Abstract

The current systematic review sought to identify quantitative empirical studies that focused on the transdiagnostic factors of intolerance of uncertainty, emotional dysregulation and rumination, and their relation with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The overall research aim was to examine the relationship between these transdiagnostic factors and their relation with depression and PTSD symptoms. The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Out of the 768 articles initially identified, 55 met the inclusion criteria for the current review. The results determined that intolerance of uncertainty is indirectly related to depression and PTSD symptoms, mainly through other factors including emotion dysregulation and rumination. Additionally, emotional dysregulation is a significant predictor of both depression and PTSD symptoms. Rumination is a robust factor related to depression and PTSD symptoms, this relationship was significant in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. This review provides evidence on the transdiagnostic factors of intolerance of uncertainty, emotional dysregulation and rumination in the relationship with depression and PTSD symptoms.

Keywords: Intolerance of uncertainty, Emotional dysregulation, Rumination, Depression, Post-traumatic stress, Systematic review

Epidemiology prevalence and comorbidity

Depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders are among the leading contributors to the global disease burden (Whiteford et al., 2013). Depression is one of the most common mental disorders, with an estimated prevalence of 4.4% for the past year (WHO, 2017). Mental disorders rarely occur in isolation, particularly major depression disorder (MDD) has shown elevated comorbidity rates among different psychopathologies (Watson, 2009). This pattern of comorbidity can be seen with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Epidemiological studies indicate that around 80% of patients with PTSD may have comorbid disorders including depression, anxiety, or substance abuse (Foa et al., 2000). Among individuals who meet the criteria for PTSD diagnosis 48% to 55% also meet the criteria for MDD (Elhai et al., 2008; Kessler et al., 1995). This elevated comorbidity rate persisted even after controlling for overlapping symptoms (Brady et al., 2000; Elhai et al., 2008; Grubaugh et al., 2010).

Individuals with comorbid symptoms of depression and PTSD, when compared to individuals with only one type of symptom group, report lower levels of functioning, more severe symptoms, and poorer treatment outcomes (Brady et al., 2000). The presence of comorbidity entails difficulties for their diagnosis, clinical management, greater probabilities of resistance to treatment, recurrence, and use of health resources (Clark et al., 2012). However, despite the evidence of elevated comorbidity rates and considerable amount of symptom overlaps between depression and PTSD (Brady et al., 2000), the study of vulnerability factors has generally focused on their individual contribution to psychopathology (Hong & Cheung, 2015). However, less is known about basic psychological processes that may contribute to this comorbidity. Thus, it is important to understand what psychological factors contribute to the co-occurrence of depression and PTSD.

Transdiagnostic factors

Transdiagnostic models of psychopathology emerged in response to the evidence of the lack of specificity of vulnerability factors to explain individual mental disorders, as well as the overlap of symptoms of presumably categorically different disorders. A transdiagnostic approach to psychopathology aims to understand different mental disorders or consistent groups of mental disorders based on similar cognitive, behavioral, and physiological processes involved in their etiology (Sandín et al., 2012). Moreover, this approach has allowed generating a framework with a flexible conceptualization that facilitates the understanding of the comorbidity patterns present in psychopathology, based on common variables associated with the development, maintenance, and treatment (Aldao, 2012). The study of common vulnerability factors among disorders will make it possible to understand comorbidity, better define current diagnostic classification systems, and design appropriate treatment strategies for a wide range of disorders. Several vulnerability factors have shown associations with multiple psychopathological symptoms. Particularly, for symptoms of depression and PTSD, various factors of a transdiagnostic nature have been identified including: intolerance of uncertainty (Carleton et al., 2012; Gentes & Ruscio, 2011), emotional dysregulation (Sloan et al., 2017), and rumination (Aldao et al., 2010; Olatunji et al., 2013).

Intolerance of uncertainty

Intolerance to uncertainty is the dispositional inability of an individual to withstand the response triggered by the perceived absence of relevant, key or sufficient information (Carleton, 2016). Individuals with high levels of intolerance of uncertainty are more likely to interpret uncertainty negatively (Carleton et al., 2007). Moreover, uncertainty may contribute to maladaptive emotional, cognitive and behavioral processes that are associated with emotional distress, such as general anxiety disorder and panic disorder, (Boswell et al., 2013; Buhr & Dugas, 2009). Intolerance of uncertainty is a two-dimensional construct consisting of the prospective and the inhibitory dimensions. The prospective dimension has an anticipatory cognitive nature and is conceptualized as a desire for predictability of future events. The inhibitory dimension refers to behavioral paralysis and impaired functioning due to uncertainty (Carleton et al., 2007). Evidence from multiple studies indicating substantial associations between intolerance of uncertainty and internalizing disorders, has prompted researchers to conceptualize intolerance of uncertainty as a major transdiagnostic risk factor in these conditions (Shapiro et al., 2020). A recent meta-analysis underscored the transdiagnostic nature of intolerance of uncertainty, finding strong and significant associations between intolerance of uncertainty and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and eating disorders (McEvoy et al., 2019). Intolerance of uncertainty has also been suggested as a vulnerability risk factor for elevated PTSD symptoms (Banducci et al., 2016; Oglesby et al., 2016).

Emotion dysregulation

Emotional dysregulation is a multidimensional construct that involves maladaptive ways of responding to emotions, including (a) lack of awareness, understanding, and acceptance of emotions; (b) the inability to control behaviors when experiencing emotional distress; (c) lack of access to situationally appropriate strategies to modulate the duration and/or intensity of emotional responses to meet individual goals and situational demands; and (d) unwillingness or reluctance to experience emotional distress as part of seeking meaningful activities in life (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). People who have difficulties regulating their emotions are more likely to engage in maladaptive behaviors such as impulsivity, avoidance, substance use, and other risky behaviors (Weiss et al., 2012). Difficulties with emotional regulation have also demonstrated their transdiagnosis role in a range of psychopathologies including depression (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010), substance use disorder (Wong et al., 2013) and PTSD (Seligowski et al., 2014). Specifically, Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema (2010) examined the specificity of cognitive emotional regulation strategies from a transdiagnostic perspective. They found that dysfunctional emotional regulation strategies were associated with indicators of psychopathology symptoms (eating, depressive and anxious), this association remained regardless of the specific disorder.

Rumination

Rumination is defined as repetitive and passive thoughts about negative emotions, their possible consequences and causes (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Rumination prevents active problem solving to change the situations causing these negative emotions. Consequently, individuals focus on the problems and their feeling about them rather than taking action (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). It has been suggested that rumination consists of two components: reflection, which indicates a tendency to focus on one’s thoughts in order to find a solution to the problem or situation that distresses the individual, and brooding, which refers to a passive reflection were no action is taken to improve the situation (Treynor et al., 2003). Rumination has been traditionally associated with depressive symptoms and has been considered an important factor in the onset, maintenance, and recurrence of depression (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Olatunji et al., 2013). Individuals who engage in ruminative processes report greater levels of depressive symptoms over time (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). Rumination has also been identified as a maladaptive cognitive style associated with multiple disorders and symptoms (Aldao et al., 2010). Particularly, for PTSD symptoms it is considered an important factor that maintains and increases symptom severity (Szabo et al., 2017).

The present review

As previously mentioned, depression and PTSD are highly comorbid disorders with more than half of the people with a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD also meeting the criteria for a diagnosis of MDD (Elhai et al., 2008). This elevated comorbidity rate persisted even after controlling for overlapping symptoms (Brady et al., 2000; Elhai et al., 2008; Grubaugh et al., 2010). Transdiagnostic models and the study of vulnerabilities factors between depression and PTSD symptoms is important for better understanding of comorbidity, improving theoretical models of comorbidity and guiding clinical intervention. Thus, it is crucial to investigate how these factors play a role in the relationship between these highly comorbid disorders. The current systematic review sought to identify quantitative empirical studies that focused on the transdiagnostic factors of intolerance of uncertainty, emotional dysregulation and rumination, and their relation with symptoms of depression and/or PTSD. The overall research aim was to examine the relationship between these transdiagnostic factors and depression and /or PTSD symptoms.

