Abstract

Background:

The Together Everyone Achieves More Physical Activity (TEAM-PA) trial is a randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of a group-based intervention for increasing physical activity (PA) among insufficiently active African American women.

Design:

The TEAM-PA trial uses a group cohort design, is implemented at community sites, and will involve 360 African American women. The trial compares a 10-week group-based intervention vs. a standard group-delivered PA comparison program. Measures include minutes of total PA/day using 7-day accelerometer estimates (primary outcome), and body mass index, blood pressure, waist circumference, walking speed, sedentary behavior, light physical activity, and the percentage achieving ≥ 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous PA/week (secondary outcomes) at baseline, post-intervention, and 6-months post-intervention.

Intervention:

The intervention integrates elements from Social Cognitive Theory, Self-Determination Theory, Group Dynamics Theory, and a focus on collectivism to evaluate different components of social affiliation (relatedness, reciprocal support, group cohesion, and collective efficacy). The intervention integrates shared goal-setting via Fitbits, group-based problem-solving, peer-to-peer positive communication, friendly competition, and cultural topics related to collectivism. Compared to the standard group-delivered PA program, participants in the intervention are expected to show greater improvements from baseline to post- and 6-month follow-up on minutes of total PA/day and secondary outcomes. Social affiliation variables (vs. individual-level factors) will be evaluated as mediators of the treatment effect.

Implications:

The results of the TEAM-PA trial will determine the efficacy of the intervention and identify which aspects of social affiliation are most strongly related to increased PA among African American women.

Keywords: Physical Activity, African American Women, Randomized Controlled Trial

1. Rationale for the TEAM-PA Trial

Although there have been significant reductions in cardiovascular disease mortality in recent years, large disparities remain by sex and race.1,2 Notably, African American women experience an unequal burden of cardiovascular disease, including being twice as likely to die from cardiovascular disease compared to White women between ages 18–49.1,3 Physical activity (PA) is a key protective factor for reducing risk for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality.4,5 However, African American women experience a range of social and structural barriers (e.g., caregiver responsibilities, low access, safety concerns), which contribute to low PA.3,6–8 PA tends to decline with age,9,10 placing African American women at risk for additional health problems in older adulthood, including reduced mobility and cognitive decline.11–13 This disparity in PA, coupled with elevated cardiovascular and psychological risks, underscore the importance of developing effective interventions for engaging African American women in greater PA.

Implementing interventions in community settings that are accessible and familiar to African American women may help to reduce barriers to participation, such as distrust and distance to study site.14 Despite the promise of community settings as a critical context for reaching African American women, systematic reviews of community-based PA intervention programs have yielded mixed results.15 This may be because many community-based PA interventions for African American women have been limited by poor methodological rigor, including a lack of randomized control designs, follow-up beyond the intervention, and objective PA measures.15,16 Furthermore, while many previous studies have focused on increasing African American women’s moderate to vigorous PA (MVPA),16,17 there is increasing evidence that light physical activities are associated with improved cardiovascular health, quality of life, and reduced mortality risk.18–20 Light physical activity may be a more feasible approach for reducing sedentary behavior, yet few interventions for African American women have evaluated objective changes in total daily PA by including the full range of light to vigorous activities. Addressing these limitations, the ‘Together Everyone Achieves More Physical Activity’ (TEAM-PA) trial evaluates the efficacy of a novel group-based social affiliation intervention for increasing total PA (light to vigorous) among inactive African American women using a community-based randomized design.

1.1. Importance of Addressing Social Affiliation Mechanisms

Decades of research21–26 have highlighted social affiliation as central in the promotion of health behavior change, and have defined social affiliation through several distinct but related constructs. Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)27 highlights the importance of the group context for promoting observational learning and collective efficacy (confidence in a group’s ability to perform), while Self-Determination Theory (SDT)24 and Group Dynamics Theory (GDT)25,28 emphasize the importance of positive interactions between group members to promote relatedness (feeling valued and included), reciprocal support (providing and receiving support), and group cohesion (the dynamic process arising from shared goal-pursuit). Thus, in the present trial, we define social affiliation as a multi-faceted construct with four related but distinct components: collective efficacy, relatedness, reciprocal support, and group cohesion.

Social affiliation may be especially important to African American women because collectivism (belief in the importance of advancing the group over the individual)29,30 is a key component of an Afro-Centric worldview.31 As captured in the African proverb, “I am because we are, and therefore, we are because I am,” a collectivist perspective emphasizes the importance of interconnectedness, relationships, and responsibility to the group.31,32 Collectivism is positively associated with central-internalized Black racial identity,33 and strongly related to Black cultural strength.34 While there is considerable variability in racial identity among African Americans,35 collectivism may be especially important for African American women, as this group tends to experience heightened discrimination due to the intersectionality of race, gender, and other social identities.36 Past efforts to understand interpersonal needs among African American women in relation to PA have focused on caregiver responsibilities and the need for social support,6,7 with broader social affiliation needs and a focus on Afro-Centric cultural values being largely overlooked. Despite converging evidence highlighting the importance of social affiliation from a theoretical and cultural perspective, this factor has been minimally integrated into intervention designs and rarely targeted as a central mechanism for increasing PA.37

The TEAM-PA trial targets social affiliation through a combination of innovative collaborative and competitive strategies. Past research has demonstrated the usefulness of individual-based behavioral skills training (e.g., goal-setting, self-monitoring) for promoting PA.38,39 Expanding upon our pilot work,40–42 in the present trial we propose that group-based behavioral skills, where groups pursue a shared weekly PA goal, receive feedback, and problem-solve with input from peers, may be more effective for promoting social affiliation and enhancing PA. The TEAM-PA trial also integrates a novel focus on intragroup competition. While individual-based competition may undermine motivation,43 intragroup competition (or competing within groups to achieve a common goal) promotes numerous positive group outcomes, including enhanced performance and group cohesion.44–47 Past community-based PA interventions with African American women have primarily focused on non-competitive approaches to delivering PA sessions (e.g., group walking).17,48,49 Thus, we propose that intragroup competition has been overlooked as an important approach for enhancing key aspects of social affiliation and promoting PA among African American women.

