Abstract

Healthcare workers experience moral injury (MI), a violation of their moral code due to circumstances beyond their control. MI threatens the healthcare workforce in all settings and leads to medical errors, depression/anxiety, and personal and occupational dysfunction, significantly affecting job satisfaction and retention. This article aims to differentiate concepts and define causes surrounding MI in healthcare. A narrative literature review was performed using SCOPUS, CINAHL, and PubMed for peer-reviewed journal articles published in English between 2017 and 2023. Search terms included “moral injury” and “moral distress,” identifying 249 records. While individual risk factors predispose healthcare workers to MI, root causes stem from healthcare systems. Accumulation of moral stressors and potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs) (from administrative burden, institutional betrayal, lack of autonomy, corporatization of healthcare, and inadequate resources) result in MI. Individuals with MI develop moral resilience or residue, leading to burnout, job abandonment, and post-traumatic stress. Healthcare institutions should focus on administrative and climate interventions to prevent and address MI. Management should ensure autonomy, provide tangible support, reduce administrative burden, advocate for diversity of clinical healthcare roles in positions of interdisciplinary leadership, and communicate effectively. Strategies also exist for individuals to increase moral resilience, reducing the impact of moral stressors and PMIEs.

Keywords: moral injury, moral distress, management, COVID-19

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the exposure of healthcare workers to higher work demands with strained resources. As a result, healthcare workers experience workplace physical and psychological stressors yet are expected to maintain professionalism, empathy, and sympathy, and often neglect their care for the needs of their patients. These stressors compound the increasing complexity of healthcare, including more technology, chronically ill patients, more advanced procedures, expanding medication options, and necessary skills from healthcare workers.

The uphill climb of responsibility and expectations can precede the downward spiral of an inability to fulfill all facets of the healthcare worker’s role, creating conflict in one’s moral code. Moral injury (MI) is a concept that describes an individual experiencing a single or repetitively offensive event, often out of their control, that transgresses their moral values or beliefs.1,2 MI affects society and healthcare workers (e.g., nurses, advanced practice nurses, paramedics, physicians, physician assistants, social workers, and therapists) and increases medical errors and functional impairment. 3 Furthermore, Rushton et al. 4 found 32.4% of the 595 healthcare workers surveyed reported clinically significant MI, with nurses (38.1%) reporting the highest number of MI incidents. Mantri et al. 3 reported that even before the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately one in four clinicians experienced at least moderate impairment in family, social, or occupational functioning from MI symptoms. Despite its prevalence, the causes of MI in healthcare are still being discovered. This article defines and differentiates concepts, antecedents, and consequences surrounding MI and discusses the causes of MI in healthcare. Additionally, this article proposes a conceptual model of the continuum of MI. This model aims to provide a better understanding of the process and inter-relatedness of the concepts encompassing MI.

