Abstract

Aim:

Socio-economic deprivation encompasses the relative disadvantage experienced by individuals or communities in relation to financial, material or social resources. Nature-based interventions (NBIs) are a public health approach that promote sustainable, healthy communities through engagement with nature and show potential to address inequalities experienced by socio-economically deprived communities. This narrative review aims to identify and evaluate the benefits of NBIs in socio-economically deprived communities.

Method:

A systematic literature search of six electronic publication databases (APA PsycInfo, CENTRAL, CDSR, CINAHL, Medline and Web of Science) was conducted on 5 February 2021 and repeated on 30 August 2022. In total, 3852 records were identified and 18 experimental studies (published between 2015 and 2022) were included in this review.

Results:

Interventions including therapeutic horticulture, care farming, green exercise and wilderness arts and craft were evaluated in the literature. Key benefits were observed for cost savings, diet diversity, food security, anthropometric outcomes, mental health outcomes, nature visits, physical activity and physical health. Age, gender, ethnicity, level of engagement and perception of environment safety influenced the effectiveness of the interventions.

Conclusion:

Results demonstrate there are clear benefits of NBIs on economic, environmental, health and social outcomes. Further research including qualitative analyses, more stringent experimental designs and use of standardised outcome measures is recommended.

Keywords: nature-based intervention, NBI, socio-economic deprivation, low income, public health, socioeconomic deprivation

Introduction

Socio-economic deprivation within and between countries, and how to address this, is a global issue. 1 Socio-economic deprivation encompasses the relative disadvantage experienced by individuals or communities in relation to financial, material or social resources and opportunities. 2 Globally 1.3 billion people are estimated to be multidimensionally poor. 3 Such individuals are at greater risk of increased mortality, 4 chronic disease, 5 disparities in food consumption 6 and overall compromised mental and physical health.7,8 Within the current context of the global COVID-19 pandemic, there is evidence to suggest that individuals from socio-economically deprived communities have been disproportionately affected.9,10 A range of public health interventions are needed to address these profuse inequalities.11,12

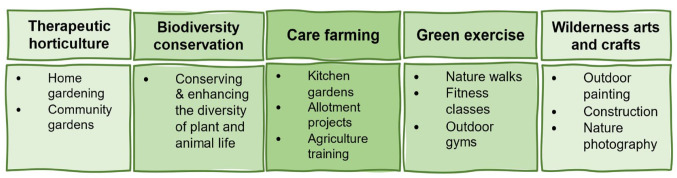

One public health approach is the introduction of nature-based interventions (NBIs) that aim to promote sustainable and healthy communities through engagement with nature and the outdoor environment.13–15 NBIs include a wide range of activities that can be broadly grouped into five categories as therapeutic horticulture, biodiversity conservation, care farming, green exercise or wilderness arts and crafts (see Figure 1).16,17

Figure 1.

Examples of nature-based interventions (NBIs) based on the studies by Bragg and Leck 16 and Jepson et al. 17 that are included in this narrative review of the benefits of NBIs in socio-economically deprived communities

The co-benefits associated with NBIs have been categorised as health, economic, environment and social outcomes.14,18 Specifically, research has demonstrated the positive impact of NBIs on emotional wellbeing,19,20 physical health,21–23 social connection 24 and substantial health cost savings. 25 These can be understood through a range of theoretical lenses including the stress recovery theory, which posits that being in nature elicits positive emotions leading to reduced stress levels and the attention restoration theory, which proposes that nature-based environments are restorative as they demand less cognitive effort than man-made environments.26,27

While it is evident that engagement with nature provides a broad range of benefits, research suggests that individuals living in socio-economically deprived communities have less access to green space than more affluent neighbourhoods and are more likely to live in an area with poor environmental conditions (including water quality, flood risk, air quality and litter). 28 Barriers to access have been identified and include transport costs, safety fears of visiting risky green spaces and culturally insensitive nature-based programmes. 29 There is evidence to suggest that the positive relationships observed between access to nature and health outcomes may be stronger among individuals from socio-economically deprived communities.30,31 As such, NBIs may play an important role in reducing the inequalities of socio-economic deprivation, particularly when the barriers to access are reduced and when these interventions are embedded within local communities and neighbourhoods.

While this area of research has been identified as a growing field, 32 the current evidence evaluating the benefits of specific NBIs for socio-economically deprived communities is limited. Previous reviews have focused largely on research from higher income countries with limited analysis of the impact of socio-economic deprivation.33,34

Aim of this review

This narrative review 35 aims to identify and evaluate the benefits of NBIs for individuals in socio-economically deprived communities. It is anticipated that the results of this review will be beneficial to a broad range of stakeholders including community members, nature-based organisations, public health, spatial planning and policy makers globally to guide decisions around investment and engagement in NBIs and future research in this field.

Method

A narrative synthesis approach was used to systematically explore the current evidence base. 35 The narrative synthesis design was appropriate for this review as it allowed a heterogeneous body of research that used varied experimental interventions and outcomes to be summarised in a succinct and coherent method. This review aimed to develop a preliminary synthesis of the reviewed literature characteristics and findings to highlight similarities and differences within NBIs and their outcomes. 35

Data sources and search strategy

An initial scoping search guided the development of the search strategy. The PICO framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) 36 was used to operationalise the search concepts and terms related to socio-economic deprivation and NBIs were used in the search (see Table 1). NBI typology was guided by previous research, and included but was not limited to interventions categorised as therapeutic horticulture, biodiversity conservation, care farming, green exercise and wilderness arts and crafts.15–18Table 1 details complete eligibility criteria. Adaptations were made for each database to incorporate relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), Boolean operations and appropriate truncation (see Supplemental material 1).

Table 1.

Search strategy used in the narrative review of the benefits of nature-based interventions in socio-economically deprived communities: concepts, search terms and screening eligibility criteria based on the PICO framework 36 .

| PICO | Concept | Search terms | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Individuals living in socio-economically deprived communities | ‘Socio-economic deprivation’ OR ‘Socio economic deprivation’ OR SES OR ‘socio economic status’ OR ‘socio-economic status’ OR depriv* OR ‘economic* depriv*’ OR ‘free school meal’ OR disadvantag* OR ‘social housing’ OR ‘poverty’ OR ‘income-poor’ OR ‘income poor’ OR ‘low-income’ OR ‘low income’ OR ‘index of multiple deprivation’ OR IMD | Individuals that resided in socio-economically deprived

communities (both urban and rural) as defined by local

guidelines. Participants of all ages, genders and ethnicities |

Studies in which the intervention was administered in school, hospital or non-community settings as there are previous reviews of research in these fields |

| Intervention | Nature-based interventions | ‘nature-based’ OR ‘nature based’ OR NBI OR ‘nature prescri*’ OR ‘nature play’ OR ‘green prescri*’ OR ‘green space*’ OR greenspace* OR ‘green exercise’ OR ‘green infrastructure’ OR horticultural OR garden* OR allotment* OR outdoor OR ‘natural environment’ OR ‘blue space*’ OR ‘park based’ OR ‘park prescri*’ OR parks OR ‘eco therapy’ OR ‘eco-therapy’ OR ‘wilderness therapy’ OR ‘wilderness-therapy’ OR ‘care-farming’ OR ‘care farming’ OR ‘farm therapy’ OR ‘farm-therapy’ OR ‘forest bathing’ OR ‘forest-bathing’ OR ‘environmental volunteering’ OR ‘wild play’ | Any NBIs, activities or programmes that aimed to engage

people in nature experiences. This included, but was not limited to, the following five categories:16,17 • Therapeutic horticulture • Biodiversity conservation • Care farming • Green exercise • Wilderness arts and crafts Interventions of any frequency or duration. Interventions that are accessible within the local community that an individual resides in |

Interventions that were delivered on an environmental level (i.e. improvements to green space at an organisational level) were excluded if they did not offer direct involvement of an individual, group or community |

| Comparison | Either within-subject comparisons (pre- and post intervention) or between-subject comparisons with control or additional intervention conditions | Studies in which an NBI is compared to either a control or

alternative intervention OR Studies that provide a within-subjects comparison of the intervention |

Studies that were not of experimental design | |

| Outcome | Health, social, economic or environmental benefits | Any measures that evaluate benefits of NBIs on health, economic, environment or social outcomes 14 | Studies which do not report on outcomes for individuals |

PICO: population, intervention, comparison, outcome; NBIs: nature-based interventions.

