This cohort study investigates out-of-pocket spending for ultra-expensive drugs in the Medicare Part D program vs commercial insurance from 2013 through 2019.

Key Points

Question

Is out-of-pocket spending for ultra-expensive drugs larger for Medicare Part D beneficiaries than for patients with commercial insurance?

Findings

This cohort study including 37 324 Part D beneficiaries and 24 159 commercially insured individuals showed that Medicare Part D beneficiaries without low-income subsidies spent 2.5 times more out of pocket on ultra-expensive drugs and were subject to greater variation in this spending compared with commercially insured patients aged 45 to 64 years.

Meaning

Recent legislation establishing a $2000 out-of-pocket cap in Part D has the potential to lower out-of-pocket costs for more than 125 000 Part D beneficiaries who use ultra-expensive drugs and are ineligible for low-income subsidies, thus ameliorating increases in out-of-pocket spending when transitioning from commercial insurance to Part D.

Abstract

Importance

Little is known about how out-of-pocket burden differs between Medicare and commercial insurance for ultra-expensive drugs.

Objective

To investigate out-of-pocket spending for ultra-expensive drugs in the Medicare Part D program vs commercial insurance.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a retrospective, population-based cohort study of individuals using ultra-expensive drugs included in a 20% nationally random sample of prescription drug claims from Medicare Part D and individuals aged 45 to 64 years using ultra-expensive drugs included in a large national convenience sample of outpatient pharmaceutical claims from commercial insurance plans. Claims data from 2013 through 2019 were used, and data were analyzed in February 2023.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Claims-weighted mean out-of-pocket spending per beneficiary per drug by insurance type, plan, and age.

Results

In 2019, 37 324 and 24 159 individuals using ultra-expensive drugs were identified in the 20% Part D and commercial samples, respectively (mean [SD] age, 66.2 [11.7] years; 54.9% female). A statistically significant higher share of commercial enrollees vs Part D beneficiaries were female (61.0% vs 51.0%; P < .001), and a statistically significantly lower share were using 3 or more branded medications (28.7% vs 42.6%; P < .001). Mean out-of-pocket spending per beneficiary per drug in 2019 was $4478 in Part D (median [IQR], $4169 [$3369-$5947]) compared with $1821 for commercial (median [IQR], $1272 [$703-$1924]); these differences were statistically significant every year. Differences in out-of-pocket spending comparing commercial enrollees aged 60 to 64 years and Part D beneficiaries aged 65 to 69 years exhibited similar magnitudes and trends. By plan, mean out-of-pocket spending per beneficiary per drug in 2019 was $4301 (median [IQR], $4131 [$3000-$6048]) in Medicare Advantage prescription drug (MAPD) plans, $4575 (median [IQR], $4190 [$3305-$5799]) in stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs), $1208 (median [IQR], $752 [$317-$1240]) in health maintenance organization plans, $1569 (median [IQR], $838 [$481-$1472]) in preferred provider organization plans, and $4077 (median [IQR], $2882 [$1075-$4226]) in high-deductible health plans. There were no statistically significant differences between MAPD plans and stand-alone PDPs in any study year. Mean out-of-pocket spending was statistically significantly higher in MAPD plans compared with health maintenance organization plans and in stand-alone PDPs compared with preferred provider organization plans in each study year.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study demonstrated that the $2000 out-of-pocket cap included in the Inflation Reduction Act may substantially moderate the potential increase in spending faced by individuals who use ultra-expensive drugs when moving from commercial insurance to Part D coverage.

Introduction

Drug manufacturers are increasingly launching new drugs with ultra-expensive list prices while also increasing the list prices of existing drugs to the ultra-expensive level.1 Ultra-expensive drugs are defined as drugs with mean annual total spending per person using the medication greater than the US gross domestic product per capita.1 From 2012 to 2018, spending on ultra-expensive drugs in Medicare Part D grew from 1.5% to 19.3% of total spending on branded drugs. However, a very small percentage of Part D beneficiaries use these drugs (0.5% of all Part D beneficiaries in 2018).

The clinical value of some of these ultra-expensive drugs has been questioned. Health technology assessment agencies in France, Canada, and Germany have concluded that approximately three-quarters of these drugs offer low or no clinical benefit when compared with conventional therapy.2 Nevertheless, patients in the US are often expected to pay a considerable portion of the list price for these ultra-expensive drugs. In Medicare Part D, patient cost sharing is typically between 25% and 33% of the list price for specialty drugs, defined in 2020 as drugs costing more than $670 per month.3

Previous studies have documented the out-of-pocket burden for some specialty and high-cost cancer drugs, mostly focusing on Medicare Part D.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 However, ultra-expensive drugs represent an especially expensive subset of specialty drugs given that their total monthly costs can far exceed the $670-per-month threshold. Additionally, many of these studies focus on cancer drugs, which comprised only 21% of all ultra-expensive drugs in 2018.1 Finally, little is known about how out-of-pocket burden differs between Medicare and commercial insurance for ultra-expensive drugs given differences in cost sharing and out-of-pocket maximum policies and the documented increase over time in the prevalence and utilization of ultra-expensive drugs.

