Abstract

The presence of key hypoxia regulators, namely, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α or HIF-2α, in tumors is associated with poor patient prognosis. Hypoxia massively activates several genes, including the one encoding the BCRP transporter that proffers multidrug resistance to cancer cells through the xenobiotic efflux and is a determinant of the side population (SP) associated with cancer stem-like phenotypes. As natural medicine comes to the fore, it is instinctive to look for natural agents possessing powerful features against cancer resistance. Hypericin, a pleiotropic agent found in Hypericum plants, is a good example as it is a BCRP substrate and potential inhibitor, and an SP and HIF modulator. Here, we showed that hypericin efficiently accumulated in hypoxic cancer cells, degraded HIF-1/2α, and decreased BCRP efflux together with hypoxia, thus diminishing the SP population. On the contrary, this seemingly favorable result was accompanied by the stimulated migration of this minor population that preserved the SP phenotype. Because hypoxia unexpectedly decreased the BCRP level and SP fraction, we compared the SP and non-SP proteomes and their changes under hypoxia in the A549 cell line. We identified differences among protein groups connected to the epithelial–mesenchymal transition, although major changes were related to hypoxia, as the upregulation of many proteins, including serpin E1, PLOD2 and LOXL2, that ultimately contribute to the initiation of the metastatic cascade was detected. Altogether, this study helps in clarifying the innate and hypoxia-triggered resistance of cancer cells and highlights the ambivalent role of natural agents in the biology of these cells.

Keywords: Hypericin, Hypoxia, Breast cancer resistance protein, Side population, ECM reorganization, Proteomics

Highlights

-

•

Hypericin effectively accumulated in cancer cells despite hypoxia.

-

•

Hypericin potentiated the degradation of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in cancer cells.

-

•

ABCG2/BCRP level decreased because of hypoxia impact.

-

•

Coaction of hypoxia and hypericin reduced the SP population almost to a minimum.

-

•

Proteomics of normoxic and hypoxic SP showed a change in EMT-related proteins.

1. Introduction

Decreased oxygen availability in tumor tissues, commonly known as tumor hypoxia, is a typical characteristic of the solid tumor microenvironment occurring due to the uncontrollable proliferation of cancer cells, often exceeding the rate of neovascularization [reviewed in [1]]. Tumor hypoxia represents a serious obstacle to successful chemotherapy and is associated with poor prognosis in cancer patients [reviewed in [2]]. The hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is a heterodimer composed of two subunits, namely, a constitutively expressed β-subunit and an oxygen-dependent α-subunit. In normoxia, HIF-α undergoes rapid proteasomal degradation mediated by prolyl hydroxylases. Conversely, owing to low oxygen concentration, prolyl hydroxylases are inactivated, leading to the stabilization and translocation of HIF-α to the cell nucleus, where it heterodimerizes with HIF-β to form the functional transcription factor HIF. HIF recognizes and binds to the hypoxia-responsive elements (HRE) of target genes and triggers their transcription [reviewed in [3]]. HIF target genes, such as solute carrier family 2, facilitated glucose transporter member 1 (GLUT1, gene SLC2A1), carbonic anhydrase 9 (CAIX, gene CA9), and POU domain, class 5, transcription factor 1 (Oct-4, gene POU5F1), are involved in the control of the metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells, regulation of pH, and maintenance of stem cell pluripotency, respectively [4], [5], [6]. In addition, the promoter region of the ABCG2 gene encoding the BCRP transport protein providing drug efflux from cancer cells contains HREs for both HIF isoforms, namely, HIF-1α and HIF-2α [7], [8]. Thus, the hypoxic microenvironment participates in the chemoresistance and aggressiveness of cancer cells by a wide range of molecular mechanisms, which eventually cause the failure of any traditional therapeutic approaches.

The cancer stem-like cell (CSC) concept has helped in explaining the failure of oncotherapy, which is often insufficient to eradicate this resistant subpopulation of cancer cells, which are believed to be concentrated in the highly hypoxic zone of the tumor mass [9]. The increased BCRP-mediated drug efflux activity has become the basis of a flow cytometry method called side population (SP) analysis. The presence of SP cells in the tumor may be an indicator of its resistance and it is also used as a marker of CSCs [10]. Targeting BCRP activity is still a promising strategy for increasing the effectiveness of chemotherapy. However, many inhibitors of ABC transport proteins, including BCRP, did not show the desired effect but were toxic [reviewed in [11]]. Thus, there is an effort to find another inhibitor, preferably of natural origin, to improve chemotherapy effectiveness without adverse side effects. Such a natural substance with a promising potential is hypericin, a secondary metabolite synthesized by a few plants of the genus Hypericum, such as St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum L.). Currently, the photocytotoxic effects of hypericin have been clinically tested in photodynamic therapy and diagnosis [12], [13], and several studies have shown that hypericin is capable of antitumor activity even without light activation. Hypericin “in the dark,” in association with its potential application in oncotherapy, acts as the following: a) an inductor of apoptosis via its interaction with anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2 [14], b) an angiogenesis inhibitor, as demonstrated by the inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation, extracellular matrix (ECM) degrading urokinase, and migration and invasion of endothelial cells [15], c) a growth inhibitor of metastatic cancer cells in vitro and in vivo (clinically tested hypericin also reduced the tumor mass) [16], [17], [18], d) a modulator of adhesion proteins [19], and e) a substrate of the BCRP transport protein reducing the size of the SP population presumably via competitive inhibition of BCRP [20], [21], [22]. However, these conclusions might be diverse if they would be obtained under hypoxic conditions, as indicated by hypericin involvement in the degradation of the key hypoxic regulator HIF-1α [23]. Whether hypericin can reduce or modulate SP fraction in this way(s) even under hypoxic demand and can increase the efficacy of chemotherapy or affect the metastatic potential of this subpopulation remains unclear.

Here, we investigated the bioactive effects of hypericin on the modulation of the SP phenotype under hypoxic conditions (1 % O2) that more closely resemble the microenvironment of solid tumors. Concretely, we verified whether hypericin could reduce the size of the SP population even in cancer cells cultured under hypoxia, which could positively affect tumor sensitivity to simultaneous chemotherapy. Alternatively, hypoxia could be a contraindication to hypericin application and could reduce its accumulation in hypoxic cancer cells as hypericin itself is a preferential substrate of BCRP. Furthermore, using proteomic analysis, we analyzed the differences between SP and non-SP cells cultured in normoxia and hypoxia, and simultaneously, differences in specific proteins with significantly changed levels due to hypoxia were subjected to a more detailed analysis as potential targets of hypericin.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell lines and cultivation conditions

Human lung adenocarcinoma A549, colon adenocarcinoma HT-29, and ovarian carcinoma cell line A2780 were used in particular experiments and were all obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). For routine cultivation, cells were cultivated under standard conditions in an incubator at 37 ℃, 5 % CO2, and 95 % humidity in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biosera, Nuaillé, France) and antibiotics (1 % antibiotic–antimycotic 100 × and 50 µg mL−1 gentamycin, Biosera).

2.2. Experimental design

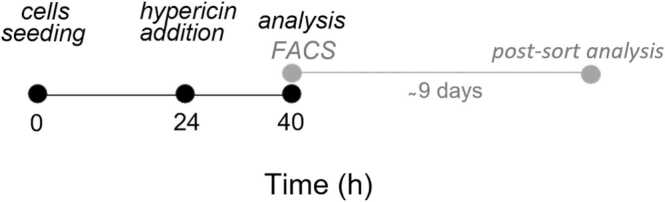

For the purposes of the experiments described below, the cells were cultivated right after seeding (0 in time schedule; Fig. 1) in an O2 Control InVitro Glove Box (Coy Laboratory Products, Inc., Grass Lake, MI, USA), allowing continuous oxygen control either in a hypoxic chamber at 1 % O2, 5 % CO2, 94 % N2, and 37 ℃ or in a normoxic chamber at 20 % O2, 5 % CO2, 75 % N2, and 37 ℃.

Fig. 1.

Time schedule of appropriate experiments.

In some experiments, hypoxia was also induced chemically using cobalt chloride (CoCl2; CAS no.: 7791-13-1; Sigma-Aldrich). For this purpose, cells were cultured in normoxic conditions 20 h prior to CoCl2 (100 μM) treatment, and subsequent western blot and SP analysis were performed after another 24 h.

Time schedule (Fig. 1) represents the basic timeline for experiments, where cells were analyzed 16 h after hypericin (CAS no.: 548-04-9; HPLC grade from AppliChem GmbH, Germany) addition: the intracellular accumulation of hypericin, cell harvesting for western blot or RT-qPCR analysis, flow cytometry analysis, and sorting of SP and non-SP cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and subsequent (postsorting) analyses, unless otherwise noted.

All experiments employing hypericin were performed in dark conditions to prevent its photoactivation.

2.3. Intracellular accumulation of hypericin

For the comparison of the impact of oxygenation on intracellular hypericin (0.1, 0.5, 1, or 5 µM) content, cells cultivated under normoxia or hypoxia were harvested with trypsin (according to time schedule; Fig. 1) and centrifuged (850 rpm, 5 min, and 4 °C). After rinsing the pellet with ice-cold PBS, the cells were centrifuged again (850 rpm, 5 min, and 4 °C) and the pellet was transferred to cytometric tubes in ice-cold PBS. Intracellular accumulation of hypericin was analyzed (1 × 104 cells per sample) using a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA). Evaluation was performed using the FlowJo software (TreeStar Inc., Ashland, OR, USA) as the ratio of the median of the hypericin fluorescence to the autofluorescence of a normoxic or hypoxic control in the FL-2 channel (585/42 nm bandpass filter) upon blue laser excitation (488 nm).