Methods

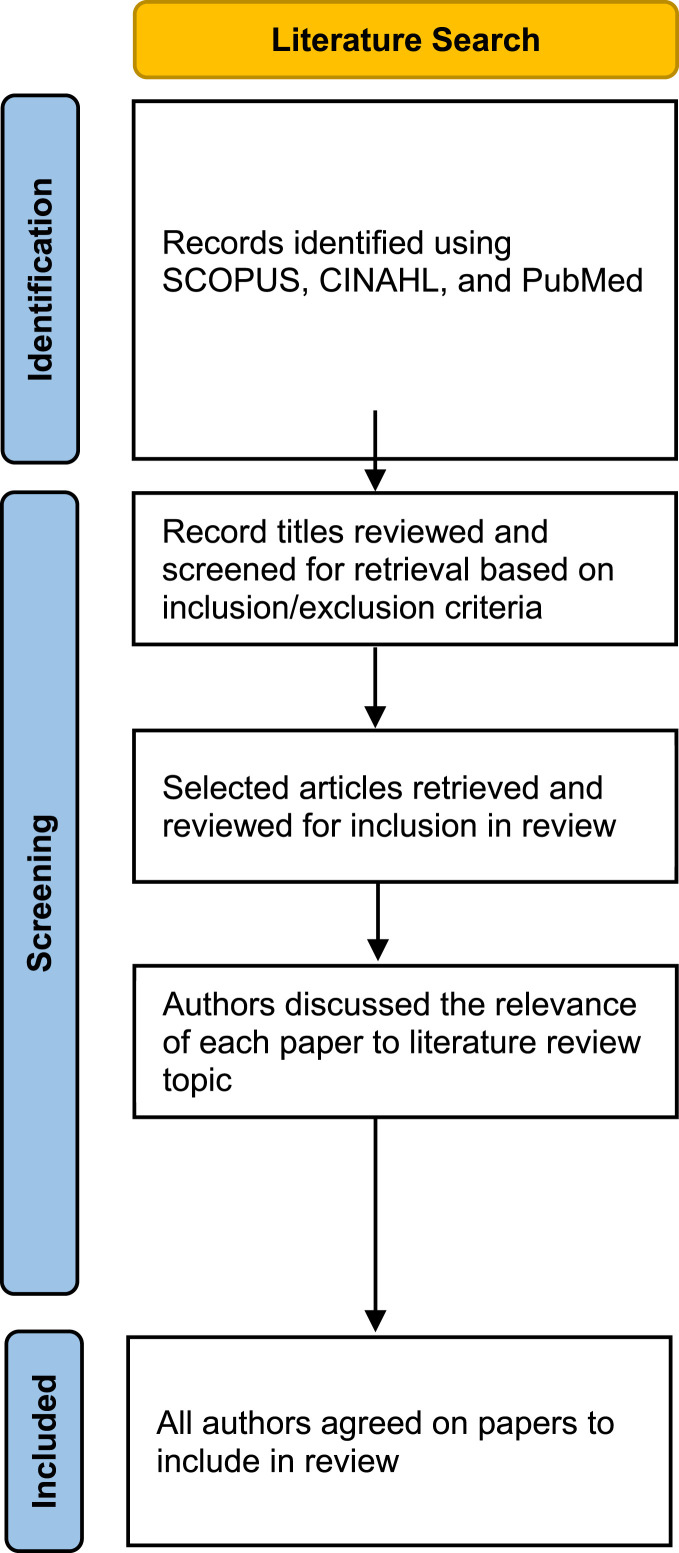

A narrative literature review was performed using SCOPUS, CINAHL, and PubMed databases for peer-reviewed journal articles published in English between 2017 and 2023, the years when MI became recognized in healthcare literature (see Figure 1). Search terms and phrases included “moral injury” and “moral distress.” Exclusion criteria included books, newspapers, non-peer-reviewed articles, and articles that did not focus on MI or moral distress within healthcare settings. The search identified 249 unique records in SCOPUS (n = 193), CINAHL Plus (n = 22), and PubMed (n = 34). The authors reviewed titles of peer-reviewed journals for retrieval and further investigation. The authors then narrowed the review topic and papers included in the review to focus on factors influencing moral injury and moral distress within a clinical healthcare context.

Figure 1.

Narrative literature review flow diagram.

The continuum of moral injury

Antecedents of moral injury: moral stressors and potentially morally injurious events

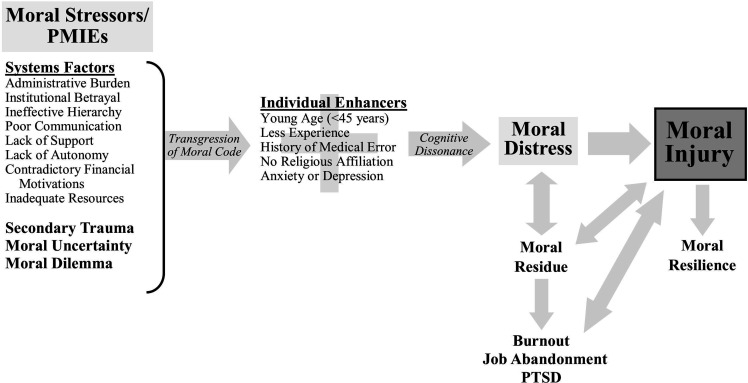

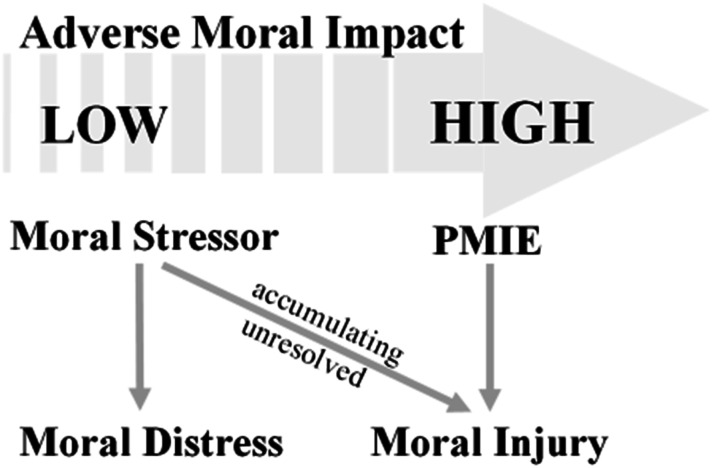

The development of MI and resulting consequences can be conceptualized on a continuum (see Figure 2). Healthcare workers are exposed to situations daily that may conflict with their values, moral code, or conscience. Moral stressors or potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs) are concepts that describe these situations. The first step in the continuum is an individual experiencing a moral stressor or PMIE. Moral stressors occur when an event takes place against what an individual considers ethically correct. 5 PMIEs describe acts of commission (which may be intentional or unintentional) or omission (witnessing and being unable to prevent an event) in high-stakes environments that cause moral transgressions with more significant consequences.6,7 For example, a medication error could cause no apparent harm to a patient (moral stressor) or cause the larger consequence of a patient dying (PMIE). Both moral stressors and PMIEs transgress an individual’s moral code and lead to cognitive dissonance (see Figure 2). Cognitive dissonance is an awareness and mental discomfort when beliefs and actions are inconsistent. 8 However, PMIEs are more significant events with greater potential to lead to MI.6,7 Moral stressors are considered lower-impact events that cause moral distress (described below) and may accumulate over time if unresolved and lead to MI (Figure 3).6,7 However, overlap exists in what types of events classify as moral stressors and PMIEs. Individuals may vary on their subjective perception of the impact of events and whether it constitutes a moral stressor or PMIE. This article discusses specific moral stressors and PMIEs in healthcare in detail later.

Figure 2.

Continuum of moral injury conceptual model.

Figure 3.

Relationship and impact of moral stressors, PMIEs, moral distress, and moral injury.

Antecedents of moral injury: secondary traumatic stress, moral uncertainty, and moral dilemmas

Apart from specific healthcare system moral stressors and PMIEs, secondary trauma, moral uncertainty, and moral dilemmas are categories of potential moral stressors and PMIEs (see Figure 2). Secondary trauma develops in healthcare workers from empathetic engagement with others who are suffering or traumatized. 9 Additionally, personal factors, such as a history of emotional trauma, how one interprets a patient’s traumatic experience, and unrealistic expectations of self, can also contribute to developing secondary trauma. 9 The moral stressor in secondary trauma is the exposure to another person’s trauma, often repetitively. 10 Nurses, counselors, and paramedics are examples of healthcare workers that frequently experience secondary trauma.

Ethical concerns contribute to secondary trauma, moral distress, and moral injury. 11 Ethical concerns may result from moral uncertainty or moral dilemmas. Moral uncertainty occurs when someone is unsure of the moral problem, principles, or values that apply to a particular situation. 12 Essentially, uncertainty exists if an ethical dilemma is present. Healthcare workers may experience a “hunch,” or “gut feeling” in which a situation is just not right. 13 This internal conflict acts as a moral stressor. Additionally, moral uncertainty can act as a moral stressor when an individual is uncertain of what action to take or how to respond in an ethical situation. 14 A moral dilemma occurs when one or more conflicting courses of action exist in an ethical situation.12,15 However, each option may have morally right and wrong aspects with no apparent reason to pursue one action over the other. 15 A moral dilemma may be perceived as a “lose-lose” situation and be a moral stressor.

