Abstract

BACKGROUND

There has been a fundamental shift in the recruitment of medical students and trainees into residency and fellowship programs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Historically, websites for medical trainees demonstrate a lack of explicit focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion. Diversity has positive associations with improving healthcare team performance, patient care, and even financial goals. A lack of diversity may negatively affect patient care. Directed recruitment of underrepresented in medicine applicants has proven successful to increase diversity within training programs. Department websites had a more prominent role in virtual recruitment since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Features on these websites may be used to attract underrepresented in medicine applicants and increase diversity in a field.

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to analyze maternal-fetal medicine fellowship websites for the presence of diversity elements important to those people who are underrepresented in medicine.

STUDY DESIGN

Fellowship websites were accessed in the summer of 2021. They were analyzed for the presence of 12 website elements that demonstrate commitment to diversity, including (1) nondiscrimination statement, (2) diversity and inclusion message, (3) diversity-specific language, (4) resources for trainees, (5) community demographics, (6) personalized biographies of faculty, (7) personalized biographies of fellows, (8) individual photographs of faculty, (9) individual photographs of fellows, (10) photos or biographies of alumni, (11) diversity publications, and (12) department statistics. Program size, region, and location were collected. Self-reported underrepresented in medicine data on residency programs was extracted from the National Graduate Medical Education Survey from 2019. Programs were dichotomized into ≥6 diversity elements. Nonparametric, chi-square, and Fisher exact tests were used for the analysis.

RESULTS

Fellowship programs were analyzed (excluding military or fetal surgery [n=91/94]). Websites included a mean of 4.1±2.5 diversity elements. Most featured fewer than 6 elements (n=75 [82.4%]). When dichotomized to ≥6 diversity elements, larger faculty size was the only significant factor (P=.01). Most programs had fewer than 12 faculty members (n=54 [59.3%]), and only 9.3% of those programs had >6 diversity elements. In contrast, among programs with more than 12 faculty, 29.7% had ≥6 diversity elements. Faculty photos, fellow photos, and diversity publications were the most commonly featured items (92.4%, 68.1%, and 49.5%, respectively). The mean rate of underrepresented in medicine was 18.8%±11.3%, and no significant association was noted. There was a nonsignificant difference in diversity elements in the West United States with a mean of 5.3±2.2 diversity elements, compared with a mean of 3.7±2.0 diversity elements in the South United States.

CONCLUSION

Fellowship websites convey information for trainees, especially in an era of virtual recruitment. This study highlights opportunities for directed improvements of websites for features that underrepresented in medicine trainees have identified as important.

Key words: diversity, equity and inclusion, maternal-fetal medicine fellowship programs, underrepresented in medicine, virtual recruitment

AJOG Global Reports at a Glance.

Why was this study conducted?

This study aimed to characterize trends in virtual website recruitment of maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) fellows as it relates to the promotion of diversity and inclusion.

Key findings

Few diversity elements (DEs) were represented on most fellowship websites. A larger faculty size was associated with a greater virtual representation of diversity. Southern programs had fewer DEs and were not statistically significant.

What does this add to what is known?

This study further illustrates the areas for improvement in virtual diversity recruitment of MFM fellows, creating a foundation for future research to elucidate whether improved website representation of diversity yields higher rates of underrepresented in medicine in the field.

Introduction

Diversity and the recruitment of underrepresented in medicine (URIM) trainees are particularly important in the field of obstetrics and gynecology where persistent inequities in representation, compensation, academic advancement, and health outcomes exist and remain crucial to address through recognition, support, and providing equity.1 Promoting cultural competence in medicine and diversifying the medical workforce are essential to narrow healthcare disparities and improve patient outcomes.2,3 Many components of diversity include race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, socioeconomic status, and disability status. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) historically defined underrepresented minorities, including Black, indigenous, and Hispanic applicants.4 In 2003, the AAMC expanded the definition of URIM to include all those disproportionately represented in medical professions.4 The Racial Justice Scorecard was developed to evaluate representation and decrease inequities in medical training for Black, indigenous, and people of color individuals; their central tenets include police abolition, community member representation, and redistribution of education and resources.5

