Abstract

Introduction:

Although Hill–Sachs lesions are frequently associated with recurrent anterior glenohumeral dislocation, understanding of biomechanics and the importance of having an engaging or non-engaging lesion has only been recently studied at more depth. It is now widely accepted that engaging lesions benefit from surgery due to the high risk of symptom recurrence if left untreated. Techniques that have been described include capsular shift procedures, rotational osteotomies of the humeral head, or even femoral or humeral head allografts. The authors describe an alternative treatment which involves autogenous tricorticocancellous iliac crest graft to treat the bony defect in a patient with recurrent anterior glenohumeral dislocation and a large, engaging Hill–Sachs lesion.

Case Report:

A 33-year-old male with clinical history of two anterior-inferior dislocations of the left shoulder presented with chronic instability and a large Hill–Sachs defect (about 30% of the humeral head) with an anterior labrum lesion but no glenoid bony lesion. The defect was treated with a tailored autogenous tricorticocancellous iliac crest graft and fixed with headless compression screws. The patient returned to every-day activities at 5 months postoperatively and has a complete range of motion no complications were observed.

Conclusion:

This appears to be a safe and painless technique with excellent functional results, that should, however, be validated in the future with prospective randomized controlled trials.

Keywords: Hill–Sachs, autogenous, graft, glenohumeral dislocation

Learning Point of the Article:

Using autogenous iliac crest graft is a safe and reproducible technique when treating recurrent shoulder instabilities with large Hill–Sachs lesions.

Introduction

Recent advances in imaging techniques and knowledge of biomechanics have led to a better and more complete understanding of recurrent anterior shoulder dislocations and associated lesions. Of these, Hill–Sachs lesions are very commonly found (76–100%) [1, 2]. These impaction fractures of the posterior-superior humerus head may sometimes require surgical treatment, and it is now known that large lesions (20–45% of articular surface) [3] benefit from surgery due to the high risk of recurrence if left untreated. These lesions combined with those of the glenoid are even more important to recognize due to their importance in future instability and are many times the deciding factor for surgical indication.

To better understand these lesions and how to address them, we should look back to Burkhart and De Beer [4] who began to describe engaging or non-engaging lesions, depending on whether the Hill–Sachs defect would catch on the anterior-inferior glenoid rim during the extremes of shoulder range of motion. The challenge became measuring the Hill–Sachs lesion, and focus was mainly on finding which size, the critical size, after which a bony repair had to be performed. Later, Yamamoto and Itoi [5, 6, 7] described the concept of the glenoid track and with this came the description of off track and on track lesions. Simply put, if the Hill–Sachs lesion does not completely disturb the glenoid track (on track lesion), then surgical repair of soft-tissues may be sufficient. Thus, the position of the Hill–Sachs lesion on the humeral head becomes important, along with its relationship with the glenoid track [8].

Techniques that have been described include Bankart repair, remplissage, Latarjet, and capsular shift procedures. However, when dealing with more complex and severe lesions such as bipolar bone loss or large, off track humeral head lesions, these techniques alone have proven to be insufficient. Humeral head reconstruction, femoral or humeral head allografts, percutaneous balloon humeroplasty, partial resurfacing arthroplasty, or even a hemiarthroplasty are reserved for more severe cases [5].

The authors describe treatment that involves an autogenous tricorticocancellous iliac bone graft to treat the bony defect in a patient with recurrent anterior glenohumeral dislocation and a large, off track Hill–Sachs type lesion.

Current literature describing this technique is incredibly scarce, having the authors not found a single systemic review or randomized controlled trial (RCT), and less than a handful of published cases on the subject matter.