Method

Literature search

The review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009). Studies were identified by searching multiple databases including PsychInfo, Medline, Web of Science, and Google Scholar during June and July 2021. Keywords/Search terms included various combinations of ‘intolerance of uncertainty’, ‘emotion regulation’, ‘emotional dysregulation’, ‘rumination’, ‘depression’, and ‘posttraumatic stress disorder’.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

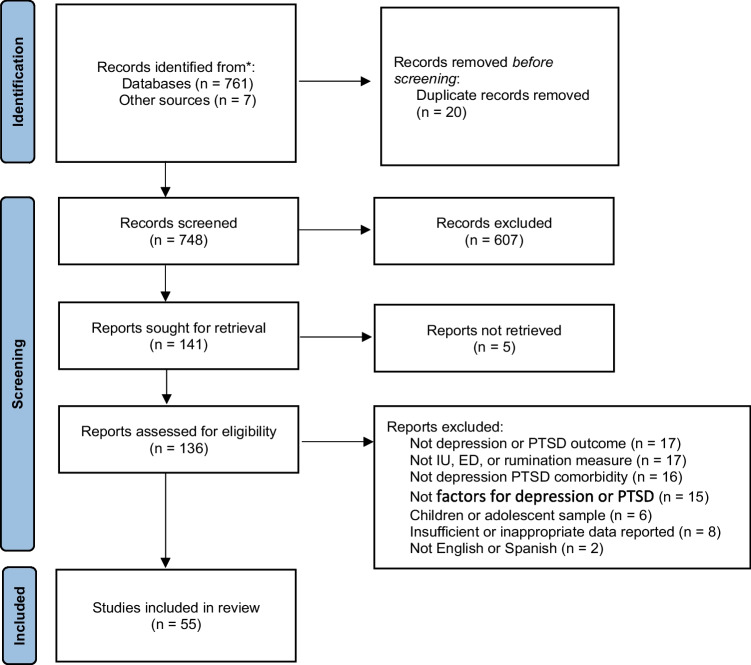

Eligible empirical studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) Empirical quantitative research reports published in a peer reviewed journal (2) Written in English or Spanish language, (3) Outcome measures related to depression or PTSD symptoms or diagnosis. Studies were excluded if the following criteria was met: (1) No depression or PTSD outcome measure, (2) No rumination, intolerance of uncertainty or emotional dysregulation measure, (3) Not depression PTSD comorbidity, (4) Children or adolescent sample, (5) Insufficient or inappropriate data reported (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram of articles selected for review. Note: IU = intolerance of uncertainty; ED = emotional dysregulation; PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Table 1.

Studies included in the systematic review

| Study | N | Sample characteristics | Design | Transdiagnostic variable measure | Outcome measure | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paulus et al. (2015) | 642 | Community | Cross-sectional |

IU (IUS) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

IU mediates the relationship between negative affect among several emotional disorders including depression |

| McEvoy and Erceg-Hurn (2016) | 108 | Community | Experimental |

IU (IUS-12) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

Changes in IU were associated with reductions in repetitive negative thinking, but not with depressive symptoms |

| Dar et al. (2017) | 120 | Clinical | Cross-sectional |

IU (IUS) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

Worry mediated and moderated the relationship between IU and symptoms of depression |

| Swee et al. (2018) | 221 | Undergraduate | Cross-sectional |

IU (IUS-12) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

IU is indirectly associated to depressive symptoms through worry and trait anxiety |

| Toro et al. (2018) | 506 | Community | Cross-sectional |

IU (IUS) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

Negative affect (state and trait) is a partial mediator of the relationship between II and depressive symptoms |

| Barry et al. (2019) |

66 48 |

Community Clinical |

Cross-sectional |

IU (IUS-12) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

IU and constructive and unconstructive rumination are predictors of depressive symptoms even when anxiety symptoms were accounted for. However, once anxiety symptoms were accounted for, they did not contribute to a depression diagnosis |

| Huang et al. (2019) |

494 321 |

Community |

Study 1 Cross-sectional Study 2 Longitudinal |

IU (IUS-12) |

Depression (PHQ-9) |

Rumination partially mediated the relationship between IU and depressive symptoms. However, rumination fully mediated this relationship over two months |

| Saulnier et al. (2019) | 374 | Clinical | Cross-sectional |

IU (IUS-12) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

IU general factor related with cognitive and affective/somatic depressive symptoms. While the inhibitory dimension of IU only related to the cognitive depressive symptoms |

| Del Valle et al. (2020) | 3805 | Community | Cross-sectional |

IU (IUS) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

IU was a significant predictor of depressive and anxiety symptoms in the context of COVID-19 pandemic |

| Voitsidis et al. (2021) | 2827 | Community | Cross-sectional |

IU (IUS) |

Depression (PHQ-9) |

Fear of COVID-19 partially mediated the association between IU and depressive symptoms |

| Chen et al. (2021) |

56 53 |

Community Clinical |

Cross-sectional |

IU (IUS-12) |

Depression (HAMD) |

Maladaptive negative metacognitive beliefs mediate the effect of IU on depression symptoms |

| Oglesby et al. (2016) | 50 | Undergraduate | Longitudinal |

IU (IUS) |

PTSD (PCL-C) |

Pre-trauma IU is a significant predictor of elevated post-trauma PTS symptoms following a campus shooting, even after covarying for pre-trauma levels of anxiety sensitivity |

| Boelen et al. (2016) | 134 | Community | Longitudinal |

IU (IUS-12) |

PTSD (PSS-SR) |

Inhibitory IU positively related to levels of PTS and depression symptoms, even when controlling for neuroticism, worry, and rumination. Prospective IU predicted prolonged grief disorder severity six month later but not PTSD or depression |

| Oglesby et al. (2017) | 126 | Community | Cross-sectional |

IU (IUS-12) |

PTSD (PCL-C) |

IU was associated with an increase in PTSD symptoms (except for re-experiencing), even after covarying for negative affect and anxiety sensitivity |

| Boelen (2019) | 193 | Undergraduate | Longitudinal |

IU (IUS-12) |

PTSD (PSS-SR) |

Inhibitory IU pre-event predicted post-event PTSD symptoms (except for the PTSD re-experiencing dimension) |

| Raudales et al. (2020) | 259 | Trauma exposed | Longitudinal |

IU (IUS) |

PTSD (PCL-C) |

Anxiety sensitivity, but not distress tolerance and intolerance of uncertainty, was a significant mediator between emotion dysregulation and 1‐month follow‐up PTSS |

| Badawi et al. (2021) | 123 | Clinical | Experimental |

IU (IUS-12) |

PTSD (PCL-5) |

Decreased in IU and inhibitory IU were associated with decreases in PTSD severity. However, prospective IU only associated with changes in re-experiencing, avoidance, and arousal PTSD symptom clusters |

| Abravanel and Sinha (2015) | 745 | Community | Cross-sectional |

ED (DERS) |

Depression (CES-D) |

Emotion dysregulation mediated the relationship between cumulative adversity and depressive symptoms independent of risk status |

| Ouimet et al. (2016) | 150 | Undergraduate | Cross-sectional |

ED (DERS) |

Depression (DASS) |

Emotion dysregulation and maladaptive belief about emotions mediated the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and depressive symptoms |

