Abstract

The recent outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has exposed the fragility of the clothing supply chain operating in South Asian countries. Millions of workers have become jobless and are staring at an uncertain future. The purpose of this research is to understand the reasons behind the lack of social sustainability in the clothing supply chain operating in South Asian countries and to suggest ways for an appropriate redressal. Interviews with experts have revealed that the dominant power of some brands in the clothing supply chain is the primary reason. Unauthorised subcontracting of clothing manufacturing and the use of contract labour are also responsible for violations in the ‘code of conducts’ of social compliance. Post COVID-19, a sustainable sourcing model that incorporates disruption risk sharing contracts between the brands and suppliers should be adopted. Unauthorised subcontracting of clothing manufacturing by the suppliers must be prohibited. Supplier selection and the order allocation policies of the brands should also be tuned to facilitate social security of workers. The participation of NGOs and labour unions should be encouraged so that community development initiatives reach the grassroots level.

Keywords: Clothing, Disruption, Migrant labour, Social sustainability, South Asia, Supply chain

1. Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 has disrupted the majority of all global supply chains. Supply chain disruptions occur due to events that have a low probability of occurrence but a very high impact, such as natural disasters (floods, earthquakes, etc.), terrorist attacks, pandemics (SARS, Ebola, Swine flu, COVID-19, etc.). Unlike operational risks which involve routine delay in supply, machine failure, or demand fluctuations, disruption risks have a ripple effect as the consequences percolate through the entire supply chain and affect business operations as well as the human population. The recent outbreak of COVID-19 is arguably the most cursed pandemic in the last century (Parsons, 2020). By June 2020, it has caused deaths of around 0.5 million people while infecting around 10 million across the world. A whopping 94% of the Fortune 1000 companies have experienced supply chain disruptions due to COVID-19 (Ivanov, 2020; Fortune 2020). According to Dun & Bradstreet, among the Fortune 1000 companies, 16% and 94% have tier-1 and tier-2 suppliers, respectively, in the Wuhan region. While tier-1 suppliers provide raw materials, accessories, and assemblies to the manufacturer, tier-2 suppliers provide raw materials to the tier-1 supplier. Moreover, at least 5 million companies around the world have tier-2 suppliers located in that region (Smith, 2020). As a result, China's exports fell by 17% during January-February 2020; further, it is estimated that there could be up to a 32% decline in the global trade in 2020 (Sarkis et al., 2020). Commercial aerospace, air and travel, oil and gas, automotive, and clothing and fashion are the sectors bearing the brunt of this pandemic, whereas demand for pharmaceutical products have increased (McKinsey & Company, 2020; Yu et al., 2020). While affected countries have practiced social distancing, community quarantining, and lockdown to contain the spread of this deadly virus, widespread unemployment has caused social sustainability challenges along with economic distress. The International Labor Organization (ILO) has estimated that there could be up to 25 million jobs lost as a result of the COVID-19 crisis.

In last two decades, researchers have addressed various facets of supply chain risk management, including risk identification, assessment, mitigation, and monitoring. While building resilience in supply chain has been proposed to tackle supply chain risks, the COVID-19 outbreak has proved beyond a doubt that even the best combinations of traditional strategies like agility, robustness, flexibility, redundant capacity, surplus inventory (Chopra and Sodhi, 2004; Hassini et al., 2012; Heckman et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2015; Majumdar et al., 2020) are not enough to cope with this particular global pandemic. As the global supply chain extends beyond the geographic boundaries of a country, suppliers are often located in different countries (Linton and Vakil, 2020). While this global network works efficiently in a stable business environment, supply chain disruption can cause havoc during pandemics.

