was used for assessing the methodological quality of the included studies (van Tulder 2003). All items were scored as positive or negative. Unclear scores were not included, because we had decided not to contact the authors for additional information.

1. Operationalisation Quality Assessment.

| Criteria | Operationalisation |

| A. Was the method of randomisation adequate? | A random (unpredictable) assignment sequence. Examples of adequate methods are computer‐generated random numbers table and use of sealed opaque envelopes. Methods of allocation using date of birth, date of admission, hospital numbers, or alternation should not be regarded as appropriate. |

| B. Was the treatment allocation concealed? | Assignment generated by an independent person not responsible for determining the eligibility of the patients. This person has no information about the persons included in the trial and has no influence on the assignment sequence or on the decision about eligibility of the patient. |

| C. Were the groups similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators? | In order to receive a "yes," groups have to be similar at baseline regarding demographic factors, duration and severity of complaints, percentage of patients with neurological symptoms, and value of main outcome measure(s). |

| D. Was the patient blinded to the intervention? | The review author determines if enough information about the blinding is given in order to score a "yes." |

| E. Was the care provider blinded to the intervention? | The review author determines if enough information about the blinding is given in order to score a "yes." |

| F. Was the outcome assessor blinded to the intervention? | The review author determines if enough information about the blinding is given in order to score a "yes." |

| G. Were co‐interventions avoided or similar? | Co‐interventions should either be avoided in the trial design or be similar between the index and control groups. |

| H. Was the compliance acceptable in all groups? | The review author determines if the compliance to the interventions is acceptable, based on the reported intensity, duration, number and frequency of sessions for both the index intervention and control intervention(s). |

| I. Was the drop‐out rate described and acceptable? | The number of participants who were included in the study but did not complete the observation period or were not included in the analysis must be described and reasons given. If the percentage of withdrawals and drop‐outs does not exceed 20% for immediate and short‐term follow‐ups, 30% for intermediate and long‐term follow‐ups and does not lead to substantial bias a "yes" is scored. |

| J. Was the timing of the outcome assessment in all groups similar? | Timing of outcome assessment should be identical for all intervention groups and for all important outcome assessments. |

| K. Did the analysis include an intention‐to‐treat analysis? | All randomized patients are reported/analyzed in the group to which they were allocated by randomization for the most important moments of effect measurement (minus missing values), irrespective of noncompliance and co‐interventions. |

The methodologic quality of the RCTs was independently assessed by two review authors. Consensus was used to resolve disagreements and a third review author was consulted if disagreements persisted. If the article did not contain information on the methodologic criteria, these criteria were scored as 'negative'. Because 31 of the 64 studies included in this review were published before 1990, we decided not to contact the authors for additional information.

We defined high quality studies as RCTs which fulfilled six or more of the validity criteria, but also performed sensitivity analyses exploring the results when high quality was defined as fulfilling five or more or seven or more of the 11 validity criteria. We also explored the results if high quality was defined as having adequate concealment of treatment allocation. Analyses were performed separately for traditional NSAIDs and selective COX‐2 NSAIDs, (sub)acute low‐back pain (12 weeks or less) and chronic low‐back pain (more than 12 weeks), short‐term follow‐up (less than six months after randomization) and long‐term follow‐up (six months or more), and low‐back pain with and without sciatica.

Data extraction

Two review authors independently extracted the data (using a standardized form). Data were extracted on type and dose of NSAIDs, type of reference treatment, follow‐up, presence or absence of sciatica, duration of current symptoms, and the outcomes described above.

Data analysis

The quantitative analysis (statistical pooling) was limited to clinically homogeneous studies for which the study populations, interventions and outcomes were considered by the review authors to be similar (see comparisons). We included a test for homogeneity of the Relative Risk (RR) of the RCTs. If studies were clinically and statistically homogeneous, Mean Differences, RRs and 95% CI were presented using the fixed‐effect model. If studies were clinically homogeneous but statistically heterogeneous, the random‐effects model was used. For Mean Differences, the Weighted Mean Difference (WMD) was presented if all studies reported an identical scale for an outcome measure (e.g. 100 mm VAS for Pain Intensity); otherwise the Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) was presented (e.g. 100 mm VAS and 5‐point scale for Pain Intensity).

A qualitative analysis was performed if relevant data enabling statistical pooling were lacking. In the qualitative analysis, a rating system of levels of evidence was used to summarize the results of the studies in terms of strength of the scientific evidence. The rating system consisted of four levels of scientific evidence based on the quality and the outcome of the studies: ‐ Strong evidence ‐ consistent findings among multiple high quality RCTs ‐ Moderate evidence ‐ consistent findings among multiple low quality RCTs and/or one high quality RCT ‐ Limited evidence ‐ one low quality RCT ‐ Conflicting evidence ‐ inconsistent findings among multiple RCTs ‐ No evidence from trials ‐ no RCTs or CCTs

Clinical relevance

In order to give an indication for clinical relevance, all included studies were checked on the following criteria (Shekelle 1994):

Are the patients described in detail so that you can decide whether they are comparable to those that you see in your practice?

Are the interventions and treatment settings described well enough so that you can provide the same for your patients?

Were all clinically relevant outcomes measured and reported?

Is the size of the effect clinically important? (van der Roer 2006)

Are the likely treatment benefits worth the potential harms?

Note that when studies comparing two or more medications determined that the medications were equally effective, the effects were considered negative with respect to the effectiveness of the intervention medication. All scores were added to the Characteristics of included studies Table, but no further conclusions were drawn from these results.

Results

Description of studies

The updated search resulted in 125 additional references from MEDLINE, 566 from EMBASE and 55 from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. After filtering for duplicates, 467 references were left for assessment. During the first selection based on titles, keywords and abstracts, the two review authors agreed that 23 articles should be included, they were uncertain about five studies and rejected 439 studies. Assessment of the 28 full papers resulted in four more studies being rejected. One study reported on two trials (Dreiser 2001) and therefore this reference is listed twice. Six studies that had been included earlier in the review were also rejected, as two of these papers only described the onset of pain relief (Katz 2004, Veenema 2000), and four papers did not meet language criteria (Arslan 1999; Hong 2006; Kittang 2001; Natour 2002). Three papers were considered to contain additional information for earlier reported studies (Lloyd 2004; Nadler 2003; Pallay 2004).

Consequently, 15 new studies were included.

The previous search had resulted in 53 selected studies for this review. Three of these studies were excluded, one of them because the efficacy of a muscle relaxant instead of an NSAID was evaluated (Berry 1988b), the second only investigated different dosage regimes of the same NSAID (Pownall 1985) and the third because the study population consisted of back and neck pain patients (Coletta 1988).

Finally, 65 studies were included in this update, 59 of which were published in English and six in German:

sixteen studies compared one or more types of NSAIDs with a placebo (Amlie 1987; Babej‐Dolle 1994; Basmajian 1989; Berry 1982; Birbara 2003; Coats 2004; Dreiser 2001; Dreiser 2003; Goldie 1968; Jacobs 1968; Katz 2003; Lacey 1984; Radin 1968; Szpalski 1994; Weber 1980; Weber 1993);

seven studies compared one or more types of NSAIDs with paracetamol (Evans 1980; Hickey 1982; Innes 1998; Milgrom 1993; Muckle 1986; Nadler 2002; Wiesel 1980);

nine studies compared one or more types of NSAIDs to other drugs (Basmajian 1989; Braun 1982; Brown 1986; Chrubasik 2003; Evans 1980; Ingpen 1969; Metscher 2001; Sweetman 1987; Videman 1984a);

four studies compared some type of NSAIDs with non‐drug treatment (Nadler 2002; Postacchini 1988; Szpalski 1990; Waterworth 1985);

33 studies compared different types of NSAIDs (Aghababian 1986; Agrifoglio 1994; Aoki 1983; Babej‐Dolle 1994; Bakshi 1994; Berry 1982; Blazek 1986; Colberg 1996; Davoli 1989; Dreiser 2001b; Dreiser 2003; Driessens 1994; Evans 1980; Famaey 1998; Hingorani 1970; Hingorani 1975; Hosie 1993; Jaffe 1974; Listrat 1990; Matsumo 1991; Orava 1986; Pena 1990; Pohjolainen 2000; Schattenkirchner2003; Siegmeth 1978; Stratz 1990; Videman 1984b; Waikakul 1995; Waikakul 1996; Wiesel 1980; Ximenes 2007; Yakhno 2006; Zerbini 2005);

three studies compared NSAIDs with NSAIDs plus muscle relaxants (Basmajian 1989; Berry 1988b; Borenstein 1990); and

three studies compared NSAIDs with NSAIDs plus B vitamins (Bruggemann 1990; Kuhlwein 1990; Vetter 1988).