In this cohort study, we investigate the amount paid annually by patients for ultra-expensive drugs in the Medicare Part D program compared with patients with commercial insurance between 2013 and 2019. Understanding these differences is particularly important given the prescription drug provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).12 During this study period, Medicare Part D placed no limit on the total amount of out-of-pocket spending paid by Medicare beneficiaries. But the IRA amends the Part D benefit design by removing the 5% beneficiary coinsurance above the catastrophic coverage threshold and capping out-of-pocket spending at $3250 in 2024 and $2000 in 2025.13 Several recent studies have examined the potential effects of previously proposed out-of-pocket maximums for prescription drug use in Medicare Part D.14,15 This study’s findings regarding patients’ out-of-pocket spending in Medicare Part D compared with those with commercial insurance before implementation of the IRA will serve as a baseline for understanding how the new legislation’s out-of-pocket cap may affect the patient transition from commercial insurance to Medicare Part D.

Methods

Study Sample

Ultra-expensive drugs are defined as prescription drugs with annual mean spending per Medicare Part D beneficiary in excess of the US gross domestic product per capita in that year. The annual mean spending per beneficiary is defined as total Part D drug spending, including all program and beneficiary spending for beneficiaries taking the drug. It is based on the drug cost before any concessions in the supply chain (eg, rebates, direct and indirect remuneration). Given that the study focus is on patient cost sharing and not amounts paid by the Medicare program or health insurers, this approach will not affect the main results and represents an upper bound of the amount that insurers pay. Moreover, a previous study found that the difference between the net price and list price is lower for ultra-expensive drugs than for non–ultra-expensive drugs.1

We identified specific ultra-expensive drugs by product name using the publicly available Medicare Part D Spending by Drug data from 2013 though 2019. This approach allows for a common set of drugs to compare across payers.

This study was exempt from review by the institutional review board at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health owing to use of deidentified data. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.16

Data

To identify out-of-pocket spending for the Part D population, the Part D Prescription Drug Event (PDE) data set was used. It is a 20% nationally representative, random sample of all Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in prescription drug plans.17 This data set provides the product name, total drug costs, and total amount paid by the beneficiary (co-payment, coinsurance, and deductible are included, though not separately identifiable) for each drug claim. Beneficiaries in stand-alone, fee-for-service prescription drug plans (PDPs) and beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage prescription drug (MAPD) plans who filled a prescription for an ultra-expensive drug were included. Claims were excluded if they did not include a product name or unique enrollee identifier or had a missing or negative payment value (<0.001% of claims annually). The PDE data were linked with the Master Beneficiary Summary File to identify and exclude beneficiaries who received low-income subsidies, as there is no comparable subsidy program for commercial insurance.

For the commercially insured population, outpatient pharmaceutical claims from Merative MarketScan were used. This data set covers more than 120 employers and 40 health plans18 and provides total drug costs and amounts paid by the patient at the point-of-sale, including co-payment, coinsurance, and deductible, for each claim. Out-of-pocket spending was defined as the sum of co-payments, coinsurance, and deductible. Claims for ultra-expensive drugs were identified by matching on national drug code from the Part D PDE file. We restricted analysis to beneficiaries aged 45 to 64 years who filled a prescription for an ultra-expensive drug to create a sample more comparable with Medicare beneficiaries. Claims were excluded from this analytic data set if they did not include a product name or unique enrollee identifier or had a missing or negative payment value (1.3%-1.7% of claims annually). MarketScan’s outpatient pharmaceutical claims do not include beneficiaries older than 64 years, thus preventing direct comparison with equivalently aged Part D beneficiaries.

Statistical Analysis

The median, IQR, and claims-weighted mean of drug-level out-of-pocket spending per beneficiary were computed for each year by insurance type (Part D and commercial), plan type, and age cohort. Between Part D and commercial insurance, we compared the claims-weighted mean among all beneficiaries and among beneficiaries aged 60 to 64 years and beneficiaries aged 65 to 69 years to better understand the potential transition from commercial insurance to Part D coverage. We also compared beneficiaries in Part D MAPD plans vs commercial health maintenance organization (HMO) plans and beneficiaries in Part D PDPs vs commercial preferred provider organization (PPO) plans given that plan self-selection may make these more comparable groups. When examining plan types, comparison was restricted to individuals who did not switch plans during the year.

Within Part D, we compared the claims-weighted mean of drug-level out-of-pocket spending per beneficiary by plan type (PDP vs MAPD) and age cohort (65-69 years vs <65, 70-74, ≥75 years) for each year. Within commercial insurance, we compared the claims-weighted mean by plan type (HMO vs PPO and high-deductible health plans [HDHPs]) and age cohort (45-49 years vs 50-54, 55-59, and 60-64 years).