Most of the developing economies of the world, including those in South and Southeast Asia, rely on textile and clothing industries as the entry barrier is low, technology is easily manageable, and skills can be quickly acquired. The present value of the Indian textile and clothing sector is around US$ 200 billion, and it is anticipated to grow at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 12% to US$ 350 billion by 2024. In 2018-19, it contributed 3% to India's gross domestic product (GDP), 13% to industrial production, and 12% to export earnings besides providing direct employment to a workforce of around 45 million. Bangladesh, with 6.4% global share, is the second largest exporter of clothing after China. The textile and clothing industry contributes 16% and 80% to Bangladesh's GDP and export earnings, respectively, while employing around 4 million workers (Majumdar and Sinha, 2019). Vietnam is the third largest exporter of clothing with 6.2% global share. The sector provides around 2.5 million employment. There are around 6000 textile and clothing companies in Vietnam, and 70% of them operate in the clothing manufacturing area. In Cambodia, along with tourism, textile and clothing is one of the two largest industries. Cambodian textile and clothing industry employs around 3.35 million workers and 90% of them are female. Overall, the textile and clothing industry, being labour intensive, plays pivotal roles in the economy and employment of South and Southeast Asian countries.

For the overall sustainability of the clothing industry and associated supply chain, it is paramount to integrate three pillars of sustainability, namely economic, environmental, and social, so that a balance between profit, planet, and people is maintained (Jabbour and Santos, 2008; Khan et al., 2018; Pomponi et al., 2019). Ensuring social sustainability not only enhances the operational performance but also improves the financial success of organisations (Schönborn et al., 2019). However, social sustainability has always received inadequate attention from researchers and practitioners, especially in the context of emerging economies (Huq et al., 2014; Mani et al., 2016; Amui et al., 2017; Mani and Gunasekaran, 2018; Munny et al., 2019). Low wages (Lipschutz, 2004), forced overtime (Maria-Ariana, 2017), poor health and safety practices (Yawar and Seuring, 2017; Mani et al., 2018), substandard working conditions (Lipschutz, 2004; Maria-Ariana, 2017), and threats of lay-off are some of the most common social sustainability issues of supply chain. In spite of contributing greatly to the economy of South and Southeast Asian countries, the workers of clothing industry have always remained underprivileged due to poor wage rates (<US$ 5 per day). It is not an overstatement to say that the extremely poor wage rate is the main driver behind the flourishing of the clothing industry in South and Southeast Asia (Lipschutz, 2004; Maria-Ariana; 2017). The outbreak of COVID-19 has exposed the vulnerability and lack of social security of these workers who contribute to the glittering success of the clothing industry. Unlike other supply chain disruptions, COVID-19 has created a ripple effect in clothing supply chain. First, the supply of clothing raw materials from China was disrupted due to lockdown in Wuhan which started in January 2020. The clothing manufacturers in South East Asia tried to cope with the situation by using surplus inventory, and by procuring from local suppliers. However, demand for clothing declined sharply as lockdown started in parts of Europe during the second week of March 2020. Global clothing brands reacted by cancelling confirmed orders or by delaying the payment (Donaldson, 2020). As the disease started to spread in South Asia, lockdown was announced in India and Bangladesh in the last week of March 2020, bringing clothing industry to a complete standstill. Therefore, COVID-19 created an unprecedented situation in clothing supply chain where demand, supply and manufacturing got completely disrupted and delinked (Wazir Advisors 2020). According to the Clothing Manufacturers Association of India (CMAI), there will be around 10 million jobs lost in the Indian textile value chain (Economic Times report, 2020). A survey conducted by CMAI among 1,500 clothing manufacturing units revealed that 20% of them have considered permanently closing their business following lockdown. In Bangladesh, US$ 3.17 billion in orders have been cancelled affecting around 2.27 million workers (Wright and Saeed, 2020). Cambodia's government predicted that as many as 200 factories, employing around 160 thousand workers, might temporarily close their operations by the end of March (Hutt, 2020). The ongoing discussion highlights the severe impact of COVID-19 on social sustainability of clothing supply chain operating in South and Southeast Asia. The objective of this research is to unearth the underlying reasons behind the lack of social security in the clothing supply chain. The strategies needed in post-COVID-19 era and the roles of various actors to improve the social security of workers in the clothing supply chain have also been proposed. This paper makes unique contributions by deliberating on the specific issue of social security in clothing supply chain due to disruptions caused by COVID-19 and ways to mitigate this problem. The remainder of the paper is arranged as follows. Section 2 presents the research methodology, and Section 3 discusses results obtained. Finally, Section 4 outlines the conclusions.