Individual enhancers of moral injury

Specific personal risk factors influence the negative impact of moral stressors and PMIEs and increase the risk of developing MI. The main individual risk factors include young age (less than 45 years old), fewer years in the healthcare profession, lack of religious affiliation, history of anxiety or depression, job dissatisfaction, and existing symptoms of burnout.3,16 These risk factors can be viewed as accelerants or enhancers in the process of developing MI from moral stressors and PMIEs (Figure 2).

Moral distress and moral injury

After an individual experiences moral stressors or PMIEs, moral distress or MI can develop. Moral distress occurs from individuals experiencing cognitive dissonance, an inconsistency between a person’s beliefs and actions, after being unable to do what they consider is ethically correct due to internal or external constraints.5,12,13,15 A form of moral suffering, moral distress is a response to moral harms, wrongs, or failures, with personal feelings of compromised integrity.17,18 A hallmark of moral distress is the presence of personal or institutional constraints. 14 Essentially, moral responsibility is present, but the individual is powerless to affect the outcome. 19 However, moral distress’s psychological and functional consequences are typically temporary and moderate. 6

Moral injury emerged as a concept in response to Vietnam War veterans presenting with similar but not entirely consistent symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). 20 Shay 20 first defined MI as a betrayal of moral conscience in a high-stakes environment by either an authority figure or oneself. Dean et al. 1 reconceptualized MI to healthcare workers emphasizing, “Moral injury occurs when we perpetrate, bear witness to, or fail to prevent an act that transgresses our deeply held moral beliefs.”1(p400) Healthcare can be viewed as one large “high-stakes environment” with human lives hanging in the balance. Healthcare workers experience a constant pull of ethical responsibilities (moral stressors and PMIEs) involving the patient, their institutions, insurance companies, and themselves. 1 MI develops from introspective feelings of shame, guilt, immorality, fear, self-depreciation, and inability to forgive oneself after facing moral stressors or PMIEs. 7 Griffin et al. added MI affects an individual’s social, religious/spiritual, and biological domains. 21 MI involves a more profound emotional wound to those who witness intense human suffering and cruelty than moral distress; however, moral distress and moral residue over time can lead to MI. 14

Accumulating, unresolved moral stressors or PMIEs develop into MI through a process called the “crescendo effect” (see Figure 3).7,22 MI arises from repeated moral stressors and PMIEs, ultimately from healthcare workers’ inability to provide the healing or quality care they are morally convicted of delivering. 23 Dean et al. 1 state, “Every time we are forced to make a decision that contravenes our patients’ best interests, we feel a sting of moral injustice. Over time, these repetitive insults amass into moral injury.”(p400) Čartolovni et al. warn, “Moral injury results in long-term emotional scarring or damage contributing to permanent numbness, malfunctioning, and social isolation, which may, on the other hand, if treated in time, in a post-traumatic growth.”14(p587) The term injury provides a visualization of the emotional, psychological, spiritual, or behavioral damage and betrayal that results from MI compared to moral distress.7,24

Consequences of moral injury

The oath healthcare workers take to put the needs of their patients first is a deeply held moral belief. Every time a healthcare worker feels forced to make a decision that prioritizes the healthcare stakeholders over the patient’s best interest, a sense of moral injustice occurs. However, the individual may not return to their moral baseline but instead be left with moral residue (see Figure 2). 25 As the word “residue” implies, moral residue describes the leftover feelings after moral distress or MI. 18 Furthermore, reciprocal relationships between MI and moral distress to moral residue exist due to the iterative nature of individuals processing moral stressors and PMIEs. Moral residue is deeply painful and lasting because a person compromises their integrity. 15 Moral residue has been associated with moral numbness to ethically challenging situations, nurse burnout, and nurses leaving the profession. 25

The concept of burnout is frequently mistaken for MI. 1 However, within the continuum of MI, burnout is a consequence of MI (see Figure 2). 1 Burnout, a psychological syndrome, has three key attributes: overwhelming emotional exhaustion, cynicism and detachment from the job, and ineffectiveness, hopelessness, or lack of accomplishment.26,27 Burnout implies an individual’s inability to cope or lack of resilience within a work environment. 1 The solutions to burnout primarily focus on the individual: increasing personal resilience, social support, wellness, and decreasing stress and workload. 27 Therefore, this article supports the perspective that burnout is an individual syndrome caused by the systemic factors of moral distress and MI.

Another consequence of unresolved MI is PTSD. 20 PTSD is a psychological disorder that develops after experiencing a traumatic event or events and has four key symptoms. 28 The key symptoms include re-experiencing the trauma, avoiding any connection to the trauma, negative cognition or mood, and hyperarousal. 28 MI differs from PTSD mainly because 1. The moral stressor or PMIE in MI does not threaten mortality (as in PTSD) but instead injures one’s morality. 2. Guilt, shame, and anger are the predominant emotions in MI versus fear and horror in PTSD. 3. Physiological arousal occurs only with PTSD. 4. Loss of trust occurs in MI versus safety in PTSD. 29 Although the terms differ, healthcare workers should be aware of the potential for an individual with MI to develop PTSD.

In contrast, one possible positive consequence of MI cultivated over time exists: moral resilience. Moral resilience occurs when an individual maintains or restores their integrity through trusting their personal values or beliefs during ethical situations.30,31 The evidence of moral resilience is courage, confidence, and adaptability when addressing these situations without guilt, shame, or despair. 30 Individuals exhibiting moral resilience realize and process the complexities and intricacies of ethical situations and develop emotional flexibility. 30 Rushton 18 clarifies individuals developing moral resilience do not ignore or suppress the impact of the moral stressors but instead deepen their ability to navigate these situations.