Historically, obstetrics and gynecology had a low rate of URIM.6 However, in 2020, 19.7% of all practicing obstetrics and gynecology residents were URIM, compared with 13.8% among all residents.6,7 This is compared with the rate of URIM within the US population, which was 33.4%.8 Although the percentage of women in obstetrics and gynecology has increased over the past 30 years, it seems that women and racial and ethnically diverse people are still underrepresented in obstetrics and gynecology subspecialties, including maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) and gynecology oncology.9 Most obstetrics and gynecology program directors note the importance of recruiting URIM applicants, but only 32% of obstetrics and gynecology program directors were able to employ specific URIM recruitment programs.3,8,10 The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) acknowledges the significant racial disparities in maternal health outcomes and has placed increased focus on diversity, cultural humility, and cultural sensitivity within the field to improve outcomes.11 In addition, profound inequities in maternal and infant outcomes based on race exist, yet funding proposals by URIMs are less likely to succeed.12 According to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies, residents are expected to demonstrate sensitivity and responsiveness to diverse patient populations (professionalism) and advocate for improvements to systems-based practice. Although MFMs reportedly have significantly higher ambiguity tolerance and cognitive engagement as a group with their patients13 than general obstetricians, the subspecialty seemed the least competitive program in recent matching analysis.14

Virtual recruitment is more important to applicants since the COVID-19 pandemic. In April 2020, the National Resident Match Program announced that interviews and recruitment should be conducted in a virtual format.15 Among psychiatry applicants who attended a virtual diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) fair, 69.7% of applicants developed a new interest in a participating program, thus demonstrating the influence of virtual representation on application rates.16 In 2020, most radiology residency programs used at least 1 social media platform for virtual recruitment, and 50% of radiology residency programs indicated that they used these platforms to promote DEI specifically.9 In 2021, a paucity of surgery residency websites (18.6%) included DEI information.17 Another study of surgery programs indicated that university affiliation yielded more diversity elements (DEs) on the program websites.18 This study aimed to analyze MFM fellowship websites for the presence of DEs important to people who are underrepresented in medicine. It is hypothesized that programs with increased website representation of diversity will have higher rates of URIM among trainees.

Materials and Methods

In 2021, a multidisciplinary and multilevel team of voluntary stakeholders was established at the University of Arizona, including academic deans, department of obstetrics and gynecology members, DEI committee members, medical students, administrators, residents, fellows, attending physicians within the University of Arizona, and practicing physicians outside the university. Stakeholders (12–15 people) had a core interest in DEI as demonstrated by URIM membership, DEI committee work, and/or DEI academic title. Stakeholders reviewed and provided feedback on 5 to 7 iterations of proposed DEs for this project based on previous studies (see below), personal experience, and DEI member discussion with at least 1 of the senior authors (C.P.V or T.A.O.). In addition, DEs were identified based on previous research into important DEI components of residency websites9,16, 17, 18, 19, 20; important elements identified by other URIM interviewees in making their final training decision, including community demographics, cost of in-person interviews, or a desire to serve the underserved21, 22, 23; and novel elements identified by DEI stakeholders (see above), such as diversity publications discovered in the preliminary review of the University of Arizona's departmental websites conducted for DEI office internal review (unpublished data).

Of note, 12 DEs were included in this study as follows: (1) a nondiscrimination statement, (2) a diversity and inclusion message, (3) diversity-specific language (including mention of one or more types of diversity on the website: racial, ethnic, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, socioeconomic status, and disability), (4) resources for trainees (including mentorship, grants, and stipends), (5) community demographics, (6) personalized biographies of faculty, (7) personalized biographies of fellows, (8) individual photographs of faculty, (9) individual photographs of fellows, (10) photographs or biographies of alumni, (11) diversity peer-reviewed publications (including both diversity of providers in the field and among patient populations), and (12) department diversity statistics. Detailed profiles had to delve deeper into an individual's background than their educational history; it had to include information on lifestyle, family, hobbies, ties to the community, etc. Weekly team meetings were held to discuss and clarify elements.

The SMFM identified 94 fellowship programs on their website.24 Of note, 3 programs were excluded as they were either fetal surgery fellowships or military fellowships. Military programs have specific requirements for their official websites and, therefore, were excluded from this analysis. The study was deemed exempt from institutional review board review. The authors extracted data from these official program websites in the summer of 2021; data were stored in Research Electronic Data Capture.25 Programs were divided into 4 regions of the United States—Northeast, South, West, and Midwest—per the US Census Bureau definition.26 Program-specific data, including faculty number, fellow number, affiliations, and locale classification per the National Center for Education Statistics definition was obtained from the SMFM website and confirmed on the official program department website.27

Demographic data for fellowship programs were unavailable, so residency data for affiliated programs were used as a surrogate marker for fellowship data. Residency URIM data were obtained from the Graduate Medical Education (GME) Survey 2019.6

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 28.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics were used for demographic variables. Programs were dichotomized into ≥6 DEs. Nonparametric, chi-square, and Fisher exact tests were used.