We additionally conducted a subgroup analysis that excluded claims where beneficiaries received third-party payments for the use of a particular drug, as these payments would have reduced beneficiary liability. For Part D beneficiaries, these payments may come from group health plans, worker’s compensation, or federal programs like the Veterans Health Administration17; for commercial enrollees, this includes coordination of benefits payments and potential Medicare benefits.19

Finally, we compared out-of-pocket spending per beneficiary by insurance type for each of the top 10 ultra-expensive drugs based on total Medicare Part D spending in 2019. Costs are presented in nominal dollars not adjusted for inflation.

Differences in study sample characteristics were assessed using Pearson χ2 tests. Differences in claims-weighted means between groups of interest were assessed for statistical significance using ordinary least squares regression. The threshold for statistical significance was α = .05 using 2-sided tests. All analyses were conducted in Stata, version 14.2 (StataCorp), in February 2023.

Results

Characteristics of Beneficiaries Using Ultra-Expensive Drugs

In 2019, 37 324 and 24 159 individuals who used ultra-expensive drugs were identified in the 20% Part D and MarketScan samples, respectively (mean [SD] age, 66.2 [11.7] years; 54.9% female); a statistically significant higher share of commercial insurance enrollees using ultra-expensive drugs were female (61.0% vs 51.0%; P < .001), and a statistically significant lower share of commercial enrollees were using 3 or more branded medications (28.7% vs 42.6%; P < .001) (Table 1). In Part D, 10.3% of beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drug were younger than 65 years, 21.0% were aged 65 to 69 years, 25.0% were aged 70 to 74 years, and 43.7% were 75 years or older. By plan, 35.3% of Part D beneficiaries were enrolled in MAPD plans, and 64.8% were enrolled in stand-alone PDPs. Among commercial enrollees using ultra-expensive drugs, 21.3% were aged 45 to 49 years, 23.3% were aged 50 to 54 years, 27.9% were aged 55 to 59 years, and 27.6% were aged 60 to 64 years; 12.8% of commercial enrollees were enrolled in HMOs, 49.3% were enrolled in PPOs, 10.6% were enrolled in HDHPs, and 27.3% were enrolled in other plan types. Descriptive characteristics for previous study years are reported in eTables 1 through 6 in Supplement 1. Since 2013, the share of Part D beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs and enrolled in MAPD plans increased from 29.9% to 35.3% (with a corresponding decrease in the share of beneficiaries in stand-alone PDPs), and the share of commercial enrollees using ultra-expensive drugs and enrolled in HDHPs increased from 3.8% to 10.6% (eTables 1-6 in Supplement 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Beneficiaries Using Ultra-Expensive Drugs, 2019.

| Characteristic | No. (%)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Part D (n = 37 324) | Commercial insurance (n = 24 159) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 19 021 (51.0)b | 14 731 (61.0) |

| Male | 18 303 (49.0) | 9428 (39.0) |

| Age, y | <65: 3840 (10.3) | 45-49: 5143 (21.3) |

| 65-69: 7854 (21.0) | 50-54: 5628 (23.3) | |

| 70-74: 9334 (25.0) | 55-59: 6730 (27.9) | |

| ≥75: 16 296 (43.7) | 60-64: 6658 (27.6) | |

| Using ≥3 branded medications | 15 898 (42.6)b | 6942 (28.7) |

| Plan typec | Part D (n = 37 245) | Commercial insurance (n = 23 602) |

| MAPD: 13 130 (35.3) | HMO: 3029 (12.8) | |

| Stand-alone PDP: 24 115 (64.8) | PPO: 11 639 (49.3) | |

| HDHP: 2496 (10.6) | ||

| Other: 6438 (27.3) | ||

Abbreviations: HDHP, high-deductible health plan; HMO, health maintenance organization; MAPD, Medicare Advantage prescription drug plan; PDP, prescription drug plan; PPO, preferred provider organization.

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

P < .001 using Pearson χ2 test.

Excludes beneficiaries who switched plans during the year.