Repeated moral stressors and potentially morally injurious events in healthcare

After discussing the continuum of moral injury, the emphasis can shift to understanding the specific antecedents (moral stressors and PMIEs) in healthcare (see Table 1). Healthcare workers regularly experience moral stressors and PMIEs when caring for patients. The literature review identified three major themes of MI in healthcare: task-oriented versus patient-oriented care, institutional barriers and betrayal, and COVID-19 exacerbation of PMIEs. Institutional barriers and betrayal further incorporate a lack of autonomy, financial motivations contradicting calling, and exacerbation of inadequate resources. While MI is a personal experience, these categories reveal responsibility from an external systems perspective of healthcare delivery, organizations, administration, and workload.

Table 1.

Examples of moral stressors or potentially morally injurious events in healthcare.

| Task-oriented care | Institutional administrative betrayal |

|---|---|

| Unable to practice how morally convicted | Hierarchical structure |

| Unable to advocate for patients | Lack of support and action |

| Understaffing/inexperienced staffing | Lack of visibility from administrators |

| Staff turnover | Criticism |

| Algorithmic care | Micro-aggressions |

| Indiscriminate and aggressive treatments | Corporatization of healthcare |

| Lack of control/autonomy over policies | Focus on revenue |

| Clerical administrative burden | Productivity metrics and bonuses |

| EHR time and documentation | Incentivizing quantity over quality |

| Paperwork | COVID-19 exacerbations |

| Redundant tasks | Emotional exhaustion |

| Inappropriate delegation of duties | Inadequate and rationing of PPE and equipment |

| Unrealistic workload and timeframes | Further strain on staffing |

| Choosing between work and personal time | Obligatory isolation of patients |

| Mandatory overtime | Inability to provide standard care |

| Patients dying in solitude | |

| Futile treatments | |

| Nurses as adversaries to patients and families |

Abbreviations: EHR: electronic health record.

Task-oriented versus patient-oriented care

The unique metaparadigm of person, environment, health, and nursing embraces a caring, holistic perspective of healthcare delivery and patient care. Performing comprehensive assessments, thinking critically, providing culturally appropriate patient education, and employing nursing interventions are all necessary yet idealistic goals of nurses in today’s healthcare. It is deemed an unrealistic expectation to practice the nursing model as taught and idealized in school due to the current reality of task-oriented over patient-oriented care. This paradigm shift creates MI. Although one may choose the healthcare profession to help and care for others, MI occurs from being unable to help, limits in training, and perceptions of impossible expectations from their organizations and communities. 32 Task-filled days limit the ability to employ theory or interventions. However, using theory in practice improves health outcomes and quality of care. 33 Task-oriented care delivery is also associated with lower job satisfaction. 34 Therefore, a nurse’s moral code is conflicted when their ability to practice on the nursing model is limited in real-world practice.

Furthermore, the reality of the ever-increasing administrative burden of using electronic health records (EHRs) contributes to significant time focused away from direct patient care. Approximately three-fourths of nurses spend at least 50% of their shift documenting in the EHR. 35 Fulfilling EHR workflows, tasks, alerts, and insurance and system-requested metrics are clerical tasks often assigned to nurses yet are rarely evaluated for appropriateness and change of workflow to increase efficiency and reduce administrative burden. 36 This unnecessary administrative burden contributes to healthcare worker frustration, perception of poorer quality care, unreasonable workload, and moral distress and MI.24,35,37 Internal conflict exists between the quality and type of care healthcare workers want to deliver and the burden of following orders and documenting. Čartolovni et al. 14 reiterate that blunted ethical sensitivity and ambivalence of healthcare workers develop when system factors deem tasks more important than human dignity. Task-oriented care becomes a daily moral stressor or even PMIE, impeding the healthcare worker’s ability to deliver the type or quality of care the patient needs. 3 MI results from the accumulation of PMIEs from the task-oriented paradigm.

In the outpatient clinical setting, similar problems exist. Administrative tasks add to the required documentation for patient encounters. For example, insurance-required prior authorizations; checklists of insurance and EHR metrics; paperwork for disability; electronic and phone messages from pharmacies, patients, durable medical equipment companies, and home health companies; and addressing patient results occur outside the direct patient encounter. While these are related to patient care, these tasks are often redundant, superfluous, burdensome, and take time away from direct patient care. Agarwal et al. 38 found that the quantity of work (being excessive and inefficient) and content of work (being clerical and incongruous with education) contributed to low professional fulfillment and burnout. Beck et al. 39 reinforced that the collection of endless metrics and burdensome use of EHRs contributed to MI and distress. In addition, clinicians experience moral distress from the administrative burden of the EHR, resulting from less time spent with patients and the complexity of each encounter. 37 As a result, clinicians must choose to sacrifice their time with their patients or their life outside of work, which leads to moral distress and, ultimately, MI. 3

Institutional barriers and betrayal

Organizational structure, hierarchy, communication, and decision-makers influence the ability of healthcare workers to advocate for themselves and their patients. In addition, institutional culture contributes to MI. Repeated micro-aggressions within a healthcare organization or workplace create a toxic culture. MI in this environment occurs from the traditional hierarchical structure, criticism, poor communication, and lack of empathy, support, and presence from institutional leadership and added work when already overburdened. 40 Employers often view employees “as machines to do a job, rather than human beings.”32(p8) Institutional betrayal also connects to the task-oriented care often prescribed by healthcare organizations.

As nursing continues to be the most trusted profession, 41 nurses have an ethical obligation to advocate for their patients at the bedside, with the healthcare team, and with the administration. While healthcare workers may strive for justice and beneficence, organizational betrayal can obstruct a culture that facilitates such advocacy.42,43 Organizational culture influences moral distress and MI, especially when administrations are not conducive to concerns or input from staff.42,44 Yalçın et al. 45 found nurses remain silent under various circumstances, including fear of retaliation, job loss, or being labeled as a troublemaker or novice. In addition, an adverse work environment and lack of support and action from the administration in response to speaking up prevent nurses from voicing their opinions. The strict hierarchy of a healthcare organization reduces approachability, creating barriers to healthcare workers communicating with the administration on behalf of patients or the healthcare team.39,45 Therefore, when MI is reinforced, healthcare workers face repeated PMIEs yet cannot speak up and be effective change agents or reconcile the moral conflict.