Twenty‐five studies included a homogeneous population of low‐back pain patients without sciatica (Agrifoglio 1994; Amlie 1987; Birbara 2003; Borenstein 1990; Chrubasik 2003; Coats 2004; Colberg 1996; Dreiser 2003; Driessens 1994; Famaey 1998; Hosie 1993; Ingpen 1969; Innes 1998; Katz 2003; Metscher 2001; Milgrom 1993; Nadler 2002; Orava 1986; Pohjolainen 2000; Schattenkirchner2003; Sweetman 1987; Szpalski 1994; Waterworth 1985; Wiesel 1980; Zerbini 2005); six studies included a homogeneous population of low‐back pain patients with sciatica (Braun 1982; Dreiser 2001; Goldie 1968; Radin 1968; Weber 1980; Weber 1993), while the other studies either did not specify whether or not the patients had sciatica, or included a mixed population of patients with and without sciatica .

Thirty‐seven studies reported exclusively on acute low‐back pain (Aghababian 1986; Agrifoglio 1994; Amlie 1987; Bakshi 1994; Basmajian 1989; Blazek 1986; Borenstein 1990; Braun 1982; Brown 1986; Colberg 1996; Dreiser 2001; Dreiser 2003; Evans 1980; Goldie 1968; Hingorani 1970; Hingorani 1975; Hosie 1993; Innes 1998; Kuhlwein 1990; Lacey 1984; Metscher 2001; Milgrom 1993; Nadler 2002; Orava 1986; Pena 1990; Pohjolainen 2000; Schattenkirchner2003; Stratz 1990; Sweetman 1987; Szpalski 1990; Szpalski 1994; Videman 1984a; Waterworth 1985; Weber 1993; Wiesel 1980; Ximenes 2007; Yakhno 2006); nine studies reported exclusively on chronic low‐back pain (Berry 1982; Birbara 2003; Chrubasik 2003; Coats 2004; Driessens 1994; Hickey 1982; Katz 2003; Videman 1984b; Zerbini 2005), while the other studies reported either on a mixed population of (sub)acute and chronic low‐back pain, or did not adequately specify if patients with acute or chronic low‐back pain were included (e.g. by reporting the mean and standard deviation of the duration of back pain in the population). Studies from this last category were included in the analyses for acute or chronic low‐back pain if the authors stated somewhere in the article that it was about acute or chronic low‐back pain, even if they did not provide data on the duration (e.g. mean (SD) number of days of low‐back pain episode).

Eight studies evaluated the efficacy of selective COX‐2 inhibitors. Three versus placebo (Birbara 2003;Coats 2004; Katz 2003) and five versus traditional NSAIDs (Dreiser 2001b; Famaey 1998; Pohjolainen 2000; Ximenes 2007; Zerbini 2005).

Risk of bias in included studies

Twenty‐eight studies (43%) were considered high quality. (Babej‐Dolle 1994; Bakshi 1994; Berry 1982; Berry 1988b; Birbara 2003; Blazek 1986; Chrubasik 2003; Coats 2004; Dreiser 2001; Dreiser 2003; Goldie 1968; Hickey 1982; Innes 1998; Jaffe 1974; Katz 2003; Kuhlwein 1990; Matsumo 1991; Orava 1986; Pohjolainen 2000; Schattenkirchner2003; Szpalski 1994; Vetter 1988; Videman 1984a; Weber 1980; Weber 1993; Ximenes 2007; Yakhno 2006; Zerbini 2005). The most prevalent methodologic shortcomings, which were identified in more than half of the trials, were that the randomization procedure and concealment of treatment allocation were inadequate, that measures were not taken in the study design to avoid co‐interventions, that compliance was unsatisfactory and that the length of follow‐up was inadequate.

Effects of interventions

NSAIDs versus placebo

Acute low‐back pain

Eleven studies comparing NSAIDs with placebo for acute low‐back pain were included in our meta‐analysis. Seven of these studies were high quality (Babej‐Dolle 1994; Dreiser 2001; Dreiser 2003; Goldie 1968; Szpalski 1994; Weber 1980; Weber 1993) and four low quality (Amlie 1987; Basmajian 1989; Jacobs 1968; Lacey 1984). Three studies reported on low‐back pain without sciatica (Amlie 1987; Dreiser 2003; Szpalski 1994), four on sciatica (Dreiser 2001; Goldie 1968; Weber 1980; Weber 1993), and the other four on a mixed population.

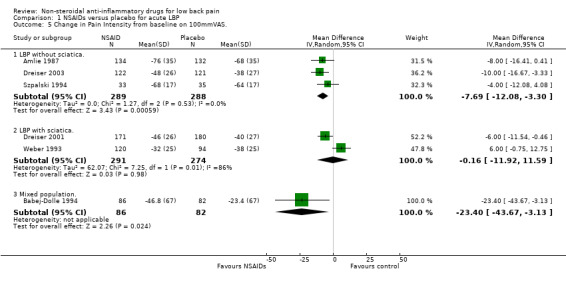

Six of these eleven studies reported sufficient data on pain intensity to enable statistical pooling (Amlie 1987; Babej‐Dolle 1994; Dreiser 2001; Dreiser 2003; Szpalski 1994; Weber 1993). The Chi‐square value for homogeneity of the weighted mean difference (WMD) was 16.18 (P < 0.01), indicating statistical heterogeneity among these studies.

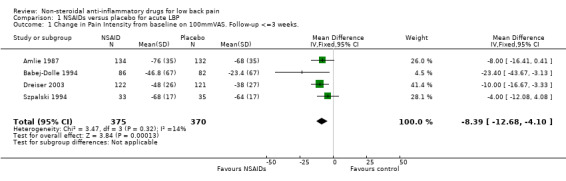

Potential explanations for this heterogeneity were explored. The meta‐analysis was split into studies reporting on low‐back pain without sciatica or a mixed population and studies reporting on low‐back pain with sciatica only. the studies that reported on non‐sciatic/mixed acute low‐back pain were statistically homogeneous (Chi‐square 3.47; P > 0.1), and using the fixed‐effect model, the pooled WMD was ‐8.39 (95% CI ‐12.68 to ‐4.10), indicating a statistically significant effect in favour of NSAIDs compared to placebo (graph 01.01). The sciatica‐only studies were still heterogeneous (Chi‐square 7.25; P < 0.01) and there was no statistical difference in effect between NSAIDs and placebo (WMD ‐0.16; 95% CI ‐11.92 to 11.52).

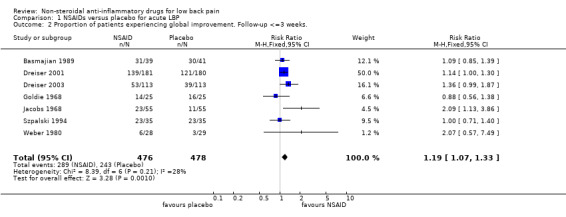

Seven of the eleven studies which compared NSAIDs with placebo for acute low‐back pain reported dichotomous data on global improvement (Basmajian 1989; Dreiser 2001; Dreiser 2003; Goldie 1968; Jacobs 1968; Szpalski 1994; Weber 1980). The Chi‐square value for homogeneity of the RR was 8.39 (P > 0.1), indicating statistical homogeneity among these studies. The pooled RR for global improvement after one week, using the fixed‐effect model, was 1.19 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.33), indicating a statistically significant effect in favour of NSAIDs compared to placebo (graph 01.02).

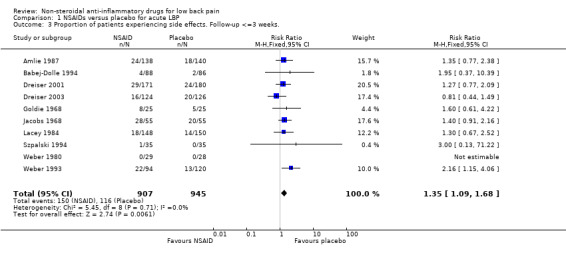

Ten of the eleven studies which compared NSAIDs with placebo for acute low‐back pain reported data on side effects. The Chi‐square value for homogeneity of the RR for side effects was 5.45 (P > 0.5), indicating homogeneity among the studies. Using the fixed‐effect model, the pooled RR for side effects was 1.35 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.68), indicating statistically significantly fewer side effects in the placebo group (graph 01.03).