2.4. Western blot analysis

To analyze the effect of hypoxia and/or hypericin (0.1, 0.5, 1, or 5 µM) on the protein levels of BCRP, HIF-1α and HIF-2α, cells were harvested by scraping on ice and centrifuged (2500 rpm, 10 min, and 4 ℃). The pellet was washed with ice-cold PBS and cells were then lysed on ice for 15 min in lysis solution (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 1 % SDS; 10 % glycerol) supplemented with HALT™ Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (10 µL mL−1) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (40 µL mL−1) (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell lysates were sonicated on ice and centrifuged (12,000 rpm, 10 min, and 4 ℃). Protein concentration was determined by the Lowry method using a DC™ Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA), and samples were diluted to equal concentrations. Samples (30 μg proteins each) were separated on an 8 % SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane. After blocking with 5 % milk or 5 % BSA, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 ℃ with the following primary antibodies: BCRP (1:400; sc-58222; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), HIF-1α (1:500; 610959; BD Biosciences), HIF-2α (1:1000; 7096; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and β-actin (1:5000; A5441; Sigma-Aldrich). Subsequently, appropriate horseradish peroxidase-bound secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP, 1:5000; goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP, 1:5000, both from Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added to the membranes. After washing the membranes, the reactivity of the antibodies was visualized by a chemiluminescent kit Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and captured on X-ray films (AGFA, Gevaert N.V., Belgium). Protein densitometry was evaluated using ImageLab software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). β-actin was used as a loading control.

2.5. Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

The mRNA level of the studied genes was determined by RT-qPCR with the SYBR Green detection of the final product. The obtained Ct values were used to calculate the relative quantity of the studied mRNAs according to the standard curve (prepared as a serial dilution of a mixture of samples with the highest expected expression level). Total RNA for the analysis was extracted from A549 and HT-29 cells with TRI-Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and purity of isolated RNA were measured using a NanoDrop OneC spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA integrity was determined by electrophoresis at nondenaturing 1 % agarose gel and staining with loading dye (SYBR™ Gold; Invitrogen, Eugene, Oregon, USA) in 1 × Tris-Acetate-EDTA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Then, 2000 ng of the RNA from each sample was used for reverse transcription using a RevertAid™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and random hexamer/anchored oligodT primer. The cDNA was diluted, and 20 ng of RNA/cDNA was subjected to RT-qPCR analysis using an Xceed qPCR SYBR Green Lo-ROX kit (IAB, Prague, Czech Republic) with appropriate primers (Appendix Table A1). RT-qPCR was performed on a CFX96 Real-Time System, C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The resulting relative mRNA levels were normalized to the reference gene coding phosphomannomutase 1 (PMM1) (melt peaks of genes are provided in Appendix Fig. A1).

2.6. SP assay and FACS and subsequent analyses

SP analysis was performed according to a standard protocol with slight modifications, as previously described [22]. Cells preincubated with hypericin (0.1, 0.5, 1, or 5 µM) were harvested with trypsin and resuspended in SP buffer (HBSS, 2 mM HEPES, 2 % FBS, pH 7.3). Cells (1 × 106 mL−1) were incubated with Hoechst 33342 dye (5 μg mL−1, CAS no.: 875756-97-1, Sigma-Aldrich) in SP buffer for 90 min at 37 °C on a ThermoMixer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) with intermittent shaking (cycling 300 rpm for 15 s and resting for 45 s). The BCRP inhibitor Ko143 (50 µM, CAS no.: 461054-93-3, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as a negative control for gate determination. Cells were preincubated with Ko143 for 15 min prior to Hoechst 33342 addition. Just prior to the measurement itself or by FACS sorting with a BD FACSAria II SORP (BD Biosciences) (the configuration settings are provided in Appendix Table A2), cells were centrifuged (850 rpm, 5 min, and 4 °C) and pellets were resuspended in ice-cold SP buffer supplemented with propidium iodide (PI, 1 µg mL−1, CAS no.: 25535-16-4, Sigma-Aldrich) to separate dead cells. For FACS sorting, cells were processed aseptically and filtered through cell strainers with 70 µm pores (pluriSelect Life Science, Leipzig, Germany) to obtain single-cell suspension. A 100 µm nozzle was used for sorting.

2.6.1. Migration assay

A549 cells were preincubated with 1 µM hypericin in normoxia or hypoxia to examine their impact on the migratory ability of SP and non-SP subpopulations. After FACS sorting of SP and non-SP cells into 96-well plates (8000 cells per well), cells were incubated for several days for adherence and to obtain 100 % confluence. Three days before wound formation, the medium was replaced with low-serum (1 % FBS) medium to inhibit proliferation. The wound was created in a confluent layer of cells with a IncuCyte® WoundMaker (Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the closure of the wound was evaluated using the IncuCyte™ ZOOM (Essen BioScience) automated software every 3 h for a total of 4 days.

2.6.2. Automatic cell cloning assay

For determining the clonogenic capacity of SP and non-SP cells, A549 cells were preincubated with 1 µM hypericin in normoxia or hypoxia and sorted by FACS as described previously [22], [24]. Single SP or non-SP cells were sorted into 96-well plates with a fresh medium. Nine days later, cells were visualized by IncuCyte™ ZOOM and clonogenic ability was evaluated using resazurin reduction assay. Briefly, cells were incubated with resazurin (7-hydroxy-3H-phenoxazin-3-one-10-oxide, 30 µg mL−1, CAS no.: 62758-13-8, Sigma-Aldrich) in a complete medium for at least 1 h at 37 °C. Resazurin was reduced to its fluorescent derivative resofurin only in viable, metabolic active cells. Resofurin fluorescence (excitation/emission 544/590 nm) was further measured using a BMG FLUOstar Optima device (BMG Labtechnologies GmbH, Germany). The clonogenic ability of A549 cells was calculated as a ratio of wells with fluorescence higher than 1.25 × the blank value to an overall number of seeded wells.

2.6.3. Proteomic analysis of SP and non-SP cells

To compare the molecular differences between SP and non-SP cells at the protein level, mass spectrometry analysis of whole SP and non-SP proteomes was performed. Briefly, SP and non-SP cells separated from the A549 cell line cultured in normoxia or hypoxia were sorted by FACS (minimum, 200,000 cells), with each sample group in hexaplicates. The purity of the FACS sorting was back-verified (Appendix Fig. A2). Cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and lysed in SDT buffer (4 % SDS, 0.1 % DTT in Tris-HCl, pH 7.6) and homogenized for 2 h at 95 °C. Samples were desalted, concentrated, and trypsinized by standard procedures on 30 kDa FASP filters. The obtained peptides were analyzed on a Q Exactive HF-X with an Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were evaluated using MaxQuant software (version 1.6.14.0) against the UniProtKB database (taxonomy: Homo sapiens (9606) dated 18/12/2019). The list of identified protein groups was subsequently processed in the KNIME analytical interface using OmicsWorkflows (version 0.6a; available at https://github.com/OmicsWorkflows/KNIME_workflows). Data were normalized using the LoessF method, and individual groups were compared with each other using the LIMMA and Benjamini–Hochberg methods.

On the basis of the analysis of the significantly increased or decreased proteins, the pathways in which these groups of proteins were involved were identified using the freely available Reactome database (http://reactome.org).

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [25] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD038740.

2.7. MTT assay

For the determination of the half maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of mitoxantrone dihydrochloride (MTX; CAS no.: 70476-82-3; HPLC grade from Sigma-Aldrich), MTT assay was performed as previously reported [26]. Briefly, 40 h after cell seeding and cultivation in normoxia and hypoxia, MTX was added to cells for another 24 or 48 h. IC50 values were evaluated based on the changes in the metabolic activity of A549 cells and extrapolated from a dose–response fit to the metabolic activity data using OriginPro 8.5.0 SR1 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA).

2.8. Phosphatidylserine externalization analysis

Phosphatidylserine externalization analysis was used to evaluate the impact of hypericin pretreatment on MTX-induced cell death. Briefly, 24 h after seeding, normoxic and hypoxic A549 cells were preincubated with hypericin (0.5 µM) for 16 h. Subsequently, MTX (according to the calculated IC50 values) was added to cells for another 24 or 48 h until analysis. Cells (2 × 105 cells per sample) were centrifuged (850 rpm, 10 min, and room temperature) and then stained with Annexin V-FITC in 1 × binding buffer (BD Pharmingen™ FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I, BD Biosciences) at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. Prior to analysis by BD FACSCalibur, cells were stained with PI (1 µg mL−1). Fluorescence of Annexin V-FITC was detected in the FL-1 channel (530/30 nm bandpass filter) and PI fluorescence was detected in the FL-3 channel (670 nm longpass filter), both upon blue laser excitation (488 nm) (Appendix Table A2). FlowJo software was used for the evaluation of the results.

2.9. Statistical analysis

The results were presented as the mean values ± standard deviation (SD) or standard error of the mean (SEM) of at least two independent experiments. The data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test or t-test. Significance levels are indicated in the legend of each figure.