Lack of trust and visibility in institutional leadership increases distrust, moral distress, and MI. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated tension, disconnect, and betrayal between institutional leadership and nurses. Nelson et al. 40 found that healthcare workers, the majority of whom were nurses, experienced MI due to poorly streamlined communication of new information regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the pandemic worsened healthcare workers’ perception of support and trust in leaders, including not acknowledging or addressing concerns. 40

Lack of autonomy and decision-making

Institutional communication and reporting issues, lack of control over policies, procedures, workplace issues, and care delivery contribute to MI and burnout among healthcare workers. 37 Riedel et al. 7 agreed that a common cause of MI in healthcare workers is a lack of control, empowerment, or autonomy in influencing decisions for patient care. Within the healthcare system, hierarchical structure inherently exists, often with administrators without direct patient care experience deciding the policies and procedures on which healthcare workers practice. This disconnect between workflow and clinical priorities increases moral distress. 39 Beck et al. describe clinicians struggling with autonomy when management dictates decision-making hierarchy and which actions are valued instead of those caring for patients. 39 Beck et al. also found that decisions made without clinician influence siphoned necessary resources away from patient care. 39

Whether at the bedside or in outpatient settings, algorithmic care is often devoid of critical thinking and individualizing decisions for patient care. Algorithmic care can contribute to MI by indiscriminately and aggressively providing treatment. Healthcare workers in the United States can suffer moral distress when the healthcare system’s medical norm is to do as much as possible to and for a patient when inaction might be more appropriate. 39 These moral stressors and PMIEs include when further testing does not change medical management, inaction is the patient’s preference, or action will cause more harm than good.

Financial motivations contradicting conviction

Beck et al. 39 describe the corporatization of the United States healthcare system as a leading contributor to moral distress and MI for healthcare providers. The focus on revenue, measurement of productivity, and bonuses based on the volume of patient care, morally conflicts with clinicians’ moral imperatives of nonmaleficence, beneficence, justice, and autonomy. Clinicians feel the chasm widening between clinical practice and decision-making. Adding insult to injury, the added emphasis on and incentivization of productivity further dehumanizes healthcare. Pay structures for providers, typically for advanced practice providers and physicians, can center around relative value units (RVUs), incentivizing quantity over quality. Focusing on productivity incentivizes potentially wasteful, inappropriate, or even harmful testing and procedures on patients. 39 The pressure to do what is financially advantageous for the provider or institution over what is best for the patient transgresses a provider’s ethical code. 24 Unnecessary care also increases the patients’ financial burden, creating moral distress for providers. 39

Many healthcare workers struggle to provide care according to their moral convictions when healthcare environments focus on business rather than the patient. As the paradigm of healthcare shifts from patient care to a business model, focusing on production and documentation, MI increases. 38 Beck et al. 39 iterate that performance metrics lead to feelings of being micromanaged and demoralized. As a result, clinicians cannot do what is best for the patient, spend desired time with patients, and practice healthcare the way they feel is best, accumulating moral stressors and PMIEs, and leading to MI. Dean et al. 1 highlight the broken healthcare system that forces healthcare workers to focus on profit over healing transgresses healthcare workers’ moral code.

COVID-19 exacerbation of PMIEs

Healthcare worker shortages, high nurse-patient ratios, and understaffing in the hospital and clinic setting plagued healthcare long before COVID-19; however, the pandemic exacerbated the strained healthcare workforce and increased MI. Inadequate or inexperienced staffing, high turnover, increased working hours, and physical and emotional exhaustion contributes to burnout, attrition, and compassion fatigue.7,34,46 Compassion fatigue results from the repeated expenditure of empathy towards patients, reducing a healthcare worker’s ability or interest in providing empathy. 10 Changing routines to wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) for entire shifts and rarely taking breaks for eating, drinking, or using the bathroom contributed to exhaustion. 46 Emotional exhaustion and moral conflict resulted from the constant worry of transmissibility and possible harm to other patients and families from being a vector of COVID-19.47,48 Further insult to MI occurs from the unrealistic expectations of productivity and quality care from society and healthcare organizations as the workload increases despite inadequate staffing and abrupt change in the nursing care environment.

Furthermore, the perceived betrayal of the healthcare administration to provide adequate resources for the safe delivery of care heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic. 43 Limited resources, including PPE and ventilators, lead to rationing and triaging resources which transgress nurses’ moral code.17,40,47,49 Moral stressors and PMIEs also occurred when healthcare workers viewed COVID-19 treatment as dehumanizing, experiencing “the conflict between obligatory isolation of patients and patients’ freedom.”7(p12)

PMIEs also result from nurses’ inability to provide patients with ordinary and appropriate nursing care.7,31 Hines et al. 47 highlight delays in care, testing, treatment for other diseases, and surgeries contributed to MI because patients could not receive the usual healthcare services they needed, often resulting in adverse health outcomes. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic repeatedly exposed nurses to ineffective care and a high volume of patient mortality and morbidity, 47 creating feelings of futility. Patterson et al. 48 highlight the pervasive uncertainty surrounding patient care decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic caused moral distress. Clinical practice abruptly changed with the pandemic. Fears of transmission changed protocols for isolation, limiting contact with family and nursing care, and resuscitation and nebulized medications. Abrupt changes in institutional policies for family visitation caused healthcare workers to become adversaries to patients and families due to policies they could not control, conflicting with the their moral code. These typical, evidence-based practice changes clashed with the known standard of care, which acts as repeated moral stressors and PMIEs.

