Abstract

The purpose of this study was to define mechanisms by which dopamine (DA) regulates the Na,K-ATPase in alveolar epithelial type 2 (AT2) cells. The Na,K-ATPase activity increased by twofold in cells incubated with either 1 μM DA or a dopaminergic D1 agonist, fenoldopam, but not with the dopaminergic D2 agonist quinpirole. The increase in activity paralleled an increase in Na,K-ATPase α1 and β1 protein abundance in the basolateral membrane (BLM) of AT2 cells. This increase in protein abundance was mediated by the exocytosis of Na,K-pumps from late endosomal compartments into the BLM. Down-regulation of diacylglycerol-sensitive types of protein kinase C (PKC) by pretreatment with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate or inhibition with bisindolylmaleimide prevented the DA-mediated increase in Na,K-ATPase activity and exocytosis of Na,K-pumps to the BLM. Preincubation of AT2 cells with either 2-[1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-5-methoxyindol-3-yl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)maleimide (Gö6983), a selective inhibitor of PKC-δ, or isozyme-specific inhibitor peptides for PKC-δ or PKC-ε inhibited the DA-mediated increase in Na,K-ATPase. PKC-δ and PKC-ε, but not PKC-α or -β, translocated from the cytosol to the membrane fraction after exposure to DA. PKC-δ– and PKC-ε–specific peptide agonists increased Na,K-ATPase protein abundance in the BLM. Accordingly, dopamine increased Na,K-ATPase activity in alveolar epithelial cells through the exocytosis of Na,K-pumps from late endosomes into the basolateral membrane in a mechanism-dependent activation of the novel protein kinase C isozymes PKC-δ and PKC-ε.

INTRODUCTION

Regulation of the Na,K-ATPase by dopamine (DA) activation of G protein-coupled receptors in the renal epithelium is associated with the endocytosis of Na,K-ATPase from the basolateral membrane (BLM) and transport into early and late endosomes (Chibalin et al., 1997). In contrast, activation of G protein-coupled receptors by isoproterenol in the alveolar epithelium resulted in the exocytosis of Na,K-ATPase molecules from the late endosomes into the BLM. This translocation was associated with an increase in the Na,K-ATPase activity in alveolar epithelial cells (Bertorello et al., 1999). We have previously reported that DA increased active Na+ transport and alveolar fluid reabsorption in normal lungs (Barnard et al., 1997) and in a rodent model of acute lung injury, presumably by up-regulating the Na,K-ATPase (Saldias et al., 1999). However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of Na,K-ATPase are not fully understood.

Dopamine is known to activate calcium- and phospholipid-dependent protein kinase C (PKC) in a number of different cell types (Vaughan et al., 1997; Vieira-Coelho et al., 1998; Chibalin et al., 1999; Nishi et al., 1999). At least eight PKC isozymes have been identified in lung epithelial cells, where PKC regulates a number of functions such as surfactant secretion (Gobran et al., 1998), ciliary beat function (Wong et al., 1998), and arachidonic acid metabolism (Peters-Golden et al., 1992). In other cell types, individual PKC isozymes have been shown to translocate to characteristic intracellular sites after activation (Disatnik et al., 1995; Henry et al., 1996), with each isozyme involved in a specific function (Gray et al., 1997; Song et al., 1999). However, a precise role for the different PKC isozymes in alveolar epithelial cells has not been elucidated.

In this study we demonstrated that dopamine via its D1 receptor promotes the exocytosis of Na,K-ATPase molecules from the late endosomes into the BLM via a selective activation of PKC isozymes. We used novel peptide antagonists and agonists of PKC-ε and PKC-δ to identify their role in the exocytosis of Na,K-ATPase molecules, and showed that PKC-ε and PKC-δ isozymes are required for the exocytosis and increase in Na,K-ATPase protein and activity in the basolateral membrane of alveolar epithelial cells. The data suggest a regulatory role for the PKC-ε and PKC-δ in the dopaminergic stimulation of Na,K-ATPase in the lung.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials and Methods

Dopamine, ouabain, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), Tris-ATP, and phorbol 12,13 dibutyrate were obtained from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). GF109203x (BIS, bisindolylmaleimide), 12-(2-cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo-(2,3-a)pyrrolo(3,4-c)-carbazole (Gö6976), and Gö6983 were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). [γ-32P]ATP and 86Rb were from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). Elastase was from Worthington Biochemical (Freehold, NJ). The Na,K-ATPase anti-β1 polyclonal antibody or anti-α1 monoclonal antibody were generously provided by Dr. Martin-Vasallo (University of La Laguna, La Laguna, Spain) and Dr. M. Caplan (Yale University, New Haven, CT), respectively. The mannose 6-phosphate receptor antibody was kindly provided by Dr. B. Hoflack (EMBO, Heidelberg, Germany). The rab 5 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). PKC antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). All other reagents were commercial products of the highest grade available.

Isolation and Culture of Alveolar Epithelial Cells

Alveolar epithelial type 2 (AT2) cells were isolated from pathogen-free male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–225 g), as previously described (Ridge et al., 1997). Briefly, the lungs were perfused via the pulmonary artery, lavaged, and digested with elastase (30 U/ml). AT2 cells were purified by differential adherence to IgG-pretreated dishes, and cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion (>95%). Cells were suspended in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum with 2 mM l-glutamine, 40 μg/ml gentamicin, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and placed in culture for 2 d before the start of all experiments. For studies of [γ-32P]ATP hydrolysis in intact alveolar epithelial cells and preparation of membranes for Western blot analysis, 10 ml of cell suspension (106 cells/ml) was added to 100-mm dishes. For studies evaluating the 86Rb uptake in AT2 cells we used 5 × 106 cells/60-mm dishes. Cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, 95% air at 37°C. Identification of AT2 cells was based on the presence of lamellar inclusions. Lamellar bodies were stained with Papanicolaou stain (Ridge et al., 1997).