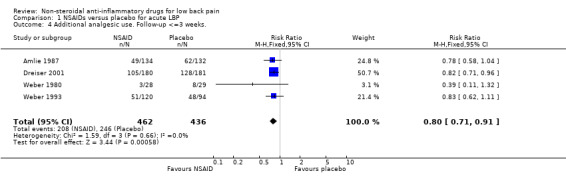

Four of the eleven studies which compared NSAIDs with placebo for acute low‐back pain reported data on the need for additional analgesic use (Amlie 1987; Dreiser 2001; Weber 1980; Weber 1993). The Chi‐square value for homogeneity of the RR was 1.59 (df = 3; P > 0.5), indicating statistical homogeneity. Using the fixed‐effect model, the pooled RR for analgesic use was 0.80 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.91), indicating significantly less use of analgesics in the NSAIDs group (graph 01.04). Analgesics were not permitted in three trials (Goldie 1968; Jacobs 1968; Szpalski 1994).

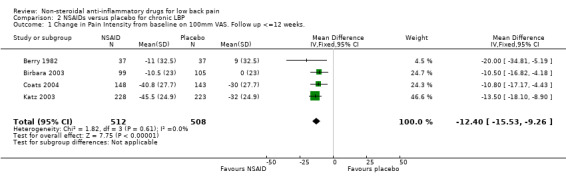

Chronic low‐back pain

All four studies which compared NSAIDs with placebo for chronic low‐back pain reported sufficient data on pain intensity to enable statistical pooling. The Chi‐square value for homogeneity of the weighted mean difference (WMD) was 1.82 (P > 0.5), indicating statistical homogeneity among these studies. Using the fixed‐effect model, the pooled WMD was ‐12.40 (95% CI ‐15.53 to ‐9.26), indicating a statistically significant effect in favour of NSAIDs compared to placebo (graph 02.01).

The four studies also reported data on side effects. The Chi‐square value for homogeneity of the RR for side effects was 1.01 (df = 3; P > 0.5), indicating homogeneity among the studies. Using the fixed‐effect model, the pooled RR for side effects was 1.24 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.43), indicating statistically significantly fewer side effects in the placebo group (graph 02.02).

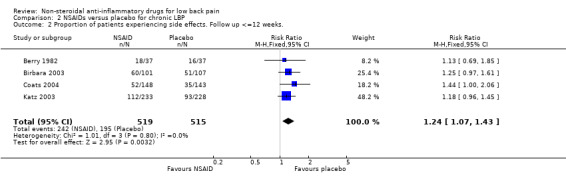

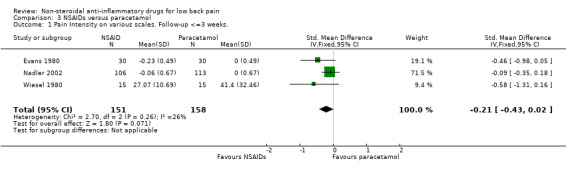

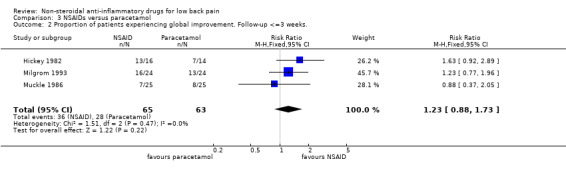

NSAIDs versus paracetamol/acetaminophen

Six studies, one high quality study (Hickey 1982) and five low quality studies (Evans 1980; Milgrom 1993; Muckle 1986; Nadler 2002; Wiesel 1980), compared some type of NSAID with paracetamol or acetaminophen. There is moderate evidence that NSAIDs are equally effective for pain relief and global improvement compared with paracetamol for acute low‐back pain (Evans 1980; Milgrom 1993; Nadler 2002; Wiesel 1980); pooled SMD ‐0.21 (95% CI ‐0.43 to 0.02; N = 309); pooled RR 1.23 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.73; N = 128) (Hickey 1982, Milgrom 1993, Muckle 1986) (graphs 03.01 and 03.02). One low quality study in a mixed population of acute and chronic low‐back pain patients also found no differences (Muckle 1986). One high quality study (Hickey 1982) found limited evidence that NSAIDs are more effective for pain relief than paracetamol in patients with chronic low‐back pain.

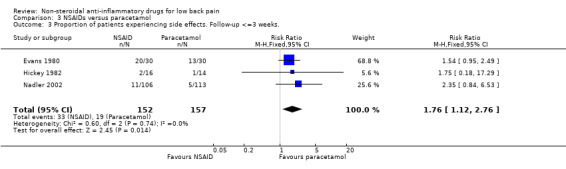

NSAIDs were associated with more side effects compared to paracetamol (RR 1.76; 95% CI 1.12 to 2.76, N = 309) (graph 03.03).

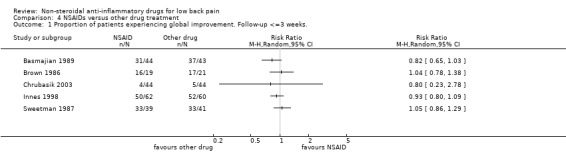

NSAIDs versus other drugs

Nine studies (Basmajian 1989; Braun 1982; Brown 1986; Chrubasik 2003; Evans 1980; Ingpen 1969; Metscher 2001; Sweetman 1987; Videman 1984a) were identified that compared NSAIDs with some other kind of drug. Two of these studies were considered to be of high methodologic quality (Chrubasik 2003; Videman 1984a). Seven studies reported on acute low‐back pain, five of which, including one high quality study, did not find any statistical differences between NSAIDs and narcotic analgesics or muscle relaxants (Basmajian 1989; Braun 1982; Brown 1986; Sweetman 1987; Videman 1984a). Because of clinical heterogeneity, the pooled RR was not estimated (graph 04.01). There is moderate evidence that NSAIDs are not more effective than other drugs for acute low‐back pain.

For chronic low‐back pain, one high quality study (Chrubasik 2003) reported equal effectiveness for an NSAID (doloteffin) compared to a herbal medicine (Harpagophytum procumbens).

One study did not specify if patients with acute and/or chronic low‐back pain were included and data extraction was not possible from this study (Ingpen 1969).

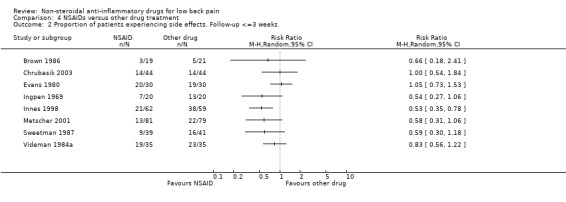

Side effects are plotted in Graph 04.02.

NSAIDs versus non‐drug treatments

Four low quality studies were identified comparing NSAIDs with non‐drug treatments such as spinal manipulation, physiotherapy and bed rest. There is conflicting evidence that NSAIDs are more effective than bed rest for acute low‐back pain, as one study (Szpalski 1990) reported a positive outcome and one study did not find a significant difference (Postacchini 1988). However, the latter study also showed a larger improvement in the NSAID group, and the small number in the bed rest group (N = 29) may have caused a lack of power to detect a statistically significant difference. Two studies found no differences between NSAIDs and physiotherapy or spinal manipulation in acute low‐back pain (Postacchini 1988; Waterworth 1985), therefore, there is moderate evidence that NSAIDs are not more effective than physiotherapy or spinal manipulation for acute low‐back pain. One study may have lacked power because of the small groups (Waterworth 1985). One low quality study comparing NSAIDs to a heat‐wrap for patients with acute low‐back pain, found a statistically significant difference in favour of the heat‐wrap. So, there is limited evidence that NSAIDs are less effective than a heat‐wrap for acute low‐back pain.

Comparison of different types of NSAIDs

Thirty‐three trials compared at least two or more different types of NSAIDs. Two trials compared two types of NSAIDs (diclofenac versus dipyrone and diclofenac versus etofenamat, respectively) administered by intramuscular injection (Babej‐Dolle 1994; Stratz 1990). One compared intramuscular diclofenac with intravenous meloxicam (Colberg 1996), one compared an intramuscular injection of tenoxicam with tenoxicam tablets (Listrat 1990), one compared ibuprofen tablets with felbinac foam (Hosie 1993), and one compared diclofenac gel with indomethacin plaster (Waikakul 1996).

One study reported on acute and chronic low‐back pain separately, and consequently a total of 20 studies included acute low‐back pain patients, four chronic low‐back pain patients, and eight an unspecified or mixed population of acute and chronic low‐back pain patients.