1.2. Objectives and Hypotheses

The objective of the TEAM-PA trial is to evaluate the efficacy of a group-based social affiliation intervention (vs. a standard group-delivered PA program) for increasing total PA among African American women who are insufficiently active. All components of the TEAM-PA intervention aim to facilitate a group context that supports social affiliation and is guided by a theoretical framework expanding upon SDT,24 SCT,27,50 GDT,25,28 and a focus on collectivism. The TEAM-PA intervention focuses on four components of social affiliation (collective efficacy, relatedness, group cohesion, reciprocal support) as the primary mechanistic pathway for increasing total PA. Individual-level processes are assessed as a secondary pathway (self-efficacy, self-regulation, autonomous motivation). Thus, the specific aims of the trial are:

To test the efficacy of the group-based social affiliation intervention (vs. a comparison program) on increasing total PA. It is hypothesized that participants in the intervention (vs. a comparison program) will show greater improvements in daily minutes of total PA (primary outcome), walking speed, percentage achieving ≥ 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous PA/week, light PA, and sedentary behavior (secondary outcomes) from baseline to post-intervention and the maintenance of these effects at 6 months.

To test the efficacy of the intervention vs. comparison on improving cardio-metabolic risk factors, including improvements in body mass index, blood pressure, and waist circumference (secondary outcomes) from baseline to post- and 6 months.

To test whether improvements in social affiliation (collective efficacy, relatedness, group cohesion, reciprocal support) vs. individual-level factors (self-efficacy, self-regulation, autonomous motivation), mediate the effects of the TEAM-PA intervention on changes in PA outcomes.

2. Study Design and Recruitment Approach

The TEAM-PA trial will be implemented over 5-years (2022–2026) and uses a randomized group cohort design with three timepoints: baseline, post-intervention, and 6 months post-intervention. Each cohort will include 3–4 groups, with 10–15 participants per group, and a total of 30 groups across the trial. Participants are recruited in collaboration with local community partners and organizations, who assist with distributing flyers and invitations to attend local community events (e.g., health fairs, family nights, church events). Within these community organizations, we have identified community sites (e.g., recreation centers) serving neighborhoods with a high percentage of African American residents (≥ 70%) to maximize the feasibility of recruiting African American women. To reduce contamination bias, only one group is delivered at a time at each community site, delivery of the next group is delayed by ≥ 3 months, and community sites are spaced by ≥ 15 miles.

Eligibility criteria include 1) ≥ 18 years old; 2) self-identifying as an African American or Black female; and 3) engaging in < 60 minutes of self-reported MVPA per week for the last three months. Exclusion criteria include 1) having a cardiovascular or orthopedic condition that would limit PA; 2) inability to walk without a walker/cane; 3) pregnancy; or 4) uncontrolled blood pressure (systolic >180 mmHg/diastolic >110 mmHg). Individuals interested in participating complete a phone screener, including the short-version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire51 and the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (2022 Version).52 Individuals reporting a history of cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, orthopedic issues, or other conditions that would limit PA require medical approval from their primary care provider. Additionally, all medical screeners are reviewed internally by a Co-Investigator on the research team with a Doctorate in Nursing Practice and who is a Family Nurse Practitioner.

Eligible participants then complete a group orientation session to receive additional information, complete a blood pressure assessment, and provide informed consent. We implement strategies during the group orientations known to improve attendance and retention, including setting clear expectations and explaining the study rationale without scientific jargon.53 Participants then complete a 2-week run-in period prior to randomization to assess commitment to the study and to collect baseline measures. Participants must attend at least one run-in session to be included in the group randomization. After completing a run-in period, groups are randomized by our statistician to the intervention or comparison program using a computer-generated randomized algorithm. After randomization, both the intervention and comparison programs involve weekly 2-hour group sessions for 10 weeks implemented at community sites. It is anticipated that 360 participants will be randomized which allows for a 25% attrition rate to maintain a final sample of 270.