| Pickard et al. (2016) | 151 | Undergraduate | Cross-sectional |

ED (DERS) |

Depression (DASS) |

Mindfulness and emotional regulation fully mediated the relationship between three attachment styles (secure, preoccupied and dismissive) and depressive symptoms. However, fearful attachment partially mediated this relationship |

| Diedrich et al. (2017) | 69 | Clinical | Cross-sectional |

ER (ERSQ) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

The ability to tolerate negative emotions was the only emotional regulation skill that mediated the relationship between self-compassion and depressive symptoms |

| Mutz et al. (2017) | 364 | Community | Cross-sectional |

ER (ERQ) |

Depression (PHQ-9) |

Expressive suppression mediated the relationship between mental toughness and depressive symptoms |

| Khakpoor et al. (2019) | 26 | Clinical | Experimental |

ER (DERS) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

The Unified Protocol reduced depression in patients through improvement in emotion regulation. Difficulty engaging in goal-directed behavior and lack of emotional clarity, predicted 72% of variance in depression scores |

| Diehl et al. (2020) | 911 | Community | Cross-sectional |

ED (DERS) |

Depression (CUDOS) |

The relationship between emotion dysregulation and depression symptoms remained significant, when controlling for baseline mindfulness. However, when controlling for baseline emotion dysregulation, the association between mindfulness and depression was not significant in the majority of cases |

| Groarke et al. (2021) | 522 | Community | Longitudinal |

ED (DERS) |

Depression (PHQ-9) |

In the context of COVID-19 loneliness predicted higher depressive symptoms one month later, and depressive symptoms predicted higher loneliness one month later. This relationship was not mediated by emotion regulation difficulties. However, emotion regulation difficulties and depressive symptoms were reciprocally related |

| O’Bryan et al. (2015) | 297 | Undergraduate | Cross-sectional |

ED (DERS) |

PTSD (PDS) |

Difficulties with emotional acceptance significantly predicted greater avoidance and hyperarousal symptom severity above and beyond the effects of number of trauma types and negative affect. Emotion dysregulation was not significantly predictive of reexperiencing symptom severity |

| Short et al. (2016) | 746 | Trauma exposed | Cross-sectional |

ED (DERS) |

PTSD (PDS) |

Impulse control difficulties were associated across PTSS clusters (re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal), while lack of emotion regulation strategies and emotional clarity were uniquely associated with numbing symptoms, after covarying for neuroticism |

| Raudales et al. (2019) | 209 | Community | Cross-sectional |

ED (DERS) |

PTSD (PCL-C) |

Emotion dysregulation mediates the effects of trauma type on PTSD symptoms for sexual assault but no other trauma types, this effect remained significant after covarying for negative affect |

| Forbes et al. (2020) | 85 | Trauma exposed | Longitudinal |

ER (DERS) |

PTSD (PCL-5) |

Emotion dysregulation predicted PTSD symptom severity at 3 months, even after covarying other risk factors (age, gender, race, ethnicity, trauma type, childhood adversity or trauma exposure, and lifetime trauma exposure) and baseline PTSD symptoms |

| Pencea et al. (2020) | 135 | Trauma exposed | Longitudinal |

ER (EDS-short) |

PTSD (PSS) |

Emotion dysregulation predicted chronic PTSD symptom, even after controlling for trauma exposure, baseline PTSD and depressive symptoms |

| Fujisato et al. (2020) | 1794 | Community | Longitudinal |

ER (ERSQ) |

PTSD (PCL-5) |

Emotion regulation predicted PTSS 4-months later, even after controlling for symptoms at baseline |

| Post et al. (2021) | 200 | Clinical | Cross-sectional |

ER (ERQ) |

PTSD (PSS-I) |

Emotion regulation fully mediated the relationships between negative affect and PTSD and MDD, and negative mood regulation expectancies and PTSD and MDD |

| Iqbal and Dar (2015) | 77 | Clinical | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

Depression (BDI) |

Brooding and reflection rumination mediated the association between negative affect and depressive symptoms, but not anxiety |

| Vanderhasselt et al. (2016) | 92 | Undergraduate | Longitudinal |

Rumination (RRS) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

Co-variation of stressful events and rumination predicted depressive symptoms at 3 and 15 months. This effect remained even when statistically controlling for baseline depressive symptoms |

| Petrocchi and Ottaviani (2016) | 41 | Undergraduate | Longitudinal |

Rumination (RRS) |

Depression (CES-D) |

Rumination was a significant mediator of the relationship between nonjudge (mindfulness facet) and depressive symptoms after two years |

| Liu et al. (2017) | 87 | Clinical | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

Depression (HAMD) |

Rumination partially mediated the relationship between overgeneral autobiographical memory and depressive symptoms. Particularly, maladaptive brooding subtype of rumination |

| Vine and Marroquin (2017) | 100 | Clinical | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

Depression (MASQ AD) |

Rumination mediated associations of emotional clarity with depressive symptoms regardless of affect intensity |

| Schut and Boelen (2017) | 208 | Undergraduate | Longitudinal |

Rumination (RRS) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

Trait mindfulness, but not brooding, reflection, and experiential avoidance predicted depressive symptoms after one year, while controlling for baseline depression symptoms |

| Senra et al. (2017) | 438 | Community | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

Brooding-rumination and immature defenses mediated the relationship between perfectionism and depressive symptoms. Furthermore, brooding-rumination moderated the impact of perfectionism on depressive symptoms |

| Costa et al. (2018) |

70 70 |

Clinical Community |

Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

Depression (DASS) |

Cognitive fusion, but not rumination and mindfulness, was the only significant mediator of the relationship between negative affect and depressive symptoms |

| Bakker et al. (2018) | 100 | Clinical | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

Depression (PHQ-9) |

Brooding rumination, experiential avoidance, and acceptance mediated the relationship between self-compassion and depressive symptoms |

| Whisman et al. (2020) | 5891 | Community | Longitudinal |

Rumination (RRS) |

Depression (PHQ-9) |

Rumination predicted residual change in depressive symptoms and depressive symptoms predicted residual change in rumination (4-year follow-up), suggesting that rumination and depressive symptoms influence one another in a bidirectionally |

| Liang et al. (2020) | 501 | Undergraduate | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

Depression (CES-D) |

Peace of mind and rumination fully-mediated the relationship between gratitude and depression, this mediation model did not differ by gender |

| Lyon et al. (2020) | 3043 | Community | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

Depression (BSI) |

Brooding mediated the effect of neuroticism, extroversion, conscientiousness and openness on depressive symptoms. Reflection mediated the effects of neuroticism, extroversion and openness on depressive symptoms |

| De Rosa et al. (2021) |

151 42 |

Undergraduate Clinical |

Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRQ) |

Depression (BDI-II) |

Perfectionism is associated with rumination, in both the clinical and nonclinical populations. Rumination mediated the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and depression |

| Spinhoven et al. (2015) | 359 | Trauma exposed | Longitudinal |

Rumination (RUM) |

PTSD (PSS-I) |

Pre-trauma depression severity and trait rumination (but not trait worry) predicted onset of PTSD during four-year follow-up. Cognitive appraisal of the traumatic event partially mediated the association between trait rumination and PTSD |

| Wu et al. (2015) | 318 | Trauma exposed | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

PTSD (M-PTSD) |

Brooding rumination and depressed-related rumination are related with higher level of PTSD |

| Basharpoor et al. (2015) | 99 | Trauma exposed | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

PTSD (M-PTSD) |

Experimental avoidance and rumination in the group with PTSD were higher than those without PTSD. Mindfulness was significantly lower in the group with PTSD than without PTSD |

| Roley et al. (2015) | 45 | Trauma exposed | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RTSQ) |

PTSD (PCL-5) |

Repetitive rumination and anticipatory rumination moderates the relationship between PTSD and MDD symptoms |

| Seligowski et al. (2016) | 403 | Community | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