Intracellular Peptide Delivery by Transient Permeabilization of AT2 Cells

Peptides εV1–2 (εPKC14–21), psuedo-εRACK (ψεRACK; εPKC85–92), δV1–1 (δPKC), and psuedo-δRACK (ψδRACK) were synthesized and purified (>95%) at the Stanford Protein and Nucleic Acid Facility (Johnson et al., 1996). The peptides were either unmodified or cross-linked via an N-terminal Cys-Cys bond to the Drospholia Antennapedia homeodomain-derived carrier peptide (C-RQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK). Peptides were introduced into cells by either transient permeabilization by using saponin as described by Johnson et al. (1996) with sham permeabilization as control, or as carrier-peptide conjugates with a carrier-carrier dimer as control (control peptide). Permeabilization carried out according to these protocols did not alter alveolar epithelial cell viability.

Na,K-ATPase Activity

Ouabain-sensitive 86Rb+ uptake was used to estimate the rate of K+ transport by Na,K-ATPase in alveolar epithelial cells. Briefly, cells were preincubated for 5 min at 37°C in a gyratory bath at 100 rpm in HEPES-buffered DMEM in the presence or absence of 5 mM ouabain and/or agonists/antagonists. This medium was then removed, and otherwise identical fresh medium containing 1 μCi/ml 86Rb+ was added. After a 5-min incubation (37°C, 100 rpm), uptake was terminated by aspirating the assay medium and washing the plates in ice-cold MgCl2. Plates were allowed to dry and cells were solubilized in 0.2% SDS. 86Rb+ influx was quantified in aliquots of the SDS extract by liquid scintillation counting. Protein was quantified in aliquots by the Bradford method (Ridge et al., 1997).

Na,K-ATPase activity was also determined by [32P]ATP hydrolysis as described previously (Ridge et al., 1997; Bertorello et al., 1999). Briefly, after preincubation with the desired agonists at room temperature, the samples were placed on ice and aliquots (∼10 μg of protein) were transferred to the Na,K-ATPase assay medium (final volume 100 μl) containing in 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 7 mM Na2ATP, and [γ-32P]ATP (specific activity 3000 Ci/mmol) in tracer amounts (3.3 nCi/μl). Cells were transiently exposed to a thermic shock (10 min at −20°C) to render membranes permeable to ATP. The samples were then incubated at 37°C for 15 min, and the reaction was terminated by addition of 700 μl of trichloroacetic acid/charcoal (5/10%, wt/vol) suspension and rapid cooling to 4°C. After separating the charcoal phase (12,000 × g for 5 min) containing the unhydrolyzed nucleotide, the liberated 32P was counted in a 200-μl aliquot from the supernatant. Na,K-ATPase activity was calculated as the difference between test samples (total ATPase activity) and samples assayed in the same medium, but devoid of Na+ and K+ and in the presence of 4 mM ouabain (ouabain-insensitive ATPase activity).

Preparation of Endosomes

AT2 cells in suspension (1.5 mg of protein/ml in phosphate-buffered saline) were incubated with 1 μM DA or vehicle at room temperature for 15 min. Incubation was terminated by transferring the samples to ice and adding cold homogenization buffer containing 250 mM sucrose and 3 mM imidazole, 2 mM EGTA, 10 mM NaF, 30 mM Na4O7P2, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 4 μg/ml aprotinin, pH 7.4. Cells were gently homogenized (15–20 strokes) to minimize damage of the endosomes, by using a Dounce homogenizer, and the samples were subjected to a brief (5 min) centrifugation (4°C, 3000 × g). Endosomes were fractionated on a flotation gradient as described (Bertorello et al., 1999) by using essentially the technique of Gorvel et al. (1991). These fractions were not cross-contaminated, i.e., Rab5 was located exclusively in early endosomes, whereas mannose 6-phosphate receptor immunoreactivity was located in late endosomes (Bertorello et al., 1999).

Preparation of Basolateral Plasma Membranes

After separation of early and late endosomes, another fraction (500 μl) was collected at the 16 and 42% sucrose interface corresponding to cell ghosts, mitochondria, and plasma membranes. BLMs were further purified according to Hammond and Verroust (1994), by using a Percoll gradient. Briefly, the collected material was diluted by adding 500 μl of imidazole (3 mM, pH 7.4) buffer containing protease inhibitors (final sucrose concentration 25/26%, wt/wt), and spun at 20,000 × g for 20 min. The yellow layer was resuspended again in the supernatant (carefully removed from the brown pellet containing mitochondria and cell ghosts) and centrifuged at 48,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of buffer (300 mM mannitol and 12 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, adjusted with Tris) by gentle pipetting. To form a Percoll gradient, 0.19 g of undiluted Percoll (Amersham Biosciences) was added to a 1-ml suspension (0.2–1 mg of protein). The suspension was gently mixed and centrifuged at 48,000 × g for 30 min, and the ring of BLMs was collected.

Western Blot Analysis

Equal amounts of protein from BLMs, isolated as described above, previously (Bertorello et al., 1999), were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with specific Na,K-ATPase anti-β1 polyclonal antibody or anti-α1 monoclonal antibody. For the detection of PKC isozymes, equal amounts of protein were resolved by 10% PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with isozyme-specific antibodies.

PKC Translocation Assay

After incubation of AT2 cells with DA, cells were scraped into a lysis buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 μg/ml trypsin inhibitor, 20 μM leupeptin, 100 nM microcystin, and homogenized for 2 min. Lysates were then centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min to obtain P1 (nuclear and supernatant) fractions. The supernatant fraction was further centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min to obtain P2 (membrane) and S (cytosol) fractions. The P1 and P2 fractions were suspended in lysis buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min and centrifuged (16,000 × g, 20 min, 4°C) to separate the detergent-insoluble and -soluble material. Cytosolic and membrane fractions (20–50 μg) were then subjected to immunoblotting by using isozyme-specific anti-PKC antibodies. Specificity of membrane fractionation was determined by histone H1, a nuclear protein that mainly localizes in the P1 and MEK-1, a marker of cytosol protein, present in the S fraction, but not in the P1 or P2 fraction (our unpublished data).

