Abstract

Introduction:

Racial inequities in birth outcomes persist in the United States. Doula care may help to decrease inequities and improve some perinatal health indicators, but access remains a challenge. Recent doula-related state legislative action seeks to improve access, but the prioritization of equity is unknown. We reviewed recent trends in doula-related legislation and evaluated the extent to which new legislation addresses racial health equity.

Methods:

We conducted a landscape analysis of the LegiScan database to systematically evaluate state legislation mentioning the word “doula” between 2015 and 2020. We identified and applied nine criteria to assess the equity focus of the identified doula-related legislative proposals. Our final sample consisted of 73 bills across 24 states.

Results:

We observed a three-fold increase in doula-related state legislation introduced over the study period, with 15 bills proposed before 2019 and 58 proposed in 2019–2020. Proposed policies varied widely in content and scope, with 53.4% focusing on Medicaid reimbursement for doula care. In total, 12 bills in 7 states became law. Seven of these laws (58.3%) contained measures for Medicaid reimbursement for doula services, but none guaranteed a living wage based on the cost of living or through consultation with doulas. Only two states (28.6%; Virginia and Oregon) that passed Medicaid reimbursement for doulas also addressed other racial equity components.

Conclusions:

There has been an increase in proposed doula-related legislation between 2015 and 2020, but racial health equity is not a focus among the laws that passed. States should consider using racial equity assessments to evaluate proposed doula-related legislation.

Poor health outcomes in pregnancy present an ongoing challenge in the United States. The United States currently has the highest maternal mortality rate in the developed world, and although infant mortality has incrementally improved over time, these improvements are not equally distributed (Belluz, 2020; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020; Hoyert, Uddin, & Miniño, 2020). Indeed, alarming racial disparities in birth outcomes are apparent for birthing people1 and their infants—and are felt most acutely among Black and Indigenous birthing people (Bryant, Worjoloh, Caughey, & Washington, 2010). For example, compared with White birthing people, Black and Indigenous birthing people are three to four times more likely to experience maternal mortality and at least two times more likely to experience infant mortality (CDC, 2020; Creanga et al., 2014; Howell, 2018; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017). Black and Indigenous birthing people also disproportionately suffer from severe maternal and infant morbidity (Howell et al., 2018; Leonard et al., 2019; Schaaf et al., 2013; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017). Low socioeconomic status also predicts adverse birth outcomes, and this association is apparent independent of race or ethnicity (Messer et al., 2008; Ross, Guardino, Dunkel Schetter, & Hobel, 2020; Silva et al., 2008). However, improving socioeconomic status does not eliminate racial disparities in birth outcomes (Berg, Chang, Callaghan, & Whitehead, 2003; CDC, 2007; Howell et al., 2018). Many investigators have posited that these disparities result from broader sociopolitical and structural injustices, which are racially discriminatory and historical in nature (Crear-Perry et al., 2021; Malinaf, Bailey, Feldman, & Bassett, 2020). The persistence of these disparities is also reflective of the historical and contemporary marginalization of Black and Indigenous women2 and the absence of systems to address gendered structural racism and center their needs. We, therefore, acknowledge—as other scholars have (Burger, Evans-Agnew, & Johnson, 2021; Chambers et al., 2021; Crear-Perry et al., 2021; Julian et al., 2020; Scott, Britton, & McLemore, 2019; Taylor, 2020)—the importance of recasting these maternal health disparities as issues of, and direct threats to, reproductive justice. Reproductive justice is a framework that combines theories of reproductive rights and social justice (Ross & Solinger, 2017). The concept was introduced by Black feminists in the early 1990s to better explain the unique needs and intersectional experiences of women of color as they confronted choices related to reproductive health. A reproductive justice framework posits that women have autonomy over their own bodies and the right to have children, to not have children, and to parent children in safe and healthy environments (Ross & Solinger, 2017). The framework also acknowledges that women need both a “safe and dignified context for these experiences” as well as access to community resources (e.g., quality health care, social support services) to achieve optimal reproductive health outcomes (Ross & Solinger, 2017). By acknowledging maternal health disparities as threats to reproductive justice, we prioritize the dismantling of racism in our path to advancing maternal health equity.

Addressing a structural risk like racism requires a structural response, such as tailored antiracist policies to improve health equity—including, for example, workforce and infrastructure investments, new models of care, and medical reparations (Malinaf et al., 2020). In addition, there is an urgent need to explore sustainable strategies that promote equitable birth outcomes among Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC).

Doulas are trained professionals who provide continuous support to birthing people before, during, and after childbirth (Doulas of North America International, 2005). Doulas aim to ensure that birthing people’s preferences are centered, that they feel respected and listened to, and that they have enough information and support to advocate for themselves throughout the birthing process. A 2017 Cochrane systematic review found an association between continuous birthing support (provided by a trained professional such as a doula) and factors linked to better birth outcomes, including a shorter duration of labor, decreased use of analgesia, lower cesarean section rates, and fewer negative feelings about childbirth (Bohren, Hofmeyr, Sakala, Fukuzawa, & Cuthbert, 2017). Among low-income and BIPOC birthing people, birth support delivered by a doula is associated with lower rates of cesarean section and low birth weight infants, as well as increased initiation of breastfeeding (Gruber, Cupito, & Dobson, 2013; Kozhimannil, Hardeman, Attanasio, Blauer-Peterson, & O’Brien, 2013). The American Col-lege of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine also acknowledge that use of continuous one-to-one emotional support provided by a support per-son like a doula can improve labor and delivery outcomes (Caughey, Cahill, Guise, & Rouse, 2014; Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2017).