Overall Use and Spending Attributable to Ultra-Expensive Drugs

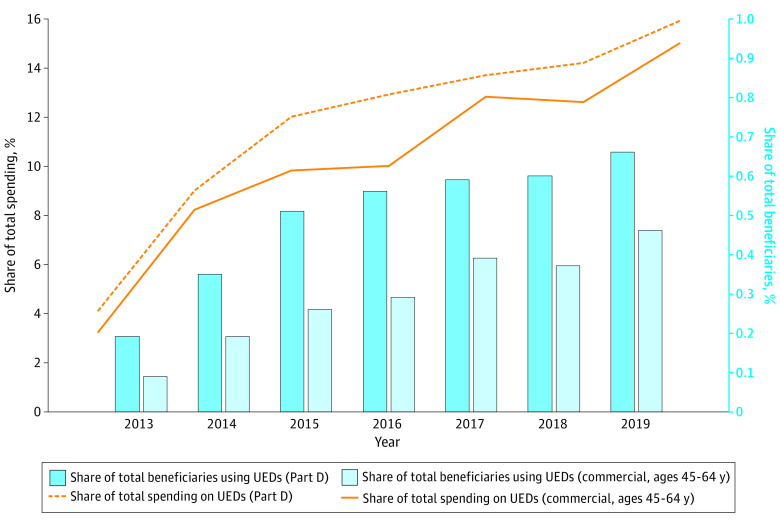

Medicare Part D had a slightly higher percentage of beneficiaries taking ultra-expensive drugs and spent a slightly greater percentage of total spending on ultra-expensive drugs compared with commercial insurance (Figure). The share of Part D beneficiaries taking ultra-expensive drugs grew from 0.19% to 0.66% from 2013 to 2019, while the share of commercial insurance beneficiaries aged 45 to 64 years who use ultra-expensive drugs increased from 0.09% to 0.46%. Over the same time period, the share of total Part D spending attributable to ultra-expensive drugs grew from 4.1% to 15.9%, while the share of total spending among the commercially insured population that is attributable to ultra-expensive drugs increased from 3.2% to 15.0%.

Figure. Share of Total Beneficiaries and Total Spending Attributable to Ultra-Expensive Drugs (UEDs) in Medicare Part D and Commercial Insurance, 2013-2019.

Interinsurer Comparison of Out-of-Pocket Spending on Ultra-Expensive Drugs

In 2019, 134 and 136 ultra-expensive drugs were represented in the study samples for Part D and commercial insurance, respectively (eTable 7 in Supplement 1). Mean out-of-pocket spending per beneficiary per drug in 2019 was $4478 for Part D (median [IQR], $4169 [$3369-$5947]) compared with $1821 for commercial insurance (median [IQR], $1272 [$703-$1924]); differences in the means were statistically significant in every year of the study period (Table 2). In 2013, mean out-of-pocket spending was 4.6 times higher for Part D beneficiaries, and this difference decreased to 2.5 times higher in 2019. Differences in out-of-pocket spending comparing commercial enrollees aged 60 to 64 years and Part D beneficiaries aged 65 to 69 years exhibited similar magnitudes and trends (Table 2).

Table 2. Annual Out-of-Pocket Spending per Beneficiary per Ultra-Expensive Drug by Subgroup, Interinsurer Comparisons, 2013-2019.

| Year | Measurementa | Overall, $ | Age subgroups, $ | Plan subgroups, $b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial insurance | Part D | Commercial insurance, 60-64 y | Part D, 65-69 y | Commercial insurance, HMO | Part D, MAPD | Commercial insurance, PPO | Part D, stand-alone PDP | ||

| 2019 | Mean | 1821 | 4478c | 1735 | 4496c | 1208 | 4301c | 1569 | 4575c |

| Median (IQR) | 1272 (703-1924) | 4169 (3369-5947) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 2018 | Mean | 1522 | 4703c | 1420 | 4679c | 1118 | 4451c | 1274 | 4838c |

| Median (IQR) | 1116 (615-1633) | 4437 (3579-5605) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 2017 | Mean | 1283 | 4600c | 1217 | 4499c | 921 | 4443c | 1107 | 4679c |

| Median (IQR) | 1056 (663-1523) | 4344 (3856-5769) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 2016 | Mean | 1105 | 4463c | 980 | 4476c | 742 | 4431c | 1078 | 4484c |

| Median (IQR) | 1001 (581-1356) | 4511 (3800-5639) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 2015 | Mean | 1071 | 4430c | 925 | 4555c | 816 | 4546c | 1062 | 4381c |

| Median (IQR) | 743 (529-1028) | 4507 (3477-6119) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 2014 | Mean | 896 | 4094c | 811 | 4239c | 546 | 4224c | 805 | 4036c |

| Median (IQR) | 820 (634-1187) | 4015 (3448-5751) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 2013 | Mean | 836 | 3861c | 1034 | 3822d | 507 | 4091c | 857 | 3779c |

| Median (IQR) | 789 (563-1088) | 3893 (3473-5613) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

Abbreviation: HMO, health maintenance organization; MAPD, Medicare Advantage prescription drug plan; NA, not applicable; PDP, prescription drug plan; PPO, preferred provider organization.

Means are volume weighted based on the number of claims per drug.

For subgroup comparisons, MAPD is compared with HMO and PDP is compared with PPO.

P < .001.

P < .05.