2. Research methodology

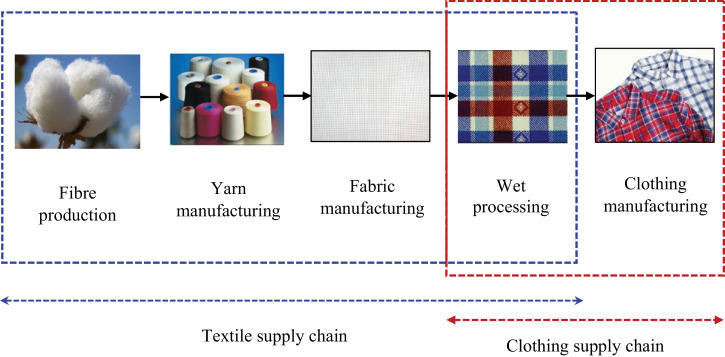

Fig. 1 depicts the textile and clothing supply chain which can be divided into five segments, namely fibre production, yarn manufacturing, fabric manufacturing, wet processing (dyeing, printing, and finishing), and clothing manufacturing.

Fig. 1.

Textile and clothing supply chain.

To understand the causes behind the lack of social security in clothing supply chain, an explanatory research approach was used. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to capture the perception and empathic understanding of the stakeholders involved. The interview themes revolved around the power imbalance among the players of the clothing supply chain, social security practices followed by the organisations, and the ways to improve the social security of workers in the clothing supply chain. While conducting interviews, a funnel approach was used to present the questions, i.e., general questions were asked in the beginning before moving to the specific questions vital to the interview themes. Fourteen senior managers, working in sourcing (brand), clothing manufacturing (supplier), and sustainability auditing (third party) of textile and clothing supply chain were telephonically interviewed. Seven of the interviewees represented the brands’ side whereas five were from the suppliers’ side. The remaining two interviewees were working in the sustainability auditing area. All the interviewees had at least 14 years of experience in the textile and clothing supply chain, except one, who had 10 years of experience. Interviewees were selected based on personal contacts or through reference of a previous interviewee. As the matter of discussion was sensitive, personal contacts were helpful to have open discussions. At the end of 14th interview, it was felt that information was reaching the saturation level, so no further interviews were conducted. Details of the interviewees are given in Table 1 . The detailed questions for the brands, suppliers, and third party auditors are given in supplementary information. For the secondary data, research papers and current industry reports were analysed to collate information related to social sustainability aspects of the textile and clothing supply chain during COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1.

Profile of interviewees.

| S. No. | Designation | Experience (years) | Supply chain position | Operation | Revenue (million US$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sales head | 18 | Brand | Multinational | 2500 |

| 2 | Senior general manager | 18 | Auditing and certification | Multinational | 30 |

| 3 | Quality assurance head | 23 | Brand | India | 350 |

| 4 | Divisional merchandise manager | 17 | Brand | Multinational | 16600 |

| 5 | Sourcing head | 23 | Brand | China, India | 370 |

| 6 | Manager | 18 | Brand | India | 2900 |

| 7 | Vice president | 25 | Supplier | Multinational | - |

| 8 | Regional manager | 15 | Supplier | Bangladesh, India | 50 |

| 9 | Production & quality head | 14 | Brand | Multinational | 12800 |

| 10 | Production manager | 10 | Supplier | India | 33 |

| 11 | Senior general manager | 23 | Supplier | India | - |

| 12 | Senior manager | 20 | Brand | China, India, Bangladesh | 330 |

| 13 | Lead auditor | 18 | Auditing and certification | Multinational | 6600 |

| 14 | Senior general manager | 15 | Supplier | Multinational | 3500 |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Supply chain disruption

Several interviewees suggested that because China is a fundamental cog in the textile and clothing supply chain, any pandemic in that country will produce a cascading effect on the entire supply chain. China supplies value-added synthetic fibres, synthetic fabrics, winter-wear fabrics, footwear, polyurethane tapes, clothing accessories, nonwoven roll goods, dyes, and chemicals to South Asian countries. The interviewees affirmed that they had never imagined how devastating a disruption in supply, demand, and operation could be, and yet they had to witness such disruptions happening simultaneously in this case.

“This is a unique situation where we have infrequent supply, partial production, and very low demand. Some of our Indian stores open only for few hours a day. Our revenue has reduced by 90% in last month.”

Interviewee 6

They also felt that the clothing supply chain will take at least six to nine months to recover post lockdown as the production will start in phases; therefore, the requirement of labour will be lower.

“Even if the lockdown is over, we will not be keen to start the production as 40% of our denims are sold in domestic market. Unless the markets and malls open in metro and big cities, there is no point in producing clothing for which there are no takers.”

Interviewee 7

3.2. Power dominance of brands

Most of the interviewees agreed with the notion that brands hold the dominant power in the clothing supply chain. Therefore, brands have always dictated price, delivery terms, and conditions. Over the years, brands have maintained their profit margin while transferring the burden of cost cutting to the suppliers. Since the Rana Plaza disaster in 2013, lead times, prices paid to suppliers, and wages have reduced by 8%, 13%, and 6%, respectively (Saxena, 2020). Thus, fierce cost competitiveness among the suppliers results in poverty pay for the workers leaving no margin for the social security. Brands typically pay after delivery of goods, forcing the suppliers to pay for raw materials, labour, and overhead costs; hence, suppliers shoulder almost entirely all business risks.

“We pay our clothing suppliers within a stipulated window of three months after the receipt of goods. We also make arrangements with the fabric manufacturers so that the clothing suppliers get a window of two months for payment after receiving the fabric.”

Interviewee 3

Although collaboration among the supply chain partners is one of the potent strategies for risk mitigation, unfortunately, it has limited adoption in clothing supply chains. With suppliers having little or no bargaining power, brands have used their dominant power positions to cancel or postpone orders that have been completed or are in production; forced the suppliers to offer brutal discounts; and refused to pay on stipulated time. A whopping 72.1% and 91.3% of the buyers have refused to pay for the fabric cost and production cost (labour, manufacturing overhead etc.), respectively, to the suppliers from Bangladesh (Anner, 2020). Interviewees from the suppliers’ side felt that some of the brands unethically invoked the force majeure clause for their impunity. However, with looming fear of losing business, suppliers often have little choice but to comply.

“We have asked our suppliers to completely hold the orders for which they were sourcing materials. Suppliers were also asked to stop ongoing production. Suppliers do not have any choice but to accept our decision.”

Interviewee 6

3.3. Subcontracting of manufacturing and labour by suppliers

Interviewees agreed that unauthorised subcontracting of clothing manufacturing is widely practiced by the suppliers. The social sustainability ‘code of conducts’ are set by the brands and the evaluation is often done by the third party auditors.

“We have long-term relations with our suppliers. We follow our own social compliance standard as well as audits by a third party. Suppliers are mentored in the areas of noncompliance.”

Interviewee 4

However, suppliers felt that economic considerations are given more importance for supplier selection as compared to the other two dimensions of sustainability; in short, they are often forced to adopt subcontracting of clothing manufacturing.