Despite evidence and acknowledgment by professional organizations that doula care is associated with improved birth outcomes, doula services are underutilized among low-income and BIPOC birthing people. In a national sample of 2,400 mothers, the 2011–2012 Listening to Mothers III survey showed that, compared with privately insured respondents, Medicaid-insured respondents were nearly twice as likely to have “never heard of doulas” as an option for pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period (Declercq, Sakala, Corry, Applebaum, & Herrlich, 2013). However, despite this lack of awareness, Medicaid enrollees still had a significantly greater desire to access doula services in the future compared with those with private insurance (Declercq et al., 2013; Strauss, Sakala, & Corry, 2016). Similarly, compared with White respondents, Black and Hispanic respondents also had a significantly greater desire to access doula services in the future (Declercq et al., 2013; Strauss et al., 2016). Despite this interest, cost is also a significant barrier to doula care access; most public insurance programs (including state Medicaid programs) do not provide coverage for doula care. Similarly, commercial insurers typically only reimburse for doula services on a case-by-case basis (Doulas and Health Insurance, 2020). As a result, most people pay out-of-pocket for doula care, which can range from $300 to $1,800 (Kozhimannil et al., 2013). These costs can be a significant barrier to doula access, especially for low-income people, who are also disproportionately BIPOC.

State-level policies offer a robust structural mechanism to improve access to doula care. For example, expanding Medicaid coverage or reimbursement of doula services could significantly improve access to doula care, as an average of 43% of pregnancies in the United States are covered by Medicaid, with wide variation among states (e.g., 20% in Vermont vs. 71% in New Mexico) (Howell et al., 2018; Kaiser Family Foundation, n.d.; Kozhimannil et al., 2013; Strauss et al., 2016). Because BIPOC communities are also disproportionately served by Medicaid (Kaiser Family Foundation, n.d.), expansion of doula coverage may also help to improve use. Accordingly, legislators have proposed several policies that broadly aim to improve doula access through expanded Medicaid coverage. Although access to care is an important determinant of health (Guth, Artiga, & Pham, 2020), it is a downstream factor from fundamental and structural causes of racial health inequities.

One way to identify and challenge the fundamental or root cause of racial inequities in health is through the application of a public health critical race praxis (PHCRP). A PHCRP is a methodologic framework used to examine racial disparities in health outcomes when the goal is advancing racial health equity. A PHCRP allows the application of critical race theory—a theory that recognizes the historical legacy of White supremacy and identifies racism as a fundamental cause of inequities among historically marginalized populations—to health-related research questions while still maintaining public health standards for methodological rigor (Ford & Airhihenbuwa, 2010). There are several principles in the PHCRP, but we identify three as being most relevant to the aims of this study, because they also have their roots in Black feminist and reproductive justice theoretical models: 1) intersectionality, which acknowledges the overlapping forms of discrimination that concurrently oppress individuals; 2) structural determinism, which proposes that system- or institutional-level factors are key drivers of health inequities; and 3) voice, which centers the experiences of marginalized populations in the construction of knowledge and intervention planning (Bridges, 2011; Evans-Winters & Esposito, 2010; Hill Collins, 2000; hooks, 2014; Ross & Solinger, 2017).

Through a PHCRP lens, we recognize that, for policies that support doula care to aid in the amelioration of racial disparities in birth outcomes, there should be legislative emphasis on doula care models that explicitly center racial health equity—that every person, regardless of their racial categorization in society, have a fair and just opportunity to achieve their highest level of health—and acknowledge and address broader social and structural determinants of health inequities through an antiracist lens (Crear-Perry et al., 2021). Social determinants of health inequities refer to the conditions where people live, work, and age and include factors such as neighborhood environment, housing stability, and food security. Structural determinants of health inequities refer to upstream historical and political factors that arrange the distribution of power and shape who can access and participate in health-promoting endeavors (Crear-Perry et al., 2021). Antiracist policies that address the social and structural determinants of health inequities and center on the experiences and needs of BIPOC communities can improve racial health equity (Delaney, Essien, & Navathe, 2021). For example, Medicaid plays an important role in access to preventive care during and beyond pregnancy and disproportionately serves Black birthing people (Kaiser Family Foundation, n.d.). Enhancing postpartum access to care through expanded Medicaid eligibility and coverage beyond 60 days postpartum led to increased access to care and decreases in Black-White disparities in maternal and infant health (Bhatt & Beck-Sagué, 2018; Eliason, 2020; Gordon, Sommers, Wilson, & Trivedi, 2020).

Related to the doula workforce and maternal health equity, an antiracist policy agenda would support a diverse doula workforce—ensuring equitable pathways for workforce entry and retention—and must similarly center the experiences of doulas with intersecting marginalized identities (e.g., Black women doulas) in the development of policies that advance racial health equity in maternal health outcomes. However, to our knowledge, no study has evaluated the extent to which state doula-related legislation is poised to explicitly address these and other factors related to racial health equity.

Accordingly, the objectives of this study are to 1) evaluate state doula-related legislative trends between 2015 and 2020; 2) identify criteria for racial health equity promoting doula legislation; and 3) use these criteria to assess the extent to which doula-related legislation addresses racial health equity.

Methods

Study Design and Data

We initiated a landscape analysis—defined as a “detailed assessment that uses primary and/or secondary data to describe a problem and the policies and interventions already in place to address this problem” (Spring, 2017)—of publicly available legislative bills. We used LegiScan, a nonpartisan legislative tracking and reporting service, to identify relevant legislation as well as reports from maternal/infant health and doula advocacy websites (ASTHO Staff, 2018; Bringing People to the Process, 2000; Congress, 2019; Doula Laws and Government Regulations, n.d.; Federal Legislation, n.d.). Our search included all bills with the word “doula” in the title or body of the legislation. We considered all legislation that was introduced or passed between 2015 and 2020. We searched for state-level doula legislation in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Federal legislation was excluded. This study does not capture doula-related programs proposed by agencies other than state legislatures.

This study did not constitute human subjects research, because the data were publicly available and pertained only to legislation and policy.

Measurement

We identified nine criteria to assess the racial health equity content of each bill through a collaborative process that involved review of a doula advocacy report (Bey, Brill, Porchia-Albert, Gradilla, & Strauss, 2019) and consultation with community-based doulas. The Advancing Birth Justice Report written by Ancient Song Doula Services, Village Birth International, and Every Mother Counts lays out seven recommendations and three subrecommendations for effective and sustainable implementation of health equity-focused doula programs. The 10 recommendations are grounded in reproductive justice and human rights principles (Bey et al., 2019). The lead author of the present analysis consulted with two Baltimore-based community doulas to review, consolidate, and adapt these recommendations to allow assessment of the extent to which each was incorporated into each piece of legislation.

