Abstract

Background

COVID-19 pandemic hit the entire world with severe health and economic consequences. Although the infection primarily affected the respiratory system, it was soon recognized that COVID-19 has a multi-systemic component with various manifestations including cutaneous involvement.

Objective

The main objective of this study is to assess the incidence and patterns of cutaneous manifestations among moderate-to-severe COVID-19 patients who required hospitalization and whether there was a prognostic indication for cutaneous involvement and the outcome in terms of recovery or death.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional observational study that included inpatients who were diagnosed with a moderate or severe COVID-19 infection. The demographic and clinical data of patients were assessed including age, sex, smoking, and comorbidities. All patients were examined clinically for the presence of skin manifestations. Patients were followed for the outcome of COVID-19 infection.

Results

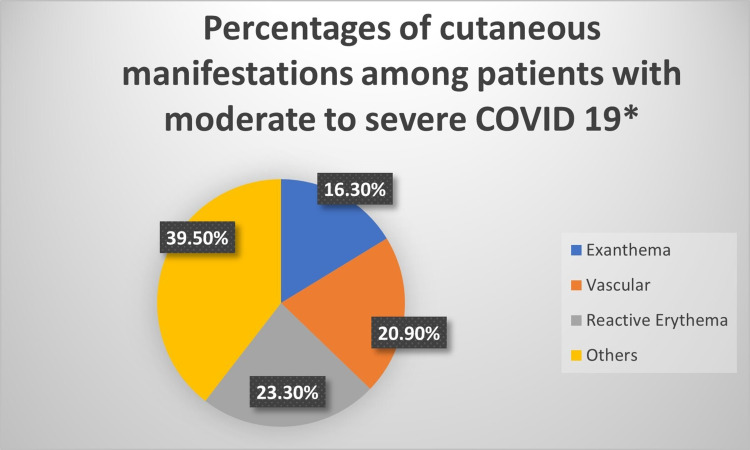

A total of 821 patients (356 females and 465 males) aged 4–95 years were included. More than half of patients (54.6%) aged >60 years. A total of 678 patients (82.6%) had at least one comorbid condition, mostly hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Sixty-two patients (7.55%) developed rashes; 5.24% cutaneous and 2.31% oral. The rashes were then grouped into five major types: group A, Exanthema: morbilliform, papulovesicular, varicella-like. Group B, Vascular: Chilblain-like lesions, purpuric/petechial, livedoid lesions. Group C, Reactive erythemas: Urticaria, Erythema multiforme. Group D, other skin rashes including flare-up of pre-existing disease, and O for oral involvement. Most patients (70%) developed rash after admission. The most frequent skin rashes were reactive erythema (23.3%), followed by vascular (20.9%), exanthema (16.3%), and other rashes with flare-ups of pre-existing diseases (39.5%). Smoking and loss of taste were associated with the appearance of various skin rashes. However, no prognostic implications were found between cutaneous manifestations and outcome.

Conclusion

COVID-19 infection may present with various skin manifestations including worsening of pre-existing skin diseases.

Keywords: COVID-19, cutaneous manifestations, vitiligo-like hypopigmentation, pigmented purpuric dermatosis

Introduction

COVID-19, the novel coronavirus infectious disease, has affected the whole world in a short time and become a pandemic. Its clinical manifestations have been continuously revealed.1 Various cutaneous manifestations were reported to be associated with COVID infection. Many studies described the various cutaneous manifestations and a classification of these findings was introduced.2,3

The true incidence of cutaneous manifestations is difficult to ascertain due to the lack of large prospective studies, and several literature reviews also show wide variations in the incidence ranging from 0.2% to 20.4%.1,2

The exact pathogenesis for the development of skin rashes in COVID infection has not yet been clarified. Increased expression of ACE2 expression (a ligand for Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2) and transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) could cleave the spike (S) protein of SARS-CoV-2, which facilitates the fusion of SARS-CoV-2 and cellular membranes of various cells including keratinocytes, eccrine gland epithelial cells, and the basal layer of hair follicles, monocytes, macrophages, platelets, and endothelial cells.4 This in turn can facilitate the entry of COVID-19 virus into various cells. The wide distribution of ACE 2 could explain the multisystem involvement including cutaneous involvement by COVID infection. The elevated level of soluble ACE 2 was shown to be associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality associated with COVID-19 infection independent of other risk factors.5 On the other hand, a study where skin biopsies from COVID-19 infected patients were examined by immunohistochemical labeling for ACE2/TMPRSS2 expression found no significant difference in the expression of these molecules compared to healthy controls, which indicates a possible role for other molecules.6 Additionally, the “inflammatory storm” associated with COVID infection may induce various cutaneous rashes. However, other mechanisms may also be involved in developing skin rashes in COVID patients.7 Drugs used to treat COVID infection may also be a potential cause for these rashes.