Results

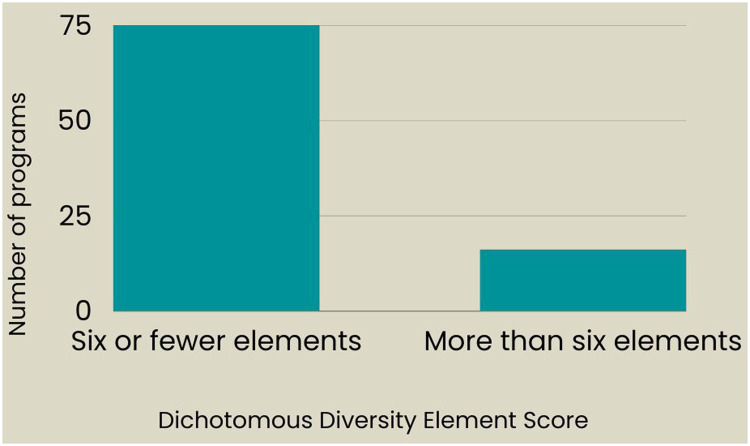

A total of 91 fellowship programs were analyzed. Figure 1 illustrates the relative prevalence of each number of the DEs. There is a skew toward fewer elements with 82.4% of all MFM programs having ≤6 elements (Figure 2). The overall average is 4.1±2.5 DEs. The most prevalent DEs were faculty photos, fellow photos, and diversity publications (92.4%, 67.4%, and 48.9%, respectively). The least frequent DEs included alumni photos or biographies, nondiscrimination statements, and department diversity statistics (10.9%, 9.8%, and 4.3%, respectively) (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Distribution of fellowship websites with number of diversity elements

Winget. Diversity elements on maternal-fetal medicine fellowship websites. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

Figure 2.

Dichotomous view of programs with ≤6 or >6 diversityelements

Most of the programs (82%) had less than half of the diversity elements.

Winget. Diversity elements on maternal-fetal medicine fellowship websites. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

Figure 3.

Frequency of each diversity element

Numbers add up to larger than 100% as websites can have more than 1 diversity element.

Winget. Diversity elements on maternal-fetal medicine fellowship websites. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

University-affiliated programs composed 81.3% of all programs. They featured an average of 4.4±2.2 DEs, and 20.3% of programs had >6 DEs. In contrast, 18.7% of programs were community based and had a mean of 3.0±2.0 DEs, and 5.9% of programs had >6 DEs. University-affiliated programs did not have a significantly different number of DEs on average (P=.16).

Larger departments, based on the total number of faculty, are associated with more featured DEs (P=.012). Of note, 37 programs (40.7%) had ≥12 faculty members and were deemed large departments. They featured an average of 5.1±2.2 DEs. Within this group, 29.7% of programs had >6 DEs, and among small programs, only 9.3% of programs had >6 DEs. In contrast, 59.3% of departments have <12 faculty and feature an average of 3.4±2.1 DEs (Table). The number of fellows within a program was not significantly associated with the number of DEs (P=.35).

Table.

Mean DEs associated with maternal-fetal medicine program factors

| Factor | Mean DEs (SD) |

|---|---|

| Overall (N=91) | 4.1 (2.5) |

| University based (n=74) | 4.3 (2.2) |

| Community or community affiliated (n=17) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Western United States (n=16) | 5.3 (2.2) |

| Southern United States (n=27) | 3.7 (2.0) |

| Northeast United States (n=28) | 3.6 (2.2) |

| Midwest United States (n=18) | 4.5 (2.4) |

| ≥12 faculty (n=54) | 5.1 (2.2) |

| <12 faculty (n=37) | 3.4 (2.1) |

DE, diversity element; SD, standard deviation.