Furthermore, nurses in many specialties routinely conduct end-of-life care, a common PMIE. 7 When treatment options were limited at the pandemic’s beginning, watching patients repeatedly die with uncertain interventions increased MI. 49 Patients experiencing death in solitude without family or spiritual support also increased MI among healthcare workers. 17 Horsch et al. 50 describe that in extreme situations, healthcare workers may even feel they are personally contributing to the inhumane treatment of patients due to workplace policies and protocols.

Discussion

Preventing moral injury

Interventions to prevent MI should focus on the continuum’s previous steps (see Figure 2). MI prevention includes relieving the healthcare system moral stressors and PMIEs; therefore, avoiding cognitive dissonance, moral distress, and MI. Removing the internal and external constraints paramount to moral distress, 14 represents a critical step in preventing MI. Ultimately and simply, “failures in leadership lead to [the] catastrophic, long-lasting outcomes [of moral injury] in which trust in others is destroyed and encoded in the body.”20(p.190) Individuals and healthcare administration should recognize the continuum of MI and work to understand this concept to change the culture that leads to it. Addressing the root causes and creating solutions addressing each area will decrease the incidence of MI.

Strategies for the prevention of MI differ from those for burnout. Burnout may be the psychological syndrome that develops as the outcome of MI in an individual. However, although individuals experience MI, it is grounded in the larger, systemic problems in healthcare. Appropriately recognizing MI allows accurate allocation of the source of distress to a broken healthcare system, not broken individuals. 1 Because burnout is an individual collection of previously described symptoms, its interventions focus on the individual. Taking a work sabbatical, psychotherapy, mindfulness, yoga, and exercise are all examples of specific interventions for individuals to improve their burnout symptoms.1,51,52 However, none of these interventions address the underlying systemic moral stressors or PMIEs that cause moral distress or MI, predecessors of burnout. For example, exercise does not prevent understaffing or the corporatization of healthcare. Though these interventions may help individuals cope with burnout, they are short-sighted solutions and often unsuitably appropriated as solutions for MI. Essentially, they fail to address the root causes of MI and inappropriately place blame on healthcare workers experiencing MI. Instead, the administrative and systems issues must be corrected. Consequently, addressing the larger root problem of MI can prevent burnout.

Reforming institutional priorities

Because a primary moral stressor in healthcare is the corporatization and business model of patient care, realigning the administrative focus with healthcare worker priorities is key. For example, healthcare workers believe that high-quality care is essential, but this often conflicts with what might be financially advantageous. The directive to administration should be to support patient care, not dictate it. To appropriately realign institutions, workplace missions, policies, and financial goals, multi-disciplinary teams, including a variety of healthcare workers, need to be involved. Healthcare systems often focus on economic endpoints rather than staff integrity and patient outcomes. The recent push towards value-based, instead of financially driven RVUs returns the focus to patient-centered care with the additional benefit of improved outcomes. 53 Sheikhbahaei et al. 24 propose exposing administrators to the daily clinical experience of healthcare workers is essential to eliminate unnecessary, inappropriate, or excessive clerical tasks burdening healthcare workers.

Addressing the work environment

The moral stressors and PMIEs in healthcare (see Table 1) are often rooted in the work environment or culture. Therefore, adopting healthy work environments in all facets of healthcare is paramount to preventing MI. The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) developed six essential standards for a healthy work environment. These critical workplace elements include skilled communication, collaboration, effective decision-making, appropriate staffing, meaningful recognition, and authentic leadership. 54 These aims are the antithesis of the moral stressors and PMIEs that cause MI.

The AACN advocates that nurses should be present partners with healthcare institutional leadership, actively directing, evaluating, and leading operations and creating policies. 54 Emphasizing healthcare organization strategies to prevent MI, institutions that employ care models that allow nurses to have responsibility and authority for their patients are more satisfied and have higher nurse retention. 54 Rainer and Schneider 42 implore nurses to have moral courage and speak up about patient care needs to prevent poor patient outcomes, moral distress, and burnout. Nurses' involvement in clinical decision-making and questioning appropriateness instead of blindly following orders is essential to a healthy work environment and preventing MI. 54 Healthcare institutions must acknowledge the value of healthcare workers, empower them, and increase their autonomy. Lucas et al. 55 suggested nursing managers develop interventions to reduce psychological demand and increase the recognition of individual accomplishments and social support among colleagues. Strategies to prevent bullying in the workplace and increase healthy lifestyle choices were paramount to the prevention of moral stressors and PMIEs. 55

Effective broader strategies healthcare management should employ include the representation of front-line healthcare workers in leadership roles to address the practice climate. Engaging those most intimately involved with care provides insight into how organizational culture influences the development of MI. Exploring workflows and delegating duties to the most appropriate team member promotes organizational changes that foster increased communication and collaboration between healthcare providers and reduce moral distress. 56 Additionally, healthcare administration must advocate for advanced practice nurses to practice to the full scope of their licensure and education. 57 Empowering nurses of all levels to make decisions related to individual patient care and system-wide changes increase autonomy, decreases errors, and promotes a morally healthy environment. 19 Management interventions directed at changing organizational culture to one that promotes engagement will influence the incidence of MI.

Addressing individual enhancers and increasing moral resilience

Although MI stems from healthcare system moral stressors and PMIEs, individual enhancers increase the likelihood of MI in an individual (see Figure 2). Therefore, increasing personal moral resilience may decrease the possibility of developing MI because the moral stressors and PMIEs do not affect the individual as profoundly. Addressing modifiable individual enhancers may include treating underlying anxiety or depression and increasing spirituality.

Moral resilience develops over time and is essential for positive emotional and psychological growth through encountering unpreventable moral stressors and PMIEs in healthcare. To promote moral resilience, Rushton 18 recommends fostering self-awareness and self-regulation, developing ethical competence, voicing concerns, finding meaning during moral stress, cultivating connections with others (i.e., professional, social, family, or friends), learning from moral stressors and PMIEs, and contributing to a culture of ethical practice. Similarly, setting a “moral compass” helps develop moral resilience when facing moral stressors and PMIEs. 48 Patterson 48 describes this process of developing a moral compass. Individuals should expect and face moral stressors head-on, clarify and understand one’s personal values and commitments, create a supportive community with shared values and commitments, align choices with these values, and take assertive action with support from mentors. 48 These steps of addressing individual enhancers and increasing moral resilience can be viewed as primordial prevention for MI. While all healthcare workers would benefit from these interventions, these strategies for prevention can equip students and new healthcare workers with the knowledge and skills to prevent MI and its consequences.