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons were performed using the unpaired Student's t test. One-way analysis of variance with Tukey's test was used to analyze the data. p < 0.05 values were considered significant.

RESULTS

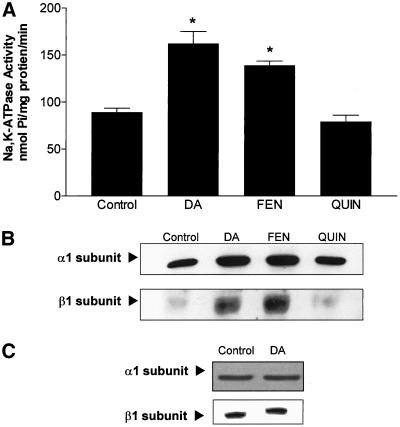

Dopamine Increases Na,K-ATPase Activity via Dopaminergic D1 Receptor

AT2 cells were incubated at room temperature with 1 μM DA for 15 min. As shown in Figure 1A, Na,K-ATPase activity (nmol of Pi/mg protein/min) in nonstimulated AT2 cells was 96 ± 3 (n = 4). DA-stimulated Na,K-ATPase activity in AT2 cells was 185 ± 11 (n = 5). When the AT2 cells were incubated with the specific dopaminergic D1 agonist fenoldopam (FEN, 10−6 M) there was an increase in Na,K-ATPase activity comparable to that seen with DA. In contrast, the dopaminergic D2 agonist quinpirole (QP, 10−6 M) did not increase in Na+ pump activity (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Na,K-ATPase activity, as measured by [γ-32P]ATP hydrolysis, in AT2 cells incubated for 15 min at room temperature with 1 μM DA, FEN, or quinpirole (QP). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of four determinations performed independently (separate cell isolations) and in triplicate. ∗p < 0.05. (B) Na,K-ATPase α and β subunit distribution in AT2 cells incubated for 15 min with 1 μM DA, FEN, or QP. A representative Western blot analysis of the α and β subunit abundance (n = 3). Equal amounts of protein (5 μg) were loaded in each lane. ∗p < 0.05. (C) Na,K-ATPase protein abundance was evaluated by Western blot in whole cells lysates prepared from alveolar epithelial cells treated with 1 μM DA for 15 min and compared with untreated control cells. Top, an immunoreactive band corresponding to the α1 Na,K-ATPase (molecular weight ∼112 kDa) was detected in control and DA-treated whole cells lysates. Bottom, β1 Na,K-ATPase (molecular weight ∼49 kDa) was detected cell lysates prepared from alveolar epithelial cells.

Dopamine Increases Na,K-ATPase Molecules in Basolateral Membrane

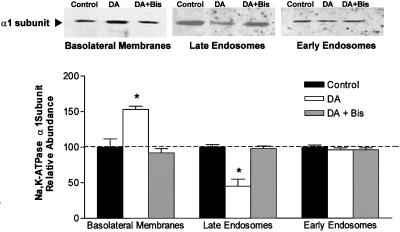

The Na,K-ATPase activity in Figure 1A was measured under Vmax conditions, indicating that the increase in activity was not due to an increase in the turnover rate of the Na,K-pump. Thus, we reasoned that the increase in activity was due to an increase in Na,K-pump molecules in the BLM. BLMs were prepared from cells incubated with DA, FEN, or QP for 15 min at room temperature. As shown in Figure 1B, DA and FEN increased the α1 and β1 subunit abundance compared with nonstimulated control AT2 cells. QP had no effect on the protein abundance of the Na,K-pump. The increased α1 and β1 subunit abundance is not likely to represent increased de novo synthesis of Na,K-ATPase molecules because there was no change in Na,K-ATPase protein abundance in whole cell lysates (Figure 1C), which agrees with a previous report (Lecuona et al., 2000). Thus, we hypothesized that the increased number of Na,K-ATPase molecules within the BLM may be due to recruitment of existing Na,K-pumps from intracellular compartments, possibly early or late endosomes. To examine this possibility, early and late endosomes were prepared from AT2 cells. Their purity and identity were confirmed by enrichment in rab5 and mannose-6 receptor immunoreactivity, respectively (Chibalin et al., 1997; Bertorello et al., 1999). As shown in Figure 2, both populations of endosomes contained Na,K-ATPase α1 subunit. In late, but not early endosomes, prepared from DA-treated AT2 cells, there was a significant decrease in α1 subunit abundance, with a concomitant increase in α1 subunit protein abundance in the BLM from the same cell population. Pretreatment of AT2 cells with 1 μM bisindolylmaleimide (inhibiting only classical and novel PKCs) for 15 min prevented the DA-mediated exocytosis of Na,K-ATPase molecules (Figure 2) and Na,K-pump activity, measured as ouabain-sensitive 86Rb+ uptake (control [CT], 20.8 ± 0.6; DA, 47.8 ± 0.8; BIS, 18.7 ± 2.7; BIS + DA, 18.3 ± 1.4 μmol of K+/mg protein/min; mean ± SEM).

Figure 2.

Na,K-ATPase α1 subunit abundance in basolateral, early, and late endosomes prepared from DA-treated AT2 cells. Cells were incubated with 1 μM DA for 15 min at room temperature in the presence or absence of 1 μM bisindolylmaleimide (I). Equal amounts of protein (5 μg) were loaded in each lane. Top, representative Western blot of the α subunit abundance; bottom, quantitative densitometric scan of three experiments (mean ± SEM), ∗p < 0.05.