Our final nine racial health equity criteria are as follows.

Reimbursement to provide a living wage: The bill has a plan for reimbursement through Medicaid (or Medicaid and commercial insurance) and specifically addresses reimbursement rates to ensure that doulas can earn a “living wage,” or a wage rate based on the cost of living in the state that is sufficient to meet basic needs, and/or a rate decided upon with input from doulas.

Collaboration and engagement with community-based doulas: The bill creates a requirement for legislative collaboration with doulas. Doulas should help inform decision-making around doula-related policies and/or general maternal/infant health-related policies.

Training and certification requirements: The bill creates a requirement for training and certification of doulas (note: training and certification must not create an additional financial burden; see #5).

Training and certification with explicit racial health disparities and a health equity focus: The bill addresses the need for an explicit health disparities prioritization in the content of doula training or certification. Key content areas for racial health disparities and a health equity focus include implicit bias, social justice, antiracism, reproductive justice, or cultural competence training.

Funding to support training and certification: The bill addresses funding for doula training and/or certification, so this cost is not taken on by doulas.

Recognition of doulas’ role: The bill includes a plan to recognize and publicly acknowledge doula work and impacts on maternal–infant health (examples include the creation of a doula awareness day, creation of standard registries, and designation as a health care provider through the issuance of national provider identification numbers).

Diversity in the doula workforce: The bill includes a plan to ensure that the diversity of the community is reflected in the diversity of the doula workforce.

Creation of pilot programs: The bill creates new programs designed to ensure adequate training, certification, and mentorship for doulas who will serve communities of color and low-income birthing people.

Development of explicit processes to track and evaluate impact: The bill includes an evaluation of the impact of doulas on maternal and infant outcomes.

Analysis

For each piece of legislation, we noted which state the bill was proposed in, categorized each bill by census region, and gathered additional contextual information on maternal and infant health access and outcomes, including the state’s percentage of Medicaid births (data source: 2019 Kaiser Foundation Family Medicaid Budget Survey) and its maternal and infant mortality rate per 100,000 live births (data source: CDC WONDER Database Mortality Files, 2013–2017, and CDC WONDER Database Mortality Files, 2017, respectively). We also calculated the median and interquartile range for the Medicaid-insured birth and maternal mortality rates (and gave the source for that data) and categorized states as having a high proportion of Medicaid-covered births if the presentation of medicated births was greater than the median percentage of Medicaid births across all states (i.e., >45%).

For each piece of legislation, we also noted when the bill was proposed and the status of the bill (i.e., whether it was passed or tabled). We then reviewed its content, primary objective, and scope.

Three of the authors (S.M.O., J.K., and D.G.B.) used an iterative coding method to analyze each bill’s content. After reading and analyzing the language, we used the racial equity criteria to categorize each bill’s primary focus.

Given the important role of Medicaid in financing childbirth, we conducted an in-depth equity analysis of bills with a primary focus on Medicaid reimbursement, as well as bills that had passed into law. For the equity analysis, we created a codebook with the nine prespecified equity criteria and evaluated the extent to which the bill addressed these criteria. Throughout the process, we also updated the codebook with specific examples found within the text of bills. To ensure consistency, three of the authors (S.M.O., J.K., and D.G.B.) individually extracted and analyzed the data, then cross-checked their results and related designations, following standards for iterative qualitative coding. This method ensured systematic classification. All in-consistencies were reconciled by all three coders.

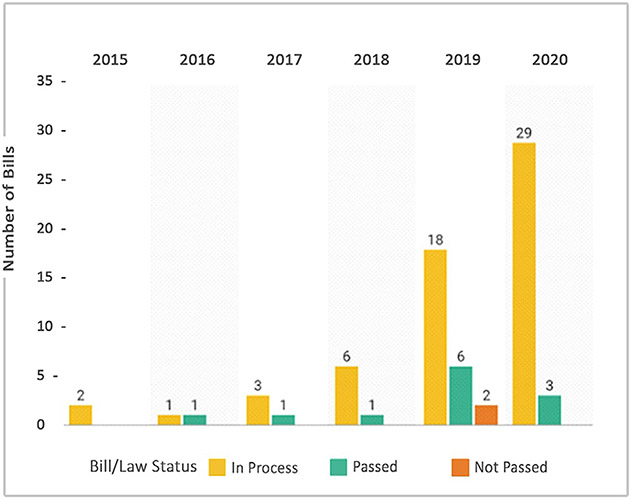

Results

We identified 73 bills in 24 states and the District of Columbia that were proposed between 2015 and 2020 and met our inclusion criteria (Table 1). The number of bills increased over time, from 15 bills introduced before 2019 to 58 bills introduced in 2019–2020 (representing a 268% increase in the number of doula bills introduced between 2015 and 2020). The vast majority (79.5%) were introduced in 2019 or later (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Doula-Related Bills and Status of Bills by State, 2015–2020

| State | % Medicaid Births* |

Maternal Mortality per 100,000 Live Births† |

Infant Mortality per 10,000 Live Births† |

Year First Bill Introduced‡ |

Number of Bills and Bill Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Passed | Not Passed | In Process | |||||