“While selecting our suppliers, we first look at the economic sustainability. Social sustainability comes after that and the suppliers need to fulfill our own standards which are in line with SA 8000 and SMETA (SEDEX members ethical trade audit).”

Interviewee 9

In many cases, mock compliance is practiced with the connivance of brands to meet the strict deadline. Though on paper, records are unscrupulously maintained to meet the compliance. One of interviewees representing a prominent brand accepted the existence of mock compliance.

“We conduct three types of sustainability audits, namely unannounced, semi-announced, and announced, for our suppliers. Generally, most of the suppliers have poor compliance in overtime and subcontracting where the records are either missing or dubious.”

Interviewee 1

While the showcase factory of a supplier comes under the purview of inspection and compliance, subcontracted factories remain invisible. Thus, violations of social sustainability norms are rampant in subcontracted units. The mere monitoring by third party auditors has failed to serve the purpose as the compliance process is more concerned with box ticking rather than redressal of the actual problem. Besides, unethical practices like bribing are often used by the suppliers to further cloak the occurrence of malpractices.

Another important aspect highlighted by the interviewees is the widespread use of contract labour in clothing manufacturing. Most of the suppliers operate with 80-90% contract labour arranged through middlemen. A middleman supplies labours to a large number of factories based on requirements that vary depending on order volume. Therefore, the workers are not on the payroll of the suppliers. Though as per industrial laws, the suppliers still remain responsible for the safety of the workers inside the factory premises. However, the suppliers do not have any moral or legal obligation to ensure social security of the workers if the job is terminated. As most of the Indian clothing manufacturers are dependent on Spring/Summer orders, the order quantity from the brands varies with the seasons. A further variation of demand occurs within each season. Interviewees, therefore, felt that it is economically unfeasible for the suppliers to maintain a steady workforce under their own payroll. As the middleman supplies contract labour to multiple factories, he takes advantage of resource pooling by utilising uncorrelated demand of factories. The middleman operates independently, so unethical practices of layoff and the careless disregard for workers’ social security goes unnoticed.

3.4. Mitigation strategies

It emerged during the interviews that the government should play a proactive role in ensuring social security of jobless workers as clothing suppliers, which mostly fall under micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSME), do not have the liquidity to sustain during an extended economic crisis. Permanent workers in Bangladesh are entitled to get 60 days’ pay at the time of termination according to the labour law. Some of the interviewees suggested that this benefit should also be applicable for contract labour. Interviewees pointed out that Cambodia's government promised workers rendered jobless due to factory closure that they are eligible to get 60% of the national minimum wage for a period of six months. In Sri Lanka, workers are entitled to paid leave in areas where factories have been closed temporarily (Zarocostas, 2020). Some of the interviewees felt that the demand for clothing will surge once the COVID-19 crisis is over. However, cash-starved clothing companies, especially the smaller players, may face difficulties in restarting their operations due to lack of trained workers, many of whom have already returned to their native places.

“The trauma that the migrant workers have faced has left a permanent scar in their minds. Some of them have decided not to leave their home state again. However, others have no option but to return.”

Interviewee 3

Therefore, a disruption risk management policy, that is friendly to the workers, is of paramount importance to reduce the sufferings of migrant workers. The interviewees also expressed that the government could offer support to the clothing manufacturers in several other forms: a moratorium for payment of bank interest and principal, an exemption of anti-dumping duty, and a bank interest reduction are all steps that would help the clothing industry revive faster and mitigate the trauma of workers.