Initial searches were conducted on 5 February 2021 and repeated on 30 August 2022 in the following databases:

APA PsycInfo;

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR);

Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL);

OVID Medline;

Web of Science.

A search of unpublished and grey literature was also conducted using APA PsycExtra to minimise the potential effects of publication bias. 37 A manual hand search of relevant dissertation theses, previous reviews and government documents was also conducted. The search was not restricted by publication time frame.

Study selection

This review included peer-reviewed, quantitative research of experimental design. Studies that utilised an independent groups design where an NBI was compared to a control condition or alternative intervention were included. In addition, studies that utilised a matched pairs or repeated measures design to evaluate the effect of an NBI on outcome variables were also included. Where studies utilised mixed methods, only the quantitative data were synthesised. Studies that utilised a quantitative, experimental design were included to enable comparisons of NBIs within the literature. Publications were eligible if the research evaluated the effectiveness of a NBI for individuals from socio-economically deprived communities on either health, economic, environmental or social outcomes. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews were excluded. Reference lists of relevant reviews were hand searched 34 and studies that met the inclusion criteria were included. Non-English language studies were excluded. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Table 1.

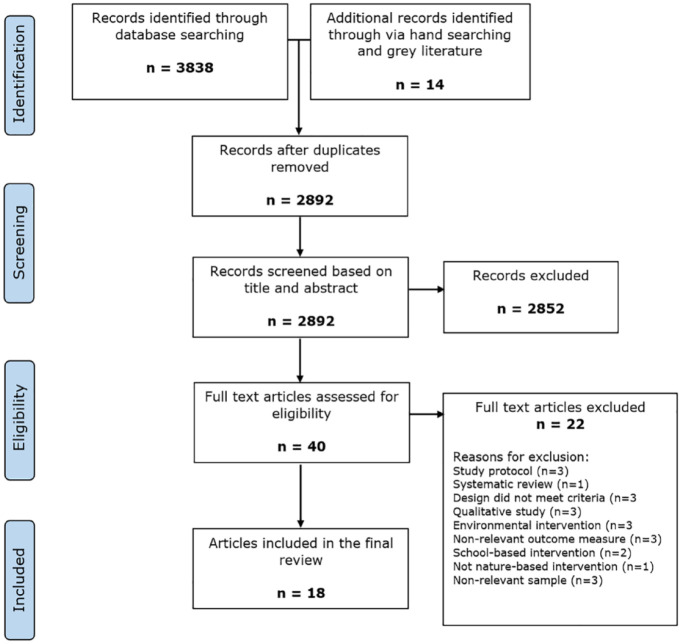

In total, 3838 records were retrieved from the publication database search and 14 identified via hand-searching. All records were transferred to Endnote Software and duplicates were removed (n = 960). The titles and abstracts were screened according to the eligibility criteria, 2852 records were excluded, 40 full-text publications were screened for eligibility. A total of 18 records were eligible for inclusion (see PRISMA diagram in Figure 2). 38

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram, 38 for the narrative review of the benefits of nature-based interventions in socio-economically deprived communities

Data extraction and synthesis

A comprehensive data extraction table was designed to address the aims of this review (see Supplemental material 2). The data were synthesised following a narrative approach. Data were grouped based on intervention and outcome characteristics and presented descriptively in text, diagrams and tables to allow broad comparisons within the literature. 35 A ‘traffic light’ coding system was used to enable an evaluation of the overall effectiveness of NBIs on study outcomes. Studies were coded green if they demonstrated an overall positive effect of the intervention on study outcomes or red if there was no overall positive effect. Studies with mixed results were coded yellow if there were mostly positive effects (on over half of the outcomes assessed) or orange if there were some positive effects (less than half of the assessed outcomes).

The quality of the eligible studies was assessed using the ‘Standard Quality Assessment Criteria’, 39 an appropriate tool for comparing the quality of a studies with differing methodologies and designs. While scoring was guided by a standardised manual, there remained substantial potential subjectivity on the reviewer’s part thus quality appraisal scores were used to enhance the data synthesis process rather than determine the inclusion or exclusion of studies.

Results

Overview of included studies

The 18 publications included in this review were all articles published in peer-reviewed journals between 2015 and 2022.

Study settings

Nine studies (50%) were conducted in the USA, two (11%) in the UK, two (11%) in Ghana and the remaining five in Australia, Bangladesh, France, Peru and Tanzania (see Table 2). The context of the study settings and definitions of socio-economic deprivation varied but included communities where levels of annual income and paid employment were significantly below average and rates of state, government or charitable support were high (see Supplemental material 3).

Table 2.

Narrative review of the benefits of nature-based interventions in socio-economically deprived communities: summary of the setting, participants, intervention, comparison and outcome(s) for the included studies.

| Publication | Setting | Participants | Intervention (category) |

Comparison | Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algert et al. 40 | San Jose, California (USA) |

n = 135 (62% F) Adults Ethnicity a : White (46%); American Indian (20%); Hispanic (12%); Black (5%); Pacific Islander (5%); Other (12%) |

Home gardening (TH) | Between-subjects (community gardening intervention) | Economic Health |

| Baliki et al. 41 | Jessore, Barisal, Faridpur and Patuakhali Districts of Bangladesh |

n = 619 (100%

F) Adults Ethnicity not reported |

Home gardening (TH) | Between-subjects (control condition) | Economic Environmental Health |

| Blakstad et al. 42 | Pwani Region, Tanzania |

n = 874 (100%

F) Adults Ethnicity not reported |

Agriculture training (CF) | Between-subjects (control condition) | Economic Health |

| Booth et al. 43 | Miami-Dade County, Florida (USA) |

n = 66 (40% F) Children (8–14 years) Ethnicity: White Hispanic (57%); Non-Hispanic Black (25%); Black Hispanic (14%); Non-Hispanic White (5%) |

Park-based activity sessions (GE) | Within-subjects | Health |

| Suyin Chalmin-Pui et al. 44 | Greater Manchester, UK |

n = 42 (64%

F) Adults Ethnicity: White (93%); Arab (5%); African/Caribbean/Black (2%) |

Home gardening (TH) | Within-subjects and between-subjects (wait-list control) | Health |

| Cohen et al. 45 | Los Angeles, California (USA) |

n = 1422 (62% F) Adults Ethnicity b : Latino (72%); African American (10%); White (6%) |

Park-based fitness classes (GE) |

Between-subjects (alternative intervention and control conditions) | Environmental Health |

| Dallmann et al. 46 | Upper Manya Krobo District, Ghana |

n = 492 (100%

F) Adults Ethnicity: Krobo (75%); Other (25%) |

Agriculture training (CF) | Between-subjects (control condition) | Health |

| Davies et al. 47 | Wales, UK |

n = 123 (30%

F) Adults Ethnicity not reported |

Sustainable building project (WAC) | Within-subjects | Health Social |

| Grey et al. 48 | Sydney, Australia |

n = 23 (61%

F) Adults Ethnicity not reported |

Community gardening (TH) | Within-subjects | Health Social |

| Grier et al. 49 | Dan River Region, Virginia (USA) |

n = 43 (54% F) Children (5–17 years) Ethnicity: African American (98%); Other (2%) |