| Arizona | 52 | 27.3 | 5.7 | 2020 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| California | 51 | 17.6 | 4.2 | 2020 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Connecticut | 44 | 19.0 | 4.5 | 2019 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| District of Columbia | 36 | 35.6 | 7.7 | 2019 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Iowa | 37 | 26.5 | 5.3 | 2020 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Illinois | 44 | 21.4 | 6.1 | 2018 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Indiana | 41 | 50.2 | 7.3 | 2019 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Kentucky | 51 | 32.4 | 6.5 | 2020 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Louisiana | 65 | 72.0 | 7.1 | 2018 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Massachusetts | 35 | 13.7 | 3.7 | 2019 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Maryland | 44 | 25.0 | 6.4 | 2019 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Michigan | 46 | 27.6 | 6.8 | 2018 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Minnesota | 43 | 17.3 | 4.8 | 2015 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Nebraska | 31 | 22.7 | 5.6 | 2020 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| New Jersey | 39 | 26.4 | 4.5 | 2016 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| New York | 43 | 25.5 | 4.6 | 2018 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Oregon | 50 | 19.5 | 5.4 | 2017 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pennsylvania | 34 | 26.1 | 6.1 | 2019 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Rhode Island | 49 | 19.0 | 6.2 | 2019 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Tennessee | 50 | 35.8 | 7.4 | 2020 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Texas | 53 | 39.2 | 5.9 | 2020 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Virginia | 37 | 29.5 | 5.9 | 2020 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Vermont | 20 | 26.6 | 4.8 | 2016 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Washington | 49 | 19.7 | 3.9 | 2020 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Wisconsin | 42 | 19.9 | 6.4 | 2019 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Infant mortality per 10,000 live births were obtained from the CDC WONDER Database Mortality Files, 2017.

Percentages of births covered by Medicaid were obtained from the 2019 Kaiser Foundation Family Medicaid Budget Survey. Data are reported from the most recent 12-month period for which data were available.

Maternal mortality per 100,000 live births figures were obtained from the CDC WONDER Database Mortality Files, 2013–2017.

For states with multiple bills, we report information for the earliest doula-related bill that was introduced.

Figure 1.

Number of doula-related bills, 2015–2020.

States in every U.S. census region introduced bills: seven states in the Northeast (39.7% of all bills), seven states in the Midwest (34.2% of all bills), seven states in the South (17.9% of all bills), and four states in the West (8.2% of all bills).

States that had a bill included in our review had a median Medicaid-insured birth rate of 44% (interquartile range, 37%–50%) and maternal mortality rate of 26.1 deaths per 100,000 live births (interquartile range, 19.7–29.5) in 2018 (Table 1). Among the 24 states with doula-related legislation, 18 states (72%) had bills in process but had not yet passed a doula-related bill. Six states (24%) had passed at least one bill, and one state (4%) had failed to pass any doula-related bill (Table 1).

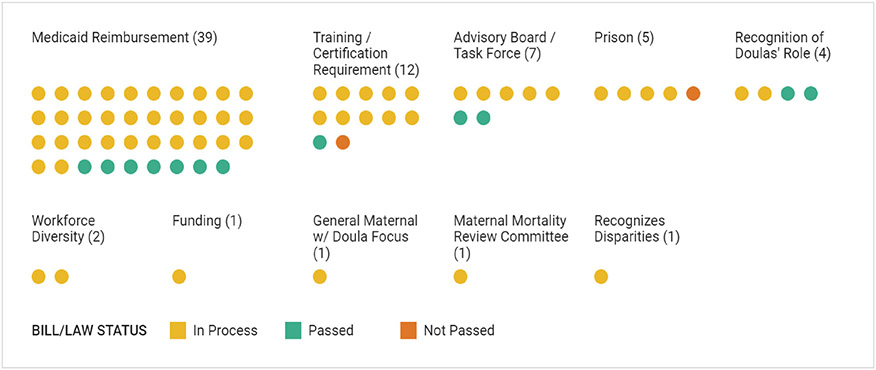

We assigned the 73 eligible bills to 10 mutually exclusive content categories, as follows: 1) Medicaid reimbursement for doulas (39 bills [53.4%]), 2) training and certification requirement for practicing doulas (12 bills [16.4%]), 3) creating an advisory board or task force for doula care (7 bills [9.6%]), 4) recognition of doulas’ role (4 bills [5.5%]), 5) doula workforce diversity (2 bills [2.7%]), 6) the role of doulas in prisons (5 bills [6.9%]), 7) recognizing disparities (1 bill [1.4%]), 8) establishing a Maternal Mortality Review Committee (1 bill [1.4%]), 9) funding to support doula training (1 bill [1.4%]), and 10) a general maternal care bill with a doula focus (1 bill [1.4%]) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Primary doula-related state bill categories and bill status, 2015–2020 (n = 73 bills).

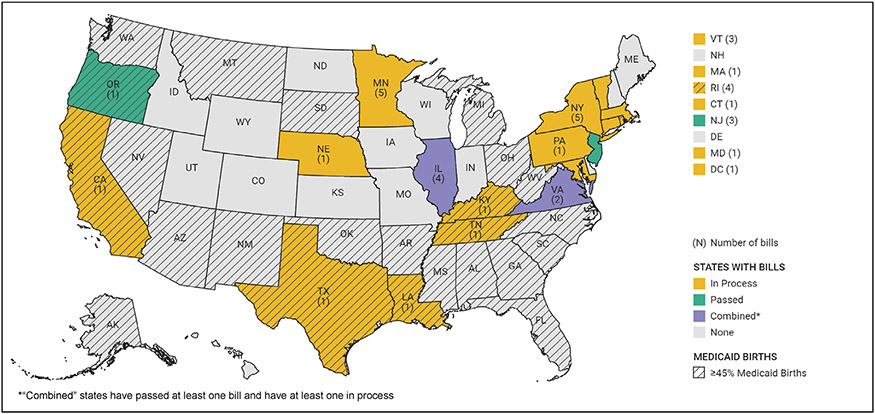

Medicaid Legislation

We further analyzed the 39 bills from 21 states focused on Medicaid reimbursement for doula care (Figure 3). One-third (33.3%) of these 21 states introduced multiple bills to be considered for legislation (the introduction of these bills was conditional on introducing a bill for Medicaid reimbursement of doula services). Only six states that introduced this type of doula legislation (28.6%) had a high share of births covered by Medicaid (defined as ≥45%). Although not every bill explicitly laid out reimbursement rates, when rates were discussed, there was significant variation in the level of reimbursement for doulas, with payment per visit ranging from $47 to $150. Sixteen states (76.2%) had introduced, but not yet voted on, Medicaid reimbursement legislation at the time of our analysis (July 2020). Three states (14.2%) had passed bills ensuring Medicaid coverage of doula services. Additionally, two states (9.6%) had at least one bill that had passed, with additional bills in process.