3. Results

3.1. Hypericin effectively accumulates in cancer cells despite hypoxia and causes a decrease in HIFs

The effect of hypoxia on intracellular hypericin accumulation in cancer cells was measured by flow cytometry. Results showed that hypericin accumulated in hypoxic A549 and HT-29 cells to the same extent as that in normoxic cells (Fig. 2A and 2C). The only difference was noticed in A2780 cells incubated with 0.5 and 1 μM hypericin, where hypoxia moderately reduced the intracellular hypericin content compared to normoxia (Fig. 2B). The results also confirmed that the rate of hypericin accumulation in the cells was dose dependent, as expected.

Fig. 2.

Intracellular accumulation of hypericin. Hypericin (0.1, 0.5, 1 and 5 µM) was added to normoxic and hypoxic cells 24 h after seeding and the intracellular accumulation of hypericin was analyzed 16 h after addition. Impact of normoxia and hypoxia on hypericin accumulation in (A) A549, (B) A2780, and (C) HT-29 cells measured by flow cytometry as the ratio of the median hypericin fluorescence to the autofluorescence of a given control. The results are expressed as the mean values ± SD of three independent experiments. The experimental groups treated with various concentrations of hypericin in normoxia or hypoxia were compared with the untreated normoxic control group (○ p < 0.05, ○○ p < 0.01, ○○○ p < 0.001) or hypoxic control group (• p < 0.05, ••• p < 0.001), respectively, by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. Changes between normoxia and hypoxia were compared within each experimental group by t-test (* p < 0.05, nonsignificant (ns); statistics above the gray line).

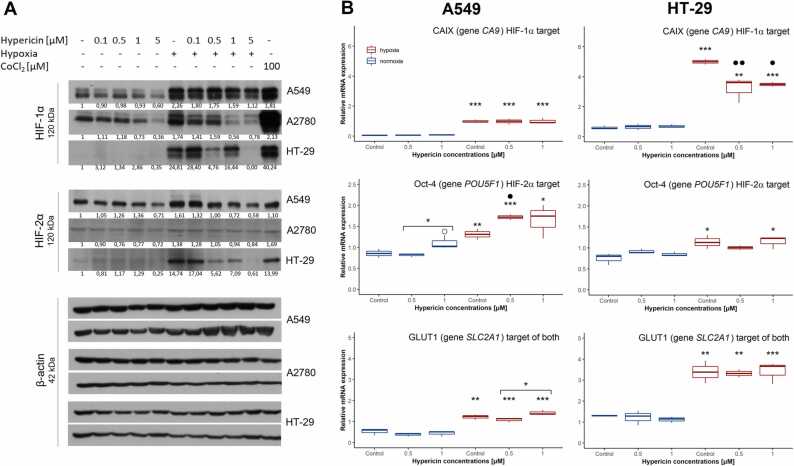

Next, we showed that hypericin caused a decrease in HIF-1α and HIF-2α in hypoxic cells when compared to the expected high levels of hypoxic controls in all three cell lines (Fig. 3A). Under normoxia, hypericin also decreased the basal levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in all cell lines. However, under both experimental conditions, it was not a strictly dose-dependent decrease, but the most significant reduction occurred at the highest concentration used (5 µM hypericin) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Changes in the protein level and transcriptional activity of HIF-1α and HIF-2α induced by hypoxia and/or hypericin application. Hypericin was added to normoxic and hypoxic cells 24 h after seeding. Cells were harvested for western blot or RT-qPCR 16 h after hypericin addition. (A) Effect of hypericin (0.1, 0.5, 1 and 5 µM) in normoxia and hypoxia on protein levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in A549, A2780, and HT-29 cells, respectively, analyzed by western blot. β-actin was used as a loading control. One representative experiment of at least two is presented. (B) Effect of hypericin (0.5 and 1 µM) in normoxia and hypoxia on the transcriptional activity of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in A549 and HT-29 cells verified by changes in the mRNA levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α target genes CA9, POU5F1, and SLC2A1, respectively. The normalized relative mRNA levels of analyzed genes were quantified by real-time RT-qPCR, and PMMI was used as a reference gene. The results are presented in boxplots of at least two independent experiments. Hypoxic groups were compared with appropriate normoxic groups by t-test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001), and simultaneously, experimental groups treated with hypericin in normoxia or hypoxia were compared with the appropriate untreated normoxic control (○ p < 0.05) or hypoxic control (• p < 0.05, •• p < 0.01), respectively, or were compared against each other by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (* above line p < 0.05).

To verify the impact of hypericin-mediated decrease in HIF levels on their transcriptional activity, we further analyzed changes in the mRNA levels of specific and validated target genes of HIF-1α, HIF-2α, or both HIFs, namely, CA9, POU5F1, or SLC2A1, respectively. For these experiments, the medium concentrations of hypericin (0.5 and 1 µM) were used based on a clear trend of decreasing HIF protein levels in hypoxia. The results did not affirm hypericin potency to fully inhibit the transcriptional activity of HIFs, when no decrease in CA9, SLC2A1, or POU5F1 mRNA levels was observed in hypericin-treated A549 cells (Fig. 3B, left panel). On the contrary, we noticed a significant increase in POU5F1 expression in hypericin-treated A549 cells that did not correlate with a decreasing HIF-2α level. On the other hand, in HT-29 cells, we demonstrated an unequivocal decrease in CA9 expression in hypericin-treated hypoxic cells (Fig. 3B, right panel), which agreed with the decreased HIF-1α level. However, this trend was not confirmed for the HIF-2α target, POU5F1, nor for the common HIF target, SLC2A1. Thus, although hypericin contributes to the degradation of HIF proteins in cancer cells, especially under hypoxia, HIF-1α or HIF-2α level is probably still sufficient to trigger the transcription of some of their targets.

3.2. Hypoxia and hypericin decrease the SP fraction presumably by two distinct mechanisms

Because hypericin was found to be a potential competitive inhibitor of the BCRP transport protein reducing the percentage of SP cells under normoxia [22], we intended to verify whether hypericin could affect the size of the SP population even in hypoxia.

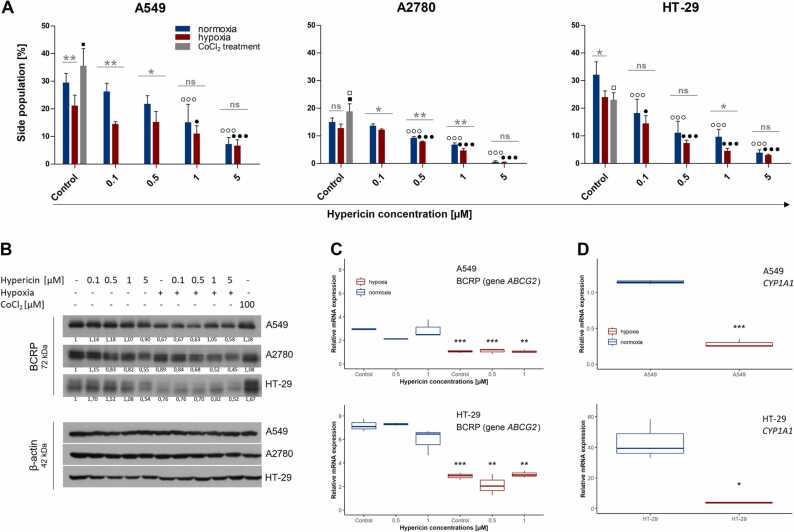

First, we observed an unexpected decrease in the SP population due to hypoxia in all three cell lines (Fig. 4A and Appendix Fig. A3), particularly in the A549 and HT-29 cells, where hypoxia significantly diminished the percentage of SP population from 29.5% ± 2.9 % to 21.2% ± 3.3 % and from 32.1 % ± 3.8 % to 24.0 % ± 1.9 %, respectively. Similarly, in the A2780 cell line, the SP size was reduced but only slightly from 15.0 % ± 1.2 % to 12.8 % ± 1.2 %. In line with this, we noticed a hypoxia-induced decrease in BCRP protein level in all three cell lines (Fig. 4B, first versus sixth column). This decrease was caused by the inhibited transcription of the BCRP-coding gene, ABCG2, as demonstrated on A549 and HT-29 cell lines (Fig. 4C, control groups). Notably, treatment of cells with CoCl2 (100 µM), a known chemical inducer of HIF-1α, increased the protein levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α similarly to 1 % O2 (Fig. 3A, last column). However, contrary to 1 % O2, CoCl2 caused a slight increase in BCRP protein in all cell lines (Fig. 4B, last column) and in SP fraction (Fig. 4A and Appendix Fig. A3), except HT-29 cells. This suggests that another transcriptional factor besides HIFs might be involved in the regulation of ABCG2 expression under hypoxia. One of the possible candidates is the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, AhR, which is known to positively regulate ABCG2 [27], and the antagonistic crosstalk between AhR and HIF signaling via HIF-1β was suggested [28]. Indeed, we observed a hypoxia-induced decrease in CYP1A1 mRNA level, a known AhR target [29], in A549 and HT-29 cells under 1 % O2 (Fig. 4D), which correlated with a reduction in ABCG2 expression level. This might suggest the inhibited transcriptional activity of AhR under hypoxia. However, the exact mechanism of BCRP decrease under physiological hypoxia should be further investigated.

Fig. 4.