PTSD (PCL-5) |

Rumination was significantly related to each PTSD symptom clusters, even after controlling for negative affect |

| Viana et al. (2017) | 182 | Trauma exposed | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

PTSD (PDS) |

Mindful attention was a significant moderator of relations between rumination and all subfactors of PTSD symptoms (re-experiencing, avoidance, arousal, and total PTSD symptoms) |

| García et al. (2018) | 629 | Community | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

PTSD (SPRINT-E) |

Intrusive rumination mediated the relationship between negative rumination and posttraumatic stress symptoms |

| Pugach et al. (2019) | 90 | Community | Cross-sectional |

Rumination (RRS) |

PTSD (CAPS-5) |

Rumination fully mediated the relationship between overall emotional dysregulation and PTSD severity |

| Mathes et al. (2020) | 119 | Trauma exposed | Longitudinal |

Rumination (RRS) |

PTSD (PCL-C) |

Hostility temporally mediated the prospective association between rumination and PTSD symptoms, even when controlling depressive disorder diagnosis |

| Preston et al. (2021) | 204 | Trauma exposed | Longitudinal |

Rumination (RQ) |

PTSD (PDS) |

Interpersonal trauma moderated the relationship between baseline rumination and 1-month trauma symptoms, even after covarying for age and sex, treatment condition, negative affect, and number of previously experienced traumas |

IU Intolerance of uncertainty; ED Emotional dysregulation; ER Emotional; PTSD Posttraumatic stress disorder; IUS Intolerance of uncertainty scale; IUS-12 Intolerance of uncertainty scale short version; DERS Difficulties in emotion regulation scale; EDS-Short Emotion dysregulation scale, short version; ERSQ Emotion regulation skills questionnaire; BDI-II Beck depression inventory-II; PHQ-9 Patient health questionnaire-9; HAMD Hamilton depression rating scale; BSI Brief symptom inventory; CES-D Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale; DASS Depression anxiety stress scales, CUDOS Clinically useful depression outcomes scale; MASQ AD Anhedonic depression subscale of the mood and anxiety symptom questionnaire short form; PCL-5 Posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5; PCL-C Posttraumatic stress disorder checklist; M-PTSD Mississippi post-traumatic stress disorder scale; PSS-I PTSD symptom scale—interview version; CAPS-5 Clinician‐administered PTSD scale‐5; PSS Posttraumatic stress disorder symptom scale; PSS-SR PTSD symptom scale–self-report version; PDS Posttraumatic diagnostic scale; SPRINT-E Short posttraumatic stress disorder rating interview; RRS Ruminative response scale; RUM Subscale rumination on sadness of the revised version of the Leiden index of depression sensitivity; RTSQ Ruminative thought style questionnaire; RQ Rumination questionnaire; RRQ Rumination reflection questionnaire

Results

Study characteristics

The majority of studies were conducted in North America (43.6%), specifically USA (21 studies), and Canada (3 studies). Followed by 25.5% from European countries, 16.4% from Asia including China (4 studies), Japan (1 study), India and Iran (2 studies each), 7.2% from Oceania particularly, Australia (4 studies), and 7.2% from South America including Argentina (2 studies), Colombia and Chile (1 study each). Community-based studies were the most frequent type (39%), followed by undergraduate student sample (27.1%), clinical sample (18.6%), and trauma exposed sample (15.3%). Most of the studies were cross-sectional (66.1%), followed by longitudinal (28.6%) and a minority were experimental (5.4%).

Intolerance of uncertainty and depression

Eleven studies examined the relation between intolerance of uncertainty and depression symptomatology. Empirical evidence indicates that intolerance of uncertainty is a significant predictor of depression symptoms, even when anxiety symptoms where accounted for (Barry et al., 2019; Del Valle et al., 2020). Furthermore, the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and depression was indirect and partially mediated by other risk factors, including worry (Dar et al., 2017; Swee et al., 2018), trait anxiety (Swee et al., 2018), rumination (Huang et al., 2019), and fear of COVID-19 (Voitsidis et al., 2021). Two risk factors suggested a complete mediation of the effects of intolerance of uncertainty on depression symptoms: maladaptive metacognitive beliefs (Chen et al., 2021) and rumination over two months (Huang et al., 2019). Lower-order dimension analysis of intolerances of uncertainty and a two-factor model of depression indicated that a general factor of intolerance of uncertainty was related to cognitive and affective/somatic factors of depression symptoms (Saulnier et al., 2019). However, the Inhibitory dimension of intolerance of uncertainty was only related to the cognitive factor of depression, while the Prospective dimension was not related to any of these depression factors. Worry was the only risk factor that moderated the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and symptoms of depression, consequently high levels of worry heightened the association between intolerance of uncertainty and symptoms of depression (Dar et al., 2017). An experimental treatment study determined that reductions in intolerance of uncertainty were associated with reductions in repetitive negative thinking, but not with depression symptoms (McEvoy & Erceg-Hurn, 2016).

Intolerance of uncertainty and post-traumatic stress

Six studies that examined the relation between intolerance of uncertainty and PTSD symptoms. This evidence indicates that intolerance of uncertainty is a significant predictor of PTSD symptoms. These result remained significant even after covarying for other PTSD risk factors including: rumination, neuroticism, and worry (Boelen et al., 2016), anxiety sensitivity (Oglesby et al., 2016, 2017) and negative affect (Oglesby et al., 2017).

When the relation between intolerance of uncertainty and PTSD symptoms DSM-V clusters was examined, there was a significant association to the avoidance, hyperarousal and emotional numbing symptom clusters (Oglesby et al., 2017). Dimension analysis of intolerances of uncertainty indicated that only the inhibitory dimension was associated with PTSD symptoms (Boelen, 2019; Boelen et al., 2016). Further, a decrease in overall and inhibitory dimension was associated with decreases in PTSD severity and at the symptom cluster level. However, the prospective dimension only associated with changes in the re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal clusters (Badawi et al., 2021). Finally, mediation analysis determined that intolerance of uncertainty was not a significant mediator between distress tolerance and PTSD symptoms (Raudales et al., 2020).

Emotion dysregulation and depression

We identified 8 studies that assessed the relation between emotion dysregulation and depression symptoms. Results indicated that emotion dysregulation was positively associated with depressive symptoms, even when controlling for baseline mindfulness (Diehl et al., 2020). Furthermore, emotional dysregulation partially and significantly mediated the relationship between depression and various factors related to depressive symptomatology, including, cumulative adversity (Abravanel & Sinha, 2015), anxiety sensitivity (Ouimet et al., 2016), maladaptive beliefs about emotions (Ouimet et al., 2016), and attachment style (Pickard et al., 2016). One study examining which emotion regulation skill mediated the association between self-compassion and depression, determined that only the ability to tolerate negative emotions was a significant mediator (Diedrich et al., 2017). Likewise, expressive suppression was the only emotion regulation strategy that mediated the relationship between mental toughness and depressive symptoms (Mutz et al., 2017). Khakpoor et al. (2019) conducted an experimental study that examined how the Unified Protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders reduced depression in patients through improvement in emotion regulation. Emotion regulation, particularly difficulty engaging in goal-directed behavior and lack of emotional clarity, predicted most of the variance in depression scores. Furthermore, mediation analysis concluded that emotion regulation can be considered a mediating factor and a predictive of outcomes of transdiagnostic treatment based on the Unified Protocol (Khakpoor et al., 2019). Finally, in the context of COVID-19, loneliness predicted higher depressive symptoms and depressive symptoms predicted higher loneliness one month later. This relationship was not mediated by emotion regulation difficulties. Instead, emotion regulation difficulties and depressive symptoms were reciprocally related (Groarke et al., 2021).