Six studies on acute low‐back pain reported differences between the NSAIDs and fifteen found no differences. Eleven studies on acute low‐back pain were of high quality (Babej‐Dolle 1994; Bakshi 1994; Blazek 1986; Dreiser 2001; Dreiser 2003; Jaffe 1974; Orava 1986; Pohjolainen 2000; Schattenkirchner2003; Ximenes 2007; Yakhno 2006). One of the high quality studies compared two types of NSAIDs administered by intramuscular injection and reported better results for dipyrone compared to diclofenac (Babej‐Dolle 1994). None of the other high quality studies evaluating NSAIDs capsules found any differences.

There seems to be no difference in the reported number and severity of side effects for the various types of NSAIDs. Only three low quality studies reported statistically significant differences in side effects (Agrifoglio 1994; Famaey 1998; Hingorani 1975).

Although 33 studies compared different types of NSAIDs, it was only possible to state that there is moderate evidence based on two trials that the relative effectiveness of meloxicam is equal to diclofenac for acute low‐back pain (Colberg 1996; Dreiser 2001b). None of the other studies compared the same two NSAIDs for acute or chronic low‐back pain.

COX‐2 NSAIDs versus traditional NSAIDs

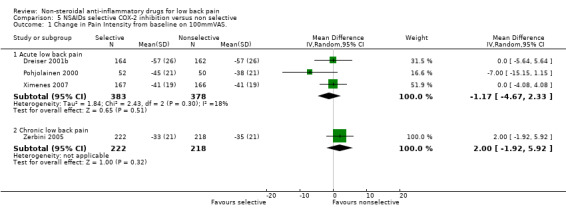

Five studies compared COX‐2 NSAIDs with traditional NSAIDs (meloxicam versus diclofenac (Dreiser 2001b); nimesulide versus diclofenac (Famaey 1998); nimesulide versus ibuprofen (Pohjolainen 2000); valdecoxib versus diclofenac (Ximenes 2007); etoricoxib versus diclofenac (Zerbini 2005)). Statistical pooling of three studies (Dreiser 2001b; Pohjolainen 2000; Ximenes 2007) found no statistically significant differences for pain relief for acute low‐back pain (graph 05.01). The fourth study showed similar results.

The fifth, a high quality study, found moderate evidence that there were no differences in pain relief between COX‐2 and traditional NSAIDs for chronic low‐back pain (Zerbini 2005).

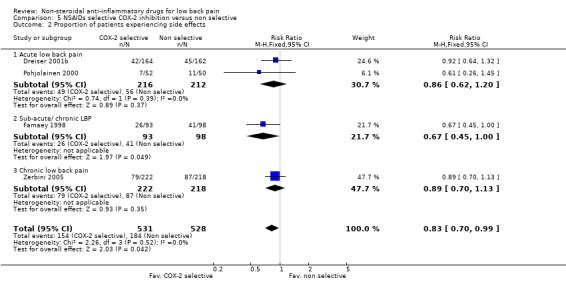

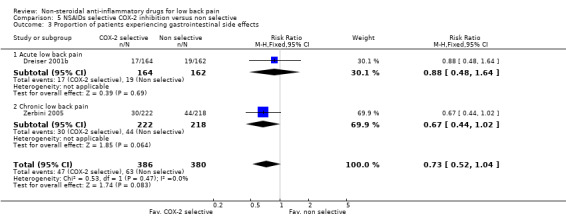

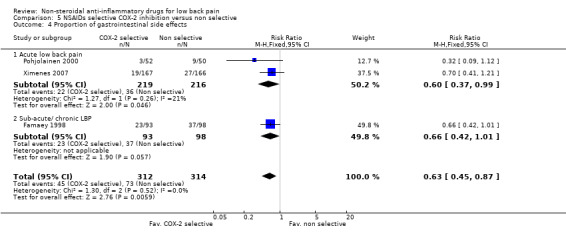

COX‐2 NSAIDs had statistically significantly fewer side‐effects (RR 0.83 ; 95% CI 0.70 to 0.99) (graphs 05.02, 05.03, 05.04).

NSAIDs versus NSAIDs plus muscle relaxants

Three studies, one high quality and two low quality RCTs, compared some type of NSAID with NSAIDs plus muscle relaxants for acute low‐back pain. In all three studies, the authors reported the combination of an NSAID with a muscle relaxant to be better than the NSAID alone, although there were no statistically significant differences. In two trials, side effects were more frequent in the combination groups (Berry 1988b; Borenstein 1990). The review authors concluded that no differences were shown in any of the three trials and therefore, there is moderate evidence that muscle relaxants do not provide any additional effect to NSAIDs alone for acute low‐back pain.

NSAIDs versus NSAIDs plus B vitamins

Three studies compared diclofenac with the addition of B vitamins for low‐back pain, two of which were high quality (Kuhlwein 1990; Vetter 1988). All three studies were published in German. Two studies included patients with acute low‐back pain (Bruggemann 1990; Kuhlwein 1990); one included patients with degenerative changes (Vetter 1988). The authors of all three studies reported positive results for the combination therapy, although there were no statistically significant differences reported in two of these (Bruggemann 1990; Vetter 1988). The review authors concluded that there is conflicting evidence that an NSAID (diclofenac) plus B vitamins are more effective than diclofenac alone for acute low‐back pain, and limited evidence that B vitamins do not provide additional effect to an NSAID for chronic degenerative low‐back pain.

Discussion

Efficacy

The results of the 65 RCTs which were included in this review suggest that NSAIDs are slightly effective for short‐term global improvement in patients with acute and chronic low‐back pain without sciatica.

The placebo‐controlled studies suggest that NSAIDs are effective in improving global improvement in patients with acute low‐back pain, but effects are only small. Quantitative analysis, in which the results of individual RCTs were statistically pooled, indicate statistically significant effects in favour of NSAIDs compared to placebo for populations with acute and chronic low‐back pain without sciatica. Besides the effectiveness of NSAIDs compared to placebo, the NSAIDs group with acute low‐back pain used less additional analgesics, but there was a statistically significantly higher number of patients with side‐effects in the NSAIDs group.

The studies regarding chronic low‐back pain also showed statistically significantly more side‐effects in the NSAIDs group compared with placebo. In addition, in all newly added studies assessing NSAIDs for chronic low‐back pain, a so called "flare design" was used, in which patients who were already responding well to NSAIDs are only included when they show a large worsening in low‐back pain complaints during a wash‐out period. This may have caused favourable results of the investigated NSAIDs, expressed in an overestimation of the effects and an underestimation of the side‐effects due to the selection of the study population, and certainly decreases the external validity for daily practice.

Whether NSAIDs are more effective than other drugs or non‐drug therapies for acute low‐back pain still remains unclear. There is conflicting evidence that NSAIDs are more effective than simple analgesics or bed rest, and moderate evidence that NSAIDs are not more effective than other drugs, physiotherapy or spinal manipulation for acute low‐back pain. NSAIDs in combination with muscle relaxants or B vitamins do not seem to provide more benefits than NSAIDs alone. However, except for the B vitamin studies, the group sizes in these studies were smaller than 65 and therefore, these studies simply may have lacked power to detect a statistically significant difference. Sample size calculations have shown that 65 patients are needed per group to detect a clinically relevant difference of 25% with a power of 0.80 and an alpha of 0.05. There is little evidence on the most effective way of administration, i.e. intramuscular injections, capsules or a combination of both, or gel, as only a few studies evaluated injections or gel.

There is strong evidence that various types of NSAIDs are equally effective for acute low‐back pain.

The efficacy of NSAIDS for patients with sciatica has not been shown in the studies included in this review. Even compared to placebo, the favourable effects of NSAIDs could not be demonstrated in this important subgroup of patients.

Side effects

There is no clear difference in the reported number or severity of side‐effects between the different types of NSAIDs in the studies included in this review. Numerous articles have reported on the side‐effects of NSAIDs, especially gastrointestinal events. In the studies presented in this review, side‐effects were also frequently reported, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, edema, dry mouth, rash, dizziness, headache, tiredness, etc. According to the authors of the studies, most side‐effects were considered to be mild to moderately severe. However, the sample sizes of most of the studies were relatively small and therefore, no clear conclusion can be drawn from these studies regarding the risks for gastrointestinal and other side effects of NSAIDs. Statistical pooling of all side effects of NSAIDs compared to placebo for acute low‐back pain indeed showed an increased RR, indicating the additional risk of using NSAIDs. The comparison of several COX‐2 selective NSAIDs with traditional NSAIDs showed a decreased RR of side‐effects associated with COX‐2 NSAIDs but more extended analyses of the separate risks of upper and lower gastrointestinal side‐effects and central nervous system side effects are needed. In this respect, the recent insights and debate on the increased risk for cardiovascular events associated with the use of selective COX‐2 inhibitors are of importance. These increased risks of COX‐2 NSAIDs (as compared with placebo) have been shown in large randomized clinical trials. These finding have lead to the removal of some selective COX‐2 inhibitors from the market. The current question is whether the increased risk holds for all selective COX‐2 inhibitors and perhaps for the traditional NSAIDs as well. But in order to validly answer this question, more valid data are needed from large epidemiologic studies of NSAID side effects. These data should also consider the dose, frequency and duration of the NSAID intake. It might well be, that in the majority of patients with low‐back pain, the intake is of short duration and might not reach the level associated with increased cardiovascular risks.