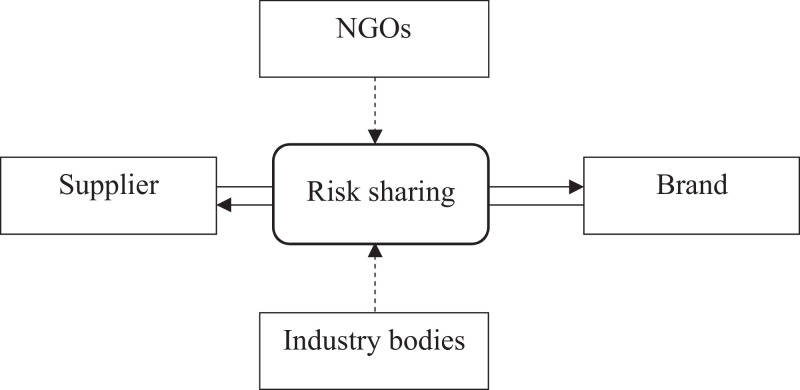

Many interviewees asserted that post COVID-19, brands will face pressure from industry bodies, NGOs, and human rights organisations to ensure that workers receive a living wage to fulfill their basic requirements (food, clothing, housing, education, and contingent expenses) and to ensure a decent life. The practice of paying poverty wages to the workers and thereby making them eternally dependent on public welfare schemes should be stopped by the brands. Therefore, a new sourcing model is needed where brands and suppliers, mediated by industry bodies (CMAI, Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association or BGMEA, etc.) or NGOs, are involved in sustainable partnerships as shown in Fig. 2 . The sourcing model must include risk sharing contracts for equitable sharing of loss by both parties in the event of unforeseeable disruptions. The role of industry bodies or NGOs would be to oversee that social issues such as child labour, forced labour, non-voluntary labour, excessive overtime, discrimination, health and safety, fair wage, contingency savings, and so forth are unequivocally mentioned and practiced by all parties. Interviewees also suggested that if a supplier has procured the raw materials but has not yet started the clothing manufacturing, then the brand should partially compensate for the cost of raw materials, i.e., fabrics in the case of order cancellation. If the clothing is under production (cut and stitch), then the brand should partially pay for fabrics and manufacturing cost, including labour cost. For delaying the shipment, the brand should pay for the additional inventory holding cost.

Fig. 2.

Sourcing model for risk sharing.

It is obvious that brands will have to bear the burden of extra cost arising from the risk sharing. However, this can be included in the pricing model as the social sustainability cost which may be integrated with their corporate social responsibility (CSR) expenditures. An adoption of this sourcing model will help the brand to enhance their image as a sustainable organisation. Some interviewees suggested that brands should give preference during supplier selection and order allocation to the suppliers who employ a permanent workforce. This will encourage suppliers to avoid contract labour, at least partially, and will ensure better job security for the workers. Besides, to mitigate future disruption risks, brands should blend ‘Localisation’ with ‘Globalisation’ to form the novel ‘Glocalisation’ as a new sourcing strategy to reduce their dependency on a single supplier or country. The interviewees representing suppliers felt that post COVID-19, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Cambodia can utilise this opportunity as credible alternatives for the new brands.

“We have received lot of queries, during this COVID-19 crisis, from new foreign buyers regarding our production capacity and lead time.”

Interviewee 14

Interviewees also suggested that because workers are primarily associated with the suppliers, they must take greater responsibility for the social security. Ideas such as offering a mandatory saving plan, providing access to emergency savings, staffing day care centres, etc. came up during the interviews. The active and constructive engagement of the labour unions should be encouraged by the suppliers even if the powerful brands feel that third party auditing is better for ensuring the social sustainability in supply chain.

3.5. Limitations and future directions

A first-hand view of social sustainability issues in the clothing supply chain of South Asia due to the COVID-19 outbreak has been presented. Our findings are primarily based on semi-structured interviews with industry experts. Due to social distancing, all the interviews were conducted telephonically. It would have been better to conduct in-depth face-to-face interview with all the stakeholders of the clothing industry.

We propose the following research questions on which future research should be initiated.

-

•

How will the power dominance between brands and suppliers change in the clothing supply chain post COVID-19?

-

•

How will the sourcing strategies and pricing models of clothing change post COVID-19?