Case Report

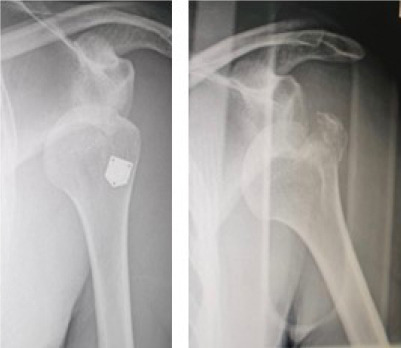

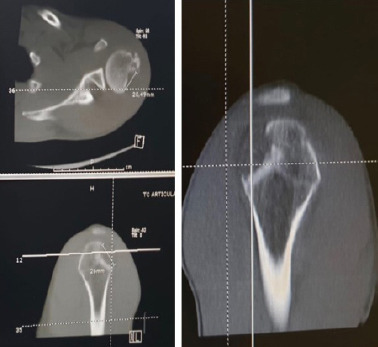

A 33-year-old male suffered a fall onto an outstretched hand. He immediately felt severe pain in his left shoulder and limited range of motion. He promptly appeared at a local ER, radiographs showed an anterior-inferior left-sided glenohumeral dislocation. A closed reduction was performed and the patient immobilized in a simple arm sling for 3 weeks, with 2 months of physiotherapy after this. Twelve months after the initial incident, while performing an overhead activity, he suffered a second anterior-inferior dislocation of the left shoulder. Again, a closed reduction was performed and a sling was worn. At this point, a large osseous defect was noted on his admission radiograph (Fig. 1) and a follow-up computed tomography scan was requested. This showed a significant Hill–Sachs lesion that occupied about 30% of the humeral head (Fig. 2) but no bony defect of the glenoid.

Figure 1.

X-rays on admission of the first (left) and second (right) shoulder dislocations.

Figure 2.

Pre-operative computed tomography scan.

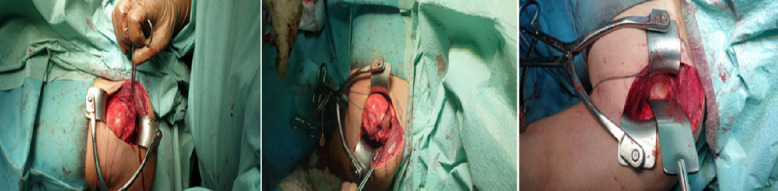

The authors proceeded with surgical treatment of the patient’s chronic anterior shoulder instability. In the beach-chair position and through a deltopectoral approach, the subscapularis was peeled from the lesser tuberosity, the interval between the subscapularis and the anterior capsule was developed, and a laterally based capsulotomy was performed. The anterior-inferior capsule was then released from the humeral neck and the humeral head was dislocated anteriorly. A Bankart lesion was identified along with a large Hill–Sachs defect that measured 21 × 26 × 40 mm. An autogenous tricorticocancellous bone graft from the patients left iliac crest was then harvested and taylored to fit the defect (Fig. 3). The graft was then stabilized using two headless compression screws (HCS) (Synthes HCS™ – 3.5 mm) and a fibrin glue was used as an adjuvant (Fig. 4). The anterior labrum was then repaired with two anchors (Arthrex Titanium Corkscrew™ 2.4 mm) and the subscapularis was repaired with two anchored mattress knots (Arthrex Titanium Corkscrew™ 2.4 mm). The skin was then closed with metallic sutures and no surgical drain was used.

Figure 3.

Intraoperative images of the Hill–Sachs lesion and the glenoid.

Figure 4.

Intraoperative X-ray images of the bone graft and fixation.

Postoperatively, the left upper limb was immobilized in internal rotation with a simple suspension brace for 4 weeks. The wound healed properly and at 2 weeks postoperatively the patient began Codman passive range exercises. Physiotherapy was delayed until 3 months postoperatively due to the coronavirus outbreak and was carried out for a total of 2 months. Active range exercises were initiated at 8 weeks postoperatively. Twelve months after surgery, the patient has returned to every day activity, although he is yet to return to sporting activity. He has residual complaints of pain (VAS-1), no sensation of instability, and range of motion is complete and symmetric to the contralateral shoulder. Internal and external rotation is effortless and painless (Table 2).

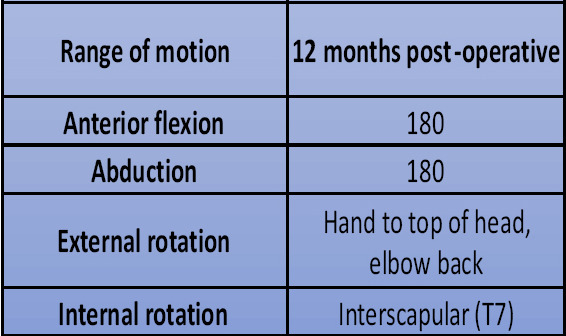

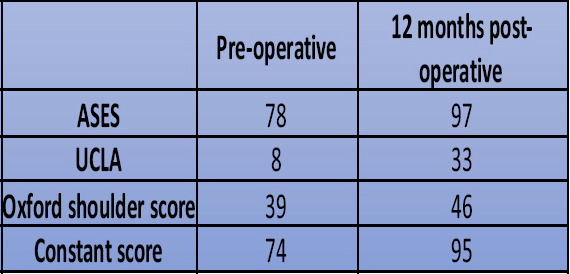

Table 2.

Pre- and post-operative range of motion.

Table 1.

Pre- and post-operative scores.

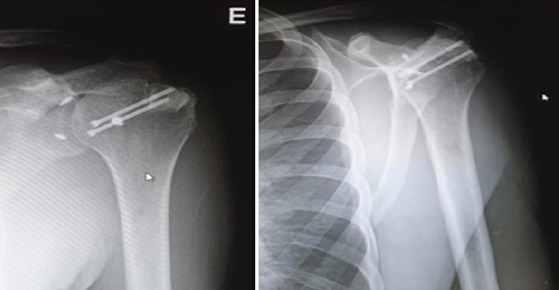

There is radiographic evidence of graft consolidation and no complications have been reported to date (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Post-operative radiographs.

Discussion

There are several procedures to treat recurrent anterior glenohumeral instability, and more recently techniques described to address large Hill–Sachs lesions. When over 20–25% of articular surface, these lesions have a higher probability of engaging, especially in combination with a lesion of the glenoid or labrum [9]. Dealing with a combined lesion now bears more weight on the surgical decision than the mere size of the Hill–Sachs defect. Engaging lesions may cause pain, discomfort, apprehension, and subluxation/dislocation, hence the need for surgical treatment. Techniques described include capsular shift humeral rotational osteotomy or resurfacing, hemiarthroplasties, and filling the defect with a bone graft when these lesions are particularly large. If executed correctly, bone grafting can deliver excellent functional results [10] – it preserves range of motion (vs. capsular shift that restricts external rotation), aims to restore original anatomy, and has shown an extremely low recurrence rate [2]. When combined with an osseous defect of the glenoid rim (bipolar bone loss) and arthroplastic procedures want to be avoided, associating a humeral side bone graft with labral repair or a Latarjet procedure can produce satisfying results [9, 11, 12].

The literature is scarce in regard to the use of autogenous iliac crest graft for Hill–Sachs lesions, so little in fact that previously most bone grafts have been allografts. There seem to be some advantages; however, autografts are inexpensive and are readily available in most patients, with few complications associated to the graft harvesting. Second, tricorticocancellous bone makes for a structurally stable graft, more so than an allograft, with lower delayed-union and non-union rates [13]. It may be argued that this technique does not allow for reconstruction of articular cartilage –this may be of lesser importance because no weight-bearing occurs in the shoulder and the area of Hill–Sachs lesions that contact the glenoid only does so at final degrees of range of motion [1].

In our case, we used two HCS instead of headed lag-screws, absorbable pins or K-wires. Since being designed by Herbert and later modified by Whipple, the HCS has become a trustworthy option due to its ability to provide internal compression while being embedded below the articular surface, because there is no protruding material, surrounding tissue damage and irritation is avoided [14]. Headed lag-screws may cause complications due to a protruded head, leading to conflict, secondary injury and even arthrosis, with a second surgery required to remove them. Some issues due to poor compression have also been mentioned [15]. K-wire fixation could lead to loss of reduction with fracture distraction and/or instability, jeopardizing the final outcome [13]. Absorbable pins can be considered as an adequate fixation method for low-stress areas, although some questions remain about biological compatibility, mechanical stability, and absorbability [16].

Conclusion

The literature on this technique is insufficient, and its efficacy must be validated in future RCTs. However, if appropriately fitted, autogenous tricorticocancellous iliac crest graft can be an option in patients with anterior recurrent shoulder dislocation and large Hill–Sachs. It appears to deliver safe, painless, and excellent functional recoveries to its patients if properly executed.

Clinical Message.

The authors believe that the technique shared is not one widely used and literature on its efficacy and outcomes is scarce. Sharing this case can be of value for this reason. The technical note demonstrated in this case may be of particular use to other colleagues who are facing the difficult challenge of treating patients with recurrent instabilities and large Hill–Sachs defects.

Biography

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Nil

Source of Support: Nil

Consent: The authors confirm that informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report

References

- 1.Rowe CR, Zarins B, Ciullo JV. Recurrent anterior dislocation of the shoulder after surgical repair. Apparent causes of failure and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:159–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norlin R. Intraarticular pathology in acute, first-time anterior shoulder dislocation:An arthroscopic study. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:546–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(05)80402-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miniaci A, Gish MW. Management of anterior glenohumeral instability associated with large Hill-Sachs defects. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;5:170–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burkhart SS, De Beer JF. Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs:Significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:677–94. doi: 10.1053/jars.2000.17715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamoto N, Itoi E, Abe H, Minagawa H, Seki N, Shimada Y, et al. Contact between the glenoid and the humeral head in abduction, external rotation, and horizontal extension:A new concept of glenoid track. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:649–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itoi E. 'On-track'and 'off-track'shoulder lesions. EFORT Open Rev. 2017;2:343–51. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.2.170007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto N, Itoi E. Osseous defects seen in patients with anterior shoulder instability. Clin Orthop Surg. 2015;7:425–9. doi: 10.4055/cios.2015.7.4.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trivedi S, Pomerantz ML, Gross D, Golijanan P, Provencher MT. Shoulder instability in the setting of bipolar (glenoid and humeral head) bone loss:The glenoid track concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2352–62. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3589-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen AL, Hunt SA, Hawkins RJ, Zuckerman JD. Management of bone loss associated with recurrent anterior glenohumeral instability. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:912–25. doi: 10.1177/0363546505277074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bushnell BD, Creighton RA, Herring MM. Bony instability of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:1061–73. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peshin C, Jangira V, Gupta RK, Jindal R. Neglected anterior dislocation of shoulder with large Hillsach's lesion and deficient glenoid:Treated by autogenous bone graft and modified Latarjet procedure. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2015;6:273–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox JA, Sanchez A, Zajac TJ, Provencher MT. Understanding the Hill-Sachs lesion in its role in patients with recurrent anterior shoulder instability. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10:469–79. doi: 10.1007/s12178-017-9437-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh JH, Lee SH, Gong HS, Baek GH, Chung MS, Kim JY. Autogenous tricorticocancellous iliac bone graft fixed with absorbable pins for the reconstruction of engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;9:55–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assari S, Darvish K, Ilyas AM. Biomechanical analysis of second-generation headless compression screws. Injury. 2012;43:1159–65. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoi E, Yamamoto N, Kurokawa D, Sano H. Bone loss in anterior instability. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6:88–94. doi: 10.1007/s12178-012-9154-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi W, Zhan J, Yan Z, Lin J, Xue X, Pan X. Arthroscopic treatment of posterior instability of the shoulder with an associated reverse Hill-Sachs lesion using an iliac bone-block autograft. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019;105:819–23. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2019.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]