At the plan level, there was statistically significant higher mean out-of-pocket spending in Part D MAPD plans compared with commercial HMO plans and for Part D stand-alone PDPs compared with commercial PPO plans in each study year (Table 2). Mean out-of-pocket spending was 8 times larger in MAPD plans compared with HMO plans in 2013 ($4091 vs $507); this difference had decreased to 3.6 times larger in 2019 ($4301 vs $1208). Mean out-of-pocket spending was 4.4 times larger in stand-alone PDPs compared with PPOs in 2013 ($3779 vs $857) and 2.9 times larger in 2019 ($4575 vs $1569). In the subgroup analysis that excluded claims where beneficiaries received third-party payments, mean out-of-pocket spending per beneficiary per drug in 2019 was $1822 in commercial insurance and $6038 in Part D (eTable 8 in Supplement 1).

Intra-insurer Comparison of Out-of-Pocket Spending on Ultra-Expensive Drugs

A greater number of ultra-expensive drugs were used by patients in Part D stand-alone PDPs compared with patients in MAPD plans and in commercial PPOs compared with HMOs and HDHPs (eTable 7 in Supplement 1). There were no statistically significant differences in out-of-pocket spending between Part D MAPD plans and stand-alone PDPs in any study year (Table 3). Among commercial enrollees, those in HDHPs had statistically significant higher out-of-pocket spending compared with those in HMOs for every study year; commercial PPO enrollees also paid more out of pocket than those in HMOs, though the differences were statistically significant in only 5 study years (Table 3). In 2019, mean out-of-pocket spending per beneficiary per drug was $1208 in HMOs, $1569 in PPOs, and $4077 in HDHPs.

Table 3. Annual Out-of-Pocket Spending per Beneficiary per Ultra-Expensive Drug by Subgroup, Intra-Insurer Comparisons, 2013-2019.

| Year | Measurementa | Part D, $ | Commercial insurance, $ | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plan subgroup | Age subgroup | Plan subgroup | Age subgroup | |||||||||||

| MAPD | Stand-alone PDP | 65-69 y [Reference] | 70-74 y | ≥75 y | <65 y | HMO [Reference] | PPO | HDHP | 45-49 y [Reference] | 50-54 y | 55-59 y | 60-64 y | ||

| 2019 | Mean | 4301 | 4575 | 4496 | 4614 | 4257 | 5142b | 1208 | 1569c | 4077d | 1963 | 1865 | 1779 | 1735b |

| Median (IQR) | 4131 (3000-6048) | 4190 (3305-5799) | 3928 (2942-5844) | 4139 (3317-5721) | 3536 (2659-4895) | 4837 (3609-7107) | 752 (317-1240) | 838 (481-1472) | 2882 (1075-4226) | 1094 (433-1831) | 1226 (501-2053) | 1239 (586-1956) | 1142 (401-1801) | |

| 2018 | Mean | 4451 | 4838 | 4679 | 4805 | 4524 | 5257 | 1118 | 1274 | 3751d | 1674 | 1517 | 1532 | 1420c |

| Median (IQR) | 4055 (3263-5566) | 4419 (3697-6016) | 4123 (3077-5740) | 4214 (3140-5471) | 3905 (2888-4892) | 5409 (4082-7521) | 872 (431- 1367) | 738 (380-1378) | 3081 (1494-4124) | 966 (406-1493) | 1200 (625-1639) | 1174 (645-1619) | 830 (300-1549) | |

| 2017 | Mean | 4443 | 4679 | 4499 | 4703 | 4468 | 5115b | 921 | 1107b | 3266d | 1380 | 1259 | 1318 | 1217c |

| Median (IQR) | 4168 (3270-5225) | 4516 (3846-5869) | 4204 (3013-5005) | 4342 (3467-5514) | 4001 (3065-5091) | 5269 (4082-7491) | 727 (350-1122) | 843 (501-1169) | 2757 (1736-3727) | 837 (343-1406) | 943 (435-1392) | 958 (520-1609) | 980 (537-1362) | |

| 2016 | Mean | 4431 | 4484 | 4476 | 4518 | 4207 | 5235b | 742 | 1078d | 2661d | 1163 | 1162 | 1175 | 980b |

| Median (IQR) | 4127 (3425-5460) | 4515 (3804-5638) | 4543 (3651-5660) | 4238 (3612-5134) | 3871 (2978-5007) | 5004 (3943-7107) | 561 (310-853) | 840 (506-1236) | 2546 (1631-3583) | 964 (521-1325) | 1008 (481-1444) | 761 (432-1367) | 790 (476-1171) | |

| 2015 | Mean | 4546 | 4381 | 4555 | 4443 | 4039b | 5393c | 816 | 1062c | 2961d | 1098 | 1049 | 1053 | 925b |

| Median (IQR) | 4209 (3057-5979) | 4355 (3488-6227) | 4229 (3239-5198) | 4309 (3435-5009) | 4138 (3137-5181) | 5401 (3816-7059) | 377 (196-721) | 609 (431-901) | 2546 (1414-3363) | 748 (483-1362) | 606 (327-963) | 622 (357-1116) | 600 (353-811) | |