Winget. Diversity elements on maternal-fetal medicine fellowship websites. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

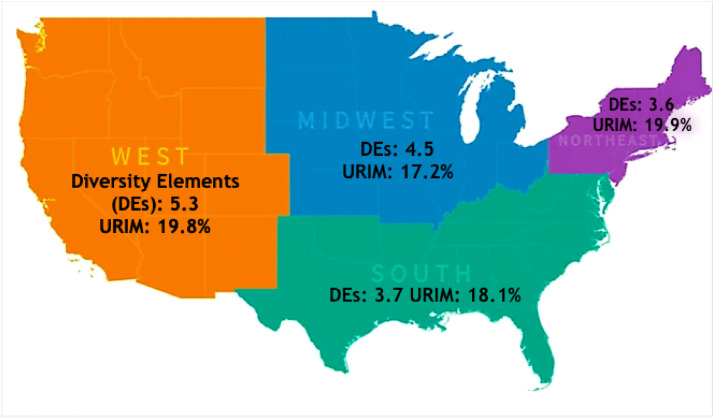

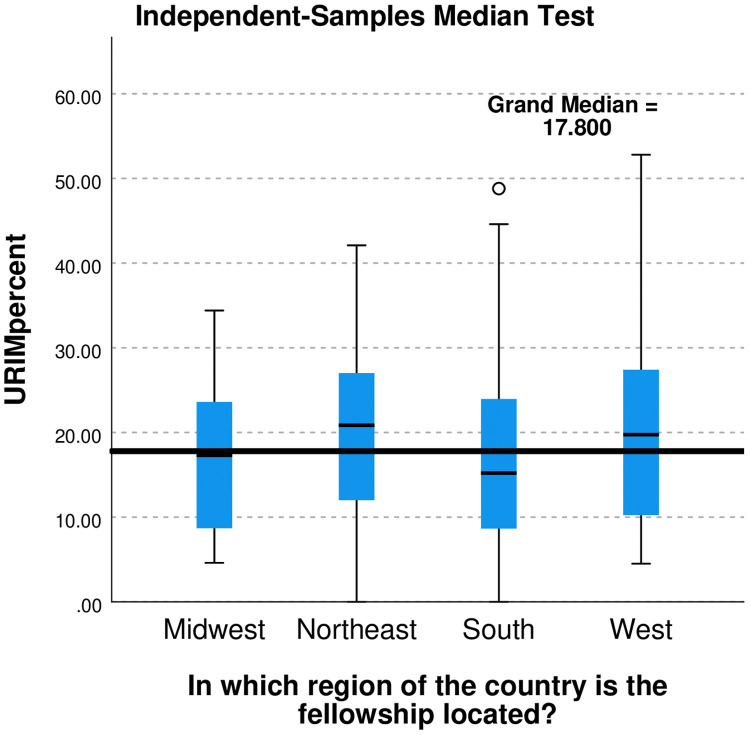

The mean rate of residency URIM associated with the 91 fellowship programs was 18.8%±11.3%. No association between the percentage of URIM and the prevalence of DEs was found (P=.34). There were nonsignificant regional differences in both rate of URIM and mean DEs. The mean percentage rates of URIM were 19.9% in the Northeast United States, 19.8% in the West United States, 18.1% in the South United States, and 17.2% in the Midwest United States (P=.82) (Figure 4, Figure 5). Program DEs were 5.31±2.2 in the West United States, 4.5±2.4 in the Midwest United States, 3.7±2.0 in the South United States, and 3.6±2.2 in the Northeast United States (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Regional map with DEs and percentage of URIM trainees

No significant difference was observed.

DE, diversity element; URIM, underrepresented in medicine.

Winget. Diversity elements on maternal-fetal medicine fellowship websites. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

Figure 5.

Box and whisker plots of the regional variations of URIM

No significant difference was found. In SPSS software, the asterisk and open circles (o) indicate extreme and suspected location of outliers in the data, respectively.

URIM, underrepresented in medicine.

Winget. Diversity elements on maternal-fetal medicine fellowship websites. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

Figure 6.

Box and whisker plots of regional variations in DEs

No significant difference was found. In SPSS software, the asterisk (*) and open circles (o) indicate extreme and suspected location of outliers in the data, respectively.

Winget. Diversity elements on maternal-fetal medicine fellowship websites. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

Comment

Principal findings

Most program websites (82%) featured fewer than half of the identified DEs. Department size was the only factor associated with the increased number of DEs. Contrary to our hypothesis, the percentage of URIM was not associated with the number of DEs.