Henry (Henry 1996) reported the results of a meta‐analysis of controlled epidemiological studies on the relative risks of serious gastrointestinal complications due to NSAIDs. The authors concluded that ibuprofen was associated with the lowest relative risk of serious gastrointestinal complications. However, this was mainly attributable to the low doses of ibuprofen used in clinical practice. Because there are no important differences in efficacy between the different types of NSAIDs, Henry 1996 recommended using the lowest effective doses of drugs that seem to be associated with a comparatively low risk of serious gastrointestinal complications.

Methodological quality

This review shows that many RCTs examining the efficacy of NSAIDs in low‐back pain have methodological shortcomings. The randomization procedure was not described in most studies, making it impossible for the reader of the article to determine whether adequate procedures were used to exclude bias. In many studies, no measures were taken in the study design to avoid co‐interventions, so it remains unclear if a reported difference of effect was due to the NSAID alone, or to a co‐intervention (vice versa, if there was no difference in effect, this may be due to co‐interventions in the control group). Compliance was often not measured and reported or was not satisfactory, leaving it uncertain if the prescribed medication was actually taken and leaving it unclear if the effect (or lack of effect) was due to the prescribed regimen. The length of follow‐up was considered inadequate in more than half of the trials, because there was no long‐term follow‐up. Since international guidelines set prevention of disability as one of the main goals of early management and NSAIDs play a role in establishing this goal, one would be interested to know if NSAIDs also have any long‐term benefits. In post hoc sensitivity analyses, we repeated the meta‐analyses without the low quality studies, but these did not alter the direction of any of the conclusions.

Although not related to the internal validity or methodological quality of the RCTs, the small size of the study populations in many RCTs indicates that these studies may lack statistical power to detect clinically relevant differences in effects. Statistical pooling may be a way to overcome this problem, but as was shown in this review, pooling is not always feasible. Smaller sample sizes may also lead to an imbalance of important prognostic factors between the study groups after randomisation, which may lead to biased outcomes if, by chance, patients in one group had a more favourable prognosis.

The reported methodologic flaws are not unique for RCTs evaluating the efficacy of NSAIDs, but have been reported to be a general problem in low‐back pain trials (Koes 1995). On average, trials of drug therapy for low‐back pain even have a higher methodologic quality than non‐drug trials (van Tulder 1997). However, there is still a need to improve the development, conduct and reporting of RCTs in the field of back pain.

Limitations of the study

It is possible that the effectiveness of NSAIDs is overestimated in this review because of publication bias. The language criteria we used for including studies in this review might even have enlarged this risk, as positive results are more likely to be published in English. However we were not able to estimate the impact it might have had on our results, as the number of studies per comparison was small.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The evidence from the 65 RCTs included in this review suggests that NSAIDs are effective for short‐term global improvement in patients with acute and chronic low‐back pain without sciatica, although the effects are small. It is still unclear if NSAIDs are more effective than simple analgesics and other drugs. Furthermore, there does not seem to be a specific type of NSAID which is clearly more effective than others, nor is there any evidence to recommend another route of administration besides oral capsules or tablets. NSAIDs plus muscle relaxants or B vitamins do not seem to be more effective than NSAIDs alone. For patients with sciatica, there is no evidence that NSAIDs are more effective than placebo.

Implications for research.

There is a need for RCTs, which meet the current high methodological standards, to evaluate the effectiveness of NSAIDs for treating patients with acute low‐back pain with sciatica and for treating patients with chronic low‐back pain with sciatica. It also seems useful to evaluate the most effective dose with the comparatively lowest risk of (serious) side effects.

Feedback

Inaccuracies in NSAIDs for low back pain review

Summary

please note that these comments refer to the 2002(2) version of the review. A substantial update is being published in The Cochrane Library 2008, issue 1 which should address the concerned outlined below (VEP, Managing Editor)

In the course of reviewing this review the commentator noted a number of problems. His intention was to feed them back to help improve the review.

According to the commentator, the problems were the following: 1. He stated that verifying the conclusions by looking directly at the results of the included studies was difficult. The actual results are helpfully given in the characteristics of included studies table. It would be helpful if this table could be sub‐divided according to the conditions (acute or chronic LBP) and comparator (placebo, other NSAID, other treatments) i.e. grouped according to the sub‐categories by which the review author report the results. 2. He indicated there are some discrepancies between the numerical results in the table of included characteristics and the Forest plots. 3. He also reports there are some instances where the results for the control have been entered for the experimental group and vice versa. 4. The "favours" labels at the bottom of the Forest plot for the outcome of numbers needing additional analgesia are the wrong way round. An OR > 1 favours the control for this outcome, not NSAID. 5. He feels that care needs to be taken in using the summary OR from the meta‐analysis to indicate the overall impact on pain and analgesic use in placebo controlled trials for acute LBP when only 3 of the 9 included studies contribute, without indicating that the other six did not measure these outcomes (which he doubts).

He states, "Basically I'm afraid that there needs to be a careful re‐run of the data abstraction and analysis. "

Reply

Review author has not responded to date

Contributors

2(2)Commentator ‐ Chris Hyde, Dept of Public Health & Epidemiology, University of Birmingham Criticism Editor ‐ Dr. Alf Nachemson

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 19 January 2011 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1997 Review first published: Issue 1, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 February 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 9 September 2008 | Amended | ROB Tables edited |

| 11 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 17 October 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

| 30 June 2007 | New search has been performed | The literature search was updated from September 1998 to June 2007. Fifteen studies (number of patients = 5180) were added to the previous review. Of these, 12 studies (80%) were considered high quality. This brings the total to 65 included studies (total number of patients = 11,237). In addition, clinical relevance was assessed for all 65 included studies, but these results are not interpreted. In this update we could perform a meta‐analysis on placebo controlled chronic low back pain studies, and we compaired selective Cox‐2 inhibitors with traditional NSAIDs. |

| 15 May 2001 | Feedback has been incorporated | See feedback section |

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Rachel Couban, Trial Search Co‐ordinator, Cochrane Back Review Group for updating the literature search.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

(randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized controlled trials [mh] OR random allocation [mh] OR double‐blind method [mh] OR single‐blind method [mh] OR clinical trial [pt] OR clinical trials [mh] OR "clinical trial" [tw] OR ((singl* [tw] OR doubl* [tw] OR trebl* [tw] OR tripl* [tw]) AND (mask* [tw] OR blind* [tw])) OR "latin square" [tw] OR placebos [mh] OR placebo* [tw] OR random* [tw] OR research design [mh:noexp] OR comparative study [mh] OR evaluation studies [mh] OR follow‐up studies [mh] OR prospective studies [mh] OR cross‐over studies [mh] OR control* [tw] OR prospectiv* [tw] OR volunteer* [tw]) NOT (animal [mh] NOT human [mh]) Limits: Entrez Date from 1998/10/01

("low back pain"[MeSH Terms] OR low back pain[Text Word]) OR ("sciatica"[MeSH Terms] OR sciatica[Text Word]) Limits: Entrez Date from 1998/10/01

("non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agents"[Text Word] OR "anti‐inflammatory agents, non‐steroidal"[MeSH Terms] OR "anti‐inflammatory agents, non‐steroidal"[Pharmacological Action] OR Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal[Text Word]) Limits: Entrez Date from 1998/10/01

acetylsalicyl* OR carbasalaatcalcium OR diflunisal OR aceclofenac OR alclofenac OR diclofenac OR indometacin OR sulindac OR meloxicam OR piroxicam OR dexibuprofen OR dexketoprofen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR ibuprofen OR ketoprofen OR naproxen OR tiapro* OR metamizol OR phenylbutazone OR phenazone OR propyphenazone OR celecoxib OR etoricoxib OR nabumeton OR parecoxib Limits: Entrez Date from 1998/10/01

#3 OR #4 Limits: Entrez Date from 1998/10/1

#1 AND #2 AND #5 Limits: Entrez Date from 1998/10/1

Appendix 2. CENTRAL search strategy

(low back pain), from 1998 to 2007 in Clinical Trials

MeSH descriptor Low Back Pain explode all trees

(#1 OR #2), from 1998 to 2007 in Clinical Trials

nsaid*, from 1998 to 2007 in Clinical Trials

MeSH descriptor Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal explode all trees

(#4 OR #5), from 1998 to 2007 in Clinical Trials

(#3 AND #6), from 1998 to 2007 in Clinical Trials

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy

'low back pain'/exp OR low‐back‐pain OR 'ischialgia'/exp OR ischialgia OR sciatica OR lumbago OR ('sacroiliac joint'/exp AND (pain/de OR backache/de)) AND ('nonsteroid antiinflammatory agent'/exp OR acetylsalicyl* OR carbasalaatcalcium OR diflunisal OR aceclofenac OR alclofenac OR diclofenac OR indometacin OR sulindac OR meloxicam OR piroxicam OR dexibuprofen OR dexketoprofen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR ibuprofen OR ketoprofen OR naproxen OR tiapro* OR metamizol OR phenylbutazone OR phenazone OR propyphenazone OR celecoxib OR etoricoxib OR nabumeton OR parecoxib) AND 'clinical trial'/exp OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'prospective study'/de OR 'clinical article'/de OR 'controlled study'/exp OR 'major clinical study'/de OR 'double blind procedure'/de OR 'single blind procedure'/de OR 'crossover procedure'/de OR placebo/exp OR 'comparative study'/de OR randomization/exp OR ((singl* OR doubl* OR trebl*) AND (mask* OR blind*)) OR latin‐square OR placebo* OR random* OR control* OR prospectiv* OR volunteer* OR 'evaluation and follow up'/de AND [01‐10‐1998]/sd NOT ([animals]/lim NOT [humans]/lim)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. NSAIDs versus placebo for acute LBP.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Change in Pain Intensity from baseline on 100mmVAS. Follow‐up <=3 weeks. | 4 | 745 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐8.39 [‐12.68, ‐4.10] |

| 2 Proportion of patients experiencing global improvement. Follow‐up <=3 weeks. | 7 | 954 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [1.07, 1.33] |

| 3 Proportion of patients experiencing side effects. Follow‐up <=3 weeks. | 10 | 1852 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.35 [1.09, 1.68] |

| 4 Additional analgesic use. Follow‐up <=3 weeks. | 4 | 898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.71, 0.91] |

| 5 Change in Pain Intensity from baseline on 100mmVAS. | 6 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 LBP without sciatica. | 3 | 577 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐7.69 [‐12.08, ‐3.30] |

| 5.2 LBP with sciatica. | 2 | 565 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.16 [‐11.92, 11.59] |

| 5.3 Mixed population. | 1 | 168 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐23.4 [‐43.67, ‐3.13] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus placebo for acute LBP, Outcome 1 Change in Pain Intensity from baseline on 100mmVAS. Follow‐up <=3 weeks..

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus placebo for acute LBP, Outcome 2 Proportion of patients experiencing global improvement. Follow‐up <=3 weeks..

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus placebo for acute LBP, Outcome 3 Proportion of patients experiencing side effects. Follow‐up <=3 weeks..

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus placebo for acute LBP, Outcome 4 Additional analgesic use. Follow‐up <=3 weeks..

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs versus placebo for acute LBP, Outcome 5 Change in Pain Intensity from baseline on 100mmVAS..

Comparison 2. NSAIDs versus placebo for chronic LBP.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Change in Pain Intensity from baseline on 100mm VAS. Follow up <=12 weeks. | 4 | 1020 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐12.40 [‐15.53, ‐9.26] |

| 2 Proportion of patients experiencing side effects. Follow up <=12 weeks. | 4 | 1034 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [1.07, 1.43] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 NSAIDs versus placebo for chronic LBP, Outcome 1 Change in Pain Intensity from baseline on 100mm VAS. Follow up <=12 weeks..

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 NSAIDs versus placebo for chronic LBP, Outcome 2 Proportion of patients experiencing side effects. Follow up <=12 weeks..

Comparison 3. NSAIDs versus paracetamol.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain Intensity on various scales. Follow‐up <=3 weeks. | 3 | 309 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.21 [‐0.43, 0.02] |

| 2 Proportion of patients experiencing global improvement. Follow‐up <=3 weeks. | 3 | 128 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.88, 1.73] |

| 3 Proportion of patients experiencing side effects. Follow‐up <=3 weeks. | 3 | 309 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.76 [1.12, 2.76] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs versus paracetamol, Outcome 1 Pain Intensity on various scales. Follow‐up <=3 weeks..

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs versus paracetamol, Outcome 2 Proportion of patients experiencing global improvement. Follow‐up <=3 weeks..

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs versus paracetamol, Outcome 3 Proportion of patients experiencing side effects. Follow‐up <=3 weeks..

Comparison 4. NSAIDs versus other drug treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion of patients experiencing global improvement. Follow‐up <=3 weeks. | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Proportion of patients experiencing side effects. Follow‐up <=3 weeks. | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 NSAIDs versus other drug treatment, Outcome 1 Proportion of patients experiencing global improvement. Follow‐up <=3 weeks..

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 NSAIDs versus other drug treatment, Outcome 2 Proportion of patients experiencing side effects. Follow‐up <=3 weeks..

Comparison 5. NSAIDs selective COX‐2 inhibition versus non selective.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Change in Pain Intensity from baseline on 100mmVAS. | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Acute low back pain | 3 | 761 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.17 [‐4.67, 2.33] |

| 1.2 Chronic low back pain | 1 | 440 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.0 [‐1.92, 5.92] |

| 2 Proportion of patients experiencing side effects | 4 | 1059 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.70, 0.99] |

| 2.1 Acute low back pain | 2 | 428 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.62, 1.20] |

| 2.2 Sub‐acute/ chronic LBP | 1 | 191 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.45, 1.00] |

| 2.3 Chronic low back pain | 1 | 440 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.70, 1.13] |

| 3 Proportion of patients experiencing gastrointestinal side effects | 2 | 766 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.52, 1.04] |

| 3.1 Acute low back pain | 1 | 326 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.48, 1.64] |

| 3.2 Chronic low back pain | 1 | 440 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.44, 1.02] |

| 4 Proportion of gastrointestinal side effects | 3 | 626 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.45, 0.87] |

| 4.1 Acute low back pain | 2 | 435 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.37, 0.99] |

| 4.2 Sub‐acute/ chronic LBP | 1 | 191 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.42, 1.01] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 NSAIDs selective COX‐2 inhibition versus non selective, Outcome 1 Change in Pain Intensity from baseline on 100mmVAS..

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 NSAIDs selective COX‐2 inhibition versus non selective, Outcome 2 Proportion of patients experiencing side effects.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 NSAIDs selective COX‐2 inhibition versus non selective, Outcome 3 Proportion of patients experiencing gastrointestinal side effects.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 NSAIDs selective COX‐2 inhibition versus non selective, Outcome 4 Proportion of gastrointestinal side effects.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Aghababian 1986.

| Methods | RCT, open‐label. Randomization procedure not described. | |

| Participants | 56 Patients. Inclusion criteria: mild to moderate acute LBP, 18 to 60 years of age. Exclusion criteria: taking analgesics, chronic back pain, pain longer than 72 hours, history of bleeding disorders, high blood pressure, heart, kidney, liver or ulcer disease, pregnant or breast feeding, allergic reactions to analgesics or NSAIDs. | |

| Interventions | NSAID (i): diflunisal capsules, 1000 mg initially, 500 mg every 8 to 12 hrs, 2 wks (N=16). NSAID (ii): naproxen capsules, 500 mg initially, 250 mg every 6 to 8 hrs, 2 wks (N=17). | |

| Outcomes | No. of patients (%) reporting no pain (on a ordinal 4‐point scale) after 2 weeks (i) 81% (ii) 41%. No significance tests reported. No adverse experiences were reported by the patients. | |

| Notes | Methodological quality: randomization ‐; treatment allocation ‐; withdrawals ‐; co‐interventions ‐; patients blinded ‐; outcomes blinded ‐; care providers blinded ‐; intention‐to‐treat ‐; compliance ‐; baseline similarity +; follow‐up ‐. Total score = 1. Clinical relevance: patients description + intervention description + outcome measures + effect size + benefits/ harms + | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Randomization procedure not described. |

Agrifoglio 1994.

| Methods | RCT; single‐blind. Randomization procedure not described. | |

| Participants | 100 Patients from 5 centers, 60 men and 40 women, aged 19 to 68 years. Inclusion criteria: acute lumbago, less than 48 hours, age 18 to 70 years, pain intensity at least 50 mm on VAS. Exclusion criteria: any disorder which might interfere with the study drug, anticoagulants or other drugs which may interfere with the assessment of treatment, pregnancy, breastfeeding or hormonal contraception. | |

| Interventions | NSAID (i): Aceclofenac 150 mg intramuscular b.i.d. for 2 days + 100 mg tablets b.i.d. for 5 days + 1 placebo tablet for 5 days (N=50). NSAID (ii): Diclofenac 75 mg intramuscular b.i.d. for 2 days + 50 mg tablets t.i.d. for 5 days (N=50). | |

| Outcomes | Mean improvement in pain intensity (VAS) after 8 days: (i) 65 (ii) 62. Global improvement good/very good in (i) 87% and (ii) 79% of patients. Side effects: (i) 1 (ii) 8 patients. | |

| Notes | Methodological quality: randomization ‐; treatment allocation ‐; withdrawals +; co‐interventions ‐; patients blinded ‐; outcomes blinded ‐; care providers blinded ‐; intention‐to‐treat ‐; compliance ‐; baseline similarity +; follow‐up ‐. Total score = 2. Clinical relevance: patients description + intervention description + outcome measures + effect size ‐ benefits/ harms ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Randomization procedure not described. |

Amlie 1987.

| Methods | RCT, double‐blind, placebo controlled. Randomization procedure not described. | |

| Participants | 282 Patients. Inclusion criteria: acute LBP lees than 48 hours, free from LBP for 3 months, age 18 to 60 years. Exclusion criteria: radicular symptoms, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, history of peptic ulcer or severe dyspepsia, hypersensitivity to aspirin or other NSAIDs, pregnancy or lactation, any other hematologic, hepatic, renal, pulmonary, cardiac or systemic disease. | |

| Interventions | NSAID (i): piroxicam 20 mg capsules, twice per day first two days, one per day next 5 days, 7 days (N=140). Reference treatment (ii): placebo capsules (N=142). | |

| Outcomes | (i) More pain relief than (ii) measured with visual analogue scale after 3 days. After 7 days no significant differences. Side effects similar (i) 18 (13%) (ii) 24 (17%). | |

| Notes | Methodological quality: randomization ‐; treatment allocation ‐; withdrawals +; co‐interventions ‐; patients blinded +; outcomes blinded +; care providers blinded +; intention‐to‐treat ‐; compliance ‐; baseline similarity +; follow‐up ‐. Total score = 5. Clinical relevance: patients description + intervention description + outcome measures + effect size ‐ benefits/ harms ‐ |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Randomization procedure not described |

Aoki 1983.

| Methods | RCT; double‐blind. Randomization procedure not described. | |

| Participants | 237 Patients. Inclusion criteria: adults presenting at clinical centers with principal complaint LBP. Exclusion criteria: history of gastrointestinal, hepatic or renal disease, those with complications or requiring surgery, history of drug allergy, anticoagulants, abnormal baseline laboratory values, pregnancy, nursing mothers and women with childbearing potential. | |

| Interventions | NSAID (i): piroxicam 20 mg capsules, once per day, 14 days (N=116). NSAID (ii): indomethacin 25 mg capsules, three times per day, 14 days (N=114). | |

| Outcomes | No. of patients (%) who are (very much) improved after 1 and 2 weeks assessed by a physician (i) 49%, 70% (ii) 46%, 58%. Patients assessment after 2 weeks (very) good (i) 69% (ii) 62%. No significant differences. Side effects similar (i) 11% (ii) 13%. | |

| Notes | ‐Methodological quality: randomization ‐; treatment allocation ‐; withdrawals +; co‐interventions ‐; patients blinded +; outcomes blinded +; care providers blinded +; intention‐to‐treat +; compliance ‐; baseline similarity ‐; follow‐up ‐. Total score = 5. Clinical relevance: patients description + intervention description + outcome measures + effect size ‐ benefits/ harms ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Randomization procedure not described |

Babej‐Dolle 1994.

| Methods | RCT; observer‐blind, multicenter study. Randomization using a random number generator. Drugs were randomized and provided by pharmaceutical company in individualized patient's kits, which were assigned by the investigator according to the patients order of entry to the study. | |

| Participants | 260 patients aged over 18 years with lumbago or sciatic pain, 134 men, 126 women. Exclusion criteria: hypersensitivity to drugs or drug related malfunction of liver or kidney, polyneuropathy, previous disk surgery or vertebral fractures, psychiatric disease, alcohol and drug abuse, pregnancy or lactation. | |

| Interventions | NSAIDs (i): dipyrone intramuscular, 5 ml (= 2.5 G) 1 to 2 injections, 1 to 2 days (N=88). NSAIDs (ii): diclofenac intramuscular, 3 ml (= 75 mg), 1to 2 injections, 1‐2 days (N=86). Reference treatment (iii): placebo, 5 ml isotonic saline, 1to 2 injections, 1‐2 days (N=86). | |

| Outcomes | Mean (SD) pain intensity (VAS) at baseline and after 6 hours: (i) 80.2 (15.4), 33.4 (25.5); (ii) 79.2 (14.5), 41.7 (25.9); (iii) 78.2 (14.8), 54.8 (25.3). (i) significantly better than (ii) and (iii). No. (%) of patients recovered after 2 days (5‐point NRS): (i) 27 (32%); (ii) 10 (12%); (iii) 7 (9%). Mean (SD) finger‐toe distance at baseline and after 2 days: (i) 29.0 (15.3), 12.0 (13.3); (ii) 28.9 (15.2), 16.3 (14.3); (iii) 29.7 (15.7), 21.1 (14.7). Side effects: (i) 4 patients, (ii) 1 patient, (iii) 2 patients. | |

| Notes | Methodological quality: randomization +; treatment allocation +; withdrawals +; co‐interventions +; patients blinded +; outcomes blinded +; care providers blinded +; intention‐to‐treat +; compliance +; baseline similarity ‐; follow‐up ‐. Total score = 9. Clinical relevance: patients description ‐ intervention description + outcome measures + effect size + benefits/ harms + | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Adequate ‐ Randomization using a random number generator. Drugs were randomized and provided by pharmaceutical company in individualized patient's kits, which were assigned by the investigator according to the patients order of entry to the study. |

Bakshi 1994.

| Methods | RCT; double‐blind, multicenter study. Randomization procedure not described. | |

| Participants | 132 patients, 62 men, 70 women. Inclusion criteria: acute back pain less than 1 week, moderate to severe pain (> 50 mm on VAS), at least 2 objective signs of lumbosacral pathology (tenderness, limited ROM or SLR < 75 degrees), LBP due to mechanical cause. Exclusion criteria: hypersensitivity to aspirin or NSAIDs, gastroduodenal ulcer, history of gastrointestinal bleeding, severe cardiac, hepatic or renal insufficiency, severe hypertension, history of maemopoietic or bleeding disorders, pregnancy, sensory or motor deficits in lower extremities, and infective, inflammatory, neoplastic, metabolic or structural cause. | |

| Interventions | NSAIDs (i): diclofenac 75 mg b.i.d., 14 days (N=66). NSAIDs (ii): piroxicam 20 mg b.i.d. 2 days plus once a day for 12 days (N=66). | |

| Outcomes | Mean pain intensity at rest (VAS) at baseline and after 4, 8 and 15 days: (i) 70.0, 43.3, 30.6, 22.7; (ii) 67.1, 44.5, 27.8, 21.0; mean finger tip to floor distance: (i) 28.6, 20.3, 17.8, 14.7; (ii) 29.4, 21.5, 16.9, 14.9. No. (%) of patients improved after 14 days: (i) 54 (82%), 58 (88%). Not significant. Side effects (i) 13 patients (1 withdrawal), (ii) 12 patients (4 withdrawals). | |

| Notes | Methodological quality: randomization ‐; treatment allocation ‐; withdrawals +; co‐interventions ‐; patients blinded +; outcomes blinded +; care providers blinded +; intention‐to‐treat +; compliance ‐; baseline similarity +; follow‐up ‐. Total score = 6. Clinical relevance: patients description + intervention description + outcome measures + effect size ‐ benefits/ harms ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Randomization procedure not described. |

Basmajian 1989.

| Methods | RCT; double‐blind, multicenter. Randomization procedure not described. | |

| Participants | 175 Patients from 18 clinics. Inclusion criteria: acute incidence of trauma or musculoskeletal strain, rigid criteria of clinical pain and spasm for the previous 7 days were required. | |

| Interventions | NSAID (i): diflunisal capsules 500 mg twice per day (N=44). NSAID plus muscle relaxant (ii): diflunisal capsules 500 mg + 5 mg cyclobenzaprine twice per day (N=43). Muscle relaxant (iii): cyclobenzaprine (flexeril) capsules 5 mg twice per day (N=43). Reference treatment (iv): placebo capsules twice per day (N=45). | |

| Outcomes | No. of patients reporting marked improvement after 2, 4 and 7 days: (i) 10, 14, 24 (ii) 10, 14, 31 (iii) 8, 18, 30 (iv) 10, 14, 20. Group (ii) significantly better after 4 days (based on total distribution). No other significant differences. No significant side effects were reported. | |

| Notes | Methodological quality: randomization ‐; treatment allocation ‐; withdrawals +; co‐interventions ‐; patients blinded +; outcomes blinded +; care providers blinded +; intention‐to‐treat +; compliance ‐; baseline similarity ‐; follow‐up ‐. Total score = 5. Unclear presentation of results. Clinical relevance: patients description ‐ intervention description + outcome measures ‐ effect size ‐ benefits/ harms ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Randomization procedure not described. |

Berry 1982.

| Methods | RCT; double‐blind, cross‐over. Randomization procedure not described. | |

| Participants | 37 Patients, 24 women and 13 men, aged 32 to 79 years, median duration of back pain 3 years. Inclusion criteria: adult patients with chronic back pain (> 3 months) due to spondylosis, degenerative disease, sciatica, or nonspecific pain. Exclusion criteria: malignancy, infection, spondylolisthesis, abnormal alkaline phosphatase level, ESR > 25 mm/hr. | |

| Interventions | NSAID (i): naproxen sodium 275 mg capsules, 2 times 2 capsules per day, 14 days (N=37 in cross‐over design). NSAID (ii): diflunisal 250 mg capsules, 2 times 2 capsules per day, 14 days (N=37 in cross‐over design). Reference treatment (iii): placebo capsules (N=37 in cross‐over design). | |

| Outcomes | Decrease in pain by visual analogue scale. Group (i) reduction of pain (ii) no change (iii) increase of pain. Data in graphs. Group (i) significantly better than (iii) and somewhat better than (ii). Side effects similar in the three groups (i) 18 (ii) 18 (iii) 16. | |

| Notes | Methodological quality: randomization ‐; treatment allocation ‐; withdrawals +; co‐interventions ‐; patients blinded +; outcomes blinded +; care providers blinded +; intention‐to‐treat +; compliance ‐; baseline similarity +; follow‐up ‐. Total score = 6. Clinical relevance: patients description + intervention description + outcome measures + effect size + benefits/ harms + | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Randomization procedure not described. |

Berry 1988b.

| Methods | RCT; double‐blind, multicenter study. Randomization procedure not described. | |

| Participants | 105 patients, 58 men, 47 women, from seven general practitioners. Inclusion criteria: acute low back pain of at least moderate severity, recent onset, limitation of movement of the lumbar spine, age 18 to 65 years. Exclusion criteria: pregnancy or lactation, malignancy, osteoporosis, history of lumbar spine surgery, significant systemic disease, allergy or sensitivity to study drugs, rheumatic diseases. | |

| Interventions | NSAIDs (i): ibuprofen 400 mg plus placebo tid, 7 days (N=54). Reference treatment (ii): ibuprofen 400 mg plus tizanidine 4 mg tid, 7 days (N=51). | |

| Outcomes | Mean (SD) changes in pain at rest (VAS) between baseline and day 3 and baseline and day 7: (i) 16 (24.9), 33 (32.9); (ii) 18 (25.3), 29 (43.3). Number (%) of patient improved on functional status (restriction of movement) after 3 days: (i) 32 (60%), (ii) 32 (64%). No. (%) of patients improved according to physician after 3 and 7 days: (i) 36 (67%), 42 (81%); (ii) 39 (76%), 39 (85%). Not significant. Side effects: (i) 17 patients, (ii) 23 patients. | |

| Notes | Methodological quality: randomization ‐; treatment allocation ‐; withdrawals +; co‐interventions +; patients blinded +; outcomes blinded +; care providers blinded +; intention‐to‐treat +; compliance ‐; baseline similarity +; follow‐up ‐. Total score = 7. Clinical relevance: patients description + intervention description + outcome measures + effect size ‐ benefits/ harms ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Randomization procedure not described. |

Birbara 2003.

| Methods | RCT; "flare design"; double‐blind; double‐dummy; multicentre. Randomised according to computer generated random allocation table | |

| Participants | 314 outpatients, 190 women, 124 men from 46 centres in USA. Inclusion criteria: age 18 to 75 years; LBP >= 3 months, usage NSAID or Acetaminophen >= 30 days; pain without radiation to an extremity and without neurological signs or pain with radiation to an extremity, but not below the knee and without neurological signs; flare criteria after washout period. Exclusion criteria: secondary cause of LBP; surgery for LBP in previous 6 months; symptomatic depression; drug abuse in past 5 years; usage opioids > 4 days in previous month; corticosteroid injection in previous 3 months | |

| Interventions | NSAIDs (i): Etoricoxib 60 mg/ day, 12 weeks (N=101). NSAIDs (ii): Etoricoxib 90 mg/ day, 12 weeks (N=106). Reference treatment (iii): placebo, daily, 12 weeks (N=107). | |

| Outcomes | Mean difference (95% CI) pain intensity scale (100 mm VAS) at 12 weeks; (i vs iii) ‐10.45 (‐16.77 to ‐4.14); (ii vs iii) ‐7.5 (‐13.71 to ‐1.28) Mean difference (95% CI) LBP bothersomeness scale over 12 weeks (4‐pt Likert, 0= not at all, 4= extremely); (i vs iii) ‐0.38 (‐0.62 to ‐0.14); (ii vs iii) ‐0.33 (‐0.57 to ‐0.09) Mean difference (95% CI) RMDQ (0‐ 24 pt scale) over 12 weeks; (i vs iii) ‐2.42 (‐3.87 to ‐0.98); (ii vs iii) ‐2.06 (‐3.46 to ‐0.65) Side effects: (i) 60 patients (14 withdrew); (ii) 56 patients (17 withdrew); (iii) 51 patients (10 withdrew) | |

| Notes | Methodological quality: randomization +; treatment allocation +; withdrawals ‐; co‐interventions ‐; patients blinded +; outcomes blinded +; care providers blinded +; intention‐to‐treat ‐; compliance ‐; baseline similarity +; follow‐up +. Total score = 7. Clinical relevance: patients description + intervention description + outcome measures + effect size ‐ benefits/ harms ‐ |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Adequate ‐ Randomised according to computer generated random allocation table |

Blazek 1986.

| Methods | RCT; double‐blind. Randomization procedure not described. | |

| Participants | 28 Patients, 20 women and 8 men. Inclusion criteria: lumbo‐ischialgia and femoralgia due to herniated disc. Exclusion criteria: gastrointestinal, hepatic or renal disease. | |

| Interventions | NSAID (i): diclofenac 25‐mg capsules, four times per day first 4 days and three times per day next 8 days, 12 days (N=14). NSAID (ii): biarison 300‐mg capsules, four times per day first 4 days and three times per day next 8 days, 12 days (N=14). | |

| Outcomes | Average improvement on ordinal 5‐points scale (0= no response, 4=very good response) during and after the intervention period of 12 days according to physician and patient (i) 2.6 and 2.8 (ii) 2.8 and 3. No significant differences in recovery rate. Side effects: mild side effects in three patients in each group. | |

| Notes | Methodological quality: randomization ‐; treatment allocation ‐; withdrawals +; co‐interventions +; patients blinded +; outcomes blinded +; care providers blinded +; intention‐to‐treat +; compliance ‐; baseline similarity ‐; follow‐up ‐. Total score = 6. Clinical relevance: patients description + intervention description + outcome measures + effect size ‐ benefits/ harms ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Randomization procedure not described. |

Borenstein 1990.

| Methods | RCT; open‐label. Randomization procedure not described. | |

| Participants | 40 patients with acute low back pain referred to an orthopedist or rheumatologist, 28 men, 12 women. Inclusion criteria: acute muscle spasm with mild to moderate back pain, duration 10 days or less, age 18 to 60 years. Exclusion criteria: severe pain, hypersensitivity to study drugs, history of peptic ulcer or bleeding disorders, hypertension, hepatic, cardiovascular or renal disease, marked obesity, neurologic symptoms including sciatica history of back surgery, lactation or pregnancy. | |