Role of Protein Kinase C on DA-mediated Na,K-ATPase Stimulation

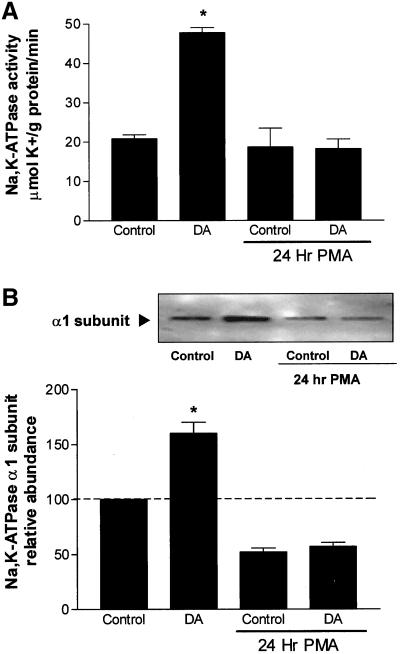

Rat AT2 cells express PKC-α, -βI, -βII, -δ, -ε, and -θ, but not PKC-γ of classical and novel PKC isozymes (Gobran et al., 1998). Overnight treatment with the phorbol ester PMA (1 μM) down-regulated PKC-α, -βI, -βII, -δ, and -θ, and partially down-regulated PKC-ε (our unpublished data). Down-regulation of the classical PKC and novel PKC by PMA prevented the DA-mediated increase in Na,K-ATPase activity (Figure 3A) and increase in the Na,K-ATPase α1 protein abundance in the BLM (Figure 3B). These results suggest that phorbol ester-sensitive PKC isozymes are involved in mediating the DA effects on the Na,K-pump.

Figure 3.

(A) Effect of PKC down-regulation on DA-mediated stimulation of Na,K-ATPase activity, as measured by ouabain-sensitive 86Rb uptake, in AT2 cells. Cells were treated with 1 μM PMA for 18–24 h and then treated with 1 μM DA for 15 min. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of three independent cell isolations. Determinations were performed in quadruplicate. ∗p < 0.01. (B) Effect of PKC down-regulation on DA-mediated recruitment/translocation of Na,K-ATPase α subunit in AT2 cells. Cells were treated with 1 μM PMA for 18–24 h and then treated with 1 μM DA for 15 min. Top, representative Western blot of the α subunit abundance; bottom, quantitative densitometric scan of three experiments (mean ± SEM), ∗p < 0.05.

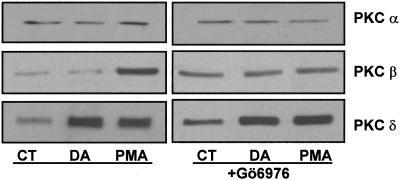

Protein Kinase C α and β

To determine whether PKC-α and PKC-β were involved in the DA-mediated increase in Na,K-ATPase we used Gö6976, a selective inhibitor of PKC-α and PKC-β. To verify the specificity this inhibitor, AT2 cells were pretreated with Gö6976 and then with 1 μM PMA or DA. Gö6976 prevented the phorbol ester-mediated activation of PKC-α and PKC-β, but not PKC-δ, demonstrating the specificity of this antagonist (Figure 4). DA-stimulated Na,K-ATPase activity, as measured by [γ-32P]ATP hydrolysis, was unaffected by the pretreatment with Gö6976 (Figure 5). Furthermore, Gö6976 did not prevent the DA-mediated exocytosis of Na,K-ATPase molecules to the BLM (Figure 6). Finally, treatment with DA did not cause translocation of cytosolic PKC-α or PKC-β to the membrane (Figure 7).

Figure 4.

AT2 cells were pretreated with 1 μM Gö6976 for 15 min and stimulated with either 1 μM DA or 1 μM PMA and compared with untreated control cells. Subcellular fractionation was performed on the cells to obtain membrane and cytosol fractions. Equal amounts of protein (15 μg) were loaded in each lane. Western blot analysis of PKC isozymes with isozyme-specific antibodies was performed. Shown is a representative autoradiogram of the membrane fraction.

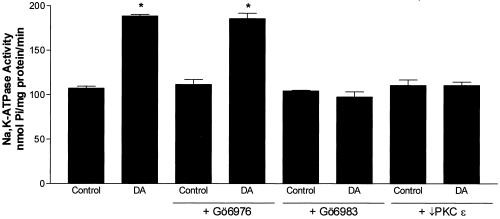

Figure 5.

Effect of isozyme-specific PKC inhibitors on DA-mediated increase in Na,K-ATPase activity, as measured by ouabain-sensitive [32P]ATP hydrolysis. Cells were incubated for 15 min in the presence or absence of 1 μM Gö6976, a selective inhibitor of PKC-α and PKC-β; 100 nM Gö6983, a selective inhibitor of PKC-α, -β, and -δ; or PKC-ε translocation peptide inhibitor εV1-2 (5 μM), followed by a 15-min incubation in the presence or absence of 1 μM DA. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of four independent cell isolations. Determinations were performed in triplicate. ∗p < 0.001.

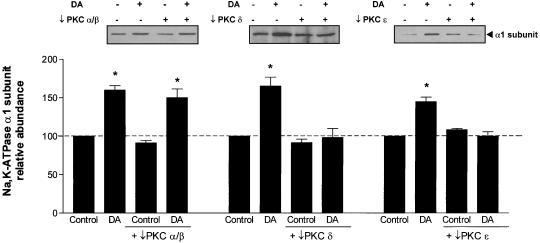

Figure 6.

Effect of isozyme-specific PKC inhibitors on DA-mediated exocytosis of Na,K-ATPase α subunit in AT2 cells. Cells were incubated for 15 min in the presence or absence of 1 μM Gö6976, PKC-δ peptide antagonist δ V1-1 (100 nM), or PKC-ε peptide antagonist εV1-2 (5 μM), followed by a 15-min incubation in the presence or absence of 1 μM DA. Representative Western blot of the α subunit abundance (n = 3) is shown. ↓, PKC antagonist.