Emotion dysregulation and post-traumatic stress

Seven studies assessed the relation between emotional dysregulation and PTSD symptoms. Longitudinal assessments found that emotional dysregulation was significantly associated with the probability of developing PTSD symptoms 4 months later (Fujisato et al., 2020) and at 12 months (Pencea et al., 2020), even when controlling for baseline PTSD, trauma exposure, and depressive symptoms. Likewise, emotion dysregulation predicted PTSD symptom severity at 3 months following exposure to a traumatic event, even after covarying for baseline PTSD symptoms and other risk factors such as, trauma type, childhood adversity, trauma exposure, lifetime trauma exposure, age, gender, race, and ethnicity (Forbes et al., 2020). Mediation analysis determined that emotional regulation mediated the effects of trauma type, particularly sexual assault, and PTSD symptoms (Raudales et al., 2019) and negative affect and PTSD and MDD (Post et al., 2021). When the relation between emotion dysregulation and PTSD symptom clusters were examined, emotional dysregulation only predicted avoidance and hyperarousal symptom severity even after covarying the number of trauma types and negative affect (O’Bryan et al., 2015). Difficulties in emotion regulation subscales analyses determined that difficulties in impulse control predicted re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal, whereas lack of emotion regulation strategies and emotional clarity were uniquely associated with emotional numbing symptoms (Short et al., 2016).

Rumination and depression

Thirteen studies examined the relation between rumination and depression symptoms. Results from longitudinal associations indicated that rumination predicts depressive symptoms and that depressive symptoms predict rumination at 4-year follow-up (Whisman et al., 2020). Likewise, a correlation of stressful events and rumination predicts depressive symptoms prospectively (3 and 15 months follow-up), even when controlling for baseline depressive symptoms (Vanderhasselt et al., 2016). However, one longitudinal study found that rumination (brooding and reflection subscale) did not predict depressive symptoms one year later, when compared to trait mindfulness and while controlling for baseline depression symptoms (Schut & Boelen, 2017). Mediation analysis determined that rumination was a significant mediator between maladaptive perfectionisms (De Rosa et al., 2021), gratitude (Liang et al., 2020), non-judge mindfulness component (two years after) (Petrocchi & Ottaviani, 2016), emotional clarity (Vine & Marroquin, 2017), overgeneral autobiographical memory (Liu et al., 2017), and negative affect (Iqbal & Dar, 2015) and depression symptoms. However, rumination was not a significant mediator of the relationship between negative affect and depression, when taking into account cognitive fusion in the mediation model (Costa et al., 2018), contradicting previous research (Iqbal & Dar, 2015). Subscale analysis of rumination indicated that brooding mediated the relationship between overgeneral autobiographical memory (Liu et al., 2017), perfectionism (Senra et al., 2017), self-compassion (Bakker et al., 2018) and depression symptoms. Further, brooding mediated the effect of various personality traits such as: neuroticism, extroversion, conscientiousness and openness on depressive symptoms, while reflection mediated the effects of neuroticism, extroversion and openness on depressive symptoms (Lyon et al., 2020).

Rumination and post-traumatic stress

Ten studies examined the relation between rumination and PTSD. Repetitive and anticipatory rumination moderated the relationship between PTSD and MDD symptoms (Roley et al., 2015). While, mindful attention moderated the relations between rumination and PTSD symptoms total, as well as all its symptom clusters (Viana et al., 2017). Interpersonal trauma moderated the relationship between baseline rumination and 1-month follow-up PTSD symptoms, even after covarying for negative affect, and number of previously experienced traumas (Preston et al., 2021). Longitudinal association determined pre-trauma depression severity and trait rumination predicted the onset of PTSD during a 4-year follow-up (Spinhoven et al., 2015). PTSD symptom clusters analysis indicated that rumination was significantly related to all symptom cluster (Seligowski et al., 2016). Mediation analysis determined that that hostility (Mathes et al., 2020), cognitive appraisal of the traumatic event (Spinhoven et al., 2015) and deliberate rumination (García et al., 2018) mediated the relationship between rumination and PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, rumination also acted as a mediator between emotional dysregulation and PTSD symptom severity (Pugach et al., 2019). Finally, experimental avoidance and rumination were compared in groups with and without PTSD, in the group with PTSD rumination was significantly higher than those without PTSD (Basharpoor et al., 2015). Brooding rumination and depressed-related rumination were related with higher level of PTSD (Wu et al., 2015).

Discussion

The current systematic review sought to identify quantitative empirical studies that focused on the transdiagnostic factors of intolerance of uncertainty, emotional dysregulation and rumination, and their relation with depression and/or PTSD. This review identified 55 studies that reported the association between the transdiagnostic factors of interest in depression and PTSD symptoms.

Intolerance of uncertainty was a consistent significant predictor for both depression and PTSD symptoms, as suggested by other authors (McEvoy et al., 2019; Shapiro et al., 2020). This association persisted after controlling other well-known risk factors (e.g., negative affect, worry, neuroticism, and anxiety sensitivity), however anxiety sensitivity was the only variable that covaried in both depression and PTSD symptoms. This may be explained by the evidence that suggests anxiety sensitivity is broadly related to a range of internalizing disorders particularly distress disorders such as depression, GAD and PTSD (Naragon-Gainey, 2010). Mediation analysis suggested that intolerance of uncertainty and depression are indirectly related. This relationship turned out to be partially mediated by other risk factors including worry and trait anxiety. Likewise, rumination had a partial mediation role in cross sectional studies, whereas longitudinally rumination fully mediated the relation between intolerance of uncertainty and depression. Therefore, individuals with high levels of intolerance of uncertainty ruminate over time as an attempt to cope with negative emotions, meanwhile increasing the risk of developing depressive symptoms (Huang et al., 2019). Only one study conducted a mediation analysis taking into consideration intolerance of uncertainty as a mediator between emotional dysregulation and PTSD symptoms, however this relation was not significant. This result suggests that intolerance of uncertainty may be indirectly related to PTSD symptoms possibly through other risk factors, in a similar way as found in depression symptoms. Lower-order dimension analysis of intolerances of uncertainty indicated that the inhibitor dimension was only related to cognitive factors of depression and PTSD clusters avoidance and hyperarousal. This result supports the notion that the inhibitory dimension refers to impaired functioning due to uncertainty. While the prospective dimension was not related to any individual factors of depression, it was related to avoidance, hyperarousal and re-experiencing PTSD symptoms. Particularly, this dimension has an anticipatory cognitive nature and is conceptualized as a desire for predictability of future events.

Emotional dysregulation has been found to relate to depression as well as many other psychiatric symptoms including PTSD (Aldao et al., 2010). In this systematic review emotional dysregulation was a significant predictor of both depression and PTSD symptoms. For depression symptoms this result was significant also after covarying for mindfulness. In relation to PTSD symptoms, longitudinal analyses determined that emotional dysregulation remained a significant predictor also after covarying other well established PTSD risk factors including, baseline PTSD symptoms, depressive symptoms, trauma type, trauma exposure, childhood adversity, lifetime trauma exposure, age, gender, race, and ethnicity. Furthermore, emotional dysregulation has a mediating effect between several risk factors and depression or PTSD symptoms such as, cumulative adversity, anxiety sensitivity, attachment style, maladaptive beliefs about emotions, sexual assault and negative affect. PTSD symptom cluster analysis indicated that emotional dysregulation predicted avoidance and hyperarousal symptoms but not re-experiencing, even when covarying for number of trauma types endorsed and negative affect. Specific associations between facets of difficulties in emotion regulation and PTSD symptom clusters determined that difficulties controlling impulses while distressed were associated with reexperiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptoms. Therefore, individuals with PTSD symptoms may engage in maladaptive behaviors to help regulate negative emotions such as impulsivity, avoidance, substance use and other risky behaviors (Weiss et al., 2012). Moreover, lack of effective emotion regulation strategies and lack of emotional clarity were related only to emotional numbing PTSD symptoms. This result is also consistent with findings that emotional regulation strategies are related to depression symptoms such as, loss of interest, feeling emotionally numb, and the inability of experiencing positive emotions (Aldao et al., 2010).