Community gardening (TH) | Within-subjects | Environmental Health |

| Han et al. 50 | San Fernando, California (USA) |

n = 187.3

c

(55% F)

c

Adults and children Ethnicity not reported |

Park-based fitness classes (GE) | Within-subjects and between-subjects (control condition) | Environmental Health |

| Kling et al. 51 | Miami-Dade County, Florida (USA) |

n = 380 (85%

F) Adults Ethnicity: Hispanic (45%); Non-Hispanic Black (41%); Non-Hispanic White (5%); Other (9%) |

Park-based fitness classes (GE) | Within-subjects | Health |

| Korn et al. 52 | Lima, Peru |

n = 29 (93%

F) Adults Ethnicity not reported |

Home gardening (TH) | Within-subjects | Health Social |

| Marquis et al. 53 | Upper Manya Krobo District, Ghana |

n = 500 Mother–infant pairs (Infants = 48% F) Ethnicity: Krobo (76%), Other (24%) |

Agriculture training (CF) | Between-subjects (control condition) | Health |

| Martin et al. 54 | Marseille, France |

n = 21 (100%

F) Adults Ethnicity not reported |

Community gardening (TH) | Between-subjects (control condition) | Economic Health |

| Razani et al. 55 | Oakland, California (USA) |

n = 78 (87% F) Parent–child pairs Ethnicity: African American (67%), Latino (15%); Non-Latino White (5%); Other (13%) |

Park prescriptions (GE) | Between-subjects (alternative intervention) | Environmental Health Social |

| South et al. 56 | Philadelphia (USA) |

n = 36 (100%

F) Adults Ethnicity: Black Non-Hispanic (62%), White Non-Hispanic (14%); Asian Non-Hispanic (8%); Hispanic Black (5%); Other (11%) |

Park prescriptions (GE) | Between-subjects (control condition) | Environmental Health |

| Wexler et al. 57 | Minneapolis (USA) |

n = 171 (50%

F) Adults Ethnicity not reported |

Park prescriptions (GE) | Between-subjects (control condition) | Environmental Health |

F: female; TH: therapeutic horticulture; GE: green exercise; CF: care farming; WAC: wilderness arts and crafts.

Where reported.

Survey responses.

Averages calculated through SOPARC methodology (see Table 3).

Study designs

Fifteen of the included studies exclusively reported quantitative data and three utilised a mixed-methods design. Qualitative data were not included in this review. The included studies utilised a range of experimental designs including randomised controlled trials (n = 6, 33%); quasi-experimental studies (n = 4, 22%); repeated-measures designs (n = 4, 22%); non-controlled prospective cohort studies (n = 2, 11%), prospective randomised trials (n = 1, 6%) and non-controlled cross-sectional designs (n = 1, 6%).

Participant characteristics

The total sample sizes ranged from 23 to 1445. Most studies (n = 13, 72%) recruited adults (aged 18 and over) and two (11%) recruited samples of children and young people (aged 18 under). One study (6%) recruited mother and infant pairs and one study (6%) recruited parent–child pairs, although only reported data for the adult sample. One study (6%) reported data for children and adults but utilised an observation style outcome measure, which limited the ability to identify individual participant characteristics.

Most of the reviewed literature included both male and female participants (n = 13, 72%). Five studies (28%) reported data for female-only samples. Almost half of the included publications (n = 8, 44%) did not report the ethnicity of study participants. Where reported, most participants represented African American, Latino, Krobo, Hispanic and White ethnic groups. Table 2 presents an overview of participant characteristics.

Intervention characteristics

The reviewed studies included interventions categorised as therapeutic horticulture (n = 7, 39%); green exercise (n = 7, 39%); care farming (N = 3; 16%) and wilderness arts and crafts (n = 1, 6%; see Table 2). Detail of the specific interventions is provided in Supplemental material 4.

Outcome measures

The included studies evaluated the effects of NBIs on health (n = 18, 100%); environmental (n = 7, 39%); economic (n = 4, 22%) and social outcomes (n = 4, 22%; see Table 3). Health outcomes included assessments of both physical and mental health. Specifically, physical health changes in diet, nutrition, physical activity and anthropometric measures (e.g. body size, form and functional capacities) were evaluated. Mental health outcomes included measures of personal wellbeing, stress, quality of life, resilience and depression. Environmental outcomes included assessments of nature affinity and time spent in nature environments while economic outcomes considered changes in household expenditure, food security and food production. Assessments of social capital, social support, social connectedness and sense of community were included in the social outcomes. A wide variety of measures were used to collect participant data including self-report or researcher administered surveys, physiological or anthropometric measures, global positioning system (GPS) trackers and observational methods (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Narrative review of the benefits of nature-based interventions in socio-economically deprived communities: summary of primary outcome(s) and main findings for the included studies.

| Intervention category | Publication | Primary outcome(s) | Key finding(s) | Overall effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Horticulture | |||||

| Home Gardening | |||||

| Algert et al. 40 | 1. Vegetable intake (food behaviour checklist)

58

2. Cost savings (self-report survey) 40 |

1. No statistical differences in vegetable consumption

between home gardeners and community gardeners when they ate

from their gardens 2. No statistical differences in cost savings per month for community and home gardeners |

|

||

| Baliki et al. 41 | 1. Vegetable production (kg per household member) 2. Nutrient yields (food composition tables) 3. Quantity of vegetables consumed (24 h recall) |

1. Statistically significant increases at 1 and 3 years post

intervention 2. Significant increase in calcium and vitamin C at 1 and 3 years post intervention 3. Statistically significant increase in the share of women selling any vegetable in the market and level of vegetable consumption |

|

||

| Chalmin-Pui et al. 44 | 1. Perceived stress (Perceived Stress Scale)

59

2. Stress cortisol levels 60 3. Subjective wellbeing (Short Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale) 61 4. Physical activity (subjective Likert scale) 44 |

1. Pooling data across both groups showed a significant

decrease in perceived stress postintervention. Comparing

intervention to control, differences were only significant

at 10% level 2. Statistically significant improvements in cortisol patterns for 6/8 of the cortisol analyses 3. No significant difference in wellbeing scores post intervention 4. No significant difference in physical activity post intervention |

|

||

| Korn et al. 52 | 1. Height, weight, waist circumference, resting blood

pressure and fasting blood glucose 2. Quality of life (World Health Organisation Quality of Life-Brief Version) 62 3. Perceived stress (Perceived Stress Scale) 63 4. Life-threatening experiences (Life-Threatening Experiences Scale) 64 5. Social capital (Social Capital Scale) 65 6. Empathy (Parent/Partner Empathy Scale) 66 |

1. No significant change in BMI, waist circumference or

blood pressure at either follow-up 2. Non-significant increase in all domains of quality of life at 6 months. Significant improvements on all quality-of-life domains at 12 months 3. Perceived stress scores increased significantly at 6 and 12 months 4. Reports of life-threatening experiences decreased significantly from the baseline to 12 months 5. Mean social capital scale scores increased significantly at 12 months for participants who identified as parents or partners 6. No significant differences reported at 6 or 12 months postintervention |

|

||

| Community Gardening | |||||

| Grey et al. 48 | 1. Sense of community (The Sense of Community Index)

67

2. Personal wellbeing (The Personal Wellbeing Index) 68 |

1. Statistically significant result for only one domain –

satisfaction with health whereby participants reported being

less satisfied with their health at post-test compared to

pretest 2. Statistically significant increase in the shared emotional connection score and total score. No other significant differences from pretest to post-test were found |

|

||

| Grier et al. 49 | 1. Willingness to try fruit and vegetables

69

2. Self-efficacy for eating fruit and vegetables 70 3. Self-efficacy for asking for fruit and vegetables 71 4. Nutritional guidelines knowledge (MyPlate categories) 49 |

1. No significant effects on willingness to try fruit and

vegetables 2. No significant effects on self-efficacy for eating fruit and vegetables 3. Significant improvements were found for self-efficacy for asking for fruit and vegetables 4. Significant improvement on knowledge of nutritional guidelines post intervention |

|

||

| Martin et al. 54 | 1. Quantities of food groups (in g/day per person)

72

2. Expenditure for food (V/day per person) 72 |

1. Gardeners had significantly more produce in their food

supplies than non-gardeners, this remained significant when

just fruit and vegetables were considered 2. Gardeners spent significantly more money on food than the non-gardening group |

|

||

| Care Farming | |||||

| Poultry Husbandry | |||||

| Marquis et al. 53 | 1. End-line diet quality (minimum dietary diversity)

53

2. End-line nutritional status (weight for age, length-for-age, height-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height) 73 |

1. Compared with infants in the control group, infants in

the intervention group met minimum diet diversity and a

higher length-for-age, height-for-age and

weight-for-age 2. No group difference in weight-for-length or weight-for-height |

|

||

| Dallmann et al. 46 | 1. End-line diet quality (minimum dietary diversity)

53

2. Egg consumption (in the past 24 h) 3. End-line nutritional status (weight for age, length-for-age, height-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height) 73 |

1. Participation level was not associated with meeting the

minimum diet diversity 2. Compared with children in the control category, those in the intervention whose mothers had a high participation level were twice as likely to have consumed eggs the previous day 3. High and medium participation levels were associated with a similar increase in linear growth |

|

||

| Agriculture training | |||||

| Blakstad et al. 42 | 1. Dietary diversity (Food Frequency Questionnaire)

74

2. Food security (Household Food Insecurity Assessment Scale) 75 |

1. Intervention group consumed significantly more food

groups per day than the control group (at 12 months post

intervention). The proportion of participants consuming at

least 3/5 food groups per day was significantly greater in

the intervention group and intervention participants were

more likely to consume vitamin A-rich dark green vegetables,

and beans or peas when compared with controls 2. No statistical differences in household food insecurity score between intervention or control groups post intervention |

|

||

| Wilderness Arts & Crafts | |||||

| Sustainable building project | |||||

| Davies et al. 47 | 1. Mental Health (The Patient Health Questionnaire)

76

2. Resilience (The Brief Resilience Scale) 77 3. Wellbeing (Short Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale) 61 4. Social connectedness (Inclusion of Community in the Self Scale) 78 |

(1–4) No significant within-subject changes over time when

data from all participants, regardless of baseline score,

were analysed Statistical differences reported when the analysis was limited to participants that had baseline scores falling at or below the cut-off threshold for depression (large effect), anxiety (large effect) and resilience (medium to large effect) Note: study 1 and study 2 data pooled together for analysis |

|

||

| Green Exercise | |||||

| Park-based classes | |||||

| Booth et al. 43 | 1. Duration of moderate to vigorous physical activity (total

minutes per day, Fitbit)

43

2. Total step counts per day (Fitbit) 43 |

1. Significantly higher moderate–vigorous physical activity

minutes per day on days when participants did versus did not

attend the intervention 2. Significantly higher mean total step counts on days when participants did versus did not attend the intervention |

|

||

| Cohen et al. 45 | 1. Park-based energy expenditure and number of park users

(System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities)

79

2. Park use, physical activity, awareness of and participation in park-sponsored activities (surveys including questions from Minnesota Hearth Health Programme) 80 |

1 and 2. Over time, park use increased but there were no overall differences between the control and treatment arms |

|

||

| Han et al. 50 | 1. Number of park users (System for Observing Play and

Recreation in Communities)

79

2. Intensity of physical activity (Metabolic Equivalents) 81 |

1. Within-park comparison: Average METs per park user

increased from 2.58 to 2.75 due to the exercise

classes 2. Between-park comparison: during classes the study park had a higher number of parks users and METs than 95% of all other similar condition parks 3. Between-park comparison: No statistically significant differences observed during all other non-class times |

|

||

| Kling et al. 51 | 1. Body mass index (kg per m2)

82

2. Systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and heart beats per minute 82 3. Fitness performance (arm strength, chair stands, mobility) 83 |

1. Adjusted models found no significant differences for

BMI 2. Adjusted models found improvements in SBP and DBP across each time point (baseline to post intervention). No significant differences were observed for heart beats per minute 3. Adjusted models found improvements in arm strength, chair stands and mobility across each time point (baseline to post intervention) |

|

||

| Park prescriptions | |||||

| Razani et al. 55 | 1. Stress (Perceived Stress Score)

59

2. Park visits per week (participant recall) 3. Physiological stress (salivary cortisol levels) 55 4. Loneliness (modified UCLA Loneliness Score) 84 5. Physical activity (self-report and monitoring of pedometer) 85 6. Nature affinity (self-report scale). 86 7. Neighbourhood social support (self-report scale) 87 |

1. The change in perceived stress did not significantly

differ between the intervention and comparison conditions

(supported and independent park prescription groups) at the

1-month or 3-month follow-ups 2. The comparison condition (independent park prescription group) had a statistically significant increase of in park visits per week compared to the supported park prescription group 3–7. No significant group difference over time |

|

||

| South et al. 56 | 1. Time in greenspace (total minutes and number of visits

measured using smartphone GPS data)

56

2. Postpartum depression (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale). 88 |

1. When restricted to the participants that received the

intervention (as treated), the intervention was

significantly associated with a three times higher rate of

visits to nature compared to the control group 2. No significant differences were found in post-partum depression scores |

|

||

| Wexler et al. 57 | 1. Perceptions of park services, recalled park visit frequency and park-based physical activity duration (Survey of Parks, Leisure-time Activity and Self-reported Health) 57 |

1. Statistically significant treatment effect when controlling for a full set of covariates |

|

||

BMI: body mass index; GPS: global positioning system.

Overall effect key:

= overall positive effect;

= overall positive effect;  = mostly

positive effects (over half of outcomes);

= mostly

positive effects (over half of outcomes);  = some

positive effects (less than half of outcomes),

= some

positive effects (less than half of outcomes),  = no overall

positive effect.

= no overall

positive effect.

Overall benefits and quality of studies

To assess the overall benefits, a ‘traffic light’ coding system was applied (see Supplemental material 5). As illustrated in Table 3, six (33%) studies were coded green (overall positive effect), five (28%) yellow (mostly positive effects – over half of outcomes), six (33%) orange (some positive effects – less than half outcomes) and one (6%) red (no overall positive effect).

Overall, the quality appraisal scores on the Kmet et al. 39 checklist ranged from 50% to 96.2% (M = 79%; see Supplemental material 6 for detailed scoring). Based on the criteria, strengths were identified in appropriate and justified analytic methods, detailed reporting of study findings, providing estimates of variance in results and reporting of conclusions that were supported by the results. Partial scores were attributed to studies that lacked sufficient detail regarding the research question (n = 7), recruitment processes (n = 6) and participant characteristics (n = 7). In addition, studies that relied on small sample sizes or failed to provide justification for the sample size used (n = 11) were awarded partial scores.