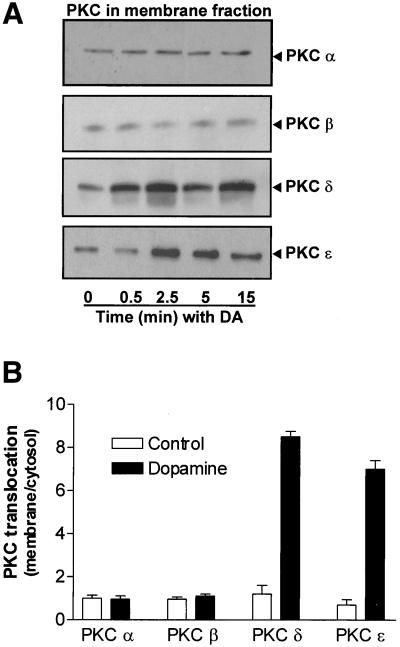

Figure 7.

DA-mediated translocation of PKC isozymes within subcellar compartments. AT2 cells were exposed to DA for 0 s, 30 s, 2.5 min, 5 min, and 15 min. Subcellular fractionation was performed to obtain the membrane and cytosol fractions. (A) Representative Western blot of the membrane fraction for PKC-α, -β, -δ, and -ε is shown. Equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane. (B) Densitometric analysis of the immunoreactivity of PKC-α, -β, -δ, and -ε expressed as the ratio for membrane-bound to cytosol fraction for control and DA-treated cells at 15 min (n = 4).

Role of Protein Kinase C-δ and -ε

DA-stimulated Na,K-ATPase activity was inhibited in AT2 cells pretreated with either Gö6983, an inhibitor of PKC-δ, or PKC-ε translocation inhibitor peptide εV1-2, before DA stimulation (Figure 5). Cells treated with the PKC-ε translocation inhibitor peptide were compared with vehicle-treated (saponin) control cells, which were not different from nonvehicle-treated control cells (our unpublished data). Additionally, cells pretreated with either an isozyme specific PKC-δ peptide antagonist (δ V1-1, 100 nM) or PKC-ε translocation inhibitor peptide (εV1-2, 5 μM) before DA stimulation prevented the increase in the Na,K-ATPase α subunit protein abundance in the BLM, as measured by Western blot (Figure 6). In untreated AT2 cells, PKC-δ and PKC-ε were mostly localized in the cytosolic and nuclear pellet fractions (our unpublished data). Treatment with DA caused an activation and translocation of PKC-δ and PKC-ε into the membrane fraction (Figure 7). The DA-mediated activation of PKC isozymes was time dependent, with PKC-δ being activated within 30 s and PKC-ε being activated within 2.5 min of DA exposure (Figure 7).

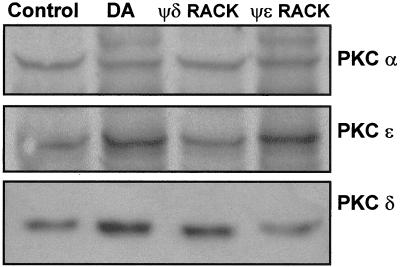

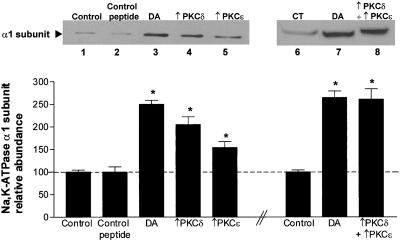

To determine whether PKC-δ and PKC-ε were responsible for DA-stimulated Na,K-ATPase activity AT2 cells were preincubated with PKC-ε agonist (ψεRACK) and/or PKC-δ agonist (ψδRACK). The specificity of these peptide agonists was established as shown in Figure 8. The PKC-δ peptide agonist ψδRACK activated PKC δ only, and that PKC-ε peptide agonist ψεRACK activated PKC-ε only. These experiments demonstrate that there is no cross-specificity between the PKC isoform-specific reagents. AT2 cells were incubated with 100 nM PKC-ε agonist (ψεRACK) and/or PKC-δ agonist (ψδRACK), conjugated to cell-permeable carrier peptide, for 15 min at room temperature. As shown in Figure 9, top, treatment of AT2 cells with either the PKC-δ peptide agonist (lane 4) or PKC-ε peptide agonist (lane 5) increased the Na,K-ATPase α1 protein abundance in the BLM, but to a lesser extent than as with DA (lane 3). When AT2 cells were treated with both PKC-δ and PKC-ε peptide agonists (lane 8), the Na,K-ATPase α subunit abundance in the BLM was similar to that observed with DA alone (lane 7).

Figure 8.

Specificity of PKC peptide agonists. The specificity of PKC peptide agonists was determined in AT2 cells that were incubated for 15 min with 1 μM DA, 100 nM PKC-δ peptide agonist ψδRACK, or 100 nM PKC-ε peptide agonist ψεRACK and compared with untreated control cells. Subcellular fractionation was performed on the treated cells to obtain membrane and cytosol fractions. Equal amounts of protein (15 μg) were loaded in each lane. Western blot analysis of PKC isozymes with isozyme-specific antibodies was performed. Shown is a representative autoradiogram of the membrane fraction showing activation of PKC isozymes corresponding to treatment with PKC isozyme-specific peptide agonists or DA.

Figure 9.

Effect of PKC-δ and PKC-ε peptide agonists on the exocytosis of Na,K-ATPase α subunit in AT2 cells. Cells were treated with 100 nM PKC-δ and/or PKC-ε agonists ψδRACK and ψεRACK, respectively, for 15 min. Top, representative Western blot of the α subunit abundance; bottom, quantitative densitometric scan of three experiments (mean ± SEM), ∗p < 0.05. CTP, scrambled control peptide; (+)dPKC, PKC-δ peptide agonist; (+)ePKC, PKC-ε peptide agonist.

DISCUSSION

Fluid reabsorption in the lung is dependent upon active Na+ transport regulated, in part, by the Na,K-ATPase located in the basolateral membrane of alveolar epithelial cells. We have reported that DA stimulates active Na+ transport and alveolar fluid reabsorption via activation of the dopaminergic D1 receptor (Barnard et al., 1999). In the present study, we demonstrate that in alveolar epithelial cells DA regulates Na,K-ATPase activity by activating D1 receptors, and translocating Na,K-ATPase molecules from the late endosomal compartment to the basolateral membrane of AT2 cells via PKC-δ– and PKC-ε–dependent mechanisms.