Rumination is an important factor related to the maintenance and exacerbation of depression and PTSD symptoms (Olatunji et al., 2013; Szabo et al., 2017). Longitudinal studies determined that rumination predicted both depression and PTSD symptoms at 4-year follow-up, even after accounting for the effects of baseline depressive symptoms. It should be noted that depression symptoms and rumination influenced one another bidirectionally, that is rumination predicts depressive symptoms and depressive symptoms predict rumination. Rumination has been found to mediate the relationship between depression and several factors related to depression symptoms including, maladaptive perfectionism, gratitude, overgeneral autobiographical memory, mindfulness, emotional clarity, and negative affect. These findings support the theoretic notion that rumination maintains distress, especially depression, through a variety of mechanisms (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Evidence for PTSD symptoms indicated that rumination only acted as a mediator between emotional dysregulation and PTSD symptom severity. However, the relationship between rumination and PTSD symptoms was mediated by other factors such as hostility, cognitive appraisal of the traumatic event, and deliberate rumination. PTSD symptom clusters analysis determined that rumination was significantly related to all symptom clusters, which highlights the importance of rumination in individuals who have been through a traumatic event and who may be at greater risk of developing PTSD symptoms. These studies also found that mindfulness and interpersonal trauma moderated of the relationship between rumination and PTSD symptoms. Consequently, interpersonal trauma enhances the association between rumination and PTSD symptoms, while mindfulness weakens this relation. Furthermore, rumination moderated the relationship between PTSD and MDD symptoms, this implies that higher levels of rumination in individuals with PTSD are more likely to also have greater depressive symptoms.

Limitations

This systematic review had a number of limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the results and addressed in future research. First, even though studies in Spanish were included in an attempt broaden the scope, the majority of the studies were conducted in North American and European countries. Furthermore, taking into consideration the evidence that culture may play a significant role in the manifestation of psychopathology (Rathod, 2017), the results of this study may have limited generalizability to other cultural contexts. Thus, there is a compelling need for future research in other regions of the world to better understand the impact of culture on psychopathology. Second, although elevated comorbidity rates between depression and PTSD symptoms are well known, only two studies were found that addressed comorbidity in these disorders. Future research should aim to investigate factors related to the comorbidity between depression and PTSD symptoms. Third, another significant limitation was that most of studies used cross-sectional samples, making it difficult to determine a causal inference. Additionally, most of the studies were from community-based samples which are more likely to present low to moderate symptom levels, thus some studies may have underrepresented symptom levels. This review used a systematic approach. Conducting a meta-analysis on the data would be an interesting future step, to get a more comprehensive understanding of the overall effect across the transdiagnostic factors. Additionally, future studies will need to employ quality assessment of eligible studies using quality assessment tools. Finally, this study relied on questionnaires to assess the variables of interest. Future research should consider incorporating additional measures, such as biomarkers or objective assessments, to provide a more comprehensive and objective understanding of the disorders being studied. Future research should consider incorporating additional measures, such as biomarkers or objective assessments. For example, recent studies have demonstrated that near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) can effectively identify diminished hemodynamic response in major depressive disorder patients, thus providing an objective assessment of depression (Husain et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022). Furthermore, fNIRS has shown potential in identifying brain markers associated with putative symptoms of PTSD (Balters et al., 2021).

Conclusion

This review provides evidence that the transdiagnostic factors of intolerance of uncertainty, emotional dysregulation and rumination are consistent significant predictors for both depression and PTSD symptoms. Particularly, intolerance of uncertainty is indirectly related to depression and PTSD symptoms through other factors including emotion dysregulation and rumination. Meanwhile, emotional dysregulation is a significant predictor of both depression and PTSD symptoms. Rumination is a robust factor related to depression and PTSD symptoms, this relationship was significant in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Both emotional dysregulation and rumination can mediate the relationship between several risk factors including intolerance of uncertainty and depression and PTSD symptoms. This study provides insight into understanding these factors in the onset and maintenance of depression and PTSD symptomatology. Consequently, contributing to the evidence that allows the development of theoretical and empirically supported transdiagnostic models. Which may ultimately promote the development of cost-effective treatments that targets underlaying mechanism or factors, thus promoting preventative alternatives for multiple disorders.

Acknowledgements

To the Master´s and Doctorate Program in Psychology UNAM. National University of Mexico (UNAM). To the University of Groningen.

Funding

National Council of Science and Technology (Mexico) (CONACYT). Doctoral scholarship number 751969 (scholar number 697623).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was received from the Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Higher Studies Iztacala, National Autonomous University of Mexico (CE/FESI/042022/1495).

Informed Consent

Not applicable

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Alejandrina Hernández-Posadas, Email: a.hernandez.posadas@rug.nl, Email: alejandrina.hernandez@iztacala.unam.mx.

Miriam J. J. Lommen, Email: m.j.j.lommen@rug.nl

Anabel de la Rosa Gómez, Email: anabel.delarosa@iztacala.unam.mx.

Theo K. Bouman, Email: t.k.bouman@rug.nl

Juan Manuel Mancilla-Díaz, Email: jmmd@unam.mx.

Adriana del Palacio González, Email: apg.crf@psy.au.dk.

References

- Abravanel BT, Sinha R. Emotion dysregulation mediates the relationship between lifetime cumulative adversity and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2015;61:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A. Emotion regulation strategies as transdiagnostic processes: A closer look at the invariance of their form and function. Revista de Psicopatologia y Psicologia Clinica. 2012;17(3):261–277. doi: 10.5944/rppc.vol.17.num.3.2012.11843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Specificity of cognitive emotion regulation strategies: A transdiagnostic examination. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48(10):974–983. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(2):217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawi A, Steel Z, Harb M, Mahoney C, Berle D. Changes in intolerance of uncertainty over the course of treatment predict posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in an inpatient sample. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2021 doi: 10.1002/cpp.2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker AM, Cox DW, Hubley AM, Owens RL. Emotion regulation as a mediator of self-compassion and depressive symptoms in recurrent depression. Mindfulness. 2018;10(6):1169–1180. doi: 10.1007/s12671-018-1072-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balters S, Li R, Espil FM, Piccirilli A, Liu N, Gundran A, Carrion VG, Weems CF, Cohen JA, Reiss AL. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy brain imaging predicts symptom severity in youth exposed to traumatic stress. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2021;144:494–502. doi: 10.1016/J.JPSYCHIRES.2021.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banducci AN, Bujarski SJ, Bonn-Miller MO, Patel A, Connolly KM. The impact of intolerance of emotional distress and uncertainty on veterans with co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2016;41:73–81. doi: 10.1016/J.JANXDIS.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry TJ, García-Moreno C, Sánchez-Mora C, Campos-Moreno P, Montes-Lozano MJ, Ricarte JJ. The unique and interacting contributions of intolerance of uncertainty and rumination to individual differences in, and diagnoses of depression. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2019;12(4):260–273. doi: 10.1007/s41811-019-00057-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basharpoor S, Shafiei M, Daneshvar S. The comparison of experimental avoidance, mindfulness and rumination in trauma-exposed individuals with and without posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in an Iranian Sample. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2015;29(5):279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA. Intolerance of uncertainty predicts analogue posttraumatic stress following adverse life events. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 2019;32(5):498–504. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2019.1623881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, Reijntjes A, Smid GE. Concurrent and prospective associations of intolerance of uncertainty with symptoms of prolonged grief, posttraumatic stress, and depression after bereavement. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2016;41:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell JF, Thompson-Hollands J, Farchione TJ, Barlow DH. Intolerance of uncertainty: A common factor in the treatment of emotional disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;69(6):630–645. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhr K, Dugas MJ. The role of fear of anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty in worry: An experimental manipulation. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(3):215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Killeen TK, Brewerton T, Lucerini S. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2000;61:22–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton NR. Into the unknown: A review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2016;39:30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton NR, Mulvogue MK, Thibodeau MA, McCabe RE, Antony MM, Asmundson GJG. Increasingly certain about uncertainty: Intolerance of uncertainty across anxiety and depression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2012;26(3):468–479. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton NR, Norton MAPJ, Asmundson GJG. Fearing the unknown: A short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21(1):105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Tan Y, Cheng X, Peng Z, Qin C, Zhou X, Lu X, Huang A, Liao X, Tian M, Liang X, Huang C, Zhou J, Xiang B, Liu K, Lei W. Maladaptive metacognitive beliefs mediated the effect of intolerance of uncertainty on depression. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2021 doi: 10.1002/cpp.2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D, Field S, Layard R. Mental health loses out in the National Health Service. The Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2315–2316. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, J., Pinto Gouveia, J., & Maroco, J. (2018). The role of negative affect, rumination, cognitive fusion and mindfulness on depressive symptoms in depressed outpatients and normative individuals. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy, 18(2), 207–220. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6476604