4. Conclusions

An explanatory research based on semi-structured interviews of experts has been presented with the aim to unearth the reasons behind the lack of social sustainability in the clothing supply chains of South Asia. It has emerged that the power dominance of clothing brands, unauthorised subcontracting of clothing manufacturing, and use of contract labour by suppliers are the major causes plaguing the social security in clothing supply chains operating in South Asia. As a mitigation strategy, brands, suppliers, industry bodies, and NGOs must work in unison following the COVID-19 crisis to address the lack of social security in the clothing supply chain. A new sourcing model, which would include disruption risk sharing contracts and social safety benefits for the workers, should be adopted. Brands and third party auditors must ensure that unauthorised subcontracting of clothing manufacturing is eliminated. Brands should also encourage suppliers’ use of a permanent workforce by tuning the supplier selection and order allocation policy. Experts felt that as South Asia could be the destination of many new clothing brands due to ‘Glocalisation’ strategy, the time is right for suppliers to enhance social sustainability by implementing a mandatory savings plan and access to emergency savings for workers. Although this work primarily focuses on the clothing supply chain, its findings and implications have a broad impact on many industries that depend on low-skilled workers.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests Or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.spc.2020.07.001.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Amui L.B.L., Jabbour C.J.C., de Sousa Jabbour A.B.L., Kannan D. Sustainability as a dynamic organizational capability: a systematic review and a future agenda toward a sustainable transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2017;142:308–322. [Google Scholar]

- Anner, M., 2020. Abandoned? The impact of Covid-19 on workers and businesses at the bottom of global garment supply chains, research report by Pennstate Centre for global workers’ right. Accessed through:https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340460592_Abandoned_The_Impact_of_Covid-19_on_Workers_and_Businesses_at_the_Bottom_of_Global_Garment_Supply_Chains

- Chopra S., Sodhi M.S. Managing risk to avoid supply chain breakdown. MIT Sloan Manage. Rev. 2004;46:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson T. Gap Inc. Halts Summer and Fall Orders as COVID-19 Threatens Business, April 7. Sour. J. 2020 https://sourcingjournal.com/topics/sourcing/gap-inc-pauses-summer-fall-factory-orders-covid19-coronavirus-204313/ [Google Scholar]

- Economic Times (2020). Covid -19 impact: 1 crore job cuts likely in textile industry without govt support, says CMAI, April 14, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/cons-products/garments-/-textiles/lockdown-1-crore-job-cuts-likely-in-textile-industry-without-govt-support-says-cmai/articleshow/75125445.cms

- Fortune, 2020. https://fortune.com/2020/02/21/fortune-1000-coronavirus-china-supply-chain-impact/.

- Hassini E., Surti C., Searcy C. A literature review and a case study of sustainable supply chains with a focus on metrics. Int. J. Prod. Res. Econ. 2012;140:69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann I., Comes T., Nickel S. A critical review on supply chain risk-definition, measure and modeling. Int. J. Oper. Manage. 2015;52:119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ho W., Zheng T., Yildiz H., Talluri S. Supply chain risk management: a literature review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015;53:5031–5069. [Google Scholar]

- Huq F.A., Stevenson M., Zorzini M. Social sustainability in developing country suppliers: an exploratory study in the ready made garments industry of Bangladesh. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manage. 2014;34:610–638. [Google Scholar]

- Hutt, D., 2020. Asia's garment makers hang by a Covid-19 thread, March 25, https://asiatimes.com/2020/03/asias-garment-makers-hang-by-a-covid-19-thread/

- Ivanov D. Predicting the impacts of epidemic outbreaks on global supply chains: a simulation-based analysis on the coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) case. Transp. Res. Part E. 2020;136 doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2020.101922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour C.J.C., Santos F.C.A. The central role of human resource management in the search for sustainable organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 2008;19:2133–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Khan M., Hussain M., Gunasekaran A., Ajmal M.M., Helo P.T. Motivators of social sustainability in healthcare supply chains in the UAE—Stakeholder perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018;14:95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Linton T., Vakil B. Coronavirus is proving that we need more resilient supply chains. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020 https://hbr.org/2020/03/coronavirus-is-proving-that-we-need-more-resilient-supply-chains March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lipschutz R.D. Sweating it out: NGO campaigns and trade union empowerment. Dev. Pract. 2004;14:197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar A., Sinha S.K. Analyzing the barriers of green textile supply chain management in Southeast Asia using interpretive structural modeling. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019;17:176–187. [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar A., Sinha S.K., Shaw M., Mathiyazhagan K. Analysing the vulnerability of green clothing supply chains in South and Southeast Asia using fuzzy analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1080/00207543.2019.1708988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company, 2020. Covid-19, briefing materials, April 24, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Business%20Functions/Risk/Our%20Insights/COVID%2019%20Implications%20for%20business/COVID%2019%20April%2013/COVID-19-Facts-and-Insights-April-24.ashx

- Mani V., Gunasekaran A., Papadopoulos T., Hazen B., Dubey R. Supply chain social sustainability for developing nations: evidence from India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016;111:42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mani V., Gunasekaran A. Four forces of supply chain social sustainability adoption in emerging economies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018;199:150–161. [Google Scholar]

- Mani V., Gunasekaran A., Delgado C. Enhancing supply chain performance through supplier social sustainability: an emerging economy perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018;195:259–272. [Google Scholar]

- Maria-Ariana D. Brief considerations on the rights and working conditions of employees in the textile and clothing industry globally and in Romania. Ann. Univ. Oradea Fascicle Text. Leatherwork. 2017;XVIII:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Munny A.A., Ali S.M., Kabir G., Moktadir M.A., Rahman T., Mahtab Z. Enablers of social sustainability in the supply chain: an example of footwear industry from an emerging economy. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019;20:230–242. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, T., 2020. How corona visus will affect the global supply chain, Jon Hopkisn University, March 6, https://hub.jhu.edu/2020/03/06/covid-19-coronavirus-impacts-global-supply-Chain

- Pomponi F., Moghayedi A., Alshawawreh L., D'Amico B., Windapo A. Sustainability of post-disaster and post-conflict sheltering in Africa: what matters? Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019;20:140–150. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkis J., Cohen M.J., Dewick P., Schroder P. A brave new world: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for transitioning to sustainable supply and production. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, S.B., 2020. Bangladesh's garment industry unravelling, East Asia Forum, April 24, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/04/24/persistent-danger-plagues-bangladeshs-garment-industry/

- Schönborn G., Berlin C., Pinzone M., Hanisch C., Georgoulias K., Lanz M. Why social sustainability counts: the impact of corporate social sustainability culture on financial success. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019;17:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E., 2020. Coronavirus could impact 5 million companies worldwide, new research, CNBC, February 17, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/02/17/coronavirus-could-impact-5-million-companies-worldwide-research-shows.html

- Wazir Advisors, 2020. Report on Impact of Covid-19 on Indian Textile Industry, https://wazir.in/textile-apparel-insights/industry-report

- Wright, R., Saeed, S., 2020. Bangladeshi garment workers face ruin as global brands ditch clothing contracts amid coronavirus pandemic, CNN Business, April 22, https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/22/business/bangladesh-garment-factories/index.html

- Yawar S.A., Seuring S. Management of social issues in supply chains: a literature review exploring social issues, actions and performance outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics. 2017;141:621–643. [Google Scholar]

- Yu D.E.C., Razon L.F., Tan R.R. Can global pharmaceutical supply chains scale up sustainably for the COVID-19 crisis? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarocostas, J., 2020. COVID-19 crisis triggering huge losses in textile, apparel sector, April 21, https://wwd.com/business-news/government-trade/covid-19-crisis-triggering-huge-losses-in-textile-apparel-sector-1203566328

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.