3. Integration of Theories in the TEAM-PA Trial

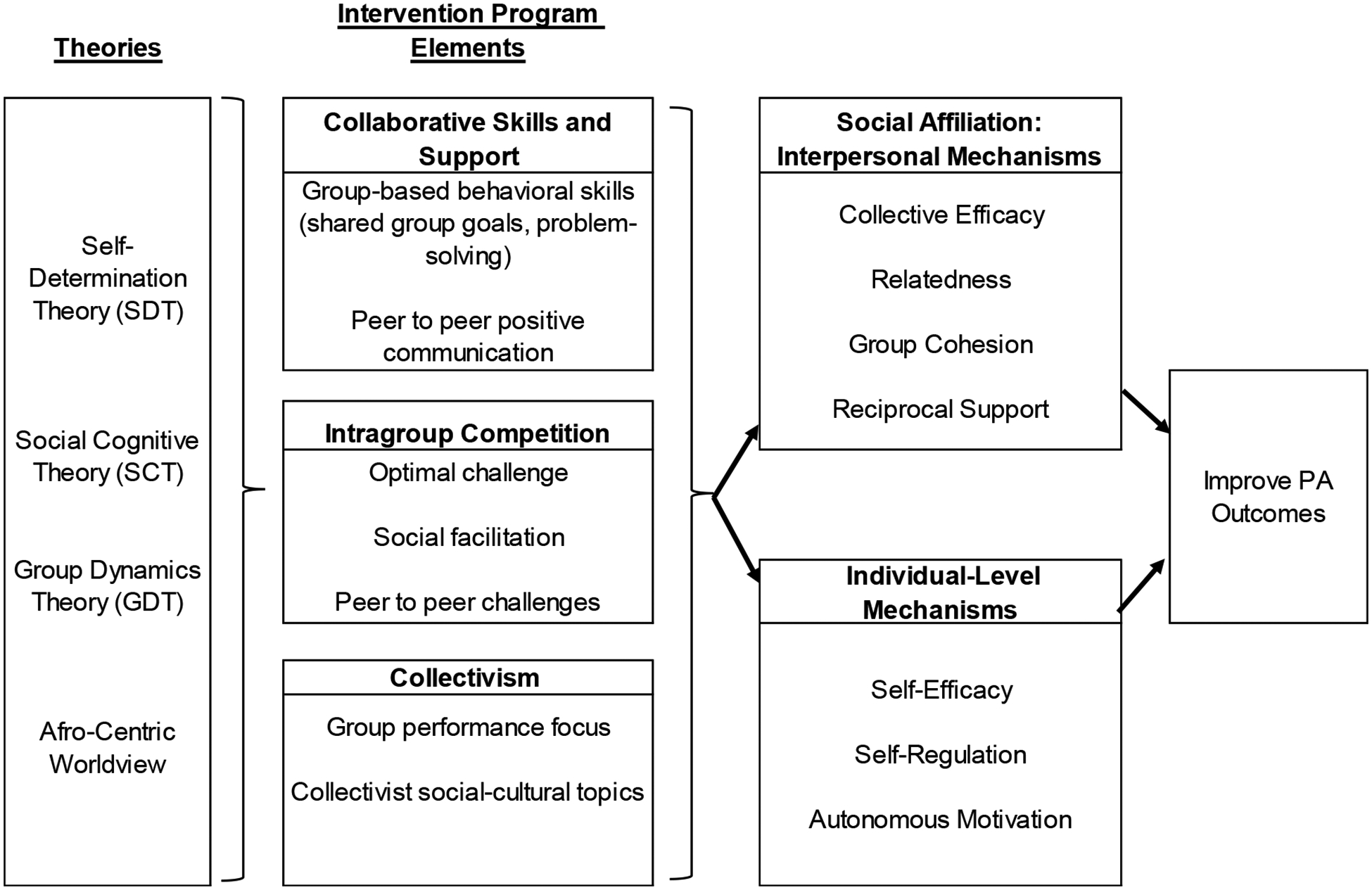

The TEAM-PA intervention aims to promote a positive group climate and is based on essential elements derived from SCT,27,50 SDT,24 GDT,25,28 and a focus on collectivism (see Table 1 and Figure 1). Drawing from SCT, group-based behavioral skills (e.g., group feedback and shared goal-setting) provide opportunities for observational learning and developing a sense of collective efficacy, which promotes effort and social cohesion within groups.26,54–56 Furthermore, drawing from GDT25,28 and SDT,24 which emphasizes the importance of positive interactions between group members, a collaborative group-based approach may also promote positive peer-to-peer communication (e.g., sharing ideas, encouragement) and engaging in reciprocal support. Finally, GDT proposes that intragroup competition has a positive impact on motivation and performance because it enhances group cohesion,25,47 while SDT24,57 emphasizes the importance of competition for promoting an optimal challenge (an activity that balances novelty and competency) and enjoyment of PA.

Table 1.

Together Everyone Achieves More Physical Activity (TEAM-PA) intervention theoretical essential elements

| Theory | Essential elements | Description of program elements |

|---|---|---|

| SCT, GDT | Group-based behavioral skills | Participants share anticipated or actual physical activity barriers and brainstorm problem-solving strategies as a group. |

| Participants select a weekly shared group-based PA goal, which they track with their Fitbits. | ||

| SDT, GDT | Peer to peer positive communication | During the group sessions, the facilitators reinforce positive interactions between group members (e.g., sharing ideas, words of encouragement). |

| Participants are encouraged to support each other throughout the week by selecting a “check-in” captain, posting to the private group, or sending messages through the Fitbit mobile app. | ||

| Afro-Centric Worldview | Collectivism | Facilitators emphasize the importance of group performance (e.g., group goals). |

| PA curriculum integrates cultural topics related to collectivism. | ||

| SDT | Optimal Challenge | Participants complete competitive group activities at each session, which balance novelty and competency. |

| SCT, GDT | Social Facilitation | Participants monitor their personal progress and the group’s progress in meeting the weekly physical activity goal through the Fitbit mobile app, and receive prompts from the group facilitators. |

| GDT | Peer to peer challenges | Participants are encouraged to use the leaderboard feature on the Fitbit mobile app to engage in peer-to-peer challenges (to further the group’s overall performance) |

Note. SCT = Social Cognitive Theory; SDT = Self-Determination Theory; GDT = Group

Dynamics Theory

Figure 1.

Theoretical model for the TEAM-PA intervention

Drawing from this multi-theoretical framework, the TEAM-PA intervention targets three major program components: 1) collaborative skills and support, including the use of group-based behavioral skills (shared goal-setting and problem-solving) and peer-to-peer positive communication; 2) friendly intragroup competition (including opportunities for peer-to-peer challenges, social facilitation, and optimal challenge); and 3) a collectivism focus, including emphasizing the group’s PA progress (vs. individuals) and discussion of relevant cultural topics.