- Dar KA, Iqbal N, Mushtaq A. Intolerance of uncertainty, depression, and anxiety: Examining the indirect and moderating effects of worry. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;29:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa L, Miracco MC, Galarregui MS, Keegan EG. Perfectionism and rumination in depression. Current Psychology. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01834-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle M, Andrés ML, Urquijo S, YerroAvincetto MM, López Morales H, CanetJuric L. Intolerance of uncertainty over COVID-19 pandemic and its effect on anxiety and depressive symptoms. Interamerican Journal of Psychology. 2020;54(2):1–17. doi: 10.30849/ripijp.v54i2.1335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diedrich A, Burger J, Kirchner M, Berking M. Adaptive emotion regulation mediates the relationship between self-compassion and depression in individuals with unipolar depression. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2017;90(3):247–263. doi: 10.1111/papt.12107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl JM, McGonigal PT, Morgan TA, Dalrymple K, Harris LM, Chelminski I, Zimmerman M. Emotion regulation accounts for associations between mindfulness and depression across and within diagnostic categories. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 2020;32(2):97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai, J. D., Grubaugh, A. L., Kashdan, T. B., & Frueh, B. C. (2008). Empirical examination of a proposed refinement to DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder symptom criteria using the national comorbidity survey replication data. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(4), 597–602. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56916e4805f8e207077fb3ed/t/5692dba6df40f361d6f7e94f/1452465063259/ElhaiGrubaughKashdanEtAl2008.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ. Guidelines for treatment of PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13(4):539–588. doi: 10.1023/A:1007802031411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes CN, Tull MT, Rapport D, Xie H, Kaminski B, Wang X. Emotion dysregulation prospectively predicts posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity 3 months after trauma exposure. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2020;33(6):1007–1016. doi: 10.1002/jts.22551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisato H, Ito M, Berking M, Horikoshi M. The influence of emotion regulation on posttraumatic stress symptoms among Japanese people. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;277:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García FE, Vega Rojas N, Briones Araya F, Bulnes Gallegos Y. Rumination, posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic symptoms in people who have lived highly stressful experiences. Avances En Psicología Latinoamericana. 2018;36(3):443–457. doi: 10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.4983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gentes EL, Ruscio AM. A meta-analysis of the relation of intolerance of uncertainty to symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(6):923–933. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26(1):41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groarke JM, McGlinchey E, McKenna-Plumley P, Berry E, Graham-Wisener L, Armour C. Examining temporal interactions between loneliness and depressive symptoms and the mediating role of emotion regulation difficulties among UK residents during the COVID-19 lockdown: Longitudinal results from the COVID-19 psychological wellbeing study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;285:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubaugh AL, Long ME, Elhai JD, Frueh BC, Magruder KM. An examination of the construct validity of posttraumatic stress disorder with veterans using a revised criterion set. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48(9):909–914. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong RY, Cheung MWL. The structure of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression and anxiety: Evidence for a common core etiologic process based on a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychological Science. 2015;3(6):892–912. doi: 10.1177/2167702614553789. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang V, Yu M, Carleton NR, Beshai S. Intolerance of uncertainty fuels depressive symptoms through rumination: Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(11):e0224865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain, S. F., Tang, T. B., Yu, R., Tam, W. W., Tran, B., Quek, T. T., Hwang, S. H., Chang, C. W., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Cortical haemodynamic response measured by functional near infrared spectroscopy during a verbal fluency task in patients with major depression and borderline personality disorder. EBioMedicine, 51. 10.1016/J.EBIOM.2019.11.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Iqbal N, Dar KA. Negative affectivity, depression, and anxiety: Does rumination mediate the links? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;181:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic Stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakpoor S, Saed O, Armani Kian A. Emotion regulation as the mediator of reductions in anxiety and depression in the Unified Protocol (UP) for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Double-blind randomized clinical trial. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2019;41(3):227–236. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2018-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z., McIntyre, R. S., Husain, S. F., Ho, R., Tran, B. X., Nguyen, H. T., Soo, S. C., Ho, C. S., & Chen, N. (2022). Identifying neuroimaging biomarkers of major depressive disorder from cortical hemodynamic responses using machine learning approaches. EBioMedicine, 79. 10.1016/J.EBIOM.2022.104027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liang H, Chen C, Li F, Wu S, Wang L, Zheng X, Zeng B. Mediating effects of peace of mind and rumination on the relationship between gratitude and depression among Chinese university students. Current Psychology. 2020;39:1430–1437. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9847-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Yu, X., Yang, B., Zhang, F., Zou, W., Na, A., Zhao, X., & Yin, G. (2017). Rumination mediates the relationship between overgeneral autobiographical memory and depression in patients with major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1). 10.1186/s12888-017-1264-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lyon KA, Elliott R, Brown LJE, Eszlari N, Juhasz G. Complex mediating effects of rumination facets between personality traits and depressive symptoms. International Journal of Psychology. 2020;56(5):721–728. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathes BM, Kennedy GA, Morabito DM, Martin A, Bedford CE, Schmidt BM. A longitudinal investigation of the association between rumination, hostility, and PTSD symptoms among trauma-exposed individuals. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;277:322–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Erceg-Hurn DM. The search for universal transdiagnostic and trans-therapy change processes: Evidence for intolerance of uncertainty. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2016;41:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Hyett MP, Shihata S, Price JE, Strachan L. The impact of methodological and measurement factors on transdiagnostic associations with intolerance of uncertainty: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2019;73:101778. doi: 10.1016/J.CPR.2019.101778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutz J, Clough P, Papageorgiou KA. Do individual differences in emotion regulation mediate the relationship between mental toughness and symptoms of depression? Journal of Individual Differences. 2017;38(2):71–82. doi: 10.1027/1614-0001/a000224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naragon-Gainey K. Meta-Analysis of the Relations of Anxiety Sensitivity to the Depressive and Anxiety Disorders. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136(1):128–150. doi: 10.1037/a0018055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109(3):504–511. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3(5):400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Bryan EM, McLeish AC, Kraemer KM, Fleming JB. Emotion regulation difficulties and posttraumatic stress disorder symptom cluster severity among trauma-exposed college students. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2015;7(2):131–137. doi: 10.1037/a0037764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oglesby ME, Boffa JW, Short NA, Raines AM, Schmidt NB. Intolerance of uncertainty as a predictor of post-traumatic stress symptoms following a traumatic event. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2016;41:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oglesby ME, Gibby BA, Mathes BM, Short NA, Schmidt NB. Intolerance of uncertainty and post-traumatic stress symptoms: An investigation within a treatment seeking trauma-exposed sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2017;72:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Naragon-Gainey K, Wolitzky-Taylor KB. Specificity of rumination in anxiety and depression: A multimodal meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2013;20(3):225–257. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimet, A. J., Kane, L., & Tutino, J. A. (2016). Fear of anxiety or fear of emotions? Anxiety sensitivity is indirectly related to anxiety and depressive symptoms via emotion regulation. Cogent Psychology, 3(1). 10.1080/23311908.2016.1249132