Figure 3.

High Medicaid coverage of births by state, and states with Medicaid reimbursement bills, 2015–2020. States with “high” Medicaid coverage have more than 45% of births (the median for all states) covered by Medicaid.

In supplemental analyses, we explored the extent to which these Medicaid reimbursement bills (many of which are still in process) focus on racial health equity. We found that the highest number of racial health equity categories addressed by a given state was nine out of nine and six out of nine in California and Minnesota, respectively. California’s bills have not yet passed, but have addressed all categories. Minnesota’s doula bills addressed all categories, except training/certification with an equity focus, reimbursement with plans to provide a living wage based on the cost of living or input from doulas, and recognition of doulas’ role. Because Minnesota had passed doula legislation before 2015, it is possible that the remaining categories were addressed in earlier bills not included in our analysis (Supplemental Table 1).

Passed Legislation

In total, 12 bills in 7 states passed through state legislatures to be signed into law. These bills addressed six dimensions of our equity evaluation criteria: 1) collaboration and engagement with community-based doulas, 2) a training or certification requirement, 3) focus on recognition of doulas’ role, 4) diversity in the workforce, 5) supporting best practices through a pilot design, and 6) measuring and reporting metrics. Among these bills, seven (58.3%) contained measures for Medicaid reimbursement for doula services, but none explicitly provided a living wage based on the cost of living or input from doulas. Further, none of the bills passed had an equity focus within the training and certification requirement, and no bills included funding to support training. Nearly one-half of the bills (41.7%) did not address any of our evaluation criteria with respect to equity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Variation in Equity Emphasis Among Bills That Passed

| State | Bill Category | Reimbursement with Plans to Provide Living Wage Based on Con or Living or with Input from |

Doulas Collaboration Engagement with Community-Based Doulas |

Training Certification Requirement |

Training Certification with Equity Focus |

Funding to Support Training |

Doula Awareness |

Diversity in Workforce |

Support Best Practices Through Pilot Design |

Measuring Reporting Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illinois | Medicaid reimbursement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Advisory board/task force |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Indiana | Medicaid reimbursement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Doula awareness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Louisiana | Advisory board/task force |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| New Jersey | Medicaid reimbursement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| New York | Doula awareness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Oregon | Medicaid reimbursement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Virginia | Medicaid reimbursement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Training certification |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total | 0 (0.0) | 3 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (16.7) | |

Advisory board created to study appropriate reimbursement.

Reimbursement rate proposed, but no mention of how rate was established.

Discussion

This analysis of doula-related legislation showed that there was a substantial increase in the number and diversity of proposed state bills related to doula care from 2015 to 2020. Proposed legislation pertaining to doulas increased nearly threefold over 5 years, with the largest gains occurring in 2019. A careful review of the content of the legislation also revealed that policies varied widely in their content and scope. Most (53.4%) of the proposed bills were related to Medicaid coverage of doula services, and several states introduced these Medicaid-related proposals together with other innovations aimed at bolstering maternal and infant health outcomes and often reducing racial disparities. Despite this large increase, only 16.4% of the proposed legislation passed into law, and none of these passed bills fulfilled all our racial health equity criteria.

To our knowledge, there are no other reports that have comprehensively evaluated the content of state doula-related legislation with a focus on racial health equity. We found that although many of the bills presented a robust evaluation and acknowledgment of the relevant health disparity issues, the content of the bills often fell short of creating a tangible policy agenda grounded in principles of racial health equity. Thus, the results of this study are particularly informative and present several opportunities for reflection and improvement.

For example, a majority (90%) of the Medicaid reimbursement bills failed to address whether reimbursement for doulas constituted a livable wage. In states such as New York, prenatal and postpartum visits (which average about 2 hours per visit) are reimbursed at $30 per visit (maximum of 8 total visits) and $360 for birth, meaning that the maximum a doula can earn for services spanning multiple months is $600. A few states (Oregon, District of Columbia, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts) established flat rates or minimum rates for doula services, but it was unclear whether this rate was calculated in a standardized manner, reflected the cost of living in the state, or was informed by discussions with practicing doulas. To sustain a diverse doula workforce, mechanisms to incentivize entry into the workforce and minimize turnover should be considered (e.g., living wages, reimbursement or coverage of training and certification costs, and reimbursement for job-related duties such as transportation for frequent in-home visits). This factor is especially important for the recruitment of low-income individuals and BIPOCs, who disproportionately serve as breadwinners in their households, into the doula workforce (Glynn, 2019).

Additionally, although some bills acknowledged the role of social determinants of health in perpetuating disparities, the connection back to the role of doulas, particularly community-based doulas, in mitigating these social determinants of health (Kozhimannil et al., 2013) was often missed. Community-based doula care offers free or low-cost labor, delivery, and postpartum doula support to communities at high risk of adverse birth outcomes and represents an innovation with significant potential to benefit low-income and BIPOC birthing people (Health Connect One, 2019; Malloy, Wubbenhorst, & Lee, 2019). In addition, community-based doulas have ties to the communities they serve and offer culturally concordant care (e.g., race/ethnicity, language, or other experience) for low-income people, who are often also BIPOC (Bey et al., 2019; Wint, Elias, Mendez, Mendez, & Gary-Webb, 2019). Importantly, Black birthing people have identified concordant care as an important mechanism for improving pregnancy-related health care experiences (McLemore et al., 2018). Another key component of the community-based doula model is a focus on helping birthing people to access resources to address the social determinants of health (e.g., accessing food pantries, housing options, and transportation to clinic appointments) (Bey et al., 2019; Gentry, Nolte, Gonzalez, & Pearson, 2010; Kozhimannil & Hardeman, 2016). Finally, the community-based doula model also emphasizes education and care delivery that is grounded in social and reproductive justice, including the explicit use of antiracist frameworks. Such frameworks name racism as a fundamental cause, hold structures and systems accountable for disparities, and work to support and help find social resources to mitigate the harm of racism and address the social and structural determinants of racial health equity. There is considerable high-quality research on the role of community health workers in improving health outcomes among vulnerable populations (Kangovi et al., 2014; Kangovi, Mitra, Turr, Huo, Grande, & Long, 2017; Kangovi, Mitra, Grande, Long, & Asch, 2020; Ruff, Sanchez, Hernandez-Cancio, Fishman, & Gomez, 2019), and there is mounting evidence that community-based doulas may play a similar role for birthing people (Gentry et al., 2010; Malloy et al., 2019).