Dopamine-dependent Stimulation of Na,K-ATPase Activity

We report herein that DA stimulates Na,K-ATPase in alveolar epithelial cells via D1 receptor (D1R) activation. As shown in Figure 1, fenoldopam, a D1R agonist, increased the Na,K-ATPase activity in AT2 cells, whereas AT2 cells incubated with the D2R agonist quinpirole showed no change in Na,K-pump function. Stimulation of Na,K-ATPase activity was not mediated by changes in its turnover rate (i.e., the number of ions transported per pump molecule per unit time), nor by changes in the affinity for substrates, because the experiments were performed under Vmax conditions. Rather, DA-stimulated Na,K-ATPase activity by increasing the number of functioning Na,K-ATPase molecules in the basolateral membrane (Figures 1A, 2, and 3B). There are several mechanisms by which DA may increase the number of Na,K-ATPase molecules in the BLM, including changes in the rate of Na,K-ATPase protein synthesis. In fact, we have previously demonstrated that activation of the D2 receptor resulted in the increase in Na,K-ATPase abundance and enzymatic activity (Guerrero et al., 2001). However, this process occurred over a period of 18–24 h, much longer than the 15-min time course of our experimental conditions. Therefore, we reasoned that Na,K-pumps were stored in intracellular compartments and could then be recruited for insertion in the basolateral membrane. As shown in Figure 2, DA-treated AT2 cells had increased incorporation of Na,K-ATPase α1 subunit in the BLM, associated with a decrease in α1 protein abundance in the late endosomal compartment. Bisindolylmaleimide, a conventional and novel PKC inhibitor, prevented both the DA-mediated exocytosis of Na,K-ATPase molecules to the BLM and the increase in the Na,K-ATPase activity (Figure 2). These results suggest that DA mediates the exocytosis of the Na,K-ATPase via protein kinase C.

Na,K-ATPase and Protein Kinase C

Movement of the Na,K-ATPase between the plasma membrane and intracellular compartments have either required kinase activation (Chibalin et al., 1998, 1999) or not (Beron et al., 1997; Feraille et al., 2000). In renal epithelia, stimulation of Na,K-ATPase activity due to an increase in the amount of molecules present at the plasma membrane has been reported to be the consequence of activating PKC-β, whereas DA inhibited Na,K-ATPase activity by activating PKC-ζ (Efendiev et al., 1999, 2000) or PKA (Carranza et al., 1996). Stimulation by PMA in a renal proximal tubule cell line is mediated by PKC-β isoform and this effect requires phosphorylation of both Ser11 and Ser18 residues in the rat Na,K-ATPase α subunit. In NRK-52E and L6 cells, PKC-α mediated the phosphorylation of Ser 18 residue in the Na,K-ATPase α1 subunit; this phosphorylation was reduced by prior activation of cAMP-dependent signaling pathway (Feschenko et al., 2000). The Na,K-ATPase was not phosphorylated in alveolar epithelial cells treated with isoproterenol (Bertorello et al., 1999), nor was the Na,K-ATPase phosphorylated in dopamine-treated LLCPK-1 cells in which PKC-α and PKC-ε were activated (Nowicki et al., 2000).

Defining a specific function to a specific PKC isozyme presents technical limitations such as the inability of most commercially available agonists and antagonists to discriminate among the different PKCs. More recently, several PKC isozyme-selective inhibitor peptides have been developed based on their ability to inhibit translocation and interaction of individual activated PKC isozymes (Souroujon and Mochly-Rosen, 1998). For example, a translocation inhibitor peptide selective for PKC-ε (εPKC14–21) prevented ischemic preconditioning in cultured cardiac myocytes (Gray et al., 1997), whereas a selective PKC-ε selective peptide agonist (εPKC85–92) promoted cardioprotection from ischemia in cardiomyocytes (Dorn et al., 1999). Recently, PKC-δ–selective antagonist and agonist peptides have also been identified and characterized (Chen and Mochly-Rosen, 2001).

We used specific inhibitors to determine which PKC isozymes regulate the Na,K-ATPase activity. As shown in Figure 5, AT2 cells pretreated with Gö6976 did not prevent the DA-stimulated increase in Na,K-ATPase activity. In contrast, pretreatment of AT2 cell with Gö6983 prevented the DA-stimulated increase in Na,K-ATPase activity. Gö6983 inhibits PKC-α and PKC-β, as well as PKC-δ (Gschwendt et al., 1996); therefore, we used the PKC-δ peptide antagonist δV1-1 as well as a PKC-ε translocation inhibitor peptide (εV1–2). Both PKC-δ and PKC-ε peptide antagonists prevented the DA-mediated exocytosis of Na,K-ATPase molecules to the BLM (Figure 6).

Activation and Role of Specific PKC Isozymes

Stimulation of cells with phorbol esters or hormones results in the translocation of PKC to new subcellular sites, including the plasma membrane (Shoji et al., 1986), cytoskeletal elements (Prekeris et al., 1998), and nuclei (Soh et al., 1999). Additionally, within the same cell, PKC isozymes are localized to different subcellular sites after cell stimulation. For example, in primary cardiac myocytes, stimulation of the α1-adrenergic receptor results in translocation of the PKC-βII from fibrillar structures outside the nucleus to the perinuclear and membrane structures, PKC-βI from the cytosol into the nucleus, and PKC-ε from inside the cytosol to contractile elements within these cells (Mochly-Rosen, 1995). In LLCPK-1 cells DA, via the D1R, induced the translocation from cytosol to plasma membrane of PKC-α and -ε, but not -δ, -γ, and -ζ (Nowicki et al., 2000). In the present work subcellular fractionation of DA-stimulated AT2 cells showed that PKC-δ and PKC-ε, but not PKC-α or PKC-β translocate from the cytosol to the membrane fraction and that the activation of PKC-δ occurs before that of PKC-ε (Figure 6). Together, these results indicate that PKC isozymes are differentially compartmentalized, suggesting that they mediate distinct cellular functions.