While a broad range of outcomes were utilised in the reviewed studies, partial (n = 5) and no scores (n = 1) were attributed to those that failed to evidence the reliability or validity of the outcome measures used. Only seven studies provide sufficient evidence of controlling for confounding factors while partial (n = 7) and no scores (n = 4) were attributed to the remaining studies. Less than half of the reviewed studies (n = 8) were accredited full scores for evident and appropriate study designs with limitations identified in those studies that were feasibility projects or utilised non-controlled designs. Most of the reviewed studies evaluated between-group differences (n = 12) and eight studies included a control comparison condition. However, only six studies utilised a randomised approach to allocate participants to the experimental or control groups.

The biggest limitations observed in the reviewed literature were evident in the blinding criteria. Only two studies scored full marks for reporting on blinding of investigators to participant condition. One study scored partial marks, six studies received no marks and the remaining nine were studies in which blinding was not applicable. Due to the characteristics of NBIs, none of the reviewed studies were able to blind participants to the intervention. While a lack of intervention blinding may have been unavoidable, it is important to consider the potential for bias such as participant expectancy effects and the impact that this may have on study results.

Overview of studies

For this review, individual studies were grouped based on the category of NBI utilised (see table 3).

Therapeutic horticulture

Seven of the included studies (39%) evaluated the effectiveness of therapeutic horticulture interventions in the form of home gardening (n = 4) and community gardening (n = 3) projects in the local community or neighbourhood. These interventions provided gardening training and resources for individuals to utilise in their own personal garden at home or within a community setting (see Supplemental material 4).

Physical health and wellbeing

When evaluating physical health changes, the reviewed studies reported no significant improvements in body mass index, blood pressure, waist circumference 52 or physical activity levels. 44 Statistically significant increases were, however, observed in vegetable consumption,40,41 fruit and vegetable asking self-efficacy and awareness of nutritional guidelines. 49

Four of the reviewed studies explored the impact of therapeutic horticulture on personal wellbeing with mixed results. There was evidence of significant reductions in perceived and physiological measures of stress, 44 a significant increase in quality of life 52 and a significant increase in shared emotional connection postintervention. 48 In contrast, there was also evidence of a significant increase in perceived stress scores, 52 and no significant difference in overall wellbeing. 44 One study also identified a significant reduction in participants’ satisfaction with their health post-intervention. 48 In this study, older participants reported less satisfaction with their health than younger participants.

Produce and cost savings

In terms of cost savings, one study identified a statistically significant rise in the share of women selling vegetables at markets, 41 and there was also evidence that community gardeners yielded a statistically significant greater quantity of fruit or vegetable produce than controls. 54 One study reported similar cost savings per month for both community and home gardeners, 40 while another study found evidence to suggest that community gardeners spent significantly more money on food than a non-gardening sample. 54 It is necessary to highlight that both studies may be influenced by confounding demographic factors as they identified between-groups differences in baseline income, 40 and significant differences in the number of stores used when purchasing food. 54

Care farming or wilderness arts and crafts

Three (17%) of the reviewed publications evaluated the effectiveness of care farming interventions. In two studies, participants received poultry husbandry training. In one study, participants received training on a range of topics including fertiliser management, agronomical practices, pest management, crop harvesting, marketing vegetables, farm processes and nutrition counselling. Only one (6%) of the reviewed publications evaluated a wilderness arts and crafts intervention in which participants engaged in a sustainable building project where they developed construction and outdoor skills.

Diet and food insecurity

Benefits of agriculture training interventions included significant improvements in dietary diversity,42,53 consumption of nutrient rich foods 42 and likelihood of egg consumption. 46 One study also reported a non-significant reduction in likelihood of experiencing moderate-to-severe food insecurity for participants involved in the intervention when compared with controls. 42

Anthropometric changes

Two of the reviewed studies also reported improvements in anthropometric outcomes for the children of mothers who had participated in an agriculture training intervention.46,53 These infants were observed to have higher length-for-age, height-for-age and weight-for-age than those in the control sample, 53 and benefits were greater for children whose mothers had engaged most with the intervention. 46

Resilience, anxiety and depression

Davies et al. 47 reported significant improvements in resilience scores following the outdoor sustainable project. However, this difference was only observed when the analysis was restricted to participants who fell at or below a predefined clinical threshold at the baseline assessment. Davies et al. 47 also measured changes in anxiety and depression levels before and after the intervention and found a statistically significant improvement in anxiety and depression outcomes for participants who had elevated scores at baseline.

Green exercise

Seven (39%) of the reviewed studies evaluated the effectiveness of green exercise in the form of park prescriptions and park-based fitness classes.

Park visits and time in nature

Three studies identified a statistically significant increase in number of nature or park visits post intervention55–57 with greater benefits for participants who received a supported rather than unsupported park-prescription intervention. 55 There was also evidence that participants who received a park-prescription intervention reported higher rate of visits to nature than controls 56 and that intervention parks, which offered free exercise classes, had a greater number of park users than control parks. 50

In contrast, Cohen et al. 45 reported no significant differences in park use for participants who engaged in park-based fitness classes compared with controls and identified an association between participants’ perception of park safety and visits to the park, length of stay and engagement with the exercise classes.

Physical activity and health

Three studies identified a significant increase in physical activity43,50 and park-based activities 57 for participants attending green exercise interventions. One study observed a statistically significant negative interaction between age and the treatment effect. 57 In contrast, Cohen et al. 45 found no differences in physical activity between the green exercise intervention or control groups.

One study reported significant improvements in arm strength, mobility and blood pressure for older adults attending park-based fitness classes. 51 In this study, differences in physical health outcomes were observed between ethnic groups and greater improvements in blood pressure outcomes were identified among younger participants living in low poverty (compared to older participants in higher poverty).

Stress and depression

Two of the reviewed publications evaluated the effect of park prescriptions on mental health outcomes. South et al. 56 found no significant improvements in post-partum depression scores for new mothers after the intervention. Razani et al. 55 reported a significant decrease in perceived and physiological stress levels for participants in supported and unsupported park prescriptions when data for both groups were analysed together. However, no statistically significant differences were observed between groups. In this study, male gender (for parents) was significantly associated with reduced stress over the course of the study. In addition, an increase in number of park visits was significantly positively associated with decreased stress.

Discussion

Key points

The reviewed studies evaluated the effectiveness of therapeutic horticulture, care farming, green exercise and wilderness arts and crafts interventions on a range of economic, environmental, health and social outcomes.

Results were mixed and a broad range of outcome measures were used within the literature limiting the ability for direct comparisons.

Therapeutic horticulture interventions benefitted the production, consumption and marketing of vegetables. Care farming interventions improved diet diversity, food security and anthropometric outcomes. Wilderness arts and crafts improved anxiety and depression outcomes. Green exercise interventions enhanced nature visits, physical activity and physical health.

Age, gender, ethnicity, level of engagement and perception of environment safety influenced the effectiveness of the interventions.

The objective of this review was to explore the benefits of NBIs in socio-economically deprived communities. This review identified a broad range of interventions that have been evaluated to date, including therapeutic horticulture, care farming, green exercise and wilderness arts and craft. A range of economic, environmental, health and social co-benefits were observed.

Summary of results

Physical health outcomes for therapeutic horticulture interventions were mixed, with evidence of increased nutritional awareness 49 and vegetable consumption,40,41 but no changes in anthropometric measures 52 or physical activity. 44 Similarly, mental health outcomes were mixed with evidence of reduced 44 and increased stress; 52 and both increased quality of life 52 and reduced satisfaction in life post intervention. 48 Previous research in general population samples has also revealed mixed results for community gardening interventions on health outcomes, 89 although therapeutic horticultural interventions on the whole have been observed to have positive impact on both physical and mental health.33,90

This review also identified economic benefits of home and community gardening interventions with a significant increase in quantities of produce yielded 54 and marketing of produce. 41 In addition, agriculture training interventions were found to significantly improve diet diversity42,53 and anthropometric outcomes.46,53 There was also evidence of non-significant improvements in food security. 42 These findings may be particularly important when considering the evidence that domains of financial health are associated with both physical and mental health, 91 and highlights the value of considering interactions between co-benefits of NBIs.

Within this review, a sustainable building project intervention improved resilience, anxiety and depression outcomes for individuals who presented with poorer mental health at baseline. 47 Considering the evidence that individuals living in socio-economically deprived communities are at greater risk of mental health difficulties, 8 this finding is of particular importance. Moreover, encouraging people to engage with their local parks also demonstrated benefits. Park-based fitness classes and park-prescription interventions were found to improve the number of nature visits,55–57 physical activity43,50,57 and physical health for participants, 51 although improvements in depression outcomes were not observed. 56 There was also evidence of stress reduction for participants in supported and unsupported park prescriptions. These findings echo that of the study by Corazan et al. 92 who reviewed NBIs in a broad sample of general population studies (in which the study by Razani et al. 55 was the only low-income population study); suggesting that accessing local parks may act as a vehicle for improved physical health for both those who are from socio-economically deprived communities and the general population.

Implications

Clinical implications

Socio-economic health inequalities are well understood with clear evidence of increased mortality, 4 disease 5 and overall compromised mental and physical health7,8 for individuals living in socio-economic deprivation. It is also well established that the social determinants of health (individual living condition and wider systemic structures) have an important influence on health inequities, 93 and that health and illness follow a social gradient, thus those in a lower socio-economic position experience worse health.12,94 This review has demonstrated how NBIs may serve to address health inequalities, promoting improved physical, mental and financial health, thus levelling up the social gradient. Based on this evidence, future public health initiatives should continue to incorporate NBIs into health and social care planning for socio-economically deprived populations, both on an individual and community level.

This review identified broad mental health benefits of NBIs,44,47,48,52,55 and that NBIs may be of particular benefit for individuals in socio-economically deprived communities who experience mental health-related difficulties. 47 NBIs are increasingly being used within health services in the form of nature prescriptions with evidence to suggest positive effects of nature prescriptions on depression and anxiety. 95 Given the potential benefits of NBIs on mental health outcomes, future research and public health initiatives should endeavour to evaluate the benefits of NBIs in contrast to current treatment options for individuals from socio-economically deprived communities who experience mental health-related difficulties.

Urban planning

This review identified that an individuals’ perception of the safety of an environment may impact the benefits observed; 45 a barrier that has widely been reported within the field of green space literature.96–99 Perceived environmental safety and fear of crime is a particular concern for those of older age, 100 and for racialised individuals. 99 While recorded crime rates are substantially greater in the most socio-economically deprived areas, 101 research has shown that access to nature and NBIs can have a mitigating impact on violence. 102 As such urban planning initiatives should consider the two-way interaction between perceived environmental safety and NBI engagement for socio-economically deprived communities.

This review also highlighted that participants’ level of engagement with an intervention was positively related to the overall impact of the intervention. 46 Previous research has demonstrated that co-created interventions can lead to more sustained outcomes and greater participation.103,104 As such, it can be suggested that all stakeholders involved in the design of NBIs and green-space planning should collaborate with the communities they aim to serve to address pre-existing safety concerns and other potential barriers. Such collaboration may promote enhanced engagement with the intervention.

Future directions

Heterogeneity in measures

The reviewed studies evaluated a range of health, social, economic and environmental outcomes. Measures utilised included self-report surveys (e.g. mental wellbeing, physical activity, vegetable production); physiological measurements (e.g. cortisol levels, blood pressure); anthropometric measurements (e.g. height, weight); GPS trackers (e.g. Fitbit, mobile phone application) and observational methods (e.g. park use observations). While the broad range of outcome measures highlights the many co-benefits of NBIs, it also illustrates complexities observed in this review in drawing direct comparisons between NBI research. Future research should work towards developing a standardised measure or package of outcome measures to support comparisons of intervention effectiveness. Recent progress in this area includes the development of the ‘BIO-WELL scale’, which was established to empirically measure wellbeing and health effects following interactions with biodiversity. 105 While this new measure may offer a more comprehensive tool within the field of NBIs, it does not address the full range of co-benefits (health, economic, social and environmental) that are observed with NBIs, thus further research within this field is essential to allow better generalisability across studies examining a broader range of co-benefits. A recent systematic review protocol has been designed to evaluate health, wellbeing, social and environmental outcome measures for community gardening interventions. 106 The results of this review will be beneficial in supporting the development of standardised measurements and should be replicated with a broader range of NBIs.

Research design

The studies included in this review were of a moderate to high quality. Most of the reviewed studies (n = 12) evaluated between-group differences, but only six studies utilised a randomised approach to condition allocation. The randomised controlled trial design is traditionally regarded as the ‘gold standard’ for experimental research, as through the balancing of participant characteristics the overall potential for bias is reduced. 107 Moreover, only 8 (44%) of the included studies utilised a control comparison condition. From a public health perspective, such designs are advantageous as they allow conclusions to be drawn regarding the benefits of treatment interventions over standard care. As such, future research in this field should endeavour to incorporate control comparison conditions and utilise a randomised approach to condition allocation where possible.

Moreover, reporting of participant characteristics was identified as a weakness in much of the reviewed literature and almost half (n = 8, 44%) of the included studies did not report on participant ethnicity. It is well established that ethnicminority groups are disproportionately affected by socio-economic deprivation, 108 and that the effect of living in a deprived area impacts on ethnic minorities more disadvantageously. 109 As such, it is imperative that future NBI research and initiatives consider the interaction between socio-economic deprivation and ethnicity. An intersectional approach to future research would facilitate greater understanding of how people are exposed to, and experience combinations of inequalities differently. 110 Future research should therefore aim to go beyond the ‘what works’ question and draw on a realist evaluation approach to seek to answer the questions of ‘what works for whom in which circumstances’. 111

Strengths and limitations

The reviewed literature was limited to publications in English language and, therefore, may not fully represent the global body of research. In addition, while a strength of this review is the broad representation of different cultures and settings (8 different countries represented in 18 studies), attention must be paid to the unique context of the reviewed research and caution must be applied when evaluating the evidence together and the conclusions that can be drawn from these diverse set of studies.

Moreover, the heterogeneity in interventions across the reviewed studies limits the ability to fully understand which interventions, and more specifically which elements of these interventions, are responsible for the benefits observed. This is a common challenge faced when reviewing quantitative NBI research.112,113 As such, further reviews incorporating qualitative data may be valuable to better understand participants experiences of NBIs. Such data may also provide insight into the individual, contextual and inter-personal factors that enhance or reduce the benefits of NBIs in socio-economically deprived communities. While it is evident from this review that there are substantial benefits of a range of NBIs in socio-economically deprived communities, much remains to be done before these overall benefits are fully understood.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-rsh-10.1177_17579139231170768 for Exploring the benefits of nature-based interventions in socio-economically deprived communities: a narrative review of the evidence to date by H Harrison, M Burns, N Darko and C Jones in Perspectives in Public Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-rsh-10.1177_17579139231170768 for Exploring the benefits of nature-based interventions in socio-economically deprived communities: a narrative review of the evidence to date by H Harrison, M Burns, N Darko and C Jones in Perspectives in Public Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-rsh-10.1177_17579139231170768 for Exploring the benefits of nature-based interventions in socio-economically deprived communities: a narrative review of the evidence to date by H Harrison, M Burns, N Darko and C Jones in Perspectives in Public Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-rsh-10.1177_17579139231170768 for Exploring the benefits of nature-based interventions in socio-economically deprived communities: a narrative review of the evidence to date by H Harrison, M Burns, N Darko and C Jones in Perspectives in Public Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-5-rsh-10.1177_17579139231170768 for Exploring the benefits of nature-based interventions in socio-economically deprived communities: a narrative review of the evidence to date by H Harrison, M Burns, N Darko and C Jones in Perspectives in Public Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-6-rsh-10.1177_17579139231170768 for Exploring the benefits of nature-based interventions in socio-economically deprived communities: a narrative review of the evidence to date by H Harrison, M Burns, N Darko and C Jones in Perspectives in Public Health

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: H Harrison  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4835-7896

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4835-7896

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

H Harrison, Department of Psychology and Vision Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, LE1 7RH, UK.

M Burns, School of Biological Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK.

N Darko, NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre & School of Media, Communication and Sociology, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK.

C Jones, Clinical Psychology, Psychology and Vision Sciences, George Davies Centre, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester, LE1 7RH, UK.

References

*Reviewed publication.

- 1.United Nations Publication. World social report 2020: inequality in a rapidly changing world. New York: United Nations Publication; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamnisos D, Lambrianidou G, Middleton N. Small-area socioeconomic deprivation indices in Cyprus: development and association with premature mortality. BMC Public Health 2019;19(1):627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Vision. From the field. Global poverty: facts, FAQs, and how to help. Available online at: https://www.worldvision.org/sponsorship-news-stories/global-poverty-facts#facts (2020, last accessed 11 June 2022).

- 4.Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55(2):111–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flores G, Committee on Pediatric Research. Racial and ethnic disparities in the health and health care of children. Pediatrics 2010;125(4):979–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanson MD, Chen E. Socioeconomic status and health behaviors in adolescence: a review of the literature. J Behav Med 2007;30(3):263–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health 2001;91(11):1783–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wittchen HU, Jacobi F. Size and burden of mental disorders in Europe – a critical review and appraisal of 27 studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2005;15(4):357–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baena-Díez JM, Barroso M, Cordeiro-Coelho SI, et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak by income: hitting hardest the most deprived. J Public Health 2020;42(4):698–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Office for National Statistics. People, population and community: deaths involving COVID-19 by local area and socioeconomic deprivation: deaths occurring between 1 March and 31 July 2020. Available online at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsinvolvingcovid19bylocalareasanddeprivation/deathsoccurringbetween1marchand31july2020 (2020, last accessed 11 June 2022).

- 11.Department of Health and Social Care. Health and wellbeing during coronavirus: £5 million for social prescribing to tackle the impact of COVID-19. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/5-million-for-social-prescribing-to-tackle-the-impact-of-covid-19 (2020, last accessed 11 June 2022).

- 12.Marmot M. Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on. BMJ 2020;25:1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haubenhofer DK, Elings M, Hassink J, et al. The development of green care in western European countries. Explore (NY) 2010;6(2):106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson JM, Breed MF. Green prescriptions and their co-benefits: integrative strategies for public and environmental health. Challenges 2019;10(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shanahan DF, Astell–Burt T, Barber EA, et al. Nature–based interventions for improving health and wellbeing: the purpose, the people and the outcomes. Sports 2019;7(6):141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bragg R, Leck C. Good practice in social prescribing for mental health: the role of nature-based interventions. London: Natural England; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jepson R, Robertson R, Cameron H. Green prescription schemes: mapping and current practice. Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland; 2010, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raymond CM, Frantzeskaki N, Kabisch N, et al. A framework for assessing and implementing the co-benefits of nature-based solutions in urban areas. Environ Sci Policy 2017;77:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballew MT, Omoto AM. Absorption: how nature experiences promote awe and other positive emotions. Ecopsychology 2018;10(1):26–35. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lilford RJ, Oyebode O, Satterthwaite D, et al. Improving the health and welfare of people who live in slums. Lancet 2017;389:559–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cameron R, Hitchmough J. Environmental horticulture: science and management of green landscapes. Oxfordshire: CABI; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Vries S. Nearby nature and human health: looking at mechanisms and their implications. In: Ward Thompson C, Bell S, Aspinall P. (eds) Innovative approaches to researching landscape and health. Oxfordshire: Routledge; 2010, pp. 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansen MM, Jones R, Tocchini K. Shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) and nature therapy: a state-of-the-art review. IJERPH 2017;14(8):851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whatley E, Fortune T, Williams AE. Enabling occupational participation and social inclusion for people recovering from mental ill-health through community gardening. Aust Occup Ther J 2015;62(6):428–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pretty J, Barton J. Nature-based interventions and mind–body interventions: saving public health costs whilst increasing life satisfaction and happiness. IJERPH 2020;17(21):1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ulrich RS. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In: Altman J, Wohlwill J. (eds) Human behavior and environment. Boston, MA: Springer; 1983, pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan S. The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework. J Environ Psychol 1995;15(3):169–82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen J, Balfour R. Natural solutions to tackling health inequalities. Institute of Health Equity; 2014. Available online at: http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/natural-solutions-to-tackling-health-inequalities (last accessed 11 June 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waite S, Husain F, Scandone B, et al. ‘It’s not for people like (them)’: structural and cultural barriers to children and young people engaging with nature outside schooling. J Adventure Educ 2021;30:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell R, Popham F. Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: an observational population study. Lancet 2008;372:1655–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell RJ, Richardson EA, Shortt NK, et al. Neighborhood environments and socioeconomic inequalities in mental well-being. Am J Prev Med 2015;49(1):80–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maller C, Townsend M, Pryor A, et al. Healthy nature healthy people: ‘contact with nature’ as an upstream health promotion intervention for populations. Health Promot Int 2006;21(1):45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nejade R, Grace D, Bowman LR. What is the impact of nature on human health? A scoping review of the literature. J Glob Health 2022;12:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilkie S, Davinson N. Prevalence and effectiveness of nature-based interventions to impact adult health-related behaviours and outcomes: a scoping review. Landsc Urban Plan 2021;214:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Lancaster: Lancaster University; 2006, pp. 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, et al. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club 1995;123(3):A12–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song F, Parekh S, Hooper L, et al. Dissemination and publication of research findings: an updated review of related biases. Health Technol Assess 2010;14(8):1–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA group preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151(4):264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kmet LM, Cook LS, Lee RC. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. AHFMR 2004;13:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 40.*Algert S, Diekmann L, Renvall M, et al. Community and home gardens increase vegetable intake and food security of residents in San Jose, California. Calif Agric 2016;70(2):77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 41.*Baliki G, Brück T, Schreinemachers P, et al. Long-term behavioural impact of an integrated home garden intervention: evidence from Bangladesh. Food Secur 2019;11(6):1217–30. [Google Scholar]