Another commonly missed opportunity to enhance racial health equity relates to community engagement in policy planning and development. Many of the bills lacked an explicit requirement for community-level input from doulas. However, tools such as the Racial Equity Impact Assessment (Massachusetts Public Health Association, 2016; Voices for Racial Justice, 2015) and the Racial Equity Toolkit (Government Alliance on Race & Equity, 2016), which guide the equity evaluation of proposed legislation, are clear that affected community members and leaders should be engaged in the process of developing and vetting legislative proposals. Further, in discussion with our community-based doula consultants, they recommended starting with doula input—through the formation of a task force or other working group—as a first and critical step in shaping any doula-related legislation that aims to address racial health equity and create sustainable models.

Implications for Practice and/or Policy

Of course, the true measure of the impact of any of the legislative proposals will be whether states can fully carry out the mandates outlined, track outcome metrics, and, most importantly, improve health and decrease racial disparities in maternal and infant health outcomes as a result. Sustainable funding will likely be an ongoing challenge. Proposed solutions (beyond lobbying for Medicaid reimbursement) include federal, state, and organization level actions such as 1) pursuing multiple funding opportunities, with public, private, and third-party payers as possible sources; 2) advocating for the integration of doulas into delivery and payment innovation and reform models (including short-term funding solutions such as the use of Section 1115 Medicaid delivery system reform waivers); 3) advancing the policy agenda related to private and commercial insurance coverage of doula services; and 4) creating partnerships between community-based doula organizations and hospitals, federally qualified health centers, and Medicaid managed care organizations to offset costs (Health Connect One, 2017). It may also be useful to look to examples from the home visiting funding model and the community health workers model when considering pathways that would allow or increase reimbursement for doula services (Malloy et al., 2019). Finally, it is necessary to recognize that, although doulas play an important role in bridging gaps caused by structural inequities, they are not the cure for structural racism, and continued work is needed to address the historical legacy of racism that undergirds racial health inequities in the United States.

Limitations

Our study is limited primarily by data availability. This study focused on publicly available proposed state legislation that specifically mentioned doulas. It is possible that 1) additional information about Medicaid access to doula services exists elsewhere; 2) the allocation of Medicaid funds to doula services is managed by other organizations; and 3) general heterogeneity within states limited us from knowing whether states addressed other racial health equity components through initiatives or programs housed in other departments (e.g., if a state enacted a comprehensive licensure program, met collaboratively with doulas, or created a pilot program for supporting doula training). Additionally, because we only focused on a five-year period, early adopters may not have been included in our legislative sample. Another limitation of our study is that we only identified legislation that mentioned doula services and did not examine the implementation or effectiveness of legislation following its passage. This point is potentially important when considering how pitfalls such as inadequate reimbursement rates may be prohibitive to low-income doulas (who are more likely to be BIPOC) and can further exacerbate inequities. We acknowledge that proposed or in-process bills do not always get passed and that policy does not always smoothly translate into increased access—which is both a potential limitation as well an important follow-up to this study.

Conclusions

Racial inequity in birth outcomes is a pernicious and persistent reality within the United States. Access to doula care is a potential strategy for ameliorating adverse birth outcomes and decreasing racial disparities in maternal and infant health. This study’s findings show that, although the number of bills related to expanding doula access have increased, many still lack an explicit racial health equity focus. As policymakers attempt to incorporate doula care into maternal care legislation, discussions about the effective and equitable integration of doulas into clinical and community care systems are warranted. Engaging diverse doulas in the legislative process is an important starting point. Racial health equity assessments, including an evaluation of the criteria used in this analysis, should be considered as legislation is drafted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Reproductive Health Equity Alliance of Maryland, and their leadership team: Andrea Williams and Ana Rodney, two community-based doulas, and Ashley Black, Esq, an attorney who supports the community led process of drafting legislation around doula policies in Maryland. Their critical insight has helped ensure the integrity of this work.

Funding Statement:

S. Michelle Ogunwole is supported by a training grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration (Institutional National Research Service Award: T32HP10025BO). J’Mag Karbeah is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) under Award Number T32HD095134. This project also benefited from support provided by the Minnesota Population Center (P2CHD041023), which receives funding from the NICHD. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

S. Michelle Ogunwole, MD, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Her research focuses on racial disparities in maternal health outcomes related to chronic medical conditions, individual and structural level discrimination, and health policy.

J’Mag Karbeah, PhD, MPH, is an Assistant Professor of Health Policy and Management at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health and research advisor at the Center for Antiracism Research for Health Equity. Her research focuses on structural racism, health disparities, adolescent health, and perinatal health disparities.

Debra G. Bozzi, PhD, is a senior researcher at the Health Care Cost Institute. Her research works have focused on provider behavior, effects of payment reform, and health disparities.

Kelly Bower PhD, MSN, MPH, RN, is an Associate Professor, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. Her research focuses on social and structural determinants of maternal and infant health disparities.

Lisa A. Cooper MD, MPH, is a Bloomberg distinguished professor, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, and director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity and Johns Hopkins Urban Health Institute. Her research has advanced the science of patient–provider communication and racial/ethnic disparities in health outcomes.

Rachel Hardeman, PhD, MPH, is an Associate Professor, University of Minnesota School of Public Health. Her research applies the tools of population health science and health services research to elucidate a critical and complex determinant of health inequity—racism.