3.1.1. TEAM-PA Intervention

The TEAM-PA intervention is delivered by two trained facilitators. After the run-in period, participants receive a Fitbit to track their PA and instructions for using the Fitbit mobile app. Participants are linked as “friends” to other group members on the app and a private group is set up by the research team to facilitate conversations among group members. The intervention group sessions include three core components: a health curriculum, intragroup competitive PA sessions, and group-based behavioral skills.

The health curriculum includes guided group discussions designed to target behavioral skills for promoting PA (e.g., self-monitoring, getting social support) (see Table 2). The intervention curriculum is culturally-adapted to be relevant for African American women, including providing prevalence rates specific to African American women and discussion of social-cultural topics, including hair as a barrier to PA, the role of spirituality, the importance of family, and coping with racial stressors. Importantly, the intervention curriculum also integrates topics related to collectivism, such as serving as a role model, expressing Black Joy, and the importance of neighborhood support. Facilitators use guides for each session, which include session objectives, key content, activities, and open-ended discussion prompts to ensure delivery of theoretical elements. Participants receive handouts that parallel the facilitator guides.

Table 2.

Curriculum matrix for the TEAM-PA intervention, including collectivism-focused cultural topics

| Week and Theme | Content | Behavioral Skills | Collectivism Topic (Intervention Only) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Run-In week 1 |

|

|

|

| 0 Run-In week 2 |

|

|

|

| 1 “Making Lifestyle Changes through Effective Goals” |

|

|

|

| 2 “Exploring Different Ways to Be Active” |

|

|

|

| 3 “Making Time and Getting Support for Being Active” |

|

|

|

| 4 “Being Active at Home and in Your Neighborhood” |

|

|

|

| 5 “Building a Healthy Plate to Stay Active” |

|

|

|

| 6 “Feeling Strong Inside and Out” |

|

|

|

| 7 “Managing Stress” |

|

|

|

| 8 “Creating Healthy Lifestyles Together” |

|

|

|

| 9 “Promoting a Lifetime of Health” |

|

|

|

| 10 “Staying Motivated” |

|

|

|

After the health curriculum, participants complete 30 minutes of PA, including a warm-up, a competitive group activity, and a cooldown, which is implemented by the trained facilitators. For the competitive activities, groups are divided into small teams for relay-based games, calisthenics challenges, or team-based chair exercise challenges, adapted from previous studies.58,59 These activities are informed by GDT, which proposes that providing participants with opportunities to engage in group competition is important for promoting group cohesion.

Each week participants collaboratively decide upon a shared group-based PA goal, which they track with their Fitbits. The facilitators provide guidance to promote a goal that is specific, measurable, attainable, and realistic for all group members. Fitabase (Small Steps Labs LLC) is used to compile participants’ weekly Fitbit data and provide feedback about the group’s overall performance. To further enhance group cohesion, the total distance covered by the group is converted to miles, and participants are provided with a map to see how far the group has “traveled” each week. Drawing from motivational interviewing techniques,60 facilitators use open-ended prompts to facilitate group-based behavioral skills training, including identifying strengths, areas for improvement, sources of support, anticipated barriers, and brainstorming solutions. Facilitators reinforce reciprocal support by encouraging peer input and positive communication between group members.

Outside of the weekly sessions, participants use the Fitbit mobile app to facilitate meeting the weekly group-based PA goal. The group selects a weekly “check-in” captain who is responsible for supporting their group members on the FitBit mobiles app. By working as part of a group within a positive group climate and making one’s performance visible to others, this approach is intended to promote social facilitation.61,62 The app also includes a leaderboard, which automatically ranks one’s performance in relation to their peers. In our pilot work,42 we found that participants enjoyed using this feature to engage in friendly peer-to-peer competition.

3.1.2. Standard Group-Based PA Comparison Program

The comparison program includes a health curriculum, a walking program, and individual-based goal-setting (and no collaborative skills and support strategies, competitive program elements, or collectivism topics). Participants receive a similar culturally-adapted health curriculum, but the cultural topics related to collectivism are omitted. In place of competitive group activities, the PA session involves group walking, including a warm-up, self-paced walking, and a cool-down. Instead of group-based goals, participants meet individually with a facilitator for individual-based goal-setting. Facilitators guide participants in setting a weekly PA goal, including specifying days/amounts/frequencies. Participants receive Fitbits to track their individual PA goals but are not connected with their group members on the app. During the group sessions, participants share their progress with their group members and facilitators use motivational interviewing skills to help participants identify strengths, areas for improvement, and brainstorm solutions. However, the emphasis is on individual (rather than group) progress and peer-to-peer support and positive communication are not reinforced.

3.1.3. Post-Program Follow-Up

After completing the 10-week intervention, participants are encouraged to continue to use the Fitbit mobile app to connect with their group members. Across the 6-month follow-up period, at the start of each month the research team posts in the group’s private Fitbit group, including a check-in about current goals, tracking with the Fitbit, and a group activity. These activities target and reinforce behavioral skills and topics covered during the intervention program and social connectedness. Alternatively in the comparison program to provide an equivalent contact control, participants receive monthly text messages with links to health education articles across the 6-month period.

3.1.4. Facilitator Training

African American female facilitators are trained to co-deliver the programs. All facilitators undergo extensive training, including behavioral skills related to PA through didactic and role-play components. Training targets motivational interviewing skills (e.g., reflective listening, descriptive praise, “push” vs “pull” language), techniques for promoting a positive social environment, how to target key behavioral skills in group sessions, CPR/first aid, and cultural competency approaches. The facilitators are co-trained by the PI and two of the Co-Investigators with expertise in intervention implementation, health promotion, cultural competency, and cultural tailoring for African American communities (PhDs in Health Psychology and Community Psychology).

4. Process Evaluation

Process evaluation, which measures the extent to which an intervention is delivered as planned, will be used to evaluate dose, fidelity, and reach.63 Constructs from SDT, SCT, and GDT were integrated with research on collectivism to inform the identification of program essential elements (see Table 1). These essential elements were used to inform acceptable levels of delivery and fidelity. Adapted from a previous community-based trial,64 the process evaluation approach is multi-level, such that both facilitators and group members are observed to allow for a more complete understanding of how program implementation impacts outcomes.

Trained process evaluation staff observe the group sessions and collect systematic observational data. Process evaluation staff complete the same training as the facilitators and quality control checks are conducted at the beginning of each cohort to confirm that the systematic observations are completed correctly and with adequate inter-rater reliability. Process evaluation is used for formative (to provide ongoing feedback to facilitators) and summative purposes (to monitor dose and fidelity). The a priori goal for dose is for each program component to be delivered ≥ 75% of the time and the a priori goal for fidelity is to average ≥ 3 at both the facilitator and group levels (4-point scale, 1 = none, 2 = some, 3 = most, 4 = all).

To evaluate reach, attendance for the weekly group sessions is calculated using the average proportion of participants in attendance each week, with an a priori goal of ≥ 75% in attendance each session. If participants miss a group session, makeup sessions are offered by phone and attendance rates are calculated with and without makeups. Outside of the group sessions, both programs are monitored for adherence to wearing the FitBit (defined as the number of days with > 0 steps) and adherence to the social components (e.g., use of the social features in the TEAM-PA program and not in the comparison program).

5. Data Analyses of Primary Outcomes

The primary aims of this study are to assess the treatment effect of the intervention (vs. comparison program) on increasing daily minutes of total PA from baseline to post-intervention (10 weeks) and maintenance at 6-months post-intervention (see Table 3 for the primary and secondary outcomes). To account for the clustering of participants within groups, mixed models will be used where group will be included as a random effect. In mixed notation, the model assessing treatment effects is:

Table 3.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes in the TEAM-PA trial

| Measure | Description | Data Collection |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | ||

| Minutes of Daily Total PA | Wrist-worn ActiGraph accelerometers (wGT3X-BT) record PA in 1-minute epochs to capture raw activity data, which are covered into total minutes of PA per day using threshold developed by Hildebrand and colleagues.65,66 | 7 days of wear at baseline, post-intervention and 6-month follow-up. |

| Secondary | ||

| Minutes of Daily Light PA | Light PA is calculated from the ActiGraph accelerometers | 7 days of wear at baseline, post-intervention and 6-month follow-up. |

| Minutes of Daily Sedentary Behavior | Sedentary Behavior is calculated from the ActiGraph accelerometers | 7 days of wear at baseline, post-intervention and 6-month follow-up. |

| % of Participants with ≥ 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA)/week | MVPA is calculated from the accelerometers to determine the % of participants meeting national guidelines for aerobic PA (≥ 150 minutes/week) | 7 days of wear at baseline, post-intervention and 6-month follow-up. |

| Body Mass Index | Calculated from height (measured to 0.1 cm with a stadiometer and weight (measured to 0.1 kg with a SECA digital scale). | Baseline, post-intervention, 6-month follow-up |

| Blood Pressure | Diastolic and systolic blood pressure are measured using an automatic blood pressure machine (Omron HEM-907XL) | Enrollment, post-intervention, 6-month follow-up |

| Waist Circumference | Measured to 0.1 cm using the natural waist protocol/flexible measuring tape | Baseline, post-intervention, 6-month follow-up |

| Walking Speed | The 2-minute walking test is used to calculate total distance covered in 2 minutes (feet and inches) | Baseline, post-intervention, 6-month follow-up |

| Other Pre-Specified / Mediators | ||

| Social Affiliation Factors | Reciprocal Social Support for Physical Activity, Group Cohesion, Group Interactions, Collective Efficacy, and Relatedness, measured with a self-report survey | Baseline, mid-point, post-intervention, 6-month follow-up |

| Individual-Level Factors | Self-Efficacy for PA, Self-Regulation for PA, and Autonomous Motivation for PA, measured with a self-report survey | Baseline, post-intervention, 6-month follow-up |

where PAtij is the value of PA at time t (t=1,…,21; 1–7 are baseline days, 8–14 are post-intervention days, and 15–21 are 6-month follow-up days) for individual i in treatment group j (j=1,2), indexes t, i, j are implied for all covariates. Post is an indicator variable signaling whether an observation was collected post-intervention. Aim 1 is assessed by the Wald test of the null hypothesis H0: B110 = 0, which assesses the interaction between treatment (TX) and Post, and the Wald test of the null hypothesis H0: B210 = 0 for B210(TX * 6Months) assesses whether the treatment effect is maintained at 6 months. Covariates is a row-vector of covariates which includes individual, seasonal, and community level predictors and B020 is the associated column-vector of concomitant regression parameters. Covariates may include: age, income, education, marital status, season, weather, day of accelerometry wear (weekday vs weekend), and community site. The model specification includes random effects for each group, u00j for j=1 and j=2, and an indicator for whether the observation was collected after baseline (Follow-up), which results in unbiased standard errors. The Wald test of H0: B110 = 0 will be carried out using a test statistic based on a standard error from the modified sandwich variance estimator ensuring robust inference for any within group correlation structure.

5.1. Secondary Aims

The model from Aim 1 will be modified to determine the effects of the intervention on the secondary outcomes. To address Aim 3, we will evaluate whether improvements in social affiliation vs. individual-level factors mediate the effects of the intervention on changes in outcomes. Given that the intervention is designed to enhance social affiliation, we expect larger between-group differences for the social affiliation variables than the individual-level factors. We will explore mediation effects in a multiple mediator model that specifies a clustering variable to appropriately identify grouped observations so that appropriately adjusted standard errors are computed for all model estimates. Additionally, we will investigate component parts of the mediation chain to illuminate the relationship between treatment condition and changes in outcomes, investigating both action theory (i.e., how the intervention affects social affiliation and individual-level factors) and conceptual theory (i.e., how the social affiliation and individual-level factors relate to PA).67 The mediation model will be estimated using a simulation-based potential outcomes framework to decompose exposure effects into natural direct and natural indirect effect components.68 Associated confidence intervals will be used to assess statistical inference of all effects in the model, and effect size estimates will be reported.

5.2. Accelerometry Information and Data Processing

Accelerometers will be worn for 7 days at each timepoint. Accelerometry data will be downloaded with ActiLife software and saved in a raw format containing acceleration data. These files will then be summarized in R with the GGIR69 package using the Euclidean Norm Minus One metric and no imputation.70 We plan to adapt thresholds for PA intensities developed by Hildebrand and colleagues.65,66 These values may be updated if new recommendations are published before the end of this trial.

5.3. Missing Data

To address missing accelerometry data, we will use a weighted mixed model approach with variance weighting by the inverse of daily wear time proportions. This approach results in participants with a higher proportion of missing wear time being down weighted compared to those with less missingness and has been shown to improve precision in estimating accelerometry-estimated PA.71 Importantly, accelerometry wear criterion rules can vary widely across studies, which can introduce bias.72 One advantage of the variance weighting approach is that rather than adhering to a strict wear-time rule, it allows one to retain more data in the final model, as cases with a large amount of missingness will be down-weighted and will have a relatively small impact on the model, compared to cases with more complete data.

To address other missing data (e.g., survey and secondary outcomes) we will use Multiple Imputation. Multiple Imputation provides an unbiased estimate of parameters and standard errors and is appropriate for longitudinal trials.73 We anticipate using the MICE package in R to impute the data, which allows for the specification of a class variable (group) and the inclusion of a random effect in each of the imputation models. However, other imputation methods may be updated if new recommendations are published prior to the end of this trial. All demographic data, primary and secondary outcomes, and variables of theoretical importance will be included in the imputation to minimize the likelihood of biased estimates. This process will be used to compute 20 complete datasets and results across datasets will be combined using Rubin’s method.74

5.4. Power

The present study aims to detect at least a 10-minute difference in total PA between the intervention and comparison programs, which is based in part on previous studies finding that group-based interventions targeting group cohesion were more effective than a standard group-delivered exercise program (Cohen’s d = 0.74).75 Assuming an attrition rate of 25%, we propose that randomizing 360 participants across 30 groups and retaining a final sample of 270 participants will provide adequate power (80%) to detect a meaningful difference of at least 10 minutes/day of total PA or 0.53 to 0.57 standard deviation units. This calculation assumes a SD of 75, alpha = 0.05, an ICC of 0.20, and a small to moderate correlation between baseline and post-intervention total PA (r = 0.4). For the secondary outcomes, we are powered to detect an equivalent standardized effect of 0.50. Power analysis for the mediational analyses indicates that we will have 80% power to detect a standardized effect of 0.67.

6. Implications

Our research team has conducted several preliminary studies testing the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary impact of targeting different components of social affiliation through a community-based PA program for African American women.41,42 This efficacy trial will allow us to evaluate the impact of this treatment approach on a larger scale across different community sites using objective measures of PA and a 6-month follow-up, which are key methodological components that have been lacking in past PA interventions for African American women.15,16 This trial will provide important and novel information about the importance of addressing collectivism within health promotion programs and which aspects of social affiliation are most important for promoting changes in PA among African American women.

Acknowledgements.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under award number R01HL160618 (Sweeney, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We also thank our community partners, including City of Columbia Parks and Recreation, City of Sumter HOPE Centers, and Boys and Girls Club of the Midlands.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interests.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships what could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Trial Registration: This study was registered on Clinicaltrials.gov (# NCT05519696) in August 2022 prior to initial participant enrollment.

Contributor Information

Allison M. Sweeney, Department of Biobehavioral Health and Nursing Science, College of Nursing, University of South Carolina, 1601 Greene Street, Columbia, SC, 29201.

Dawn K. Wilson, Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

Nicole Zarrett, Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

Pamela Martin, Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

James W. Hardin, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

Amanda Fairchild, Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

Sheryl Mitchell, Department of Advanced Professional Nursing Practice and Leadership, College of Nursing, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

Lindsay Decker, Department of Biobehavioral Health and Nursing Science, College of Nursing, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

References

- 1.Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Eke PI, Giles WH. Vital Signs: Racial Disparities in Age-Specific Mortality Among Blacks or African Americans — United States, 1999–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(17):444–456. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth GA, Johnson CO, Abate KH, et al. The burden of cardiovascular diseases among us states, 1990–2016. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(5):375–389. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Vol 145.; 2022. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee I-M, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Impact of Physical Inactivity on the World’s Major Non-Communicable Diseases. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheehy S, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Leisure Time Physical Activity in Relation to Mortality Among African American Women. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59:704–713. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joseph RP, Ainsworth BE, Keller C, Dodgson JE. Barriers to Physical Activity Among African American Women: An Integrative Review of the Literature. Women Health. 2015;55:679–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siddiqi Z, Tiro JA, Shuval K. Understanding impediments and enablers to physical activity among African American adults: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(6):1010–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathew Joseph N, Ramaswamy P, Wang J. Cultural factors associated with physical activity among U.S. adults: An integrative review. Appl Nurs Res. 2018;42(May):98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2018.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, F Loos RJ, Martin BW. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet. 2012;380:258–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benjamin EJ, Salim Virani CS, Chair Clifton Callaway C-VW, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:67–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bherer L, Erickson KI, Liu-Ambrose T. A Review of the Effects of Physical Activity and Exercise on Cognitive and Brain Functions in Older Adults. J Aging Res. 2013;2013. http://dx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee Y, Park K. Health Practices That Predict Recovery from Functional Limitations in Older Adults. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sjösten N, Kivelä S-L. The effects of physical exercise on depressive symptoms among the aged: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(5):410–418. doi: 10.1002/gps.1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otado J, Kwagyan J, Edwards D, Ukaegbu A, Rockcliffe F, Osafo N. Culturally Competent Strategies for Recruitment and Retention of African American Populations into Clinical Trials. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8(5):460–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coughlin SS, Smith SA. A review of community-based participatory research studies to promote physical activity among African Americans. J Georg Public Heal Assoc. 2016;5(3):220–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jenkins F, Jenkins C, Gregoski MJ, Magwood GS. Interventions Promoting Physical Activity in African American Women: An Integrative Review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;32(1):22–29. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bland V, Sharma M. Physical activity interventions in African American women: A systematic review. Heal Promot Perspect. 2017;7(2):52–59. doi: 10.15171/hpp.2017.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chastin SFM, De Craemer M, De Cocker K, et al. How does light-intensity physical activity associate with adult cardiometabolic health and mortality? Systematic review with meta-analysis of experimental and observational studies. Br J Sport Med. 2019;53:370–376. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekelund U, Tarp J, Steene-Johannessen J, et al. Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all cause mortality: Systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varma VR, Tan EJ, Wang T, et al. Low-intensity walking activity is associated with better health. J Appl Gerontol. 2014;33(7):870–887. doi: 10.1177/0733464813512896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. Psycholoigical Bull. 1995;117(3):497–529. doi: 10.4324/9781351153683-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Begen FM, Turner-Cobb JM. The need to belong and symptoms of acute physical health in early adolescence. J Health Psychol. 2012;17(6):907–916. doi: 10.1177/1359105311431176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim KA, Chu SH, Oh EG, Shin SJ, Jeon JY, Lee YJ. Autonomy is not but competence and relatedness are associated with physical activity among colorectal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. August 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05661-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Estabrooks PA, Harden SM, Burke SM. Group dynamics in physical activity promotion: What works? Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2012;6(1):18–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00409.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2000;9(3):75. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura A Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. New York, NY: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carron AV, Shapcott KM, Burke SM. Group dynamics in exercise and sport psychology. In: Group Cohesion in Sport and Exercise: Past, Present and Future. Routledge; 2007:135–158. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nobles W African philosophy: foundations for black psychology. In: Jones R, ed. Black Psychology. Berkeley, CA: Cobb & Henry Publishers; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boykin AW, Jagers RJ, Ellison CM, Albury A. Communalism: Conceptualization and measurement of an Afrocultural social orientation. J Black Stud. 1997;27(3):409–418. doi: 10.1177/002193479702700308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belgrave FZ, Allison KW. African American Psychology: From Africa to America. SAGE Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carson LR. “I am because we are:” Collectivism as a foundational characteristic of African American college student identity and academic achievement. Soc Psychol Educ. 2009;12(3):327–344. doi: 10.1007/s11218-009-9090-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown CL, Love KM, Tyler KM, Garriot PO, Thomas D, Roan-Belle C. Parental attachment, family communalism, and racial identity among African American college students. J Multicult Couns Devel. 2013;41(2):108–122. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1912.2013.00031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson VE, Carter RT. Black Cultural Strengths and Psychosocial Well-Being: An Empirical Analysis With Black American Adults. J Black Psychol. 2020;46(1):55–89. doi: 10.1177/0095798419889752 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Resnicow Davis R, Zhang N, Strecher V, Tolsma D, Calvi J, … & Cross WEK Jr Tailoring a fruit and vegetable intervention on ethnic identity: results of a randomized study. Heal Psychol. 2009;28:394–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis TT, Van Dyke ME. Discrimination and the Health of African Americans: The Potential Importance of Intersectionalities. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2018;27(3):176–182. doi: 10.1177/0963721418770442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gillison FB, Rouse P, Standage M, Sebire SJ, Ryan RM. A meta-analysis of techniques to promote motivation for health behaviour change from a self-determination theory perspective. Health Psychol Rev. 2019;13(1):110–130. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2018.1534071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, McAteer J, Gupta S. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2009;28(6):690–701. doi: 10.1037/a0016136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olander EK, Fletcher H, Williams S, Atkinson L, Turner A, French DP. What are the most effective techniques in changing obese individuals’ physical activity self-efficacy and behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sweeney AM, Wilson DK, Brown A. A qualitative study to examine how differences in motivation can inform the development of targeted physical activity interventions for African American women. Eval Program Plann. 2019;77. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2019.101718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sweeney AM, Wilson DK, Zarrett N, Van Horn ML, Resnicow K. The Feasibility and Acceptability of the Developing Real Incentives and Volition for Exercise (DRIVE) Program: A Pilot Study for Promoting Physical Activity in African American Women. Health Promot Pract. 2021;22:840–849. doi: 10.1177/1524839920939572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sweeney A, Wilson DK, Van Horn ML, et al. Results from “Developing Real Incentives and Volition for Exercise”(DRIVE): A pilot randomized controlled trial for promoting physical activity in African American women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2022;90:747–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deci E, Betley G, Kahle J, Abrams L, Porac J. When trying to win: Competition and intrinsic motivation. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 1981;7:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tauer JM, Harackiewicz JM. The effects of cooperation and competition on intrinsic motivation and performance. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;86:849–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reeve J, Deci E. Elements of the competitive situation that affect intrinsic motivation. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 1996;22:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wittchen M, Krimmel A, Kohler M, Hertel G. The two sides of competition: Competition-induced effort and affect during intergroup versus interindividual competition. Br J Psychol. 2013;104(3):320–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harden SM, Estabrooks PA, Mama SK, Lee RE. Longitudinal analysis of minority women’s perceptions of cohesion: The role of cooperation, communication, and competition. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):57. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peterson JA, Cheng A-L. Heart and Soul Physical Activity Program for African American Women. West J Nurs Res. 2011;33(5):652–670. doi: 10.1177/0193945910383706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young D, Stewart K. A Church-based Physical Activity Intervention for African American Women. Fam Community Health. 2006;29:103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bandura A Health Promotion by Social Cognitive Means. Heal Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjorstrom M, et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Medicine NA of S. National Academy of Sports Medicine: Valuable Information and Resources. https://www.nasm.org/resources/downloads. Published 2019.