- 42.*Blakstad MM, Mosha D, Bellows AL, et al. Home gardening improves dietary diversity, a cluster-randomized controlled trial among Tanzanian women. Matern Child Nutr 2021;17(2):e13096–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.*Booth JV, Messiah SE, Hansen E, et al. Objective measurement of physical activity attributed to a park-based afterschool program. J Phys Act Health 2021;18(3):329–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.*Suyin Chalmin-Pui L, Roe J, Griffiths A, et al. ‘It made me feel brighter in myself’-the health and well-being impacts of a residential front garden horticultural intervention. Landsc Urban Plan 2021;205:103958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.*Cohen DA, Han B, Derose KP, et al. Promoting physical activity in high-poverty neighborhood parks: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Soc Sci Med 2017;186:130–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.*Dallmann D, Marquis GS, Colecraft EK, et al. Maternal participation level in a nutrition-sensitive agriculture intervention matters for child diet and growth outcomes in rural Ghana. Curr Dev Nutr 2022;6(3):nzac017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.*Davies J, McKenna M, Bayley J, et al. Using engagement in sustainable construction to improve mental health and social connection in disadvantaged and hard to reach groups: a new green care approach. J Ment Health 2020;29(3):350–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.*Gray T, Tracey D, Truong S, et al. Community gardens as local learning environments in social housing contexts: participant perceptions of enhanced wellbeing and community connection. Local Environ 2022;27(5):570–85. [Google Scholar]

- 49.*Grier K, Hill JL, Reese F, et al. Feasibility of an experiential community garden and nutrition programme for youth living in public housing. Public Health Nutr 2015;18(15):2759–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.*Han B, Cohen DA, Derose KP, et al. Effectiveness of a free exercise program in a neighborhood park. Prev Med Rep 2015;2:255–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.*Kling HE, D’Agostino EM, Hansen E, et al. The feasibility of collecting longitudinal cardiovascular and fitness outcomes from a neighborhood park-based fitness program in ethnically diverse older adults: a proof-of-concept study. JAPA 2020;29(3):496–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.*Korn A, Bolton SM, Spencer B, et al. Physical and mental health impacts of household gardens in an urban slum in Lima, Peru. IJERPH 2018;15(8):1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.*Marquis GS, Colecraft EK, Kanlisi R, et al. An agriculture–nutrition intervention improved children’s diet and growth in a randomized trial in Ghana. Matern Child Nutr 2018;14(suppl 3):e12677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.*Martin P, Consalès JN, Scheromm P, et al. Community gardening in poor neighborhoods in France: a way to re-think food practices? Appetite 2017;116:589–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.*Razani N, Morshed S, Kohn MA, et al. Effect of park prescriptions with and without group visits to parks on stress reduction in low-income parents: SHINE randomized trial. PLoS ONE 2018;13(2):e0192921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.*South EC, Lee K, Oyekanmi K, et al. Nurtured in nature: a pilot randomized controlled trial to increase time in greenspace among urban-dwelling postpartum women. J Urban Health 2021;98(6):822–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.*Wexler N, Fan Y, Das KV, et al. Randomized informational intervention and adult park use and park-based physical activity in low-income, racially diverse urban neighborhoods. J Phys Act Health 2021;18(8):920–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Townsend M, Donohue S, Roche B, et al. Designing a food behavior checklist for EFNEP’s low-literate participants. JNEB 2012;44(4):74–5. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adam EK, Kumari M. Assessing salivary cortisol in large-scale, epidemiological research. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009;34(10):1423–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007;5(1):63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA, et al. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res 2004;13(2):299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Remor E. Psychometric properties of a European Spanish version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). Span J Psychol 2006;9(1):86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Motrico E, Moreno-Küstner B, de Dios Luna J, et al. Psychometric properties of the list of threatening experiences – LTE and its association with psychosocial factors and mental disorders according to different scoring methods. J Affect Disord 2013;150(3):931–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Onyx J, Bullen P. Measuring social capital in five communities. J Appl Behav Sci 2000;36(1):23–42. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Perez-Albeniz A, de Paul J. Gender differences in empathy in parents at high-and low-risk of child physical abuse. Child Abuse Negl 2004;28(3):289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chavis DM, Lee KS, Acosta JD. The sense of community (SCI) revised: the reliability and validity of the SCI-2. In 2nd international community psychology conference, Lisboa, 4 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 68.International Wellbeing Group. Personal wellbeing index. 5th edn.Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University; 2013, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thomson JL, McCabe-Sellers BJ, Strickland E, et al. Development and evaluation of WillTry. An instrument for measuring children’s willingness to try fruits and vegetables. Appetite 2010;54(3):465–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Geller KS, Dzewaltowski DA, Rosenkranz RR, et al. Measuring children’s self-efficacy and proxy efficacy related to fruit and vegetable consumption. J Sch Health 2009;79(2):51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Domel SB, Thompson WO, Davis HC, et al. Psychosocial predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption among elementary school children. Health Edu Res 1996;11(3):299–308. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marty L, Dubois C, Gaubard MS, et al. Higher nutritional quality at no additional cost among low-income households: insights from food purchases of ‘positive deviants’. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102(1):190–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.World Health Organization. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and development. France: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zack RM, Irema K, Kazonda P, et al. Validity of an FFQ to measure nutrient and food intakes in Tanzania. Public Health Nutr 2018;21(12):2211–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Coates J, Swindale A, Bilinsky P. Household food insecurity access scale (HFIAS) for measurement of food access: indicator guide. 3rd edn.Washington, DC: FANTA; 2007, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ–4. Psychosomatics 2009;50(6):613–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, et al. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med 2008;15(3):194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mashek D, Cannaday LW, Tangney JP. Inclusion of community in self scale: a single-item pictorial measure of community connectedness. JCOP 2007;35(2):257–75. [Google Scholar]

- 79.McKenzie TL, Cohen DA, Sehgal A, et al. System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC): reliability and feasibility measures. J Phys Act Health 2006;3:208–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jacobs DR, Jr, Ainsworth BE, Hartman TJ, et al. A simultaneous evaluation of 10 commonly used physical activity questionnaires. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993;25(1):81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32(suppl 9):S498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Franklin SS, Thijs L, Asayama K, et al. The cardiovascular risk of white-coat hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68(19):2033–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Functional fitness normative scores for community-residing older adults, ages 60-94. J Aging Phys Act 1999;7(2):162–81. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, et al. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res Aging 2004;26(6):655–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bassett DR, Jr, Ainsworth BE, Leggett SR, et al. Accuracy of five electronic pedometers for measuring distance walked. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996;28(8):1071–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Perkins HE. Measuring love and care for nature. J Environ Psychol 2010;30(4):455–63. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fan Y, Chen Q. Family functioning as a mediator between neighborhood conditions and children’s health: evidence from a national survey in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2012;74(12):1939–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hume C, Grieger JA, Kalamkarian A, et al. Community gardens and their effects on diet, health, psychosocial and community outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022;22(1):1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Soga M, Gaston KJ, Yamaura Y. Gardening is beneficial for health: a meta-analysis. Prev Med Rep 2017;5:92–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Weida EB, Phojanakong P, Patel F, et al. Financial health as a measurable social determinant of health. PLoS ONE 2020;15(5):e0233359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Corazon SS, Sidenius U, Poulsen DV, et al. Psycho-physiological stress recovery in outdoor nature-based interventions: a systematic review of the past eight years of research. IJERPH 2019;16(10):1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep 2014;129(suppl 2):19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. Available online at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (2023, last accessed 11 March 2023).

- 95.Nguyen PY, Rahimi-Ardabili H, Feng X, et al. Nature prescriptions: a scoping review with a nested meta-analysis. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gidlow CJ, Ellis NJ. Neighbourhood green space in deprived urban communities: issues and barriers to use. Local Environ 2011;16(10):989–1002. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sefcik JS, Kondo MC, Klusaritz H, et al. Perceptions of nature and access to green space in four urban neighborhoods. IJERPH 2019;16(13):2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ibes DC, Rakow DA, Kim CH. Barriers to nature engagement for youth of color. CYE 2021;31(3):49–73. [Google Scholar]