Limitations

MI is still emerging in healthcare as a distinct concept; therefore, limited studies and significant overlap in the literature exist on moral distress, moral injury, and burnout. Additionally, the concept of MI may span across cultures and languages. However, because this narrative literature review only included articles written in English, moral stressors and PMIEs experienced by other cultures may not be included. More research is needed for tangible, evidence-based interventions to reduce moral stressors and PMIEs in healthcare to prevent MI.

Conclusion

This article proposes that MI, a result of repeated insults of experiences against one’s moral code or conscience when delivering patient care, is a distinct concept. Healthcare systems create and perpetuate MI through the daily exposure of moral stressors and PMIEs in healthcare workers. Consequently, MI can lead to burnout, job abandonment, or PTSD if not adequately addressed. Healthcare systems must look at the long-term strategies for preventing MI. Prevention of MI is a marathon, not a sprint, which requires a paradigm shift in how healthcare systems approach the health and value of healthcare workers. The moral stressors and PMIEs mentioned in this article leave a healthcare workforce less productive and empathetic, with more burnout, errors, and patient harm. Administrators must differentiate between burnout and MI and address each concept appropriately. Every member of the healthcare system can work to change the workplace culture on the local, regional, and national levels to prevent MI from plaguing the healthcare workforce.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Emily K Mewborn https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7830-8756

References

- 1.Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract 2019; 36(9): 400–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koenig HG, Al Zaben F. Moral injury: an increasingly recognized and widespread syndrome. J Relig Health 2021; 60(5): 2989–3011. DOI: 10.1007/s10943-021-01328-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantri S, Lawson JM, Wang Z, et al. Prevalence and predictors of moral injury symptoms in health care professionals. J Nerv Ment Dis 2021; 209(3): 174–180. DOI: 10.1097/nmd.0000000000001277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rushton CH, Thomas TA, Antonsdottir IM, et al. Moral injury and moral resilience in health care workers during COVID-19 pandemic. J Palliat Med 2022; 25(5): 712–719. DOI: 10.1089/jpm.2021.0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramos AM, Barlem ELD, Barlem JGT, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the moral distress scale-revised for nurses. Rev Bras Enferm 2017; 70(5): 1011–1017. DOI: 10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Litz BT, Kerig PK. Introduction to the special issue on moral injury: conceptual challenges, methodological issues, and clinical applications. J Trauma Stress 2019; 32(3): 341–349. DOI: 10.1002/jts.22405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riedel PL, Kreh A, Kulcar V, et al. A scoping review of moral stressors, moral distress and moral injury in healthcare workers during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19(3): 1666–1686. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph19031666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLeod S. Cognitive dissonance, https://www.simplypsychology.org/cognitive-dissonance.html (2008, accessed 23 January 2023).