Another important question related to skin manifestations in COVID-19 patients is whether having a skin rash carries any prognostic implications. A systematic review (Jamshidi P. et al 2021) found a prognostic implication for certain cutaneous manifestations namely vascular rashes which were associated with a worse prognosis.8 Another systematic review (Holmes Z, 2022) raised the possibility of prognostic implication for cutaneous involvement although results were not confirmatory due to possible confounding factors especially age, comorbidities, and the use of medications.9

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

This is a cross-sectional observational study that included patients who were diagnosed with COVID-19 by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and admitted to King Abdullah University Hospital (KAUH) as moderate-to-severe cases for treatment either to floor or ICU during the period January–May 2021.

All patients that were admitted were asked to participate in the study and if they were willing they were included. Patients with the moderate disease are defined as patients who show evidence of lower respiratory diseases during clinical assessment or imaging and who have an oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry (SpO2) ≥94% on room air at sea level and patients with severe disease defined as patients who have SpO2 <94% on room air at sea level, a ratio of arterial pressure of oxygen of fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) <300mmHg, a respiratory rate >30 breaths/min, or lung infiltrate >50%.

All patients were asked to sign an informed consent for participation in the study and photographic documentation of their skin rashes and were informed about the purpose of the study.

Data Collection

Demographic and clinical data including age, sex, smoking, comorbidities, and previous skin diseases were collected from all patients. The presenting symptoms at the time of admission were recorded including fever, loss of taste, loss of smell, fatigue, runny nose, and respiratory symptoms (cough and difficulty breathing). The treatment used to treat patients was also recorded. All patients were examined clinically for the presence of skin manifestations and the type of skin rash (if present) was documented and categorized into one of 5 groups: A. Exanthema: morbilliform, papulovesicular, varicella-like. B. Vascular: chilblain-like lesions, purpuric/petechial, liveoid lesions. C. Reactive erythemas: Urticaria, Erythema multiforme. D: other skin rash and O for oral involvement

Photographic documentation of rashes was done. Patients were followed for the outcome in terms of recovery and discharge from the hospital or death.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS software version 20. The median and inter-quartile range (IQR) are provided for quantitative variables. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board committee (IRB) at Jordan University of Science & Technology (IRB number 25/137/2021) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

This study included a total of 821 patients (356 females and 465 males) with moderate-to-severe COVID-19. More than half of patients (54.6%) aged >60 years, 24.2% aged 50–60 years, and 21.2% aged <50 years. Only seven patients (0.85%) were under 18 years of age. Five patients (0.006%) had a severe infection requiring ICU admission; the remainder, with moderate severity COVID infection, were admitted to the floor. None of the severe-ICU admitted patients developed a skin rash.

Of the total admitted patients (821 patients), 46 (0.06%) had a pre-existing skin disease. Eczema (24 patients) was the most common skin condition followed by psoriasis (9 patients). Other skin pre-existing conditions include vitiligo (three patients), chronic spontaneous urticaria (three patients), bullous pemphigoid and recurrent boils (two patients each), lichen planus, discoid lupus, and recurrent oral ulcers one patient each. Five patients (Eczema 2, psoriasis 2, and bullous pemphigoid 1) developed a skin rash but this was not statistically significant. It is worth mentioning that one of the psoriasis patients developed erythroderma during his COVID infection.

As for smoking, 135 patients were smokers while 686 patients were non-smokers. Among smokers (n=135) Skin rash was seen in 16 patients (11.9%), while in non-smokers (n=686) 46 patients (6.7%) developed a skin rash. The difference was statistically significant (P=0.039).