Results

Our results are similar to those of other studies, with most training websites demonstrating a dearth of DEs.9,18, 19, 20 In addition, photographs of trainees and faculty are consistently prominent features on departmental websites.18,19 Similar to a general surgery study,18 we found no association between DEs and program size, type, and city size. Greater faculty size was associated with more DEs, which is similar to a previous orthopedic study.20

Our results vary from previously published data concerning university affiliation being positively associated with DEs.9,18,20 General surgery websites with university affiliation have a greater DEs.18 University-affiliated radiology residency social media websites more frequently had DEs.9 In contrast, this study found no association with university affiliation. Only 18.7% of MFM fellowships are community based, compared with 28.5% among general surgery residencies,17 which potentially contributed to the lack of association. No regional variation in DEs was found, which is in contrast to other medical trainee studies.9,20

Clinical implications

Although these data do not support our hypothesis, the data provide an opportunity to assess the current state of DEs for MFM fellowship websites. Explicit messaging from institutions that diversity is important is an evidenced-based intervention that can increase URIM recruitment, retention, and matriculation.28 No association was found between URIM percentage and DEs on program websites. This finding may be explained by most MFM programs (82%) lacking the desired information. URIM may have used alternative sources for DEs. For instance, social media is becoming more commonly used for trainee recruitment.6

Increased URIM in medicine has been positively associated with patient outcomes and satisfaction.2 SMFM currently has a mission to increase equity and diversity and acknowledges the importance of diverse leaders in accomplishing and sustaining this goal.29 Policies that focus on increased DEs on MFM fellowship websites might also attract candidates at all levels, such as faculty or staff, who are interested in the focused effort on inclusion.

Research implications

This project could be expanded to include social media platforms for MFM or obstetrics and gynecology, thereby analyzing multiple access points that applicants use in this era of virtual recruitment. Targeted policies by SMFM, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, or institutions to improve DEs on websites for trainees can be followed up with studies to assess if their intended increase in recruitment of URIM was successful. In addition, studies assessing the perceived effect on URIM applicants in the next recruitment cycle might help to identify if the measures are acceptable and culturally appropriate.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the multidisciplinary and comprehensive nature of the analysis of MFM fellowship websites. DEs were reviewed with URIM stakeholders to allow for the broadening of previously described components and validation of elements. Diversity publications were included as a novel DE. All included MFM fellowship program websites were accessed within a single interview season.

Limitations of our study should also be considered. We acknowledge that URIM applicants have many factors influencing their decisions about fellowship. DEs may attract applicants overall, not specifically URIM. In addition, there are multiple platforms on which applicants can obtain information on the program, including social media. We limited the analysis to official departmental websites. Moreover, data on URIM percentage within programs are based on the National GME Survey from 2019. We had demographic data only on residents, and the data were limited to race and ethnicity. Thus, although the latest available data for URIM were used, the data were 2 years old, and resident data had to be used as a surrogate marker of overall program diversity. Direct comparison of both resident and fellow data would be even more enlightening.

Conclusion

Fellowship websites convey information for trainees, especially in an era of virtual recruitment. This study highlights opportunities for directed and explicit improvements intended to increase the recruitment of the URIM workforce.

Glossary

AAMC: Association of American Medical Colleges

DE: diversity elements

DEI: diversity, equity, and inclusion

GME: graduate medical education

MFM: maternal-fetal medicine

SMFM: Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine

URIM: underrepresented in medicine

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Department of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at the University of Arizona for assisting in the development of a list of diversity elements for the assessment of training program websites.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

This study was presented as a poster (abstract number 126) at the 42nd annual pregnancy meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine that was held virtually in February 3, 2022.

Patient consent is not required because no personal information or detail is included.

Cite this article as: Winget VL, Mcwhirter AM, Delgado ML, et al. Diversity elements on maternal-fetal medicine fellowship websites: opportunity for improvement in recruitment and representation. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023;XX:x.ex–x.ex.

References

- 1.Parchem JG, Townsel CD, Wernimont SA, Afshar Y. More than grit: growing and sustaining physician-scientists in obstetrics and gynecology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomez LE, Bernet P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talbott JMV, Wasson MN. Sex and racial/ethnic diversity in accredited obstetrics and gynecology specialty and subspecialty training in the United States. J Surg Educ. 2022;79:818–827. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association of American Medical Colleges. Underrepresented in medicine definition. Available at:https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/equity-diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine. Accessed August 1, 2021.

- 5.White Coats For Black Lives. Racial justice report card 2020-2021. Available at: https://whitecoats4blacklives.org/rjrc/. Accessed June 18, 2021.