Effect of hypoxia with/without hypericin on the size of the SP population, protein and mRNA levels of the BCRP transport protein, and expression of CYP1A1 in cancer cell lines. Hypericin was added to normoxic and hypoxic cells 24 h after seeding and SP analysis and cell harvesting for western blot and RT-qPCR were proceeded 16 h after hypericin addition. (A) The sizes of the SP populations in A549, A2780, and HT-29 cells analyzed by flow cytometry. The results are expressed as the mean values ± SD of at least two independent experiments. Experimental groups treated with hypericin (0.1, 0.5, 1, and 5 µM) in normoxia or hypoxia were compared with untreated normoxic control group (○○○ p < 0.001) or hypoxic control group (• p < 0.05, ••• p < 0.001), respectively, by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. Simultaneously, changes between normoxia and hypoxia were compared within each experimental group by t-test (statistics above the gray line; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, nonsignificant (ns)). CoCl2 (100 µM) treatment was compared to normoxic control (□ p < 0.05) and hypoxic control (■ p < 0.05) by t-test. (B) Changes in protein level of BCRP mediated by hypoxia and/or hypericin (0.1, 0.5, 1, and 5 µM) analyzed by western blot analysis in A549, A2780, and HT-29 cells. CoCl2 was used as a control for hypoxic experimental conditions. β-actin was used as a loading control. One representative experiment of at least two is presented. (C) Results of RT-qPCR showing hypericin (0.5 and 1 µM)-mediated changes in ABCG2 expression in normoxic and hypoxic A549 and HT-29 cells. PMMI was used as a reference gene, and the results are expressed in boxplots of at least two independent experiments. Hypoxic groups were compared with appropriate normoxic groups by t-test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001). (D) RT-qPCR analysis of the AhR target gene, CYP1A1, in normoxic and hypoxic A549 and HT-29 cells. PMMI was used as a reference gene, and the results are expressed in boxplots of three independent experiments. Hypoxic groups were compared with appropriate normoxic groups by t-test (* p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001).

Furthermore, addressing the impact of hypericin on SP fraction in hypoxic cells, we noticed a significant reduction in the SP population that was already diminished by hypoxia, and this drop was dose dependent (Fig. 4A and Appendix Fig. A3).

Hypericin also affected the BCRP protein level in whole populations of all three cell lines, but no uniform trend was observed between cell lines or among different hypericin concentrations. The only unequivocal effect was noticed with 5 μM hypericin in normoxia and hypoxia, when the decrease in BCRP level was observed in all cell lines (Fig. 4B). In addition, similar results were observed in the analysis of ABCG2 gene expression, when its downregulation was only a result of hypoxia, i.e., hypericin (0.5 and 1 µM) did not affect ABCG2 expression either in normoxia or hypoxia (Fig. 4C). Thus, our data may indicate that the observed decrease in SP population is a result of a coaction of reducing ABCG2 expression by hypoxia and previously predicted competitive inhibition of BCRP by hypericin [20], [22].

3.3. Decrease in SP population in A549 cells caused by hypoxia and/or hypericin did not translate into the increased efficacy of simultaneously administered chemotherapy

On the basis of our abovementioned results, we intended to verify if a decrease in SP fraction would reflect into the potentiation of MTX efficiency. MTX was chosen as a model chemotherapeutic because it is a well-known BCRP substrate [30]. Changes in MTX potency in A549 cells in different conditions were assessed by inspecting phosphatidylserine externalization and cytoplasmic membrane integrity. However, despite the proven reduction in BCRP/SP under hypoxia, we observed that MTX IC50 concentration values were twice higher in hypoxia than in normoxia at 48 h (Appendix Table A3).

Focusing on the differences between the effects of MTX alone and its combination with hypericin, we did not observe a uniform trend on the onset and course of cell death or cell survival. However, some differences were noted depending on the time and oxygenation. At 24 h in normoxia, the portion of cells undergoing necrosis increased significantly in the combined group compared to MTX alone at the expense of apoptotic fraction, indicating that necrosis was switched on (Appendix Fig. A4A). Nonetheless, these effects were lacking in hypoxia (Appendix Fig. A4B) and even turned completely at 48 h in normoxia, when the proportion of necrotic cells decreased in the combined group (Appendix Fig. A4C). Furthermore, prolonged exposure of A549 cells to hypericin and MTX under hypoxia probably led to their adaptation because combined treatment was less devastating for cells compared to MTX alone, as was demonstrated by an increase in the proportion of live cells and a drop in population undergoing secondary necrosis (Appendix Fig. A4D). In summary, hypericin is unlikely to potentiate the efficacy of chemotherapy through competitive inhibition of BCRP in hypoxic cancer cells.

3.4. Proteomic analysis revealed that non-SP cells may represent the leading subpopulation undergoing epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and hypoxia promotes a more aggressive phenotype of cancer cells due to the increase in proteins associated with the reorganization of ECM

Because hypoxia itself is a pleiotropic factor affecting a plethora of cellular processes, we employed mass spectrometry analysis to get the complex picture of its action on cancer cells with respect to their SP/non-SP phenotype. Moreover, recognition of other molecules besides BCRP, which are significantly changed under hypoxia, could serve as potential hypericin targets. Indeed, we compared the whole proteomes of normoxic and hypoxic SP and non-SP populations separated from the A549 cell line. In total, 5 326 protein groups were identified. To monitor changes in protein levels between experimental sample groups (SP in normoxia, non-SP in normoxia, SP in hypoxia, and non-SP in hypoxia), protein group intensities were normalized and Log2FC values between sample groups were calculated for each protein group. To consider the compared values significant, the p-value for the difference between the sample groups was set lower than 0.01 and the threshold for the changed regulation was set as Log2FC > + 0.9 for significantly increased proteins and Log2FC < − 0.9 for significantly decreased proteins. To analyze the overall impact of hypoxia compared to normoxia, the criteria were adjusted, i.e., Log2FC was set to + 1 or − 1, respectively, with the adj. p-value lower than 0.01. Only those proteins that were detected in at least half of the replicates were included in the analysis.

First, we identified 14 significantly increased proteins and 21 significantly decreased proteins in normoxic SP versus normoxic non-SP cells (the full list of proteins is presented in Table 1) (Fig. 5A and 5C) and 15 significantly increased and 20 significantly decreased proteins in hypoxic SP cells compared to hypoxic non-SP cells (the full list of proteins is presented in Table 2) (Fig. 5B and 5C). Among the proteins that were globally elevated in SP cells (i.e., increased in both normoxic and hypoxic SP cells) (Fig. 5C), we identified the BCRP, which also confirms the accuracy of the separation of the SP and non-SP populations. The level of BCRP in the SP population was significantly higher compared to non-SP (4.36-fold in normoxia (p = 0.00002) and 2.19-fold in hypoxia (p = 0.006)). The other significantly augmented protein in SP cells was hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, a cytoplasmic protein and member of the mevalonate pathway, which was also shown to be overexpressed in breast cancer CSC-enriched cell subpopulations [31]. Conversely, in SP cells, we found two significantly lessened proteins compared to non-SP cells (Fig. 5C), namely, 5-nucleotidase (NT5E) and nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (NNMT). Both proteins were already associated with the cancer cell metastasis process as the level of NNMT or NT5E positively correlated with cell migration and invasion [32], [33].

Table 1.

List of significantly changed protein levels in SP compared to non-SP population in normoxia.

| Accession | Gene name | List of significantly increased proteins of SP versus non-SP in normoxia |

Log2FC | FC | pValue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q9Y487 | ATP6V0A2 | V-type proton ATPase 116 kDa subunit a isoform 2 | 2,24 | 4,71 | 0,001 |

| Q9UNQ0 | ABCG2 | Broad substrate specificity ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2 | 2,13 | 4,36 | 0,000 |

| P25815 | S100P | Protein S100-P | 1,69 | 3,22 | 0,000 |

| P20839 | IMPDH1 | Inosine-5-monophosphate dehydrogenase 1 | 1,35 | 2,54 | 0,004 |

| Q9HBI1 | PARVB | Beta-parvin | 1,29 | 2,44 | 0,003 |

| O14936 | CASK | Peripheral plasma membrane protein CASK | 1,20 | 2,30 | 0,009 |

| P51843 | NR0B1 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 0 group B member 1 | 1,17 | 2,25 | 0,005 |

| Q9UQN3 | CHMP2B | Charged multivesicular body protein 2b | 1,13 | 2,19 | 0,004 |

| Q96MG7 | NSMCE3 | Non-structural maintenance of chromosomes element 3 homolog | 1,05 | 2,07 | 0,009 |

| Q7L273 | KCTD9 | BTB/POZ domain-containing protein KCTD9 | 1,03 | 2,04 | 0,006 |

| Q6PI78 | TMEM65 | Transmembrane protein 65 | 0,98 | 1,97 | 0,002 |

| P56282 | POLE2 | DNA polymerase epsilon subunit 2 | 0,98 | 1,97 | 0,003 |

| Q01581 | HMGCS1 | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, cytoplasmic | 0,97 | 1,96 | 0,000 |

| P61962 | DCAF7 | DDB1- and CUL4-associated factor 7 | 0,95 | 1,93 | 0,007 |

| Q9NRL2 | BAZ1A | Bromodomain adjacent to zinc finger domain protein 1A | -3,12 | 0,11 | 0,010 |

| Q14807 | KIF22 | Kinesin-like protein KIF22 | -2,21 | 0,22 | 0,000 |

| Q9NQW6 | ANLN | Anillin | -1,55 | 0,34 | 0,001 |

| P21589 | NT5E | 5-nucleotidase | -1,54 | 0,34 | 0,008 |

| Q8N3V7 | SYNPO | Synaptopodin | -1,47 | 0,36 | 0,001 |

| P40261 | NNMT | Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase | -1,44 | 0,37 | 0,000 |

| Q9UKS6 | PACSIN3 | Protein kinase C and casein kinase substrate in neurons protein 3 | -1,27 | 0,41 | 0,010 |

| A6NIH7 | UNC119B | Protein unc-119 homolog B | -1,19 | 0,44 | 0,005 |

| O60488 | ACSL4 | Long-chain-fatty-acid--CoA ligase 4 | -1,18 | 0,44 | 0,009 |

| P21980 | TGM2 | Protein-glutamine gamma-glutamyltransferase 2 | -1,18 | 0,44 | 0,005 |

| Q86XL3 | ANKLE2 | Ankyrin repeat and LEM domain-containing protein 2 | -1,13 | 0,46 | 0,001 |

| Q9HAD4 | WDR41 | WD repeat-containing protein 41 | -1,07 | 0,48 | 0,004 |

| Q8WW59 | SPRYD4 | SPRY domain-containing protein 4 | -1,07 | 0,48 | 0,003 |

| Q9UHR5 | SAP30BP | SAP30-binding protein | -1,03 | 0,49 | 0,006 |

| P11169 | SLC2A3 | Solute carrier family 2, facilitated glucose transporter member 3 | -0,99 | 0,50 | 0,009 |

| Q9BQ70 | TCF25 | Transcription factor 25 | -0,95 | 0,52 | 0,009 |

| Q13423 | NNT | NAD(P) transhydrogenase, mitochondrial (MTCH) | -0,95 | 0,52 | 0,005 |

| Q13642 | FHL1 | Four and a half LIM domains protein 1 | -0,94 | 0,52 | 0,002 |

| Q8WX93 | PALLD | Palladin | -0,94 | 0,52 | 0,007 |

| Q9UJX2 | CDC23 | Cell division cycle protein 23 homolog | -0,91 | 0,53 | 0,004 |

| Q8IWB1 | ITPRIP | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-interacting protein | -0,90 | 0,53 | 0,006 |

Fig. 5.

Comparison of whole proteomes of SP and non-SP cells and their changes under hypoxia. (A, B) Volcano plots showing the number of significantly changed proteins in normoxic (A) or hypoxic (B) SP versus non-SP cells. Significance was set to a p-value < 0.01, and the threshold for altered regulation was set as Log2FC > ± 0.9. (C) Venn diagram illustrating the distribution and the number of proteins significantly increased or decreased in SP cells compared to non-SP cells under normoxia and hypoxia. Significance was set the same as that in A and B. Compared to A and B, the protein numbers in C are purged of those proteins that were detected in less than half of the replicates included in the analysis.

Table 2.

List of significantly changed protein levels in SP compared to non-SP population in hypoxia.

| Accession | Gene name | List of significantly increased proteins of SP versus non-SP in hypoxia |

Log2FC | FC | pValue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q9NU22 | MDN1 | Midasin | 2,14 | 4,40 | 0,007 |

| O95810 | CAVIN2 | Caveolae-associated protein 2 | 1,88 | 3,69 | 0,003 |

| Q53T59 | HS1BP3 | HCLS1-binding protein 3 | 1,66 | 3,17 | 0,001 |

| Q1ED39 | KNOP1 | Lysine-rich nucleolar protein 1 | 1,52 | 2,86 | 0,008 |

| Q01581 | HMGCS1 | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, cytoplasmic | 1,37 | 2,58 | 0,000 |

| P35680 | HNF1B | Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1-beta | 1,23 | 2,35 | 0,000 |

| Q9H008 | LHPP | Phospholysine phosphohistidine inorganic pyrophosphate phosphatase | 1,20 | 2,29 | 0,007 |

| Q9UNQ0 | ABCG2 | Broad substrate specificity ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2 | 1,13 | 2,19 | 0,006 |

| O60934 | NBN | Nibrin | 1,06 | 2,08 | 0,002 |

| Q8WUX9 | CHMP7 | Charged multivesicular body protein 7 | 1,04 | 2,05 | 0,004 |

| Q9Y5B0 | CTDP1 | RNA polymerase II subunit A C-terminal domain phosphatase | 1,01 | 2,02 | 0,008 |

| Q2NKX8 | ERCC6L | DNA excision repair protein ERCC-6-like | 1,01 | 2,01 | 0,006 |

| Q9NXW2 | DNAJB12 | DnaJ homolog subfamily B member 12 | 1,00 | 2,00 | 0,005 |

| Q96CP7 | TLCD1 | TLC domain-containing protein 1 | 0,96 | 1,94 | 0,003 |

| P56378 | ATP5MPL | ATP synthase subunit ATP5MPL, MTCH | 0,92 | 1,89 | 0,001 |

| Q96GD4 | AURKB | Aurora kinase B | -2,04 | 0,24 | 0,004 |

| P19022 | CDH2 | Cadherin-2 | -1,69 | 0,31 | 0,000 |

| P21589 | NT5E | 5-nucleotidase | -1,67 | 0,31 | 0,001 |

| Q9H0X4 | FAM234A | Protein FAM234A | -1,65 | 0,32 | 0,004 |

| Q658P3 | STEAP3 | Metalloreductase STEAP3 | -1,57 | 0,34 | 0,004 |

| Q02252 | ALDH6A1 | Methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase [acylating], MTCH | -1,56 | 0,34 | 0,002 |

| P85037 | FOXK1 | Forkhead box protein K1 | -1,54 | 0,35 | 0,002 |

| P07711 | CTSL | Cathepsin L1 | -1,47 | 0,36 | 0,007 |

| O00499 | BIN1 | Myc box-dependent-interacting protein 1 | -1,45 | 0,37 | 0,006 |

| O94880 | PHF14 | PHD finger protein 14 | -1,43 | 0,37 | 0,001 |

| Q9NPH2 | ISYNA1 | Inositol-3-phosphate synthase 1 | -1,31 | 0,40 | 0,001 |

| Q9UHB6 | LIMA1 | LIM domain and actin-binding protein 1 | -1,31 | 0,40 | 0,001 |

| Q9NUQ2 | AGPAT5 | 1-acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase epsilon | -1,17 | 0,45 | 0,004 |

| Q9UKV8 | AGO2 | Protein argonaute-2 | -1,17 | 0,45 | 0,003 |

| P16401 | H1–5 | Histone H1.5 | -1,16 | 0,45 | 0,002 |

| P40261 | NNMT | Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase | -1,10 | 0,47 | 0,001 |

| P28347 | TEAD1 | Transcriptional enhancer factor TEF-1 | -1,05 | 0,48 | 0,002 |

| P35226 | BMI1 | Polycomb complex protein BMI-1 | -1,05 | 0,48 | 0,004 |

| Q9P0K7 | RAI14 | Ankycorbin | -1,01 | 0,50 | 0,001 |

| Q9UBG0 | MRC2 | C-type mannose receptor 2 | -0,96 | 0,51 | 0,003 |

Next, we looked particularly at the differences in the proteomes of SP and non-SP cells under hypoxia. Besides BCRP, the comparison of SP and non-SP populations in hypoxia revealed elevated levels of proteins participating in the regulation of cell cycle and DNA repair (DNA excision repair protein ERCC-6-like, charged multivesicular body protein 7, and nibrin), which may indicate higher resistance of SP cells. Conversely, results did not confirm more aggressive features of SP cells as the levels of proteins associated with the EMT process were reduced in SP compared to non-SP cells, i.e., cadherin-2 (N-cadherin, gene CDH2) [34], aurora kinase B [35], NT5E [33], forkhead box protein K1 [36], cathepsin L1 [37], PHD finger protein 14 [38], protein argonaute-2 [39], NNMT [32], transcriptional enhancer factor TEF-1 [40], polycomb complex protein BMI-1 [41], ankycorbin [42], and C-type mannose receptor 2 [43] (see Table 2).

On the basis of these findings, we employed a scratch wound assay to compare the migration ability of SP and non-SP subpopulations. As a result, we observed only nonsignificant indication of slower migration of SP cells compared to non-SP cells isolated from both normoxic and hypoxic parental populations (Appendix Fig. A5). By comparing the effect of oxygenation, it was found that neither SP (Fig. 6A) nor non-SP (Fig. 6B) migrated differently because of the preincubation with 1 % O2.

Fig. 6.

Migration of SP and non-SP cells separated from the A549 cell line. Graphs showing migration progression measured as the relative wound density (%) in SP cells (A) and non-SP cells (B) after 16 h preincubation with hypericin (1 µM) in normoxia or hypoxia followed by FACS. SP and non-SP cells were then incubated for several days to obtain 100 % confluence before the scratch. The results are expressed as the mean values ± SEM of two independent experiments. The experimental group treated with hypericin in hypoxia was compared with the other groups by t-test (*** p < 0.001).

To gain further insight into the hypoxic management of cancer cells, we analyzed proteins in hypoxic SP and non-SP versus normoxic SP and non-SP simultaneously (the full list of significantly changed proteins in hypoxia is presented in Appendix Table A4). Reactome-validated proteomic analysis (Table 3) revealed considerable differences between normoxia and hypoxia as culturing cells under hypoxic conditions significantly increased the levels of those proteins associated with signaling pathways involved in ECM organization (plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (serpin E1), lysyl oxidase homolog 2 (LOXL2), procollagen-lysine,2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 2 (PLOD2), prolyl 4-hydroxylase subunit alpha-1 and 2 (P4HA1 and P4HA2), basigin, and agrin) and collagen formation or modification (PLOD2, P4HA1, P4HA2, and LOXL2).

Table 3.

List of the Reactome pathways significantly connected to increased levels of proteins after A549 cell exposure to hypoxic conditions.

| Pathway name | Entities found | Entities total |

Entities´ pValue |

Entities´ FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular matrix organization |

6 (PLOD2, LOXL2, P4HA1, P4HA2, serpin E1, basigin) |

329 | 1.45E−4 | 8.4E−3 |

| Collagen formation | 4 (PLOD2, LOXL2, P4HA1, P4HA2) | 104 | 3.31E−5 | 5.77E−3 |

| SLC-mediated transmembrane transport | 4 (GLUT1, SLC2A3, SLC16A3, basigin) | 416 | 1.5E−2 | 1.03E−1 |

| Metabolism of carbohydrates | 4 (GLUT1, PFKL, PGK1, GBE1) | 456 | 2.14E−2 | 1.29E−1 |

| Collagen biosynthesis and modifying enzymes | 3 (PLOD2, P4HA1, P4HA2) | 76 | 2.46E−3 | 7.98E−2 |

| Pyruvate metabolism and Citric Acid cycle | 3 (SLC16A3, NNT, basigin) | 100 | 5.28E−3 | 7.98E−2 |

| Cellular hexose transport | 2 (GLUT1, SLC2A3) | 28 | 1.38E−4 | 8.4E−3 |

| Proton-coupled monocarboxylate transport | 2 (SLC16A3, basigin) | 12 | 8.43E−4 | 3.63E−2 |

| Glycolysis | 2 (PFKL, PGK1) | 110 | 6.85E−3 | 7.98E−2 |

| Basigin interactions | 2 (basigin, SLC16A3) | 26 | 3.84E−3 | 7.98E−2 |

| Vitamin C (ascorbate) metabolism | 2 (GLUT1, SLC2A3) | 26 | 3.84E−3 | 7.98E−2 |

| RAC3 GTPase cycle | 2 (TRIO, AMIGO2) | 100 | 4.82E−2 | 1.53E−1 |

A significant increase in the expression of genes coding serpin E1, LOXL2, and PLOD2 under hypoxia was confirmed by RT-qPCR on the model of the A549 cell line. In the case of HT-29 cells, we observed a significant hypoxia-induced increase in the PLOD2 expression only because the expression levels of other genes were below the detection limit (Fig. 7). It is known that the ECM stiffening that occurs in hypoxic tumors might stimulate metastatic dissemination. One of the first signs of this process on the cellular level is the EMT [reviewed in [44]]. Therefore, we employed the measurement of the mRNA levels of CDH2 (N-cadherin) and VIM (vimentin) as mesenchymal markers and CDH1 (E-cadherin) as an epithelial marker. However, we failed to prove that hypoxia forces EMT transition in A549 and HT-29 cells. Surprisingly, HT-29 cells seemed to become even more epithelial under hypoxia due to a significant increase in CDH1 expression, with undetectable expression of VIM and CDH2 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

RT-qPCR analysis of genes associated with the ECM reorganization and EMT process. The comparison of the gene expression of SERPINE1, LOXL2, PLOD2, CDH1, CDH2, and VIM under normoxia and hypoxia in A549 (A) and HT-29 (B) cells treated or untreated with hypericin. Hypericin (0.5 and 1 µM) was added to normoxic and hypoxic cells 24 h after seeding and gene expressions were analyzed 16 h after hypericin addition. PMMI was used as a reference gene, and the results are expressed in boxplots of at least two independent experiments. Hypoxic groups were compared with appropriate normoxic groups by t-test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001), and simultaneously, experimental groups treated with hypericin in normoxia or hypoxia were compared with the untreated normoxic (○) or hypoxic control group (• p < 0.05), respectively, or were compared against each other by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (** above line, p < 0.01).

3.5. Hypericin in hypoxia stimulates the PLOD2 expression and simultaneously selects a minor subpopulation of cancer cells with increased migratory abilities

Although hypoxia itself primarily did not potentiate EMT in A549 and HT-29 cells, we intended to verify the impact of hypericin in hypoxia on the change in EMT markers, since hypericin was shown to modulate EMT-related proteins under normoxia [19]. However, hypericin did not affect the expression of CDH2, VIM, or CDH1 (Fig. 7). Moreover, we did not observe a general hypericin-stimulated expression of the ECM reorganization-related genes, except for an increase in the PLOD2 expression in hypoxic A549 cells treated with 1 µM hypericin. Simultaneously, 0.5 μM hypericin slightly (t-test, p = 0.053) amplified the hypoxia-induced increase in LOXL2 level (Fig. 7). A recent study pointed out that PLOD2 enables the initiation of tumor metastasis by stimulating cell motility through the stabilization of integrin β1 [45]. Hence, we examined the changes in the motility of SP and non-SP cells separated from the A549 cell line after their incubation with hypericin (1 µM) due to the significantly stimulated PLOD2 expression in the whole A549 population via functional scratch wound assay. The preincubation of cells with hypericin stimulated the cell migration ability only in the SP subpopulation and not in non-SP cells, but this stimulus appeared to be dependent on oxygenation as the significance of this potentiation was observable particularly in hypoxia pretreated cells (Fig. 6). Hence, only the coaction of hypericin and hypoxia could positively affect the migration ability of SP cells (Fig. 6A).

As the ability of a single cell to form a cell colony is known to be a marker of normal stem cells as well as CSCs [46], we further determined the effect of hypericin on the clonogenic ability of single SP and non-SP cells under normoxia and hypoxia to gain more insight into the overall hypericin action on these subpopulations. The result of our clonogenicity assay showed that preincubation in hypoxia significantly stimulated the clonogenic capacity of both SP and non-SP cells, but this effect was reversed by hypericin in SP cells but not in non-SP cells (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Clonogenic ability of SP and non-SP cells. Hypericin (1 µM) was added to normoxic and hypoxic cells 24 h after seeding, followed by FACS 16 h after hypericin addition. Nine days later, clonogenicity of SP and non-SP cells was evaluated. Effect of hypericin on the clonogenicity of SP and non-SP cells under normoxia and hypoxia was evaluated using resazurin reduction assay. The results are expressed as the mean values ± SD of three independent experiments. SP groups were compared with the appropriate normoxic SP control group (▲ p < 0.05, ▲▲ p < 0.01, ▲▲▲ p < 0.001), and experimental non-SP groups were compared with the appropriate normoxic non-SP control group (∆ p < 0.05). Simultaneously, the experimental SP group treated with 1 µM hypericin in hypoxia was compared with the appropriate untreated SP hypoxic control group (♦♦ p < 0.01). Moreover, the comparison between SP and non-SP groups was established by t-test (statistics above the gray line).

Altogether, the SP population was significantly reduced by hypericin and hypoxia, and hypericin suppressed the hypoxia-acquired clonogenic ability of SP cells, but all this at the expense of the acquisition of a more aggressive phenotype. All of our results led to the current conclusion that hypericin itself does not have a direct effect on SP cells as our results might suggest, but rather, hypericin only selects a certain subpopulation of cancer cells with the strongest efflux abilities. In other words, because of the selection pressure on BCRP, hypericin yields a small percentage of cells that can represent bona fide SP, and only these cells may further acquire undesirable properties, such as increased migratory ability.

4. Discussion

A hypoxic microenvironment is an integral part of solid tumors and is often responsible for the failure of chemotherapy. The essential signaling pathway activated in hypoxia is the HIF-1/2α pathway, which triggers the transcription of its target genes that are necessary for cancer cells to cope with adverse conditions [reviewed in [3]]. Among the many HIF targets, the BCRP transport protein is also extensively studied. BCRP is known to be a determinant of the SP phenotype, as was also confirmed by current proteomic analysis, and a marker of CSCs because of the efflux of many clinically relevant chemotherapeutics [10], [47]. However, we found that the expression pattern of ABCG2 was opposite to that of typical hypoxia-induced genes (SLC2A1, CA9, or POU5F1) as we noticed that BCRP decreased on mRNA and protein level in all studied cell lines under conditions with 1 % O2. Interestingly, simulation of hypoxic conditions with the chemical inducer of HIF-1α, CoCl2, slightly but insignificantly increased BCRP protein level compared to 1 % O2. Several studies have discussed different molecular mechanisms initiated in cells by CoCl2 and reduced oxygen percentage [reviewed in [48]], with the latter more closely resembling the in vivo microenvironment. It was shown that despite the similarities in the hypoxic machinery in cells, such as the increase in HIF-1/2α levels, their transcriptional functions were differentially affected, and at the same time, the genes induced by these two hypoxia models did not completely overlap [49], [50]. Thus, under 1 % O2, additional transcription factors or coactivators may be involved, and differential regulation may occur. One another potential transcriptional activator of BCRP is the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor (AhR). The activation of the AhR target genes is preceded by the dimerization of AhR with the nuclear translocator ARNT (HIF-β), which is also a heterodimeric partner of HIF-1α. Thus, in hypoxia, AhR transcriptional activity may be inhibited because of competition with HIF-1α as a common binding partner, and consequently, it may lead to the decreased expression of AhR target genes [28]. This regulatory crosstalk mechanism between AhR and HIF-1α was also proposed as a cause of the observed reduction in BCRP levels in choriocarcinoma cells under 3 % O2 [51], [52]. The possible regulatory role of AhR in the hypoxia-mediated downregulation of BCRP was also suggested in our study when mRNA levels of ABCG2 and CYP1A1, suggested and validated AhR target gene, respectively, diminished in hypoxia. However, further functional experiments are needed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms and biological outcomes of the AhR–HIF-1β–HIF-1α regulatory crosstalk and BCRP transporter.

Proteomic analysis revealed a 0.44-fold hypoxia-mediated decrease in BCRP in SP fraction (p = 0.014, data not shown). This was in agreement with the overall drop in BCRP, together with the decline in the size of the SP observed in cells cultivated in the presence of 1 % O2. Interestingly, CoCl2, in contrast to hypoxia in gas chamber, enlarged the size of the SP population in cell lines A549 and A2780, excluding HT-29. In addition, the study by Mahkamova et al. identified an increase in the proportion of thyroid cancer-derived SP cells mediated by CoCl2 (100 μM) treatment after 48 h [53], which is in line with the generally expected assumption of the increasing SP size due to hypoxia [54]. Despite this, a few studies showed increased accumulation of Hoechst 33342 dye, reflecting a decrease in %SP, even after 48 h treatment with CoCl2 (200 μM) [51] or 18 and 24 h treatment with 3 % O2 [51], [52]. All of these conflicting results may be a manifestation of variations in factors affecting SP size under hypoxic exposure in vitro, such as different percentages of oxygen or concentrations of a chemical inducer, duration of hypoxic treatment, cell type, harvesting density, and serum starvation [54]. Our results may serve as further evidence that chemically induced hypoxia significantly differs from hypoxia that naturally occurs in cells and that might lead to distinct conclusions obtained by these two models.

In addition, hypoxia is known to promote resistance as well as aggressiveness of cancer cells, and simultaneously, SP cells have been found to be more resistant to chemotherapy [reviewed in [1], [55]. However, besides an elevated BCRP level or activity of SP cells, other typical traits of this subpopulation are not widely known. Steiniger et al. [56] identified high levels of thymosin beta-4, a protein known to be involved in cell motility and EMT [57], using mass spectrometry in MCF-7 SP cells and demonstrated that this protein is also implicated in drug resistance of stem cell-enriched population [56]. Similarly, in another study, a total of 12 genes significantly upregulated in the SP cells of the A549 cell line were described [58], of which only ABCG2 and NR0B1 (encoding protein DAX-1), both contributing to chemoresistance, corresponded to our results (data for DAX-1 in hypoxic SP versus non-SP are not shown because the p-value [0,041] was out of the set range). Although another study confirmed the upregulation of NR0B1 in A549 SP cells, authors also demonstrated that siRNA-mediated downregulation of NR0B1 did not affect SP percentage, suggesting that NR0B1/DAX-1 is not essential for SP maintenance [59]. This may indicate that the SP phenotype may be associated with different cell characteristics depending on the tumor type. Here, focusing mainly on the differences between SP and non-SP A549 cells, especially in hypoxia, we showed that high levels of BCRP and other proteins participating in the regulation of cell cycle and DNA repair (identified by Reactome analysis; data not shown), such as DNA excision repair protein ERCC-6-like, charged multivesicular body protein 7, and nibrin, may indicate higher resistance of hypoxic SP cells compared to hypoxic non-SP cells. Conversely, proteomic analysis revealed that several proteins significantly reduced in SP cells may be a manifestation of a weaker migration ability of SP cells compared to non-SP cells in hypoxia (proteins are listed in Section 3.4). The wound scratch healing assay supported these findings only partially, when non-SP cells represented the leading group in the wound closure under both conditions, but this discrepancy was not significant. This could be connected to the experimental hypoxia model itself as we let the cells settle and grow under normoxia for several days before scratch assay was performed, which could milden possible differences between cells. Also, non-SP can generate SP cells and vice versa when expanded in culture [60].

Current proteomic analysis also confirmed that cancer cells cope with 1 % O2 by activating the signaling pathway of ECM organization together with collagen formation and biosynthesis, and all this can promote metastasis [61], [62]. We identified an increased level and expression of several proteins associated with these pathways, above all PLOD2, serpin E1, and LOXL2. These results suggest that in the conditions of living organisms, cancer cells would respond to hypoxia by the active support of the desmoplastic stroma. In turn, stiffened and aligned collagen would facilitate the migration of cancer cells toward the vessels to reach the circulation [63]. Moreover, an increased level of PLOD2 could manifest in vitro because it was shown to bind and localize integrin β1, a critical motor molecule for invasion. Thus, PLOD2 was shown to be implicated in activation of invasion process without affecting EMT markers [45]. Similarly, in our study, there were no changes in CDH1, VIM, or CDH2 mRNA levels in A549 cells under hypoxia, yet proteomics indicated an increase in N-cadherin in hypoxic SP (not identified in normoxic SP) and non-SP cells (p = 0.001; adj. p = 0.014) compared to their normoxic counterparts. Collectively, under hypoxic conditions, cancer cells are forced to undergo certain changes that may ultimately result in a more aggressive phenotype, but this is obviously cell type-dependent. A549 cells responded to hypoxia by changing into a mesenchymal phenotype, although this change was manifested mainly at the protein level, and HT-29 cells retained an epithelial phenotype characterized by increased CDH1 expression. Moreover, these changes in the phenotype might be linked to the PLOD2, LOXL2, and SERPINE1 expression.

Traditional cancer therapies, such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy, are aimed at eradicating the rapidly dividing cells in the tumor, but in most cases, these long-term treatments for cancer patients end in relapse. After all, they are insufficient therapies in terms of affecting the CSC population. Thus, research into the effects of natural compounds with anti-CSC properties, which could serve as an adjuvant treatment to traditional therapy, came to the fore [reviewed in [64], [65]]. As the increased efflux activity of ABC transport proteins is one of the main mechanisms of CSC resistance, there is an attempt to find a compound that would attenuate this efflux. Hypericin, which is synthesized by plants of the genus Hypericum, appears to be a suitable candidate. Hypericin was found to be a substrate of the BCRP transport protein [21], and we have shown a potential role of hypericin in competitive inhibition of BCRP, when hypericin reversibly reduced the size of the SP population, presumably through the suppression of the Hoechst 33342 efflux [22]. However, hypoxic conditions may lead to different conclusions. This is thought to be the result of the degrading effect of hypericin on the key regulator of hypoxia, HIF-1α [23]. First, in our study, we have demonstrated that hypericin accumulated comparably in hypoxic as in normoxic cells despite the decline in BCRP protein, so we did not expect that hypoxia could impair its efficacy compared to normoxia. Second, we confirmed a hypericin-mediated decrease in HIF-1α and, for the first time, showed hypericin-mediated degradation of HIF-2α in hypoxia. However, when monitoring changes in HIF-1α/2α transcriptional activity via the expression of their target genes, CA9, POU5F1, and SLC2A1, we found that hypericin decreased the expression of CA9 only and solely in HT-29 cells in hypoxia. On this basis, we assume that despite the decrease in HIF-1α or HIF-2α, their levels might still be sufficient to maintain the expression of their target genes or, alternatively, it is known that some specific target genes of HIF-1α and HIF-2α are often regulated by both isoforms [reviewed in [66]] and thus can take over the other’s role if necessary. The mechanism of hypericin action on HIF-1α was previously demonstrated in the study by Barliya et al. [23]. They found that hypericin-induced HIF-1α degradation was mediated by cathepsin B, which became active because of a reduction in the intracellular pH. Under these conditions, hypericin also induced the polyubiquitination of Hsp90 and prevented the formation of the Hsp90/HIF-1α complex, thus halting the remaining HIF-1α passage into the nucleus [23]. Any discrepancy between our results and those of the study by Barliya et al. can be explained by the lower hypericin concentrations used (1 and 5 µM versus 10 and 30 µM, respectively) and longer cell cultivation in hypoxia (40 h versus 6 h, respectively). Obviously, the potency of hypericin depends on its concentration. However, we also demonstrated a hypericin-mediated increase in the POU5F1 expression under hypoxia in A549 cells, although hypericin demonstrably decreased the HIF-2α level. Whether this may immediately indicate the (in)direct regulation of the stemness marker Oct-4 by hypericin is not clear. Zhang et al. [67] demonstrated that only the co-overexpression of HIF-2α and Oct-4 had a positive effect on the survival of very small embryonic mesenchymal stem cells, and conversely, overexpression of one while silencing the other weakened this effect. Thus, further studies are needed to elucidate the involvement of hypericin in Oct-4 regulation.

Next, we demonstrated that hypericin effectively decreased the size of already diminished SP fraction caused by hypoxia in a dose-dependent manner. However, no further decrease in BCRP levels was observed because of hypericin in hypoxia. Thus, results may indicate a coaction of reducing BCRP expression by hypoxia and competitive inhibition of BCRP by hypericin, leading to marked reduction in the SP population.

Hypericin-mediated competitive inhibition of BCRP was first suggested when hypericin successfully stimulated the efficacy of MTX in BCRP-overexpressing HL-60/PLB cells [20] and then when it diminished the percentage of SP cells derived from the A549 cell line [22]. Our current study enriched these results with hypoxia. We showed that combined treatment with hypericin and MTX stimulated necrosis of the whole A549 population only in normoxic conditions at 24 h, but in hypoxia, incubation of cells with hypericin and MTX, especially at 48 h, led rather to their adaptation as there was an increase in living cells compared to treatment with MTX alone. Despite the decrease in BCRP level as well as its activity, hypoxia activates other resistance mechanisms that also do not allow increased MTX accumulation, such as tumor acidosis preventing cellular uptake of drugs or controlling the pH-dependent activity of topoisomerase type II, which is a target of MTX action [68]. Either way, it is clear that blocking BCRP by hypericin and reducing its level by potential competitive inhibition are not sufficient to potentiate the MTX effect in A549 cells, probably due to the already mentioned mechanisms.

However, considering all of these facts, even under the pressure of hypoxia and hypericin, a small population of cancer cells could preserve the SP phenotype. Thus, we assumed that only the most resilient population of cells could conquer those harsh conditions and retain at least some of the BCRP activity. Because this might be a strategy to protect an important cell fraction, we have verified if those cells might bear some other favorable features. We found that hypericin selectively stimulated the migration of SP cells, and at the same time, we noticed that hypericin mediated these properties only in hypoxic conditions. No effect was observed on non-SP cells. A possible mechanism of hypericin-stimulated cell migration in hypoxia might be coupled with increased PLOD2 expression observed in the whole A549 population. PLOD2 is considered a new prognostic factor for many cancers due to the promotion of CSC characteristics. Moreover, in PLOD2-overexpressing cells, stem cell marker Oct-4/POU5F1 was found to be upregulated [69]. Similarly, in our study, hypericin increased not only PLOD2 expression but also POU5F1 expression, mainly under hypoxic conditions. Moreover, PLOD2 ability to bind and stabilize integrin β1 [45] favors this deduction. Thus, referring to the increased migratory capacity of only the SP population after pretreatment with hypericin in hypoxia, further research is needed to explore the underlying mechanism of PLOD2 and hypericin interplay with respect to SP cell modulation.

Moreover, the assumption that hypericin affects more significantly SP cells, and not non-SP, was demonstrated by the clonogenicity assay, when hypericin reversed the clonogenic ability of SP cells, but not non-SP cells, both acquired by hypoxia. Considering all our results, SP cells contain higher levels of BCRP protein than non-SP, even in hypoxia, which is also associated with a higher level of resistance of SP cells. Consequently, the hypericin content in SP cells should be lower than that in non-SP, as was demonstrated under normoxic conditions [22]. Despite this, hypericin treatment still acts predominantly on the features of SP cells. This may indicate that in the hypoxic areas of the tumor, SP cells, due to their stem potential, become a reservoir for cells that acquire a mesenchymal phenotype [70], [71], i.e., non-SP cells. Under this situation, hypericin apparently selects the SP subpopulation with the strongest efflux and migratory abilities, but it is not clear if this is the result of solely “passive” selection of small SP fraction by hypericin by overwhelming the BCRP transport or what is the contribution of hypericin effect on stemness-related genes, such as exemplified by PLOD2 or POU5F1.

5. Conclusion

The study of hypoxic management in tumors has been proven to be justified in view of obtaining further knowledge regarding the character of cancer cells under conditions more similar to the in vivo microenvironment. Proteomic analysis revealed a strategy for the acquisition of the aggressive behavior of cancer cells due to oxygen deprivation, which is based on the stimulation of protein levels associated with the reorganization of the ECM. However, contrary to popular belief, the majority of the EMT-associated proteins were identified in non-SP cells rather than SP cells. Several studies have demonstrated that SP cells show an increased expression of mesenchymal markers, a phenotype typically associated with invasive cells, but at the same time, it has been suggested that SP cells may also serve as a reservoir for the production of cells capable of the mesenchymal process, in our case for non-SP cells. Our results showed that SP cells are more epithelial in nature, which is also indicated by a significantly reduced protein level of N-cadherin or other less typical mesenchymal markers, such as NNMT or NT5E. Moreover, under these in vivo-like conditions, we found that a single pretreatment of cells with hypericin led to a marked reduction in SP fraction, probably as the result of two different mechanisms, i.e., reduced BCRP expression by hypoxia and competitive inhibition of BCRP by hypericin. However, hypericin appears to select a minor subpopulation of cancer cells with the strongest efflux abilities and a more aggressive phenotype, and for that reason, hypericin is not suitable for adjuvant therapy as an intended BCRP competitive inhibitor, as further demonstrated by its inability to potentiate the effect of MTX. In addition, further studies are necessary to elucidate the effect of the hypericin-mediated increase in POU5F1 and PLOD2 expression on these SP cells in hypoxia.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Buľková V: Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Vargová J: Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Babinčák M: Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Jendželovský R: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Zdráhal Z: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Roudnický P: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Košuth J: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Fedoročko P: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This publication is the result of the project implementation: “Open scientific community for modern interdisciplinary research in medicine (OPENMED),” ITMS2014+: 313011V455 supported by the Operational Programme Integrated Infrastructure, funded by the ERDF; further by EPIC-XS, Project no. 823839, funded by the Horizon 2020 programme of the European Union, by CIISB infrastructure project LM2023042 funded by MEYS CR, and by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic under the Contract no. VEGA 1/0022/19 and the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the Contract no. APVV-18-0125. The authors are very grateful to Viera Balážová for the assistance with the technical procedures.

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114829.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Emami Nejad A., Najafgholian S., Rostami A., Sistani A., Shojaeifar S., Esparvarinha M., Nedaeinia R., Haghjooy Javanmard S., Taherian M., Ahmadlou M., Salehi R., Sadeghi B., Manian M. The role of hypoxia in the tumor microenvironment and development of cancer stem cell: a novel approach to developing treatment. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21 doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01719-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semenza G.L. Defining the role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer biology and therapeutics. Oncogene. 2010;29:625–634. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dengler V.L., Galbraith M.D., Espinosa J.M. Transcriptional regulation by hypoxia inducible factors. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014;49:1–15. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.838205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu C.-J., Wang L.-Y., Chodosh L.A., Keith B., Simon M.C. Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) and HIF-2α in hypoxic gene regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:9361–9374. doi: 10.1128/mcb.23.24.9361-9374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Covello K.L., Kehler J., Yu H., Gordan J.D., Arsham A.M., Hu C.J., Labosky P.A., Simon M.C., Keith B. HIF-2α regulates Oct-4: effects of hypoxia on stem cell function, embryonic development, and tumor growth. Genes Dev. 2006;20:557–570. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sowa T., Menju T., Chen-Yoshikawa T.F., Takahashi K., Nishikawa S., Nakanishi T., Shikuma K., Motoyama H., Hijiya K., Aoyama A., Sato T., Sonobe M., Harada H., Date H. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 promotes chemoresistance of lung cancer by inducing carbonic anhydrase IX expression. Cancer Med. 2017;6:288–297. doi: 10.1002/cam4.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He X., Wang J., Wei W., Shi M., Xin B., Zhang T., Shen X. Hypoxia regulates ABCG2 activity through the activivation of ERK1/2/HIF-1α and contributes to chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2016;17:188–198. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2016.1139228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He M., Wu H., Jiang Q., Liu Y., Han L., Yan Y., Wei B., Liu F., Deng X., Chen H., Zhao L., Wang M., Wu X., Yao W., Zhao H., Chen J., Wei M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2α directly promotes BCRP expression and mediates the resistance of ovarian cancer stem cells to adriamycin. Mol. Oncol. 2019;13:403–421. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das B., Tsuchida R., Malkin D., Koren G., Baruchel S., Yeger H. Hypoxia enhances tumor stemness by increasing the invasive and tumorigenic side population fraction. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1818–1830. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou S., Schuetz J.D., Bunting K.D., Colapietro A.M., Sampath J., Morris J.J., Lagutina I., Grosveld G.C., Osawa M., Nakauchi H., Sorrentino B.P. The ABC transporter Bcrp1/ABCG2 is expressed in a wide variety of stem cells and is a molecular determinant of the side-population phenotype. Nat Med. 2001;7(9):1028–1034. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adamska A., Falasca M. ATP-binding cassette transporters in progression and clinical outcome of pancreatic cancer: what is the way forward? World J. Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3222–3238. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i29.3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rook A.H., Wood G.S., Duvic M., Vonderheid E.C., Tobia A., Cabana B. A phase II placebo-controlled study of photodynamic therapy with topical hypericin and visible light irradiation in the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and psoriasis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;63:984–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritz R., Daniels R., Noell S., Feigl G.C., Schmidt V., Bornemann A., Ramina K., Mayer D., Dietz K., Strauss W.S.L., Tatagiba M. Hypericin for visualization of high grade gliomas: first clinical experience. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2012;38:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stroffekova K., Tomkova S., Huntosova V., Kozar T. Importance of Hypericin-Bcl2 interactions for biological effects at subcellular levels. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2019;28:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martínez-Poveda B., Quesada A.R., Medina M.Á. Hypericin in the dark inhibits key steps of angiogenesis in vitro. Eur. J. Pharm. 2005;516:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blank M., Mandel M., Hazan S., Keisari Y., Lavie G. Anti-cancer activities of hypericin in the dark. Photochem. Photobiol. 2001;74:120–125. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2001)0740120ACAOHI2.0.CO2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blank M., Lavie G., Mandel M., Hazan S., Urenstein A., Meruelo D., Keisari Y. Antimetastatic activity of the photodynamic agent hypericin in the dark. Int. J. Cancer. 2004;111:596–603. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Couldwell W.T., Surnock A.A., Tobia A.J., Cabana B.E., Stillerman C.B., Forsyth P.A., Appley A.J., Spence A.M., Hinton D.R., Chen T.C. A phase 1/2 study of orally administered synthetic hypericin for treatment of recurrent malignant gliomas. Cancer. 2011;117:4905–4915. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]