| 2014 | Mean | 4224 | 4036 | 4239 | 4205 | 3737 | 4818 | 546 | 805b | 2264d | 852 | 870 | 836 | 811 |

| Median (IQR) | 4097 (3259-5475) | 3887 (3315-5826) | 3987 (3165-5816) | 4009 (3365-4958) | 3654 (2789-4823) | 4440 (3685-5907) | 370 (180-608) | 676 (502-906) | 1985 (1015-2965) | 764 (479-1034) | 722 (466-1054) | 721 (525-929) | 680 (442-1084) | |

| 2013 | Mean | 4091 | 3779 | 3822 | 4150 | 3543 | 4589b | 507 | 857 | 2309c | 756 | 670 | 695 | 1034 |

| Median (IQR) | 4332 (3390-6204) | 3763 (3361-5208) | 3809 (3144-5811) | 3901 (2802-4568) | 3426 (2067-4097) | 4423 (3226-6404) | 286 (83-503) | 753 (502-1024) | 1981 (770-3246) | 640 (342-925) | 596 (352-876) | 595 (287-804) | 514 (365-893) | |

Abbreviations: HDHP, high-deductible health plan; HMO, health maintenance organization; MAPD, Medicare Advantage prescription drug plan; PDP, prescription drug plan; PPO, preferred provider organization.

Means are volume weighted based on claims per drug.

P < .05.

P < .01.

P < .001.

Part D beneficiaries younger than 65 years had statistically significant higher out-of-pocket spending in 5 years of the study compared with those aged 65 to 69 years (Table 3). Among enrollees with commercial insurance, patients aged 60 to 64 years tended to spend the least out of pocket compared with those aged 45 to 49 years, and these differences were statistically significant in 5 study years (Table 3).

Out-of-Pocket Spending on Ultra-Expensive Drugs With the Highest Part D Sales

Among the top 10 ultra-expensive drugs measured by total Part D sales in 2019, the mean out-of-pocket spending per Part D beneficiary ranged from $1596 for ustekinumab to $5692 for ruxolitinib and was statistically significantly greater for 9 of 10 drugs compared with commercial enrollees (Table 4). Mean out-of-pocket spending per commercial enrollee ranged from $947 for pomalidomide to $2470 for ledipasvir-sofosbuvir.

Table 4. Out-of-Pocket Spending per Beneficiary for Top-Selling Ultra-Expensive Drugs, 2019a.

| Product (Part D spending, $ millions) | Measurement | Overall, $ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Part D | Commercial insurance | ||

| Lenalidomide (4674) | Mean | 5401 (n = 6491)b | 1248 (n = 1716) |

| Median (IQR) | 4452 (1152-9171) | 300 (70-1083) | |

| Ibrutinib (2440) | Mean | 4792 (n = 3917)b | 1548 (n = 795) |

| Median (IQR) | 4308 (1017-8642) | 540 (108-1734) | |

| Palbociclib (1826) | Mean | 4076 (n = 2877)b | 1998 (n = 1333) |

| Median (IQR) | 3643 (564-6791) | 300 (24-1572) | |

| Enzalutamide (1421) | Mean | 2980 (n = 3067)b | 1181 (n = 390) |

| Median (IQR) | 2427 (268-4806) | 250 (6.3-1000) | |

| Pomalidomide (1192) | Mean | 4816 (n = 1689)b | 947 (n = 402) |

| Median (IQR) | 3639 (896-8096) | 150 (0-672) | |

| Dimethyl fumarate (1131) | Mean | 3997 (n = 1191)b | 2144 (n = 2619) |

| Median (IQR) | 5025 (1168-6048) | 600 (240-2057) | |

| Ruxolitinib (1125) | Mean | 5692 (n = 1623)b | 1991 (n = 404) |

| Median (IQR) | 5726 (2211-9551) | 320 (0-1006) | |

| Ustekinumab (796) | Mean | 1596 (n = 817) | 1760 (n = 4546) |

| Median (IQR) | 345 (120-2509) | 390 (150-1473) | |

| Nintedanib (790) | Mean | 3666 (n = 1838)b | 1444 (n = 211) |

| Median (IQR) | 3285 (875-6101) | 300 (80-1173) | |

| Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir (745) | Mean | 4603 (n = 567)b | 2470 (n = 595) |

| Median (IQR) | 5111 (3488-6593) | 240 (84-1604) | |

Top-selling is defined in terms of total spending reported in Medicare Part D Spending by Drug data.

P < .001.

Discussion

Medicare Part D beneficiaries without low-income subsidies spent 2.5 times more out of pocket on ultra-expensive drugs compared with commercially insured patients aged 45 to 64 years in 2019. This difference is even greater when considering only patients who received no payments from third parties like group health plans or governmental programs like the Veterans Health Administration. These individuals may have greater difficulty covering these payments than patients receiving third-party payments who, for example, can have additional insurance coverage through a working spouse earning additional income. The present findings also indicate the growing burden of ultra-expensive drugs in commercial plans, as evidenced by the more rapidly increasing out-of-pocket costs in this population. Although commercial enrollees may pay less for these drugs, they can face a range of burdensome coverage restrictions.20

There is substantial variation between plan types in the number of ultra-expensive drugs in use. Although more ultra-expensive drugs are used in Part D stand-alone PDPs, out-of-pocket spending on these drugs is not statistically significantly different than in MAPD plans. Because MAPD plans receive capitated payments, they have reason to opt for lower cost sharing to promote greater drug adherence when doing so is cheaper than covering the medical care otherwise required to address the symptoms or complications of chronic conditions,4 but the use of this strategy for ultra-expensive drugs is not supported by the present findings. Among commercial plans, the lower number of drugs represented among HMOs may reflect coverage decisions that make these plans unattractive to patients who use particular ultra-expensive drugs. For commercial HDHPs, the smaller number of drugs may also reflect a selection effect against these plans by patients receiving particular drugs or patients not filling prescriptions for particular drugs due to their very high out-of-pocket cost—a phenomenon for which there is recent evidence.21

The $2000 out-of-pocket cap in the IRA has the potential to substantially ameliorate these shocks in out-of-pocket spending when moving from commercial insurance to Part D coverage. The present 20% sample of 2019 Part D beneficiaries includes 25 029 beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs who paid at least $2000 out of pocket, suggesting that more than 125 000 Part D beneficiaries nationally who use ultra-expensive drugs would have benefited from the IRA out-of-pocket cap in 2019. Given the consistent increase over time in the number of ultra-expensive drugs, even more beneficiaries are likely to be helped by the cap when it is implemented in 2025 and in subsequent years. Lowering out-of-pocket costs may also increase utilization of ultra-expensive drugs or other medications prescribed to those who use these drugs. While this may improve patient outcomes, it also has the potential to increase overall Medicare spending.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we compared out-of-pocket spending across insurance types for a sample of drugs defined by Medicare spending. This sample may not accurately reflect ultra-expensive drugs based on spending in the commercially insured market. For instance, there may be other ultra-expensive drugs that are used only among younger or pediatric populations.

Second, there were several differences between the Part D and commercial insurance study samples. We could not compare similarly aged patients between Part D and commercial insurance because the MarketScan outpatient pharmaceutical claims data do not include patients older than 64 years. However, the present findings were consistent when comparing those closest in age. Additionally, commercial insurance enrollees were less likely to use 3 or more branded medications, indicating a healthier population. This difference is smaller when comparing commercial enrollees aged 60 to 64 years with Part D beneficiaries aged 65 to 69 years (34.0% vs 40.8%).

Finally, patients may use coupons, patient assistance programs, and other forms of co-payment offsets to reduce high out-of-pocket costs at the point-of-sale.22,23 While drug companies offer coupons directly to commercially insured patients, these are prohibited in the Medicare program. Instead, Medicare beneficiaries may get financial support from patient assistance programs operated by nonprofit entities that receive most of their funding from drug companies. Due to confidential agreements, this use is not captured in the present data. However, we reviewed the websites for the 2 largest independent charity programs offering patient assistance programs for Medicare beneficiaries and found that only 5 drugs among the 10 ultra-expensive drugs with the highest Part D spending were covered in July 2022 (eTable 9 in Supplement 1). In contrast, manufacturer-sponsored coupons were advertised as available for nearly all of the drugs included in the sample. If commercially insured patients receive coupons for drugs not included in patient assistance programs, then the difference in out-of-pocket spending for these drugs between Medicare and commercial insurance may be even greater than we observed.

Conclusions

In this cohort study, patient out-of-pocket spending on ultra-expensive drugs was statistically significantly higher among Medicare Part D beneficiaries compared with commercially insured patients from 2013 to 2019. On average, a patient using an ultra-expensive drug who was enrolled in commercial insurance faced a 2.5 times increase in their out-of-pocket spending when moving to Part D. The $2000 out-of-pocket cap included in the IRA will substantially moderate this potential shock for hundreds of thousands of patients, while also potentially increasing utilization of and spending on these drugs.

eTable 1. Characteristics of beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs, 2018

eTable 2. Characteristics of beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs, 2017

eTable 3. Characteristics of beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs, 2016

eTable 4. Characteristics of beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs, 2015

eTable 5. Characteristics of beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs, 2014

eTable 6. Characteristics of beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs, 2013

eTable 7. Number of ultra-expensive drugs by subgroup

eTable 8. Annual claims-weighted mean out-of-pocket spending per beneficiary per ultra-expensive drug among enrollees receiving no third-party payments, inter-insurer comparisons, 2013-2019

eTable 9. Availability of manufacturer-sponsored coupons and patient assistance programs for the top 10 ultra-expensive drugs measured by total Part D spending

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Kang S-Y, Polsky D, Segal JB, Anderson GF. Ultra-expensive drugs and Medicare Part D: spending and beneficiary use up sharply. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(6):1000-1005. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiStefano MJ, Kang S-Y, Yehia F, Morales C, Anderson GF. Assessing the added therapeutic benefit of ultra-expensive drugs. Value Health. 2021;24(3):397-403. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cubanski J, Damico A. Medicare Part D: a first look at prescription drug plans in 2020. Kaiser Family Foundation . November 14, 2019. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicare-part-d-a-first-look-at-prescription-drug-plans-in-2020-issue-brief/

- 4.Parasrampuria S, Sen AP, Anderson GF. Comparing patient OOP spending for specialty drugs in Medicare Part D and employer-sponsored insurance. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(9):388-394. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2020.88489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trish E, Xu J, Joyce G. Medicare beneficiaries face growing out-of-pocket burden for specialty drugs while in catastrophic coverage phase. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(9):1564-1571. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doshi JA, Li P, Pettit AR, Dougherty JS, Flint A, Ladage VP. Reducing out-of-pocket cost barriers to specialty drug use under Medicare Part D: addressing the problem of “too much too soon”. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(3)(suppl):S39-S45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li M, Liao K, Pan IW, Shih YT. Growing financial burden from high-cost targeted oral anticancer medicines among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(11):e1739-e1749. doi: 10.1200/OP.22.00171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen C, Zhao B, Liu L, Shih YT. Financial burden for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia enrolled in Medicare Part D taking targeted oral anticancer medications. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(2):e152-e162. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.014639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dusetzina SB, Huskamp HA, Keating NL. Specialty drug pricing and out-of-pocket spending on orally administered anticancer drugs in Medicare Part D, 2010 to 2019. JAMA. 2019;321(20):2025-2027. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dusetzina SB. Your money or your life—the high cost of cancer drugs under Medicare Part D. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(23):2164-2167. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2202726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trish E, Xu J, Joyce G. Growing number of unsubsidized Part D beneficiaries with catastrophic spending suggests need for an out-of-pocket cap. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1048-1056. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inflation Reduction Act, HR 5376, 117th Cong (2022). Pub L No. 117-169. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text

- 13.Cubanski J, Neuman T, Freed M. Explaining the prescription drug provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act. Kaiser Family Foundation . January 24, 2023. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-inflation-reduction-act/#bullet03

- 14.Parasrampuria S, Anderson GF. Effects of an out-of-pocket maximum in Medicare Part D. Am J Manag Care. 2022;28(2):e55-e62. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2022.88828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gangopadhyaya A, Garrett B. Capping Medicare beneficiary Part D spending at $2,000. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation . March 1, 2022. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/our-research/2022/02/capping-medicare-beneficiary-part-d-spending-at-2000.html#:~:text=A

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Data documentation: Part D Event (PDE) file. Research Data Assistance Center . Accessed April 12, 2023. https://resdac.org/cms-data/files/pde/data-documentation

- 18.Merative MarketScan. IBM . Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.merative.com/real-world-evidence

- 19.2016 Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits Data Dictionary. Truven Health Analytics . Accessed April 12, 2023. https://theclearcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/IBM-MarketScan-Data-Dictionary.pdf

- 20.Chambers JD, Kim DD, Pope EF, Graff JS, Wilkinson CL, Neumann PJ. Specialty drug coverage varies across commercial health plans in the US. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1041-1047. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dusetzina SB, Huskamp HA, Rothman RL, et al. Many Medicare beneficiaries do not fill high-price specialty drug prescriptions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(4):487-496. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang SY, Sen AP, Levy JF, Long J, Alexander GC, Anderson GF. Factors associated with manufacturer drug coupon use at US pharmacies. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(8):e212123. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang S-Y, Sen A, Bai G, Anderson GF. Financial eligibility criteria and medication coverage for independent charity patient assistance programs. JAMA. 2019;322(5):422-429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Characteristics of beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs, 2018

eTable 2. Characteristics of beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs, 2017

eTable 3. Characteristics of beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs, 2016

eTable 4. Characteristics of beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs, 2015

eTable 5. Characteristics of beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs, 2014

eTable 6. Characteristics of beneficiaries using ultra-expensive drugs, 2013

eTable 7. Number of ultra-expensive drugs by subgroup

eTable 8. Annual claims-weighted mean out-of-pocket spending per beneficiary per ultra-expensive drug among enrollees receiving no third-party payments, inter-insurer comparisons, 2013-2019

eTable 9. Availability of manufacturer-sponsored coupons and patient assistance programs for the top 10 ultra-expensive drugs measured by total Part D spending

Data Sharing Statement