- 6.Association of American Medical Colleges. Table B5. Number of active MD residents, by race/ethnicity (alone or in combination) and GME specialty. Accessed June 15, 2021.

- 7.2020. Available at:https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/data/report-residents/2020/table-b5-md-residents-race-ethnicity-and-specialty. Accessed XXX.

- 8.Mendiola M, Modest AM, Huang GC. Striving for diversity: national survey of OB-GYN program directors reporting residency recruitment strategies for underrepresented minorities. J Surg Educ. 2021;78:1476–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson JL, Bhatia N, West DL, Safdar NM. Leveraging social media and web presence to discuss and promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in radiology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2022;19:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2021.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diversity in medicine: facts and figures, 2019. Figure 20 Percentage of physicians by sex and race/ethnicity 2018. Accessed at:https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/figure-20-percentage-physicians-sex-and-race/ethnicity-2018. Accessed on August 2, 2021.

- 11.Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine. Racial disparities in health outcomes: an official position statement of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. 2017. Available at:https://s3.amazonaws.com/cdn.smfm.org/media/1108/Racial_Disparities_-_Jan_2017.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- 12.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Wheeler SM, Bryant AS, Bonney EA, Howell EA. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Special Statement: race in maternal-fetal medicine research- Dispelling myths and taking an accurate, antiracist approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226:B13–B22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yee LM, Grobman WA. Obstetrician cognitive and affective skills in a diverse academic population. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:138. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0659-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pyskir N, Sitler C, Miller C, Yheulon C, Levy G. Analyzing trends in obstetrics and gynecology fellowship training over the last decade using the normalized competitive index. AJOG Glob Rep. 2022;2 doi: 10.1016/j.xagr.2022.100107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The match: conduct virtual interviews for the 2021–22 recruitment cycle. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-05/covid19_Final_Recommendations_05112020.pdf. National Resident Matching Program. Accessed August 2, 2021.

- 16.Ojo E, Hairston D. Recruiting underrepresented minority students into psychiatry residency: a virtual diversity initiative. Acad Psychiatry. 2021;45:440–444. doi: 10.1007/s40596-021-01447-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mortman R, Frazier HA, 2nd, Haywood YC. Diversity and inclusion on general surgery, integrated thoracic surgery, and integrated vascular surgery residency program websites. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13:345–348. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-20-00905.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Driesen AMDS, Romero Arenas MA, Arora TK, et al. Do general surgery residency program websites feature diversity? J Surg Educ. 2020;77:e110–e115. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanchez AN, Martinez CI, Lara AM, Washington M, Escalon MX, Verduzco-Gutierrez M. Evaluation of diversity and inclusion presence among US physical medicine and rehabilitation residency program websites. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;100:1196–1201. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mortman RJ, Gu A, Berger P, et al. Do orthopedic surgery residency program Web sites address diversity and inclusion? HSS J. 2022;18:235–239. doi: 10.1177/15563316211037661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weygandt PL, Smylie L, Ordonez E, Jordan J, Chung AS. Factors influencing emergency medicine residency choice: diversity, community, and recruitment red flags. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5:e10638. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heisler CA, Botros-Brey S, Wang H, et al. Money matters: anticipated expense of in-person obstetrics and gynecology fellowship interviews has greater impact for underrepresented in medicine and women applicants. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle) 2022;3:686–691. doi: 10.1089/whr.2021.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salhi RA, Dupati A, Burkhardt JC. Interest in serving the underserved: role of race, gender, and medical specialty plans. Health Equity. 2022;6:933–941. doi: 10.1089/heq.2022.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SMFM Fellowship. Programs. Society of maternal fetal medicine; 2021. Available at: https://www.smfm.org/fellowships. Accessed May 12, 2021.

- 25.Patridge EF, Bardyn TP. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106:142–144. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Census regions and divisions of the United States. 2021. Available at:https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/mapsdata/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2021.

- 27.National Center for Education Statistics. Locale classifications. Available at:https://nces.ed.gov/programs/edge/Geographic/LocaleBoundaries. Accessed June 2, 2021.

- 28.Mabeza RM, Christophers B, Ederaine SA, Glenn EJ, Benton-Slocum ZP, Marcelin JR. Interventions associated with racial and ethnic diversity in US graduate medical education: a scoping review. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.49335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Diversity and inclusion in leadership: an official position statement of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. 2017. Available at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/cdn.smfm.org/media/1107/Leadership_-_January_2017.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2021.