PKC-ε has been shown regulate diverse functions in cells of various origins, including the modulation of gene expression (Soh et al., 1999), cell adhesion (Chun et al., 1996), and secretory vesicle trafficking (Prekeris et al., 1996). It has also been demonstrated that filamentous actin recognizes and binds directly to a hexapeptide motif that is unique to the regulatory C1 domain of PKC-ε (Prekeris et al., 1996, 1998). In intestinal epithelial cells, PKC-ε stimulated basolateral endocytosis by a mechanism that involved reorganization of the F-actin. We observed that AT2 cells pretreated with PKC-ε translocation inhibitor peptide εV1-2 prevented the DA-mediated exocytosis of Na,K-ATPase molecules (Figure 6). Additionally, stabilization of the actin cytoskeleton with phallacidin also prevented DA-mediated increase in Na,K-pump activity (our unpublished data). Thus, we reason that PKC-ε may have a role in the actin-mediated Na,K-ATPase trafficking within the AT2 cells.

In this report, we provide direct evidence that dopamine selectively activates PKC-δ and PKC-ε in alveolar epithelial cells (Figure 7). Treatment of AT2 cells with specific peptide agonists for either PKC-δ, ψδRACK, or PKC-ε, ψεRACK (Figure 8), increased Na,K-ATPase molecules in the BLM compared with cells treated with a scrambled control peptide. However, only when AT2 cells were treated with both peptide agonists (PKC-δ, ψδRACK, and PKC-ε, ψεRACK) the response was similar to that observed upon treatment with DA, suggesting that both PKC-ε and PKC-δ participate in the regulation of Na,K-ATPase by DA in AT2 cells (Figure 9). These data advance our understanding of specific PKC isozymes involved in the regulation of the Na,K-ATPase, although it is still unresolved whether PKC phosphorylates an intermediate protein (i.e., cytoskeleton, adapter proteins, exocytotic proteins) that regulates the Na,K-ATPase function in the lung.

In conclusion, vectorial transport of sodium in the alveolar epithelium is critical for the regulation of alveolar fluid clearance (Saldías et al., 1998; Ware and Matthay, 2000). DA has been shown to increase active sodium transport and lung edema clearance (Barnard et al., 1997, 1999). This study demonstrates that DA regulates Na,K-ATPase activity in alveolar type 2 cells via the D1 receptor, by increasing the number of Na,K-pumps in the plasma membrane. This regulation is rapid (within 15 min) and probably does not involve synthesis of new molecules. Rather, the new Na,K-pumps incorporated in the plasma membrane are recruited from defined intracellular compartments, e.g., the late endosomes. Once in the plasma membrane, these newly inserted proteins contribute to the increase in cellular Na,K-ATPase activity and consequently to vectorial Na+ flux across the alveolar epithelium. The DA-mediated exocytosis of Na,K-ATPase molecules is mediated by novel PKCs (specifically PKC-δ and PKC-ε), and not by conventional PKCs. This report suggests a novel role for PKC-δ and PKC-ε in regulating the exocytosis of Na,K-ATPase molecules to the basolateral membrane, which results in increased Na,K-ATPase activity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by grants HL-65161 and National Research Science Award (to K.M.R) from the National Institutes of Health and Northwestern University. K.M.R. is a Parker B. Francis Fellow.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.01–07–0323. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.01–07–0323.