Katy Kozhimannil PhD, MPA, is a Professor at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health and Director of the University’s Rural Health Research Center. Her research contributes evidence for clinical and policy strategies to advance racial, gender, and geographic equity.

Footnotes

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2022.04.004.

“Birthing people” is a gender inclusive term that refers to the capacity for pregnancy and childbirth (Julian et al., 2020).

We use the term “women” here to acknowledge the unique experiences and contributions of those who identify as women. In particular, we acknowledge the legacy of reproductive injustice among Black women, a group with some of the worst maternal health outcomes in the United States, and who had to fight to be recognized as human beings and women through the era of slavery and beyond (Owens & Fett, 2019; Taylor, 2020). Black women’s historical and contemporary experiences around reproductive health were critical to the establishment of Black feminist and reproductive justice theories and frameworks—both of which demand that gendered racism be addressed when the end goal is equity (Hill Collins, 2000; Ross & Solinger, 2017).

References

- ASTHO Staff. (2018). State policy approaches to incorporating doula services into maternal care. ASTHO experts: Blog. Available: www.astho.org/StatePublicHealth/State-Policy-Approaches-to-Incorporating-Doula-Services-into-Maternal-Care/08-09-18/. Accessed: November 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, & Bassett MDT (2020). How structural racism works-racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. The New England journal of medicine, 384, 768–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belluz J (2020). The CDC released a new US maternal mortality estimate. It’s still terrible. - Vox. Available: www.vox.com/2020/1/30/21113782/pregnancy-deaths-us-maternal-mortality-rate. Accessed: October 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Chang J, Callaghan WM, & Whitehead SJ (2003). Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1991–1997. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 101, 289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besson A (2018). Doulas and Health Insurance. QuoteWizard. Available: https://quotewizard.com/health-insurance/coverage-for-doulas. Accessed: December 17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bey A, Brill A, Porchia-Albert C, Gradilla M, & Strauss N (2019). Advancing birth justice: Community-based doula models as a standard of care for ending racial disparities. Ancient Song Doula Services; Village Birth International; Every Mother Counts. Available: https://everymothercounts.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Advancing-Birth-Justice-CBD-Models-as-Std-of-Care-3-25-19.pdf. Accessed: December 17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt CB, & Beck-Sagué CM (2018). Medicaid expansion and infant mortality in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 108, 565–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohren MA, Hofmeyr GJ, Sakala C, Fukuzawa RK, & Cuthbert A (2017). Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7, CD003766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges KM (2011). Reproducing race: An ethnography of pregnancy as a site of racialization. Berkely: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bringing People to the Process. (2000). Testimony of LegiScan. Available: https://legiscan.com/legiscan. Accessed: January 4, 2020.

- Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, & Washington AE (2010). Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: Prevalence and determinants. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202, 335–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger K, Evans-Agnew R, & Johnson S. (2021). Reproductive justice and black lives: A concept analysis for public health nursing. Public Health Nursing, 39, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, & Rouse DJ (2014). Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 210, 179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths — United States, 2007–2016. Available: www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/index.html. Accessed: August 1, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Infant mortality. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers BD, Arega HA, Arabia SE, Taylor B, Barron RG, Gates B, … McLemore MR (2021). Black women’s perspectives on structural racism across the reproductive lifespan: A conceptual framework for measurement development. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 25, 402–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Obstetric Practice. (2017). Committee opinion no. 687 summary: Approaches to limit intervention during labor and birth. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 129, 403–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congress (2019). Congress.gov: Library of Congress. Available: www.congress.gov/. Accessed: August 1, 2020.

- Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Ko JY, Farr SL, Tong VT, Bruce FC, & Callaghan WM (2014). Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States: where are we now? Journal of Women’s Health, 23, 3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crear-Perry J, Correa-de-Araujo R, Lewis Johnson T, McLemore MR, Neilson E, & Wallace M (2021). Social and structural determinants of health inequities in maternal health. Journal of Women’s Health, 30, 203–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry MP, Applebaum S, & Herrlich A (2013). Listening to Mothers III: New Mothers Speak Out. New York: Childbirth Connection. Available: https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/health-care/maternity/listening-to-mothers-iii-new-mothers-speak-out-2013.pdf. Accessed: December 17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney SW, Essien UR, & Navathe A (2021). Disparate impact: How color-blind policies exacerbate Black-white health inequities. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doula Laws and Government Regulations. (2020). New beginnings doula training. Available: https://www.trainingdoulas.com/laws/. Accessed: December 17, 2020.

- Doulas of North America International. (2005). DONA International: What is a doula?. Available: www.dona.org/what-is-a-doula/. Accessed: November 14, 2020.

- Eliason EL (2020). Adoption of Medicaid expansion is associated with lower maternal mortality. Women’s Health Issues, 30, 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Winters VE, & Esposito J (2010). Other people’s daughters: Critical race feminism and black girls’ education. Educational Foundations, 24, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Legislation. March for moms. Available: https://marchformoms.org/advocacy/federal-legislation/. Accessed: December 17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ford CL, & Airhihenbuwa CO (2010). The public health critical race methodology: Praxis for anti-racism research. Social Science& Medicine, 71, 1390–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry QM, Nolte KM, Gonzalez A, & Pearson M (2010). “Going beyond the call of doula”: A grounded theory analysis of the diverse roles community-based doulas play in the lives of pregnant and parenting adolescent mothers. Journal of Perinatal Education, 19, 24–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn SJ (2019). Breadwinning mothers continue to be the U.S. norm. Available: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/breadwinning-mothers-continue-u-s-norm/#:~:text=Breadwinning%20mothers%20are%20likely%20to,racism%20in%20their%20daily%20lives. Accessed: November 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon SH, Sommers BD, Wilson IB, & Trivedi AN (2020). Effects of Medicaid expansion on postpartum coverage and outpatient utilization. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 39, 77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government Alliance on Race & Equity. (2016). Racial equity toolkit: An opportunity to operationalize equity. Available: www.racialequityalliance.org. Accessed: November 1, 2020.

- Gruber KJ, Cupito SH, & Dobson CF (2013). Impact of doulas on healthy birth outcomes. Journal of Perinatal Education, 22, 49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guth M, Artiga S, & Pham O (2020). Effects of the ACA Medicaid expansion on racial disparities in health and health care. Available: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/effects-of-the-aca-medicaid-expansion-on-racial-disparities-in-health-and-health-care/. Accessed: November 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Health Connect One. (2017). Sustainable funding for doula programs – A study. Available: Healthconnectone.org. Accessed: October 12, 2020.

- Health Connect One. (2019). HealthConnect one issue brief: creating policy for equitable doula access. Available: https://www.healthconnectone.org/new-hc-one-issue-brief-creating-policy-for-equitable-doula-access/. Accessed: October 2, 2020.

- Hill Collins P (2000). Black feminist thought: knowledge, consciousness and the politics of empowerment (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- hooks b. (2014). Feminist theory: From margin to center (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Howell EA (2018). Reducing disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 61, 387–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell EA, Brown H, Brumley J, Bryant AS, Caughey AB, Cornell AM, … Grobman WA (2018). Reduction of peripartum racial and ethnic disparities: A conceptual framework and maternal safety consensus bundle. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 47, 275–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyert DL, Uddin SFG, & Miniño AM (2020). Evaluation of the pregnancy status checkbox on the identification of maternal deaths. National Vital Statistics Reports, 69, 1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian Z, Robles D, Whetstone S, Perritt JB, Jackson AV, Hardeman RR, & Scott KA (2020). Community-informed models of perinatal and reproductive health services provision: A justice-centered paradigm toward equity among Black birthing communities. Seminars in Perinatology, 44, 15126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation (no date). Births financed by Medicaid, 2020. Available: www.kff.org/medicaid/stateindicator/births-financed-bymedicaid/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22ac%22%7D. Accessed: August 1, 2020.

- Kangovi S, Grande D, Carter T, Barg FK, Rogers M, Glanz K, … Long JA (2014). The use of participatory action research to design a patient-centered community health worker care transitions intervention. Healthcare (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2, 136–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangovi S, Mitra N, Grande D, Long JA, & Asch DA (2020). Evidence-based community health worker program addresses unmet social needs and generates positive return on investment. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 39, 207–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangovi S, Mitra N, Turr L, Huo H, Grande D, & Long JA (2017). A randomized controlled trial of a community health worker intervention in a population of patients with multiple chronic diseases: Study design and protocol HHS Public Access. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 53, 115–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil KB, & Hardeman RR (2016). Coverage for doula services: How state Medicaid programs can address concerns about maternity care costs and quality. Birth, 43, 97–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil KB, Hardeman RR, Attanasio LB, Blauer-Peterson C, & O’Brien M (2013). Doula care, birth outcomes, and costs among Medicaid beneficiaries. American Journal of Public Health, 103, e113–e121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard SA, Main EK, Scott KA, Profit J, & Carmichael SL (2019). Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity prevalence and trends. Annals of epidemiology, 33, 30–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malloy C, Wubbenhorst MC, & Lee TS (2019). The perinatal revolution. Issues in Law and Medicine, 34, 15–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Public Health Association. (2016). Health Equity Policy Framework. Available: https://mapublichealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/mpha-health-equity-policy-framework-approved-11-16-2016.pdf. Accessed: September 1, 2020.

- McLemore MR, Altman MR, Cooper N, Williams S, Rand L, & Franck L (2018). Health care experiences of pregnant, birthing and postnatal women of color at risk for preterm birth. Social Science & Medicine, 201, 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer LC, Vinikoor LC, Laraia BA, Kaufman JS, Eyster J, Holzman C, … O’Campo P (2008). Socioeconomic domains and associations with preterm birth. Social Science & Medicine, 67, 1247–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DC, & Fett SM (2019). Black maternal and infant health: Historical legacies of slavery. American Journal of Public Health, 109, 1342–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross KM, Guardino C, Dunkel Schetter C, & Hobel CJ (2020). Interactions between race/ethnicity, poverty status, and pregnancy cardio-metabolic diseases in prediction of postpartum cardio-metabolic health. Ethnicity & Health, 25, 1145–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L, & Solinger R (2017). Reproductive justice. Berkley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruff E, Sanchez D, Hernandez-Cancio S, Fishman E, & Gomez R (2019). Advancing health equity through community health workers and peer providers: Mounting Evidence and policy recommendations. Available: www.familiesusa.org/resources/advancing-health-equity-through-community-health-workers-and-peer-providers-mounting-evidence-and-policy-recommendations/. Accessed: December 17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf JM, Liem SMS, Willem B, Mol J, Abu-Hanna A, & Ravelli ACJ (2013). Ethnic and racial disparities in the risk of preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Perinatology, 30, 433–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KA, Britton L, & McLemore MR (2019). The ethics of perinatal care for black women: Dismantling the structural racism in “mother blame” narratives. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing, 33, 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva LM, Coolman M, Steegers EAP, Jaddoe VWV, Moll HA, Hofman A, … Raat H(2008). Low socioeconomic status is a risk factor for preeclampsia: The Generation R Study. Journal of Hypertension, 26, 1200–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring (2017). In Understanding anemia guidance for conducting a landscape analysis, 88. Available: www.spring-nutrition.org. Accessed: September 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss N, Sakala C, & Corry MP (2016). Overdue: Medicaid and private insurance coverage of doula care to strengthen maternal and infant health. Journal of Perinatal Education, 25, 145–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JK (2020). Structural racism and maternal health among black women. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics, 48, 506–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). Infant mortality and African Americans. Rockville, MD: Office of Minority Health Resource Center. [Google Scholar]

- Voices for Racial Justice (2015). Racial equity impact assessment. Minneapolis, MN: Voices for Racial Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Wint K, Elias TI, Mendez G, Mendez DD, & Gary-Webb TL (2019). Experiences of community doulas working with low-income, African American mothers. Health Equity, 3, 109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.