- 9.Arnold T. An evolutionary concept analysis of secondary traumatic stress in nurses. Nurs Forum 2020; 55(2): 149–156. DOI: 10.1111/nuf.12409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elwood LS, Mott J, Lohr JM, et al. Secondary trauma symptoms in clinicians: a critical review of the construct, specificity, and implications for trauma-focused treatment. Clin Psychol Rev 2011; 31(1): 25–36. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly L.Burnout, compassion fatigue, and secondary trauma in nurses: recognizing the occupational phenomenon and personal consequences of caregiving. Crit Care Nurs Q 2020; 43(1): 73–80. DOI: 10.1097/cnq.0000000000000293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jameton A. Nursing practice: the ethical issues. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kälvemark S, Höglund AT, Hansson MG, et al. Living with conflicts-ethical dilemmas and moral distress in the health care system. Soc Sci Med 2004; 58(6): 1075–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Čartolovni A, Stolt M, Scott PA. Moral injury in healthcare professionals: a scoping review and discussion. Nurs Ethics 2021; 28(5): 590–602. DOI: 10.1177/0969733020966776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardingham LB. Integrity and moral residue: nurses as participants in a moral community. Nurs Philos 2004; 5(2): 127–134. DOI: 10.1111/j.1466-769x.2004.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiler CA, Hickman RL, Reimer AP, et al. Predictors of moral distress in a US sample of critical care nurses. Am J Crit Care Nurses 2018; 27(1): 59–66. DOI: 10.4037/ajcc2018968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lake ET, Narva AM, Holland S, et al. Hospital nurses’ moral distress and mental health during COVID-19. J Adv Nurs 2022; 78(3): 799–809. DOI: 10.1111/jan.15013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rushton CH. Cultivating moral resilience. Am J Nurs. 2017; 117(2 Suppl 1): S11–S15. DOI: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000512205.93596.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jameton A. Dilemmas or moral distress: moral responsibility and nursing practice. AWHONNS Clin Issues Perinat Womens Health Nurs 1993; 4(4): 542–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanal Psychol 2014; 31(2): 182–191. DOI: 10.1037/a0036090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffin BJ, Purcell N, Burkman K, et al. Moral injury: an integrative review. J Trauma Stress 2019; 32(3): 350–362. DOI: 10.1002/jts.22362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epstein EG, Hamric AB. Moral distress, moral residue, and the crescendo effect. J Clin Ethics 2009; 20(4): 330–342. DOI: 10.1086/jce200920406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dean W, Talbot S. Physicians aren’t “burning out.” They’re suffering from moral injury. STAT, https://www.statnews.com/2018/07/26/physicians-not-burning-out-they-are-suffering-moral-injury/ (2018, accessed 30 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheikhbahaei S, Garg T, Georgiades C. Physician burnout versus moral injury and the importance of distinguishing them. RadioGraphics 2023; 43(2): e220182. DOI: 10.1148/rg.220182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savel RH, Munro CL. Moral distress, moral courage. Am J Crit Care 2015; 24(4): 276–278. DOI: 10.4037/ajcc2015738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henson JS. Burnout or compassion fatigue: a comparison of concepts. MedSurg Nurs 2020; 29(2): 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016; 15(2): 103–111. DOI: 10.1002/wps.20311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirkpatrick HA, Heller GM. Post-traumatic stress disorder: theory and treatment update. Int J Psychiatry Med 2014; 47(4): 337–346. DOI: 10.2190/pm.47.4.h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev 2009; 29(8): 695–706. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rushton CH. Moral resilience: a capacity for navigating moral distress in critical care. AACN Adv Crit Care 2016; 27(1): 111–119. DOI: 10.4037/aacnacc2016275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hossain F, Clatty A. Self-care strategies in response to nurses’ moral injury during COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Ethics 2021; 28(1): 23–32. DOI: 10.1177/0969733020961825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith-MacDonald L, Lentz L, Malloy D, et al. Meat in a seat: a grounded theory study exploring moral injury in Canadian public safety communicators, firefighters, and paramedics. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(22): 12145–12163. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph182212145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Younas A, Quennell S. Usefulness of nursing theory-guided practice: an integrative review. Scand J Caring Sci 2019; 33(3): 540–555. DOI: 10.1111/scs.12670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCay R, Lyles AA, Larkey L. Nurse leadership style, nurse satisfaction, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review. J Nurs Care Qual 2018; 33(4): 361–367. DOI: 10.1097/ncq.0000000000000317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kossman SP, Scheidenhelm SL. Nurses’ perceptions of the impact of electronic health records on work and patient outcomes. CIN Comput Inform Nurs 2008; 26(2): 69–77. DOI: 10.1097/01.ncn.0000304775.40531.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sutton DE, Fogel JR, Giard AS. Defining an essential clinical dataset for admission patient history to reduce nursing documentation burden. Appl Clin Inform 2020; 11(03): 464–473. DOI: 10.1055/s-0040-1713634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson E, Solch AK, Fincke BG, et al. Concerns of primary care clinicians practicing in an integrated health system: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 2020; 35(11): 3218–3226. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-020-06193-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agarwal SD, Pabo E, Rozenblum R, et al. Professional dissonance and burnout in primary care: a qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180(3): 395–401. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beck J, Falco CN, O’Hara KL, et al. The norms and corporatization of medicine influence physician moral distress in the United States. Teach Learn Med 2022; 1–11. DOI: 10.1080/10401334.2022.2056740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson KE, Hanson GC, Boyce D, et al. Organizational impact on healthcare workers’ moral injury during COVID-19: a mixed-methods analysis. JONA J Nurs Adm 2022; 52(1): 57–66. DOI: 10.1097/nna.0000000000001103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gallup Inc . Military brass, judges among professions at new image lows. Gallup, https://news.gallup.com/poll/388649/military-brass-judges-among-professions-new-image-lows.aspx (2022, accessed 24 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rainer JB, Schneider JK. Testing a model of speaking up in nursing. JONA J Nurs Adm 2020; 50(6): 349–354. DOI: 10.1097/nna.0000000000000896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brewer KC. Institutional betrayal in nursing: a concept analysis. Nurs Ethics 2021; 28(6): 1081–1089. DOI: 10.1177/0969733021992448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maguire PA, Looi JC. Moral injury and psychiatrists in public community mental health services. Australas Psychiatry 2022; 30: 326–329. DOI: 10.1177/10398562211062464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yalçın B, Baykal Ü, Türkmen E. Why do nurses choose to stay silent?: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Pract 2022; 28(1): e13010-e13017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kreh A, Brancaleoni R, Magalini SC, et al. Ethical and psychosocial considerations for hospital personnel in the COVID-19 crisis: moral injury and resilience. PLos One 2021; 16(4): e0249609. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hines SE, Chin KH, Glick DR, et al. Trends in moral injury, distress, and resilience factors among healthcare workers at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(2): 488–499. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18020488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patterson JE, Edwards TM, Griffith JL, et al. Moral distress of medical family therapists and their physician colleagues during the transition to COVID-19. J Marital Fam Ther 2021; 47(2): 289–303. DOI: 10.1111/jmft.12504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gaitens J, Condon M, Fernandes E, et al. COVID-19 and essential workers: a narrative review of health outcomes and moral injury. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(4): 1446–1464. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18041446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horsch A, Lalor J, Downe S. Moral and mental health challenges faced by maternity staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma 2020; 12(S1): S141–S142. DOI: 10.1037/tra0000629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Henry BJ. Nursing burnout interventions: what is being done? Clin J Oncol Nurs 2014; 18(2): 211–214. DOI: 10.1188/14.cjon.211-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nowrouzi B, Lightfoot N, Larivière M, et al. Occupational stress management and burnout interventions in nursing and their implications for healthy work environments: a literature review. Workplace Health Saf 2015; 63(7): 308–315. DOI: 10.1177/2165079915576931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Komanduri P. Practitioner application: value-based healthcare initiatives in practice: a systematic review. J Healthc Manag 2021; 66(5): 365–366. DOI: 10.1097/jhm-d-21-00175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.American Association of Critical Care Nurses . AACN standards for establishing and sustaining healthy work environments. 2nd ed.2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lucas G, Colson S, Boyer L, et al. Work environment and mental health in nurse assistants, nurses and health executives: Results from the AMADEUS study. J Nurs Manag 2022; 30(7): 2268–2277. DOI: 10.1111/jonm.13599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Erickson SM, Rockwern B, Koltov M, et al. Putting patients first by reducing administrative tasks in health care: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166(9): 659–661. DOI: 10.7326/m16-2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abraham CM, Zheng K, Norful AA, et al. Primary care practice environment and burnout among nurse practitioners. J Nurse Pract 2021; 17(2): 157–162. DOI: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]