REFERENCES

- Barnard ML, Olivera WG, Rutschman DM, Bertorello AM, Katz AI, Sznajder JI. Dopamine stimulates sodium transport and liquid clearance in rat lung epithelium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:709–714. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.3.9610013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard ML, Ridge KM, Saldias F, Friedman E, Gare M, Guerrero C, Lecuona E, Bertorello AM, Katz AI, Sznajder JI. Stimulation of the dopamine 1 receptor increases lung edema clearance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:982–986. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.3.9812003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beron J, Forster I, Beguin P, Geering K, Verrey F. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate down-regulates Na,K-ATPase independent of its protein kinase C site: decrease in basolateral cell surface area. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:387–398. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.3.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertorello AM, Ridge KM, Chibalin AV, Katz AI, Sznajder JI. Isoproterenol increases Na+-K+-ATPase activity by membrane insertion of alpha-subunits in lung alveolar cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L20–L27. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.1.L20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carranza ML, Feraille E, Favre H. Protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation of Na,K-ATPase α subunit in rat kidney cortical tubules. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C136–C143. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.1.C136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Mochly-Rosen D. Opposing Effects of delta, and xi PKC in ethanol-induced cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:581–585. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibalin AV, Katz AI, Berggren PO, Bertorello AM. Receptor-mediated inhibition of renal Na,K-ATPase is associated with endocytosis of its α and β subunits. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1458–C1465. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.5.C1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibalin AV, Ogimoto G, Pedemonte CH, Pressley TA, Katz AI, Feraille E, Berggren PO, Bertorello AM. Dopamine-induced endocytosis of Na+,K+-ATPase is initiated by phosphorylation of Ser-18 in the rat alpha subunit and is responsible for the decreased activity in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1920–1927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibalin AV, Pedemonte CH, Katz AI, Feraille E, Berggren PO, Bertorello AM. Phosphorylation of the catalytic α subunit constitutes a triggering signal for Na,K-ATPase endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8814–8819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun JS, Ha MJ, Jacobson BS. Differential translocation of protein kinase C epsilon during HeLa cell adhesion to a gelatin substratum. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13008–13012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.13008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disatnik MH, Jones SN, Mochly-Rosen D. Stimulus-dependent subcellular localization of activated protein kinase C; a study with acidic fibroblast growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta 1 in cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:2473–2481. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1995.0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn GWN, Souroujon MC, Liron T, Chen CH, Gray MO, Zhou HZ, Csukai M, Wu G, Lorenz JN, Mochly-Rosen D. Sustained in vivo cardiac protection by a rationally designed peptide that causes epsilon protein kinase C translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12798–12803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efendiev R, Bertorello AM, Pedemonte CH. PKC-beta and PKC-zeta mediate opposing effects on proximal tubule Na+,K+-ATPase activity. FEBS Lett. 1999;456:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00925-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efendiev R, Bertorello AM, Pressley TA, Rousselot M, Feraille E, Pedemonte CH. Simultaneous phosphorylation of Ser11 and Ser18 in the alpha-subunit promotes the recruitment of Na(+),K(+)-ATPase molecules to the plasma membrane. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9884–9892. doi: 10.1021/bi0007831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feraille E, Beguin P, Carranza ML, Gonin S, Rousselot M, Martin PY, Favre H, Geering K. Is phosphorylation of the alpha1 subunit at Ser-16 involved in the control of Na,K-ATPase activity by phorbol ester-activated protein kinase C? Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:39–50. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschenko M, Stevenson E, Sweadner K. Interaction of protein kinase C and cAMP-dependent pathways in the phosphorylation of the Na,K-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34693–34700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005869200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobran LI, Xu ZX, Rooney SA. PKC isoforms and other signaling proteins involved in surfactant secretion in developing rat type II cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L901–L907. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.6.L901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorvel JP, Chavrier P, Zerial M, Gruenberg J. rab5 controls early endosome fusion in vitro. Cell. 1991;64:915–925. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90316-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MO, Karliner JS, Mochly-Rosen D. A selective epsilon-protein kinase C antagonist inhibits protection of cardiac myocytes from hypoxia-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30945–30951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gschwendt M, Dieterich S, Rennecke J, Kittstein W, Mueller HJ, Johannes FJ. Inhibition of protein kinase C mu by various inhibitors. Differentiation from protein kinase c isoenzymes. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:77–80. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00785-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero C, Lecuona E, Pesce L, Ridge KM, Sznajder JI. Dopamine regulates Na-K-ATPase in alveolar epithelial cells via MAPK-ERK-dependent mechanisms Am. J Physiol. 2001;281:L79–L85. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.1.L79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond TG, Verroust PG. Trafficking of apical proteins into clatharin-coated vesicles isolated from rat renal cortex. Am J Physiol, 1994;267:F554–F562. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.266.4.F554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry P, Demolombe S, Puceat M, Escande D. Adenosine A1 stimulation activates delta-protein kinase C in rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1996;78:161–165. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JA, Gray MO, Karliner JS, Chen CH, Mochly-Rosen D. An improved permeabilization protocol for the introduction of peptides into cardiac myocytes. Application to protein kinase C research. Circ Res. 1996;79:1086–1099. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.6.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuona E, Garcia A, Sznajder JI. A novel role for protein phosphatase 2A in the dopaminergic regulation of Na,K-ATPase. FEBS Lett. 2000;481:217–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochly-Rosen D. Localization of protein kinases by anchoring proteins: a theme in signal transduction. Science. 1995;268:247–251. doi: 10.1126/science.7716516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi A, Fisone G, Snyder GL, Dulubova I, Aperia A, Nairn AC, Greengard P. Regulation of Na+,K+-ATPase isoforms in rat neostriatum by dopamine and protein kinase C. J Neurochem. 1999;73:1492–1501. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki S, Kruse MS, Brismar H, Aperia A. Dopamine-induced translocation of protein kinase C isoforms visualized in renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:C1812–C1818. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.6.C1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters-Golden M, Coburn K, Chauncey JB. Protein kinase C activation modulates arachidonic acid metabolism in cultured alveolar epithelial cells. Exp Lung Res. 1992;18:535–551. doi: 10.3109/01902149209064344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prekeris R, Hernandez RM, Mayhew MW, White MK, Terrian DM. Molecular analysis of the interactions between protein kinase C-epsilon and filamentous actin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26790–26798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prekeris R, Mayhew MW, Cooper JB, Terrian DM. Identification and localization of an actin-binding motif that is unique to the epsilon isoform of protein kinase C and participates in the regulation of synaptic function. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:77–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridge K, Rutschman DH, Factor P, Katz AI, Bertorello AM, Sznajder JI. Differential expression of Na,K-ATPase isoforms in rat alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L246–L255. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.1.L246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldías F, Lecuona E, Friedman E, Barnard ML, Ridge KM, Sznajder JI. Modulation of lung liquid clearance by isoproterenol in rat lungs. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L694–L701. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.5.L694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldias FJ, Lecuona E, Comellas AP, Ridge KM, Sznajder JI. Dopamine restores lung ability to clear edema in rats exposed to hyperoxia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:626–633. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.2.9805016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji M, Girard PR, Mazzei GJ, Vogler WR, Kuo JF. Immunocytochemical evidence for phorbol ester-induced protein kinase C translocation in HL60 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;135:1144–1149. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)91047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soh JW, Lee EH, Prywes R, Weinstein IB. Novel roles of specific isoforms of protein kinase C in activation of the c-fos serum response element. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1313–1324. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JC, Hrnjez BJ, Farokhzad OC, Matthews JB. PKC-epsilon regulates basolateral endocytosis in human T84 intestinal epithelia: role of F-actin and MARCKS. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C1239–C1249. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.6.C1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souroujon MC, Mochly-Rosen D. Peptide modulators of protein-protein interactions in intracellular signaling. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:919–924. doi: 10.1038/nbt1098-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan RA, Huff RA, Uhl GR, Kuhar MJ. Protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation and functional regulation of dopamine transporters in striatal synaptosomes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15541–15546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira-Coelho MA, Teixeira VL, Finkel Y, Soares-da-Silva P, Bertorello AM. Dopamine inhibits jejunal Na,K-ATPase activity during high salt diet in young but not in adult rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G1317–G1323. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.6.G1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med, 2000;342:1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong LB, Park CL, Yeates DB. Neuropeptide Y inhibits ciliary beat frequency in human ciliated cells via nPKC, independently of PKA. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C440–C448. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]