- 53.Jake-Schoffman DE, Brown SD, Baiocchi M, et al. Methods-Motivational Interviewing Approach for Enhanced Retention and Attendance. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(4):606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goddard RD, Hoy WK, Hoy AW. Collective Efficacy Beliefs:Theoretical Developments, Empirical Evidence, and Future Directions. Educ Res. 2004;33(3):3–13. doi: 10.3102/0013189X033003003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy. Science (80- ). 1997;277(5328):918–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fransen K, Vanbeselaere N, Exadaktylos V, et al. “Yes, we can!”: Perceptions of collective efficacy sources in volleyball. J Sports Sci. 2012;30(7):641–649. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2011.653579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ryan R, Williams G, Patrick H, Deci E. Self-determination theory and physical activity: The dynamics of motivation in development and wellness. Hell J Psychol. 2009;6:107–124. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson DK, Van Horn ML, Kitzman-Ulrich H, et al. Results of the” Active by Choice Today”(ACT) Randomized Trial for Increasing Physical Activity in Low-Income and Minority Adolescents. Heal Psychol. 2011;30(4):463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zarrett N, Wilson DK, Sweeney A, et al. An overview of the Connect through PLAY trial to increase physical activity in underserved adolescents. Contemp Clin Trials. 2022;114:106677. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2022.106677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Resnicow K, Gobat N, Naar S. Intensifying and igniting change talk in Motivational Interviewing: A theoretical and practical framework. Eur Heal Psychol. 2015;17(3):102–110. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Snyder AL, Anderson-Hanley C, Arciero PJ. Virtual and Live Social Facilitation While Exergaming: Competitiveness moderates exercise intensity. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2012;34(2):252–259. doi: 10.1123/jsep.34.2.252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zajonc RB. Social Facilitation. Science (80-). 1965;149(3681):269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilson DK, Sweeney AM, Van Horn ML, et al. The Results of the Families Improving Together (FIT) for Weight Loss Randomized Trial in Overweight African American Adolescents. Ann Behav Med. 2022;56:1042–1055. doi: 10.1093/abm/kaab110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hildebrand M, Van Hees VT, Hansen BH, Ekelund U. Age group comparability of raw accelerometer output from wrist-and hip-worn monitors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(9):1816–1824. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hildebrand M, Hansen BH, van Hees VT, Ekelund U. Evaluation of raw acceleration sedentary thresholds in children and adults. Scand J Med Sci Sport. 2017;27(12):1814–1823. doi: 10.1111/sms.12795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fairchild AJ, MacKinnon DP. Using mediation and moderation analyses to enhance prevention research. In: Defining Prevention Science. Springer US; 2014:537–555. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-7424-2_23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A General Approach to Causal Mediation Analysis. 2010. doi: 10.1037/a0020761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Migueles JH, Rowlands AV., Huber F, Sabia S, van Hees VT. GGIR: A Research Community–Driven Open Source R Package for Generating Physical Activity and Sleep Outcomes From Multi-Day Raw Accelerometer Data. J Meas Phys Behav. 2019;2(3):188–196. doi: 10.1123/jmpb.2018-0063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Hees VT, Gorzelniak L, Dean León EC, et al. Separating Movement and Gravity Components in an Acceleration Signal and Implications for the Assessment of Human Daily Physical Activity. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yue Xu S, Nelson S, Kerr J, et al. Statistical approaches to account for missing values in accelerometer data: Applications to modeling physical activity. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27(4):1168–1186. doi: 10.1177/0962280216657119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Herrmann SD, Barreira TV., Kang M, Ainsworth BE. How many hours are enough? Accelerometer wear time may provide bias in daily activity estimates. J Phys Act Heal. 2013;10(5):742–749. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.5.742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Enders CK. Analyzing longitudinal data with missing values. Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56(4):267–288. doi: 10.1037/a0025579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation after 18+ Years. J Am Stat Assoc. 1996;91(434):473–489. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1996.10476908 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Burke SM, Carron AV., Eys MA, Ntoumanis N, Estabrooks PA. Group versus individual approach? A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity. Sport Exerc Psychol Rev. 2006;2:19–35. [Google Scholar]