As for comorbid conditions, most patients (n=678, 82.6%) had at least one comorbid condition. The most common comorbid conditions include Diabetes mellitus (n=378, 46%), Hypertension (n=463, 56.4%), ischemic heart disease (n=108, 13.2%), chronic kidney disease (n=50, 6%), gout (n=28, 3.4%), hypothyroidism (n=44, 5.4%), bronchial asthma (n=22, 2.7%), stroke (n=24, 2.9%), benign prostate hypertrophy (n=25, 3%). Less common comorbid conditions recorded include rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, Familial Mediterranean Fever, Behcet’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, Parkinson’s disease, myasthenia gravis, and others. No statistically significant association between comorbid conditions and developing skin rash was noticed (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Incidence of Rashes Among Patients According to Their Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Variable | Rash | Total | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||

| n | % | N | % | N | ||

| Age | 0.652 | |||||

| <50 | 158 | 90.8 | 16 | 9.2 | 174 | |

| 50–60 | 185 | 93.0 | 14 | 7.0 | 199 | |

| >60 | 416 | 92.9 | 32 | 7.1 | 448 | |

| Sex | 0.616 | |||||

| Female | 331 | 93.0 | 25 | 7.0 | 356 | |

| Male | 428 | 92.0 | 37 | 8.0 | 465 | |

| Smoking | 0.039 | |||||

| No | 640 | 93.3 | 46 | 6.7% | 686 | |

| Yes | 119 | 88.1 | 16 | 11.9% | 135 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.463 | |||||

| No | 404 | 91.8 | 36 | 8.2 | 440 | |

| Yes | 355 | 93.2 | 26 | 6.8 | 381 | |

| Hypertension | 0.814 | |||||

| No | 330 | 92.7 | 26 | 7.3 | 356 | |

| Yes | 429 | 92.3 | 36 | 7.7 | 465 | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 0.247 | |||||

| No | 659 | 92.0 | 57 | 8.0 | 716 | |

| Yes | 100 | 95.2 | 5 | 4.8 | 105 | |

| Kidney disease | 0.707 | |||||

| No | 696 | 92.6 | 56 | 7.4 | 752 | |

| Yes | 63 | 91.3 | 6 | 8.7 | 69 | |

| CTD | 0.107 | |||||

| No | 713 | 92.8 | 55 | 7.2 | 768 | |

| Yes | 46 | 86.8 | 7 | 13.2 | 53 | |

| Sancovir | 0.328 | |||||

| No | 677 | 92.9 | 52 | 7.1 | 729 | |

| Yes | 81 | 90.0 | 9 | 10.0 | 90 | |

| Remdesivir | 0.712 | |||||

| No | 612 | 92.7 | 48 | 7.3 | 660 | |

| Yes | 147 | 91.9 | 13 | 8.1 | 160 | |

| Dexamethasone | 0.805 | |||||

| No | 66 | 91.7 | 6 | 8.3 | 72 | |

| Yes | 688 | 92.5 | 56 | 7.5 | 744 | |

The treatment used for admitted patients includes dexamethasone (743 patients), Remdesivir (160 patients), Sancovir (90 patients), IV antibiotics 775 patients (Levofloxacin, Tazocin, Impenem, and others) in addition to oxygen therapy. No statistically significant association was found between the treatment used and the development of skin rashes (Table 1).

Table 2.

Appearance of Rash According to COVID Symptoms

| Rash | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Total | ||||

| N | % | n | % | N | ||

| Fever | 0.127 | |||||

| No | 242 | 94.5% | 14 | 5.5% | 256 | |

| Yes | 516 | 91.5% | 48 | 8.5% | 564 | |

| Fatigue | 0.187 | |||||

| No | 91 | 95.8% | 4 | 4.2% | 95 | |

| Yes | 665 | 92.0% | 58 | 8.0% | 723 | |

| Cough | 0.469 | |||||

| No | 111 | 94.1% | 7 | 5.9% | 118 | |

| Yes | 647 | 92.2% | 55 | 7.8% | 702 | |

| Loss of taste | 0.012 | |||||

| No | 583 | 93.7% | 39 | 6.3% | 622 | |

| Yes | 174 | 88.3% | 23 | 11.7% | 197 | |

| Running Nose | 0.449 | |||||

| No | 633 | 92.1% | 54 | 7.9% | 687 | |

| Yes | 126 | 94.0% | 8 | 6.0% | 134 | |

| Loss of smell | 0.067 | |||||

| No | 601 | 93.3% | 43 | 6.7% | 644 | |

| Yes | 157 | 89.2% | 19 | 10.8% | 176 | |

| Pruritus | ≤0.001 | |||||

| No | 723 | 93.3% | 52 | 6.7% | 775 | |

| Yes | 31 | 75.6% | 10 | 24.4% | 41 | |

The presenting symptoms including fever (n=564), loss of taste, loss of smell, fatigue, runny nose and respiratory symptoms (cough and difficulty breathing) were seen in the majority of patients. No statistically significant relation was found between any of these symptoms and the development of skin rashes (Table 2).

Of the total 821, 62 patients (7.55%) developed a cutaneous rash; of those 43 (5.24%) had skin rash and 19 (2.31%) had an oral rash. Figure 1 shows the distribution of various cutaneous manifestations in these patients. Around one-third of patients (n=19/62, 30.6%) had oral thrush. Reactive erythemas were seen in 10 patients (1.2%) of the total admitted patients (urticarial/9 patients and erythema multiforme/1 patient). Vascular cutaneous rashes (purpura/5 patients, petechia/2, ecchymosis/1, and vasculitis/1) were seen in nine patients (1.1%) of total admitted patients, while exanthema (5 morbilliform, 2 vesiculopapular) was seen in 7 cases (0.009%). On the other hand, 17 patients (2%) developed a variety of skin rashes including (reactivation of herpes simplex/7 patients, a flare-up of eczema/4 cases, acneiform eruption/3, pigmented purpuric dermatosis/1, vitiligo-like hypopigmentation on acral sites/1, and flare up of pre-existing psoriasis/1 patient). Figures 2 and 3 show examples of cutaneous rashes seen in these patients. Regarding the onset of rash, 70% of patients developed a rash after admission while 30.0% had a rash before admission. The localization of rash was variable; oral (30.6%), 15.3% had a rash on the head, 1.7% on the neck, 15.3% on the upper limbs, 10.2% on the lower limbs, and 26.9% on the chest or trunk. About 6.8% of patients had a generalized rash. Rashes were asymptomatic in more than one-third of patients (38.6%) and were itching or painful in 61.4% of patients. The duration of the rash varied from 1 to 30 days with a mean (SD) of 7.45 (±5.5) days.

Figure 1.

The distribution of the types of rashes in patients with COVID-19 infection*. *Patients with oral rash were not included.

Figure 2.

Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19; (A) erythema multiforme, (B) petechial rash, (C) herpes simplex, (D) urticarial rash.

Figure 3.

New skin manifestations (A) pigmented purpuric dermatosis (B) vitiligo-like rash.

The vascular rash was more common among males (six males vs three females) while exanthema, reactive erythema and oral thrush were more common among females, and this difference was not statistically significant.

The appearance of skin rash was analyzed in relation to demographic data, smoking, presence of pre-existing medical illness, and type of treatment (Table 1). Among these factors, smoking was found to be a significant factor in developing rash during COVID infection (P=0.03). However, analysis for demographic data, co-morbid conditions and treatment did not show any statistical difference in developing a cutaneous rash. The presence of various COVID-related symptoms was also analyzed for the appearance of skin rash (Table 2) and patients with loss of taste (P=0.012) and smell (p=0.06) were more likely to have rashes, although this did not reach statistical significance for loss of smell. Patients who had pruritus were likely to have a skin rash compared to those without pruritus (P= 0.001).

Table 3.

Original Articles Reporting Cutaneous Manifestations of COVID-19

| Study | Number of Cases with Cutaneous Manifestations | Gender | Age (Years) | Onset of Symptoms No. of Patients (Time) | Pseudo-Chilblain/ Pernio Like/Acral Necrosis | Vesicular/Varicella Like | Maculo-Papular Exanthema | Urticarial | Others (No. of Patients) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marzano et al22 | 22 | 16 (M) 6 (F) | 60 (median) | After 3 day median latency | - | 22 | - | - | - |

| Recalcati et al2 (n=88) | 18 | NA | 8 (simultaneously) 10 (after) | - | 1 | 14 | 3 | - | |

| Guarneri et al23 (n=125) | 13 | NA | NA | 3 | - | 2 | 2 | Panniculitis (3) reactivation of oral herpes simplex (2) |

Note: “n” is the number of COVID-19 confirmed cases reported in the study.

In terms of outcome for these patients, unfortunately, almost one-quarter (24.4%) of patients died and 75.6% of patients recovered. No significant association was found between having a rash and the outcome of recovery or death (p=0.558).

Discussion

COVID-19 has almost affected the entire population of Earth in almost all living aspects including social, financial, medical, and travel, and within a few months, the world was brought to a standstill.

The clinical manifestations of this infection were gradually unveiled, and it was shown that this infection can affect almost all body systems including skin.10

Several studies have been done on the cutaneous manifestations seen in COVID-19 patients since the disease’s appearance.11–18 Zhao et al (2020) showed that skin lesions were polymorphic; and the most common types were erythema, urticarial and chilblain-like lesions.11 Jindal et al (2020) studied 458 confirmed COVID-19 cases and showed that the most common cutaneous manifestations were macular/maculopapular involving 42.5% of study cases.12 A large nationwide case collection survey has been conducted in Spain that included 375 cases and described five clinical patterns and the association of these patterns with patients’ demographics, the patterns were: pseudo-chilblain, urticarial lesions, maculopapular eruptions, other vesicular eruption, and livedo or necrosis.3

Our study focused on inpatients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 who required admission to the hospital for treatment. Like other studies, most of these patients were above the age of 50 years, which emphasizes the importance of age as a predictor for having a more severe COVID-19 infection,19 skin findings were significantly associated with severe or critical cases.20 In this cohort of patients with moderate-to-severe infection, around 7.5% had a cutaneous rash (5.2% skin and 2.3% oral thrush). The most common cutaneous manifestations seen in this group include reactive erythema, exanthema, vascular, and reactivation of pre-existing skin conditions. These findings were also reported by previous studies, Table 3 shows some early Italian cases; however, there is wide variation in the literature regarding cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 infection.21 In this cohort, Vitiligo-like hypopigmentation (one patient) and pigmented purpuric dermatosis (one patient) were documented during the study. To the best of our knowledge, these two findings were not previously reported in association with COVID-19 infections. This shows that the spectrum of manifestations that may accompany COVID infections will continue to evolve, and we think newer findings will be reported over time. These rashes could be related to the immune dysregulation that is associated with this infection. Also, the newer strains of COVID may provoke different immune reactions and hence this may lead to manifestations not previously reported.

The appearance of oral thrush was seen in 19/821 (2.3%) of patients with COVID-19. Several studies described the appearance of various oral manifestations with COVID-19 infection including oral thrush.24–26 The occurrence of oral thrush (oral candidiasis) as an opportunistic infection in severely ill patients is well known. Additionally, other factors related to treatment including the use of steroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics in severe COVID-19 infections can also be contributory factors. Smoking is a recognized risk factor for developing severe COVID −19 infection.27 In this study, smokers were more likely to have a skin rash but whether this is a true relation or a reflection of having a more severe infection remains to be confirmed. Another interesting finding in this study is the significant association between a loss of taste and the development of skin rashes. A case report of a child was described with loss of taste and the subsequent appearance of rash due to COVID-19 infection.28 Further studies are needed to confirm this association, especially since both rashes and loss of taste are common findings in COVID −19 infection. Patients with various skin rashes were likely to have pruritus as the predominant symptom. It is worth mentioning that patients with pruritus were likely to have a skin rash. In the current series of patients with COVID-19 infection, no patients with chilblain-like lesions were seen. This may be because most of these cases were reported in children with COVID-19 infection and in this study, only a few patients were in this age group.3,29,30

Conclusions

The cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 are variable. Oral thrush, reactive erythemas, vascular disorders, and exanthema are the most common ones in older patients with moderate-to-severe infections. Worsening or reactivation of preexisting skin conditions can also appear. Vitiligo-like hypopigmentation and pigmented purpuric dermatosis are described for the first time in this cohort. Smoking and loss of taste may predict the appearance of skin rash in patients with more severe COVID-19 infections. In this cohort of COVID-19 patients, having cutaneous involvement did not have any prognostic implication for recovery or death. Further Studies on cutaneous manifestations in patients with severe COVID infections can provide more information about this continuously evolving disease.

Study Limitations

The number of patients is relatively small; a study with larger numbers may provide more information on cutaneous manifestations seen in moderate and severe COVID infections.

Acknowledgment

The study was supported by a research grant from the deanship of Research at Jordan University of Science and Technology.

Funding Statement

The study was supported by a research grant from deanship of research at Jordan University of Science and Technology, Grant number [20210060].

Data Sharing Statement

Data used in this article are available on request from the corresponding author.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e212–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galván Casas C, Catala AC, Carretero Hernández G, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID‐19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(1):71–77. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong M, Zhang J, Ma X, et al. ACE2, TMPRSS2 distribution and extrapulmonary organ injury in patients with COVID-19. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;131:110678. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oudit GY, Wang K, Viveiros A, Kellner MJ, Penninger JM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2-at the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cell. 2023;186(5):906–922. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cazzato G, Cascardi E, Colagrande A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and skin: new insights and perspectives. Biomolecules. 2022;12(9):1212. doi: 10.3390/biom12091212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.González González F, Cortés Correa C, Peñaranda Contreras E. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with COVID-19: clinical characteristics and possible pathophysiologic mechanisms. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112(4):314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2020.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamshidi P, Hajikhani B, Mirsaeidi M, Vahidnezhad H, Dadashi M, Nasiri MJ. Skin manifestations in COVID-19 patients: are they indicators for disease severity? A systematic review. Front Med. 2021;8:634208. PMID: 33665200; PMCID: PMC7921489. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.634208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes Z, Courtney A, Lincoln M, Weller R. Rash morphology as a predictor of COVID-19 severity: a systematic review of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19. Skin Health Dis. 2022;2(3):e120. doi: 10.1002/ski2.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siddiqi HK, Libby P, Ridker PM. COVID-19 - A vascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2021;31(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2020.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Q, Fang X, Pang Z, Zhang B, Liu H, Zhang F. COVID‐19 and cutaneous manifestations: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2505–2510. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jindal R, Chauhan P. Cutaneous manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 in 458 confirmed cases: a systematic review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(9):4563. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_872_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daneshgaran G, Dubin DP, Gould DJ. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: an evidence-based review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s40257-019-00475-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gisondi P, PIaserico S, Bordin C, Alaibac M, Girolomoni G, Naldi L. Cutaneous manifestations of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a clinical update. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2499–2504. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marzano AV, Cassano N, Genovese G, Moltrasio C, Vena GA. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with COVID‐19: a preliminary review of an emerging issue. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:431–442. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tammaro AN, Adebanjo GA, Parisella FR, Pezzuto A, Rello J. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: the experiences of Barcelona and Rome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martora F, Villani A, Fabbrocini G, Battista T. COVID-19 and cutaneous manifestations: a review of the published literature. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22(1):4–10. doi: 10.1111/jocd.15477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallo Marin B, Aghagoli G, Lavine K, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 severity: a literature review. Rev Med Virol. 2021;31(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan CC, Dofitas BL, Frez ML, Yap CD, Uy JK, Ciriaco-Tan CP. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in a tertiary COVID-19 referral hospital in the Philippines. JAAD Int. 2022;7:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2022.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei Tan S, Tam YC, Oh CC. Skin manifestations of COVID-19: a worldwide review. JAAD Int. 2021;2:119–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2020.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marzano A, Genovese G, Fabbrocini G, et al. Varicella-like exanthem as a specific COVID-19–associated skin manifestation: multicenter case series of 22 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guarneri C, Venanzi Rullo E, Gallizzi R, Ceccarelli M, Cannavò S, Nunnari G. Diversity of clinical appearance of cutaneous manifestations in the course of COVID-19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salehi M, Ahmadikia K, Badali H, Khodavaisy S. Opportunistic fungal infections in the epidemic area of COVID-19: a clinical and diagnostic perspective from Iran. Mycopathologia. 2020;185(4):607–611. doi: 10.1007/s11046-020-00472-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arastehfar A, Carvalho A, Nguyen MH, et al. COVID-19-Associated Candidiasis (CAC): an underestimated complication in the absence of immunological predispositions? J Fungi. 2020;6(4):211. doi: 10.3390/jof6040211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajendra Santosh AB, Muddana K, Bakki SR. Fungal infections of oral cavity: diagnosis, management, and association with COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2021 Mar 27]. SN Compr Clin Med. 2021;3:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s42399-021-00873-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gülsen A, Arpinar Yigitbas B, Uslu B, Drömann D, Kilinc O. The effect of smoking on COVID-19 symptom severity: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pulm Med. 2020;2020:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2020/7590207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maniaci A, Iannella G, Vicini C, et al. A case of COVID-19 with late-onset rash and transient loss of taste and smell in a 15-year-old boy. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e925813. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.925813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piccolo V, Neri I, Manunza F, Mazzatenta C, Bassi A. Chilblain‐like lesions during the COVID‐19 pandemic: should we really worry? Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1026–1027. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piccolo V, Neri I, Filippeschi C, et al. Chilblain‐like lesions during COVID‐19 epidemic: a preliminary study on 63 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this article are available on request from the corresponding author.