- Paulus DJ, Talkovsky AM, Heggeness LF, Norton PJ. Beyond negative affectivity: A hierarchical model of global and transdiagnostic vulnerabilities for emotional disorders. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2015;44(5):389–405. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2015.1017529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pencea I, Munoz AP, Maples-Keller JL, Fiorillo D, Schultebraucks K, Galatzer-Levy I, Rothbaum BO, Ressler KJ, Stevens JS, Michopoulos V, Powers A. Emotion dysregulation is associated with increased prospective risk for chronic PTSD development. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2020;121:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrocchi N, Ottaviani C. Mindfulness facets distinctively predict depressive symptoms after two years: The mediating role of rumination. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016;93:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard JA, Caputi P, Grenyer B. Mindfulness and emotional regulation as sequential mediators in the relationship between attachment security and depression. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016;99:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Post, L. M., Youngstrom, E., Connell, A. M., Zoellner, L. A., & Feeny, N. C. (2021). Transdiagnostic emotion regulation processes explain how emotion-related factors affect co-occurring PTSD and MDD in relation to trauma. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 78. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102367 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Preston TJ, Gorday JY, Bedford CE, Mathes BM, Schmidt N. A longitudinal investigation of trauma-specific rumination and PTSD symptoms: The moderating role of interpersonal trauma experience. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;292:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugach CP, Campbell AA, Wisco BE. Emotion regulation in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Rumination accounts for the association between emotion regulation difficulties and PTSD severity. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2019;76(3):508–525. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathod S. Contemporary psychotherapy and cultural adaptations. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2017;47(2):61–63. doi: 10.1007/S10879-016-9344-5/METRICS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudales AM, Preston TJ, Albanese BJ, Schmidt NB. Emotion dysregulation as a maintenance factor for posttraumatic stress symptoms: The role of anxiety sensitivity. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2020;76(12):2183–2197. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudales AM, Short NA, Schmidt NB. Emotion dysregulation mediates the relationship between trauma type and PTSD symptoms in a diverse trauma-exposed clinical sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 2019;139:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.10.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roley ME, Claycomb MA, Contractor AA, Dranger P, Armour C, Elhai JD. The relationship between rumination, PTSD, and depression symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;180:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandín, B., Chorot, P., & Valiente, R. M. (2012). Transdiagnóstico: nueva frontera en psicología clínica. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 17(3), 187–203. http://e-spacio.uned.es/fez/eserv/bibliuned:Psicopat-2012-17-3-6005/Documento.pdf

- Saulnier KG, Allan NP, Raines AM, Schmidt NB. Depression and intolerance of uncertainty: Relations between uncertainty subfactors and depression dimensions. Psychiatry (New York) 2019;82(1):72–79. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2018.1560583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schut DM, Boelen PA. The relative importance of rumination, experiential avoidance and mindfulness as predictors of depressive symptoms. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2017;6(1):8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2016.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seligowski AV, Lee DJ, Bardeen JR, Orcutt HK. Emotion regulation and posttraumatic stress symptoms: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2014;44(2):87–102. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2014.980753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligowski AV, Rogers AP, Orcutt HK. Relations among emotion regulation and DSM-5 symptom clusters of PTSD. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016;92:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senra C, Merino H, Ferreiro F. Exploring the link between perfectionism and depressive symptoms: Contribution of rumination and defense styles. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017;74(6):1053–1066. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro MO, Short NA, Morabito D, Schmidt NB. Prospective associations between intolerance of uncertainty and psychopathology. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;166:110210. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Short NA, Norr AM, Mathes BM, Oglesby ME, Schmidt NB. An examination of the specific associations between facets of difficulties in emotion regulation and posttraumatic stress symptom clusters. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2016;40(6):783–791. doi: 10.1007/s10608-016-9787-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, E., Hall, K., Moulding, R., Bryce, S., Mildred, H., & Staiger, P. K. (2017). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic treatment construct across anxiety, depression, substance, eating and borderline personality disorders: A systematic review. In Clinical Psychology Review (Vol. 57, pp. 141–163). Elsevier Inc. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, Krempeniou A, van Hemert AM, Elzinga B. Trait rumination predicts onset of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder through trauma-related cognitive appraisals: A 4-year longitudinal study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2015;71:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swee MB, Olino TM, Heimberg RG. Worry and anxiety account for unique variance in the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and depression. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2018;48(3):253–264. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2018.1533579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo YZ, Warnecke AJ, Newton TL, Valentine JC. Rumination and posttraumatic stress symptoms in trauma-exposed adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 2017;30(4):396–414. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2017.1313835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro R, Alzate L, Santana L, Ramírez I. Afecto negativo como mediador entre intolerancia a la incertidumbre, ansiedad y depresión. Ansiedad y Estres. 2018;24(2–3):112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.anyes.2018.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27(3):247–259. doi: 10.1023/A:1023910315561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderhasselt M-A, Brose A, Ernst HWK, De Raedt R. Co-variation between stressful events and rumination predicts depressive symptoms: An eighteen months prospective design in undergraduates. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2016;87:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana AG, Paulus DJ, Garza M, Lemaire C, Bakhshaie J, Cardoso JB, Ochoa-Perez M, Valdivieso J, Zvolensky MJ. Rumination and PTSD symptoms among trauma-exposed Latinos in primary care: Is mindful attention helpful? Psychiatry Research. 2017;258:244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vine V, Marroquin B. Affect intensity moderates the association of emotional clarity with emotion regulation and depressive symptoms in unselected and treatment-seeking samples. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2017;42(1):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10608-017-9870-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voitsidis P, Nikopoulou VA, Holeva V, Parlapani E, Sereslis K, Tsipropoulou V, Karamouzi P, Giazkoulidou A, Tsopaneli N, Diakogiannis I. The mediating role of fear of COVID-19 in the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and depression. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2021;94(3):884–893. doi: 10.1111/papt.12315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Differentiating the mood and anxiety disorders: A quadripartite model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2009;5(1):221–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Viana AG, Anestis MD, Gratz KL. Impulsive behaviors as an emotion regulation strategy: Examining associations between PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors among substance dependent inpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2012;26(3):453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, du Pont A, Butterworth P. Longitudinal associations between rumination and depressive symptoms in a probability sample of adults. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;260:680–686. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Flaxman AD, Johns N, Burstein R, Murray CJL, Vos T. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CF, Silva K, Kecojevic A, Schrager SM, Bloom JJ, Iverson E, Lankenau SE. Coping and emotion regulation profiles as predictors of nonmedical prescription drug and illicit drug use among high-risk young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;132(1–2):165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders Global Health Estimates. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf;jsessionid=DD65D645058B0D401ABA9D0E22C12F44?sequence=1

- Wu, K., Zhang, Y., Liu, Z., Zhou, P., & Wei, C. (2015). Coexistence and different determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth among Chinese survivors after earthquake: Role of resilience and rumination. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement